All of the hard work is now behind you (so you think, anyway!). The journey that began many months ago is beginning the lengthy (we hope) payoff period. Harvest time often begins utterly unexpectedly with a flash of color deep among the dense lower foliage of one of the tomato plants. One day, the tomatoes are hard and green, the dinner plates yet to be decorated with the anticipated harvest, the stomach rumbling with anticipation. And then, there it is: the first ripe tomato, just waiting for you to pick it, devour it, relish the flavor of summer, and become immersed in the nostalgia of so many tomatoes tasted throughout your gardening years.

There are different schools of thought on when to pick a ripening, or ripe, tomato. The decision depends upon several factors: the variety, the weather (temperature as well as precipitation or irrigation), the presence of marauding critters, and the status of your edible ripe tomato supply and its intended uses. It also depends on your knowledge of the variety and expected color, whether the variety is true to type, and where you are in the season (early, mid, or late). Trial and error will certainly be involved, and experimenting with a tomato you are trying for the first time can be very informative.

Generally speaking, when tomatoes are ripe for eating, they’re also ripe for seed saving. Good, viable seeds can be saved from tomatoes that are a bit short of fully ripe (when they are blushing, but still showing some green), though germination could be a bit low. Seeds saved from overripe tomatoes will be fine.

Of course, the flavor of a particular tomato will be at its peak when it’s perfectly ripe. Each variety, at peak ripeness, will also possess a characteristic texture. As a rule, less-ripe tomatoes have less sugar and could exhibit a more acidic, tart taste. The texture is likely to be firmer, perhaps even with a definite hardness or crunchiness. Tomatoes that ripen a bit beyond the peak state will become sweeter and less tart, which could result in unpleasant blandness. The texture in this case may become mushy or soft. Sometimes, an overripe tomato will begin to show nearly rotting “off” flavors that make the tasting experience very unpleasant indeed. It is wise to stay away from preserving or processing tomatoes that are overripe to the point of near collapse, as the off-flavors will taint your efforts.

Another aspect of ripeness is a softening of the flesh: give the tomato a gentle squeeze. Though a yielding of the flesh is a good general guideline, some varieties, particularly some of the more modern hybrids, are bred to be particularly firm, and even fully colored specimens will feel surprisingly firm.

I’ve watched many shoppers at farmers’ markets pick up tomatoes and smell them. Personally, I get little to no aroma from tomatoes (they are very different from slip melons, such as cantaloupes, in this regard); often, a strong smell associated with a ripe tomato is indicative of impending spoilage. Of course, each person “smells” differently, so others will have quite a different opinion or experience than mine.

Tomato colors are determined by the genes of each variety. The relationship between a particular tomato variety’s color potential and ripeness level is something best learned through experience. The particular mixture of carotenoids in the tomato flesh, including lycopene (yellow, orange, and red, as well as red and yellow bicolored types), and chlorophyll (green, which also contributes to the so-called “black” tomatoes), when overlaid with clear, yellow, or striped skin, determines the apparent ripe color of the tomato.

An important thing to remember is that the temperature tomatoes experience when ripening can significantly affect the color. Fruits that are exposed to midsummer sun may develop the pale and withered coloring indicative of sunscald. A red tomato that ripens at temperatures above 85°F will not develop a rich, deep pigment and will appear a washed-out pink or even yellow.

Most gardeners are familiar with the color journey of red tomatoes on their way to ripeness. But when growing tomatoes of other colors for the first time, it can be confusing for the gardener to know the right time to pick. Many a customer has told me, “I didn’t know when to pick the tomatoes because they never turned red, and I think they just rotted on the vine.” That is a shame, because many of the unusually colored tomatoes are among the very best in flavor.

It is also worth noting that tomatoes are edible along a continuum of apparent ripeness, from just past blush (fully colored, though perhaps paler than the fully ripened specimen) to as deep a color as the tomato reaches prior to the onset of rotting. When you throw in the factor of the uniqueness of each variety in terms of optimum ripeness, as well as variations from season to season, it becomes a matter of tasting to decide what you like, and when you will like it best with regard to picking time.

