7

RISK ASSESSMENT

An important task for clinicians and other decision makers working with sex offenders against children is to identify those who will sexually offend again in the future (see

Appendix 7.1

for a brief discussion of definitions of recidivism, accuracy statistics, and other fundamental concepts in sex offender risk assessment research and practice). In other words, what factors distinguish men who will sexually reoffend from those who do not? Assessors are also often concerned about how quickly new offenses occur and how serious any new offenses are. These are questions of

maintenance

, having to do with the likelihood that someone already known to have committed a sexual offense against a child will commit another sexual offense. It is not the same as the question of

onset

, which has to do with the likelihood that someone will commit a sexual offense against a child in the first place. The variables that help answer the question of maintenance may not help answer the question of onset.

The assessment of risk to reoffend represents multiple, overlapping questions. These questions include (a) determining whether an offender meets legally determined criteria for dangerousness (e.g., dangerous offender hearings in Canada that can result in indeterminate prison sentences and sex offender civil commitment proceedings in the United States that allow for the commitment of sex offenders after they have served their prison sentence); (b) rank ordering offenders according to risk to reoffend to appropriately place offenders in terms of security level, supervision, and treatment; (c) determining when supervision conditions should be adjusted to safely manage offenders in the community; and (d) identifying targets for intervention to reduce the likelihood or imminence of a new offense. Much more is known about the first two questions than the latter two questions.

In this chapter, I review the literature on sex offender risk assessment, including the development of valid and accurate risk measures for the prediction of sex offender recidivism. I then discuss recent research on practical risk assessment issues, including clinical adjustments of risk estimates, combining the results of multiple risk scales, and assessment of risk for the onset of sexual offending among men who are of concern because of their sexual interest in children (child pornography offenders) or noncontact sexual offending (exhibitionists). I conclude with suggestions for future directions in risk assessment research and practice.

SEX OFFENDER RECIDIVISM

Social views and public policies about sex offenders against children appear to be driven by the belief that most will reoffend if given the opportunity. Thus, there are long sentences and powerful control mechanisms in the form of community notification, registration with police, and residency requirements (rules specifying how far sex offenders must live from public areas that may contain high concentrations of potential child victims, such as schools or parks). The reality is that many sex offenders against children do not sexually reoffend. Hanson and Bussière (1998) quantitatively reviewed 61 sex offender follow-up studies, examining the sexual recidivism rates of almost 24,000 sex offenders. They found that the average sexual recidivism rate for a total of 9,603 sex offenders against children was 13% after an average follow-up time of 5 to 6 years. Langan, Schmitt, and Durose (2003) found that 5% of 4,295 sex offenders against children were rearrested for a sexual offense within 3 years after being released from a state prison.

Focusing on studies with longer follow-up periods, Hanson, Steffy, and Gauthier (1993) followed 197 sex offenders against children for an average of 21 years after they were released from custody. During this time, 42% were convicted of a violent and/or sexual offense; 23% offended 10 or more years after their release. Prentky, Knight, and Lee (1997) followed 111 men who had sexually offended against an unrelated child and who were released from a treatment center between 1959 and 1984. Forty (36%) of these men had sexually reoffended after a follow-up period of up to 24 years; some did not reoffend until many years after being released.

These are observed recidivism rates—typically defined in terms of new arrests or new criminal charges or convictions—and underestimate the actual recidivism rate. The extent of this underestimation is unclear, depending on a complex interplay of the likelihood that a victim will report a crime to police, the likelihood that police will make an arrest, and the likelihood of successful prosecution (see

Appendix 7.1

). Hanson, Morton, and Harris (2003) have suggested that actual recidivism rates are 10% to 15% higher than observed rates. Even if the difference were double this, however, these results indicate that some sex offenders against children will not reoffend. The challenge for clinicians and policymakers is to distinguish between those who are likely to reoffend sexually and those who are not.

IDENTIFICATION OF RISK FACTORS

Quantitative reviews of several decades of sex offender follow-up research have confirmed two major dimensions of sex offender risk, which can be described as

antisociality

and

atypical sexual interests

(Doren, 2004c; Hanson & Bussière, 1998; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004; Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 1998; Quinsey, Lalumière, Rice, & Harris, 1995; Seto & Lalumière, 2000). As discussed in

chapter 4

, indicators of antisociality include prior offense history, early conduct problems, juvenile delinquency, antisocial personality features, association with delinquent peers, antisocial attitudes and beliefs, and substance abuse. The same kinds of antisociality variables have been consistently found to predict reoffending among mixed groups of offenders (Gendreau, Little, & Goggin, 1996) and among other specific groups of offenders, including sex offenders with adult victims, female offenders, juvenile offenders, and mentally disordered offenders (Bonta, Law, & Hanson, 1998; Lalumière, Harris, Quinsey, & Rice, 2005; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998). Indicators of atypical sexual interests include prior sexual offense history, phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children or to sexual coercion, and sexual victim characteristics (see

chap. 2

, this volume). Other examples of antisociality and atypical sexual interest variables are provided in

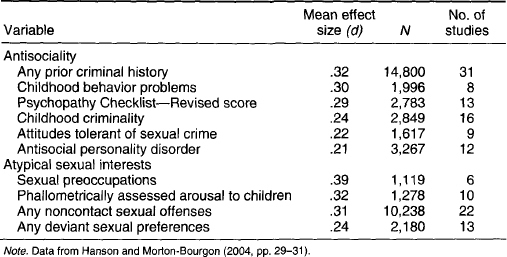

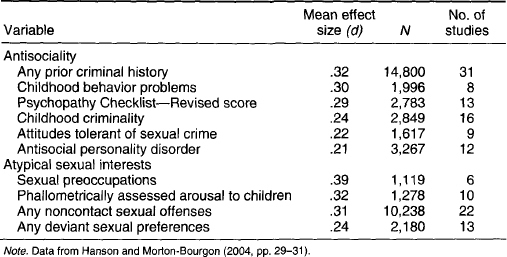

Table 7.1

.

