In Part One, we examined the cultural roots of behavior and assessed the effects of cultural diversity on people’s lives and destinies. Part Two deals principally with the world of business and tackles head-on the issues and problems of international exchanges. The twenty-first century promises to be crunch time for powerful governments, trading blocs and manufacturing powerhouses. The hegemony enjoyed by Western Europe, the United States and Japan is no longer guaranteed. With six to seven billion consumers, the stakes are terrifyingly high. They include not only access to gigantic markets and astronomical profits, but also prospects of failure, recession, even survival.

Western and Japanese managers face enormous challenges. They have to come to grips with the problems posed by the rapid expansion of globalized trade and they have to abandon previous habits of arrogance and complacency. They have many economic weapons with which to defend themselves, but they are seriously outnumbered. It is imperative that Western and Japanese managers learn how to lead, manage, motivate and inspire their growing number of foreign staff and customers. This is attainable: the top level has gone global (at the time of writing a Frenchman runs Nissan), but this has to happen at many organizational levels. Contact among middle managers and international teams can lead to success or failure for many organizations. Is there such a thing as a global leadership style? Does it work in practice? What are its elements? How does one get there? Get there one must, as there is no alternative if Western managers wish to compete and survive.

Asian competition in the twenty-first century will be fierce and unrelenting. The Asians have endured centuries of playing second fiddle to the West; now they intend to reverse the situation. In many instances they have already done so. In industries such as textiles, garments, shoes, toys and plastics the West has no chance to compete, nor will it have in the future. In high-tech industries, especially consumer hardware, the West is already threatened by Malaysia, Thailand, Korea and Taiwan; China will ultimately replace these as the implacable competitor. How can the West fight all this?

The United States can be expected to widen its technological lead over competitors for another couple of decades, but not indefinitely. Finland, who in 2003 surpassed the U.S. in global competitiveness, may follow a similar path. Germany, Britain, France and Sweden, all high tech, will have to innovate constantly to stay ahead of Japan and China.

The West’s most effective weapons have to be dynamic leadership, perspicacity, psychological skills, willingness to innovate and clever use of their democratic institutions. A lot is achieved in the West in its clubs, societies, committees, charities, associations, sport and leisure activity groups, alumni fraternities and so on. The influence of such institutions, with their inherent social vibrancy, should not be underestimated and, furthermore, are hard for Eastern cultures to put a finger on.

There remains also the question of control of worldwide organizations such as the WTO, WHO, WWF, OECD, the World Bank, G8, the EU, NAFTA and NATO as well as substantial funding of the UN, UNESCO, UNICEF and so forth. Western control will eventually weaken, China has entered the WTO and countries with burgeoning populations play greater roles, but there is still a bit of breathing space for Western and Japanese managers and executives to confront cross-cultural issues, begin to understand others’ cultural habitats and learn how to stand in the shoes of foreign colleagues. If they do so, they at least stand a chance of influencing and leading the staff of Western companies in the East, such as those of IBM, Microsoft, Nokia, Unilever, Hewlett-Packard, Motorola and Volkswagen.

It is already late in the day for many organizations to begin this learning curve. Huge multinationals have avoided or postponed cultural training for decades. A few have excelled in their approach, such as Nokia, Ericsson, HSBC, Motorola, ABB, Coca Cola and Unilever.

Which national cultures are reluctant to learn about others? The problem lies with the Big Five, that is to say the globe’s biggest economies: the United States, Japan, Germany, Britain and France. These countries (and the companies originating in them) have been particularly insensitive in their handling of intercultural issues. The very size of their own economies endows them with a certain sense of complacency, but the problem runs deeper than that. Britain, France and Spain assumed that they could continue indefinitely the ways of Empire—with one language, one policy, one supreme authority, one educational system, one code of ethics, one jurisdiction, one way of doing business. One can see how convenient it was!

The United States and Japan fail consistently to understand others because of isolation or insularity, both geographical and mental. They wallow in powerful, all-encompassing “cultural black holes,” core beliefs of such gravity that they cannot be questioned (Lewis 2003). These cultural black holes prohibit intelligent or perceptive analysis of others’ cultures and agendas. If you swallow, hook, line and sinker, the concept of the American Dream, no other agenda is really worthwhile contemplating. If you devote your life to avoiding loss of face and affirm unswerving obedience to the Emperor, you can hardly be a free agent in assessing others’ values and ways of advancing (this means no disrespect to the Emperor of Japan, who happens to be far more enlightened and perceptive than most of the world’s executives).

With Germans, the problem is different again. On intercultural issues they are in advance of the other members of the Big Five, but they are so honest, frank and, consequently, tactless that they lack the delicacy to fully understand those who do not meet strict German (ethical and organizational) standards. But at least they try.

Smaller countries have no such impasses. They learned long ago that to play the game with the Big Boys, you had to play by their rules. The rules they learned differed from country to country, but they adapted to them, case by case, which meant that they aspired to multiculturalism. Consequently, Dutch, Belgians, Finns, Swedes, Danes and Swiss, and to a lesser extent Greeks, Hungarians, Czechs, the Baltic states and Norwegians, have studied and achieved a certain degree of empathy with the cultures of more powerful countries. Poles, Turks and Slovenians are beginning to go down the same track. In the Americas, Canada is an outstanding example of a successful and consciously multicultural society.

