3

DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO STUDYING PEDOPHILES

Research on pedophilia has been conducted primarily on men who have committed sexual offenses against children. This group has received the most empirical attention because it is of the greatest immediate public and professional concern. However, there are some disadvantages in studying pedophilia by focusing on this group. First, only about one half of the men who commit sexual offenses are pedophiles (see

Table 1.1

, this volume). As I discuss in

chapter 4

, nonpedophilic offenders against children might seek sexual gratification with a nonpreferred sexual partner for a variety of reasons, including an antisocial disregard for the risks and possible harm to the child; disinhibition by alcohol or other substances; and a lack of other sexual opportunities because of poor social skills, unattractiveness, or lack of resources.

Men who have committed sexual offenses against children have, by definition, engaged in criminal and antisocial behavior. Thus they might differ in a number of ways from pedophiles who have not committed such offenses, such as by scoring higher on measures of antisocial attitudes, beliefs, and antisocial personality traits and having a criminal history. Relatively prosocial pedophiles who have not engaged in significant antisocial and criminal behavior would not be represented in criminal justice samples.

A different selection effect may occur when studying pedophiles who have been seen in clinical settings. These pedophiles may differ from other pedophiles in having more psychological problems because they are distressed by their sexual interests in prepubescent children, receiving pressure (e.g., from a spouse) to see a mental health professional, or facing criminal charges. Pedophiles who are not distressed by their sexual interests or who are not feeling pressure from others would be much less likely to be represented in clinical samples.

It would be informative to study self-identified pedophiles who are not involved in clinical or criminal justice settings. This research is difficult to conduct because of the social, legal, and political climates that currently exist, as discussed in the Preface to this volume. People would risk a great deal if they were to be identified as pedophiles, even if they had never committed an illegal sexual act. Thus, the few studies on self-identified pedophiles (some of whom may still have been seen in clinical or correctional settings) are quite useful. At the same time, these studies of self-identified pedophiles have relied almost entirely on self-report, with the concomitant problems with regard to the reliability and validity of information that is obtained (as discussed in

chap. 2

, this volume). Research on clinical and criminal samples of pedophiles often obtains information from sources other than the self-report of the individual (e.g., family members, sexual partners, and criminal records) with regard to sexual offense history, sexual interests, and sexual behavior.

Each of these different study groups—self-identified pedophiles, pedophiles seen in clinical settings, and sex offenders with child victims seen in criminal justice settings—has its advantages and disadvantages for the study of pedophilia. Convergence in the findings from studying the different groups would increase confidence that the knowledge obtained about pedophilia is not better explained by the clinical or criminal status of the participants in the research (another approach, comparing sex offenders with other offenders and comparing pedophiles with other men, is described in

chaps. 4

and

5

, this volume). In the three sections that follow, I provide an overview of studies of self-identified pedophiles, clinical samples of pedophiles, and criminal justice samples of men who have been charged or convicted of sexual offenses involving children, seeking to identify differences and similarities in the study findings. Several questions are of particular interest: What are the features of children that pedophiles find attractive? What do we know about pedophiles who have not come into contact with clinical or criminal justice systems? What are the other options for studying pedophilia?

SELF-IDENTIFIED PEDOPHILES

In 1978 and 1979, G. D. Wilson and Cox (1983) contacted members of the Paedophile Information Exchange, a now-defunct group of advocates of adult–child sex based in London, England. With the support of the organization’s chairperson, they were able to send out questionnaires to all of the members on the organization’s mailing list, estimated to be approximately 150 to 160 individuals. G. D. Wilson and Cox received a total of 77 responses from these members. All the respondents to the survey were men between the ages of 20 and 60 years, with a modal age category of 35 to 40. Of the respondents, 71% said they preferred boys, 12% preferred girls, and 17% were attracted to both sexes. The preferred age range for boys was 12 to 14 years of age, whereas the preferred age range for girls was 8 to 10 years. Those who were sexually attracted to both boys and girls still reported younger preferred ages for girls compared with boys. This is likely explained by the pubertal status of the children, because girls experience puberty earlier than boys. Recent pediatric data suggest the average age of menarche (onset of menstruation) is around 11, whereas the average age of male puberty is around 13 (Abbassi, 1998; Herman-Giddens et al., 1997; Tanner & Davies, 1985). A few respondents indicated their preferred age was well over the expected age of puberty, that is, a preference for 16- to 18-year-olds, which would mean they were either not pedophiles or had made a mistake in filling out the questionnaire.

When asked about their fantasies about children, 39 of the 77 respondents reported having fantasies of sex with children, 22 reported romantic or caring fantasies, 18 reported having no fantasies, and 7 gave no response. The psychological and physical characteristics that the respondents found attractive in children are listed in

Tables 2.1

and

2.2

. With regard to their attitudes about sex with adults, 14 reported negative feelings about the idea (e.g., disgust, fear, or horror), 33 were indifferent, 14 reported positive feelings about it, 9 misunderstood the question as referring to their attitudes about sex with children, and 7 did not respond or their responses could not be classified by the investigators. Many of the respondents in G. D. Wilson and Cox (1983) reported that they were troubled about their pedophilia, but not all of them were. G. D. Wilson and Cox obtained the following responses to an open-ended question about their feelings regarding their sexual interest in children: happy, proud, positive (27); disturbed (21); frustrated (13); puzzled (11); sad, hopeless, depressed (5); accepting, reconciled (5); guilty, ashamed (4); and bitter or angry with society (3).

Bernard (1985) surveyed 50 members of a Dutch pedophilia advocacy group.

