Pilgrimage Churches

CHURCH OF SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE

CHURCH OF SAN GIOVANNI IN LATERANO

Rome is the “capital” of the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics. In Rome, you’ll rub elbows with religious pilgrims from around the world—Nigerian nuns, Bulgarian theology novices, students from Notre Dame, extended Mexican families, and everyday Catholics returning to their religious roots.

The pilgrim industry helped shape Rome after the fall of the empire. Ancient Rome’s population peaked at about 1.2 million. After Rome fell in A.D. 476, barbarians cut off the water supply by breaking the aqueducts, Romans fled the city, and the mouth of the Tiber River filled with silt and became a swamp.

During the Dark Ages, mosquitoes ruled over a pathetic village of 20,000...bad news for pilgrims, bad news for the papacy. Back then, the Catholic Church was the Christian Church. (Catholic means “universal,” and being a Catholic was the only allowable way to be a Christian.) Centuries later, during the Renaissance, popes sought to project an image of prestige and authority. The Church revitalized the city, creating a place fit for pilgrimages. Owners of hotels and restaurants cheered.

In the late 1580s, Pope Sixtus V reconnected aqueducts and built long, straight boulevards connecting the great churches and pilgrimage sites. Obelisks were moved to serve as markers. As you explore the city, think like a pilgrim. Look down long roads and you’ll see either a grand church or an obelisk (from which you’ll see a grand church).

Pilgrims to Rome try to visit four great basilicas: St. Peter’s Basilica, of course (covered in the  St. Peter’s Basilica Tour chapter in this book and on my

St. Peter’s Basilica Tour chapter in this book and on my  free audio tour), St. Paul’s Outside the Walls (see here), Santa Maria Maggiore, and San Giovanni in Laterano. The last two are covered in this chapter, as well as two other “honorable mentions”: The Church of Santa Prassede and the fascinating and central San Clemente.

free audio tour), St. Paul’s Outside the Walls (see here), Santa Maria Maggiore, and San Giovanni in Laterano. The last two are covered in this chapter, as well as two other “honorable mentions”: The Church of Santa Prassede and the fascinating and central San Clemente.

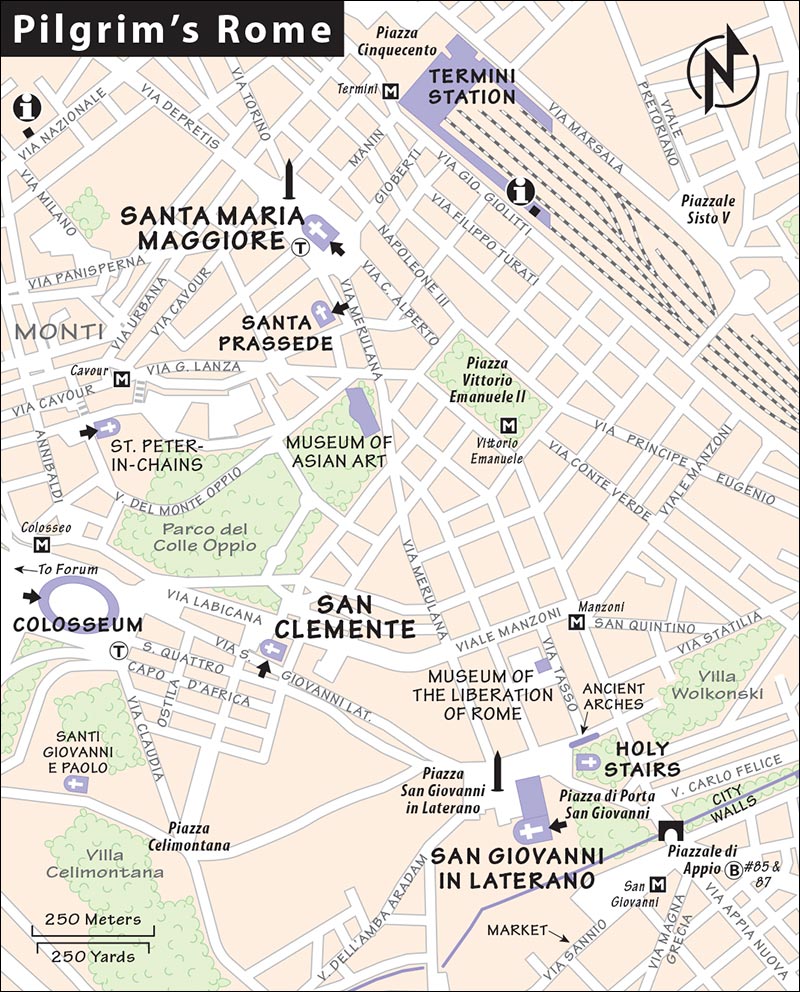

(See “Pilgrim’s Rome” map, here.)