Among identified sex offenders, both antisociality and atypical sexual interests predict sexual recidivism, and antisociality also predicts nonsexual recidivism (Hanson & Bussière, 1998; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004, 2005). In other words, sex offenders who are high on antisociality are more likely to commit another criminal offense of some kind, whether sexual or nonsexual, and those who are high on atypical sexual interest measures are more likely to commit a sexually motivated offense. Many of the diagnostic indicators of pedophilia discussed in

chapter 2

predict sexual recidivism; pedophilic indicators associated with risk include phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children, having a boy victim, and having unrelated victims. In fact, these atypical sexual interest variables are among the strongest predictors of sexual recidivism studied so far (Hanson & Bussière, 1998; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004). Adolescent and adult sex offenders who are high on both risk dimensions—antisociality and atypical sexual interests—are the most likely to reoffend sexually (Gretton, McBride, Hare, O’Shaughnessy, & Kumka, 2001; Rice & Harris, 1997; Seto, Harris, Rice, & Barbaree, 2004). Thus, offenders who are both pedophilic and psychopathic are of the greatest concern with regard to new sexual offenses.

TABLE 7.1

Indicators of Major Dimensions of Risk for Sexual Recidivism, Arranged by Magnitude of Association Within Each Dimension, for Sex Offenders

The existence of two major dimensions of risk—antisociality and atypical sexual interests—among sex offenders against children has practical and theoretical implications. It is clear from reviewing this research that risk assessment measures need to include both antisociality and atypical sexual interest variables (see Seto & Lalumière, 2000). Moreover, as discussed in

chapter 4

, theories to explain sexual offending need to incorporate both antisociality and atypical sexual interests. Finally, as I discuss in

chapter 8

, treatments that have been demonstrated to be effective for offenders in general are likely to be valuable templates for designing effective treatments for sex offenders. At the same time, pedophilic sex offenders may also require specific treatment targeting their atypical sexual interests.

DEVELOPING RISK ASSESSMENT MEASURES

How should information about risk factors be combined to make risk-related decisions such as sentencing, treatment allocation, and conditions of supervision? There are different approaches for combining risk-related information. Unstructured judgment involves the subjective appraisal and weighting of putative risk factors, followed by a statement about risk. This is a common approach in traditional clinical assessments in which a person is interviewed, file information is reviewed, and then an opinion about prognosis (risk to reoffend, in the case of offenders) is made. Structured judgment involves using a guide, such as a checklist, to focus one’s attention on specific putative risk factors. I refer to putative risk factors in discussing unstructured and structured judgments because the factors might not be empirically related to the outcome of interest or might even be negatively related so that prediction is impaired.

Empirically guided assessment involves the use of a set of risk factors that are empirically related to the outcome of interest. The combination or weighting of these empirically identified risk factors remains subjective. Finally, actuarial assessment involves the use of a set of empirically identified risk factors that are objectively scored and weighted and provide probabilistic estimates of risk based on the established empirical relationships between the individual items and the outcome of interest. Only items that independently contribute to the prediction of the outcome of interest, in combination with the other items in the set, are retained. Probabilistic estimates indicate the proportion of people with the same score (or within a range of scores) who would be expected to reoffend within a specified period of opportunity. Actuarial assessments of risk are well established in such disparate areas of practice as determining insurance premiums and predicting survival times for progressive stages of cancers. In a similar vein, the Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests described in

chapter 2

is an actuarial measure for determining the likelihood that a sex offender with child victims will show a sexual preference for children over adults when assessed phallometrically.

ACTUARIAL RISK ASSESSMENT

Unstructured or structured judgments were the typical approaches to offender risk assessment before the emergence of empirically guided and actuarial assessment scales beginning in the early 1990s. Unfortunately, the low predictive accuracies that were typically obtained using unstructured or structured clinical judgments led to much pessimism about the ability of professionals to predict future violence, including future sexual offenses (see Monahan, 1981). The myriad challenges for unstructured clinical judgment were identified decades earlier by Meehl (1954). These include attending to irrelevant risk factors because of cognitive biases such as the

representativeness heuristic

(the extent to which a factor seems to fit the prototype of a persistent sex offender)

1

or the

availability heuristic

(the extent to which a factor is salient when the judgment is made), assigning suboptimal weights to a set of empirically identified risk factors, and failing to take statistical covariation between risk factors into account. As an example of the first challenge, many practitioners have considered acceptance of personal responsibility an important risk factor that needs to be targeted in sex offender treatment, even though denial of responsibility is empirically unrelated to sexual recidivism (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004). As an example of the third challenge, both number of prior offenses and number of prior admissions to corrections are significantly related to recidivism and highly correlated with each other, but only number of prior offenses uniquely contributes to the prediction of recidivism when both variables are considered in multivariate statistical analyses (Quinsey, Harris, et al., 1998).

Actuarial risk scales have become the dominant sex offender risk assessment approach in the past 15 years. There is a large body of research demonstrating that actuarial assessments are better, on average, than unstructured clinical judgment across a wide range of assessment questions (Ægisdóttir, Spengler, & White, 2006; Grove et al., 2000). Although there has been opposition to the promulgation of actuarial risk scales in sex offender risk assessment (e.g., Litwack, 2001), these scales appear to have been generally accepted by practitioners. An information package produced for members of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, a large international organization of sex offender service providers and other professionals working in the field of sexual abuse prevention and intervention, advocated the use of actuarial risk scales when assessing adult male sex offenders (Hanson, 2000). Actuarial risk scales were recommended in a recent book on sex offender risk assessment (Doren, 2002), and an August 2004 survey of evaluators found that actuarial risk scales were used in almost all of the 17 states that have civil commitment laws (D. M. Doren, personal communication, October 6, 2004). Most important, studies examining the predictive performance of actuarial risk scales have shown they produce significantly higher accuracies than empirically guided or unstructured clinical judgments (for a review, see Hanson et al., 2003). The greater predictive accuracy provided by actuarial risk scales can translate into the prevention of many sexual offenses against children and more efficient use of limited treatment and supervision resources when decisions are made about hundreds of thousands of sex offenders.

2

Actuarial Risk Scales

Examples of actuarial risk scales used in sex offender risk assessments include the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG; G. T. Harris, Rice, & Quinsey, 1993), Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (SORAG; Quinsey, Harris, et al., 1998), Rapid Risk Assessment of Sexual Offense Recidivism (RRASOR; Hanson, 1997), and Static-99 (Hanson & Thornton, 2000). All of these scales have demonstrated good predictive validity and have been cross-validated in new samples of sex offenders by independent investigators (e.g., Barbaree, Seto, Langton, & Peacock, 2001; Langton, Barbaree, Seto, Peacock, & Harkins, 2007; Sjöstedt & Långström, 2001).

