▲▲▲Roman Forum (Foro Romano) and ▲▲Palatine Hill (Monte Palatino)

▲Mamertine Prison (Carcere Mamertino)

Map: Capitoline Hill & Piazza Venezia

▲▲▲Capitoline Museums (Musei Capitolini)

Santa Maria in Aracoeli Church

Synagogue (Sinagoga) and Jewish Museum (Museo Ebraico)

▲Museum of the Imperial Forums (Museo dei Fori Imperiali)

▲The Roman House at Palazzo Valentini (Le Domus Romane di Palazzo Valentini)

▲St. Peter-in-Chains Church (San Pietro in Vincoli)

▲▲▲Pantheon

Piazza di Pietra (Piazza of Stone)

▲▲▲St. Peter’s Basilica (Basilica San Pietro)

▲▲▲Vatican Museums (Musei Vaticani)

▲▲▲Borghese Gallery (Galleria Borghese)

Etruscan Museum (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia)

Capuchin Crypt (Cripta dei Frati Cappuccini)

Church of Santa Maria del Popolo

▲▲Museo dell’Ara Pacis (Museum of the Altar of Peace)

▲▲Catacombs of Priscilla (Catacombe di Priscilla)

▲▲▲National Museum of Rome (Museo Nazionale Romano Palazzo Massimo alle Terme)

▲Baths of Diocletian/Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli (Terme di Diocleziano/Basilica S. Maria degli Angeli)

▲Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria

Baroque Surprises Stroll on Via XX Settembre

▲▲Church of San Giovanni in Laterano

Museum of the Liberation of Rome (Museo Storico della Liberazione)

▲Church of Santa Maria Maggiore

▲Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere

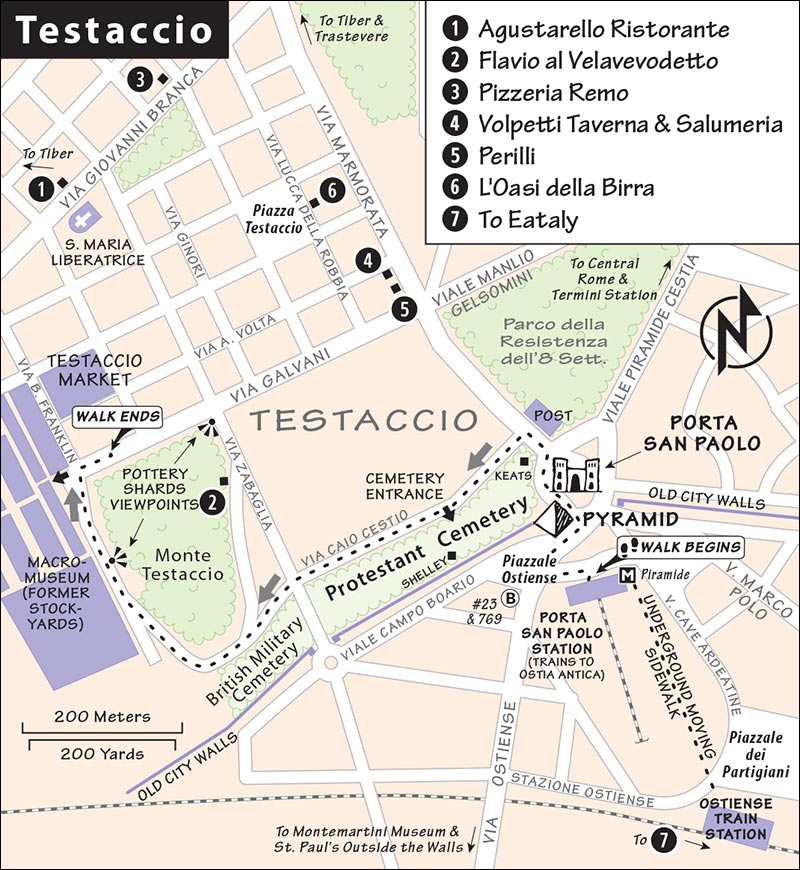

Porta San Paolo and Museo della Via Ostiense

Testaccio Market (Mercato di Testaccio)

▲Montemartini Museum (Musei Capitolini Centrale Montemartini)

▲St. Paul’s Outside the Walls (Basilica San Paolo Fuori le Mura)

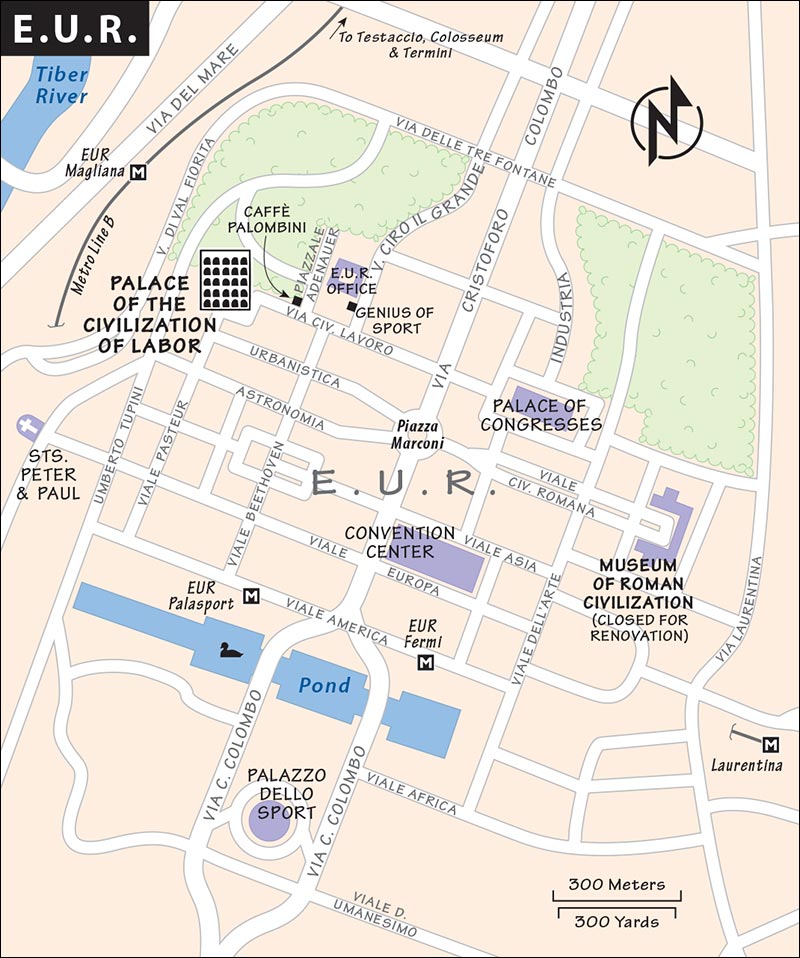

Palace of the Civilization of Labor (Palazzo della Civiltà del Lavoro)

Fascist Art, Architecture, and Propaganda

Museum of Roman Civilization (Museo della Civiltà Romana)

ANCIENT APPIAN WAY AND SOUTHEASTERN ROME

Baths of Caracalla (Terme di Caracalla)

I’ve clustered Rome’s sights into walkable neighborhoods, some quite close together (see map on here). Save transit time by grouping your sightseeing according to location. For example, in one great day you can start at the Colosseum, then go to the Forum, then Capitoline Hill, and from there either to the Pantheon or back to the Colosseum (by way of additional ruins along Via dei Fori Imperiali).

When you see a  in a listing, it means the sight is described in greater detail in one of my self-guided walks or tours. A

in a listing, it means the sight is described in greater detail in one of my self-guided walks or tours. A  means the walk or tour is also available as a free audio tour (via my Rick Steves Audio Europe app—see here). Some walks and tours are available in both formats—take your pick. This is why some of Rome’s most important sights get the least coverage in this chapter—we’ll explore them in greater depth elsewhere in this book.

means the walk or tour is also available as a free audio tour (via my Rick Steves Audio Europe app—see here). Some walks and tours are available in both formats—take your pick. This is why some of Rome’s most important sights get the least coverage in this chapter—we’ll explore them in greater depth elsewhere in this book.

For general tips on sightseeing, see here. Rome’s good city-run information website, www.060608.it, lists current opening hours.

To connect some of the most central sights, follow my Heart of Rome Walk (see the next chapter), which takes you from Campo de’ Fiori to the Trevi Fountain and Spanish Steps. This walk is most enjoyable in the evening—after the museums have closed, when the evening air and lit-up fountains show off Rome at its most magical. To join the parade of people strolling down Via del Corso every evening, take my Dolce Vita Stroll (see here).

Price Hike Alert: Many of Rome’s sights host a special exhibit and require you to pay extra for your ticket, even if all you want to see is the permanent collection. This means admission fees jump by €3 or more. Expect this practice at the Capitoline Museums, Borghese Gallery, National Museum of Rome, Ara Pacis, and others. Come expecting this higher price...and consider yourself lucky if you happen to get in for less. If you must pay the higher price, take advantage of the chance to add these top-quality special offerings to your basic sightseeing.

Free First Sundays: The state museums in Italy are free to all on the first Sunday of each month (no reservations are available). That means the Colosseum, Roman Forum, Palatine Hill, Borghese Gallery, National Museum of Rome, Castel Sant’Angelo, Etruscan Museum, and Baths of Caracalla are free—and packed. It’s actually bad news; I’d make a point to avoid the Colosseum and Roman Forum on that day.