1

The majority were under the age of 40, with a wide range of occupations, and most (90%) were unmarried and had no children of their own. Most (96%) of the respondents preferred boys, with the peak preferred age being 12 or 13; the remaining two respondents indicated they preferred boys and girls equally. A slight majority of the respondents (56%) were currently sexually involved with a child, and approximately one half (54%) had previously been convicted of sexual behavior involving children. A minority (14%) reported having had sexual contact with more than 50 children. Twenty-four percent of the respondents indicated that they became aware of their sexual interest in young children before the age of 15, and 64% said they had had sexual contact with a child by the age of 20. Most of the respondents (90%) indicated that they did not wish to give up their sexual interest in children, even if it were possible.

More recently, Li (1991) interviewed 27 self-identified pedophiles in a small descriptive study. One third of the sample reported that they thought their sexual attraction to children was innate. More than one half mentioned specific characteristics about children that they found particularly attractive. Like the respondents in G. D. Wilson and Cox (1983), the pedophiles said they saw children as gentle, warm, generous, innocent, truthful, broadminded, affectionate, and perceptive. They also indicated that they thought relationships or sex with children was much more satisfying than relationships or sex with adults. Relationships with children were portrayed as loving, and the sexual behavior was often construed as a form of play. “Bruce” (all the interviewees were given pseudonyms by Li), stated,

My contention is that an adult can have a relationship with a child in a way that does not harm, and indeed, helps, the child. I consider myself to be an adult capable of such a relationship. Other adults might be more selfish in an adult–child encounter and end up harming the child. (Li, 1991, p. 137)

Similarly, “Nick” told Li, “Sex, to me, is a very small part, you know, in a relationship with a boy. Sex is, you know, the smallest part…. Sex isn’t the main thing, the main thing is being wanted I suppose” (p. 135). Eight of the participants defended pedophilia as culturally relative, that is, their sexual interest in children would be accepted in other places or other times. Li argued that the current repression of pedophiles guarantees that individuals who are detected by the clinical, social service, or criminal justice systems are more likely to be exploitative in pursuing their sexual interests in children, implying that those who are not exploitative either do not act on their pedophilic interests or make efforts to ensure that the children are not harmed and therefore do not report the contacts to authorities.

Riegel (2004) conducted an Internet survey and found that most of the 290 anonymous respondents reported being sexually attracted to boys. Most of the respondents also reported viewing child pornography on the Internet, and a majority of respondents thought that viewing child pornography reduced their urges to engage in sexual contact with boys; the veracity of this claim was not examined (e.g., by comparing users and nonusers of child pornography in their sexual contacts with boys). In contrast to Riegel’s findings, Wheeler (1997) surveyed 150 sex offenders with child victims and found that one third claimed they used pornography before committing a sexual offense. However, most of the offenders said they used mainstream pornography rather than child pornography. Langevin and Curnoe (2004) reported that sex offenders against children were more likely than sex offenders against adults to use pornography as part of their crimes, with one quarter of the offenders against unrelated children using pornography and one half of these individuals showing pornography to their child victims. Bourke and Hernandez (in press) reported anecdotally that the large majority of the 131 child pornography offenders they studied who admitted to contact sexual offenses reported they committed these offenses prior to seeking child pornography.

Other surveys of self-identified pedophiles have been conducted in the past 30 years, but they were not reported in English. I have had to rely on English summaries of these articles. Rouweler-Wuts (1976) interviewed 60 members of a Dutch pedophilia working group and found that the respondents who were married reported having a good emotional relationship with their adult partner but a poor sexual relationship. Pieterse (1982) distributed questionnaires among 161 members of a Dutch pedophilia working group and found that most of the respondents reported that they were interested in an ongoing friendship with children rather than a purely sexual relationship. Leonard des Sables (1976, 1977) surveyed a French group of boy-preferring pedophiles, and Lautmann (1994) interviewed 60 pedophiles for a sociological study published in German. I am not aware of surveys of members of such advocacy groups as the North American Man–Boy Love Association or active participants in Web sites that support pedophiles.

2

CLINICAL SAMPLES

Clinical samples can provide another means of studying pedophiles. However, there are few data on clinically referred men who were not known to have committed sexual offenses against children. Fedoroff, Smolewska, Selhi, Ng, and Bradford (2001) found that 26 (8%) of 316 consecutively assessed pedophiles seen at an outpatient sexology clinic were self-referred and had no known child victims. The 26 self-referred pedophiles who had no known victims were significantly less likely than the other pedophilic men who were seen at the clinic to have any kind of criminal history (although 35% still reported having a criminal record of some kind), were more likely to report a history of being sexually abused, were more likely to be virgins, and were more likely to use pornography (whether the pornography depicted children or adults was not specified). There were no group differences in biographic characteristics such as age and education, drug and alcohol use, age at first intercourse, or age of first sexual partner. Because the data reported by Fedoroff et al. were all derived from self-report, it is possible that some participants lied (e.g., pedophiles with child victims may have exaggerated their sexual involvement with adults and minimized their pornography use).

CRIMINAL SAMPLES

As mentioned, most of the empirical research on pedophilia has been conducted with samples of men charged or convicted of sexual offenses against child victims. Other criminal groups—especially users of child prostitutes and child pornography offenders—could also contribute to the understanding of pedophilia. However, relatively little research has been conducted on these other criminal groups.

Users of Child Prostitutes

Studying child prostitution could reveal something about men who are sexually interested in children and act on their interests by offering money in exchange for sexual access. Lloyd (1976) described a cheaply produced travel guide, Where the Young Ones Are

, which listed 378 places in 59 cities across 34 states where male youth involved in prostitution congregated; O’Brien (1983) claimed that the Los Angeles listings in this guide were confirmed by local police. Because prostitution is hidden and those involved are less likely to report occurrences to police or other authorities, such men are less likely to be detected than men who commit sexual offenses against children. Unfortunately, little is known about child prostitution or about the clients (for a review, see Bittle, 2002; Cusick, 2002).

