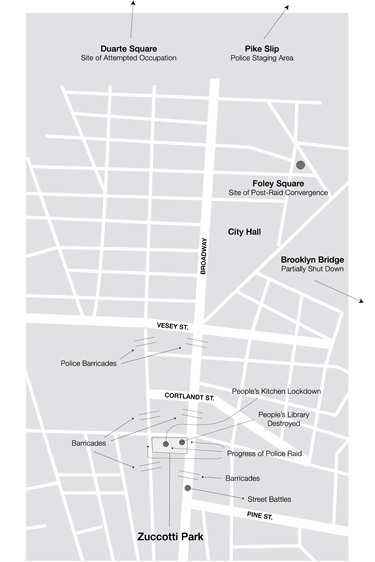

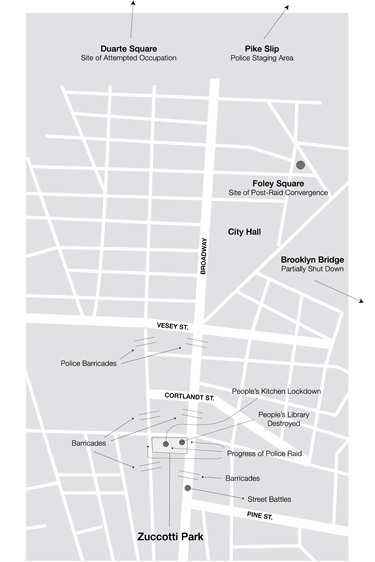

Figure 6.1 Map of the raid and its aftermath, November 15, 2011. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

November 15–December 6, 2011

Just after midnight, hundreds of riot police from across the five boroughs set out from the East River, borne by dozens of emergency vehicles bound for Liberty Square. The riot squads arrive with great fanfare, accompanied by members of the NYPD’s Counter-Terrorism Bureau, Disorder Control Unit, and Emergency Service Unit, as well as Police Commissioner Ray Kelly himself. Officers spill out of the trucks and take up positions on all sides of the park. Within minutes, they have set up metal barricades to the north and south of the square—one at Cortlandt and one at Pine—while still others guard the gates of Wall Street itself. Meanwhile, specialists set up a battery of klieg lights, which appear to turn night into day. Beside it, they position a “Long-Range Acoustic Device” to awaken the occupiers from their slumber.

At the east end of the park, beneath a black flag flapping in the wind and a sign reading, “THE 99 PERCENT WILL RULE,” a police captain with a megaphone reads from a printout on behalf of Brookfield Properties. As he does, Community Affairs officers move into the park to distribute copies of the decree:

“Attention please! This announcement is being made on behalf of the owner of this property, Brookfield Properties, and the City of New York. The City has determined that the continued occupation of Zuccotti Park poses an increasing health and fire hazard. . . .

You are required to immediately remove all property. . . . We also require that you immediately leave the park on a temporary basis so that it can be cleared and restored for its intended use. . . . You will not [sic] be allowed to return to the park in several hours.1

The message is beamed live, via GlobalRevolution.tv, to an audience of 60,000 spectators. Almost instantaneously, occupiers are circulating urgent messages to one another and to their allies internationally, by way of tweets, text loops, phone trees, and e-mail lists—all part of an emergency response system put in place after the first eviction attempt.

“WE ARE BEING RAIDED. LIVESTREAM IS DOWN.”

“Do we have cameras ready?”

“NY-ers: please head down there, show support en masse.”

“I’m sharing everywhere I can online! OMG!!”

The expected reinforcements would never show up that night, at least not in the numbers necessary to forestall the police advance. It seems that few of the tens of thousands of spectators are in a position to be anything but spectators. What’s more, many of the veteran occupiers and organizers are missing in action, having assembled off-site to prepare for “expansion.” Some are left to watch helplessly from their hiding places in private apartments and church basements, while others are held at bay behind the police lines at Broadway and Pine. “I remember the call happened, and someone said, ‘We’re getting evicted!’ recalls Tammy Shapiro of InterOcc. “It was too late to actually get into the park. We were holding down a corner, but then we got run over by the cops.”

Inside the frozen zone (see Figure 6.1), many of the occupiers, shaken by the sound and the fury of the surprise raid, opt to pack up and go without further protest. For the first forty-five minutes, the exiles can be seen streaming up Broadway, their belongings strapped to their shoulders. Everyone who remains behind, in defiance of Brookfield’s decree, will be arrested over the next three hours—142 of them in all.

Figure 6.1 Map of the raid and its aftermath, November 15, 2011. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

The police strategy is methodical, but the tactics are messy and often visibly violent. There are arrest teams of three to four officers for every occupier, their shields and batons arrayed against hands, legs, heads, and loud mouths. Some occupiers are collared simply for standing where they were not supposed to be standing. Early on in the operation, a young black man in a hoodie, doing nothing in particular, is swarmed by a large detachment of riot police. They wrest the American flag from his hands and lead him away in handcuffs. Others are arrested for resisting police orders, and these are treated with a liberal use of force. The TARU tapes will later show nonviolent resisters being vigorously beaten with batons, drenched with pepper spray, pinned to the pavement, and dragged away to waiting wagons.2

Even those trapped outside the frozen zone report being targeted and assaulted by riot police. “I was randomly running down a side street,” says Manissa McCleave Maharawal, of the POC Working Group. “And out of nowhere, a cop stepped onto the sidewalk and grabbed me and threw me against a car. I was three blocks away from the park at this time, but they had militarized the entire area. . . . There are kids who get killed for running all the time in the Bronx—but not in downtown Manhattan.”