The core of ancient Rome, where the grandest monuments were built, is between the Colosseum and Capitoline Hill. Among the ancient forums, a few modern sights have popped up. I’ve listed these sights from south to north, starting with the biggies—the Colosseum and Forum—and continuing up to Capitoline Hill and Piazza Venezia. Between the Capitoline and the river is the former Jewish Ghetto. As a pleasant conclusion to your busy day, consider my relaxing self-guided walk back south along the broad, parklike main drag—Via dei Fori Imperiali—with some enticing detours to nearby sights.

This 2,000-year-old building is the classic example of Roman engineering. Used as a venue for entertaining the masses, this colossal, functional stadium is one of Europe’s most recognizable landmarks. Whether you’re playing gladiator or simply marveling at the remarkable ancient design and construction, the Colosseum gets a unanimous thumbs-up.

Cost and Hours: €12 combo-ticket includes Roman Forum and Palatine Hill (see here), free and very crowded first Sun of the month, open daily 8:30 until one hour before sunset (see here for times), last entry one hour before closing, audioguide-€5.50, Metro: Colosseo, tel. 06-3996-7700, www.archeoroma.beniculturali.it/en. For line-avoiding tips, see here.

See the Colosseum Tour chapter or

See the Colosseum Tour chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

This well-preserved arch, which stands between the Colosseum and the Forum, commemorates a military coup and, more important, the acceptance of Christianity by the Roman Empire. When the ambitious Emperor Constantine (who had a vision that he’d win under the sign of the cross) defeated his rival Maxentius in A.D. 312, Constantine became sole emperor of the Roman Empire and legalized Christianity. The arch is free to see—always open and viewable.

The Arch of Constantine is covered in more detail on here of my  Colosseum Tour chapter, and

Colosseum Tour chapter, and  in my free audio tour.

in my free audio tour.

Though I’ve covered them with separate tours, the Forum and Palatine Hill are organized as a single sight with one admission (ticket also includes Colosseum). You’ll need to see both sights in a single visit (see here for details).

Cost and Hours: €12 combo-ticket includes Colosseum—see here, free and very crowded first Sun of the month, open same hours as Colosseum, audioguide-€5, Metro: Colosseo, tel. 06-3996-7700, www.archeoroma.beniculturali.it/en.

Roman Forum (Foro Romano): This is ancient Rome’s birthplace and civic center, and the common ground between Rome’s famous seven hills. As just about anything important that happened in ancient Rome happened here, it’s arguably the most important piece of real estate in Western civilization. While only a few fragments of that glorious past remain, history seekers find plenty to ignite their imaginations amid the half-broken columns and arches.

See the Roman Forum Tour chapter or

See the Roman Forum Tour chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

Palatine Hill (Monte Palatino): The hill overlooking the Forum was the home of the emperors and now contains a museum, scant (but impressive when understood) remains of imperial palaces, and a view of the Circus Maximus (if it’s not blocked by ongoing archaeological work).

See the Palatine Hill Tour chapter.

See the Palatine Hill Tour chapter.

This 2,500-year-old cistern-like prison on Capitoline Hill is where, according to Christian tradition, the Romans imprisoned Saints Peter and Paul (it’s also known as Carcere di San Pietro). Today it’s a small but impressive archeological site using the latest technology to illustrate what you might unearth when digging in Rome: a pagan sacred site, an ancient Roman prison, an early Christian pilgrimage destination, or a medieval church. After learning the context using the included videoguide, and browsing artifacts (including the skeletons of those executed with their hands still tied behind their backs), you can walk to the bottom of this dank cistern under an original Roman stone roof—marvel at its engineering. Amid fat rats and rotting corpses, unfortunate prisoners of the emperor awaited slow deaths here. It’s said that a miraculous fountain sprang up inside so Peter could convert and baptize his jailers, who were also subsequently martyred. Run by the Vatican, this pricey sight is a good value for pilgrims and antiquities wonks.

Cost and Hours: €10, includes videoguide, €20 combo-ticket includes Colosseum and Roman Forum, same hours as Colosseum, Clivo Argentario 1, tel. 06-698-961, www.operaromanapellegrinaggi.org.

The legendary “Mouth of Truth” at the Church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin—a few blocks southwest of the other sights listed here—can be crowded, with lots of mindless “selfie-stick” travelers. Stick your hand in the mouth of the gaping stone face in the porch wall. As the legend goes (and was popularized by the 1953 film Roman Holiday, starring Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn), if you’re a liar, your hand will be gobbled up. The mouth is only accessible when the church gate is open, but it’s always (partially) visible through the gate, even when closed. If the church itself is open, step inside to see one of the few unaltered medieval church interiors in Rome. Notice the mismatched ancient columns and beautiful cosmatesque floor—a centuries-old example of recycling.

Cost and Hours: €0.50 suggested donation, daily 9:30-17:50, shorter hours off-season, Piazza Bocca della Verità 18, near the north end of Circus Maximus, a 10-minute walk south from Piazza Venezia, bus #81 from Vatican area or #170 from Termini/Via Nazionale, tel. 06-678-7759.

Of Rome’s famous seven hills, this is the smallest, tallest, and most famous—home of the ancient Temple of Jupiter and the center of city government for 2,500 years. There are several ways to get to the top of Capitoline Hill. If you’re coming from the north (from Piazza Venezia), take Michelangelo’s impressive stairway to the right of the big, white Victor Emmanuel Monument. Coming from the southeast (the Forum), take the steep staircase near the Arch of Septimius Severus. From near Trajan’s Forum along Via dei Fori Imperiali, take the winding road. All three converge at the top, in the square called Campidoglio (kahm-pee-DOHL-yoh).

This square atop the hill, once the religious and political center of ancient Rome, is still the home of the city’s government. In the 1530s, the pope called on Michelangelo to reestablish this square as a grand center. Michelangelo placed the ancient equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius as its focal point—very effective. (The original statue is now in the adjacent museum.) The twin buildings on either side are the Capitoline Museums. Behind the replica of the statue is the mayoral palace (Palazzo Senatorio).

Michelangelo intended that people approach the square from his grand stairway off Piazza Venezia. From the top of the stairway, you see the new Renaissance face of Rome, with its back to the Forum. Michelangelo gave the buildings the “giant order”—huge pilasters make the existing two-story buildings feel one-storied and more harmonious with the new square. Notice how the statues atop these buildings welcome you and then draw you in.

The terraces just downhill (past either side of the mayor’s palace) offer grand views of the Forum. To the left of the mayor’s palace is a copy of the famous she-wolf statue on a column. Farther down is il nasone (“the big nose”), a refreshing water fountain (see photo). Block the spout with your fingers, and water spurts up for drinking. Romans joke that a cheap Roman boy takes his date out for a drink at il nasone.

Some of ancient Rome’s most famous statues and art are housed in the two palaces that flank the equestrian statue in the Campidoglio. You’ll see the Dying Gaul, the original she-wolf, and the original version of the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. Admission includes access to the underground Tabularium, with its panoramic overlook of the Forum.

Cost and Hours: €15, €11.50 if no special exhibits, daily 9:30-19:30, last entry one hour before closing, videoguide-€6, good children’s audioguide-€4, tel. 06-0608, www.museicapitolini.org.

See the Capitoline Museums Tour chapter.

See the Capitoline Museums Tour chapter.

The church atop Capitoline Hill is old and dear to the hearts of Romans. It stands on the site where Emperor Augustus (supposedly) had a premonition of the coming of Mary and Christ standing on an “altar in the sky” (ara coeli).

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 9:00-18:30, Oct-April 9:30-17:30, tel. 06-6976-3839.

Visiting the Church: Climb up the long, steep staircase from street level (the right side of Victor Emmanuel Monument as you face it).

The church is Rome in a nutshell, where you can time-travel across 2,000 years by standing in one spot. The building dates from Byzantine times (sixth century) and was expanded in the 1200s. Inside, the mismatched columns (red, yellow, striped, fluted) and marble floor are ancient, plundered from many different monuments. The medieval world is evident in the gravestones beneath your feet. The early Renaissance is featured in beautiful frescoes by Pinturicchio (first chapel on the right from the main entrance), with their 3-D perspective and natural landscapes. The coffered ceiling celebrates the Christian victory over the Ottoman Turks (Battle of Lepanto, 1571), with thanks to Mary (in the center of the ceiling). The chandeliers in the nave hint at the elegance of Baroque. Napoleon’s occupying troops used the building as a horse stable. But like Rome itself, it survived and retained its splendor.

The church comes alive at Christmastime. Romans hike up to enjoy a manger scene (presepio) assembled every year in the second chapel on the left. They stop at the many images of the Virgin (e.g., the statue in the marble gazebo to the left of the altar), who made an appearance to the pagan Augustus so long ago. And, most famously, they venerate a wooden statue of the Baby Jesus (Santo Bambino), displayed in a chapel to the left of the altar (go through the low-profile door and down the hall). Though the original statue was stolen in 1994, the copy continues this longtime Roman tradition. A clear box filled with handwritten prayers sits nearby.

The daunting 125-step staircase up Capitoline Hill to the entrance was once climbed—on their knees—by Roman women who wished for a child. Today, they don’t...and Italy has Europe’s lowest birthrate.

