Remove sod one square at a time, or roll up a strip. The strip may be heavy to move!

With your garden plan prepared, it’s time for the work-intensive stage of gardening in raised beds: building the beds themselves. If you’re creating beds with native soil, that means digging or tilling. If you’re building a framed bed, you’ll need to buy materials, gather tools, and assemble the frames. There are some shortcuts you can take to save time and labor, but it’s a good idea to set aside a full day or a weekend for a bed-building project.

Building raised beds with native soil is less costly than filling frames with purchased soil materials, but there’s no doubt it requires more physical labor. It’s important to clear the soil surface of weedy growth before you begin digging.

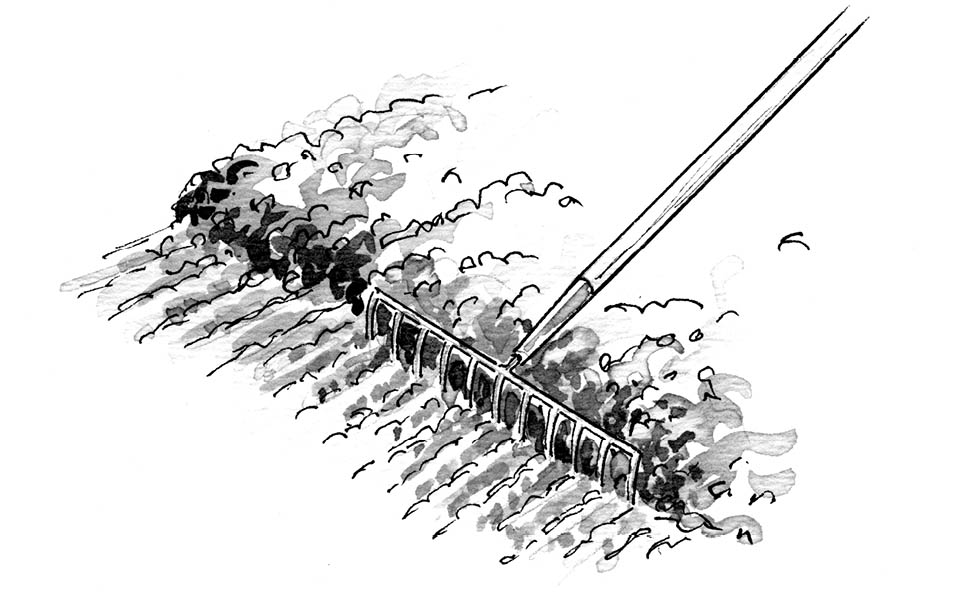

Before you dig, you may need to remove the surface vegetation, especially if the site is covered with lawn grass or weeds. Mark the outside perimeter of the overall garden, and then use a sharp spade to cut through the surface vegetation vertically to isolate a strip. When you’ve cut a strip the width of the garden, slide the blade of the spade horizontally underneath the sod at one end of the strip and slice through the roots. As you work, you can roll up the strip of sod or simply cut and lift squares, as shown on below.

Put the removed sod into a wheelbarrow and take it to your composting area; it will eventually break down into compost. (For more about making compost, see here.)

After you’ve removed surface vegetation and before you turn the soil, check soil moisture. If the soil is too dry or too wet, turning it will cause serious damage to the soil’s natural structure — damage that is difficult to repair. If the soil is too dry, water it or wait for rain. If it’s too wet, check it daily until it’s dried out a bit. Test soil moisture by squeezing a handful of soil in your fist. If the soil sticks together in a muddy ball, it’s too wet. If it feels dusty dry, it’s too dry. If it forms a ball that crumbles apart into smaller pieces, it’s just right.

Remove sod one square at a time, or roll up a strip. The strip may be heavy to move!

You can dig the bed by hand or turn the soil with a rotary tiller. There’s no denying that hand-digging a garden bed is heavy labor, but you can make it less arduous by breaking up the job over time. If, for example, a garden is 30 square feet, and you allow five days, then you have to dig only 6 square feet per day — that’s less than the surface area of a standard card table.

