Figure 4.1 First arrest on the Brooklyn Bridge. October 1, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

October 1–October 14, 2011

From Liberty Square to the Brooklyn Bridge, we are escorted by a now familiar phalanx of officers, some mounted on motorcycles, others traveling by foot. They shepherd us past a Chase bank branch and the U.S.-China Chamber of Commerce, past City Hall Park and Printing House Square. Suddenly, and mysteriously, they fall back. The crowd surges forward with a roar into the intersection of Park Row and Centre Street:

“The people! United! Will never be defeated!”

In the shadow of the great granite towers with their iconic arched portals, the Brooklyn-bound roadbed branches off to the right, while the pedestrian promenade begins its ascent to the left. It is here, at the entrance to the promenade, that a bottleneck ensues, as hundreds of marchers crowd in all at once alongside clusters of confused tourists and befuddled joggers. We quickly fill the narrow corridor past its capacity.

At this juncture, a delegation of commanding officers, walkie-talkies in hand and white shirts visible beneath their parkas, emerges at the head of the march. They appear to know where they are going. Among them is Department Chief Joseph Esposito. The “white shirts” are flanked, on one side, by a band of baby blue–clad officers from Community Affairs and, on the other, by a detachment of documentary filmmakers from the Tactical Assistance Response Unit (TARU), assigned to film the marchers’ every move. There cannot be more than twenty officers in all, but they proceed with determination and direction—directly onto the Brooklyn-bound roadway.

Is it an act of entrapment? Of accommodation? Or of desperation? I cannot make sense of their actions from where I stand. So I climb atop the fence that separates the walkway from the roadway, surveying the scene and recording what I see. While one half of the march proceeds (with some difficulty) along the planned route of the promenade, the other half of the march comes to a standstill. Moments later, as if on cue, the cry goes up to “Take the bridge! Take the bridge! Take the bridge!” Backed by the synchronized, syncopated beats of a mobile drum corps, the chant can be heard rippling throughout the crowd, each repetition growing stronger and louder than the last.

Here and there, dissenting voices can be heard. Some in Occupy’s inner circle, sensing trouble, urge the others to think twice about the consequences of their actions. Mandy, of the Direct Action Working Group, attempts to “mic check” a word of warning: “Take the pedestrian walkway! If you don’t want to risk being arrested . . . if you need to get across safely, you need to go that way!” But she and others realize they have lost all control of the crowd. The dissenting voices are drowned out by the roars of assent:

“Whose bridge?” (“Our bridge!”)

“Whose city?” (“Our city!”)

Those at the head of the march, seeing an opening, call out to one another to “link up.” This “take the bridge” bloc is made up of a diverse mix of day 1 occupiers, first-time protesters, and longtime militants from the city’s student and labor movements. The old-timers link arms with the first-timers, and they form up into lines of approximately ten by ten, complete with pacers to keep time and legal observers to keep watch.

Moments later, a critical mass of marchers—this author among them—will hop the fence and join the taking of the Brooklyn Bridge, moving slowly, methodically, into the roadway, blocking first one, then two, then all three lanes of east-bound traffic. We are greeted by a cacophony of car horns, emanating from a long line of vehicles which have come to a virtual standstill along the entrance ramp. Some are sounded in support, others in dismay or defiance. Above us, spectators and sympathizers peer down from the promenade, tweeting updates, shooting video, and snapping dramatic photos with their smart phones. One hundred feet below, laborers are laying fresh asphalt on the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Drive; they pump their fists in the air in a gesture of solidarity.

The marchers answer each show of support with the now-familiar refrain:

“We! Are! The 99 Percent!”

(“And so are you!”)

Beneath the many-colored balloons bobbing in the air, and the black, red, and red-white-and-blue flags fluttering in the wind, we make our way slowly, slowly eastward, chanting and clapping and singing as we go. The sleek fortifications of the Financial District recede behind us, as the low-lying skyline of downtown Brooklyn looms before us.

Eight hundred strong, spanning one half the breadth of the bridge, we will make it about 500 feet in—one third of the way across the East River—before the NYPD high command stops in its tracks, turns, and forms a skirmish line to bar our way forward. This time, the “white shirts” are backed by brigades of “blue shirts” called in from precincts across the city. They close in from both sides, brandishing their signature neon nets and plastic handcuffs. The high command confers, preparing for imminent mass arrests, while one of their number issues an all but inaudible order to disperse. I cannot hear a word of the officer’s orders, but I can see there is a kettle coming. Within minutes, I can tell, we will no longer have the option to “leave this area now.”

I do what I can to break out of the kettle. I fall back towards the tail end of the march, where a smaller detachment of two dozen officers is advancing up the roadway, accompanied by arrest wagons and police vans. The white shirts shout their marching orders at the blue shirts, while the blue shirts hustle this way and that, unsure of just what it is they are supposed to be doing. As they finally form a kettle, I witness one of the first arrests on the bridge. The target is an elderly man, a yogic monk in an orange robe named Dada Pranakrsnananda, who, when confronted with the threat of arrest, simply sits down, planting himself in the path of the police. When the arresting officers order him to stand, he refuses and goes limp, forcing them to cuff him and carry him, meditating, into the waiting wagon (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 First arrest on the Brooklyn Bridge. October 1, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

“He did nothing!” the crowd protests behind me. “This! Is! A peaceful march!” “The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!” It may not have been the whole world, but as we will later learn, at least 22,000 viewers around the world are, in fact, watching, as the GlobalRevolution.tv live stream team broadcasts the arrests live from the walkway above the bridge. Back on the roadway, following the lead of a street-smart contingent led by the fiery Brooklyn City Councilman Charles Barron, I make it to the other side of the skirmish line just in time to watch a wall of mesh go up behind me, and the marchers sit down, all fists and “V for Victory” signs.