From the 16th through the 19th century, Rome’s Jewish population was forced to live in a cramped ghetto at an often-flooded bend of the Tiber River. While the medieval Jewish ghetto is long gone, this area—between Capitoline Hill and the Campo de’ Fiori—is still home to Rome’s synagogue and fragments of its Jewish heritage.

See the Jewish Ghetto Walk chapter or

See the Jewish Ghetto Walk chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

Rome’s modern synagogue stands proudly on the spot where the medieval Jewish community was sequestered for more than 300 years. The site of a historic visit by Pope John Paul II, this synagogue features a fine interior and a museum filled with artifacts of Rome’s Jewish community. The only way to visit the synagogue—unless you’re here for daily prayer service—is with a tour.

Cost and Hours: €11 ticket covers both, includes museum audioguide, and guided tour of synagogue; Sun-Thu 10:00-18:00, Fri until 16:00; shorter hours Oct-March, closed Sat year-round; last entry 45 minutes before closing, English tours usually at :15 past the hour, 30 minutes, confirm at ticket counter, modest dress required, on Lungotevere dei Cenci, tel. 06-6840-0661, www.museoebraico.roma.it. Walking tours of the ghetto are conducted at least once a day except Saturday.

This vast square, dominated by the big, white Victor Emmanuel Monument, is a major transportation hub and the focal point of modern Rome. With your back to the monument (you’ll get the best views from the terrace by the guards and eternal flame), look down Via del Corso, the city’s axis, surrounded by Rome’s classiest shopping district. In the 1930s, Benito Mussolini whipped up Italy’s nationalistic fervor from a balcony above the square (it’s the less-grand building on the left). He gave 64 speeches from this balcony, including the declaration of war in 1940. This Early Renaissance building (with hints of medieval showing with its crenellated roof line) was the seat of Mussolini’s fascist government. Fascist masses filled the square screaming, “Four more years!”—or something like that. Mussolini created the boulevard Via dei Fori Imperiali (to your right, capped by Trajan’s Column) to open up views of the Colosseum in the distance. Mussolini lied to his people, mixing fear and patriotism to push his country to the right and embroil the Italians in expensive and regrettable wars. In 1945, they shot Mussolini and hung him from a meat hook in Milan.

With your back still to the monument, circle around the left side. At the back end of the monument, look down into the ditch on your left to see the ruins of an ancient apartment building from the first century A.D.; part of it was transformed into a tiny church (faded frescoes and bell tower). Rome was built in layers—almost everywhere you go, there’s an earlier version beneath your feet.

Continuing on, you reach two staircases leading up Capitoline Hill. One is Michelangelo’s grand staircase up to the Campidoglio. The steeper of the two leads to Santa Maria in Aracoeli, a good example of the earliest style of Christian church (described earlier). The contrast between this climb-on-your-knees ramp to God’s house and Michelangelo’s elegant stairs illustrates the changes Renaissance humanism brought civilization.

From the bottom of Michelangelo’s stairs, look right several blocks down the street to see a condominium actually built upon the surviving ancient pillars and arches of Teatro di Marcello.

This oversized monument to Italy’s first king, built to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the country’s unification in 1861, was part of Italy’s push to overcome the new country’s strong regionalism and create a national identity. Today, the monument houses museums, a café with a view, and a €7 elevator to an even better view. See the map on here.

The scale of the monument is over-the-top: 200 feet high, 500 feet wide. The 43-foot-long statue of the king on his high horse is one of the biggest equestrian statues in the world. The king’s moustache forms an arc five feet long, and a person could sit within the horse’s hoof. At the base of this statue, Italy’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (flanked by Italian flags and armed guards) is watched over by the goddess Roma (with the gold mosaic background).

Cost and Hours: Monument—free, daily 9:30-18:30, a few WCs scattered throughout, tel. 06-871-5111; Rome from the Sky elevator—€7, daily until 19:30; ticket office closes 45 minutes earlier, tel. 06-0608; follow ascensori panoramici signs inside the Victor Emmanuel Monument (no elevator access from street level).

Background: With its gleaming white sheen (from a recent scrubbing) and enormous scale, the monument provides a vivid sense of what Ancient Rome looked like at its peak—imagine the Forum filled with shiny, grandiose buildings like this one. It’s also lathered in symbolism meant to connect the modern city and nation with its grand past: The eternal flames are reminiscent of the Vestal Virgins and the ancient flame of Rome. And it’s crowned by glorious chariots like those that topped the ancient Arch of Constantine.

Locals have a love/hate relationship with this “Altar of the Nation.” Many Romans say it’s a “punch in the eye” and regret its unfortunate, clumsy location atop precious antiquities. Others consider it a reminder of the challenge that followed the creation of the modern nation of Italy: actually creating “Italians.”

Visiting the Monument: The “Vittoriano” (as locals call it) is free to the public. You can simply climb the front stairs, or go inside from one of several entrances: midway up the monument through doorways flanking the central statue, on either side at street level, and at the base of the colonnade (two-thirds of the way up). Deeper into the monument, the little-visited Museum of the Risorgimento fills several floors with displays (well-described in English) on the movement and war that led to the unification of Italy (€5, tel. 06-679-3598, www.risorgimento.it). A section on the lower east side hosts temporary exhibits of minor works by major artists (€14, includes audioguide, tel. 06-678-0664, www.ilvittorianorisorgimento.com). A café is at the base of the top colonnade, on the monument’s east side (generally open year-round).

Best of all, the monument offers a grand, free view of the Eternal City. You can climb the stairs to the midway point for a decent view, keep climbing to the base of the colonnade for a better view, or head up to the café and its terrace (at the back of the monument). For the grandest, 360-degree view—even better than from the top of St. Peter’s dome—pay to ride the Rome from the Sky (Roma dal Cielo) elevator, which zips you from the café level to the rooftop. Once on top, you stand on a terrace between the monument’s two chariots. You can look north up Via del Corso to Piazza del Popolo, west to the dome of St. Peter’s, and south to the Roman Forum and Colosseum. Helpful panoramic diagrams describe the skyline, with powerful binoculars available for zooming in on particular sights. It’s best in late afternoon, when it’s beginning to cool off and Rome glows.

(See “The Imperial Forms” map, here.)

Though the original Roman Forum is the main attraction for today’s tourists, there are several more ancient forums nearby, known collectively as “The Imperial Forums.”

As Rome grew from a village to an empire, it outgrew the Roman Forum. Several energetic emperors built their own forums complete with temples, shopping malls, government buildings, statues, monuments, and piazzas. These new imperial forums were a form of urban planning, with a cohesive design stamped with the emperor’s unique personality. Julius Caesar built the first one (46 B.C.), and over the next 150 years, it was added onto by Augustus (2 B.C.), Vespasian (A.D. 75), Nerva (A.D. 97), and Trajan (A.D. 112).

Today the ruins are out in the open, never crowded, and free to look down on from street level at any time, any day. The forums stretch in a line along Via dei Fori Imperiali, from Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum. The boulevard was built by the dictator Benito Mussolini in the 1930s—supposedly so he could look out his office window on Piazza Venezia and see the Colosseum, creating a military parade ground and a visual link between the glories of the imperial past with what he thought would be Italy’s glorious imperial future. Today, the once-noisy boulevard is a pleasant walk, since it is closed to private vehicles—and, on Sundays and holidays, to all traffic.

Self-Guided Walk: For an overview of the archaeological area, take this walk from Piazza Venezia down Via dei Fori Imperiali to the end of the Imperial Forums. After a busy day of sightseeing, this stroll offers a relaxing way to wind down (while seeing a few more ancient wonders, but without crowds or turnstiles) on your way to Via Cavour, the Monti neighborhood for lunch or dinner, or the nearby Cavour and Colosseo Metro stops.

Self-Guided Walk: For an overview of the archaeological area, take this walk from Piazza Venezia down Via dei Fori Imperiali to the end of the Imperial Forums. After a busy day of sightseeing, this stroll offers a relaxing way to wind down (while seeing a few more ancient wonders, but without crowds or turnstiles) on your way to Via Cavour, the Monti neighborhood for lunch or dinner, or the nearby Cavour and Colosseo Metro stops.

• Start at Trajan’s Column, the colossal pillar that stands alongside Piazza Venezia.

Trajan’s Column: The world’s grandest column from antiquity (rated ▲▲) anchors the first of the forums we’ll see—Trajan’s Forum. The 140-foot column is decorated with a spiral relief of 2,500 figures trumpeting the emperor’s exploits. It has stood for centuries as a symbol of a truly cosmopolitan civilization. At one point, the ashes of Trajan and his wife were held in the base, and the sun glinted off a polished bronze statue of Trajan at the top. Since the 1500s, St. Peter has been on top. (Where’s the original bronze statue of Trajan? Spaghetti pots.) Built as a stack of 17 marble doughnuts, the column is hollow (note the small window slots) with a spiral staircase inside, leading up to the balcony.

