Figure 5.1 “Cattle pens” in Times Square. October 15, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

October 15–November 15, 2011

“OCCUPY WALL STREET MOVEMENT GOES WORLDWIDE . . .”

So reads the ribbon of LED lights that crowns Walt Disney’s Times Square Studios. The strange glow illuminates the faces of the occupiers as they peer up, transfixed, from inside the NYPD “cattle pens” arrayed along 44th Street and 7th Avenue (see Figure 5.1). Their hand-painted signs stand in pointed contrast to the multimillion-dollar “spectaculars” that shine down from on high.

Today is October 15, the day the “indignant ones” have designated their first “global day of action.” Over the course of twenty-four hours, the citizens of eighty-two countries will stage mass actions and popular assemblies in 951 cities, all under the aegis of Occupy and in the name of the 99 Percent. I wonder aloud whether the Times Square news tickers have gotten the story backward—after all, was there not a worldwide movement before there was an Occupy Wall Street?—but my voice is drowned out by the roar of excitement heard with every passing headline.1

Contrary to the tickers’ tale of American ingenuity and global influence, the events of October 15 trace their origins to the acampadas and asambleas of the 15-M Movement. As early as June 2011, the indignados of Puerta del Sol and Plaça Catalunya had called on their comrades in other countries to “unite for global change” on this day. Timed to coincide with a meeting of ministers from the Group of 20 wealthiest nations in Paris, the “15O” manifesto urged indignants everywhere to “take to the streets to express outrage at how our rights are being undermined by the alliance between politicians and big corporations.” In the four months since, the manifesto has crisscrossed cities, countries, and continents by word-of-mouth, social media, online communiqués, and a sophisticated network of “international commissions.”2

Figure 5.1 “Cattle pens” in Times Square. October 15, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

Here in New York City, the occupiers are raring for battle. Fresh from Friday’s victory over Mayor Bloomberg and Brookfield Properties, the coordinators are preparing to take the occupation to new terrain. An ad hoc October 15 coordinating committee has planned a day and night full of surprises: Move Your Money flash mobs to shut down bank branches downtown; virtual letter bombs to “occupy the boardrooms” of those banks; feeder marches to converge from all sides in a mass march on Midtown.

Over the course of the day, the city will see more than a dozen street actions and satellite assemblies, spanning seven sites and embracing three boroughs: from Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn to Fordham Plaza in the Bronx and from Wall Street up to Times Square, by way of Washington Square. Secretly, organizers have also planned an unpermitted “afterparty”—code for the taking of a second park in downtown Manhattan. It will be the first of many (failed) attempts at “expansion” and “escalation” leading up to the eviction of OWS, exactly one month later, from its home in Liberty Square.

Downtown, the day’s direct actions commence with a “run on the banks.” As one band of occupiers descends on a Chase bank on Broadway, another swarms into a Citibank branch in the heart of New York University’s West Village campus. Many of them are heavily indebted students from N.Y.U. and other area universities, here to close their accounts with Citibank. The bank’s managers promptly lock all twenty-four protesters inside the bank—“This is private property,” they say, “you are trespassing”—until a contingent of white shirts arrives to make the first mass arrest of the day.3

We get word of the arrests in Washington Square Park, where an “All City, All Student Assembly in Solidarity with Occupy Wall Street” is in full swing under a brilliant autumn sun. Emboldened by the citywide walkouts of recent weeks, as many as 2,000 students have crowded into the park to listen to speakers from five area universities inveigh against their administrators, their employers, and their moneyed lenders, and to discuss prospects for “outreach, occupations, and student strikes.” Similar scenes are reportedly playing out on over 160 campuses in twenty-five states across the country.4

The students are now joined by thousands more who have made it uptown from Liberty Square, chanting, “Wall Street, no thanks! We don’t need your greedy banks!” An impromptu dance party ensues, to the beat of bucket drums and tambourines. Next, galvanized by the news of the run on the banks—which speedily circulates through the assembly via tweet, text, and mic check—hundreds march south to the LaGuardia Place Citibank to support the detainees. “Let them go!” cries the crowd. “Stop these unlawful arrests!” The pleas go unheard, as two police vans speed away with their human cargo.

At 3:30, we spill out onto the Avenue of the Americas, where we begin the two-mile march to Times Square (see Figure 0.1). While there is an element of the familiar to all of this, there is also an element of tactical innovation in evidence. By the time the police have successfully contained us—with orders to “remain on the sidewalk!” and to “please get off the street!”—we have taken, not one, but two sides of Sixth Avenue, sending chants echoing back and forth and marchers circulating to and fro.

The coordinating committee for the day has planted trained personnel throughout the mass of marchers: “ushers” to give direction, “pacers” to set the tempo, and “scouts” to see what’s around the corner. Others are tracking police movements over the airwaves, while still others are monitoring the live streams and live tweets from a small war room they have rented in the Bowery. Behind the apparition of total spontaneity, then, there is an elaborate and increasingly well-oiled operation at work.

To be sure, many of the thousands thronging the streets of Midtown Manhattan today are new to political protest. Their homemade signs and homegrown chants testify to long-repressed passions, deeply felt grievances, and very real fears for the future: “Wall Street Is Stealing My Future.” “My Future Is Not Yours to Leverage.” “No Benefits. No Job Security. No Promotion. No Future.” “I Am an Immigrant. I Came to Take Your Job. But You Don’t Have One.” “I Am a Veteran! I Pay My Taxes! I Am Employed! I Am Sick of the War on the Poor and Middle Class.” “I Can’t Afford a Lobbyist, So This Is My Voice.” Along with the self-made signs, some of the marchers hold aloft the latest issue of The Occupied Wall Street Journal.

“The Most Important Thing in the World Right Now,” reads one headline.

We advance along both sides of the Avenue of the Americas behind the stars and stripes and a blue banner reading “REVOLUTION GENERATION,” interspersed with the flags of Spain, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the Workers’ International of old.

“Get up! Get down! Democracy is in this town!” chants a contingent of CUNY students as they rise, fall, and shimmy to the rhythm of an improvised marching band, headed up by a young black man in a hard hat beating a big bass drum.

“Party in Times Square!” announces a bald, middle-aged white man, a local public school teacher, to anyone who will listen. Today, at least, it seems many New Yorkers are prepared to lend a sympathetic ear.

Flyers, pamphlets, and Journals exchange hands by the thousands as we continue north through the mixed-use, mixed-income neighborhoods of Chelsea and the Garment District. More than a few Manhattanites emerge from their homes and their shops to cheer us on, waving, whooping, and pumping their fists in the air. A few are so moved that they leave the sidelines to join us at the front lines.

