Figure 2.1

Estimated market share range of world retail grocery channels (Source: Friends of the Earth, 2003; Brown, 2005; Fearne et al., 2005; United Nations Development Programme, 2005)

Chapter 2

Food Events and the Local Food System: Marketing, Management and Planning Issues

As noted in Chapter 1, food events are different. Their connection to a product which is not only part of everyday life, but also has particular cultural, economic and environmental significance, means that food events have to meet a different range of consumer and producer expectations than other events. Food events are obviously connected to the promotion of food products, but even here the dimension to place of production becomes an important element of branding and quality assurance. Although food events have long been a part of the distribution channel for food and agricultural products, in recent years there has been a significant emphasis placed on their potential to bypass the food retail and distribution channels that are dominated by supermarket chains. As Brown (2005, p. 1) observes:

Supermarkets now dominate food sales in developed countries and are rapidly expanding their global presence. At the same time, international mergers and acquisitions and aggressive pricing strategies have concentrated market power in the hands of a few major retailers.

The market power of retailers is considerable. The top 30 supermarket chains and food companies account for about one-third of global grocery sales and this market share is increasing rapidly as a result of urbanization and the rapid economic growth of two of the world’s largest markets, China and India. Wal-Mart, the world’s largest company, accounts for more than one-third of US food industry sales. In the UK the top five supermarkets account for 70 per cent or more of grocery sales which is double the share that existed at the end of the 1980s, while throughout Europe there is increasing consolidation in the retail sector (Brown, 2005; Hall and Mitchell, 2008). The 2005 Human Development Report reveals that these 30 supermarket chains are responsible for over one-third of global grocery sales (United Nations Development Programme, 2005, p. 142). Brown (2005) suggests that this proportion is likely to increase in future, with the market compressing to as little as 10 major firms, as the industry continues to consolidate. Despite notable exposure in food retailing literature (Retail World, 2007) outlets such as local grocers are declining in the face of increasing competition from the supermarket retailers (Clarke, 2000). Figure 2.1 indicates the estimated range of market share within four different retail grocery channels on a global basis.

Figure 2.1

Estimated market share range of world retail grocery channels (Source: Friends of the Earth, 2003; Brown, 2005; Fearne et al., 2005; United Nations Development Programme, 2005)

Although estimates of the globalization of retail grocery channels and their dominance by supermarkets vary substantially, it is nevertheless clear that they do dominate, and that the extent of their domination and their potential gatekeeper role in retail is also growing.

One of the more significant responses to the rise of the retail dominance of supermarket chains and their global supply and distribution channels has been the rise of ethical consumerism. Ethical consumerism is generally associated with the consumption of goods and services the production of which does not result in harm to people, animals or the environment (Rayner, 2002), and covers a range of manifestations of new sustainable consumption and production practices often focused on such concerns as fair trade, organic and free range produce, human rights, environmental sustainability and the production of consumer goods. Another element of ethical consumerism, is a strong stress on ‘buying local’ as a means not only of potentially reducing how far food has to travel and therefore impacts the environment, but also as a means of showing support for local producers. Events are very significant to such a strategy via the running of farmers’ markets. However, localization as a strategic response to the globalization of food chains should not be regarded as a ‘ring-fenced’ approach to the world. For example, farmers’ markets and the other production aspects of local food can be an attraction for tourists and therefore local food systems are tied into the global via the tourism system, while more traditional promotional and distribution networks maintain global linkages to consumers (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2

Place and producer response to globalization of food production

Both industry and public events can contribute to a region’s tourism development by serving to attract visitors from outside of the destination. Industry events attract business visitors and contribute to the development of economic networks. Visitors to industry events and conferences also tend to have an extremely high per day spend. Yet, despite this, the tourism focus on food and wine events tends to be on public events, which are regarded as providing an opportunity for destinations to establish themselves as food tourism destinations, promote the regional brand and contribute to regional economic development (Brown et al., 2002). For example, in reflecting on the experience of the Breedekloof Outdoor Festival in South Africa, Tasslopoulos and Haydam (2006, p. 69) commented that, ‘Wine events provide wine regions with an opportunity to promote the wine and build market identity and, therefore, result in the transition of traditional rural areas into modern service economies’. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly recognized that events need to be seen not just as an opportnity to increase visitor numbers or sell produce, but also to seek to build brands at various scales (i.e. region, producer) (Mowle and Merrilees, 2005), often by using the event to increase brand loyalty, and by creating long-term relationships with consumers. However, it is also important for food event organizers to consider the communities in which they are located and connected so as to ensure that an event’s potential contribution in terms of community cohesiveness, economic benefits and social incentives are not outweighed by environmental and social costs (Gursoy et al., 2004).

