C. Legislative Solution: State Unclaimed Loan Statutes

D. How to Avoid the Problem of Unclaimed Loans in the Future

E. Researching Unclaimed Loans

When museum professionals meet to discuss common problems, invariably someone asks what can be done about unclaimed loans, often called “old loans”1 because many of these objects have been held in a state of limbo for generations. The owners are unknown or cannot be located with relative ease, and because the museum lacks clear title, its options are limited. Although the museum may have physical possession, it has little control. The museum may not be able to lend the object to others, to reproduce the object (outside of fair use), to undertake conservation measures, or to dispose of it without the owner’s consent. All the while the museum bears the financial burdens, such as costs of storage, record maintenance, climate control, security, periodic inspection, inventory, insurance, and general overhead.2 Relying on the object’s continued presence in the museum can also prove to be troublesome. If the object is included in an exhibition, a lender or heir may come forward without prior notice and remove it. Or a museum without excess storage space may pass up an opportunity to acquire a similar object, trusting that the unclaimed loan will remain unclaimed. Despite the considerable drain on a museum’s resources, the alternatives are even less attractive. If the objects are disposed of, a museum may be vulnerable to future claims by individuals who later appear and assert ownership. If extensive searches are mounted to locate owners, a museum faces substantial expenses in terms of staff resources. The earnest museum administrator is often shocked to discover that the law and, frequently, even the public offer him little solace.

As explained in the preceding chapter, a loan produces a relationship known in the law as a bailment. The bailor, the owner, places property in the care of the bailee for a particular purpose. The bailee is responsible for holding the property for that purpose until the owner comes forward to claim it. What happens, however, when the owner fails to retrieve the property?

If the loan was scheduled to terminate at a certain time, the argument can be made that after the termination date the relationship of the parties is somewhat altered. While the loan agreement is in effect, the bailee is obliged to use and care for the property under the terms of the agreement, but after the expiration date, the “benefits” of the arrangement accrue only to the owner. This is because when the bailor fails to retrieve the property, the bailee is left with the responsibility of care but with no express rights to use the property. A new form of bailment then exists, one essentially for the benefit of the bailor, and the bailee usually is held to a lesser standard of care. Also, if the bailee can demonstrate that expenses were incurred in caring for the property beyond the stipulated loan period, these usually can be recovered from the owner. This “involuntary bailment” situation for expired loans is of little comfort to the bailee/museum, however, if the owner cannot be located or if, on notice, the bailor fails to retrieve the property. Often, though, the situation is even more troublesome for unclaimed loans with no stated termination dates. In the case of these “indefinite loans” (loans of undetermined duration), it would be hard, if not impossible, to establish that the loan term had ended and a new form of bailment had come into existence. So, with indefinite loans, the museum is left with providing a higher standard of care and little hope of ever recouping the costs of that care even if the lender were to reappear.3

Whether the origin of an unclaimed loan is an expired or an indefinite loan, museums are well advised to make it a priority to deal with the unclaimed loan problem, because the mere passage of time will not alter the legal bailment relationship. The obligation to care for the unclaimed object can go on indefinitely, and often the older a loan gets, the harder it may be to resolve. Consider that if the lender dies, his or her ownership interest in the object will pass to heirs. Often, determining the identity and location of heirs will be even more difficult and time consuming than locating a missing lender. To make things worse, returning the object to the wrong party may open the museum to liability for a claim brought by the rightful owner.

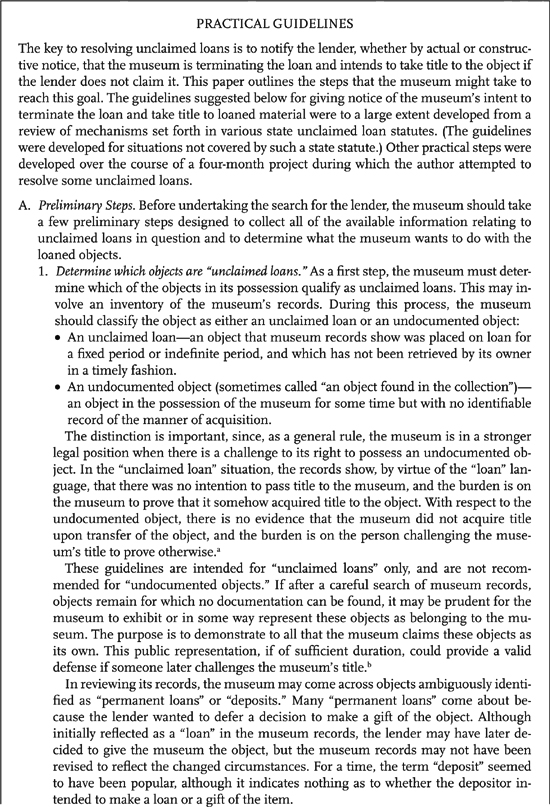

The key to resolving an unclaimed loan is for the museum to break the bailment relationship involved as soon as possible. Unfortunately, this is not easily done under general legal principles.4 In recognition of these difficulties, forty-two states, as of 2010, have passed unclaimed loan statues that specifically make this task easier for museums.5 These unclaimed loan laws, which vary somewhat from state to state, spell out the mechanisms by which the lender’s ownership of the object can be cut off, making it possible for the museum to take legal title to the object. With the title secure, the museum may then use or dispose of an object as it sees fit. More will be said about these state statutes, but first a discussion of “common law” principles (principles that govern in absence of a statute) is in order. These principles usually prevail in the states without specific unclaimed loans statutes, and knowledge of these principles will also assist in appreciating the terms of unclaimed loan statutes, because many were crafted to add clarity and a degree of certainty to common law approaches.

