8

INTERVENTION

In this chapter, I first summarize meta-analytic reviews regarding the impact of different psychological treatment approaches for sex offenders against children and then review the literature on the effects of medications and surgical castration. I also discuss interventions other than treatment— legal responses involving sentencing or supervision on probation or parole and primary and secondary child sexual abuse prevention programs—and conclude with an overview of important scientific and practical issues to consider in the development and evaluation of interventions. When possible, I distinguish among research examining the impact of treatment on sex offenders against children, pedophilic sex offenders, or pedophilic individuals.

SEX OFFENDER TREATMENT OUTCOME

Given the importance of the question regarding the effectiveness of treatment on sex offender recidivism, it is perhaps not surprising that multiple meta-analyses have been reported.

1

I begin with a recent meta-analysis of 43 English language studies of psychological treatments (

N

= 9,454 sex offenders), which reported that treated sex offenders had lower sexual recidivism rates than sex offenders in comparison conditions, 17% versus 12% (Hanson et al., 2002). The three studies that examined sexual recidivism using randomized assignment, the strongest inference study design, showed no effect of treatment, whereas the 17 studies that used what was described as

incidental assignment

designs indicated a positive effect of treatment. Hanson et al. (2002) considered a study to have used incidental assignment if the reasons for group assignment did not appear to be related to offender risk to reoffend; for example, no treatment spots were available at the time, or the offender’s sentence did not correspond to when the treatment program was offered. The actual reasons for not receiving treatment included offenders being released before implementation of a treatment program, offenders being matched on risk factors from archived records, offenders receiving earlier versions of a treatment program, and offenders receiving no treatment or treatments judged to be of lower quality for administrative reasons such as program unavailability or insufficient time left in their sentences. Hanson et al. (2002) considered these designs to be informative in the absence of more randomized clinical trials evaluating sex offender treatment. The results of this meta-analysis have been cited as evidence that sex offender treatment is effective in reducing recidivism.

The meta-analysis by Hanson et al. (2002) has been criticized, however, by Rice and Harris (2003) in terms of study design quality ratings and other decisions. Rice and Harris pointed out that all but 3 of the 12 studies identified as incidental assignment studies of contemporary treatments included men who would have refused or dropped out of treatment—if treatment had been offered to them—in the comparison group but excluded men who refused or dropped out of treatment from the treatment group. Given that men who refuse treatment or drop out once treatment begins are more likely to reoffend (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004), this decision creates a selection bias, independent of any possible treatment effect, that increases the likelihood of finding fewer reoffenses among the treatment group. Rice and Harris also identified methodological issues about the 3 remaining incidental design studies. At the same time, Rice and Harris pointed out that 2 studies rated as lower in methodological quality in fact could have been informative because the treatment and comparison participants were matched on a number of risk factors (Rice, Quinsey, & Harris, 1991; Quinsey, Khanna, & Malcolm, 1998). Neither of these two studies found a beneficial effect of treatment.

As another example of disagreement about study coding, Hanson et al. (2002) reported that cognitive–behavioral interventions produced larger effects than other forms of treatment. Treatments were deemed to be contemporary if the treatment was being offered at the time of the meta-analysis or if it was a cognitive–behavioral treatment that had been available since 1980. Rice and Harris (2003) observed that one of the studies that was not identified as being contemporary reported data on cognitive–behavioral treatment delivered between 1974 and 1983, with the majority of offenders treated after 1980 (Perkins, 1987); this study found a large negative effect of treatment.

Rice and Harris (2003) reanalyzed data from six evaluation studies that they considered provided meaningful information about treatment outcome from the Hanson et al. (2002) meta-analysis (Borduin & Schaeffer, 2001; Lindsay & Smith, 1998; Marques, 1999; Quinsey, Khanna, & Malcolm, 1998; Rice et al., 1991; Romero & Williams, 1983). These six studies comprised the four randomized clinical trials and two studies using matched comparison groups. All but one study evaluated programs for adult sex offenders. Rice and Harris’s (2003) reanalysis suggested a trend toward treatment having a deleterious effect on sexual recidivism, with treated sex offenders having a nonsignificantly higher reoffense rate than sex offenders in the comparison conditions.

Robertson, Beech, and Freemantle (2005) found an additional seven studies that they added to the meta-analysis reported by Hanson et al. (2002) and then examined the relationship between study design and the magnitude of any difference between sex offenders in treatment and comparison conditions. There was a significant effect of study design, with no significant group difference found for studies using random assignment, a significant difference for studies using incidental assignment, and a large difference for studies that compared offenders who completed treatment with those who began treatment but then dropped out.

The debate about the interpretation of the Hanson et al. (2002) meta-analysis results and disagreements about what constitutes acceptable study quality highlight the importance of using strong methodological designs that most if not all reviewers can agree are informative about treatment outcome. With a focus on randomized clinical trials, which provide the strongest possible inference about the effect of treatment, a recent Cochrane Collaboration review identified nine sex offender outcome studies, seven of which evaluated the impact of psychosocial interventions on proximal targets, that is, treatment targets other than recidivism (Kenworthy, Adams, Bilby, Brooks-Gordon, & Fenton, 2004). The other two studies (Marques, Day, Nelson, & West, 1994; Romero & Williams, 1983) evaluated the impact of treatment on recidivism and were included in the Hanson et al. (2002) meta-analysis. Most of these studies followed mixed groups of adult male sex offenders. Only a few studies reported specifically on pedophilic sex offenders (e.g., Hucker, Langevin, & Bain, 1988), but 52% of the combined sample examined by Kenworthy et al. (2004) had sexually offended against children. For example, Anderson-Varney (1992) randomly assigned 60 sex offenders against children to cognitive–behavioral therapy or no-treatment conditions; the outcome measures were sexual attitudes, knowledge, self-reported behavior, social avoidance, and empathy. Overall, Kenworthy et al. concluded that there was no evidence of a significant impact of treatment on the identified proximal targets.

Lösel and Schmucker (2005) have completed the largest quantitative review of sex offender treatment to date. Their review differed from the meta-analysis reported by Hanson et al. (2002) by including evaluations of medical treatments, accepting a broader definition of outcome for three comparisons, and including studies published in a non-English language. Lösel and Schmucker calculated 80 comparisons from 44 published and 25 unpublished studies: 35 comparisons of cognitive–behavioral programs, 7 comparisons of behavioral interventions, 18 comparisons of nonbehavioral interventions (insight oriented, therapeutic community, and other psychosocial treatments), 6 comparisons of drug treatments, and 8 comparisons of surgical castration. Of the comparisons, 6 used randomized clinical trials and an additional 6 used matching or statistical controls to make the treatment and comparison groups equivalent. These two sets of comparisons found no group difference in recidivism. Examining other moderators, Lösel and Schmucker reported that larger effect sizes were obtained for medical treatments versus psychosocial treatments, treatments implemented before 1970 versus those implemented later, treatments specifically designed for sex offenders versus those that were not, evaluations reported by investigators affiliated with the treatment program versus those reported by independent investigators, rapists and exhibitionists versus sex offenders against children, smaller samples versus larger samples, and studies that used both official records and self-report versus official records only.

Taken together, these quantitative reviews do not provide strong support for the efficacy of current psychosocial treatments. Innovative, theoretically informed interventions need to be developed and evaluated. Clinicians and researchers need a careful reconsideration of how well treatment models reflect what is known about sex offender risk factors and the origins of sexual offending against children, followed by rigorous evaluations of treatment programs based on these models. To assist in this theoretical and clinical development, a more detailed review of different types of interventions is given in the sections that follow.

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

In the following sections, I briefly summarize the rationale for different approaches that have been used in the treatment of sex offenders, reviewing some of the key evidence for each. Additional treatment resources are provided in

Resource C

.

