APPENDIX 1.1

PARAPHILIAS

DEFINITION

According to the most recent edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(4th ed., text revision;

DSM–IV–TR

; American Psychiatric Association, 2000), the primary nosological system used by mental health professionals in Canada and the United States, the diagnostic criteria for paraphilias are (a) recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors directed toward body parts or nonhuman objects; suffering or humiliation of either partner in a sexual situation; or sexual activity with a nonconsenting person and (b) that these fantasies, urges, or behaviors cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning. The

DSM–IV– TR

specifically mentioned a number of the more commonly known paraphilias (see

Table 1A.1

). Outside of Canada and the United States, the paraphilias listed in

The ICD–10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines

(World Health Organization, 1997) are generally similar in content to those listed in the

DSM–IV–TR.

TYPES OF PARAPHILIAS

Paraphilias can be broadly divided into two categories: anomalous targets and anomalous activities. In the former category, the foci of sexual thoughts, fantasies, and urges are targets other than sexually mature humans; in the latter category, the foci of sexual thoughts, fantasies, and urges are activities that are highly atypical for individuals who usually prefer sexually mature humans. A target or activity is considered to be an exclusive paraphilic preference when it is essential for someone to be sexually gratified. For example, a minority of sadomasochistic individuals who responded to a survey by Moser and Levitt (1987) indicated that they required sadomasochistic activity to be sexually gratified. An extreme example of the strength of some paraphilic interests are individuals with acrotomophilia

(a sexual interest in amputations) who have undergone surgical procedures that place them at risk of complications or even death to feel sexually satisfied (First, 2004).

A wide variety of paraphilias have been described in the clinical or research literature. Most are rare. Better known examples include

pedophilia

(pre-pubescent children),

fetishism

(nonliving objects),

sadism

(physical or psychological suffering of others), and

masochism

(being humiliated, bound, or otherwise made to suffer). It is known that paraphilic individuals are likely to exhibit multiple paraphilic behaviors, at least in clinical and criminal samples, and the etiology of paraphilias are only beginning to be understood (see

chap. 5

, this volume, for a discussion of etiological theories about pedophilia).

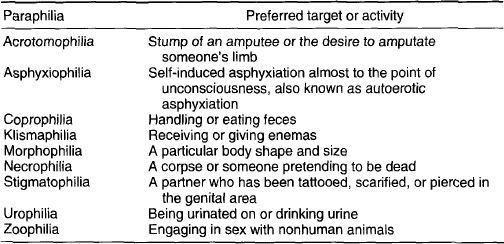

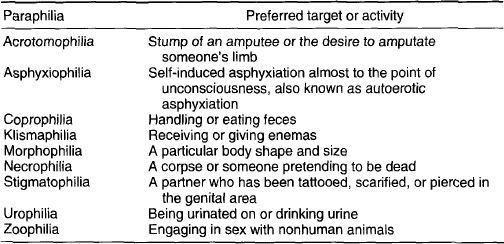

TABLE 1A.1

Examples of Clinically Identified Paraphilias

DEFINING PARAPHILIAS AS DISORDERS

One can conceptualize sexual preferences along a continuum of universality, ranging from species-typical preferences for partner age; body shape; and other physical and psychological characteristics such as intelligence, agreeableness, and kindness to culturally specific or idiosyncratic preferences for features such as ethnicity, eye color, and weight. One can also arrange sexual interests along a continuum of intensity from individuals who are selective in their preferences (e.g., a heterosexual man who sexually prefers tall, blonde, and slim women but who is still sexually aroused by other women) to extreme forms of paraphilia in which certain activities or targets are necessary for sexual gratification.

The distinction between normality and abnormality can be made on a number of dimensions, including statistical frequency, sociocultural norms, and biological pathology. These ways of defining abnormality are not independent and do not necessarily agree with each other (e.g., Ernulf, Innala, & Whitam, 1989). An illustration is the debate over the normality or abnormality of homosexuality. Statistically, individuals who are attracted to and choose same-sex partners are uncommon, with population prevalence estimates among men of approximately 2% to 5%, depending on the survey methodology being used (e.g., Sell, Wells, & Wypij, 1995). In contrast, attitudes about homosexuality appear to have shifted toward greater tolerance over the past 30 years, at least in terms of legal and social discrimination (e.g., the legalization of same-sex marriages in Canada in 2005 and the inclusion of same-sex spouses in corporate benefits programs). Finally, recent evidence suggests that neurodevelopmental perturbations can increase the likelihood of a homosexual orientation (Lalumière, Blanchard, & Zucker, 2000). Of course, whether a particular sexual preference is a disorder does not speak to whether it should be legally or socially discriminated against. The former is a scientific question, whereas the latter are political and social questions.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Paraphilic individuals are a heterogeneous group and do not consistently differ from nonparaphilic individuals in most sociodemographic or personality characteristics. Paraphilias are much more likely to be manifested by males, however, and tend to appear in adolescence or early adulthood. Individuals with paraphilias such as pedophilia, exhibitionism, or biastophilia

(a sexual preference for rape; see Lalumière et al., 2005) are more likely to be studied by researchers because these individuals are more likely to be referred to clinical or forensic settings. Also, there is greater concern about the consequences of pedophilic, exhibitionistic, or biastophilic behavior for others compared with paraphilias that do not involve other people, such as fetishism, or that take place between consenting adults, such as consensual sadistic or masochistic practices involving bondage, spanking, and discipline.

Money (1984) described a complex descriptive typology of paraphilias, and Freund (1990) proposed that certain activity paraphilias—voyeurism, exhibitionism, frotteurism, and preferential rape—reflected disturbances in the species-typical male courtship process (see

Appendix 5.2

, this volume). Money’s typology and Freund’s notion of courtship disorder are descriptive rather than explanatory. No satisfactory theory exists that explains why some targets and activities appear to be more likely than others to become the focus of paraphilias. For example, fetishistic interest in synthetic materials such as rubber or vinyl is much more likely to occur than fetishism for natural materials such as wood or feathers. Mason (1997) has made the interesting observation that fetish categories may be stable over time, but the objects in those categories change (e.g., a fetishistic interest in clothing material has been observed over at least the past century, but interests in velvet or silk in the 19th century have been displaced by interests in vinyl, rubber, or leather).

There is an extraordinary diversity in the manifestation of paraphilic interests, ranging from those that are relatively well-known in popular culture, such as

zoophilia

(bestiality) and

necrophilia

(sexual interest in corpses), to those that are obscure and seemingly implausible at first glance (e.g.,

plushophiles

, those with a fetishistic sexual interest in stuffed animals). The Internet is a fascinating forum to learn more about these myriad interests because it has allowed paraphilic individuals to associate and share sexually arousing stories, pictures, and videos in a seemingly anonymous environment. To the extent that Internet pornography is efficient in classical economic terms, the prevalence of pornographic content on the Internet, commercial and otherwise, may reflect the relative prevalence of paraphilias (Mehta, 2001; Mehta, Best, & Poon, 2002). I discuss research on child pornography and pedophilia in

chapter 3

.