Red tomatoes — those that have yellow skins and deep pink or red flesh — go through degrees of color change on their way to full ripeness. The compound responsible for the red flesh is a carotenoid called lycopene. At the onset of color change, the tomato could be pale pink (indicative of the flesh color changing in advance of the skin color) or pale orange. As ripening continues, the fruit starts to take on the characteristic red-orange tone of the red tomato, with well-known examples being Better Boy, Roma, and Celebrity.

Early in the season the change from a faint tint of color to full, rich scarlet can take a frustratingly long time. Later, in the middle of the summer heat, when gradual ripening would be a welcomed occurrence (because of the glut of tomatoes becoming overripe on the kitchen counter), a faintly tinted tomato one day seems to become perfectly ripe in the blink of an eye.

Some varieties of red tomatoes will retain green coloring at the shoulders around the stem end. This genetic characteristic is often retained even when the lower majority of the tomato is fully ripe. Again, this is a case when familiarity with a particular variety is very helpful. I am sure many a tomato grower has mistakenly let some varieties rot on the vine while waiting for all of the green coloring to vanish.

Figuring out when pink tomatoes are ready to pick can be a bit tricky. Because the only difference between a pink and a red tomato is skin color (pink tomatoes have clear skin when ripe), not only is there great confusion even among experienced gardeners in determining whether a tomato is red or pink, but it is often impossible to make a final determination of color until the tomato is fully ripe. Red varieties that ripen during a hot spell may appear to be pink.

As pink tomatoes ripen, some varieties can, oddly, have a yellowish cast. Typically, they are pale, but occasionally dusky, shades of pink. Over time, they become a deep crimson pink. One thing to keep in mind if you are saving seed or cooking with a combination of red and pink tomatoes is that, once sliced, the tomatoes look essentially identical. Since red and pink tomatoes are basically identical in flesh color, layering cut slices of each type in a Caprese-type salad is not visually effective. Using whole pink and red cherry tomatoes in salads is a good way to highlight the color differences.

The various “black” tomatoes (with purple or brown hues) can be quite tricky to assess for ripeness, especially by those who are unfamiliar with them. Black varieties that retain green shoulders even when very ripe are a bit easier to distinguish; otherwise, they may appear from the outside to be simply pink or red varieties.

Tomatoes of all colors take on a deeper hue as they ripen on the counter, but I’ve found that this is particularly striking with the black varieties. It is also important to remember the correlation between temperature and pigment formation. It is, therefore, likely that people growing black varieties in different climates experience different depths of hue, leading to all sorts of interesting “discussions” (sometimes arguments) on Internet forums.

Since the appearance of and popularity boom for the black varieties is quite recent (beginning around 1990), we are all still learning about the optimum time to harvest and eat these uniquely colored varieties. If you’re growing black varieties for the first time, be sure to observe the color changes closely as the tomatoes ripen, and pick fruit at various stages of ripeness, sampling them to get a sense of how they develop color and ripeness in your particular garden.

Assessing the ripe state of orange and yellow tomatoes is fairly easy once you know which color to expect. The continuum of hues is vast, from the palest canary yellow to deep gold, and it is more challenging — for me, anyway — to delineate yellow from orange with certain varieties. To further complicate things, some yellow tomatoes darken with age, and oranges and yellows possess different degrees of flavor at different colors. A perfect example of this is the popular, delicious hybrid cherry tomato Sun Gold. Since it is a tomato machine, you’ll have plenty of opportunities to experiment with picking Sun Gold at different stages of ripeness. At pale orange with perhaps a faint greenish tint, Sun Gold has a very full flavor with a sharp acidic tang, which is quite delicious. As it passes to medium orange, the sweetness and complexity (some call it a tropical fruit element) comingle with the still-present tang, creating what many consider the perfect tomato-eating experience. Finally, Sun Gold will turn into a rich, deep orange, and the sweetness is nearly overwhelming. We’ve found uses for Sun Gold at each of these stages. However, care is needed, since this thin-skinned cherry tomato loves to crack just as it is turning from pale to medium orange, especially if the plant is heavily watered or enjoys a heavy rainstorm.