Cognitive–Behavioral Treatments

Cognitive–behavioral treatments target attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that are believed to increase the likelihood of sexual offenses against children. Thus, cognitive–behavioral treatments can vary widely, depending on which factors the therapists believe are most important. As discussed in

chapter 4

, many such factors have been proposed in the clinical and research literatures, including positive views about sex with children, empathy deficits, disinhibition, and social skills deficits. A typical cognitive–behavioral treatment program might use cognitive restructuring techniques to change views about sex with children and skills-based training to increase empathic statements, self-control of behavior, and social competence.

The most popular cognitive–behavioral treatment format for adult sex offenders adapts a relapse prevention approach from the addictions field (McGrath, Cumming, & Burchard, 2003). A relapse prevention approach is also recommended in the standards and guidelines of a large international organization of clinicians and researchers working in the area of sex offender treatment (Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, Professional Issues Committee, 2005). Marlatt and Gordon (1985) outlined a strategy for assisting individuals who have completed treatment to prevent the recurrence of drug taking. This relapse prevention strategy involves (a) identifying situations in which the individual is at high risk for relapse; (b) identifying lapses, that is, behaviors that do not constitute full-fledged relapses but do constitute approximations to drug taking and that may be precursors to relapses (e.g., spending time in bars as a precursor to drinking alcohol); (c) developing strategies for avoiding high-risk situations; and (d) developing coping strategies that are used in high-risk situations that cannot be avoided and in responding to lapses that occur. In the context of sexual offenses against children, lapses might include behavior such as masturbating to sexual fantasies about children, and high-risk situations might include spending time alone with a child or spending time in places where many children are likely to be present. Janice Marques (personal communication, March 23, 2006) has pointed out, however, that there is wide variation in the format and content of programs that describe themselves as using a relapse prevention approach (see McGrath, Cumming, & Burchard, 2003). Probably the only common theme is that cognitive–behavioral techniques are used to increase the offender’s ability to detect and respond to potentially risky situations.

Hanson et al. (2002) identified 13 studies that could be described as cognitive–behavioral in their approach and 2 that were systemic (targeting both the individual offender and others around him) in their approach (multisystemic therapy and family therapy, which involve both adolescents and their parents or caregivers). On average, these studies showed a significant difference in recidivism between sex offenders in the treatment conditions and sex offenders in the comparison conditions (though this does not mean cognitive–behavioral therapy can reduce sex offender recidivism for the reasons provided by Rice & Harris, 2003).

An excellent example of the cognitive–behavioral and relapse prevention approaches is the Sex Offender Treatment Evaluation Project (SOTEP), which was funded by an act of the California State Legislature (Marques, Nelson, Alarcon, & Day, 2000). The SOTEP treatment program was carefully designed and was comprehensive and impressive in its scope and intensity. SOTEP’s distinctive features included random assignment of adult volunteers to treatment and no-treatment conditions after they were matched for age, criminal history, and type of offender; implementation of an intensive, 2-year cognitive–behavioral treatment program based on relapse prevention principles; a 1-year aftercare program in the community; and a program evaluation that included both proximal (within-treatment) and ultimate outcomes. The proximal treatment goals were to increase personal responsibility for sexual offending, decrease cognitive distortions and other justifications, decrease atypical sexual arousal (as assessed in the phallometric laboratory), understand relapse prevention concepts and techniques, improve ability to identify high-risk situations, and improve skills in avoiding and coping with high-risk situations. The ultimate treatment goal was to reduce the rate of new offenses.

The SOTEP program has the distinction of being the first, and so far only, randomized trial of cognitive–behavioral treatment applying relapse prevention principles to adult sex offenders. Treatment participants met three times a week for 90-minute group therapy sessions as well as individual therapy sessions. Treatment participants also attended groups focusing on sex education, human sexuality, relaxation training, stress and anger management, and social skills. Other treatment components were offered on a prescriptive basis. For example, 69% of the treatment sample were deemed to have significant alcohol or drug abuse histories and were therefore required to complete a relapse prevention group focusing on substance abuse. Offenders with atypical sexual arousal patterns (e.g., pedophilia) were offered behavioral treatment (see next section, Behavioral Treatments) targeting their arousal to inappropriate targets or activities. Group services were detailed in manuals to standardize the format and content of sessions.

Treated sex offenders lived in Atascadero State Hospital, whereas the two control groups remained in prison. Although some treatment services were available in prison (e.g., anger management and substance abuse), no organized sex offender treatment was available in these correctional facilities during the time the SOTEP trial ran. Approximately one third of all eligible sex offenders volunteered to participate (see Marques, Wiederanders, Day, Nelson, & van Ommeren, 2005, for the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria). Nearly three quarters of eligible sex offenders victimized children; those who victimized children were more likely to volunteer for treatment, and those who victimized only boys were more likely to volunteer than those who victimized any girls. This suggests that there was a high proportion of pedophiles among the volunteers, and therefore the SOTEP results have direct bearing on the impact of treatment on pedophilic sex offenders.

A total of 259 volunteers were randomly assigned to the treatment condition. Of these, 55 withdrew their consent after having learned of their selection but before their transfer to the hospital. Of the 204 men who were admitted to the treatment program, 37 did not complete the program, either because they voluntarily withdrew (27) or because they presented severe management problems in the hospital (10). Of these 37 men, 14 left the program before completing 1 year of treatment. A total of 225 other volunteers were randomly assigned to the no-treatment condition, and 220 were selected as a comparison group from the sex offenders who did not volunteer for SOTEP. Many of the nonvolunteers reported that they did not want treatment, but some refused because they had good job assignments, were already located near family, or did not want to become state hospital patients. The three groups were matched according to offender age (over or under age 40), offense history (prior felony conviction or not), and sex offender type (adult victim, boy victim, girl victim, or both boy and girl victims).

The final wave of data collection was completed in 2001, with an average follow-up period of 8 years from release, ranging from 5 to 14 years. Recidivism data were obtained from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, California Department of Justice (rap sheets listing criminal charges and convictions), and California Department of Corrections (regarding parole violations and returns to prison). The final SOTEP report found no significant differences in the recidivism of treated sex offenders, volunteer controls (offenders who volunteered but were randomly assigned to the control condition), and nonvolunteer controls who had refused treatment (Marques et al., 2005). There was a nonsignificant trend for those who victimized children to be more likely to reoffend after treatment (21.9% for treated offenders and 17.2% for volunteer controls) compared with an opposite trend for rapists (20.4% for treated offenders and 29.4% for volunteer controls). The 14 men who dropped out early from treatment were more likely to reoffend than men who withdrew from the program before beginning treatment, those who completed at least 1 year of treatment, and those offenders in the volunteer and nonvolunteer control groups.

There were no significant differences between the three main groups (treated, volunteer controls, and nonvolunteer controls) even after excluding the early dropouts from treatment, which could be considered a generous test of the hypothesis that treatment reduces recidivism because some of the volunteer controls would likely have become early dropouts. This was also true after controlling for an inadvertent nonequivalence between the groups on a set of static risk factors (in addition to age, offense history, and sex offender type): prior sexual offenses, convictions for noncontact sexual offenses, any unrelated victims, any stranger victims, any male victims, offender age, and never having been married.

