The Country’s Most Famous School

Amongst the idyllic English landscapes by Turner and Constable and the instantly recognizable masterpieces of Michelangelo and van Gogh hangs its portrait in the National Gallery in London. Only one work on permanent display in one of the world’s finest collections of European art depicts an educational institution.

A beautiful white chapel stands as it does today amid the school’s distinctive buildings on the banks of the River Thames. Though he probably finished the artwork later on in Venice, art historians believe the Italian painter Canaletto produced his original sketch of the scene around 1747.1 The painting is a vivid reminder of how long the world’s most famous school has commanded a prominent role in our national life. No, it is not Hogwarts. It is, of course, Eton College.

When Canaletto painted the school, Eton was already 300 years old and had produced a host of prime ministers, famous writers and scientists.2 In 1440 King Henry VI had established Eton as a pure engine of social mobility: providing free education for seventy poor boys to go on to King’s College, Cambridge. But then, as now, the need to finance the school meant it had no choice but to charge fees for the children whose families were able to afford it.

That model has had remarkable success over six centuries: Eton continues to influence modern public life in Britain in the early twenty-first century, nearly 600 years after it was founded. ‘Probably the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, but the opening battles of all subsequent wars have been lost there,’ George Orwell claimed in his wartime essay, The Lion and the Unicorn, in 1941.3 Orwell, who had enjoyed his time at Eton, used the famous words attributed to the Duke of Wellington to argue that an outdated British class system was hampering the war effort. But eighty years on, Eton, alongside the nation’s other leading independent schools, is winning the battle that matters most. Far from decaying, the ruling class is in rude health.

A 2012 study of the school and university backgrounds of 8,000 of the country’s most prominent people across a range of professions found Eton produced 330 leading people – 4 per cent of the nation’s elites – including the Prime Minister, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and many more illustrious names.4 It is an impressive number for one school; particularly given there are over 4,000 secondary schools across the country, both state and privately funded.

David Cameron was the nineteenth prime minister educated at Eton. And the inner circle of fellow Etonians who surrounded Cameron prompted one of his closest allies, Michael Gove, to criticize the clique of education elites at the heart of Government.5 Apart from everything else, Etonians are adept at deflecting and assimilating any opposition. ‘What chance have you got against a tie and a crest?’ the singer-songwriter Paul Weller wrote in a 1982 song entitled ‘Eton Rifles’. Weller’s lyrics were an angry protest against Eton and the enduring elites presiding over the country. In 2009, much to Weller’s chagrin, Cameron declared it was one of his favourite records when he was a young man at Eton, apparently not picking up on the feelings of injustice the song expressed.6

It is not just in Government but in all walks of public and professional life that Etonians flourish. In 2015 London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, himself Eton-educated, used the race for an Oscar between two privately educated actors to highlight the lack of state-educated actors Britain produces.7 The Eton-educated actor Eddie Redmayne edged out his Harrovian rival Benedict Cumberbatch to win the 2015 best actor award. Johnson argued it was ‘decades since we had a culture of bright kids from poor backgrounds who exuberantly burst down the doors of the establishment’.

Alumni of the Clarendon schools, made up of Eton and Harrow and seven other prestigious public schools, are 94 times more likely to be members of the British elite than those who attended any other school, another study found.8 Even this figure may underestimate the ‘propulsive power’ of the schools. It is based on how likely former students are to feature in Who’s Who – a catalogue of British professional elites. The country’s public school boys made up a larger share of leaders 120 years ago, yet this may be because modern elites shy away from public attention. Public school old boys once sought fame serving the nation overseas as military or political leaders; now they are just as likely to hide away in offshore tax havens as hedge-fund managers.

Private Elites

In a 2012 study the Sutton Trust found that ten exclusive private schools supplied one in eight of Britain’s elites. The ten schools were: Eton, Winchester, Charterhouse, Rugby, Westminster, Marlborough, Dulwich, Harrow, St Paul’s Boys’ School and Wellington College. Just under half of top people in Britain – 45 per cent – had attended a private school, although these make up only 7 per cent of all the country’s schools.