Hugh’s

In general, the best guidance to offer is to experiment. Pick some orange or yellow tomatoes at various stages of ripening; taste some, and allow some to sit on the counter for further ripening and color development. From my experience, the evolution of flavor with increasing ripeness is present in all tomatoes, though at a lesser extent than with Sun Gold. There is so much to learn about how tomato flavors evolve with ripeness.

Let’s look at a representative selection of larger-fruited (non-cherry) tomatoes along the yellow-to-orange range. The most pale-colored examples, such as Hugh’s or Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, ripen to a very pale yellow and when extremely ripe often develop a pale pink blush at the blossom end. Still yellow, but of a richer, more buttery color, are Lemon Boy and Golden Queen. Once we move from yellow into orange, the presence of the pink blossom-end blush isn’t typically seen, and the pale orange Persimmon and Yellow Brandywine are the color of a traditional pumpkin, whereas Kellogg’s Breakfast reaches the deep hue of a navel orange. It isn’t difficult to judge when any of these are ripe and ready to eat — the key is knowing what is to come, and not waiting for them to turn red!

Bicolored. Quite a few of the yellow tomatoes have a tendency to develop a very pale pink blush at the bottom, and rarely, this will extend into the flesh as a bright crimson ring in the tomato core. Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom is a perfect example of this. And taking things just a bit further finds us at the large, yellow tomatoes that are swirled and streaked with shades of pink and red. These tomatoes, the so-called bicolored beefsteaks, are, to me, the “peaches” of the tomato garden. Often the coloring evolves and grows as they sit on the counter. These bicolored beefsteaks are not at all uniform, and each tomato on the plant will develop different color patterns.

Until I tasted Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, my view on orange- or yellow-fleshed tomatoes was one of slight indifference; most of them were on the mild, approaching bland, side. How wrong I was. Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, though temperamental in terms of consistency and yield from year to year, can often elevate to the top ranks of tomato flavor. Possessing a superbly uniform, nearly creamy, juicy texture, it is a loud tomato that fills the senses, perfectly balanced between tart and sweet. It is an annual highlight on our tasting plates.

Serves 6–8

Through the years, we’ve sampled hundreds of versions of this cool, fresh tomato treat. Many of them were truly delicious, but after this interpretation by chef Sarig Agassi (of Zely and Ritz restaurant in Raleigh, North Carolina), no other gazpacho can compare. It is outstanding, simple to make, and remarkable in the intensity of tomato flavor. Be sure to use only the best-flavored tomatoes, as they definitely take center stage. This is a soup that really lets one play with hues — in terms of both color and flavor characteristics (full, gentle, sweet, tart). For a knockout bright yellow soup, try to find Hugh’s, Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, Lemon Boy, or Azoychka. The large, meaty red-yellow bicolored types, such as Lucky Cross, Ruby Gold, or Pineapple, make for a gentle, sweet soup that exhibits sparkles of pink among the warm yellow tones. Be adventurous, be creative, and have fun with your tomato combinations, but beware when mixing green- and red-fleshed varieties: the resulting brownish color will not be nearly as appetizing as the flavor.

We’ve all been to parties and sampled an innocuous-looking bowl of red salsa, only to find ourselves gasping, sneezing, or escaping to blow our runny nose because of the unexpected level of fire. This can be avoided by color-coding salsas by their level of heat. The recipes below telegraph the eating experience to the unsuspecting salsa victims: green is mild, amber is medium to intense, and red is hot.