Putting Local Food Systems in Place

The focus on place and the local can also be an important element in reinforcing the perception of the quality of produce from the region when being sold via more conventional means. Indeed, it is significant that even given the ethical trend in food retailing that the biggest sellers of ethical foods are supermarkets. With broad distribution networks, expansive retail presence and strong buying power, supermarket chains have become the primary retailers through which ethical products are sold (Corporate Watch, 2004; Fearne et al., 2005; Hughes et al., 2007). Therefore, food events, such as commercial fairs and trade expositions, can help promote local foods and products in order to enable their export out of the region. Indeed, even specialized artisan food and wines that are sold in specialized stores will usually utilize conventional food transport and distribution systems in order to reach the market, with some purchase of artisan foods by consumers also having been initiated as a result of consumers travelling as tourists (Hall and Mitchell, 2001, 2008; Hall et al., 2003).

A local food system refers to deliberate formed systems that are characterized by a close producer – consumer relationship within a designated place or local area. Local food systems support long-term connections; meet economic, social, health and environmental needs; link producers and markets via locally focused infrastructure; promote environmental health; and provide competitive advantage to local food businesses (Food System Economic Partnership, 2006; Buck et al., 2007). According to Anderson and Cook (2000, p. 237):

The major advantage of localizing food systems, underlying all other advantages, is that this process reworks power and knowledge relationships in food supply systems that have become distorted by increasing distance (physical, social, and metaphorical) between producers and consumers. … [and] gives priority to local and environmental integrity before corporate profit-making.

Buck et al. (2007) argue that the potential benefits of such a system include:

Elements of such an approach are well illustrated by Farmers’ Markets Ontario (FMO) (2007) on their web site:

Shopping at the Farmers’ Market is a healthy decision not only for you, but for your community’s economy as well. For every dollar spent at the market, another two dollars ripple through the provincial economy. In Ontario alone, sales at Farmers’ Markets total almost $600 million, leading to an economic impact of an astounding $1.8 billion.

For every one person you see working at the market, another two are busy at work back on the farm. As many as 27,000 people in Ontario are directly involved in preparing and selling the products you find at the market.

Furthermore, Farmers’ Markets are good for other businesses too. Studies show 60 to 70 percent of market-goers visit neighbouring businesses on their way to and from the market.

A concept closely related to the local food systems idea if that of the ‘foodshed’ which is associated to the bio-regionally oriented concept of the watershed (Kloppenburg et al., 1996; Feagan and Krug, 2004). Direct marketing via farmers’ markets and food festivals along with other forms of tourism are recognized as integral components of a foodshed. According to Feagan and Krug (2004) in order for a local foodshed to be established, several things need to happen:

Interestingly, the example used by Feagan and Krug (2004) of a foodshed was that of Niagara, which also shares the characteristics of successful local food systems identified by Buck et al. (2007): a major metropolitan area within close proximity to fertile farmland. Such a characteristic has also been identified as contributing to successful food tourism destinations (Hall et al., 2003) as well as farmers’ markets. Indeed, no matter how ‘alternative’ a food system may be, it cannot ignore the importance of connecting producers with consumers, and the larger the market of consumers, the easier it is to be successful.

Farmers’ markets and other community food events and festivals clearly serve an important role in local food systems. Lyson (2004) also described this as ‘civic agriculture’, a concept that emphasizes community economic development balanced against the social and environmental objectives of a community. With respect to farmers’ markets, Lyson comments that, ‘as social institutions and social organizations, farmers’ markets can be important components of civic agriculture. They embody what is unique and special about local communities and help to differentiate one community from another’ (2004, p. 93).

Farmers’ markets and other community based food events are therefore a very significant means to encourage entrepreneurship and business incubation within local food systems and therefore provide a basis for their organizational sustainability. Stalls at farmers’ markets may often represent a form of micro-entrepreneurship. In Hilchey et al.’s (1995) study of farmers’ markets in the US north-east, they noted that most vendors either did not have a business before they started selling at a farmers’ market, nor did they start on a small scale at their residence. Many vendors do not have the capital to open a retail outlet, or they perceived that they have few other marketing options available. They also found that farmers’ markets can help vendors hone their skills in areas such as business management, marketing, communication, leadership and entrepreneurship by helping the vendor, improve their understanding of consumer needs, self-confidence in merchandising, co-operating with others, advertising and customer relations, pricing and competing effectively, while also having positive effects on their families. Therefore, farmers’ markets can have an extremely important incubation function and provide a rich entrepreneurial environment for starting new businesses or products, or changing the direction of existing businesses (Hilchey et al., 1995). Some similar findings have also been reported in studies of farmers’ markets in Australia (Coster and Kennon, 2005) and New Zealand (Guthrie et al., 2006). Farmers’ markets can therefore help entrepreneurs overcome start-up barriers by:

Facilitating product development and diversification: Farmers’ markets provide a service to vendors in providing information on the likes and dislikes of consumers.