Planning Your Time: Depending on your time and interest level, you may want to hit every sight described in this chapter—or maybe just visit one or two of the churches. Santa Maria Maggiore (and nearby Santa Prassede) have mosaics that date back to the first days of Christian Rome. San Giovanni in Laterano is grandiose and historic, and its Holy Stairs are a one-of-a-kind experience. San Clemente’s church-beneath-church layout leads you down—layer by mysterious layer—to a pagan Mithraic temple. To link this chapter’s sights efficiently, check their opening hours (Santa Prassede and San Clemente close for several hours at midday, as does the chapel at the Holy Stairs—the Holy Stairs themselves do not) and decide whether you want to travel on foot, by taxi, or on public transit.

Getting to the Churches: Both Santa Maria Maggiore and San Giovanni in Laterano, this chapter’s two biggies, are just a few minutes’ walk from Metro stops on line A. Santa Maria Maggiore is on Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore (Metro: Termini or Vittorio Emanuele), and San Giovanni in Laterano is on Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano (Metro: San Giovanni).

Santa Maria Maggiore is a block from Santa Prassede (see here for walking directions); from there, it’s about a 15-minute walk (or €6 taxi ride) to San Clemente, or a 20-minute walk to San Giovanni in Laterano. To avoid the walk from Santa Maria Maggiore to San Giovanni in Laterano, catch bus #16 or #714 (along Via Merulana), or take a taxi.

San Clemente (Metro: Colosseo) is an easy 15-minute walk from San Giovanni in Laterano, or a quick hop on tram #3 or bus #87. (The useful #87 connects Largo Argentina, Piazza Venezia, the Colosseo Metro stop, San Clemente, and San Giovanni in Laterano.)

Church of Santa Maria Maggiore: Free, daily 7:00-18:45.

Church of Santa Prassede: Free (but bring €0.50 and €1 coins for lights), daily 7:00-12:00 & 15:00-18:30, no visits during Mass (Mon-Sat 7:30 and 18:00; Sun 8:00, 10:00, 11:30, and 18:00).

Church of San Clemente: Upper church-free, lower church-€10, both open Mon-Sat 9:00-12:30 & 15:00-18:00, Sun 12:15-18:00.

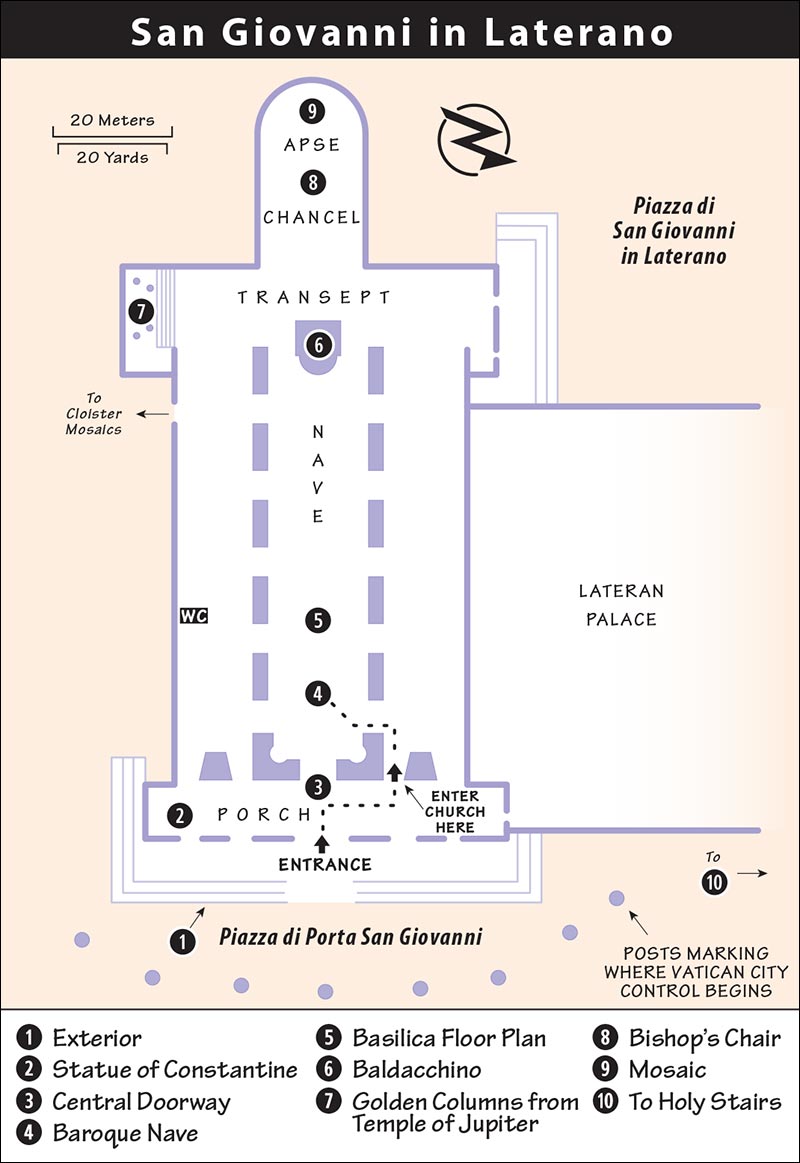

Church of San Giovanni in Laterano: Church—free, daily 7:00-18:30; cloister—€5, daily 9:00-18:00; church audioguide available (donation requested, or pay €10 for combo-ticket that includes audioguide and entry to cloister and Holy Stairs chapel, ID required as deposit; pick up at info desk near the main door, either inside or outside).

