Of all the ways to lose money, the saying goes, gambling may be the fastest, but investing in cattle is the most guaranteed. Fortunately, there is almost always a way to vastly improve the profitability of any grazing livestock enterprise, because the average level of grazing management is — to put it bluntly — poor. As you proceed through this book, I hope that you will find hundreds of ideas that can drastically improve profit on your own operation.

I started college as an engineering major, chasing the money. I did not really want to be an engineer, but the military rejected me due to my severe allergies, and college was the next-best option. I had to major in something, and with no idea what I wanted to do, I simply looked at the earnings for recent graduates. Engineering was at the top of the list, so engineering it was.

As it turned out, engineering was not what I was interested in. All of my roommates were agriculture majors, and I listened to them talk about what they covered in class every day and argue about which cattle breeds were best, which tractor brand was best, what soil-management method was best. The different ways to solve an integration problem in calculus were not nearly so interesting.

I grew up on a farm, but all it ever seemed to be was endless work. I never really thought about what I was doing or why. All of a sudden, agriculture had become interesting to this college freshman. More specifically, the integration of science with agriculture to find better ways of producing food became fascinating. I had always been drawn to science and nature, but I had never really associated farming with either.

Just out of interest, I began taking a few agriculture classes, and since I had always enjoyed working with our cattle more than “dirt farming,” I started out with animal science.

I remember the first day of Beef Science class. The professor strongly emphasized calculating breakevens and cost of production. He put on the board the average costs per weaned calf, by category. Every category except one, combined, added up to 20 percent of all costs. That one remaining category, feed costs, made up the other 80 percent. The professor said that was why they made animal science majors take a couple of agronomy courses, so that we could learn to raise cheaper feed.

A light bulb went on in my head. If all of my animal science classes covered the 20 percent, and agronomy classes covered the 80 percent, perhaps if I wanted to raise cattle I should change my major. I walked over to the agronomy building, introduced myself to the first professor I found, and the rest is history — or at least my own personal story.

Unfortunately, ranching is not the most lucrative career out there; in fact, it is one of the few jobs where the average income is negative. Most ranchers lose money for their efforts, but still there seems to be no shortage of people wanting to enter the profession.

Other livestock businesses tend to be more profitable than beef cow–calf operations, but all too many of those also tend to run more red ink than black. Note: this is with an average level of management.

That is the bad news. Read on for the good news.

The formula to improve profitability is simple. Spend less and make more. The hard part is accomplishing that, because we usually spend money on inputs in order to increase production. The secret is to find ways to maintain productivity without having to write a check for them..

To get a handle on our expenses we need to determine what those expenses are. There are many ways to categorize and allocate expenses. The ones listed below are the same ones found on an IRS Schedule F, used for filing taxes.

Land is an expense usually paid out as rent, or through a mortgage. Even if the land is owned free and clear, there are still property taxes, and one should probably figure the opportunity cost of renting it out to someone else to determine if that is a more profitable option than operating it oneself.

Typically, we view land cost as a fixed cost. We usually cannot change the size of the total check we pay for land annually, but we can dramatically affect the cost of land per animal by increasing the number of animals our land can carry. The trick to carrying more animals on the same piece of land is to find a way to do so without increasing the amount of money spent on other categories.

The more iron, petroleum, and synthetic chemistry we place between the animals and the pasture, the less profit we usually make.

Machinery and equipment can make up the second-biggest expense, after land costs, on most operations. If you factor in purchase costs, depreciation, fuel, oil, maintenance, and repairs, it adds up rapidly.

What do you use equipment for on a pastured livestock operation? Odds are, most of that equipment is used either to make hay (or silage) or to feed hay (or silage). That would be the first place to trim costs. For most livestock operations, it is far cheaper to purchase hay than to produce it oneself.

Let’s suppose you bought an entirely new lineup of haymaking equipment: a tractor for $100,000, a swather for $50,000, a baler for $50,000, a hay rake for $20,000, and a hay trailer for $10,000 to move that hay. You’ve invested nearly a quarter million dollars into making hay, and you have not yet filled a fuel tank, bought baler twine, spent an hour in a tractor seat, or had your first mechanical breakdown.

If that machinery is amortized at 10 percent per year, that totals $25,000 a year just in depreciation. You can easily figure fuel, labor, and repairs to cost every bit as much as that depreciation. That equipment can easily cost you $50,000 a year to operate. Whether you buy used equipment or new, there are costs associated with machinery.

How much hay could you buy with that $50,000? Probably several times more than the average ranch consumes in a year. Even with $100-per-ton hay, you’d have 500 tons a year, or enough for 200 cows fed for 5 months a year. Buying that hay eliminates a lot of expense, and a lot of headaches; plus it has another, hidden benefit that we will discuss later in this book.

