2

ASSESSMENT METHODS

Valid methods of assessing sexual interest in children are needed to study pedophilia scientifically. In this chapter, I review methods for assessing pedophilia. I focus in particular on the measurement of penile responses (

phallometry

) to sexual stimuli in the laboratory, because many of the key studies on pedophilia have used this psychophysiological method, and it has the best validity for assessing pedophilic sexual interests. I also discuss assessment methods based on self-report (interview or questionnaire), behavior (sexual offense history or performance on laboratory tasks), and viewing time. I then suggest future directions for assessment research and discuss implications of assessment research for the understanding of pedophilia. The specific assessment question of how to determine an individual’s risk for committing a sexual offense involving a child is discussed in

chapter 7

.

SELF-REPORT

The utility of self-report will depend on the assessment context. Nonforensic evaluators will see individuals who are concerned about their sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, or behavior regarding children, whereas forensic evaluators are more likely to see someone referred by mental health, social service, or criminal justice agencies because of alleged sexual contacts with children. Forensic evaluators benefit from the availability of collateral information such as previous assessment reports and criminal records, but at the same time the individuals they see will likely be reluctant to disclose pedophilic thoughts, fantasies, urges, or behavior. Nonforensic evaluators usually do not have the same level of access to collateral information, but they can often obtain more information through self-report as the client is self-referred and presumably more willing to talk about their sexual interests.

Clinical Interviews

Sexual histories are typically obtained through clinical interview (see

Resource A

, this volume). Respondents are asked questions pertaining to their sexual thoughts, interests, and behaviors, especially with regard to children. Men who have committed sexual offenses against children are asked about the details of these crimes. Pedophilia can be diagnosed after a careful consideration of the person’s entire sexual history. For example, someone who acknowledges having frequent and intense fantasies about having sex with children, collects and masturbates to media depicting children, and engages in repeated sexual acts involving children would clearly meet the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(4th ed., text revision;

DSM–IV–TR

; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Self-reported sexual interest in children is informative and related to the likelihood that someone will sexually reoffend (e.g., Worling & Curwen, 2000).

Interviewers often ask questions about social contacts with children through family, friends, and neighbors and about employment that involves close proximity to children. It is assumed that men who have limited sexual contacts with adults and a high level of emotional and social affinity for children are more likely to be pedophiles (e.g., Finkelhor & Araji, 1986). There is some support for this idea; for example, the number of adults with which a man has had sexual contacts is inversely related to the amount of sexual arousal he exhibits to stimuli depicting children in the laboratory, suggesting that pedophiles tend to have fewer sexual contacts with adults (Blanchard, Klassen, Dickey, Kuban, & Blak, 2001). In addition, many self-identified pedophiles have never been married, and those who are married report having poor sexual relationships with their spouses (Bernard, 1985; Rouweler-Wuts, 1976).

Comprehensive interviews also include questions to help clinicians rule out other explanations for sexual thoughts, urges, fantasies, or behavior involving children. For example, some individuals with obsessive–compulsive disorder may report being disturbed by thoughts about molesting a child (Freeman & Leonard, 2000; W. M. Gordon, 2002). The differential diagnosis is made by determining if the thoughts are associated with sexual arousal or pleasure instead of anxiety or disgust and by inquiring about other symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Interviews can be informative, but there are potential problems with recall and other report biases in gathering data on sexual behavior in this way (for a review of research on the impact of self-report methods to study sexuality, see Wiederman, 2002). With regard to violent behavior, Hilton, Harris, and Rice (1998) used anonymous reports of aggression and found that the average number of violent incidents in the past month reported by a randomly selected sample was equal to the average number of violent incidents reported in the past year by another randomly selected sample. The respondents were not necessarily lying; instead, the logical implausibility of equal estimates over the past month and over the past year might have been due to selective memory or other reporting effects.

Offenders may lie because of the obvious nature of the questions and the legal or social sanctions they could face in acknowledging illegal sexual behavior. Many jurisdictions have mandatory reporting laws regarding the occurrence of child sexual abuse that can constrain what offenders can disclose without guarantees of confidentiality that protect the information they reveal from being used against them in criminal or civil proceedings. Moreover, whether as a result of unconscious self-deception or a conscious effort to present oneself in a socially desirable manner, many sex offenders minimize or deny their pedophilic sexual interests and behavior (e.g., G. T. Harris, Rice, Quinsey, & Chaplin, 1996; Kennedy & Grubin, 1992).