Within the hour, hundreds will join Dada in those plastic handcuffs. For those trapped in the kettle, there is nowhere left to go. The only way out is up: a harrowing climb up twelve feet of trussing to the pedestrian walkway. Dozens will take their chances on the trusses. A select few will be allowed to exit the kettle without incident: white women with children in tow; a group of white students from Bard College who plead with the police to let them go. But these are the exceptions to the rule.

A commanding officer barks into a bullhorn what many of us already know: “Ladies and gentlemen, since you have refused to leave this roadway, I am ordering your arrest for disorderly conduct.” There will be so many people to arrest that the NYPD will be obliged to commandeer public buses from the Metropolitan Transit Authority, driven by unwilling transit workers, along with ten buses from the Department of Corrections, to transport the detainees to precincts around the city for booking and processing.1 One hundred fifty feet above the East River, the showdown on the Brooklyn Bridge will continue for the next two hours. As it does, the OccupyWallSt.org collective breaks the news, in real time, to the tens of thousands watching from afar:

“Posted on Oct. 1, 2011, 4:56 p.m.—Police have kettled the march on the Brooklyn Bridge and have begun arresting protesters. At least 20 arrested so far.

UPDATE: 5:15 p.m.—Brooklyn Bridge has been shut down by police.

UPDATE: 8:17 p.m.—NYTimes reporting hundreds arrested—including a reporter—police appear to have deliberately misled protesters.

UPDATE 10/2 2:20 a.m.—Over 700 protesters arrested.”2

Contrary to the claims that buzzed about the square and the Web on October 1 and the days that followed, the NYPD was, in truth, playing by the rules. As Mayor Bloomberg himself would let slip at a press conference, “The police did exactly what they were supposed to do.” And that, to many observers, was precisely the problem.

Every detail of the police response appeared to be taken directly from the pages of the department’s playbook, known as the “Disorder Control Guidelines,” issued by Commissioner Ray Kelly in November 1993 in the aftermath of the Crown Heights riots. According to the Partnership for Civil Justice, which represented many of the Brooklyn Bridge arrestees, the guidelines “make little distinction between response to violent riots or peaceful free speech assembly.” The events of October 1, the lawyers would later claim, were an outcome of an explicit policy on the part of the NYPD high command “to execute mass arrests of peaceful protesters, indiscriminately, in the absence of individualized probable cause, and without fair notice, warnings or orders to disperse.”3

As I make my way down from the bridge back to the relative safety of the square, I think back to the summer of 2004, when I had first seen these tactics in action, orange netting and all, at the protests against the Republican National Convention. Given free rein in the name of homeland security, amid the standard-issue warnings of anarchist plots and terrorist attacks, the NYPD had followed Ray Kelly’s formula of entrapment, containment, and arrest, netting some 1,806 nonviolent demonstrators in the process. When those who had made it out of the mesh nets reunited at Union Square Park, they had chanted, “The people! United! Will all get arrested!”4

Behind me, once again, the people, united, are all getting arrested. As I make my way to safety, I think back to that bleak September morning in 2004, and, for a moment, I forget what year it is, and I wonder if this is the end for the occupiers.

In a matter of hours, I will be proved wrong, as those who still have their freedom return to Liberty Square in their thousands. Many of the 732 detainees would later return to the streets and the square, their political will aroused and their commitment to the cause redoubled. As Conor Tomás Reed would later recall, “When I got out of the precinct, I went home, but I was there the next day. If anything, it made [us] more steeled. . . . I remember people getting out and going right back to Zuccotti Park.” Many more would join them after watching the arrests on YouTube and the nightly news.

While the occupiers never made it to Brooklyn that day, the imagery and the pageantry of the day would filter out to “99 Percenters” across the river and beyond, helping to bridge the usual divide between spectators and demonstrators, participants and observers. And in crossing that bridge, Occupy would be transformed from within and without.

As OWS entered its third week, the movement grew not only by means of the taking of squares, the claiming of space, or the illicit crossing of city bridges. The 99 Percenters also broadened and deepened their base of support by building new bridges with the nation’s embattled labor movement. In New York City, as elsewhere, the move from the margins to the political mainstream was made possible by the intervention of some of the city’s and country’s most formidable public and private sector unions (see Figure 4.2).5

Figure 4.2 Sources of support for OWS: unions and federations. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

Since the financial crisis, millions of union workers in New York City and across New York State had been targeted for cutbacks, layoffs, wage freezes, and furloughs. City employees had not seen a raise since March 2009. Public school aides had been faced with mass layoffs; teachers with school closures and bruising budget cuts. In the private sector, the concessions demanded of union workers were even more extreme. Verizon, for instance, had sought to squeeze higher health care premiums and a pension freeze out of its workforce, triggering a fifteen-day, 45,000-strong strike against the telecom giant.6 Yet, by the fall of 2011, organized labor had little to show for its trouble.

While the unions had sat out the initial phase of the occupation, some of the occupiers had set out to win them over. More than a few had union members in their families or in their networks of friends. Others had histories of student-labor activism or graduate student unionism. Still others had ties to white-collar unions like the Writers Guild and the Professional Staff Congress, or to dissident tendencies within the teachers and teamsters unions. Together, they had formed the Labor Outreach Committee, sending “flying squads” across the city to support local union fights (see Chapter 3).

To occupiers like Mary Clinton, the labor movement was a source of inspiration. “I think we have a lot to learn from [its] hundred-year history of direct action, civil disobedience, and winning campaigns,” she insists. “There were a lot of parallels with old-school picket lines. . . . You respected it as a similar struggle and a similar tactic.”

To many day 1 occupiers, however, who had come of age in an era of union decline and defeat, organized labor was a source of skepticism. They tended to eschew its “vertical” power structures, paid organizers, lists of demands, and links to the Democratic Party. Though they shared a common enemy in Wall Street, many wondered whether there could be any collaboration between horizontalist institutions like the NYCGA and highly union bureaucracies like those of the AFL-CIO.

