Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill• Create a Generic Class

• Use the Diamond Syntax to Create a Collection

• Analyze the Interoperability of Collections that Use Raw and Generic Types

• Use Wrapper Classes and Autoboxing

• Create and Use a List, a Set, and a Deque

• Create and Use a Map

• Use java.util.Comparator and java.lang.Comparable

• Sort and Search Arrays and Lists

Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill

Q&A Self Test

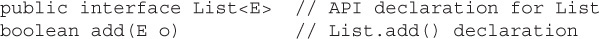

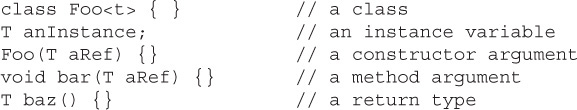

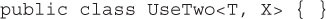

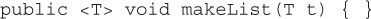

Generics were the most talked about feature of Java 5. Some people love ‘em, some people hate ‘em, but they’re here to stay. At their simplest, they can help make code easier to write and more robust. At their most complex, they can be very, very hard to create and maintain. Luckily, the exam creators stuck to the simple end of generics, covering the most common and useful features and leaving out most of the especially tricky bits.

4.X toString() will show up in numerous places throughout the exam.

4.7 Use java.util.Comparator and java.lang.Comparable.

4.8 Sort and search arrays and lists.

It might not be immediately obvious, but understanding hashCode() and equals() is essential to working with Java collections, especially when using Maps and when searching and sorting in general.

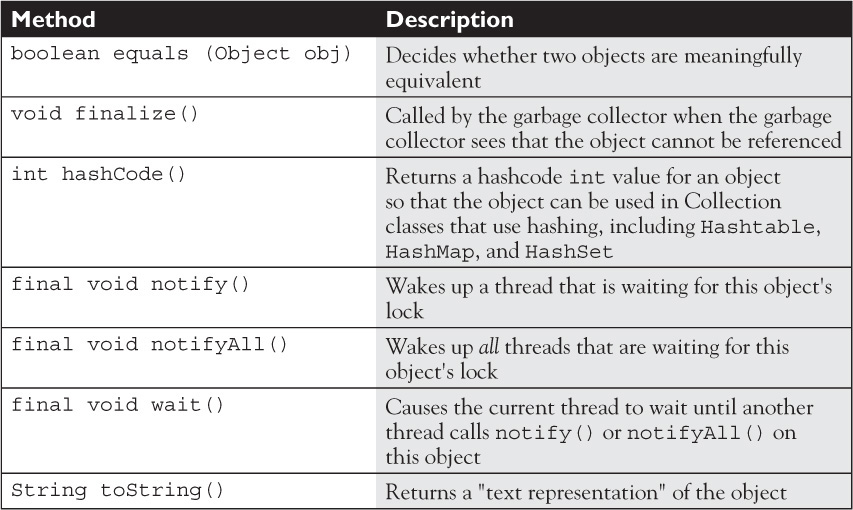

You’re an object. Get used to it. You have state, you have behavior, you have a job. (3Or at least your chances of getting one will go up after passing the exam.) If you exclude primitives, everything in Java is an object. Not just an object, but an Object with a capital O. Every exception, every event, every array extends from java.lang.Object. For the exam, you don’t need to know every method in class Object, but you will need to know about the methods listed in Table 11-1.

TABLE 11-1 Methods of Class Object Covered on the Exam

Chapter 13 covers wait(), notify(), and notifyAll(). The finalize() method was covered in Chapter 3. In this section, we’ll look at the hashCode() and equals() methods because they are so often critical when using collections. Oh, that leaves toString(), doesn’t it? Okay, we’ll cover that right now because it takes two seconds.

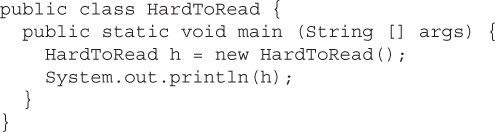

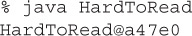

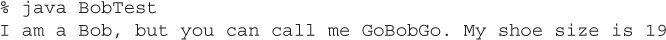

Override toString() when you want a mere mortal to be able to read something meaningful about the objects of your class. Code can call toString() on your object when it wants to read useful details about your object. When you pass an object reference to the System.out.println() method, for example, the object’s toString() method is called, and the return of toString() is shown in the following example:

Running the HardToRead class gives us the lovely and meaningful

The preceding output is what you get when you don’t override the toString() method of class Object. It gives you the class name (at least that’s meaningful) followed by the @ symbol, followed by the unsigned hexadecimal representation of the object’s hashcode.

Trying to read this output might motivate you to override the toString() method in your classes, for example:

This ought to be a bit more readable:

Some people affectionately refer to toString() as the “spill-your-guts method” because the most common implementations of toString() simply spit out the object’s state (in other words, the current values of the important instance variables). That’s it for toString(). Now we’ll tackle equals() and hashCode().

As we mentioned earlier, you might be wondering why we decided to talk about Object.equals() near the beginning of the chapter on collections. We’ll be spending a lot of time answering that question over the next pages, but for now, it’s enough to know that whenever you need to sort or search through a collection of objects, the equals() and hashCode() methods are essential. But before we go there, let’s look at the more common uses of the equals() method.

You learned a bit about the equals() method in Chapter 4. We discussed how comparing two object references using the == operator evaluates to true only when both references refer to the same object because == simply looks at the bits in the variable, and they’re either identical or they’re not. You saw that the String class has overridden the equals() method (inherited from the class Object), so you could compare two different String objects to see if their contents are meaningfully equivalent. Later in this chapter, we’ll be discussing the so-called wrapper classes when it’s time to put primitive values into collections. For now, remember that there is a wrapper class for every kind of primitive. The folks who created the Integer class (to support int primitives) decided that if two different Integer instances both hold the int value 5, as far as you’re concerned, they are equal. The fact that the value 5 lives in two separate objects doesn’t matter.

When you really need to know if two references are identical, use ==. But when you need to know if the objects themselves (not the references) are equal, use the equals() method. For each class you write, you must decide if it makes sense to consider two different instances equal. For some classes, you might decide that two objects can never be equal. For example, imagine a class Car that has instance variables for things like make, model, year, configuration—you certainly don’t want your car suddenly to be treated as the very same car as someone with a car that has identical attributes. Your car is your car and you don’t want your neighbor Billy driving off in it just because “hey, it’s really the same car; the equals() method said so.” So no two cars should ever be considered exactly equal. If two references refer to one car, then you know that both are talking about one car, not two cars that have the same attributes. So in the case of class Car you might not ever need, or want, to override the equals() method. Of course, you know that isn’t the end of the story.

There’s a potential limitation lurking here: If you don’t override a class’s equals() method, you won’t be able to use those objects as a key in a hashtable and you probably won’t get accurate Sets such that there are no conceptual duplicates.

The equals() method in class Object uses only the == operator for comparisons, so unless you override equals(), two objects are considered equal only if the two references refer to the same object.

Let’s look at what it means to not be able to use an object as a hashtable key. Imagine you have a car, a very specific car (say, John’s red Subaru Outback as opposed to Mary’s purple Mini) that you want to put in a HashMap (a type of hashtable we’ll look at later in this chapter) so that you can search on a particular car and retrieve the corresponding Person object that represents the owner. So you add the car instance as the key to the HashMap (along with a corresponding Person object as the value). But now what happens when you want to do a search? You want to say to the HashMap collection, “Here’s the car; now give me the Person object that goes with this car.” But now you’re in trouble unless you still have a reference to the exact object you used as the key when you added it to the Collection. In other words, you can’t make an identical Car object and use it for the search.

The bottom line is this: If you want objects of your class to be used as keys for a hashtable (or as elements in any data structure that uses equivalency for searching for—and/or retrieving—an object), then you must override equals() so that two different instances can be considered the same. So how would we fix the car? You might override the equals() method so that it compares the unique VIN (Vehicle Identification Number) as the basis of comparison. That way, you can use one instance when you add it to a Collection and essentially re-create an identical instance when you want to do a search based on that object as the key. Of course, overriding the equals() method for Car also allows the potential for more than one object representing a single unique car to exist, which might not be safe in your design. Fortunately, the String and wrapper classes work well as keys in hashtables—they override the equals() method. So rather than using the actual car instance as the key into the car/owner pair, you could simply use a String that represents the unique identifier for the car. That way, you’ll never have more than one instance representing a specific car, but you can still use the car—or rather, one of the car’s attributes—as the search key.

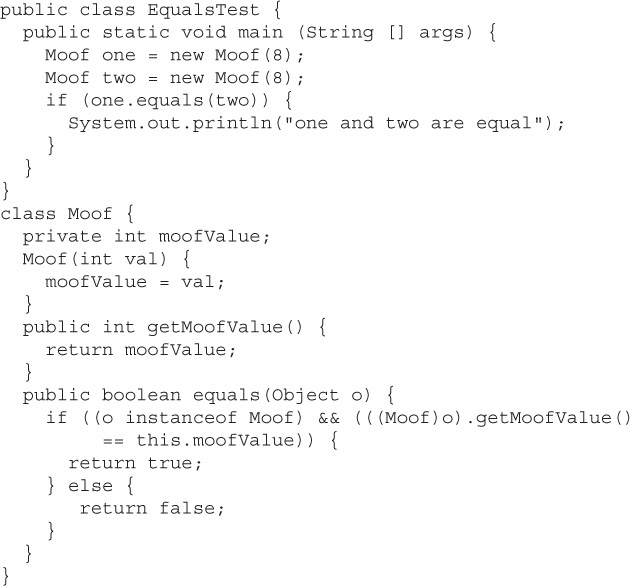

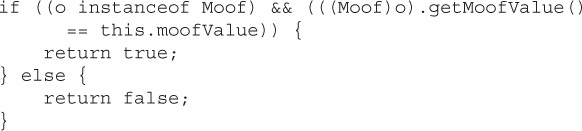

Let’s say you decide to override equals() in your class. It might look like this:

Let’s look at this code in detail. In the main() method of EqualsTest, we create two Moof instances, passing the same value 8 to the Moof constructor. Now look at the Moof class and let’s see what it does with that constructor argument—it assigns the value to the moofValue instance variable. Now imagine that you’ve decided two Moof objects are the same if their moofValue is identical. So you override the equals() method and compare the two moofValues. It is that simple. But let’s break down what’s happening in the equals() method:

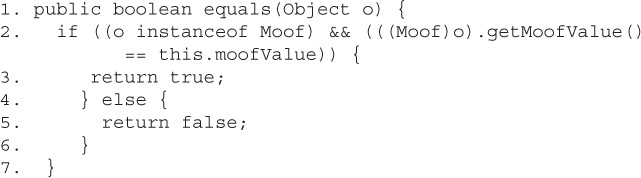

First of all, you must observe all the rules of overriding, and in line 1 we are indeed declaring a valid override of the equals() method we inherited from Object.

Line 2 is where all the action is. Logically, we have to do two things in order to make a valid equality comparison.

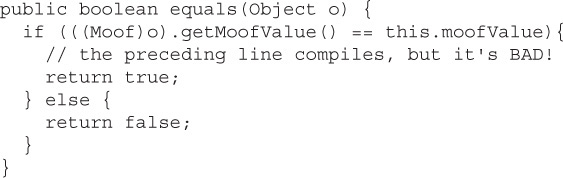

First, be sure that the object being tested is of the correct type! It comes in polymorphically as type Object, so you need to do an instanceof test on it. Having two objects of different class types be considered equal is usually not a good idea, but that’s a design issue we won’t go into here. Besides, you’d still have to do the instanceof test just to be sure that you could cast the object argument to the correct type so that you can access its methods or variables in order to actually do the comparison. Remember, if the object doesn’t pass the instanceof test, then you’ll get a runtime ClassCastException. For example:

The (Moof)o cast will fail if o doesn’t refer to something that IS-A Moof.

Second, compare the attributes we care about (in this case, just moofValue). Only the developer can decide what makes two instances equal. (For best performance, you’re going to want to check the fewest number of attributes.)

In case you were a little surprised by the whole ((Moof)o).getMoofValue() syntax, we’re simply casting the object reference, o, just-in-time as we try to call a method that’s in the Moof class but not in Object. Remember, without the cast, you can’t compile because the compiler would see the object referenced by o as simply, well, an Object. And since the Object class doesn’t have a getMoofValue() method, the compiler would squawk (technical term). But then, as we said earlier, even with the cast, the code fails at runtime if the object referenced by o isn’t something that’s castable to a Moof. So don’t ever forget to use the instanceof test first. Here’s another reason to appreciate the short-circuit && operator—if the instanceof test fails, we’ll never get to the code that does the cast, so we’re always safe at runtime with the following:

So that takes care of equals()…

Whoa… not so fast. If you look at the Object class in the Java API spec, you’ll find what we call a contract specified in the equals() method. A Java contract is a set of rules that should be followed, or rather must be followed, if you want to provide a “correct” implementation as others will expect it to be. Or to put it another way: If you don’t follow the contract, your code may still compile and run, but your code (or someone else’s) may break at runtime in some unexpected way.

Pulled straight from the Java docs, the equals() contract says

It is reflexive. For any reference value

It is reflexive. For any reference value x, x.equals(x) should return true.

It is symmetric. For any reference values

It is symmetric. For any reference values x and y, x.equals(y) should return true if and only if y.equals(x) returns true.

It is transitive. For any reference values

It is transitive. For any reference values x, y, and z, if x.equals(y) returns true and y.equals(z) returns true, then x.equals(z) must return true.

It is consistent. For any reference values

It is consistent. For any reference values x and y, multiple invocations of x.equals(y) consistently return true or consistently return false, provided no information used in equals() comparisons on the object is modified.

For any non-

For any non-null reference value x, x.equals(null) should return false.

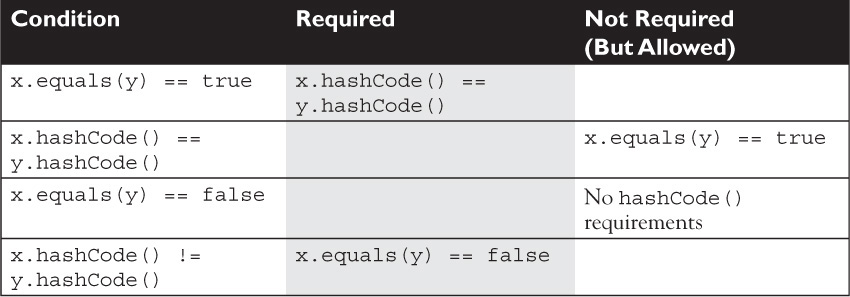

And you’re so not off the hook yet. We haven’t looked at the hashCode() method, but equals() and hashCode() are bound together by a joint contract that specifies if two objects are considered equal using the equals() method, then they must have identical hashcode values. So to be truly safe, your rule of thumb should be if you override equals(), override hashCode() as well. So let’s switch over to hashCode() and see how that method ties in to equals().

