CHAPTER 5

A Horrible and Shocking Prophecy

The Appalling Accuracy of “Wilhelm Friess”

With a better understanding of when the L version of “Wilhelm Friess” was printed and how the text took shape, we have come full circle, returning once again to Antwerp and the Low Countries. In Dutch history, 1566 is the wonderjaar, the “year of miracles,” which saw the outbreak of open hostilities and the initial successes of the Dutch Revolt against Habsburg rule.1 The events were so remarkable that Godevaert van Haecht, a Dutch Lutheran observer of events in Antwerp at the time, thought that a prophecy made seven years earlier that had foreseen a miraculous year was then being fulfilled.2 Although the prophecy van Haecht referred to was probably not “Wilhelm Friess,” the context in which the lost Dutch edition of “Wilhelm Friess” was circulating included the sense that long-awaited events were coming to pass.

Like the earliest editions of the N version, the two editions of the L version provide a list of sects that makes clear its Lutheran perspective. The sects—which, in the L version, will be not just converted but destroyed—include “Papists, Calvinists, Jovists, Anabaptists, Sacramentarians, etc.” (38–42). “Sacramentarians” was another name for Calvinists, while “Jovists” (Jovisten) is perhaps a misreading of “Joristen,” followers of the Anabaptist leader David Joris. These are not the religious enemies of German Gnesio-Lutherans in the 1550s found in the N version. They are, instead, the religious opponents faced specifically by Lutherans in the Netherlands during the age of confessionalization, as the mainstream Protestant churches were taking separate paths and drawing harder boundaries between Lutheran and Reformed doctrine and worship, a process that gained particular force in the Netherlands in the decade following the abdication of Charles V.3

The Dutch Revolt began with a wave of vandalism directed at religious images and church altars. The L version updated the prophecy accordingly. Where all other versions of “Wilhelm Friess” predicted only the destruction of cloisters, the L version foresaw the destruction and also the plundering of both cloisters and churches (56). In the wake of the rioting, the Habsburg central government lost the ability to impose its will in much of the Netherlands, and even reputable printers began openly publishing seditious pamphlets and Protestant religious works.4 Just as “Wilhelm Friess” had predicted, the common people had risen up against their rulers.

The rebellion emphasized the contrast between Calvinism and Lutheranism with respect to one of the sorest points of contention between the two strands of Protestantism. Where Calvinist preachers had justified underground worship, Luther had counseled cooperation with the government in religious matters, even if it meant delaying the Reformation in an area until the local sovereign could be converted. Consequently, Calvinists were more likely to approve violent resistance to unrighteous secular rule, while Lutherans were more likely to oppose revolution and to accept the feudal political hierarchy led by the Holy Roman Emperor.5 The emperor from the west who persecutes Christians may be wicked in “Wilhelm Friess,” but the L version adds that he has been sent by God for just that purpose (230). Although Frans Fraet was executed for printing a seditious prophecy, “Wilhelm Friess” had always regarded popular revolt with ambivalence at best. Unlike the sword of popular justice in store for the nobility in the Vademecum, the earliest versions of “Wilhelm Friess” foresaw that the nobility would violently suppress the revolt of the common people. Where other versions of “Wilhelm Friess” foretell the death of those who refuse to repent, the L version adds rebellious people to the list of the doomed (42) and includes a new prediction that no more sects will arise. Opposing views on the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper were another source of contention. When both the sacramental host and wine were offered to Protestants in Antwerp in the fall of 1566, the Calvinists mocked the Lutherans—whose religious views did not contrast as sharply as theirs with Catholicism—as idol worshippers, flesh eaters, and blood drinkers.6

Lutherans who distanced themselves from the revolt saw their loyalist position vindicated in 1567, when the Calvinists of Antwerp experienced a series of traumatic defeats. On 13 March 1567, residents of Antwerp standing on the city walls were spectators to the Battle of Oosterweel, in which Calvinist rebels led by Jan van Marnix, elder brother of Philips van Marnix, faced an army of experienced soldiers led by Filips van Lannoy, captain of the Habsburg governor’s bodyguard. As the Calvinists of Antwerp watched the annihilation and massacre of the rebels, they began arming themselves in order to come to the aid of the defeated soldiers outside the walls. William of Orange, as duly appointed burgraaf of Antwerp, prevented this action by sealing the city gates and told the Calvinists that any attempt to interfere would only lead to their deaths. Within a few months, William would abandon his position and become a leader of the revolt, but in March 1567, he still recognized his obligation to the Habsburg monarch who had appointed him.

Despite William’s orders, the Calvinists of Antwerp did not stand down. They began to assemble and arm themselves with their own weapons and with weapons plundered from city merchants. Calvinist leaders demanded the surrender of city authority, threatened to expel all Catholic clergy and believers from the city, and rejected the accord of religious peace that had been in force in Antwerp since September 1566.7 William of Orange agreed to let Calvinists keep watch jointly with the city guard over Antwerp’s Great Market, the town hall, and the city walls and gates. Despite this concession, a group of Calvinists broke into the Cloister of St. Michael and set about ransacking it.