In states without unclaimed loan statutes, museums are left with general principles of common law to guide them. Common law refers to principles that do not rest for their authority on any express statute but on statements of principles found in court decisions. The application of these principles to unclaimed loans left in museums has not been fully tested in court. Nevertheless, under these principles, to break the bailment relationship, the museum must take actions inconsistent with the terms of the bailment. Simply put, the museum should notify the lender that the lender’s legal title to the object is being challenged by the museum and could be lost if the lender remains silent. For example, the museum should send a letter to the lender stating that the museum is terminating the loan and, unless the lender comes forward to claim the objects or make arrangements for their successful return by a certain date, that the museum will take title to the objects as of that date. If the lender is aware of the museum’s “conversion” (a legal term meaning unauthorized assumption of ownership of property belonging to another), the lender, under general principles of law, must come forward to protect his or her ownership interests. If the lender fails to claim the object or to bring a claim or suit to court within a specific time after the museum’s conversion of the object, the lender’s ownership rights may be lost because of the applicable “statutes of limitations.”6

As discussed earlier in Chapter V, “The Disposal of Objects: Deaccession,” Section C, “Request for the Return of Collection Objects,” the specific time periods to bring claims to court are provided in state laws, called statutes of limitations.7 Lawsuits are barred that are not brought within prescribed limitation periods. The purpose of statutes of limitations is to encourage claimants to take timely action before evidence fades and witnesses die. In Wood v. Carpenter,8 the Supreme Court of the United States gave the following description:

Statutes of limitations are vital to the welfare of society and are favored in the law. They are found and approved in all systems of enlightened jurisprudence. They promote repose by giving security and stability to human affairs. An important public policy lies at their foundation. They stimulate to activity and punish negligence. While time is constantly destroying the evidence of rights, they supply its place by a presumption which renders proof unnecessary. Mere delay, in extending to the limit prescribed, is itself a conclusive bar. The bane and antidote go together.9

Statutes of limitations vary in length from state to state and with the nature of the claim. For example, a claim for breach of contract will have a different limitation period from a claim based on negligence causing personal injury. Although it is relatively simple to determine the length of the limitation period in any state for a claim of “conversion,” the more difficult issue is to determine when the limitation period begins to run against an owner of an unclaimed loan to extinguish his claim. The general rule is that the owner of property “converted” by another must bring his or her claim to court within the limitation period that begins after his or her “cause of action” arises. A cause of action is a set of facts that give a person the right to file a suit in court.

Under the law of bailment, the cause of action usually arises when the lender demands return of the object and the borrower refuses. The lender’s cause of action may also arise when he or she is put on notice that the borrower is claiming title to the object, in effect, refusing to return the object. Thus, to utilize the statute of limitations to extinguish a lender’s right to an unclaimed object, the goal for the museum is to make sure the lender is put on notice that the museum intends to terminate the loan and to claim the loaned object as its own if the lender fails to come and get it or arrange for its return.

To ensure that the limitations period is triggered, the museum should notify the lender by certified mail, return receipt requested, to prove that the lender received actual notice of the museum’s actions. Upon receipt of the notice, the limitations period should begin to run, and after its expiration, the lender who has failed to take action should be barred from any further claim to the object.10 Title to the object will by default belong to the museum. At this time, the museum is free to do whatever it wishes with the object: to keep it, to lend it, or to dispose of it. Note that the museum may still be sued, but the lender’s claim would be dismissed as being time barred if the court finds that the museum’s procedures in providing notice to the lender were legally sufficient. Under the Constitution of the United States, owners of property must be given adequate notice and opportunity to protect their rights associated with that property.11

Anyone who has ever worked with old loans inevitably would ask the next question: What if the lender is unknown or the lender or heirs cannot be located? Are there any alternatives to actual notice? The District of Columbia Court of Appeals in In re Estate of Therese David McCagg, a case that involved an unclaimed loan to a museum, suggested that “[i]f reasonably diligent, bona fide efforts to locate Mrs. McCagg [the lender] or her successors failed, then constructive notice by publication might suffice.” In other words, the statute of limitations could be triggered by “constructive notice” at the time of the publication of the notice.12 The term “constructive notice” refers to notice to unknown or missing individuals by publication in a newspaper. If done properly, the law will presume that the notice reached the individual whether or not he or she actually saw the notice in the newspaper. Regarding establishing proper notice for judicial proceedings, the Supreme Court has said the following: “This Court has not hesitated to approve of resort to publication as a customary substitute in another class of cases where it is not reasonably possible or practicable to give more adequate warning. Thus, it has been recognized that in the case of persons missing or unknown employment of an indirect and even a probably futile means of notification is all that the situation permits and creates no constitutional bar to a final decree foreclosing their rights.”13

Many of the unclaimed loan statutes discussed below have implemented the constructive notice approach to notify missing lenders. The question remains whether constructive notice will be legally sufficient without an applicable state statute in place that provides how and when this may be done. Until this has been tested in court, museums in the handful of states without unclaimed loan laws must face an element of uncertainty in this area. This uncertainty should not prevent those museums from proceeding, because doing nothing cannot yield positive results.

However, the court in the McCagg case cautioned that constructive notice may be available only if actual notice is not possible. Thus, a museum must be in a position to show that the lender or heirs could not be located after reasonable efforts by the museum to do so. What might constitute a “reasonable and sufficient search” can vary on a case-by-case basis.14

The Supreme Court has noted that “due regard for the practicalities and peculiarities” of each case determine whether the constitutional due process requirements for adequate notice and opportunity to appear have been reasonably met.15 In addition to the museum’s own records, the following additional sources have been identified as useful for searching for missing lenders: probate records, telephone directories, real estate records, and vital (death) records. Depending on the circumstances, other avenues such as social registers or cemetery records may be consulted. In this age of the Internet, a number of these research sources are being posted online in retrievable databases. The utility of online sources to assist museum staff with such searches is improving yearly as more information becomes available online. See a discussion on researching unclaimed loans using the Internet in this chapter’s Section E, “Researching Unclaimed Loans.” It is essential that the museum clearly documents every effort made to locate lenders because the museum’s records of its attempts may become evidence in court should a lender or heir suddenly surface years later and demand return of the object. Typically, unclaimed loans in a museum collection are of little monetary value. The time, effort, and expense involved in carrying out a search should reasonably compare to the value of the object.16 If after reasonable efforts the whereabouts of the lender or heirs are still unknown, the museum may try “constructive notice” by publication in a newspaper.