The Holy Stairs (Scala Santa), in a building across the street from the church, are free (Mon-Sat 6:30-19:00, Sun 7:00-19:00, Oct-March closes daily at 18:30). The chapel at the Holy Stairs costs €3.50 (Mon-Sat 9:30-12:40 & 15:00-17:10, closed Sun).

Dress Code: Modest dress is recommended (knees and shoulders covered).

(See “Pilgrim’s Rome” map, here.)

Four churches are covered in this tour. You can visit all four or pick and choose the ones that interest you most. See “Getting to the Churches,” earlier, for details on linking these sights.

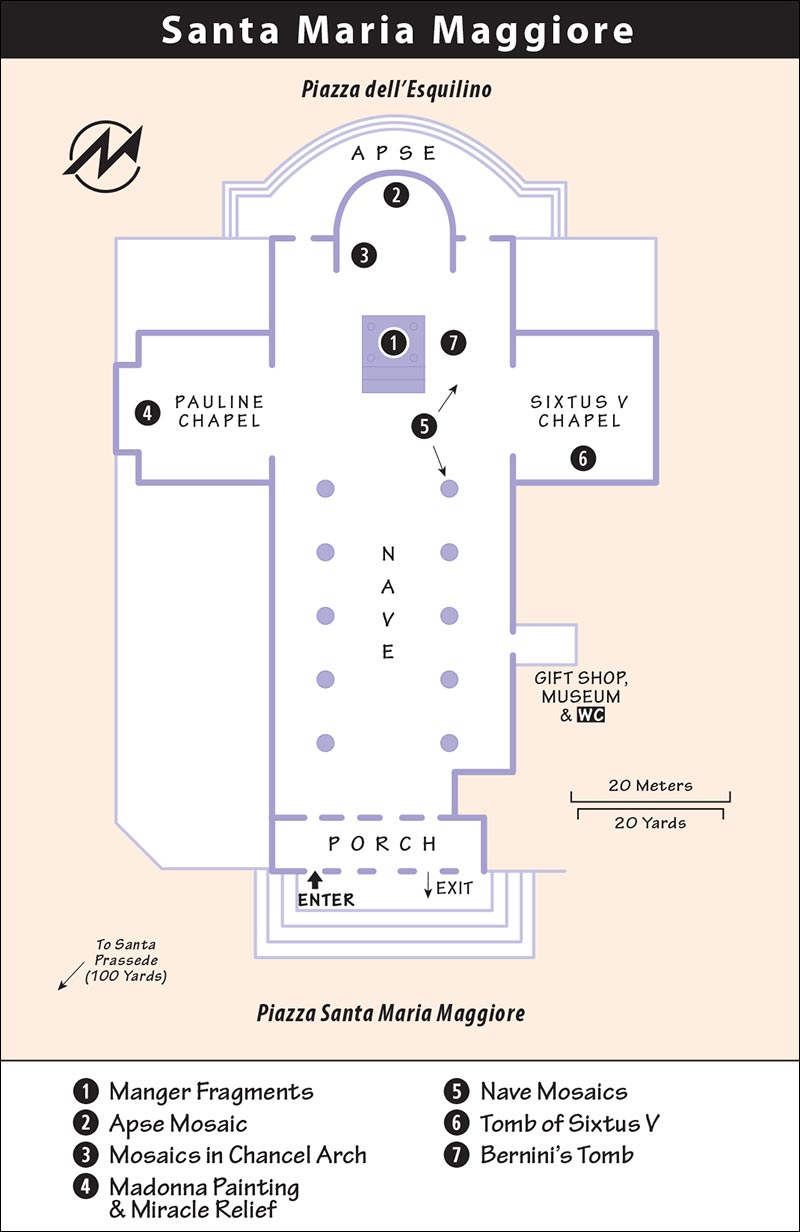

(See “Santa Maria Maggiore” map, here.)

The basilica of Santa Maria celebrates Holy Mary, the mother of Jesus. One of Rome’s oldest and best-preserved churches, it was built (A.D. 432) while Rome was falling around it. The city had been sacked by Visigoths (410), and the emperors were about to check out (476). Increasingly, popes stepped in to fill the vacuum of leadership. The fifth-century mosaics give the church the feel of the early Christian community. The general ambience of the church really takes you back to ancient times.

Start your visit by standing directly in front of the church next to the ornate column in the square. From here you can make out the earlier medieval church and bell tower (the tower was built in the late 14th century and is the tallest in Rome). The 13th-century mosaics of the medieval church survive behind the newer Rococo facade, which welcomes you like open theater curtains. The wings to the left and right were added for Vatican offices. Like Santa Maria Maggiore, most churches in Rome are much older than their facades. During the Baroque age, many were given facelifts.

Turn around and gape up. Mary’s column originally stood in the Forum’s Basilica of Constantine. This fifth-century church, built in her honor, proclaims she was indeed the Mother of God—a point disputed by hair-splitting theologians of the day.