These limitations of self-report are not unique to sex offenders or offenders in general: Questions about sexual history are sensitive, and many interviewees may minimize or deny certain sexual interests or behaviors. For example, male adolescents are more willing to disclose criminal acts they have committed than the fact that they have masturbated, even though many of them have engaged in both (Halpern, Udry, Suchindran, & Campbell, 2000).

Questionnaires

One way to reduce the reluctance of individuals to disclose sexual interests or behavior in face-to-face interviews is to administer questionnaires, either on paper or by computer. For example, Koss and Gidycz (1985) found that male respondents were more likely to admit sexually coercive acts in a questionnaire than in interviews. Using questionnaires also addresses the potential problem of interviewers who skip or forget important questions about conventional and atypical sexual interests.

A number of questionnaires have items to assess pedophilia, including the Clarke Sexual History Questionnaire—Revised (Langevin & Paitich, 2001), the Multiphasic Sex Inventory (Nichols & Molinder, 1984), and the Sexual Fantasy Questionnaire (Daleiden, Kaufman, Hilliker, & O’Neil, 1998). The Clarke Sexual History Questionnaire—Revised is intended for adults and contains 508 items tapping different aspects of conventional and paraphilic sexuality, including early childhood experiences, sexual dysfunction, fantasies, exposure to pornography, and behavior. The Sexual Fantasy Questionnaire has been administered to adolescents and contains items about sexual fantasies involving sex with children under the age of 12 as well as items about other atypical sexual fantasies. The Multiphasic Sex Inventory contains 200 items organized into 20 scales pertaining to different aspects of conventional and paraphilic sexuality, including 6 validity scales and a scale assessing attitudes regarding treatment.

The Sexual Interest Cardsort Questionnaire contains 75 descriptions of explicit sexual acts that are relevant to different paraphilia diagnoses. Respondents rate each description on a 7-point scale in terms of their sexual interest in it. The measure is called a cardsort

because it was originally developed as a set of cards that were sorted by respondents. Holland, Zolondek, Abel, Jordan, and Becker (2000) reported that cardsort questionnaire responses were significantly correlated with group classifications made by clinicians in a sample of 371 men seeking assessment or treatment because of their paraphilic interests or sexual offending. Laws, Hanson, Osborn, and Greenbaum (2000) reported that the cardsort questionnaire could distinguish between offenders who victimized only boys from offenders who victimized only girls.

Like interviews, questionnaires are vulnerable to self-report biases, although the Clarke Sexual History Questionnaire—Revised and the Multiphasic Sex Inventory contain validity scales to detect lying. There are published data regarding the psychometric properties of the Clarke Sexual History Questionnaire—Revised (Curnoe & Langevin, 2002; Langevin, Lang, & Curnoe, 2000) and the Multiphasic Sex Inventory (Day, Miner, Sturgeon, & Murphy, 1989; Kalichman, Henderson, Shealy, & Dwyer, 1992; Simkins, Ward, Bowman, & Rinck, 1989), but there are no studies on the predictive validity of these questionnaires. Many other questionnaires in clinical use have not been empirically validated. Because of concerns about the limitation of self-reports, there is a great deal of clinical and research interest in measures that draw on other sources of information.

BEHAVIOR

Information about past behavior that does not rely on self-report is useful in evaluations when the individual is unwilling to disclose pedophilic thoughts, fantasies, urges, arousal, or behavior. In forensic evaluations of sex offenders, information about past sexual offenses is particularly helpful. Moreover, recent research has identified laboratory tasks from the cognitive science field that can shed light on a person’s sexual interests.

Sexual Offense Characteristics

Clinicians have used information about sexual victim characteristics that are empirically related to pedophilic sexual interests to make the diagnosis of pedophilia. Among adult sex offenders with child victims, those who have multiple victims, very young victims, boy victims, or victims outside the offender’s immediate family are more likely to be pedophilic than those who do not. This information has typically been combined in a subjective and unstructured fashion in clinical judgments. In response, a colleague and I developed a four-item scale, the Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests (SSPI), to summarize an offender’s sexual victim characteristics and identify those who were more likely to be pedophilic in their sexual arousal patterns (Seto & Lalumière, 2001). The SSPI was developed in a large sample primarily of adult men who had been convicted of at least one sexual offense against a child (