The next day, William of Orange continued his frantic riding between the city’s civic and religious leaders in order to negotiate a peaceful settlement, but his initial attempts were rejected, and Reformed preachers began to threaten that the Lutherans, derided as “new papists,” would meet the same fate as Catholics if they did not lend their support to the uprising.8 In reaction to this, William signaled that all those who were loyal to the king, the city of Antwerp, and the Lutheran Augsburg Confession should form an army, with arms and artillery provided by the city’s armory. The Lutherans and three companies of the city guard assembled on the Oever, a market near the banks of the river Scheldt. The Calvinists who had held watch at the Great Market and city hall retreated to join the main Calvinist force on the Meir, a market to the southeast, while the vandals who had broken into the Cloister of St. Michael found themselves cut off from the main Calvinist force and agreed to disperse peacefully. William of Orange gathered additional aid in the form of two hundred horse and riders from the German residents of Antwerp and the “Easterlings,” or merchants of the Hanseatic League, who rode in from Antwerp’s new district and, upon finding the Great Market well defended, continued on to the Oever. The Lutherans and city guard were soon joined by many Catholics, who recognized that a Calvinist victory would result in their expulsion or worse. Upon seeing the Lutheran army assembled and recognizing the particular enmity that many of the common people held against them, the Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese merchants assembled a force of a thousand armed men and took up position between St. Jacob’s Church and the Kipdorp Gate, just a few streets from the Calvinists assembled on the Meir. Van Haecht estimated the Calvinist army as ten thousand men at arms, while the army gathered by William of Orange had eight thousand soldiers and so many additional supporters in surrounding streets that their numbers seemed countless to him.9 Observers expected violence between the two immense armies within the city to break out at any moment, with a fearful vengeance to be wrought afterward against the homes and families of the losing side.10

The Calvinist leaders finally recognized that they were surrounded and outnumbered. The Lutherans and their supporters lined the whole length of the Oever and the streets on either side in ranks nine deep almost as far as the town hall and Great Market, which were well defended by cannon and companies of the city guard, cutting off access to the Scheldt. The Spaniards, Portuguese, and Italians blocked movement toward the new city and merchant shops to the north and the closest city gate to the east.

The tactically hopeless situation of Antwerp’s Calvinists made their figurative isolation all too clear. They could see with their own eyes how the Lutherans had made common cause with the Catholics and how representatives from the nations of Europe on all sides had united against them. On 15 March, the Calvinists lay down their arms and dispersed according to the terms of what seemed to them a humiliating defeat, which remained a source of resentment against the Lutherans into the seventeenth century. Some Calvinists accused the Lutherans of having become Catholics, as there were so many Catholics in their army.11 It must have been all the more galling that the Lutheran prophecy of Wilhelm Friess, which foresaw the uprising of the common people ending ignominiously, had been proved correct. Back in Germany, Mathias Flacius defended himself against the accusation that he was to blame for the recent unrest in the Netherlands in similar terms, treating ruthless suppression as the consequence of revolt against legitimate rulers: “And what else did [the Calvinists] accomplish in the end by their rebellion against the civil government except for falling into even greater calamity, burdening the gospel of Christ and all those churches with the foul name of sedition, and finally giving their persecutors a worthier cause for such anger against them?” Following the Battle of Oosterweel and other defeats at the hands of the multinational Habsburg armies, many Dutch Protestants began fleeing in April 1567 to refuges abroad. News of the dramatic events in Antwerp spread quickly. At least one pamphlet about them appeared in Augsburg in 1567, and it is known from other cases that news of Dutch events could appear in German-language pamphlets as little as three weeks after the fact.12

The new editions and revised text of “Wilhelm Friess” in 1566–68 were reactions to recent events in the Netherlands, and they offer an additional example of how the text changed form and took on new meanings in new places and different times. The L version provides the link to and the impetus for yet another text attributed to Wilhelm Friess, which again claimed to have been found with him after his recent death in Maastricht and which became a new best-selling prophetic pamphlet beginning in 1577, this time not in Antwerp or Nuremberg but in Basel. The origins of this new prognostication do not lie in Basel, however. Its genesis traces to a decade earlier instead, to 1567 and the trauma inflicted on Dutch Calvinists in Antwerp.

The Horrible and Shocking Prophecy of Wilhelm Friess

In 1577, Wilhelm Friess had his second posthumous best seller when the printer Samuel Apiarius of Basel published a “horrible and shocking prophecy or prediction concerning Poland, Germany, Brabant, and France,” which had been “found in Maastricht with a God-fearing man, Wilhelm de Friess, after his death in 1577” (1–4; parenthetical references in this discussion indicate lines from the edition of the second prophecy in appendix 2).13 Friess’s name had appeared as “de Friess” only in the Lübeck and lost Dutch editions, which suggests that the L version was the specific catalyst for this new prophecy. While the pamphlets that Apiarius printed in Basel claimed to contain prophecies found in the same way and from the same author, the text of “Wilhelm Friess II,” or “Friess II” (as I will here designate this second prophecy), has little in common with “Wilhelm Friess I.” Its attitude toward the future and the contemporary political situation is fundamentally different. Instead of optimistically foreseeing the speedy fulfillment of traditional end-time expectations, the second prophecy of Wilhelm Friess is a nightmare vision of utter devastation from which only a few can hope to escape.