The action at the front lines is about to take a dramatic turn as the march nears the so-called Crossroads of the World: Times Square. For municipal managers, still smarting from the showdown over Zuccotti Park, are in no mood to give the occupiers the right of way. The NYPD, for its part, has prepared for this day with riot gear, cattle pens, and draft horses from its mounted unit, along with hundreds of rank-and-file officers mobilized from precincts around the city.

As we march into Midtown West, we are greeted by the targeted arrests and aggressive crowd control tactics that have become the hallmarks of the police response to such days of action. First, five white men in hoodies and Guy Fawkes masks are detained near Herald Square for violating New York’s 1845 Mask Law.

Next, a “snatch squad” tackles a tall black man in a blazer and a head wrap, who has been keeping time as a “pacer” at the very front of the march. The twenty-one-year-old will be charged with disorderly conduct for jaywalking across 37th Street.

When we reach the Bank of America Tower at 42nd Street and Bryant Park, after two miles and two hours of marching, we find our way forward blocked by a detachment of blue shirts and a mobile barrier of orange mesh. We then dash down an unobstructed side street, only to run into a wall of riot police with their batons at the ready.5

The sun sets over the Hudson River to the west, leaving only the light-emitting diodes of animated billboards projecting images of affluence, the brand-name marquees broadcasting the latest in consumer culture, and the towering temples of commerce promising visitors the world: “Open Happiness.” “Get Your 15 Seconds of Fame.” “You Already Know You’re Gonna Love It!” On ordinary days, this place is an open-air showcase for all that corporate America has to offer, but October 15 is no ordinary day.

Today, up to 20,000 occupiers will stream into the square from all sides, claiming the terrain of the square for themselves, not as consumers, but as political creatures possessed of the right to assemble.

The words of the intruders echo from corner to corner, cattle pen to cattle pen, and then outward, to the world, via text and tweet, the live stream and the nightly news.

“Times Square was very powerful,” remembers Diego Ibanez. “We had people in cafes, in restaurants, saying, ‘Oh my god! What’s going on?’ Shutting their computers and coming out. That was transformational . . . know[ing] that the actions you’re doing are impacting the status quo, are affecting the conditions in New York City—which affect the conditions all around the world. Whatever we do here has ripple effects.”

Alongside the sincerity of the slogans and the seriousness of the pleas for global change, there is also an air of the carnivalesque about this convergence, the sense of a world turned upside down. Beneath the fluttering flags of the “Occupation Party,” there are zombies in bloody body paint and superheroes in spandex, come to do battle in the streets of Midtown; revelers in ball gowns and tuxedos, one of them in a pig’s head calling himself “Wally the corporate hog, ready to eat your slice of the American pie”; a “Hungry Marching Band” playing old labor anthems; and, later on, a hundred sparklers lighting up the night amid a rousing rendition of “This Little Light of Mine.”

Meanwhile, a standoff ensues on the northeast corner of 46th Street and Seventh Avenue. It is on this corner that a critical mass of occupiers takes it upon itself to rush the barricades and, for the first time in OWS, to push back forcefully against the police. In so doing, they also push up against the outer limits of traditional civil disobedience.

As Tristan will tell me after the fact: “They barricaded us in, and we were like, we have to step it up. We just mic checked. We didn’t ask the crowd for consensus. We were just like, ‘Mic Check! We’re going to rip down the barricades! If you want to help, step up! If you can’t get arrested, step back.’ And we just ripped down the barricades.”

I am standing a few paces back from the front, but I can hear the words of incitement and the surge of excitement from the militants (most, but not all of them young men) as they “mask up” and move with determination toward the skirmish line:

“Mic check! Mic check! Push! Push! Yo, push through!”

I hear the metallic clang of the cattle pens going down, the frenzied cries urging, “Take it! Take it!” and the police orders to “Move back! Move back or be pushed back!”

At this point, the riot police fall back, making way for the elite mounted unit to move in. Eight blue shirts charge in on horseback under the command of a single white-shirt, taking up positions along Seventh Avenue and turning to face the surging crowds as vehicular traffic slows to a crawl behind them.

At first, they are fifty feet ahead of me—then thirty, then fifteen—until, to my dismay, I find myself face-to-face with a pair of boots, a billy club, and a 1,200-lb horse. The animal has terror in its eyes and a tremor in its hooves—as do I—for its rider is spurring it on, deeper and deeper into the now petrified mass of protesters.

There is no time to think, no room to maneuver, no place to hide. All means of egress have been blocked off by a solid wall of humanity. Thus reduced to a state of primal fear, all I can think to do is to keep my camera rolling, keep my head on straight, and keep myself from falling before the onslaught.

“Where shall we go?” I hear an older man wail, his voice shaking with high emotion. “Where do you want us to go? We have nowhere to go!”

Others cry out, “Shame! Shame!” “The whole world is watching!” “You’re hurting people!” “You’re gonna kill someone!” Within minutes, the exclamations of shock and awe turn to vigorous efforts at moral suasion:

“This! Is! A nonviolent protest! This! Is! A nonviolent protest!”

After ten minutes of terror—minutes that feel like hours—one of the riders loses control of his steed, falling headlong from his saddle and emerging, somehow, unscathed. At last, the order comes for the mounted unit to retreat, as a battalion of riot police moves in, this time hundreds strong, armed with a fresh supply of cattle pens and orange mesh.

I have had enough of the action for the time being, and so I make my way through the shell-shocked crowds to the safety of the Rosie O’Grady Bar. As I nurse a beer with fellow survivors, we follow the ongoing battle for the streets on OccupyWallSt.org:

8:00 p.m. Police are arresting occupiers at 46th and 6th.

8:08 p.m. Tension escalating, police ordering protesters to step away from barricades.

8:30 p.m. Scanner says riot cops in full gear, nets out, headed to the crowd.

9:02 p.m. Forty-two arrests on 47th.6

Austin Guest, one of the arrestees and a member of the Direct Action Working Group, recounts how the final battle unfolded:

This police line was pushing people down the sidewalk. . . . We turned around, and then they pushed us more. And we linked arms, and they pushed us again. There was this ninety-year-old woman who was waving a copy of the Constitution in the riot cops’ face. And they pushed her, and she fell down this stairwell. And everyone was so outraged. And so I took this copy of the Constitution, and I mic-checked the First Amendment. We wound up chanting at the top of our lungs, over and over, “Congress shall make no law. . . .” At some point, they decided they’d had enough of that, and they kettled and arrested us all.

Meanwhile, early on the morning of October 16, Occupy Chicago’s embryonic encampment at Grant Park was the subject of a preemptive strike, ordered by Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Police Chief Garry McCarthy. Accompanied by members of the National Nurses Union and the Chicago Teachers Union, the occupiers had marched from the Chicago Board of Trade to a general assembly at the edge of Grant Park—not far from the site where Barack Obama had given his victory speech on November 4, 2008.