The notice in the newspapers should include as much of the following information as possible:

• Date of the notice

• Name of the lender

• Description of the item loaned

• Date of the original loan

• Name and address of the museum staff to contact

• Statement that the museum is terminating the loan and will take title to the object if it is not claimed by a specified date

This notice should be published several times at repeated intervals (for example, once a week for three consecutive weeks) in a newspaper of general circulation in the county of the lender’s last known address and the county or municipality where the museum is located. The statute of limitations should begin to run after the date set in the notice as a deadline for contacting the museum—whether or not the lender or heirs have actually seen the published notice.

If the lender fails to come forward before the deadline given by actual or constructive notice, the museum should amend its records immediately to reflect its ownership of the object as of that date. In addition, the museum should note in the records the date of expiration of claims under that state’s statute of limitations. Although the museum asserts ownership from the date the object is accessioned or added to its nonaccessioned collections, the museum’s title to the object would be subject to challenge in a claim brought to court by the lender or heirs up to the time the applicable limitations period for filing suit had expired. Therefore, the file should note that prior to the expiration of the statute of limitations the object should not be disposed of by the museum. For example, in the museum’s published notice, the date in which title is claimed is June 1, 2010. Having failed to hear from the lender or heirs, on June 1, 2010, the museum accessions the object. Having been advised by counsel that the limitations period for a lawsuit alleging conversion is three years in the state where the museum is located, the museum will note in the records that the object should not be disposed of prior to June 2, 2013.

In planning a systematic approach to resolve old loans in states where no statute exists, museums are well advised to seek the advice of counsel in establishing procedures and forms for this purpose. See the discussion in this chapter’s Section E, “Researching Unclaimed Loans,” on further guidance on searching for lenders and Figure VII.3, “Practical Guidelines for Resolving Unclaimed Loans” by Agnes Tabah, which provides step-by-step instructions and sample forms.

However, because of a lack of clear precedents, even if all recommended steps are taken, there are no guarantees that claims will not be brought against the museum for conversion of the loaned object. In the worst case, a lender or heirs may surface years later and institute a lawsuit. At this point, if a court should determine that the steps taken by the museum to gain title were legally insufficient, the museum may need to return the object. If the object was disposed of in the interim, the museum may be ordered to compensate the lender for the value of the object, possibly as of the date the lender requested the return. Although the risk of a legal suit with the attendant adverse publicity should not be underestimated, this risk needs to be balanced against the substantial benefits gained by freeing the museum’s collections from unwanted objects that are costly to maintain and by having reliable, up-to-date records of objects in its collections. If the objects are of little value, it is unlikely that anyone is ever going to sue. If someone does threaten a lawsuit, the museum’s counsel may be able to negotiate a settlement without the need to resort to a formal legal proceeding. It is a relatively simple matter to offer to pay the lender an amount based on the value of the object in settlement of the claim minus the museum’s costs in storing and caring for the object pending the lender’s return.17 If the museum has disposed of the object after acquiring title, it should have an excellent record of the object’s value at the time of disposal.

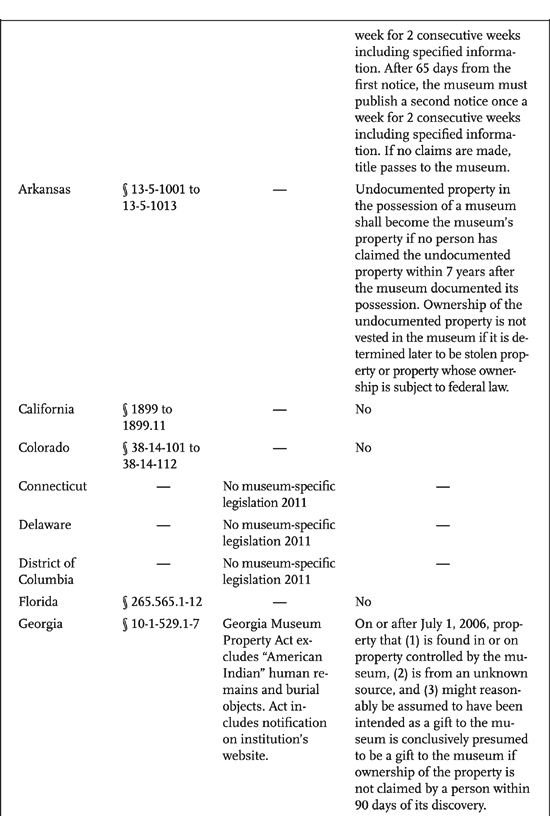

Because traditional legal doctrines were offering museums little certainty in solving their unclaimed loan problems, some museums decided to look to their state legislatures for the enactment of statutes that set forth procedures specifically designed to resolve these matters. Most of these statutes were passed in the last thirty years, and they range from a relatively simple Maine statute to a very detailed California statute.18 Some, by definition, cover only true unclaimed loans (situations in which there is evidence that the objects were placed as loans), whereas others, unfortunately, define the property covered as both unclaimed loans and undocumented property.19 For a museum located in a state that has passed an unclaimed loan statute, resolving the unclaimed loans will require following the dictates of the applicable statute. A chart describing state statutes that address unclaimed loans appears in Figure VII.1. Note that in a handful of states the law only applies to state museums. But even in that case following the procedures outlined for state museums may be instructive for other types of museums as well. While state unclaimed loan statutes vary in approach, they all establish specific mechanisms by which the museum may terminate the loan and take title to objects left unclaimed by lenders. In operation, the legislative solution mimics the common law approach but adds clarity and some degree of certainty of the adequacy of the procedures. In some cases, unclaimed loan statutes eliminate some cumbersome steps required under the common law approach. The usual scheme is for the law to prescribe a notice procedure by which lenders are notified by the museum that the loan is terminated. The notice procedures may apply to expired loans as well as to indefinite loans that have been at the museum for an extended period.

