5. Handling and Use of Objects on Loan

10. Sample Incoming Loan Agreement

1. To Whom Will Loans Be Made?

6. Duration, Cancellation, and Return

7. Sample Outgoing Loan Agreement

1. Lending for Profit/Borrowing for Profit

3. Temporary Art and Site-Specific Installations

Loans, both incoming and outgoing, present distinct problems, and invariably these problems are best managed by preplanning. A museum’s collection management policy should establish rules and procedures that are designed to encourage thoughtful attention to all aspects of loan procedure, whether objects are being borrowed or loaned. Issues that may be addressed in the policy are listed in Chapter III, “Collection Management Policies,” Section B, “Guidelines for Preparing a Collection Management Policy.” In this chapter, some of these issues will be explored in more detail.1

In everyday legal parlance, a loan creates a bailment. The term “bailment” is derived from the French word “bailier” meaning “to deliver”: “[It imports] a delivery of personal property by one person to another in trust for a specific purpose, with a contract, expressed or implied, that the trust shall be faithfully executed and the property returned or duly accounted for when the specific purpose is accomplished or kept until bailor claims it.”2

When a loan is made to a museum, the lender is the bailor (the one giving), and the museum is the bailee (the one receiving). The law recognizes innumerable forms of bailments; some are classified for the benefit of the bailor, some for the benefit of the bailee, and others for mutual benefit. The classifications are relevant when determining the rights and liabilities of the parties. For example, if the bailment is viewed primarily as a benefit to the bailor, the standard of care imposed on the bailee is more relaxed. The bailee may be held liable only for gross negligence.3 If, on the other hand, the arrangement also is for the benefit of the bailee, the law requires the bailee to exercise at least due care in managing the entrusted property.

Although the law establishes general categories of bailments and sets forth duties imposed by each, these become of major importance only when there is no expressed contract governing the arrangements.4 If there is an expressed contract, its terms prevail.5 A museum is advised, therefore, never to accept a loan unless there is a written contract (that is, an incoming loan agreement) spelling out the rights and responsibilities of each party. Leaving the situation up to the common law could result in some unhappy surprises.

The museum’s incoming loan agreement (the bailment contract) should recite the standard of care that will be accorded the object while on loan.6 The most frequently used statement is that the museum will exercise the same care as it does in the safekeeping of its own objects of a similar type.7 Some loan forms speak of “ordinary care and supervision” or “reasonable care.”8 Other museums seem to impose a slightly higher standard on themselves when they promise to take “every possible care of the object.”

Invariably, the incoming loan form addresses the subject of insurance for the objects. The museum should insure borrowed objects. If an object is lost or damaged while on loan, the museum, as bailee, has the burden of proving that it was not negligent.9 In many instances, this is a difficult burden to sustain because the museum must come forward and prove due care. If there is uncertainty as to how an accident occurred, the party that must prove due care frequently suffers. Insurance offers a practical method for resolving lenders’ claims, and it protects the museum from possible catastrophic liability.

The incoming loan agreement usually offers the lender several options regarding insurance. The insurance can be carried by the borrowing museum, the lender can maintain its own insurance at the borrowing museum’s expense, or insurance can be waived. To enable the lender to make an informed decision, the loan agreement should briefly describe the insurance offered by the museum. Is it the “all risk” wall-to-wall policy subject to standard exclusions? (Be certain to list exclusions.) Also, the loan agreement form should have a provision stating that the amount payable by the insurance is the sole recovery available to the lender in case of loss or damage. And experience has shown that even this last simple statement merits further refinement in the loan agreement. In some situations, an insured object suffered damage while on loan, and the owner then claimed that because the object had appreciated in value while on loan, the partial loss now equaled the maximum value originally placed on the object. In other words, it has been argued that the loan agreement does not mandate that the stated insured value should always be considered the total loss value. To avoid confusion on this point, the museum should add to the loan form a sentence such as the following: “Any recovery for depreciation or loss of value shall be calculated on a percentage of the insured value specified by the lender in the agreement.”

If the lender elects to maintain insurance at the borrowing museum’s expense,10 several points should be spelled out in the loan agreement. The museum should require that it be listed as an additional insured on the policy or that rights of subrogation be waived. This is to prevent a possible later rude awakening for the museum in the event of a loss. Suppose the lender provides insurance for a valuable piece lent to the museum. Through negligence on the part of a museum employee, the object is damaged, and restoration costs are high. The lender’s insurance company reimburses the lender for these expenses, and in so doing, the lender’s rights arising out of the accident are subrogated (passed on) to the insurance company. The insurance company turns around and sues the museum for the restoration expenses caused by the museum’s negligence. Certainly, the museum has not been protected by the lender’s insurance. This can be avoided with some certainty by having the museum listed as an additional insured on the policy (the insurance company cannot seek reimbursement from the insured) or by having the lender waive the subrogation of rights against the museum.11

Additional issues should be clarified in the loan agreement when the lender insures. Some museums prefer to have in hand, before an object is shipped, a certificate of insurance verifying that the required insurance has been procured by the lender. Other museums look on this requirement to monitor a commitment made by the lender as placing an undue burden on the receiving museums. They prefer to rely on a statement saying that failure of the lender to provide the agreed-upon insurance constitutes a complete release of the receiving museum from any liability for damage to or loss of the property placed on loan. Even if a museum elects to request certificates of insurance, it may want to include the added precaution that failure of a lender to secure insurance constitutes a complete release of the borrower from any liability. The loan agreement should also provide that the museum will not be responsible for any error or deficiency in information provided by the lender to the insurer or for any lapse by the lender in coverage.

Situations may possibly arise in which, for practical reasons, a lender may want to waive insurance coverage. Unless it is clear in the loan agreement that this waiver constitutes a release of the museum from any liability arising out of the loan, the museum can still be sued by the lender, exposing it to legal fees and possible damages. A release of liability, therefore, should go hand in glove with a waiver of insurance. Even a release of liability might not protect a museum if loss is caused by the museum’s gross negligence.12 One additional caution is that if a lender elects to waive insurance coverage and signs a release because the lender is relying on protection from a blanket insurance policy, the lender should inform its insurer in advance. Execution of the release by the lender without concurrence by the insurer could inhibit the lender’s ability to pursue a later claim under the policy. (In other words, the insurer might claim that the lender signed away the insurer’s right of subrogation without the insurer’s permission.)

The valuation of the lender’s objects for insurance purposes can be troublesome. As a rule, the valuation should reflect fair market value, and this caution can be printed on the loan form.13 Some lenders still, innocently or through design, grossly overvalue their objects. This issue is important whether the museum is insuring or whether it is paying the premiums for the lender’s own insurance. In either event, there are obvious financial considerations and sometimes also ethical considerations, which are subtle and more difficult to deal with. If a claim is filed on an article that has been grossly overvalued, the insurer is bound to have questions. Did the museum, by accepting the valuation, tacitly endorse it? Can the museum honestly say, “It is not my problem,” and yet retain the goodwill of the insurer and/or the lender? Even if no claim is ever presented on the overvalued object, did the museum nevertheless assist in “hyping” the object? The owner can always demonstrate that the object was valued at that figure when loaned to the museum. The museum bears some responsibility for monitoring gross overvaluation, as well as gross undervaluation. Frequently, this can be one of the more difficult tasks for museum staff, but it should not be skirted or left for someone to resolve frantically at the last minute. Curators or even the insurer may be able to suggest where valuations of comparable objects can be checked by the lender. If all else fails, the museum should reconsider, at a very high level, whether the loan should be pursued.

Sometimes lenders fail to give valuations. They do not want to be bothered, or they do not know where to begin. To cover these situations, the loan agreement can provide that if a valuation is not given, the lender agrees to accept an insurance value set by the museum and that this value is not to be considered an appraisal. Museums are placed in an awkward position when they have the burden of setting an insurance figure on property owned by others, and it should be understood that under the circumstances, all the museum will provide is a figure within reasonable limits.