To dig an entire garden in a day, though, using a tiller may be the only realistic choice. If you don’t own a tiller, it’s easy to find one to rent. Ask at a local garden center or hardware store. You can also “rent” labor, perhaps from your kids or the neighbor’s teenage children, to dig a bed by hand, or you can probably find someone locally who owns a tiller and will do custom tilling for hire. Or throw a gardening potluck: you provide all the food, and your guests bring along their own shovel, digging fork, or rake. Take turns digging and eating!

However you decide to approach the task of turning the soil, be moderate. Turning the soil is a necessary step for creating a raised bed, but it’s not a soil-friendly process. Turning the soil disrupts the natural structure of the soil, ruining it (in the short term) as a habitat for the organisms, both macro and micro, that call the soil home. The more you pulverize the soil, the more soil life is destroyed. But once you’ve shaped the raised beds, there are steps you can take to encourage microbes and other beneficial organisms to recolonize the soil. And keep in mind that the digging/tilling process is a one-time evil. From here on, you should never again have to dramatically disrupt the soil in your raised beds.

It’s possible to get rid of sod or weed cover without physically cutting and removing it, but it takes time. If you can afford to wait two months before making your raised beds, you can smother the plant growth on your garden site by covering it with a heavy, dark, moisture-proof cover.

First, “scalp” the surface: use a mower or string trimmer to cut the grass or weeds as short as possible. Then cover the area with cardboard or newspapers, and top that with a sheet of heavy black plastic or a heavy-duty tarp. Weigh down the plastic or tarp securely with rocks, bricks, or scrap lumber.

Let the site sit undisturbed for at least a month, then remove the weights from one corner of the plot and lift the coverings. Is there any green plant growth underneath? If so, let the site rest 2 weeks longer and check again. Once all the surface vegetation is dead, you can open up the site and rake it clear (compost the material you rake off). Check soil moisture! If the site is too dry to turn (see Assessing Soil Moisturhere), water it well and then wait a couple of days for it to reach the right moisture level before you dig or till.

This type of treatment is very effective for killing tough weeds, but it’s also hard on the beneficial organisms that live in soil. To help the soil rebound, be sure to add a biological activator or some rich mature compost to the bed before you plant.

After you’ve worked the soil by tilling or digging, the next step is to shape the beds. First, gather the tools and equipment you’ll need: your garden plan, a tape measure, stakes and string, a hammer, a garden rake, a shovel, a digging fork, and soil amendments. It’s good to have a helper to assist with marking out the beds.

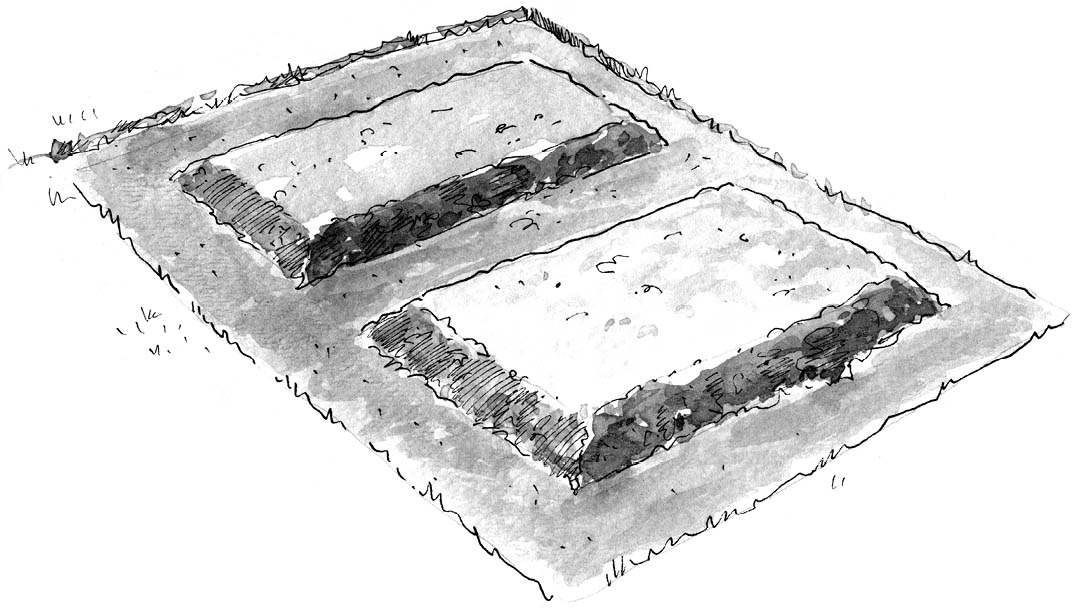

These simple raised beds took some time and energy to create, but they will never need digging again. Each season, simply “fluff” the soil lightly and plant!