Two days after the Inspector Bologna affair, Jon Kest, the ailing director of NY Communities for Change and a longtime labor organizer, had called a young occupier named Nelini Stamp into his downtown Brooklyn office. “He was like, ‘This is happening, this is exactly what we need,’” recalls Nelini. “‘We have to support this,’ [Kest continued]. ‘We’re going to get every labor union to do it.’”

In the days that followed, they had been able to do just that. “We made occupiers go and speak to union leaders. We made them have a dialogue, have a conversation. I was talking to union presidents. . . and labor was listening.” That dialogue was a transformative moment for occupiers like Nelini: “It became about the community as a whole. With labor coming into the picture . . . it just became a movement for me.”

My interviews reveal that unions were compelled to rally to Occupy’s side, not only by pressure from above, but also by a surge of support from below. According to one SEIU organizer, “[The unions] had seen their workers were invested in this movement. They had seen that folks were in solidarity with [OWS]. . . . The rank-and-file pushed their leadership because this was a thing that made sense to them.”

One of the first union locals to come on board was Local 100 of the Transit Workers Union of America (TWU), a notoriously feisty outfit with a history of militancy, representing 38,000 workers across the five boroughs. On September 28, an M5 bus driver had idled his vehicle at Liberty Square, honked his horn, and proclaimed that his union would be joining the protests that Friday. That night, the motion to endorse the occupation was carried unanimously at an angry meeting of the union’s executive board. By hitching its wagon to OWS, Local 100’s leadership would win new leverage for its workers over Wall Street, City Hall, and the Metropolitan Transit Authority.7

Independently, a group of professors and other education workers at the City University of New York had put out an open letter and Facebook event calling for a labor demonstration that Friday at One Police Plaza, headquarters of the NYPD high command. The call was simply worded and precisely aimed: “We the undersigned condemn recent police attacks. . . . Join us in calling for an end to police repression of protests in New York, and to support the ongoing Occupy Wall Street demonstration.” Hundreds of trade unionists, from maintenance workers to tenured professors, answered the call from CUNY and descended on One Police Plaza that Friday. Among the signs borne by a band of TWU members in matching “We Are 1” jerseys: “Some things money can’t buy. I will not submit to this system. I am here with no fear.”8

That very day, thirteen more unions would follow the lead of the transit workers, voting to endorse the occupation as well as the upcoming “Community/Labor March to Wall Street” on October 5. Among the occupiers’ new allies were powerhouse public sector unions like the United Federation of Teachers and the American Federation of State, Council, and Municipal Employees, along with the largest union local in the nation—the 400,000-member Local 1199 of the Service Employees International Union—which promised one week’s worth of food and a volunteer force of registered nurses.

At the same time, OWS earned the endorsement of four internationals with a combined membership of almost 2 million: the Communications Workers of America, the United Steelworkers, National Nurses United, and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. In a matter of days, the AFL-CIO as a whole would join the club, pledging, “We will open our union halls and community centers as well as our arms and our hearts to those with the courage to stand up and demand a better America.”9

The occupations had a powerful demonstration effect on union members and leaders alike, showing that a broad-based movement for economic justice, powered by direct action and radical democracy, had the potential to change the political equation for working people.

“These young folks are out there and they’re singing our tune,” said Jim Gannon of the Transit Workers Union. “They’re saying what we’ve been saying for quite some time, that the so-called shared sacrifice is a one-way street. Young people face high unemployment . . . and in many ways they’re in the same boat as public sector workers are. So we all get together, and who knows? This might become a movement.”10

Four days after the battle of the Brooklyn Bridge, we would catch another glimpse of the Occupy-labor alliance in action. Endorsed by fifteen unions and twenty-four grassroots groups (see Figures 4.2 and 4.3), the “Community/Labor March on Wall Street” on October 5 would prove the movement’s most potent show of force to date.

The call to action had been drafted by organizers with NY Communities for Change, then printed and distributed by allied unions: “Let’s march down to Wall Street to welcome the protesters and show the faces of New Yorkers hardest hit by corporate greed.”11

Figure 4.3 Sources of support for OWS: nonprofit organizations. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

From the triumphal arch of Washington Square Park down to the steps of the Foley Square courthouses, the signs of the times were on vivid display, inscribed on squares of cardboard and strips of fabric. In the same square where the U.S. District Court had upheld the Smith Act, making it a crime to “advocate the duty, necessity, desirability. . . of overthrowing or destroying [the] government,” there were now open calls to “Turn Wall Street into Tahrir Square” and “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death.”

Just down the street from the site of the Hard Hat Riot of 1970, where construction workers had set upon student anti-war marchers with clubs and crowbars, there were hard hats lifting a “Flag of Heroes” beside “Students and Workers United in Solidarity with #OWS.” Together, they streamed into Foley, then southbound toward Liberty Square, chanting, “Students! And labor! Shut the city down!”12

The march also reflected the changing profile of the American working class. There were tattooed teamsters from Local 445, but they were of many races, ethnicities, and sexualities. They stood side by side with their counterparts from Local 100, sharing slogans, small talk, and cigarettes. There were nurses of both genders, some of them marching in uniform, bearing red-and-white picket signs that read, “America’s Nurses Support #OccupyWallStreet.” There were muscle-bound laborers from Local 108, but they marched under a bright blue flag featuring an image of Planet Earth.

To the west and to the north, behind the union rank-and-file, stretched a long column of 99 Percenters in their “complex unity”: undocumented Americans affirming, “Somos El 99 Percent”; unemployed workers demanding “Jobs Not Cuts” and “Jobs Not Wars”; indebted undergraduates inveighing against “Indentured Servitude”; single mothers with their children, testifying, “I Can’t Afford to Go to the Doctor”; the homeless reminding the nation of its “44 Million on Food Stamps” and its “Millions [of] Lost Homes.”13

Yet for all the multiplicity of personal narratives and political missives on display, there was also an unprecedented coherence in some of the signs I saw and the chants I heard that day. This coherence was no accident, I would later learn, but a product of the occupiers’ deepening dependence on the resources, experience, and know-how of their newfound allies in organized labor. Some of the leading unions, eager to keep the day’s actions “on message,” had printed thousands of picket signs in bold black-and-white lettering bearing the most popular of movement mantras: “WE ARE THE 99 Percent.” These two-tone signs were a ubiquitous sight all up and down the length of the march.