If a livestock operation is in financial difficulty, the first action I would recommend is to generate cash by selling unneeded machinery. These proceeds can be used to buy hay if absolutely necessary. But perhaps an even more important action is to develop a grazing system in which hay is not needed at all, because animals are grazed every day of the year.

Fertilizer is a large expense in many livestock operations. The biggest part of that expense is nitrogen fertilizer.

Prior to World War II, using nitrogen on pastures was quite uneconomical because nitrogen fertilizer was expensive, and pastures consisted largely of grass-legume mixtures. When nitrogen fertilizer became cheap after World War II, it was recommended to simply pour a lot of nitrogen on all-grass pastures. This had the effect of eliminating legumes from the pastures.

In the place of legumes (which are usually deep-taprooted plants), these nitrogen-fertilized pastures saw a huge increase in weeds such as ragweed. This deep-taprooted forb is able to reach below the grass roots to feed on leached nitrogen and tap into water once used by the legumes. This invasion of weeds led to a “need” to spray broadleaf-killing herbicides such as 2,4-D and Tordon to kill the undesirable weeds, and those chemicals in turn eliminated any surviving legumes.

It is often assumed that you “must” fertilize and spray pastures to produce forage. That is simply not true. It is not difficult to introduce legumes as a source of nitrogen to a pasture system, and to maintain them with proper grazing management (see chapter 10 for information on legumes). Unfortunately, this proper management does not currently exist on most pastures, but it is far easier (and cheaper) to change a management strategy than to continue writing checks for nitrogen fertilizer.

Other nutrients, such as phosphorus and potassium, cannot be derived from air the way nitrogen can. If they are insufficient in the soil, it may be necessary to supply them. The typical way, at least in the current era, is to apply commercial fertilizer. Alternatively, you could apply manure or compost or other carbon-based fertilizer, which is better because it supplies a wide range of nutrients along with an energy source for soil microbes.

An innovative way to import mineral nutrients (and biological energy) to your farm is to quit making your own hay and buy it instead. A ton of alfalfa hay contains about 60 pounds of nitrogen, about 12 pounds of phosphate, and about 60 pounds of potash. When you buy hay from someone else and bring it to your farm you are importing not just feed but also fertility.

The key to properly utilizing these nutrients is to feed the hay where the manure it produces will be of most benefit. You do this by feeding hay in the lowest-fertility areas of the farm, rather than in a pen or barn.

Another way to reduce your need for purchased fertilizer, oddly enough, is to maintain a tall, productive canopy of pasture plants that effectively capture all the sunlight that falls on a pasture every day the temperature is above freezing, and at the same time to ensure your pastures are colonized by mycorrhizal fungi. With both strong, constant photosynthesis and mycorrhizal colonization, there will be a flow of sugar from the plants to the mycorrhizal fungi, and from the fungi to an array of soil microbes that are capable of extracting previously unavailable nutrients from rock particles in the soil. This does not happen in overgrazed pastures with insufficient plant canopy.

In sum, a pasture that is never overgrazed and contains a diverse blend of cool- and warm-season plants, with diversity of root types and depths, will be much less subject to nutrient deficiencies than will an overgrazed monoculture. A more in-depth discussion of soil fertility is found in chapter 4.

This hay traveling down the road represents a large investment in iron and petroleum to make and move feed (and the nutrients it contains) from one location to another.

Weed control is another expense that is often unnecessary with proper management. Weeds are almost always a sign that our current mix of pasture species is not fully utilizing the water, sunlight, and soil in the pasture. If we have weeds, that means there is an ecological niche available to grow a different pasture species. If you have a deep-rooted broadleaf weed such as ragweed, it means you could instead be growing a deep-rooted palatable broadleaf forb, such as chicory.

Changing grazing management can result in most weeds being eaten by livestock, as described in chapter 7. If the weeds are being eaten, does that mean they are still weeds?