Building a raised bed from ground level up can be a relatively simple or fairly complex project, depending on the size and height of the bed. The minimum height for a framed bed is about 6 inches, because vegetable crops need to extend their roots about that deep in order to grow well and produce a good yield. Deeper is even better. Providing only 6 inches of soil compared to 12 inches is like giving your plants a mediocre diet of prepared foods rather than fresh home-cooked meals: it’s harder to make optimum growth when the food supply isn’t as plentiful or nutritious. That said, a 6-inch-deep raised bed filled with good-quality compost will give satisfactory results for most vegetable crops.

The frame should be made from a solid material such as wood, cinder blocks, or pavers. You can build your own frame from scratch or buy a prefabricated kit.

The best part about building up a raised bed is that there’s no digging involved! That doesn’t mean no heavy lifting, though, because you will have to fill the frame with soil or compost. As with the digging-down method, it’s your choice whether to undertake the hauling and hefting yourself or hire help.

Use your ingenuity in choosing materials to frame raised beds. Wood is a common choice because it’s so easily available, but you can also use stones, cinder blocks, or straw bales.

Plain old wooden boards work fine for framing raised beds. You can buy 2 × 6 pine boards from any home center or lumber yard, or seek out more rot-resistant wood such as cedar, white oak, black locust, or redwood. Keep in mind that the rot-resistant woods will be more expensive than pine.

Scrounged scrap lumber can serve the purpose, but only if you are certain that it is not treated wood. Treated wood is not suitable for raised-bed frames because the chemicals used to impregnate the wood can leach out into the soil. Other types of found wood may work, too, such as old dresser drawers, but be sure they are solid wood, not plywood or particle board (these are also impregnated with chemicals), and avoid painted wood.

Is rot-resistant wood worth the extra cost? That depends in part on your climate. Wood breaks down more quickly when it’s wet than when it’s dry, so rot-resistant wood is more important in regions that receive lots of rain. Composite (plastic) lumber is another long-lasting choice, but it’s not as sturdy as real wood and may need more bracing to prevent the frame from being pushed out of shape by the weight of the soil inside it.

Rough-cut logs can serve as a very attractive informal frame for raised beds. If you have a source for rough-cut logs, keep the bed size fairly small, 4 feet × 6 feet, for example, because longer logs will be very heavy to move. The logs will slowly decay, but they should last several years. A smooth log can be a nice place for you to sit while tending your garden.

A dry-laid stone wall can serve as the frame for a raised bed. If you plan to build a wall more than 1 foot tall, though, it will require mortar, or the weight of the soil could push the wall apart.

A stone frame around a low bed can be informal, too. In this case, you’d lay out smooth rocks roughly at the perimeter of the bed, fill up the bed, then push the rocks more firmly into place. The shape of the bed will shift and change a bit over time, but that’s not a problem with a free-form bed — perhaps a roughly circular or oval bed. You may want to make a free-form bed wider than your reach. If you do this, you will have to step into the bed to reach some of the plants, so use large flat stones to make a pathway across the bed.

Cinder blocks are an inexpensive and nearly indestructible framing material, but their appearance is utilitarian and their surfaces can be rough on your hands as you tend the garden. Plus a single block weighs more than 40 pounds, so a cinder block bed is a building project that demands a lot of strength (or some good hired help).

Bricks or pavers can be a good choice. If you can find a source of used material, it will be low-cost or even free. If you choose bricks or pavers, you’ll need to dig out a base layer and line it with crushed gravel to create a sturdy, level base that won’t shift out of position. And for beds taller than 6 inches, you’ll need to use mortar to hold a brick wall together.

Choose a frame material that suits your taste: clean-cut boards (top), rustic logs (middle), or durable cinder blocks (bottom) can all serve well to enclose raised beds.