These actuarial risk scales contain many similar items because they were all empirically derived, and their developers drew from the same sex offender recidivism literature for items (for meta-analytic reviews of this literature, see Hanson & Bussière, 1998; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004). In fact, the SORAG is a modification of the VRAG, and the Static-99 includes all four RRASOR items. All of these scales have good predictive accuracy for sex offenders with child victims (Bartosh, Garby, Lewis, & Gray, 2003; G. T. Harris, Rice, et al., 2003). Because of their prominence in current sex offender risk assessment, the VRAG, SORAG, RRASOR, and Static-99 are described in more detail in the sections that follow. Further details, including how to obtain copies of these scales, are provided in

Resource B

.

Violence Risk Appraisal Guide

The VRAG was developed for use with men known to have committed a violent offense, whether sexual or nonsexual in nature, and was designed to predict violent recidivism

(defined as a new nonsexually violent offense such as an assault or a new sexual offense involving physical contact with a victim). It contains 12 items: did not live with both biological parents until age 16, elementary school maladjustment, history of alcohol problems, never married or common-law, extent of nonviolent offense history, failed on prior conditional release, young age at time of index offense, less index victim injury, did not have a female index victim, met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(3rd ed.; DSM–III;

American Psychiatric Association, 1980) criteria for any personality disorder, did not meet DSM–III

criteria for schizophrenia, and Psychopathy Checklist—Revised (PCL–R; Hare, 1991, 2003) score (G. T. Harris et al., 1993; Quinsey, Harris, et al., 1998). The item weights are based on the empirical relationship between the predictor and violent recidivism in the development sample; each point represents a difference of 5% from the base rate of violent recidivism in the development sample (31% after an average follow-up time of 7 years). For example, sex of the index offense victim is scored as −1 if the victim was female and +1 if the victim was male; this means that 26% of the offenders with a female index offense victim committed a new violent offense during the follow-up period, and 36% of the offenders with a male index offense victim did so, all other things being equal. Total VRAG scores can range from −26 to +38. Individuals can be assigned to one of nine risk categories based on their scores.

Because of the importance of psychopathy in explaining criminal behavior (see

Appendix 4.2

, this volume), the PCL–R is an important part of the VRAG, with the single biggest influence on the overall score. Offenders’ PCL–R scores are based on a review of file information and a semistructured interview when available. Offenders are assigned ratings of 0 (

absent

), 1 (

some indication

), or 2 (

present

) on each of the 20 PCL–R items, tapping characteristics such as impulsivity, irresponsibility, and callousness. The 20 items are summed to produce a total score out of 40.

Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide

The SORAG is a modification of the VRAG, with 10 items in common, and was created using a similar methodology. This scale was developed for men known to have committed a sexual offense involving physical contact with a victim and was designed to predict violent recidivism. The SORAG has 14 items: did not live with both biological parents until age 16, elementary school maladjustment, history of alcohol problems, never married or common-law, extent of nonviolent offense history, extent of violent offense history, previous sexual offense history, sex and age of index victim, failure on prior conditional release, young age at index offense, met DSM–III

criteria for any personality disorder, did not meet DSM–III

criteria for schizophrenia, phallometrically measured deviant sexual interests, and PCL–R score (Quinsey, Harris, et al., 1998). As with the VRAG, the PCL–R score is the most influential item on the SORAG. Total SORAG scores can range from −27 to +51. Individuals can be assigned to one of nine risk categories based on their scores.

The VRAG and SORAG were designed to predict violent recidivism, an outcome that includes both nonsexually violent and sexual offenses involving physical contact with a victim (sex-related offenses such as possession of child pornography, indecent exposure, or prostitution involving an adult would be excluded under this definition). Analysis of criminal justice and clinical records suggests that many apparently nonsexually violent offenses on police rap sheets are in fact sexually motivated (e.g., a charge or conviction for attempted murder might be judged to be a sexual offense after reviewing all of the available information; Rice, Harris, Lang, & Cormier, 2006). Rice et al. (2006) have therefore argued that violent recidivism is the most relevant outcome in studies of sex offender risk.

Rapid Risk Assessment for Sexual Offense Recidivism

The RRASOR was developed for men who had been convicted of at least one sexual offense and was designed to specifically predict sexual recidivism. Because of the way in which sexual recidivism is defined, some sex-related reoffenses that resulted in charges or convictions for “nonsexual” crimes (e.g., an attempted sexual offense against a child with insufficient evidence to guarantee a conviction under the relevant statute might result in a guilty plea for assault) would not be counted. The RRASOR has four items: number of prior charges or convictions for sexual offenses; age on release from prison or anticipated opportunity to reoffend in the community; any male victims; and any unrelated victims (Hanson, 1997). The item weights reflect the magnitude of each item’s independent relationship with sexual recidivism. Total scores can range from 0 to 6.

Static-99

The Static-99 was developed for men who are known to have committed at least one sexual offense and was designed to predict either violent recidivism or specifically sexual recidivism. It has 10 items, 4 of which are the same as the RRASOR items listed previously (Hanson & Thornton, 2000). The additional items are number of prior sentencing dates, had any convictions for noncontact sexual offenses, index offense of nonsexually violent nature, prior nonsexually violent offense, any stranger victims, and ever lived common-law for 2 or more years. Total scores range from 0 to 12. Individuals are assigned to one of seven risk categories based on their score (individuals with scores of 6 or more are combined into one group because of the small frequencies of offenders with such scores in the development sample).

Other Risk Scales

A number of other risk scales have been reported in the literature. There are too many to list all of them here, but better known examples include the Minnesota Sex Offender Screening Tool—Revised, Risk for Sexual Violence Protocol, and Sexual Violence Risk—20. These risk assessment measures are not reviewed here because an extensive review of sex offender risk assessment measures has been provided by Doren (2002) and by Langton (2003). There are some studies supporting the predictive validity of these scales, including Langton’s, but they do not have the same level of support as the actuarial risk scales listed previously. No actuarial risk scales have yet been developed and validated for violent or sexual recidivism among adolescent sex offenders or for female sex offenders, though some progress has been made in developing risk measures for adolescent sex offenders (Epperson, Ralston, Fowers, DeWitt, & Gore, 2005; Parks & Bard, 2006).