Together with the chants of the same vintage, they evoked the collective identity that remained the movement’s least common denominator. As that identity was projected onto a national screen, it would lend labor a new source of solidarity, the occupiers a new seal of legitimacy, and the Left a point of unity long absent from the political scene.

The “99 Percent” contained multitudes, including communities and constituencies with long histories of disenfranchisement. In light of this fact, the People of Color (POC) Working Group emerged early on to take up the struggle for equality and empowerment within OWS, as well as without. The very existence of the POC Working Group contradicted the oft-heard claim that the occupiers were building a postracial society in the square, a little concrete utopia devoid of racism and other inherited oppressions.

Michelle Crentsil, co-founder of the group remembers its original rationale: “We’re all running around, saying, ‘We are the 99 Percent!’ That’s fine and dandy, but a white household is worth, on average, twenty times more than a black household. So we’re not the same. Communities of color are disproportionately affected by economic injustices. . . . Those are issues we have to be able to recognize and call attention to.”

“POCcupy” emerged in the aftermath of the “We Are All Troy Davis” march. The idea came out of a series of conversations occurring simultaneously among diverse circles of friends: one of them a group of young black women working in the labor movement, another a group of student and community activists affiliated with South Asians for Justice. All had found themselves situated in an ambiguous position in Liberty Square, at once mobilized by the occupation and marginalized by its power dynamics. Seven “POCcupiers” came together for the first time on October 2, at a meeting held in the shadow of the “Red Thing.” Two days later, on the eve of the Community-Labor March, they issued a “Call Out to People of Color”:

To those who want to support the Occupation of Wall Street, who want to struggle for a more just and equitable society, but who feel excluded from the campaign, this is a message for you. . . . It is time to push for the expansion and diversification of Occupy Wall Street. If this is truly to be a movement of the 99 Percent, it will need the rest of the city and the rest of the country. . . . We must not miss the chance to put the needs of people of color—upon whose backs this country was built—at the forefront of this struggle.14

This statement stirred audiences to action as it made its way through cyberspace by way of the group’s online platforms, and through urban space by way of the written and the spoken word.

Yet when Michelle and others sought to use the People’s Mic to get the word out about the next meeting, they found the crowd would fall suddenly silent: “We would walk through the park and yell ‘Mic check!’ And we’re like, ‘People of Color Working Group!’ And all of a sudden, it gets all muffled and nobody’s repeating you anymore. I remember that one. That one really hurt.”

Despite such constraints, the group grew by leaps and bounds over the course of October. Its growth continued unabated after it was decided, amid cries of “reverse racism,” that membership would be closed to whites. Its members formed a series of subcommittees mirroring the working groups of OWS as a whole, which would work in conjunction with one another and in collaboration with white “allies” in the GA. They had their own outreach outfit, which urged urban publics everywhere to “occupy your ’hood” and “occupy el barrio”; they had a POC press team to counteract media bias, making nonwhite faces visible and nonwhite voices audible.

Some took up the practical tasks that had gone neglected by the GA: child care for campers with children; safer spaces for female-identified occupiers; language access for non-English speakers. Others organized around issues and themes of special concern to members of the caucus: “Police Brutality,” “Prison Solidarity,” “Immigrant Worker Justice.” Finally, members offered their assistance to allied actions organized by outside groups: a “Don’t Occupy Haiti, Occupy Wall Street” march across the Brooklyn Bridge; an Indigenous People’s Day march and Mixteca danza; a Jummah Friday “pray-in” by a group of Muslim occupiers.

Occupiers of color also continued to confront the reality of white power in the square and its satellite sites, in assemblies and street actions, in working groups and one-on-one interactions. Operational funds flowed freely to every group but the POC. Many who had come to the occupation to speak out found their voices silenced, their views sidelined by the facilitators and the drafters of key documents—often on the pretense that they had not gone through “the right process” or spoken to “the right people.”

The original Declaration of the Occupation, for instance, reflected the “postracial” politics of the white liberals who had penned it, to the exclusion of other voices: “As one people formerly divided by the color of our skin,” read one draft, “we acknowledge the reality that there is only one race, the human race.” These words would have constituted the opening line of the GA’s first public statement, had it not been for a controversial “block” on the part of a contingent from South Asians for Justice.15

Throughout the occupation, I often witnessed white speakers seize the People’s Mic from people of color. At an anti–police brutality rally, I heard a white organizer shut down the lone speaker of color—a black woman who had lost a relative to a police shooting—with an injunction to “keep it peaceful.” One night in early October, I witnessed a middle-aged white man, sporting a Ron Paul pin and a parrot on his shoulder, read the U.S. Declaration of Independence at the top of his lungs in order to drown out a group of Mexican immigrants from the Movement for Justice in El Barrio, who had come to read a statement of support for OWS. Time after time, it would fall to the POC to “police” other occupiers—even as its members were themselves being policed, on a daily basis, ever more aggressively than their fellows.

The challenges facing would-be occupiers of color were not just of an interpersonal nature, but also of a deeply structural and institutional character. Across the city and beyond, people of color continued to face disproportionately higher rates of arrest, prosecution, and incarceration—a fact that surely weighed heavily on an individual’s decision to occupy or not. And when the Great Recession had hit home, African American and Latino New Yorkers had been the first to lose their jobs, the first to be evicted from their homes, the first to see their schools closed and their social services cut.