At least one hour before serving, combine all the ingredients in a bowl. Before serving, be sure to taste for heat level and make adjustments as needed. If you’ve made it too hot, add more chopped tomatoes and scallions to dilute the fire.

Tomato fruit flavor evolves and changes as the season elapses. Some people find the first-picked tomatoes are the best tasting; most find that it is the main crop that tastes the best. Most seem to agree: tomatoes that come on late, after the weather cools (especially at night), just don’t have the flavor of the early or main-crop fruits.

Flavor in a particular variety can vary widely from season to season (certainly influenced by the weather any given year). It can also vary by specific location and specific cultural practices, such as fertilization and location (ground or container). Any disease that affects a plant will negatively influence flavor. And maybe just as important is the relationship between perception (what we see and our expectation) and what we taste. All avid tomato gardeners develop biases over time. We probably hold tight to our early favorites and become more resistant to admitting that recently found and tried varieties can possibly meet our expectations and match our experiences of those first few heirloom tomatoes grown long ago.

White tomatoes are a genuine garden curiosity. Many people find them to be quite mild and sweet tasting. Others note that eating them slightly under-ripe, which ensures the presence of a tart element, intensifies the flavor. When at optimum ripeness, the color of the white varieties is more accurately described as ivory (white with a slight yellow tint), and the yellow coloring is more pronounced at the tomato shoulder. Fruit that grow inside the plant, hidden by foliage, could end up more white than those that are exposed to the sun.

Tomatoes that ripen to more than one color are fascinating to observe as they pass from formation to development and through to full ripeness. Tomatoes with stripes tend to be obviously different from the start, typically showing distinct vertically oriented, jagged stripes of dark and pale green. Over time, the true coloring starts to emerge, which is quite complex. All color combinations seem to be possible, and the colors change and deepen as the varieties move from partial to full ripeness. The swirled and marbled varieties don’t show their true colors until fully ripe; often the red component of the red and yellow bicolored types deepens with time. The interior colors of the striped and marbled/swirled varieties could be uniform or a combination of several colors. My only advice for these types is to experiment picking at different stages and see what you like best.

The most complex, and often superbly delicious, varieties are those that retain their green coloring when fully ripe. My seedling customers often have to be prodded to try the green-when-ripe types, simply because they’re confused about when to pick them. Two types of tomatoes retain green flesh at ripeness: those that develop yellow skin (which are easier to judge for ripeness), and those that keep clear skin (the true mysteries of the tomato garden).

Green with yellow skin. Those with yellow skin, such as Cherokee Green and Evergreen, scream out their ripeness by appearing as rich amber yellow. The surprise comes in the slicing, when the glowing green interior is exposed.

Green with clear skin. As for the clear-skinned green varieties, such as Green Giant and Aunt Ruby’s Green, I’ve learned that it is quite possible to determine ripeness by observing them, but it takes practice and experience. When at optimum ripeness, these types develop a very pale pink (quite lovely) blush at the blossom end. Of course, the tomato will yield a bit to a gentle squeeze. Once you grow these clear-skinned green varieties for a few seasons, you will find that you can tell when they are ripening by their appearance from a distance, if you are really observant. Though hard to describe, the ripe ones just look different — still green, but warmer than the cold-looking green of unripe tomatoes.

Full-size tomatoes can be picked when underripe and stored in such a way that they will ripen to the expected colors. The last fruit to set that reach full size and need to be gathered before frost can be stored in paper bags with an apple. Ethylene gas naturally emitted by the apple will act as a ripening agent for the tomatoes. Though they will reach full color, the flavor and texture of green-picked, indoor-ripened tomatoes are typically inferior to those ripened on the vine. However, fruit picked just shy of fully ripe (perhaps before a heavy rain, for example, or to avoid damage from critters) will ripen on the shelf within a few days and will possess most of the flavor of vine-ripened fruit.