When it comes to competing for world markets in terms of understanding the aspirations of others, one can make significant comparisons as to how different national cultures are dealing with the issue.

1. Small Northern European countries—the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland and the Nordics—have intercultural skills and are performing well internationally (Nokia, Ericsson, Scania, Volvo, Carlsberg, Heineken, Shell, Unilever, Tetra-pak, Nestlé). Their impact on world trade is limited by their size.

2. Multicultural Canada has great future potential.

3. The Big Five—the United States, Japan, Germany, Britain and France—have a long way to go in learning about how to manage successfully across cultures.

4. The Latin countries, including France, Italy and Spain, are hampered by their inadequate level of English-language proficiency.

If we compare the performance of Asians in this respect, we see they are no laggards. They have not only learned English, but they have developed sensitivity toward the aspirations of Western consumers. In this they have been greatly aided by the existence and activity of millions of overseas Chinese and overseas Indians. Singapore and Hong Kong have had their own built-in advantages. Thais and Koreans have familiarized themselves with American cultural habits. Malaysians know the British well. The Philippines is the second largest English-speaking country in the world.

Japan’s successful penetration of Western markets took place in spite of poor intercultural skills. Rising labor costs and Chinese high-tech competition pose an imminent threat to the Japanese economy. Like the Americans, the Japanese are on the right side of a technological gap, which gives them a few years’ breathing space. Like the Americans, they will have to learn how to continue to project their success across borders by developing more intercultural sensitivity. The mammoth markets of the future—China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria and Brazil—have wildly different mindsets!

Leaders can be born, elected, or trained and groomed; they can seize power or have leadership thrust upon them. Leadership can be autocratic or democratic, collective or individual, merit-based or ascribed, desired or imposed.

It is not surprising that business leaders (managers) often wield their power in conformity with the national setup. For instance, a confirmed democracy like Sweden produces low-key democratic managers; Arab managers are good Muslims; Chinese managers usually have government or party affiliations.

Leaders cannot readily be transferred from culture to culture. Japanese prime ministers would be largely ineffective in the United States; American politicians would fare badly in most Arab countries; mullahs would not be tolerated in Norway.

Cross-national transfers are becoming increasingly common with the globalization of business, so it becomes even more imperative that the composition of international teams, and particularly the choice of their leaders, be carefully considered. Autocratic French managers have to tread warily in consensus-minded Japan and Sweden. Courteous Asian leaders have to adopt a more vigorous style in argumentative Holland and theatrical Spain if they wish to hold the stage. German managers sent to Australia are somewhat alarmed at the irreverence of their staff and their apparent lack of respect for authority.

In the twenty-first century, with multinationals and conglomerates expanding their global reach, corporate governance and international teams will learn a lot about leading multicultural enterprises and workforces. The new impetus provided by fresh managers from Asia, Russia, Poland, Hungary, East European states, Latin America and Africa will change notions of leadership as will the increasing number of women in management positions.

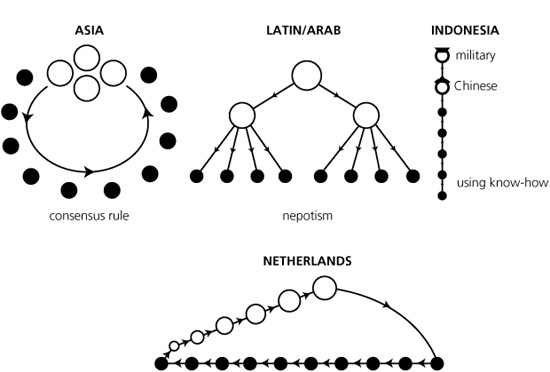

At cross-century, two of the world’s most respected leaders—Nelson Mandela and Kofi Annan—were African. The ultimate numerical superiority of non-white leaders, already significant in the political world, will permeate business. Based on Singapore’s commercial success and development within a given time frame, Lee Kuan Yew stakes a reasonable claim to have been the most successful “manager” of the last three decades of the twentieth century. His tenets were largely those enshrined in Asian precepts. This does not mean that Confucian rules are equally applicable everywhere. Lee concocted his own individual version of leadership style, not unaffected by his Cambridge education. The diagrams in Figures 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3 show some special and widely varying leadership styles.

The development of concepts of leadership is a historical phenomenon, closely connected with the organizational structure of society. Each society breeds the type of leader it wants, and expects him or her to keep to the path their age-old cultural habits have chosen.

The behavior of the members of any cultural group is dependent, almost entirely, on the history of the people in that society. It is often said that we fail to learn the lessons of history—and indeed we have seen mistakes repeated over hundreds of years by successive generations—but in the very long run (and we may be talking in millennia) a people will adhere collectively to the set of norms, reactions and activities which their experience and development have shown to be most beneficial for them. Their history may have consisted of good and bad years (or centuries), migrations, invasions, conquests, religious disputes or crusades, tempests, floods, droughts, subzero temperatures, disease and pestilence. They may have experienced brutality, oppression or near-genocide. Yet, if they survive, their culture, to some extent, has proven successful.

Besides being a creation of historical influence and climatic environment, the mentality of a culture—the inner workings and genius of the mindset—are also dictated by the nature and characteristics of the language of the group. The restricted liberties of thought that any particular tongue allows will have a pervasive influence on considerations of vision, charisma, emotion, poetic feeling, discipline and hierarchy.