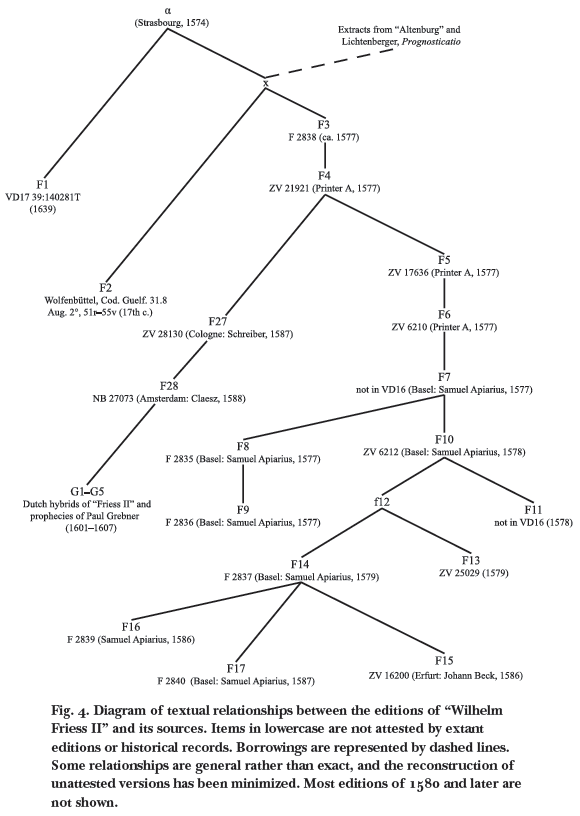

While “Wilhelm Friess I” describes future events and offers advice on how to prepare for them, the authorial voice of “Friess II” reports the narrator’s own visionary experience. Although the title page places the narrator’s residence in Maastricht in the Netherlands, the geographic site of “Friess II” clearly comprises the German-speaking lands. The text of the earliest edition printed by Apiarius (designated as F7 in appendix 3 and in figure 4, which appears later in this chapter) begins,

On 24 April 1577, as I lay on my bed awake at midnight, a beautiful young man came to me and said: “See what will happen and diligently take note of it.” Then I stood up, and immediately it seemed to me that I was on a high mountain in the middle of Germany. (cf. 15–18)

One of the few points of similarly between “Friess I” and “Friess II” is that both foresee invasion at hand. In “Friess I,” the false emperor and his allies attack from the west and east, while the narrator of “Friess II” sees an invasion approaching from four directions. Invasion was just one among many catastrophes predicted by the first prophecy, but the second prophecy makes invasion a singular and all-encompassing disaster.

Then the young man said to me, “Turn to the north. I will show you how terribly God will punish the world.” I did so, and I saw a great horde approaching Germany. They had many banners, riders, and foot soldiers. Their flags were black with white crosses, and they came to a great water. Then a large strong man rode to the front on a black horse. His clothing was covered in blood and he held a large horn in his hand. He said to his people, “You should halt and wait until we call our allies to join us.” And he blew the horn, and one heard it far and wide.

Then the young man said to me, “Turn and look toward the west,” and I did so and saw a large and terrible multitude drawing toward the north. They were fearsome and had many banners like the others, but their flags and clothing were white and red, with a red cross on them. One who looked like an evil spirit rode at their fore on a red horse. Lions and bears followed them and drove them forward ferociously and instantly attacked any who delayed. A clear voice went out among them saying, “Make haste to eat flesh.”

I was filled with such terrible fear that I became dizzy and was about to faint. Then the young man strengthened me and said, “Be comforted and do not despair, for I want to show you more.” He said to me, “Turn toward the east,” and I did so. There I saw again a horrible host journeying toward the north with riders and banners like the previous ones. Their banners were red with a fiery sword on them, and their clothes were also red and spattered with blood. A mighty armored man went to the front who was so large that I have never seen his equal, and his armor gleamed beyond all measure and had many golden letters on it. He called out ferociously to his folk, “Make haste, for we want to ruin their plans.” Then I asked the young man who that man was. He answered, “He is the Destroyer.” And I asked him again, “What are those letters written on him?” He answered, “All the plagues and punishments that he will carry out.” (cf. 19–46)

The title “Destroyer,” or Verderber, is otherwise used primarily for the Destroying Angel of the Passover account in sixteenth-century Bibles and devotional literature. This figure is both diabolic and divinely sanctioned.