Malik Rhasaan, 40, is a father of three from Jamaica, Queens, and the founder of Occupy the Hood. “All the things they were talking about . . . it’s our communities that got the hardest hit,” he would later tell me. “Talk about home foreclosures, talk about lack of healthy foods, talk about the prison-industrial complex. I live in a community in Queens that has one of the highest foreclosure rates in the country.” Yet the more time Malik spent in Liberty Square, “the more and more I noticed people who looked like me weren’t there. The conversation just wasn’t about the communities that needed it the most.”

As the occupations spread with lightning speed across the continent, occupiers of color could be found the front lines from the first. Occupy Oakland (OO) presented another case in point. Inaugurated on October 10—Indigenous People’s Day—Oakland’s occupation kicked off with a festive public gathering and general assembly on the steps of the amphitheater in Frank Ogawa Plaza. The occupied plaza was promptly renamed in honor of Oscar Grant, a young black man who had been shot in the back by police on January 1, 2009, precipitating weeks of urban unrest. From day 1, OO earned the endorsement of SEIU Local 1021 and other East Bay unions, as well as the blessing of many Chochenyo Ohlone people, who would join its call to “decolonize Oakland.”

From its inception, OO had a markedly different content and more militant tone than its counterparts in other cities, making it less hospitable to a politics of compromise. Inspired, they say, by Oakland’s long history of black radicalism, and, more recently, by the anti-police rebellions and student occupations of 2009–2010, the occupiers of Oscar Grant Plaza staked out a distinct position within the 99 Percent movement, a political pole all their own. Theirs was a politics of total refusal, which went beyond opposition to the big banks and “Wall Street West” to an outright assault on what many believed to be fundamentally illegitimate institutions of local, state, and federal governance.

The first public pronouncements of the Oakland GA expressed this insurrectionary credo in no uncertain terms:

OO is more than just a speak-out or a camp out. The purpose of our gathering here is to plan actions, to mobilize real resistance, to defend ourselves from the economic and physical war that is being waged against our communities. . . . TO THE POLITICIANS AND THE 1 PERCENT: This occupation is its own demand . . . we don’t need permission to claim what is already ours. . . . There is no specific thing you can do in order to make us “go away.” . . . Our goal is bring power back where it belongs, with the people, so we can fix what politicians and corporations have screwed up. Stand aside!16

This uncompromising ideology was effectively hard-wired into the occupation from the outset.

At the same time, OO’s base was broader than its radical core. The daily assemblies, teach-ins, and other gatherings attracted participants of many stripes, political persuasions, and social positions. Boots Riley, a revolutionary hip-hop artist who grew up in Oakland, remembers, “A lot of folks who did join Occupy Oakland were folks who used to hang out at Oscar Grant Plaza before Occupy Oakland. Especially younger folks, not having anything to do, selling weed, whatever. But they became radicalized. . . . This guy Khalid tells this story: ‘I saw a bunch of white people, seemed like they had some weed. . . . But I heard people speaking at the GA, and my life changed.’”

Life changed, too, for others who took part in the tent city, which “offered hundreds the semblance of a home”; the Children’s Village, which “provided parents with basic child-care services”; and the Kitchen, which, at its height, fed over a thousand people a day.17 Robbie Clark, a transgender black man and local housing organizer, tells me, “I remember talking to this one family who had been sleeping under a freeway. They were like, ‘At least I can sleep with other people, and I know there’s gonna be food for me and my children. At least I’m safer here than I was under the freeway.’”

Back in Liberty Square, the working groups were hard at work, struggling mightily to meet the needs of the occupiers and the demands of a growing occupation. Foremost among them was the Food Working Group and its ragtag army of volunteers—which one coordinator estimated to be “about 50 percent college graduates and 50 percent ex-convicts.” Anchored in the center of the park by a row of folding tables and milk crates, its People’s Kitchen served as an improvised safety net for the denizens of the square.

Before every GA, and in preparation for each day of action, I would take my place in line and fill my plate with an unpredictable harvest: organic produce donated by upstate farmers, the latest homemade concoctions cooked in cramped Manhattan apartments. Here, I encountered an ever more diverse crowd of occupiers, including many in need of nourishment but without the means to pay for it. Some came for the free food and left when it was depleted. Many more stayed on to volunteer their time and labor, devoting up to eighteen hours a day to cooking, cleaning, and serving all comers.

Diego Ibanez, a young occupier of Bolivian origin who quit his job in Salt Lake City to join OWS, remembers his first days working in the People’s Kitchen: “The humblest people were cooking for others and serving for others. I really got to know a lot of the kitchen folks. Part of it was strategic. I had no money. I had nowhere to stay. I didn’t know anybody in New York. I needed to eat somehow. Working in the kitchen, that was the best way.” Diego also remembers “seeing the community members come in. I remember this woman, she was like, ‘Who’s your leader? I got presents for him.’ I was like, ‘We’re all leaders.’ And she was like, ‘Whatever, I got some avocados!’”

Despite the flow of donated foods, funds, and people power, by October, the needs of the occupiers were threatening to outstrip the kitchen’s capacity to provide for them. As the hungry crowds descended on the square, they found an overworked, overstretched band of kitchen workers, increasingly prone to burning out, skipping shifts, even going on strike. Some blamed this turn of events on the influx of homeless New Yorkers, while others insisted these were as much a part of the occupation as anyone else.

“If we can feed people who need food, that’s an important thing to be doing,” says Manissa McCleave Maharawal, an occupier of color and CUNY organizer from Brooklyn. “It’s not just important because people need food. It’s also politically important. . . it’s like bread and butter. [But we] came up over and over again against these discourses and practices of worthy occupier [versus] unworthy occupier.”