Historical experience, geographic and geolinguistic position, physiology and appearance, language, instinct for survival—all combine to produce a core of beliefs and values that will sustain and satisfy the aspirations and needs of a given society. Based on these influences and beliefs, societal cultural conditioning of the members of the group is consolidated and continued, for as many generations as the revered values continue to assure survival and success. Infants and youth are trained by their parents, teachers, peers and elders. The characteristics of the group gradually emerge and diverge from those of other groups. Basic needs for food, shelter and escaping from predators are dealt with first. Social, economic and military challenges will ensue. Traumatic historical developments may also have an impact. For example, Japan’s samurai traditions, discredited in 1945–46, gave way to growing enthusiasm for success in industry and commerce.

At all events, in victory or defeat, in prosperity or recession, a society needs to organize, adapt and reorganize according to external pressures and its own objectives. Cultural groups organize themselves in strikingly different ways and think about such matters as authority, power, cooperation, aims, results and satisfaction in a variety of manners. The term organization automatically implies leadership, people in authority who write the rules for the system. There are many historical examples of leadership having been vested in the person of one man or woman—Alexander the Great, Tamerlane, Louis XIV, Napoleon, Queen Elizabeth I, Joan of Arc are clear examples. Others, equally renowned and powerful but less despotic (Washington, Bismarck, Churchill), ruled and acted with the acquiescence of their fellow statesmen. Parliamentary rule, introduced by the British in the early part of the seventeenth century, initiated a new type of collective leadership at government level, although this had existed at regional, local and tribal levels for many centuries. Minoan collective rule—one of the earliest examples we know about—inspired a similar type of leadership both in the Greek city–states and later in Rome. In another hemisphere, Mayan and North American Indians held similar traditions.

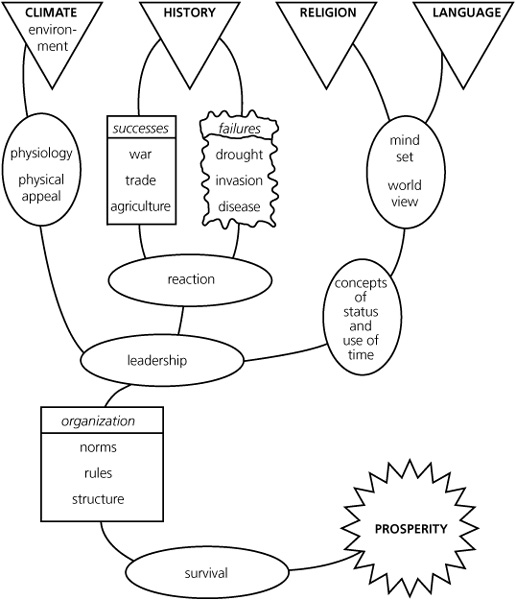

Figure 7.1 Factors Leading to the Organization of Society

In the business world, a series of individuals have also demonstrated outstanding abilities and success in leadership—Ford, Rockefeller, Agneli, Berlusconi, Barnevik, Gyllenhammer, Iacocca, Geneen, Matsushita and Morita are some of them. It is now common for leadership and authority also to be vested in boards of directors or management committees.

The way in which a cultural group goes about structuring its commercial and industrial enterprises or other types of organizations usually reflects to a considerable degree the manner in which it itself is organized. The two basic questions to be answered are these: (a) How is authority organized? and (b) What is authority based on? Western and Eastern answers to these questions vary enormously, but in the West alone there are striking differences in attitude.

There is, for instance, precious little similarity in the organizational patterns of French and Swedish companies, while Germans and Australians have almost diametrically opposing views as to the basis of authority. Organizations are usually created by leaders, whether the leadership is despotic, individual or collective. Leadership functions in two modes—networking and task orientation. In networking mode, the concerns, in order of appearance, are the status of the leader(s), the chain of command, the management style, the motivation of the employees, and the language of management used to achieve this. In task-orientation mode, the leadership must tackle issues, formulate strategies, create some form of work ethic and decide on efficiency, task distribution and use of time.

Managers in linear-active cultures will generally demonstrate a task orientation. They look for technical competence, place facts before sentiment, logic before emotion; they will be deal oriented, focusing their own attention and that of their staff on immediate achievements and results. They are orderly, stick to agendas and inspire staff with their careful planning.

Multi-active managers are much more extroverted, rely on their eloquence and ability to persuade and use human force as an inspirational factor. They often complete human transactions emotionally, assigning the time this may take—developing the contact to the limit. Such managers are usually more oriented to networking.

Leaders in reactive cultures are equally people oriented but dominate with knowledge, patience and quiet control. They display modesty and courtesy, despite their accepted seniority. They excel in creating a harmonious atmosphere for teamwork. Subtle body language obviates the need for an abundance of words. They know their companies well (having spent years going around the various departments); this gives them balance, the ability to react to a web of pressures. They are also paternalistic.

Because of the diverse values and core beliefs of different societies, concepts of leadership and organization are inevitably culture-bound. Authority might be based on achievement, wealth, education, charisma or birthright (ascription). Corporations may be structured in a vertical, horizontal or matrix fashion and may be molded according to religious, philosophical or governmental considerations and requirements. No two cultures view the essence of authority, hierarchy or optimum structure in an identical light.