When you step inside the church, you’ll be entering Vatican property—the church, although on Italian territory, has similar status to an embassy. The “Maggiore” in the church’s name indicates that it is one of the Catholic Church’s four “major basilicas” (all of them in Rome; the others are St. Peter’s, San Giovanni in Laterano, and St. Paul Outside the Walls).

Despite the Renaissance ceiling and Baroque crusting, you still feel like you’re walking into an early Christian church. You can feel the joy and lightness typical of early churches that were built before the heavier medieval styles took hold. The stately rows of columns, the simple basilica layout (nave flanked by side aisles), the cheery colors, the spacious nave—it’s easy to imagine worshippers finding an oasis of peace here as the Roman Empire crashed around them. (The 15th-century coffered ceiling is gilded with gold—perhaps brought back from America.)

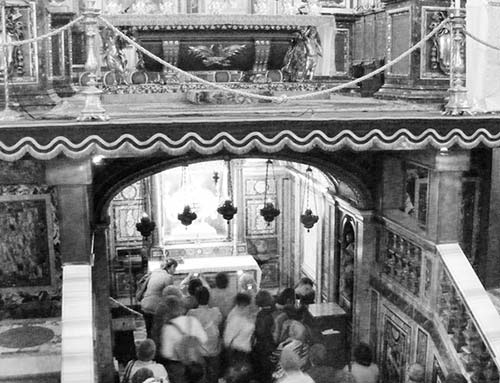

• The lighting boxes for three zones are in the back of the nave. If you put euro coins in each of the three slots, you give everyone two minutes of gorgeous art (and become the saint of light). In the center of the church is the main altar, under a purple and gold canopy. Underneath the altar, in a lighted niche, are...

A kneeling Pope Pius IX (who established the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in the 19th century) prays before a glass case with an urn that contains several pieces of wood, bound by iron—these pieces are said to be from Jesus’ crib (actually a feeding bin for animals). The church, dedicated to Mary’s motherhood, displays these relics as physical evidence that Mary was indeed the mother of Christ. (The church is also built on the site of a former pagan temple dedicated to Rome’s mother goddess, Juno.) Is the manger the real thing? Look into the eyes of pilgrims who visit.

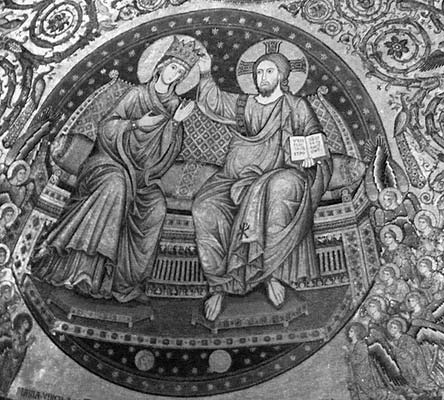

• The 18th-century canopy, inspired by the one in St. Peter’s, obliterates the medieval apse as if to draw all attention to the Baroque spectacle at the high altar. But in the apse, topped with a semicircular dome, you’ll find beautiful medieval mosaics.

This 13th-century mosaic shows Mary being crowned by Jesus—both are the same size and share the same throne. They float in a bubble representing heaven, borne aloft by angels. By the Middle Ages, Mary’s cult status was secure. Notice how the apostles are smaller and how even they dwarf the puny pope (lower left).

• Up in the arch that frames the outside of the apse, you’ll find some of the church’s oldest mosaics.

Colorful panels tell Mary’s story in fifth-century Roman terms. Haloed senator-saints in white togas (top panel on left side) attend to Mary, who sits on a throne, dressed in gold and crowned like an empress. The angel Gabriel swoops down to announce to Mary that she’ll conceive Jesus, and the Dove of the Holy Spirit follows. Below (the panel in the bottom-left corner) are sheep representing the apostles, entering the city of Jerusalem (“HIERVSALEM”).

• In the separate chapel to your left, over the altar, you’ll see a...

This chapel is a 17th-century Baroque addition to the church. Its altar, a geologist’s delight, is adorned with jasper, agate, amethyst, lapis lazuli, and gold angels. Amid it all is a simple icon of the lady this church is dedicated to: Mary.

Above the painting is a bronze relief panel showing a pope, with amazed bystanders, shoveling snow. One hot August night in the year 358, Mary appeared to Pope Liberius in a dream, saying: “Build me a church where the snow falls.” The next morning, they discovered a small patch of snow here on Esquiline Hill—on August 5—and this church, dedicated to Santa Maria, was begun. The grandiose tombs of two grandiose popes fill the chapel’s sides.

• Back out in the nave, on the other side of the altar, take a look at the...

The church contains some of the world’s best-preserved mosaics from early Christian Rome. If the floodlights are on, those with good eyesight or binoculars will enjoy watching the story of Moses unfold in a series of surprisingly colorful and realistic scenes—more sophisticated than anything that would be seen for a thousand years.

The small, square mosaic panels are above all the columns, on the right side of the nave. Start at the altar and work back toward the entry.

1. This is a later painting—skip it.

2. Pharaoh’s daughter (upper left) and her maids take baby Moses from the Nile.

3. Moses (lower half of panel) sees a burning bush that reconnects him with his Hebrew origins. (Now leap the arch to #4.)