The relief unfolds like a scroll, telling the story of Rome’s last and greatest foreign conquest, Trajan’s defeat of Dacia (modern-day Romania). The staggering haul of gold plundered from the Dacians paid for this forum. The narrative starts at the bottom with a trickle of water that becomes a river and soon picks up boats full of supplies. Then come the soldiers themselves, who spill out from the gates of the city. A river god (bottom band, south side) surfaces to bless the journey. Along the way (second band), they build roads and forts to sustain the vast enterprise, including (third band, south side) Trajan’s half-mile-long bridge over the Danube, the longest for a thousand years. (Find the three tiny crisscross rectangles representing the wooden span.) Trajan himself (fourth band, in military skirt with toga over his arm) mounts a podium to fire up the troops. They hop into a Roman galley ship (fifth band) and head off to fight the valiant Dacians in the middle of a forest (eighth band). Finally, at the very top, the Romans hold a sacrifice to give thanks for the victory, while the captured armor is displayed on the pedestal.

Originally, the entire story was painted in bright colors. If you were to unwind the scroll, it would stretch over two football fields—it’s far longer than the frieze around the Parthenon in Athens.

• Now, start heading toward the Colosseum, walking along the left side of Via dei Fori Imperiali. You’re walking alongside...

Trajan’s Forum: The dozen-plus gray columns mark one of the grandest structures in Trajan’s Forum, the Basilica Ulpia, the largest law court of its day. Nearby stood two libraries that contained the world’s knowledge in Greek and Latin. (The Internet of the day, contained in two big buildings.)

Rome peaked under Emperor Trajan (ruled A.D. 98-117), when the empire stretched from England to the Sahara, from Spain to the Fertile Crescent. A triumphant Trajan returned to Rome with his booty and shook it all over the city. Most was spent on this forum, complete with temples, law courts, and the monumental column trumpeting his exploits. To build his forum, Trajan literally moved mountains. He cut away a ridge that once connected the Quirinal and Capitoline hills, creating this valley. This was the largest forum ever, and its opulence astounded even jaded Romans. Looking at this, you can only think that for every grand monument here, there was hardship and suffering in the Barbarian world.

• Most astounding of all was Trajan’s Market. That’s the big, semicircular brick structure nestled into the cutaway curve of Quirinal Hill. If you want a closer look, a pedestrian pathway leads you close to it.

Trajan’s Market: This structure was part shopping mall, part warehouse, and part administration building and/or government offices. For now the conventional wisdom holds that at ground level, the 13 tall (shallow) arches housed shops selling fresh fruit, vegetables, and flowers to people who passed by on the street. The 26 arched windows (above) lit a covered walkway lined with shops that sold wine and olive oil. On the roof (now lined with a metal railing) ran a street that likely held still more shops and offices, making about 150 in all. (The modern wooden sidewalks below are only used after dark for the nightly sound-and-light show—see here.)

By now, Rome was a booming city of more than a million people. Shoppers could browse through goods from every corner of Rome’s vast empire—exotic fruits from Africa, spices from Asia, and fish-and-chips from Londinium.

Above the semicircle, the upper floors of the complex housed bureaucrats in charge of a crucial element of city life: doling out free grain to unemployed citizens, who lived off the wealth plundered from distant lands. Better to pacify them than risk a riot. Above the offices, at the very top, rises a (leaning) tower added in the Middle Ages.

The market was beautiful and functional, filling the space of the curved hill perfectly and echoing the curved side of the Forum’s main courtyard. (The wall of rough volcanic stones on the ground once extended into a semicircle.) Unlike most Roman buildings, the brick facade wasn’t covered with plaster or marble. The architect liked the simple contrast between the warm brick and the white stone lining the arches and windows.

If you’d like to walk around the market complex and see some excavated statues, visit the Museum of the Imperial Forums (described later; enter just uphill from Trajan’s Column).

• Return to the main street, and continue toward the Colosseum for about 100 more yards.

You’re still walking alongside Trajan’s Forum. In Trajan’s day, you would have entered the forum at the Colosseum end through a triumphal arch and would have been greeted in the main square by a large statue of the soldier-king on a horse.

But none of those things remain. The ruins you see in this section are actually from the medieval era. These are the foundations of the old neighborhood that was built atop the ancient city. In modern times, that neighborhood was cleared out to build the new boulevard.

You’ll soon reach a bronze statue of Trajan himself. Though the likeness is ancient, this bronze statue is not. It was erected by the dictator Benito Mussolini when he had the modern boulevard built. Notice the date on the pedestal—Anno XI. That would be “the 11th year of the Fascist Renovation of Italy”—i.e., 1933. Imagine Mussolini strolling proudly down this historic boulevard with his fellow fascist leader, Adolf Hitler, in 1938. Anticipating the chance to host Hitler, he made sure all the props were in place enabling him to share stories of Rome’s tradition of powerful rulers.

Across the street is a similar statue of Julius Caesar. That marks the first of these imperial forums, Caesar’s Forum, built by Julius in 46 B.C. as an extension of the Roman Forum. Near Julius stand the three remaining columns of his forum’s Temple of Venus—the patron goddess of the Julian family.

• Continue along (down the left side). If the bleachers are set up for the nightly sound-and-light show, you can take a temporary seat and ponder the view.

As Trajan’s Forum narrows to an end, you reach a statue of Emperor Augustus that indicates...

The Forums of Augustus and Nerva: The statue captures Emperor Augustus in his famous hailing-a-cab pose (a copy of the original, which you can see at the Vatican Museums). This is actually his “commander talking to his people” pose. Behind him was the Forum of Augustus. Find the four white, fluted, Corinthian columns that were part of the forum’s centerpiece, the Temple of Mars. The ugly gray stone “firewall” that borders the forum’s back end was built for security. It separated fancy “downtown Rome” from the workaday world beyond (today’s characteristic and trendy Monti neighborhood) and protected Augustus’ temple from city fires that frequently broke out in poor neighborhoods made up of wooden buildings.

Farther along is a statue of Emperor Nerva, trying but failing to have the commanding presence of Augustus. (In fact, he seems to be gazing jealously across Via dei Fori Imperiali at the grandeur of the Roman Forum—the Curia and Palatine Hill.) Behind Nerva, you can get a closer look at his forum. As with Augustus’ Forum, the big stone wall (composed of volcanic tuff) on the far side was built to protect the “important” part of town from the fire-plagued working-class zone beyond.

Continuing a little farther (toward the Colosseum, above two Corinthian columns), find some fine marble reliefs from Nerva’s Forum showing women in pleated robes parading in religious rituals.

• You’ve reached the end of the Imperial Forums. You’re at the intersection of Via dei Fori Imperiali and busy Via Cavour. From here, you have a number of options.

Nearby: Here at the intersection stands an impressive crenellated tower. This was a medieval noble family’s fortified residence—a reminder that the fall of Rome left a power vacuum, and with no central authority, it was every warlord with a fortified house and a private army for himself. Behind that (and the firewall) is the colorful neighborhood of Monti (see here; it’s home to a slew of fun little eateries, see here).

Two blocks up busy Via Cavour is the Cavour Metro stop. From there, you could turn right to find St. Peter-in-Chains Church (see here).

Across Via dei Fori Imperiali is an entrance to the Roman Forum (see here); 100 yards farther down Via dei Fori Imperiali (on the left) is a tourist information center with a handy café, info desk, and WC.

• Our walk is over. Your transportation options include the Cavour and Colosseo Metro stops. Several buses stop along Via dei Fori Imperiali. And it’s easy to hail a cab from here.

Several worthwhile sights sit north of Via dei Fori Imperiali from the Roman Forum—and offer a break from the crowds.

This museum, housed in buildings from Trajan’s Market, features discoveries from the forums built by the different emperors. Although its collection of statues is not impressive compared to Rome’s other museums, it’s well displayed. And—most importantly—it allows you to walk outside, atop and amid the ruins, making this a rare opportunity to get up close to Trajan’s Market and Forum (described earlier). Focus on the big picture to mentally resurrect the fabulous forums.

Cost and Hours: €11.50 when no special exhibits, daily 9:30-19:30, last entry one hour before closing, tel. 06-0608, www.mercatiditraiano.it. Skip the museum’s slow, 1.5-hour, €6 audioguide; enter at Via IV Novembre 94 (up the staircase from Trajan’s Column).

Visiting the Museum: Start by simply admiring the main hall—three stories with marble-framed entries, fine brickwork, and high windows to allow natural light—Romans had the technology to make small panes of glass. (Cheapskates can see this much from outside the entrance without paying admission.) A caryatid (a female statue serving as a column) from the Forum of Augustus stands in the museum’s entryway, alongside a bearded mask of Giove (Jupiter, the top god). To the right, a bronze foot is all that’s left of a larger-than-life Winged Victory that adorned Augustus’ Temple of Mars the Avenger. Then explore the statues and broken columns that once decorated the forums. This main floor has fascinating reconstructions that help us imagine ancient Rome—a city of a million people with the grandiosity of the modern Victor Emmanuel Monument.

Upstairs, step outside to cross over to the other side of the hall, where you’ll find a section on Julius Caesar’s Forum, including baby Cupids (the son of Venus and Mars) carved from the pure white marble that would eventually adorn all of Rome. Your ticket includes any special exhibits, which are often hosted on this floor and generally have an ancient Rome theme.

The rest of the upstairs is dedicated to the Forum of Augustus. A model of the Temple of Mars and some large column fragments give a sense of the enormous scale. You’ll see bits and pieces of the hand of the 40-foot statue of Augustus that once stood in his forum. Take a moment to enjoy a close-up look at the practical engineering: brick-rubble arches, marble trim.