When a group of occupiers announced their intent to occupy the park past the city’s 11:00 p.m. curfew, and erected forty tents in a circle, they found themselves surrounded by officers of the Chicago Police Department, clad in black, with zipties at the ready and floodlights in position. Hoping to hold their ground until the curfew was lifted, the occupiers locked arms to form a human chain around their would-be home.

One by one, they would be led (or carried) away in cuffs to waiting buses, to the tune of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” and chants of “The Whole World Is Watching!” When asked about the arrests, Mayor Emanuel would answer, “There’s a very specific law. . . . We have to respect the laws and we have to enforce them.”7

“Occupy Chicago was different from most occupations in that we never had a camp. We wanted what Wall Street had . . . [but we were] denied from the beginning,” notes David Orlikoff, then a student activist at Columbia College, who spent his first night in jail on October 16. “We were going to occupy Grant Park. . . . The police waited until the media left before they started making arrests. It was just dramatic, standing with a line of people, crossing arms, staring at a line of police holding clubs and scary equipment. It demonstrated that we live in a police state.”

Police state or not, Mayor Emanuel was determined to prevent a new Liberty Square from taking root in Chicago, ahead of the G8 and NATO summits slated to take place in the city that spring. The following Saturday in Grant Park, the CPD and the Windy City occupiers would stage a repeat performance, to the tune of 130 more arrests.8

Even as they were fighting a losing battle for the streets, by the third week of October, it seemed the occupiers were winning the battle of the story. In the words of a leading Wall Street occupier, “We were like . . . oh my god, we’re owning this narrative right now.” For the 99 Percent movement was now not only occupying the streets and the squares of urban centers, it was also beginning to occupy the national stage, appearing to exert an unexpected and outsized influence on public opinion and political discourse.

Having attracted the attention of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in early October, the occupiers would now win the ear of President Obama himself. In an address on October 16 and an interview on October 18, the president tactfully expressed a degree of sympathy with the aims and claims of the 99 Percenters, asserting that, “I understand the frustrations being expressed in those protests,” and arguing that “the unemployed worker can rightly challenge the excesses of Wall Street.”

Even the Republican Party’s would-be presidential nominee, Mitt Romney, who had earlier sought to cast the movement as an instance of “dangerous . . . class warfare,” increasingly felt compelled to adopt its rhetoric, claiming, “I don’t worry about the top 1 percent. . . . I worry about the 99 percent in America.”9

Less than a year after the 2010 elections had swept the Tea Party Right to power, OWS was already proving, by some measures, more popular with American publics than either Congress or the Tea Party. In a Pew/Washington Post poll conducted on October 20–23, four in ten respondents would express support for the occupiers—including one in two Democrats, nearly one in two independents, and one in five Republicans—while one-third of those surveyed stood opposed. For all the efforts to tar the occupiers as a 21st-century “mob,” a “youthful rabble,” or the province of “lefty fringe groups,” they seemed to have struck a chord that, to their own surprise, was resonating with millions of 99 Percenters across America—as it was reverberating, too, around the world.10

Over the course of its first month, OWS had expanded, then exploded, far beyond anything its organizers could have expected or imagined. As the ranks of the occupiers swelled and the scale of the occupations grew, so, too, did the operational needs and the logistical challenges of the counterinstitutions that served them. The occupiers were presented with pressing problems of coordination and communication—both within the occupations (intra-Occupy) and between the occupations (InterOccupy [or “InterOcc”]).

There were ever more moving parts to Liberty Square, as there were to each of the occupations. Such parts were continuously multiplying and dividing, seemingly by the day, as new working groups formed and spun off to form “autonomous collectives”—while remaining, for a time, under the auspices of the GA. “Operations groups” claimed essential roles and functions within the occupation itself, while “thematic groups” took their place in larger projects of movement organization and social transformation.

By week 3, there were over thirty working groups registered with the NYCGA alone. By week 5, that number would more than double to approximately seventy. Alongside the more active members of the working groups and affinity groups was a growing population of unaffiliated participants, who came to the square as “autonomous individuals.” Adding to the influx of occupiers was the inflow of donations to the Friends of Liberty Plaza and the Occupy Solidarity Network. According to the NYCGA Finance Committee, on Occupy’s one-month anniversary, its total assets exceeded $399,000.11

Between the “mic checks” and the bank checks, there was trouble brewing in Liberty Square’s little concrete utopia. Early on in the life of OWS, the GA model had proved to be a workable mode of democratic decision-making, as least with respect to matters of practical and political consequence to the occupation as a whole. The GA, in the words of one facilitator, was “the heart of our movement, . . . an institution that can provide vital political discussion and diverse input on movement-wide decisions.”

With its vision of a vibrant democratic life to be practiced out in the open—in which anyone could participate and no one would dominate—the NYCGA had served the occupiers not only as a site of self-governance, but also as a source of legitimacy and a ritual of solidarity for an otherwise divided movement. At the same time, the GA was also the sole decision-making body with the authority to allocate funds. As the occupation attracted growing concentrations of people and resources, the GA, more than a place of cooperation, became a place of competition over this unanticipated surplus.12

As OWS entered its second month, I could sense a deepening rift between those generally assembled in the square and those participating in the working groups, where much of the day-to-day work was carried out. By late October, certain working groups had withdrawn their participation completely from the GA, retreating from the space of the square to satellite sites like the Deutsche Bank atrium at 60 Wall Street.

When facilitators conducted a listening tour, they were confronted with a litany of grievances. Working groups found “little space in the GA to effectively communicate their needs.” They complained that “decisions take so long to be made . . . that there is insufficient time to address the many needs of our working groups,” let alone to “build trust and solidarity” or to share “broader political and community visions.” The most common complaint of all involved the lack of transparency and accountability with respect to the GA’s purportedly public funds. Every participant wanted a piece of the communal pie; many groups felt that they were receiving less than their fair share.13

Meanwhile, outside the purview of the GA, and in the absence of a more formal means of coordination, core occupiers had evolved a set of informal mechanisms in their stead. Some such mechanisms were publicly accessible and democratically accountable. For instance, there was the morning “coordinators’ meeting” at Trinity Church, which served as a reliable venue for “reportbacks” and “check-ins” among the working groups.

Other forms of coordination emerged from behind closed doors, where ad hoc “affinity groups” met in secret to “make things happen.” The most influential of them met regularly in a private apartment on the Lower East Side. Its membership was made up of some of the most socially networked occupiers and the most politically skilled organizers. Many of them already played lead roles in the core “operations groups” of OWS, such as the Media, Facilitation, and Direct Action working groups. Others played the role of connectors between affinity groups, working groups, and movement groups.