The notice may take two general forms. The first is by mail to the lender of record at his last known address, and the second is notice by publication in newspapers. Recently passed laws allow notice of loan termination to be sent to lenders electronically.20 Some statutes only require notice by mail to the name and address of the lender as it appears in the museum’s records of the loan, and others require a museum to look at all museum records generally kept in the usual course of business (for example, donor, fund-raising, or membership records as well). If that information is not accurate or if it is incomplete, no further search for the lender is required. Other statutes require a “reasonable search” for the lender, often not giving much guidance as to what the term means. If the lender cannot be reached by mail, the museum may proceed with notification by publication. Some laws require the notice to request anyone with knowledge of the lender or where the lender may be located to provide the information in writing to the museum. If, after notice, no one comes forward within the prescribed time period (ranging from thirty days to seven years), title to the object passes to the museum. Several states allow museums to take title to an object without giving notice if there was no contact between the museum and the lender for a long time. For example, California allows the museum to take title if there has been no contact with the lender for at least twenty-five years as evidenced in the museum’s records.21 As one commentator wrote, if the constitutionality of such unclaimed loan legislation provisions is questioned, “courts ultimately will consider the need for the particular provision, the importance of the rights affected, and whether the legislative solution is fair and reasonable in light of the circumstances and problems addressed.”22 Because of this potential problem, those initiating the California statute undertook extensive fact-finding regarding the unclaimed loan problem within the state, and on the basis of this information, the state legislature prefaced its legislation with a series of “findings” to support the procedures adopted.23

In addition, unclaimed loan statutes may impose obligations on lenders to notify museums of change of address and changes in ownership of the property. Some statutes address the issue of undertaking conservation work on unclaimed loans. Most recently the newly passed unclaimed loan law in New York addresses such issues as limiting the use of proceeds from deaccessioned objects whose title was acquired through the law and special rules regarding posting notice for unclaimed loans for objects with Nazi-era provenance.24

A question yet unanswered is whether these statutes will pass constitutional challenges by disgruntled lenders. The two issues usually mentioned are Fourteenth Amendment due process considerations (U.S. Constitution) and impairment of contractual obligations (U.S. Const., article I, section 10, clause 1). As of 2010, there have been no published court decisions testing the constitutionality of any state unclaimed loan statute, and so we have yet to see how a court may view these statutes with regard to due process issues. However, given that some of these laws have been in existence for over thirty years, the likelihood of constitutional challenge diminishes with time as more and more museums make use of these laws without attracting controversy.

An unpublished survey from the mid 1990s indicated that many museums at the time were not fully utilizing their unclaimed loan statutes.25 This conclusion was based on the sparse replies to a questionnaire on implementation of unclaimed loan legislation. The study posited the following reasons for this sluggishness. To use the statutes systematically, museums need to inventory their collections to determine which objects are in fact unclaimed loans. Inventories require time and effort and are too easily relegated to the “back burner.” Also, some museums may be reluctant to implement the statutes, fearing that important objects will be lost if lenders actually come forward and reclaim loaned objects. Finally, some may fear the administrative burdens that may be presented by spurious claims. The experience reported by museums that have implemented their legislation shows the opposite. Contrary to fears, large numbers of people did not come forward to claim objects. Moreover, implementation of the old loan statutes gave registrars a useful instrument to provide vacillating lenders incentive to make decisions on disposition of their loaned property.

Surprisingly, in the early 1990s, no state in the Mid-Atlantic Association of Museums (MAAM) had legislation specifically addressing unclaimed loans—despite considerable local interest in the topic.26 The Registrars Committee of MAAM, a group directly concerned with collection management, decided it was time to act more aggressively and, in 1992, established a task force to investigate unclaimed loan issues within the region. The task force, after documenting substantial unclaimed loan problems within the region, decided to produce a model unclaimed property law for museums—a model that could be used by interested parties within each state in the region as a starting point to draft legislative proposals tailored to the peculiarities of their particular states.

The model law was drafted in 1994. It had been written after a review of all state unclaimed loan statutes then in existence and with these objectives in mind:

1. To encourage museums and lenders to use due diligence in monitoring all outstanding loans

2. To allocate fairly the responsibilities between lenders and borrowers

3. To resolve expeditiously the issue of title to unclaimed loans currently in the custody of the museum27

Since the mid 1990s the number of states with unclaimed loan statutes grew from twenty-eight to forty-two by 2010. In addition, several more states are moving towards adopting unclaimed loan laws or seeking to expand laws now limited to their state museums.28 Reportedly, many of the states have used the model as a beginning step in the process of educating themselves and their professional colleagues about the essential problems. Some state statutes show that provisions of the model have been adopted into law. Users were also urged to review existing legislation in other states and then to assess the unique needs within their own state. See a copy of the model in Figure VII.2.29

Given the time, effort, and costs involved in resolving unclaimed loans, museums should institute safeguards to avoid this problem in the future As discussed in Chapter VI, “Loans: Incoming and Outgoing,” museums should borrow objects for a limited duration only (usually one year) with the expiration date specifically stated in the loan agreement. If the object is needed for a longer period, it is better to renew the loan than to agree to a longer initial term. More frequent contacts with lenders will avoid the missing lender situation. Loan agreements should specify that it is the lender’s obligation to notify the museum of a change in the lender’s address or a change in the ownership of the loaned object. Moreover, loan agreements should state that if, at the expiration of the loan, the museum is unable to contact the lender to make arrangements for the return of the object, the museum will store the object for a stated period of years at the lender’s expense. If, after this period, the lender still fails to come forward after notice by mail is sent by the museum to the lender’s address of record, the museum will deem that an unrestricted gift of the object is made by the lender to the museum. In effect, the loan agreement will put the lender on notice of the museum’s claim to the object after a set period of time if the lender fails to maintain contact or refuses to pick up the object. Even in states where the unclaimed loan statue may provide for other avenues of termination, the lender has agreed to this result in his contract with the museum. This deemed gift provision should prevail or at least provide an alternate mechanism (to which the lender agreed) for termination of his or her ownership rights should the matter ever reach litigation.