Which Actuarial Risk Scale Is Best?

Hanson et al. (2003) reported that the Static-99 has the largest number of published cross-validation studies and has produced the highest average

area under the curve

(AUC; an index of predictive accuracy that is now commonly reported in sex offender risk assessment research; see

Appendix 7.1

) in predicting sexual recidivism. The average Static-99 AUC was significantly higher than the average AUC obtained for the VRAG in predicting sexual recidivism but did not significantly differ from the average AUCs obtained by the SORAG or RRASOR. At the same time, Hanson and Morton-Bourgon (2004) reported that the VRAG and SORAG produced a larger average effect size across their cross-validation studies than obtained for the RRASOR or Static-99 in predicting violent recidivism. These results were obtained from a quantitative review of all available studies. It is interesting to note that studies that have directly compared actuarial risk scales have not found consistent differences in their performances in predicting violent or sexual recidivism (Barbaree et al., 2001; Dempster, 1999; Langton et al., 2007; Nunes, Firestone, Bradford, Greenberg, & Broom, 2002; Sjöstedt & Långström, 2001). An exception is a study by G. T. Harris et al. (2003) that found the VRAG and SORAG were significantly better at predicting violent recidivism than the Static-99 or RRASOR.

The most plausible explanation for the lack of consistent differences in predictive accuracy among these scales is that they have similar item content and data collection methods. Thus, it is not surprising that Kroner, Mills, and Reddon (2005) found that four new scales created using a quasi-random subset of items from four established measures associated with risk to reoffend in mixed groups of offenders (PCL–R, Level of Service Inventory—Revised, VRAG, and the General Statistical Information on Recidivism) did not differ in their predictive performances from the four original scales. The four quasi-randomly generated scales and the original four measures were all significantly and positively correlated with each other. If the similar items and method explanation is correct, then only the addition of new items pertaining to content that is not captured by existing items or collected using different methods (e.g., biometric measurements, biochemical assays, and direct observations of behavior) could add to the predictive accuracies that are currently obtained.

Static and Dynamic Risk

Actuarial risk scales exclusively or almost exclusively consist of static risk factors, defined here as historical factors that cannot change (e.g., prior criminal history and history of alcohol abuse) or highly stable factors that are very unlikely to change, if they can be modified at all (e.g., pedophilia and psychopathy). Dynamic risk factors

are defined here as changeable (e.g., antisocial attitudes and beliefs about sex with children) or temporally fluctuating (e.g., level of alcohol intoxication) factors that could, in principle, be targets of intervention.

Some practitioners and researchers have argued that sex offender risk measures need to incorporate dynamic risk factors to avoid the potential dilemma of assigning risk scores to an offender that do not change because the scores are based on static factors. Once someone is denied parole because of his or her actuarially estimated risk on a scale such as the SORAG or Static-99, nothing that individual can subsequently do—participate in treatment, obtain a firm commitment of legal employment on release, or improve family support—can change the risk score and therefore change the risk-based decision. This is both a dilemma for the offender (who may be less motivated to participate in treatment or other services because of the inability to change his or her risk score) and the clinician (who wants to increase offender motivation and participation in services through the incentive of increasing the likelihood of release on parole or an easing of supervision conditions). This dilemma has been identified by some evaluators as a justification for the clinical adjustment of actuarial estimates of risk, defined as the adjustment of actuarial risk scores or the probabilistic estimates on the basis of additional information such as completion of prescribed treatment.

Whether dynamic risk factors should be incorporated into decision making and what factors actually qualify for this designation are empirical questions and cannot be justified on the basis of the offender’s or clinician’s dilemma alone. Another potential solution that does not compromise the predictive accuracy of actuarially estimated risk is to require more extensive preparations for release based on actuarially estimated risk, so higher risk offenders must do much more to be eligible for parole than low-risk offenders. In this arrangement, a higher risk offender might have to complete treatment, obtain employment, develop stronger family support, and meet a number of other goals to be released, whereas a lower risk offender might only have to obtain stable housing and employment for release. Regardless of the extent of preparations, more caution is warranted in the management of the high-risk offender.

Perhaps part of the difficulty in conceptualizing how to integrate information about static risk factors and dynamic risk factors is that they actually address two different questions. Assessments based on static risk factors are better suited for answering the question of who is more likely to reoffend during a certain period of opportunity. Individuals with a history of alcohol abuse, for example, are more likely to reoffend than individuals without such a history. In contrast, assessments based on dynamic risk factors may be better suited for answering the question of when someone at a particular level of static risk to reoffend is more likely to do so during that period of opportunity. Thus, individuals may be more likely to reoffend when they are intoxicated than when they are sober, all other things being equal.

The likelihood that an offender will reoffend is not uniformly distributed over time. There are times when an offense is more likely and other times when it is less likely. Dynamic risk factors indicate periods of higher likelihood, that is, imminence. To illustrate this idea with a thought experiment, most sex offenders sleep some of the time; those who are awake have more opportunities to offend than those who are asleep, and so being awake can be thought of as a dynamic risk factor (though it has been suggested that some men may sexually offend while asleep!; Shapiro, Trajanovic, & Fedoroff, 2003). Statistical interactions between static and dynamic risk factors are possible such that someone with both a history of alcohol abuse and who is currently intoxicated is at greater imminent risk to reoffend than someone who is intoxicated but does not have an alcohol abuse history. At the same time, intoxication may increase the imminence of an offense among nonpsychopathic offenders but not among psychopathic offenders (see Rice & Harris, 1995).