In the case of long-term loans,14 the loan form should clearly state who has the responsibility for updating insurance valuations. Most loan forms have a statement notifying the lender that it is the lender’s responsibility to notify the museum if it wants adjustments on insurance values.

Some museums that borrow fabricated works of art have limited insurance recovery in their loan agreements in certain instances. A well-known museum administrator gives two favorite examples that illustrate the problem. One concerns the sculptor who worked in fabricated steel; he lent his work, with an insurance value of $25,000, to a museum. The work was damaged while on loan, and the museum quickly reported the accident to the sculptor and assured him that it would pay the $4,000 necessary to have the damaged portion replaced by the steel fabricator. (The plans were still with the fabricator.) The sculptor demanded $25,000. After much wrangling, there was a substantial settlement.

The other example concerns a temporary exhibition of light works designed for a museum by an artist using neon tubes. After the artist prepared the specifications, the museum bought the parts and provided the labor to assemble the display. The total cost was $800. On the loan form, the exhibition was valued at $25,000 for insurance purposes. If some neon tubes are broken during the course of the loan, what is the recovery? This type of situation has prompted the inclusion in some loan agreements of a provision stating that in the case of works that have been industrially fabricated and that can be replaced, the museum’s liability, regardless of insurance valuation, is limited to the cost of such replacement.

Since the acceptance of loans brings with it a considerable liability exposure for the museum, it is only prudent to establish clearly who in the museum has the authority to approve an incoming loan.15 In a large, complex museum with considerable loan activity, approval authority may have to be delegated and redelegated depending, for example, on the value and kind of objects involved. Such delegations are frequently accompanied with a caveat that unusual situations should be reserved for at least the director’s attention. A clarification of approval authority and appropriate lines of delegation can be accomplished quite neatly by means of the collection management policy. Once adopted by a museum’s governing board, a collection management policy that spells out incoming loan procedures and approval authorities should constitute a valid delegation of power. This is just one more example of how important a good collection management policy is. It automatically puts the museum in compliance with professional guidelines on the subject of exhibitions, guidelines mentioned in the introduction to this chapter.

Setting out in writing the purposes for which loans can be accepted is a useful exercise and can prevent embarrassment. Some people look on museums as convenient warehouses, and with no clear policy direction, it can be difficult for the individual staff member tactfully to refuse friends of the museum who want to store family treasures. For example, if a museum has an established policy that, unless written permission is obtained from the director (or board of trustees), loans will be accepted only for special exhibits or for approved research, a ready answer is available.

An exception procedure to the general rule is a sensible precaution. Delicate situations can arise in which potential donors are looking for receptive homes for their collections. Museums have been known to offer free storage and other considerations.16 In New York, the attorney general publicly questioned the legality of one museum’s decision to offer long-term housing to a prospective donor’s collection. At issue was whether funds dedicated to a public purpose were being ill used in this instance. No legal action was taken, perhaps because these situations are rarely all black or all white. Much can be said on both sides, and invariably some very hard decisions have to be made by the museum.

There are additional matters that are worth considering when setting incoming loan policy. The fact that an object has been exhibited in a museum invariably enhances its monetary worth. Lenders have been known to whisk their objects from the exhibit floor to the auction block, touting recent exposure at a museum. Or the local museum of design might borrow for exhibit exemplary samples of contemporary crafts only to have the museum director later open the newspaper and read advertisements describing the crafts as “museum quality” or “selected by” the museum. Such potential problems should be brought to the attention of the staff. The first example is more difficult to control. The best protection is a perceptive staff that recognizes the pitfalls and selects lenders carefully. A simple precaution can control instances like the second example. If there is a possibility that the lender may use the loan for commercial advantage, he or she can be asked to sign a statement (or such a statement may be incorporated into the loan agreement) promising that no commercial exploitation will be made of the fact that the object was exhibited by the museum. If the lender objects to this provision, the museum may want to look for another lender. A museum that gives even the appearance that favoritism or commercialism rather than scholarship dictates loan selections is courting trouble.17

Closely allied is the subject of borrowing objects from board members or employees. Such loans are particularly vulnerable to accusations of self-dealing. A museum should have very stringent rules about this practice.18

Provenance issues should be considered regarding incoming loans. If, for example, an article is stolen property, was imported illegally, or was taken in violation of certain endangered species laws, the party that has custody of the article may be embroiled in legal proceedings. A certain amount of caution is necessary. If staff members are well instructed regarding the provenance criteria applicable to museum acquisitions, these same criteria can serve as guides in reviewing proposed incoming loans. Also, if a museum has publicly committed itself to an acquisition policy consonant with the goals of the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property,19 the display of borrowed material acquired by its owners in contravention of those goals can be an embarrassment.

A prudent provision in any incoming loan form is an affirmation by the signer of the form that he or she either is the owner of the object or is a duly authorized agent of the owner with full authority to enter into the loan agreement. This affirmation is not a cure-all, but it does demonstrate, if this point later becomes important, that the museum asked for and received assurance of authority to lend. Also, the very presence of the statement on the form might cause the uncertain lender to pause and to resolve in advance any problems in this area.20

It should not be assumed that lenders are familiar with what a museum may consider the routine use of borrowed objects. To avoid misunderstanding, the museum should spell out these uses in the loan agreement. If the lender objects to specific provisions, these can be discussed before entering into a loan contract.

If a museum does not restrict the use of cameras by the general public in exhibition areas, this may be worth noting on the loan agreement. If the museum expects to be able to photograph or otherwise reproduce borrowed objects for catalog, educational, or publicity purposes, this should be stated in the loan agreement. Such a statement can resolve copyright issues that could arise later on. Frequently, the subject of exhibit labels is important to the lender. The museum may want to clarify its policy in this regard and reach written agreement on the wording or placement of any credit line. If the museum reserves the right to fumigate objects and/or to examine them by photographic techniques, the loan form should so indicate. Most museums will not repair, restore, or in any way alter an object without the lender’s written permission. This is a sensible rule and one worth noting on the loan agreement. Even though a museum may reserve the right to cancel a loan at will, it might want to state on the loan form that an object may be withdrawn from display at any time.21 Occasionally lenders have considered it a breach of contract for a museum not to display continuously objects on loan.

Lenders should receive notice of the museum’s expectations concerning the condition and handling of borrowed objects. The average insurance policy covers a borrowed object “wall to wall” (from the time the object leaves the owner’s wall, or custody, until it is returned). The borrowing museum, therefore, has a definite interest in protecting its liability from the very inception of object movement. Where appropriate, several contract requirements can be imposed that lessen liability exposure. Some museums insert in their loan form a statement that the lender certifies that objects lent can withstand ordinary strains of packing, transportation, and handling. Museums may also request that the lender send a written condition report prior to shipment of objects. These two devices are designed to focus the lender’s attention on its role in risk management. If for some reason the objects in question should not travel or should travel only with special handling, the owner has the opportunity to give notice. The borrowing museum may also want to reserve some control over packing and transportation methods. It may reserve the right to prescribe such methods or to approve the owner’s methods. Much depends on the nature of the objects and the expertise of the lender.

A museum should have definite in-house procedures for monitoring the condition of loans. Immediately on receipt, borrowed material should be inspected and photographed, if appropriate, and written notations should be made of findings. Damage or suspected damage should be investigated immediately and appropriate action taken to notify the owner and the insurer. As a rule, none of this will happen unless there is clear definition of responsibility. Who is responsible for receiving and opening packages? Who must inspect? Who within the museum must be notified if there is damage, and who is responsible, for example, for compiling a record of findings and notifying the owner and the insurer? Who handles any claim negotiations? So often a museum’s claim payments increase in direct proportion to its degree of disorganization.

Similar instruction should be in force regarding the responsibility for monitoring loans and for promptly returning borrowed objects. The same attention should be given to inspection, packing, and transportation when returning objects as is given on receipt. This is the museum’s last opportunity to verify in writing, and/or through photographs, the exact objects being returned and their condition.

