Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill• Use Class Members

• Understand Primitive Casting

• Understand Variable Scope

• Differentiate Between Primitive Variables and Reference Variables

• Determine the Effects of Passing Variables into Methods

• Understand Object Lifecycle and Garbage Collection

Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill

Q&A Self Test

For most people, understanding the basics of the stack and the heap makes it far easier to understand topics like argument passing, polymorphism, threads, exceptions, and garbage collection. In this section, we’ll stick to an overview, but we’ll expand these topics several more times throughout the book.

For the most part, the various pieces (methods, variables, and objects) of Java programs live in one of two places in memory: the stack or the heap. For now, we’re concerned about only three types of things—instance variables, local variables, and objects:

Instance variables and objects live on the heap.

Instance variables and objects live on the heap.

Local variables live on the stack.

Local variables live on the stack.

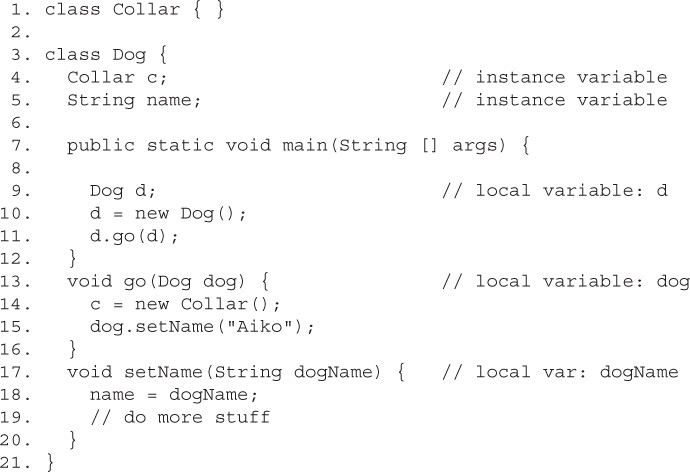

Let’s take a look at a Java program and how its various pieces are created and map into the stack and the heap:

Figure 3-1 shows the state of the stack and the heap once the program reaches line 19. Following are some key points:

FIGURE 3-1 Overview of the stack and the heap

Line 7—

Line 7—main() is placed on the stack.

Line 9—Reference variable

Line 9—Reference variable d is created on the stack, but there’s no Dog object yet.

Line 10—A new

Line 10—A new Dog object is created and is assigned to the d reference variable.

Line 11—A copy of the reference variable

Line 11—A copy of the reference variable d is passed to the go() method.

Line 13—The

Line 13—The go() method is placed on the stack, with the dog parameter as a local variable.

Line 14—A new

Line 14—A new Collar object is created on the heap and assigned to Dog’s instance variable.

Line 17—

Line 17—setName() is added to the stack, with the dogName parameter as its local variable.

Line 18—The

Line 18—The name instance variable now also refers to the String object.

Notice that two different local variables refer to the same

Notice that two different local variables refer to the same Dog object.

Notice that one local variable and one instance variable both refer to the same

Notice that one local variable and one instance variable both refer to the same String Aiko.

After Line 19 completes,

After Line 19 completes, setName() completes and is removed from the stack. At this point the local variable dogName disappears, too, although the String object it referred to is still on the heap.

2.1 Declare and initialize variables.

2.2 Differentiate between object references and primitive variables.

2.3 Read or write to object fields.

A primitive literal is merely a source code representation of the primitive data types—in other words, an integer, floating-point number, boolean, or character that you type in while writing code. The following are examples of primitive literals:

There are four ways to represent integer numbers in the Java language: decimal (base 10), octal (base 8), hexadecimal (base 16), and as of Java 7, binary (base 2). Most exam questions with integer literals use decimal representations, but the few that use octal, hexadecimal, or binary are worth studying for. Even though the odds that you’ll ever actually use octal in the real world are astronomically tiny, they were included in the exam just for fun. Before we look at the four ways to represent integer numbers, let’s first discuss a new feature added to Java 7, literals with underscores.

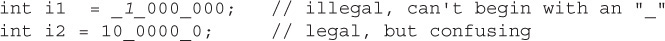

Numeric Literals with Underscores (Upgrade Exam Topic 1.2) As of Java 7, numeric literals can be declared using underscore characters (_), ostensibly to improve readability. Let’s compare a pre-Java 7 declaration to an easier to read Java 7 declaration:

The main rule you have to keep track of is that you CANNOT use the underscore literal at the beginning or end of the literal. The potential gotcha here is that you’re free to use the underscore in “weird” places:

As a final note, remember that you can use the underscore character for any of the numeric types (including doubles and floats), but for doubles and floats, you CANNOT add an underscore character directly next to the decimal point.

Decimal Literals Decimal integers need no explanation; you’ve been using them since grade one or earlier. Chances are you don’t keep your checkbook in hex. (If you do, there’s a Geeks Anonymous [GA] group ready to help.) In the Java language, they are represented as is, with no prefix of any kind, as follows:

Binary Literals (Upgrade Exam Topic 1.2) Also new to Java 7 is the addition of binary literals. Binary literals can use only the digits 0 and 1. Binary literals must start with either 0B or 0b, as shown:

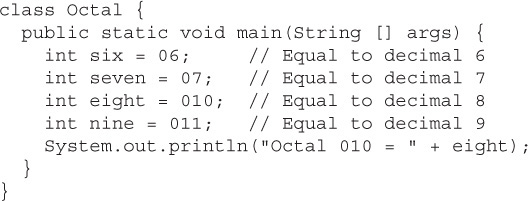

Octal Literals Octal integers use only the digits 0 to 7. In Java, you represent an integer in octal form by placing a zero in front of the number, as follows:

You can have up to 21 digits in an octal number, not including the leading zero. If we run the preceding program, it displays the following:

Hexadecimal Literals Hexadecimal (hex for short) numbers are constructed using 16 distinct symbols. Because we never invented single-digit symbols for the numbers 10 through 15, we use alphabetic characters to represent these digits. Counting from 0 through 15 in hex looks like this:

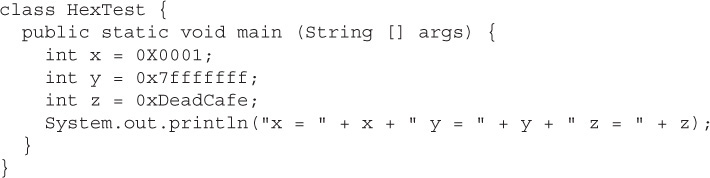

Java will accept uppercase or lowercase letters for the extra digits (one of the few places Java is not case-sensitive!). You are allowed up to 16 digits in a hexadecimal number, not including the prefix 0x (or 0X) or the optional suffix extension L, which will be explained a bit later in the chapter. All of the following hexadecimal assignments are legal:

Running HexTest produces the following output:

Don’t be misled by changes in case for a hexadecimal digit or the x preceding it. 0XCAFE and 0xcafe are both legal and have the same value.

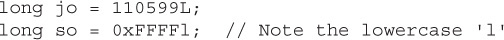

All four integer literals (binary, octal, decimal, and hexadecimal) are defined as int by default, but they may also be specified as long by placing a suffix of L or l after the number:

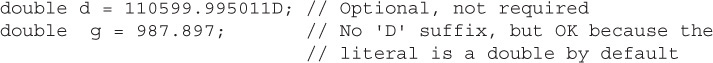

Floating-point numbers are defined as a number, a decimal symbol, and more numbers representing the fraction. In the following example, the number 11301874.9881024 is the literal value:

Floating-point literals are defined as double (64 bits) by default, so if you want to assign a floating-point literal to a variable of type float (32 bits), you must attach the suffix F or f to the number. If you don’t do this, the compiler will complain about a possible loss of precision, because you’re trying to fit a number into a (potentially) less precise “container.” The F suffix gives you a way to tell the compiler, “Hey, I know what I’m doing, and I’ll take the risk, thank you very much.”

You may also optionally attach a D or d to double literals, but it is not necessary because this is the default behavior.

Look for numeric literals that include a comma; here’s an example:

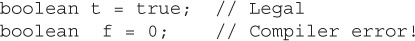

Boolean literals are the source code representation for boolean values. A boolean value can be defined only as true or false. Although in C (and some other languages) it is common to use numbers to represent true or false, this will not work in Java. Again, repeat after me: “Java is not C++.”

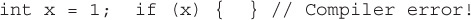

Be on the lookout for questions that use numbers where booleans are required. You might see an if test that uses a number, as in the following:

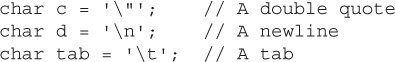

A char literal is represented by a single character in single quotes:

You can also type in the Unicode value of the character, using the Unicode notation of prefixing the value with \u as follows:

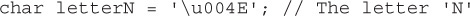

Remember, characters are just 16-bit unsigned integers under the hood. That means you can assign a number literal, assuming it will fit into the unsigned 16-bit range (0 to 65535). For example, the following are all legal:

And the following are not legal and produce compiler errors:

You can also use an escape code (the backslash) if you want to represent a character that can’t be typed in as a literal, including the characters for linefeed, newline, horizontal tab, backspace, and quotes:

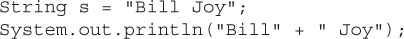

A string literal is a source code representation of a value of a String object. The following is an example of two ways to represent a string literal:

Although strings are not primitives, they’re included in this section because they can be represented as literals—in other words, they can be typed directly into code. The only other nonprimitive type that has a literal representation is an array, which we’ll look at later in the chapter.

Assigning a value to a variable seems straightforward enough; you simply assign the stuff on the right side of the = to the variable on the left. Well, sure, but don’t expect to be tested on something like this:

No, you won’t be tested on the no-brainer (technical term) assignments. You will, however, be tested on the trickier assignments involving complex expressions and casting. We’ll look at both primitive and reference variable assignments. But before we begin, let’s back up and peek inside a variable. What is a variable? How are the variable and its value related?