Of great relevance to theories of sexual offending (reviewed in

chap. 5

, this volume), the SOTEP program did have a significant impact on its stated goals. Treatment participants showed a significant decrease on self-report measures of minimization of responsibility and phallometric measures of atypical sexual arousal. The researchers also obtained posttreatment clinician ratings of relapse prevention skills. Both pre- and posttreatment measures of sexual arousal to male children were significantly related to sexual recidivism, but the self-report measures and the clinician ratings were unrelated to new sexual offenses. This suggests that the treatment program did have the desired impact but that most of the treatment targets were unrelated to recidivism. This is consistent with meta-analytic results suggesting that acceptance of responsibility, expressions of victim empathy, and so forth are not significant predictors of recidivism among sex offenders (Hanson & Bussière, 1998 ; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004). Taken together, these results suggest that most of the SOTEP treatment targets are not necessary elements of an effective sex offender treatment program (see Kirsch & Becker, 2006).

Marques et al. (2005) discussed reasons why the SOTEP program did not have a significant impact on recidivism and suggested several ways in which they would change the study and program design in a future evaluation. These changes included recruiting more high-risk offenders, conducting pretreatment assessments on all sex offenders, and regularly monitoring treatment progress to ensure that treatment participants were learning the concepts and skills being taught. A methodological confound of the SOTEP trial is that treated sex offenders were held in a secure hospital, whereas the volunteer and nonvolunteer control groups were held in prison; there may have been differences between these settings that influenced offender recidivism (e.g., the controls held in prison would associate with other potentially more antisocial inmates). It may be tempting for some to discount or dismiss the SOTEP findings as a result of this confound. Despite these caveats, however, it should be realized that a well-designed and implemented treatment program that was state of the art at the time (and is similar to the treatment programs most commonly offered today) did not find any significant effect on the ultimate outcome of recidivism.

The SOTEP finding has major implications for sex offender treatment providers, researchers, and policymakers, as suggested by Marques et al.’s (2005) conclusion that “it may be difficult to obtain funding and to conduct randomized clinical trials but we strongly believe that more of these are needed to move this field forward” (p. 103). Kenworthy et al. (2004) went even further, stating, “The ethics of providing this still-experimental treatment to a vulnerable and potentially dangerous group of people outside of a well-designed evaluative study are debatable” (p. 1). In contrast, treatment advocates such as W. L. Marshall (2006a) have suggested that randomized clinical trials have limitations in terms of their external validity and generalizability to operating programs and have focused instead on the more positive results of weaker study designs. The scientific and ethical rationales for conducting more randomized clinical trials to evaluate sex offender treatment are discussed later in this chapter.

Behavioral Treatments

Recent reviews of the history of behavioral treatment for pedophilia are provided in Laws and Marshall (2003) and W. L. Marshall and Laws (2003). Unlike cognitive–behavioral treatments intended to reduce recidivism among sex offenders against children, discussed in the previous section, the following behavioral treatments directly target sexual arousal to children.

Aversive conditioning techniques were used as early as the 1950s for paraphilias such as fetishism and transvestic fetishism (e.g., Marks & Gelder, 1967; M. Raymond, 1956). Prior to the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder and decriminalization of homosexual behavior in Western societies, the early behavioral treatment literature also focused on sexual arousal to same-sex persons.

In the behavioral treatment of pedophilia, aversion techniques are used to suppress sexual arousal to children, and masturbatory reconditioning techniques are used to increase sexual arousal to adults. In aversion procedures, unpleasant stimuli such as mild electric shock or ammonia are paired with repeated presentations of sexual stimuli depicting children. In a variation called covert sensitization

, the aversive stimulus is imagined, for example, being discovered by family members or friends while engaging in sexual behavior involving children.

Satiation

is a behavioral technique for decreasing sexual arousal to children that does not depend on the use of aversive cues. In this procedure, the treatment participant masturbates to ejaculation while verbalizing aloud variations of his pedophilic fantasies. After ejaculating, and throughout the refractory period, he is told to continue masturbating to the same fantasies over several long sessions. Masturbatory reconditioning involves associating sexual arousal with adults. Techniques include thematic shift

, in which the participant masturbates to a pedophilic sexual fantasy until the point of orgasm, then switches to a sexual fantasy about an adult.

The efficacy of behavioral approaches for changing sexual arousal patterns has been reviewed by Barbaree, Bogaert, and Seto (1995) and Barbaree and Seto (1997). The research suggests that behavioral techniques can have an effect on sexual arousal patterns, but it is unclear how long these changes are maintained and whether they result in actual changes in interests as opposed to greater voluntary control over pedophilic sexual arousal (e.g., Lalumière & Earls, 1992).

Nonbehavioral Treatments

Nonbehavioral treatments include humanistic, psychodynamic, and other insight-oriented therapies. Freud (1905/2000) did not discuss pedophilia except to speculate that an exclusive preference for (prepubescent) children was rare; instead, he suggested that most sexual contacts with children were a result of personal inadequacy or lack of access to adult sexual partners. Psychodynamically influenced ideas about sexual offenses against children refer to identification with the perpetrator and traumatic reenactment by individuals who were themselves sexually abused as children. Socarides (1991) suggested that boy-preferring pedophilia was a means of resolving deep psychological conflicts, and Groth (1979) proposed that “the offender’s adult crimes may be in part a repetition and acting out of a sexual offense he was subjected to as a child, a maladaptive effort to solve an unresolved early sexual trauma” (p. 15). Groth and Birnbaum (1978) distinguished between regressed and fixated offenders against children, comparable to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(4th ed., text revision; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) distinction between nonexclusive and exclusive pedophilia.

In general, nonbehavioral treatments tend to be less structured than cognitive–behavioral or behavioral treatments. They often focus on insight into the reasons for sexual offending, acceptance of responsibility for the crimes, and expressions of remorse and victim empathy. Only a few evaluations of nonbehavioral therapies have been reported. Of the five studies that evaluated the impact of treatments categorized as psychotherapy (i.e., not behavioral or cognitive–behavioral treatment) in the Hanson et al. (2002) analysis, four showed a nonsignificant trend toward greater sexual recidivism in the treatment group.

The best-controlled study in the nonbehavioral treatment category was reported by Romero and Williams (1983), who compared offenders (a mixed group of predominantly rapists and offenders with child victims) who were randomly assigned to intensive probation supervision or psychodynamically oriented group therapy in addition to intensive supervision. Those assigned to psychotherapy plus intensive supervision tended to have higher rates of rearrest for sexual offenses than those assigned to intensive supervision alone. This tendency was statistically significant when the analysis was restricted to those who completed more than 40 weeks of treatment. This finding can be compared with similar negative findings for samples of general offenders who participate in humanistic, psychodynamic, and other insight-oriented treatments (for a review, see Andrews et al., 1990); together, these results suggest that nonbehavioral approaches are contraindicated for the treatment of (pedophilic) sex offenders.

MEDICAL INTERVENTIONS

Medical interventions are similar to behavioral treatments in focusing on reducing sexual arousal to children and presumably thereby reducing sexual behavior directed toward children. Medical interventions attempt to do this by targeting the hormones or neurotransmitters underlying sexual drive, arousal, and behavior (what I refer to subsequently as sexual response

). There is less empirical research on medical interventions than on psychological treatments, but I devote proportionally more space in this chapter to reviewing this literature because the psychological treatments have already been extensively reviewed (e.g., Hanson et al., 2002; Lösel & Schmucker, 2005). The medical literature also highlights important methodological and practical issues in sex offender treatment evaluation research, including treatment refusal, dropout, and noncompliance, and the equivalence of treatment and comparison groups.

Drug Treatments

The common aim of drug therapies in the treatment of pedophilia is to reduce sexual response to children. Much of the initial interest was on antiandrogens to suppress sexual response, but clinicians and researchers have more recently focused on serotonergic agents. Outcome research on the use of these drugs in the treatment of pedophilia and other paraphilic behavior is summarized in the sections that follow.