The following example illustrates the value of extra care. Museum X had on loan an exhibition of artwork done on transparent acrylic material. On the owner’s instructions, Museum X was to pack the exhibition and forward it to Museum Z for a subsequent showing. Museum X carefully packed the artwork in specially constructed cartons and listed, photographed, and described each piece inserted. Three cartons were forwarded to Museum Z, and under separate cover, duplicate lists of the shipped material were mailed to Museum Z. Several months later, a very agitated owner called Museum X. He had just visited the opening of his show in Museum Z, and two of his works were missing. Museum Z claimed it had never seen them. The owner valued the works at $10,000. On investigation, Museum X was able to produce descriptions and photographs of the objects it claimed it had forwarded. It could also produce duplicates of the lists sent to Museum Z. Museum Z, in turn, could not explain why it had not noted the discrepancy between the shipping list and what it claimed it had received. In addition, Museum Z had to admit to destroying all the specially constructed transportation crates and the packing materials. With the suggestion that the two pieces of lost art had probably gone out with Museum Z’s trash, Museum Z’s insurer quietly paid the owner’s claim.

Lawyers who have museums as regular clients eventually meet their nemesis in the form of either the indefinite or the permanent loan. Loans that are not monitored only invite trouble. Lenders move away or die, records become obsolete or disappear, and before long the museum finds itself saddled with objects over which it has little effective control. Can such objects be disposed of? If they need conservation or repair, does the museum have the authority to initiate such work? Is it obliged to do so? Can heirs of lenders claim these objects generations later? As a rule, the law offers no quick solutions for the museum that is trying to clean house or assert title over objects left in its care for generations.22 The only advice a lawyer may want to give with confidence is how to avoid these situations in the future.

Regarding prevention, a museum should adopt a general policy that all incoming loans must be for a set period that cannot exceed a certain length of time. For example, a museum’s rule might be that all loans must be for a definite term but that no term can exceed five years. This restraint forces regular evaluation of each loan situation.23 If mutually desired, the loan can be renewed and insurance valuations updated. If the material is ready for return, the likelihood is good that the lender is available or easily traced. If the museum would welcome the material as part of its own collections, this is a convenient opportunity to discuss the possibility with the lender. On the whole, this procedure is simply good management for the modern museum.

Regarding the duration of incoming loans, a museum may want to reserve to itself the ability to terminate a loan at any time before its expiration with reasonable notice to the owner. Consider this instance. A museum is planning a major special exhibition that will consist mainly of objects borrowed from private individuals, and loan agreements are executed. Shortly before the exhibition date, the museum loses most of the funding for the show, and the exhibit is canceled or drastically curtailed. Some of the lenders are enraged. They have touted the fact that these objects will be on exhibit, and they demand full execution of the loan agreement. Another unpleasant situation can arise when a museum has entered into a loan agreement only to find that the object it intends to borrow has serious provenance or ownership problems. If the museum goes through with the loan, it will be enmeshed in legal wrangling or professional criticism. Both situations can easily be solved if the loan agreement expressly warns that the museum may terminate the loan at will.

By definition, loans are temporary arrangements, but regardless of what Webster’s says, many museums are the possessors of permanent loans. And what is a permanent loan? The definitions are as varied as a roomful of museum professionals: “the opposite of a short-term loan”; “longer than an indefinite loan”; “a loan that ultimately will be given to the museum.”24 A lawyer turning to case law does not get much help, unless it is useful to know that in 1924 an English court stated, “I do not think ‘permanent’ [loan] means everlasting or perpetual and they are right in treating the word ‘permanent’ in the sense that it is contra-distinguished from something that is temporary.”25 Corpus Juris Secundum is closer to the mark. It notes that “[t]he significance of the term [“permanent”] depends on the subject matter in connection with which it is employed, and its meaning is to be construed according to its nature and in its relation to the subject matter of the instrument in which it is used.”26

In reality, therefore, the term “permanent loan” in itself tells little, and unless the parties spell out in detail precisely what is meant, uncertainty reigns. At best, some permanent loans are in written agreement form describing rights and obligations of the recipient museum. Most are bereft of such instructions, and questions constantly arise. Must the object be insured even if the museum does not insure its own collections? If the object is damaged, is the museum liable to the owner, and if so, how are damages measured? Can the object be lent to other museums? What if the museum can no longer justify the expense of retaining the object? If the owner is available, answers can be sought, but the museum may find that it has limited bargaining power.

Many permanent loan situations probably came about because the lender wanted to defer a hard decision and because the recipient museum, eager for the object, thought mainly in terms of present needs. Situations of this kind rarely improve with age, since there is even less incentive for the lender to make that “hard decision” after the museum has committed itself to caring for the object. As time goes on, the attractiveness of the loan to the museum may begin to dull because the upkeep has become expensive or because similar objects have since been acquired for the museum’s collections. If the lender is not readily accessible,27 much time and money can be spent trying to locate heirs or successors in interest to request renegotiation or termination. Even if the lender is known, the museum can only hope that it is sympathetic to changing the arrangements so that confrontation in court is unnecessary.

Consider this rather typical example. Organization X has acquired as a gift an extensive collection of books on the history of textiles. Under the terms of the gift, the organization can never dispose of the collection and must always keep it together in one room labeled as the collection of Donor Z. Before long, Organization X realizes that it has made a mistake; it has no urgent need for the collection and cannot justify the expense of upkeep. It turns to the local museum and offers to place the material on “permanent loan.”28 The museum quickly accepts. As years go by, the museum takes a closer look at its coup. Many of the books need expensive conservation work. The collection is of uneven quality, and if it was owned outright by the museum, it could be greatly improved by pruning and judicious exchange. In addition, the requirement that the collection be kept together in one room prevents its full utilization. The museum approaches Organization X, which is very reluctant to discuss the matter. Any relief will require that Organization X initiate a cy pres or similar petition in court, and the organization has no incentive to incur this expense.29 In hindsight, the museum realizes that it should have taken a firmer stand when the loan was initially offered. The museum could have agreed to support the organization’s petition for court relief if the petition requested permission to make an unrestricted gift of the collection to the museum. Or the museum could have accepted a loan of the collection for a limited period of time. At the termination date of the loan, the museum would have possessed an unquestioned right to return the collection if a more suitable arrangement could not be negotiated. Faced with the imminent return of the collection, Organization X might have had more incentive to resolve the matter.

It is difficult to imagine a situation where an indefinite loan is a more suitable arrangement than a series of term loans. In this day and age, entering into an indefinite loan situation usually marks a museum as sorely lacking in professionalism. However, a permanent loan between organizations or institutions might be justified in rare circumstances. For instance, one organization may have a very strong moral and/or cultural claim to material but may not be able to support with certainty a legal claim. The possessor organization might conclude, with good reason, that the public will generally benefit if the material is in the custody of the claiming organization, but it may be reluctant to pass title because of the possibility that someday the material could be transferred to a third party. A permanent loan, with the rights of each party carefully spelled out in an agreement, might be a legitimate solution.30

The incoming loan form should require the lender or the lender’s representative to give prompt notice to the museum if there is a change in ownership of the material on loan. Loan agreements impose obligations requiring that a museum periodically consult with the owner, and of course the museum should be able to reach the owner at the termination of the loan or sooner if an early termination is sought. If the present owner cannot be ascertained conveniently and with certainty, the museum is at a grave disadvantage. Therefore, the museum should clearly indicate that as part of the loan agreement, the owner or the owner’s representative has a responsibility to keep in touch with the museum. This provision is especially helpful if the owner dies during the loan period. Notice to the museum by the estate at the owner’s death permits consultation regarding oversight of the loan during probate proceedings and verification of who will succeed to the owner’s rights. If mutually agreeable, a new loan agreement can be entered into with the party succeeding in interest, or the museum, with the assurance that it is dealing with the right party, can return the material. The notice provision also may help in those cases in which the museum is unable to locate an owner and, years later, heirs appear to claim the property. If in fact no notice was given to the museum of the change in ownership, the failure to abide by the terms of the loan agreement would work to the heirs’ detriment.