And they made haste and quickly drew near. When they had come together, they made a plan and were all of one mind to punish and plague all lands. There was such a countless mass of people there that I was amazed there could be so many. I said to the young man, “Who can count this multitude or how many flags there are?” Then he said to me, “There is a great number of people, while the number of banners is one hundred sixty-four thousand.” And they armed themselves powerfully while they were on the water’s shore. (cf. 46–52)

Even the Destroyer is not the supreme leader of the horrors unleashed on Germany, however. After the three armies have arrived from the north, west, and east, a fourth host arrives from the northeast.

When they had gathered, a horrible and dreadful man came to them from the northeast. He had a dreadful host with him who did just as the bears had done, and they killed whomever they came upon except the people mentioned above who were without number. The army divided itself and let that horrible man proceed through their midst and take his place at their front. He held a golden cup full of blood in his right hand, and in his left hand he held a young child. (cf. 52–59)

The cup of blood and the child are then consumed in a cannibalistic desecration of the Eucharist.

He drank from the cup, and after that he ate for a time from the child. He did that so long until he had drained the cup and had eaten all but the child’s head. After that he took the cup and the child’s head and threw them down among the armies, and they trampled it with their feet. At that moment a bloody sword descended slowly from heaven, and he received it into his fist and cried with a loud voice, “Woe to you, Germany! Woe to you, Brabant and France! Woe to you, all lands! Woe to the Earth! O how happy is that person who has not given birth upon you, for I, your Destroyer, am coming and will not depart. Woe to the young men and young daughters! Woe to the proud lads and great lords, for the land will be filled with my hand.” And when he had said this, he departed and the entire host with him, and he killed and horribly mistreated all those he found. He did that so far and wide until it seemed to me that he was very close to me. (cf. 59–71)

The narrator faints and then awakens to an earth covered in blood.

Then I fell down and departed from myself, and I do not know how long I lay in that place. Then the young man came and took me by the hand and said, “Stand up, for it is finished.” I did so and looked far around me, but I saw no one alive. It seemed to me that the entire Earth was full of blood from the killing and murder that they had done.

Then I said to the young man, “Is there no one left alive on the Earth?” He said, “Turn to the south,” and I did so. There I saw a little gathering of people wearing black clothes drawing toward me. They carried white banners, and a fine honorable man with a gray beard led them. He had a golden book in his left hand and a golden trumpet in his right hand, and he blew it and let forth a mighty blast. Then a few survivors emerged from the dense bushes and from over the high mountains. They also put on black clothes and they sat together at a great water like the Rhine. The man who had the book taught them the fear of God from it, and he directed those who had been deceived onto the path of God. When he had finished teaching, they kneeled and prayed to God. Then the man stood up with all the people and said, “Let us depart from here and mourn the earth.” (cf. 71–88)

The final part of the vision warns the Romance-speaking nations and German nobility of a great tribulation that approaches.

O you Latin world, now begin to cry and wail, for great pain is approaching you because of your great sins. For the wind has whipped up a fire that cannot be quenched. Many people think that it does not concern them because they cling to both sides, but their backs will be bent in the same game. They take no heed that the time is coming and the fire begins to burn them. Perhaps they need a cook to prepare their food for them. Many Germans will gather when the fire begins to reach them and the smoke is upon them. No count or lord will be safe. They will feel the wind of the great storm. O how much blood will they shed among those who seek domination and want to rule unjustly. O Brabant, O France, O Germany! Cry and wail, you shepherds and rulers, and put off the clothes of joy. Clothe yourself with ashes and put on a hair shirt as if you were born with it and say, “I have raised and nurtured my people, but they have despised me. To me it has become like a lion that lies in wait for someone.” O you poor folk, what kind of strangers have risen up among you? They are not rulers but destroyers, not protectors but oppressors of orphans and widows throughout all Germany. It will seem to the Germans that it does not concern them, so that the common folk will say, “One is so and the other so.”

When these speeches were finished, the young man led me again to my room, and when I awoke the clock had struck four.14 (cf. 88–113)

While the horror of this vision is palpable, its precise meaning is not immediately clear, due partly to its use of opaque symbolism and partly to its original context being unknown. The sheer number of editions indicates that “Friess II” was a popular pamphlet, but the passage of time, the shift to Basel as the center of printing activity, and, above all, the entirely different text mean that the reasons for its popularity were much different than those for “Friess I.” Precisely what led customers to buy the two dozen editions over more than a decade is not immediately apparent. Barnes describes the second prophecy of Wilhelm Friess as a “complex and obscure vision about the nations of Christendom.”15

For the publication of “Friess II,” Samuel Apiarius of Basel played an even more dominant role than Georg Kreydlein did in publishing “Friess I.” Apiarius printed thirteen editions, half of all editions known, or at least one edition nearly every year between 1577 and 1588, almost always giving his name and the place of publication, while three further editions identify themselves as reprints of pamphlets first published in Basel (F13, F25, and F26). With twelve editions of “Friess II” known from a single copy, seven from two copies, and six editions known from three copies, we must again assume a significant number of missing editions.