Even those who played a decisive role in such operations would later come to acknowledge their role in the making of what one occupier called the “ruling class of Occupy.” “There was the ruling class and then the not-so-ruling class, the ‘mere plebeians,’” says Cheryl, of the POC Working Group. “A lot of folks with social capital ended up corresponding with folks who had other forms of capital, like money, or access to funds. We had created another society and we had created our own class strata.”

From Lower Manhattan to London, this was to be a recurring theme in many of my interviews. “This is really a reflection of society here,” says Joshua Virasami, a young Englishman of South Asian descent, who had quit his job as an engineer to devote himself to Occupy London. “And therefore it reflects everything society has. . . . Male domination, white supremacy . . . that the white voices hold more authority. That was all there. . . . [And] class reproduced itself like that in the camp. People took on their class roles. Like, ‘I can’t do finance. I’ll go and do the kitchen.’ People thought that they [had] to do jobs that society led them to believe that they should be doing.”

“Here’s the secret,” adds Isham Christie of the original NYCGA, whom we first encountered in Chapter 1. “There was a shadow government. There quickly became different circles of legitimacy and power. . . . The affinity groups, sometimes they were just a group of people who liked each other, and were doing a lot within Occupy. Some people were driving more of an agenda. There definitely was an informal leadership that had no responsibility to anyone else.”

With a growing backlash in the GA against this “informal leadership,” this “shadow government,” the Facilitation and Structure working groups finally moved to bring the decision-making process out into the open. Thus began the ill-fated “spokescouncil campaign” of late October. Facilitator Marisa Holmes led the charge, making her case before an increasingly hostile GA: “A lot of our working groups are having difficulty communicating and coordinating. . . . The spokescouncil model we are proposing allows us to keep our culture, but to also make logistical and financial decisions for OWS.”14

The spokescouncil model was an inheritance from the alter-globalization, anti-nuclear, and other direct action movements.15 In principle, the spokescouncil—so-called because its physical form resembled the spokes of a wheel—was envisioned as a “confederated direct democracy,” in which each group would send a rotating, recallable “spoke” to confer with other spokes and to convey the will of their group to the larger body. It was hoped that the council would complement the GA by more effectively coordinating between committees and caucuses—and by taking over the everyday operational and financial decisions that the GA was incapable of making on its own. Access would, in theory, be open to all, with amplified sound, signing, and live streaming to “allow everyone to follow the discussion, participate through their spoke, and ensure that their spoke correctly communicates the sentiment(s) of their group.”16

On Friday, October 21, I joined hundreds of occupiers on and around the stone steps of Liberty Square, a few paces from a growing tent city, for a fractious forum on the merits and demerits of the spokescouncil proposal. Though the proposal had already won the support of a supermajority of occupiers—having been “workshopped” in three successive GAs and in five open meetings—its introduction met with staunch opposition from the more ardent anarchists, who were convinced that a spokescouncil would permit an undue centralization of power in the hands of the few. After five hours of heated debate, fifteen occupiers opted to block any attempt to restructure OWS, citing “serious moral concerns,” a critique of “invisible leaders who are misusing their roles,” and an appeal to the GA as the “legitimate voice of this movement.”17

It would take another week of “teach-ins,” “listening tours,” and pro-council propaganda before the assembly finally approved the proposal, 284 to 17. On Friday, October 28, as night fell frigid over Lower Manhattan, 300 of us endured a messy, often maddening exercise in hyper-democratic deliberation. The skeptics again sought to defer any decision with a seemingly endless succession of questions and concerns:

“Will distribution of resources be honest, fair, and transparent?”

“Will spokescouncils be inclusive of people who work or have limited time?”

“I am an anarchist. I’m concerned we are creating a hierarchical system.”

“I am concerned with the exclusion of a large segment of the groups here.”

Following seven hours of back-and-forth, punctuated by periodic disruptions, the process was coaxed to a conclusion by the facilitation team: “We cannot reach consensus here. . . [but] there are hundreds who are frustrated and want to vote.” By 2 a.m., the NYCGA had rendered its verdict, placing its hopes in the democratic promise of the spokescouncil. But these high hopes were soon to prove tragically misplaced.

Others of Occupy’s most skilled networkers got to work on another, equally ambitious project: a trusted system of communication and coordination that would link general assemblies and working groups across the country. The new system, which they called InterOcc, would prove to be one of the most critical links in the Occupy network. Dozens of occupations, spanning nearly every state of the Union, would come to depend upon its weekly conference calls and open-source infrastructure. The calls began as information sessions and informal conversations, but within weeks they would evolve into vital venues for joint action planning, shared messaging, and resource sharing.

Prior to InterOcc, communication from occupation to occupation had been haphazard and ad hoc. The occupiers of town squares and city parks, beyond Liberty, had been largely left to their own devices, save for steady streams of social media and a handful of specialists willing to share their know-how.

“Most of the people who started occupations just did it of their own accord,” says Justine Tunney of OccupyWallSt.org. “I was in contact with some of them, and I would try to help a bunch with setting up websites and stuff, but that’s pretty much it. We were just so busy [and] understaffed. . . . So, dealing with connecting all the occupations, I don’t think that was handled effectively until the Inter Occupy Working Group came out.”

When I asked a key player in InterOcc why it took so long to form a national network, she offered a more cynical answer: “No one in New York gave a damn about the rest of the country. Everyone in New York thought they were the movement.”

Still, the national stage was beckoning. The day after the October 15 Global Day of Action, InterOcc was born in Liberty Square. Its first meeting was attended by all of five occupiers from the Movement Building Working Group. What with the movement’s explosive growth and the escalating police response, these “movement builders” felt it was imperative to establish a line of dialogue between occupiers at a distance.

“We wanted to connect everyone around the country who was doing this,” says Tammy Shapiro, a young white woman, originally from a suburb of Washington, D.C., who coordinated the first conference calls. “But people didn’t want New York to be the leaders. . . . Everyone was so scared of this national thing, that it was going to be this hierarchical level of people trying to direct things. But at the same time, it wasn’t going to happen unless we did it. The idea was that we would be a neutral team to help people communicate and coordinate, but we were not going to be doing the coordinating.”

