APPENDIX 8.1

INTERPRETING SEX OFFENDER TREATMENT PERFORMANCE

In addition to methodologically rigorous treatment evaluations, researchers can draw from studies that have examined the relationship between sex offender treatment performance and outcome. If sex offender treatment has an effect, one would expect good treatment performance to be related to better treatment outcome. In other words, one would expect sex offenders who learn more and do better in a treatment program to be less likely to reoffend, if the knowledge and skills they learn are relevant to recidivism, than those who learn less or perform poorly.

A number of studies have examined the relationship between aspects of treatment performance and outcomes among sex offenders participating in programs espousing cognitive–behavioral or relapse prevention principles. Almost all of these studies have examined treatment performance as a static risk factor. Four studies found no relationship, one found a positive relationship, and three found a negative relationship. Jenkins-Hall (1994) assessed acceptance of responsibility, attendance, and level of participation in therapy sessions to predict mastery of program content in a sample of sex offenders. These aspects of treatment performance predicted proficiency with the principles and concepts of rational–emotive therapy but did not predict proficiency with the principles and concepts of relapse prevention. Quinsey, Khanna, and Malcolm (1998) reported on a follow-up study of sex offenders treated at the Regional Treatment Centre, a prison-based program in Canada, and found that a clinician rating of treatment gain was unrelated to sexual recidivism among 193 treated sex offenders, even though treated sex offenders showed significant improvements on within-treatment measures.

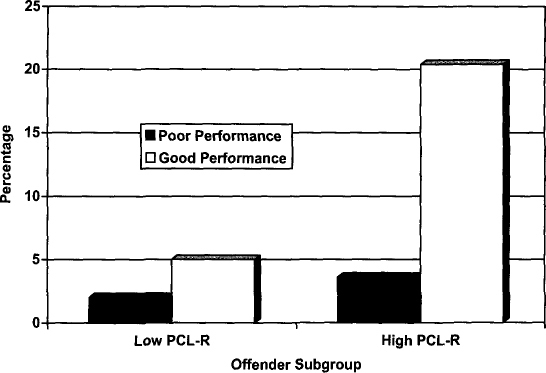

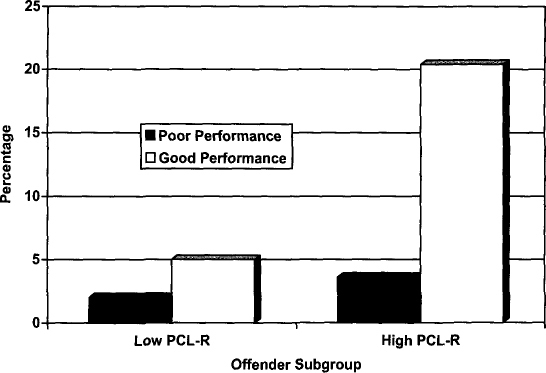

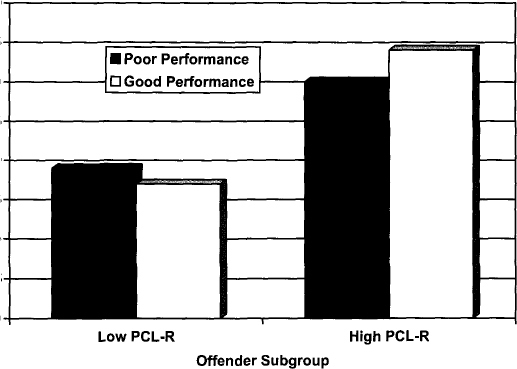

FIGURE 8A.1

Rates of violent recidivism among treated sex offenders after an average follow-up period of 32 months. These offenders were followed to November 1996, using federal agency recidivism data (Seto & Barbaree, 1999). Offenders were divided into groups according to median splits on PCL–R and treatment performance scores. PCL–R = Psychopathy Checklist—Revised. From Managing Sex Offenders in the Community: Contexts, Challenges, and Responses

(p. 133), A. Matravers (Ed.), 2003. London: Willan. Copyright 2003 by Willan. Reprinted with permission of the author.

In terms of a positive relationship, SOTEP participants who obtained lower posttreatment scores on phallometrically measured sexual arousal and attitudes and beliefs about sexual offending and positive ratings of their relapse prevention assignments were less likely to reoffend than those who did not obtain encouraging posttreatment scores, even after statistically controlling for actuarially estimated risk to reoffend (Marques et al., 2005). These results were consistent with those previously reported for a smaller sample of child sexual abusers who participated in SOTEP (Marques et al., 1994).