Antiandrogens

It is a logical hypothesis that antiandrogens would have an impact on pedophilic sexual response because testosterone plays a critical role in male mammalian sexuality (J. M. Davidson, Smith, & Damassa, 1977). The earliest clinical studies, conducted in Germany, were reported by Laschet and Laschet (1971), who treated more than 100 paraphilic men; most were pedophiles or exhibitionists. Today, the most commonly prescribed agents are cyproterone acetate (CPA) or medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), both of which interfere with the action of testosterone. Specifically, CPA blocks intracellular testosterone uptake and thus reduces plasma testosterone, and MPA reduces gonadotropin secretion and catalyzes testosterone. Anecdotal accounts by reviewers of this literature suggest that CPA is more likely to be used in Canada and Europe and less likely to be used in the United States because it is not approved for use by the Federal Drug Administration in the United States. The use of MPA has been approved in the United States, but not for the treatment of paraphilias. The use of both CPA and MPA in the treatment of pedophilia and other paraphilias is off-label

, meaning it is not specifically approved by regulatory bodies for this purpose. Side effects of antiandrogens include headaches, dizziness, nausea, gynecomastia

(development of abnormally large breasts in males), depression, and osteoporosis.

The efficacy of antiandrogens in reducing the frequency or intensity of sexual drive and arousal has some support, but there have not been many large, well-controlled evaluation studies. Gijs and Gooren (1996) reviewed the literature evaluating the effects of CPA and MPA, focusing on methodologically strong studies (e.g., use of double-blind procedure, placebo condition, and random assignment). Gijs and Gooren identified four controlled studies of CPA and six such studies of MPA. All four studies of CPA reported that treated men had a significant reduction in sexual response, whereas only one of the six MPA studies showed an effect. Hucker et al. (1988) reported one of the randomized clinical trials evaluating MPA treatment. These investigators started with 100 men referred for assessment and treatment after being accused of sexually offending against a child. Of those referred, 52 men either denied the allegations or did not complete the assessment; 48 men completed the assessment; and 18 of this subsample agreed to participate in the drug trial. The accused were not pressured to participate in the drug trial, and alternative treatments were available for those who did not want to take the medication, in keeping with the authors’ ethical guidelines. As a demonstration of the problem of attrition and noncompliance in drug therapies for sex offenders, only 11 men completed a 12-week trial; 5 received MPA and 6 received a placebo. One man was excluded from the study for medical reasons after a parathyroid tumor was found; he was taking a placebo. Another man was excluded because hormone testing indicated that he was not taking the medication. In addition, 5 other men dropped out of the study, 3 from the MPA group and 2 from the placebo group. Dropouts significantly differed from those who completed the treatment or placebo phase in reporting more frequent sexual fantasies about children. (The authors recognized this might represent a selection effect that would influence their results.) Men in both the MPA and placebo conditions reported a decrease in sexual fantasies, but men who received the placebo still reported more fantasies at the end of the trial (M

= 28 per month vs. 12 per month for the MPA group). It is notable that MPA did have the desired effect on sex hormones, with a large drop in testosterone among those who completed the follow-up and no change among those who completed the placebo condition. Hucker et al. (1988) did not report on recidivism as an outcome.

Focusing on two additional studies of pedophiles, Cooper, Sandu, Losztyn, and Cernovsky (1992) approached 28 pedophiles to participate in a drug trial and had 18 refusals. Moreover, they reported data on only 7 pedophiles from their double-blind study because an additional 3 men dropped out during the initial placebo phase. Cooper et al. tested both MPA and CPA over 28 weeks. Both drugs appeared to reduce sexual thoughts, fantasies, and behavior (frequency of masturbation and frequency of erections on awakening), and there also appeared to be an effect on penile responding, assessed phallometrically. Bradford and Pawlak (1993) treated 20 male pedophiles with alternating phases of CPA and placebo. They reported data from 17 of these men assessed phallometrically and hormonally at baseline and again 2 to 3 months later. One pedophile was dropped from the study for noncompliance, and the other 2 showed no phallometric response to child stimuli. There was a significant effect of CPA on sexual arousal to children but not sexual arousal to adults.

Serotonergic Agents

Serotonin is involved in the regulation of human sexual behavior, and antidepressant medications that have a serotonergic effect are known to reduce sexual desire and delay ejaculation in men (for a review, see Meston & Gorzalka, 1992). Some clinical investigators have gone further and suggested, with little evidence, that SSRIs such as fluoxetine or buspirone can specifically affect sexual arousal to children without affecting sexual arousal to adults (Fedoroff, 1993; Greenberg & Bradford, 1997; Kafka, 1991). For example, Bradford (2000) reported unpublished data from an open trial of sertraline on 20 pedophiles that suggested there was a decrease in pedophilic sexual response without any decrease in sexual intercourse with adult female partners or sexual arousal to adults.

The enthusiasm for serotonergic agents in the treatment of pedophilia appears to be based on uncontrolled case studies and open trials (see Gijs & Gooren, 1996). Serotonergic agents have been evaluated in only one experimental study comparing desipramine and chloripramine in a double-blind crossover trial that was preceded by a single-blind placebo condition (Kruesi, Fine, Valladares, Phillips, & Rapoport, 1992). Kruesi et al. (1992) reported a significant reduction of self-reported paraphilic behavior (predominantly exhibitionism, transvestic fetishism, obscene telephone calling, and fetishism) with either drug, but their result is difficult to interpret because only 8 of 15 paraphilic men completed the trial; 4 patients were dropped because they responded to the placebo, and 3 did not complete the drug trial. Including the patients who responded to the placebo would have attenuated, and perhaps eliminated, the apparent positive effect of the drugs on self-reported paraphilic behavior.

Greenberg, Bradford, Curry, and O’Rourke (1996) reported on a retrospective analysis of 58 paraphilic men (74% were pedophiles) treated with SSRIs. They excluded men who had previously been treated and followed the sample for 3 months. Greenberg et al. reported that the men reported a significant decrease in paraphilic fantasies over the 3-month follow-up, with no differences between those taking fluoxetine, sertraline, or fluvoxamine. As in the previous study, the results of this study are difficult to interpret because 17 men were dropped from the study: 9 because they discontinued the medication (4 against medical advice, 3 because of side effects, and 2 because they felt better); 1 because he changed his prescription; and 3 because they were treated with CPA, presumably because the SSRI was not considered to be helpful in reducing their paraphilic fantasies. Therefore, one would expect a more positive result for those who remained in the study. Ignoring this selection effect, Greenberg et al. concluded that drug compliance was excellent because few men missed doses between clinic visits (which should be expected, because they had already terminated patients who stopped taking the drug). Analyses that retained dropouts in an intent-to-treat comparison—a recommended method of dealing with treatment attrition effects in outcome studies—were not reported. Approximately one quarter of the sample was noncompliant with their medication.

Fedoroff (1995) suggested that a potential advantage of SSRIs over antiandrogens is that pedophiles may be more willing to take serotonergic agents. Of the 59 men who acknowledged active paraphilic symptoms in his sample of 100 male patients, 7 opted for psychotherapy alone, 41 chose an SSRI in addition to psychotherapy, and only 1 patient chose an antiandrogen. Fedoroff suggested the patients preferred SSRIs because there were fewer side effects and because there was less stigma associated with having the prescriptions filled.

Central Hormonal Agents

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists such as leuprolide acetate (Lupron) inhibit the production of testosterone by overriding pituitary regulation. Research on the effects of GnRH agonists on paraphilias has been reviewed by Briken, Hill, and Berner (2003). These authors identified 13 articles, representing a total of 118 men treated for different paraphilias in open, uncontrolled studies. Forty-three of these men were diagnosed with pedophilia; the sexual preferences of another 59 men from two mixed samples of sex offenders were not reported, but the sample descriptions indicate many had sexually offended against children.

