Musei Capitolini

Map: Capitoline Museums Overview

This enjoyable museum complex claims to be the world’s oldest, founded in 1471 when a pope gave ancient statues to the citizens of Rome. Many of the museum’s statues have gone on to become instantly recognizable cultural icons. Perched on top of Capitoline Hill, the museum’s two buildings (Palazzo dei Conservatori and Palazzo Nuovo) are connected by an underground passage that leads to the Tabularium and panoramic views of the Roman Forum. (For more on Capitoline Hill, see here.)

(See “Capitoline Museums Overview” map, here.)

Cost: €15, €11.50 if no special exhibits.

Hours: Daily 9:30-19:30, last entry one hour before closing.

Information: You’ll find some English descriptions within the museum. Tel. 06-0608, www.museicapitolini.org.

Getting There: The museum (Musei Capitolini in Italian) sits atop Capitoline Hill (Campidoglio), housed in two buildings that flank the square. Buy tickets and enter at the Palazzo dei Conservatori (on your right as you face the equestrian statue).

Tours: The €6 videoguide is good; a €4 kids version is available.

Length of This Tour: Allow two hours.

Baggage Check: Free (mandatory for bags larger than a purse).

Cuisine Art: A great view café, called Caffè Capitolino (daily 9:30-19:00, lunch served 12:15-15:00), is upstairs in Palazzo dei Conservatori (enter from inside museum; also has exterior entrance for the public—facing museum entrance, go to your right around the building to Piazzale Caffarelli and through door #4). The pavilion on the terrace outside offers full service; the tables inside are self-service (pay first, then take receipt to bar; good salads and toasted sandwiches). Piazzale Caffarelli is a fine place for a snooze, a picnic, or just the view. (Note: While it has great views, it doesn’t overlook the Forum.)

Starring: The original she-wolf statue, Marcus Aurelius, the Dying Gaul, the Boy Extracting a Thorn, and Forum views.

Capitoline Hill’s main square (Piazza del Campidoglio), home to the museum, began as a religious center in ancient Rome, the site of temples to the gods Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. In the 16th century, Michelangelo transformed the square from pagan to papal, while adding a harmonious and refined Renaissance touch. His centerpiece was the magnificent ancient statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. (For more on the square, see here.)

On this tour, we’ll see statues and artifacts dating back to Rome’s very origins. There’s the original version of Marcus Aurelius, plus more images of this dynamic emperor and his bratty son. We’ll stand on the site of Rome’s most venerable spot, the Temple of Jupiter. And we’ll see the icon that started it all—the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus.

The museum’s layout—with two buildings connected by an underground passage—can be confusing, but this self-guided tour is easy to follow.

You’ll enter at the Palazzo dei Conservatori (on your right as you face the equestrian statue), cross underneath the square (beneath the Palazzo Senatorio, the mayoral palace, not open to public), and exit from the Palazzo Nuovo (on your left).

Expect Changes: Special exhibits (sometimes an exciting value and sometimes, it seems, just an excuse to raise the price) may cause some items to shift to different rooms. Use this chapter’s photos or ask a guard for help.

(See “Capitoline Museums Overview” map, here.)

• Begin at the square on top of Capitoline Hill. After your ticket is checked, enter the courtyard.

In the courtyard, enjoy the massive chunks of Constantine: his head, hand, feet, bicep, and other bits and pieces. When intact, this giant, 30-foot statue of the emperor sitting on his throne held the place of honor in the Basilica of Constantine in the Forum. Imagine it’s A.D. 330 as you stare up at the emperor, an abstract symbol of power. His face is otherworldly. You can’t really connect. You feel like a subject rather than a citizen. You could say the concept of monarchy by divine right starts here.

Only the extremities of the massive statue survive because a statue of this size was not entirely marble. Its core was cheaper and made of more perishable material, like bricks. Appreciate the detail of the vein in his bicep. Notice also the mortise-and-tenon joint and imagine the engineering necessary to construct this Goliath.

Also in the courtyard are reliefs of conquered peoples—not in chains, but new members of an expansive empire. These represent provinces such as Gaul, Britannia, and Thracia, and date from the reign of Hadrian (second century A.D.), whose passion was running the empire not as something to exploit but as a commonwealth.

• Go up the staircase (the one near the entrance, not the one in the courtyard). On the landing, find...