Hashcodes are typically used to increase the performance of large collections of data. The hashcode value of an object is used by some collection classes (we’ll look at the collections later in this chapter). Although you can think of it as kind of an object ID number, it isn’t necessarily unique. Collections such as HashMap and HashSet use the hashcode value of an object to determine how the object should be stored in the collection, and the hashcode is used again to help locate the object in the collection. For the exam, you do not need to understand the deep details of how the collection classes that use hashing are implemented, but you do need to know which collections use them (but, um, they all have “hash” in the name, so you should be good there). You must also be able to recognize an appropriate or correct implementation of hashCode(). This does not mean legal and does not even mean efficient. It’s perfectly legal to have a terribly inefficient hashcode method in your class, as long as it doesn’t violate the contract specified in the Object class documentation (we’ll look at that contract in a moment). So for the exam, if you’re asked to pick out an appropriate or correct use of hashcode, don’t mistake appropriate for legal or efficient.

In order to understand what’s appropriate and correct, we have to look at how some of the collections use hashcodes.

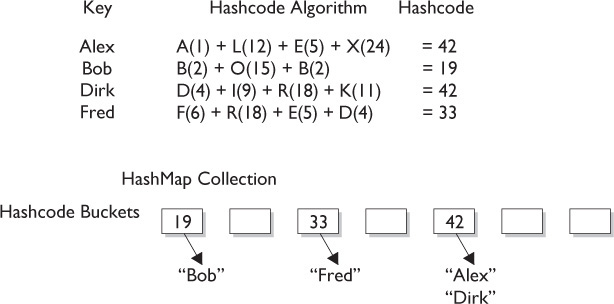

Imagine a set of buckets lined up on the floor. Someone hands you a piece of paper with a name on it. You take the name and calculate an integer code from it by using A is 1, B is 2, and so on, adding the numeric values of all the letters in the name together. A given name will always result in the same code; see Figure 11-1.

FIGURE 11-1 A simplified hashcode example

We don’t introduce anything random; we simply have an algorithm that will always run the same way given a specific input, so the output will always be identical for any two identical inputs. So far, so good? Now the way you use that code (and we’ll call it a hashcode now) is to determine which bucket to place the piece of paper into (imagine that each bucket represents a different code number you might get). Now imagine that someone comes up and shows you a name and says, “Please retrieve the piece of paper that matches this name.” So you look at the name they show you and run the same hashcode-generating algorithm. The hashcode tells you in which bucket you should look to find the name.

You might have noticed a little flaw in our system, though. Two different names might result in the same value. For example, the names Amy and May have the same letters, so the hashcode will be identical for both names. That’s acceptable, but it does mean that when someone asks you (the bucket clerk) for the Amy piece of paper, you’ll still have to search through the target bucket, reading each name until we find Amy rather than May. The hashcode tells you only which bucket to go into and not how to locate the name once we’re in that bucket.

So, for efficiency, your goal is to have the papers distributed as evenly as possible across all buckets. Ideally, you might have just one name per bucket so that when someone asked for a paper, you could simply calculate the hashcode and just grab the one paper from the correct bucket, without having to flip through different papers in that bucket until you locate the exact one you’re looking for. The least efficient (but still functional) hashcode generator would return the same hashcode (say, 42), regardless of the name, so that all the papers landed in the same bucket while the others stood empty. The bucket clerk would have to keep going to that one bucket and flipping painfully through each one of the names in the bucket until the right one was found. And if that’s how it works, they might as well not use the hashcodes at all, but just go to the one big bucket and start from one end and look through each paper until they find the one they want.

This distributed-across-the-buckets example is similar to the way hashcodes are used in collections. When you put an object in a collection that uses hashcodes, the collection uses the hashcode of the object to decide in which bucket/slot the object should land. Then when you want to fetch that object (or, for a hashtable, retrieve the associated value for that object), you have to give the collection a reference to an object, which it then compares to the objects it holds in the collection. As long as the object stored in the collection, like a paper in the bucket, you’re trying to search for has the same hashcode as the object you’re using for the search (the name you show to the person working the buckets), then the object will be found. But—and this is a Big One—imagine what would happen if, going back to our name example, you showed the bucket worker a name and they calculated the code based on only half the letters in the name instead of all of them. They’d never find the name in the bucket because they wouldn’t be looking in the correct bucket!

Now can you see why if two objects are considered equal, their hashcodes must also be equal? Otherwise, you’d never be able to find the object, since the default hashcode method in class Object virtually always comes up with a unique number for each object, even if the equals() method is overridden in such a way that two or more objects are considered equal. It doesn’t matter how equal the objects are if their hashcodes don’t reflect that. So one more time: If two objects are equal, their hashcodes must be equal as well.

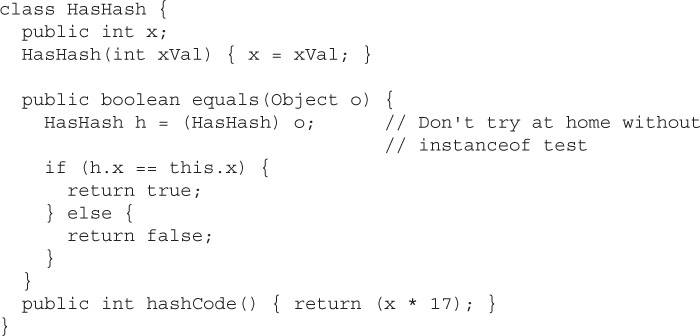

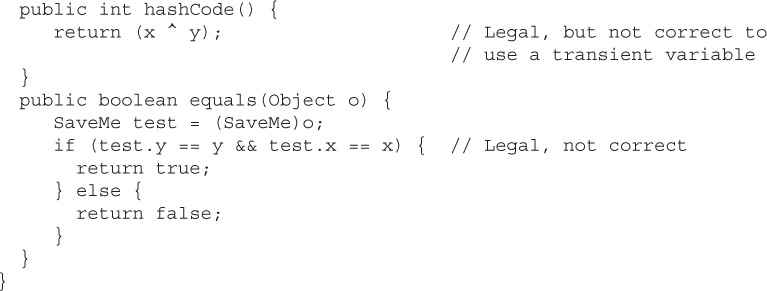

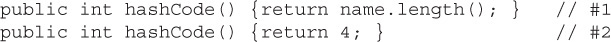

What the heck does a real hashcode algorithm look like? People get their PhDs on hashing algorithms, so from a computer science viewpoint, it’s beyond the scope of the exam. The part we care about here is the issue of whether you follow the contract. And to follow the contract, think about what you do in the equals() method. You compare attributes because that comparison almost always involves instance variable values (remember when we looked at two Moof objects and considered them equal if their int moofValues were the same?). Your hashCode() implementation should use the same instance variables. Here’s an example:

This equals() method says two objects are equal if they have the same x value, so objects with the same x value will have to return identical hashcodes.

Typically, you’ll see hashCode() methods that do some combination of ^-ing (XOR-ing) a class’s instance variables (in other words, twiddling their bits), along with perhaps multiplying them by a prime number. In any case, while the goal is to get a wide and random distribution of objects across buckets, the contract (and whether or not an object can be found) requires only that two equal objects have equal hashcodes. The exam does not expect you to rate the efficiency of a hashCode() method, but you must be able to recognize which ones will and will not work (“work” meaning “will cause the object to be found in the collection”).

Now that we know that two equal objects must have identical hashcodes, is the reverse true? Do two objects with identical hashcodes have to be considered equal? Think about it—you might have lots of objects land in the same bucket because their hashcodes are identical, but unless they also pass the equals() test, they won’t come up as a match in a search through the collection. This is exactly what you’d get with our very inefficient, everybody-gets-the-same-hashcode method. It’s legal and correct, just slooooow.

So in order for an object to be located, the search object and the object in the collection must both have identical hashcode values and return true for the equals() method. So there’s just no way out of overriding both methods to be absolutely certain that your objects can be used in Collections that use hashing.

Now coming to you straight from the fabulous Java API documentation for class Object, may we present (drumroll) the hashCode() contract:

Whenever it is invoked on the same object more than once during an execution of a Java application, the

Whenever it is invoked on the same object more than once during an execution of a Java application, the hashCode() method must consistently return the same integer, provided that no information used in equals() comparisons on the object is modified. This integer need not remain consistent from one execution of an application to another execution of the same application.

If two objects are equal according to the

If two objects are equal according to the equals(Object) method, then calling the hashCode() method on each of the two objects must produce the same integer result.

It is NOT required that if two objects are unequal according to the

It is NOT required that if two objects are unequal according to the equals(java.lang.Object) method, then calling the hashCode() method on each of the two objects must produce distinct integer results. However, the programmer should be aware that producing distinct integer results for unequal objects may improve the performance of hashtables.

And what this means to you is…

So let’s look at what else might cause a hashCode() method to fail. What happens if you include a transient variable in your hashCode() method? While that’s legal (the compiler won’t complain), under some circumstances, an object you put in a collection won’t be found. As you might know, serialization saves an object so that it can be reanimated later by deserializing it back to full objectness. But danger, Will Robinson—transient variables are not saved when an object is serialized. A bad scenario might look like this:

Here’s what could happen using code like the preceding example:

1. Give an object some state (assign values to its instance variables).

2. Put the object in a HashMap, using the object as a key.

3. Save the object to a file using serialization without altering any of its state.

4. Retrieve the object from the file through deserialization.

5. Use the deserialized (brought back to life on the heap) object to get the object out of the HashMap.

Oops. The object in the collection and the supposedly same object brought back to life are no longer identical. The object’s transient variable will come back with a default value rather than the value the variable had at the time it was saved (or put into the HashMap). So using the preceding SaveMe code, if the value of x is 9 when the instance is put in the HashMap, then since x is used in the calculation of the hashcode, when the value of x changes, the hashcode changes too. And when that same instance of SaveMe is brought back from deserialization, x == 0, regardless of the value of x at the time the object was serialized. So the new hashcode calculation will give a different hashcode and the equals() method fails as well since x is used to determine object equality.

Bottom line: transient variables can really mess with your equals() and hashCode() implementations. Keep variables non-transient or, if they must be marked transient, don’t use them to determine hashcodes or equality.

4.5 Create and use a List, a Set, and a Deque.

4.6 Create and use a Map.

In this section, we’re going to present a relatively high-level discussion of the major categories of collections covered on the exam. We’ll be looking at their characteristics and uses from an abstract level. In the section after this one, we’ll dive into each category of collection and show concrete examples of using each.

Can you imagine trying to write object-oriented applications without using data structures like hashtables or linked lists? What would you do when you needed to maintain a sorted list of, say, all the members in your Simpsons fan club? Obviously, you can do it yourself; Amazon.com must have thousands of algorithm books you can buy. But with the kind of schedules programmers are under today, it’s almost too painful to consider.

The Collections Framework in Java, which took shape with the release of JDK 1.2 and was expanded in 1.4 and again in Java 5, and yet again in Java 6 and Java 7, gives you lists, sets, maps, and queues to satisfy most of your coding needs. They’ve been tried, tested, and tweaked. Pick the best one for your job, and you’ll get reasonable performance. And when you need something a little more custom, the Collections Framework in the java.util package is loaded with interfaces and utilities.

There are a few basic operations you’ll normally use with collections:

Add objects to the collection.

Add objects to the collection.

Remove objects from the collection.

Remove objects from the collection.

Find out if an object (or group of objects) is in the collection.

Find out if an object (or group of objects) is in the collection.

Retrieve an object from the collection without removing it.

Retrieve an object from the collection without removing it.

Iterate through the collection, looking at each element (object) one after another.

Iterate through the collection, looking at each element (object) one after another.

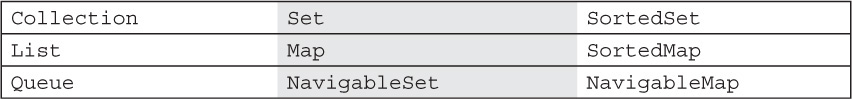

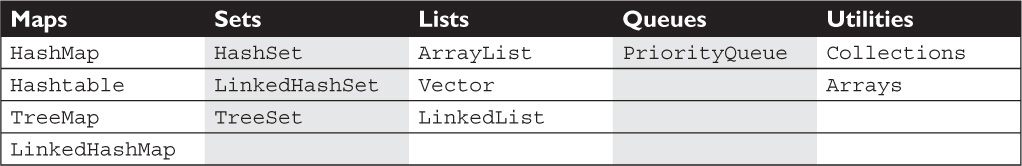

The Collections API begins with a group of interfaces, but also gives you a truckload of concrete classes. The core interfaces you need to know for the exam (and life in general) are the following nine:

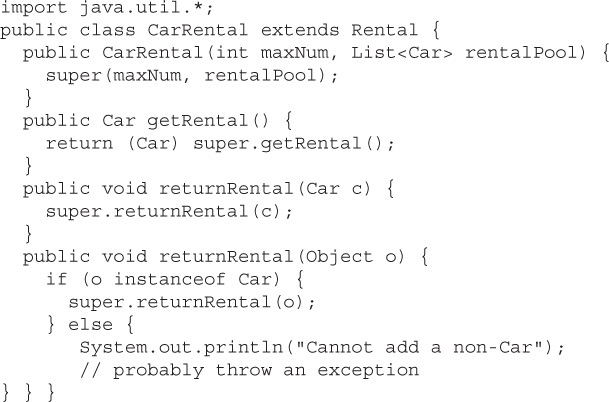

In Chapter 14, which deals with concurrency, we will discuss several classes related to the Deque interface. Other than those, the concrete implementation classes you need to know for the exam are the following 13 (there are others, but the exam doesn’t specifically cover them).

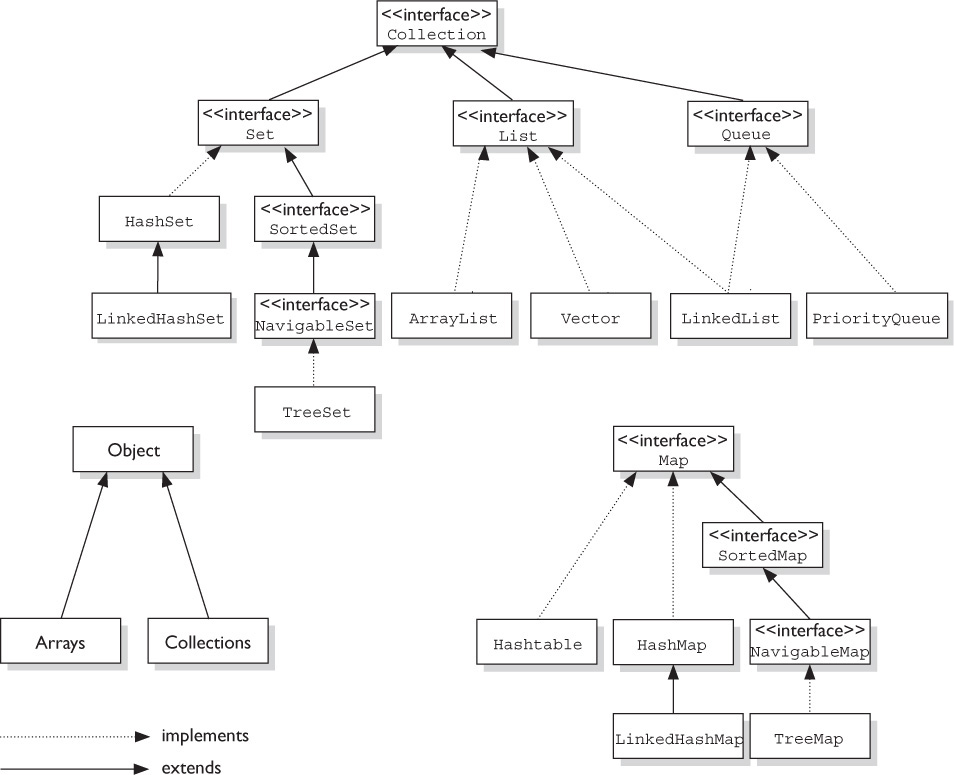

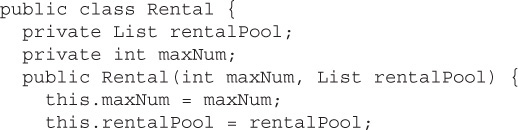

Not all collections in the Collections Framework actually implement the Collection interface. In other words, not all collections pass the IS-A test for Collection. Specifically, none of the Map-related classes and interfaces extend from Collection. So while SortedMap, Hashtable, HashMap, TreeMap, and LinkedHashMap are all thought of as collections, none are actually extended from Collection-with-a-capital-C (see Figure 11-2). To make things a little more confusing, there are really three overloaded uses of the word “collection”:

FIGURE 11-2 The interface and class hierarchy for collections

collection (lowercase c), which represents any of the data structures in which objects are stored and iterated over.

collection (lowercase c), which represents any of the data structures in which objects are stored and iterated over.

