Chapter 13

The Authentic Market Experience of Farmers’ Markets

C. Michael Hall, Richard Mitchell, David Scott and Liz Sharples

Introduction

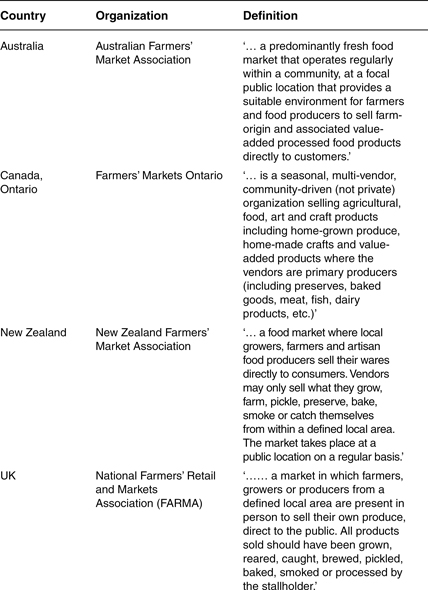

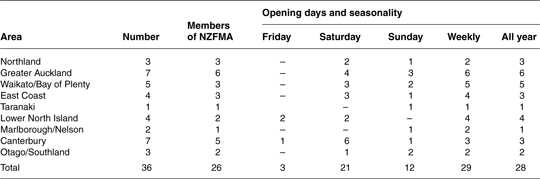

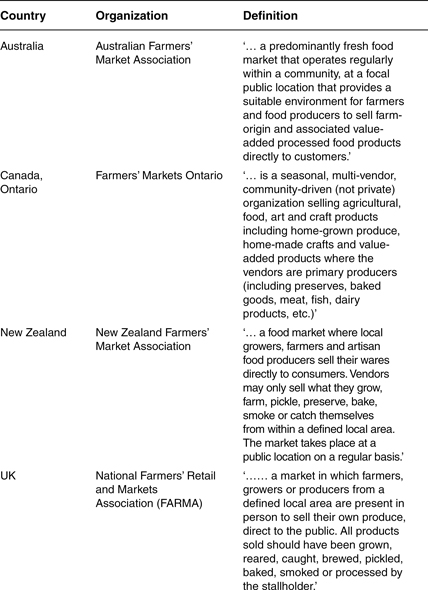

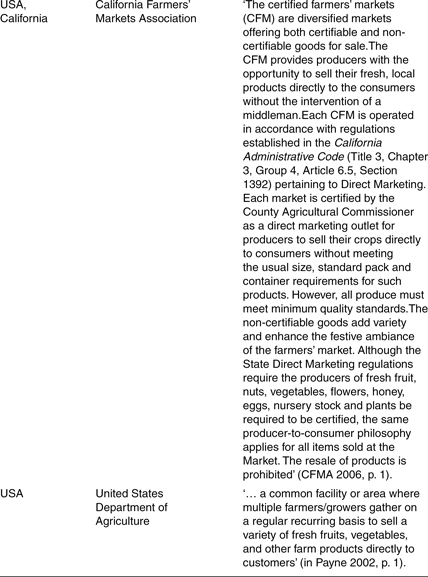

In a trend towards more ethical or morally acceptable consumption, consumers are increasingly demanding foods that are healthy, spray-free, organic, biodynamic, non-genetically modified organisms (GMO), have low food miles, are eth-ically produced, and/or fair-trade (McEachern and Willock, 2004; Padel and Foster, 2005). As Holloway and Kneafsey (2000, p. 290) put it, this ‘… is leading to an interest in foods which are not only felt to be safe, but which are traceable, and associated with ideas of sustainability and ecological-friendliness’. Meanwhile Sassatelli and Scott (2001) suggest that in responding to food crises, such as Genetically Modified foods or Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) outbreaks, ‘consumer-citizens’ may exercise their political muscle by changing their purchasing behaviour to distribution channels that they place more trust in. These constructs all require the consumer to be aware of the conditions under which food has been produced, who produced it and the trustworthiness of that producer. While Sassatelli and Scott (2001) suggest that the use of farmers’ markets as a source of ‘embodied trust’ is more likely to occur in traditional agricultural economies such as Italy, they acknowledge that this is increasingly the case in the industrialized corporate production systems like the UK, manifested in highly sophisticated agri-food systems. In fact, Holloway and Kneafsey (2000) suggest that farmers’ markets are a logical outcome of these trends as they represent the local and allow the consumer to connect directly with the producer of the food. This is reflected in definitions of several national and regional farmers’ market organizations (Table 13.1), where terms such as ‘local’, ‘fresh’ (which implies that food has only travelled a short distance from its origin), and ‘direct to consumer’ or terms that imply that the goods are vendor produced are frequently used.

Table 13.1 Definitions of farmers’ market

However, the definition of a farmers’ market has long been regarded as problematic. As Pyle (1971, p. 167) recognized, ‘… everything that is called a farmers’ market may not be one, and other names are given to meeting that have the form and function of a farmers’ market’. Other names for similar types of markets in the North American context include farm shops, swap meets, flea markets, tailgate markets and farm stands (Brown, 2001). As she explained this is a major problem in farmers’ market studies as many markets will advertise that they are a so-called farmers’ market when in fact they are technically not in the true sense of the term with respect to direct purchase in a market context of the grower of the produce purchased. Although to an extent the different terms used for farmers’ markets reflect retail change over time, the focus of ‘official’ definitions of farmers’ markets reflects the notion that farmers’ markets are ‘recurrent markets at fixed locations where farm products are sold by farmers themselves … at a true farmers’ market some, if not all, of the vendors must be producers who sell their own products’ (Brown, 2001, p. 658). The issue of definition is not just academic but, as discussed throughout this chapter, reflects broader concerns of consumers and producers that the farmers’ market and its produce be regarded as a space in which consumers can trust the ‘authentic’ qualities of what is being offered. We begin the chapter with a discussion of the antecedents of the modern farmers’ market movement as well as contemporary growth and development before introducing some recent conceptualizations of the markets from around the world.

The Fall and Rise of Farmers’ Markets

Markets of various kinds have been a part of most cultures for as long as trading economies have existed. Entire towns and cities grew to support the trading of food products, especially in strategic locations, such as at major sea ports, at the cross-roads of major trading routes or in areas with specialized production. Additionally markets have influenced both the growth and decline of urban areas throughout the ages. Devizes, a market town in Wiltshire, England, was developed as a direct result of the ‘hundreds’ market granted in the twelfth century to Potterne, approximately two miles away (Britnell, 1978). However, a degeneration of urban centres was seen between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries with the removal of royal charters from market towns, subsequently resulting in a migration to rural areas to enable access to sufficient foodstuffs (Dyer, 1991). During the industrial revolution the mass-urbanization of many western countries saw the development of urban markets that brought food from the rural hinterland to the population, while rural service towns also continued to hold regular markets. In America Hamilton (2002, p. 73–74) suggests that:

… in the mid-1700s, came a crucial shift. As urban areas flourished, consumer power grew exponentially, tipping the delicate balance of interdependence between customers and suppliers. Growth did cause an increased demand for food, creating more selling opportunities, but in these changing versions of the old markets, the customer became top priority.

Exhibit 13.1 Newcastle upon Tyne Farmers’ and Country Market

Newcastle is situated in the North East of England on the northern bank of the River Tyne and is England’s most northerly city, situated just 60 miles south of the Scottish border. This vibrant city has a history spanning back to Roman Times when the city was founded under the name Pons Aelius. The city itself is the 20th most populous in England with a population of 259,536 but it is part of the Tyne and Wear conurbation which is the fifth largest conurbation in England (British History Online, 2007).

By the Middle Ages Newcastle had become England’s northern fortress and was an important trading community and as early as Elizabethan times Newcastle was exporting coal. The tax from this trade brought great wealth to the city and by the nineteenth century Newcastle had also developed other industries such as shipbuilding and heavy engineering. During the Industrial Revolution the city was seen as a powerhouse of innovation and excellence.

Markets have always played an important part of Newcastle life and continue to do so. Records show that when King John made Newcastle a borough in 1216 there were already markets thriving in the town. Several historic maps, James Corbridge’s map of 1723, Charles Hutton’s map of 1770 and John Wood’s map of 1827 are helpful in recording the rise of fall of food markets in the city. We know, for example, that in 1723 a fish market, herb market, flesh market, milk and poultry market, groat market, wheat market and butcher bank were in existence (Newcastle upon Tyne City Council, 2007).