While the title page of the earliest Basel edition (F7) lacks illustrations, Samuel Apiarius used woodcuts of several different kinds on the title pages of following editions. For another edition of 1577 (F8), Apiarius used two small woodcuts that show a dining monarch on the left and a man pouring out two decanters onto the ground on the right, above which he quoted 1 Thessalonians 5:19–21 (in the New Revised Standard Version, “Do not quench the Spirit. Do not despise the words of prophets, but test everything; hold fast to what is good”). Perhaps the two woodcuts contrast wise acceptance and foolish rejection, or they may illustrate the consumption of wisdom and rejection of vanity, but their function as a sober visual metaphor and encouragement of prudent reading practices is clear. For an edition of the following year (F10), however, Apiarius selected a woodcut that directly invoked the disaster predicted by “Friess II” (see figure 3). Retaining the same title formulation and motto, the woodcut shows a personified Germania raising her right hand to her head in distress while a group of armed women, identified as the Turkish menace by the cardinal direction oriens (east) and a banner with a crescent moon and star, approaches from the left. To the right, or west, a second group of women, identified by a banner with an imperial eagle, appears to be departing and casting back glances in derision. Below and to the north, another banner with a crescent moon and two stars marks a second front of Islamic threat. Above, or from the south, a comet, armed cavalry, and a papal crown dominate a sky filled with storm and stars. Later editions also depicted disaster on their title pages, such as two editions of 1579 (F13 and F14)—one from Apiarius and one a reprint from another press—that selected a scene of a city in flames and a fortress under siege beneath a zodiacal ram.

But these title woodcuts do not provide more than a surface interpretation of the text. To puzzle out what “Friess II” was trying to say and why it was so popular, we will have to start by disentangling its textual history. For all the effort of Samuel Apiarius, we will have to look beyond Basel and before 1577 to uncover the origins of the second prophecy of “Wilhelm Friess.”

The Textual History of Wilhelm Friess’s Second Prophecy

Unlike “Friess I,” the second prophecy of Wilhelm Friess exists in only a single version, so the relationships between editions can be depicted as a relatively uncomplicated family tree, and the textual differences are mostly less substantial than those of “Friess I.” Comparing the various editions of “Friess II” reveals only small discrepancies in the text until the end of the vision, where the differences are quite apparent. The larger discrepancies make it possible to reconstruct the textual history of “Friess II,” which, in turn, makes some of the prior, seemingly minor changes take on new significance.

At the conclusion of the vision in the 1577 editions of Samuel Apiarius, the honorable man from the south teaches the few survivors on the banks of the Rhine, leads them in prayer, enjoins them to depart and mourn the earth, and then pauses for a lengthy speech directed not at the survivors but, first of all, at the Romance-speaking lands. “O you Latin world, now begin to cry and wail,” the honorable man begins, apparently ignoring the band of survivors who had gathered around him. Then he harangues Brabant, France, and, above all, the German nobility, seemingly unaware that all these lands had just been utterly destroyed by demonic armies. This section of the honorable man’s speech seems incongruous for good reason: it was entirely lifted from two other works.

The first unmarked citation (88–98) consists of two unconnected passages from “Dietrich von Zengg,” a brief and highly obscure prophecy with scant scholarly literature.16 First attested in manuscript as early as 1465, the tract was relatively popular in print, with sixteen editions between 1503 and 1563.17 Most title pages attribute the prophecy to a Brother Dietrich, a Franciscan monk residing in what is now the Croatian town of Senj. The quotation in “Friess II” does not come from an edition attributed to any Brother Dietrich, however. Instead, the quotation closely follows a version of what is clearly the same text as “Dietrich von Zengg,” though it claims to be a prophecy written by a nameless Carmelite monk of Prague in the year 462 (perhaps 1462?) and allegedly found in Altenburg Castle in Austria. Two editions of this version were printed in 1522 and 1523 in Freiburg and Speyer, with two more, including the probable source of the citation, following in 1562 and 1563.

The citations from “Dietrich von Zengg” stop, but the honorable man’s speech continues. “O Brabant, O France, O Germany! Cry and wail, you shepherds and rulers,” he says. After calling on the nobility to clothe themselves in hair shirts and ashes, he refers to the rulers as foreigners and oppressors. The second half of the speech (98–106) seems like a tissue woven of biblical citations (see Jeremiah 25:34, 6:26; Isaiah 1:2; Jeremiah 12:8; Isaiah 1:23), but “Friess II” was not the first to weave them together. The second citation in the honorable man’s speech is a reworking of a passage from Lichtenberger’s Prognosticatio. The passage is not taken from the German version of the Prognosticatio first printed ca. 1490 but instead follows the text as it appeared in a new translation first published in 1527, an edition for which Martin Luther had provided a preface. This passage, like most else that appears in the Prognosticatio, is not original to Lichtenberger. It appeared at least as early as 1422 in an accusation, probably written by a Bohemian Catholic, against Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund’s manner of waging war against the Hussites. One hesitates to call even this the original source, as the author was explicitly collecting reports then in circulation.18