Variables are just bit holders, with a designated type. You can have an int holder, a double holder, a Button holder, and even a String[] holder. Within that holder is a bunch of bits representing the value. For primitives, the bits represent a numeric value (although we don’t know what that bit pattern looks like for boolean, luckily, we don’t care). A byte with a value of 6, for example, means that the bit pattern in the variable (the byte holder) is 00000110, representing the 8 bits.

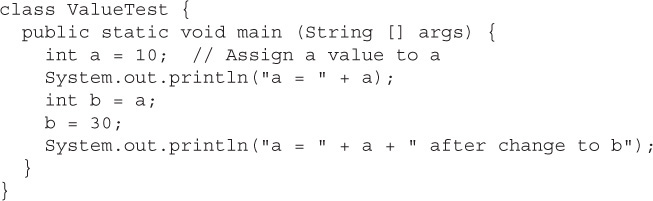

So the value of a primitive variable is clear, but what’s inside an object holder? If you say,

what’s inside the Button holder b? Is it the Button object? No! A variable referring to an object is just that—a reference variable. A reference variable bit holder contains bits representing a way to get to the object. We don’t know what the format is. The way in which object references are stored is virtual-machine specific (it’s a pointer to something, we just don’t know what that something really is). All we can say for sure is that the variable’s value is not the object, but rather a value representing a specific object on the heap. Or null. If the reference variable has not been assigned a value or has been explicitly assigned a value of null, the variable holds bits representing—you guessed it—null. You can read

as “The Button variable b is not referring to any object.”

So now that we know a variable is just a little box o’ bits, we can get on with the work of changing those bits. We’ll look first at assigning values to primitives and then finish with assignments to reference variables.

The equal (=) sign is used for assigning a value to a variable, and it’s cleverly named the assignment operator. There are actually 12 assignment operators, but only the 5 most commonly used assignment operators are on the exam, and they are covered in Chapter 4.

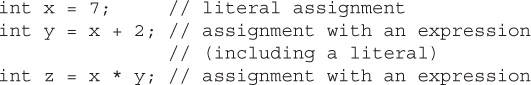

You can assign a primitive variable using a literal or the result of an expression.

The most important point to remember is that a literal integer (such as 7) is always implicitly an int. Thinking back to Chapter 1, you’ll recall that an int is a 32-bit value. No big deal if you’re assigning a value to an int or a long variable, but what if you’re assigning to a byte variable? After all, a byte-sized holder can’t hold as many bits as an int-sized holder. Here’s where it gets weird. The following is legal,

but only because the compiler automatically narrows the literal value to a byte. In other words, the compiler puts in the cast. The preceding code is identical to the foll owing:

It looks as though the compiler gives you a break and lets you take a shortcut with assignments to integer variables smaller than an int. (Everything we’re saying about byte applies equally to char and short, both of which are smaller than an int.) We’re not actually at the weird part yet, by the way.

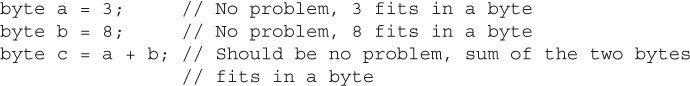

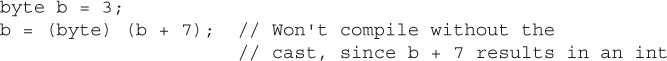

We know that a literal integer is always an int, but more importantly, the result of an expression involving anything int-sized or smaller is always an int. In other words, add two bytes together and you’ll get an int—even if those two bytes are tiny. Multiply an int and a short and you’ll get an int. Divide a short by a byte and you’ll get…an int. Okay, now we’re at the weird part. Check this out:

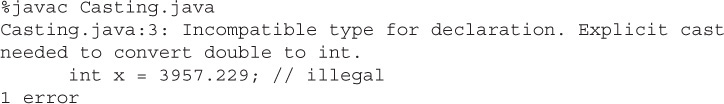

The last line won’t compile! You’ll get an error something like this:

We tried to assign the sum of two bytes to a byte variable, the result of which (11) was definitely small enough to fit into a byte, but the compiler didn’t care. It knew the rule about int-or-smaller expressions always resulting in an int. It would have compiled if we’d done the explicit cast:

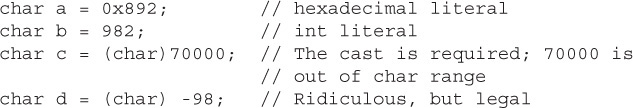

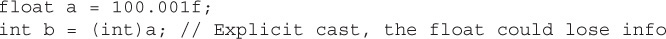

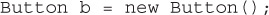

Casting lets you convert primitive values from one type to another. We mentioned primitive casting in the previous section, but now we’re going to take a deeper look. (Object casting was covered in Chapter 2.)

Casts can be implicit or explicit. An implicit cast means you don’t have to write code for the cast; the conversion happens automatically. Typically, an implicit cast happens when you’re doing a widening conversion—in other words, putting a smaller thing (say, a byte) into a bigger container (such as an int). Remember those “possible loss of precision” compiler errors we saw in the assignments section? Those happened when we tried to put a larger thing (say, a long) into a smaller container (such as a short). The large-value-into-small-container conversion is referred to as narrowing and requires an explicit cast, where you tell the compiler that you’re aware of the danger and accept full responsibility.

First we’ll look at an implicit cast:

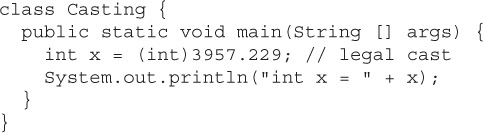

An explicit casts looks like this:

Integer values may be assigned to a double variable without explicit casting, because any integer value can fit in a 64-bit double. The following line demonstrates this:

In the preceding statement, a double is initialized with a long value (as denoted by the L after the numeric value). No cast is needed in this case because a double can hold every piece of information that a long can store. If, however, we want to assign a double value to an integer type, we’re attempting a narrowing conversion and the compiler knows it:

If we try to compile the preceding code, we get an error something like this:

In the preceding code, a floating-point value is being assigned to an integer variable. Because an integer is not capable of storing decimal places, an error occurs. To make this work, we’ll cast the floating-point number to an int:

When you cast a floating-point number to an integer type, the value loses all the digits after the decimal. The preceding code will produce the following output:

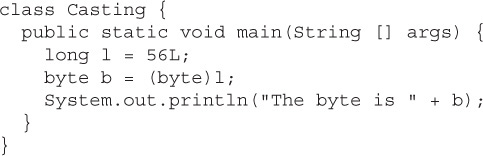

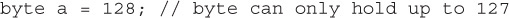

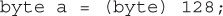

We can also cast a larger number type, such as a long, into a smaller number type, such as a byte. Look at the following:

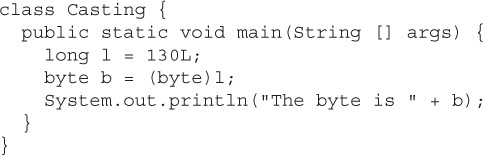

The preceding code will compile and run fine. But what happens if the long value is larger than 127 (the largest number a byte can store)? Let’s modify the code:

The code compiles fine, and when we run it we get the following:

We don’t get a runtime error, even when the value being narrowed is too large for the type. The bits to the left of the lower 8 just…go away. If the leftmost bit (the sign bit) in the byte (or any integer primitive) now happens to be a 1, the primitive will have a negative value.

Casting Primitives

Create a float number type of any value, and assign it to a short using casting.

1. Declare a float variable: float f = 234.56F;

2. Assign the float to a short: short s = (short)f;

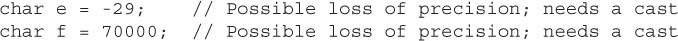

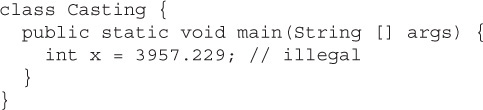

Floating-point numbers have slightly different assignment behavior than integer types. First, you must know that every floating-point literal is implicitly a double (64 bits), not a float. So the literal 32.3, for example, is considered a double. If you try to assign a double to a float, the compiler knows you don’t have enough room in a 32-bit float container to hold the precision of a 64-bit double, and it lets you know. The following code looks good, but it won’t compile:

You can see that 32.3 should fit just fine into a float-sized variable, but the compiler won’t allow it. In order to assign a floating-point literal to a float variable, you must either cast the value or append an f to the end of the literal. The following assignments will compile:

We’ll also get a compiler error if we try to assign a literal value that the compiler knows is too big to fit into the variable.

The preceding code gives us an error something like this:

But then what’s the result? When you narrow a primitive, Java simply truncates the higher-order bits that won’t fit. In other words, it loses all the bits to the left of the bits you’re narrowing to.

Let’s take a look at what happens in the preceding code. There, 128 is the bit pattern 10000000. It takes a full 8 bits to represent 128. But because the literal 128 is an int, we actually get 32 bits, with the 128 living in the rightmost (lower order) 8 bits. So a literal 128 is actually

Take our word for it; there are 32 bits there.

To narrow the 32 bits representing 128, Java simply lops off the leftmost (higher order) 24 bits. What remains is just the 10000000. But remember that a byte is signed, with the leftmost bit representing the sign (and not part of the value of the variable). So we end up with a negative number (the 1 that used to represent 128 now represents the negative sign bit). Remember, to find out the value of a negative number using 2’s complement notation, you flip all of the bits and then add 1. Flipping the 8 bits gives us 01111111, and adding 1 to that gives us 10000000, or back to 128! And when we apply the sign bit, we end up with –128.