4. A parade of Israelites (left side) flees Egypt through a path in the Red Sea, while Pharaoh’s troops drown.

5. Moses leads them across the Sinai desert (upper half), and God provides for them with a flock of quail (lower half).

6. Moses (upper half) sticks his magic rod in a river to desalinate it.

7. The Israelites battle their enemies while Moses commands from a hillside.

8. Skip this one, too.

9. Moses (upper left) brings the Ten Commandments, then goes with Joshua (upper right) to lie down and die.

10. Joshua crosses the (rather puny) Jordan River...

11. ...and attacks Jericho...

12. ...and then the walls come a-tumblin’ down.

• Head back toward the altar to see whether the gate to the right transept is open. If so, enter the late-Renaissance chapel (late 1500s); otherwise, skip ahead to Bernini’s Tomb. On the right wall of the chapel is a statue of a praying pope, atop the...

The Rome we see today is due largely to Pope Sixtus V (or was it Fiftus VI?). This energetic pope (1585-1590) leveled shoddy medieval Rome and erected grand churches connected by long, broad boulevards spiked with obelisks as focal points (such as the obelisk in Piazza dell’Esquilino behind Santa Maria Maggiore). Today the city of Rome has 13 Egyptian obelisks (and the ancient city had many more)—whereas all of Egypt has only five.

The centerpiece of this chapel (called the “Sistine Chapel,” but it’s not the more famous one) shows four angels carrying a gilded model of the new St. Peter’s dome, which was designed by Michelangelo. Finishing this project was a major part of Pope Sixtus’ legacy.

The white carved-marble relief panels decorating the pope’s tomb celebrate more of his accomplishments in reviving Rome (like the obelisks he raised and the buildings he commissioned).

• Back in the main nave, on the closest (right) side of the main altar, look down for an inscription on the first step between two white columns. This marks...

The plaque reads, “Ioannes Laurentivs Bernini”—Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680)—“who brought honor to art and the city, here humbly rests.” Next to it is another plaque to the “Familia Bernini.” It’s certainly humble...a simple memorial for the man who grew up in this neighborhood, then went on to remake Rome in the ornate Baroque style. (For more on Bernini, see here.)

• After looking around Santa Maria Maggiore, fans of mosaics, Byzantines, and the offbeat should consider a visit to the nearby Church of Santa Prassede, about 100 yards away.

Exiting Santa Maria Maggiore, find the obelisk in the distance (which would have directed medieval pilgrims down Via Merulana to the next big stop on their trail: the Church of San Giovanni in Laterano). Head in that direction just a few steps and follow a lane to the right, leading to a low-key side door where you enter Santa Prassede.

The mosaics at the Church of Santa Prassede, from A.D. 822, are the best Byzantine-style mosaics in Rome. The Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople (ancient Istanbul), was the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Unlike the western half, it didn’t “fall,” and its inhabitants remained Christian, Greek-speaking, and cultured for a thousand years while their distant cousins in Italy were fumbling for the light switch in the Dark Ages. Byzantine craftsmen preserved the techniques of ancient Roman mosaicists (who decorated floors and walls of villas and public buildings), then reinfused this learning into Rome during the city’s darkest era. Take the time to let your eyes adjust, and appreciate the Byzantine glory glowing out of the dark church.

Bring €0.50 and €1 coins to buy floodlighting and enjoy the full sparkle of the mosaics. Popping a coin into the box in the Chapel of St. Zeno (described below) saves you a trip to Ravenna, in northern Italy (famous for its Byzantine mosaics).

• The best mosaics are in the apse (behind the main altar; note another Baroque-era, “look-at-me” canopy over the high altar, like at Santa Maria Maggiore) and in the small Chapel of St. Zeno along the right (north) side of the nave.

On a blue background is Christ, standing in a rainbow-colored river, flanked by saints. Christ has commanded Peter (to our right of Christ, with white hair and beard) to spread the Good News to all the world. Beneath Christ, 12 symbolic sheep leave Jerusalem’s city gates to preach to the world. Peter came here, to what was the world’s biggest city, to preach love...and was met with a hostile environment. He turns his palm up in a plea for help. Persecuted Peter was taken in by a hospitable woman named Pudentia (next to him) and her sister, Praxedes (to the left of Christ, between two other saints), whose house was located on this spot. (The church is named for Praxedes.)

The saint on the far left (with the square halo, indicating he was alive at the time this was made) is Pope Paschal I, who built the church in the 800s in memory of these early sisters, hiring the best craftsmen in the known world to do the mosaics. Pope Paschal was also responsible for evacuating the bones of the early martyrs from the endangered catacombs outside the city walls and building several churches to contain them within the safety of downtown.

The ceiling is gold, representing the Byzantine heaven. An icon-like Christ emerges from the background, supported by winged angels in white, with lipstick and red cheeks. On the walls are saints walking among patches of flowers. In the altar niche, Mary and the child Jesus are flanked by the sisters Praxedes and Pudentia. On the side wall, the woman with the square blue halo is Theodora, the mom of the pope who built this. And in another niche is a supposed relic of the pillar upon which Christ was whipped on his way to Golgotha.