In the 1830s the heart of the city centre was developed in a neoclassical style largely by architects Richard Grainger and John Dobson. Many of these fine buildings and frontages have recently been restored and in 2005 Grey Street was voted to be England’s finest street in a survey of Radio 4 listeners.

A small portion of this area of the city, locally known as ‘Grainger Town’, was demolished in the 1960s to make way for a new shopping centre but many key buildings remain including the magnificent Grade 1 listed Grainger Market. This indoor market, which has a lettable area of 38,000 square feet, makes it one of the largest market halls in the country. At the time of its opening it was considered to be one of the most spacious and elegant markets in Europe and to mark its opening a grand dinner was held complete with an orchestra and attended by 2,000 guests (Newcastle upon Tyne City Council, 2007).

It was therefore fitting that Grainger Town, at the heart of Newcastle’s trading and commercial activity for many centuries, was chosen as the location for the development of Newcastle upon Tyne Farmers’ and Country Market. The market is held next to the 134 feet Roman Doric Column, Greys Monument, at the top of Grey Street, and a few steps away from the Grainger Market. This is an ideal location to catch passing trade as it is in the heart of the city centre and adjacent to a busy ‘metro’ station.

The market is promoted and organized by two full time employees who work for the markets team of the city council, who pay careful attention to maintaining the quality of the delivery. All potential stallholders are carefully vetted to ensure that they comply with the market’s high standards. This market is certified by National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association (FARMA) and therefore all food products sold on the market must be raised, grown or produced within a 50 mile radius of the market site. Occasionally producers from up to a 100 mile radius may be considered if there is no suitable application from a local producer of a given product. This allowance away from the usual ‘30 mile’ rule is due to the fact that Newcastle is a major city and the number of producers within the locality of the city is limited.

The number of stalls is strictly limited to 24 at the present time and there are no plans to grow the market as the council feel that this is an ideal size at this location. On one level the market team are in an enviable situation of being over-subscribed, with more producers wanting to take part than there are places available, but this does mean that sometimes hard decisions have to take place about stall allocation. The market team work hard to ensure that there is a balance of stalls on offer to customers and will actively seek out producers if they feel that the market would be enriched by their products (Blakemore, 2007). The market sometimes includes craft products which are produced locally but the main focus of the market is food.

The event is usually held on the first Friday of each month and at the current time there are no plans to hold the market more frequently. The team does however organize special market days, for example at Christmas, when the farmers’ market becomes part of a 4-day long Christmas market. This event will attract visitors from around the region including coach parties (Blakemore, 2007).

The future development of markets in and around Newcastle is still strictly governed by the city council who grants licences under the city’s historic charter regulations.

Liz Sharples

This shift in the nature of the relationship between consumer and producers was ultimately good for sales of produce, but bad for individual producer and this, plus the development of centralized market halls, made markets more profitable for middlemen than for producers of the goods (Hamilton, 2002). Over the ensuing 150 to 200 years, the development of mass communication, more efficient nationwide and global transport systems (e.g. rail, road, sea and air freight) and advances in the preservation of foodstuffs (e.g. canning, refrigeration, freezing, etc.) saw the development of state or regional distribution networks, then national markets in sprawling urban centres (Hamilton, 2002) and ultimately a global food market (Hall and Mitchell, 2001). According to Hamilton (2002, p. 74), despite some farmers’ markets in the USA continuing to be successful, ‘by the turn of the twentieth century … the bond between farmer and consumer had been replaced by the desire for almighty Convenience (sic.). The heyday was over’.

The advent of the supermarket during the twentieth century saw direct-to-consumer markets all but disappear. This was especially so in places such as the UK and USA, where the retail supermarket developed alongside the mallification of urban areas (Ghent Urban Studies Team, 1999), changes in agricultural production and distribution (Brown, 2001), the advent of the private motor vehicle (Hamilton, 2002) and extensive advertising and marketing of processed foods (Hamilton, 2002). It is interesting to note, however, that in Europe and many Asian countries, where large scale retail also developed throughout the twentieth century, food markets (admittedly many of which are not always purely direct-to-consumer markets) have managed to survive. France alone is estimated to have around 36,000 markets some of which do not fit the UK, US or Canadian definition of farmers’ markets but which nevertheless do contain local farmers and producers selling their own produce (FARMA, 2006).

As the twentieth century began to draw to a close, however, something triggered a resurgence of interest in farmers’ markets in the Anglophone world. It has been suggested this can be considered a response to what Beck (1992) considers ‘risk society’, that being the risks individuals perceive in contemporary society, including those discussed above. The (re)introduction of farmers’ markets was initially witnessed in the USA, then Canada, the UK and finally Australia and New Zealand. In the USA it has been suggested that the main growth period of modern farmers’ market came during the 1970s after 25 years of very low activity and this came on the back of changing attitudes by farmers to direct marketing and legislation that encouraged and enabled direct-to-consumer sales (i.e. Public Law 94-463, the Farmer-to-Consumer Direct Marketing Act of 1976) (Brown, 2001). Between 1970 and 1986 the number of US farmers’ markets is reported to have increased fivefold (Brown, 2001). According to Hamilton (2002, p. 77) ‘by 1994 there were 1,755 farmers’ markets nationwide, by 2000 there were 2,863’, while more recent figures also show rapid growth between 1994 and 2006 (United States Department of Agriculture, 2006) (Figure 13.1) and, if it were not for a lull in growth as a result of decreased funding for community initiatives during the Reagan administration (Brown, 2001), growth may well have been higher. However, the spatial distribution of farmers’ markets is not consistent as it should be noted that there are nearly 500 certified farmers’ markets (CFMs) in California alone (California Federation of Certified Farmers’ Markets, 2003).

Figure 13.1

Growth in American farmers’ markets (1970–2006) Note: No data is available for 1972, 1974, 1978, 1982, 1984, 1988 and 1992, but these years are included in order to show the exponential nature of the growth (Source: Brown, 2001; United States Department of Agriculture, 2006)

The Canadian experience generally mirrors that of the USA (see Jolliffe, Chapter 14). The farmers’ market revival began in the 1970s and 1980s. The number of markets in Ontario increased from a low of 60 in the 1980s to more than double that number in 2007. Farmers’ Markets Ontario (FMO), the umbrella organization for farmers’ markets in that province, was established in 1991 and in 2007 had 115 member markets.

In the UK the first of the modern farmers’ markets was (re)established in 1997 as a pilot project in Bath, which followed many of the elements of the most successful US markets (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000; Kneafsey et al., 2001). In 2002 there were 240 (Purvis, 2002) and by 2006 the number had risen to more than 550 markets and there were estimates that up to 800 markets would be sustainable throughout the UK (FARMA, 2006). Similarly, Australian and New Zealand markets were first established in the late 1990s and have grown to around 93 and 36 respectively in recent years (Melsen, 2004; Coster and Kennon, 2005; Guthrie et al., 2006; New Zealand Farmers’ Market Association (NZFMA), 2007; Regional Food Australia, 2007; see also Hede, Chapter, 16).

However, the definition of ‘farmers’ market’ also goes handin-hand with regulatory and environmental factors. For example, in California farmers’ markets are certified under state legislation. According to the California Federation of Certified Farmers’ Markets (2003) CFMs operated in accordance with regulations established in 1977 by the California Department of Food and Agriculture ‘are “the real thing”, places where genuine farmers sell their crops directly to the public’ and are regarded as having multiple benefits for small farmers, consumers and the community. Table 13.2 provides an outline of such benefits from the perspectives of CFM.