Raised-bed kits range from small, simple plastic frames that can be snapped together without using tools to multidimensional cedar frames with built-in fencing to keep out animal pests. Pricing reflects the range of sizes, materials, and craftsmanship. You can buy a kit for a 4-foot × 8-foot frame for under $100 or invest up to $2,000 in a megakit. The cost for cedar frame kits ranges from $100 to $400, depending on bed height and length and the width of the framing lumber itself. You can shop for kits online or at garden centers and home centers.

It’s worthwhile to investigate kits. You may decide that a kit is just the right time- and labor-saving approach for you, or you may be inspired by the simplicity of a kit design and decide you could easily build a bed just like it yourself!

A construction-free method for framing a bed is to use straw bales, which you can buy from a local farm or garden center. Simply set the bales in place at your garden site to make a rectangular frame, and then fill the opening with soil and organic materials. The bales make a comfortable spot to sit while you tend your beds (you may want to place a cushion to sit on, though, in case the straw is wet or stretchy). The bales will probably last two years, or longer in dry climates. As the bales decay, put a new set of bales around the bed and push them into place. The old straw is all organic matter that will help the soil life in the bed thrive.

Once you’ve decided on your frame materials and design and are ready to set up your garden, mark the outlines of your beds with stakes and string and cut back the vegetation in the bed areas as close to ground level as possible. Don’t cut the pathway areas, though, if you plan to leave them as sod paths. If you plan to cover your paths with wood chips or some other material, do cut the vegetation short.

Next, assemble your frame, which may take you one hour or several, depending on whether you’re using a kit, a simple straw bale design, or wooden frames built from scratch. (See How to Build a Wood-Framed Raised Bed.) Whatever type of frame you’re creating, it’s a good idea to check the level of the assembled frame. Your frame doesn’t need to be perfectly level, but if it’s too far out of balance, it won’t hold up as well as a level frame in the long run. You can scrape away soil if one corner of the frame is high, or tuck some crushed gravel under a low spot.

If your frame is only 6 inches tall, cover the ground surface inside the frame with cardboard (remove packaging tape from the cardboard first) or newspaper. Layer the newspaper several sheets thick. This will prevent grass and weeds from growing up through the soil in the frame. (Soil deeper than 6 inches should suppress nearly all plant growth.)

What’s the best filling for a framed raised bed? There are plenty of recipes to try.

One very good choice for filling is compost. It’s rich in nutrients, usually has a balanced pH, and is appealing to soil-dwelling organisms. The trick is to find a reliable source of high-quality compost. If you’re lucky enough to find a local supplier, put in your order as early as possible because they often sell out, especially during peak demand times such as late spring.

If you want to extend the compost, you can mix roughly equal quantities of compost, peat moss, and vermiculite. This is a classic recipe for filling raised beds, but keep in mind that many gardeners avoid peat moss because it’s not a local, sustainably produced material. Also, this mix is not as nutrient-rich as compost alone, and you’ll probably need to apply fertilizers during the growing season to keep plants thriving in a mix like this.

Beds filled with straight compost may noticeably shrink over time. Some of this is due to settling, but more of it is due to the soil life “digesting” the organic matter and using it to feed the plants. This is a good thing! But you will need a steady supply of compost to replenish the bed every year.

If you have a source of native soil that’s suitable for gardening (perhaps you have good soil in parts of your yard that are too shady for gardening), you can dig it up and transport it by wheelbarrow to fill your beds. Or you can purchase topsoil in bulk from a landscaping supplier or sometimes a garden center. You can make a blend of 3 parts soil, 3 parts coarse sand, and 4 parts composted shredded leaves. Don’t worry if you don’t have these precise materials in these particular ratios. There’s no single “right formula” for a raised-bed mix.

Beds filled with topsoil and amended with compost won’t shrink as quickly as those filled with straight compost, but they will need a compost infusion each year to maintain fertility.