Prostitution involving children under the age of 12 seems to be rare compared with prostitution involving minors between the ages of 12 and 17; surveys of North American prostitutes indicate that the average age of entry into prostitution is in adolescence or early adulthood (McClanahan, McClelland, Abram, & Teplin, 1999; Potterat, Rothenberg, Muth, Darrow, & Phillips-Plummer, 1998; Silbert & Pines, 1982). The Badgley Committee (1984) in Canada found that a minority of the 229 juvenile prostitutes they interviewed were under the age of 16. It is possible that the age of entry into prostitution may be lower in countries where child labor is more common and where poverty increases the likelihood that children will enter prostitution or be forced into it.

North American surveys of jail detainees or commercial sex workers do not necessarily include prostitution involving younger children. Inciardi (1984) reported a small qualitative study of nine 8- to 12-year-old girls who were involved in prostitution. Inciardi also noted that the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Report indicated that a small number of children under the age of 12 were apprehended for prostitution between 1971 and 1980. There is anecdotal evidence that some individuals use their children to make child pornography that is then distributed to others in exchange for other child pornography content or money. Faller (1991) found that children were allegedly used in child pornography or for prostitution in one third of the 48 families she studied in which there were multiple incest offenders.

ECPAT International (the acronym stands for “End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes”) is an organization concerned with child exploitation around the world (see

http://www.ecpat.net

), but there are few substantiated estimates on the extent of juvenile prostitution in countries with reputations for sex tourism involving minors—travel destinations in which foreign visitors can purchase sexual access to minors with less concern about arrest than in their home countries—such as Cambodia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, India, and Thailand. The prevalence estimates that are available vary widely and appear to depend more on the source of the estimate than on any reliable data collection (e.g., government agencies vs. nongovernmental agencies or social activists; see Estes & Weiner, 2005; Hughes, 2000).

3

The International Labour Office estimated that 1.8 million minors were involved in prostitution or pornography in 2000 (United Nations, 2006). The most conservative estimate I found for Thailand (which has been active in sex tourism since the 1960s and 1970s with the influx of American soldiers on leave during the American–Vietnamese conflict) was 12,000 to 18,000 minors in 2004; the percentage of these minors who were prepubertal is not known.

One half of Bernard’s (1985) sample of self-identified pedophiles surveyed in the Netherlands reported that they had traveled outside of the country to have sexual contact with a child elsewhere in Europe or in northern Africa. Estes and Weiner (2005) interviewed juveniles who had emigrated to the United States and had become involved in prostitution, often in the context of organized crime networks. On the basis of interviews with these juveniles and focus group meetings with law enforcement and social service professionals, Estes and Weiner concluded that men who paid for sex with these minors included pedophiles and transient men such as truck drivers, business travelers, and seasonal workers.

In summary, reports of men who seek sexual contacts with minors through prostitution are mostly anecdotal, with few concrete data about this phenomenon in terms of its extent, the age and pubertal status of the children who are involved, and the characteristics of the clients.

Child Pornography Offenders

In contrast to the lack of empirical research on users of child prostitutes, research on child pornography offenders is beginning to appear. Consistent with Canadian and American federal laws, child pornography

is defined in this volume as visual depictions of children that are sexually provocative or that show children engaged in sexual activity whether with other children or with adults (in the United States, the Child Pornography Prevention Act, 2002; in Canada, the Criminal Code of Canada, 1985; note that in the United States, state laws vary in their definitions of child pornography). This may be attributed to the increasing number of child pornography prosecutions over the past 5 years, though the total number is still small compared with the number of prosecutions for sexual offenses involving contact with children (Finkelhor & Ormrod, 2004; Oosterban, 2005; Wolak, Finkelhor, & Mitchell, 2005; Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2003). Wolak et al. (2005) estimated there were 1,713 arrests for Internet-related child pornography possession from July 1, 2000, to June 30, 2001, in comparison with the approximately 65,000 arrests for sexual offenses against minors recorded in 2000 according to data from the National Incident-Based Reporting System (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007).

It has been suggested that this increase in criminal justice attention is related to an increase in child pornography offending, which is attributed in turn to the emergence of the Internet as an easily accessible, affordable, and seemingly anonymous medium for distribution of child pornography (e.g., Galbreath, Berlin, & Sawyer, 2002). Prior to the advent of the Internet, men who were interested in obtaining child pornography would have to directly contact others who could sell, trade, or share materials (e.g., pictures, films, or magazines). This meant exposing oneself to the risk of being detected by police or blackmailed. With the enormous amount of traffic on the Internet, in contrast, downloading images of child pornography is unlikely to be detected unless a family member or someone else accidentally discovers the images or the individual’s Internet activities are discovered and tracked by police officers as part of undercover investigations of distribution networks. It is possible that more individuals are now involved in the collection and distribution of child pornography because the perceived risk is low and because the process can be relatively quick and easy.

Fulda (2002) argued that proactive investigations by undercover police officers posing as child pornography traders or as minors who might be interested in meeting an adult they contact through the Internet are likely to capture men with no known history of criminal behavior. In the National Juvenile Online Victimization study, 29% of the suspects were initially detected because they made contacts with undercover police investigators posing as minors online (Wolak et al., 2003). Consistent with Fulda’s hypothesis, few of these suspects had any prior criminal history. If the hypothesis that the Internet has made access to child pornography easier is correct, then there is a larger pool of child pornography offenders in the Internet era than in the past, when child pornography was distributed in nondigital media. Whereas child pornography offenders in the past may have been more antisocial individuals who were willing to take the risk of breaking the law and being detected by directly contacting others, relatively prosocial pedophiles may be more likely to be caught in Internet child pornography investigations. If this is true, then one would expect that individuals who began collecting child pornography after the advent of the Internet would be less likely to offend again than individuals who began collecting child pornography before the Internet. There have been no comparisons of child pornography offenders pre- and post-Internet to test this hypothesis.