From here, you can go outside. Walkways let you descend to stroll along the curved top of Trajan’s Market. You get a sense of how inviting the market must have been in its heyday. The “market” was really a collection of streets, shops, and offices. As you walk around, you’ll also enjoy expansive views of Trajan’s Forum, his column, other forums in the distance, and the modern Victor Emmanuel Monument.

Leaving the museum, enjoy a fine view down on a 2,000-year-old street of shops.

For a quality (air-conditioned) experience, duck into this underground series of ancient spaces at the base of Trajan’s Column. The 1.5-hour tour with good English narration and evocative lighting features scant remains of an elegant ancient Roman house and bath. The highlight is a small theater where you’ll learn the entire story depicted by the 2,600 figures who parade around the 650-foot relief carved onto Trajan’s Column (€12, Wed-Mon 9:30-18:30, closed Tue, 15 people per departure, reserve English tours online or by phone, tel. 06-2276-1280, www.palazzovalentini.it).

The Imperial Forums area hosts two atmospheric and inspirational sound-and-light shows that give you a chance to fantasize about the world of the Caesars. Consider one or both of the similar and adjacent evening experiences. During each of these “nighttime journeys through ancient Rome” you spend about an hour with a headphone dialed to English, listening to an artfully crafted narration synced with projections on ancient walls, columns, and porticos. Each show is distinct, working in its own way to bring the rubble to life and take you back 2,000 years. The final effect is worth the price tag (€15, both for €25, nightly mid-April-mid-Nov—bring your warmest coat, tickets sold online and at the gate, shows can sell out on busy weekends, tel. 06-0608, www.viaggioneifori.it). If you plan to see both, do Caesar first and allow 80 minutes between starting times.

Caesar’s Forum Stroll: Starting at Trajan’s Column, this tour leads you to eight stops along a wooden sidewalk of a few hundred yards, while an hour’s narration tells the dramatic story of Julius Caesar. You’ll be on the ground level of an archaeological site that is otherwise closed to the public, giving you views you’d never see otherwise. The tour departs every 20 minutes from dark until nearly midnight.

Forum of Augustus Show: From your perch on wooden bleachers overlooking the remains of a vast forum, you’ll learn the story of Augustus through images projected on an ancient firewall that survives to provide a fine screen for modern-day spectacles. Showings are on the hour from dark until 22:00 or 23:00. Enter on Via dei Fori Imperiali just before Via Cavour (you’ll see the bleachers along the boulevard).

Tucked behind the Imperial Forums (between Trajan’s Column and the Cavour Metro stop) is a quintessentially Roman district called Monti. During the day, check out Monti’s array of funky shops and grab a quick lunch. In the evening, linger over a fine meal. Later at night, the streets froth with happy young drinkers.

One of the oldest corners of Rome, this was the original “suburb” (from “subura”—outside the sacred center). Separated from the Imperial Forums by a tall stone firewall (which stands to this day), this was the rough, fire-prone, working-class zone. And it kept that character until just a few years ago when it became trendy. Strolling around here helps visitors understand why the Romans see their hometown not as a sprawling metropolis, but as a collection of villages. Exploring back lanes, you can still find neighbors hanging out on the square and chatting, funky boutiques and fashionable shops sharing narrow streets with hole-in-the-wall hardware shops and alimentari, and wisteria-strewn cobbled lanes beckoning photographers. How this charming little bit of village Rome survived, largely undisturbed, just a few steps from some of Italy’s most trafficked sights, is a marvel. While well-discovered by now (savvy travelers have been reading about Monti in “hidden Rome” magazine and newspaper articles for years), it’s still a great place to peruse.

To explore the Monti, get to its main square, Piazza della Madonna dei Monti (three blocks west of the Cavour Metro). To get oriented, face uphill, with the big fountain to your right. That fountain is the neighborhood’s meeting point—and after hours, every square inch is thronged with young Romans socializing and drinking. They either buy bottles of wine or beer to go at the little grocery at the top of the square or at a convenience store on nearby Via Cavour.

From this hub, interesting streets branch off in every direction. The characteristic core of the district can be enjoyed by strolling one long street with three names (Via della Madonna dei Monti, which leads from the ancient firewall on the downhill side of the ancient forums, then to the central Piazza Madonna dei Monti, before continuing uphill as Via Leonina and then Via Urbana).

Monti is an ideal place for a quick lunch or early dinner, or for a memorable meal; for recommendations, see here. It’s also a fine place to shop, with funky and artistic shops lining streets such as Via del Boschetto, Via dei Serpenti, and Via Leonina (see here). Night owls will find this a good place to hang out after dark.

Built in the fifth century to house the chains that held St. Peter, this church is most famous for its Michelangelo statue of Moses, intended for the tomb of Pope Julius II (which was never built). Check out the much-venerated chains under the high altar, then focus on mighty Moses. (Note that this isn’t the famous St. Peter’s Basilica, which is in Vatican City.)

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 8:00-12:30 & 15:00-19:00, Oct-March until 18:00, modest dress required; the church is a 10-minute uphill walk from the Colosseum, or a shorter, simpler walk (but with more steps) from the Cavour Metro stop; tel. 06-9784-4950.

See the St. Peter-in-Chains Tour chapter.

See the St. Peter-in-Chains Tour chapter.

Besides being home to ancient sites and historic churches, the area around the Pantheon is another part of Rome with an urban-village feel. Wander narrow streets, sample the many shops and eateries, and gather with the locals in squares marked by bubbling fountains. Just south of the Pantheon is the Jewish quarter, with remnants of Rome’s Jewish history and culture.

Exploring this area is especially nice in the evening, when restaurants bustle and streets are jammed with foot traffic. For a self-guided walk in this neighborhood, from Campo de’ Fiori to the Trevi Fountain (and ending at the Spanish Steps),  see the Heart of Rome Walk chapter or

see the Heart of Rome Walk chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

For the greatest look at the splendor of Rome, antiquity’s best-preserved interior is a must. Built two millennia ago, this influential domed temple served as the model for Michelangelo’s dome of St. Peter’s and many others.

Cost and Hours: Free, Mon-Sat 8:30-19:30, Sun 9:00-18:00, holidays 9:00-13:00, audioguide-€6, tel. 06-6830-0230, www.pantheonroma.com.

See the Pantheon Tour chapter or

See the Pantheon Tour chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

For more on the following churches, see the latter half of my Pantheon Tour chapter. Modest dress is recommended.

The Church of San Luigi dei Francesi has a magnificent chapel painted by Caravaggio (free, daily 9:30-12:30 & 14:30-18:30 except opens Sun at 11:30, between the Pantheon and the north end of Piazza Navona, www.saintlouis-rome.net). The only Gothic church in Rome is the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, with a little-known Michelangelo statue, Christ Bearing the Cross (free, daily 6:40-19:00 except Sun from 8:00, closes midday Sat-Sun, on a little square behind the Pantheon, to the east, www.santamariasopraminerva.it). The Church of Sant’Ignazio, several blocks east of the Pantheon, is a riot of Baroque illusions with a false dome (free, Mon-Sat 7:30-19:00, Sun from 9:00, www.chiesasantignazio.it). A few blocks away, across Corso Vittorio Emanuele, is the rich and Baroque Gesù Church, headquarters of the Jesuits in Rome (free, daily 7:00-12:30 & 16:00-19:45, interesting daily ceremony at 17:30—see here for details, www.chiesadelgesu.org).

Two blocks down Corso Vittorio Emanuele from the Gesù Church, you’ll hit Largo Argentina, an excavated square about four blocks south of the Pantheon. Stroll around this square and look into the excavated pit at some of the oldest ruins in Rome. Julius Caesar was assassinated near here. At the far (west) side of the square is a cat refuge where volunteers try to find adoptive families for some 150 felines (visitors welcome daily 12:00-18:00, tel. 06-6880-5611, www.romancats.com).

This underappreciated art-filled palace lies in the heart of the old city and boasts absolutely no tourist crowds. It offers a rare chance to wander through a noble family’s lavish rooms with the prince who calls this downtown mansion home. Well, almost. Through an audioguide, the prince lovingly narrates his family’s story as you tour the palace and its world-class art.

Cost and Hours: €12, includes worthwhile 1.5-hour audioguide, daily 9:00-19:00, last entry one hour before closing, elegant café, from Piazza Venezia walk 2 blocks up Via del Corso to #305, tel. 06-679-7323, www.dopart.it/roma.

Visiting the Galleria: The story begins upstairs in the grand entrance hall (Salone del Poussin), wallpapered with French landscapes. In the adjoining throne room, you’ll see a portrait of Pope Innocent X (1574-1655), patriarch of the Pamphilj (pahm-FEEL-yee) family. His wealth and power flowed to his nephew, who built the palace—a cozy relationship that inspired the word “nepotism” (nepotem is Latin for “nephew”). The family eventually married into English nobility, which is why today’s prince speaks the Queen’s English. You’ll visit the red velvet room, the green living room, and the mirror-lined ballroom that once hosted music by resident composers Scarlatti and Handel. Along the way, the prince tells charming family secrets, like when he and his sister were scolded for roller-skating through the palace.

Past the bookshop is the painting collection. (Major works have a number to dial up audioguide information.) Don’t miss Velázquez’s intense, majestic, ultrarealistic portrait of the family founder, Innocent X. It stands alongside an equally impressive bust of the pope by the father of the Baroque art style, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Stroll through a mini-Versailles-like hall of mirrors to more paintings. In one impressive room you’ll see works by Titian, Raphael, and Caravaggio (relax along with Mary, Joseph, and Jesus, and let the angel serenade you in his Rest on the Flight to Egypt).