Figure VII.2

Model Museum Unclaimed Property Law

It is not surprising that objects left at the museum for identification, authentication, or examination are more likely to be left unclaimed than objects borrowed by the museum for exhibition purposes. Objects of negligible value may provide little incentive for their owners to return to claim them. To avoid this risk, see the discussion in Chapter IX, “Objects Left in the Temporary Custody of the Museum,” on temporary custody arrangements.

As a public trust, museums have legal responsibilities to make best use of their resources. Prudent collections management dictates that museums should ensure that current policies and procedures avoid unclaimed loans in the future.

Every museum faced with real or suspected unclaimed loan situations needs to do considerable investigatory work, starting with a careful review of internal records and progressing to outside inquiry. The first step is to determine whether the object at issue is indeed an unclaimed loan. Some evidence of a loan should exist before procedures to resolve a loan are set into motion. Absent standard documentation of a loan such as a loan agreement or an exchange of letters indicating a loan was intended, the museum may have only scant evidence that the object was loaned (such as a tag on the object with a number reserved in the past for labeling loans). But, at least, even then there is some evidence of the fact that legal title may belong to someone other than the museum. If the object is found without any documentation, Chapter X, “Objects Found in the Collections,” should be consulted. Researching unclaimed loans is a daunting project because one never knows how much work will be required or what the results may be. But as has been explained, waiting will not make unclaimed loan problems disappear, so a systematic investigation is the preferred route. “Systematic” is a key word here because a carefully plotted course of action will avoid the need to retrace steps and should produce the quality of documentation that is so important to the ultimate success of the undertaking.

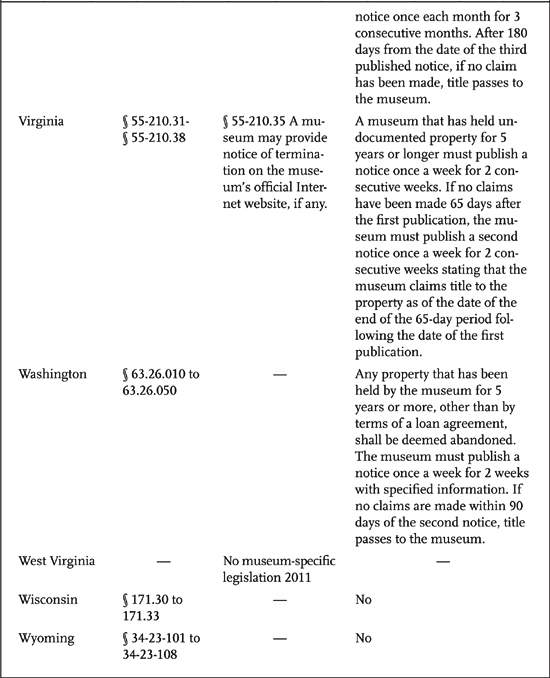

The following “practical guidelines” for organizing a systematic plan of action for resolving unclaimed loans (see Figure VII.3) were developed by Agnes Tabah in the mid-1990s in the course of tracing unclaimed loans in a large history museum situated in a jurisdiction that had no statute specifically addressing museum unclaimed loans.30 More recently, the guidelines have been adapted for searches using the online environment.

As we have seen, for both the common law approach and in some state unclaimed loan statutes, reasonable searches for lenders are often required. Within the last decade, the explosion of information available through the Internet prompted an inquiry as to whether paths of information suggested by Ms. Tabah might now be more easily accessible online and whether other avenues may be identified through a search of Internet resources. A group of George Washington University museum studies graduate students were given a selection of unclaimed loan files from the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History to use as case studies. The students were asked to limit their search initially to free Internet resources and to come up with a list of useful websites to supplement Ms. Tabah’s guidelines. Once this research was completed, two of these case studies were selected for further research using additional Internet resources for which small fees are charged to determine whether these fee-based resources were cost effective. The result of the project proved to be very positive. Lenders missing for years were easily found using Internet databases of newspaper obituaries, probate records, and telephone directories. In one case, spending $6.95 on a newspaper obituary database located the lender’s heirs; without that database such a search would have taken countless hours and a trip to the city where the paper’s archives were located.31

Figure VII.3

Practical Guidelines for Resolving Unclaimed Loans

Author’s Notes:

aSome state statutes do not distinguish between unclaimed loans and undocumented objects, in which case the museum will have to apply the statutory provisions to both types of objects.

bFor further discussion and guidelines on how to treat objects found in the collections, see M. Malaro, “Practical Steps toward Resolving Ownership Questions,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1984), 556–58.

cAs illustrated by In re Estate of McCagg, 450 A.2d 414 (D.C. 1982), a case discussed in Chapter VII, Section B, a museum that is deemed not to have made a diligent attempt to find the lender may not prevail in an action to take title to objects on loan. One may wonder, at least in cases in which the loan in question is decades old, whether the court has set a standard of conduct that is impossible for most museums to reach. Many years ago, collections management procedures and registrarial record-keeping standards were not what they are today, and it may be unrealistic for courts to expect museums to have made systematic searches for all lenders given the prevailing standards of practice at that time.

dTwo or more people may come forward to claim the object. If so, the museum should encourage the claimants to settle among themselves the question of who owns the object. If they fail to do so, the museum, as a last resort, may deposit the object with a court in an interpleader action and let the court decide to whom the object legally belongs.

eAs already noted, two or more heirs may claim title to an object. In that case, follow the recommendations in footnote d.

fIn re Estate of McCagg, 450 A.2d 414 (D.C. 1982).

gSee Chapter XIII, Section A, for more discussion of appraisals.