“Why are you doing this?” observers can be heard asking of the arresting officers, while others ask, “Who are you protecting?” and urge them to “Disobey your orders!” Just before 3:00 a.m., one occupier scrawls an anonymous first-person account on a piece of looseleaf paper, and smuggles it out of the square before she is taken into custody. Her narrative reads as follows:

2:44 a.m.: “We chant, ‘You are the 99 percent’ at cops. Most tents are gone. Cops surrounding kitchen. Skirmish going on at Broadway and Wall St. . . .

2:57 a.m. Medic passing out garlic. ‘If you get pepper sprayed, bite down on clove to counteract itching.’ Two reporters say that people are coming in from Queens, Brooklyn and Harlem. Woman says police parked illegally, report to 311. Cops forming complete circle around kitchen. . . . We sing USA national anthem.”

The point of greatest resistance is the People’s Kitchen. Around 3:30 a.m., some 150 occupiers, many of them “masked up,” link arms to form their own protective perimeter. The defenders of the kitchen have three tactics at their disposal: a barricade (in which structures are placed in the path of police), a soft blockade (in which arms or legs are linked en masse), and a hard blockade (in which whole bodies are “locked down” to heavy objects). All three tactics are deployed in a desperate attempt to hold the space.

Behind improvised barricades built of scrap wood, dozens sit down arm-in-arm to form a soft blockade around the serving area, singing “Solidarity Forever.”3 Inside the soft blockade, six die-hards use bike locks to chain their necks to trees or to metal poles. The resisters manage to hold out for over an hour as they watched the riot police ransack the rest of the encampment. Finally, it is their turn to face the full force of the police onslaught. Among those who join the “soft blockade” of the People’s Kitchen is Heather Squire, who later vividly relates the events leading up to her arrest:

We saw a line of stormtroopers lining up, getting ready. So we took off and ran to the Kitchen. We just linked arms and sat down. It was just—this is what we’re doing. There was no question. And we just sat and watched all of the destruction, watched everything get torn up. For hours. It was really scary. . . . We were the last people to be arrested.

They just yanked us really hard. And they threw me to the ground, and they hit my head. I’ve never experienced anything like that before. . . . I felt like they really fucking hated us.

As the emergency vehicles move out with their quarry of arrestees, the dump trucks move in, along with crews of workmen in orange vests, dispatched by the Department of Sanitation. The sanitation crews are under special orders, and they make short work of the remnants of the encampment, disposing of everything the occupiers have left behind: tents, tarps, tables, bedding, instruments, documents, books, laptops. These items are then loaded into the waiting collection trucks and hauled away to a West 57th Street garage.

Among the casualties of the raid are 2,798 of the 5,554 books from the People’s Library of Liberty Square. The bulk of these books, according to OWS librarians, “were never returned—presumably victims of the ‘crusher’ trucks—or were damaged beyond repair. Most of the library simply disappeared. . . . The books that came back destroyed stank with mildew and food waste; some resembled accordions or wrung-out laundry.”4

Hours later, as the sun rises over the East River, we return to Zuccotti Park to find it fenced off and powerwashed, its smooth stony expanse restored to its immaculate former self. In the memorable phraseology of the New York Post’s front page, the park is “99 PERCENT CLEAN.”5 Liberty Square has vanished from sight seemingly overnight, its infrastructure dismantled, its inhabitants displaced.

The authorities appear intent not only on evicting the occupation, but also on erasing any trace of its short-lived existence. By 9 a.m., City Hall, in defiance of a court order, has dispatched dozens more officers in riot gear to guard the perimeter of the park, while Brookfield has sent in private security contractors to keep watch from within. From now on, Zuccotti will play host to a wholly different sort of occupation, while the ousted occupiers will be permanently uprooted from their one-time home.

When Heather Squire finally gets out of jail, thirty-two hours after her arrest, she remembers, “I didn’t know where to go. I didn’t have my things, didn’t have any money. I just felt really lost. . . . The world felt completely different.”

The next twenty-four hours would be a whirlwind of press conferences, court cases, and street actions, none of which went the occupiers’ way. Mayor Bloomberg, already facing a firestorm of criticism from City Council members, labor leaders, and civil libertarians, fired back that morning with a legalistic defense of his decision: “No right is absolute and with every right comes responsibilities. The First Amendment . . . does not give anyone the right to sleep in a park or otherwise take it over. . . nor does it permit anyone in our society to live outside the law.” He proceeded to lecture the occupiers that they “had two months to occupy the park with tents and sleeping bags. Now they will have to occupy the space with the power of their arguments.”6

Just before 11 a.m., one of the most influential of OWS affinity groups went ahead with its original expansion plans, hoping to upstage City Hall by kicking off a new occupation on a fenced-off parcel of Episcopal Church property at 6th Avenue and Canal. Assuring us that “there is a plan,” the plotters called on the ousted occupiers to converge at Duarte Square for what they had dubbed the “second phase” of OWS.

They came prepared, equipped with bolt cutters to break into the lot, modular structures to set up inside, banners to claim the land as their own, and barricades to hold the space against the police, along with painted shields with messages for the press:

“I will never pay off my debt.”

“I will never own a home in my life.”