Recognizing the citations from “Dietrich von Zengg” and Lichtenberger in “Friess II” is the essential insight that allows us to reconstruct the history of the text. As the citations come as jarring intrusions into the honorable man’s speech, one suspects that they were added after the prophecy’s original composition. In the 1577 editions of Samuel Apiarius, however, the vision concludes immediately after the citation from Lichtenberger: the vision guide leads the narrator back to his room, where he awakes. If the citations of Lichtenberger and “Dietrich von Zengg” are indeed additions that displaced the end of the honorable man’s speech, one can surmise that there must have been an earlier state of the text that did not include the expansion.

1639: The Earliest and Latest Wilhelm Friess

There is, in fact, one edition (F1) that ends with the honorable man’s speech, uninterrupted by quotations from other prophecies. It concludes the speech with a passage that fits the preceding lines much better than the citations from “Dietrich von Zengg” and Lichtenberger: “For injustice has been taken from them. Let us also bury all those of ours who have died, for their souls rest in peace. Praised be the Lord our God, for his judgment is just” (109–11). The edition that concludes the speech in this way is also the one printed last, in 1639. Despite its late date, its updating of language that had become archaic, and its additional changes to the text, the 1639 edition is a witness of the earliest text of “Friess II.” The title page of the 1639 edition does not mention Friess or Maastricht but instead calls “Friess II” a “horrible and shocking old prophecy or vision about Germany” that a devout man living in Emden—a notable center of Dutch Reformed publishing in exile—had extracted on 23 February 1623 from an old manuscript written by a deceased notary. According to the title page, the prophecy had been printed in Dutch in 1638, but an edition in German was warranted because the significance of the prophecy and its fulfillment could be observed daily.19 In a foreword to the reader, the editor, who refers to himself only as “J. Schr.” and claims to have been trained in theology at Wittenberg, notes that an unnamed informant had read the same prophecy in German ten years earlier and that the close agreement of both versions was a sign of the vision’s reliability, as it had not suffered from corruption at the hands of uncomprehending copyists.20

The Second Generation

Two additional editions (F3 and F4) include both the citations from other prophecies and, following the passage from Lichtenberger, the rest of the honorable man’s speech as found in the 1639 edition. The two parts of the speech have been driven apart in these editions by the insertion of citations from other prophecies, much like the matching coastlines of distant continents that have been separated by tectonic expansion. Both of these editions were published anonymously, but F4 bears the date of 1577, while F3 is dated variously to 1580 in VD16 and to “ca. 1574” by the catalog of the Herzog August Bibliothek. The close agreement between the two editions suggests that ca. 1577 would be a better date for F3 as well. The same combination of texts, with the end of the honorable man’s speech following the two citations, is found in the one manuscript copy of “Friess II” (F2). This manuscript, dated to the seventeenth century and traceable to Augsburg, collects printed and manuscript curiosities, prophecies, and devotional works, along with printed broadsides and copperplate etchings.21 It seems to represent the same textual generation as F3 and F4 while not being a descendant of either one.

While reconstructing the textual history of “Friess I” was greatly aided by knowing its source text in the French redaction of the Vademecum, we lack that advantage with “Friess II,” apart from the two citations from other prophecies. For those passages, we can compare the editions of “Friess II” to the source texts, and we find not only that the F3 and F4 editions are more extensive than those of Samuel Apiarius but that they preserve the quotations from “Dietrich von Zengg” and Lichtenberger (88–106) more completely and accurately. Both editions also include an additional sentence following the citation from Lichtenberger and before the conclusion of the honorable man’s speech. This added passage places “Friess II” squarely in the context of Calvinist confessional rivalry with Lutheranism: “Also the Lutheran priests of the north will become so puffed up in haughtiness and greed and cause so much contention in matters of faith, but eventually it will go badly for them” (106–8). The author of at least this passage was determined to draw boundaries between his or her own branch of the Reformation and Lutheranism, whose clergy are referred to as the Leutersche Pfaffschap, little better than Catholic priests.22

Because of a few passages where F3 follows the 1639 edition while the text of F4 differs in ways also found in later editions, we will assign priority to F3. The anonymous printer of F4, “Printer A,” printed two more editions in 1577. (Based on the similarity of types used, it is not impossible that “Printer A” printed F3 as well, although the title woodcut of F3 differs from that used by “Printer A” for F4–F6.) The text of F5 and F6 differs in important ways from their predecessors, but it anticipates, in many ways, the text of “Friess II” as printed by Samuel Apiarius. One of the most notable changes occurred when a redactor removed the pointed remark about the Lutheran clergy but, wielding a dull scalpel, removed the end of the honorable man’s speech as well. The types and decorative material of “Printer A” may be those used after 1582 by Gerhard von Kempen in Cologne, but the source of von Kempen’s types is unknown, and “Printer A” remains stubbornly anonymous.23