Although the increasing number of arrests for child pornography offenses has been attributed to the greater accessibility of child pornography via the Internet, child pornography content is becoming less visible on the Internet, suggesting that criminal prosecutions are leading to greater secrecy and efforts to avoid detection. Jenkins (2001) found evidence that child pornography was openly traded in Internet newsgroups in the late 1990s. Bagley (2003) surveyed child pornography content on publicly accessible Web sites and newsgroups and found that it decreased from 1998 to 2002. He identified a total of 7,725 “indecent” images of minors in his survey, with no Web sites depicting child pornography in 2001 and 2002.

Child pornography may become less readily available, though still accessible, as more sophisticated methods are used to hide possession and distribution, including file encryption, use of services that make e-mail addresses and Internet protocol addresses anonymous, and software programs designed to obscure evidence of Internet-related activities. It is likely that the most computer-savvy child pornography offenders are not being detected by police (Jenkins, 2001; Malesky, 2005; Wolak et al., 2005). In particular, Jenkins (2001) described posts from individuals who boasted about being active in child pornography trading for decades without ever being arrested.

Pedophilia and Child Pornography

One can surmise intuitively that child pornography possession is indicative of pedophilia. There is empirical evidence to support this idea. Three quarters (74%) of Bernard’s (1985) sample of self-identified pedophiles reported they collected photographs of seminude or nude children. A majority of this group (22 of 37 respondents) said they took the photographs themselves. Quayle and Taylor (2002) interviewed 13 men who were convicted of downloading child pornography from the Internet. Many acknowledged that the material they downloaded was sexually arousing to them and matched their sexual fantasies. Although these men selected content that was most interesting to them, they claimed that they also downloaded other pornographic content because it was novel or because it completed image or video clip series.

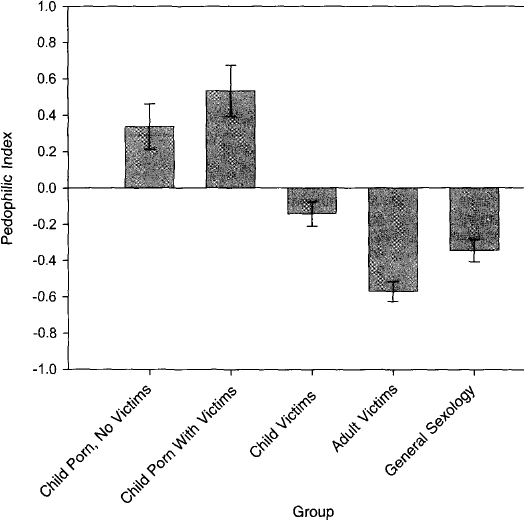

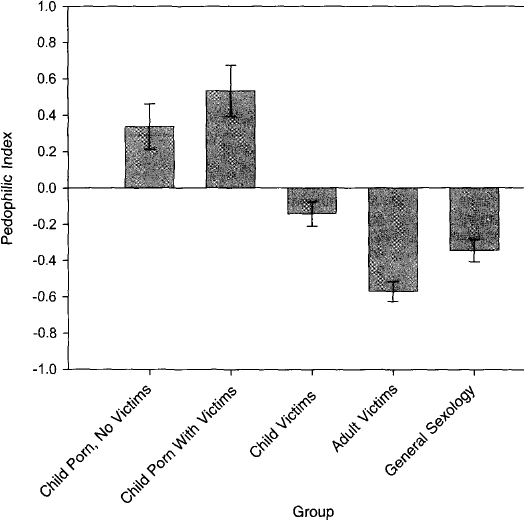

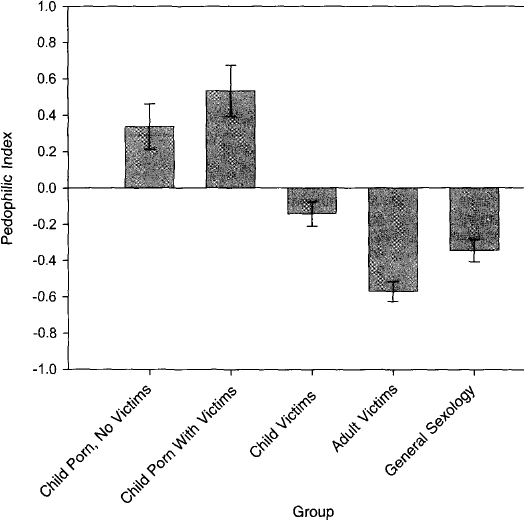

Seto, Cantor, and Blanchard (2006) found evidence for a link between child pornography possession and pedophilia in a larger study in which the phallometric test results of 100 child pornography offenders were compared with those of 178 sex offenders with child victims, 216 sex offenders with adult victims, and 191 general sexology patients. None of the men in the comparison groups had any known history of child pornography possession. As a group, the 100 child pornography offenders showed significantly greater sexual arousal to children than the offenders against children, offenders against adults, or sexology patients (see

Figure 3.1

). The 57 child pornography offenders who had no prior history of sexual offenses against children were not significantly different in their genital responses from the 43 child pornography offenders who had such a history. Overall, 61% of the child pornography offenders showed a preference for child stimuli over adult stimuli in the phallometric testing. The results suggested that child pornography offending might be a stronger diagnostic indicator of pedophilia than sexually offending against a child.