Creating opportunities to add value to products: Value is added to products through processing and/or through packaging, branding and labelling.

Enhancing the customer base: Markets provide vendors an opportunity to expand the size and diversity of their customer base because of a stable market for their products and increased awareness of their business.

Expanding sales and income: Markets provide vendors opportunities to earn extra income above and beyond that available through normal distribution channels and can help to enhance sales at other outlets.

Marketing is a critical element in the hosting and management of successful food events. To modify Kotler and Levy’s (1969) definition of marketing in food event terms: marketing is that function of food event management that can keep in touch with the event’s participants and consumers (including visitors), read their needs and motivations, develop products that meet these needs and build a communication programme which expresses the event’s and associated product’s purpose and objectives. Certainly, selling and influencing will be large components of food event marketing; but, properly seen, selling follows rather than precedes the event management’s desire to create experiences (products) which satisfy its consumers. Food events, such as farmers’ markets, work within local food systems because they are able to connect with the needs of consumers and other relevant stakeholders and actors within the system. As such, they may therefore have a range of benefits beyond that of immediate business and economic returns, although such returns may be substantial. For example, in the UK the National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association (FARMA, 2006) estimate that farmers’ markets are worth £220 million annually and estimate that some 10,000 farmers and producers participate annually in farmers’ markets. Results of FARMA supported research indicated that a group of five farmers’ markets in Gloucestershire/Wiltshire (112 market days) generated an estimated £2.8 million a year in turnover while a group of eight monthly farmers’ markets in Surrey (96 market days in total) generated an estimated £2.6 million a year (FARMA, 2006). The role of FARMA in encouraging farmers’ markets as an ‘alternative’ distribution and retail channel for farmers and producers is very clear given that their stated mandate is to champion local food ‘through helping to reconnect rural and urban communities, offering business support to emerging enterprises, and encouraging the revival of fresh and distinctive locally produced foods’ (FARMA, 2006, p. 2). Table 2.1 lists some of the elements of a successful farmers’ market as reported by the FMO.

Table 2.1 Characteristics of a community-driven, producer-based farmers’ market

• Home grown produce, home made crafts and value-added products, where the vendors are primary producers (including preserves, baked goods, meat, fish, dairy products, etc.).

• There is freshness, abundance, quality.

• Local, from the community, a cottage industry.

• Family oriented and a fun place.

• The producer is the vendor; proud of product; fully knowledgeable.

• The Market is dynamic, friendly, reflects community personality.

• Open-air, seasonal, during the local growing season, usually once or twice a week.

• Championed and supported and/or administered by a local community group.

• Provides opportunity for exchange of information and learning, i.e. building community alliances, good health, nutrition, use of products.

• Product presentation and service training are regularly provided for vendors.

• There is policy guidance for leaders and managers to assist them in working with various community groups in organizing significant events, festivals and other fund-raising efforts.

Source: Derived from Farmers Market Ontario (undated); also see Colihan and Chorney (2004).

Nevertheless, farmers’ markets may not always succeed or be appropriate to every producer or community’s circumstances (Stephenson et al., 2006). Hilchey et al. (1995) point out that:

Stephenson et al. (2006) note that research suggests that a little over 80% of US farmers’ markets may be regarded as self-sustaining or self-supporting. Yet that still leaves a significant number of markets that do not survive. Their study of farmers’ markets that had closed, suggested seven factors associated with failure, several of which mirror-wider research on business survivability (Hall and Williams, 2008):

A successful food event marketing plan focuses on the development of a marketing process which revolves around activities and decisions in three main areas (Hall and Mitchell, 2008):

No food event can be all things to all people. Thilmany’s (2005) guide for planning and developing a farmers’ market suggests, ‘learn about your customers using indicators such as income, population, success of markets in similar communities and assessing the competition to make sure there are not already too many markets operating in your community’ (p. 2). It is therefore essential that any business, community, destination or organization that is planning an event should incorporate an understanding of consumer behaviour into their marketing and promotional strategies. Most importantly, food events should ideally be held as part of a broader marketing strategy with respect to business, community and/or product development rather than being held for their own sake. An attractive market for a food event will be one in which:

Exhibit 2.1 Wallington Food and Craft Festival

This 2-day food fair is held each October in the grounds of Wallington, one of the National Trust’s finest properties in the North-East of England. This eighteenth century Palladian Mansion is set within a 13,000 acre site, which includes several tenant farms producing high-quality beef and lamb (National Trust, 2007a).