As the would-be occupiers swarmed the site, proclaiming, “This space belongs to Occupy,” their one-time allies at Trinity Wall Street announced, “We did not invite any of those people in,” then promptly called the police. In the event, only a few hundred of the ousted occupiers answered the call to “reoccupy,” and only a few dozen diehards remained on the inside once the riot police showed up. By noon, all those who had refused to leave the lot had been rounded up and dispatched to “the Tombs.”7

While hundreds languished behind bars and hundreds more gathered about the barricades surrounding Zuccotti Park, members of OWS’s P.R. Working Group sought to craft a cogent response, a signal from a wounded movement to a watching world. Huddled in the basement of Manhattan’s Judson Memorial Church in the hours after the eviction, they hit on what they believed to be a winning slogan that suit the mood of the moment: “You can’t evict an idea whose time has come.” Though the substance of the slogan was subject to debate—just what was the big idea, anyway?—its message of defiance would echo around the world, from Brookfield’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. to the gates of the U.S. Embassy in London.8

Back in Foley Square, a procession of elected officials and union representatives gathered for a boisterous press conference organized by members of the City Council. One of their own, Ydanis Rodriguez, had been injured and detained during the raid, and his fellow Council members were here to “condemn the violation of the First Amendment rights of the protesters.” “It is shameful,” they argued, “to use the cover of darkness to trample on civil liberties without fear of media scrutiny or a public response.”9

Meanwhile, the battle for Zuccotti Park was already moving to the State Supreme Court. A temporary restraining order had been granted the occupiers by a sympathetic justice early that morning, only to be revoked by another justice, just before dark. In upholding Brookfield’s zero-tolerance policy, Justice Stallman ruled that the occupiers “have not demonstrated a First Amendment right to remain in Zuccotti Park, along with their tents, structures, generators, and other installations, to the exclusion of the owner’s reasonable rights and duties . . . [nor] a right to a temporary restraining order that would restrict the City’s enforcement of laws.” Despite persistent questions about their constitutionality, the new rules would be allowed to stand. “Camping and/or the erection of tents or other structures” would be strictly prohibited, as would gestures like “lying down on the ground, or lying down on benches, sitting areas or walkways.”10

An hour after the judge’s ruling, Zuccotti Park would be partially reopened for “use and enjoyment by the general public for passive recreation.” Its perimeter remained ringed with barricades, guarded by officers in riot gear and contractors in green vests. A checkpoint was put in place to inspect all park-goers and their bags for signs of camping gear or contraband. Anyone suspected of entering with intent to occupy could be banned from the premises—and anyone bearing their belongings on their person was suspect. Young men of color and the homeless of all descriptions were turned away with remarkable regularity, effectively resegregating the space of the square.11

The eviction of OWS lent itself to a kind of kaleidoscope of interpretations, each one colored by varieties of lived experience, narrative strategy, and political ideology. Anarchists took the crackdown to be “a very powerful gesture by the state,” directed at “the people” as a whole and coordinated at the highest levels of government. Socialists and populists understood the eviction to be a class act, with mayors and police chiefs believed to be acting “on behalf of the 1 Percent.” “The 99 PERCENT ARE UNDER ATTACK,” read one colorful poster I saw plastered around New York City on November 15. Others, especially nonwhite revolutionaries, insisted that there was nothing new or out of the ordinary in all of this. “We deal with police oppression on a regular basis,” noted Messiah Rhodes. “For people of color, it’s like, oh, that’s news to you? We’ve been fighting this for a long time. Join the party.”

Liberals and civil libertarians tended to interpret the raids through the lens and the language of the Bill of Rights. Expressive protest, public assembly, freedom of the press—these were rights and liberties they held to be sacrosanct and inviolable. Midnight raids, mass arrests, media blackouts—these were practices they deemed unconstitutional, indeed “un-American.” Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer summed up this view succinctly the day after the raid: “Zuccotti Park is not Tiananmen Square.”

Those on the Right, for their part, tended to interpret the police operation as a justifiable use of force to tame a Far Left movement that had overstayed its welcome, having broken the law and brought “violence, mayhem, and public filth” to the streets of America’s cities. In the words of Fox News’s Bill O’Reilly, Occupy had been “overrun by thugs, anarchists, and the crazies,” to the point that elected officials had no choice but to put a stop to it. On November 16, O’Reilly became one of the first of many pundits to declare the movement “dead,” “finished as a legitimate political force in this country.”12

Interestingly, many of the occupiers I later interviewed would make the case that the eviction, far from leaving Occupy dead in the water, actually ended up giving the occupiers a new lease on life. “Obviously, the eviction was super traumatic,” says Samantha Corbin, of the Other 98 Percent. “But in some ways, honestly, the park was just so difficult to manage at the time. I was like, my god, now we don’t have to manage the park, now we can do movement work.”

Likewise, Conor Tomás Reed of CUNY believes there may have been a silver lining to the occupation ending as it did: “Who knows? If the NYPD and the City had just let Occupy stay, its own internal contradictions might actually have been more of a liability than being ousted when it was. . . . The eviction helped furnish the mythology of Zuccotti Park.” From now on, that mythology would become yet another source of solidarity, to be rewritten, reworked, and reenacted in story, imagery, and performance.

On November 17, just two days after the eviction, occupiers, 99 Percent sympathizers, and their union allies responded to the rising tide of repression with a show of force of their own. The “mass nonviolent direct action” would reach its highest pitch, as it had a way of doing, in the streets of the Financial District, and later at universities like the New School and in the vicinity of the Brooklyn Bridge. Hundreds would be arrested, and tens of thousands more would rally to the day’s battle cry: “Resist austerity. Reclaim the economy. Recreate our democracy.”13

Elsewhere, too, the battle would be joined in some 200 cities, as trade unionists and other 99 Percenters staged dozens of symbolic bridge blockades, declaring an “economic emergency” and demanding “jobs, not cuts.” “People became aware of it in a lot of different circles at the same time,” says InterOcc’s Tammy Shapiro. “With November 17th, the unions were doing it all over the country. . . . So we were able to say, this is happening in this city and that city. We found out which cities the unions were planning to do stuff in, and then we contacted all the Occupy groups in those cities.”14

The mass mobilization had been in the works since early October, when a coalition of labor unions from the AFL-CIO and Change to Win had partnered with national organizations like MoveOn.org and Rebuild the Dream to call for a national “Infrastructure Investment Day of Action” on November 17—all part of the unions’ “America Wants to Work Campaign.” The original idea was to leverage the “street heat” of the 99 Percent movement to “hold members of Congress accountable” and “punish those who oppose job-creating legislation”—in particular, those who had blocked the American Jobs Act and Rebuild America Act. The day of action was also strategically timed to turn up the pressure on the Congressional Supercommittee, which was tasked to come up with $1.2 trillion in deficit cuts by November 23.