If you grow more than a handful of tomato plants, and you grow them well, the eager, frustrated anticipation that makes that first tomato take forever to harvest will soon be replaced with the panic of being overwhelmed with tomatoes. You’ll be asking yourself a number of questions. How long can they sit on the kitchen counter? Should I put them in a bowl or line them up single file? Should they sit stem side up or down? Should they go into the refrigerator, the garage, or outdoors on the picnic table?

Don’t refrigerate. The jury is in, and the vast majority of cooks, gardeners, and tomato aficionados agree that a tomato should never see the inside of a refrigerator. Two things seem to happen to a tomato once it is refrigerated. The texture changes, softening to what can best be described as “mushy.” In addition, many of the chemical compounds responsible for the aroma and flavor of tomatoes are most likely highly volatile and are best experienced at higher temperatures. Chilling surely reduces the ability of many of the flavor elements to reach your nose and taste buds, leading to a flat, simpler taste experience.

Stem side down. An article in Cook’s Illustrated magazine from 2013 concurred that it is far better to store tomatoes stem side down. The testing staff reasoned that the fruit stays fresher when any entry for air at the stem end is inhibited. They do, however, say that if a bit of stem remains attached, it is best to store the tomato stem side up.

Large, ripe tomatoes, such as these fine specimens of Cherokee Purple, should be stored stem end down.

Following are some of the lessons we’ve learned about dealing with the tomato harvest, especially when ripe tomatoes really start to come in at a rate far greater than anyone’s ability to deal with on a daily basis.

Most large-fruited heirloom tomatoes ripen gradually in a single cluster, and they also can exhibit great size variation, as seen in the cluster of Ferris Wheel shown here.

It usually happens that one day I walk into the garden and find that there’s a single ripe cherry tomato. The first question arises: “Should I eat it, or bring it to my wife?” That first ripe cherry tomato seems to be a sort of cosmic trigger — the next day, or the day after that, two or three more are waiting. The production of ripe fruit accelerates, and soon it isn’t a question of whether to eat or share; it gets to the point where I always bring a small bowl with me on my garden walk. Salads certainly become very pleasant now that a supply of fresh, ripe cherry tomatoes enhance the ingredient list.

Once the size of the ripe tomatoes increases, the cherry tomatoes may be forgotten. When the medium-size tomatoes begin to ripen, the kitchen counter lineup begins. Skewering, grilling, and slicing become possible, and the cookbooks, recipe cards, and Internet recipe searches become part of the daily ritual. The medium-size, round tomatoes typically yield heavily, and certainly take center stage from the cherry tomatoes, though we still enjoy snacking on bowls of cherries throughout the season.