N

= 1,113 offenders, including 40 adolescent sex offenders). Four easily coded correlates of pedophilia that were identified from the empirical literature independently contributed to the prediction of phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children. Having boy victims explained approximately twice the variance in sexual arousal and thus was given twice the weight of the other variables. These four variables were scored as present or absent, using all available information about sexual offenses: having any male victims, having more than one victim, having a victim aged 11 or younger, and having an unrelated victim (see

Resource A

,

Table 2

). Total SSPI scores range from 0 to 5. An offender scoring 5 would have multiple child victims, at least one of them male, at least one of them 11 years old or younger, and at least one of them unrelated to him; in contrast, an offender scoring 0 would have a single victim, a related girl who was 12 or 13 years old. File information such as police synopses or probation or parole reports is preferred over self-report as a means of obtaining information about sexual offense history, unless the individual reported sexual offenses that were not previously known.

Sex offenders who have higher scores on the SSPI are much more likely to be pedophilic than are offenders with lower scores (see

Figure 2.1

). Approximately 1 in 5 sex offenders with a score of 0 showed greater sexual arousal to children than to adults when assessed phallometrically, whereas almost 3 in 4 sex offenders with a score of 5 showed this pattern of sexual arousal. Recent studies have demonstrated that the SSPI is also valid for adolescent sex offenders with child victims (Madrigano, Curry, & Bradford, 2003; Seto, Murphy, Page, & Ennis, 2003). Moreover, SSPI scores predict new serious (nonsexually violent or sexual) offenses among adult male sex offenders with child victims (Seto, Harris, Rice, & Barbaree, 2004); however, the SSPI might not accurately predict sexual offenses among adolescent sex offenders (Fanniff & Becker, 2005).

Figure 2.1

. Sexual victim characteristics and likelihood of responding equally or more to children than to adults in phallometric testing.

A potential problem with using measures based on sexual victim characteristics is that first-time offenders may not yet have a history that reflects their pedophilia. However, a recent study found that the SSPI correlated with recidivism among first-time offenders as well as it did for repeat offenders in two different samples (Seto et al., 2004). Moreover, the scale is valid for adolescent sex offenders who have had less time to accumulate a sexual offense history that reflects their sexual interests. These results suggest that even the choice of a first child victim is influenced by whether the offender is pedophilic.

Laboratory Tests

Polygraphy and phallometry are reviewed in the next section, Psychophysiological Measures. Research on other tasks pertaining to behavioral responses in the laboratory is reviewed here, beginning with viewing time measures (sometimes referred to as visual reaction time measures

in the clinical literature).

Unobtrusively recorded viewing time has been correlated with self-reported sexual interests and phallometric responding in samples of nonoffending male volunteers recruited from the community (Quinsey, Ketsezsis, Earls, & Karamanoukian, 1996; Quinsey, Rice, Harris, & Reid, 1993). The basic viewing time procedure for assessing age preferences involves showing a series of pictures depicting girls, boys, women, or men; these pictures can depict clothed, semiclothed, or nude figures. Respondents are either asked to examine the pictures to answer questions later or they are asked to rate each picture on certain attributes (e.g., how attractive the person is and how sexually interesting he or she is). Respondents are instructed to proceed to the next picture at their own pace and are supposed to be unaware that the key dependent measure is the amount of time they spend looking at each picture.

Several studies have shown that adult sex offenders with child victims can be distinguished from other men by the amount of time they spend looking at pictures of children relative to pictures of adults (G. T. Harris et al., 1996) or by a combination of viewing time and self-reported sexual interests, arousal, and behavior (Abel, Jordan, Hand, Holland, & Phipps, 2001; Abel, Lawry, Karlstrom, Osborn, & Gillespie, 1994). Viewing time can also distinguish sex offenders with boy victims from those with only girl victims (Abel et al., 2004; Abel, Huffman, Warberg, & Holland, 1998; Worling, 2006). However, G. Smith and Fischer (1999) were not able to demonstrate discriminative validity in a study of adolescent sex offenders and nonoffenders using the viewing time component of the Abel Assessment of Sexual Interests. No published studies have yet demonstrated that scores on such viewing time measures, whether alone or in combination with self-reports, predict recidivism among sex offenders.

A potential problem for viewing time measures is that they may become vulnerable to faking once the client learns that viewing time is the key variable of interest (e.g., see

http://www.innocentdads.org/abel.htm

). No published studies have reported on the ability of participants to fake their responses on viewing time measures or the ability of examiners to detect such efforts.