Germans believe in a world governed by Ordnung, where everything and everyone has a place in a grand design calculated to produce maximum efficiency. It is difficult for the impulsive Spaniard, the improvising Portuguese or the soulful Russian to conceive of German Ordnung in all its tidiness and symmetry. It is essentially a German concept which goes further in its theoretical perfection than even the pragmatic and orderly intent of Americans, British, Dutch and Scandinavians.

Just as they believe in simple, scientific truth, Germans believe that true Ordnung is achievable, provided that sufficient rules, regulations and procedures are firmly in place. In the business world, established, well-tried procedures have emerged from the long experience of Germany’s older companies and conglomerates, guided by the maturity of tested senior executives. In Germany, more than anywhere else, there is no substitute for experience. Senior employees pass on their knowledge to people immediately below them. There is a clear chain of command in each department and information and instructions are passed down from the top. The status of managers is based partly on achievement, but this is seen as interwoven with the length of service and ascribed wisdom of the individual, as well as formal qualifications and depth of education.

German management is, however, not exclusively autocratic. While the vertical structure in each department is clear, considerable value is placed on consensus. German striving for perfection of systems carries with it the implication that the manager who vigorously applies and monitors these processes is showing faith in a framework which has proved successful for all. Although few junior employees would question the rules, there is adequate protection in German law for dissenting staff. Most Germans feel comfortable in a rather tight framework which would irritate Americans and British. Germans welcome close instruction: they know where they stand and what they are expected to do. They enjoy being told twice, or three or four times.

German managers, issuing orders, can motivate by showing solidarity with their staff in following procedures. They work long hours, obey the rules themselves and, although they generally expect immediate obedience, they insist on fair play.

In task orientation, Germany’s use of time resembles the American: meetings begin on the dot, appointments are strictly observed, late arrivals must be phoned in prior to the appointed arrival time. A strong work ethic is taken for granted, and although staff working hours are not overlong and holidays are frequent, the German obsession with completing action chains means that projects are usually completed within the assigned period. Each department is responsible for its own tasks and there is far less horizontal communication between equals across the divisions of a German company than there is in U.S. and British firms. Secrecy is respected in Germany both in business and private. Few German companies publish their figures for public consumption or even for the benefit of their own employees.

Latins and some Anglo-Saxons frequently experience some difficulty in working or dealing with Germans on account of the relatively rigid framework of procedures within which many German companies operate.

Cooperating successfully with Germans means respecting their primary values. First, status must be established according to their standards. Efficiency and results will win the day in due course, but a foreign national must have adequate formal qualifications to make an initial impression. Punctuality and orderliness are basic; get there first and avoid sloppiness or untidiness in appearance, behavior and thought. Procedures should always be written down, for Germans read them, and so should you. Any instructions you issue should be firm and unambiguous. If you want something written in black ink, not blue, then you should make this clear. Germans want content, detail and clarity—they hate misunderstandings.

Strive for consensus at all times. Consensus is obtained by clarification and justification, not by persuasion or truly open discussion. Consensus creates solidarity, which makes everyone feel comfortable. Each participant in the discussion makes a contribution, but does not query a superior too energetically and certainly does not question his or her judgment.

Hierarchical constraints necessitate your knowing the exact pecking order in the ladder of command, including your own rung. German directness enables you to point out when something is being done in an incorrect manner or when mistakes are being made, as long as the criticism is clearly constructive or designed to help. If you are too subtle in your criticism, it may not register at all.

Subordinates with difficulties should be supervised, helped, advised, instructed, monitored. If no help is asked for or required, tasks should not be interrupted. Quiet single-mindedness is admired in Germany, so don’t try to do six things at once, and don’t leave anything unfinished. If you are working hard, show it; a casual approach will be misunderstood.

Finally, communication is vertical, not horizontal. Don’t go across the company to chat with people at your level in other departments. Most of your business ideas should be communicated to either your immediate superior or immediate subordinate. You do not have the ear of the chairman, however benignly he may smile at you—unless you are vice chairman.

French management style is more autocratic than the German, although this is not always evident at first glance. In France the boss often seems to have a roving style, using tu to subordinates and often patting them on the back. Such behavior is, however, quite deceptive.

The French chief executive’s status is attributed according to family, age, education and professional qualifications, with the emphasis on oratorical ability and mastery of the French language. Preferably the executive was “finished” at the École normale supérieure, an elitist establishment way ahead in prestige of any French university. French managers have less specialization than U.S. or British managers, but they generally have wider horizons and an impressive grasp of the many issues facing their company. They can handle production, organizational procedures, meetings, marketing, personnel matters and accounting systems as the occasion requires.

French history has spawned great leaders who have often enjoyed (frequently with little justification) the confidence of the nation. Napoleon and Pétain are remembered for their heroics rather than for their disasters; Louis XIV, Joan of Arc, Charles de Gaulle, and André Malraux were charismatic figures who excited the French penchant for panache and smashed the mediocrity and mundanity that surrounded them. Ultimate success in French culture is less important than the collective soaring of the national pulse—the thrill of the chase or crusade. French failures are always glorious ones (check with Napoleon Bonaparte).