On the night of October 24, the networkers facilitated the first of the weekly conference calls. For technical assistance, they turned to a sympathetic startup called Maestro, which offered “social teleconferencing” technology that replicated, in real time, the form of a GA. Fingertips on keypads substituted for hand signals, while virtual “breakouts” stood in for working groups. Participants in Occupy Philly went on to propose the formation of “committees of correspondence” (CoCs), which would serve as “conduits for internal communication” between occupations. The CoC model added appreciably to the volume and density of ties in the network.18

The next call, on October 31, drew hundreds of participants from forty-three occupations and twenty-four states. Participation was not limited to the traditional hubs of radical politics. Some of the most active participation came from “outside of the big cities,” Tammy remembers. “People from Kalamazoo, people from rural Indiana, people from rural New York—InterOcc was the thing that allowed [them] to connect.”19

While the first call had centered on the discrete actions, needs, and assets of local occupations, the second call turned to prospects and proposals for coordinated “national days of action.” Higher levels of coordination would enable occupiers in diverse locales to share best practices, tactics, targets, and talking points. The hope was that, in “scaling up” the movement’s mobilizations and its modes of organization, the whole would prove greater than the sum of its parts. At the very least, it would prove to be more enduring, as the InterOccupy network would go on to outlive the occupations that had birthed it.20

While they seemed to be winning the battle of the story—for now—the occupiers were already beginning to lose control of the squares and the streets. In the urban police forces of post-9/11 America, they faced powerful and well-appointed adversaries, increasingly prone to shows of overwhelming force. On analysis, their adversaries appeared to share a set of basic operational objectives: first, to contain the occupations within the bounds prescribed by state managers and private-sector stakeholders; second, to control the occupiers’ movements, both within the squares and in the surrounding streets of the financial districts; third, to safeguard private and public assets against the threat of insurgency; and fourth, to reassert the sovereignty of municipal, state, county, and federal institutions, over and against the occupiers’ claims to autonomy and free assembly.21

Of all the enforcement actions that October, the eviction of Occupy Oakland (OO) was unrivaled in its ferocity, its intensity, and its quasi-military character. By October 20, the city’s municipal managers had retreated from their initial position of support and revoked their permission for OO to occupy the plaza overnight.

Two days earlier, Deputy Police Chief Jeffrey Israel had conveyed his position to City Hall staff: “We can either wait for the riot. . . or order them to cease their night time occupation and be ready to enforce the order. . . . I think a rather firm message. . . must be communicated to them.” Tellingly, too, officials had reported receiving “inquiries” from Bank of America and Kaiser Permanente, one of the city’s largest employers, “regarding the City’s position on the Occupy movement.” Others had detailed a pressure campaign by the Chamber of Commerce urging them to take action against OO.

On the evening of the 20th, the Quan administration issued a “Notice to Vacate,” concluding that “this expression of speech is no longer viable” and proclaiming that public assembly in the plaza would henceforth be restricted to the hours of 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. In support of their claims, they cited a familiar catalog of complaints: sanitation issues, fire hazards, health code violations, charges of violence and vandalism, and denial of access to police and other City personnel.22

The occupiers of Oscar Grant Plaza responded to the “Notice to Vacate,” along with subsequent “Notice[s] of Violations” and “Demand[s] to Cease Violations,” with characteristic defiance. Some made a public show of burning the eviction notices in the midst of the camp. Others made plans to regroup and reoccupy in the event of an eviction. That Saturday, thousands staged an unpermitted march through downtown Oakland and around Lake Merritt, calling on participants to “Occupy Everything! Liberate Oakland!” The “anti-capitalist action” culminated in a short-lived occupation of a Chase branch on Lakeshore Avenue, in which a spirited flash mob charged into the lobby, danced about, and scattered stacks of deposit slips to the wind.

Meanwhile, the Oakland Police Department (OPD) was already preparing for war. With the OPD understaffed and unable to execute the operation alone, city officials secured the “mutual aid” of fourteen other agencies, including nine local police departments, the California Highway Patrol, and the Sheriff’s Departments of Alameda and Solano Counties. The officers came equipped with riot gear, “less-lethal” munitions, and chemical agents such as CS gas.23

The first raid on Oscar Grant Plaza unfolded during the early-morning hours of October 25. As OPD officers sealed off the area and directed journalists to a designated “Media Staging Area,” a long column of riot police, 600 strong, moved in to neutralize resistance. The occupiers sought to activate their emergency response network—“Get here immediately,” they urged—but it was too little, too late. To a soundtrack of wailing sirens, desperate drumbeats, and the occasional projectile (a kitchen utensil here, a tear gas canister there), the riot police roused the 300 remaining residents from their slumber and ransacked the 150 or so habitations arrayed around the plaza.

A total of eighty-five occupiers would be placed under arrest, led in zipties through the still-dark streets as clusters of supporters gathered on the other side of the police lines, chanting, “Let Them Go! Arrest the CEOs!” By 5:30 a.m., the OPD had declared the plaza “contained.” Tuesday dawned on a scene of devastation around Oakland’s City Hall: torn-up tents, broken furniture, and overturned tables littered the plaza, some still stacked with fresh food and medical supplies, others draped with banners reading, “RECLAIM DEMOCRACY” and “FIGHT THE POWER.”

Word of the eviction spread like a California wildfire across the San Francisco Bay, by way of word-of-mouth as well as social media channels. The radical core called on all occupiers and supporters to reconvene on the steps of the Oakland Public Library at 14th and Madison at 4 p.m. Behind a large canvas proclaiming the birth of the “Oakland Commune,” a visibly multiracial, intergenerational crowd of some 700 gathered to express their outrage at the events of that morning.

A clean-cut man of color in a Navy hoodie intoned, “They can take our tents. They can take our food. They can take our books. But they cannot take Oakland’s spirit.”

A dreadlocked young black man insisted, “I am an American citizen. I would like to be protected and served, not shot at and beaten.”

An older, well-dressed black woman spoke in plaintive tones: “My heart is broken and angry at what they did to our village this morning.”

Finally, Boots Riley concluded the rally with the marching orders for the day (which, he would later tell me, “somebody [had] whispered in my ear”): “It’s good that everybody’s out here. . . . We’re gonna take back Oscar Grant Plaza! Right now!”24

The occupiers then set out to reclaim their former home, led by an indignant contingent of Oakland schoolteachers bearing a “NO TO POLICE VIOLENCE” banner, and accompanied by a drummer corps and brass band playing ancient anthems from the anti-fascist resistance. “Power to the people!” they chanted with their fists in the air. “Occupy! Shut it down! Oakland is the people’s town!”

As they wound their way past North County Jail and approached OPD’s 7th Street headquarters, a mobile field force took up positions in a rolling street closure, blocking the way forward and staging the day’s first arrest. Moments later, the march escalated into a melee, with an exchange of projectiles between insurrectionist affinity groups, who pelted officers with paint, and a “tango team” of riot police, who launched beanbag rounds and tear gas canisters into the crowd. With every volley, the occupiers would disperse, coughing and choking, only to reconverge and march back around the block, until they managed to reach the perimeter of Oscar Grant Plaza.