Collection (capital C), which is actually the

Collection (capital C), which is actually the java.util.Collection interface from which Set, List, and Queue extend. (That’s right, extend, not implement. There are no direct implementations of Collection.)

Collections (capital C and ends with s) is the

Collections (capital C and ends with s) is the java.util.Collections class that holds a pile of static utility methods for use with collections.

Collections come in four basic flavors:

Lists Lists of things (classes that implement

Lists Lists of things (classes that implement List)

Sets Unique things (classes that implement

Sets Unique things (classes that implement Set)

Maps Things with a unique ID (classes that implement

Maps Things with a unique ID (classes that implement Map)

Queues Things arranged by the order in which they are to be processed

Queues Things arranged by the order in which they are to be processed

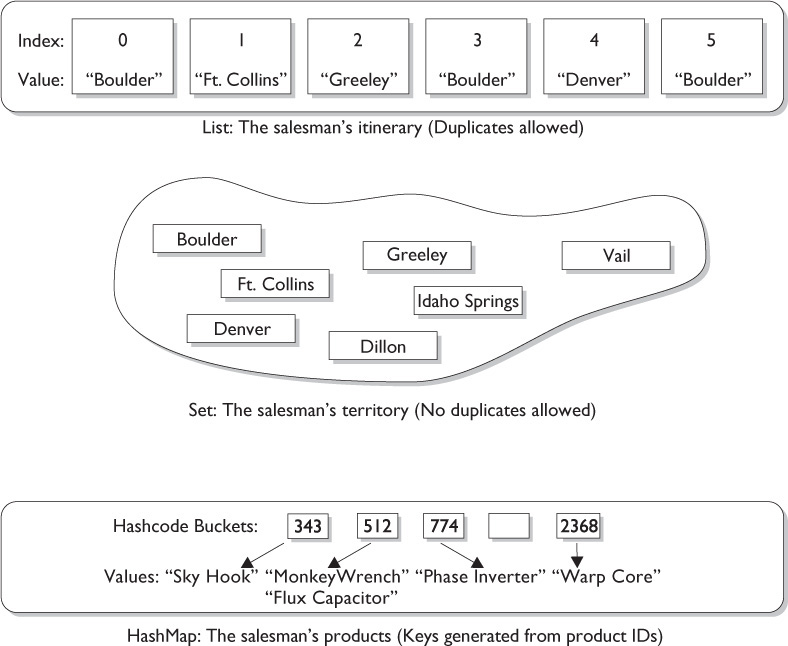

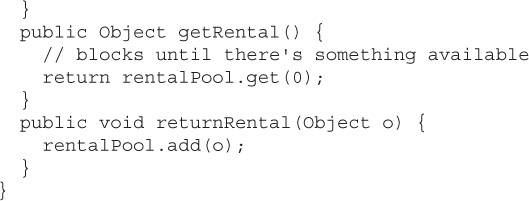

Figure 11-3 illustrates the relative structures of a List, a Set, and a Map.

FIGURE 11-3 Examples of a List, a Set, and a Map

But there are subflavors within those four flavors of collections:

An implementation class can be unsorted and unordered, ordered but unsorted, or both ordered and sorted. But an implementation can never be sorted but unordered, because sorting is a specific type of ordering, as you’ll see in a moment. For example, a HashSet is an unordered, unsorted set, while a LinkedHashSet is an ordered (but not sorted) set that maintains the order in which objects were inserted.

Maybe we should be explicit about the difference between sorted and ordered, but first we have to discuss the idea of iteration. When you think of iteration, you may think of iterating over an array using, say, a for loop to access each element in the array in order ([0], [1], [2], and so on). Iterating through a collection usually means walking through the elements one after another, starting from the first element. Sometimes, though, even the concept of first is a little strange—in a Hashtable, there really isn’t a notion of first, second, third, and so on. In a Hashtable, the elements are placed in a (seemingly) chaotic order based on the hashcode of the key. But something has to go first when you iterate; thus, when you iterate over a Hashtable, there will indeed be an order. But as far as you can tell, it’s completely arbitrary and can change in apparently random ways as the collection changes.

Ordered When a collection is ordered, it means you can iterate through the collection in a specific (not random) order. A Hashtable collection is not ordered. Although the Hashtable itself has internal logic to determine the order (based on hashcodes and the implementation of the collection itself), you won’t find any order when you iterate through the Hashtable. An ArrayList, however, keeps the order established by the elements’ index position (just like an array). LinkedHashSet keeps the order established by insertion, so the last element inserted is the last element in the LinkedHashSet (as opposed to an ArrayList, where you can insert an element at a specific index position). Finally, there are some collections that keep an order referred to as the natural order of the elements, and those collections are then not just ordered, but also sorted. Let’s look at how natural order works for sorted collections.

Sorted A sorted collection means that the order in the collection is determined according to some rule or rules, known as the sort order. A sort order has nothing to do with when an object was added to the collection or when was the last time it was accessed, or what “position” it was added at. Sorting is done based on properties of the objects themselves. You put objects into the collection, and the collection will figure out what order to put them in, based on the sort order. A collection that keeps an order (such as any List, which uses insertion order) is not really considered sorted unless it sorts using some kind of sort order. Most commonly, the sort order used is something called the natural order. What does that mean?

You know how to sort alphabetically—A comes before B, F comes before G, and so on. For a collection of String objects, then, the natural order is alphabetical. For Integer objects, the natural order is by numeric value—1 before 2, and so on. And for Foo objects, the natural order is… um… we don’t know. There is no natural order for Foo unless or until the Foo developer provides one through an interface (Comparable) that defines how instances of a class can be compared to one another (does instance a come before b, or does instance b come before a?). If the developer decides that Foo objects should be compared using the value of some instance variable (let’s say there’s one called bar), then a sorted collection will order the Foo objects according to the rules in the Foo class for how to use the bar instance variable to determine the order. Of course, the Foo class might also inherit a natural order from a superclass rather than define its own order in some cases.

Aside from natural order as specified by the Comparable interface, it’s also possible to define other, different sort orders using another interface: Comparator. We will discuss how to use both Comparable and Comparator to define sort orders later in this chapter. But for now, just keep in mind that sort order (including natural order) is not the same as ordering by insertion, access, or index.

Now that we know about ordering and sorting, we’ll look at each of the four interfaces, and we’ll dive into the concrete implementations of those interfaces.

A List cares about the index. The one thing that List has that non-lists don’t is a set of methods related to the index. Those key methods include things like get(int index), indexOf(Object o), add(int index, Object obj), and so on. All three List implementations are ordered by index position—a position that you determine either by setting an object at a specific index or by adding it without specifying position, in which case the object is added to the end. The three List implementations are described in the following sections.

ArrayList Think of this as a growable array. It gives you fast iteration and fast random access. To state the obvious: It is an ordered collection (by index), but not sorted. You might want to know that as of version 1.4, ArrayList now implements the new RandomAccess interface—a marker interface (meaning it has no methods) that says, “This list supports fast (generally constant time) random access.” Choose this over a LinkedList when you need fast iteration but aren’t as likely to be doing a lot of insertion and deletion.

Vector Vector is a holdover from the earliest days of Java; Vector and Hashtable were the two original collections—the rest were added with Java 2 versions 1.2 and 1.4. A Vector is basically the same as an ArrayList, but Vector methods are synchronized for thread safety. You’ll normally want to use ArrayList instead of Vector because the synchronized methods add a performance hit you might not need. And if you do need thread safety, there are utility methods in class Collections that can help. Vector is the only class other than ArrayList to implement RandomAccess.

LinkedList A LinkedList is ordered by index position, like ArrayList, except that the elements are doubly linked to one another. This linkage gives you new methods (beyond what you get from the List interface) for adding and removing from the beginning or end, which makes it an easy choice for implementing a stack or queue. Keep in mind that a LinkedList may iterate more slowly than an ArrayList, but it’s a good choice when you need fast insertion and deletion. As of Java 5, the LinkedList class has been enhanced to implement the java.util.Queue interface. As such, it now supports the common queue methods peek(), poll(), and offer().

A Set cares about uniqueness—it doesn’t allow duplicates. Your good friend the equals() method determines whether two objects are identical (in which case, only one can be in the set). The three Set implementations are described in the following sections.

HashSet A HashSet is an unsorted, unordered Set. It uses the hashcode of the object being inserted, so the more efficient your hashCode() implementation, the better access performance you’ll get. Use this class when you want a collection with no duplicates and you don’t care about order when you iterate through it.

LinkedHashSet A LinkedHashSet is an ordered version of HashSet that maintains a doubly linked List across all elements. Use this class instead of HashSet when you care about the iteration order. When you iterate through a HashSet, the order is unpredictable, while a LinkedHashSet lets you iterate through the elements in the order in which they were inserted.

TreeSet The TreeSet is one of two sorted collections (the other being TreeMap). It uses a Red-Black tree structure (but you knew that), and guarantees that the elements will be in ascending order, according to natural order. Optionally, you can construct a TreeSet with a constructor that lets you give the collection your own rules for what the order should be (rather than relying on the ordering defined by the elements’ class) by using a Comparator. As of Java 6, TreeSet implements NavigableSet.

A Map cares about unique identifiers. You map a unique key (the ID) to a specific value, where both the key and the value are, of course, objects. You’re probably quite familiar with Maps since many languages support data structures that use a key/value or name/value pair. The Map implementations let you do things like search for a value based on the key, ask for a collection of just the values, or ask for a collection of just the keys. Like Sets, Maps rely on the equals() method to determine whether two keys are the same or different.

HashMap The HashMap gives you an unsorted, unordered Map. When you need a Map and you don’t care about the order when you iterate through it, then HashMap is the way to go; the other maps add a little more overhead. Where the keys land in the Map is based on the key’s hashcode, so, like HashSet, the more efficient your hashCode() implementation, the better access performance you’ll get. HashMap allows one null key and multiple null values in a collection.

Hashtable Like Vector, Hashtable has existed from prehistoric Java times. For fun, don’t forget to note the naming inconsistency: HashMap vs. Hashtable. Where’s the capitalization of t? Oh well, you won’t be expected to spell it. Anyway, just as Vector is a synchronized counterpart to the sleeker, more modern ArrayList, Hashtable is the synchronized counterpart to HashMap. Remember that you don’t synchronize a class, so when we say that Vector and Hashtable are synchronized, we just mean that the key methods of the class are synchronized. Another difference, though, is that while HashMap lets you have null values as well as one null key, a Hashtable doesn’t let you have anything that’s null.

LinkedHashMap Like its Set counterpart, LinkedHashSet, the LinkedHashMap collection maintains insertion order (or, optionally, access order). Although it will be somewhat slower than HashMap for adding and removing elements, you can expect faster iteration with a LinkedHashMap.

TreeMap You can probably guess by now that a TreeMap is a sorted Map. And you already know that, by default, this means “sorted by the natural order of the elements.” Like TreeSet, TreeMap lets you define a custom sort order (via a Comparator) when you construct a TreeMap that specifies how the elements should be compared to one another when they’re being ordered. As of Java 6, TreeMap implements NavigableMap.

A Queue is designed to hold a list of “to-dos,” or things to be processed in some way. Although other orders are possible, queues are typically thought of as FIFO (first-in, first-out). Queues support all of the standard Collection methods and they also have methods to add and subtract elements and review queue elements.

PriorityQueue This class is new as of Java 5. Since the LinkedList class has been enhanced to implement the Queue interface, basic queues can be handled with a LinkedList. The purpose of a PriorityQueue is to create a “priority-in, priority out” queue as opposed to a typical FIFO queue. A PriorityQueue’s elements are ordered either by natural ordering (in which case the elements that are sorted first will be accessed first) or according to a Comparator. In either case, the elements’ ordering represents their relative priority.

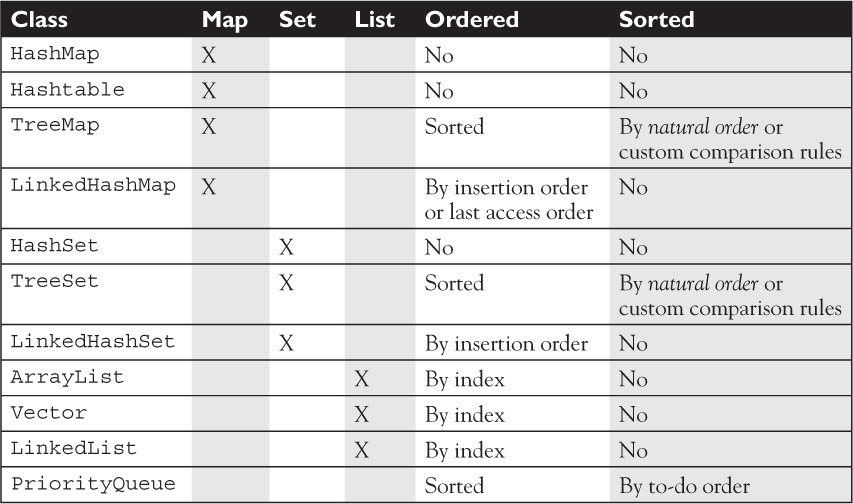

Table 11-2 summarizes 11 of the 13 concrete collection-oriented classes you’ll need to understand for the exam. (Arrays and Collections are coming right up!)

TABLE 11-2 Collection Interface Concrete Implementation Classes

4.3 Use the diamond syntax to create a collection.

4.4 Use wrapper classes and autoboxing.

4.5 Create and use a List, a Set, and a Deque.

4.6 Create and use a Map.

4.7 Use java.util.Comparator and java.lang.Comparable.

4.8 Sort and search arrays and lists.

We’ve taken a high-level theoretical look at the key interfaces and classes in the Collections Framework; now let’s see how they work in practice.