Table 13.2 Benefits of CFMs in California

| Stakeholder | Benefits |

| Communities | • Non-profit community service organizations which contribute to the social and economic welfare of the town or city they operate in. |

| • Produce a strong sense of community identity, bringing people from diverse ethnic and other backgrounds together. |

| • Serve to unite the urban and rural segments of the population. |

| • The meeting of farmers and consumers serves as an educational experience whereby customers learn about their food sources have access to nutritional information, engage in a multi-cultural experience and become aware of agricultural issues. |

| Consumers | • Fresh picked, vine and tree ripened quality. |

| • Cost savings that are possible because the direct sales by farmers to the consumer eliminate the cost of middleman marketing and other intermediaries. |

| Farmers | • Provide an outlet especially suited to moving smaller volumes of produce, thus creating a marketing channel outside of the traditional large volume distribution systems. |

| • Allows farmers to sell field run produce not restricted to pack and grade standards. This enables the farmer to sell tree ripened fruit which is too delicate for standard packing and shipping processes. |

| • Increases profits for farmers because of cost savings. |

A CFM is a location approved by the county agricultural commissioner where certified farmers offer for sale only those agricultural products they grow themselves. Not only does such an approach reinforce the local nature of what is available at a farmers’ market but it also provides a guarantee to customers that the food is direct from the producer rather than being repackaged. The concept of certifying farmers’ markets was also introduced in Ontario, Canada, in 2006 although through a process of self-regulation rather than government regulation.

The Ontario concept was developed by farmers in the Ontario Greenbelt and Greater Toronto area through the support of Farmers’ Markets Ontario (FMO), Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation (FGF) and Weston Farmers’ Market. The reason for the introduction of the scheme was that many farmers’ markets included non-farmers who resell produce bought at food terminals. The new CFM is instead dedicated to farmers selling locally grown products and excludes non-farmers reselling imports or produce bought from the Ontario Food Terminal. According to Laura Alderson, Manager of Weston Farmers’ Market in Toronto,

There is a growing sense among farmers that present-day Farmers’ Markets are a distortion of their origins … Many markets utilize public space, such as civic squares, and therefore should benefit the public interest. They can do this by delivering fresh, nutritious foods, building a sense of community between rural and urban neighbours, and investing in the local economy (FGF, 2006).

Similarly, Robert Chorney, Executive Director of FMO stated,

Farmers’ markets should benefit the farmer by selling the freshest food in return for taking home a greater share of the dollar for what they grow. Instead, there are resellers at many Ontario farmers’ markets with some simply mimicking large grocery retailers… This will be the first market in Canada that gives consumers a guarantee that the vendors are farmers and the food is fresh (FGF, 2006).

Such a perspective was also forcibly pushed by FMO in their set of rules and regulations for CFMs in Ontario.

During the summer of 2006, it became very clear to …FMO … that something needed to be done to combat the growing number of resellers or hucksters that had infiltrated and in some cases, were dominating, some of the markets in the Greater Toronto area. Farmers were being literally squeezed out of existing markets by resellers who continued to glut the market with food terminal sell-offs and in some cases, told there was no room for them to sell at market. Recognizing that most market operators would not soon purge their markets of resellers, hucksters and ‘produce-jockeys’, FMO studied the Greenmarket program in New York City and the State of California Certification program where all farmers are certified and where all vendors at market are ‘the real thing’ (FMO, 2007a,b, p.1).

Under the project certification includes, but is not limited to, each farmer undergoing a third-party certification inspection, showing proof of a farm business registration number, and posting a sign at each market stall to identify the location of their farm and what they grow (FMO, 2007a,b). The FMO have a zero tolerance for the reselling of products that have not been grown by the vendor.

All Ontario bona fide, conventional and organic growers and producers may apply for certification and, as part of the initial application, all prospective vendors are required to submit a full list of the produce/products to be sold and indicate when these items will be available for market. Table 13.3 outlines the various product categories of Ontario CFMs. The FMO (2007a,b, p. 3) notes that ‘as a general rule, a first-come-first-served process will apply; however, preference will be given to those farmers residing and operating within the Greenbelt’. In addition, the FMO also reserve the right to choose market vendors based on the overall product mix available at the market and note that not all applicants are necessarily accepted. The first two Ontario CFMs opened in May and June 2007 respectively at Toronto’s Liberty Village and Woodbine Centre using the label of ‘MyMarket Certified Local Farmers’ Market’ (MyMarket, 2007):

Table 13.3 Product categories of the Ontario CFMs

| Primary products | Fresh/unprocessed fruit, vegetables, cut flowers, plants and nuts; honey and maple syrup; shell eggs; meat (fresh and frozen); fish (fresh and frozen); herbs; mushrooms. |

| Secondary products must meet three conditions | • The ‘defining ingredient’ must be from (produced on) the farmer’s own far |

| • The value must be added from the farm (meat products may be an exception as the value might be added at an off-farm site) |

| • The product must be in compliance with all regulations and there must be evidence of appropriate inspection (by health and/or other authorities) |

| Ready-to-eat ‘fast food’; Permissible depending on agreement with host partners | • Coffee and tea sold by the market or a concession for community fund-raising obtained on a wholesale basis from an established business |

| • Unique sandwiches such as venison on a bun provided that the principal ingredient (i.e. the venison) conforms to the requirements of secondary products |

In the UK three core principles have been developed with respect to farmers’ markets which have been enshrined in a certification scheme administered by the FARMA and independently inspected.

- The stallholder comes from an area defined as local, 30 miles is suggested as the first mark, extending to 50 miles for urban and coastal locations.

- The stallholder has grown, reared, baked, brewed, caught, pickled or preserved the foods he/she is selling.

- The stall is staffed by the farmer or members of his/her team that knows about the production process.

The different sets of regulations highlights the difficulties in making international comparisons between farmers’ markets although the California, Ontario and UK approach towards certification highlights the significance of being able to ensure, from the perspective of consumer confidence, that a farmers’ market is actually a market in which produce is made available from those who actually farmed it. Indeed, if the UK approach was applied to Australian or New Zealand farmers’ markets then at many markets there would be stallholders who would not qualify and for whom the market is an alternative retail channel, albeit often of high-quality produce, rather than an example of ‘local food’. For example, in New Zealand Havoc Farm Pork from Waimate in South Canterbury was at one time simultaneously available at farmers’ markets in Dunedin and Christchurch – both well over 100 miles from the farm.

However, in some locations, including Ontario, it can be extremely difficult for a stallholder to be able to provide farm grown produce all year round as well as providing an environment that is comfortable for consumers. For example, the farmers’ market in Umeå in northern Sweden can only operate from late August to early October at the very latest because of weather restrictions on product availability and consumer comfort. Therefore, many farmers’ markets are quite seasonal, typically the harvest months of summer and autumn, not only with respect to the range of produce that is available, but also the number of stallholders. Although from some perspectives this may be regarded as a source of delight with respect to the authenticity of seasonal local food it can also pose significant business challenges for individual stallholders as well as the market as a whole.

One solution to the problem of seasonality is to have a permanent market, often indoors or at least sheltered, that combines elements of a farmers’ market as well as reselling. Such a category is recognized by the FMO under the category of a ‘Public Market’, defined as ‘usually a municipally owned/operated (not private) year-round operation consisting of unique, specialty food and crafts merchants who sell some products they produce or grow themselves but who often sell items they buy from local producers or wholesalers. Public Markets usually include local producers during the growing season’ (FMO, 2007a). Nevertheless, the lack of year-round availability may mean that other food retailers, such as supermarkets, may seek to provide substitutes for consumer demand for ethically or sustainably produced food, while in some cases – as in high latitude or altitude locations – to limit to fresh and locally farmed produce at some times of year would not only be almost impossible may be substantially restrict consumers’ diets.

The Farmers’ Market

Despite their growing significance as a retail outlet and visitor attraction there is relatively little knowledge of the market for farmers’ markets, with research dominated by North American studies. In the USA, demographic surveys at farmers’ markets have historically indicated that patrons are predominantly white females with above average incomes, age and education (Connell et al., 1986; Rhodus et al., 1994; Eastwood et al., 1995; Hughes and Mattson, 1995; Leones, 1995; Leones et al., 1995; Abel et al., 1999; Govindasamy et al., 2002; Conrey et al., 2003). That the majority of patrons to American farmers’ markets are women should not be surprising. Women still make the bulk of all food purchases in the USA. ‘A full 86% of the produce buyers surveyed for The Packer Fresh Trends edition were women. Women are more sensitive to price than men and are more likely to try new or unusual fruits and vegetables. The percentage of women making purchasing decisions in households with children under 18 is a whopping 99%’ (Leones, 1995, p. 1). However, interestingly, she went on to note that because visits to farmers’ markets tend to be more family oriented so other members of the family tend to take a more active role in purchasing decisions.