As the sun set over the San Francisco Bay, OPD officially declared the gathering an “unlawful assembly,” warning that anyone who refused to disperse would be “arrested or subject to removal by force . . . which may result in serious injury.”25 As I and others followed the action live from Liberty Square, the streets of downtown Oakland were beginning to resemble a war zone, none more so than the intersection of 14th Street and Broadway. The ranks of the riot police and the occupiers alike continued to swell with reinforcements—the former reaching into the hundreds, the latter into the thousands.

“That’s when the infamous OPD assault occurred,” says Roy San Filippo, a longtime anarchist activist who works with the local labor movement. “The OPD is a heavily militarized police force. They had their flak jackets on, full riot helmets, gas masks. Most of them were armed with grenade-launching tear gas guns, or beanbag guns. Essentially, without warning, into what was a spirited but by no means violent crowd, OPD just started launching tear gas grenades. A lot of people . . . were quite shocked, to say the least, that they were out here in the streets expressing their anger, and what they got for it was a face full of tear gas.”

The occupiers and their supporters would hold their ground for four hours or more, from 7:00 to 11:00 p.m., as the OPD and allied agencies fired round after round of C.S. gas into the defiant crowds, using twelve-gauge shotguns investigators would later deem “unnecessarily dangerous.” Along with the standard-issue tear gas came more contemporary “less-lethal” weaponry, with fancy names like drag-stabilized flexible baton rounds and C.S. blast rubber ball grenades.

Occupiers responded with a “diversity of tactics”—some sitting down en masse in the street, others linking arms and “blocing up,” still others dismantling police barricades, and lone wolves here and there lobbing improvised projectiles, including the smoking canisters, back at the police lines whence they had come. The use of force would steadily intensify throughout the night, as “less-lethal” munitions traced long arcs through the air, leaving their targets burning, coughing, choking, shaking.

At 14th and Broadway, the militarized forces of six area police agencies were facing off with a pair of military veterans come home from the front. The young men took up positions on opposing sides of the barricades: On one side, they stood in battle formation, outfitted with riot gear, gas masks, and weapons fit for urban warfare. On the other side, the veterans of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps stood at ease in ceremonial uniform and military fatigues, respectively, one of them waving a Veterans for Peace flag and a copy of the Constitution, the other bearing nothing but a camouflage backpack. The Naval officer, for his part, had told a friend of mine earlier that night, “I’m out here because I served two tours of duty in Afghanistan and Iraq. And I can’t bear the fact that our money is being used for these wars abroad, and not for stuff at home.” But the war, it seemed, was about to come home for Marine vet Scott Olsen, then twenty-four.

What was a U.S. Marine doing at the barricades along Broadway? “We wanted to show that Occupy’s goals were patriotic,” Olsen would later recount, “and that their freedom to speak and assemble are the freedoms we thought we were protecting while in the military.” For this, Olsen says, “I was shot in the head by an Oakland Police officer with a drag-stabilized bean bag round [40 g of lead pellets inside a sock fired out of a shotgun]. When I was on the ground, demonstrators rushed to my aid and requested medical assistance from the police. Instead of medical assistance, we got a flashbang thrown at us.” By that time, the tear gas had descended like a veil over the streets of downtown Oakland, blurring the vision of occupiers, supporters, and news reporters alike. But the cameras of OO’s citizen journalists would soon lift the veil, revealing the broken, bloodied face of Scott Olsen to a shocked and awed world.26

The next day, OO would reclaim Oscar Grant Plaza. With the city in an uproar and City Hall under siege over the events of the last twenty-four hours, the militants met with little resistance as they dismantled the fences erected to keep them out. Over 1,500 Oakland occupiers went on to hold a raucous general assembly, which would stretch late into the night. By a vote of 1,484 to 46, they passed a resolution calling for a “general strike” the following week, in protest of “police attacks on our communities” and “in solidarity with the worldwide Occupy movement”:

We as fellow occupiers of Oscar Grant Plaza propose that on Wednesday November 2, 2011, we liberate Oakland and shut down the 1 percent. We propose a citywide general strike and we propose we invite all students to walk out of school. Instead of workers going to work and students going to school, the people will converge on downtown Oakland to shut down the city. The whole world is watching Oakland. Let’s show them what is possible.27

The following Wednesday, Oakland’s workers would respond to the general strike call by the thousands, staging work stoppages, sickouts, and walkouts on a scale not seen since the city’s last general strike in 1946. Office workers and nurses, teachers and longshoremen tacitly took a day off to join the demonstrations downtown, as did the unorganized, the unemployed, and the underemployed, along with thousands of students at area high schools and universities. That night, they would shut down the Port of Oakland, the fifth busiest container port in the country.

Four organizers would later recall the scene in the streets on the day of the strike:

For Roy San Filippo, of the International Longshore Workers Union: “We developed a plan to have early morning picket lines in front of BART stations, picket lines in front of office buildings. People are less likely to go about their daily routines if they see this sort of upsurge. . . . The basic message was, the choice you make today can change everything. Every day, we make an unconscious choice to go to work and support the 1 Percent with our labor. Today you can make a conscious choice to withdraw your support.”

For Robbie Clark, of the housing rights organization Just Cause/Causa Justa: “Man, the general strike was incredible. It was just a big, political, all-day block party. We started in the morning—we did a march around education, we did some around the banks and foreclosures. . . . Then we all marched in a big contingent down to the port, and the port was shut down. There were just seas of people, it was beautiful. All the people we were building community with. All in the name of wanting a new society, you know?”

For Boots Riley, of the revolutionary hip-hop collective The Coup: “We had a plan of shutting down the port that night . . . putting forward the idea of withholding labor. We didn’t really know how many people were there until we crossed over that ramp, and we saw all these people, I mean, tens of thousands of people. And I was like, oh shit! This is the biggest thing I’ve ever been involved in. . . . And a lot of people in the march were dockworkers, were I.L.W.U. members who weren’t at work, who were coming there to do this port shutdown.”

For Yvonne Yen Liu, of Occupy Oakland’s Research Committee: “We were so overwhelming in numbers, there was never any issue of anyone being in jeopardy. . . . People of all ages were there. All of Oakland was there. . . . It just felt like a festival. It felt like all of the city had decided to come out and celebrate us winning, and taking over. Asserting that this was our city, and that the police couldn’t treat us this way and get away with it. Yeah. It was a beautiful day.”

Mayors and police chiefs in nearly every major metropolis in the United States were increasingly preoccupied with the question: How to dispense with the occupations without making martyrs of the occupiers, and without making themselves the targets of public ire? What they required was a satisfactory pretext that would lend their actions an aura of inevitability. Many would find the pretext they sought in the escalating crisis within the camps, which was growing ever more acute with the falling temperatures, rising tensions, and increasing casualties.