Through experience, most museums have learned that not all owners can be relied on to retrieve their property. Too often, museums have found themselves holding, indefinitely, property of owners who cannot be located, and the law affords them no clear guidance on how to resolve these matters.31 Museums are now trying to prevent such situations by spelling out in their incoming loan agreements exactly what will happen if property is not claimed in a reasonable time. If a museum has not yet considered adding such language to its incoming loan form, it should give immediate attention to this matter.

According to such a clause, if material cannot be returned at the termination of a loan, it will be maintained at the owner’s expense and risk for a set number of years.32 At the expiration of this final period, if the material is still unclaimed, the owner, in consideration of the museum’s care, is deemed to have made an unconditional gift of the property to the museum. In drafting and implementing such a provision, a museum should observe several cautions. First, the loan agreement should be clear as to the date the loan terminates. This sets the precise time when the owner should come forward. If this element is missing, the museum will have difficulty establishing when the holding period began. Without a certain time, the owner or the owner’s heirs can always argue that the loan was meant to last until they saw fit to demand the return of the property. Second, the museum should clarify which party has to initiate the return. Some loan forms provide alternative arrangements from which to select. The owner can request the museum to mail the object to a specified address, or the owner can elect to retrieve the object. If options are offered, the museum should be sure that a selection has been made. Finally, the museum should provide some form of written notice to the owner when the loan terminates, stating that the material is being mailed or that it is time to retrieve the object. If cautions such as these are observed and the museum maintains meticulous records documenting its efforts to return the property, the “gift provision” should withstand challenge.

However, this caution is in order. More and more states are passing statutes that set forth policy for museums within the state regarding the handling of “old loans.” Chapter VII, “Unclaimed Loans,” goes into considerable detail on this subject. These statutes vary, and it is important for a museum to check to see if its state has such legislation and, if it does, whether the museum’s loan form (on the issue of unclaimed loans) needs adjustment in light of the legislation.

When borrowed objects are returned, the museum should have some form of a written receipt as part of its loan record. In the case of objects retrieved in person by the owner or agent, proper identification should be requested and the receipt immediately signed. Objects returned by mail should include a return receipt, or preferably, the receipt can be sent separately by certified mail. Experience has demonstrated that the lender should be required to return the receipt within a certain time period or else forfeit any claim for damage or loss. The purpose of the requirement is to encourage claim resolution while evidence is fresh, a fair procedure for all concerned.

Chapter VII, “Unclaimed Loans,” explains in some detail what museums frequently refer to as “the old loan problem”—the fact that most museums over time find that some lenders disappear and cannot be easily located so that objects can be returned. To help relieve this situation, museums, on a state-by-state basis, have been seeking special legislation that clarifies how such situations can be resolved. Statutes of this nature differ from state to state, and as of 2011 not all states have seen fit to pass such legislation. It is important for a museum to know if its state has such legislation in place and, if it does, whether the museum’s existing loan forms and procedures need to be adjusted in any way in light of such legislation.

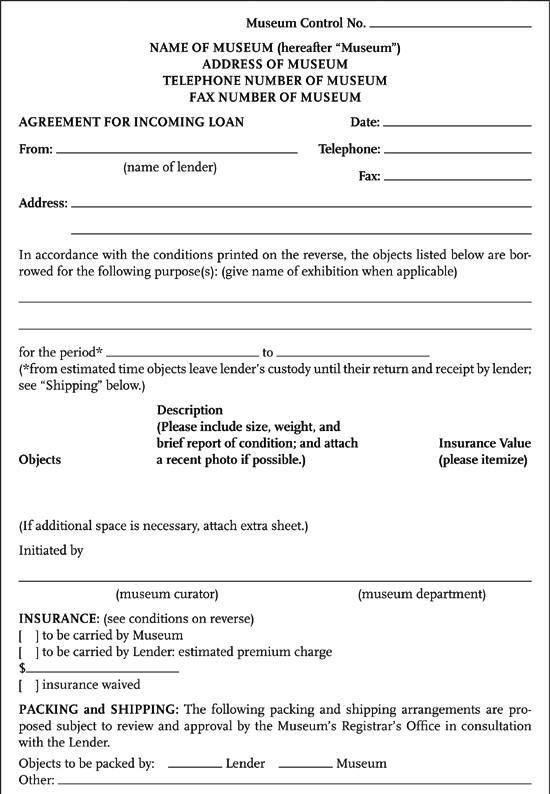

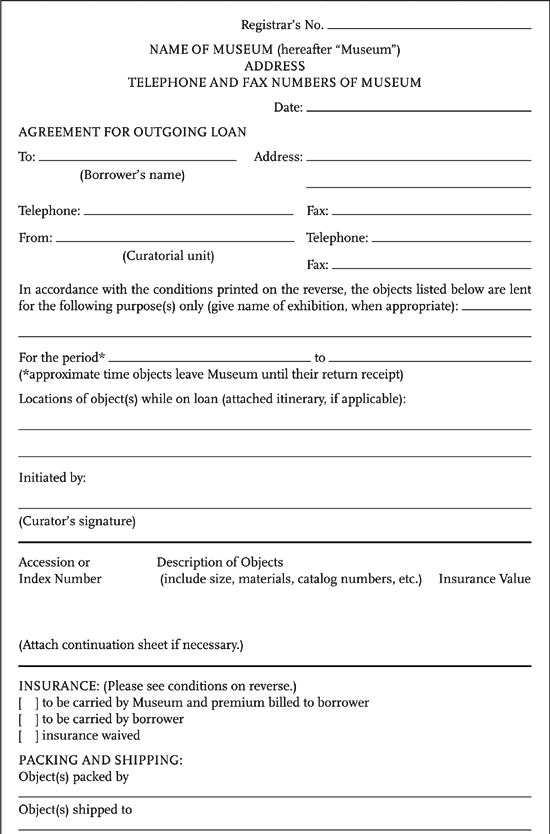

Like all other sample forms, the model incoming loan agreements that follow should not be adopted by a museum without independent review by competent professionals. If the lender is another museum, quite possibly the lender may insist on using its outgoing loan form. This is understandable because its objects are at issue. In such cases, each party should carefully review the other’s form, and differences should be resolved in advance. It is not unusual (assuming no major differences are apparent) for both forms to be signed with the expressed understanding that the terms of one (usually the lending museum’s form) will prevail in case a conflict develops.

The first model form is patterned on one used by a large history museum and is suitable for a range of loan purposes (see Figure VI.1). The second model is based on one that a large art museum uses specifically to borrow artwork for a discrete exhibition (see Figure VI.2).

When a museum assumes the role of lender, several new considerations arise that have legal implications. A very basic decision that should be made early is the museum’s general policy regarding eligibility to borrow collection objects.

Most museums do not lend to individuals. There are sound reasons for this rule. Of paramount importance is the fact that museum collections are maintained for the benefit of the public; rarely can a museum justify their exclusive use by any individual. And there are additional reasons:

• Adjustments made in the tax laws many years ago require donors to relinquish control over property donated to a museum if full charitable-contribution tax deductions are to be taken. If museum policy permits donated property to be returned temporarily to the donor under a loan agreement, the validity of the donor’s tax deduction could be called into question. (But see the fine points of this as discussed in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section F.4, “Special Tax Considerations.”)

Figure VI.1

Agreement for Incoming Loan (History Museum)

• Museum trustees and officers have a duty not to self-deal when managing museum assets, and their acceptance of loans of collection objects for personal benefit could amount to a violation of this responsibility.33 A museum policy that generally forbids loans to individuals serves as a useful reminder of this particular standard of conduct.

• When museum objects are on loan, they should be afforded the care and protection normally expected in a museum environment. As a rule, such requirements can be met more readily by institutional borrowers.34

Frequently, museums limit borrower eligibility even further by lending only to educational and/or nonprofit organizations. The purposes of this limitation are to focus loan activity on educational and research projects and to avoid entanglement in commercial ventures.35 The latter purpose warrants special attention by government-run or government-associated museums.36 Such museums could find their loan policies challenged on constitutional grounds if loan policies are drawn without reference to equal-protection guarantees. Consider the following example.