In their study of the Orono farmers’ market, Kezis et al. (1998) found that quality, support for local farmers, and atmosphere were very significant to consumers. Nearly half of weekly patrons reported spending upwards of US$10.00 per visit. Consumers also indicated a willingness to pay more for produce at the farmers’ market than for similar produce at a supermarket, with 72 per cent indicating a willingness to pay an average of 17 per cent more for farmers’ market produce. Similar data regarding consumer perceptions of farmers’ markets was also identified in a study conducted of farmer markets in San Diego California (Jolly, 1999). In the same study approximately equal proportions of the sample perceived prices to be higher or lower than supermarket prices. However, 73 per cent perceived quality at the farmers’ markets to be superior to supermarket produce. Two-thirds of the respondents also indicated a preference to have items indicate a San Diego grown label and a half stated a willingness to pay more for San Diego grown products (Jolly, 1999).

As in California, the state of Oregon has also embraced the farmers’ markets concept. A study of 2,714 consumers at the Albany and Corvallis Saturday farmers’ markets and the Wednesday farmers’ market in Corvallis indicated the significant economic impacts that farmers’ markets may have on a community (Novak, 1998):

- Consumers at the markets bought goods from three to six vendors.

- Consumers spent an average of US$12 to US$15 a visit, with the amount increasing as more seasonal produce became available.

- Shoppers to the Wednesday market spent 30 per cent more than Saturday shoppers, with women and retired people forming a significant portion of the visitors.

- 88 per cent of the visitors to the Albany Saturday market and 78 per cent of the visitors to the Saturday market in Corvallis said their main reason for going downtown that morning was the farmers’ market.

- 63 per cent of the Corvallis shoppers and 35 per cent of the Albany shoppers said they also planned to spend money at other downtown shops or restaurants after their market visit.

- 10 per cent of those who responded said they stopped shopping because they could not carry any more goods.

- The three markets attracted about 4,500 adults during an average week, even though they were open for only 13 hours during that time.

Given the growth of farmers’ markets in the USA, particularly in urban districts, there is also increased interest in making fresh farmers’ market produce available to working class and low-income neighbourhoods (Balsam et al., 1994; Brown, 2002; United States Department of Agriculture, 2002; Conrey et al., 2003) (see also Chapters 1 and 2). Suarez-Balcazar et al. (2006) undertook a study of a farmers’ market run in a low-income neighbourhood of Chicago that primarily had an Afro-American population. At the time of the study it was reported that there were more liquor stores than supermarkets available in this area while the available food in the community was sold, for the most part, at high prices by small stores with a limited selection of poor-quality food with low nutritional content. According to the majority of shoppers, the top three things that they liked best about the farmers’ market were the fresh produce, the reasonable prices and the cleanliness of the market. Most shoppers attending the farmers’ market were looking for vegetables (e.g. greens and okra) and fruits (e.g. apples, peaches and plums). Respondents reported that, in order to improve the farmers’ market, they would like to see more vendors and a greater variety of produce and other food products. Almost 100 per cent of the respondents would recommend the farmers’ market to a friend, and 95 per cent would return to the market again (Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2006). The research found that

- Residents were more satisfied, overall, with the access to fresh fruits and vegetables provided by the summer farmers’ market than they were with the access, quality, variety and prices of products available to them year round through local stores. The same results were replicated at a nearby community.

- Consumers at the market spent about $10 to $20 each week.

- The majority of consumers at the farmers’ market consisted of females between the ages of 40 and 75 years (Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2006).

Canada

The positioning of Canada’s farmers’ markets means that consumers have many of the same characteristics of those in the USA and the UK (see Jolliffe, Chapter 14). Feagan et al.’s (2004) study of Niagara region farmers’ markets reported that the modes of the ages for markets in St. Catharines and Port Colborne, and the overall survey were in the 60 to 69 years old age category while the less pronounced modal age for the Welland farmers’ market was in the 50 to 59 years old category. This same age trend has been noted in the UK by Holloway and Kneafsey (2000), and by Griffin and Frongillo (2003) in upper New York State farmers’ markets. Feagan et al. (2004) note that the age profile of their market respondents may be reflective of the proximity of the markets to areas that have a disproportionate number of older residents, and/or the greater availability of free time for this cohort or differences in this group’s underlying attitudes. However, they also acknowledge, along with Griffin and Frongillo (2003), that the age of the primary cohort of consumers may affect the long-term prospects of some markets.

A telephone survey of the shopping behaviour of 1,000 Ontario households undertaken by the FGF in 2007 gives a valuable profile of the Ontario market. Although supermarkets dominate 17 per cent of those surveyed shop weekly at farmers’ markets, with a further 57 per cent shopping there at least periodically. Two-thirds (65 per cent) of those who buy locally grown foods say they buy them supermarkets with a further 42 per cent buying them from farmers’ markets. Women are more likely to purchase from farmers’ markets than men (46 per cent of female respondents against 36 per cent of male) and are more likely to say it is very important to them that all of the food at farmers’ markets are locally grown (60 per cent). In terms of level of education those with post-graduate qualifications are more likely to purchase from farmers’ markets (FGF, 2007). The local food and experiential dimensions of farmers’ markets are also significant:

- More than half (55 per cent) of respondents stated that it is very important to them that at farmers’ markets, all of the food sold is locally grown. A further 31 per cent say it is somewhat important.

- Getting to meet and talk with the farmers is very important to 25 per cent, and somewhat important to 38 per cent.

- The opportunity to enjoy the social experience of chatting with neighbours while shopping at farmers’ markets is very important to 23 per cent, and somewhat important to 34 per cent.

- 18 per cent of respondents felt that it was very important that the farmers’ market was an interesting place with activities such as music and children’s events and 31 per cent felt that it was somewhat important.

- Smaller proportions of respondents state that it is very important that there are prepared foods available and ready to eat (16 per cent) and that there is a variety of products, including fruits and vegetables not grown in Ontario (18 per cent). Those aged 18–29 years are less likely to say it is very important that all of the food is locally grown (48 per cent), that they get a chance to meet and talk with the farmers (15 per cent), or that there are prepared foods available and ready to eat (12 per cent). Those aged fifty plus years give a higher level of importance to the produce being locally grown and the prospects of meeting the farmers (FGF, 2007).

The UK

Research by then UK National Association of Farmers’ Markets suggested that the typical farmers’ market customer falls into the AB (upper/middle class) or C1 (lower middle class) socio-economic group – working people with high disposable incomes, ‘the kind who know a good cut of Dexter beef when they see one’ (Purvis, 2002). Research by Archer et al. (2003) on latent consumers’ attitudes to farmers’ markets in North West England suggested that the majority of consumers were female (69 per cent), over 55 and retired. However, the age range was significantly lower in city centres (36–45). The majority travelled up to 10 miles and spent an average of £3 to £10. Consumers’ perception of farmers’ markets was that they ‘sell fresh, quality, tasty, local produce, but that the food would not necessarily be cheaper. Consumers also enjoyed the atmosphere of the farmers’ markets, supporting local producers and sampling food before purchasing’ (Archer et al., 2003, p. 488). An indication of the positive reaction to the farmers’ markets was that 93 per cent of those who had been to a market stated that they would return again.

A national survey of 2,025 adult consumers in the UK undertaken in June 2004 on behalf of FARMA also indicated a positive attitude towards farmers’ markets. Although supermarkets dominate food shopping, results indicated that 12 per cent of households shop from farmers’ markets. If this was translated to the national population this would represent a figure of 2.5 million households. Overall, 71 per cent of respondents stated they would buy from farmers’ markets if they could. More than half (54 per cent) also indicated that they were aware of farmers’ markets in their area with women slightly more aware than men. Thirty per cent of households indicated that they had visited or bought from farmers’ markets in the previous 12 months although by region this figure was lowest in Scotland where 26 per cent had visited or bought from a farmers’ market. Coincidentally this was also the region with the lowest interest in farmers’ markets (63 per cent). In comparison the South of England region had the highest level of interest at 76 per cent (FARMA, 2004).