You must use an explicit cast to assign 128 to a byte, and the assignment leaves you with the value –128. A cast is nothing more than your way of saying to the compiler, “Trust me. I’m a professional. I take full responsibility for anything weird that happens when those top bits are chopped off.”

That brings us to the compound assignment operators. This will compile:

and it is equivalent to this:

The compound assignment operator += lets you add to the value of b, without putting in an explicit cast. In fact, +=, -=, *=, and /= will all put in an implicit cast.

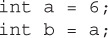

When you assign one primitive variable to another, the contents of the right-hand variable are copied. For example:

This code can be read as, “Assign the bit pattern for the number 6 to the int variable a. Then copy the bit pattern in a, and place the copy into variable b.”

So, both variables now hold a bit pattern for 6, but the two variables have no other relationship. We used the variable a only to copy its contents. At this point, a and b have identical contents (in other words, identical values), but if we change the contents of either a or b, the other variable won’t be affected.

Take a look at the following example:

The output from this program is

Notice the value of a stayed at 10. The key point to remember is that even after you assign a to b, a and b are not referring to the same place in memory. The a and b variables do not share a single value; they have identical copies.

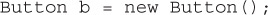

You can assign a newly created object to an object reference variable as follows:

The preceding line does three key things:

Makes a reference variable named

Makes a reference variable named b, of type Button

Creates a new

Creates a new Button object on the heap

Assigns the newly created

Assigns the newly created Button object to the reference variable b

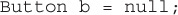

You can also assign null to an object reference variable, which simply means the variable is not referring to any object:

The preceding line creates space for the Button reference variable (the bit holder for a reference value), but it doesn’t create an actual Button object.

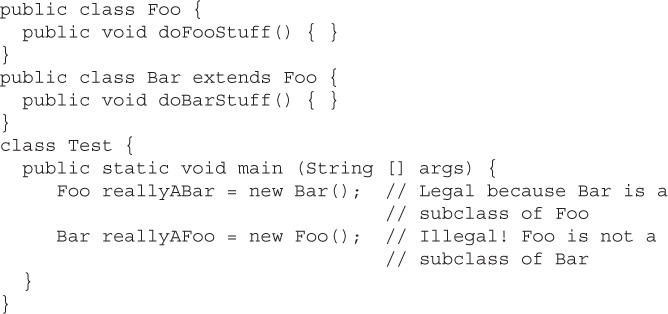

As we discussed in the last chapter, you can also use a reference variable to refer to any object that is a subclass of the declared reference variable type, as follows:

The rule is that you can assign a subclass of the declared type but not a superclass of the declared type. Remember, a Bar object is guaranteed to be able to do anything a Foo can do, so anyone with a Foo reference can invoke Foo methods even though the object is actually a Bar.

In the preceding code, we see that Foo has a method doFooStuff() that someone with a Foo reference might try to invoke. If the object referenced by the Foo variable is really a Foo, no problem. But it’s also no problem if the object is a Bar, since Bar inherited the doFooStuff() method. You can’t make it work in reverse, however. If somebody has a Bar reference, they’re going to invoke doBarStuff(), but if the object is a Foo, it won’t know how to respond.

1.1 Determine the scope of variables.

2.5 Call methods on objects.

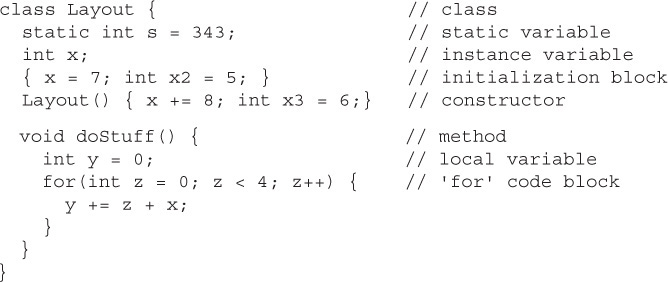

Once you’ve declared and initialized a variable, a natural question is, “How long will this variable be around?” This is a question regarding the scope of variables. And not only is scope an important thing to understand in general, it also plays a big part in the exam. Let’s start by looking at a class file:

As with variables in all Java programs, the variables in this program (s, x, x2, x3, y, and z) all have a scope:

s is a static variable.

x is an instance variable.

y is a local variable (sometimes called a “method local” variable).

z is a block variable.

x2 is an init block variable, a flavor of local variable.

x3 is a constructor variable, a flavor of local variable.

For the purposes of discussing the scope of variables, we can say that there are four basic scopes:

Static variables have the longest scope; they are created when the class is loaded, and they survive as long as the class stays loaded in the Java Virtual Machine (JVM).

Static variables have the longest scope; they are created when the class is loaded, and they survive as long as the class stays loaded in the Java Virtual Machine (JVM).

Instance variables are the next most long-lived; they are created when a new instance is created, and they live until the instance is removed.

Instance variables are the next most long-lived; they are created when a new instance is created, and they live until the instance is removed.

Local variables are next; they live as long as their method remains on the stack. As we’ll soon see, however, local variables can be alive and still be “out of scope.”

Local variables are next; they live as long as their method remains on the stack. As we’ll soon see, however, local variables can be alive and still be “out of scope.”

Block variables live only as long as the code block is executing.

Block variables live only as long as the code block is executing.

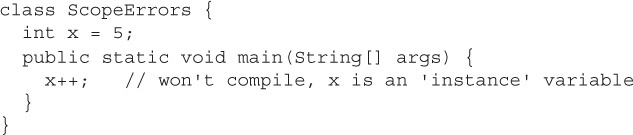

Scoping errors come in many sizes and shapes. One common mistake happens when a variable is shadowed and two scopes overlap. We’ll take a detailed look at shadowing in a few pages. The most common reason for scoping errors is an attempt to access a variable that is not in scope. Let’s look at three common examples of this type of error.

Attempting to access an instance variable from a static context (typically from

Attempting to access an instance variable from a static context (typically from main()):

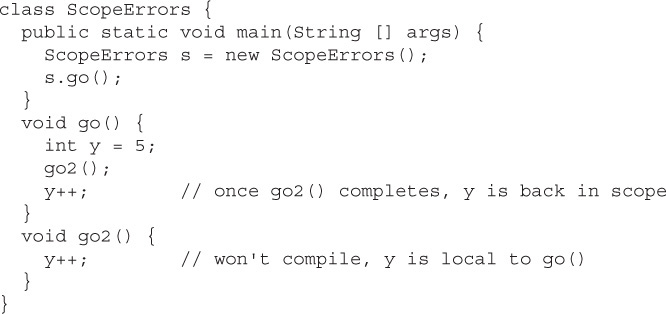

Attempting to access a local variable from a nested method. When a method, say

Attempting to access a local variable from a nested method. When a method, say go(), invokes another method, say go2(), go2() won’t have access to go()’s local variables. While go2() is executing, go()’s local variables are still alive, but they are out of scope. When go2() completes, it is removed from the stack, and go() resumes execution. At this point, all of go()’s previously declared variables are back in scope. For example:

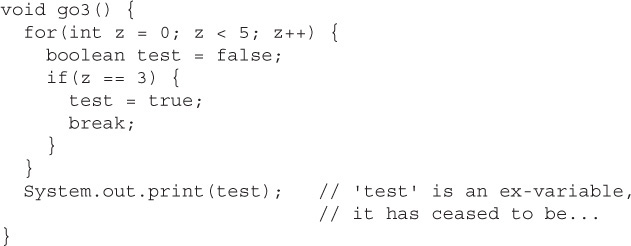

Attempting to use a block variable after the code block has completed. It’s very common to declare and use a variable within a code block, but be careful not to try to use the variable once the block has completed:

Attempting to use a block variable after the code block has completed. It’s very common to declare and use a variable within a code block, but be careful not to try to use the variable once the block has completed:

In the last two examples, the compiler will say something like this:

This is the compiler’s way of saying, “That variable you just tried to use? Well, it might have been valid in the distant past (like one line of code ago), but this is Internet time, baby, I have no memory of such a variable.”

2.1 Declare and initialize variables.

Java gives us the option of initializing a declared variable or leaving it uninitialized. When we attempt to use the uninitialized variable, we can get different behavior depending on what type of variable or array we are dealing with (primitives or objects). The behavior also depends on the level (scope) at which we are declaring our variable. An instance variable is declared within the class but outside any method or constructor, whereas a local variable is declared within a method (or in the argument list of the method).

Local variables are sometimes called stack, temporary, automatic, or method variables, but the rules for these variables are the same regardless of what you call them. Although you can leave a local variable uninitialized, the compiler complains if you try to use a local variable before initializing it with a value, as we shall see.

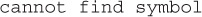

Instance variables (also called member variables) are variables defined at the class level. That means the variable declaration is not made within a method, constructor, or any other initializer block. Instance variables are initialized to a default value each time a new instance is created, although they may be given an explicit value after the object’s superconstructors have completed. Table 3-1 lists the default values for primitive and object types.

TABLE 3-1 Default Values for Primitives and Reference Types

In the following example, the integer year is defined as a class member because it is within the initial curly braces of the class and not within a method’s curly braces:

When the program is started, it gives the variable year a value of zero, the default value for primitive number instance variables.

It’s a good idea to initialize all your variables, even if you’re assigning them with the default value. Your code will be easier to read; programmers who have to maintain your code (after you win the lottery and move to Tahiti) will be grateful.