The largest sample of pedophiles in a trial of GnRH agonists was reported by Rösler and Witztum (1998). This was an open, uncontrolled study of triptorelin pamoate with 30 paraphilic men; 25 of them were diagnosed with pedophilia. In this study, 24 men completed treatment for at least 12 months; among the others, 2 men emigrated, 3 had intolerable side effects and withdrew, and 1 withdrew because he wanted to father a child. Men who completed treatment reported fewer paraphilic sexual fantasies, a lower frequency of masturbation, and fewer incidents of “abnormal sexual behavior” (not further defined), from a mean of five incidents per month to zero during treatment. No sexual offenses against children (or acts of exhibitionism, voyeurism, or frotteurism) were reported by the participants, their relatives, or their probation officers during the course of treatment.

Briken et al. (2003) noted that most of the studies they reviewed relied on self-report data. An exception was a crossover design study by Cooper and Cernowsky (1994), who treated a pedophile who offended against girls and found that leuprolide acetate suppressed both self-reported and phallometrically assessed sexual arousal better than cyproterone acetate or a placebo. Leuprolide acetate reduced the patient’s plasma testosterone to almost zero. Briken et al. concluded there was preliminary support for the use of GnRH agonists and described an algorithm for considering antiandrogen or GnRH agonist treatment in the treatment of paraphilias. Bradford (2000) and Maletzky and Field (2003) have also described treatment algorithms; they did not present the empirical evidence supporting the decision trees they recommend. The long-term consequences of antiandrogen or GnRH agonists are unknown.

Other Medications

There have been some case reports of treatment with agents other than SSRIs or antiandrogens. For example, Varela and Black (2002) described the case of a middle-aged pedophile who reported a decrease in his sexual thoughts and behavior over the course of 1 month after being treated with carbamazepine and clonazepam.

Surgical Castration

Surgical castration has the same rationale as the use of antiandrogens to reduce sexual response but it is a permanent treatment. Removal of the testes almost completely eliminates endogenous production of androgens (the adrenal glands produce a small amount) and thus can lead to the same sex-drive-reducing effects as antiandrogens. Although it is rarely performed now, surgical castration was performed on hundreds of convicted sex offenders in the Netherlands and in Germany (Wille & Beier, 1989). It continues to be performed occasionally in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Switzerland. Surgical castration is an option for some sex offenders in the United States, with the passage of legislation in nine states since 1996 requiring chemical (antiandrogen) or surgical castration for sex offenders who want to be paroled and released into the community. Physical castration is permitted as an alternative to antiandrogens in four states, and it is the only option available in Texas. Five states permit castration only for offenders against victims under 13 or 14 years of age (C. L. Scott & Holmberg, 2003).

Wille and Beier (1989) reviewed castration cases seen from 1970 to 1980 and concluded that castration was effective because only 3% of the 99 men in the castrated group (70% were pedophiles) reoffended within an average of 11 years of follow-up compared with 46% of a comparison group of 35 men who applied for castration during the same period but did not have the surgery (the comparison group was originally 53 men: 17 men were rejected by the authorizing committee, an additional 30 men canceled their application before a committee decision was made, and 6 men canceled after receiving committee approval). Three quarters of the castrated men reported a substantial decrease in sexual interest, libido, erection, and ejaculation within 6 months of the surgery; 15% continued to have orgasms but required more intense stimulation for ejaculation to occur; and 10% remained sexually active at only a slightly diminished level. Finally, Wille and Beier reviewed 10 previous studies of castrated sex offenders that had reported sexual recidivism rates between 0% and 11% between 1959 and 1980. The nonsexual recidivism rate of the castrated sex offenders was also lower than the nonsexual recidivism rate of the comparison group, at 25% versus 43%, respectively.

Wille and Beier’s (1989) review seems to support castration as having a strong effect on recidivism. However, because there was no random assignment, there were likely important differences in risk between those who were sufficiently motivated to be castrated and those who were not willing to undergo the surgery (see later section, The Importance of Random Assignment). Moreover, a higher percentage of those in the comparison group were unavailable for follow-up, either because they could not be found by the investigators or because they refused to be interviewed once contacted.

Since the Wille and Beier (1989) review, H. Hansen and Lykke-Olsen (1997) compared a group of 21 castrated violent sex offenders and 24 violent sex offenders who refused the surgical procedure between 1935 and 1970. By 1988, 2 of the 21 castrated sex offenders had committed a new sexual offense (both after a long offense-free period and only after they had received testosterone from a general practitioner), whereas 10 of the 24 men who refused castration had sexually reoffended, even though they had a shorter time at risk than the castrated sex offenders, who were released on probation between 6 to 18 months after the operation.

SOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

One of the possible explanations for the lack of efficacy of psychological interventions is the assumption that pedophilia can be managed when the individual is not motivated to change his or her sexual behavior. The typical treatment model assumes the individual is motivated to refrain from sexual fantasies, thoughts, urges, and behavior involving children and is therefore willing to monitor his or her sexual response and avoid risky situations such as being alone with a child (Laws, Hudson, & Ward, 2000). However, some pedophilic men are not motivated to refrain from future sexual offenses; instead, they are motivated to avoid being detected for their crimes. Such men may be more likely to view their sexual contacts with children as part of ongoing romantic relationships rather than sexual abuse. They may also be more likely to view children as benefiting from the experience and to see societal reactions as the cause of any negative effects that the child experiences rather than the sexual contact itself. Hudson, Ward, and McCormack (1999) and others have also noted a distinction between offenders who actively seek sexual contacts with children and those who report they were motivated to avoid sexual contacts with children but nonetheless committed sexual offenses when they were depressed, stressed, or otherwise less able to restrain their behavior. Hudson et al. described this distinction as being between approach and avoidance pathways to sexual offending.

External controls become more important for pedophilic sex offenders who do not want to refrain from sexual offending. These external controls can include sentencing, supervision of sex offenders living in the community, and sex offender registration with police. The intensity of such external controls might vary according to the risk posed by sex offenders, with long sentences or even indefinite incapacitation for the highest risk offenders and less expensive or intrusive interventions for lower risk offenders.

Sentencing and Supervision

Correctional research has shown that criminal sanctions do not reduce recidivism. Criminal sanctions include regular sentencing, restitution programs, police cautioning, and probation. In fact, there is some evidence to suggest that criminal sanctions increase the likelihood of new offenses (Andrews et al., 1990; Lipsey, 1998). Another problem with criminal sanctions, as noted in

Appendix 7.1

, is that the detection rate for a particular sexual offense may be low because many victims do not report the crime to police, and some guilty individuals are not successfully prosecuted.

2

Thus, two of the key elements of effective punishment of behavior (speed and certainty) are not met by criminal sanctions.

Sentencing can still reduce the incidence of sexual offenses against children, even with a negative effect on offender recidivism, by incapacitating those who are most likely to commit such offenses and most likely to reoffend against multiple victims. Because of the high costs of imprisonment (an offender in federal custody in Canada costs the government approximately $50,000 to $60,000 per year; the comparable figure in the United States is $20,000 to $25,000), long sentences are best reserved for those who are high in risk. I discussed the reliable and valid methods by which risk to reoffend can be assessed among sex offenders in

chapter 7

.

Spelman (2000) suggested that approximately one quarter of the crime reduction observed in the 1990s in the United States could be attributed to increasing incarceration since the 1980s, thereby removing offenders who would otherwise reoffend in the community. Other analyses suggest that a similar reduction in crime has been observed in countries that do not have the same high incarceration rates and that have not increased spending on policing and corrections to the same extent as the United States (see Lalumière, Harris, Quinsey, & Rice, 2005). Of course, this does not preclude the possibility that increased incarceration can lead to reduced crime in one country and other causes lead to reduced crime in other countries.