Bagged compost or topsoil is available at most garden centers and home centers, but it may be cheaper or more convenient to arrange for a bulk delivery. Check for local suppliers and make sure you see a sample of the product before you place your order. Mature compost should be uniform rich brown to black, with no large chunks of undecomposed material. Be wary of topsoil that is too stony, or that contains visible pieces of perennial roots. Deliveries are usually quantified in cubic yards. One cubic yard is equal to 27 cubic feet. A 4-foot × 8-foot bed that is 10 inches deep would hold about 27 cubic feet, and a 4-foot × 12-foot bed would hold about 40 cubic feet.

Plan ahead for a bulk delivery. If the driver cannot maneuver the large, heavy dump truck right to your beds, scout out a level spot that the truck can reach, preferably at the same level or uphill from your beds, and as close to them as feasible. If you can’t move the material immediately after the delivery, cover it with a tarp to prevent the soil or compost from becoming waterlogged by rain, which would make it much heavier and harder to work with.

It may be easiest to blend materials together right in the bed. Use your wheelbarrow (or a 5-gallon bucket or 10-gallon trash can) as your “measuring cup.” Dump the ingredients into the bed, and then use a garden fork or small handheld tiller to mix them together.

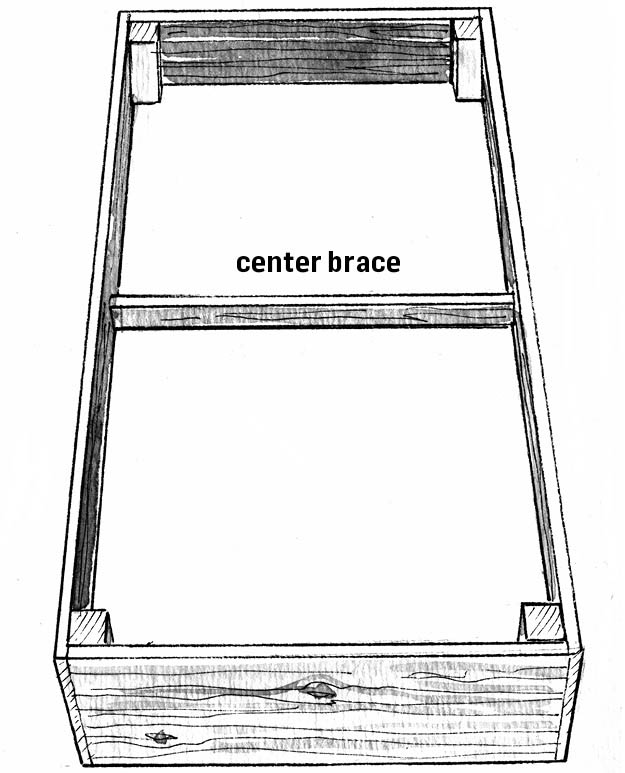

Designs abound for wood-framed raised beds, and frames made from 2 × 6, 2 × 8, or 2 × 12 boards or 4 × 4 timbers are very popular. The basic setup for a frame is the same for all of these materials, although the method for fastening the pieces together is different. Galvanized wood screws or nails are strong enough to hold together a frame made of 2 × 6s or 2 × 12s, but 6-inch-long galvanized spikes or timber screws are needed to connect 4 × 4s. The following materials and instructions are for a bed that is approximately 4 feet wide and 6 feet long with sides made from 2 × 6s. The sequence for assembling a frame of a different size made with different framing materials would be similar.

For taller frames that use a second set of boards or timbers, stagger the end joints. This makes for sturdier joints that are less likely to shift out of place over time. Fasten the two tiers together by driving spikes or screws down through the second course into the timbers below (you may need to drill pilot holes first).

On a gently sloping site, a three-sided frame may fit better than a four-sided frame. In this case, you’ll be working with the existing soil, and you’ll first loosen the soil and roughly shape the beds and paths. Here’s how to set up a three-sided frame to support the beds and prevent them from slumping down the slope. Note: Steeper slopes require more sophisticated designs and support to prevent the beds from collapsing.

These instructions are for 8-foot-long frames, but the instructions would be similar for frames of other lengths.

Soil amendments are food for the soil: materials that boost soil organic matter and thus encourage healthy populations of soil microorganisms. It’s important to add soil amendments when you first shape your beds because they will help initiate the healing process your soil needs after the disturbance from digging or tilling.