Figure VII.4

Sample Worksheet for Resolving Unclaimed Loans

Figure VII.5

Sample Letter of Notice to Terminate Loan

The increase in online resources ultimately will shape what constitutes a reasonable search for missing museum lenders. So the definition is expected to change as online resources expand. Much of the information that is useful to museums in solving unclaimed loan cases is publicly held, usually by federal, state, and local governmental offices, such as vital (death) records, probate records, and tax and real estate records. As these offices increasingly computerize their data, more and more of this information will become accessible online. The Internet also features many general resources websites that serve as “informational portals” on how to obtain public records and, in some cases, that provide links to search sites specializing in public records databases. Many general resource sites have been established to aid certain types of researchers, most notably, amateur genealogists, such as the popular Ancestor.com website. Often, on some of these sites free searches turn into fee-based service requiring a small payment or an annual membership for more advanced searches. Specialized information Internet sites include alumni listings, cemetery obituary listings, telephone directories, and people search sites.

Figure VII.6

Sample Receipt and Waiver by Lender on Return of a Loaned Item

The Registrar’s Committee of the American Association of Museums (RCAAM) has posted online a list of websites that may be useful for searching for lenders. These websites were culled from previous publications on searching for missing lenders on the Internet, including the George Washington University museum studies project.32 Unfortunately, this list has not been updated since 2004. A project to update Internet resource lists as well as to share information on resolving unclaimed loans would be ideal for a wiki website similar to the Rights and Reproduction Information Network (RARIN) established by RCAAM for sharing by users of rights and reproduction information. The museum profession would benefit greatly from having a single website that lists all the resources of interest to museum staff in solving old loans and that is current and continually updated by users. In effect, such a website may establish profession-wide standards that a court might look to for guidance in judging what should be required for reasonable searches.

1. The museum should remember that a distinguishing feature of the unclaimed loan is the inability of the museum to identify and/or locate a lender with relative ease. This is not a situation in which the museum knows where to reach a lender but chooses to retain a loan on an indefinite basis. In this later case, the museum has little basis for arguing that it is being unjustly imposed on by the lender. It is also important to note that old or unclaimed loans do not include undocumented objects found in a museum’s collection that lack any information as to how they were acquired. This chapter deals with objects that are accompanied by some evidence or documentation that a loan to the museum was intended by the owner. With found objects, there is no evidence held by the museum that someone else owns these objects. Rather, the museum’s undisturbed possession for an extended period supports a presumption that ownership was transferred to the museum at the time the objects were acquired. See Chapter IX, “Objects Left in the Temporary Custody of the Museum,” and Chapter X, “Objects Found in the Collections.”

2. L. Wise, “Old Loans: A Collections Management Problem,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1990), 44; A. Tabah, “The Practicalities of Resolving Old Loans: Guidelines for Museums,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1992) 317;_I. DeAngelis, “Old Loans: Laches to the Rescue?,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1992) 202.

3. This discussion does not include so-called “permanent loans.” This term was used in the profession some years ago. Loans by definition are temporary, and therefore it is unclear what the parties had in mind when the arrangements for permanent loans were made. See a discussion in Chapter VI, “Loans: Incoming and Outgoing,” Section A.7, “ ‘Permanent’ Loans.” Often a review of the museum’s records may indicate that a gift was actually intended or completed. However, if title to the object still rests with the lender, then permanently loaned objects should be treated as loans of unlimited duration.

4. State laws on abandoned property are of little or no help. For years, most states have had statutes that address abandoned property. These laws deal primarily with intangible property of value (such as money left in bank accounts) and only some limited categories of tangible property (objects of value, such as jewelry) left in bank vaults and other corporate safekeeping depositories. The laws vary from state to state, but generally the abandoned tangible property is held by the state for a period of time (for example, three years), and if no one comes to claim it, the objects are sold by the state at public auction and the value of the property escheats to the state’s coffers as an additional source of revenue until the owner comes to claim it. See Uniform Unclaimed Property Act (1995), accessed Apr. 7, 2011, http://www.law.upenn.edu/bll/archives/ulc/fnact99/1990s/uupa95.pdf. Classifying an unclaimed loan to a museum as “abandoned property” is very difficult. Under the general common law doctrine of abandonment, the law requires proof of the owner’s intention to abandon the property, as well as some affirmative act or omission demonstrating that intention. The burden of proof rests with the party claiming ownership by default. See the trial court decision of Hoelzer v. Stamford, 933 F.2d 1131 (1991), 972 F.2d 495, cert. denied, 506 U.S. 1035, 121 L.Ed. 2d 687, 113 S. Ct. 815 (1992). When an object has been lent to a museum, inferring an intention to abandon title merely because the owner has not been heard from for a long time is problematic. Accordingly, the common law doctrine of abandonment has rarely, if ever, been used effectively in cases of this nature. Also, most statutes regulating abandoned property require that the property be turned over to the state. Accordingly, a state “abandoned property” statute is rarely helpful to a museum. When writing a state statute that specifically addresses unclaimed loans, however, any state abandoned-property statute should be cross-referenced, and any ambiguities regarding the application of each should be clarified.