Another criminal sanction involves supervision in the community under probation or parole conditions. Regular supervision may not have an effect on recidivism because of high case loads and the resulting low frequency of contacts and reliance on self-report and office appointments, which may not be adequate to detect changes in dynamic risk factors. Intensive supervision differs from typical probation or parole supervision in having more unannounced home visits, more frequent contacts, urinalysis, home confinement, electronic monitoring, and regular polygraph testing (see Gendreau, Cullen, & Bonta, 1994). Intensive supervision combined with treatment has been described as a containment or multiagency model in which sex offenders are monitored by a team of probation and parole officers, treatment providers, and polygraph examiners (English, 1998; J. Scott, Grange, & Robson, 2006). This model proposes that multiple agencies can be involved with an individual (or his family) and that coordination of these agencies increases the likelihood that their different resources will be used efficiently. Containment in the community, even with the recommended small caseloads for probation and parole officers and treatment providers, as well as regular polygraph examinations can cost less than incarceration. The unanswered question is whether the containment approach has a beneficial impact on recidivism or costs less than incarceration without a concomitant increase in recidivism.

Another supervision strategy, known as circles of support and accountability

, involves surrounding the offender with supportive volunteers who monitor his behavior and assist him in adjusting to life in the community on the completion of his prison sentence (R. J. Wilson, Huculak, & McWhinnie, 2002; R. J. Wilson, Picheca, & Prinzo, 2005). This model was developed for men who had served their entire prison sentences in Canada and were therefore released without any parole supervision or other legal constraint. In the circles of support and accountability model, four to six members of the support group visit the offender daily, assist him in living tasks such as obtaining housing and employment, and mediate if necessary with police, media, and concerned citizens. These volunteers are given training on the patterns of sexual offending (e.g., potentially high-risk situations) and the relevant law and are able to consult with professionals such as police officers, psychologists, and other members of an advisory board. R. J. Wilson et al. (2005) followed 60 sex offenders involved in circles of support and accountability and compared them with 60 sex offenders who were released at the end of their prison sentences without circles of support and accountability; the two groups of offenders were matched on risk, length of time in the community, and prior involvement in sex offender treatment. After the average followup time of 4.5 years, 5% of the offenders involved in circles of support and accountability had sexually reoffended compared with 17% of the comparison offenders. In addition, 15% of the offenders in circles of support and accountability committed a new violent offense, including a sexual offense, compared with 35% of the comparison offenders. Other pilot projects have now been started throughout Canada, several states in the United States, and the United Kingdom.

Community Notification and Registration

Sex offenders against children have been subjected to extraordinary legal measures compared with other offenders, including men who have violently but nonsexually assaulted children. These include community notification of citizens when sex offenders move into an area (Megan’s Law) and the federally mandated requirements of registration with authorities on release from institutional custody (Jacob Wetterling Act). Although both community notification and sex offender registration have been implemented across the United States with varying degrees of compliance, neither policy has been evaluated except for one Washington State study that used a pre– post design to compare 90 adult sex offenders who were subject to the highest level of community notification and a matched group of 90 adult sex offenders who were released within 44 months prior to the implementation of the community notification law (Schram & Milloy, 1995). These investigators reported that community notification resulted in a quicker arrest once an individual had reoffended, but it had no impact on recidivism rates, with 19% of those who were subject to notification reoffending compared with 22% of those who were not. Almost two thirds of the new offenses occurred in the jurisdiction where notification took place, suggesting that notification did not necessarily cause offenders to go elsewhere if they were seeking opportunities to reoffend.

The policies of community notification and sex offender registration seem to be popular with the public despite the increase in fear or anxiety that appears to result from community notification and the absence of evidence on these policies’ impact on recidivism (Beck & Travis, 2004; Phillips, 1998). There may be negative effects on sex offenders of community notification and residency requirements, including harassment, loss of employment or residence, and property damage (J. Levenson & Cotter, 2005; Phillips, 1998). This may cause some sex offenders to avoid registration. Although concerns have been expressed about vigilante actions by angry citizens, few offenders have reported being physically assaulted as a result of their identity being disclosed (Matson & Lieb, 1996; Zevitz & Farkas, 2000).

Incapacitation

Dangerous offender legislation in Canada and sex offender civil commitment legislation in the United States permit the indeterminate incapacitation of high-risk individuals. Approximately one half of the designated dangerous offenders in Canada have been convicted of sexual offenses against children (Bonta, Harris, Zinger, & Carriere, 1996; Trevethan, Crutcher, & Moore, 2002). Approximately one half (49%) of civilly committed sex offenders had a diagnosis of pedophilia according to a recent survey of states with such laws (Fitch, 2003). Pedophilic sex offenders may be more likely to be recommended for civil commitment than nonpedophilic sex offenders (J. Levenson, 2004b).

These special legal options are much more expensive than regular incarceration. Fitch (2003) reported on a 2002 survey of states with civil commitment statutes and found that direct costs were approximately $100,000 per patient, more than 3 times the average cost of imprisonment alone (for a more recent and somewhat lower estimate of the costs associated with sex offender civil commitment, see Lieb & Gookin, 2005). Approximately 10% of sex offenders who underwent involuntary civil commitment have been released since the laws came into effect (Lieb & Gookin, 2005). Because of the high personal and public costs associated with indefinite incapacitation, accurate risk assessment is important to determine who should be subject to these measures (if such measures are to be used).

Prevention

Most of the interventions discussed in the previous sections take place after a sexual offense against a child has already occurred. In the next sections, I discuss prevention efforts intended to prevent sexual offenses against children.

Primary Prevention

Other than treatment or legal interventions, attempts can be made to reduce the incidence of child sexual abuse by investing in primary and secondary prevention programs (see Wortley & Smallbone, 2006). Primary prevention

refers to programs that are provided to all children, such as education campaigns about sexual abuse and strategies to avoid sexual abusers or disclose sexual abuse if it occurs; these kinds of primary prevention programs are typically school based. Other primary prevention programs focus on parent education and training (e.g., Wurtele, Currier, Gillispie, & Franklin, 1991).

A meta-analytic review concluded that school-based programs increase knowledge about sexual abuse and protection strategies, both on posttest and on follow-up (Rispens, Aleman, & Goudena, 1997). Moreover, one study suggested that participation in school-based programs is associated with a lower occurrence of sexual abuse later in life. Gibson and Leitenberg (2000) surveyed a sample of college-age women and found that those who had participated in school-based sexual abuse prevention programs were less likely to have been sexually abused later in life than those who had not. Although participants and nonparticipants were not randomly assigned to conditions, programs were implemented on a schoolwide basis, and there is no a priori reason to believe that children at some schools differed substantially in risk from children at other schools or that administrative decisions to introduce prevention programs were associated with knowledge of the risk to children at particular schools.

3

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention

programs focus on at-risk individuals, which could include persons who are likely to develop pedophilia, pedophiles who have not yet had sexual contact with children, and children who are vulnerable to having sexual contact with an adult because of their living circumstances or personal characteristics. One example is the education campaigns conducted by Stop It Now!, an American nonprofit organization that uses social marketing strategies to reach individuals who are at risk of committing sexual offenses against children to convince them to seek treatment and to encourage nonoffending adults to intervene if they suspect child sexual abuse may be occurring or might occur.