Some promising candidates for dynamic risk factors have been identified. Such research is difficult to conduct, which may explain why knowledge about dynamic risk factors greatly lags behind knowledge about static risk factors. It is not sufficient to demonstrate that a changeable or temporally fluctuating factor, assessed at one point in time, is related to whether a new offense subsequently occurs. Because the variable is assessed at only one point in time, it becomes a static risk factor when considered at a later date. Whether someone is currently intoxicated is potentially a dynamic risk factor; whether someone consumed alcohol last week is potentially a static risk factor. To be considered a true dynamic risk factor, it is necessary to demonstrate that change on the factor is related to the timing of any offense that occurs, over and above the prediction provided by static risk factors. To illustrate this last point, association with antisocial friends might be a potential dynamic risk factor because it can be measured more than once and it can be targeted through interventions to decrease contact with antisocial friends and increase contact with prosocial friends. However, having antisocial friends may actually be a proxy for antisociality such that highly antisocial offenders tend to have many antisocial peers. Even demonstrating that change in peer groups is related to recidivism is not sufficient to demonstrate that this variable is a dynamic risk factor because it may be the case that highly antisocial offenders do not change their peer groups, whereas less antisocial offenders do. Having antisocial friends would be a dynamic risk factor only if it could be demonstrated that changing peer associations is associated with the likelihood that a new offense will occur, over and above the prediction provided by knowing whether someone had antisocial friends at the baseline assessment and knowing how they score on a measure of antisociality such as the PCL–R.

Dynamic risk assessment research with mentally disordered offenders suggests that noncompliance with staff instructions, noncompliance with treatment, and mood problems are related to the timing of new offenses (Quinsey, Coleman, Jones, & Altrows, 1997). Similar dynamic risk assessment research on sex offenders in the community suggests that compliance with supervision; ability to regulate sexual thoughts, fantasies, and urges; attitudes tolerant of sexual offending; and associating with antisocial peers distinguished sex offenders who reoffended from those who did not, even after the recidivists and nonrecidivists were matched on a set of static risk factors (Hanson & Harris, 2000).

One limitation of the studies by Hanson and Harris (2000) and Quinsey et al. (1997) was that data from recidivists and nonrecidivists were examined retrospectively; recidivists and nonrecidivists were identified and then compared on variables coded from files that were not designed for the study. These studies did not follow a sample of offenders prospectively to determine if changes on the putative dynamic risk factors were temporally linked to a new offense. More recent prospective studies suggest they do, such that increases in certain dynamic risk factors could be detected in the month prior to a new offense occurring (see A. Harris & Hanson, 2002; Quinsey, Jones, Book, & Barr, 2006). For example, new offenses tended to be preceded by an increase in scores on measures of noncompliance with treatment and supervision in the previous month.

CLINICAL ADJUSTMENTS OF ACTUARIALLY ESTIMATED RISK

A controversial question in sex offender risk assessment is whether clinical adjustments of actuarially estimated risk to reoffend are ever warranted. There are two competing positions: One suggests that clinical adjustments are sometimes justified because actuarial risk scales, no matter how wide-ranging in their content, do not include all possible risk and protective factors (Doren, 2002; Hanson, 2000). Proponents of this position also note that actuarial risk scales do not accommodate unusual circumstances, for example, if a pedophilic sex offender has a stroke and is cognitively and physically disabled as a result. It is argued that the clinician should adjust the actuarial estimate of risk in such cases, because the unusual circumstances override the actuarially estimated risk to reoffend. As mentioned earlier, some have also argued that actuarial estimates should be adjusted on the basis of information about dynamic risk factors.

The competing position refers to the substantial literature on the challenges facing unstructured judgment in formulating opinions about risk, all of which would also apply to the unstructured adjustment of actuarial estimates (see Meehl, 1954). Moreover, potential adjustment factors may already have been considered in the development of actuarial risk scales and not included because they were unrelated to the likelihood of recidivism or they did not add to the predictive accuracy provided by the items that were already selected. Clinicians who are familiar with an actuarial risk scale but not all the details of the research that contributed to its development may unknowingly consider factors that have already been examined and dropped in multivariate analyses. If a new risk factor was identified and did add to the predictive accuracy already obtained by the existing items, it could be incorporated as a new item in a revised version of the actuarial risk scale. In other words, the adjustment of actuarial risk scale results could itself be an actuarial procedure. Nonetheless, the practice of unstructured clinical adjustment of actuarial risk scales is common.

There is some evidence that additional information can add to the predictive validity of actuarial risk scales. Whether adjusting actuarial risk scores increases predictive accuracy, however, has not yet been empirically demonstrated, except for time offense free while living in the community. The developers of the VRAG initially identified factors that they thought could be considered in the adjustment of actuarial risk scores (Webster, Harris, Rice, Cormier, & Quinsey, 1994) but later advised against adjustments given the lack of empirical support for such a position (Quinsey, Harris, et al., 1998). The types of information that have shown incremental validity in some studies are listed in the sections that follow.

Treatment Behavior

Doren (2002) identified eight studies that examined the incremental validity of treatment-related behavior when added to actuarial risk scale scores; six of these eight studies examined the impact of participating in treatment. For example, McGrath, Cumming, Livingston, and Hoke (2003) found that whether an offender completed treatment added to the prediction of sexual recidivism obtained by the RRASOR or Static-99. Research on the relationship between treatment behavior and sex offender recidivism is discussed further in

Appendix 8.1

.

Offender Age

Another incremental factor that has been discussed is offender age. Barbaree, Blanchard, and Langton (2003) reported that offender age at release was a significant predictor of sexual recidivism in a sample of 468 sex offenders (293 of whom had offended against at least one child). Moreover, offender age at release added to the predictive accuracy obtained with the RRASOR, even though age at release was already represented as an item in that scale. Barbaree et al. (2003) suggested this finding might reflect an agerelated decrease in risk for offending mediated by an age-related decrease in sexual arousability and sex drive (for a review, see Doren, 2006).

Barbaree et al. (2003) addressed the alternative explanation that their cross-sectional data might reflect cohort differences in risk (e.g., highly antisocial offenders engaging in more physically risky activities and therefore dying at a younger age, resulting in a lower risk group of older offenders) rather than an effect of aging by noting that the four age groups they created did not show a systematic difference in RRASOR scores. They did not report, however, whether the offender age at release significantly added to the predictive performances of actuarial risk scales with a broader range of scores such as the SORAG or Static-99 or whether the age groups differed on these other risk scales. They also did not report how offender age at release performed when compared with offender age at the time of the index offense or offender age at the time of the first offense. The latter question is relevant because offender age at the time of the first offense, offender age at the time of the index offense, and offender age at release are all positively correlated with each other, and age at release might actually be acting as a proxy for the historical, static risk factor of offender age at the time of the first offense or offender age at the time of the index offense (G. T. Harris & Rice, 2006). If the proxy explanation is correct, then offender age at release does not reflect an age-related decrease in risk of offending.