For many in Occupy’s anarchist inner circle, of course, any use of OWS to push a legislative agenda was anathema. Yet even the most skeptical acknowledged the potential power of a joint day of action with the unions. Now, the wave of evictions lent the mobilization a greater sense of urgency, social relevance, and political significance.15

At face-to-face meetings and conference calls in the run-up to “N17,” leading occupiers, labor organizers, and MoveOn.org operatives had come up with a simple division of labor. In New York City, the day’s events were broken down into “breakfast,” “lunch,” and “dinner,” each with its own bottom-liners. The Direct Action Working Group’s “breakfast club” would plan militant morning actions in the Financial District, intended to “shut down Wall Street” and “stop the opening bell” at the Stock Exchange.

Later in the day, Occupy the Boardroom, the OWS Outreach Working Group, and local community allies would prepare for “lunch,” in which supporters would fan out to transit hubs across the five boroughs and “highlight the stories of those who have been directly affected by our unjust economy.” Finally, the largest unions and community-based organizations in New York would plan a citywide convergence, in which tens of thousands of workers would rally at Foley Square, march to the Brooklyn Bridge, and “demand that we get back to work.” The day would culminate in a symbolic mass arrest, followed by a “festival of light” to celebrate Occupy’s two-month anniversary.16

That morning, we massed in the thousands a few paces from Zuccotti, which remained out of reach behind metal barricades. The plan was to set out on “color-coded marches” that would wind their way from Liberty to the gates of Wall Street. Once there, clusters of affinity groups would attempt to blockade all points of entry—otherwise known as “choke points”—to the area surrounding the Stock Exchange. A “tactical team” would provide the times, places, and ongoing communication throughout the day.

“When we were coming up with this,” says Jade from Direct Action, “we looked to our comrades who threw down in Seattle in 1999. . . . They were really militant and they were also beautiful.” As I had learned at the spokescouncil the night before, participants had consensed on a set of basic guidelines: “We won’t engage in property destruction or be violent with other humans,” and “our messaging will stay on the Stock Exchange—not the city, not the cops, not the media.”

I joined the unpermitted parade as it meandered down both sides of Cedar Street, in the direction of Wall Street. Many chants I heard were a reprise of those I had heard on day 1, exactly two months ago today: “Banks got bailed out! We got sold out!” “This is what democracy looks like!” Others were more recent additions to the repertoire: “Bloomberg! Beware! Liberty Square is everywhere!”

Most of the signs I saw were hand-written, cardboard affairs, as they had been in the beginning, and their gallery of grievances had a familiar air about them: “1 Percent Buys Gov., 99 Percent Foots Bill”; “Wall $treet Gets Bonuses, the Rest of Us Get Austerity”; “Stop Gambling on My Daughter’s Future”; “Banking Institutions Are More Dangerous to Our Liberties Than Standing Armies.” Other signs, however, were more affirmative in tone and tenor, asserting the collective identity that had been forged in the occupied squares: “99 PERCENT POWER.” “WE ARE FREE PEOPLE.”

We found ourselves hemmed in by a long line of riot police, batons at the ready, at the corner of Wall Street and Hanover, but we soon found our way around them, snaking down sidewalks and past roadblocks to regroup at other intersections. At the appointed time, the mass broke down into affinity groups, linking arms and snaking their way towards the “choke points”: one on Broadway, two on Beaver, two on William, one on Nassau. I heard a veteran anarchist activist mic-check instructions to the blockaders as they prepared to disrupt the morning commute for the bankers and stock traders:

“We wanna shut down!” (“We wanna shut down!”)

“Every entrance!” (“Every entrance!”)

“So a couple hundred people should stay here!” (“. . . Stay here!”)

“The rest, go to the next!” (“. . . Go to the next!”)

For the next two hours, all six access points would be swarmed by roving clusters of affinity groups, with the goal of “flooding Wall Street” and “shutting it down.” Perhaps the most volatile flashpoints were those on Beaver Street, where I accompanied the occupiers as they took up their positions before the barricades. Once in position, they repeated a single refrain:

“Wall Street’s closed! Wall Street’s closed!”

The militants deployed a diversity of nonviolent tactics, by turns sitting down, standing up, and dancing about. Some carried miniature “monuments” to the banks’ victims, which also doubled as shields. On Beaver and New, I watched a cardboard wall go up, made of mock-ups of foreclosed homes. Down the street, I saw a group of occupiers take an intersection, dressed in medical scrubs and surgical masks, bearing shields etched with the words, “Protect Health, Not Wealth.” Others opted to communicate their message with comedic antics. I spotted one occupier-cum-Cookie Monster toting a sign reading, “Why Are 1 Percent of the Monsters Consuming 99 Percent of the Cookies?”

Now and again, white shirts would dive into the crowd to make targeted arrests, while blue shirts made repeated baton charges to clear occupiers, reporters, and spectators from the intersections. When I attempted to photograph and film the particularly brutal arrest of a friend, I received a fist to the face and a push to the pavement from one of the commanding officers.

At one point, I even saw the officers turn on their own, detaining a retired Philadelphia police captain, Ray Lewis, still sporting his navy-blue uniform. Before being led away in handcuffs, Captain Lewis told the cameras, “All the cops are just workers for the 1 Percent, and they don’t even realize they’re being exploited. As soon as I’m let out of jail, I’ll be right back here and they’ll have to arrest me again.” Whenever a blockade was broken up, as it inevitably was, the remaining occupiers would regroup and put out a call for reinforcements. All the while, breathless updates circulated to supporters and spectators via SMS, social media, and the live feed from OccupyWallSt.org:

8:39 a.m.: all entrances to Wall Street occupied.