These four fine reliefs show great moments in an emperor’s daily grind. Because Rome was a visual culture and used public art for propaganda purposes, these reliefs portray typical duties a good emperor was supposed to perform: conquering, rallying the masses, and performing religious ceremonies.

Three of the four panels feature Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher who worked so valiantly to prevent Rome’s fall to the barbarians. First, find the relief where he rides in on his horse, posing like the bronze statue in Piazza del Campidoglio. Marcus stretches his hand out, offering clemency to his vanquished foes. The detail, with expressive faces and banners blowing in the wind, is impressive. Next, the emperor makes his triumphal entry into Rome on a chariot. Originally, this relief had one more figure, riding next to Marcus. It was Commodus, his wicked son (and Russell Crowe’s nemesis in Gladiator). After his assassination, Commodus’ memory was damned, so images of him were erased or chiseled out. (But, as we’ll see, his memory still lives on.) In the final relief, the good emperor greets priests about to sacrifice a bull in thanks to the gods (with even the bull looking on curiously).

• Continue up the stairs to the first floor. Go through two large frescoed rooms (Rooms 4 and 5) and continue directly ahead through a doorway to find Room 8, with the...

He’s just a boy, intent only on picking a thorn out of his foot. As he bends over to reach his foot, his body sticks out at all angles, like a bony chicken wing. He’s even scuffed up, the way small boys get. At this moment, nothing matters to him but that splinter. Our lives are filled with these mundane moments (when we’d give anything for tweezers), which are rarely captured in art.

The boy is a bronze cast with eyes once inlaid as in the adjacent bronze cast of Brutus. Take a close look at Brutus (whose descendent took part in the killing of Caesar). This wonderful bust typifies Roman character: determined, thoughtful, no-nonsense, and capable. The ivory eyes are original.

Now, look up, and appreciate the fresco that has lined this room since it was part of a municipal palace in the 16th century. It’s a stirring battle scene that celebrates the power and glory of ancient Rome. Find the wagonload of enemy armor and weapons and sweep 360 degrees as if joining in this triumphal parade. It’s another great military victory, and the troops are bringing home precious statues of bronze and marble as plunder. There’s the emperor on his four-horse chariot. The enemy prisoners are bound and ready to absorb your disdain. And after the sacrificial bulls is a chorus of trumpets and throngs of your fellow adoring citizens—all thankful to be loyal subjects of the emperor.

• In the next room (Room 9) is the...

The original bronze she-wolf suckles the twins Romulus and Remus. This symbol of Rome is ancient, though the wolf statue itself (long thought to be Etruscan, from the fifth century B.C.) was made in the 13th century, and the boys are an invention of the 15th century. Look into the eyes of the wolf. An animal looks back, with ragged ears, sharp teeth, and staring eyes. This wild animal, teamed with the wildest creatures of all—hungry babies—makes a powerful symbol for the tenacious city/empire of Rome.

• Continue on to Room 10.

Along with a bust of Michelangelo made from his death mask, this room contains Bernini’s anguished bust of Medusa—with writhing snakes on her head. This goes way beyond a bad hair day. Enjoy the artistry of Bernini as he fashions a marble lock of hair into a writhing snake.

Then appreciate the room you’re in as a piece of art in itself: Murano glass chandelier, fine painted coffered ceiling, fabric walls, inlaid marble floor, medallions celebrating papal donations to the collection, and frescoed panels set in fanciful grotesque-style decor. As a bonus, you’ve got Rome, including St. Peter’s dome, out the window.

• Pass through three small rooms: Room 12 has the Artemis of Efenina (Ephesus), with her extremely fertile draping of numerous bull testicles, breasts, or perhaps puka shells (no one knows for sure). Room 13 features Greek red-figured vases (and the elevator up to the second-floor café—need a coffee break?). Room 14 has a fourth-century chariot and an incredibly lifelike bronze horse. Continue ahead up a set of seven stairs and follow them to the next room to discover the remarkable bust of...

This arrogant emperor brat used to run around the palace in animal skins pretending (or believing) he was Hercules. Here, he wears a lion’s head over his own and drapes the lion’s paws over his chest. This lion king made a bad emperor (ruled A.D. 180-192). Commodus earned a reputation as a good athlete and warrior, and a rough character. He hung out with low-class gladiators, and even fought in the arena himself. The fights were staged—no one was allowed to hurt the emperor—which meant that Commodus killed innocent people, some of them beaten to death with his beloved Hercules club. The people hated Commodus. Commodus-the-jock was also at odds with his father, the previous emperor and noted scholar and philosopher, Marcus Aurelius.