Farmers’ Markets in New Zealand

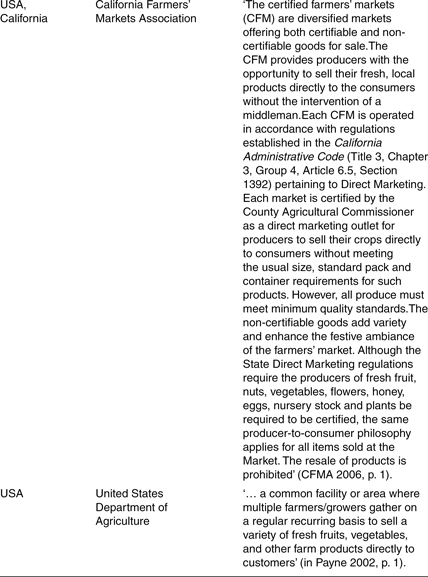

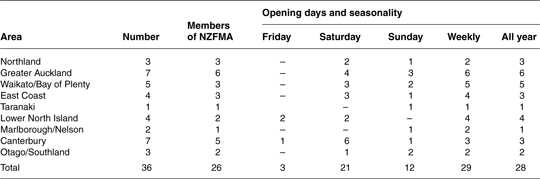

Despite there being no tradition of farmers’ markets in New Zealand (although there were markets of sorts in the early days of the colony, as is evident by the number of dormant ‘market reserves’ still present in many New Zealand towns and cities), the rapid recent growth and establishment of a farmers’ markets association in New Zealand indicates the potential for farmers’ markets in what is still primarily an agricultural economy. The first modern market was established at Whangarei in 1998 (Guthrie et al., 2006). As of late 2007 there were 36 farmers’ markets listed by the Farmers’ Market New Zealand Association (FMNZA), itself established in 2005, as either being open or about to open (Table 13.4).

The FMNZA has the following aims:

- To facilitate the formation of a network of authentic farmers’ markets throughout New Zealand.

- To clearly define the concept of an authentic farmers’ market and facilitate the development of this model in the cities and provinces of New Zealand.

- To support the viable and self-sufficient operation of existing and future farmers’ markets by sharing information and providing appropriate resources.

- To protect brand’ farmers’ market’, clearly distinguishing the concept of a farmers’ market from other markets, both retail and wholesale.

- To advocate on behalf of members at a national level. http://www.farmersmarket.org.nz/home.htm

An authentic farmers’ market is defined by the FMNZA as a market that has at least 80 per cent local produce stalls. Local means from within the regional boundaries established by individual farmers’ markets. Produce stalls can refer to farmer/grower stalls or ones that have a value-added product. Individual farmers’ markets also decide whether other stalls that sell food or farm origin products, e.g. coffee and bread, should be allowed a place in the market.

The relative maturity of the farmers’ market scene in New Zealand is also evident in growing cooperation between markets thanks to the networking opportunities provided by the NZFMA and around 100 people attended the first national conference for farmers’ markets held in 2006. However, the growth of farmers’ markets and the increasing appropriation of the concept by more traditional commercial models is not without its stress and has even become the focus of media debate.

Table 13.4 Farmers’ markets in New Zealand

One of New Zealand’s leading current affair television programmes, the Campbell Live show on TV3, ran a feature on the resurgence of farmers’ markets around New Zealand in September 2007. In this feature they identified the resurgence as a response to consumers dislike of what goes into the production of their food. They pointed out that people are now more concerned about their health and nutrition and so they are looking to buy fresher produce that is grown locally. The reporter for this feature also focused on the controversy surrounding the opening of a new ‘farmers’ market’ in Auckland named ‘Farmers Market Plus’ (see http://www.aucklandfarmersmarket.co.nz). The controversy was that other farmers’ markets around the country (particularly Whangarei farmers’ market) felt that the new Auckland market was not a farmers’ market at all. The reporter defined a farmers’ market as selling primary produce sold by the producer. Customers that were interviewed at the Whangarei farmers’ market said that the sense of community and that fact that it was ‘slow shopping’ was what really defined a farmers’ market. The NZFMA opposed the name of the Auckland market incorporating the term ‘farmers’ into it, because they felt the market was not a non-profit, community-based project but a commercially orientated business. The response of the organizers of the Auckland market was that they were simply extending the farmers’ market model to work for urban Auckland (TV3, 2007).

Issues over the notion of what constitutes a farmers’ market in New Zealand closer reflect the concerns expressed in Ontario noted above. According to Chris Fortune, a chef who began the Marlborough farmers’ market, in an interview on the growth markets in New Zealand (Chalmers, 2006), the biggest plus is making sure that the farmers’ market is brand-protected. The primary producer has to be the stall-holder selling the product to ensure there are no middlemen or on-selling of goods. ‘So when the public buy the product they are talking directly to the grower’ (Chalmers, 2006). In addition, it also has to be produce from the local region and the produce has to be edible, with a few exceptions such as flowers, so there are no arts and crafts-type products.

The sustainable community focus of many New Zealand markets is well illustrated by Fortune.

‘It is the first building block of sustainability within a community. It can be used by backyard growers, someone who enjoys growing vegetables, or has an excess of potatoes they can take to the market and sell. It also suits bigger, more commercially orientated growers’. The philosophy of farmers’ markets is supporting local producers and selling direct to the public with no middleman. It also eliminates food miles – how far food travels to get to the table. ‘It’s about talking to the producer and finding out whether it’s spray-free or organic, how it’s been grown and how best to cook it’ (in Chalmers, 2006).

Exhibit 13.2 Comparing the Canterbury and Lyttelton farmers’ markets in Christchurch, New Zealand

These two farmers’ markets are located within roughly 20 minutes drive of each other in Christchurch, New Zealand. The Lyttelton farmers’ market is situated in the primary school grounds of the port town of Lyttelton whereas the Canterbury farmers’ market is situated in the suburban location of the gardens of the historic Riccarton House in Christchurch. The servicescapes of the two markets are also noticeably different with respect to music with customers at the Canterbury farmers’ market usually being accompanied by a jazz band while the Lyttelton markets has a changing selection of what would often be described as folk music every week. Although these different settings do give quite a different ambience to the markets, there are a number of similarities between the two farmers’ markets.

Analysis of the two markets was conducted in September 2007. At the time of analysis there were 24 stalls at the Canterbury farmers’ market and 30 at Lyttelton, which is the longest established farmers’ market in the Christchurch region. The markets have relatively similar offerings of produce with the most common stall type being vegetable and/or fruit stalls, both had six such stalls at the time of survey although this number does fluctuate depending on the growing season. Figure 13.2 shows the range of stall categories for each of the respective markets.

One interesting issue is the way that the two markets handle the presence of stalls selling non-food-related items. At the Canterbury farmers’ market there was a lavender stall selling lavender-based beauty products that was clearly part of the market. However, in Lyttelton an area in which people sell non-food items is kept purposefully separate from the farmers’ market. The non-food items area is beside the farmers’ market but is clearly distinguished. Such a separation reinforces the NZFMA definition of a farmers’ market (see Table 13.1) which clearly indicates that is a food market. However, if we are to look at what Brown (2001) identifies a farmers’ market to be, then the lavender stall would be included as she states that what is sold must just simply be produced by the seller and does not define that it should be an edible product. Such issues of course are not merely definitional but may affect the positioning of a farmers’ market and how it is perceived by consumers and differentiated from other types of markets.

Figure 13.2

Types of stall at the Lyttelton and Canterbury farmers’ market

Other observations on the marketing techniques of the two farmers’ markets include that 27 per cent of the stalls at the Lyttelton market and 48 per cent of the Canterbury market did not have an obvious name for their stall. This is quite high, especially for the Canterbury market. Having a banner or sign that clearly states the stall’s name is one of the simplest but yet most effective promotional practices and it is surprising that such a simple thing could be disregarded by so many stalls even when they are listed by name on the market’s web site. One of the problems with some of the stalls was that although their products had a specific name, they did not have a banner above the stall identifying who they were. So unless you are up close to the stall, it is sometimes hard to determine who they were and what they were selling particularly when visiting at a time when the market is relatively crowded.

The number of stalls that used pictures to promote their products ranged from 13 per cent at the Canterbury market to 30 per cent at Lyttelton. However, some vendors at each of the markets did use pictures to support the products being sold and provide information to the consumer. For example, the RaDiSo a sauce and dressings stall and the Canterbury Biltong stall at the Lyttelton market had laminated pictures of their products available for their customers to see. At the Canterbury farmers’ market the two Ansley farm stalls which sold fresh eggs and meat both had pictures of the farm and animals. Having clear pictures and well-made signs can help in conveying product reliability and quality, particularly when in the majority of places it is clearly impractical for consumers to visit the farms that where production occurs.