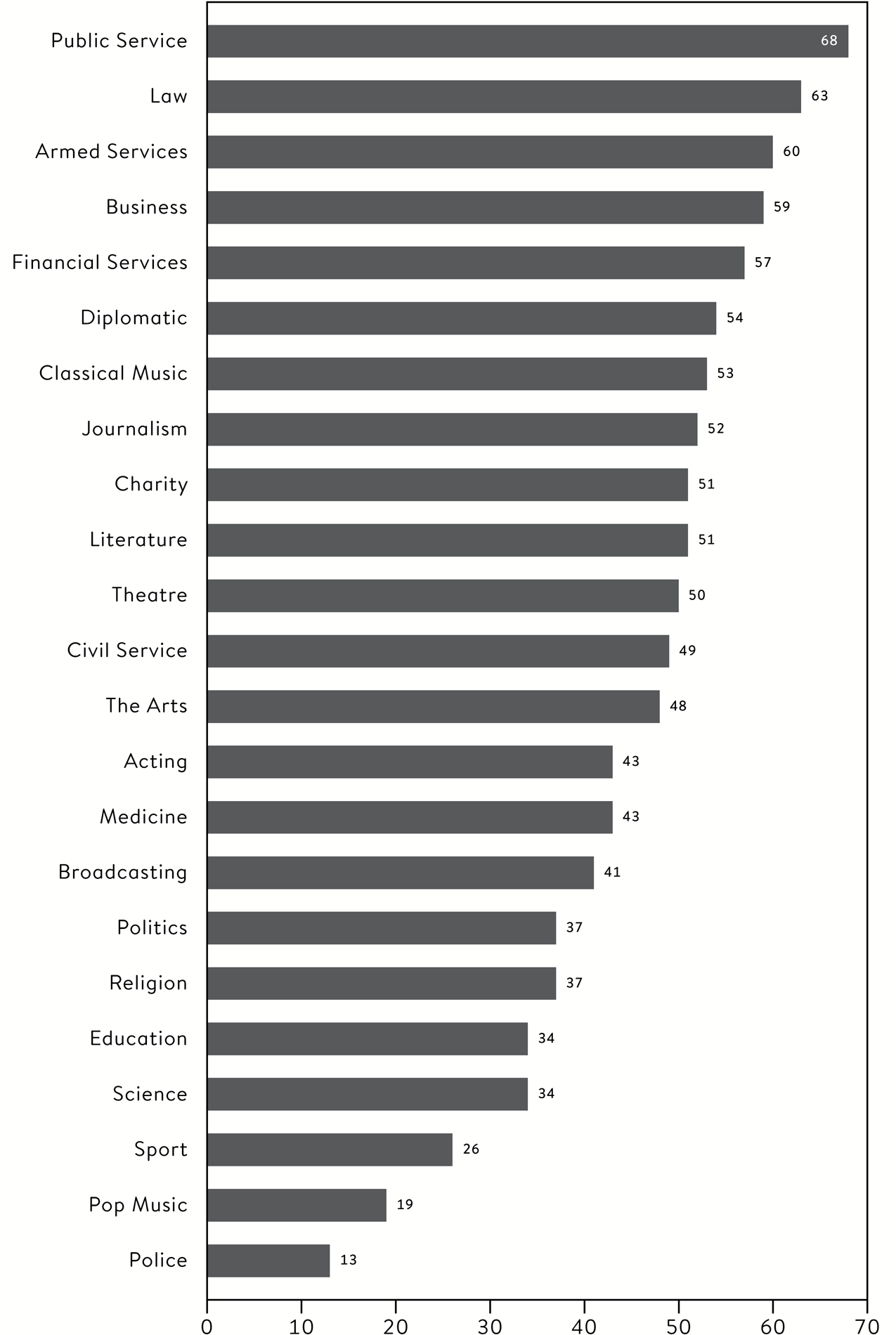

Figure 6.1 shows the proportion of privately educated leaders across a range of different professions. The data reveal unlikely education bedfellows. Leading people in law and the armed services are among the most likely to have been privately educated; prominent figures in popular music and the police force on the other hand are the least likely, but still well above 7 per cent of those at the top.

A glittering array of private school alumni range from some of the country’s most loved actors such as Jeremy Irons, Daniel Day-Lewis, Hugh Laurie, Rowan Atkinson and Kate Winslet to prominent broadcasters including Jeremy Paxman, Tony Blackburn, Jeremy Clarkson and the Dimbleby brothers. Famous sportsmen included Chris Hoy, Alastair Cook, Jonny Wilkinson and Tim Henman; leading musical talents, meanwhile, included Brian Eno, Lily Allen and Charlotte Church.