Samuel Apiarius

Samuel Apiarius had established a printing workshop in Bern in 1554 and relocated to Solothurn in 1565, but he spent the majority of his printing career, from 1566 until his death in 1590, in Basel. The city had belonged to the Swiss Confederation since 1501 and had followed the Reformed branch of the Protestant Reformation for nearly a half century by the time Apiarius printed his first edition of “Friess II” in 1577. He took as his exemplar one of the later editions by “Printer A” (F6). What is likely Apiarius’s first edition (F7) introduced several changes found in all his later editions, but it otherwise followed the text of F6 closely. It was the only one of Apiarius’s editions to include two short prophecies—attributed to a sibyl and to Birgitta of Sweden—that are otherwise found only in the editions of “Printer A.” There are also a number of unique variants found in F7, however, so the textual history of “Friess II” in the vicinity of F7 may be somewhat more complicated than figure 4 indicates, or we might see here another case where a printer corrected later editions against the exemplar, as Johann Balhorn seems to have done with his second edition of “Friess I.” Just as with the Kreydlein editions of “Friess I,” the Apiarius editions of “Friess II” form a stable core of orderly succession from one edition to the next and a successful commercial product that other printers copied, but they represent the third stage in the edition history of “Friess II” (see figure 4). Like Georg Kreydlein, Samuel Apiarius reprinted and popularized as a commercial product a text that had already undergone several changes and that had previously only been printed anonymously.

With a better understanding of the textual history of “Friess II,” details that might, at first glance, be ascribed to a printer’s whim or a typesetter’s mistake turn out, instead, to be crucial for identifying the time and place of the prophecy’s origin. Material shared by the 1639 edition, the manuscript copy, or the anonymous editions previously mentioned (F1–F4) should be acknowledged as belonging to the original version of Wilhelm Friess’s second prophecy, even if omitted in all other editions, and several details of precisely this kind take on critical significance.

These editions all date the vision of “Friess II” not to 1577 but to 24 April 1574, so we will search for a historical context in that year. These editions also include a geographic point missing in all later editions: when the honorable man gathers the survivors to teach them on the shore of a great water like the Rhine, it seems to the narrator to be in the vicinity of Strasbourg (“und dauchte mich es ware umb Straßburg,” 84–85). The search for context will therefore center on that city. While the remark against the Lutheran clergy may not have been part of the original text, it was an early addition that indicates the religious convictions of the elements of German society among which the prophecy first circulated. The appearance of so many editions in the Reformed city of Basel is a further indication that we are dealing with a redactor—and likely an author as well—whose allegiance was more to Calvin than to Luther. Where the L version of “Friess I” had specifically rejected Calvinism, “Friess II” sided with Calvin against Luther. Just as we saw with the textual history of “Friess I,” the antipathy of the early redactor toward Catholicism did not stop him or her from reading and citing pre-Reformation German prophecies.

Although the F3 edition is undated, there is one more reason to give it precedence over other editions: it is the only one whose title page recognizes the astronomical symbolism on which the second prophecy of Wilhelm Friess is based.

The Stars over Strasbourg

By devouring a child, the demonic commander of the combined armies in “Friess II” reenacted the depiction of Saturn devouring his children, a well-known image that was the standard anthropomorphic icon for Saturn in early modern astrological pamphlets.24 The sword descending from heaven into his hand may be an allusion to the appearance of a comet. Astrologers were not reluctant to predict the appearance of comets as harbingers of doom, and contemporary sources record the appearance of comets in 1572, 1573, and 1574 (although mentions of a “comet” could refer to a variety of atmospheric and astronomical phenomena).25 In the same way, the mighty armored man from the east whose army carried red banners with fiery swords is an unambiguous reference to the iconography for Mars. The monstrous captain from the north who blows a horn is identifiable as Mercury, in this case bearing not his usual caduceus but the panpipes with which he lulled Argus to sleep. While most depictions of Mercury in the sixteenth century show him with his caduceus, the prognostication of Ambrosius Magirus for 1568 is one example that showed Mercury with both implements.26 The leader of the fourth army, who was followed by lions and bears, does not fit any planetary iconography, but the lions and bears may have been inspired by the rotund faces and fiery manes used to depict lunar or solar eclipses.

That, at least, is the configuration of heavenly bodies that the F3 edition selects for its title page (see figure 5): a conjunction featuring armored Mars and child-devouring Saturn to the left; Mercury, with his caduceus, in opposition to the right; and the figure of Justitia, a winged woman holding a scourge and scales, in the center. Below the gods, the title woodcut depicts an almost entirely eclipsed lunar disc and a partially eclipsed solar disc.