This square, between the Pantheon and Via del Corso, is worth walking through to admire the remains of the ancient Temple of Hadrian. One huge wall from the temple survives as the facade of a 17th-century building. The temple was dedicated to the deified emperor responsible for building the Pantheon, nearby. To help you imagine the square in A.D. 145, look for a model of the temple in a window across the square at #36. In 1696 the city incorporated the remains of the temple into the building of Rome’s central customs house. Today the building houses a meeting hall for the nearby national parliament. The holes chipped into the ancient stones could be where the marble facing (which once adorned the temple) was attached. Historians think that Dark Age scavengers dug out the metal pins the Romans used to hold the marble stones in place. Look down over the railing to see ground level—with some original paving stones—from 1,900 years ago. (The piazza is two blocks toward Via del Corso from the Pantheon.)

The bubbly Baroque fountain, worth ▲▲ by night, is a minor sight to art scholars...but a major nighttime gathering spot for teens on the make and tourists tossing coins. Those coins are collected daily to feed Rome’s poor.

See the Heart of Rome Walk chapter or

See the Heart of Rome Walk chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

(See “Vatican City & Nearby” map, here.)

Vatican City, the world’s smallest country, contains St. Peter’s Basilica (with Michelangelo’s exquisite Pietà) and the Vatican Museums (with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel). A helpful TI is just to the left of St. Peter’s Basilica as you’re facing it (Mon-Sat 8:30-18:15, closed Sun, tel. 06-6988-1662, www.vaticanstate.va). The entrances to St. Peter’s and the Vatican Museums are a 15-minute walk apart (follow the outside of the Vatican wall, which links the two sights). The nearest Metro stop—Ottaviano—still involves a 10-minute walk to either sight. For information on Vatican tours, post offices, and the pope’s schedule, see here.

Modest dress is technically required of men, women, and children throughout Vatican City, even outdoors. The policy is strictly enforced in the Sistine Chapel and at St. Peter’s Basilica, but is more relaxed elsewhere (though always at the discretion of guards). To avoid problems, cover your shoulders; bring a light jacket or cover-up if you’re wearing a tank top. Wear long pants or capris instead of shorts. Skirts or dresses should extend below your knee.

There is no doubt: This is the richest and grandest church on earth. To call it vast is like calling Einstein smart.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily April-Sept 7:00-19:00, Oct-March 7:00-18:30. The church closes on Wednesday mornings during papal audiences (until roughly 13:00). Masses occur daily throughout the day. Audioguides can be rented near the checkroom (€5 plus ID, for church only, daily 9:00-17:00). The view from the dome is worth the climb (€8 for elevator to roof, then take stairs; €6 to climb stairs all the way, cash only, allow an hour to go up and down, daily April-Sept 8:00-18:00, Oct-March 8:00-17:00, last entry one hour before closing if you take the stairs the whole way). Tel. 06-6988-3731, www.vaticanstate.va.

See the St. Peter’s Basilica Tour chapter or

See the St. Peter’s Basilica Tour chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

The four miles of displays in this immense museum complex—from ancient statues to Christian frescoes to modern paintings—culminate in the Raphael Rooms and Michelangelo’s glorious Sistine Chapel.

Cost and Hours: €16, €4 online reservation fee, Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, last entry at 16:00 (though the official closing time is 18:00, the staff starts ushering you out at 17:30), closed on religious holidays and Sun except last Sun of the month (when it’s free, more crowded, and open 9:00-14:00, last entry at 12:30); may be open Fri nights May-July and Sept-Oct 19:00-23:00 (last entry at 21:30) by online reservation only—check the website. Hours are subject to frequent change and holidays; look online for current times. Lines are extremely long in the morning—go in the late afternoon, or skip the ticket-buying line altogether by reserving an entry time on their website. A €7 audioguide is available (ID required). Tel. 06-6988-4676, http://mv.vatican.va.

See the Vatican Museums Tour chapter. You can also

See the Vatican Museums Tour chapter. You can also  download my free Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museums audio tours.

download my free Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museums audio tours.

Built as a tomb for the emperor, used through the Middle Ages as a castle, prison, and place of last refuge for popes under attack, and today a museum, this giant pile of ancient bricks is packed with history. The structure itself is striking, but the sight feels empty and underexplained—come for the building itself and the views up top, not for the exhibits or artifacts.

Cost and Hours: €10, more with special exhibits, free and crowded first Sun of the month, daily 9:00-19:30, last entry one hour before closing, near Vatican City, 10-minute walk from St. Peter’s Square at Lungotevere Castello 50, Metro: Lepanto or bus #40 or #64, tel. 06-681-9111, www.castelsantangelo.beniculturali.it.

Background: Ancient Rome allowed no tombs—not even the emperor’s—within its walls. So Emperor Hadrian grabbed the most commanding position just outside the walls and across the river and built a towering tomb (c. A.D. 139) well within view of the city. His mausoleum was a huge cylinder (210 by 70 feet) topped by a cypress grove and crowned by a huge statue of Hadrian himself riding a chariot. For nearly a hundred years, Roman emperors (from Hadrian to Caracalla, in A.D. 217) were buried here.

In the year 590, the archangel Michael appeared above the mausoleum to Pope Gregory the Great. Sheathing his sword, the angel signaled the end of a plague. The fortress that was Hadrian’s mausoleum eventually became a fortified palace, renamed for the “holy angel.”

Castel Sant’Angelo spent centuries of the Dark Ages as a fortress and prison, but was eventually connected to the Vatican via an elevated corridor at the pope’s request (1277). Since Rome was repeatedly plundered by invaders, Castel Sant’Angelo was a handy place of last refuge for threatened popes. In anticipation of long sieges, rooms were decorated with papal splendor (you’ll see paintings by Carlo Crivelli, Luca Signorelli, and Andrea Mantegna). In 1527, during a sacking of Rome by troops of Charles V of Spain, the pope lived inside the castle for months with his entourage of hundreds (an unimaginable ordeal, considering the food service at the top-floor bar).

Visiting the Castle: Touring the place is a stair-stepping workout. After you walk around the entire base of the castle—buying your ticket en route—take the small staircase down to the original Roman floor (following the route of Hadrian’s funeral procession). In the atrium, study the model of the mausoleum as it was in Roman times. Imagine being surrounded by a veneer of marble, and the niche in the wall filled with a towering “welcome to my tomb” statue of Hadrian. From here, a ramp leads to the right, spiraling 400 feet. While some of the fine original brickwork and bits of mosaic survive, the marble veneer is long gone (notice the holes in the wall from the pins that held it in place).

At the end of the ramp, turn left and go up the stairs. A bridge crosses over the room where the ashes of the emperors were kept. From here, more stairs continue out of the ancient section and into the medieval structure (built atop the mausoleum) that housed the papal apartments. Explore the rooms and enjoy the view. Then go through the Sala Paolina and up the stairs; don’t miss the Sala del Tesoro (Treasury—likely once Hadrian’s tomb, and later a prison), where the wealth of the Vatican was locked up in a huge chest. (Do miss the 58 rooms of the military museum.) From the pope’s piggy bank, a narrow flight of stairs leads to the rooftop and perhaps the finest view of Rome anywhere (pick out landmarks as you stroll around). From the safety of this dramatic vantage point, the pope surveyed the city in times of siege. Look down at the bend of the Tiber, which for 2,700 years has cradled the Eternal City.

The bridge leading to Castel Sant’Angelo was built by Hadrian for quick and regal access from downtown to his tomb. The three middle arches are actually Roman originals and a fine example of the empire’s engineering expertise. The statues of angels (each bearing a symbol of the passion of Christ—nail, sponge, shroud, and so on) are Bernini-designed and textbook Baroque. In the Middle Ages, this was the only bridge in the area that connected St. Peter’s and the Vatican with downtown Rome. Nearly all pilgrims passed this bridge to and from the church. Its shoulder-high banisters recall a tragedy: During a Jubilee Year festival in 1450, the crowd got so huge that the mob pushed out the original banisters, causing nearly 200 to fall to their deaths.

Today, as through the ages, pilgrims cross the bridge, turn left, and set their sights on the Vatican dome. Around the year 1600, they would have also set their sights on a bunch of heads hanging from the crenellations of the castle. Ponte Sant’Angelo was infamous as a place for beheadings (banditry in the countryside was rife). Locals said, “There are more heads at Castel Sant’Angelo than there are melons in the market.”

Rome’s semi-scruffy three-square-mile “Central Park” is great for its quiet shaded paths and for people-watching plenty of modern-day Romeos and Juliets. The best entrance is at the head of Via Veneto (Metro: Barberini, then 10-minute walk up Via Veneto and through the old Roman wall at Porta Pinciana, or catch a cab to Via Veneto—Porta Pinciana). There you’ll find a cluster of buildings with a café, a kiddie arcade, and bike rental (€4/hour). Rent a bike or, for romantics, a pedaled rickshaw (riscio, €12/hour). Bikes come with locks to allow you to make sightseeing stops. Follow signs to discover the park’s cafés, fountains, statues, lake, and prime picnic spots. Some sights require paid admission, including the Borghese Gallery (see Borghese Gallery Tour chapter), Rome’s zoo (see here), the National Gallery of Modern Art (which holds 19th-century art; not to be confused with MAXXI, described later), and the Etruscan Museum (described later).