As private kitchens proved inadequate to the task, it fell to some of society’s more traditional service providers to step in: the churches. The first to open its doors was Overcoming-Love Ministries, Inc., an interdenominational congregation that ministered to the homeless and the formerly incarcerated. At the invitation of Pastor Leo Karl, a radically inclined reverend exiled from Argentina during the Dirty War, the People’s Kitchen set up shop in his Brooklyn soup kitchen, the aptly named “Liberty Café.”18

Every day, boxes full of donated foods and cars full of volunteer chefs would cross the bridge, bound for East New York. Between 1 p.m. and 6 p.m., the volunteers would cook up massive quantities of vegetables, grains, meats, potatoes—enough to feed 1,500 on weeknights and 3,000 a night on weekends. The food, once cooked, would be transported by the truckload back to Liberty Square. The next shift would arrive in time for dinner, serving heaping portions to the hungry crowds and tending to the towering piles of dishes. Finally, the OWS Sustainability Committee would get to work filtering the graywater, extracting the food waste, and distributing what remained to local community gardens. The following morning, the cycle would begin all over again.

Day in and day out, for the duration of the occupation, the People’s Kitchen would continue to feed the hungry masses. As it did, it also served other social functions. First, it attracted 99 Percenters from radically different social positions to the same place each day, where they could sit and eat side-by-side. Second, it worked to dramatize the effects of inequality and extreme poverty in the age of austerity. Third, it testified to the capacity of “ordinary people” to take care of one another, to share things and tasks in common, and to begin to reorganize society in the service of “people, not profit.” It was, in the words of the kitchen workers, a “revolutionary space for breaking bread and building community.”19

In addition to those who did the hard work of cooking, cleaning, and caring for the occupiers, there were those who played more visible roles as the facilitators of group processes. The act of facilitation, one of Occupy’s elder trainers once told me, was best understood as the process of “enabling groups to work cooperatively and effectively.”

In theory, the role of the facilitator was rather straightforward: to “support and moderate” the general assemblies in order to construct “the most directly democratic, horizontal, participatory space possible.” In practice, the place of the facilitator was one of the most hotly contested in all of Occupy, with many citizens and denizens of the square alleging that the Facilitation Working Group functioned as a sort of “shadow government,” a “de facto leadership” in an avowedly leaderless movement.20

As a member of the Facilitation Working Group, you would be empowered to set the agenda for the nightly assemblies, a process that unfolded each day at the Deutsche Bank atrium, often to considerable controversy. If elected to serve as a facilitator for the night, you would take your place atop the stone steps of the square alongside the other members of your facilitation team. You would go on to run the assembly according to strict protocol, guiding the gathering from point A to point B; setting “ground rules”; calling on speakers to propose or oppose; taking “temperature checks” of group sentiment; dealing with “blocks” or objections; and “making people feel excited about participating in direct democracy.” It was a political performance of the highest order.21

According to veteran facilitator Lisa Fithian, a white anarchist activist from Austin, Texas, “What happened was we had these mass public assemblies [and] working groups . . . but we needed people to help make all of that happen. So we created a facilitation group where people learned how to facilitate meetings and to coordinate facilitators and agendas.” The problem was, “nobody knew how to do it. We had a whole new generation that woke up . . . that had very little skills, experience, or analysis.”

Those who did have the skills and the experience tended to gravitate toward the Facilitation Working Group. They tended to be highly networked, deeply committed, and biographically available, with time to spare for one hours-long meeting after another. One particularly prominent facilitator tells me he “started in facilitation because I could. . . . I was completely invested. I had the time. I had the social skills. I knew everyone.” Others in the group strove to share their political know-how by way of daily “direct democracy trainings,” which aimed to teach the techniques of facilitation to the uninitiated.

Many occupiers refused to recognize the authority of the working group in the first place. On one side were the most hard-core horizontalists, who were quick to criticize anyone who came to the general assembly with an agenda or a job title. Performance artist Georgia Sagri was among the fiercest of such critics: “I was and I am still against any idea of facilitation. . . . The moment that you have facilitation there is [the] assumption of an end point. . . . You will need a committee to tell you what to do. And the assembly [will become a] spectacle, trapped in endless bureaucratic procedures.”

On the other side were those who had not consensed to the consensus process in the first place, and who saw the facilitators as fetishizing process over strategy, form over function. One of the dissidents was Doug Singsen, of the Labor Outreach Working Group, who argues that “Occupy’s “most influential decision-makers” were “committed to these ideals of horizontalism and autonomy . . . but tended to sideline grievances that affected ordinary people’s daily lives. Their approach foreclosed real strategic thinking.”

To be sure, there were practical and political merits to the facilitators’ methods. They created the conditions for thousands of citizens of the square to be able to speak and be heard without amplification, and to practice democracy in public without commercial interruption. In the midst of the Financial District, this was no small feat. Yet the facilitators were increasingly unable to keep order in the assembly, to maintain their own legitimacy, or to reconcile Occupy’s horizontal process with its hierarchical inner life.

“Tragically,” says Lisa Fithian, “the facilitators came under attack as power holders, because they were helping to set agendas and move the discussion. What Occupy could have used was a process or coordinating group that could envision and guide the processes Occupy was trying to use.” In the absence of such a group, it fell to Facilitation to keep the consensus process going—with or without the consent of the facilitated.

During the first four weeks of OWS, the occupiers had come to make competing, often conflicting claims on the space and time of the square and its satellite sites. There were the media makers and the decision-makers, who claimed the square as a stage for the public performance of direct democracy. There were the organizers and the agitators, who made of the space a base camp for larger projects of reform or revolution. There were the volunteer workers, who claimed the space as a cooperative workshop for the provision of public goods and services. And there were the consumers of those goods and services, who found in the square a safety net they could not find anywhere else.

Then there were the drummers. Calling themselves the “pulse” of the occupation and the “heartbeat of this movement,” they claimed the square’s western steps as a space of unchecked self-expression. For ten or more hours a day, often echoing into the early hours of the morning, their congas and bongos lent a brash, syncopated rhythm to life in the square. At times, they drew dancing, clapping crowds to their side, and kept spirits up on days of action and inaction. At other times, the din of the drummers drew the ire of their fellow occupiers as it drowned out the People’s Mic and threatened to drive a wedge between the newcomers and their neighbors.