A marketing technique the vendors at each market were doing slightly better was offering samples of their products for potential customers to try; 25 per cent of the stalls at the Canterbury market were offering samples and 30 per cent at the Lyttelton market. Many of the Lyttelton stallholders had recipes available for their product and, in some cases, pictures of the finished product whereas none of the Canterbury stalls did.

More Lyttelton vendors also displayed supporting advertising than did those at the Canterbury farmers’ market. Only two vendors at the Canterbury market displayed supporting advertising. This included a web address on the banner of a French foods stall, and a written description of the making of the artisan breads which were sold by the Nikau Bakery. At the Lyttelton farmers’ market, eight stall holders offered supporting advertising for the business. This ranged from newspaper articles published on the product being sold, promotional posters and brochures. For example, the Lovat deer farm stall at the Lyttelton market sold venison products but also had brochures of their bed and breakfast accommodation; thereby showing the potential of a presence at a farmers’ market to extend the reach of their brand and products through cross-promotion. Interestingly, there was also a greater overt promotion of organic and spray-free products at the Lyttelton market even though discussions with stallholders at both markets suggest that there is likely little actual difference between the overall range of production methods used by producers selling at the two markets. However, this may also reflect the stages in organic certification that producers have reached rather than any differences in market strategy. Nevertheless, what the study of the two markets indicates is that there are clear differences in the market orientation of farmers’ markets even though they may be selling similar produce in the same region and, as in the case of these two markets, even have some of the same producers selling at them.

Fiona Crawford and C. Michael Hall

The Social Construction of the ‘Modern’ Farmers’ Market

According to Hamilton (2002, p. 73):

By definition, the modern American farmers market is not much different from its ancestor: a place where farmers sell the food they’ve grown and consumers buy it. Today, though, markets exist for more than just commerce. That they ride the social fence with my grandmother – somewhere between pure, raw agriculture and something earnest, intentional – seems contrary to their nature.

(emphasis in original)

This suggests that the modern manifestation of the farmers’ market serves some other purpose than simply the sale and purchase of goods. It is apparent that they have a social function that is meeting a need beyond sustenance. Indeed, Holloway and Kneafsey (2000, p. 292) suggest that the UK farmers’ market can be considered as a ‘… liminal space in the sense that it subverts the conventional space of food shopping (i.e. the supermarket) but also reinforces free market entrepreneurialism and celebrates particular reactionary values’. They continue that there are ‘… sets of meanings revolving around contested and emotive terms such as ‘quality’, ‘community’, ‘natural’ and ‘identity’’ (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000, p. 293). Meanwhile, McGrath et al. (1993, p. 283) argue that ‘farmers’ markets belong to a class of marketplaces experienced by consumers in a very particular way. The structure of such markets unfolds along the dimension of a formal – informal dialectic, and the function along that of an economic-festive dialect’. In a report published by the UK Institute of Grocery Distribution (IGD), Groves (2005) further extends the concept of a socially constructed meaning for fresh foods by suggesting that the purchase drivers for local and regional food products at various outlets not only include the ‘freshness’ of the food, but issues of ‘sustainability’, ‘product trial’, ‘territory and identity’, ‘attention to detail’ (or the care and effort taken in the growing and or preparation of the food) and ‘everyday indulgence’.

The notion of territory and identity associated with the consumption of local foods is also explored by several authors (e.g. Bessière, 1998; Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000; Hall and Mitchell, 2001) both from the perspective of farmers’ markets and tourism. Holloway and Kneafsey (2000), for example, suggest that UK farmers’ markets can be conceived as both an ‘alternative’ space and a ‘reactionary/nostalgic space’. As an ‘alternative’ space the farmers’ market is used ‘… as a space in which producers and consumers can circumvent the consumption spaces constructed by powerful actors in the food chain [namely, supermarkets] – an ephemeral space ‘in between’ the dominant production–consumption networks’ (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000, p. 293). Meanwhile the ‘reactionary/nostalgic’ space of the farmers’ market

… can simultaneously, and perhaps more convincingly, be read as a re-entrenchment of nostalgic and soci-politically conservative notions of place and identity. Their re-emergence during a period of ‘millenial reflection’ could be read as an element of nostalgia for a ‘golden age’ when food was supposedly more nutritious and life in general more wholesome (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000, p.294).

Holloway and Kneafsey (2000) use evidence from the Stratford farmers’ market in the UK to demonstrate how this ‘reactionary/nostalgic’ space is expressed. This includes the use of local place names and descriptors such as ‘fresh’ or ‘natural’ which imply something that has not travelled far and is derived directly from the countryside. Elements of festival or country fair (e.g. flags) are also present and there are several expressions of heritage, including a logo that is reminiscent of an antique wood cut and the ‘costumes’ of vendors which have a strong nostalgic presence.

Such representations of local identity are also likely to be attractive to tourists. (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000; Hall et al., 2003). Bessière (1998, p. 25) suggests that ‘… eating farm fresh products, for example, may represent for the urban tourist not only a biological quality, but also a short-lived appropriation of a rural identity. He (sic.) symbolically integrates a forgotten culture.’ She further suggests that such symbolism surrounding food can take several forms: ‘food as a symbol’ (e.g. red wine as the blood of Christ); ‘food as a sign of communion’ (i.e. food to be shared); ‘food as a class marker’ (e.g. champagne or caviar) and ‘food as an emblem’ (i.e. a food that is representative of a place or a people such as Roquefort cheese). Of tourists Bessière (1998, p. 24) suggests: ‘Today’s city dweller escapes in a real or imagined manner from his (sic.) daily routine and ordinary fare to find solace in regional and so called ‘traditional’ food.’

Holloway and Kneafsey’s (2000) analysis of the Stratford farmers’ market provides an important framework for the understanding of the nature of the farmers’ market space, while the work of others like Bessière (1998) have discussed the development of a strong desire for that which fresh (directto-consumer) food represents for the everyday consumer and tourist. Both studies suggest that the yearning for the nostalgic is important and that food can be the material focal point for the emergence of re-enactments of this enigmatic bygone era by the consumer and the producer. These re-enactments can be conscious and material (e.g. the use of costumes or the production and sale of ‘heritage’ or ‘heirloom’ breeds or varieties) or spontaneous, unconscious and experiential (e.g. the development of relationships between the consumer and producer), but either way they result in a space that is constructed from attempts ‘… to fix identity or build a sense of community’ (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000, p. 295) and therefore have an inherent sense of the authentic which is highly desirable for tourists.

Somewhere Between Artificiality and Authenticity

The search for authentic experience is a core component of the postmodern condition and this is especially significant in discussions of tourism and food (McGrath et al., 1993). Hall and Mitchell (2008) suggest that, when it comes to the authenticity of wine, the consumer not only wants to be assured of the authenticity of the production process, but also of the symbolic value of the wine. In many circumstances, especially those that are festive in nature or which involve travel, this may also hold true for food (Bessière, 1998; Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000; Hall et al., 2003). Farmers’ markets, by their very nature, also have a sense of authenticity which, as we have seen above, farmers’ market organizations seek to protect. Authenticity is one of four themes identified by McGrath et al. (1993) that reflect the nature of the experience of one US farmers’ market. These themes are:

- Activism: This is the grassroots response to the dominant distribution channels of industrialized agricultural systems that is also discussed by others (e.g. Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000; Feagan et al., 2004; Groves, 2005).

- Authenticity: This notion is similar to Holloway and Kneafsey’s (2001) ‘reactionary/nostalgic space’ and ‘… is a collective attempt to recapture or recreate an authentic, unmediated experience of a simpler, more wholesome era … [that] … is staged, or more properly, mythopoeic’ (McGrath et al., 1993, p. 309). In this place …

- Artificiality: McGrath et al. (1993, p. 310) contrast this with authenticity, suggesting that the experience of the farmers’ market is, ironically, ‘… an almost unattainable idealism’ where consumers attempt to ‘… buy a lifestyle from which they block the darker side’. This utopian idealism denies the fact that this is a vertically integrated retail environment like any other (e.g. Crate and Barrel and Banana Republic) and as such they are ‘retail theme parks’ that ‘… feign authenticity while surrounding the consumer with a myriad of items which are both props essential to the set and items available for purchase’ (p. 311). They construct an outdoor rural environment in an urban setting (while other such theme park retail construct ‘prototypes of home’) that are ‘… larger than life, but more importantly, [they] must be nicer than life’ (p. 311). Even the possessive nature of the term ‘farmers’ market’ is seen by McGrath et al. (1993) as evidence of this artificiality as the farmers infrequently own the market, rather they belong to the city. Indeed, the structure of many farmers’ markets are such that it is possible that some potential stallholders may be excluded by existing members because they may replicate the products offered by existing stalls or not ‘fit’ into the image or collectivity that existing members may be seeking to promote.