Administrators had justified early anti-Occupy offensives, as we have seen, on ambiguous grounds, such as unsanitary conditions or unspecified public health hazards. Now, the evictions could be justified on the basis of very real acts of violence which were being reported by the occupiers themselves, from vigilante attacks and brutal beatings to sexual assault and, in at least two instances, rape. Amid the rise of the tent cities and the influx of new residents, the spaces of the squares were growing increasingly unsafe, slipping out of the control of the general assemblies, working groups, and coordinator classes. Many of the campers were either unwilling or unable to police their own. The mechanisms they put in place—security patrols, “de-escalation” teams, “safer space” initiatives—were proving woefully inadequate to the task of securing the camps.

Municipal managers and police agencies, for their part, were pursuing a policy of planned abandonment, enforcing only those laws pertaining to the time and manner of public assembly, while failing to provide for the safety of the denizens of the squares. The one-two punch of internal insecurity and external pressure combined to increase the costs and raise the risks of encampment, especially for female-identified occupiers, transgender activists, and other traditional targets of violence.

Between late October and early November, says Laura Gottesdiener, a young, white volunteer worker with the People’s Kitchen, “I watched it go from, like, 50 percent women to, like, 5 to 10 percent women living there. There was the idea that, as long as we can accept everybody, then everybody will be welcome. But we didn’t think, like, who will opt out of this space? We all went to the women’s bathroom at McDonald’s every morning. And I would hear conversations between women, like, ‘I don’t know if I should stay here.’ ‘I don’t know if I can keep doing this.’”

Meanwhile, the old demons of the conservative imagination had come roaring back to life in the form of “freeloaders” and “predators” alleged to be “occupying the occupation.” I watched in dismay as both the occupiers and their adversaries resurrected and reenacted the old offensives against the elusive enemies of public order: the War on Crime, the War on Drugs, the “Quality of Life” campaign. Their targets were a familiar lot from an earlier era: the addicted and the troubled, the homeless and the penniless, the wretched refuse of the urban centers, forsaken by a gutted welfare state.

“In a place where the inequality is so stark, and the homeless problem is so huge, well, of course that was going to happen,” notes Heather Squire of the People’s Kitchen. But many in Yet, the upper echelons of Occupy were growing more hostile to the presence of the “lower 99 Percent.” “To a lot of people, it was their personal utopia,” Heather continues. “In their personal utopia, there are no drug users, and there are no homeless people.”

Other occupiers I interviewed even reported that they had observed police officers dumping suspected drug dealers and petty criminals in and around the camps. At Occupy Philly, for instance, “The cops were telling all the city shelters, if they have extra people, to send them to occupy,” reports Aine, a well-respected community activist from Belfast who worked with OP’s security team (and whose account was verified by multiple sources). “With my own eyes, I saw cops drop off people who were dealing crack in the encampment. . . . I personally disarmed two people with knives right in front of a cop. It was pretty scary. We were essentially the ones left to police the area.”

“Overnight, we turned into a social services organization,” observes Occupy Philly’s Julia Alford-Fowler, a previously apolitical white woman, composer, and music instructor who served for a time as a liaison between the occupiers and City Hall. “It’s like, welcome to the revolution! Now you have to provide mental health care to the entire city! With the amount of time and preparation we had. . . we didn’t stand a chance.”

Back in Liberty Square, organizers hoped to deal with the crisis in the camp by way of “expansion.” “We decided that we should expand . . . to alleviate some of the pressures, and to reorganize ourselves,” says Diego Ibanez of the People’s Kitchen, who would later face jail time for his efforts. “I think about it now—we were so ambitious, so ambitious. [We] were just thinking, what’s the next move, what’s the target?”

The target of opportunity was a vacant lot at Duarte Square, at Sixth Avenue and Canal, adjacent to the high-traffic Holland Tunnel. The lot was on private property belonging to the venerable Trinity Church, a sometime ally of OWS, but also an institutional real-instate investor with billions of dollars to its name. During the third week of November, Diego’s affinity group hoped to single-handedly kick off a second occupation by invading the vacant lot and winning over its owner. “We had a plan set,” Diego continues. “We had a truck full of materials, priests that were gonna do civil disobedience. Our meetings were very secret. We would put our telephones in the fridge and that kind of thing. We were paranoid. We were definitely being monitored.”

The crisis in the camps led Kalle Lasn of Adbusters to wonder aloud, “What shall we do to keep the magic alive?” He proposed a Plan B for the coming winter: “Declare ‘victory’ and throw a party . . . a grand gesture to celebrate, commemorate, rejoice in how far we’ve come. . . . Then we clean up, scale back and most of us go indoors while the diehards hold the camps.” While some occupiers concurred agreed, most were not yet willing to pack up and go home—not without a fight.28

So it went, night after night that November, each sunset auguring another onslaught against the citizens of the camps, another roundup of nonviolent resisters (see Figure 5.2). And the action extended beyond the habitual hubs of Leftist protest. Some twenty-three occupiers were busted in a twenty-four-hour period in a city park in Tulsa, Oklahoma; twenty more were led away in handcuffs from Atlanta’s Troy Davis Park, less than two weeks after their first eviction; two days later, two dozen dissidents were locked up for occupying downtown Tucson, Arizona. The following week would see more than 300 arrests at over forty eviction actions. Some of them targeted occupiers in Left-leaning municipalities like Berkeley and Portland; others occurred in more historically conservative places like Mobile, Alabama; Houston, Texas; and Salt Lake City, Utah.29

Figure 5.2 Mass arrests and mass evictions, October 10–November 15, 2011. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

Many critics of the state’s response have since alleged a vast and intricate conspiracy on the part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Yet the only evidence on offer centers on two conference calls—both convened by Chuck Wexler, director of the Police Executive Research Forum and a member of DHS’s Homeland Security Advisory Council—in which the mayors of nearly forty cities shared “best practices” before going on the offensive against their respective occupations. The reality is that we may never know how much of the crackdown was coordinated, and how much of it was simply a matter of local power players following a similar logic.30

We do know that federal intelligence agencies like DHS and the FBI have had a long record of surveillance and counterintelligence operations against anarchist, socialist, and anti-corporate activists. Since the passage of the PATRIOT Act and other post-9/11 legislation, these agencies have had multiple channels through which to coordinate such operations, from the Joint Terrorism Task Forces to the Emergency Operations Centers and the State and Major Urban Area Fusion Centers. They have also been given a mandate to work together alongside private-sector partners, in “critical infrastructure sectors” such as financial services, to ensure what they call “business continuity.” In all likelihood, the planning and execution of the raids required no elaborate plot—only the normal operation of the state security apparatus and its vast network of private partners.31