Another Sutton Trust study in 2016 found three-quarters (74 per cent) of the top judiciary (in the High Court and Appeals Court), 71 per cent of the top military brass (two-star generals and above) and over half of leading print journalists, bankers and medics were privately educated.10 Several studies have replicated these findings. The privately educated not only make up large proportions of today’s political and professional elites, but leading people in other areas of public life, including the film and TV industry, the arts, music and sport.

Percentage in selected professions who were privately educated (2012).9

‘In every single sphere of British influence, the upper echelons of power in 2013 are held overwhelmingly by the privately educated or the affluent middle class. To me from my background, I find that truly shocking,’ said Sir John Major, the former state-educated prime minister. ‘Our education system should help children out of the circumstances in which they were born, not lock them into the circumstances in which they were born.’11

Reprising Wellington’s famous words, the government-funded Social Mobility Commission found Britain’s elites had been ‘formed on the playing fields of independent schools’. In 2014 it reported that 50 per cent of members of the House of Lords, 44 per cent of the Sunday Times Rich List, 43 per cent of newspaper columnists, 35 per cent of the national rugby team and 33 per cent of the England cricket team had attended independent schools.12

In 2012 over one-third (36 per cent) of British medal winners in the London Olympics were educated at fee-paying schools.13 The findings prompted a debate over whether Olympic sport had become elitist, missing out on sporting talent across the country. At least a third of the ‘100 British celebrities who really matter’ – a list compiled for the Daily Mail in 2010 – had also attended fee-paying schools. They included Simon Cowell, Sienna Miller, Holly Willoughby, Jude Law, Eddie Izzard, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Chris Martin (of the band Coldplay), Richard Branson and the footballer Frank Lampard.14

Higher Echelons

Another recurring finding is that the higher you climb up the career ladder in modern Britain, the more likely you are to be privately educated. While a third of MPs attended independent schools, half of the Cabinet in 2015 did so. Half of leading lawyers were privately educated compared with 70 per cent of High Court judges. Half of leading bankers went to private schools; yet over 70 per cent of those working in exclusive hedge funds and private equity firms did so.15

This pattern for the highest achievers is observed for film actors too, with over two-thirds (67 per cent) of British winners of Oscars having been educated at independent schools.16 One of the few industries to buck the trend is popular music, where just over four-fifths (81 per cent) of British solo BRIT winners were state-educated. Although in classical music the pattern is reversed: three-quarters (75 per cent) of British Classic BRIT winners attended private schools.

Staying Power

The data for recent decades suggests these proportions of privately educated elites have stayed remarkably constant in many professions. In law, for example, 76 per cent of top judges had attended private schools in the late 1980s, 75 per cent by the mid-2000s and 74 per cent in 2016.17

The same can be said for leading news journalists, despite the profound changes experienced by the media industry in the early twenty-first century. Just over half (51 per cent) of editors, presenters and prominent commentators in 2016 were privately educated. This is slightly lower than the 54 per cent of leading news journalists educated in private schools in 2006, but higher than the 49 per cent of top journalists in 1986.18

Research by The Times found little change in the percentage of privately educated people selected for honours over the past sixty years: nearly half of the recipients of knighthoods and above in 2015 were privately educated. The figure – 46 per cent – had hardly changed since 1955, when it was 50 per cent.19

Looking at the last twenty-five years of Oscars, meanwhile, the proportion of privately educated British winners has remained remarkably stable at 60 per cent, with over a quarter (27 per cent) from state grammar schools and the remainder (13 per cent) from state comprehensives. This is despite the changing make-up of the state sector, including the phasing out of grammar schools during the period in which these actors were educated.

Business leaders buck this trend. But this is because far more foreigners now run businesses in Britain. The proportion of FTSE 100 chief executives educated at independent schools has fallen from 70 per cent in the late 1980s, to 54 per cent in the late 2000s, to 34 per cent in 2016.