5. See list of State Unclaimed Loan Statutes in Figure VII.1 below.

6. In addition to the statute of limitations, two other defenses, the equitable doctrine of laches and the doctrine of adverse possession, may have some application to unclaimed loan cases. For the reasons explained below, these defenses are limited and may be of questionable effectiveness in unclaimed loan situations. “Laches” is an unreasonable delay that makes it inequitable to give the relief sought. See a discussion in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section D.5, “Stolen Property.” The defense usually is available if there is evidence that a party negligently delayed making a claim or enforcing a right and that this delay actually prejudiced the other party. In such cases, the law may infer a waiver of all claims by the negligent party in order to avoid injustice to the prejudiced party. In an unclaimed property situation, the bailee/museum would have to show that the claimant knew or should have known that the claimant was sleeping on his or her rights. In other words, the claimant should have known to come forward to retrieve the loan or otherwise lose the object. Establishing the negligence aspect of laches carries with it the same or similar problems one encounters when trying to establish that a statute of limitations has begun to run. For example, if a loan was for an unlimited duration, how can one show negligence for failing to come forward if the initial understanding was that the loan could go on indefinitely? A second problem concerns proving prejudice to the museum from failure of the lender to come forward. Often courts tend to see the museum’s continued possession of an object as a positive benefit rather than as a detriment. A bailee/museum might be able to prove such prejudice if, for example, it can demonstrate that the undue delay has blurred evidence by which it could have shown that a deceased lender intended to make a gift of the property, or that the object in question has become very important to the collections and, if removed now, could not be replaced, or that timely notice would have put the bailee/museum in a better position to negotiate a gift or purchase of the property, or that timely notice would have saved it the expense and frustration of years as an involuntary bailee. If the museum has actually disposed of the property in good faith, it may well have a basis for proving prejudice when a long overdue claim is presented. As explained in this chapter’s Section E, “Researching Unclaimed Loans,” a more recent New York court decision places greater emphasis on the doctrine of laches in situations in which two parties are arguing over title to stolen property. See the discussion in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section D.5, “Stolen Property.” See also I. DeAngelis, “Old Loans: Laches to the Rescue?,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1992).

The other legal doctrine that may come into play in an unclaimed property situation is adverse possession. Adverse possession is a method of acquiring title by possessing something for a statutory period of time under certain conditions. See the discussion in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section 5.b, “Adverse Possession.” The conditions are that the possession must be hostile (adverse to the owner), actual, visible, exclusive, and continuous. The doctrine is associated, as a rule, with real property, where someone takes and uses land belonging to another. In O’Keeffe v. Snyder, the New Jersey Supreme Court found that the doctrine of adverse possession did not provide a fair and reasonable means of resolving disputes involving personal property and held that the doctrine did apply in New Jersey to personal property. The problem is in proving hostile and visible possession sufficient to give notice to the owner to come forward to protect his property interests. Bailment is by its nature a voluntary nonhostile arrangement. Whereas with real estate, a hostile claim is not difficult to discover, with movable tangible personal property, this is not the case. 170 N.J. Super. 75, 405 A.2d 840 (1979), rev’d, 83 N.J. 478, 416 A.2d 862 (1980). See also Naftzger v. American Numismatic Society, 42 Cal. App. 4th 421 (1996). See also Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section D.5, “Stolen Property.”

7. See also a discussion of statutes of limitations in Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section D.5, “Stolen Property.”

8. 101 U.S. 135, 25 L.Ed. 807 (1879).

9. Ibid., 139.

10. In Bufano v. San Francisco, 233 Cal. App. 2d 61, 43 Cal. Rptr. 223 (1965), an artist sued the city for two of his sculptures that had been held by the city for seventeen years. The court held that a statute of limitations would not begin to run until the owner was on notice that the city claimed the sculptures as its own.

11. See U.S. Const. amend. XIV, §1.

12. In re Estate of McCagg, 450 A.2d 414, 418 (D.C 1982).

13. Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank and Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306, 70 S. Ct. 652, 94 L.Ed. 865, 875 (1950). See also Mennonite Board of Missions v. Adams, 462 U.S. 791, 103 S. Ct. 2706, 77 L.Ed. 2d 180 (1983); Cunnius v. Reading School District, 198 U.S. 458, 25 S. Ct. 721, 49 L.Ed. 1125 (1905); Blinn v. Nelson, 222 U.S. 1 (1911).

14. In a case involving the IRS’s failure to provide adequate notice to a taxpayer, facts showed that the IRS only searched for the individual in its internal computer system. The district court stated that “[w]hat constitutes reasonable diligence will vary according to the information available to the [institution], including any notice from the [missing individual]…. More importantly, the test is fact specific and must be addressed on a case by case basis.” United States v. Bell, 183 B.R. 650, 653 (S.D. Fla 1995). The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals also held that it was the duty of the IRS to use “reasonable diligence” in its search for a taxpayer’s last known address in Mulder v. Commissioner, 855 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1988).

15. Mullane, 339 U.S. at 314-15, 70 S. Ct. at 657, 94 L. Ed. at 873.

16. Other factors that should also be considered in determining whether the search to provide notice meets constitutional due process include “the length of time the object must be [left] on loan before the museum is permitted to give notice of its intent to terminate the loan, whether the lender was ever advised that he must keep the museum informed of any change in address or name, …” as well as the number of years the museum has been without contact from the lender. See J. Teichman, “Old Loan Legislation: Legal Concerns and Update,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1986) 409, 418 n.8.