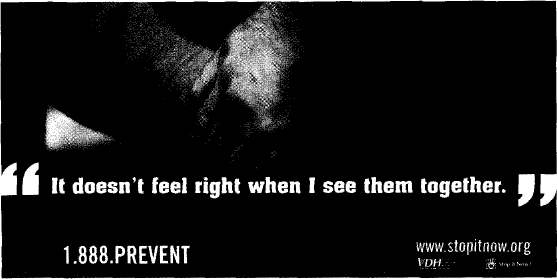

Figures 8.1

and

8.2

show the advertisements used in two of their recent campaigns conducted in Minnesota and Virginia, respectively.

Another innovative example of secondary prevention is the Berlin Prevention Project, which attempts to recruit pedophilic men, approximately one half of whom have committed undetected sexual offenses against children, to participate in treatment designed to help them refrain from engaging in sexual behavior involving children (see

Figures 8.3

and

8.4

). The Berlin Prevention Project provides a 1-year cognitive–behavioral program and sex-drive-reducing medication for some treatment clients. Among the men who reported having sexually offended against a child, a little over one half had contacts with five or more children. The Berlin Prevention Project addresses two gaps in the current responses to sexual offending against children. First, it tries to reach men who have committed sexual offenses but have not been investigated by police or child welfare agencies, which may not be possible under current legislation in countries like Canada and the United States because of their mandatory reporting requirements. Men who are facing legal proceedings as a result of sexual offending are excluded from the program. Second, like Stop It Now!, the Berlin Prevention Project tries to reach pedophilic men who are motivated to avoid committing sexual offenses against children. Some of these men would likely be able to do this on their own, given that they have been successful so far without formal assistance, but others might fail at a future date. The Berlin Prevention Project has run several groups and is currently collecting self-reported outcome data.

Figure 8.1

. Image from the Stop It Now! Minnesota campaign

Evaluations of these primary and secondary prevention efforts are needed. Both primary and secondary prevention programs might benefit from research on the tactics used by men to initiate sexual contact with children, and secondary prevention programs could also benefit from research on the factors that make some children more vulnerable than others.

Conte, Wolf, and Smith (1989) interviewed 20 adult men who reported that they were able to identify vulnerable children and to target these vulnerabilities in committing their sexual offenses. Vulnerabilities that the men identified included children who were particularly friendly and approachable; were living in a single-parent home; had been previously victimized; or were needy, unhappy, or depressed. The majority of offenders indicated that they formed relationships with these vulnerable children before initiating sexual contacts. Budin and Johnson (1989) interviewed 72 adult male sex offenders about prevention topics they thought could be effective. Of the 33 who responded to a question about the type of child they preferred, one half indicated they sought their own children or sought “passive, quiet, troubled, lonely children” from single-parent homes. In order of endorsement, these offenders indicated that prevention programs could be effective if they taught children how to disclose being sexually abused, say no to adults, learn about unacceptable touching of their genitals by others, avoid strangers, and run away if approached. Lang and Frenzel (1988) studied offenders against girls under the age of 14 and found that incest offenders and offenders against unrelated children used similar strategies overall but differed in the frequency of certain strategies; for example, incest offenders were more likely than offenders with unrelated child victims to commit their sexual offenses in the context of playing games or cuddling or by sneaking into the child’s bedroom.

The Modus Operandi Questionnaire was developed to assess offenders’ tactics for gaining sexual access to children (Kaufman et al., 1998; Kaufman, Hilliker, & Daleiden, 1996; Kaufman, Hilliker, & Lathrop, 1994; Kaufman, Hilliker, Lathrop, Daleiden, & Rudy, 1996). Kaufman et al. (1998) compared 114 adolescent sex offenders and 114 adult sex offenders, evenly divided into those who offended against related children and those who offended against unrelated children. Overall, sex offenders were more likely to use nonviolent tactics (provide alcohol or drugs, give gifts, and engage in physical play that led to sexual touching) than threat or force. Adolescent sex offenders were more likely than adult sex offenders to use pornography in their offenses or to use threat or force. Offenders against related children were more likely to use pornography or give gifts than offenders against unrelated children, whereas offenders against unrelated children were more likely to provide alcohol or drugs to the child before or during the sexual contacts.

Figure 8.2

. Image from the Stop It Now! Virginia campaign

Situational Prevention

The rationale of situational crime prevention is that potential offenders are influenced by the perceived benefits and risks of crime. Cornish and Clark (2003) have identified techniques for crime prevention that influence these perceptions by increasing the effort involved, increasing the potential risks, reducing the potential rewards, reducing situational provocations or triggers, and removing justifications or excuses. For example, school-based sexual abuse prevention programs can increase the effort involved and increase the potential risks of sexual offending by teaching children what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable touching and how to disclose their discomfort to trusted adults. As another example, shifting public attitudes so that adults who are suspicious that a sexual offense might have occurred are more willing to talk to the children they are concerned about could increase disclosure and early intervention.

Figure 8.3

. Image from the Berlin Prevention Project’s media campaign. Text translates as “Do you love children more than you/they like? There is help! Free of charge and confidential. Charité Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine.”

SUMMARY

The effectiveness of psychological treatments to reduce sex offender recidivism has not been convincingly demonstrated. There is support for the efficacy of behavioral conditioning techniques in decreasing pedophilic sexual arousal, but the long-term maintenance of such changes is unknown. It is possible that offenders can learn to control their sexual arousal, but the underlying sexual preference for prepubescent children (and motivation to engage in sexual behavior with children) may remain unchanged. Nonbehavioral treatments may actually be iatrogenic, increasing rather than decreasing the likelihood of new sexual offenses, and are therefore contraindicated in the treatment of pedophilia and sexual offending against children.

Most psychological treatments focus on self-management skills that will not be used by offenders who do not wish to refrain from further sexual contacts with children. External controls and prevention efforts are likely to be important components of a comprehensive response to the problem of child sexual abuse. Consistently using accurate risk assessments in decisions about sentencing and parole can reduce sexual recidivism because incapacitation prevents high-risk individuals from having access to children. Adequate supervision for those who are released to the community, as in the circles of support and accountability model, may also have a positive impact on recidivism, but further evaluations are needed. Finally, the existing evaluations of school-based prevention programs are encouraging, but as in other intervention areas reviewed in this book, more and better outcome studies are needed.

Figure 8.4

. The Berlin Prevention Project’s advertisement on a public pillar. “Do you love children more than you/they like? There is help! Free of charge and confidential. Charité Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine.”

Despite the intuitive appeal of pharmacological or surgical interventions to reduce sexual drive and thus the likelihood of sexual contacts with children by pedophilic sex offenders, the empirical support for the idea that such interventions can reduce sexual recidivism is not strong. Compliance is a major problem in antiandrogen treatment, with high refusal rates and high noncompliance rates, and studies have not been consistent in how this problem is handled in their statistical analyses. Some men who undergo surgical castration retain the ability to have erections and engage in intercourse, and many sexual offenses do not involve the penis; the majority of sexual offenses involve fondling, masturbation, or oral sex. Sex drive reduction (through either antiandrogen treatment or surgical castration) might not affect men who are romantically (not just sexually) attracted to children, feel affectionate toward them, and fulfill their intimacy needs by engaging in ongoing relationships with children. Moreover, although the surgical procedure is irreversible, one can obtain testosterone and reverse the physiological effects of castration. Finally, there is the danger of an inadvertent negative effect of pharmacological or surgical interventions because the belief that an offender’s sex drive has been reduced and therefore his risk to sexually reoffend has decreased may induce false confidence that other measures, such as longer sentences for high-risk offenders, investments in innovative supervision programs such as circles of support and accountability, or investment in sexual abuse prevention programs, can be eased. Similarly, the belief that sex offender treatment is effective could lead to the unintended consequence of increasing sexual offenses against children because higher risk offenders may be released from prison sooner after participating in treatment, even though such treatment actually has no impact on their subsequent behavior.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

I discuss future directions for sex offender practices and research in the following sections.