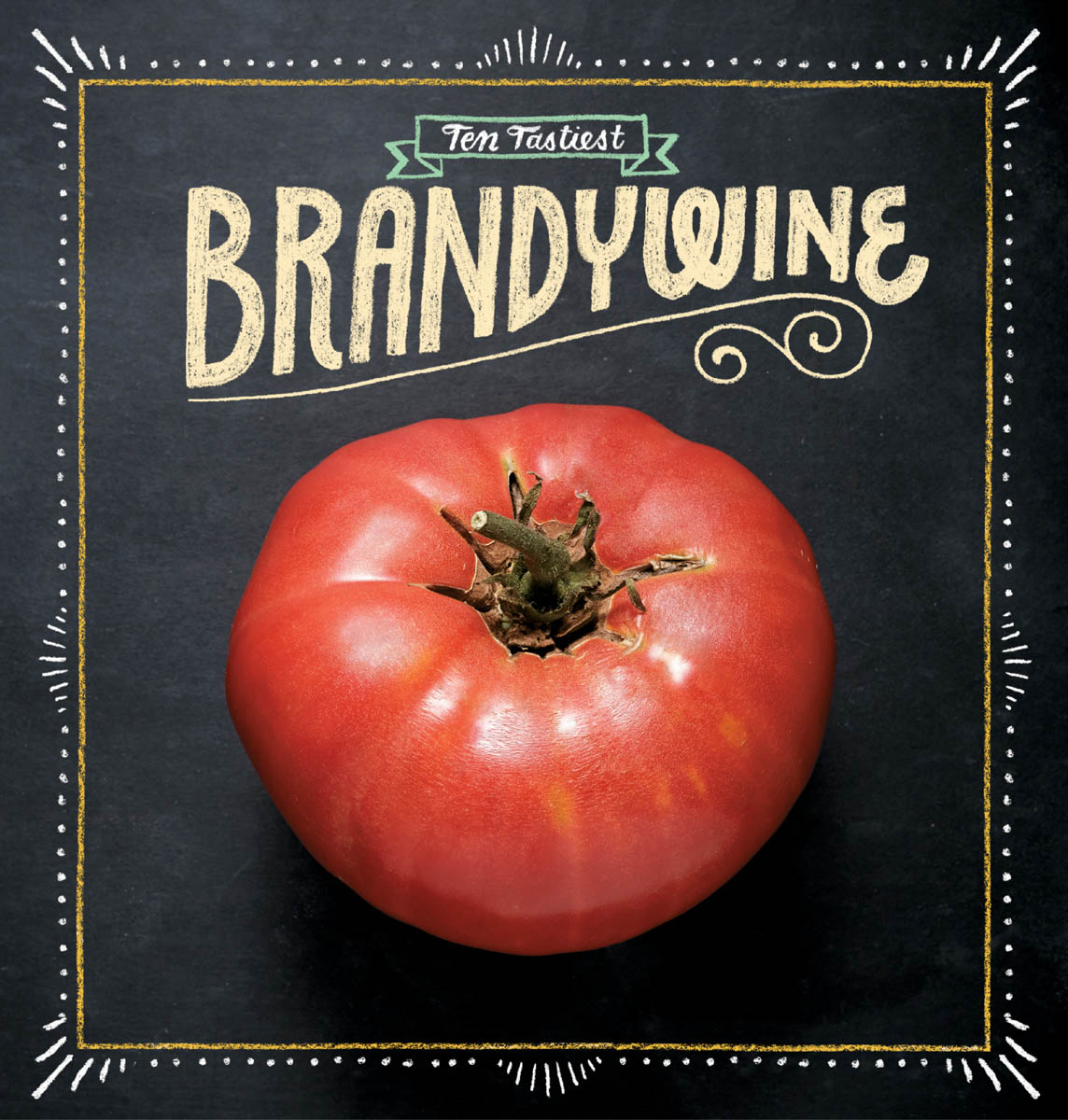

Finally, the big ones arrive. The most enjoyable part of the tomato harvest season is when the sumptuous, colorful, large-fruited varieties begin to ripen, and we harvest big baskets of Brandywines, Mortgage Lifters, and Cherokee Purples. The kitchen counters are now cleared, so that the tomatoes can be clustered and lined up on every available space. We stand back and admire our bounty.

And then it hits us. We’ve gone from drooling, eager anticipation to dealing with the daily harvest to being utterly overwhelmed.

We’ve found that the large-fruited tomatoes simply don’t hold up for as long once they’re picked. They ripen very quickly, and we often find that a half-ripe tomato picked one day, lined up next to its buddies, appears to be fully ripe the next day. We become aware of a foul odor and a puddle of liquid; sometimes tomatoes have internal issues (a worm going to work on the flesh, or internal blossom end rot), and these manifest themselves as pools of noxious rotten tomato liquid. Fruit flies are quickly drawn to such puddles as well, so we regularly monitor the condition of our fragile, ever-changing tomato collection. Wasting a single, perfect, lovely tomato seems like such a crime. That’s when it’s time to share!