Seto et al.’s (2006) explanation for this finding was that some nonpedophilic men victimize children sexually, such as antisocial men who are willing to pursue sexual gratification with girls who show signs of sexual development but are below the legal age of consent. In contrast, people choose the kind of pornography that corresponds to their sexual interests, so relatively few nonpedophilic men would choose illegal child pornography given the abundance of legal pornography that depicts adults. Thus, an undifferentiated group of offenders against children would show less sexual arousal to children, on average, than a group of child pornography offenders.

Child Pornography and Sexual Offending Against Children

Unpublished and published data suggest that approximately one third of men who use child pornography have previously committed sexual of fenses against children (see the summary in

Table 3.1

). Raymond Smith, manager in charge of child pornography investigations at the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, reported that 34% of the 1,807 child pornography offenders arrested between January 1997 and March 2004 had a record of contact sexual offending or had engaged in an attempt to contact a child for sexual purposes (personal communication cited in Kim, 2004; see also U.S. Postal Inspection Service, 2002). Smith also stated that investigations of the 620 offenders with a history of attempting or having sexual contact with a child led to the identification of 839 child victims.

Figure 3.1

. Average pedophilic indices (standardized arousal responses to children minus standardized arousal responses to adults) for child pornography offenders without a history of sexual offenses against child victims, child pornography offenders with a history of offenses against child victims, offenders against children, offenders against adults, and general sexology patients. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the means. From “Child Pornography Offenses Are a Valid Diagnostic Indicator of Pedophilia,” by M. C. Seto, J. M. Cantor, and R. Blanchard, 2006, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115

, p. 614. Copyright 2006 by the American Psychological Association.

The proportion of child pornography offenders who have had sexual contact with children may actually be higher. Bourke and Hernandez (in press) studied 155 men convicted of child pornography offenses who were assessed and treated at a medium-security federal prison. Of these men, 40 (26%) were considered to have a known history of contact sexual offending against a child, defined as a criminal conviction for such an offense, admission by the offender, or evidence of an allegation of a contact sexual offense against a child that was investigated and determined to be substantiated by a child protective services agency. However, following treatment and participation in polygraph testing, 131 child pornography offenders (85%) admitted they had committed a contact sexual offense, with an average of more than 13 victims per offender. Those who had a known history of contact sexual offenses prior to entering treatment had twice the number of child victims than those who had no known history. In addition, a higher proportion of child pornography offenders admitted to contact sexual offenses against both boys and girls and against both prepubescent children and postpubescent minors following treatment.

TABLE 3.1

Relationship Between Child Pornography Possession and Offense History Involving Sexual Contact with Children

Child pornography offending is an international phenomenon. Child pornography traders, and the computer servers they use to communicate, can be found in different countries, and some of the largest police investigations have required the coordination of multinational investigations. Probably the largest so far was Operation Landslide, an investigation initiated by the U.S. Postal Inspection Service regarding a company run by a Texas couple who brokered online payments for commercial Web sites. At a monthly fee of $29.95, the company’s revenue was approximately $1.5 million at its peak. As a result of the police investigation, names and credit card information were obtained for thousands of subscribers from 37 American states and 60 countries. Subsequent investigations have led to arrests of suspects in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and many other countries.

A New Zealand study of 202 offenders (all but one were men) charged with having objectionable material found that most (92%) were charged for possessing child pornography (Sullivan, 2005). Some of the offenders who possessed child pornography also had other objectionable material, including depictions of sexual violence, involvement of urine or excrement in sexual acts, and bestiality. The majority of the offenders (75%) had no prior criminal history, and only a small percentage had a history of contact sexual offending (7%). Of the 16 men who had a prior sexual offense history, 12 had committed an offense against someone age 16 or younger. The majority of the offenders were students or employed in information technology, and the majority were under 30, suggesting police investigators were more likely to detect suspects who had access to and familiarity with computers. Of particular interest to those who are concerned about the potential risk to children posed by child pornography offenders, 42 of the offenders worked with or had frequent contact with children (e.g., in such jobs as coach and bus driver), and 19 were the sole caregivers of children or youths.

The largest study of child pornography offenses completed so far—the National Juvenile Online Victimization Study (NJOV)—was conducted by Wolak and her colleagues (Wolak et al., 2003, 2005). These investigators obtained data on 429 individuals arrested for possession of child pornography. Most of the NJOV offenders were men (>99%), White (91%), and older than 25 (89%) (for additional information about the characteristics of this sample, see

Table 3.2

). A minority of the 429 child pornography offenders had a history of prior arrests for nonsexual offenses (27%), sexual offenses involving a minor (11%), violent incidents (11%), or substance use problems (18%). Forty percent of the child pornography offenders were also charged with contact sexual offenses against children. Wolak et al. (2003, 2005) found that child pornography offenders who organized their collections or who distributed child pornography differed from the other offenders in being more likely to have 1,000 or more images and images of children under age 6. These results suggest that organizing or distributing child pornography is associated with pedophilia, assuming that only men who were truly interested in prepubescent children would collect 1,000 or more child pornography images or images of very young children. Both those who organized and those who distributed child pornography were also more likely to use a method to hide their child pornography, suggesting they were aware of the risks of this criminal activity and took some steps to avoid detection.