You can also enter the gardens from the top of the Spanish Steps (facing the church, turn left and walk down the road 200 yards beyond Villa Medici, then angle right on the small pathway into the gardens), and from Piazza del Popolo (in the northeast corner of the piazza, stairs lead to the gardens via a terrace with grand views out to St. Peter’s Basilica—bikes and Segways can be rented nearby).

This plush museum, filling a cardinal’s mansion in the park, offers one of Europe’s most sumptuous art experiences. You’ll enjoy a collection of world-class Baroque sculpture, including Bernini’s David and his excited statue of Apollo chasing Daphne, as well as paintings by Caravaggio, Raphael, Titian, and Rubens. The museum’s mandatory reservation system keeps crowds to a manageable size.

Cost and Hours: €13, free and very crowded first Sun of the month, Tue-Sun 9:00-19:00, closed Mon. Reservations are mandatory and easy to get in English online or by phone (€2-4/person booking fee, tel. 06-32810, www.galleriaborghese.it). The further in advance you reserve, the better—a minimum of several days for a weekday visit, or at least a week ahead for weekends (less in winter). Admission times are strictly enforced (you’ll get exactly 2 hours). The 1.5-hour audioguide (€5) is excellent.

For more on reservations, as well as a self-guided tour, see the Borghese Gallery Tour chapter.

For more on reservations, as well as a self-guided tour, see the Borghese Gallery Tour chapter.

The fascinating Etruscan civilization thrived in Italy around 600 B.C., when Rome was an Etruscan town. The Villa Giulia (a once fine, now down-at-heel Renaissance palace in the Villa Borghese Gardens) hosts a museum that tells the story. The displays are clean and bright, with thorough but stilted English descriptions.

Cost and Hours: €8, free and very crowded first Sun of the month, Tue-Sun 8:30-19:30, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing, Piazzale di Villa Giulia 9, tel. 06-322-6571, www.villagiulia.beniculturali.it.

Getting There: Take tram #19 from Ottaviano or Lepanto Metro stations or tram #3 from Trastevere or Colosseum to the Museo Etrusco Villa Giulia stop, right next to the museum. You can also walk from Metro: Flaminio (15 minutes) or the Borghese Gallery (20 minutes).

Visiting the Museum: The map in Room 1 shows how the Etruscans held the area from Rome to Florence (modern-day Tuscany and Umbria) before the rise of Rome. Find the key Etruscan cities (Vulci, Tarquinia, Cerveteri) where the museum’s treasures were unearthed. Farther along, a painted, room-sized tomb from Tarquinia (Room 8, down the spiral staircase) shows how Etruscans buried their dead, along with their possessions. Stroll through room after room of cases with vases—pottery painted either red-on-black or black-on-red. The star of the museum’s sculptures is the famous “husband and wife sarcophagus” (Il Sarofago degli Sposi, Room 12)—a dead couple seeming to enjoy an everlasting banquet from atop their tomb (sixth century B.C. from Cerveteri).

Room 13b has a treasure: the Pyrgi Tablets, three gold sheets with inscriptions in both Etruscan and Phoenician. Texts like these have helped scholars decipher the Etruscan language. Sadly, most surviving Etruscan texts are gravestone epitaphs with a limited vocabulary—not very interesting reading. Etruscan isn’t related to any other known language and its origin is a mystery.

Upstairs on the mezzanine, pass through the long hall of small, mostly bronze objects (statuettes and mirrors). Continuing up to the second floor, ogle gold jewelry that belonged to sophisticated, luxury-loving Etruscans (Room 24). Near the exit, Room 40 displays a well-known terra-cotta statue, the Apollo of Veio, which stood atop Apollo’s temple. The smiling god welcomes Hercules, while his mother Latona stands nearby cradling baby Apollo.

Rome’s “National Museum of Art of the 21st Century,” billed as Italy’s “first national museum dedicated to contemporary creativity,” is a playful concrete and steel structure filled with bizarre installations. Like many contemporary art museums, it’s notable more for the building (designed by Zaha Hadid and costing €150 million) than the art inside. To me, it comes off as a second-rate Pompidou Center. While not to my taste, it’s one of the few places in the city where fans of contemporary architecture can see the latest trends. Try to visit when it’s hosting one of its events, when trendy people gather.

Since it’s away from the center, consider combining it with a walk around fellow “starchitect” Renzo Piano’s Auditorium to see how the city continues to evolve (15-minute walk to auditorium, from MAXXI follow Via Guido Reni to tram #2 stop and keep going—it’s just beyond the elevated road; see here).

Cost and Hours: €12, Tue-Sun 11:00-19:00, Sat until 22:00, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing; no permanent collection, several rotating exhibits throughout the year—preview on their website; take tram #2 (direction: Mancini) from the Flaminio Metro station to the Apollodoro tram stop, then walk west 5 minutes to Via Guido Reni 4a; to return (direction: Flaminio), the tram stop is 50 yards closer to MAXXI, tel. 06-320-1954, www.fondazionemaxxi.it.

In the 1960s, movie stars from around the world paraded down curvy Via Veneto, one of Rome’s glitziest nightspots. Today it’s still lined with the city’s poshest hotels and the US Embassy, and retains a sort of faded Champs-Elysées elegance—but any hint of local color has turned to bland.

If you want to see artistically arranged bones in Italy, this (while overpriced) is the place. The crypt is below the Church of Santa Maria della Immacolata Concezione on the tree-lined Via Veneto, just up from Piazza Barberini. The bones of about 4,000 friars who died in the 1700s are in the basement, all lined up in a series of six crypts for the delight—or disgust—of the always-wide-eyed visitor.

Cost and Hours: €8.50, €5 for kids 17 and under, daily 9:00-19:00, modest dress required, Via Veneto 27, Metro: Barberini, tel. 06-8880-3695, www.cappucciniviaveneto.it.

Visiting the Crypt: Before the crypt, a six-room museum covers the history of the Capuchins, a branch of the Franciscan order. You’ll see painting after painting of monks with brown robes and tonsure (ring-cut hair). The exhibits, featuring clothing, books, and other religious artifacts used by members of the order, are explained in English, but the only real artistic highlight is a painting of St. Francis in Meditation, once attributed to Caravaggio (but now thought to be a contemporary copy).

For most travelers, however, the main attraction remains the morbid crypt. You’ll begin with the Crypt of the Three Skeletons (#1). The ceiling is decorated with a skeleton grasping a grim-reaper scythe and scales weighing the “good deeds and the bad deeds so God can judge the soul”—illustrating the Catholic doctrine of earning salvation through good works. The clock with no hands, on the ceiling above the aisle, is a symbol: It means that life goes on forever, once led into the afterlife by Sister Death. The chapel’s bony chandelier and the stars and floral motifs made by ribs and vertebrae are particularly inspired. Finally, look down to read the macabre, monastic, thought-provoking message that serves as the moral of the story: “What you are now, we used to be; what we are now, you will be.”

In the large Crypt of the Tibia and Fibula (#2), niches are inhabited by Capuchin friars, whose robes gave the name to the brown coffee drink with the frothy white cowl. (Unlike monks, who live apart from society, the Capuchins are friars, who depend on charity and live among the people, and are part of the Franciscan order.) In this chapel we see the Franciscan symbol: the bare arm of Christ and the robed arm of a Franciscan friar embracing the faithful. Above that is a bony crown. And below, in dirt brought from Jerusalem 400 years ago, are 18 graves with simple crosses.

The Crypt of the Hips (#3) is named for the canopy of wavy hipbones with vertebrae bangles over its central altar. Between crypts #3 and #4, look up to see the jaunty skull with a shoulder-blade bowtie.

In the Crypt of the Skulls (#4), look close on the central wall to find the hourglass with wings. Yes, time on earth flies.

The next room (#5) is the boneless chapel. This is part of a church, and the monks sometimes hold somber services here.

In the last room, the Crypt of the Resurrection (#6), with a painting of Jesus bringing Lazarus back to life, sets the theme of your visit: the Christian faith in resurrection.

As you leave (humming “the foot bone’s connected to the...”), pick up a few of Rome’s most interesting postcards—the proceeds support Capuchin mission work. Head back outside, where it’s not just the bright light that provides contrast with the crypt. Within a few steps are the US Embassy, Hard Rock Café, and fancy Via Veneto cafés, filled with the poor and envious keeping an eye out for the rich and famous.

These sights are on or within a short walk of the bustling Via del Corso thoroughfare, which connects Piazza del Popolo to the heart of town. The best sight here is a walk through the neighborhood as evening falls—one of my favorite experiences in Rome.

(See “Dolce Vita Stroll” map, here.)

All over the Mediterranean world, people are out strolling in the early evening (see the sidebar on here). Rome’s passeggiata is both elegant (with chic people enjoying fancy window shopping in the grid of streets around the Spanish Steps) and a little crude (with young people on the prowl). The major sights along this walk are covered later in this section.