Let’s start with a quick review of what we learned about ArrayLists from Chapter 5. The java.util.ArrayList class is one of the most commonly used classes in the Collections Framework. It’s like an array on vitamins. Some of the advantages ArrayList has over arrays are

It can grow dynamically.

It can grow dynamically.

It provides more powerful insertion and search mechanisms than arrays.

It provides more powerful insertion and search mechanisms than arrays.

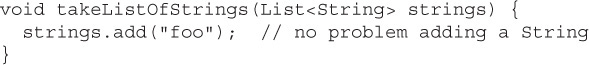

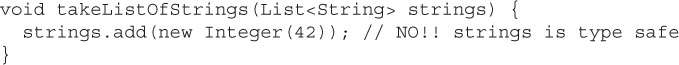

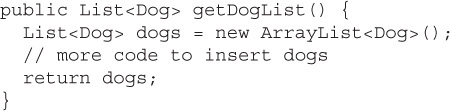

Let’s take a look at using an ArrayList that contains strings. A key design goal of the Collections Framework was to provide rich functionality at the level of the main interfaces: List, Set, and Map. In practice, you’ll typically want to instantiate an ArrayList polymorphically, like this:

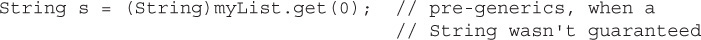

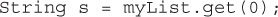

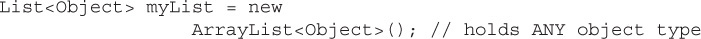

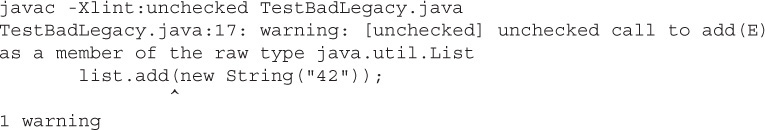

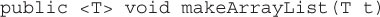

As of Java 5, you’ll want to say

This kind of declaration follows the object-oriented programming principle of “coding to an interface,” and it makes use of generics. We’ll say lots more about generics later in this chapter, but for now, just know that, as of Java 5, the <String> syntax is the way that you declare a collection’s type. (Prior to Java 5, there was no way to specify the type of a collection, and when we cover generics, we’ll talk about the implications of mixing Java 5 [typed] and pre-Java 5 [untyped] collections.)

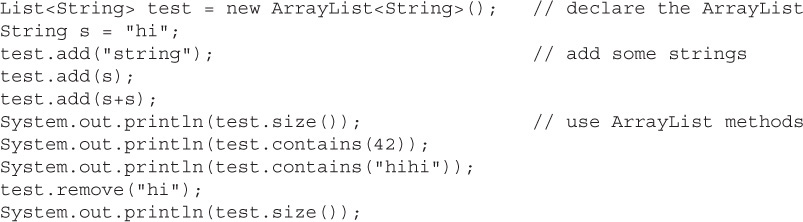

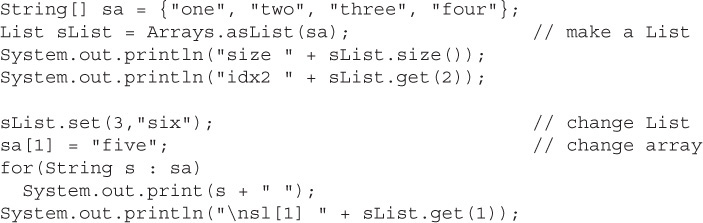

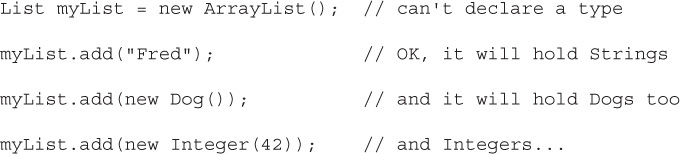

In many ways, ArrayList<String> is similar to a String[] in that it declares a container that can hold only strings, but it’s more powerful than a String[]. Let’s look at some of the capabilities that an ArrayList has:

which produces

There’s a lot going on in this small program. Notice that when we declared the ArrayList we didn’t give it a size. Then we were able to ask the ArrayList for its size, we were able to ask whether it contained specific objects, we removed an object right out from the middle of it, and then we rechecked its size.

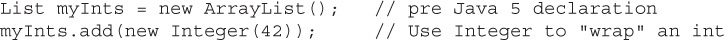

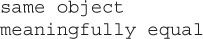

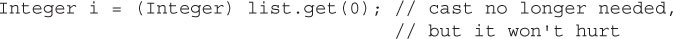

In general, collections can hold Objects but not primitives. Prior to Java 5, a common use for the so-called “wrapper classes” (e.g., Integer, Float, Boolean, and so on) was to provide a way to get primitives into and out of collections. Prior to Java 5, you had to “wrap” a primitive manually before you could put it into a collection. With Java 5, primitives still have to be wrapped, but autoboxing takes care of it for you.

In the previous example, we create an instance of class Integer with a value of 42. We’ve created an entire object to “wrap around” a primitive value. As of Java 5, we can say:

In this last example, we are still adding an Integer object to myInts (not an int primitive); it’s just that autoboxing handles the wrapping for us. There are some sneaky implications when we need to use wrapper objects; let’s take a closer look…

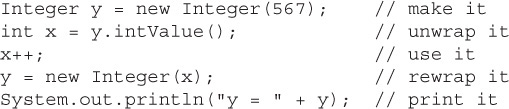

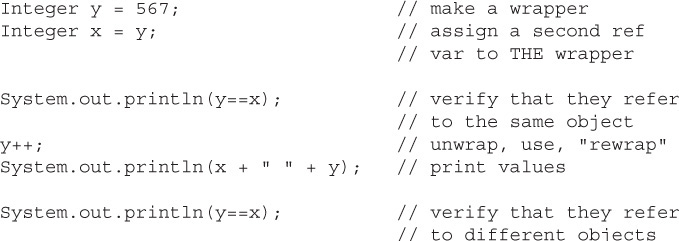

In the old, pre–Java 5 days, if you wanted to make a wrapper, unwrap it, use it, and then rewrap it, you might do something like this:

Now, with new and improved Java 5, you can say

Both examples produce the following output:

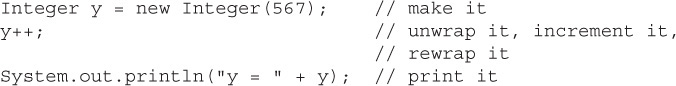

And yes, you read that correctly. The code appears to be using the postincrement operator on an object reference variable! But it’s simply a convenience. Behind the scenes, the compiler does the unboxing and reassignment for you. Earlier, we mentioned that wrapper objects are immutable… this example appears to contradict that statement. It sure looks like y’s value changed from 567 to 568. What actually happened, however, is that a second wrapper object was created and its value was set to 568. If only we could access that first wrapper object, we could prove it…

Let’s try this:

Which produces the output:

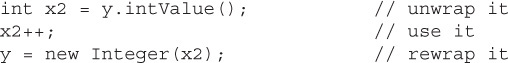

So, under the covers, when the compiler got to the line y++; it had to substitute something like this:

Just as we suspected, there’s gotta be a call to new in there somewhere.

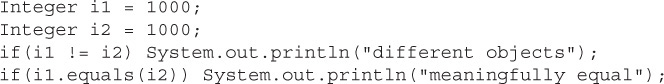

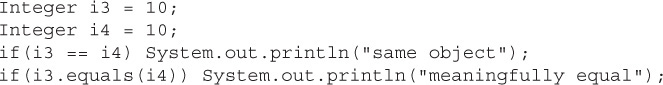

We just used == to do a little exploration of wrappers. Let’s take a more thorough look at how wrappers work with ==, !=, and equals().The API developers decided that for all the wrapper classes, two objects are equal if they are of the same type and have the same value. It shouldn’t be surprising that

produces the output

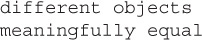

It’s just two wrapper objects that happen to have the same value. Because they have the same int value, the equals() method considers them to be “meaningfully equivalent,” and therefore returns true. How about this one:

This example produces the output:

Yikes! The equals() method seems to be working, but what happened with == and !=? Why is != telling us that i1 and i2 are different objects, when == is saying that i3 and i4 are the same object? In order to save memory, two instances of the following wrapper objects (created through boxing) will always be == when their primitive values are the same:

Boolean

Byte

Character from \u0000 to \u007f (7f is 127 in decimal)

Short and Integer from –128 to 127

When == is used to compare a primitive to a wrapper, the wrapper will be unwrapped and the comparison will be primitive to primitive.

As we discussed earlier, it’s common to use wrappers in conjunction with collections. Any time you want your collection to hold objects and primitives, you’ll want to use wrappers to make those primitives collection-compatible. The general rule is that boxing and unboxing work wherever you can normally use a primitive or a wrapped object. The following code demonstrates some legal ways to use boxing:

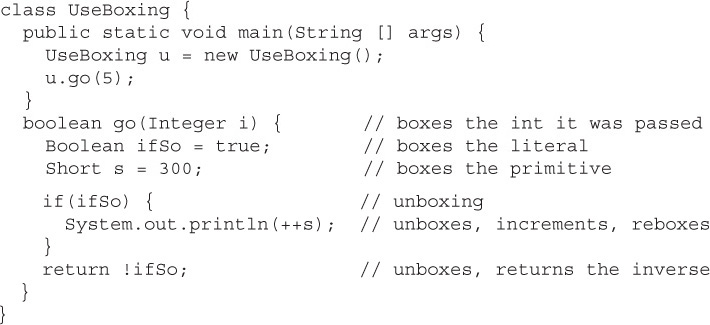

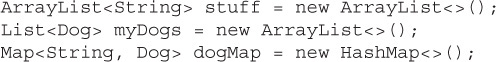

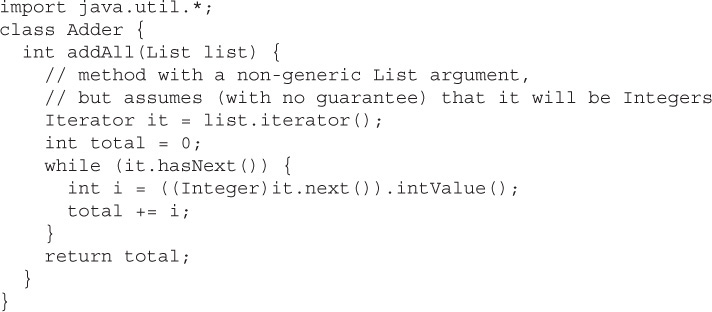

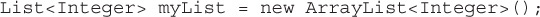

In the OCA part of the book, we discussed several small additions/improvements to the language that were added under the name “Project Coin.” The last Project Coin improvement we’ll discuss in this book is the “diamond syntax.” We’ve already seen several examples of declaring type-safe collections, and as we go deeper into collections, we’ll see lots more like this:

Notice that the type parameters are duplicated in these declarations. As of Java 7, these declarations could be simplified to:

Notice that in the simpler Java 7 declarations, the right side of the declaration included the two characters “<>,” which together make a diamond shape—doh!

You cannot swap these; for example, the following declaration is NOT legal:

For the purposes of the exam, that’s all you’ll need to know about the diamond operator. For the remainder of the book, we’ll use the pre-diamond syntax and the Java 7 diamond syntax somewhat randomly—just like the real world!

Sorting and searching topics were added to the exam as of Java 5. Both collections and arrays can be sorted and searched using methods in the API.

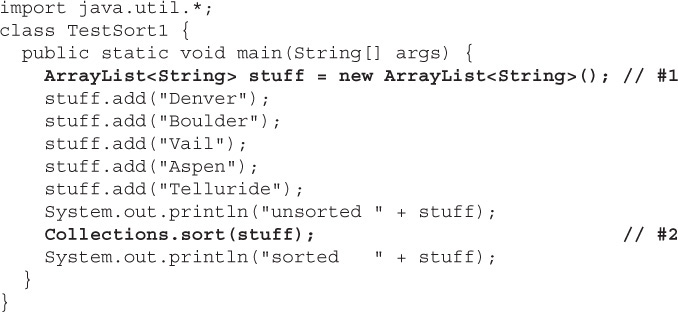

Let’s start with something simple, like sorting an ArrayList of strings alphabetically. What could be easier? Okay, we’ll wait while you go find ArrayList’s sort() method… got it? Of course, ArrayList doesn’t give you any way to sort its contents, but the java.util.Collections class does

This produces something like this:

Line 1 is declaring an ArrayList of Strings, and line 2 is sorting the ArrayList alphabetically. We’ll talk more about the Collections class, along with the Arrays class, in a later section; for now, let’s keep sorting stuff.

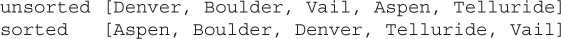

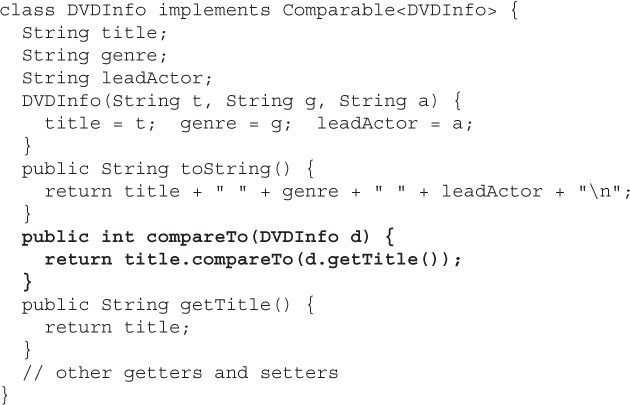

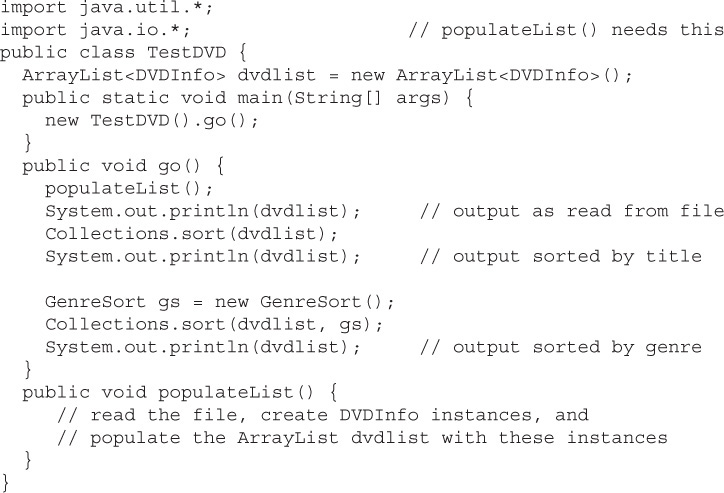

Let’s imagine we’re building the ultimate home-automation application. Today we’re focused on the home entertainment center, and more specifically, the DVD control center. We’ve already got the file I/O software in place to read and write data between the dvdInfo.txt file and instances of class DVDInfo. Here are the key aspects of the class:

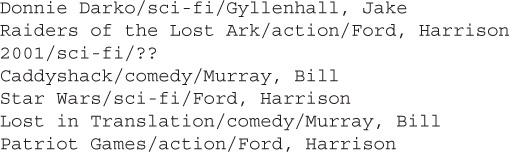

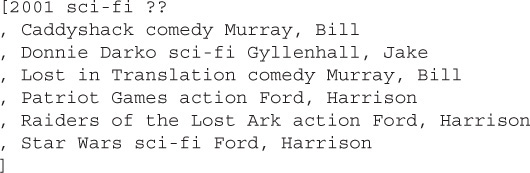

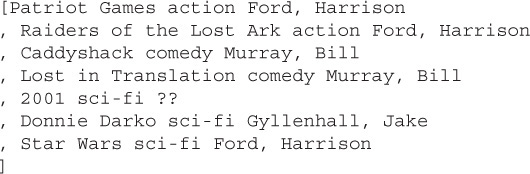

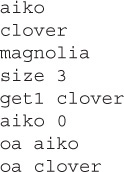

Here’s the DVD data that’s in the dvdinfo.txt file:

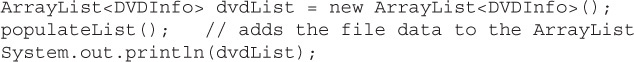

In our home-automation application, we want to create an instance of DVDInfo for each line of data we read in from the dvdInfo.txt file. For each instance, we will parse the line of data (remember String.split()?) and populate DVDInfo’s three instance variables. Finally, we want to put all of the DVDInfo instances into an ArrayList. Imagine that the populateList() method (shown next) does all of this. Here is a small piece of code from our application:

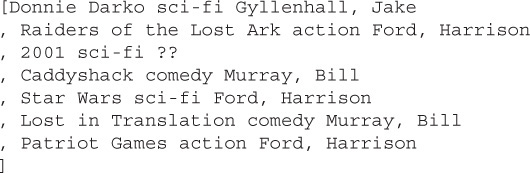

You might get output like this:

(Note: We overrode DVDInfo’s toString() method, so when we invoked println() on the ArrayList, it invoked toString() for each instance.)