Time Offense Free

In the revised coding rules for the Static-99, A. Harris, Phenix, Hanson, and Thornton (2003) presented a new empirically based option to adjust the probabilistic estimates on the basis of the amount of time that an offender had spent without any new major offenses (i.e., no new nonsexually violent or sexual offenses; minor offenses were not counted) while living in the community. A. Harris, Phenix, et al. suggested that the reduction could be up to one half of the probabilistic estimate if the offender had been free of major offenses for 5 to 10 years in the community. G. T. Harris and Rice (2006) also examined the impact of violent-offense-free time at risk in a study of the VRAG. They found that violent-offense-free time at risk was related to the likelihood of new violent offenses and that this information could be used to adjust actuarially estimated risk as long as an offender was not in the highest three risk categories. However, it is important to note that they recommended that this adjustment itself be actuarial. Specifically, G. T. Harris and Rice reported that the probability of violent recidivism (for individuals outside the highest three risk categories on the VRAG) decreased by 1% per year. Thus, an offender could be moved to the next lower VRAG risk category after 10 years of being violent offense free and again to the next lower VRAG category after an additional 15 years of being violent offense free.

IMPACT OF CLINICAL ADJUSTMENTS

Though clinical adjustments appear to be common practice, few studies have specifically examined the impact of clinical adjustments on estimates of risk. In an unpublished study, Peacock and Barbaree (2000) found that adjustments to RRASOR scores based on treatment-related behavior (e.g., level of participation in treatment) did not improve predictive accuracy. Barbaree et al. (2001) examined the ability of treatment-related information to add to the predictive performance of an empirically guided clinical assessment measure, the Multifactorial Assessment of Sex Offender Risk for Recidivism (MASORR). Pretreatment MASORR scores did not significantly predict recidivism, and posttreatment MASORR scores produced an even lower AUC, indicating the addition of treatment-related information actually had a negative impact on predictive accuracy. Nicholaichuk and Yate (2002) found that phallometrically assessed atypical sexual arousal did not add to the predictive accuracy provided by the RRASOR in a sample of adult sex offenders, even though both the phallometric measure and the RRASOR were positively correlated with recidivism. Krauss (2004) examined the impact of judges’ adjustments to sentencing guidelines. The adjusted sentences had a significantly weaker relationship with recidivism than the unadjusted sentencing guidelines (although neither the unadjusted nor adjusted sentences were significantly related to recidivism). Finally, Hilton and Simmons (2001) examined clinician recommendations to a mental health tribunal required to make decisions about transfer to a lower level of security or release to the community. The clinicians had access to VRAG scores but could also take other information into account in making their recommendations. The clinician recommendations were not significantly correlated with VRAG scores but were still highly related to tribunal decisions (even though VRAG score was significantly predictive of violent recidivism, and clinician recommendation was not). This result suggests that clinical adjustments attenuated the potential contribution of VRAG scores to tribunal decisions. Taken together, these findings suggest that adjusting actuarial estimates of risk either has no impact or even a negative impact on predictive accuracy; the onus is clearly on those who support clinical adjustment to demonstrate empirically that such a practice is justified.

COMBINING ACTUARIAL RISK SCALES

In addition to making adjustments of actuarial estimates of risk to reoffend, another common clinical practice is to score and combine the results of multiple actuarial risk scales. Doren (2002) has suggested that multiple risk scales can be combined to increase predictive accuracy to the extent that the scales differentially assess antisociality and atypical sexual interests. Many actuarial risk scale items load onto one of these two dimensions along with a third factor that seems to capture predominantly demographic differences between sex offenders against children and sex offenders against adults (Barbaree, Langton, & Peacock, 2006b; Roberts, Doren, & Thornton, 2002; Seto, 2005).

Combining multiple risk scales seems intuitively reasonable. It is a psychometric principle that adding relevant items increases the internal reliability of a scale, at least up to a certain point (Anastasi & Urbana, 1996). Moreover, there is evidence that risk ratings for violence in the near future have a stronger relationship with that particular outcome when the raters agree (McNiel, Lam, & Binder, 2000). On the other hand, subjectively combining the results of multiple actuarial scales may recapitulate the problems associated with the traditional clinical approach of subjectively combining empirically identified risk factors (Grove et al., 2000; Kahneman, 2003).

To address this question, I examined the impact of combining actuarial risk scales using a variety of logical and statistical methods in a sample of 215 sex offenders (Seto, 2005). I focused on three intuitively appealing rules for combining actuarial risk scales, two of them similar to medical rules that are used to combine the results of diagnostic tests (Gross, 1999; Politser, 1982). The first rule is “believe the negative,” which is to diagnose the disorder only if all the diagnostic tests are positive; in the current context, all risk scales must exceed a given threshold to designate an offender as someone who is dangerous (i.e., as someone who is expected to reoffend). The second rule is “believe the positive,” which is to diagnose the disorder if any one of the diagnostic tests is positive; in the current context, consider an offender to be dangerous if any of the scales exceed a given threshold. The third rule is “average”: that is, to average the results of the different risk scales after they are transformed to the same metric such that a relatively high score on one scale would be offset by a relatively low score on another scale.

These three rules represent combinations that are encountered in sex offender risk assessment. For example, Doren (2002) described a version of the believe-the-positive rule for combining risk scales that load differently onto the dimensions of antisociality and atypical sexual interests (see also Doren, 2004c; Roberts et al., 2002). I also used multiple logistic regression and principal components analysis to see if actuarial scales, or components of those scales, could be combined using statistical optimization methods to yield greater predictive accuracy.

These different analyses revealed that combining scales did not provide a statistically significant or consistent advantage over the single actuarial risk scale producing the highest AUC for prediction of violent or specifically sexual recidivism. This was the case whether the scale scores were combined using the believe-the-negative, average, or believe-the-positive rules, combined on the basis of relative rank (percentile score) in the sample or expected recidivism rates or combined using statistical optimization methods. Although it is possible that an idiosyncratic rule for combining actuarial risk scale results could perform better than a single scale, the results of the optimization analyses suggest this is highly unlikely. I concluded that the practice of combining and interpreting the results of multiple actuarial risk scales when assessing the risk of sex offenders is inefficient, at best, because each additional risk scale takes time and effort to complete.