Romans’ favorite place for a chic evening stroll is along Via del Corso. You’ll walk from Piazza del Popolo (Metro: Flaminio) down a wonderfully traffic-free section of Via del Corso, and up Via Condotti to the Spanish Steps. Although busy at any hour, this area really attracts crowds from around 17:00 to 19:00 each evening (Fri and Sat are best), except on Sunday, when it occurs earlier in the afternoon. Leave before 18:00 if you plan to visit the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace), which closes at 19:30 (last entry at 18:30).

As you stroll, you’ll see shoppers, people watchers, and flirts on the prowl filling this neighborhood of some of Rome’s most fashionable stores (some open after siesta, roughly 16:00-19:30). The most elegance survives in the grid of streets between Via del Corso and the Spanish Steps. For a detailed description of shops in this area, see here. If you get hungry during your stroll, see here for listings of neighborhood wine bars and restaurants.

To reach Piazza del Popolo, where the stroll starts, take Metro line A to Flaminio and walk south to the square. Delightfully car-free, Piazza del Popolo is marked by an obelisk that was brought to Rome by Augustus after he conquered Egypt. (It used to stand in the Circus Maximus.) In medieval times, this area was just inside Rome’s main entry.

If starting your stroll early enough, the Baroque church of Santa Maria del Popolo is worth popping into (next to gate in old wall on north side of square). Inside, look for Raphael’s Chigi Chapel (second on left as you face the main altar) and two paintings by Caravaggio (in the Cerasi Chapel, left of altar).

From Piazza del Popolo, shop your way down Via del Corso. Though many Italians shop online or at the mall these days, this remains a fine place to feel the pulse of Rome at twilight.

Historians can side-trip right down Via Pontefici past the fascist architecture to see the massive, round-brick Mausoleum of Augustus, topped with overgrown cypress trees. This long-neglected sight, honoring Rome’s first emperor, is slated for restoration and redevelopment. Beyond it, next to the river, is Augustus’ Ara Pacis, enclosed within a protective glass-walled museum. From the mausoleum, walk down Via Tomacelli to return to Via del Corso and the 21st century.

From Via del Corso, window shoppers should take a left down Via Condotti to join the parade to the Spanish Steps, passing big-name boutiques. The streets that parallel Via Condotti to the south (Borgognona and Frattina) are also elegant and filled with high-end shops. A few streets to the north hides the narrow Via Margutta. This is where Gregory Peck’s Roman Holiday character lived (at #51); today it has a leafy tranquility and is filled with pricey artisan and antique shops.

History Buffs: Another option is to ignore Via Condotti and forget the Spanish Steps. Stay on Via del Corso, which has been straight since Roman times, and walk a half-mile down to the Victor Emmanuel Monument. Climb Michelangelo’s stairway to his glorious (especially when floodlit) square atop Capitoline Hill. Stand on the balcony (just past the mayor’s palace on the right), which overlooks the Forum. As the horizon reddens and cats prowl the unclaimed rubble of ancient Rome, it’s one of the finest views in the city.

This vast oval square marks the traditional north entrance to Rome. From ancient times until the advent of trains and airplanes, this was most visitors’ first look at Rome. Today the square, known for its symmetrical design and its art-filled churches, is the starting point for the city’s evening passeggiata (see my “Dolce Vita Stroll,” earlier).

In 1480, Pope Sixtus IV recognized that the ramshackle medieval city was making a miserable first impression on pilgrims who walked here from all over Europe (similar to the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca). He authorized city planners to appropriate property (establishing “eminent domain”), demolish old buildings, and create straight streets to accommodate traffic. This was the first of several papal campaigns to spruce up the square and make it a suitable entrance for the grand city. The German monk, Martin Luther, would have been impressed when, after walking 700 miles from Germany, he entered the city through this gate (in 1510).

Reach the square via the Flaminio Metro stop, pass through the third-century Aurelian Wall via the Porta del Popolo, and look south. The 10-story obelisk in the center of the square once graced the temple of Ramses II in Egypt and the Roman Circus Maximus racetrack. The obelisk was brought here in 1589 as one of the square’s beautification projects. (The oval shape dates from the early 19th century.) At the south side of the square, twin domed churches mark the spot where three main boulevards exit the square and form a trident. The central boulevard (running between the churches) is Via del Corso, which since ancient times has been the main north-south drag through town, running to Capitoline Hill (the governing center) and the Forum. The road to the right led to the Vatican, and the road to the left led to the big pilgrimage churches of San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Maria Maggiore. With the help of this tridente, pilgrims arriving without a good Rome guidebook knew just where to go. The three churches on Piazza del Popolo are all dedicated to Mary, setting the right tone.

Along the north side of the square (flanking the Porta del Popolo) are two 19th-century buildings that give the square its pleasant symmetry: the Carabinieri station and the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo.

Two large fountains grace the sides of the square—Neptune to the west and Roma to the east (marking the base of Pincio Hill; steps lead up to the overlook with fine views to St. Peter’s and the rest of the city). Though the name Piazza del Popolo means “Square of the People” (and the square is a popular hangout), it probably derives from the poplar trees that once stood here.

One of Rome’s most overlooked churches, this features two chapels with top-notch art by Caravaggio and Bernini, and a facade built of travertine scavenged from the Colosseum. The church is brought to you by the Rovere family, which produced two popes, and you’ll see their symbol—the oak tree and acorns—throughout.

Cost and Hours: Free but bring coins to illuminate the art, daily 7:00-12:30 & 16:00-19:00, Fri-Sat open during lunchtime but often partially closed to accommodate its busy schedule of Masses; on north side of Piazza del Popolo—as you face the gate in the old wall from the square, the church entrance is to your right.

Visiting the Church: Go inside and enjoy the big view from the entrance. This Augustianian church is a fine example of Roman Renaissance architecture, exuding harmony, rhythm, and lightness as its arches lope to the front where a few rare Renaissance glass windows shine behind the altar. (Most church windows in Rome are from Baroque times, and are clear.)

Like a mini art-history class, this church exposes you to various periods: art of the 1400s, celebrating realism (in the Della Rovere Chapel); the 1500s, embracing humanism (Chigi Chapel); and the 1600s, getting emotional with Baroque and the Counter-Reformation (Cerasi Chapel).

In the Della Rovere Chapel (immediately right of the church entrance), Pinturicchio’s Nativity with St. Jerome illustrates the groundbreaking mastery of realistic landscape painting typical of the Renaissance. It’s a Bible scene but it’s set in 1490 Italy, so that parishioners could relate to it. Enjoy the delicate and harmonious scene with a stretch of ancient Rome’s brick wall included.

The Chigi Chapel (KEE-gee, second on the left from the entrance) was designed by Raphael and inspired (as Raphael was) by the Pantheon. Notice the Pantheon-like dome, pilasters, and capitals. Above in the oculus, God looks in, aided by angels who power the eight known planets. Raphael built the chapel for his wealthy banker friend Agostino Chigi, buried in the pyramid-shaped tomb in the wall to the right of the altar. Later, Chigi’s great-grandson hired Bernini to make two of the four statues, and Bernini—in good Baroque style—delivers with theatrics. In one corner, Daniel straddles a lion and raises his praying hands to God for help. Kitty-corner across the chapel, an angel grabs the prophet Habakkuk’s hair and tells him to go take some food to poor Daniel in the lion’s den.

In the Cerasi Chapel (left of the main altar) Carracci’s Assumption of Mary is pretty, classical, and forgettable. The highlights are the two Caravaggios on either side. Caravaggio’s Conversion of St. Paul (from 1601) shows the future saint sprawled on his back beside his horse while his servant looks on. The startled Paul is blinded by the harsh light as Jesus’ voice asks him, “Why do you persecute me?” In the style of the Counter-Reformation, Paul receives his new faith with open arms. The big butts, dirty feet, harsh foreshortening, and striking angels are all classic, melodramatic Caravaggio.

In the same chapel, Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St. Peter is shown as a banal chore; the workers toil like faceless animals. The light and dark are in high contrast. Caravaggio liked to say, “Where light falls, I will paint it.”

The wide, curving staircase, culminating with an obelisk between two Baroque church towers, is one of Rome’s iconic sights. Beyond that, it’s a people-gathering place. By day, the area hosts shoppers looking for high-end fashions; on warm evenings, it attracts young people in love with the city.  For more about the steps, see the Heart of Rome Walk chapter or

For more about the steps, see the Heart of Rome Walk chapter or  download my free audio tour.

download my free audio tour.

The triangular-shaped area between the Spanish Steps, Piazza Venezia, and Piazza del Popolo (along Via del Corso, see map on here) contains Rome’s highest concentration of upscale boutiques and fashion stores. For more, see the Shopping in Rome chapter.

On January 30, 9 B.C., soon-to-be-emperor Augustus led a procession of priests up the steps and into this newly built “Altar of Peace.” They sacrificed an animal on the altar and poured an offering of wine, thanking the gods for helping Augustus pacify barbarians abroad and rivals at home. This marked the dawn of the Pax Romana (c. A.D. 1-200), a Golden Age of good living, stability, dominance, and peace (pax). The Ara Pacis (AH-rah PAH-chees) hosted annual sacrifices by the emperor until the area was flooded by the Tiber River. For an idea of how high the water could get, find the measure (idrometro) scaling the right side of the church closest to the entrance. Buried under silt, it was abandoned and forgotten until the 16th century, when various parts were discovered and excavated. Mussolini gathered the altar’s scattered parts and reconstructed them in a building here in 1938.