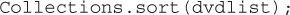

Now that we’ve got a populated ArrayList, let’s sort it:

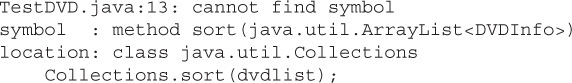

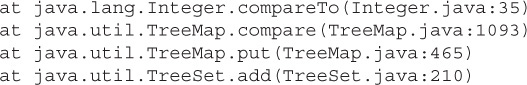

Oops! You get something like this:

What’s going on here? We know that the Collections class has a sort() method, yet this error implies that Collections does NOT have a sort() method that can take a dvdlist. That means there must be something wrong with the argument we’re passing (dvdlist).

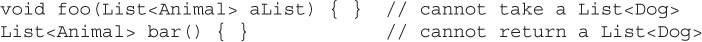

If you’ve already figured out the problem, our guess is that you did it without the help of the obscure error message shown earlier… How the heck do you sort instances of DVDInfo? Why were we able to sort instances of String? When you look up Collections.sort() in the API, your first reaction might be to panic. Hang tight—once again, the generics section will help you read that weird-looking method signature. If you read the description of the one-arg sort() method, you’ll see that the sort() method takes a List argument, and that the objects in the List must implement an interface called Comparable. It turns out that String implements Comparable, and that’s why we were able to sort a list of Strings using the Collections.sort() method.

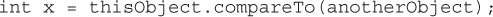

The Comparable interface is used by the Collections.sort() method and the java.util.Arrays.sort() method to sort Lists and arrays of objects, respectively. To implement Comparable, a class must implement a single method, compareTo(). Here’s an invocation of compareTo():

The compareTo() method returns an int with the following characteristics:

Negative If

Negative If thisObject < anotherObject

Zero If

Zero If thisObject == anotherObject

Positive If

Positive If thisObject > anotherObject

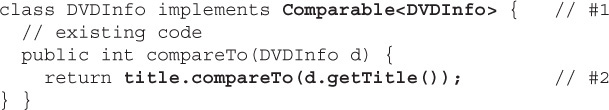

The sort() method uses compareTo() to determine how the List or object array should be sorted. Since you get to implement compareTo() for your own classes, you can use whatever weird criteria you prefer to sort instances of your classes. Returning to our earlier example for class DVDInfo, we can take the easy way out and use the String class’s implementation of compareTo():

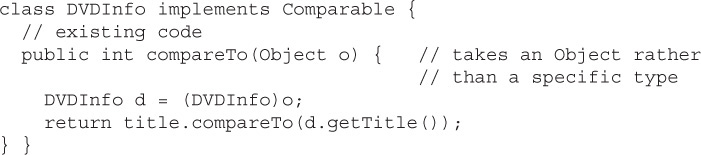

In line 1, we declare that class DVDInfo implements Comparable in such a way that DVDInfo objects can be compared to other DVDInfo objects. In line 2, we implement compareTo() by comparing the two DVDInfo object’s titles. Since we know that the titles are strings and that String implements Comparable, this is an easy way to sort our DVDInfo objects by title. Before generics came along in Java 5, you would have had to implement Comparable using something like this:

This is still legal, but you can see that it’s both painful and risky because you have to do a cast, and you need to verify that the cast will not fail before you try it.

Putting it all together, our DVDInfo class should now look like this:

Now, when we invoke Collections.sort(dvdList), we get

Hooray! Our ArrayList has been sorted by title. Of course, if we want our home-automation system to really rock, we’ll probably want to sort DVD collections in lots of different ways. Since we sorted our ArrayList by implementing the compareTo() method, we seem to be stuck. We can only implement compareTo() once in a class, so how do we go about sorting our classes in an order different from what we specify in our compareTo() method? Good question. As luck would have it, the answer is coming up next.

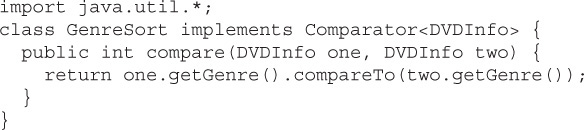

While you were looking up the Collections.sort() method, you might have noticed that there is an overloaded version of sort() that takes both a List AND something called a Comparator. The Comparator interface gives you the capability to sort a given collection any number of different ways. The other handy thing about the Comparator interface is that you can use it to sort instances of any class—even classes you can’t modify—unlike the Comparable interface, which forces you to change the class whose instances you want to sort. The Comparator interface is also very easy to implement, having only one method, compare(). Here’s a small class that can be used to sort a List of DVDInfo instances by genre:

The Comparator.compare() method returns an int whose meaning is the same as the Comparable.compareTo() method’s return value. In this case, we’re taking advantage of that by asking compareTo() to do the actual comparison work for us. Here’s a test program that lets us test both our Comparable code and our new Comparator code:

You’ve already seen the first two output lists; here’s the third:

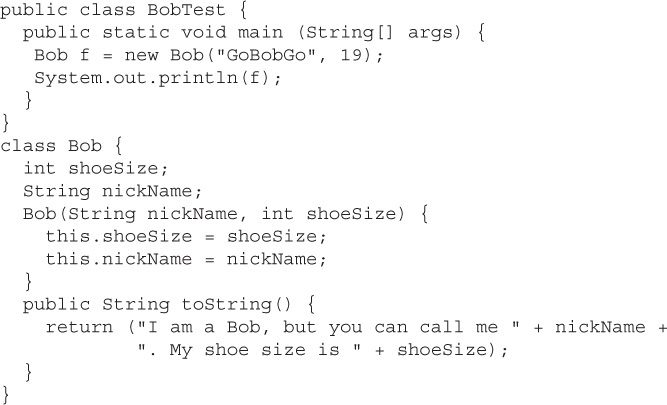

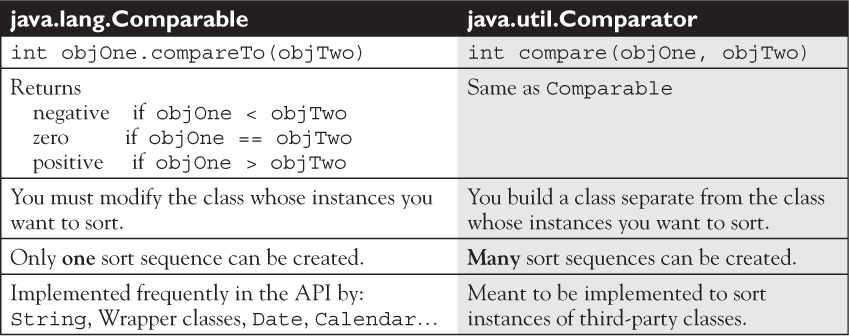

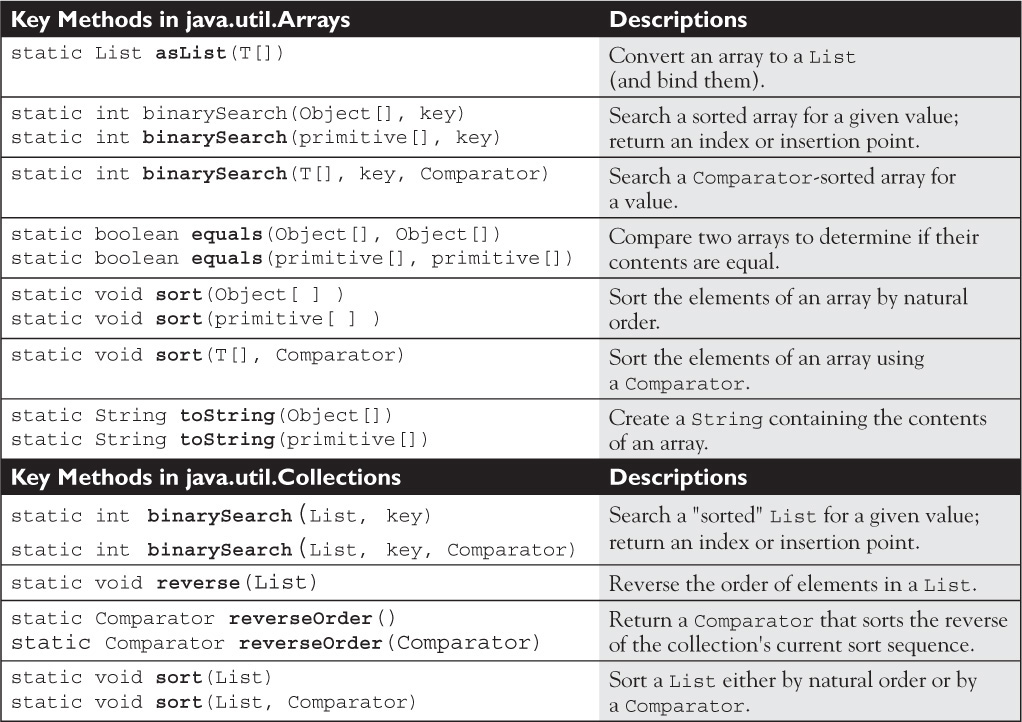

Because the Comparable and Comparator interfaces are so similar, expect the exam to try to confuse you. For instance, you might be asked to implement the compareTo() method in the Comparator interface. Study Table 11-3 to burn into your mind the differences between these two interfaces.

TABLE 11-3 Comparing Comparable to Comparator

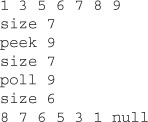

We’ve been using the java.util.Collections class to sort collections; now let’s look at using the java.util.Arrays class to sort arrays. The good news is that sorting arrays of objects is just like sorting collections of objects. The Arrays.sort() method is overloaded in the same way the Collections.sort() method is:

Arrays.sort(arrayToSort)

Arrays.sort(arrayToSort, Comparator)

In addition, the Arrays.sort() method (the one argument version), is overloaded about a million times to provide a couple of sort methods for every type of primitive. The Arrays.sort(myArray) methods that sort primitives always sort based on natural order. Don’t be fooled by an exam question that tries to sort a primitive array using a Comparator.

Finally, remember that the sort() methods for both the Collections class and the Arrays class are static methods, and that they alter the objects they are sorting instead of returning a different sorted object.

The Collections class and the Arrays class both provide methods that allow you to search for a specific element. When searching through collections or arrays, the following rules apply:

Searches are performed using the

Searches are performed using the binarySearch() method.

Successful searches return the

Successful searches return the int index of the element being searched.

Unsuccessful searches return an

Unsuccessful searches return an int index that represents the insertion point. The insertion point is the place in the collection/array where the element would be inserted to keep the collection/array properly sorted. Because positive return values and 0 indicate successful searches, the binarySearch() method uses negative numbers to indicate insertion points. Since 0 is a valid result for a successful search, the first available insertion point is -1. Therefore, the actual insertion point is represented as (-(insertion point) -1). For instance, if the insertion point of a search is at element 2, the actual insertion point returned will be -3.

The collection/array being searched must be sorted before you can search it.

The collection/array being searched must be sorted before you can search it.

If you attempt to search an array or collection that has not already been sorted, the results of the search will not be predictable.

If you attempt to search an array or collection that has not already been sorted, the results of the search will not be predictable.

If the collection/array you want to search was sorted in natural order, it must be searched in natural order. (Usually, this is accomplished by NOT sending a

If the collection/array you want to search was sorted in natural order, it must be searched in natural order. (Usually, this is accomplished by NOT sending a Comparator as an argument to the binarySearch() method.)

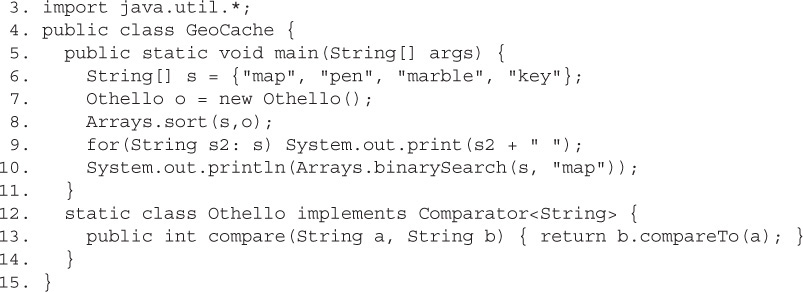

If the collection/array you want to search was sorted using a

If the collection/array you want to search was sorted using a Comparator, it must be searched using the same Comparator, which is passed as the second argument to the binarySearch() method. Remember that Comparators cannot be used when searching arrays of primitives.