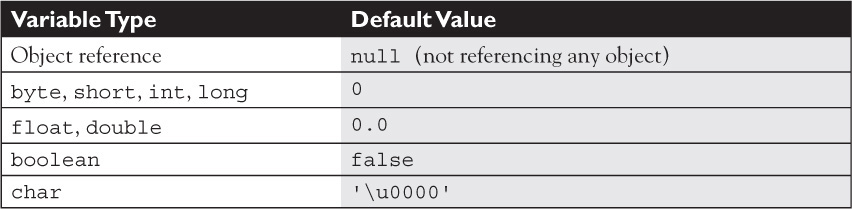

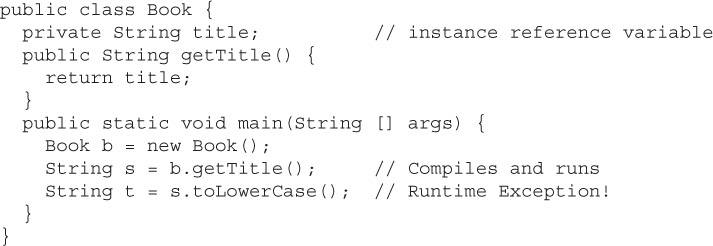

When compared with uninitialized primitive variables, object references that aren’t initialized are a completely different story. Let’s look at the following code:

This code will compile fine. When we run it, the output is

The title variable has not been explicitly initialized with a String assignment, so the instance variable value is null. Remember that null is not the same as an empty String (“”). A null value means the reference variable is not referring to any object on the heap. The following modification to the Book code runs into trouble:

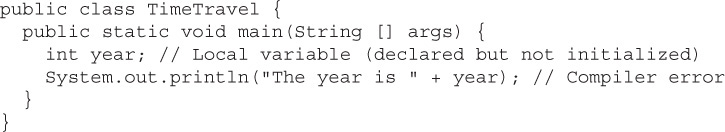

When we try to run the Book class, the JVM will produce something like this:

We get this error because the reference variable title does not point (refer) to an object. We can check to see whether an object has been instantiated by using the keyword null, as the following revised code shows:

The preceding code checks to make sure the object referenced by the variable s is not null before trying to use it. Watch out for scenarios on the exam where you might have to trace back through the code to find out whether an object reference will have a value of null. In the preceding code, for example, you look at the instance variable declaration for title, see that there’s no explicit initialization, recognize that the title variable will be given the default value of null, and then realize that the variable s will also have a value of null. Remember, the value of s is a copy of the value of title (as returned by the getTitle() method), so if title is a null reference, s will be, too.

In Chapter 5 we’ll be taking a very detailed look at declaring, constructing, and initializing arrays and multidimensional arrays. For now, we’re just going to look at the rule for an array element’s default values.

An array is an object; thus, an array instance variable that’s declared but not explicitly initialized will have a value of null, just as any other object reference instance variable. But…if the array is initialized, what happens to the elements contained in the array? All array elements are given their default values—the same default values that elements of that type get when they’re instance variables. The bottom line: Array elements are always, always, always given default values, regardless of where the array itself is declared or instantiated.

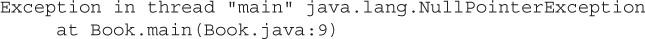

If we initialize an array, object reference elements will equal null if they are not initialized individually with values. If primitives are contained in an array, they will be given their respective default values. For example, in the following code, the array year will contain 100 integers that all equal zero by default:

When the preceding code runs, the output indicates that all 100 integers in the array have a value of zero.

Local variables are defined within a method, and they include a method’s parameters.

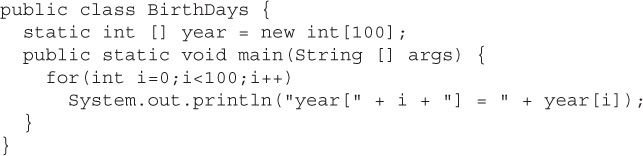

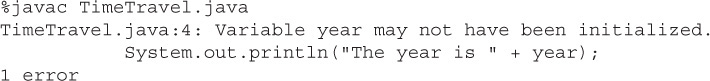

In the following time-travel simulator, the integer year is defined as an automatic variable because it is within the curly braces of a method:

Local variables, including primitives, always, always, always must be initialized before you attempt to use them (though not necessarily on the same line of code). Java does not give local variables a default value; you must explicitly initialize them with a value, as in the preceding example. If you try to use an uninitialized primitive in your code, you’ll get a compiler error:

Compiling produces output something like this:

To correct our code, we must give the integer year a value. In this updated example, we declare it on a separate line, which is perfectly valid:

Notice in the preceding example we declared an integer called day that never gets initialized, yet the code compiles and runs fine. Legally, you can declare a local variable without initializing it as long as you don’t use the variable—but, let’s face it, if you declared it, you probably had a reason (although we have heard of programmers declaring random local variables just for sport, to see if they can figure out how and why they’re being used).

The compiler can’t always tell whether a local variable has been initialized before use. For example, if you initialize within a logically conditional block (in other words, a code block that may not run, such as an if block or for loop without a literal value of true or false in the test), the compiler knows that the initialization might not happen and can produce an error. The following code upsets the compiler:

The compiler will produce an error something like this:

Because of the compiler-can’t-tell-for-certain problem, you will sometimes need to initialize your variable outside the conditional block, just to make the compiler happy. You know why that’s important if you’ve seen the bumper sticker, “When the compiler’s not happy, ain’t nobody happy.”

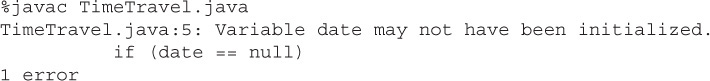

Objects references, too, behave differently when declared within a method rather than as instance variables. With instance variable object references, you can get away with leaving an object reference uninitialized, as long as the code checks to make sure the reference isn’t null before using it. Remember, to the compiler, null is a value. You can’t use the dot operator on a null reference, because there is no object at the other end of it, but a null reference is not the same as an uninitialized reference. Locally declared references can’t get away with checking for null before use, unless you explicitly initialize the local variable to null. The compiler will complain about the following code:

Compiling the code results in an error similar to the following:

Instance variable references are always given a default value of null, until they are explicitly initialized to something else. But local references are not given a default value; in other words, they aren’t null. If you don’t initialize a local reference variable, then by default, its value is—well that’s the whole point: it doesn’t have any value at all! So we’ll make this simple: Just set the darn thing to null explicitly, until you’re ready to initialize it to something else. The following local variable will compile properly:

Just like any other object reference, array references declared within a method must be assigned a value before use. That just means you must declare and construct the array. You do not, however, need to explicitly initialize the elements of an array. We’ve said it before, but it’s important enough to repeat: Array elements are given their default values (0, false, null, ‘\u0000’, and so on) regardless of whether the array is declared as an instance or local variable. The array object itself, however, will not be initialized if it’s declared locally. In other words, you must explicitly initialize an array reference if it’s declared and used within a method, but at the moment you construct an array object, all of its elements are assigned their default values.

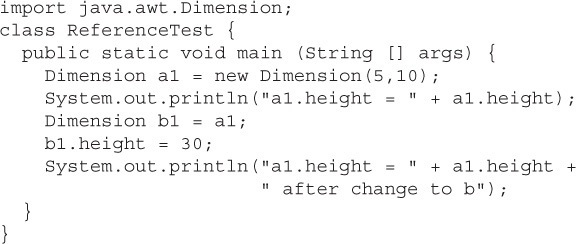

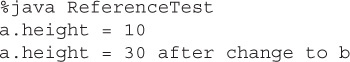

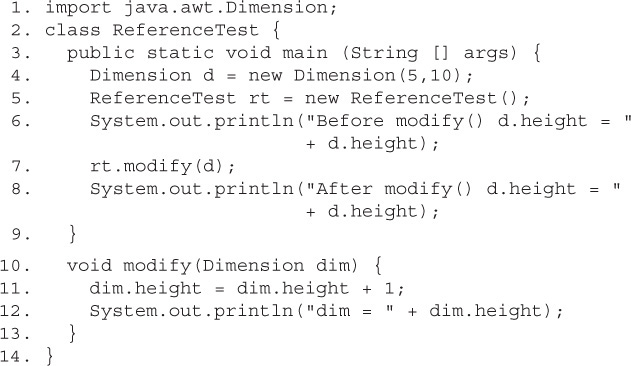

With primitive variables, an assignment of one variable to another means the contents (bit pattern) of one variable are copied into another. Object reference variables work exactly the same way. The contents of a reference variable are a bit pattern, so if you assign reference variable a1 to reference variable b1, the bit pattern in a1 is copied and the new copy is placed into b1. (Some people have created a game around counting how many times we use the word copy in this chapter…this copy concept is a biggie!) If we assign an existing instance of an object to a new reference variable, then two reference variables will hold the same bit pattern—a bit pattern referring to a specific object on the heap. Look at the following code:

In the preceding example, a Dimension object a1 is declared and initialized with a width of 5 and a height of 10. Next, Dimension b1 is declared and assigned the value of a1. At this point, both variables (a1 and b1) hold identical values, because the contents of a1 were copied into b1. There is still only one Dimension object—the one that both a1 and b1 refer to. Finally, the height property is changed using the b1 reference. Now think for a minute: is this going to change the height property of a1 as well? Let’s see what the output will be:

From this output, we can conclude that both variables refer to the same instance of the Dimension object. When we made a change to b1, the height property was also changed for a1.

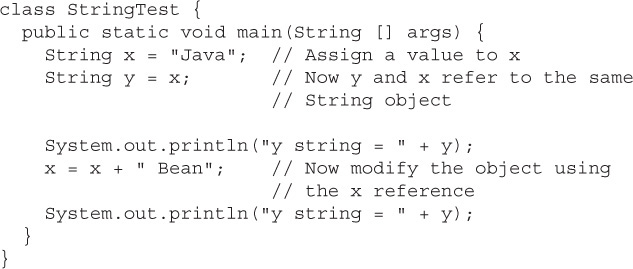

One exception to the way object references are assigned is String. In Java, String objects are given special treatment. For one thing, String objects are immutable; you can’t change the value of a String object (lots more on this concept in Chapter 5). But it sure looks as though you can. Examine the following code:

You might think String y will contain the characters Java Bean after the variable x is changed, because Strings are objects. Let’s see what the output is:

As you can see, even though y is a reference variable to the same object that x refers to, when we change x, it doesn’t change y! For any other object type, where two references refer to the same object, if either reference is used to modify the object, both references will see the change because there is still only a single object. But any time we make any changes at all to a String, the VM will update the reference variable to refer to a different object. The different object might be a new object, or it might not be, but it will definitely be a different object. The reason we can’t say for sure whether a new object is created is because of the String constant pool, which we’ll cover in Chapter 5.