The proportion of privately educated Members of Parliament fell from 49 per cent in 1979 and 51 per cent in 1983 to around a third in more recent Parliaments.20 In 2015 the proportion was 32 per cent.21 But the education backgrounds of MPs holding the most senior Government positions in Cabinet have stayed fairly constant. Half of the Conservative Cabinet in 2015 was privately educated; this was lower than the preceding 2010 Coalition Cabinet (62 per cent), but slightly higher than Tony Blair’s Cabinet (44 per cent) immediately after the 2005 general election. The 2016 Conservative Cabinet appointed by Prime Minister Theresa May had only 30 per cent privately educated members – the lowest proportion since the Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee in 1945.22

Comparable data for previous decades is harder to come by, but sociologists made similar observations when studying elites in the early 1970s. They found ‘the extraordinary near monopoly exerted by the public schools in general, the influence of the Clarendon schools in particular, and of Eton especially, over elite recruitment in this country.’23

Future Runes

The emerging evidence on the latest generations trying to climb the first rungs of the career ladder indicates these patterns are likely to continue for future leaders. Senior newspaper editors reported that private school alumni exhibited the stronger skills and attributes needed to progress in a highly competitive industry at an earlier age. They reported that the most recent recruits to the national news media are more likely to come from privileged backgrounds than those from previous generations.24

These arguments echo those articulated by a number of prominent actors that the acting industry is increasingly becoming the preserve of those from more privileged backgrounds.25 The data shows those from working-class backgrounds made up 18 per cent of people in the cultural and creative industries compared with just under 35 per cent in the general population. Publishing was among the industries with a particularly middle-class make-up. ‘These findings clearly puncture romantic notions of these industries as paragons of merit and accessibility,’ the authors concluded. Access to an agent, entering drama school and taking on unpaid work were the reasons cited for the increasing lack of diversity.26

Over a third of recent entrants in the financial services industry were found to have attended private schools.27 A report on the socio-economic diversity in the civil service Fast Stream found it had a less diverse intake than the student population at the University of Oxford.28

Academic Benefits

This career success is underpinned by the significant academic and social benefits a private education offers. An analysis in 1984 reported that private schools produced a remarkable improvement in academic performance between 1961 and 1981. By the end of this period 45 per cent of students were achieving three or more A levels, compared with 14.5 per cent at the beginning. This compared with an increase in the state sector from 3.1 per cent to 7.1 per cent.29

In 2016 just under half of A-level entries (48.7 per cent) from pupils based in the 495 private schools represented by the Independent Schools Council were awarded an A* or A grade, compared with just over a quarter (25.8 per cent) of entries that had done so nationally.30

One of the problems with these types of comparisons is they don’t take into account that many highly selective independent schools attract high-achieving students to begin with; it is unclear how much the final A-level results are due to what the school is adding, and how much they are due to outside factors associated with the students themselves.

Private school pupils are on average two years ahead academically of their counterparts in state schools by the age of 16, even taking into account the social background and prior attainment of children.31 This equates to independently educated pupils gaining an extra 0.64 of a grade for each of their GCSE examinations at age 16.

Private schools boast an impressive record in the numbers of pupils they send to the country’s most prestigious universities, who supply the lion’s share of graduates for many elite careers. This is demonstrated at its most extreme in admissions to Oxford and Cambridge. A Sutton Trust study found four private schools and one sixth-form college sent more pupils to Oxbridge over three years than 2,000 other schools and colleges across the UK.32 The five were made up of four private schools – Westminster, Eton, St Paul’s, St Paul’s Girls’ School – and the state-funded Hills Road sixth-form college.

Meanwhile 100 schools, making up 3 per cent of schools with sixth forms and sixth-form colleges in the UK, accounted for just under a third (just under 32 per cent) of admissions to Oxbridge during the three years. These schools were composed of 84 independent schools and 16 grammar schools. A separate analysis found private-school students were 55 times more likely to win a place at Oxbridge than students at state schools who qualified for free school meals.33

The superior academic results of privately educated pupils explain much of these university enrolment figures; studies suggest they are also more likely to apply to prestigious degree courses, an indication of the extra advice and support they receive. Pupils from top-performing independent schools on average made twice as many applications to leading universities than their peers from state comprehensive schools with similar average A- level results.34

But once at university, a more mixed picture emerges. Privately schooled students are less likely to leave university with a first- or an upper-second-class degree than state-educated graduates.35 The study reported 73 per cent of independent school students graduated from English universities in 2013–14 with the two top degree grades. This compared with 82 per cent of state school leavers.

This gap remained when taking into account the subject studied at university. But the difference disappeared for students from different school backgrounds with the highest A-level grades. One explanation for the differences is that private schools maximize the academic potential of their pupils, but many state school pupils achieve lower A-level grades than they might otherwise have done if given more support.