The border county of Northumberland, in which Wallington estate lies, is a land of contrasts. A stretch of wild, and mostly undiscovered, coastline rises inland to an area of high rugged moorland, and in the south of the county there is a softer area of rolling hills and pasture land. This varied topography has resulted in the development of a healthy farming and fishing community supplying some of the finest produce in the country. Northumberland is especially well known as a producer of fine salmon, kippers, meat and game.

The National Trust is a champion of local and seasonal food within the UK. Local food is listed as one of four key campaigns at present and information about their food and farming policies can be seen on their web site (National Trust, 2007b). A recent document produced for the North-East region of the National Trust states:

‘The National Trust would like to help ‘reconnect’ the food chain between producers and consumers. Our aim is to show consumers the benefits of local and seasonal food and share the joy it is to prepare and eat food that comes from a known source, and is healthy and tasty. At the same time, we want to see farmers rewarded for producing quality food whilst protecting and enhancing the countryside’ (Blaauboer, 2007a).

The introduction of Wallington Farm Shop, which was purpose built and opened in 2002, has been a positive move to achieving these aims. Much of the meat produced on the estate is distributed directly through the shop or visitor restaurant, and the use of the ‘Freedom Food’ label is a sure way of reassuring customers about the high standards of farming practice that is being maintained.

The unit also sells a range of seasonal vegetables, cheese, jams, chutneys, cakes and baked goods, all grown or produced in the locality.

The farm shop project also sits well with the National Trust’s effort to reduce their carbon footprint effect of food miles as part of their Carbon Footprint Project (Blaauboer, 2007b).

The development to hold a food festival was a logical next step for Wallington and in its first year, in 2006, the event attracted nearly 13,000 visitors. This figure was maintained in 2007, but interestingly the number of ‘non-members’ of the National Trust who attended this year rose from 2,000 to 5,000. This was significant for the organization as its message about local food reached out to a wider audience (Nicoll, 2007).

The event is a showcase for nearly 50 local food producers from the county of Northumberland and the neighbouring county of Cumbria, in the Lake District. The event also features stands selling local arts and crafts such as beeswax candles, jewellery and ceramics.

Jointly planned as a partnership between the National Trust and two regional food groups, Northumbria Larder (2007) and Made in Cumbria (2007) and supported by DEFRA, this event fits well with the National Trust’s local food strategy. As well as enjoying cookery demonstrations from several local food ‘celebrities’, the festival includes educational activities for both adults and children. This year cookery demonstrators included Terry Miller, winner of the ITV television show, Hell’s Kitchen and Nick Martin, a champion of local food from Cumbria.

Each new food event also needs to develop a market entry strategy. Although many food and wine events are constrained in terms of their location, especially community events that must, by definition, be based within the community, the timing of when an event is held will be crucial to its success in attracting visitors and attendees. The objectives which underlie an event are again crucial to decisions regarding the timing of holding an event. Where there is some flexibility in hosting an event, organizers should consider (a) what other events and competing attractions or activities the food event will be competing with and (b) especially in the case of events that are eternally oriented with respect to visitation, given the seasonality of visitation in a destination and of agricultural production, can the event be utilized to boost visitor arrivals in shoulder-season and off-peak periods or ‘down-times’ in growing produce? Stephenson et al. (2006) in their analysis of why farmers’ markets fail stress the importance of planning new markets carefully in order to ensure success – a recommendation that clearly applies to food events in general:

Market organizers should spend considerable time deciding whether and how to open a new market. Better planning and promotion before a new market is opened may help with some of the issues that arise during the first year of operation. An important part of the planning process is setting a goal for market size in general or a goal by year, so that cash flow can match the scale of the market and appropriate management tools can be provided. Planning for size is the first step in creating a viable organization that will endure challenges and conflicts that occur with growth (Stephenson et al., 2006, p.19).

The Marketing Mix

The design of an appropriate marketing strategy for an event consists of analysing market opportunities, identifying and targeting market segments, and developing an appropriate market mix for each segment. Key factors are identified below (Colihan and Chorney, 2004; Hall and Mitchell, 2008).

Product/Service Characteristics

Food and wine event management must understand the difference between the generic needs the event is serving and the specific products or services it is offering. In order to meet the demands of the marketplace, it is essential that organizers focus the food event product/s in light of the needs of specific market segments. Farmers’ markets also have to manage a complex relationship between vendors and consumers that is different than most conventional retail outlets. A viable farmers’ market must have enough farmer vendors to attract customers, and it must have enough customers to be attractive to farmer vendors and producers (Stephenson et al., 2006). Burns and Johnson (1996, p. 12) describe this situation:

Farmers’ markets, unlike retail stores, operate both on the supply side, with the farmers, and on the demand side, with the consumers. However, the overall retail marketing dynamic is operative. Consumers wish to have certain preconceptions met when selecting a retail site. If they are not met, the consumers will stop coming. Farmers will go to markets where they are guaranteed selling space and have exposure to enough customers to allow them to sell the majority of their product in an allotted time. When farmer … and customer expectations are not met, both farmers and customers will look for alternative markets.