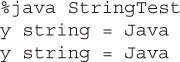

You need to understand what happens when you use a String reference variable to modify a string:

A new string is created (or a matching

A new string is created (or a matching String is found in the String pool), leaving the original String object untouched.

The reference used to modify the

The reference used to modify the String (or rather, make a new String by modifying a copy of the original) is then assigned the brand new String object.

So when you say,

you haven’t changed the original String object created on line 1. When line 2 completes, both t and s reference the same String object. But when line 3 runs, rather than modifying the object referred to by t and s (which is the one and only String object up to this point), a brand new String object is created. And then it’s abandoned. Because the new String isn’t assigned to a String variable, the newly created String (which holds the string “FRED”) is toast. So although two String objects were created in the preceding code, only one is actually referenced, and both t and s refer to it. The behavior of Strings is extremely important in the exam, so we’ll cover it in much more detail in Chapter 5.

6.8 Determine the effect upon object references and primitive values when they are passed into methods that change the values.

Methods can be declared to take primitives and/or object references. You need to know how (or if) the caller’s variable can be affected by the called method. The difference between object reference and primitive variables, when passed into methods, is huge and important. To understand this section, you’ll need to be comfortable with the information covered in the “Literals, Assignments, and Variables” section in the early part of this chapter.

When you pass an object variable into a method, you must keep in mind that you’re passing the object reference, and not the actual object itself. Remember that a reference variable holds bits that represent (to the underlying VM) a way to get to a specific object in memory (on the heap). More importantly, you must remember that you aren’t even passing the actual reference variable, but rather a copy of the reference variable. A copy of a variable means you get a copy of the bits in that variable, so when you pass a reference variable, you’re passing a copy of the bits representing how to get to a specific object. In other words, both the caller and the called method will now have identical copies of the reference; thus, both will refer to the same exact (not a copy) object on the heap.

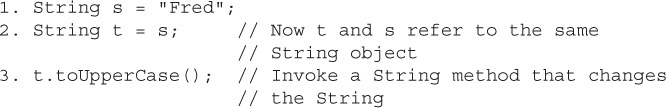

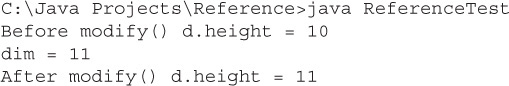

For this example, we’ll use the Dimension class from the java.awt package:

When we run this class, we can see that the modify() method was indeed able to modify the original (and only) Dimension object created on line 4.

Notice when the Dimension object on line 4 is passed to the modify() method, any changes to the object that occur inside the method are being made to the object whose reference was passed. In the preceding example, reference variables d and dim both point to the same object.

If Java passes objects by passing the reference variable instead, does that mean Java uses pass-by-reference for objects? Not exactly, although you’ll often hear and read that it does. Java is actually pass-by-value for all variables running within a single VM. Pass-by-value means pass-by-variable-value. And that means pass-by-copy-of-the-variable! (There’s that word copy again!)

It makes no difference if you’re passing primitive or reference variables; you are always passing a copy of the bits in the variable. So for a primitive variable, you’re passing a copy of the bits representing the value. For example, if you pass an int variable with the value of 3, you’re passing a copy of the bits representing 3. The called method then gets its own copy of the value to do with it what it likes.

And if you’re passing an object reference variable, you’re passing a copy of the bits representing the reference to an object. The called method then gets its own copy of the reference variable to do with it what it likes. But because two identical reference variables refer to the exact same object, if the called method modifies the object (by invoking setter methods, for example), the caller will see that the object the caller’s original variable refers to has also been changed. In the next section, we’ll look at how the picture changes when we’re talking about primitives.

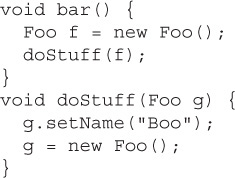

The bottom line on pass-by-value: The called method can’t change the caller’s variable, although for object reference variables, the called method can change the object the variable referred to. What’s the difference between changing the variable and changing the object? For object references, it means the called method can’t reassign the caller’s original reference variable and make it refer to a different object or null. For example, in the following code fragment,

reassigning g does not reassign f! At the end of the bar() method, two Foo objects have been created: one referenced by the local variable f and one referenced by the local (argument) variable g. Because the doStuff() method has a copy of the reference variable, it has a way to get to the original Foo object, for instance to call the setName() method. But the doStuff() method does not have a way to get to the f reference variable. So doStuff() can change values within the object f refers to, but doStuff() can’t change the actual contents (bit pattern) of f. In other words, doStuff() can change the state of the object that f refers to, but it can’t make f refer to a different object!

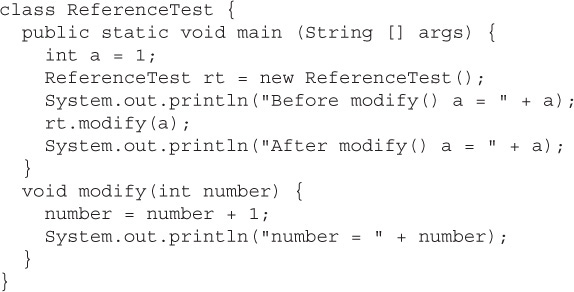

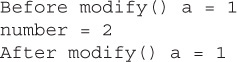

Let’s look at what happens when a primitive variable is passed to a method:

In this simple program, the variable a is passed to a method called modify(), which increments the variable by 1. The resulting output looks like this:

Notice that a did not change after it was passed to the method. Remember, it was a copy of a that was passed to the method. When a primitive variable is passed to a method, it is passed by value, which means pass-by-copy-of-the-bits-in-the-variable.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

FROM THE CLASSROOM

2.4 Explain an object’s lifecycle.

As of Spring 2014, the official exam objectives don’t use the phrases “garbage collection” or “memory management.” These two concepts are implied when the objective uses the phrase “object’s lifecycle.”

This is the section you’ve been waiting for! It’s finally time to dig into the wonderful world of memory management and garbage collection.

Memory management is a crucial element in many types of applications. Consider a program that reads in large amounts of data, say from somewhere else on a network, and then writes that data into a database on a hard drive. A typical design would be to read the data into some sort of collection in memory, perform some operations on the data, and then write the data into the database. After the data is written into the database, the collection that stored the data temporarily must be emptied of old data or deleted and re-created before processing the next batch. This operation might be performed thousands of times, and in languages like C or C++ that do not offer automatic garbage collection, a small flaw in the logic that manually empties or deletes the collection data structures can allow small amounts of memory to be improperly reclaimed or lost. Forever. These small losses are called memory leaks, and over many thousands of iterations they can make enough memory inaccessible that programs will eventually crash. Creating code that performs manual memory management cleanly and thoroughly is a nontrivial and complex task, and while estimates vary, it is arguable that manual memory management can double the development effort for a complex program.

Java’s garbage collector provides an automatic solution to memory management. In most cases it frees you from having to add any memory management logic to your application. The downside to automatic garbage collection is that you can’t completely control when it runs and when it doesn’t.

Let’s look at what we mean when we talk about garbage collection in the land of Java. From the 30,000 ft. level, garbage collection is the phrase used to describe automatic memory management in Java. Whenever a software program executes (in Java, C, C++, Lisp, Ruby, and so on), it uses memory in several different ways. We’re not going to get into Computer Science 101 here, but it’s typical for memory to be used to create a stack, a heap, in Java’s case constant pools and method areas. The heap is that part of memory where Java objects live, and it’s the one and only part of memory that is in any way involved in the garbage collection process.

A heap is a heap is a heap. For the exam, it’s important that you know that you can call it the heap, you can call it the garbage collectible heap, or you can call it Johnson, but there is one and only one heap.

So, all of garbage collection revolves around making sure that the heap has as much free space as possible. For the purpose of the exam, what this boils down to is deleting any objects that are no longer reachable by the Java program running. We’ll talk more about what “reachable” means in a minute, but let’s drill this point in. When the garbage collector runs, its purpose is to find and delete objects that cannot be reached. If you think of a Java program as being in a constant cycle of creating the objects it needs (which occupy space on the heap), and then discarding them when they’re no longer needed, creating new objects, discarding them, and so on, the missing piece of the puzzle is the garbage collector. When it runs, it looks for those discarded objects and deletes them from memory so that the cycle of using memory and releasing it can continue. Ah, the great circle of life.

The garbage collector is under the control of the JVM; JVM decides when to run the garbage collector. From within your Java program you can ask the JVM to run the garbage collector, but there are no guarantees, under any circumstances, that the JVM will comply. Left to its own devices, the JVM will typically run the garbage collector when it senses that memory is running low. Experience indicates that when your Java program makes a request for garbage collection, the JVM will usually grant your request in short order, but there are no guarantees. Just when you think you can count on it, the JVM will decide to ignore your request.

You just can’t be sure. You might hear that the garbage collector uses a mark and sweep algorithm, and for any given Java implementation that might be true, but the Java specification doesn’t guarantee any particular implementation. You might hear that the garbage collector uses reference counting; once again maybe yes, maybe no. The important concept for you to understand for the exam is, When does an object become eligible for garbage collection? To answer this question fully, we have to jump ahead a little bit and talk about threads. (See Chapter 13 for the real scoop on threads.)