No research has been conducted to determine what effect child pornography use might have on the likelihood of subsequently having sexual contact with a child. This is an important theoretical and practical question. Theoretically, determining the extent and nature of the link between child pornography offending and subsequent sexual offending against children would shed light on the role of pedophilia as a causal factor in sexual offending against children. Practically, clinicians and the courts are increasingly being asked to estimate the risk of future sexual offending posed by child pornography offenders. Child pornography might increase (e.g., increasing the user’s desire for sexual contact with a child), decrease (e.g., by facilitating masturbation to orgasm as a substitute for sexual contact with a child), or have no effect on the likelihood of future sexual contact with a child. Experimentally demonstrated effects of mainstream adult pornography on negative attitudes about women and sex and increased aggression in the laboratory suggest that exposure to child pornography is more likely to increase attitudes tolerant of sex with children and increase the likelihood of nonsexual and sexual contacts with children (see

Appendix 3.1

). Violent child pornography may also have an additional effect on aggression against children, given the reliable, experimentally demonstrated effects of violent content in television, film, and video games on aggression (see Anderson et al., 2003, for a review).

TABLE 3.2

Selected Characteristics of National Juvenile Online Victimization Study’s Internet-Related Sex Crime Suspects

At the same time, aggregate crime data suggest that cases of child sexual abuse have declined dramatically since the early 1990s, with a 40% decline in substantiated cases of child sexual abuse during the 1990s (Finkelhor & Jones, 2004), paralleling the emergence of Internet child pornography. Similarly, analyses of aggregate crime data suggest that rates of sexual assault declined as legal restrictions on adult pornography were removed (Kutchinsky, 1991). These data have been interpreted by some authors as evidence that pornography use can have a cathartic effect, thereby reducing sexual offending. However, these are group-level data, and it has not been demonstrated that individuals who use more pornography are less likely to commit sexual offenses. The declines in sexual crimes may be better explained by a broader shift in risk taking, as Martin Lalumière and his colleagues have identified similar declines in other crime, workplace accidents, and unhealthy practices such as smoking (Lalumière, Harris, Quinsey, & Rice, 2005; Mishra & Lalumière, 2006). All of the other explanations that have been proposed to explain this decline—such as increased incarceration of pedophilic sex offenders and more sexual abuse prevention campaigns—are not sufficient to explain the magnitude of the crime drop. The decline in child sexual abuse has happened too quickly to be explained by a decline in the prevalence of pedophilia.

Internet Luring Offenders

A new category of sexual offense has been created with the advent of laws designed to prevent individuals from using the Internet to lure children into situations in which they may become victims of child pornography or contact sexual offenses. Internet luring offenders (also referred to as travelers

, e.g., Alexy, Burgess, & Baker, 2005) are different from child pornography offenders, though most child pornography offenses now involve the Internet. The concern about this group of offenses is that some pedophiles are using the Internet to meet children, either to find out information about them for a potential kidnapping (home address, name of school, and daily routines) or to arrange meetings. For example, Malesky (2005) surveyed 101 men convicted of Internet-related sexual crimes (most for child pornography offenses). Of these men, 35 corresponded with a minor they met online in the hope of establishing a sexual relationship, and 18 attempted to set up a face-to-face meeting with a minor. Such behavior can occur in the real world as well, where it is referred to as grooming

, but the Internet increases the reach of potential offenders, for example, when they contact a child in another city or even another country.

Recent research suggests that luring and traveling for sexual purposes do occur, but they typically involve adults seeking teenagers rather than young children. A survey of 1,500 youths between the ages of 10 and 17 was conducted by the Crimes Against Children Research Center in 2005, repeating a survey they first conducted in 2000 (Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2006). Approximately 1 in 7 youths had received an online sexual solicitation, which represented a decline from 2000 when approximately 1 in 5 youths had received such a solicitation. Sexual solicitations involved sexual talk, requests for personal sexual information, or requests to engage in sexual activity (e.g., invitations to engage in “cybersex”). The authors attributed this decline from 2000 to 2005 to greater awareness among young people about this issue and more cautious online behavior. Of the solicitations reported in 2005, 39% involved a solicitation by an adult; the rest involved solicitations from peers. Girls and older youths were more likely to be approached than boys or younger youths; teenage girls (ages 14 to 17) were the most likely to be solicited. Contrary to the perception that Internet luring is common, only 4% of the solicitations were deemed to be “aggressive,” meaning the person who approached the youth made attempts to meet or contact the person offline (e.g., asking to meet, telephoning, or sending mail). Only two aggressive solicitations resulted in sexual assaults, both involving teenage girls.

Walsh and Wolak (2005) found that most sexual crimes that occurred after online meetings involved teenage minors who engaged in what they viewed as a sexual or romantic relationship; such offenses have more in common with statutory sexual crimes involving teens than sexual crimes committed against children and are unlikely to involve pedophiles. Wolak, Finkelhor, and Mitchell (2004) examined data on 129 sexual offenses that had taken place as a result of online contact. Three quarters of the victims were girls between the ages of 13 and 15, and three quarters of the offenders were over the age of 25. Most of the offenders were honest about their age, so the teenage girls knew they were meeting with an adult man (Malesky, 2005, found that one half of his sample of Internet-related offenders misrepresented their ages). One half of the girls described being in love or having a close bond with the adult.

In the NJOV study, approximately one half of the adults who used the Internet to communicate with minors for a sexual purpose were family members or acquaintances such as a neighbor, friend’s relative, or family friend (Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Wolak, 2005). In other words, there was already a relationship, and the Internet was used to communicate privately with the minors. Unlike the online solicitations described previously, which resemble statutory sexual offenses, the sexual offenses committed by family members or acquaintances are more similar to sexual offenses against children that do not involve the Internet. Most of the offenders were male (99%), and the majority of victims were girls, approximately one half between the ages of 6 and 12. There was a significant difference between family members and acquaintances, with family members predominantly targeting girls (93%) below the age of 12 (82%), and acquaintances being more likely to target boys (49%) and teenagers (71%). Family members were more likely to use force or threats of force. Thus, there seems to be a distinction between offenders who were using the Internet as part of their sexual offending against a known young child and offenders who were using the Internet to solicit teenage minors. Approximately one half of the family members (49%) and a minority of the acquaintances (39%) possessed child pornography; some of these men also traded child pornography, including images of their victims. The nature of this content was not reported, but I would expect the illegal pornography possessed by acquaintances to be more likely to involve sexually maturing minors, whereas the illegal pornography possessed by family members would be more likely to involve prepubescent children, including their potential and actual victims. A small number (2%) of the family member or acquaintance offenders used the Internet to advertise children for sexual purposes.