3

Barbaree et al. (2006b) recently showed that four different actuarial risk scales—VRAG, SORAG, RRASOR, and Static-99—identify different groups of sex offenders as higher in risk in the same sample. In other words, offenders identified as relatively high risk (on the basis of their percentile score) on one actuarial risk scale did not receive the same rank on another scale. The difference in percentile rank was inversely related to the correlation between scale scores, so scales that were highly correlated with each other produced smaller discrepancies. Barbaree et al. suggested this finding justifies scoring and interpreting multiple actuarial risk scales to avoid confusion when different evaluators can arrive at different statements about an offender’s risk if they use different actuarial risk scales. Barbaree et al. (2006b) proposed that evaluators score multiple actuarial risk scales—although this does not improve predictive accuracy—and then reconcile any discordant findings by describing how the different scales load onto the risk dimensions of antisociality and atypical sexual interests (Barbaree et al., 2006b; Roberts et al., 2002; Seto, 2005).

Barbaree et al.’s (2006b) proposed solution appears to open the door again for subjective judgment in the reconciliation of discordant scores. A less confusing option would be to select the best available scale for the risk assessment purpose and to explain why this scale was selected. Evaluators might still disagree about which scale is best for a particular assessment, but the criteria by which this could be judged would be objective. Criteria for the selection of an actuarial risk scale would include the sex offender population (the scales mentioned in this chapter were developed for men and may not be generalizable to adolescent sex offenders or female sex offenders), outcome of interest (specifically sexual recidivism or the broader, but more complete, outcome of violent recidivism), the degree of predictive accuracy it has obtained, the number of independent replications that have been conducted, correspondence between expected and observed recidivism rates in cross-validation studies, and ease of use in the local context (the RRASOR can be easily scored from a summary of sexual offense history, whereas the SORAG requires phallometric testing and the scoring of the PCL–R).

A SPECIAL RISK SCALE FOR SEX OFFENDERS AGAINST CHILDREN?

The actuarial risk scales described earlier were developed in mixed samples of sex offenders. It is possible, in principle, for a specially developed risk scale to provide even better performance specifically for sex offenders against children. Any such scale would have a heavy representation of variables reflecting antisociality—psychopathy, criminal history, early conduct problems, and so forth—given the importance of such variables in predicting recidivism in myriad groups of offenders, including mixed groups of offenders, mixed groups of sex offenders, female offenders, juvenile delinquents, and mentally disordered offenders (Bonta et al., 1998; Coulson, Ilacqua, Nutbrown, Giulekas, & Cudjoe, 1996; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998; L. Simourd & Andrews, 1994). This is especially true if the scale is intended to predict violent recidivism. At the same time, some offender- or offense-specific variables might make a small but significant contribution, especially if the scale is intended to predict sexually motivated offenses. These variables would include indicators of pedophilia, including phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children, having boy victims, having multiple child victims, having very young victims, and having unrelated child victims. It is possible, in principle, to specifically develop an actuarial risk scale for pedophilic sex offenders. Because the offenders would be homogeneous with regard to pedophilia, however, I would expect antisociality variables to have much greater weight in any such scales. Similarly, developing a specific risk scale for psychopathic sex offenders would result in atypical sexual interest variables having much greater weight.

In practice, demonstrations of the robustness of the VRAG in different populations of offenders suggest that good predictive performance can be obtained with existing actuarial risk scales (Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 2006). Thus, the VRAG is still significantly predictive of recidivism among incest offenders, spousal assaulters, and nonforensic psychiatric patients, and the Static-99 and SORAG have comparable predictive accuracy among groups of sex offenders distinguished according to victim age or relationship to the victim (Bartosh et al., 2003; G. T. Harris, Rice, et al., 2003). Given the predictive ceiling that might be achieved with excellent scoring reliability and no missing information, special scales for sex offenders with child victims may not be capable of yielding significantly greater accuracy.

RISK AMONG MEN WHO HAVE NOT YET COMMITTED A SEXUAL OFFENSE AGAINST A CHILD

The research that has been reviewed so far in this chapter has focused on the risk of future offenses among men who have already committed a sexual offense. In other words, the actuarial risk scales that have been developed predict recidivism. Much less is known about the factors that predict whether someone who has not had any known sexual contacts with a child will commit a sexual offense in the future. How can clinicians or researchers identify men who are at risk of committing sexual offenses against a child for the first time? Rabinowitz, Firestone, Bradford, and Greenberg (2002) followed a sample of 221 men who had been criminally charged and who met diagnostic criteria for exhibitionism. None of these offenders were known to have committed a contact sexual offense at the time they were assessed. Nonetheless, among this group of exhibitionistic offenders, phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children distinguished those who subsequently committed contact sexual offenses from those who committed noncontact sexual offenses again during the average follow-up of almost 7 years. During the follow-up period, 14 men committed a contact sexual offense and 27 committed another noncontact sexual offense. Other data also suggest that some exhibitionists go on to commit sexual offenses against children (Gebhard, Gagnon, Pomeroy, & Christenson, 1965; Rooth, 1973). This crossover in offending is not unusual; other studies have found that substantial proportions of exhibitionists have sexually offended against children, and some men who sexually offend against adults also have child victims (e.g., Abel, Becker, Cunningham-Rathner, Mittelman, & Rouleau, 1988; Sugarman, Dumughn, Saad, Hinder, & Bluglass, 1994; Weinrott & Saylor, 1991). Little else is known about what distinguishes exhibitionists or offenders with adult victims who go on to sexually offend against a child from those who do not.