Despite being a bit overwhelmed by our harvest, we relish the first day of a given garden season when we can overlap slices of Brandywine, Cherokee Purple, Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, Green Giant, and Kellogg’s Breakfast with fresh mozzarella cheese, drizzle with extra virgin olive oil, and top with some shredded basil leaves, a dusting of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, and a few grinds of black pepper and call it lunch or dinner. Great tomatoes taste best when you eat them in their most basic, unadorned form. What makes the experience even more precious is the knowledge that the delicious, large-fruited heirlooms can be the most finicky in terms of consistent yield and flavor, as they seem to be the variety type most affected by cultural or seasonal conditions. If it’s a decent season, though, we quickly find that we are inundated with tomatoes.

Brandywine is a tomato that earns its lofty reputation. It is maddeningly inconsistent year to year, but when it does well, it is the most magnificently flavored tomato in my garden. Akin to other tomatoes on my list, it is a tomato lover’s tomato, as the flavors explode in the mouth, sweetness and tartness exquisitely balanced.

The perfectly ripe tomato in the peak of its always-too-short season is the most poignant of fresh produce conundrums. Over the years, we’ve discovered some good ways of dealing with tomato overabundance — share with neighbors, hold tomato tastings with family and friends, and hunt through the recipe cards and cookbooks to find as many ways to enjoy them as possible. This is also the perfect time for seed saving (see Saving Seeds) as well as preserving your abundance for later (see Preserving the Harvest).

Knowing that the cherry tomatoes will start the harvest and then quickly go into overdrive production, consider them the working-in-the-garden treat to keep the plants under control, and if you manage to have a bowl of them to bring into the house, use them in salads, skewer and grill them, or make the wonderful and unique Cherry Tomato Pesto. Go through the bowl frequently and remove any that are cracked; in fact, during the picking process, toss all of the cracked ones, as they will just hasten the ripening (and overripening) of their bowl companions. Be sure to save seeds from those first-picked varieties on a given plant; because cherry tomatoes are quite seedy, just a handful of cherries will provide all the seeds you need.

Pick medium-size tomatoes (4 to 8 ounces) in a range of ripeness, from half-ripe to fully ripe, so that you’ll have tomatoes for immediate use as well as a few days down the line. This type of tomato — ranging in size from the golf ball of Tiger Tom and Green Zebra to the tennis ball of Eva Purple Ball — can be a bit awkward to use, being too small for a sandwich, but too big for use in a salad without cutting them into pieces.

I’ve found that as long as they are crack free, medium-size tomatoes last quite a long time post-harvest sitting on the kitchen counter. We do indeed cut them up for salads, but they are also wonderful brushed with a bit of olive oil and grilled whole, halved for use in tomato sauce, or canned.

I’ve learned from experience that it is a good idea to pick most of the really large tomatoes, often the most treasured varieties of all, at 50 to 75 percent ripe, rather than let them go fully colored on the vine. Since these often take the longest to ripen, can sometimes be the most vulnerable to lower yields (due to flowering in conditions not ideal for fruit set), and contain, as a group, many of the real flavor stars, it is important to get them safely harvested before a bird, deer, or some other hungry critter gets to them. Picking them a bit prior to full ripeness also provides more time to enjoy them, as fully ripened specimens go from perfect to nearly rotting quite quickly.

Because of their small size, cherry tomatoes typically ripen earlier in the season and provide the first chance to use homegrown tomatoes in favorite recipes. Their small size also makes them flexible to use, and because they’re so prolific, you know you’ll have plenty. Later in the season, the real culinary stars of the summer ripen — the large-fruited tomatoes. It is with these treasures that the flavor nuances emerge. And the rainbow of colors provides seemingly endless possibilities in the kitchen.

Our standard recipe for traditional pesto included lots of fresh basil combined with olive oil, garlic, pine nuts, and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, all pulsed in a food processor to make a thick paste. It never occurred to us to use tomatoes in the preparation of pesto until seeing a recipe showcased in an episode of Lidia’s Italy cooking show. By substituting cherry tomatoes for some of the basil, swapping toasted almonds for the pine nuts, and omitting the cheese, something entirely different emerges. We use the cherry tomato pesto just like the standard type: ample quantities tossed with cooked pasta, festooned with Parmigiano-Reggiano.