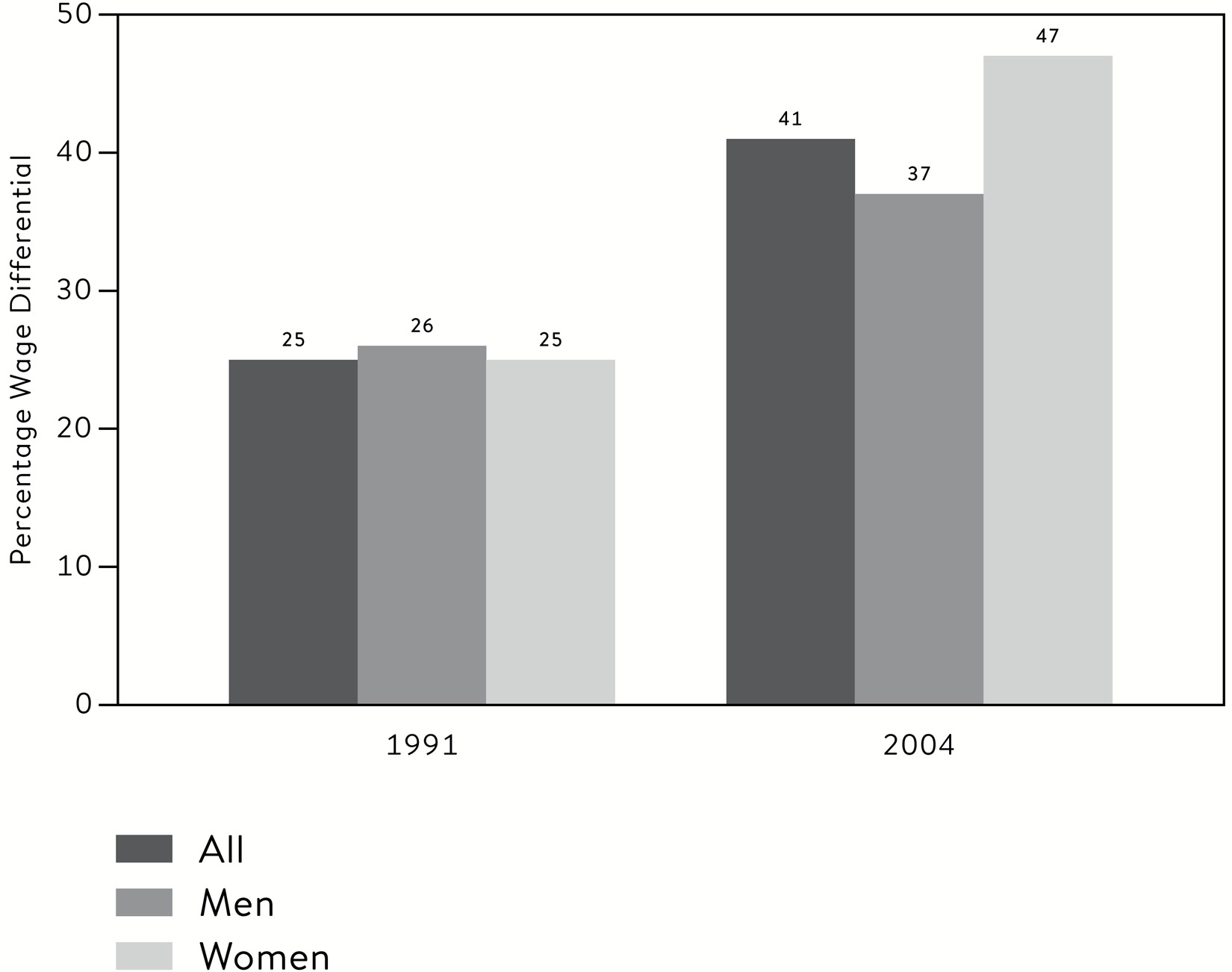

Despite this, other studies have found an increasing pay premium from studying at private school.37 Our own analysis of the figures confirms these wage differentials, presented in Figure 6.2. In 1991, privately educated 33–34-year-olds were earning on average 25 per cent more than their otherwise similar state-educated counterparts. In 2004, the pay premium for privately educated 33–34-year-olds had increased to 41 per cent more than their state-educated peers. This wage boost is particularly large for women.

Private / State school wage differentials for 33–34-year-olds.36

Non-academic Benefits

While less quantifiable, studies suggest a range of non-academic benefits are associated with private schooling. These attributes are given various names: social, soft, non-cognitive or essential skills. They include drive, resilience, grit, effective communication, a strong work ethic, as well as confidence, ‘polish’ and ‘character’ – all apparently highly valued by employers.