Sex Offenders With Child Victims

Because of public and professional concerns about the sexual abuse of children, many fields have focused on sex offenders with child victims, including forensic psychiatry and psychology, criminology, sexology, law, and public policy. As suggested by the studies cited in

Table 1.1

, perhaps one half of these sex offenders against children are pedophiles. I review findings about distinguishing characteristics of these offenders that are most relevant to understanding of the etiology of pedophilia in

chapter 4

. Characteristics associated with risk to reoffend are discussed in

chapter 7

. In this section, I provide a summary of sex offender research, focusing on sexual victim characteristics, offending patterns, and the differences between pedophilic and nonpedophilic offenders. The majority of adjudicated sex offenders against children select female victims. Most offenders are known to their victims, and many have offended against related child victims; the proportion of related victims increases as victim age decreases, likely reflecting the greater access of family members to the youngest children (Snyder, 2000). As I discuss in

chapter 6

, there are meaningful differences between men who offend only against related victims and those who offend against unrelated victims. There may be an additionally meaningful distinction between those who offend against biologically versus sociolegally related children; children are at relatively greater risk of sexual abuse by steprelatives (Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990).

There is a critical distinction between pedophilic and nonpedophilic sex offenders. These two groups differ in the characteristics of their sexual offenses and the likelihood that they will reoffend. As discussed in

chapter 2

, pedophilic offenders are more likely to have boy victims, multiple victims, prepubescent victims, and unrelated victims. Concomitantly, nonpedophilic offenders are more likely to have only girl victims, single victims, pubescent or postpubescent victims, and related victims. Thus, offenders with multiple, unrelated boy victims are the most likely to be pedophiles, whereas offenders with only a single pubescent daughter, stepdaughter, or other related girl as a victim are the least likely to be pedophiles (Seto & Lalumière, 2001). The prevalence of pedophiles among sex offenders with child victims depends on the average age of the sample and the pedophilia criteria used. A few studies have found higher proportions of men showing a sexual preference for children in phallometric testing, possibly reflecting differences in the sources of those samples, methods used, and comparison groups (e.g., Chaplin, Rice, & Harris, 1995, found a high proportion of pedophiles in a sample of sex offenders against children assessed in a maximum security facility, using an optimized phallometric procedure).

Sex offenders against children vary in other respects as well. Some men groom potential victims, giving the child their attention and gifts to build trust and affection and increase their contacts, whereas other men use threats or physical force to make children comply with their sexual demands (Gebhard, Gagnon, Pomeroy, & Christenson, 1965; Kaufman et al., 1998; Lang & Frenzel, 1988; W. L. Marshall & Christie, 1981). For example, Daleiden, Kaufman, and Cooper (cited in Kaurman et al., 1998) found that 74% of their sample of adolescent sex offenders had used one or more threatening strategies to gain victim compliance. Some men see their sexual contacts with children as part of an ongoing relationship, akin to the romantic relationships that peers establish with each other (cf. Bernard, 1985; Pieterse, 1982), whereas other men simply seek sexual gratification. Some men are specialists, committing only sexual offenses against children, perhaps only against children of a similar age and gender. Other men are not so specialized, committing sexual offenses against children and adults of either gender or committing a variety of sexual offenses such as indecent exposure (exhibitionism), voyeurism, and sexual contact with children (Abel, Becker, Cunningham-Rathner, Mittelman, & Rouleau, 1988; Bradford, Boulet, & Pawlak, 1992; Heil, Ahlmeyer, & Simons, 2003; Sjöstedt, Långström, Sturidsson, & Grann, 2004). To illustrate, 28% of Abel et al.’s (1988) sample of sex offenders against children had offended against both boys and girls, and 8% of this sample had offended against both children and adults. It is incorrect to assume that a man who has only sexually offended against girls between the ages of 10 and 12 poses no risk to younger or older girls or to boys; though it is more likely that any new sexual offense would involve a girl of similar age, other children could also be victims. Finally, some sex offenders with child victims have committed only sexual crimes and otherwise live mostly prosocial lives, maintaining steady employment and stable relationships with others in their community; however, other sex offenders also have extensive histories of nonsexual offenses and other antisocial behavior. Characteristics of sexual offending against children and how they might be relevant to prevention efforts are discussed again in

chapter 8

.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND PRACTICE

The study groups described in this chapter are quite different from each other. They vary in the likelihood that members are truly pedophiles. All of the self-identified pedophiles are at one end of the spectrum; the majority of child pornography offenders are pedophiles, and perhaps half of the sex offenders against children are pedophiles. Too little is known about users of child prostitutes and clinically referred men with no known history of sexual offenses against children to estimate the prevalence of pedophilia in these groups. The study groups also vary in the likelihood that they have acted on their sexual interests in children: Some self-identified pedophiles and clinically identified pedophiles may never have had sexual contact with a child, child pornography offenders have at a minimum engaged in the illegal act of possessing visual depictions of children in sexually suggestive or explicit situations, and users of child prostitutes and sex offenders against children have had sexual contact with a child.