The locals were less concerned with the happenings in the park per se than they were with its effects on the larger living environment. While many residents were initially supportive of the occupation, their support was growing ever more tenuous with every late-night drum circle. When hostile motions were brought to Community Board One by the local Quality of Life Committee, Occupy’s Community Relations Working Group turned to intensive mediation, collaborating with committee members in the crafting of a “Good Neighbor Policy.” The new policy would, in theory, limit drumming to two hours per day, appoint security monitors in the park, and promote a “zero tolerance” policy toward drugs, alcohol, violence, and verbal abuse.22

Yet there were much more powerful players in the game with an institutional stake in what was happening in the square. Among these was Mayor Michael Bloomberg himself, who, as a sometime financial services CEO and longtime booster of the city’s finance sector, made no secret of his contempt for OWS. As early as September 30, Bloomberg denounced the occupiers for “blam[ing] the wrong people,” when New Yorkers ought to be doing “anything we can do to responsibly help the banks.” One week later, in a radio address, the mayor’s rhetoric took on an even more adversarial tone, arguing that, “What they [the occupiers] are trying to do is take the jobs away from people working in this city. They’re trying to take away the tax base we have.”23

Still, when it came to Zuccotti Park, the occupiers, for the moment, were inhabiting a legal gray area. As a “privately owned public space,” the park was contractually mandated to remain open to the public twenty-four hours a day (see Chapter 3). The owner, Brookfield Office Properties, was Lower Manhattan’s largest commercial landlord, with 12.8 million square feet in its possession. In order to “leverag[e] Downtown’s dynamic changes in retail, transit and parkland,” Brookfield needed the approval of the City Council. With the Democratic establishment siding with OWS, Brookfield, for a time, decided to defer to City Hall. “We basically look to the police leadership and mayor to decide what to do,” noted the park’s namesake, John Zuccotti. At the same time, Commissioner Kelly argued, to the contrary, that it was “the owners [who] will have to come in and direct people not to do certain things.”24

By early October, with the occupation growing in numbers and impact, and the occupiers making good on their pledge to occupy indefinitely, Brookfield’s executive officers decided they had had quite enough. On October 4, they issued a new set of “basic rules” that included “bans on the erection of tents or other structures” and prohibitions on “lying down on benches, sitting areas or walkways.” Brookfield concluded with what would become its most commonplace complaint: “The park has not been cleaned since Friday, September 16, and as a result, sanitary conditions have reached unacceptable levels.”

On October 11, CEO Richard Clark followed up with a strongly worded letter to Commissioner Kelly, calling the occupiers “trespassers” and urging the City to intervene:

The manner in which the protesters are occupying the Park violates the law, violates the rules of the Park, deprives the community of its rights. . . and creates health and public safety issues that need to be addressed immediately. . . . Complaints range from outrage over numerous laws being broken. . . lewdness, groping, drinking and drug use . . . to ongoing noise at all hours, to unsanitary conditions and to offensive odors. . . . In light of this and the ongoing trespassing of the protesters, we are again requesting the assistance of the New York Police Department to help clear the Park . . . to ensure public safety.25

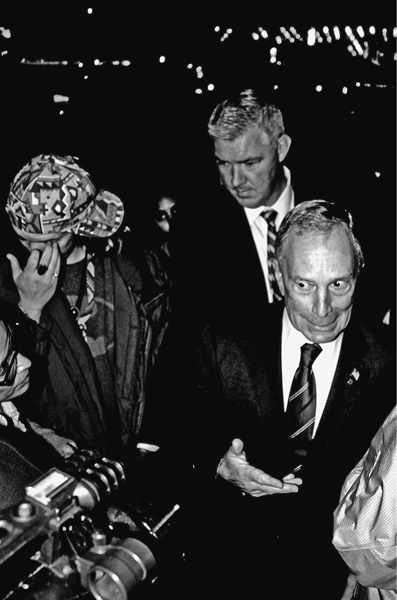

Mayor Bloomberg responded almost immediately to the CEO’s pleas for help. On the evening of October 12, I witnessed the mayor’s first and only appearance at Zuccotti Park, hours after we had pitched our first tent in the square (a “civil disobedience sukkah”). I recorded the surprise visit from start to finish as he and his security detail cut a halting path from Broadway to Church Street, betraying visible disgust at the sights, sounds, and stench of an ordinary night in the park. The mayor’s visit was greeted with Bronx cheers and chants of “Whose city? Our city!” and “You! Are! The 1 Percent!”

“People have a right to protest, and other people have a right to come through here, as well,” the mayor extemporized. “The people that own the property, Brookfield, they have some rights, too. We’re gonna find a balance. . . . Everybody’s got different opinions.” These were the only words I heard from the mayor’s mouth before his security detail spirited him into a waiting town car on Church Street (see Figure 4.5).

The meaning of his visit was initially shrouded in mystery, but not for long. Hours later, Deputy Mayor Caswell Holloway would inform us that, “on Friday morning, Brookfield Properties will clean the park. . . . The protesters will be able to return to the areas that have been cleaned, provided they abide by the rules that Brookfield has established.” The next morning, we would receive a letter from the company itself, stating matter-of-factly that, come Friday, “it will be necessary for the public to leave the portion of the Park being cleaned.” It was then that we knew the score. What we had in our hands was New York’s first eviction notice.26

With a showdown looming over the fate of OWS, the occupiers had a little over twenty-four hours to come up with a strategy to defend the square. We heard cautionary tales from veterans of Bloombergville and the acampadas of Barcelona and Madrid (see Chapters 1 and 2), where sanitation had been used as a pretext for police action to evict the occupations. We also heard word of a wave of mass evictions, which had commenced just three days before at Occupy Des Moines and Occupy Boston.

When some 200 occupiers had sought to occupy the grounds of the Iowa State Capitol, they had been answered in short order with pepper spray and arrests, thirty-two in all. When asked about the rationale for the raid, Governor Terry Branstad would go on to echo the words of Mayor Bloomberg himself: “I’m very concerned about not sending the wrong signals to the decision makers in business.”