While mistakes by German executives are not easily forgiven and American managers are summarily fired if they lose money, there is a high tolerance in French companies for management blunders. As management is highly personalized, it falls on the manager to make many decisions on a daily basis, and it is expected that a good proportion of them will be incorrect. The humanistic leanings of French and other Latin-based cultures encourage the view that human error must be anticipated and allowed for. Managers assume responsibility for their decisions, but it is unlikely that they will be expected to resign if these backfire. If they are of the right age and experience and possess impeccable professional qualifications, replacing them would not only be futile, it would point a dagger at the heart of the system. For the French, attainment of immediate objectives is secondary to the ascribed reputation of the organization and its sociopolitical goals. The highly organic nature of a French enterprise implies interdependence, mutual tolerance and teamwork among its members as well as demonstrated faith in the (carefully) appointed leader. French managers, who relish the art of commanding, are encouraged to excel in their work by the high expectations on the part of their subordinates.

Such expectation produces a paternalistic attitude among French managers (not unlike that demonstrated by Japanese, Malaysian and other Asian executives), and they will concern themselves with the personal and private problems of their staff.

In addition to their commercial role in the company, French managers see themselves as valued leaders in society, indeed, as contributing to the well-being of the state itself. Among the largest economies of the world, only Japan exercises more governmental control over business than the French. Modern French companies such as Aérospatiale, Dassault, Elf Aquitaine, Michelin, Renault and Peugeot are seen as symbols of French grandeur and are “looked after” by the state. A similar situation exists in Japan and to some extent Sweden.

The prestige and exalted position enjoyed by the French manager is not without its drawbacks, both for the enterprise and for the national economy. By concentrating authority around the chief executive, opinions of experienced middle managers and technical staff (often close to customers and markets) do not always carry the weight that they would in Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian companies. It is true that French managers debate issues at length with their staff, often examining all aspects in great detail. The decision, however, is usually made alone and not always on the basis of the evidence. If the chief executive’s views are known in advance, it is not easy to reverse them. Furthermore, senior managers are less interested in the bottom line than in the perpetuation of their power and influence in the company and in society. Again, their contacts and relationships at the highest levels may transcend the implications of any particular transaction.

The feudal and imperial origins of status and leadership in England are still evident in some aspects of British management. A century has passed since Britain occupied a preeminent position in industry and commerce, but there still lingers in the national consciousness the proud recollection of once having ruled 15 million square miles of territory on 5 continents.

The class system persists in the U.K., and status is still derived, in some degree, from pedigree, title and family name. There is little doubt that the system is on its way to becoming a meritocracy—the emergence of a very large middle class and the efforts of the Left and Centrist politicians will eventually align British egalitarianism with that of Northern Europe.

British managers could be described as diplomatic, tactful, laid back, casual, reasonable, helpful, willing to compromise and seeking to be fair. They also consider themselves to be inventive and, on occasion, lateral thinkers. They see themselves as conducting business with grace, style, humor, wit, eloquence and self-possession. They have the English fondness for debate and regard meetings as occasions to seek agreement rather than to issue instructions.

Under the veneer of casual refinement and sophistication in British management style there exists a hard streak of pragmatism and mercenary intent. When the occasion warrants it, British managers can be as resilient and ruthless as their tough American cousins, but less explicitly and with disarming poise. Subordinates appreciate their willingness to debate with them and the tendency to compromise, but they also anticipate a certain amount of deviousness and dissimulation. Codes of behavior within a British company equip staff to absorb and cope with a rather obscure management style.

Other problems arise when British senior executives deal with European, American and Eastern businesspeople. In spite of their penchant for friendliness, hospitality and desire to be fair, British managers’ adherence to tradition endows them with an insular obstinacy resulting in a failure to comprehend differing values in others.

Although British delegates at international meetings frequently distinguish themselves by their poise, charm and eloquence, they often leave the scene having learned little or nothing from their more successful trading partners. As such conferences are usually held in English, they easily win the war of words; this unfortunately increases their linguistic arrogance.

I once gave a series of cross-cultural seminars to executives of an English car company that had been taken over by a German auto industry giant. The Germans attending the seminars, although occasionally struggling with terminology, listened eagerly to the remarks about British psychology and cultural habits. The British participants, with one or two notable exceptions, paid only casual attention to the description of German characteristics, took hardly any notes, were unduly flippant about Germany’s role in Europe and thought the population and the gross domestic product (GDP) of the two countries were roughly equal. Only one of the British spoke German and that at a very modest level.

As far as task orientation is concerned, British managers perform better. They are not sticklers for punctuality, but time wasting is not endemic in British companies, and staff take pride in completing tasks thoroughly, although in their own time frame. British managers like to leave work at 5:00 or 6:00 P.M., as do their subordinates, but work is often taken home.

As for strategies, managers generally achieve a balance between short- and long-term planning. Interim failures are not unduly frowned on and there are few pressures to make a quick buck. Teamwork is encouraged and often achieved, although it is understood that individual competition may be fierce. It is not unusual for managers to have “direct lines” to staff members, especially those whom they favor or consider intelligent and progressive. Chains of command are observed less than in German and French companies. The organization subscribes in general to the Protestant work ethic, but this must be observed against a background of smooth, unhurried functions and traditional self-confidence.

The contrast with the immediacy and driving force of American management is quite striking when one considers the commonality of language and heritage as well as the Anglo-Celtic roots of U.S. business.