In a nutshell, every Java program has from one to many threads. Each thread has its own little execution stack. Normally, you (the programmer) cause at least one thread to run in a Java program, the one with the main() method at the bottom of the stack. However, as you’ll learn in excruciating detail in Chapter 13, there are many really cool reasons to launch additional threads from your initial thread. In addition to having its own little execution stack, each thread has its own lifecycle. For now, all you need to know is that threads can be alive or dead.

With this background information, we can now say with stunning clarity and resolve that an object is eligible for garbage collection when no live thread can access it. (Note: Due to the vagaries of the String constant pool, the exam focuses its garbage collection questions on non-String objects, and so our garbage collection discussions apply to only non-String objects too.)

Based on that definition, the garbage collector performs some magical, unknown operations, and when it discovers an object that can’t be reached by any live thread, it will consider that object as eligible for deletion, and it might even delete it at some point. (You guessed it: it also might never delete it.) When we talk about reaching an object, we’re really talking about having a reachable reference variable that refers to the object in question. If our Java program has a reference variable that refers to an object, and that reference variable is available to a live thread, then that object is considered reachable. We’ll talk more about how objects can become unreachable in the following section.

Can a Java application run out of memory? Yes. The garbage collection system attempts to remove objects from memory when they are not used. However, if you maintain too many live objects (objects referenced from other live objects), the system can run out of memory. Garbage collection cannot ensure that there is enough memory, only that the memory that is available will be managed as efficiently as possible.

In the preceding section, you learned the theories behind Java garbage collection. In this section, we show how to make objects eligible for garbage collection using actual code. We also discuss how to attempt to force garbage collection if it is necessary, and how you can perform additional cleanup on objects before they are removed from memory.

As we discussed earlier, an object becomes eligible for garbage collection when there are no more reachable references to it. Obviously, if there are no reachable references, it doesn’t matter what happens to the object. For our purposes it is just floating in space, unused, inaccessible, and no longer needed.

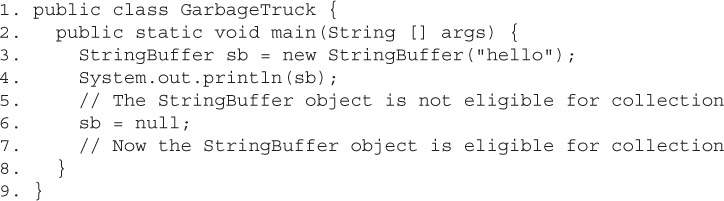

The first way to remove a reference to an object is to set the reference variable that refers to the object to null. Examine the following code:

The StringBuffer object with the value hello is assigned to the reference variable sb in the third line. To make the object eligible (for garbage collection), we set the reference variable sb to null, which removes the single reference that existed to the StringBuffer object. Once line 6 has run, our happy little hello StringBuffer object is doomed, eligible for garbage collection.

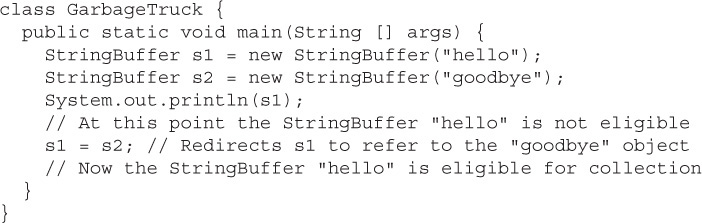

We can also decouple a reference variable from an object by setting the reference variable to refer to another object. Examine the following code:

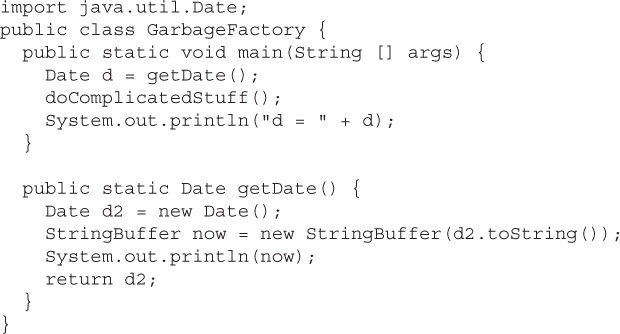

Objects that are created in a method also need to be considered. When a method is invoked, any local variables created exist only for the duration of the method. Once the method has returned, the objects created in the method are eligible for garbage collection. There is an obvious exception, however. If an object is returned from the method, its reference might be assigned to a reference variable in the method that called it; hence, it will not be eligible for collection. Examine the following code:

In the preceding example, we created a method called getDate() that returns a Date object. This method creates two objects: a Date and a StringBuffer containing the date information. Since the method returns a reference to the Date object and this reference is assigned to a local variable, it will not be eligible for collection even after the getDate() method has completed. The StringBuffer object, though, will be eligible, even though we didn’t explicitly set the now variable to null.

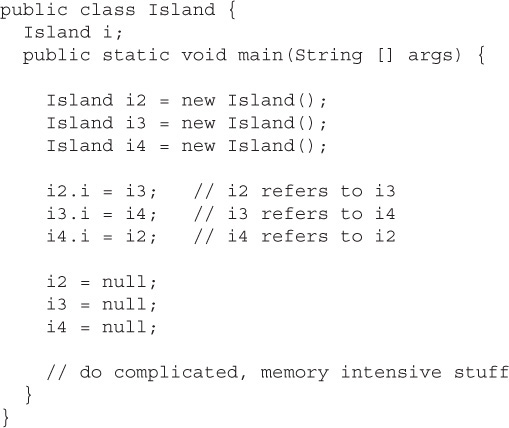

There is another way in which objects can become eligible for garbage collection, even if they still have valid references! We call this scenario “islands of isolation.”

A simple example is a class that has an instance variable that is a reference variable to another instance of the same class. Now imagine that two such instances exist and that they refer to each other. If all other references to these two objects are removed, then even though each object still has a valid reference, there will be no way for any live thread to access either object. When the garbage collector runs, it can usually discover any such islands of objects and remove them. As you can imagine, such islands can become quite large, theoretically containing hundreds of objects. Examine the following code:

When the code reaches // do complicated, the three Island objects (previously known as i2, i3, and i4) have instance variables so that they refer to each other, but their links to the outside world (i2, i3, and i4) have been nulled. These three objects are eligible for garbage collection.

This covers everything you will need to know about making objects eligible for garbage collection. Study Figure 3-2 to reinforce the concepts of objects without references and islands of isolation.

FIGURE 3-2 Island objects eligible for garbage collection

The first thing that we should mention here is that, contrary to this section’s title, garbage collection cannot be forced. However, Java provides some methods that allow you to request that the JVM perform garbage collection.

Note: As of the Java 6 exam, the topic of using System.gc() has been removed from the exam. The garbage collector has evolved to such an advanced state that it’s recommended that you never invoke System.gc() in your code—leave it to the JVM. We are leaving this section in the book in case you’re studying for the OCP 5 exam.

In reality, it is possible only to suggest to the JVM that it perform garbage collection. However, there are no guarantees the JVM will actually remove all of the unused objects from memory (even if garbage collection is run). It is essential that you understand this concept for the exam.

The garbage collection routines that Java provides are members of the Runtime class. The Runtime class is a special class that has a single object (a Singleton) for each main program. The Runtime object provides a mechanism for communicating directly with the virtual machine. To get the Runtime instance, you can use the method Runtime.getRuntime(), which returns the Singleton. Once you have the Singleton, you can invoke the garbage collector using the gc() method. Alternatively, you can call the same method on the System class, which has static methods that can do the work of obtaining the Singleton for you. The simplest way to ask for garbage collection (remember—just a request) is

Theoretically, after calling System.gc(), you will have as much free memory as possible. We say “theoretically” because this routine does not always work that way. First, your JVM may not have implemented this routine; the language specification allows this routine to do nothing at all. Second, another thread (see Chapter 13) might grab lots of memory right after you run the garbage collector.

This is not to say that System.gc() is a useless method—it’s much better than nothing. You just can’t rely on System.gc() to free up enough memory so that you don’t have to worry about running out of memory. The Certification Exam is interested in guaranteed behavior, not probable behavior.

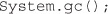

Now that you are somewhat familiar with how this works, let’s do a little experiment to see the effects of garbage collection. The following program lets us know how much total memory the JVM has available to it and how much free memory it has. It then creates 10,000 Date objects. After this, it tells us how much memory is left and then calls the garbage collector (which, if it decides to run, should halt the program until all unused objects are removed). The final free memory result should indicate whether it has run. Let’s look at the program:

Now, let’s run the program and check the results:

As you can see, the JVM actually did decide to garbage collect (that is, delete) the eligible objects. In the preceding example, we suggested that the JVM to perform garbage collection with 458,048 bytes of memory remaining, and it honored our request. This program has only one user thread running, so there was nothing else going on when we called rt.gc(). Keep in mind that the behavior when gc() is called may be different for different JVMs, so there is no guarantee that the unused objects will be removed from memory. About the only thing you can guarantee is that if you are running very low on memory, the garbage collector will run before it throws an OutOfMemoryException.

EXERCISE 3-2

Garbage Collection Experiment

Try changing the CheckGC program by putting lines 13 and 14 inside a loop. You might see that not all memory is released on any given run of the GC.

Java provides a mechanism that lets you run some code just before your object is deleted by the garbage collector. This code is located in a method named finalize() that all classes inherit from class Object. On the surface, this sounds like a great idea; maybe your object opened up some resources, and you’d like to close them before your object is deleted. The problem is that, as you may have gathered by now, you can never count on the garbage collector to delete an object. So, any code that you put into your class’s overridden finalize() method is not guaranteed to run. Because the finalize() method for any given object might run, but you can’t count on it, don’t put any essential code into your finalize() method. In fact, we recommend that in general you don’t override finalize() at all.