8:55 a.m.: sitters at Nassau dragged away, Beaver requesting help, police using batons.

9:09 a.m.: traders blocked from entering stock exchange.

10:10 a.m.: protesters and police at stand-off at multiple intersections; people’s mic breaks out across locations to share heart-breaking, inspirational stories of the 99 percent.

Wild rumors made their way through urban space and cyberspace. For a time, many were convinced that Wall Street had, in fact, been shut down, and that the opening bell had been stopped. But by 10:00 a.m., the party was over, the Exchange was open, and financial firms were back in business.17

Wall Street, for its part, was finally fighting back. Bankers and traders reacted with audible and visible frustration to the occupiers in their midst. One man in a gray suit held a hastily scrawled sign that read, “Occupy A Desk!” Furious chants of “Get a job!” could be heard emanating from one- and two-person counterprotests.

One occupier would confront a financial executive, who had been participating in the counterprotests, with the following words: “Ten percent of Americans are looking for work, most Americans are struggling, and you stand smugly in your suit and say to “get a job.” You’re insulting just about everyone in your country.”

As the day wore on, the center of gravity shifted from the Financial District to other parts of the city. Occupiers and sympathizers held subway speakouts, as planned, at nine stations in five boroughs, from the South Bronx to the Staten Island Ferry, and from 125th Street in Harlem to Jamaica Center in Queens. They then boarded the subways en masse, mic-checking stories of unlivable wages and unpayable debts, home foreclosures and school closures. The political ferment reached as far as Kingsborough Community College, on the southernmost tip of Brooklyn, where I and other speakers introduced OWS to a crowd of over 500 CUNY students, many of them first-generation Americans.

When I made it back to Manhattan, I found Union Square teeming with upwards of 5,000 students from area high schools, colleges, and universities. Many had walked out of their classes earlier that day, in a student strike called by the All-City Student Assembly in solidarity with Occupy. Filling the north end of the square, the students rallied in the rain, mic-checking, chanting, singing, and sharing stories of their struggles with rising tuition and student debt.

“Coming from the projects, CUNY was my only opportunity,” said a young Latina woman, a student from Hunter College. “I’m scared to death that the children of New York City will not have theirs. CUNY used to be free. And it should be again!”

A young black woman named Dasha, a fellow student worker from New York University, mic-checked her own story with her daughter in her arms: “As a graduate student, I now work full-time while caring for my two-year old. . . . I stand here today to speak out as one of the 99 Percent, to declare my humanity, to use my voice to claim this university, to claim these streets, to claim this city—as ours.”

As the student rally drew to a close, its ranks swelled with thousands who had marched uptown from Zuccotti Park. Together, we filed out of Union Square and spilled into the streets in a sea of black-and-white placards: “Out of the Squares and Into the Schools!” they read. “People Power! Not Ivory Tower.” CUNY students marched in a bloc, armed with “book shields” in symbolic defense of public education, with titles like Zinn’s People’s History of the United States and Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. NYU students carried an oversized banner reading, “CUT THE BULL,” beside the severed head of a bull-shaped “Neoliberal Piñata.” Moments later, a rowdy contingent from the New School streamed into the student center, outmaneuvering police and private security, and dropping banners from the first-floor windows declaring it, “OCCUPIED.”

What followed was a miles-long march to Foley Square, which was ultimately corralled on the sidewalks by battalions of police moving on foot, on motorcycle, on horseback, and in helicopters. When we finally reached Foley, we were greeted with an impressive show of force. An estimated 33,000 supporters had poured out of the subways and into the square, many in answer to urgent calls to action from Occupy’s union allies: “We urge every 1199SEIU member, our co-workers, family members, friends and neighbors to join us,” read one such call. “This is our fight, too.”

Here were those workers in their thousands, behind their trademark purple banners, alongside kindred contingents from eight other powerhouse unions: among them, the Communication Workers of America in their “sea of red”; the United Auto Workers with their blue-and-white picket signs; the National Nurses United with their red-and-white “Tax Wall Street” placards; and the city’s United Federation of Teachers, with one of the most memorable of the day’s signs borne by one of their number: “PLEASE DON’T ARREST ME. I’M TEACHING THE FIRST AMENDMENT.”18

Yet amid the outpouring of rank-and-file support for the occupiers, the leadership of the unions seemed to struggle, for the first time that fall, to rein in their troops and to retain control of the rally’s message. Prior to November 17, occupiers and labor leaders had agreed to distribute five soapboxes about the square, at which participants could share their stories by way of the People’s Mic. Instead, they found a single stage erected in the middle of the square, with a set list of speakers.

“It was supposed to be a very decentralized rally,” organizer Doug Singsen would later inform me. “But we got there, and D.C. 37 had set up a stage with giant speakers. . . . That march had a very un-OWS feel to it . . . . They controlled the crowd very tightly.” Likewise, the act of civil disobedience on the bridge had a highly choreographed character, with labor leaders and elected officials coordinating closely with the police before politely stepping into the roadway. For many occupiers, this scene could not have contrasted more starkly with that seen at the battle of the Brooklyn Bridge on October 1 or the taking of Times Square on October 15.

Still, as the marchers streamed out of Foley Square, squeezed between police barricades, and made our way onto the walkway of the Brooklyn Bridge, in a procession that stretched over a mile long, many expressed a sense that their actions had left an indelible mark on American society, shining an incandescent light on the inequities and injustices of our time.

As we looked out over Lower Manhattan, we saw the Verizon Building lit up with words of hope and possibility, projected, in the style of a “bat signal,” from a nearby public housing project (see Figure 0.2):

“MIC CHECK! / LOOK AROUND / YOU ARE A PART / OF A GLOBAL UPRISING/ WE ARE A CRY / FROM THE HEART / OF THE WORLD / WE ARE UNSTOPPABLE / ANOTHER WORLD IS POSSIBLE / HAPPY BIRTHDAY / #OCCUPY MOVEMENT. . . . WE ARE WINNING. . . . DO NOT BE AFRAID.”