Figure VI.2

Agreement for Incoming Loan (Art Museum)

The X Historical Society, run under the auspices of the county government, is asked to mount a small exhibit in the lobby of the local bank. The exhibition will be part of the bank’s fiftieth birthday celebration and will depict life in the county fifty years ago. The historical society eagerly agrees to the loan because the exhibit will have prominent exposure and the bank promises to meet all temperature, humidity, and security requirements. The exhibit is a popular success. Some months later, the historical society is approached by the local department store, which asks if it can borrow material for an exhibit on the local textile industry. The material will be used in an “educational” window display. Once again the society agrees. When the local liquor store comes forward with a similar request, it is rejected because “the loan wouldn’t be suitable.” The owner of the liquor store protests and threatens legal action.

There is a good possibility that the liquor store will get its exhibit. Both federal and state constitutional safeguards generally guarantee equal access to government-offered benefits, and exceptions are narrowly construed. Once the X Historical Society, a part of the local government, extended a benefit to the bank and the department store, both commercial entities, it established a practice, one that the law may well require it to administer even-handedly to all commercial entities in the area. The lesson, therefore, is simple, especially for government-run or government-associated museums: Have a thoughtfully prepared loan-eligibility policy, and understand all its implications. Once certain actions have been taken, selection criteria may be severely limited.

If proper handling is to be afforded all objects in a museum’s care, some distinctions must invariably be made regarding what can be placed on loan. A primary consideration is whether the museum has the authority to loan a particular object. If the object is on loan to the museum and is not part of its own collections, no outgoing loan should be considered without evidence of written approval from the owner.37 A normal use of an incoming loan does not include a reloaning of the object. If such is contemplated, the permission of the owner should be expressly sought, usually in the loan agreement. Another consideration relating to authority to loan is whether the object is encumbered by restrictions that inhibit a loan. Accession records should be reviewed carefully to see if any such restrictions exist. When there is doubt regarding the existence or interpretation of restrictive language, professional advice should be sought.38

The value, rarity, and/or condition of an object may dictate loan restrictions. No object should be exposed to loan conditions that may seriously threaten its safety, and the museum is obligated to use due care in this regard.39 What constitutes due care depends on the facts of each situation. Possibly, some objects should never be placed on loan because of fragility.40 If there is a serious question concerning the ability of an object to travel, the museum should seek the opinion of a conservator.

To ensure that sufficient regard is given to the question of what should be loaned, a museum is advised to have written guidelines on hand for staff instruction. The guidelines also should be clear on the issue of who has the authority to approve loans. Here, again, if the museum has a well-drafted and board-approved collection management policy, such guidelines are already in place.41

As a rule, the basic authority to make loans resides in a museum’s board of trustees.42 The board may retain the exercise of this authority or, barring specific legal restrictions to the contrary, may delegate and redelegate its exercise. Complete delegation, however, without guidance and oversight, is not in accord with normally accepted trust responsibility,43 and a museum’s board will want to assure itself that policies and review procedures clarify who has the authority to make certain loans and what records must be maintained. If delegations are clear and adequate records are kept, effective oversight is possible.

When and how much loan-approval authority should be delegated are largely matters of common sense. In a large, complex museum, many routine outgoing loans can be left to the discretion of designated members of the professional staff. As a rule, such delegations are limited to loans not exceeding certain values or certain amounts or are limited to objects in certain classes. The rule of thumb for the museum’s board is whether the delegation is a reasonable one in light of the museum’s overall size and activities.

The lending museum has an obligation to take reasonable precautions to ensure that museum objects placed on loan receive proper care. If the borrowing institution is not known to the museum, a facilities report may be in order or even an inspection visit by museum staff so that such matters as physical conditions and security standards can be judged. Also, the museum’s loan agreement should specify the care that should be afforded the borrowed objects so that there are no misunderstandings. If a museum has a history of poor experience with a borrower, prudence would dictate a stringent review before any new loans are negotiated.

A loan agreement usually contains a standard clause requiring the borrower to give prompt, written notice to the museum of any damage or loss to loaned objects. Also included is a general caution that objects cannot be altered, cleaned, or repaired without the written permission of the lending museum. If, in addition, a condition report is required of the borrower on receipt of a loan, not only is delivery confirmed, but any problems associated with transportation can also be handled in a timely manner. Requiring a similar condition report before objects are packed and shipped for return helps to pinpoint responsibility if the objects are received back in damaged condition.

Packing and transportation methods should not be left to chance.44 The borrowing institution should be on notice that certain requirements must be met when the objects are in transit. If special cases have been prepared for sending the material, the borrower is usually instructed to retain the cases for use in return shipment. In any event, the lending museum should clearly communicate to the borrower any special care needed in unpacking the loan item or in returning it. The loan agreement should also specify who is responsible for the packing and transportation costs.

The cautions against indefinite and permanent loans mentioned in this chapter’s Section A, “Incoming Loans,” apply also to the museum as a lender. There are few situations in which it would be prudent for a lending museum to lend objects on an indefinite basis. Museums are obligated to use due care in overseeing collection assets, and if objects are loaned, the museum’s responsibilities do not disappear. “Due care” can be interpreted to mean that loan situations should be checked periodically to see that objects are safe, that they are being used for the agreed-upon purpose, and that insurance valuations are current. A practice of lending only for a stated term, subject to renewal, encourages adherence to the due care standard.45

Invariably, the lending museum insists on insurance coverage for all objects sent out on loan. Insurance offers the added measure of security that claims will be processed objectively and that resources will be available for payment of damages or replacement of the loaned object. As a rule, the borrower absorbs insurance costs by either providing insurance satisfactory to the lender or by reimbursing the lending museum for providing its own insurance.

If the borrower is to provide insurance, the lending museum will want evidence that adequate coverage has been obtained before objects are released. As a rule, a certificate of insurance or a copy of the policy is requested before shipment. The borrower should also be warned that any cancellation or meaningful change in insurance coverage must be immediately communicated to the lender. A wise precaution is to add to the loan agreement a statement that failure of the borrower to have in effect the agreed-upon insurance will in no way release the borrower from liability for loss or damage. The purpose of such a statement is to rebut any inference that the lending museum may have waived its rights by any inaction on its part in monitoring the borrower’s insurance. Even if there is no insurance coverage, the lending museum still wants to preserve all legal rights it may have arising out of loss of or damage to its property.

Occasionally, a borrower is not able to provide standard insurance coverage. It may, for example, be a governmental entity that self-insures.46 In such instances, the lending museum will want to assure itself that the borrower will respond to any loss or damage claim. If the borrower has an established method for processing claims and can demonstrate a history of fair and timely attention to such matters, the lending museum may well decide that there is no undue risk in negotiating a loan. However, a clear statement in the loan agreement to the effect that the borrower agrees to indemnify the museum for any loss or damage occurring during the course of the loan is an added protection. Such a statement establishes that the borrower was fully aware of potential liability when it undertook the loan.

Setting a value on objects for insurance can raise problems for the lending museum. For example, some natural history specimens may have no readily ascertainable market value, but their loss to the collections would be significant. Some objects may be irreplaceable, and some, if damaged, may need restoration work that could be more costly than their market value. The insurance value of an object does not always equal fair market value, and in those cases where insurance estimates significantly exceed the traditional fair market value test, the lending museum should be prepared to defend its position. If the borrower does not question the valuation before entering into the loan, the insurer may well do so when a claim arises. During negotiations for a loan, if there are serious differences of opinion between lender and borrower over insurance valuations, the advisability of going forward with the loan should be weighed. The costs of pursuing any claim that might arise and the potential for aggravating already strained relations may far exceed the perceived benefits from the loan.