Promotional Channels and Messages

Promotional programmes for even the most modest local farmers’ market or food and wine festival require exactly the same kind of organization, planning, allocation of responsibilities and attention to detail that larger more commercially oriented events require. In promoting events to the market various communication methods are used, including advertising, personal selling, sales promotion and publicity. Promotional methods should be selected on the basis of their capacity to achieve the objectives of the event with respect to target audience and their relative cost.

Price

Although many food events are ‘free’ in terms of entry costs to participants and visitors, particularly community events, the issues of price are significant at all levels of event management and marketing. Prices may cover costs, maximize profits, subsidize all participants or certain market segments, encourage competition or result in unanticipated consumer reaction. Prices should be set according to a wide range of factors including past history, general economic conditions, ability to pay, revenue potential, costs, level of sponsorship and the competition. Pricing may even be used as a mechanism to appeal to particular markets. Affordability, for example, is of substantial importance in appealing to lower-income groups who may be the target of some urban farmers’ markets. Fisher (1999) provided some general recommendations concerning the development and operation of farmers’ markets in low-income areas.

Fisher noted that while low-income consumers face many of the same challenges as middle-income consumers concerning a diet based on healthful and nutritious foods, there are also many unique barriers. For example, low-income consumers may be more price-sensitive or have food access issues such as no transportation or grocery store in their neighbourhood. Fisher (1999) outlined five specific guidelines for successful low-income market operations including:

Place and Methods of Distribution

Despite the ‘fixed’ nature of the majority of food events in the sense that they occur at a specific location, distribution issues are also of significance to organizers. As noted above, the time and place in which food events are held will be a major factor in determining the event’s success as well as having potential implications for branding and identity. According to Thilmany (2005, p. 3):

The market should be easy to find, and centrally located, with adequate parking for farmers/vendors and customers. You should realize that most vendors want to drive into their stall to forego the unloading/loading time they would spend setting up a stand-alone display. Consider partnering with a business or area of town that is trying to redevelop or redefine itself as a pedestrian friendly area that is a social hub of the community … they often will help establish markets.

Time and place are actually questions about the most appropriate manner in which to ‘distribute’ the event product to its current and potential market. As markets increase in size, they draw both vendors and customers from a larger geographical area. As Burns and Johnson (1996, p. 16) observed, ‘it appears that as the size of the market increases, the market becomes more attractive to farmers from a wider geographical area and the retail (customer) trading area also increases. This clearly has implications for smaller markets. ‘As larger markets draw farmers from a larger area, this process may also draw farmers away from markets they perceive as less profitable’ (Stephenson et al., 2006). Furthermore, issues of distribution will be tied up in the promotion of events. For instance, given a limited budget how can event organizers best distribute promotional materials to the market that they have identified?

Packaging and Programming

Packaging is the combination of related and complimentary services in a single-price offering. For larger food and wine festivals packages may consist of a selection of sub-events being sold together or the event plus transportation. Programming is the variation of service or product in order to increase customer spending and/or satisfaction, or to give extra appeal to an event or package. For example, many wine festivals have a programme of different activities and tasting which are timed to follow and interrelate with each other over the various days on which the festival is held (Hall and Mitchell, 2008). Even many farmers’ markets also include other elements than just stalls selling produce, such as music and entertainment or face painting for children (see Chapter 13). The specific mix of activities which are developed with the overall event framework may have the capacity to extend the interest of certain markets and hence, potentially, increase their level of satisfaction. Programming should consider such factors as the event venue and location, inclement weather options if part of the event is to be staged outside, which is especially important in the case of outdoor farmers’ markets, and the needs of different target markets, and their relative availability to attend (e.g. if a farmers’ market is appealing to a domestic market and is held during the week, some potential target markets may not be able to attend during the day because of work commitments), and balance within the choice of activities.

Partnership

Collaboration is a very important part of food and wine event marketing management, in community terms with a wide range of institutions and stakeholders; and in commercial terms with respect to bringing together the various sectors of the food sector as well as the needs of public and/or private sponsors. In their review of farmers’ markets fail, Stephenson et al. (2006) noted the importance of ensuring that some smaller markets and those at the start-up phase had community financial support, noting that ‘farmers’ markets are an important part of a local economy and enhance the quality of community life. There is justification for government and economic development sector support.

Sponsorship and support may come in many forms: financial assistance, facilities, provision of event infrastructure or space, management skills, labour and, of course, donations of produce. Sponsors see events as a means of raising profile, promoting particular products through enhanced profile and image, obtaining lower costs per impression than those achieved by advertising, improve sales, and in being seen as good corporate citizens. Nevertheless, from the perspective of food event organization and the host community it is essential that the potential sponsor be appropriate to the objectives, needs and image of the event.