These differences between study groups have implications for policies and practices, which may be misdirected to the extent that study groups are confused with each other. For example, policies and practices that view all sex offenders against children as pedophiles will overestimate the risk posed by nonpedophilic sex offenders, all other things being equal, and might require nonpedophilic sex offenders to participate in treatments that do not make sense (e.g., aversive conditioning of pedophilic sexual arousal and sexdrive-reducing medication). As a second example, child pornography offenders may not pose the same risk or require the same interventions as pedophilic men who have acted on their sexual interests in children. I distinguish between pedophiles and sex offenders against children and between pedophilic and nonpedophilic sex offenders throughout this book, because these groups differ in the risk they pose to children and thus require different responses. An inadvertent consequence of conflating pedophiles and sex offenders against children is that the fear and anger that is directed at men who commit sexual crimes against children is also directed at pedophiles who have never acted on their sexual interest in children. This means pedophiles who want to refrain from committing sexual offenses cannot readily seek support from their family or close friends and are unlikely to seek professional services. In addition, as I suggest in

chapter 8

, different interventions are required for pedophilia compared with sexual offending against children.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH

Each of the study groups described in this chapter has its advantages and disadvantages for empirical research on pedophilia. Self-identified pedophiles have not been selected for psychological distress like clinical samples or for antisocial behavior like criminal samples. On the other hand, self-identified pedophiles may select themselves for impression management such that members of advocacy groups or participants in anonymous online surveys may represent themselves in an overly positive light; studies of self-identified pedophiles have relied on self-report (Bernard, 1985; Li, 1991; Riegel, 2004). Studying child pornography offenders provides an opportunity to examine a group of men who are sexually interested in children but who have not necessarily acted on such interests by having sexual contact with a child. Studying clinical and criminal samples of pedophiles can produce valuable findings because of the varied sources of information that are available, but these individuals may not be representative of pedophiles in general.

The physical characteristics of children whom pedophiles find attractive can be revealed by the nature of the child pornography that child pornography offenders collect. These characteristics can also be deduced by examining the characteristics of victims of sex offenders against children, but such victim characteristics may not fully reflect the offenders’ sexual preferences because of constraints on their access to the children they find most attractive. In contrast, child pornography offenders are less constrained because they can readily obtain and keep thousands of images from the Internet, particularly those that closely match their preferred sex and age.

All of the study groups discussed in this chapter contribute to the understanding of pedophilia. Although there is a great deal of heterogeneity within groups, and there are many differences between groups, there are also a number of similarities. It can be concluded that most pedophiles are men, consistent with the generally greater prevalence of paraphilias in men. It can also be concluded that pedophiles are more likely to be interested in boys than in girls. The features of children that are sexually attractive—as reported by self-identified pedophiles, revealed by descriptions of child pornography images, and realized in the stimuli that elicit sexual arousal in phallometric testing—appear to be the same across study groups. The preferred physical features include small body shape and size, smooth skin, and other indicators of youthfulness; preferred psychological features include gentleness, innocence, playfulness, and openness (Freund, McKnight, Langevin, & Cibiri, 1972; Taylor, Holland, & Quayle, 2001; G. D. Wilson & Cox, 1983). Finally, it can be concluded that though many pedophiles have acted on their sexual interest in children, others have not.

More research is needed on self-identified samples of pedophiles. A major challenge to this approach is the fear many pedophiles have of being identified given the current social climate. Another challenge to this approach is that mandatory reporting of child abuse or suspected child abuse in many legal jurisdictions could inhibit disclosures of undetected sexual contacts with children. Future research on pedophilia could benefit by establishing connections with pedophile communities (as G. D. Wilson and Cox [1983] did in contacting the Paedophile Information Exchange, and as Bernard [1985] and Pieterse [1982] did in contacting Dutch pedophilia groups) and by the use of governmental certificates that are available in the United States (but not Canada) to allow the confidential collection of data.

Another approach to studying pedophilia in nonclinical and noncorrectional settings is to use the Internet for participant recruitment or data collection. This approach has the strength of providing some assurance of anonymity, especially if combined with the use of Web sites that keep Internet Protocol addresses anonymous, free Web-based e-mail accounts for communication, and file encryption. Recent examples of Internet-based research include Malesky and Ennis’s (2004) analysis of posts to a chat group for individuals who were sexually interested in boys and Riegel’s (2004) online survey of self-identified boy-preferring pedophiles. The main limitation of Internet research is the possibility of self-report biases, because pedophilic respondents might alter their reports of problems to present themselves in a socially desirable manner, and anonymity precludes verifying the self-reports. For example, Riegel found that 87% of his respondents reported that their interest in mentoring a boy was equal to or more important than their interest in sex. This may be a true reflection of their interests, but this cannot be examined by investigators without speaking to the boys with whom the respondents have formed relationships. Another methodological limitation is that some respondents may not actually be pedophiles and may instead participate out of curiosity or mischief. Nonetheless, a unique opportunity exists to test hypotheses about pedophilia that are not susceptible (or less susceptible) to socially desirable responding. For example, as I discuss again in

chapter 5

, Ray Blanchard and his colleagues have demonstrated that pedophilic sex offenders are significantly more likely than nonpedophilic sex offenders to report having had a head injury resulting in unconsciousness before the age of 13 (Blanchard et al., 2002). It is unlikely that either reporting or denying a childhood head injury is socially desirable, so a future study of self-identified pedophiles could be conducted to replicate this finding.

Whatever research approach is used, comparing the findings obtained from different study groups is a productive strategy in identifying common and unique factors. Garber and Hollon (1991) have discussed how group comparisons of this kind are informative. I discuss the results of such comparisons in

chapters 4

and

5

, first on the etiology of sexual offending against children (by comparing sex offenders with other offenders and then sex offenders against children with sex offenders against adults) and then on the etiology of pedophilia (by comparing pedophiles with other men).