- Ambience: McGrath et al. (1993, p. 312) liken the market ambience to ‘retail theatre’ that ‘… engages every sensory modality, sometimes to the point of synaesthetic over-stimulation’. They also posit that the ‘disinhibiting ambience’ of the open air market means consumers get ‘carried away’, swept up in the pleasure of it all. Such a place, they suggest, is a ‘third place’ where ‘informal public life’ takes place in a realm beyond home and work.

Sellers enable buyers to enact a small scene in a larger agrarian myth. In foraging across the stalls for produce so fresh the dirt in which it was grown still clings to it in validation of its authenticity, in pursuing the small talk with the bearers of an idyllic culture which both enlightens and ennobles, and in enduring the physical rigors that an open air market demands, consumers invest the … experience with the kinds of symbolic and use values unattainable in more obviously contrived theme park-like retail settings’ (p.310).

Conclusions

There are some interesting paradoxes in the themes identified above, not least of which is the apparent juxtaposition of the (staged) authenticity and artificiality of the farmers’ market. Such staged authenticity (MacCannell, 1976) is often referred to in tourism terms as the ugly step-sister of true authenticity (whatever that might mean). While on the face of it this seems to be problematic, Hall (2007) suggests that authenticity need not relate to something that is in its pure original form and that ‘replications’ may, over time, become authentic. In this way, while the farmers’ market may be perceived to have an element of the staged and artificiality, it may attain an element of the authentic over time as it allows for what Hall calls ‘connectedness’ – a condition that many farmers’ markets seek to promote through their emphasis on being grounded in communities.

The notion of authenticity should not be used with respect to things or places. Authenticity is instead derived from the property of connectedness of the individual to the perceived, everyday world and environment, and the processes that created it and the consequences of one’s engagement with it (Dovey, 1985). … Authenticity is born from everyday experiences and connections which are often serendipitous not from things ‘out there’. … Connectedness that leads to authenticity can be provided anywhere as authenticity is not intrinsically dependent on location although place, in the sense of everyday lived experiences and relations, does matter (Hall, 2007, p.1140).

Such feelings of connectedness – as well as elements of activism, ambience and authenticity are often used in the promotion of farmers’ markets. For example, Ian Thomas, Chairman of Farmers’ Markets New Zealand in the Guide to Farmers’ Markets in New Zealand and Australia (FMNZ 2007), states with reference to farmers’ markets:

It’s a special time when the pride and passion of farmers and artisans shines through. When lovingly grown fresh fruit and vegetables are eagerly snapped up. A time and place that is a firm and regular appointment for growing numbers of folk who relish the intimacy, the friendship and the excitement of discovery … shoppers … come back for either better tasting nutrition, the most enjoyable shopping environment, riper flavours, the ability to ‘buy local’ or as an antidote to the dominating ‘more is more’ philosophy … A visit to a farmers’ market will be a memorable and delicious experience. You’ll engage in chat and often laughter. You’ll learn about how and where the food was grown or produced, how to cook it, how and where to keep it, how long it will keep and usually some good recipes to boot. Most markets have hot coffee and a good selection of local delicacies to go with it, as well as freshly squeezed juice and live music. All in all, a wonderful place to shop and get involved in a local community (FMNZ, 2007, p.13).

Undoubtedly the farmers’ market can be engaging and can connect with the consumer in very personal ways (Tiemann, 2004a,b). The experience is one that is often dialogic, where the actors are in constant communication with each other, rather than monologic as is the case with other forms of retail experience. So, irrespective of whether they are staged, mythopoeic or artificial, farmers’ markets, as a manifestation of everyday lived experiences, are a site of authentic performance. Unlike the local consumer, who might be experiencing a mythical (romantic) place, the tourist outsider who visits the farmers’ market is in fact, perhaps even paradoxically, experiencing it as an everyday (mundane) performance of local food culture, which, by virtue of its (local) cultural embeddedness, becomes the exotic, the other and therefore attractive to the tourist. For the tourist a farmers’ market’s artificiality is a component of its authenticity, it is a representation of the culture within which they are operated. It is this which the tourist can most readily and ‘authentically’ connect with. As Sassatelli and Scott (2001, p. 214) suggest ‘it is not the exceptional event (be it war or ritual) alone which imbues us with our subjective sense of belonging, but the ‘banal’ practices of everyday life; what we habitually do and in whom and what we habitually trust’.

As such tourism potentially (re)constructs the farmers’ market as an exotic (re)presentation of culture through the use of material objects (food) and an ephemeral (public) space. The space and the food brings the local culture into being, it constructs the local culture for consumption. This is not to deny that the mythopoeic element or the ‘theatre’ of the market, as the performance of these is as much an attraction as the market itself. Indeed McGrath et al. (1993, p. 307) suggest of their own case study

The Midville Market emerges as a periodic community with its own ecology, boundaries, periphery, development, members, social relationships and relationships with other communities. Participants derive pleasure from the relational aspects of this retailing institution. The personal interactions with vendors and consumers develop a loyal clientele that generates sales and sustains the institution. Here ‘human institution’ has successfully shed any oxymoronic notion and has developed to attract a growing and loyal clientele. It is relationship and perceived quality, not price, that guides their interactions and choices. Vendors guide and control this motivating force, in which consumers serve as willing partners.

This description could easily apply to many modern markets. Indeed a simple substitution of, for example, ‘Otago farmers’ Mar ket’ for ‘Midville Market’ (see Mitchell and Scott, Chapter 17), as well as other markets discussed in the following chapters would be possible and all would hold true. This is not to deny the merits or attractiveness of the farmers’ market experience which is provided and promoted to local and visitor alike, but it is to recognize that authenticity is not something that can be easily regulated and that it is a product of social construction much more than it is a certification.

References

Abel, J., Thomson, J. and Maretzki, A. (1999). Extension’s role with farmers’ markets: Working with farmers, consumers, and communities. Journal of Extension, 37(5). http://joe.org/joe/1999october/a4.html

Archer, G.P., Sánchez, J.C., Vignali, G. and Chaillot, A. (2003). Latent consumers’ attitude to farmers’ markets in North West England. British Food Journal, 105(8), 487–497.

Balsam, A., Webber, D. and Oehlke, B. (1994). The farmers’ market coupon program for low-income elders. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 13(4), 35–41.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Sage Publications, London.

Bessière, J. (1998). Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociologica Ruralis, 38(1), 21–34.

Blakemore, D. (2007). Personal conversation with Doreen Blakemore, Markets Team, Newcastle upon Tyne City Council.

British History Online (2007) at http://www.british-history.ac.uk. Visited October 2007.

Britnell, R.H. (1978). English Markets and Royal Administration Before 1200. Economic History Review, 31(2), 183–196.

Brown, A. (2001). Counting farmers markets. Geographical Review, 91(4), 655–674.

Brown, A. (2002). Farmers’ market research 1940–2000: An inventory and review. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 17(4), 167–176.

California Farmers’ Markets Association (2006). California Farmers’ Markets Association Rules and Regulations for Certified Farmers’ Markets. California Farmers’ Markets Association, Walnut Creek.

California Federation of Certified Farmers’ Markets (2003). What is a certified farmers’ market? http://www.cafarmersmarkets.com/about/

Chalmers, H. (2006). Farmers’ markets are taking off. Rural News, August 6, http://www.ruralnews.co.nz/Default.asp?task=article&subtask=show&item=9575&pageno=1

Connell, C.M., Beierlein, J.G. and Vroomen, H.L. (1986). Consumer Preferences and Attitudes Regarding Fruit and Vegetable Purchases from Direct Market Outlets. Report 185. The Pennsylvania State University, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, Agricultural Experiment Station, University Park.

Conrey, E.J., Frongillo, E.A., Dollahite, J.S. and Griffin, M.R. (2003). Integrated program enhancements increased utilization of farmers’ market nutrition program. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(6), 1841–1844.

Coster, M. and Kennon, N. (2005). ‘New Generation’ Farmers’ Markets in Rural Communities. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Barton.