This statue dates from the late second century, a period of debauchery and decline. The emperor is self-indulgent. The gravitas is gone, and soon the empire will follow. Examine the statue’s details—the perfect curls of hair and beard, sheen of the skin, and manicured nails. Notice also the symbols of astrology, fertility, and abundance. While Commodus’ memory was damned (remember how he was chiseled out of the panel downstairs), somehow this masterpiece survived.

• As you are looking at Commodus, directly behind you is his dad, the Emperor...

This is the greatest surviving equestrian statue of antiquity. Marcus Aurelius was a Roman philosopher-emperor (ruled A.D. 161-180) known more for his Meditations than his prowess on the battlefield. His gesture is of clemency, pardoning defeated enemies. The patina of time almost drips off him. While he has the same fine hair and features of his son Commodus (see earlier), the emperor is still working for the glory of Rome rather than for the glory of himself.

Christians in the Dark Ages thought that the statue’s hand was raised in blessing, which probably led to their misidentifying him as Constantine, the first Christian emperor. While most pagan statues were destroyed by Christians, “Constantine” was spared. It graced several prominent locations in medieval Rome, including the papal palace at San Giovanni in Laterano.

In 1538, this gilded bronze statue was placed in the center of the Campidoglio (directly outside the museum), and Michelangelo was hired to design the buildings around it with the statue as the centerpiece. A few years ago, the statue was moved inside and restored, while the copy you see outside today was placed on the square. (Notice that Aurelius doesn’t use stirrups—an Asian invention, those newfangled devices wouldn’t arrive in Europe for another 500 years.)

Also in the room are more hunks—head, hand, and a globe—of another statue of Constantine. (Or was it the Emperor Sylvestrus Stalloneus?)

• Descend the ramp to the wall of blocks from the...

This is part of the foundation of the ancient Temple of Jupiter (Giove), once the most impressive in Rome. It was located right near where you’re standing. Find the scale model of the temple (1:40) to get a sense of its size and where you stand in relation to the ruins. Imagine you’re standing before a wall that has stood here, crowning the capital hill of Rome, for more than 2,500 years. It is in situ; this part of the museum is built around this wall.

The King of the Gods resided atop Capitoline Hill in this once-classy 10,000-square-foot temple, which was perched on a podium and lined with Greek-style columns, overlooking downtown Rome. The most important rites were performed here, and victory parades through the Forum ended here. Replicas of this building were erected in every Roman city. The temple was begun by Rome’s last king (the Tarquin), and its dedication in 509 B.C. marks the start of the Roman Republic.

All that remains of the temple today are these ruined foundation stones, made of volcanic tuff, an easily carved rock commonly used in Roman construction. Although there are hundreds of these blocks here, they represent only a portion of the immense foundation, which is only a fraction of the temple itself. In its prime, the temple rose two stories above our heads. Inside stood a statue of the god of thunder wielding a lightning bolt. The temple was refurbished a number of times over the centuries, often after damage by...lightning bolts.

• By the way, a good WC is behind the wall. And this is your last chance to (easily) reach that café.

Here’s how to get to the next stop, the Tabularium: With your back to the old wall, find seven stairs (to the right of the ramp). Go up the steps and then straight to the end of the hall. Exiting the hall, make a U-turn right and go down the stairs you climbed earlier, all the way to the basement—the piano sotteraneo. Then cross underneath the square through the long passageway filled with ancient inscriptions (well described in English). Near the far end, turn right and climb a set of stairs into the...

Built in the first century B.C., these sturdy vacant rooms once held the archives of ancient Rome. The word Tabularium comes from “tablet,” on which Romans wrote their laws.

The rooms offer a stunning head-on view over the Forum, giving you a more complete picture of the sprawl of ancient Rome. Belly up to the overlook. Panning left to right, find the following landmarks: Arch of Septimius Severus, Arch of Titus (in the distance), the lone Column of Phocas, the three columns of the Temple of Castor and Pollux, the eight columns of the Temple of Saturn (closer to you), and the three columns (closest to you) of the Temple of Vespasiano.