Compost, a diverse mix of decomposed organic materials, is the best soil amendment around. You may have a home-garden compost pile, but even if you don’t, you can easily find local sources of compost. Ask your gardening friends and check Craigslist. All garden centers and home centers sell bagged compost, and you may discover a local farm or business that makes compost and offers bulk delivery.

Many municipalities offer compost to residents for free. Such compost is usually made from leaves, grass clippings, and other materials collected from around town and composted in bulk at the town’s recycling site. This compost can be excellent in quality, or not so good. It can even be hazardous to your plants, because it may contain the residues of herbicides that have long-lasting effects. Such herbicides can cause stunting or deformed growth.

If you suspect that the compost you’re using could be contaminated, test it before adding it to your raised beds. Set up an experiment with four small pots. Put potting soil in a couple of pots, and potting soil mixed with the compost in the other two. Sow three seeds of peas or beans in each pot and water them well. Put the pots in a warm, well-lit spot. Keep them watered as they germinate. Compare the appearance of the seedlings as they grow. If the leaves show distortions such as cupping (turning up of the leaf margins), wrinkling, or thickening, that’s a sign of herbicide damage.

Soil pH is a measure of the level of acidity or alkalinity in the soil environment. It’s expressed as a number, such as 7.0, which is the pH of a neutral soil. A pH lower than 7.0 tends toward acid, and a pH value higher than 7.0 tends toward alkaline. Most vegetable crops grow best in a pH range of 6.0 to 7.0. But in some regions of the country, soils are naturally acid, and in other areas they are naturally alkaline. If your soil falls outside the range of 6.0 to 7.0, you can change its pH by adding lime (to raise the pH) or sulfur (to lower the pH). However, the change doesn’t happen instantly. It will take about 2 months after lime or sulfur is added for the chemical reactions in the soil to run their course and make the shift happen.

You can check soil pH using a simple test kit available at garden centers, or you can take a soil sample and have the pH tested. Ask at your local garden center or Cooperative Extension Service office about how to prepare a soil sample and have it tested.

The amount of lime or sulfur to add to change your soil’s pH depends on the type of soil, but as a rough rule of thumb, 5 pounds of dolomitic lime per 100 square feet of garden bed mixed into the top 2 inches of soil will raise the pH by 1 point (for example, from 5.5 to 6.5). With iron sulfate, the rate is 1.5 pounds per 100 square feet to lower pH by 1 point.

Choices of soil amendments are plentiful, and specific amendments help supply different nutrients that plants need, including nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and calcium. For example, blood meal and fish meal are nitrogen sources. Bone meal and rock phosphate supply phosphorus. There’s a lot to learn about soil amendments, and it is possible to overapply them. It’s best not to add them unless you study up first, test your soil to see what nutrients are deficient, or get advice from a trusted source. For more information about soil amendments, see Resources. Don’t worry, though. It’s not essential to apply specific soil amendments. Generally, if you add compost each year, your soil will gradually improve over time. And you can monitor plant growth and use organic fertilizer during the growing season if your plants look peaked.

With your beds in place, you’ll be eager to start planting! Take time first, though, to finish preparing the pathways between the beds. When you start beds in a lawn area, it’s a simple choice to leave your pathways as is. Grass pathways are comfortable to walk and kneel on, and they look attractive as long as you’re willing to keep them trimmed. You may want to invest in a quality pair of grass shears for trimming the grass along the beds, in the spots you can’t reach with your mower. And if your beds aren’t framed, it’s wise to edge the beds with a spade or half-moon edger twice a season to prevent grass from invading the beds.

Your other choice is to cover the pathways. You can use some type of mulch (such as bark chips, wood chips, or straw), or you can use gravel or pavers. Each type of covering has pros and cons. Bark/wood chips and straw are softer for kneeling than gravel or pavers, but they need to be renewed at least once per growing season. Gravel or pavers give the garden a more finished and elegant appearance, and weeds and grass will be less likely to push through them. However, installing gravel or paved paths is more work than spreading bark/wood chips or straw. Choose the material based on price, style preference, and comfort.

Step and press down firmly with your foot on a half-moon edger to cut cleanly through soil and roots at the edges of a raised bed. Use a trowel or shovel to lift the cut pieces of grass and soil and add them to a compost pile.