17. One subject that deserves more attention by the museum profession is the cost of maintaining a collection object. All too frequently, museums assume that care or “storage” is a minor budgetary item that is of little significance in weighing the relative duties of lender and borrower. Some preliminary work in this area demonstrates that storage and/or exhibition of art objects and curation of scientific specimens involve substantial costs and that loans or “deposits” to museums should be judged accordingly. With facts and figures on the cost of care available, a judge may pause before finding an indefinite loan of fifty years “reasonable.” On the subject of the care of scientific specimens, see W. Marquardt et al., “Resolving the Crisis in Archaeological Collections Curation,” 47 American Antiquity 409 (No. 2, 1982); The Curation and Management of Archaeological Collections: A Pilot Study, Cultural Resources Management Series (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, 1980); T. Nicholson, “The Obligation of Collecting,” Museum News 29 (Oct. 1983). The North Idaho Regional Laboratory of Anthropology at the University of Idaho and the Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of South Carolina have developed fee schedules that reflect the actual costs of curation and storage. At the 1983 ALI-ABA conference on Legal Problems of Museum Administration, a presentation discussed the cost of maintaining a museum object as this relates to “indefinite loans.” It was pointed out that a true analysis of cost should include such factors as recording, periodic inventory, maintaining accessible records, environmental pest control, storage equipment, security, conservation, insurance, and general overhead, including management and building expense. Display can add considerably more to cost, especially if one realistically calculates total space used to create the ambience necessary for effective presentation. For more specific figures, see W. Washburn, “Collecting Information, Not Objects,” Museum News 5 (Feb. 1984). The cost of caring for museum collections has become of even greater concern as each year passes. In a 1996 presentation, Willard Boyd, then director of the Field Museum of Natural History and an articulate member of the Institute of Museum Services’ National Museum Services Board, listed one of the major challenges facing the museum community in the new century: “[M]useums need to be more specific and focused in their collecting. Furthermore, whatever is collected must be conserved and protected. Dollars for collecting must be matched by dollars for conservation.” W. Boyd, “The Institute for Museum Services,” AAM Sourcebook 1996 (Washington, D.C.: AAM, 1996). See also B. Lord, G. Lord, and J. Nicks, The Cost of Collecting: Collection Management in UK Museums (London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1989).

18. The genesis and implementation of the California statute is well documented. See J. Teichman, “Museum Collections Care Problems and California’s ‘Old Loan’ Legislation,” 12 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 423 (Spring 1990); and J. Teichman, “Common Collections Management Questions: Who Owns Old Loans and Undocumented Property, and Are We in Compliance with Our Old Loan Legislation?,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1995).

19. As noted earlier in this chapter’s footnote 1, undocumented property or “objects found in the collections” (see Chapter X, “Objects Found in the Collections”) normally carry a presumption that they belong to the museum. Subjecting this type of object to the same procedures as required for unclaimed loans actually works to the detriment of the museum because the burden of proof is shifted.

20. For example, Virginia permits a notice of loan termination to be posted on a museum’s website in addition to more traditional methods of notice sent by mail or by print publication. New Jersey’s law, signed into law on August 19, 2011, states the following: “In addition to the method of notice designated in subsection a [by newspaper] a museum may, whenever practicable, use an emerging technology to publish such notice in order to reach as broad a circulation as possible.” (New Jersey bill # S1882)

The Code of Virginia states the following:

§ 55-210.35. Notice of termination of loan

A. A museum may provide notice of termination on the museum’s official Internet website, if any, or may give written notice of termination of a loan of property at any time if the property was loaned to the museum for an indefinite time. If the property was loaned to the museum for a specified term, the museum may give notice of termination of the loan at any time after the expiration of the specified term. (2002, c. 883.)

21. See § 1899.10 of Cal. Civil Code.

22. J. Teichman, “Museum Collections Care Problems and California’s ‘Old Loan’ Legislation,” 12 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 423 (Spring 1990).

23. See § 1899 of Cal. Civil Code.

24. N.Y. Educ. Law § 233-aa states the following: “Proceeds derived from the sale of any property title to which was acquired by a museum pursuant to this section shall be used only for the acquisition of property for the museum’s collection or for the preservation, protection, and care of the collection and shall not be used to defray ongoing operating expenses of the museum.” In addition, special provisions apply to any property that was created before 1945 and changed hands due to theft, seizure, confiscation, forced sale, or other involuntary means in Europe during the Nazi era (1933–45).

25. In 1995, in preparation for a panel on “old loans” at the annual conference Legal Problems of Museum Administration, contacts were made with museums located in states where unclaimed loan legislation was in place to discover whether the laws on the books were being implemented. Due to the limited numbers in the pool of those contacted, the survey was not intended to be scientifically reliable. However, the responses as reported orally indicated that the legislation had not been used widely for reasons of limited staff resources to deal with unclaimed loans and hesitancy to contact lenders for fear of administrative burdens. I. DeAngelis, “Model Museum Unclaimed Property Law for the Mid-Atlantic Region and Citations to Existing ‘Old Loan’ Legislation,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1995).

26. States within MAAM are Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.

27. I. DeAngelis, “Model Museum Unclaimed Property Law for the Mid-Atlantic Region and Citations to Existing State ‘Old Loan’ Legislation,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1995), 299, 303.

28. As of late 2010, three additional states are in the process of passing unclaimed loan laws. They include Oklahoma, New Jersey (signed into law August 19, 2011), and Connecticut.

29. Cochairs of the task force were Jeanne Benas, Office of the Registrar, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and Jean Gilmore, Registrar, Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pa. Legal adviser was Ildiko DeAngelis, Office of the General Counsel, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. As of mid-1997 no state in the MAAM region had yet adopted unclaimed loan legislation.

30. Agnes Tabah was then a student in the graduate program in museum studies at the George Washington University, Washington, D.C. Tabah, who also holds a law degree, gained practical experience in tracing unclaimed loans while serving an internship at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. She made a presentation of these guidelines at the 1992 American Law Institute–American Bar Association conference Legal Problems of Museum Administration, copyright 1992. The substantial reprinting of these guidelines is with the concurrence of Tabah and the American Law Institute–American Bar Association Committee on Continuing Professional Education.

31. Graduate students and faculty of the Museum Studies Program, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., “Resolving Unclaimed Loans Using the Internet: Resources and Case Studies,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2002), accessed May 20, 2011, http://www.rcaam.org/publications/ALIABA-GWUpaper.doc.

32. See http://www.rcaam.org/publications.htm, accessed May 10, 2011.