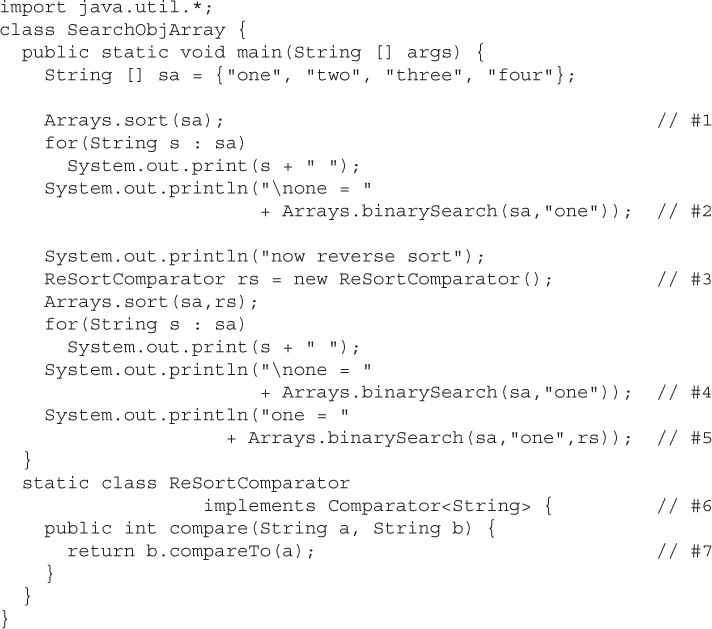

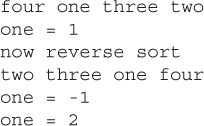

Let’s take a look at a code sample that exercises the binarySearch() method:

which produces something like this:

Here’s what happened:

#1 Sort the

#1 Sort the sa array, alphabetically (the natural order).

#2 Search for the location of element

#2 Search for the location of element “one”, which is 1.

#3 Make a

#3 Make a Comparator instance. On the next line, we re-sort the array using the Comparator.

#4 Attempt to search the array. We didn’t pass the

#4 Attempt to search the array. We didn’t pass the binarySearch() method the Comparator we used to sort the array, so we got an incorrect (undefined) answer.

#5 Search again, passing the

#5 Search again, passing the Comparator to binarySearch(). This time, we get the correct answer, 2.

#6 We define the

#6 We define the Comparator; it’s okay for this to be an inner class. (We’ll be discussing inner classes in Chapter 12.)

#7 By switching the use of the arguments in the invocation of

#7 By switching the use of the arguments in the invocation of compareTo(), we get an inverted sort.

A couple of methods allow you to convert arrays to Lists and Lists to arrays. The List and Set classes have toArray() methods, and the Arrays class has a method called asList().

The Arrays.asList() method copies an array into a List. The API says, “Returns a fixed-size list backed by the specified array. (Changes to the returned list ‘write through’ to the array.)” When you use the asList() method, the array and the List become joined at the hip. When you update one of them, the other is updated automatically. Let’s take a look:

Notice that when we print the final state of the array and the List, they have both been updated with each other’s changes. Wouldn’t something like this behavior make a great exam question?

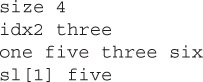

Now let’s take a look at the toArray() method. There’s nothing too fancy going on with the toArray() method; it comes in two flavors: one that returns a new Object array, and one that uses the array you send it as the destination array:

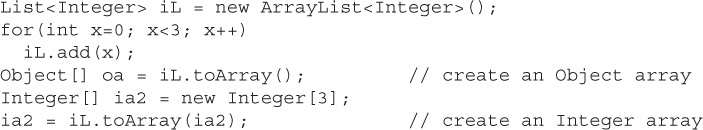

Remember that Lists are usually used to keep things in some kind of order. You can use a LinkedList to create a first-in, first-out queue. You can use an ArrayList to keep track of what locations were visited and in what order. Notice that in both of these examples, it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that duplicates might occur. In addition, Lists allow you to manually override the ordering of elements by adding or removing elements via the element’s index. Before Java 5 and the enhanced for loop, the most common way to examine a List “element by element” was through the use of an Iterator. You’ll still find Iterators in use in the Java code you encounter, and you might just find an Iterator or two on the exam. An Iterator is an object that’s associated with a specific collection. It lets you loop through the collection step by step. The two Iterator methods you need to understand for the exam are

boolean hasNext() Returns true if there is at least one more element in the collection being traversed. Invoking hasNext() does NOT move you to the next element of the collection.

Object next() This method returns the next object in the collection AND moves you forward to the element after the element just returned.

Let’s look at a little code that uses a List and an Iterator:

This produces

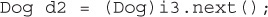

First off, we used generics syntax to create the Iterator (an Iterator of type Dog). Because of this, when we used the next() method, we didn’t have to cast the Object returned by next() to a Dog. We could have declared the Iterator like this:

But then we would have had to cast the returned value:

The rest of the code demonstrates using the size(), get(), indexOf(), and toArray() methods. There shouldn’t be any surprises with these methods. Later in the chapter, Table 11-7 will list all of the List, Set, and Map methods you should be familiar with for the exam. As a last warning, remember that List is an interface!

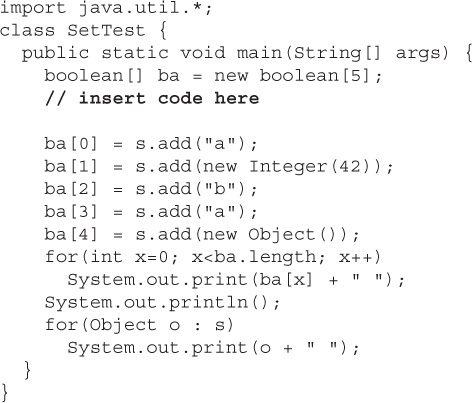

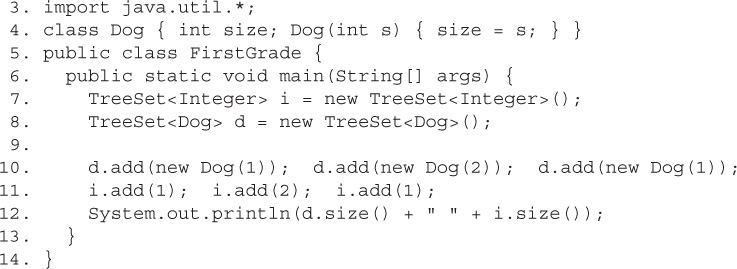

Remember that Sets are used when you don’t want any duplicates in your collection. If you attempt to add an element to a set that already exists in the set, the duplicate element will not be added, and the add() method will return false. Remember, HashSets tend to be very fast because, as we discussed earlier, they use hashcodes.

You can also create a TreeSet, which is a Set whose elements are sorted. You must use caution when using a TreeSet (we’re about to explain why):

If you insert the following line of code, you’ll get output that looks something like this:

It’s important to know that the order of objects printed in the second for loop is not predictable: HashSets do not guarantee any ordering. Also, notice that the fourth invocation of add() failed because it attempted to insert a duplicate entry (a String with the value a) into the Set.

If you insert this line of code, you’ll get something like this:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ClassCastException: java.lang. String

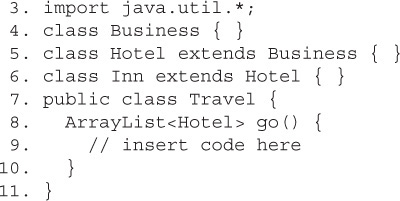

The issue is that whenever you want a collection to be sorted, its elements must be mutually comparable. Remember that unless otherwise specified, objects of different types are not mutually comparable.

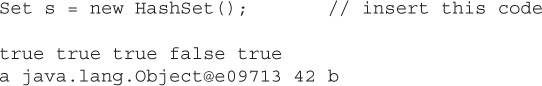

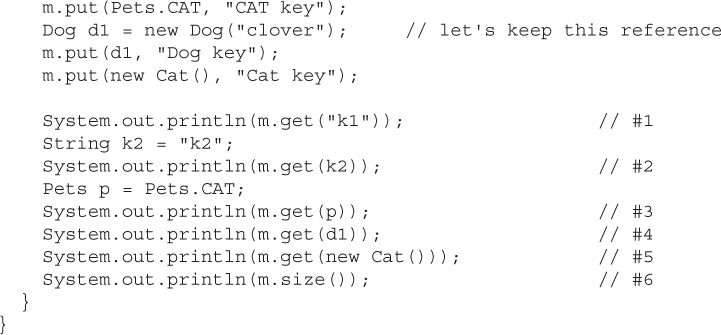

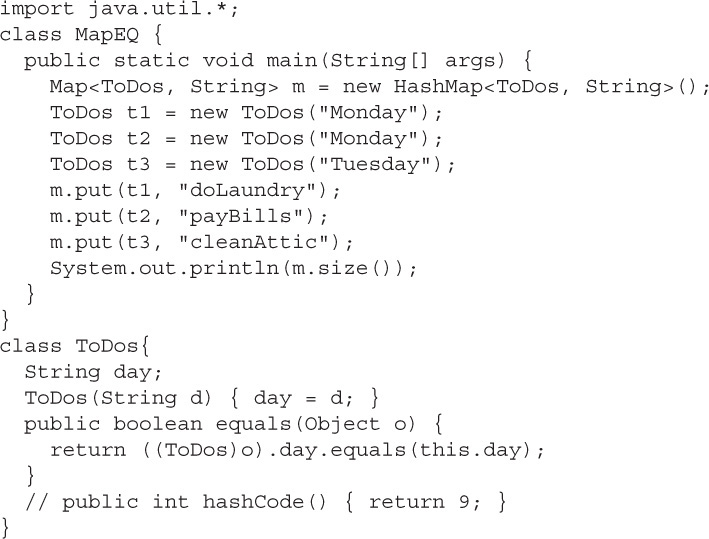

Remember that when you use a class that implements Map, any classes that you use as a part of the keys for that map must override the hashCode() and equals() methods. (Well, you only have to override them if you’re interested in retrieving stuff from your Map. Seriously, it’s legal to use a class that doesn’t override equals() and hashCode() as a key in a Map; your code will compile and run, you just won’t find your stuff.) Here’s some crude code demonstrating the use of a HashMap:

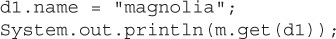

which produces something like this:

Let’s review the output. The first value retrieved is a Dog object (your value will vary). The second value retrieved is an enum value (DOG). The third value retrieved is a String; note that the key was an enum value. Pop quiz: What’s the implication of the fact that we were able to successfully use an enum as a key?

The implication of this is that enums override equals() and hashCode(). And, if you look at the java.lang.Enum class in the API, you will see that, in fact, these methods have been overridden.

The fourth output is a String. The important point about this output is that the key used to retrieve the String was made of a Dog object. The fifth output is null. The important point here is that the get() method failed to find the Cat object that was inserted earlier. (The last line of output confirms that, indeed, 5 key/value pairs exist in the Map.) Why didn’t we find the Cat key String? Why did it work to use an instance of Dog as a key, when using an instance of Cat as a key failed?

It’s easy to see that Dog overrode equals() and hashCode() while Cat didn’t.

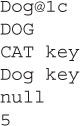

Let’s take a quick look at hashcodes. We used an incredibly simplistic hashcode formula in the Dog class—the hashcode of a Dog object is the length of the instance’s name. So in this example, the hashcode = 6. Let’s compare the following two hashCode() methods:

Time for another pop quiz: Are the preceding two hashcodes legal? Will they successfully retrieve objects from a Map? Which will be faster?

The answer to the first two questions is Yes and Yes. Neither of these hashcodes will be very efficient (in fact, they would both be incredibly inefficient), but they are both legal, and they will both work. The answer to the last question is that the first hashcode will be a little bit faster than the second hashcode. In general, the more unique hashcodes a formula creates, the faster the retrieval will be. The first hashcode formula will generate a different code for each name length (for instance, the name Robert will generate one hashcode and the name Benchley will generate a different hashcode). The second hashcode formula will always produce the same result, 4, so it will be slower than the first.

Our last Map topic is what happens when an object used as a key has its values changed? If we add two lines of code to the end of the earlier MapTest.main(),

we get something like this:

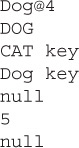

The Dog that was previously found now cannot be found. Because the Dog.name variable is used to create the hashcode, changing the name changed the value of the hashcode. As a final quiz for hashcodes, determine the output for the following lines of code if they’re added to the end of MapTest.main():

Remember that the hashcode is equal to the length of the name variable. When you study a problem like this, it can be useful to think of the two stages of retrieval:

1. Use the hashCode() method to find the correct bucket.

2. Use the equals() method to find the object in the bucket.

In the first call to get(), the hashcode is 8 (magnolia) and it should be 6 (clover), so the retrieval fails at step 1 and we get null. In the second call to get(), the hashcodes are both 6, so step 1 succeeds. Once in the correct bucket (the “length of name = 6” bucket), the equals() method is invoked, and since Dog’s equals() method compares names, equals() succeeds, and the output is Dog key. In the third invocation of get(), the hashcode test succeeds, but the equals() test fails because arthur is NOT equal to clover.

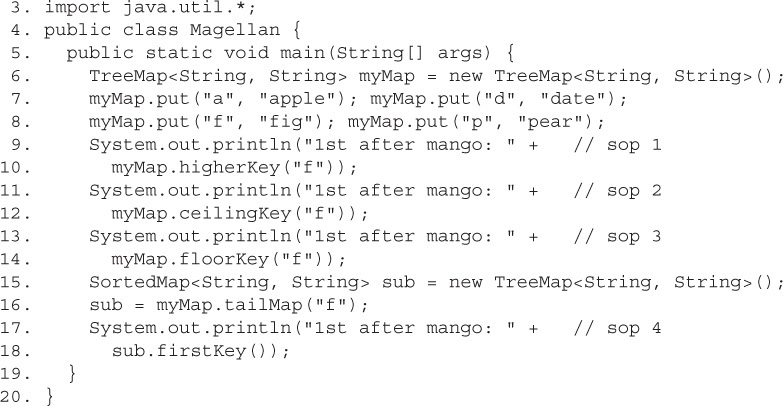

Note: This section and the next (“Backed Collections”) are fairly complex, and there is a good chance that OCP 7 candidates will NOT get any questions on these topics. On the other hand, OCPJP 6 candidates are likely to be tested on these topics.

We’ve talked about searching lists and arrays. Let’s turn our attention to searching TreeSets and TreeMaps. Java 6 introduced (among other things) two new interfaces: java.util.NavigableSet and java.util.NavigableMap. For the purposes of the exam, you’re interested in how TreeSet and TreeMap implement these interfaces.

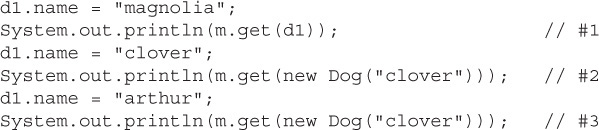

Imagine that the Santa Cruz–Monterey ferry has an irregular schedule. Let’s say that we have the daily Santa Cruz departure times stored in military time in a TreeSet. Let’s look at some code that determines two things:

1. The last ferry that leaves before 4 PM (1600 hours)

2. The first ferry that leaves after 8 PM (2000 hours)

This should produce the following:

As you can see in the preceding code, before the addition of the NavigableSet interface, zeroing in on an arbitrary spot in a Set—using the methods available in Java 5—was a compute-expensive and clunky proposition. On the other hand, using the new Java 6 methods lower() and higher(), the code becomes a lot cleaner.