There are a couple of concepts concerning finalize() that you need to remember:

For any given object,

For any given object, finalize() will be called only once (at most) by the garbage collector.

Calling

Calling finalize() can actually result in saving an object from deletion.

Let’s look into these statements a little further. First of all, remember that any code you can put into a normal method you can put into finalize(). For example, in the finalize() method you could write code that passes a reference to the object in question back to another object, effectively ineligible-izing the object for garbage collection. If at some point later on this same object becomes eligible for garbage collection again, the garbage collector can still process the object and delete it. The garbage collector, however, will remember that, for this object, finalize() already ran, and it will not run finalize() again.

This chapter covered a wide range of topics. Don’t worry if you have to review some of these topics as you get into later chapters. This chapter includes a lot of foundational stuff that will come into play later.

We started the chapter by reviewing the stack and the heap; remember that local variables live on the stack and instance variables live with their objects on the heap.

We reviewed legal literals for primitives and Strings, and then we discussed the basics of assigning values to primitives and reference variables, and the rules for casting primitives.

Next we discussed the concept of scope, or “How long will this variable live?” Remember the four basic scopes, in order of lessening life span: static, instance, local, and block.

We covered the implications of using uninitialized variables, and the importance of the fact that local variables MUST be assigned a value explicitly. We talked about some of the tricky aspects of assigning one reference variable to another and some of the finer points of passing variables into methods, including a discussion of “shadowing.”

Finally, we dove into garbage collection, Java’s automatic memory management feature. We learned that the heap is where objects live and where all the cool garbage collection activity takes place. We learned that in the end, the JVM will perform garbage collection whenever it wants to. You (the programmer) can request a garbage collection run, but you can’t force it. We talked about garbage collection only applying to objects that are eligible, and that eligible means “inaccessible from any live thread.” Finally, we discussed the rarely useful finalize() method and what you’ll have to know about it for the exam. All in all, this was one fascinating chapter.

TWO-MINUTE DRILL

TWO-MINUTE DRILLHere are some of the key points from this chapter.

Local variables (method variables) live on the stack.

Local variables (method variables) live on the stack.

Objects and their instance variables live on the heap.

Objects and their instance variables live on the heap.

Integer literals can be binary, decimal, octal (such as

Integer literals can be binary, decimal, octal (such as 013), or hexadecimal (such as 0x3d).

Literals for

Literals for longs end in L or l.

Float literals end in

Float literals end in F or f, and double literals end in a digit or D or d.

The

The boolean literals are true and false.

Literals for

Literals for chars are a single character inside single quotes: ‘d’.

Scope refers to the lifetime of a variable.

Scope refers to the lifetime of a variable.

There are four basic scopes:

There are four basic scopes:

Static variables live basically as long as their class lives.

Static variables live basically as long as their class lives.

Instance variables live as long as their object lives.

Instance variables live as long as their object lives.

Local variables live as long as their method is on the stack; however, if their method invokes another method, they are temporarily unavailable.

Local variables live as long as their method is on the stack; however, if their method invokes another method, they are temporarily unavailable.

Block variables (for example, in a

Block variables (for example, in a for or an if) live until the block completes.

Literal integers are implicitly

Literal integers are implicitly ints.

Integer expressions always result in an

Integer expressions always result in an int-sized result, never smaller.

Floating-point numbers are implicitly doubles (64 bits).

Floating-point numbers are implicitly doubles (64 bits).

Narrowing a primitive truncates the high order bits.

Narrowing a primitive truncates the high order bits.

Compound assignments (such as

Compound assignments (such as +=) perform an automatic cast.

A reference variable holds the bits that are used to refer to an object.

A reference variable holds the bits that are used to refer to an object.

Reference variables can refer to subclasses of the declared type but not to superclasses.

Reference variables can refer to subclasses of the declared type but not to superclasses.

When you create a new object, such as

When you create a new object, such as Button b = new Button();, the JVM does three things:

Makes a reference variable named

Makes a reference variable named b, of type Button.

Creates a new

Creates a new Button object.

Assigns the

Assigns the Button object to the reference variable b.

When an array of objects is instantiated, objects within the array are not instantiated automatically, but all the references get the default value of

When an array of objects is instantiated, objects within the array are not instantiated automatically, but all the references get the default value of null.

When an array of primitives is instantiated, elements get default values.

When an array of primitives is instantiated, elements get default values.

Instance variables are always initialized with a default value.

Instance variables are always initialized with a default value.

Local/automatic/method variables are never given a default value. If you attempt to use one before initializing it, you’ll get a compiler error.

Local/automatic/method variables are never given a default value. If you attempt to use one before initializing it, you’ll get a compiler error.

Methods can take primitives and/or object references as arguments.

Methods can take primitives and/or object references as arguments.

Method arguments are always copies.

Method arguments are always copies.

Method arguments are never actual objects (they can be references to objects).

Method arguments are never actual objects (they can be references to objects).

A primitive argument is an unattached copy of the original primitive.

A primitive argument is an unattached copy of the original primitive.

A reference argument is another copy of a reference to the original object.

A reference argument is another copy of a reference to the original object.

Shadowing occurs when two variables with different scopes share the same name. This leads to hard-to-find bugs and hard-to-answer exam questions.

Shadowing occurs when two variables with different scopes share the same name. This leads to hard-to-find bugs and hard-to-answer exam questions.

In Java, garbage collection (GC) provides automated memory management.

In Java, garbage collection (GC) provides automated memory management.

The purpose of GC is to delete objects that can’t be reached.

The purpose of GC is to delete objects that can’t be reached.

Only the JVM decides when to run the GC; you can only suggest it.

Only the JVM decides when to run the GC; you can only suggest it.

You can’t know the GC algorithm for sure.

You can’t know the GC algorithm for sure.

Objects must be considered eligible before they can be garbage collected.

Objects must be considered eligible before they can be garbage collected.

An object is eligible when no live thread can reach it.

An object is eligible when no live thread can reach it.

To reach an object, you must have a live, reachable reference to that object.

To reach an object, you must have a live, reachable reference to that object.

Java applications can run out of memory.

Java applications can run out of memory.

Islands of objects can be garbage collected, even though they refer to each other.

Islands of objects can be garbage collected, even though they refer to each other.

Request garbage collection with

Request garbage collection with System.gc(); (for OCP 5 candidates only).

The

The Class object has a finalize() method.

The

The finalize() method is guaranteed to run once and only once before the garbage collector deletes an object.

The garbage collector makes no guarantees;

The garbage collector makes no guarantees; finalize() may never run.

You can ineligible-ize an object for GC from within

You can ineligible-ize an object for GC from within finalize().

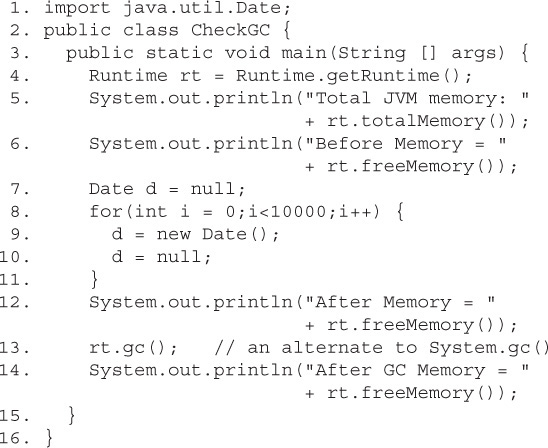

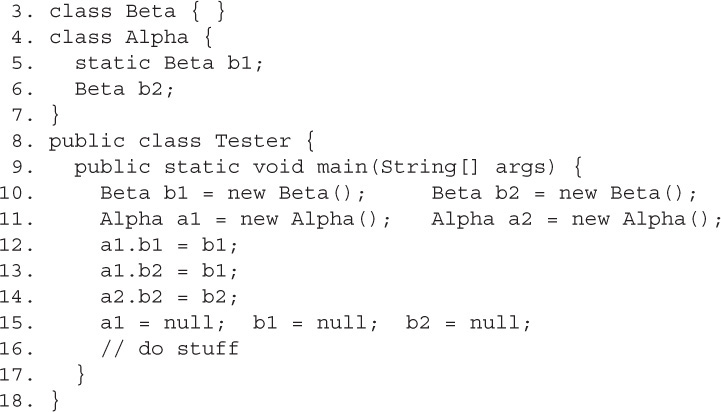

1. Given:

When // do Stuff is reached, how many objects are eligible for garbage collection?

A. 0

B. 1

C. 2

D. Compilation fails

E. It is not possible to know

F. An exception is thrown at runtime

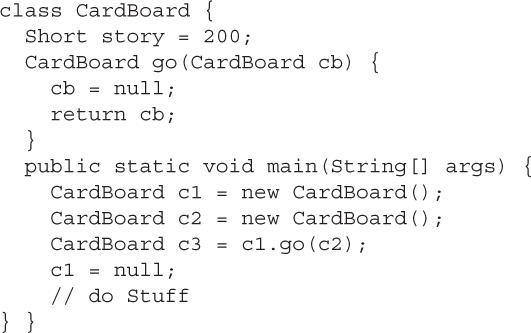

2. Given:

Which lines WILL NOT compile? (Choose all that apply.)

A. Line A

B. Line B

C. Line C

D. Line D

E. Line E

3. Given:

Which lines WILL NOT compile? (Choose all that apply.)

A. Line A

B. Line B

C. Line C

D. Line D

E. Line E

F. Line F

4. Given:

What is the result?

A. hi

B. hi hi

C. hi hi hi

D. Compilation fails

E. hi, followed by an exception

F. hi hi, followed by an exception

5. Given:

What is the result?