General Offender Research

Future developments in sex offender treatment could benefit greatly by drawing from the more established literature on correctional interventions (Andrews et al., 1990; Farrington & Welsh, 2005). Some psychological treatments are effective in reducing recidivism among offenders in general. Some treatment advocates have argued that sex offenders require specialized treatment (Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, Professional Issues Committee, 2005; W. L. Marshall, 2006a). However, of the four randomized clinical trials reviewed by Hanson et al. (2002), the two that showed positive effects for treatment evaluated programs that were designed for all kinds of offenders. Borduin, Henggeler, Blaske, and Stein (1990) produced a large positive effect size in a small sample of adolescent sex offenders, whereas Robinson (1995) produced a positive effect size for adult sex offenders who participated in a general offender program (but only reported data for general recidivism). Borduin and Schaeffer (2001) replicated the Borduin et al. (1990) study by showing that multisystemic therapy—a treatment approach for serious juvenile offenders that focuses on criminogenic risks, targeting problem solving and other skills rather than knowledge or abstract principles; involves multiple systems; and carefully attends to program fidelity—had a large impact on sexual recidivism in a different sample of 48 juvenile sex offenders, even though it was not designed specifically for this group. In contrast, the one randomized clinical trial of a specialized sex offender treatment (the SOTEP evaluation of a relapse prevention program) found no significant effect of treatment. These findings suggest that psychological treatments that target general dynamic risk factors associated with criminal behavior could have a positive impact on both sexual and general reoffending. These general dynamic risk factors—often referred to in the criminological and correctional literatures as

criminogenic needs

—include antisocial attitudes and beliefs, associations with antisocial peers, and substance abuse (for reviews, see Andrews & Bonta, 2006; Lalumière et al., 2005; Quinsey, Skilling, Lalumière, & Craig, 2004). Given the important role of such factors in sexual offending against children, as discussed in

chapter 4

, it is probable that the foundation of any effective sex offender treatment program will be the techniques and skills that have been demonstrated to be effective in general offender outcome research.

Risk, Need, and Responsivity Principles

Correctional research has demonstrated that offender treatments are more effective to the extent that their intensity is matched to risk, that they target criminogenic needs, and that they are matched to the individual’s learning style and capacity (Andrews & Bonta, 2006). As reviewed in

chapter 7

, sex offender risk assessment has advanced greatly in the past decade, and a number of empirically and independently validated actuarial risk scales have been developed (Hanson, Morton, & Harris, 2003; Seto, 2005). Using these risk scales could greatly increase the accuracy and efficiency of decisions about treatment intensity and type.

The risk principle

suggests that the intensity of intervention should be matched to the offender’s risk for recidivism (Andrews & Bonta, 2006). The most intensive services should be directed at higher risk offenders, whereas lower risk offenders should be assigned to minimal levels of service. Treatment of low-risk offenders is not cost-effective (given the limits on resources such as staff time, money, and space) because these offenders are already unlikely to reoffend. There is little room for improvement, and there is the possibility of inadvertent negative effects, for example, when low-risk offenders are exposed to the antisocial attitudes and beliefs of high-risk offenders in group therapy or other contacts (see Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999). In the context of sex offender treatment, this could mean combining incest offenders with sex offenders against unrelated children or combining sex offenders against children with sex offenders against adults. Following the logic of the risk principle, some sex offenders do not require treatment because they are already at low risk for recidivism. Significant impacts will be achieved only by focusing on higher risk offenders. The typical practice, however, is to prescribe treatment for all sex offenders (Mailloux et al., 2003), even for those who are very low in risk to reoffend, and some treatment advocates have suggested that it would be unethical to refuse treatment to any sex offenders who are willing to take it (W. L. Marshall, 2006a).

There is some evidence that the risk principle is influencing sex offender practices. Sex offender treatment standards were established in Canadian federal corrections in 2000, and these standards prescribe different amounts of treatment according to offender risk level. High-intensity programs provide between 360 and 540 hours of treatment; moderate-intensity programs provide between 160 and 200 hours of treatment; and low-intensity programs provide between 24 and 60 hours of treatment (see W. L. Marshall & Yates, 2005). Similar sex offender treatment standards have been established in the United Kingdom. At the same time, W. L. Marshall and Yates pointed out that correctional practices allow for the adjustment of treatment plans such that sex offenders who score in the middle range of an actuarial risk scale might still be placed in a high-intensity program because they show pedophilic sexual arousal or have high scores on measures of psychopathy. No examples are given of sex offenders being placed in lower intensity programs than indicated by their actuarially estimated risk. Even with implementation of these standards, it is likely that some sex offenders are being overprescribed treatment relative to their risk to reoffend, as Mailloux et al. (2003) have argued.

The needs principle

suggests that interventions are more likely to have a significant impact when they target changeable factors associated with recidivism, such as antisocial attitudes, beliefs, and values; substance abuse; and self-regulation skills, in contrast to noncriminogenic needs, such as poor self-esteem, anxiety or mood problems, and subjective distress (Hanson & Bussière, 1998; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004).

Finally, the responsivity principle

recognizes that treatments are more likely to be effective when tailored to the individual’s learning style and capacity. This often includes the use of behavioral and social learning techniques that involve modeling prosocial behavior, graduated rehearsal of problem solving and other skills, role-playing, and reinforcement. More is known about risk factors and treatment needs than the factors that influence offender responsivity. The sex offender field might benefit by drawing from the general therapy literature on responsivity and the influence of therapist characteristics such as warmth, a nonconfrontational style, encouragement and rewards for treatment progress, and directiveness in therapeutic interactions on therapeutic alliance and treatment impact (see Kirsch & Becker, 2006; W. L. Marshall et al., 2005).

Efficacy Versus Effectiveness

An important conceptual distinction needs to be made between efficacy and effectiveness, addressing the questions “Can treatment work?” and “Does treatment work?” respectively (for further discussion of this distinction, see Rice & Harris, 2003). The first stage involves rigorous research designs, with random assignment of participants to treatment and control conditions, the use of placebo conditions, multiple outcome measures, multiple exclusion criteria leading to homogeneous groups, manualized therapy, and attention to program implementation and fidelity. Once it is established that treatment can have a positive impact (efficacy), smaller studies evaluate the ability of treatment to have an effect in typical practice, outside the research setting and in the hands of staff dealing with high caseloads, resource limitations, variable training, and so forth (effectiveness). Rice and Harris (2003) have pointed out that the sex offender treatment field has focused on the second question before the first question has been adequately addressed.

In addition to the impact of intervention on recidivism, one can also evaluate the cost-effectiveness of intervention programs by estimating the financial costs of providing the intervention relative to the alternatives and then factoring in the financial costs of new offenses that occur (e.g., Aos, Lieb, Mayfield, Miller, & Pennucci, 2004; Aos, Phipps, Barnoski, & Lieb, 2001).

4

Some interventions may indeed reduce recidivism but at a cost that far exceeds the costs of alternative options. To use an extreme hypothetical example, sex offenders living in the community could be accompanied by an around-the-clock surveillance team. With eight staff (three shifts of two members each with an additional two staff in case of illness, holidays, and other absences) at a cost of $40,000 (comparable to the median salary of probation officers in the United States) per staff person, an offender would be extremely unlikely to reoffend against a child, but he would require millions of dollars in direct personnel costs over his lifetime. Applying this extremely high level of monitoring for every sex offender released from correctional custody would quickly exhaust the financial resources of the criminal justice system. Langan, Schmitt, and Durose (2003) estimated that approximately 6,400 sex offenders against children were released from state prisons in 1994; these offenders would require $2 billion a year under this surveillance team system.