The chapel, covered completely with mosaics, may be underwhelming to our modern eyes, but in the darkness of Rome’s medieval era, it was known as the “Garden of Paradise.”

Imagine the jubilation when this church—the first Christian church in the city of Rome—was opened in about A.D. 318. Christians could finally “come out” and worship openly without fear of reprisal. (Still, most Romans were pagan, so this first great church was tucked away from the center of things, near the city wall.) After that glorious beginning, the church served as the center of Catholicism and the home of the popes until the Renaissance renovation of St. Peter’s and the expansion of the Vatican. Until 1870, all popes were “crowned” here. Even today, it’s the home church of the Bishop of Rome—the pope. Like Santa Maria Maggiore, it’s Vatican property.

• To reach the church from the San Giovanni Metro station, exit to the right onto Via Magna Grecia, then head toward the old city walls. Before you leave the square, look left to find the Via Sannio market, which sells clothing and some handicrafts every morning except Sunday. Then pass through the archways, hugging the left side of the street, to approach San Giovanni’s white, statue-topped facade.

The massive facade is 18th century, with Christ triumphant on the top. The blocky peach-colored building adjacent on the right is the Lateran Palace, standing on the site of the old Papal Palace—residence of popes until about 1300. Across the street to your right are the pope’s private chapel and the Holy Stairs (Scala Santa), popular with pilgrims (we’ll see the stairs later). To the left is a well-preserved chunk of the ancient Roman wall. Pass the three-foot-high granite posts surrounding the church to leave Italy and enter the Vatican State—carabinieri must leave their guns at the door.

• Step inside the portico and look left.

It’s October 28, A.D. 312, and Constantine—sword tucked under his arm and leaning confidently on a (missing) spear—has conquered Maxentius and liberated Rome. Constantine marched to this spot where his enemy’s personal bodyguards lived, trashed their pagan idols, and dedicated the place to the god who gave him his victory—Christ. The holes in Constantine’s head once held a golden, halo-like crown for the emperor who legalized Christianity. In the relief above the statue, you’ll see a beheaded John the Baptist.

• In the portico, take a look at the...

These tall green bronze doors, with their floral designs and acorn studs, are the original doors from ancient Rome’s Senate House (Curia) in the Forum. The Church moved these here in the 1650s to remind people that, from now on, the Church was Europe’s lawmaker. The star borders were added to make these big doors bigger. Imagine, those cool little acorns date to the third century.

• Now go inside the main part of the church. Stand in the back of the nave.

Very little survives from the original church—most of what you see was built after 1600. In preparation for the 1650 Jubilee, Pope Innocent X commissioned architect Francesco Borromini (rival to Bernini) to remake the interior. He redesigned the basilica in the Baroque style, reorganizing the nave and adding the huge statues of the apostles (stepping out of niches to symbolically bring celestial Jerusalem to our world). The relief panels above the statues depict parallel events from the Old Testament (on the left) and New Testament (on the right). For instance, in the very back you’ll see two resurrections: Jonah escaping the whale and Jesus escaping death. Only the ceiling (which should have been a white vault) breaks from the Baroque style—it’s Renaissance, and the pope wanted it to stay.

San Giovanni was the first public church in Rome and the model for all later churches, including St. Peter’s. The floor plan—a large central hall (nave) flanked by two side aisles—was based on the ancient Roman basilica floor plan. These buildings, built to hold law courts and meeting halls, were big enough to accommodate the large Christian congregations. Note that Roman basilicas came with two apses. You came in through the main entrance, which was designed to stress the authority of the place by slightly overwhelming and intimidating those who entered. When the design was adapted for use as a church, a grand and welcoming entry (the west portal) replaced one of the apses. Upon entering, the worshipper could take in the entire space instantly, and the rows of columns welcomed him to proceed to the altar.

• The canopy over the altar is called the...

In the upper cage are two silver statues of Sts. Peter (with keys) and Paul (sword), which contain pieces of their heads. The gossip buzzing among Rome’s amateur archaeologists is that the Vatican tested DNA from Peter’s head (located here) and from his body (located at St. Peter’s)...and they didn’t match.

• Standing in the left transept are the...

Tradition says that these gilded bronze columns once stood in pagan Rome’s holiest spot—the Temple of Jupiter, which was dedicated to the king of all gods, on the summit of Capitoline Hill (c. 50 B.C.). Now they support a triangular pediment inhabited by a bearded, Jupiter-like God the Father.

• In the apse, you’ll find the...

The chair (called a “cathedra”) reminds visitors that this is the cathedral of Rome...and the pope himself is the bishop who sits here. Once elected, the new pope must actually sit in this chair to officially become the pope. The ceremonial sitting usually happens within one month of election—Pope Francis took his seat on April 7, 2013.

• Under the semicircular dome of the apse, take a close look at the...