We have shown that privately educated graduates are significantly more likely to enter top occupations. But research also shows they manage to do this with the same academic grades as their state-school peers. A study found a ‘sizeable difference’ in entry rates into elite professions by the type of school attended.38 This could be due to unmeasured personal assets and advantages, including human capital (wider knowledge, skills and attributes); cultural capital (for example, being able to converse on a range of topics during interviews); and financial capital (money allowing the privately educated graduate to survive on unpaid internships and low salaries during the early years of their career).

These attributes, whether social, cultural or financial, may partly account for another finding: the higher chances of privately educated applicants gaining places at elite universities. The proportion of university entrants going to Oxbridge from the 30 top-performing independent schools was nearly twice that of those from the 30 top-performing grammar schools – despite having similar average A-level scores.39

Other research has suggested these social skills are what elite firms demand when defining the ‘talent’ they are seeking from potential recruits.40 Powerful alumni networks meanwhile maintain strong links among former students in many private schools, yielding invaluable connections that open up work opportunities. They are conspicuous by their absence in the state sector.41 Even at Cambridge and Oxford, public school products can stick together in their own cliques, embodied most famously by the Bullingdon Club at Oxford.42

No place nurtures these life skills more than Eton, and its alumni are feted for having a particular charm and confidence, enabling them to prosper in life after school.43 Indeed it is the pastoral care offered that is the reason given for the escalating fees at Eton and other leading private schools – raising concerns the schools are out of bounds for all but the most privileged.44

The Significance of Rising Fees

Focusing on private schools provides a partial picture of the educational backgrounds of Britain’s elites. Another striking feature is how few state-comprehensive educated leaders remain once the numbers of private and grammar school alumni are combined.45 Studies also show the country’s leading state schools are highly socially exclusive.46 But private schools are of particular interest from a social mobility perspective precisely because they have been so successful in producing high achievers over successive generations. The problem is that they are only accessible to the small minority of the population able to afford the fees required to get in.

In 2015 a survey found parents were paying more than £15,500 a year on average to send their son or daughter to a fee-paying school.47 At Eton the annual fees were just under £36,000 a year.48 These charges are prohibitive for most people; the estimate for the median household disposable income for the same year was £25,600.49

Private schools are increasingly out of reach for all but the most wealthy. One analysis suggested fees had quadrupled between 1990 and 2015, putting the average price of sending two children to private school above half a million pounds – around double the average house price in the UK.50 Even with two parents working, many middle-class families would struggle to educate their children privately. Another analysis suggested fees were at their least affordable for middle-class parents since at least the 1960s.51

At boarding schools, including Eton, the proportion of places taken by children from wealthy families abroad is steadily increasing.52 Another study found independent schools award on average just under 8 per cent of their income to bursaries and scholarships; this proportion was lower for the highest performing schools. Only half of this money to offset fees was going on means-tested bursaries for poorer families.53

Social Mobility Concerns

The combination of educational success and lack of access for children from all but the wealthiest backgrounds makes private schools powerful vehicles of intergenerational persistence. They are the glue maintaining the stickiness at the top of British society. And the glue appears to be getting stronger.

But their success poses major challenges for the nation as a whole. The risk of having such high proportions of people at the top of society from the wealthiest homes is they have a limited perspective or even a ‘group think’ mentality when deciding on issues that impact on the 93 per cent of the population from less affluent backgrounds.54 This could have societal as well as economic costs. In his 1958 book, The Rise of the Meritocracy, Michael Young warned of the dire consequences of a society where most of the population have scant chance of climbing the social ladder.55 We will come back to Young’s prophetic warnings.

The country is also failing to fully nurture talent from the majority of the population unable to afford private school fees. As a country we are missing out on our biggest talent pool, fishing in the same small pond for generation after generation.

On current evidence, the private school elites will continue to prosper in Britain for the foreseeable future. There is little appetite for tackling the educational inequalities they create. Eton meanwhile is predicted to maintain its special role as ‘the chief nurse of England’s statesmen’ for centuries to come.56 It is also likely to retain its unique place among the national treasures on display at the National Gallery. As in so many other areas, the privately educated make up much of the arts establishment: one last astonishing fact is that every director of the National Gallery since it was established in 1855 has been educated at an independent school.