A. true true

B. false true

C. true false

D. false false

E. Compilation fails

F. An exception is thrown at runtime

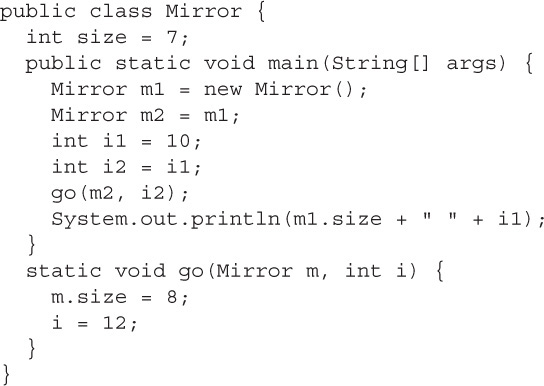

6. Given:

A. 7 10

B. 8 10

C. 7 12

D. 8 12

E. Compilation fails

F. An exception is thrown at runtime

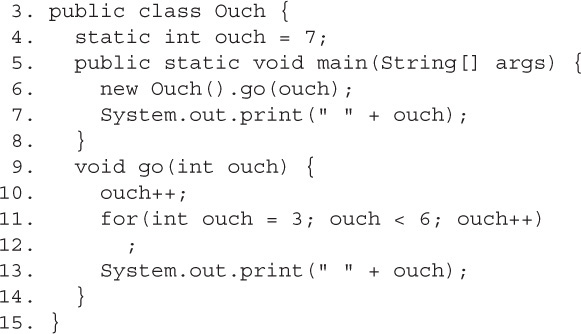

7. Given:

When execution reaches the commented line, which are true? (Choose all that apply.)

A. The output contains 1

B. The output contains 2

C. The output contains 3

D. Zero objects are eligible for garbage collection

E. One object is eligible for garbage collection

F. Two objects are eligible for garbage collection

G. Three objects are eligible for garbage collection

8. Given:

What is the result?

A. 5 7

B. 5 8

C. 8 7

D. 8 8

E. Compilation fails

F. An exception is thrown at runtime

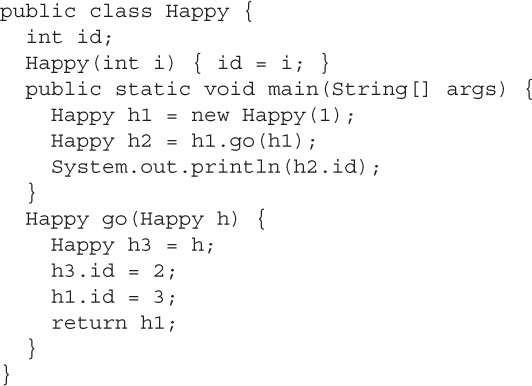

9. Given:

A. 1

B. 2

C. 3

D. Compilation fails

E. An exception is thrown at runtime

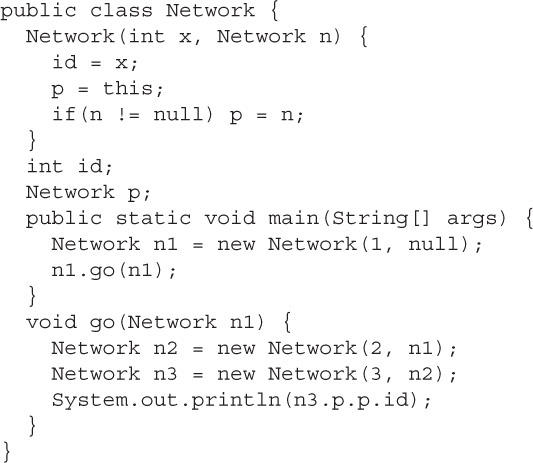

10. Given:

What is the result?

A. 1

B. 2

C. 3

D. null

E. Compilation fails

11. Given:

When line 16 is reached, how many objects will be eligible for garbage collection?

A. 0

B. 1

C. 2

D. 3

E. 4

F. 5

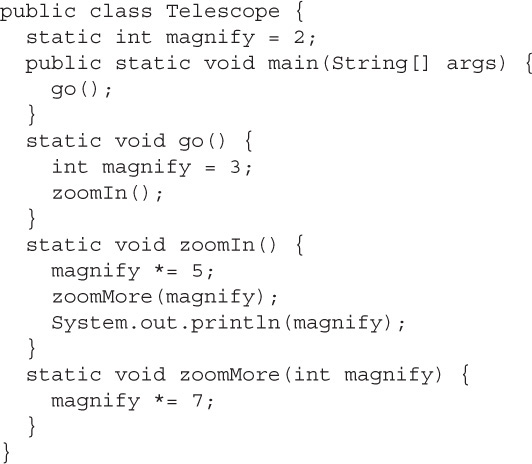

12. Given:

A. 2

B. 10

C. 15

D. 30

E. 70

F. 105

G. Compilation fails

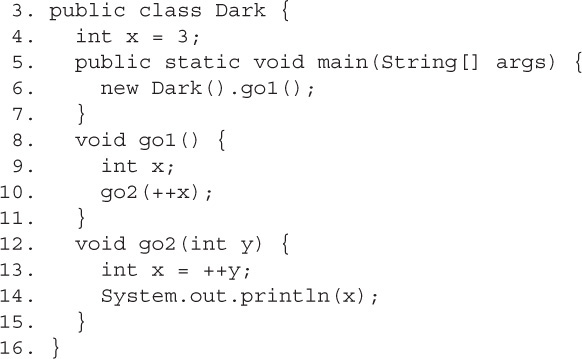

13. Given:

What is the result?

A. 2

B. 3

C. 4

D. 5

E. Compilation fails

F. An exception is thrown at runtime

1.  C is correct. Only one

C is correct. Only one CardBoard object (c1) is eligible, but it has an associated Short wrapper object that is also eligible.

A, B, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objective 2.4)

A, B, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objective 2.4)

2.  E is correct; compilation of line E fails. When a mathematical operation is performed on any primitives smaller than

E is correct; compilation of line E fails. When a mathematical operation is performed on any primitives smaller than ints, the result is automatically cast to an integer.

A, B, C, and D are all legal primitive casts. (OCA Objective 2.1)

A, B, C, and D are all legal primitive casts. (OCA Objective 2.1)

3.  C is correct; line C will NOT compile. As of Java 7, underscores can be included in numeric literals, but not at the beginning or the end.

C is correct; line C will NOT compile. As of Java 7, underscores can be included in numeric literals, but not at the beginning or the end.

A, B, D, E, and G are incorrect. A and B are legal numeric literals. D and E are examples of valid binary literals, which are also new to Java 7, and G is a valid hexadecimal literal that uses an underscore. (OCA Objective 2.1 and Upgrade Objective 1.2)

A, B, D, E, and G are incorrect. A and B are legal numeric literals. D and E are examples of valid binary literals, which are also new to Java 7, and G is a valid hexadecimal literal that uses an underscore. (OCA Objective 2.1 and Upgrade Objective 1.2)

4.  F is correct. The

F is correct. The m2 object’s m1 instance variable is never initialized, so when m5 tries to use it a NullPointerException is thrown.

A, B, C, D,and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5)

A, B, C, D,and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5)

5.  A is correct. The references

A is correct. The references f1, z, and f3 all refer to the same instance of Fizz. The final modifier assures that a reference variable cannot be referred to a different object, but final doesn’t keep the object’s state from changing.

B, C, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objective 2.2)

B, C, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objective 2.2)

6.  B is correct. In the

B is correct. In the go() method, m refers to the single Mirror instance, but the int i is a new int variable, a detached copy of i2.

A, C, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 2.2 and 2.3)

A, C, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 2.2 and 2.3)

7.  A,B, and G are correct. The constructor sets the value of

A,B, and G are correct. The constructor sets the value of id for w1 and w2. When the commented line is reached, none of the three Wind objects can be accessed, so they are eligible to be garbage collected.

C, D, E,and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1, 2.3, and 2.4)

C, D, E,and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1, 2.3, and 2.4)

8.  E is correct. The parameter declared on line 9 is valid (although ugly), but the variable name

E is correct. The parameter declared on line 9 is valid (although ugly), but the variable name ouch cannot be declared again on line 11 in the same scope as the declaration on line 9.

A, B, C, D, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1, 2.1, and 2.5)

A, B, C, D, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1, 2.1, and 2.5)

9.  D is correct. Inside the

D is correct. Inside the go() method, h1 is out of scope.

A, B, C,and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1 and 6.1)

A, B, C,and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1 and 6.1)

10.  A is correct. Three

A is correct. Three Network objects are created. The n2 object has a reference to the n1 object, and the n3 object has a reference to the n2 object. The S.O.P. can be read as, “Use the n3 object’s Network reference (the first p), to find that object’s reference (n2), and use that object’s reference (the second p) to find that object’s (n1’s) id, and print that id.”

B, C, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives, 2.2, 2.3, and 6.4)

B, C, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives, 2.2, 2.3, and 6.4)

11.  B is correct. It should be clear that there is still a reference to the object referred to by

B is correct. It should be clear that there is still a reference to the object referred to by a2, and that there is still a reference to the object referred to by a2.b2. What might be less clear is that you can still access the other Beta object through the static variable a2.b1—because it’s static.

A, C, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objective 2.4)

A, C, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objective 2.4)

12.  B is correct. In the

B is correct. In the Telescope class, there are three different variables named magnify. The go() method’s version and the zoomMore() method’s version are not used in the zoomIn() method. The zoomIn() method multiplies the class variable * 5. The result (10) is sent to zoomMore(), but what happens in zoomMore() stays in zoomMore(). The S.O.P. prints the value of zoomIn()’s magnify.

A, C, D, E, F, and G are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1 and 6.8)

A, C, D, E, F, and G are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 1.1 and 6.8)

13.  E is correct. In

E is correct. In go1() the local variable x is not initialized.

A, B, C, D,and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5)

A, B, C, D,and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCA Objectives 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5)