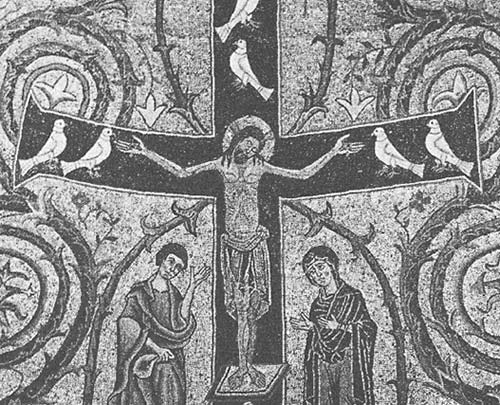

The original design dates from about 450 (although it was made in the 13th century and heavily restored in the 19th century). You’ll see a cross, animals, plants, and the River Jordan running along the base. Mosaic, of course, was an ancient Roman specialty adapted by medieval Christians. The head of Christ (above the cross) must have been a glorious sight to early worshippers. It was one of the first legal images of Christ ever seen in formerly pagan Rome.

• Fans of cosmatesque marble-inlay floor (c. 1100-1300) may want to buy a ticket to visit the cloister (enter near left transept).

The Holy Stairs are outside the church in a building across the street. To get there, exit the church, turn left, and cross the street to the nondescript building.

In 326, Emperor Constantine’s mother (St. Helena) brought home the 28 marble steps of Pontius Pilate’s residence in Jerusalem. Jesus climbed these steps on the day he was sentenced to death. Each day, hundreds of faithful penitents climb these steps on their knees while reciting a litany of prayers.

Covered with walnut wood spotted with small glass-covered holes showing stains from Jesus’ blood, the steps lead to the “Holy of Holies” (Sancta Sanctorum), the private chapel of the popes in the Middle Ages. With its world-class relics, this chapel was considered the holiest place on earth. The relics were moved to the Vatican in 1905.

You can climb the tourist staircases along the sides; look inside the “Holy of Holies” through the grated windows (you can see essentially the entire chapel through the grates, but if you’d like to go inside, you’ll have to buy a ticket at the ticket desk downstairs, near the entrance); and buy a souvenir at the gift shop (at the top floor, on the left). Or you’re welcome to climb the stairs on your knees (pick up the €2 booklet at the gift shop that gives the proper prayer for each of the 28 steps). If you’ve done a lot of praying in your life, but never accompanied your prayers with a little pain—actually a lot of pain—give this a try.

Nearby: After exiting the steps, look right and notice the broken arch of the Claudian Aqueduct (1st century A.D.), which once carried water to the city from more than 40 miles away. The Museum of the Liberation of Rome isn’t far behind it, just a few blocks down Via Tasso (see here). Then head toward the center of Piazza di San Giovanni in Laterano—straight ahead with your back to the Holy Stairs—for a look at the world’s tallest obelisk, dating from the 15th century B.C. (This is also the departure point for bus #16, which runs up Via Merulana to the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore.)

Here, like nowhere else, you’ll enjoy the layers of Rome—a 12th-century basilica sits atop a fourth-century Christian basilica, which sits atop a second-century Mithraic temple and some even earlier Roman buildings.

The church (at today’s ground level) is dedicated to the fourth pope, Clement, who shepherded the small Christian community when the religion was, at best, tolerated, and at worst, a capital offense. Clement himself was martyred by drowning in about A.D. 100—tied to an anchor by angry Romans and tossed overboard. You’ll see his symbol, the anchor, around the church. The painting on the ceiling shows Clement being carried aloft to heaven.

While today’s main entry is on the side, the original entry was through the courtyard in back, a kind of defensive atrium common in medieval times. To reach the original entry, go in through today’s main entrance, walk diagonally toward the right, and exit again into this courtyard. Turn around and face the original entry. (This courtyard is inviting for a cool quiet break, as I imagine it was for a visiting medieval pilgrim.)

Back inside the church, step up to the carved marble choir—an enclosure in the middle of the church (Schola Cantorum) where the cantors sat. About 1,200 years ago, it stood in the old church beneath us, before that church was looted and destroyed by invading Normans.

In the apse (behind the altar), study the fine 12th-century mosaics. The delicate Crucifixion—with Christ sharing the cross with a dozen apostles as doves—is engulfed by a Tree of Life richly inhabited by deer, birds, and saints. The message is clear: All life springs from God in Christ. Above it all, a triumphant Christ, one hand on the Bible, blesses the congregation.

The chapel in the back corner near the side (tourist) entrance—considered one of the first great Renaissance masterpieces—is dedicated to St. Catherine of Alexandria, a noblewoman martyred for her defense of persecuted Christians. The fresco on the left wall—which shows an early-Renaissance three-dimensional representation of space—is by the Florentine master Masolino (1428), perhaps aided by his young assistant, Masaccio. Studying the left wall, working from left to right, you can follow her story:

1. Catherine (lower-left panel), in black, confronts an assembly of the pagan Emperor Maxentius and his counselors. She bravely ticks off arguments on her fingers why Christianity should be legalized. Her powerful delivery silences the crowd.

2. Under the rotunda of a pagan temple (above, on the upper-left panel), Catherine, in blue, points up at a statue and tells a crowd of pagans, “Your gods are puny compared to mine.”