Dovey, K. (1985). The quest for authenticity and the replication of environmental meaning. In Seamon, D., and Mugerauer, R. (eds.) Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and Word. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht, pp. 33–50.

Dyer, A. (1991). Decline and Growth in English Towns, 1400–1640. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Eastwood, D.B., Brooker, J.R. and Gray, M.D. (1995). An Intrastate Comparison of Consumers’ Patronage of Farmers’ Markets in Knox, Madison and Shelby Counties. Research Report 95–03. The University of Tennessee, Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology, Institute of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Knoxville.

Farmers’ Markets Ontario (FMO) (2007a). Membership information, http://www.farmersmarketsontario.com/MembershipInfo.cfm

Farmers’ Markets Ontario (FMO) (2007 b). ‘Real Farmers, Real Local’ Certified Farmers’ Market Rules and Regulations. Farmers’ Markets Ontario, Brighton.

Farmers’ Markets New Zealand (2007). Guide to Farmers’ Markets in New Zealand and Australia. R.M. Williams Classic Publications, Mosman.

Feagan, R., Morris, D. and Krug, K. (2004). Niagara Region Farmers’ Markets: Local food systems and sustainability considerations. Local Environment, 9(3), 235–254.

Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation (FGF). (2006) Canada’s First Certified Farmers’ Market: Greenbelt Farmers and Toronto Residents to Benefit from the First Certified Farmers’ Market in Canada. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation and Farmers’ Markets Ontario, Toronto. Press Release, November 22.

Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation (2007). Greenbelt Foundation 2007 Awareness Research. Summary prepared by Environics Research Group. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation, Toronto. July.

Ghent Urban Studies Team (1999). The Urban Condition: Space, Community, and Self in the Contemporary Metropolis. Uitgeverij 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Govindasamy, R., Italia, J. and Adelaja, A. (2002). Farmers’ markets: Consumer trends, preferences and characteristics. Journal of Extension, 40(1). http://joe.org/joe/2002february/rb6.html

Griffin, M.R. and Frongillo, E.A. (2003). Experiences and perspectives of farmers from upstate New York farmers’ markets. Agriculture and Human Values, 20, 189–203.

Groves, A. (2005). The Local and Regional Food Opportunity. Institute of Grocery Distribution, Watford.

Guthrie, J., Guthrie, A., Lawson, R. and Cameron, A. (2006). Farmers’ markets: The small business counter-revolution in food production and retailing. British Food Journal, 108(7), 560–573.

Hall, C.M. (2007). Response to Yeoman et al.: The fakery of ‘The authentic tourist’. Tourism Management, 28(4), 1139 –1140.

Hall, C.M. and Mitchell, R.D. (2001). We are what we eat: Tourism, culture and the globalisation and localisation of cuisine. Tourism Culture and Communication, 2(1), 29–37.

Hall, C.M. and Mitchell, R.D. (2008). Wine Marketing: A Practical Approach. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Hall, C.M., Mitchell, R. and Sharples, E. (2003). Consuming places: The role of food, wine and tourism in regional development. In Hall, C.M., Sharples,, E., Mitchell, R., Cambourne, B. and Macionis, N. (eds.) Food Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 25–59.

Hamilton, L.M. (2002). The American Farmers Market. Gastronomica, 2(3), 73–77.

Holloway, L. and Kneafsey, M. (2000). Reading the space of the farmers’ market: A preliminary investigation from the UK. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(3), 285–299.

Hughes, M.E. and Mattson, R.H. (1995). Farmers markets in Kansas: A profile of vendors and market organization. Kansas State University, Agricultural Experiment Station, Manhattan, NY. Report of Progress 658

Jolly, D.A. (1999). ‘Home made’–The paradigms and paradoxes of changing consumer preferences: Implications for direct marketing, paper presented at Agricultural Outlook Forum 1999, Monday, February 22, 1999, http://www.usda.gov/agency/oce/waob/outlook99/speeches/025/JOLLY.TXT

Kezis, A., Gwebu, T., Peavey, S. and Cheng, H. (1998). A study of consumers at a small farmers’ market in Maine: Results from a 1995 survey. Journal of Food Distribution Research, February, 91–98.

Kneafsey, M., Ilbery, B. and Ricketts Hein, J. (2001). Local Food Activity in the West Midlands. Rural Restructuring Research Group, Geography Department, Coventry University, Coventry.

Leones, J. (1995). Farm outlet customer profiles. Direct Farm Marketing and Tourism Handbook. The University of Arizona College of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension, Tucson, AZ.

Leones, J., Dunn, D., Worden, M. and Call, R. (1995). A profile of visitors to fresh farm produce outlets in Cochise County, AZ. Direct Farm Marketing and Tourism Handbook. The University of Arizona College of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension, Tucson, AZ.

MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Schocken, New York.

McEachern, M.G. and Willock, J. (2004). Producers and consumers of organic meat: A focus on attitudes and motivations. British Food Journal, 106(7), 534–562.

McGrath, M.A., Sherry Jr., J.F. and Heisley, D.D. (1993). An Ethnographic Study of an Urban Periodic Marketplace: Lessons from the Midville Farmers’ Market. Journal of Retailing, 69(3), 280–319.

Melsen, L. (2004). Identifying the potential tourism benefits of farmers’ market visitation: An analysis of the Gippsland farmers’ market visitor. Unpublished Honours Sissertation, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

MyMarket (2007). Grand opening in 2 new locations, http://www.my-market.ca/

National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association (FARMA) (2004).FARMA Consumer Survey June 2004: Nine Out of Ten Households Would Buy from a Farmshopping Outlet if They Could. National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association, Southampton.

National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association (FARMA) (2006). Sector Briefing: Farmers Markets in the UK; Nine Years and Counting. National Farmers’ Retail and Markets Association, Southampton. (also downloadable from http://www.farma.org.uk/Docs/1%20Sector%20briefing%20on%20farmers’%20markets%20-%20June%2006.pdf).

Newcastle upon Tyne City Council (2007) at http://www.Newcastle.gov.uk visited October.

New Zealand Farmers’ Market Association (2007). Fresh market locations, http://www.farmersmarket.org.nz/locations.htm

Novak, T. (1998). A fresh Place. Oregon’s Agricultural Progress, Fall/Winter (http://eesc.orst.edu/agcomwebfile/Magazine/98Fall/OAP98%20text/OAPFall9802.html#anchor1926968).

Padel, S. and Foster, C. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. British Food Journal, 107(8), 606–625.

Payne, T. (2002). US Farmers Markets–2000: A Study of Emerging Trends. Agricultural Marketing Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

Purvis, A. (2002). So what’s your beef. The Observer, 14 April. (http://www.observer.co.uk/foodmonthly/story/0,9950,681828,00.html)

Pyle, J. (1971). Farmers’ markets in United States: Functional anachronisms. Geographical Review, 61(2), 167–197.

Regional Food Australia (2007). Australian farmers’ markets Listings, http://www.farmersmarkets.com.au/

Rhodus, T., Schwartz, J. and Haskins, J. (1994). Ohio Consumers Opinions of Roadside and Farmers’ Markets. Ohio State University, Department of Horticulture, OH.

Sassatelli, R. and Scott, A. (2001). Novel food, new markets and trust regimes: Responses to the erosion of consumers’ confidence in Austria, Italy and the UK. European Societies, 3(2), 213–244.

Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Martinez, L.I., Cox, G. and Jayraj, A. (2006). African Americans’ views on access to healthy foods: What a farmers’ market provides. Journal of Extension, 44(2). Article Number 2FEA2, http://www.joe.org/joe/2006april/a2p.shtml

Tiemann, T.K. (2004 a). American farmers’ markets: Two types of informality. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 24(6), 44–57.

Tiemann, T.K. (2004 b).‘Experience’ Farmers’ Markets: Conduct Determines Performance. Eastern Economic Association Meeting, Washington, DC.

TV3 (2007) Campbell Live, aired 7 pm, September 9.

United States Department of Agriculture (2002). Improving and Facilitating a Farmers Market in a Low-Income Urban Neighborhood: A Washington, DC, Case Study. Agricultural Marketing Service Transportation and Marketing Programs, Wholesale and Alternative Markets, United States Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

United States Department of Agriculture (2006). Farmers’ market growth. http://www.ams.usda.gov/farmersmarkets/FarmersMarketGrowth.htm