In terms of a negative relationship, Sadoff, Roether, and Peters (1971) found that sex offenders who reported that group psychotherapy was helpful when asked at the end of treatment were more, rather than less, likely to be rearrested than sex offenders who complained about their involvement in group therapy. Seto and Barbaree (1999) found that contrary to their prediction, good treatment performance was not associated with lower rates of recidivism during the average follow-up period of 32 months. In fact, good treatment performance was associated with higher rates of recidivism. This was especially true among individuals scoring higher in psychopathy.

7

Men who scored higher on psychopathy on the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised (PCL–R; Hare, 1991, 2003) and who performed well in treatment were almost 4 times as likely to commit a new violent offense, defined as a new nonsexually violent or new violent sexual offense, during the follow-up (see

Figure 8A.1

). This was an intriguing finding because other studies have found that psychopathic offenders appear to be negatively affected by treatment, whereas nonpsychopathic offenders benefit (Hare, Clark, Grann, & Thornton, 2000; Rice, Harris, & Cormier, 1992).

The Seto and Barbaree (1999) measure of treatment performance included items tapping nonspecific aspects such as the offender’s attendance, level of participation in therapy, and interactions with others during group sessions as well as items tapping specific aspects of skills and knowledge acquisition, including quality of homework assignments in victim empathy exercises, understanding of offense cycle, and development of a relapse prevention plan. The measure also included therapist ratings of motivation for treatment and overall behavior change. Except for the two therapist ratings, the items on our measure were coded by research assistants on the basis of clinical notes kept by the therapists and the original written homework assignments completed by the offenders, so the results we observed cannot be explained by successful deception of therapists by psychopathic sex offenders.

Looman, Abracen, Serin, and Marquis (2005) recently reported similar results in a different sample of convicted sex offenders treated at a correctional psychiatric center (Regional Treatment Centre) using a PCL–R cutoff score of 25 for identifying psychopaths. They also found that men who performed well in treatment in terms of ratings of change in victim empathy, understanding of offense cycle, quality of relapse prevention plan, and global performance and who scored higher in psychopathy were more likely than other offenders in the sample to reoffend seriously during the follow-up period of 4 to 5 years.

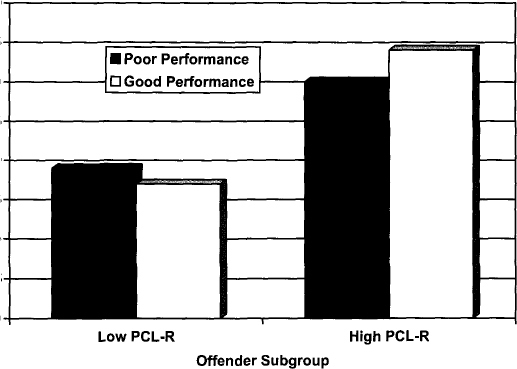

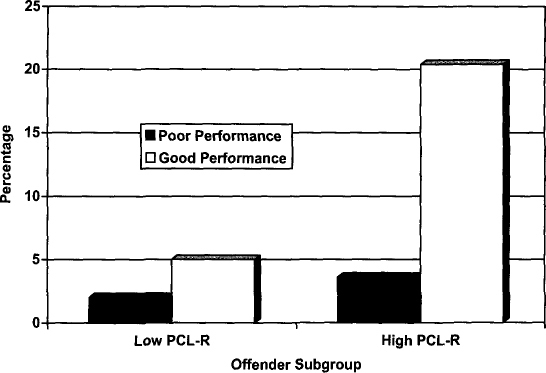

Barbaree and I have since extended the follow-up of the sex offender sample studied by Seto and Barbaree (1999), almost doubling the average time at risk in the community from 32 to 62 months, to determine if the relationship between treatment performance and recidivism held up over time and to determine if the effect was still apparent after almost all of the offenders were no longer under any form of parole supervision (Barbaree, 2005; Seto, 2003). In the latest follow-up, treatment performance was not related to either general or violent recidivism (see

Figure 8A.2

). As in Seto and Barbaree (1999), sex offenders who scored higher in psychopathy were approximately twice as likely to reoffend violently as sex offenders who scored lower in psychopathy. Another follow-up study of a larger sample of sex offenders assessed at the same clinic also found that psychopathy, but not treatment performance, was significantly related to violent recidivism (Langton, Barbaree, Seto, Harkins, & Peacock, 2002). These results suggest that many of the treatment targets of relapse prevention programs are not necessary components of effective treatment.

FIGURE 8A.2

Rates of violent recidivism among treated sex offenders after an average follow-up period of 62 months. These offenders were followed to April 2000, using national recidivism data. Offenders were divided into groups according to median splits on PCL–R and treatment performance scores. PCL–R = Psychopathy Checklist—Revised. From Managing Sex Offenders in the Community: Contexts, Challenges, and Responses

(p. 132), A. Matravers (Ed.), 2003. London: Willan. Copyright 2003 by Willan. Reprinted with permission of the author.