Focusing on another population of men who could be at risk for sexually offending against children, my colleague and I (Seto & Eke, 2005) recently completed the first follow-up study of child pornography offenders, a group of men who are likely to be pedophiles as discussed in

chapter 3

(Seto, Cantor, & Blanchard, 2006). We found that prior criminal history predicted future offenses in a sample of 201 child pornography offenders, with 23% of the 112 men with a prior criminal history and 9% of the 89 men without such a history committing another offense of any kind during the follow-up period (Seto & Eke, 2005). If one takes into account both prior and current offenses, child pornography offenders with no other forms of criminal involvement were the least likely to commit any future offenses. Those who had a history of contact sexual offenses were the most likely to commit a contact sexual offense in the future (9% of the 76 men who had a contact sexual offense history sexually offended during the follow-up period).

The studies reviewed so far in this section are of men who have already come into contact with the criminal justice system. What about risk to have sexual contact with a child among individuals with no prior criminal history? As discussed in

chapter 4

, childhood sexual abuse may be a risk factor for the onset of sexual offending, but it is not a necessary or sufficient factor. Salter et al. (2003) followed 224 sexually abused boys for 7 to 19 years and found that 26 of them (12%) subsequently committed a sexual offense, most involving a child. These sexual offenses occurred soon after the sexual abuse; the average age of the sexually abused boys was 11, and the average age at the time of a sexual offense was 14. Of the 26 boys, 19 committed only a single sexual offense during the follow-up period. Sexually offending was associated with a history of physical neglect, lack of supervision, and sexual abuse by a female perpetrator. The sexually abused boys who committed sexual offenses were also more likely to commit nonsexual offenses.

Widom (1995) followed a sample of 908 children who had been physically abused, sexually abused, and/or neglected and compared their criminal outcomes with those of a matched group of children who had not been abused or neglected. The 153 children who had been sexually abused had almost 5 times the odds of being arrested for a sexual crime, which could include sexual contact with a child but could also include indecent exposure (exhibitionism

), peeping (voyeurism

), or prostitution. In comparison, children who had been physically abused had 4 times the odds of being arrested for a sexual crime. Only 0.7% of the sexually abused children were arrested for rape or sodomy, which was not a significantly higher proportion than the 667 children in the comparison group (0.4%).

Hanson, Scott, and Steffy (1995) found that 2% of their group of 137 nonsex offenders committed a sexual offense during the follow-up period of 15 or more years. Langan et al. (2003) found that 1.3% of 262,420 nonsex offenders released from the same prisons were arrested for a sexual offense during the 3-year follow-up period. P. Marshall (1997) analyzed data from the United Kingdom and found that 1 in 90 men born in 1953 had a conviction by the age of 40 for a sexual offense involving contact with a victim (including attempts to have sexual contact with a victim but excluding convictions for noncontact sexual offenses such as indecent exposure or pornography). The majority of these sexual offenses involved a minor.

Surveys of students have indicated that some men in the community are sexually interested in children; these men might have sexual contacts with children if other factors or certain conditions are present (Briere & Runtz, 1989; Smiljanich & Briere, 1996). This is a difficult question to investigate because of access to potential participants for the necessary followup research. I would predict that those who are most at risk in the general population are antisocial and pedophilic. At the same time, some men who are antisocial but nonpedophilic will also commit sexual offenses involving children, as will some men who are pedophilic but not particularly antisocial. The victims of their offenses may differ, however. I would expect antisocial, nonpedophilic individuals to target older girls who show some signs of sexual maturity, whereas pedophilic, relatively less antisocial individuals would be more likely to target boys or younger girls.

The puzzle of incest offenders, who tend to be less antisocial and less likely to be pedophilic than men who offend against unrelated child victims, was discussed in

chapter 6

. Males who are sociolegally rather than genetically related to a child are at greater risk to commit incest, as are males who did not consistently live with a female child (daughter or sister) during the first few years of her life. Speculatively, fathers who suspect the paternity of a child, are unattractive to potential female partners, and are dissatisfied with their current marital or common-law relationship would also be at greater risk. Further research on at-risk men in the general population could lead to the development of actuarial risk scales for the onset of sexual offending against children.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Sex offender risk assessment has advanced greatly in the past 15 years with the development and promulgation of actuarial risk scales to predict recidivism. Cross-validation studies support the reliability and predictive validity of these scales, and two recent studies have suggested that the probabilistic estimates that are provided by these actuarial scales are robust (Doren, 2004b; G. T. Harris, Rice, et al., 2003; but see Mossman, 2006). The use of actuarial risk scales is rapidly becoming a standard practice, especially in high-stakes assessments such as dangerous offender hearings in Canada and sex offender civil commitment proceedings in the United States. It is possible that the actuarial revolution in risk assessment will continue to spread, first to other sex offender populations (with the development and validation of actuarial risk scales for adolescent sex offenders and female sex offenders), then to other areas of forensic clinical practice (special groups such as fire setters and children with sexual behavior problems), and eventually to nonforensic areas of clinical practice (e.g., assessing the probability of relapse after an individual’s first major episode of depression).

Common clinical practices such as the adjustment of actuarial estimates of risk and the subjective combination of results from multiple risk scales are not supported by empirical research. More work needs to be done to explore these practices and to determine when, if ever, they are justified. More research is also needed on the development of dynamic risk assessment measures and risk measures for at-risk individuals who have not committed sexual offenses against children (e.g., noncontact sex offenders such as exhibitionists and child pornography offenders with no history of sexual contacts with children). Areas for further refinement of sex offender risk assessment include revision of actuarial scale items, determining the most effective ways to communicate information about risk (e.g., Hilton, Harris, Rawson, & Beach, 2005), and determining how to best organize risk-related decisions, such as transfer to lower security or release to the community, to avoid the discounting of valid predictions about recidivism (Hilton & Simmons, 2001). Sex offender risk assessments, however accurate they can be, will have little impact on public safety and offender outcomes if decisions about sentencing, supervision, and intervention are not directly linked to actuarial risk estimates.

What is likely to be the next major advance in sex offender risk assessment? G. T. Harris and Rice (2003) have suggested that actuarial risk scales scored with complete information and high reliability may have already reached a predictive ceiling. On the other hand, it is possible that risk assessment can become more accurate by incorporating variables reflecting new content and using new methods. In particular, emerging research on the etiology of pedophilia may facilitate future developments of risk assessment measures (e.g., the inclusion of neuropsychological or neurological measures).

Once higher risk individuals have been identified, what can be done to reduce the likelihood that children will be sexually abused? I discuss interventions in

chapter 8

.