The Puritan work ethic and the right to dissent dominated the mentality of the early American settlers. It was an Anglo-Saxon-Celtic, Northern European culture, but the very nature and hugeness of the land, along with the advent of independence, soon led to the “frontier spirit.”

The vast lands of America were an entrepreneur’s dream. Unlimited expanses of wilderness were seen as unlimited wealth which could be exploited, if one moved quickly enough. Only Siberia has offered a similar challenge in modern times.

The nature of the challenge soon produced American values: speed was of the essence; you acted individually and in your own interest; the wilderness forced you to be self-reliant, tough, risk taking; you did not easily cede what you had claimed and owned; you needed to be aggressive against foreign neighbors; anyone with talent and initiative could get ahead; if you suffered a setback, it was not ultimate failure, there was always more land or opportunity; bonds broken with the past meant that future orientation was all important; you were optimistic about change, for the past had brought little reward; throwing off the yoke of the King of England led to a distrust of supreme authority.

American managers symbolize the vitality and audacity of the land of free enterprise. In most cases they retain the frontier spirit that has characterized the U.S. mindset since the end of the eighteenth century: they are assertive, aggressive, goal and action oriented, confident, vigorous, optimistic and ready for change. They are achievers who are used to hard work, instant mobility and decision making. They are capable of teamwork and corporate spirit, but they value individual freedom above the welfare of the company, and their first interest is furthering their own career.

In view of their rebellious beginnings, Americans are reluctant to accord social status to anyone for reasons other than visible achievement. In a land with no traditions of (indeed aversion to) aristocracy, money was seen as the yardstick of progress, and very few Americans distance themselves from the pursuit of wealth. Intellectuality and refinement as qualities of leadership are prized less in the United States than in Europe. Leadership means getting things done, improving one’s standard of living by making money for oneself, finding shortcuts to prosperity and making a profit for one’s firm and its shareholders.

With status accorded almost exclusively on grounds of achievement and wealth, age and seniority assume less importance. American managers are often young, female or both. Chief executives are given responsibility and authority and then expected to act; they seldom fail to do so. How long they retain power depends on the results they achieve.

Motivation of American managers and their staff does not have the labyrinthine connotations that it does in European and Asian companies, for it is usually monetary. Bonuses, performance payments, profit-sharing schemes and stock options are common. New staff, however, are often motivated by the very challenge of getting ahead. Problem solving, the thrill of competition and the chance to demonstrate resolute action satisfy the aspirations of many young Americans. Unlike Europeans and Asians, however, they need constant feedback, encouragement and praise from the senior executive.

In terms of organization, the rampant individualism in American society is rigidly controlled in business life through strict procedures. American executives are allowed to make individual decisions, especially when traveling abroad, but usually within the framework of corporate restrictions. Young Americans’ need for continual appraisal means that they are constantly supervised. In German companies staff are regularly monitored, but German seniors do not “hover.” In the United States senior executives pop in and out of offices, sharing information and inspiration with their subordinates: “Say, Jack, I’ve just had a terrific idea.” Memos, directives, suggestions in writing are ubiquitous. Shareholder pressure makes quarterly reporting and rolling forecasts imperative. The focus is on the bottom line.

American managers can be quickly hired and just as rapidly fired (often without compensation). Being sacked often carries less stigma than elsewhere: “It just didn’t work out, we have to let you go.” For the talented, other jobs and companies beckon. There is precious little sentimentality in American business. The deal comes before personal feeling. If the figures are right, you can deal with the Devil. If there is no profit, a transaction with a friend is hardly worthwhile. Business is based on punctuality, solid figures, proven techniques, pragmatic reasoning and technical competence. Time is money, and Americans show impatience during meetings if Europeans get bogged down in details or when Asians demur in showing their hand.

Europeans, by contrast, are often miffed by American informality and what they consider to be an overly simplistic approach toward exclusively material goals. Eastern cultures are wary of the litigious nature of American business (two-thirds of the lawyers on earth are American), a formidable deterrent for members of those societies who settle disputes out of court and believe in long-term harmony with their business partners.

The Swedish concept of leadership and management differs considerably from other European models and is dealt with in some detail in Chapter 20. Like Swedish society itself, enterprises are essentially “democratic,” although a large percentage of Swedish capital is in private hands. Managers of thousands of middle-sized and even large firms have attained managerial success through subtle self-effacement, but the big multinationals have also thrown up some famous executives who might well claim to be among the most far-seeing business leaders in the world: Carstedt, Gyllenhammar, Wennergren, Barnevik, Carlzon, Wallenberg, and Svedberg.

Modern Swedish egalitarianism has age-old cultural roots. Although some historical Swedish monarchs such as Gustav av Vasa and Charles the Great were dominating, compelling figures, the Swedish royals, like those of Denmark and Norway, have espoused democratic principles for many centuries, no doubt mindful of the old Viking lagom tradition, when warriors passed round the drinking horn (or huge bowl) in a circle and each man had to decide what amount to drink. Not too little to arouse scorn; not too much to deprive others of the liquid.

The business cultures of Italy, Spain and Portugal are described in later chapters. In Latin Europe, as well as in South America, the management pattern generally follows that of France, where authority is centered around the chief executive. In middle-sized companies, the CEO is very often the owner of the enterprise and even in very large firms a family name or connections may dominate the structure. More than in France, sons, nephews, cousins and close family friends will figure prominently in key positions. Ubiquitous nepotism means that business partners are often confronted with younger people who seem to have considerable influence on decision making. Delegations may often consist of the company owner, flanked by his brother, son, cousin or even grandson. Women are generally, although not always, excluded from negotiating sessions.