While neither Wall Street nor the Brooklyn Bridge was physically shut down that day, the day of action would send an unequivocal signal that the Occupy phenomenon could and would outlive the occupations themselves, at least for a time. It also helped to inaugurate a winter of discontent, in which “community members, community groups and labor [would be] taking their fight for jobs and economic justice out of the park, and into the streets,” and “show[ing] how far the 99 percent have spread beyond Liberty Park.”19

“Even after the eviction, it was a huge mass mobilization,” says Mary Clinton, of the Labor Outreach Committee. “And I think that showed that, even without the encampment, we’re still here, we’re still fighting back, we’re still gonna shut you down. . . . And maybe in some ways, being in the streets, occupying schools, occupying homes, or organizing and fighting back at work . . . is just as threatening, if not more threatening, to the system as the encampment itself. I think November 17 was a reflection of that.”

The upsurge in the streets coincided with what may well have been the largest and most significant wave of unrest on U.S. college campuses since the 1970s. For years, the promise of higher education had grown farther and farther out of reach for Americans of my generation. Facing rapidly rising tuition rates and record student debt, compounded by low incomes and dismal job prospects upon graduation, students and their supporters were now answering the call to “occupy everywhere.” By November 17, over 120 universities, public and private, had seen some iteration of occupation, with student strikes, building takeovers, tent cities, and public teach-ins. In the weeks following the evictions of Occupy Oakland and OWS, however, the student movement was to be met on campus after campus with a concentrated crackdown.20

Leading the charge to “refund public education” were thousands of students across the University of California (UC) system, who, for the first time that year, were expected to contribute more to the cost of their education than the State of California. When students from Occupy Cal pitched seven tents in UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza on November 9, they were forcibly evicted by campus police and Alameda County Sheriff deputies, using thirty-six-inch batons as “battering rams” to break up the “human chain.” The crackdown sent thirty-nine occupiers to jail and two students to the hospital with broken ribs. YouTube footage of the assaults would electrify students on other campuses.

Occupy Cal, for its part, would call for a UC-wide student strike on November 15: “We will strike,” read their resolution, “in opposition to the cuts to public education, university privatization, and the indebting of our generation.”21 On the day of the strike, thousands of students once more massed on Sproul Plaza, birthplace of the Free Speech Movement, to hold a campus-wide General Assembly.

There, Berkeley student Honest Chung assailed the financialization of higher education: “These big banks are directly connected to our universities, through the Regents. . . . These are the people that run our university. . . . They want us to be in debt. We need to understand that when they raise our fees, they raise their own profit. When they increase our debt, they increase their own wealth. They would rather have us pay. . . rather than have their own corporations or interests taxed.”

At San Francisco State and at UC Davis, students struck in solidarity with Occupy Cal. Some occupied the lobbies of campus administration buildings. Elsewhere, citing a “real danger of significant violence,” the UC Regents canceled their scheduled meeting for the day.22

On November 17—long known to the Left as “International Students Day,” in commemoration of the 1939 student rising against the Nazis in Prague and the 1973 Polytechnic Uprising against the military junta in Greece—many more campuses joined in the strike wave, in solidarity with OWS, but also with the international student movement. As students struck and occupied in Spain, Italy, Germany, Greece, Chile, Nigeria, Indonesia, and elsewhere, thousands walked out of class and converged on campus quads at some ninety-three U.S. universities.

The strike stretched beyond the historical hotbeds of student radicalism, reaching community colleges and state universities deep in the American “heartland.” For instance, Occupy Texas State marched on the Capitol for a joint rally with public sector workers in Austin; Occupy Oklahoma State held an outdoor general assembly in Norman; and Occupy Oregon State staged a “funeral for the American dream” in Corvallis.23

Later that night, at UC Davis and at UC Los Angeles, students gathered in massive general assemblies, both of which voted to erect tent cities on campus. Both were raided the following day, yielding twenty-four arrests. Fifty Davis students responded to the arrests with a nonviolent sit-in along the walkways of the quad.

“Move or we’re going to shoot you,” they were reportedly informed by Lt. John Pike of the UC Davis Police Department. When the students refused to move, they were answered with an orange-colored cloud of military-grade pepper spray, fired at point-blank range from an MK-9 aerosol canister by Lt. Pike and the officers under his command. One anonymous student eyewitness would later recount her version of events:

A collective decision was made on the fly to just sit in a circle. We linked arms, legs crossed. We were just sitting there, nonviolent civil disobedience. But Pike . . . he lifts the can, spins it around in a circle to show it off to everybody. Then he sprays us three times. I crawled away and vomited on a tree. I was dry heaving, I couldn’t breathe. In between hacking coughs, I raised my fist in solidarity with the students peacefully chanting the officers off of the quad. Even in the face of brutality, we remained assertively passive.24

The viral footage of the brute force used against the Davis student body would elicit strong emotions, expressions of disgust and dismay, and calls for the resignations of both Lt. Pike and University Chancellor Linda Katehi, who had overseen the operation. Yet some students expressed concern that the spectators were missing the point: “We cannot let this occupation, or the public’s concern over the situation, be limited to the police brutality. Police brutality is just a symptom of systemic failure.”