In many jurisdictions, government agencies and/or local government are significant sponsors of farmers’ markets as well as other food events such as festivals. A number of different areas have been identified in the literature (e.g. Hilchey et al., 1995; Colihan and Chorney, 2004; Thilmany, 2005) where government agencies could provide support, especially with respect to farmers markets where particular planning and health regulations may need to be addressed (see also Chapter 13) (Table 2.2). Indeed, it is significant to note that Stephenson et al. (2006) concluded their report on why farmer’s markets fail by noting:

Table 2.2 Areas of potential support and assistance for farmers’ markets by government agencies

| Area | Forms of potential support and assistance |

| Finance | • Raising funds for facilities and promotion. |

• Providing appropriate and adequate liability insurance coverage. | |

• Establishing a revolving loan fund for vendors that can provide growers with seasonal start-up funds, or that can help a food processor by needed equipment. The fund could be capitalized with support from larger businesses, local financial institutions and the vendors themselves. | |

| Education and training | • Linking educational and training opportunities in marketing, merchandising, market gardening, bookkeeping, food processing, state and local regulations, personnel management, and labor regulations. Many educational agencies can provide training support for farmers’ markets. |

• Training and professional development of market managers so they can further help the vendors as well as improve promotion and marketing. | |

• Identifying possible clients for more intensive support. | |

• Preparing manuals for new vendors. | |

| Facilities/organizational development | • Helping to secure a permanent farmers’ market location, or, if desired, a year-round facility. Dealing with planning and regulatory issues. |

• Helping to establish a certified inspected food processing centre where necessary for farmers’ market vendors. | |

• Helping to establish producer cooperatives as separate business entities that sell product surpluses wholesale to local restaurants, grocery stores and institutions. | |

| Regulatory Assistance | • Helping market managers and vendors stay abreast of legislation affecting them. |

• Working with local code enforcement, zoning, and planning agencies to ensure a safe and prosperous market. | |

| Public Relations and Networking | • Facilitating open and ongoing dialogues with local businesses to alleviate concerns about traffic congestion, parking problems, and competition. |

• Promoting inter-agency and governmental cooperation. |

Source: Derived from Hilchey et al. (1995); Abel et al. (1999); Colihan and Chorney (2004); Thilmany (2005); Stephenson et al. (2006).

Access to financial and other resources is a national policy-related issue with significant impacts on farmers’ markets, particularly small markets. Small markets are expected to be self-sustaining, while other publicly delivered services do not have a similar expectation. Public funds support services that enhance the global trade of food products, but a similar level of support is not made available to support local agricultural markets. This is a political decision (Stephenson et al., 2006, p. 20).

However, collaboration and the development of strong positive networks are not always easy and significant barriers may exist including:

The further development of social capital through the creation of networks is extremely important in terms of its capacity to reduce the level of uncertainty for entrepreneurs in the creation of new businesses. Network-based relationships can provide entrepreneurs with critical information, knowledge and resources. Social and intellectual capital, including access to prior experience, can therefore be used to maximize the scarce capital available to some small food and wine businesses and associated events.

The long-term benefits of network relationships remain an interesting question for small wine and food tourism businesses. Venkataraman and Van de Ven (1998) argue that it only makes sense to leverage social capital in the early stages of a new venture. According to their research, as ventures progress businesses base their decisions on economic criteria, and social capital has less impact. Ironically, this means that the very network relationships that help to reduce risk and uncertainty in small business start-ups fade in importance when uncertainty becomes less. Such an interpretation may mean that the importance of social ties may therefore be a function of the level of uncertainty facing a small business entrepreneur. Yet, the application of this to the food and wine tourism sphere may be problematic, given the importance of regional brands as a means not only of destination promotion, but also of place and product differentiation (Hall, 2004).