Status is based on age, reputation and often wealth. The management style is autocratic, particularly in Portugal, Spain and South America, where family money is often on the line. There is a growing meritocracy in Brazil, Chile and in the big Northern Italian industrial firms, but Latin employees in general indicate willing and trusting subservience to their “establishments.”

Task orientation is dictated from above; strategies and success depend largely on social and ministerial connections and mutually beneficial cooperation between dominant families. Knowing the right people oils the wheels of commerce in Latin countries, just as it does in Arab and Asian cultures. It helps anywhere, but assumes greater importance in those societies that prioritize nurturing human relationships over pragmatic, rapid implementation of transactions based on mere notions of opportunity, technical feasibility and profit.

Leadership in the Netherlands is based on merit, competence and achievement. Managers are vigorous and decisive, but consensus is mandatory, as there are many key players in the decision-making process. Long “Dutch debates” lead to action, taken at the top, but with constant reference to the “ranks.” Ideas from low levels are allowed to filter freely upward in the hierarchy.

In colonial times, leadership came from the Dutch. Under Sukarno and Suharto leadership was exercised principally by the military and was therefore autocratic. The indifferent nature of many Indonesians to the business process has, however, resulted in a lot of business management being entrusted to a resident Chinese professional class, which has the commercial know-how and international connections. Overseas Chinese shareholding in many Indonesian companies encourages this situation.

Japanese top executives have great power in conformity with Confucian hierarchy, but actually have little involvement in the everyday affairs of the company. On appropriate occasions they initiate policies that are conveyed to middle managers and rank and file. Ideas often originate on the factory floor or with other lower-level sources. Signatures are collected among workers and middle managers as suggestions, ideas and inventions make their way up the company hierarchy. Many people are involved. Top executives take the final step in ratifying items that have won sufficient approval.

The leadership concept is undergoing profound changes in Russia following the demise of the Soviet Communist state. Efforts made by managers to promote business through official channels only are likely to founder on the rocks of bureaucracy and Russian apathy. Using key people and personal alliances, the “system” is often bypassed and a result achieved.

Finnish leaders, like many British leaders, exercise control from a position just outside and above the ring of middle managers, who are allowed to make day-today decisions. Finnish top executives have the reputation of being decisive at crunch time and do not hesitate to stand shoulder to shoulder with staff and help out in crises.

Australian managers, like Swedes, must sit in the ring with the “mates.” From this position, once it is accepted that they will not pull rank, they actually exert much more influence than their Swedish counterparts, as the semi-Americanized nature of Australian business requires quick thinking and rapid decision making.

Spanish leaders, like French, are autocratic and charismatic. Unlike the French, they work less from logic than from intuition, and pride themselves on their personal influence on all their staff members. Possessed often of great human force, they are able to persuade and inspire at all levels. Nepotism is also common in many companies. Declamatory in style, Spanish managers often see their decisions as irreversible.

Nepotism is also rife in traditional Indian companies. Family members hold key positions and work in close unison. Policy is also dictated by the trade group, e.g. fruit merchants, jewelers, etc. These groups work in concert, often develop close personal relations (through intermarriage, etc.) and come to each other’s support in difficult times.

Cultural values dominate the structure, organization and behavior of Eastern enterprises more than in the West, because deeply rooted religious and philosophical beliefs impose near-irresistible codes of conduct.

In the Chinese sphere of influence—People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore—as well as in Japan and Korea, Confucian principles hold sway. (Thailand is Buddhist; Indonesia and Malaysia, strongly Muslim.) Although national differences account for variations in the concepts of status, leadership and organization, there is a clearly discernible “Eastern model” that is compatible with general Asian values. The Confucian model, whether applied to corporations, departments of civil service or government, strongly resembles family structure.

Confucianism, which took final shape in China in the twelfth century, designated family as the prototype of all social organization. We are members of a group, not individuals. Stability of society is based on unequal relationships between people, as in a family. The hierarchies are father–son, older brother–younger brother, male–female, ruler–subject, senior friend–junior friend. In the past, loyalty to the ruler, filial piety to one’s father and right living would lead to a harmonious social order based on strict ethical rules and headed up in a unified state, governed by men of education and superior ethical wisdom. Virtuous behavior, protection of the weak, moderation, calmness and thrift were also prescribed.

Confucianism entered Japan with the first great wave of Chinese influence between the sixth and ninth centuries A.D. For some time it was overshadowed by Buddhism, but the emergence of the centralized Tokugawa system in the seventeenth century made it more relevant than it had been before. Both Japan and Korea had become thoroughly Confucian by the early nineteenth century in spite of their feudal political systems. In the twentieth century the Japanese wholeheartedly accepted modern science, universalistic principles of ethics, as well as democratic ideals, but they are still permeated, as are the Koreans, with Confucian ethical values. While focusing on progress and growth, strong Confucian traits still lurk beneath the surface, such as the belief in the moral basis of government, the emphasis on interpersonal relationships and loyalties, the faith in education and hard work. Few Japanese and Koreans consider themselves Confucianists today, but in a sense almost all of them are.