3. Catherine, in blue (upper-right panel, left side), is thrown in prison, where she’s visited by the emperor’s wife (in green). Catherine converts her.

4. Emperor Maxentius, enraged, orders his own wife killed. The executioner (upper panel, right side), standing next to the empress’ decapitated corpse, impassively sheathes his sword.

5. In the best-known scene (the middle panel on the bottom), Maxentius, in black, looks down from a balcony and condemns Catherine (in black) to be torn apart between two large, spiked wheels turned by executioners. But suddenly, an angel swoops in with a sword to cut her loose.

6. Catherine is eventually martyred (lower-right panel). Now dressed in green, she kneels before the executioner, who raises his sword to finish the job.

7. Finally, on the top of holy Mount Sinai (same panel, upper-right corner), two angels bear Catherine’s body to its final resting place.

Taking a few steps back, look up at the arch that frames the chapel, topped by the delightful Annunciation fresco (top of the arch) by Masolino. Also notice the big St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers (left pillar), with 500-year-old graffiti scratched in by pilgrims—now covered with glass.

Buy a ticket in the bookshop, and descend 1,700 years to the time when Christians were razzed on their way to church by pagan neighbors. The first room you enter was the original atrium (entry hall)—the nave extends to the right. (Everything you’ll visit from here on was buried until the 19th century.)

• Most of the way down the atrium, look for the “reversible” stone set into a metal rack that you can rotate.

This two-sided recycled marble burial slab—one side (with leafy decorations) for a Christian, the other for a pagan—shows how the two Romes lived side by side in the fourth century.

• Go through the nearby door into the nave, and walk to the far end. Five yards before the altar, on the left wall, look for the...

Clement (center) holds a secret Mass for early Christians back when it was a capital crime. Theodora, a prominent Roman (in yellow, to the right), is one of the undercover faithful. Her pagan husband, Sisinnius, has come to retrieve and punish her when—zap!—he’s struck blind and has to be led away (right side).

But Sisinnius is still unconvinced. When Clement cures his blindness, Sisinnius (very faded, lower panel, far right) orders two servants to drag Clement off to the authorities. But through a miraculous intervention, the servants mistake a column for Clement (see the shadowy black log) and drag that out of the house instead. The inscription (crossword-style on right, waist-high, very faded) is famous among Italians because it’s one of the earliest examples of the transition from Latin to Italian. Sisinnius encourages his servants by yelling “Fili dele pute, traite!” (“You sons of bitches, pull!”)

• In the far-left corner of the lower church (in the room behind the fresco you just saw), near the staircase leading down, is the...

Cyril, who died in A.D. 869 (see the modern, icon-like mosaic of him), was an inveterate traveler who spread Christianity to the Slavic lands and Russia—today’s Russian Orthodox faithful. Along the way, he introduced the Cyrillic alphabet still used by Russians and many other Slavs. Thanks to their tireless missionary work, Cyril and his brother Methodius are considered the most important figures in Slavic Christianity.

• Now descend farther to the dark, dank Mithraic temple (Mithreum; through a door immediately to the right of the altar and down steps). Nowhere in Rome is there a better place to experience this weird cult.

• The barred room to the left is the...

Worshippers of Mithras—men only—reclined on the benches on either side of the room. At the far end is a small statue of the god Mithras, in a billowing cape. In the center sits an altar carved with a relief showing Mithras fighting with a bull that contains all life. A scorpion, a dog, and a snake try to stop Mithras, but he wins, running his sword through the bull. The blood spills out, bringing life to the world.

Mithras’ fans gathered here, in this tiny microcosm of the universe (the ceiling was decorated with stars), to celebrate the victory with a ritual meal. Every spring, Mithras brought new life again, and so they ritually kept track of the seasons—the four square shafts in the corners of the ceiling represent the seasons, the seven round ones were the great constellations. Initiates went through hazing rituals representing the darkness of this world, and then emerged into the light-filled world brought by Mithras.

Rome’s official pagan religion had no real spiritual content and did not offer any concept of salvation. As the empire slowly crumbled, people turned more and more to Eastern religions (including Christianity), in search of answers and comfort. The cult of Mithras, stressing loyalty and based on the tenuousness of life, was popular among soldiers. Part of its uniqueness and popularity (in this very class-conscious society) was due to its belief that all were equal before God. It dates back to the time of Alexander the Great, who brought it from Persia. In 67 B.C., soldiers who had survived the bloody conquest of Asia Minor returned to Rome swearing by Mithras. When Christians gained power, they banished the worship of Mithras.

Facing the barred room are two rectangular Corinthian columns supporting three arches of the temple’s entryway, decorated with a fine stucco coffered ceiling.

At the far end of the hallway, another barred door marks the equivalent of a Mithraic Sunday school room. Peek inside to see a faded fresco of bearded Mithras (right wall) and seven niches carved into the walls representing the seven stages a novice had to go through.

Head back the way you came. On your right, watch for a very narrow ancient alleyway separating Roman walls barely three feet across. If it’s open, step in and imagine the first Western city to reach one million residents. Forget the two churches above you, and imagine standing on this exact spot and looking up at the sky 2,000 years ago. Now climb back through the centuries to today’s street level.