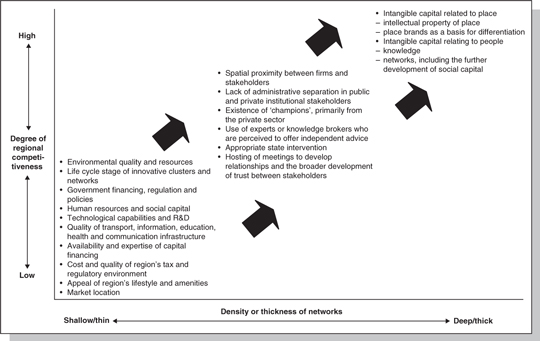

Arguably, once the geographical designation is established and accepted in the market (e.g. appellations such as Champagne, Burgundy or Napa Valley), it then becomes extremely difficult for ventures to withdraw from networks which support the place – brand as it would potentially mean the loss of significant intangible capital and a direct economic resource. This observation may have substantial implications for the longevity and success of place and brand-oriented clusters and networks. Once place–brands have established their presence in the market, they not only contribute to the success of collective and individual businesses, but they also contribute to the development of further social capital because they become integral to the identity of place and the firms and individuals within it (Figure 2.3). This iterative and recursive process does not mean that such collaborative partnerships and networks as embodied in local food systems have an infinite lifespan, nor does it mean that wine and food regions and food systems automatically shift in building-block fashion and then form a dense network set of social, economic and intangible capital which comes to be deeply embedded in the sense of place and cultural capital. However, the particular congruence of intangible capital to be found within the food, wine and tourism industries and its maintenance through events, such as farmers’ markets and food festivals, does potentially lead to longer business life cycles and the associated longer-term maintenance of social networks and capital (Hall, 2004).

Figure 2.3

Ideal pathway for the increasing connectedness and competitiveness of local food networks and systems (after Hall, 2004)

Conclusions

This chapter has discussed event market and management within the context of local food systems or foodsheds. However, it has stressed that such systems do not just develop automatically, as an appropriate match, still has to be found between products and consumers, nor do they imply isolation from the broader marketplace. In fact, appropriate localization may well be an appropriate strategy with which to contend with some of the undesirable effects of globalization on place and on food systems in particular. Globalization is therefore a two-edged sword and can be recognized as potentially offering benefits for producers as well as the likelihood of increased competition.

The chapter has also highlighted, how local food systems and the food events within them still require good planning, marketing and management in order for them to thrive. Although often described as part of ‘alternative’ (e.g. Food System Economic Partnership, 2006) food systems, the business and organizational requirements of members of such systems are the same as those of any other system. For example, farmers’ markets serve pivotal roles for small farmers and local food systems. However, ‘the success of each is closely tied to the other. Knowledge of market failure and how it occurs is an important step in improving the viability of farmers’ markets and therefore, maintaining and expanding a marketing channel for small farmers, and enhancing community food systems’ (Stephenson et al., 2006, p. 2). This chapter has provided some initial insights into some of the ways that such market issues may be addressed and the need for clear planning strategies. Most important of which is to regard markets and other events as part of the overall strategy of a business or a community, rather than seeing them as ends in their own right.

References

Abel, J., Thomson, J. and Maretzki, A. (1999). Extension’s role with farmers’ markets: Working with farmers, consumers, and communities’. Journal of Extension, 37(5). http://joe.org/joe/1999october/a4.html

Anderson, M.D. and Cook, J.T. (2000). Does food security require local food systems?. In Harris, J.M. (ed.) Rethinking Sustainability: Power, Knowledge and Institutions. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Blaauboer (2007a). Have a bite! Policy document produced to promote local food in the Yorkshire and North East region, National Trust.

Blaauboer (2007b). Personal discussion with Marianne Blaauboer, Policy Manager for Yorkshire and the North East, National Trust.

Brown, M.D., Var, T. and Lee, S. (2002). Messina Hof Wine and Jazz Festival: An economic impact analysis. Tourism Economics, 8(3), 273–279.

Brown, O. (2005). Supermarket Buying Power, Global Commodity Chains and Smallholder Farmers in the Developing World. United Nations, New York.

Buck, K., Kaminski, L.E., Stockmann, D.P. and Vail, A.J. (2007). Investigating Opportunities to Strengthen the Local Food System in Southeastern Michigan, Executive Summary. University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment.

Burns, A.F. and Johnson, D.N. (1996). Farmers’ Market Survey Report. US Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Marketing Service, Transportation and Marketing Division, Wholesale and Alternative Markets Program, Washington, DC.

Clarke, I. (2000). Retail power, competition and local consumer choice in the UK grocery sector. European Journal of Marketing, 34(8), 975–1002.

Colihan, M.A. and Chorney, R.T. (2004). Sharing the Harvest: How to Build Farmers’ Markets and How Farmers’ Markets Build Community! Farmers’ Markets Ontario, Brighton.

Coster, M. and Kennon, N. (2005). ‘New Generation’ Farmers’ Markets in Rural Communities. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Barton.

Farmers’ Markets Ontario (2007). About us, http://www.farmersmarketsontario.com/AboutUs.cfm

Farmers Market Ontario (undated). Characteristics of a Community-Driven, Producer-Based Farmers’ Market. “The Model Farmers’ Market” (poster). Farmers’ Market Ontario, Brighton.

Feagan, R. Krug, K. (2004). Towards a sustainable Niagara foodshed: Learning from experience. In Leading Edge 2004. The Working Biosphere, March 3–5, Niagara Escarpment Commission.