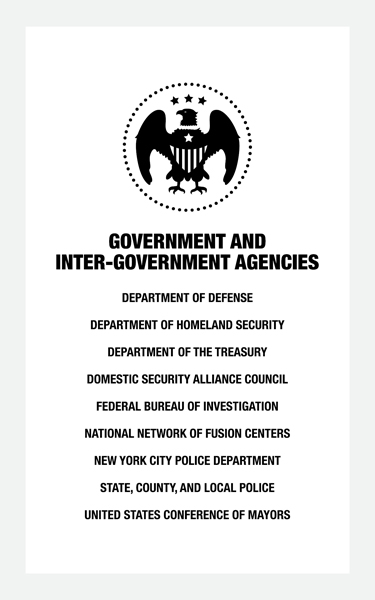

Their “alliance councils” and “advisory councils” formed in the wake of 9/11 served as vital conduits for information and resource sharing between government and inter governmental agencies, on the one hand (see Figure 5.3), and leading banks, corporations, and trade associations, on the other. DHS’s Critical Infrastructure Partnership Advisory Council, for instance, worked to “facilitate interaction among government representatives . . . and key resources owners and operators.” The Advisory Council’s Financial Services Committee included executives from Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, and JPMorgan Chase, while its Private Sector Information-Sharing Working Group comprised the representatives of fifty-one Fortune 500 companies. Among the corporations listed on its roster that year was Brookfield Properties.32

Figure 5.3 Government and intergovernmental agencies involved in policing of protest.

In the run-up to the raids, public servants appear to have worked with a special fervor to protect their private-sector partners against the threat of disruption. Just before the evictions, another public-private partnership called the Domestic Security Alliance Council had circulated a DHS report offering “special coverage” of OWS. After assessing “sector-specific impacts” for financial services, commercial facilities, and transportation hubs, the report had concluded that, “growing support for the OWS movement has expanded the protests’ impact and increased the potential for violence. As the primary target of the demonstrations, financial services stands the sector most impacted by [OWS]. . . . Heightened and continuous situational awareness for security personnel across all CI [critical infrastructure] sectors is encouraged.”33

In the early hours of Tuesday, November 15, the public-private policing of protest reached its apogee in the birthplace of OWS. As some 200 occupiers lay down to sleep in Zuccotti, while others gathered in secret in a Village church, a small army of riot police was massing along the East River, donning helmets, nightsticks, and shields. The blue shirts had been led to believe they were on their way to an “exercise.” In reality, they were on their way to evict, once and for all, the citizens and denizens of Liberty Square.34

Less than twenty-four hours earlier, the CEO of Brookfield Properties had sent another strongly worded letter to Mayor Bloomberg, demanding that the City and the NYPD “enforce the law at the Park and support Brookfield in its efforts to enforce the rules.” In addition to the usual health and safety violations, the CEO alleged that the occupation was having a “devastating negative impact” on the local business community, with employers “stressed to the point where they are forced to lay off employees” or “turn out their lights for good.” That evening, as if on cue, a group of angry business owners staged their first public counterprotest against the occupiers, alleging that “Mayor Bloomberg is helping them stay” and warning that they were “pursuing all options.”

Each of these developments undoubtedly loomed large in the mayor’s calculations. Moreover, the NYPD high command could not have been unaware of the occupiers’ plans for “expansion” the following morning, or for a day of disruption and “nonviolent direct action” in the streets around the Stock Exchange two days later.35

Still, few of us saw the raid coming. All we had heard from Mayor Bloomberg that day was the following cryptic pledge: “We’ll take appropriate action when it’s appropriate.” As it turned out, the appropriate time would come right around midnight that very night. The mayor and the police commissioner had learned some hard-won lessons since their last eviction attempt, exactly one month before. This time, they adjusted their tactics accordingly. First, the occupiers were kept in the dark until the moment of eviction. Second, the operation was executed with overwhelming force under the cover of darkness, after the news cycle and away from the cameras. Third, multiple blocks of Lower Manhattan were declared a “frozen zone,” allowing police to deny access to the public and press, and thereby minimizing potential fallout and protest turnout.36

“ZUCCOTTI PARK SURROUNDED EVERYONE TO THE PARK NOW!”

The emergency SMS alert lit up my phone at 12:59 a.m. I was out of town on a work trip at the time, but upon reading these words, I hopped in a car and drove through the night, finally reaching the Financial District just before dawn. I was lucky to have my own wheels, as the City had taken the extraordinary step of shutting down five subway lines all at once. It had also taken pains to close down half of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The wind blew in from the west, scattering scraps of litter and autumn leaves, as I walked up Broadway in the direction of Liberty Square. Somewhere, a siren announced the ongoing police operation. But the streets, at first, seemed eerily empty (see Figure 5.4). Where had all the occupiers gone? Was this how the American autumn was to end, at long last—not with a bang, but with a whimper?

Figure 5.4 Police tower rises at the foot of the Freedom Tower, November 15, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

When I finally neared the northern perimeter, I ran into a line of officers in riot gear, who were being heckled by a small crowd of angry but nonviolent New Yorkers. Pointing to my camera, I foolishly demanded my right to document the police activity.

“With all due respect, officer,” I said, “I have the First Amendment right to—”

“Move! Back!”

“Sir, I know my rights. I have the right to—”

“Move! Back!”

“But this is my city, and this is a public—”

The officer ended the exchange with a jab of his nightstick, as if to drive the point home. I was not the only photographer who would be denied entry to the frozen zone that night. Even those with NYPD-issued press credentials—including reporters from NBC, CBS, Reuters, the Associated Press, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal—were forcibly prevented from doing their jobs. At least seven would be arrested in the course of twelve hours.37

When I reached Foley Square, I found several hundred stalwarts huddled together in the pedestrian plaza, illuminated by the glow of streetlights, surrounded by a row of police. Some of those assembled had the air of refugees about them, bearing all their earthly possessions on their backs. Others had the air of defeated soldiers, having just returned from a high-risk street march up and down the length of Lower Manhattan, which had culminated in a pitched battle with the riot police at the intersection of Broadway and Pine. The stragglers spoke in hushed tones with hoarse voices, exchanging war stories or inquiring about the whereabouts of missing friends and lovers.

Meanwhile, an impromptu assembly convened to debate rival proposals as to what was to be done. To reoccupy Wall Street? To occupy One Police Plaza? To blockade Manhattan Criminal Court? Or to wait for daybreak and, with it, reinforcements? The consensus was to sit down and hold our ground in Foley Square. Somewhere, distant sirens were still wailing, warning of more confrontations to come.