As explained earlier, in this chapter’s Section A.7, “ ‘Permanent’ Loans,” indefinite loans are avoided today by the prudent museum, and a permanent loan should never be considered unless there are extraordinary circumstances and a carefully crafted agreement describing in detail the rights and obligations of both parties. When the museum is the lender (i.e., the situation is an outgoing loan), the reasoning behind this rule becomes even more evident. A museum that sends its objects off for indefinite or very long periods with no mechanism in place for regular monitoring of their use and care hardly presents a picture of prudent stewardship. Today museums lend objects only for stated, relatively short periods of time, subject to possible loan renewal.

When an object is loaned for a definite term, there is a presumption that the borrower, as long as it does not breach the terms of the loan agreement, will have the right to use the object for the stated time. If the lending museum wants to have the flexibility of canceling the loan before the termination date or of recalling the object for a period of time, these conditions should be made an express part of the loan agreement. Without the benefit of such contract provisions, the lender who attempts to recall objects before the stated termination date may get a firm refusal or, accompanying the returned material, a bill for damages.

If objects have been loaned on an indefinite basis, the normal assumption is that either borrower or lender may request termination. However, the facts of each situation must be reviewed to see if there is evidence that both parties may have intended otherwise when the loan was negotiated. Any museum that finds itself with objects out on indefinite or poorly documented permanent loan should consider the advantages of seeking to renegotiate each such loan for a stated term. As noted previously, indefinite or permanent loan situations tend to produce problems that grow worse with time. A museum may find it prudent to take the initiative in clarifying such loans with the borrower before conflicts arise that make amicable resolution much more difficult.

Once a loan has ended, the lending museum should promptly retrieve its property. Unclaimed property is likely to become lost or mislaid. Also, the borrowing organization could take the position that it owes a lesser standard of care to property left beyond the term of the loan agreement47 or, if the property is unclaimed for a long period of time, that there is an inferred gift, as described in this chapter’s Section A.9, “Return Provisions,” Therefore, a museum is advised to have in place a system for monitoring loan terminations, giving clear guidance to staff regarding responsibility for seeing that loans are actually returned.

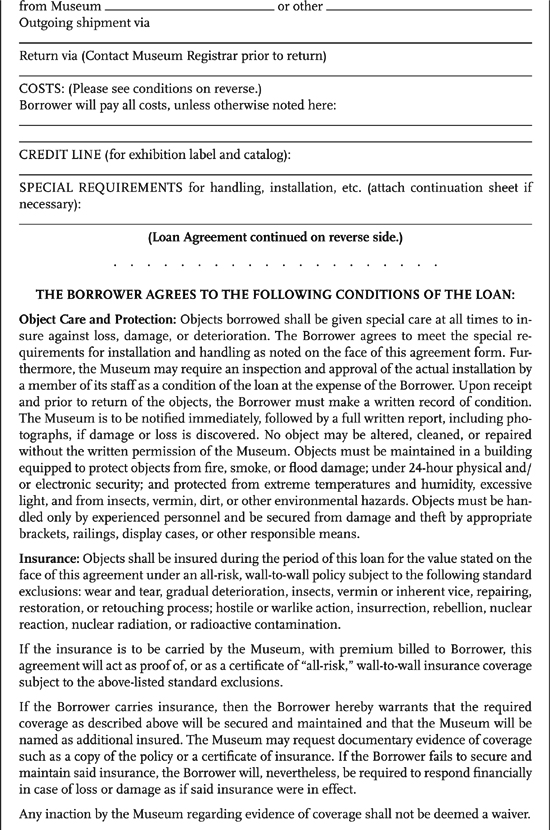

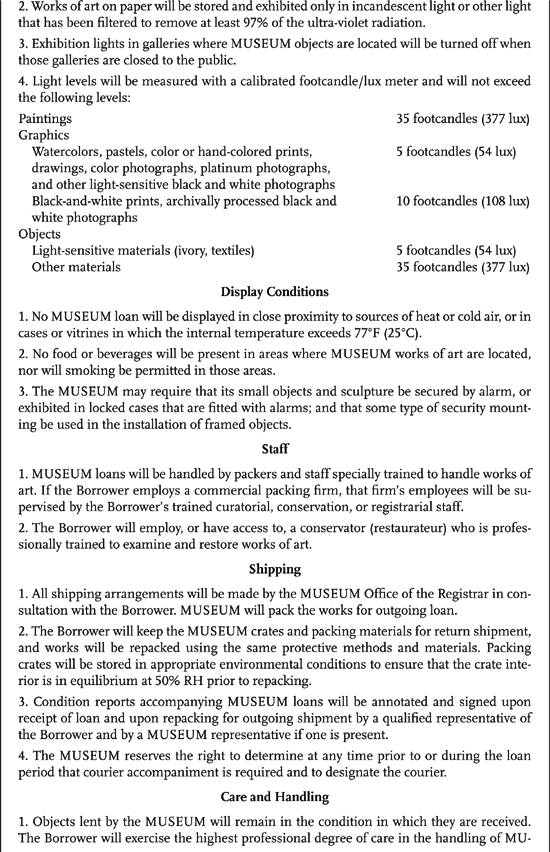

Like all other sample forms, the outgoing loan agreements that follow should not be adopted by a museum without independent review by competent professionals. If in a particular transaction the borrower wants to use its incoming loan form as a supplement to the lender’s outgoing form, both documents should be reviewed in advance for compatibility. Even where there appears to be no substantial conflict, the lender may still want to specify that its form will be the controlling one.

The first sample outgoing loan form is modeled on one used by a large history museum and is suitable for a range of loan activities (see Figure VI.3). The second sample outgoing loan form is one that several large art museums use specifically to lend artwork for exhibition (see Figure VI.4). For the sake of efficiency, the museums collaborated to produce a form that is acceptable to all of them.

Traditionally, museums in the United States have looked on the lending and the borrowing of objects as integral parts of a museum’s educational mission and have conducted these activities “at cost” in recognition of their importance. The “at cost” standard with regard to outgoing loans ensures that a request to borrow is judged on the merits of the proposed use, on how the loan may affect the lending organization’s ability to serve its own constituency, and on the ability of the objects in question to withstand the strains of travel. The “at cost” standard with regard to incoming loans ensures that museums focus on their own missions, that they emphasize scholarship, not entertainment, and that they avoid commercial ventures that could raise problems with the IRS. Another important consideration is that the “at cost” standard treats all museums equally regardless of their size or wealth and regardless of whether they are borrowing or lending. Although there were some deviations from the “at cost” standards with regard to outgoing loans during the 1980s, museums in this country did not openly discuss the issue of “lending for profit”—lending with the objective of making a profit—until the early 1990s.48

Figure VI.3

Agreement for Outgoing Loan (History Museum)

Figure VI.4

Agreement for Outgoing Loan (Art Museum)

What triggered more open discussion was a case involving not a museum but an educational organization known as the Barnes Foundation of Merion, Pennsylvania. The Barnes Foundation is a nonprofit organization created by a trust agreement of the late Dr. Albert C. Barnes. Under the terms of the trust agreement, the foundation oversees the Barnes Collection, some one thousand works of art collected by the donor. This collection must remain “on site” at the Merion location so that it can serve as the means for teaching art appreciation in a manner fostered by Dr. Barnes. In the early 1990s, the trustees of the Barnes Foundation needed funds to undertake major building renovations. They first decided to seek court permission to deaccession and sell some of the objects from the collection (court permission was necessary because the trust agreement forbade deaccessioning),49 but this idea was abandoned when the museum community voiced strong disapproval of selling collection objects in order to raise money for renovations.50 Then, with the active cooperation of some major U.S. museums, the Barnes trustees devised a plan whereby a group of pictures from the collection would be exhibited in Paris and Tokyo for loan fees amounting to some $7 million, with additional millions expected from auxiliary activities associated with the foreign tour. The plan was presented to the court for approval because, once again, the activity violated restrictions imposed by the donor. The court granted a one-time deviation to allow the tour and later granted permission to extend the tour to include additional stops, with loan fees in the millions, in the United States and Canada. In all, the tour was said to have grossed over $15 million.51 Clearly, this event, which could not have happened without the active participation of several large U.S. museums and which generated much media attention, placed the issue of lending for profit squarely before the museum profession.52 There were few strong criticisms voiced by the profession, and in fact, several other large museums were busily pursuing lending-for-profit projects of their own.