There is enough information in this title woodcut to firmly establish that it was meant to describe the configuration of the heavens in the year 1574. Mars and Saturn were in conjunction, near to each other in the night sky from the perspective of an earthly observer in August 1574. Conjunctions of these planets happen approximately every two years, so the woodcut would not fit the configuration of the heavens in 1577. According to the planetary tables of Cyprian Leowitz published in 1557, Mercury was expected to be in opposition to Mars and Saturn on 20 and 26 April 1574, respectively, just before and after the date of the narrator’s vision in “Friess II.”27 Contemporary astrologers saw the opposition as an ominous sign. Georg Winckler’s prognostication for 1574 states that the opposition of Saturn and Mercury will poison Mercury’s otherwise friendly influence, so that in matters of war and peace, the coming year will see “many vexing, miserable, and amazing things.” Winckler states that for the teachers of God’s Word, an eclipse portends things more ominous than he was willing to write. The movements of the planets in combination with the solar eclipse seemed so threatening, according to Winckler, that many learned people thought that the Last Judgment might be approaching or even that the end of the world had arrived.28 The title page of the F3 edition of the second Friess prophecy depicts eclipses of both the sun and the moon, and there was a partial solar eclipse visible in Germany on 13 November of that year, the only solar eclipse visible in Germany between 1567 and 1582. Like the eclipse of 1574, over half the sun’s disc is obscured in the title woodcut, while the eclipses of 1567 and 1582 were expected to darken the sun to a much greater (1567) or much lesser (1582) degree.29 There was no lunar eclipse in 1574, but contemporary astrologers emphasized that the lunar eclipse of 8 December 1573 would not exert its influence until the next year. While 1573 would be a fruitful and peaceful year, 1574 would be full of hate and enmity “because of the lunar eclipse that will occur on 8 December, which will show its effect in the following year.”30 Cyprian Leowitz noted in 1564 that Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn would be in opposition in the years 1573 and 1574, which, in combination with a solar eclipse, would have a dire effect on the weather and on human society. He predicted “unusual heat and dryness of the air, from which violent dissension between brothers, relatives, and neighbors will arise.” This is much the same scene as the lower plane of the title woodcut, where winds emanating from a face and a skull fall on a city in the background as two men draw swords against each other. In addition, Leowitz foresaw conspiracies and sedition, “savage military actions, conflagrations, and plundering and pillaging of fields, towns, castles, and cities,” as well as the deaths of princes, changes in policy and religion, and a particular threat to Spain.31

Almost no year went by without ominous astrological predictions of some kind, and every year offered a few dozen conjunctions and oppositions from which astrologers selected the most significant ones, yet the astronomical events depicted on the title page of F3 match both the actual configuration of the heavens in 1574 and contemporary astrological discussion of astral influences, so that it seems most likely that the title woodcut was made specifically for that year. It is possible that the woodcut was created first for an astrological prognostication and then used later for the edition of “Friess II.”32 It appears certain that this edition was printed by someone who had access to an early version of the text and who understood the connection of “Friess II” to the year 1574. The second prophecy of Wilhelm Friess is much more than a transformation into prose of that year’s planetary motions, and the translation of astrology into prophecy is, in any case, approximate rather than exact, but the title page of this edition is the only one to recognize the astronomical inspiration for the monstrous generals of “Friess II.”

The three editions of “Printer A” (F4–F6), including the edition that Apiarius took as his model, were all printed in 1577 but used a copy of the title woodcut from Victorin Schönfeld’s astrological prognostication for 1575 on their title pages.33 The scenes are mirror images of each other and show four armored men standing in groups of two. A reclining skeleton in the foreground holds up a skull and an hourglass as a reminder of death’s inevitability. In the background, an army marches on a distant town, upon which a face in the sky blows down destruction. The title woodcut for the three “Friess II” editions is arranged as a horizontal rectangle, rather than a vertical one, and it carefully erases the astrological iconography, including Mercury’s caduceus and winged shoes, the scepters held by the Sun and Moon, and the scorpion in the heavens and on the army’s banner. The title woodcut of the three “Printer A” editions therefore represents a transition from the F3 edition, whose astrological iconography corresponds to the text, to a generalized visual depiction of four armed men without identifying characteristics. The earliest editions of Samuel Apiarius, as we have seen, use title woodcuts that omit any reference to the four demonic leaders of the invading armies. Samuel Apiarius did not start decorating the title page with woodcuts of anthropomorphic planets (following the conventions of annual prognostications) until 1586, and he chose from a variety of planets: Saturn, the Sun, and Jupiter in 1586 (F16), followed by Mercury and Mars in the next year (F17).

Not only is the F3 edition closer to the source than Apiarius’s editions, but its choice of illustrations exhibits a better understanding of the text. Because of the significance of the year 1574 and the city of Strasbourg in the one manuscript copy, in the early F3 and F4 editions, and in the 1639 edition—and thus in the original text—the key to solving the riddle of the second prophecy of Wilhelm Friess lies in investigating what was going on in that time and place. There was, in fact, a man in Strasbourg who had a specific reason for considering the course of the planets, among his many other concerns, in late spring 1574.