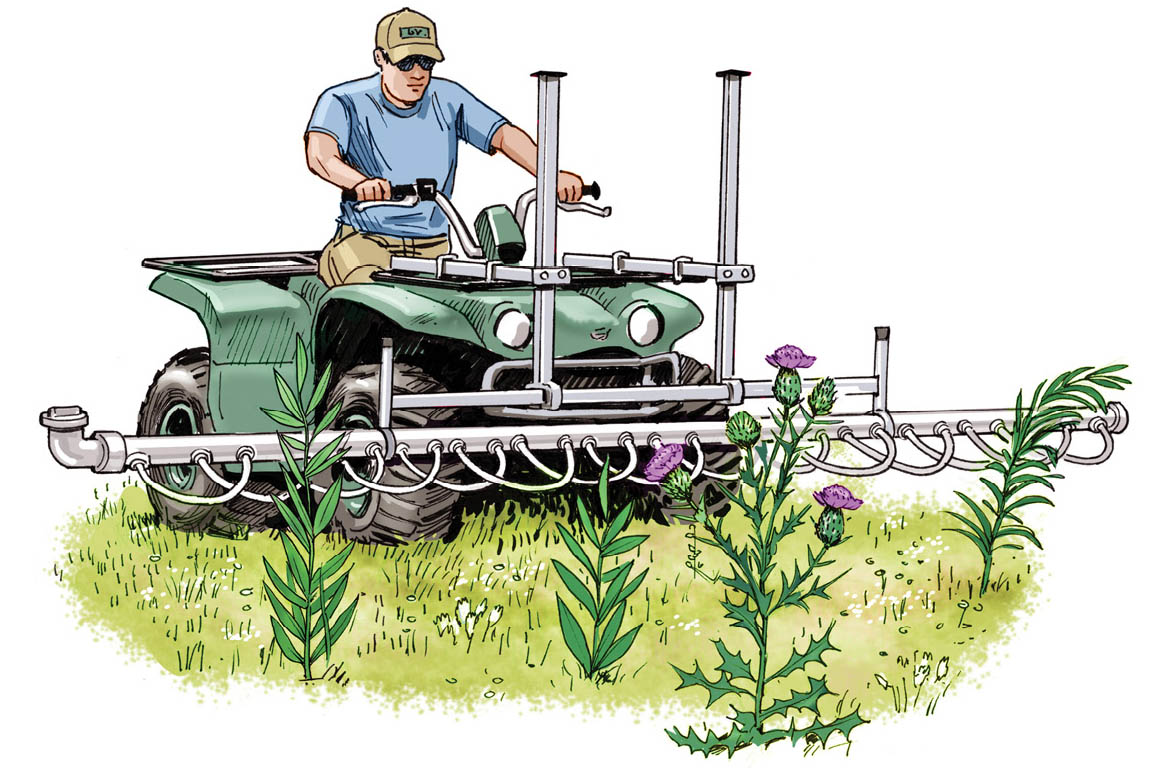

A low-cost way to control those few weeds that hang on despite more diverse pasture mixtures and grazing management is to use a weed wiper on a paddock after it has been grazed. The tractor-mounted wiper implement applies herbicide only to those plants sticking up untouched after a grazing event and keeps the chemical off the palatable plants.

Seed is a big expense on many ranches and inadequate on others. Some ranches spend a small fortune on seed of every new miracle grass that comes along and then fail to manage the grazing to realize the benefits of that plant. Most often their pastures quickly revert back to their original composition.

Allan Nation, late editor of the Stockman Grass Farmer, is often quoted as saying, “Plant nothing but fence posts the first year.” The idea behind this statement is that the very best pasture species will not show you much benefit if you do not pair them with appropriate management. You are better off to invest your dollars and time into improved grazing management before you spend money on seed.

Of course, as a guy who makes a living in the seed business, I prefer to see you make a simultaneous investment in seed and management. Once the proper grazing management is in place, it is quite possible to dramatically increase production from better species of pasture plants. A mixture of alfalfa, chicory, novel endophyte fescue, and ladino clover might produce as much as 10 times the beef per acre as a pasture of endophyte-infected fescue, and at no more cost per acre other than the initial seed investment. It must be properly grazed, however, to keep both pasture and animals healthy.

Before grazing

After grazing

Animals will graze down the edible grasses, as shown in the above illustration, leaving only the unpalatable plants. A weed wiper can eliminate the remaining weeds, using a minimum of herbicide.

Veterinary expenses can often be minimized by proper management of pasture and grazing. A blend of diverse pasture species will be more healthful than a pure grass stand of a single species.

For instance, the concentration of internal parasite larvae is highest close to manure piles, and close to the ground. Parasite larvae crawl from manure piles to the surrounding pasture plants and begin to climb, though rarely higher than 4 inches above the ground. Animals, when given a choice, graze the tops of plants, where the nutritious leaves are, and avoid the forage around manure piles. It is only under improper grazing management that animals eat plants below 4 inches in height and around recent manure piles. Internal parasite treatment should be rarely required with the grazing management we discuss in this book. Some pasture plants can reduce internal parasite burdens (see chapter 16, “Sheep and Goats,” for more information). Rotational grazing to keep young nursing animals constantly moving away from manure can greatly reduce the source of scours and other diseases.

Supplemental feed is often a way to compensate for a lack of nutrition in the base feed resource at the time. Ensuring access to green — by growing pasture with diverse species — as many days as possible will minimize the need for any purchased feeds. For example, legumes are very rich in protein and calcium, and forbs are rich in phosphorus, copper, and zinc. A pasture mix of grasses, legumes, and forbs will help guarantee adequate intake of protein and essential minerals.