In 1992 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York entered into an eight-year arrangement with the San Jose Museum of Art in California to install in San Jose four sequential exhibits, each lasting eighteen months, drawn from the permanent collections of the Whitney. The San Jose Museum committed to pay the Whitney $1.4 million for its services, and the Redevelopment Agency of the City of San Jose added a $3 million bonus for the Whitney.53 The Whitney was reported as stating that it will dedicate its sizable income from the loans to caring for its collection and to strengthening its endowment fund. The city of San Jose sees the exhibit arrangement as an “economic catalyst” that will generate millions of dollars in local economic activity.54

At the same time that the Whitney Museum was negotiating its lending-for-profit arrangement, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) was entering into an agreement with the city of Nagoya, Japan, whereby the MFA would provide Nagoya, over a twenty-year period, with exhibits drawn from the breadth of the museum’s collections. When queried, the museum merely affirmed that it would be “compensated” for its services.55 In other words, for a fee, the MFA was pledging to place portions of its collections on loan to Nagoya for varying periods of time over the next twenty years.

Japan has been a popular destination for a number of “loans for profit” from the United States. In Japan, department stores and other commercial venues commonly house cultural exhibitions, and Japanese entrepreneurs have had considerable success in convincing a number of American museums that this is the thing to do. Before long, some American museums were lending collection objects for substantial fees to commercial outfits that mounted exhibitions that were clearly tourist attractions. This arrangement not only proved to be very profitable for the museums, but it also encouraged them to experiment with more “crowd-pleasing” shows in their own exhibit halls.56 It may be difficult to top this last idea about “lending for profit.” It is Brandeis University’s 2010 proposal about how it hopes to improve the very fragile financial position of the university. The plan is to close the university’s Rose Art Museum and then rent out to exhibiting organizations, for a fee, works from the Rose collections. Proceeds would go to the university’s endowment fund. As of early 2011, it is uncertain as to how this plan will develop. In any event, it sets a worrisome step toward pushing museum functions further into the commercial sector.

Another step in commercializing the exhibition process appears to be a willingness on the part of some museums to take part in exhibitions organized by outsiders for commercial purposes. In these cases the curator is being replaced by a sports promoter or someone with a similar background. All the museum has to provide is the venue. Of course, one sure result for those attending such exhibitions is a hefty ticket price, because the promoter is in it for profit and the “venue museum” wants its cut. One other factor is that exhibitions of this type are usually competing against sports events or pop concerts for their audience and, thus, tend to be promoted as mainly entertainment. One might say that a museum offering the venue for such an exhibition is just “borrowing for profit.”57

This last exhibition arrangement is worth mentioning with the hope that it is quickly recognized as a foolish venture for any museum. It is an earlier described financial problem that arose for the Brooklyn Museum as part of its negotiations for its Sensation exhibition, a matter discussed in some detail in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section E.5.c, “Content-Related Rights: Privacy, Publicity, First Amendment.” This was a case where the Brooklyn Museum sponsored an art exhibition that contained one object that was seen by many in the area as an insult to their religious beliefs. There was strong public protest. In the course of New York City’s inquiry to the museum about the nature of the Sensation exhibition, it was discovered that the Brooklyn Museum had solicited thousands of dollars to help finance the exhibition from persons with a commercial interest in the event. One such person was Mr. Saatchi, an art dealer who not only owned the art in the show but also helped fund the exhibition itself. In return for this help, Mr. Saatchi gained some artistic control over the exhibition plus the possibility of earning a “refund” if the show was successful. Such an arrangement is a clear violation of the ethical codes promulgated by the professional museum organizations in this country, and it is difficult to believe that senior staff in a museum of any size could be unaware of this ethical standard.

It is important to note that when the financial arrangements for the Sensation exhibition were made public, the American Association of Museums felt compelled to publish a paper titled Guidelines on Exhibiting Borrowed Objects. Essentially the paper states that before considering exhibiting borrowed objects a museum should have in place a written, board-approved policy that sets forth internal rules that must be met before objects can be borrowed for an exhibition. Rules would cover such topics as relevance of the exhibition to the mission of the museum, existence of any possible conflicts of interest, inappropriate fee arrangements, inappropriate lender involvement, etc. In effect, the burden is put on the museum to state publicly its ethical standards for borrowing objects for exhibition before engaging in further loan activity. Actually, museums that have well-drafted collection management policies in place (see Chapter III, “Collection Management Policies”) already have this guidance in effect. The AAM paper was issued in July of 2000, and it was later joined by another related AAM publication titled Guidelines for Museums on Developing and Managing Individual Donor Support. Both of these publications are available on the AAM website.58

One hopes the AAM papers have attracted the attention of many in the profession, because the loan-related practices described above should surely worry them.59

These practices, if unchecked, could rob our museums of their effectiveness because they tend to do the following:

• Commercialize the use of collections and thus clearly contradict the museum community’s position that collections are not assets to be placed on a balance sheet60

• Shift the focus away from a museum’s own public (When there is money to be made by sending collections out on loan, there is pressure to devote more time and attention to this activity than to the core work of the museum.)

• Threaten privileges museums currently enjoy (If revenue is consistently drawn from loans made to locations away from a museum’s tax base, local authorities may have reason to examine more closely the property tax exemptions customarily provided to such museums.)

• Encourage wear and tear on objects (When loans are a source of substantial income, there is great pressure to keep objects moving as often as possible.)

• May cause problems when individuals are asked to lend objects to the museum for exhibition (These individuals, who normally lend gratis, may now expect to be paid a fee as well.)

• May end up actually costing a museum money rather than providing extra income (Practically every museum that lends also borrows. This means that the museum that charges lending fees may realize little because it, in turn, must pay fees when it borrows.)

• Widen the gulf between the more powerful museums and the more modest ones

• Discourage restraint in collecting because excess collections are seen as sources of revenue61

• Cause admission fees to escalate as exhibitions morph into entertainment

Museums concerned about the long-term consequences of their actions will want to give serious thought to all of these possible consequences. What is at issue is the undermining of the reasons why we support a nonprofit sector in this country. Go back and read Chapter I of this book and review the section that explains why our nonprofit sector has been granted certain privileges and consider how important these privileges are to our museums. What happens if our museums lose these privileges?62

When a museum commissions an artist to create a piece of temporary art for on-site exhibition, this involves elements of a loan in that the museum has the right to exhibit for a set period of time a work it does not own. But this situation also involves complex issues that do not arise in the traditional loan situation.

One such issue is balancing the artist’s freedom to conceive and produce the work and the museum’s legitimate interest in having some control over what it exhibits. When the project is still only an idea or a sketch and a contract has to be written before work begins, how should these possibly conflicting interests be framed? Other issues include the following:

• Deadlines. Museums have set schedules for opening and closing exhibits. When the readiness of an exhibit depends on the ability of an artist to start the creative process and complete it within a set time period, much can go wrong.

• Access. The project invariably requires that the artist have access to the museum, to support services, and perhaps to members of the museum staff. How is this covered in a contract when no one can predict the flow of the creative process?

• Rights. Is the installation to be photographed and, if so, by whom? Who controls the photographs, and who has rights to the photographs—photographs that will eventually be the only record of the work of art? Who controls diagrams and models produced in the creative process? Who owns the components of the work after its removal?

• Costs. How is the artist paid, and exactly what costs are covered by the payment? (In other words, what additional expenses should the museum anticipate during the course of the project?) Who repairs or adjusts the work during the exhibition period if this becomes necessary (and who decides this), and how are such costs handled?

• Removal. When the exhibition is over, who is responsible for removing the artwork, and what are the options if removal does not take place in a timely manner? Tied into many of these questions is the issue of the artist’s precise relationship with the museum during the process. Is he or she an independent contractor or an employee? How the process actually unfolds should support the desired relationship.