On November 22, thousands reconvened for an Occupy Davis General Assembly, voting overwhelmingly in favor of a “general strike” on November 28. Their call to action was aimed, not at the UC Davis Police, but at what they saw as the nexus between police violence, the defunding of public education, and the defense of private interests with public funds: “The continued destruction of higher education . . . and the repressive forms of police violence that sustain it, cannot be viewed apart from larger economic and political systems that concentrate wealth and political power in the hands of the few.”25

At the same time, the crackdown was coming home for students across the continent. Against the backdrop of New York’s ongoing budget battles, the CUNY Board of Trustees was set to vote on a proposal to raise tuition by more than 30 percent over five years. On November 21, in the hopes of reversing the hikes, Students United for a Free CUNY and Occupy CUNY affiliates set their sights on a public hearing scheduled to be held at Baruch College. They were joined by students from NYU 4 OWS and the All-City Student Assembly, fresh from the success of the “N17” student strike and the kickoff of the Occupy Student Debt campaign earlier that day. As an alumnus of the City University system, I offered to play a support role as a photographer and videographer.26

As dusk fell over Manhattan’s Flatiron District, a youthful, multiracial, predominantly working-class crowd assembled in Madison Square Park, bearing banners emblazoned with the image of a fist clenching a pencil, and the words, “Education is a Human Right, Not a Privilege.” Participants used the People’s Mic to tell stories of the struggle to pay for college: “My name is Jennifer,” said a shy black woman with a camouflage backpack. “My brother’s in Afghanistan. He’s paying my tuition—and my sister’s. . . . They pay him $25,000 a year to be a specialist. He can’t afford these tuition hikes.” A Latino student from City College mic-checked these words of encouragement: “Every right that we have! Has been fought for! By students! And every time students! Have fought! We have won! We will fight! We will win! We will not be denied our rights!” Finally, the crowd set out in a raucous sidewalk procession down 23rd Street.

When we made it to Baruch College’s Vertical Campus, students held the doors open, and over 100 of us poured into the lobby. We were met with a “crowd control front line team,” armed with wooden batons and blocking our entrance or egress, as grim men in suits informed us that the hearing was now closed. Chants of “This is a school, not a jail!” could be heard echoing through the lobby, interspersed with mic checks like this one: “If this is an open forum, why cannot we get access? This is a denial of our rights. Our First Amendment rights, that people like myself, veterans of this country, fought for—fight for. I want my rights! This is bullshit!”

Once more, I would witness nonviolent direct action answered with violence, as the “front line team” charged, batons first, into the youthful crowd. As my footage would reveal, and as a CUNY-commissioned report would later confirm, “the protesters were not engaging in violent or threatening behavior” at the time of the baton charge. Some were sitting, others standing with peace signs raised high above their heads. Perplexingly, the officers gave repeated orders to “Move! Move!”—but the students plainly had nowhere to go, wedged as they were between the back wall and the advancing police line, as other officers blocked the exits. I saw multiple students fall to the ground, some of them screaming in pain. Others I saw being dragged by their limbs as they were placed under arrest. I was able to catch much of the onslaught on camera, before being driven out the door by a DPS officer wielding a wooden baton.27

With the winter fast approaching, the Occupy diaspora was increasingly defined by the struggle for survival: physical survival for some, political survival for others. Over the past two months, the occupiers had evolved their own routines of reproduction, from the meals served twice daily to the assemblies held nightly on the steps of Liberty Square. The People’s Kitchen, in its heyday, had served over 1,500 dinners a day to all comers. The Comfort and the Shipping, Inventory, and Storage working groups had supplied free shelter, clothing, and bedding. And for the past month, National Nurses United had provided free, high-quality health care to every occupier on demand. Beyond their most basic material needs, many of the occupiers had found in the space of the square the warmth of community, a source of camaraderie, and a sense of their own worth.

By the time of the raid, the “lower 99 Percent”—a popular euphemism for the homeless and the working poor—had come to count on these counter institutions as a safety net of last resort. A great number of them had long been living in exile—from their homes and hometowns, or from homeless shelters and hospital wards—long before the advent of Occupy. Many had been unemployed for months or years, while many more had had to take low-wage, part-time jobs that barely paid the bills or fed their families.

For those occupiers, the prospect of a free meal or free medical care had not only meant the difference between eating and not eating, or between getting care and getting sick. It had also meant the difference between participating and not participating in the movement. “People left everything they were doing,” observes Amin Husain, “because they had a place to stay and something to eat and were willing to put up a fight.”

When their needs were provided for, as they had been in the square, the occupiers had the time, the energy, and the motivation to join in actions, go to meetings, and volunteer for tasks. “For the first time,” says Malik Rhasaan of Occupy the Hood, “a lot of these guys felt like they had something. They had something tangible. They were working. They were out there giving out flyers. They were out there being heard for the first time. . . . [But] after they raided the park, they left a lot of these homeless guys out of the loop. [And] when the smoke cleared . . . they were still homeless.”

Uprooted from their communal home, their routines of reproduction suddenly and irrevocably disrupted, the occupiers sought refuge wherever they could find it. While the better privileged among them had their own assets (or their families’) to fall back on, and the better networked among them could count on the hospitality of friends, colleagues, and comrades, others found themselves without recourse to the resources, the care, or the community that they had come to depend on.

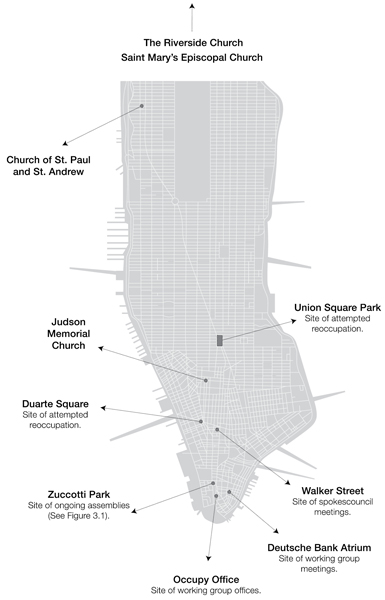

Amid the post-eviction exodus (see Figure 6.2), individuals and working groups sought to reconstitute the counterinstitutions of the camp in exile. The People’s Kitchen, decimated though it was, continued to feed the hungry masses at Zuccotti when police permitted it, and at satellite sites when they did not. One week after the eviction, the kitchen was back in action, serving up to 2,500 meals a day. The Housing Working Group found shelter for over 300 among the pews of Occupy-allied churches uptown. Local residents opened up their apartments for people to “rest, tend their wounds, take a shower, have a meal, etc.” And the Safer Spaces group worked to secure a “community agreement”—a basic code of behavior that could be expected from the occupiers in exile, including principles of respect and practices of consent.