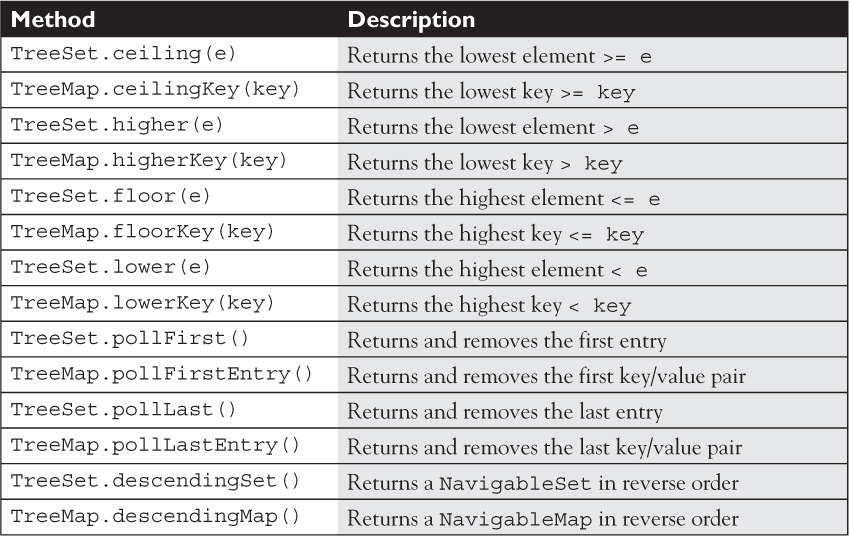

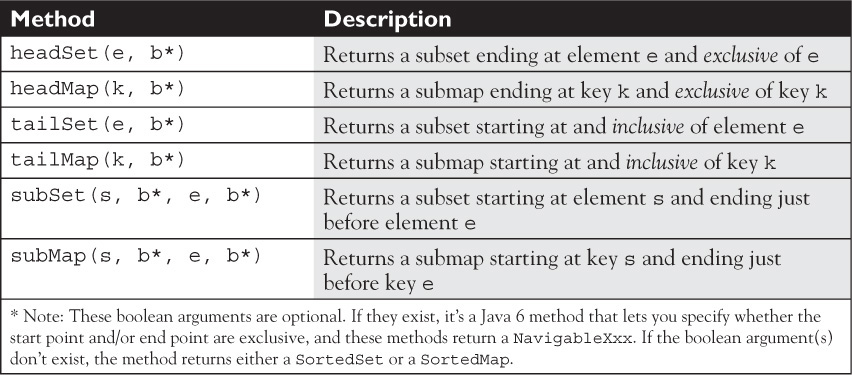

For the purpose of the exam, the NavigableSet methods related to this type of navigation are lower(), floor(), higher(), and ceiling(), and the mostly parallel NavigableMap methods are lowerKey(), floorKey(), ceilingKey(), and higherKey(). The difference between lower() and floor() is that lower() returns the element less than the given element, and floor() returns the element less than or equal tothe given element. Similarly, higher() returns the element greater than the given element, and ceiling() returns the element greater than or equal tothe given element. Table 11-4 summarizes the methods you should know for the exam.

TABLE 11-4 Important “Navigation–Related Methods

In addition to the methods we just discussed, there are a few more new Java 6 methods that could be considered “navigation” methods. (Okay, it’s a little bit of a stretch to call these “navigation” methods, but just play along.)

Although the idea of polling isn’t new to Java 6 (as you’ll see in a minute, PriorityQueue had a poll() method before Java 6), it is new to TreeSet and TreeMap. The idea of polling is that we want both to retrieve and remove an element from either the beginning or the end of a collection. In the case of TreeSet, pollFirst() returns and removes the first entry in the set, and pollLast() returns and removes the last. Similarly, TreeMap now provides pollFirstEntry() and pollLastEntry() to retrieve and remove key/value pairs.

Also new to Java 6 for TreeSet and TreeMap are methods that return a collection in the reverse order of the collection on which the method was invoked. The important methods for the exam are TreeSet.descendingSet() and TreeMap.descendingMap().

Table 11-4 summarizes the “navigation” methods you’ll need to know for the exam.

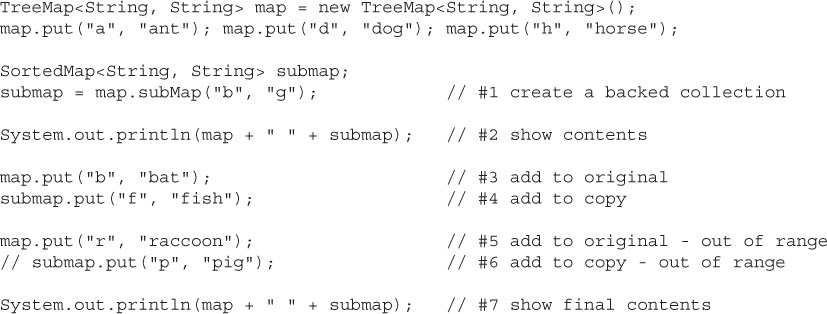

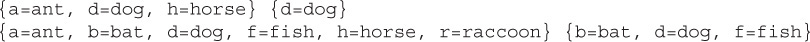

Some of the classes in the java.util package support the concept of “backed collections.” We’ll use a little code to help explain the idea:

This should produce something like this:

The important method in this code is the TreeMap.subMap() method. It’s easy to guess (and it’s correct) that the subMap() method is making a copy of a portion of the TreeMap named map. The first line of output verifies the conclusions we’ve just drawn.

What happens next is powerful, and a little bit unexpected (now we’re getting to why they’re called backed collections). When we add key/value pairs to either the original TreeMap or the partial-copy SortedMap, the new entries were automatically added to the other collection—sometimes. When submap was created, we provided a value range for the new collection. This range defines not only what should be included when the partial copy is created, but also defines the range of values that can be added to the copy. As we can verify by looking at the second line of output, we can add new entries to either collection within the range of the copy, and the new entries will show up in both collections. In addition, we can add a new entry to the original collection, even if it’s outside the range of the copy. In this case, the new entry will show up only in the original—it won’t be added to the copy because it’s outside the copy’s range. Notice that we commented out line 6. If you attempt to add an out-of-range entry to the copied collection, an exception will be thrown.

For the exam, you’ll need to understand the basics just explained, plus a few more details about three methods from TreeSet—headSet(), subSet(), and tailSet()—and three methods from TreeMap—headMap(), subMap(), and tailMap(). As with the navigation-oriented methods we just discussed, we can see a lot of parallels between the TreeSet and the TreeMap methods. The headSet()/headMap() methods create a subset that starts at the beginning of the original collection and ends at the point specified by the method’s argument. The tailSet()/tailMap() methods create a subset that starts at the point specified by the method’s argument and goes to the end of the original collection. Finally, the subSet()/subMap() methods allow you to specify both the start and end points for the subset collection you’re creating.

As you might expect, the question of whether the subsetted collection’s end points are inclusive or exclusive is a little tricky. The good news is that for the exam you have to remember only that when these methods are invoked with end point and boolean arguments, the boolean always means “is inclusive”. A little more good news is that all you have to know for the exam is that, unless specifically indicated by a boolean argument, a subset’s starting point will always be inclusive. Finally, you’ll notice when you study the API that all of the methods we’ve been discussing here have an overloaded version that’s new to Java 6. The older methods return either a SortedSet or a SortedMap; the new Java 6 methods return either a NavigableSet or a NavigableMap. Table 11-5 summarizes these methods.

TABLE 11-5 Important “Backed Collection” Methods for TreeSet and TreeMap

Note: Having completed the Navigable Collections and Backed Collections discussions, we’re now back to topics that all candidates (OCPJP 5 and 6 and OCP 7), are likely to be tested on.

For the exam, you’ll need to understand several of the classes that implement the Deque interface. These classes will be discussed in Chapter 14, the concurrency chapter.

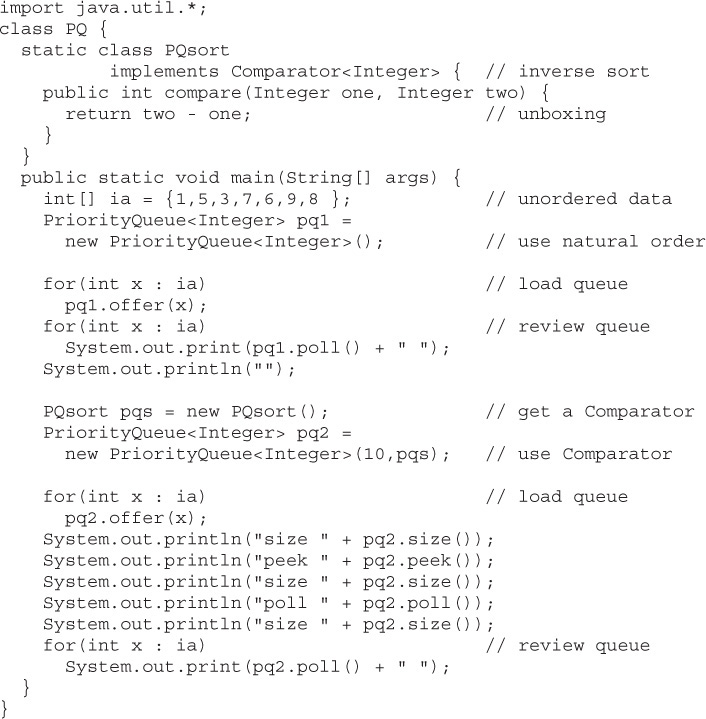

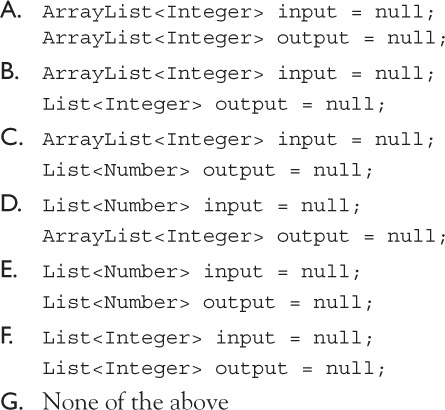

Other than those concurrency-related classes, the last collection class you’ll need to understand for the exam is the PriorityQueue. Unlike basic queue structures that are first-in, first-out by default, a PriorityQueue orders its elements using a user-defined priority. The priority can be as simple as natural ordering (in which, for instance, an entry of 1 would be a higher priority than an entry of 2). In addition, a PriorityQueue can be ordered using a Comparator, which lets you define any ordering you want. Queues have a few methods not found in other collection interfaces: peek(), poll(), and offer().

This code produces something like this:

Let’s look at this in detail. The first for loop iterates through the ia array and uses the offer() method to add elements to the PriorityQueue named pq1. The second for loop iterates through pq1 using the poll() method, which returns the highest-priority entry in pq1 AND removes the entry from the queue. Notice that the elements are returned in priority order (in this case, natural order). Next, we create a Comparator—in this case, a Comparator that orders elements in the opposite of natural order. We use this Comparator to build a second PriorityQueue, pq2, and we load it with the same array we used earlier. Finally, we check the size of pq2 before and after calls to peek() and poll(). This confirms that peek() returns the highest-priority element in the queue without removing it, and poll() returns the highest-priority element AND removes it from the queue. Finally, we review the remaining elements in the queue.

For these two classes, we’ve already covered the trickier methods you might encounter on the exam. Table 11-6 lists a summary of the methods you should be aware of. (Note: The T[] syntax will be explained later in this chapter; for now, think of it as meaning “any array that’s NOT an array of primitives.”)

TABLE 11-6 Key Methods in Arrays and Collections

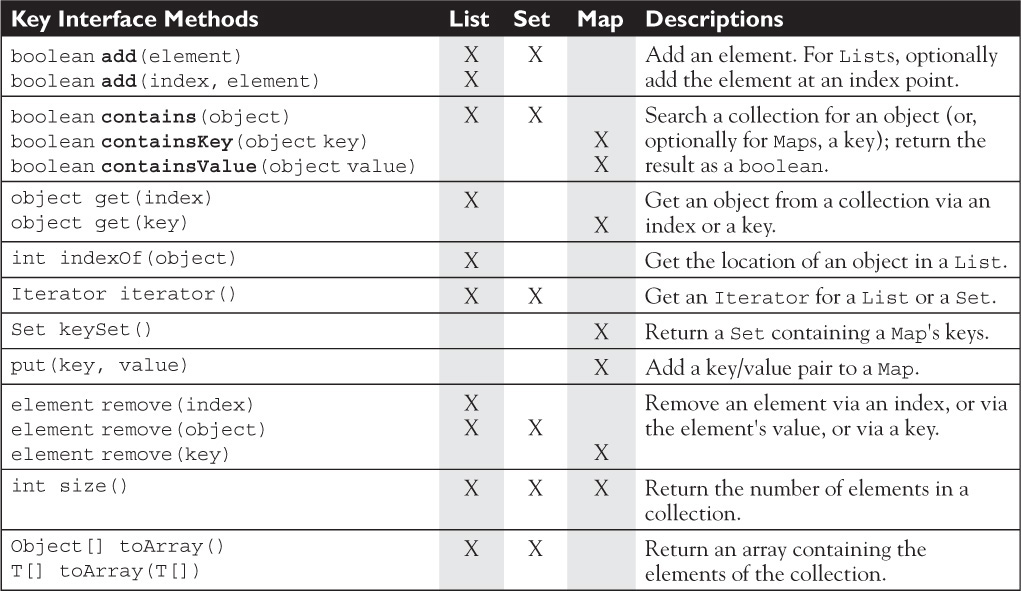

For these four interfaces, we’ve already covered the trickier methods you might encounter on the exam. Table 11-7 lists a summary of the List, Set, and Map methods you should be aware of, and—if you’re an OCPJP 6 candidate—don’t forget the new “Navigable” methods floor, lower, ceiling, and higher that we discussed a few pages back.

TABLE 11-7 Key Methods in List, Set, and Map

For the exam, the PriorityQueue methods that are important to understand are offer() (which is similar to add()), peek() (which retrieves the element at the head of the queue but doesn’t delete it), and poll() (which retrieves the head element and removes it from the queue).