While it is important for a museum to have in place a carefully crafted contract with the artist before commissioning a piece of contemporary art for on-site exhibition, it borders on negligence for a museum to fail to have such a document in place before commissioning a site-specific installation. A relatively recent case underscores this point, and it is worth mentioning here. The case concerned some important issues arising under the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (VARA), and these issues are discussed in some detail in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section E.5.a, “Artists’ Rights: Droit Moral—The Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990.” Here, however, we want to look at how the museum involved in the case went astray.

The case, Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art Foundation, Inc. v. Büchel,63 involved an extended dispute between the museum and an artist, Christoph Büchel, who was commissioned by the museum to create on its grounds a football-field-size art installation titled Training Ground for Democracy. The museum entered the project with no written agreement and thus began a most unfortunate relationship marked by constant debates over design, costs, chains of command, time deadlines, etc. When work came to a stalemate, the museum went into court seeking a declaration that it was entitled to show the public the unfinished work. The artist, however, argued that such a use would violate the above-mentioned Visual Artists Rights Act. The court found for the museum, and the artist appealed. The appeal court ruled that the Visual Artists Rights Act does cover “unfinished art” and sent the case back to the lower court for further proceedings. The museum in the meanwhile was left with a major problem. It had a huge building on its grounds that contained “a wrecked police car, a carnival ride, rigged bomb casings, a dilapidated two-story house, a mobile home and a rusted oil tanker.”64 What could or should the museum do with all of this? Is this art or just “stuff,” and how is that decision made? What a hard way for a museum to learn the importance of having a carefully drafted agreement with the artist in place before any such endeavor is begun.

Contracts for site-specific installations should seek to address all reasonably foreseeable issues and, as an extra precaution, specify an agreed upon method for resolving issues where the parties are deadlocked. It is far easier to sort out rights and obligations in the calm before work begins. Museums that are part of government and, thus, are subject to state and/or federal constitutional protections regarding interference with free expression need special guidance in these areas. They should recognize also that since tax dollars are involved, they are more vulnerable to public opinion regarding the final product itself. The following sample agreement for a site-specific installation is used by a major nonprofit (not government-controlled) museum (see Figure VI.5). Like all other sample agreements, it should not be adopted in whole or in part by a museum without careful review and professional advice.65

Figure VI.5

Agreement for Site-Specific Installation

The evolution of corporate sponsorship of museum exhibitions may be viewed as a success story for all concerned or as an example of serious erosion of principle on the part of museums. There is room for differences of opinion on aspects of this evolution, but certain developments are a matter of record.

In the 1970s, museum exhibitions grew grander and more costly. Turning to the business community for financial support seemed like an excellent idea. Museums had a very visible “product” to present to these potential supporters, and what business would not be attracted by the public attention that would be focused on the product? During these early days of cultivating corporate support, the museum community engaged in considerable talk about the importance of protecting the independence of the scholarly endeavors of museums and of avoiding any real or perceived commercialization of exhibitions. In effect, corporate support at that time was viewed by museums as a form of corporate largess, generous gifts from corporate citizens for the purpose of funding educational projects for the benefit of the public. Museums dealt with corporate agents responsible for philanthropic outreach, and the legal aspects of negotiating such gifts were relatively simple. A corporation, like any other generous donor, could expect in return for its largess a sincere “thank you,” a discrete acknowledgment of the gift in the exhibition program, and an invitation to the opening of the exhibition. Not much paper was required to set forth the agreement.

But the 1970s also saw the rise of “image” advertising. Businesses were encouraged to advertise not their product but an image, because the image could be more seductive in attracting buyers. Focusing on image became very popular, and in due time members of the marketing departments of corporations pointed out to their colleagues that what might have been viewed as philanthropic outreach in the past was now just another facet of image making. A senior vice president of a major U.S. corporation, a corporation with a tradition of giving to the arts, noted, “In the 1990s, there is less paternal benevolence and more corporate giving focused on furthering broad company objectives.”66 She then explained the two “faces” to corporate giving: contributions and sponsorships. The first, contributions, are usually cash gifts and donations of products or services, and her company makes such contributions “[w]hen a worthwhile request in some way is relevant to our business agenda and has the potential of enhancing our corporate reputation.”67 She added the following:

A sponsorship is different. Sponsorships are much more focused on marketing and sales. When someone comes to us with a request to sponsor an event, we’re looking for heavy exposure of our logo. We want to build our brand. We want to enhance our market position. We are seeking to help build earnings. Often, we want to use sponsorships for customer entertainment, so the sponsorship has to be relevant and attractive to our customers.68

Corporate sponsorship today is not viewed by the company as philanthropy. Corporate sponsorship is not giving to benefit society but is contracting for marketing opportunities. The dangers for museums in this change of emphasis are substantial. There is the obvious problem of the tail wagging the dog—with sponsors determining what exhibitions are mounted. This is not to say that sponsors necessarily state what they want; more often the pressure comes from within the museum itself, where curators know that if their exhibitions hope to see the light of day, their ideas must appeal to sponsors and to the audiences that sponsors hope to reach. In effect, the choice of exhibitions is governed by the marketplace. But is not one of the reasons the United States fosters a nonprofit sector to protect certain activities from the pressures of the marketplace?69 Another equally worrisome problem is the overall effect of these arrangements on the spirit of philanthropy. Museums in this country depend heavily on donations of objects, money, and time from the general public. Why do museums afford corporate sponsors special treatment? Should individual donors or lenders also now expect some quid pro quo? Many museums either deny the real problems involved in corporate sponsorships or view such problems as circumstances they cannot control. With museums as a group unwilling to speak up, corporations each year ask for a bit more for their dollars.70

There is another problem that arises more frequently when corporations are sponsoring exhibitions. The corporation invariably wants its name displayed prominently in association with the exhibition, and this is seen by many as the museum’s endorsement of the company and what it does. How does the museum decide which sponsors are acceptable and which are not without offending some segment of the public? This is a “no win” situation.71

Today’s corporate sponsorship agreement can be a very detailed document, and it should be. A museum should settle as many things as possible during the negotiation period and commit them to writing. Also, a museum should not even attempt negotiations until it has acquainted itself with the realities of corporate sponsorship and has come to some internal agreement as to what it will accept and what it will not accept. If this preliminary soul-searching does not take place, the museum will be totally unprepared to hold its own during the deliberations. The following is a list of questions that frequently must be answered during contract negotiations.72

• Who are the real parties to the agreement?

—Does the museum see any problem with this type of sponsor underwriting the exhibition in question?73

—Is the exhibition sufficiently defined so that both parties know what to expect?

• What is the time frame?

• What support is the corporation giving?

—What is the payment schedule?

—How will payments be made?

• Will there be or can there be other sponsors?

—Who makes decisions regarding other sponsors?

—When must these decisions be made?

• How is the sponsor credited?

—If there are other sponsors, are there limitations concerning their credits?

• Is the museum required to contribute a certain level of funding?

• Under what terms can a party withdraw from its commitment?

• What happens if it becomes impossible or not practical to do the exhibition?

—Who makes this decision?

—How will finances be handled?

• Are there limitations on the museum’s ability to change the focus, scope, or size of the exhibition?

• What rights, if any, does the sponsor have to comment on the development of the exhibition?

• What does the sponsor expect in return for its contribution?

—Credit lines:

—Where?

—Size?

—Other publicity:

—Who controls?

—Who pays?

• Are there limitations on the right of the sponsor to use the name and/or logo of the museum?

—Exhibition catalog:

—Who produces?

—Who pays?

—What credit lines are to be used?

—Opening events:

—Who controls?

—Who pays?

—Other events or products that may affect the sponsor:

—How are these negotiated?

• Does the sponsor have the right to develop exhibition-related products on its own?

—If so, under what conditions?

• Will the museum and the sponsor agree to indemnify each other and hold each other harmless from claims arising from the actions of either under the contract?

• Can the agreement be assigned?

• Who are the contact people for each party with regard to contract issues?

—How is notice given?

—What law governs the contract?

—Who signs for each party?