Figure 6.2 Map of the post-eviction exodus, November 15–December 6, 2011. Credit: Aaron Carretti.

Other Occupy institutions, however, would prove unable to recover from the trauma of the post-eviction moment. Internal divisions, kept in check for a time by the common project of an occupation, now erupted into the open, threatening to tear the movement apart from within. In New York City, nowhere were these divisions more in evidence than in the general assembly and the newfound spokescouncil.

The GA was more inaccessible than ever to the “lower 99 Percent,” who faced expensive commutes from their new homes in exile, and bag checks and security screenings on arrival at Zuccotti. More than a few would inform me they were either too broke, too cold, too sick, or too harassed to keep going to GAs on a regular basis.

Those who made it into the park, for their part, found an inhospitable milieu, with participants talking over each other, discussants talking past each other, and group process breaking down on a nightly basis. The assemblies were increasingly dominated by one topic, and one topic alone: money. OWS, after all, still claimed a surplus of $577,000 at the time of the raid, and the GA remained the only decision-making body with the authority to allocate resources. With so many working groups, and so many individuals in need, competition over this considerable sum intensified.28

“Resources as a whole became a major divide,” recalls Lisa Fithian, whom we met in Chapter 4. “Occupy got a lot of money and it got a lot of things. I think Occupy did a fairly good job at distributing things. On the money, you had a small group of people who managed [it], but they never achieved a participatory budgeting process.”

Increasingly, the Finance Committee and its money managers came to be perceived as a sort of “1 Percent” within the 99 Percent, accused of subjugating the needs of the many to the interests of the few. In the words of Tariq, of the POC Working Group “Someone controlled the money. And you know who controls the money controls the show.”

Meanwhile, the spokescouncil, far from solving Occupy’s coordination problem, had devolved into a site of constant conflict and dysfunction. While the facilitators blamed the breakdown on a handful of disrupters (and moved to have them banned), the disruptiveness reflected deeper class divisions that were now making themselves painfully felt.

On one side were the more affluent activists who still had the means to “stay on process,” and expected the same of others. On the other side were the newly homeless and increasingly desperate, who had nothing left to lose but their voices. The outcome was a crisis of legitimacy for the coordinators, especially those who had left the park long ago and made their home at satellite sites such as the “Occupy Office.” Many of the displaced citizens of the square came to contest their informal leadership, publicly calling their authority into question and using the spokescouncil as a platform for criticism.29

The first spokescouncil I attended, just days after the eviction, presented a dramatic case in point. Invited to sit in as an observer, I found my way to the Walker Street space, a private venue reeking of body odor and crackling with tension. Some “spokes” sat in clusters, working group by working group, as they were supposed to, but most congregated in cliques, huddling with their closest friends and allies. Three facilitators did their best to guide the meeting from an elevated perch above the crowd.

The first challenge came when a kitchen worker proposed a discussion of what she called “the breakdowns in decision making [and] how we ended up without a park.” After a brief shouting match, the facilitator quieted the crowd, only to be interrupted by an outspoken homeless man, arguing that she had no right to “jump stack,” and insisting that we revise the agenda: “Every conversation we have should be, what are my needs? What are your needs? How can we fulfill those needs?”

The facilitators responded by urging us all to “keep it positive, keep it smooth,” and then reiterating a list of “group commandments” introduced at the last spokescouncil: “No cross talk. Respect the process. Only spokes speaking. . . . Step up, step back. Breathe. Honor each other’s voices. Use ‘I’ statements. W.A.I.T. (Why am I talking?).”

Yet whenever a facilitator sought to reassert control of the crowd, I heard an undercurrent of discontent well up around me. Now and then, someone would interject with an “emergency announcement”—“We got raided again! They took the library! They took the food!”—and walkouts and disturbances would ensue. Toward the end of the night, one ragged-looking white man stood up and said, with audible exasperation: “We didn’t know this was going on. We don’t have time to come to these meetings. . . . We’re starting to feel like pawns when the kings are in here, not out there.”

Behind the scenes, a growing rift was also developing within OWS’s “coordinator class.” The leading affinity group—in the words of one participant, made up of “all the people who are making all the things happen”—had already fractured days before the raid. The catalyst was a contentious meeting with White House veteran Van Jones, who had sought the occupiers’ endorsement of President Obama’s Jobs Act.

Figure 6.3 Return to Zuccotti Park. November 17, 2011. Credit: Michael A. Gould-Wartofsky.

“Basically, a bunch of folks got really pissed off and broke off . . . to do [their] own thing,” says Max Berger, a young white organizer from western Massachusetts who had previously worked with MoveOn.org and Rebuild the Dream. “They were just like, ‘We’re out’. . . . I think that split is what killed Occupy.”

The split left two rival factions in its wake, known as the “Ninjas” and the “Recidivists.” The Ninjas were avowedly anarchist and anti-capitalist, opposed to the making of demands, and oriented toward the reoccupation of urban space. The Recidivists touted a more pragmatist, populist politics, centered on coalition-building and community organizing for political and economic reform. The factions would go on to form opposing poles within the 99 Percent movement, competing for organizational resources, ideological hegemony, and the loyalty of the people in the middle.

Displaced from the center of their communal life, the occupiers in exile would make of the movement a house divided.