Fearne, A., Duffy, R. and Hornibrook, S. (2005). Justice in UK supermarket buyer-supplier relationships: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 33(8), 570–582.

Fisher, A. (1999). Hot Peppers and Parking Lot Peaches: Evaluating Farmers’ Markets in Low Income Communities. Community Food Coalition, Venice, CA.

Food System Economic Partnership (2006). Alternative Regional Food System Models: Successes and Lessons Learned: A Preliminary Literature Review. Food System Economic Partnership, Michigan.

Friends of the Earth (2003). Supermarkets or Corporate Bullies? Friends of the Earth, London.

Gursoy, D., Kim, K.M. and Uysal, M. (2004). Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: An extension and validation. Tourism Management, 25(2), 171–181.

Guthrie, J., Guthrie, A., Lawson, R. and Cameron, A. (2006). Farmers’ markets: The small business counter-revolution in food production and retailing. British Food Journal, 108(7), 560–573.

Hall, C.M. (2004). Small firms and wine and food tourism in New Zealand: Issues of, clusters and lifestyles collaboration. In Thomas, R. (ed.) Small Firms in Tourism: International Perspective. Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 167–181.

Hall, C.M. and Mitchell, R. (2001). Wine and food tourism. In Douglas, N., Douglas, N. and Derrett, R. (eds.) Special Interest Tourism: Context and Cases. John Wiley & Sons, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 307–329.

Hall, C.M. and Mitchell, R. (2008). Wine Marketing: A Practical Approach. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Hall, C.M., Mitchell, R. and Sharples, E. (2003). Consuming places: The role of food, wine and tourism in regional development. In Hall, C.M., Sharples, E., Mitchell, R., Cambourne, B. and Macionis, N. (eds.) Food Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 25–59.

Hall, C.M. and Williams, A. (2008). Innovation and Tourism. Routledge, London.

Hilchey, D., Lyson, T. and Gillespie, G. (1995). Farmers’ Markets and Rural Economic Development: Entrepreneurship, Small Business Creation and Job Creation in the Rural Northeast. Farming Alternatives Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Hughes, A., Buttle, M. and Wrigley, N. (2007). Organisational geographies of corporate responsibility: A UK – US comparison of retailers’ ethical trading initiatives. Journal of Economic Geography, 7, 491–513.

Kloppenburg, J., Hendrickson, J. and Stevenson, G. (1996). Coming into the foodshed. Agriculture and Human Values, 13, 23–32.

Kotler, P. and Levy, S.J. (1969). Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 33, 10–15.

Lyson, T.A. (2004). Civic Agriculture: Reconnecting Farm, Food, and Community. Tufts University Press, Medford, MA.

Made in Cumbria (2007) at http://madeincumbria.co.uk

Mowle, J. and Merrilees, B. (2005). A functional and symbolic perspective to branding Australian SME wineries. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 14(4), 220–227.

National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association (FARMA) (2006). Sector briefing: farmers markets in the UK; nine years and counting, Southampton (also downloadable from http://www.farma.org.uk/Docs/1/%20Sector/%20briefing/%20on/%20farmers’%20markets%20-%20.June06.%2006.pdf)

National Trust (2007a) at http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-vh/w-visits/w-findaplace/w-wallington

National Trust (2007b) at http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/main/w-cw/w-countryside_environment/w-food_farming.htm

Northumbria Larder (2007) at http://northumbria-larder.co.uk

Nicoll, P. (2007). Personal discussion with Paul Nicholl. Property Manager, Wallington.

Rayner, M. (2002). Product, price or principle? Ethical Consumer, 76, 32–34.

Retail World (2007). Consumers search for the ‘fresh factor’. Retail World Magazine, 60(April 16–27), 38–39.

Stephenson, G., Lev, L. and Brewer, L. (2006). When Things Don’t Work: Some Insights into Why Farmers’ Markets Close. Special Report 1073. Oregon State University Extension Service.

Tasslopoulos, D. and Haydam, N. (2006). A study of adventure tourism attendees at a wine tourism event: A qualitative and quantitative study of the Breedekloof Outdoor Festival, South Africa. In Carlsen, J. (ed.) World Wine and Travel Summit and Exhibition Academic Stream Proceedings, 13–17 November 2006, pp. 53–71.

Thilmany, D. (2005). Planning and Developing a Farmers Market: Marketing, Organizational and Regulatory Issues to Consider. Agribusiness marketing report. Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Cooperative Extension, Colorado State University, Fort Collins.

United Nations Development Programme (2005). International Cooperation at a Crossroads: Aid, Trade and Security in an Unequal World. United Nations, New York.

Venkataraman, S. and Van de Ven, A.H. (1998). ‘Hostile Environmental Jolts, Transaction set, and New Business’, Journal of Business Venturing, 13, pp. 231–255.