Any intensely flavored cherry tomato will work wonderfully in this recipe. With Sun Gold tomatoes, the result is a lovely pale orange. Black Cherries, Green Grapes, Snow Whites, Sweet Millions, Galinas — one could picture a plate laid out with splashes of different cherry tomato pestos, like a painter’s palette, for a gorgeous and artistic meal.

This is a lovely-looking dish that is perfect for a rainbow selection of cherry tomatoes (or any tomato cut into bite-size pieces). The success of this dish relies on the intensity of the flavor of the tomatoes, so be sure to use your best. This dish tastes wonderful prepared several hours in advance and then allowed to chill in the refrigerator for a few hours. We’ve served it as a main dish for lunch or a light dinner, with or without bread, or by itself or as a salad over lettuce. The flavors are clean and bright, though savory from the garlic and paprika, with as much fire as you desire, which you control with the amount and type of hot pepper.

The dish involves tossing freshly prepared couscous (small grained, not the larger Israeli couscous) with cubes of roasted sweet peppers, diced cucumber, minced jalapeño or serrano peppers, and lots of halved sweet cherry tomatoes. Consider using a mix of colors, flavors, and sizes, including yellow varieties such as Lemon Drop, Galina, or Egg Yolk, the rich purple Black Cherry, pinks such as Sweet Quartz or Dr. Carolyn’s Pink, the ubiquitous Sun Gold, and maybe some red Tommy Toes or Sweet Millions. Toss all the ingredients together and then mix in a dressing of olive oil, minced garlic, salt, pepper, lemon juice, ground cumin, and sweet paprika.

This dish simply layers thick slabs of fresh tomatoes with fresh mozzarella cheese, topped with basil, a drizzle of high-quality extra virgin olive oil, a few coarse grinds of rock salt and black pepper, and a dusting of grated Parmigiano-Reggiano. It reminds me of a great classical violin or piano concerto. The tomato is the solo instrument and takes (and deserves) center stage, but it is enhanced by all of the other ingredients/instruments. And, as with music, it is not too hard to tell if something is out of tune. To me, this is the ultimate test for proclaiming the relative quality level of a particular tomato variety.

This is a dish we reserve for the harvest stars of the tomato garden, including Brandywine, Green Giant, Cherokee Purple, Lillian’s Yellow Heirloom, Great White, German Johnson, Dester, Cherokee Chocolate, Cherokee Green, Yellow Brandywine, Nelson’s Golden Giant, Nebraska Wedding, Andrew Rahart’s Jumbo Red, Nepal, Aker’s West Virginia, Lucky Cross, Black from Tula, Stump of the World, and Polish.

A bountiful harvest of tomatoes is a cause for celebration and a catalyst for impromptu, or even more organized, get-togethers. This is especially true if lots of varieties are available to sample, and they are unfamiliar, interesting, or unusual. Nothing draws a crowd like a tomato tasting. The real value in having others around while sampling the harvest is in obtaining a range of opinions, since each person possesses unique sensory abilities, as well as preferences.

During our annual seedling sales, we’re often asked about the differing flavors of our many selections. In 2002, a longtime seedling customer, and now gardening friend, Lee Newman, and I decided it would be fun to gather a small group of my customers for a midsummer get-together at a local park, where we would pool our harvests and have an informal tasting. Lee came up with the name Tomatopalooza, and it quickly became an eagerly anticipated and popular annual event. Starting off with just a few dozen home-gardening tomato enthusiasts, the event swelled to more than 100 people, providing an opportunity to taste, at no charge, up to 200 different tomatoes.

Rather than giving each grower their own station, we arrange the tomatoes by color on long tables. Our volunteer staffers cut the tomatoes into pieces during the event, to keep them from developing off-flavors from waiting in the summer heat. We taste, take notes, and hold discussions.