What do these cultural influences mean in terms of status and leadership today? Japanese and Korean business leaders today flaunt qualifications, university and professorial connections more than family name or wealth. Many of the traditional Japanese companies are classic models of Confucian theory, where paternalistic attitudes to employees and their dependants, top-down obligations, bottom-up loyalty, obedience and blind faith are observed to a greater degree than in China itself. Prosperity makes it easier to put Confucianism into practice: in this regard Japan has enjoyed certain advantages over other countries. The sacred nature of the group and the benevolence attributed to its leaders, however, permeate Asian concepts of organization from Rangoon to Tokyo.

Japanese top executives today, although they have great power in conformity with Confucian hierarchy, actually have little involvement in the everyday affairs of the company. On appropriate occasions they initiate policies which are conveyed to middle managers and the rank and file. Ideas often originate on the factory floor or with other lower-level sources. Signatures are collected among workers and middle managers as suggestions, ideas and inventions make their way up the company hierarchy. Top executives take the final step in ratifying items that have won sufficient approval.

In Buddhist Thailand and Islamic Malaysia and Indonesia, slight variations in the concept of leadership do little to challenge the idea of benign authority. Thais see a strict hierarchy with the King at its apex, but there is social mobility in Thailand, where several monarchs had humble origins. The patronage system requires complete obedience, but flexibility is assured by the Thai principle that leaders must be sensitive to the problems of their subordinates and that blame must always be passed upward. Bosses treat their inferiors in an informal manner and give them time off when domestic pressures weigh heavily. Subordinates like the hierarchy. Buddhism decrees that the man at the top earned his place by meritorious performance in a previous life.

In Malaysia and Indonesia status is inherited, not earned, but leaders are expected to be paternal, religious, sincere and above all gentle. The Malay seeks a definite role in the hierarchy, and neither Malaysians nor Indonesians strive for self-betterment. Promotion must be initiated from above; better conformity and obedience than struggling for change. Age and seniority will bring progress.

Although Confucianism, Buddhism and Islam differ greatly in many respects, their adherents see eye-to-eye in terms of the family nature of the group, the noncompetitive according of status, the smooth dispersal of power, the automatic chain of command and the collective nature of decision making. There are variations on this theme, such as the preponderance of influence among certain families in Korea, governmental intervention in China, the tight rein on the media in Singapore and fierce competition and individualism among the entrepreneurs of Hong Kong. Typical Asians, however, acknowledge that they live in a high-context culture within a vital circle of associations from which withdrawal would be unthinkable. Their behavior, both social and professional, is contextualized at all times, whether in the fulfillment of obligations and duties to the group (families, community, company, school friends) or taking refuge in its support and solidarity. They do not see this as a trade-off of autonomy for security, but rather as a fundamental, correct way of living and interacting in a highly developed social context.

In a hierarchical, family-type company, managers guide subordinates and work longer hours as a shining example. As far as task orientation is concerned, immediate objectives are not as clearly expressed as they would be in, for example, an American company. Long-term considerations take priority and the slow development of personal relationships, both internally and with customers, often blur real aims and intent. Asian staff seem to understand perfectly the long-term objectives without having to have them spelled out explicitly. In Japan, particularly, staff seem to benefit from a form of corporate telepathy—a consequence of the homogeneous nature of the people.

The work ethic is taken for granted in Japan, Korea and China, but this is not the case throughout Asia. Malaysians and Indonesians see work as only one of many activities that contribute to the progress and welfare of the group. Time spent (during working hours) at lunch, on the beach or playing sports may be beneficial in deepening relationships between colleagues or clients. Time may be needed to draw on the advice of a valued mentor or to see to some pressing family matter that was distracting an employee from properly performing their duties. Gossip in the office is a form of networking and interaction. Work and play are mixed both in and out of the office in Thailand, where either activity must be fun or it is not worth pursuing. Thais, like Russians, tend to work in fits and starts, depending partly on the proximity of authority and partly on their mood. Koreans, all hustle and bustle when compared to the methodic Japanese, like to be seen to be busy all day long and of all Asians most resemble the Americans in their competitive vigor.

Asian management attaches tremendous importance to form, symbolism and gesture. The showing of respect, in speech and actions, to those higher in the hierarchy is mandatory. There must be no loss of face, either for oneself or one’s opponent, and as far as business partners are concerned, red carpet treatment, including lavish entertaining and gift giving, is imperative. Ultimate victory in business deals is the objective, but one must have the patience to achieve this in the right time frame and in the correct manner. This attitude is more deeply rooted among the Chinese and Japanese than in Korea, where wheeling and dealing is frequently indulged in.

Is the Asian “family model” efficient? The economic success of Japan and the rates of growth in China, Korea, Malaysia and Taiwan, among others, would indicate that it is. Whatever the reality may be, it will not be easy for Westerners to convert to Asiatic systems. Individualism, democratic ideals, material goals, compulsive consumerism, penchant for speed, environmental concerns and a growing obsession with the quality of life (a strange concept in Asia) are powerful, irreversible factors to be reckoned with in North America and Northern Europe. The globalization process and the increasing determination of the multinational and transnational giants to standardize procedures will result in some convergence between East and West in terms of goals, concepts and organizational structure, but divergence in values and worldview will sustain organizational diversity well into the twenty-first century.