Now do an about-face and look up to see a huge white hunk of carved marble, an overhang from the Temple of Vespasiano. Wander around. Appreciate the towering vaulted ceiling and ancient Roman engineering. While some say Rome was built of marble, that’s not quite true. The Romans baked thin bricks and also invented concrete. They built their big buildings mostly out of brick and concrete and then covered them with marble veneer.

• Leave the Tabularium by going back down the stairs you just climbed. Turn right (passing a low-key WC), and go up three flights of stairs. You’re now on the first floor (primo piano) of the...

• From the top of the stairs, continue directly into Room 66—the “Hall of the Gaul”—with one of the museum’s most famous pieces.

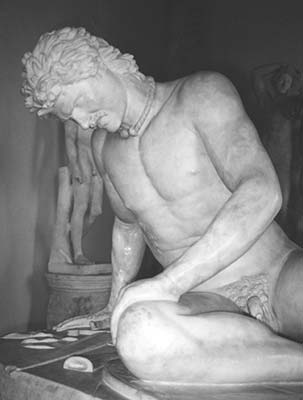

A first-century B.C. copy of a Greek original, this was sculpted to celebrate the Greeks’ victory over the Galatians. Wounded in battle, the dying Gaul holds himself upright, but barely. Minutes earlier, before he was stabbed in the chest, he’d been in his prime. Now he can only watch helplessly as his life ebbs away. His sword is useless against this last battle. With his messy hair, downcast eyes, and crumpled position, he poignantly reminds us that every victory also means a defeat.

• The next few rooms are filled with interesting art. As you wander, take a quick look at...

In the first room (#65), a faun—carved out of red marble—glories in grapes and life, oblivious to the loss of his penis (at least he still has his tail). The statue, found among a couple of dozen pieces in Hadrian’s Villa, was skillfully restored. Check out the chandeliered ceilings in this room and elsewhere; this building is truly a palazzo (palace).

Next, the Great Hall (Room 64) features more sculpture from Hadrian’s Villa (and elsewhere). Notice the Wounded Amazon, near the window, with her one breast uncovered in typical Amazon fashion, so that the fabric wouldn’t be in the way of her archery. Standing in a classic contrapposto pose (weight on one leg), this is a Roman copy of a fifth-century B.C. Greek original by Polycletus.

Roll through two rooms lined with busts. The Hall of Philosophers (Room 63) celebrates Socrates, Homer, Euripides, Cicero, and many more. The Hall of Emperors (Room 62) welcomes you with Constantine’s mom Helena sitting center stage, resting after her journey to Jerusalem to find Christ’s cross. In this 3-D yearbook of ancient history, find the purple-chested bust of Caracalla. Infamous for his fervent brutality, he instructed his portraitists to stress his meanness. They did it well. Directly across on the lower shelf, the smallest bust—of Emperor Gordiano (ruled A.D. 238-244)—is one of the finest of late antiquity. His expression shows the concern and consternation of a ruler whose empire is in decline. In this room you can find classic expressions of confidence, brutality, and anguish—human drama through the ages. Before leaving, sample the delicate elegance of ancient Roman hairstyles for women.

• Enter the hallway, turn right, and start down the hall. The small octagonal room on your left contains one of the museum’s treasures.

This is a Roman copy of a fourth-century B.C. Greek original by the master Praxiteles. Venus, leaving the bath, is suddenly aware that someone is watching her. As she turns to look, she reflexively covers up (nearly). Her blank eyes hold no personality or emotion. Her fancy hairstyle is the only complicated thing about her. She is simply beautiful—generically erotic.

• Head to the last room on the left before the stairs (Room 60). Among the many busts in the room, find the...

Four doves perch on the rim of a bronze bowl as one drinks water from the bowl. Minute bits make up this small, exquisite work. Found in the center of a floor in one of the rooms in Hadrian’s Villa, this second-century A.D. mosaic was based on an earlier work done, of course, by the Greeks.

We all know that ancient Rome was grand. But the art in this museum tells us that its culture was refined as well. Before leaving, walk slowly around this last room, looking into the eyes of the characters who were the real foundation of ancient Rome.

• To exit, head down the stairs to the ground floor, and follow signs to the uscita. Take a photo with the colossal river-god statue of Marforio. If you checked a bag, cross the courtyard to retrieve it.