Later that night, at 1:30 a.m., hundreds of Boston occupiers had been detained en masse along the Rose Kennedy Greenway, as they attempted to expand the occupation from their base camp in Dewey Square. Among the first to be arrested were veterans of the Vietnam War, who were memorably manhandled and thrown to the ground, along with their star-spangled banners, live on Livestream.us and GlobalRevolution.tv. Mayor Thomas Menino would later justify the 141 arrests on the grounds of the $150,000 the city had invested in new greenery for the Greenway.27

Like his counterparts in Boston and Des Moines, Mayor Bloomberg clearly intended, not to clean the square, but to cleanse it of those who called it home. The response from the occupiers was swift: “We won’t allow Bloomberg and the NYPD to foreclose our occupation.”28 The scale of the “rapid response” overshadowed that of all other OWS actions to date. The “operations groups”—Direct Action, Facilitation, Media, and above all, Sanitation—held an “emergency huddle” in the park, while unaffiliated occupiers called a “People’s Meeting” to debate what was to be done.

Consensus was quickly reached on a three-pronged strategy of “eviction defense.” It would begin with a pressure campaign targeting both Brookfield and Mayor Bloomberg, combining press conferences and whisper campaigns, and uniting strange bedfellows from a variety of political parties (see Figure 4.4). It would continue in the square itself with “Operation #WallStCleanUp,” during which the occupiers would converge on the park for a “full-camp cleanup session.” It would conclude, Friday morning, with a “human chain around the park, linked at the arms.”29

All day Thursday, the machinery of solidarity was set in motion, and the political pressure campaign kicked into high gear. Fourteen City Council members signed a letter urging the mayor to “respect the deep traditions of free speech and right of assembly that make this a great, free, diverse, and opinionated city and nation.” Some of them reportedly issued veiled threats to the board of Brookfield, saying they would make it more difficult for the company to do business in the city if the eviction went ahead.

Just across the street from the square, Community Board One held a press conference in support of the occupiers, as did Public Advocate Bill de Blasio. “This has been a peaceful and meaningful movement and the City needs to respond to it with dialogue,” reasoned de Blasio (who was already preparing for his run to replace Mayor Bloomberg). Meanwhile, the AFL-CIO, MoveOn.org, and others were mobilizing hundreds of thousands of supporters to sign petitions, send e-mails, and make phone calls to City Hall. By nightfall, MoveOn.org’s petition alone had garnered over 240,000 signatures.30

Figure 4.4 Sources of support for OWS: parties and other formations. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

I arrived in the park early Thursday evening for an emergency GA, which was to be followed by the all-night cleanup operation—a ritual of participation coupled with a ritual of purification. Many occupiers had already spent the day on their hands and knees in the square, mopping its walkways, scrubbing its stone surfaces, and hauling away heaps of fabric, plastic, and cardboard in giant garbage bags.

Figure 4.5 Mayor Bloomberg in Liberty Square, October 12, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

The GA kicked off with an announcement from the legal team that they were prepared to take the mayor and the park’s owners to court. Moe from Sanitation then put out a call to arms: “If you have arms to move anything. . . I expect you to clean. It’s not a mandate, but it’s not an option. We gotta make this place shine!” Next up were the street medics, who announced the imminent arrival of a mobile first-aid station; the Mediation team, who urged the occupiers to “create a strong peaceful image” with an all-night vigil along Broadway; and representatives from the Direct Action Working Group (DAWG), who issued the obligatory message of defiance: “Tomorrow’s cleaning plan seems a lot like an eviction plan. . . . Fuck that shit! We will resist!” To wild cheers from the crowd, the DAWG unveiled its plan of action: “By our good graces, we will allow the park to be re-cleaned by Brookfield in thirds. We will hold no less than two-thirds of our park at all times.”

When the assembly dispersed, I joined a small army of amateur sanitation workers, while others practiced rapid-response drills in preparation for the day of reckoning. Armed only with mops and buckets, we worked through the night to sweep, scrub, and squeegee our hitherto grimy granite home. Before midnight, the skies opened up, sending sheets of water rushing westward, carrying with it any muck the sanitation army had missed. Supporters wandered to and fro, one dispensing ponchos, a second proffering “tear gas onions,” a third passing out glow sticks as if at an all-night rave. A lone young man stood to one side, playing the trumpet under an umbrella. Another sat inside the “civil disobedience sukkah,” praying for a solution. Here and there, I spotted a “bike scout,” tasked with keeping track of police. Every now and then, an occupier mic-checked a word of warning, or a profession of love, to anyone who would listen.

By 6 a.m., there was hardly any space to move about the square, swarmed as it was with some 3,000 supporters. Many were union members, who had gotten the memo from their elected leaders: “Go to Wall Street. NOW.” One ironworker from Local 433 toted a cardboard sign: “I’m Union. I Vote. I’m Pissed, So I’m Here!” Another waved the Gadsden flag favored by the Tea Party, emblazoned with the Revolutionary War–era motto, “Don’t Tread on Me.” The unionists were joined by New Yorkers of all descriptions, who had converged from all directions in response to the call of social media to “Stand with us in solidarity starting @ 6am.” From an improvised soapbox on the north side of the park, speaker after speaker roused the crowd with incendiary rhetoric: “We will not be defeated!” “This is our revolution!” It was there that I would hear the news reverberating off of the urban canyons in the rhythms of the People’s Mic:

“Mic check!” (“Mic check!”)

“I’d like to read a brief statement. . .” (“I’d like to read a brief statement!”)

“From Deputy Mayor Holloway. . .” (“From Deputy Mayor Holloway!”)

“Late last night, we received notice from the owners of Zuccotti Park . . .” (“. . . received notice from the owners of Zuccotti Park!”)

“Brookfield Properties. . .” (“Brookfield Properties!”)

“That they are postponing their scheduled cleaning of the park!”