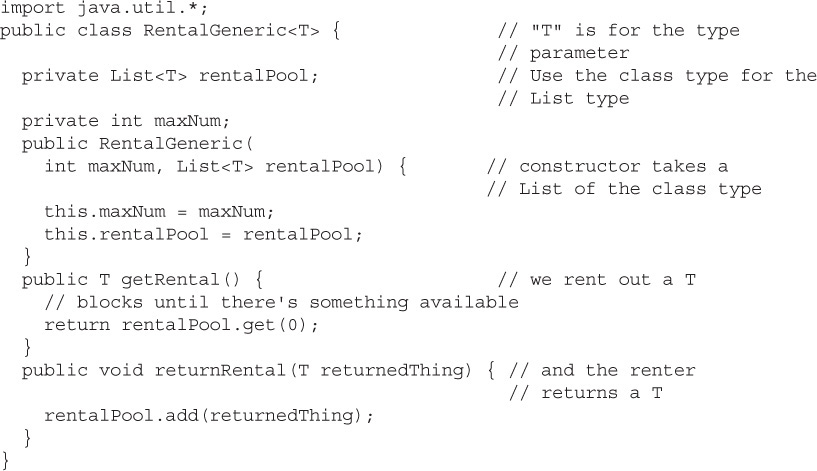

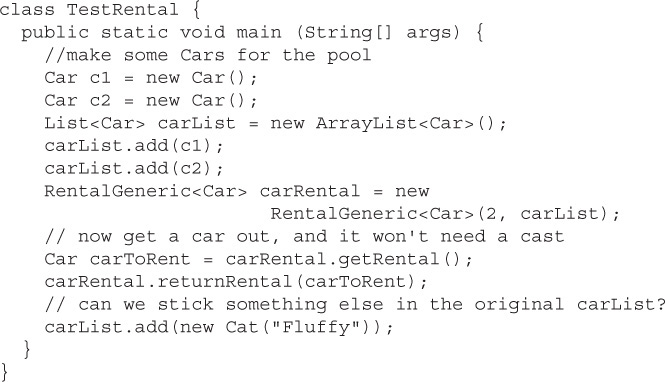

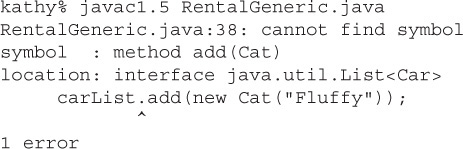

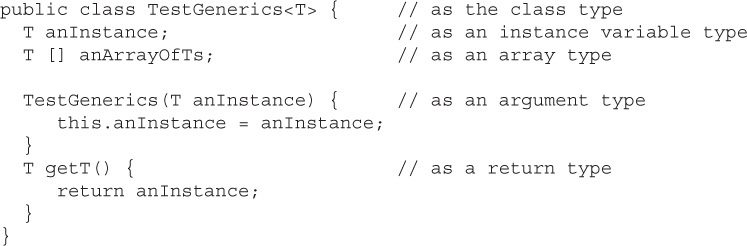

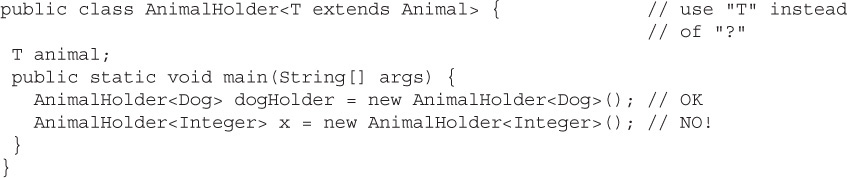

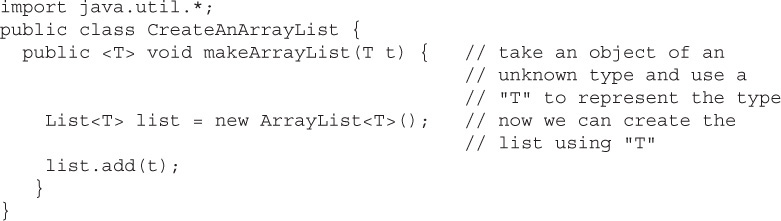

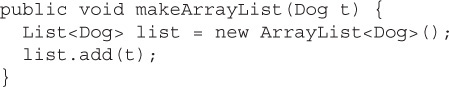

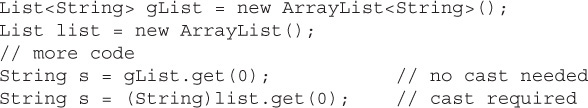

4.1 Create a generic class.

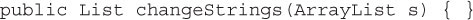

4.3 Analyze the interoperability of collections that use raw and generic types.

Now would be a great time to take a break. Those two innocent-sounding objectives unpack into a world of complexity. When you’re well rested, come on back and strap yourself in—the next several pages might get bumpy.

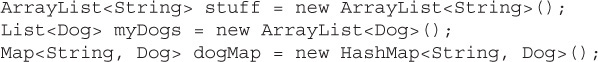

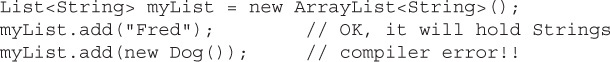

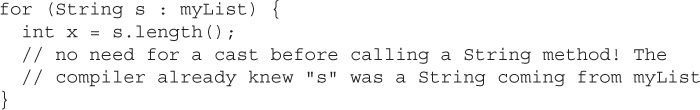

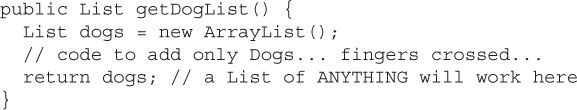

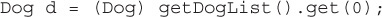

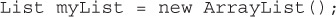

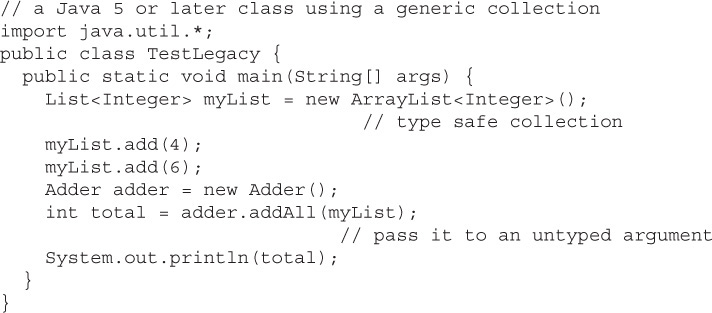

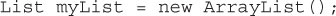

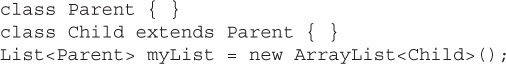

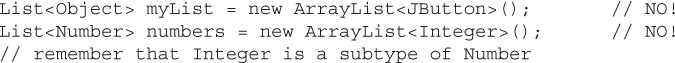

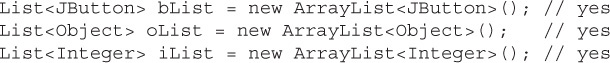

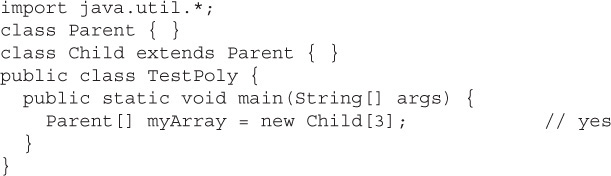

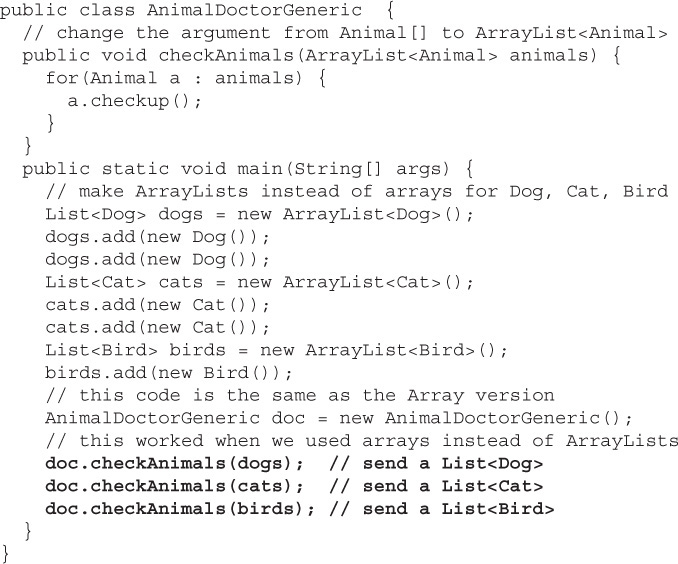

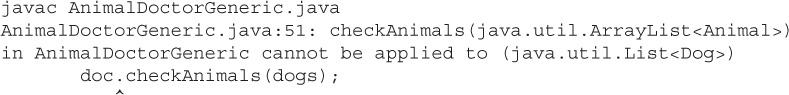

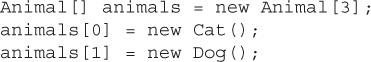

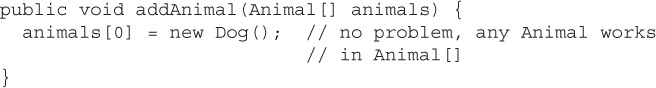

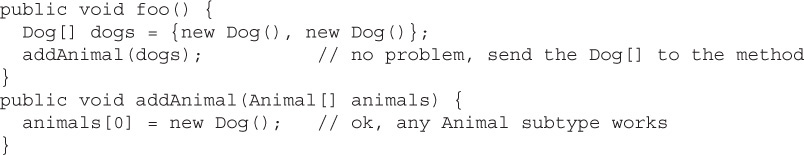

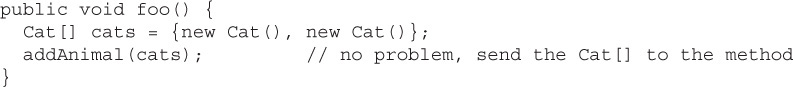

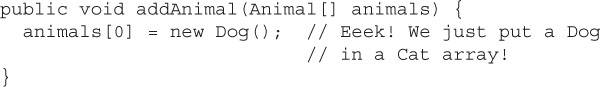

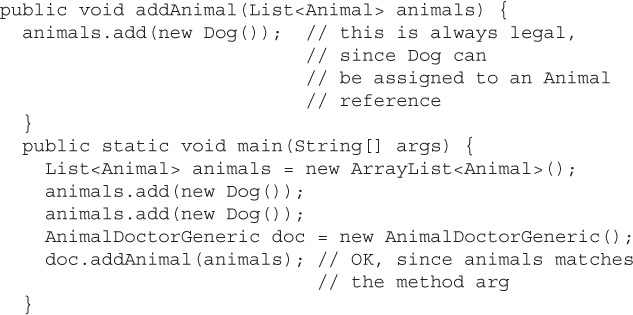

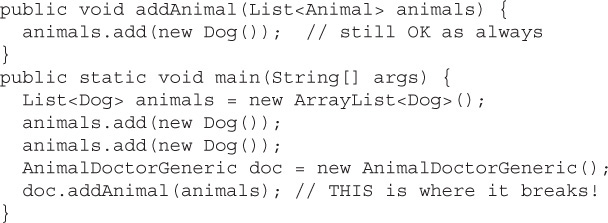

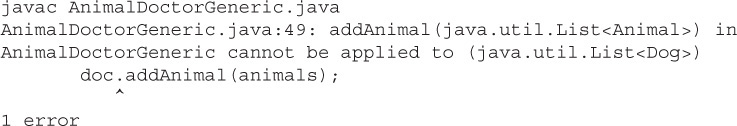

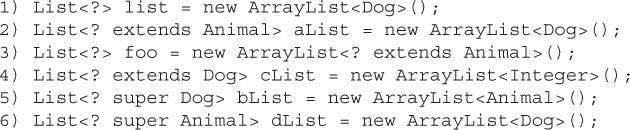

Arrays in Java have always been type-safe—an array declared as type String (String []) can’t accept Integers (or ints), Dogs, or anything other than Strings. But remember that before Java 5 there was no syntax for declaring a type-safe collection. To make an ArrayList of Strings, you said,

or the polymorphic equivalent

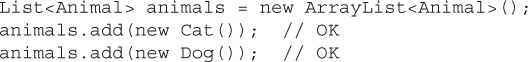

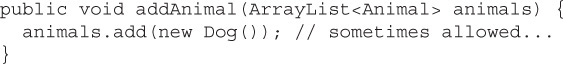

There was no syntax that let you specify that myList will take Strings and only Strings. And with no way to specify a type for the ArrayList, the compiler couldn’t enforce that you put only things of the specified type into the list. As of Java 5, we can use generics, and while they aren’t only for making type-safe collections, that’s just about all most developers use generics for. So, while generics aren’t just for collections, think of collections as the overwhelming reason and motivation for adding generics to the language.

And it was not an easy decision, nor has it been an entirely welcome addition. Because along with all the nice, happy type-safety, generics come with a lot of baggage—most of which you’ll never see or care about—but there are some gotchas that come up surprisingly quickly. We’ll cover the ones most likely to show up in your own code, and those are also the issues that you’ll need to know for the exam.

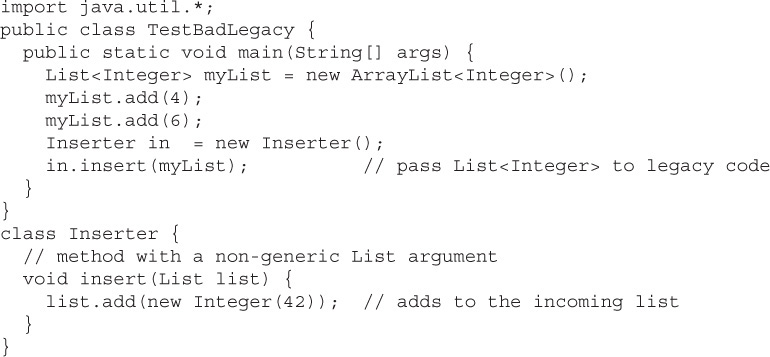

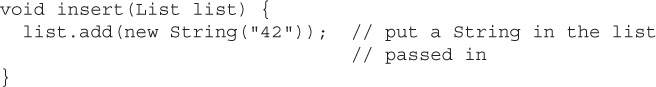

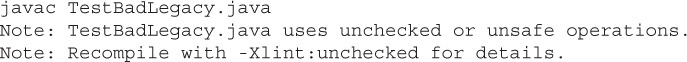

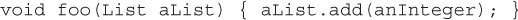

The biggest challenge for the Java engineers in adding generics to the language (and the main reason it took them so long) was how to deal with legacy code built without generics. The Java engineers obviously didn’t want to break everyone’s existing Java code, so they had to find a way for Java classes with both type-safe (generic) and nontype-safe (nongeneric/pre–Java 5) collections to still work together. Their solution isn’t the friendliest, but it does let you use older nongeneric code, as well as use generic code that plays with nongeneric code. But notice we said “plays” and not “plays WELL.”

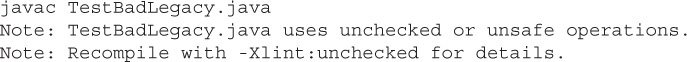

While you can integrate Java 5 and later generic code with legacy, nongeneric code, the consequences can be disastrous, and unfortunately, most of the disasters happen at runtime, not compile time. Fortunately, though, most compilers will generate warnings to tell you when you’re using unsafe (meaning nongeneric) collections.

The Java 7 exam covers both pre–Java 5 (nongeneric) and generic-style collections, and you’ll see questions that expect you to understand the tricky problems that can come from mixing nongeneric and generic code together. And like some of the other topics in this book, you could fill an entire book if you really wanted to cover every detail about generics, but the exam (and this book) covers more than most developers will ever need to use.

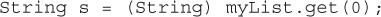

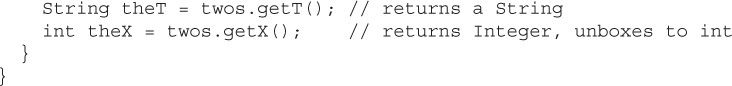

Here’s a review of a pre–Java 5 ArrayList intended to hold Strings. (We say “intended” because that’s about all you had—good intentions—to make sure that the ArrayList would hold only Strings.)

A nongeneric collection can hold any kind of object! A nongeneric collection is quite happy to hold anything that is NOT a primitive.