A choice reaction time task was described by Wright and Adams (1994, 1999). In this procedure, participants are instructed to locate a dot that appears on slides of nude men and women as quickly as possible. In both studies, heterosexual and homosexual male and female volunteers took longer to react to the appearance of the dot when examining a picture of someone of their preferred sex (women for heterosexual men and homosexual women, and men for heterosexual women and homosexual men). Gaither (2001), however, found that scores on a choice reaction time task did not correlate highly with self-reported sexual arousal or phallometric responses in a sample of college men. No researchers have yet reported whether choice reaction time can distinguish pedophilic individuals from others while they view pictures of children or adults.

P. Smith and Waterman (2004) examined the utility of a modified Stroop task to distinguish among sex offenders, violent offenders, and nonoffenders. In the P. Smith and Waterman task, participants had to name the colors in which different words—sexual, violent, or neutral in their meaning—were printed. Sex offenders were distinguished from the violent offenders and nonoffenders in their response latencies to sexual words. Sex offenders against adults and sex offenders against children did not differ in their responses to sexual words but did differ in their responses to violent words. This modified Stroop task might be further refined by including more words associated with children or associated with adults.

As another example of a laboratory task adapted from the cognitive science field, Beech and Kalmus (2004) described a rapid serial visual presentation task in which pictures of clothed children or an animal (comparison object) were embedded in a rapidly presented sequence of ordinary images, followed by a choice task (whether a target object had appeared and whether it faced left or right). Compared with nonoffenders, sex offenders with child victims made more errors in the task of identifying whether the target object had appeared and whether it faced left or right when the target image was presented in a series that included an image of a child.

There is a rich cognitive science literature on laboratory tasks that could be drawn on to increase the methods available to assess pedophilia (see Kalmus & Beech, 2005). Recent articles have discussed the use of cognitive science methods such as the implicit association task to study sexuality (Spiering, Everaerd, & Laan, 2004; Treat, McFall, Viken, & Kruschke, 2001). Ideally, these laboratory tasks would be unobtrusive, inexpensive, difficult to fake, and reveal information about pedophilia not tapped by current assessment methods. For example, people are faster at detecting an angry face in a crowd of happy faces than a happy face in a crowd of angry faces, reflecting a preparedness in our visual information processing regarding the emotions of others (the face-in-the-crowd effect

; C. H. Hansen & Hansen, 1988; Öhman, Lundqvist, & Esteves, 2001). A similar paradigm might be able to detect a preparedness in the visual information processing of pedophiles such that they differ from nonpedophilic individuals in the speed with which they identify a young-looking face in a crowd of mature faces versus a mature face in a crowd of young-looking faces or a vulnerable-looking child’s face in a crowd of confident faces versus a confident child’s face in a crowd of vulnerable-looking faces.

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MEASURES

In addition to information about past sexual offenses, forensic evaluators in particular often seek objective information about an individual’s sexual interests. In this section, I discuss polygraphy, which is used to increase the validity of self-report, and phallometry, which is used to measure sexual arousal to stimuli presented in controlled laboratory conditions.

Polygraphy

Polygraphy is a psychophysiological method for assessing changes in heart rate, blood pressure, skin conductance, and respiration while participants are asked specific questions about their behavior. Polygraphy is not a method for assessing sexual interests per se, but it is being used as a method to check the validity of self-reported information.

There are two main types of polygraph test: the control question test

and the guilty knowledge test

. In the control question test, participants are asked relevant questions about their behavior (such as their sexual offense history or their involvement in potentially risky activities such as spending time alone with children) and control questions about neutral topics. It is assumed in this type of test that deceptive individuals will react more strongly to relevant questions than to control questions in terms of physiological parameters such as breathing rate, heart rate, and skin conductance. In the guilty knowledge test, participants are asked questions about the specific details of a crime that are thought to be known only to investigators and the person who committed the crime. It is assumed in this test that participants will respond more strongly to questions containing relevant information about the crime than to control questions.

The control question test is more commonly used than the guilty knowledge test in the polygraphic assessment of sex offenders. More than half of the probation and parole agencies responding to a nationwide American survey reported regularly using polygraph testing to monitor the treatment and supervision compliance of sex offenders living in the community under their jurisdictions (English, Jones, Pasini-Hill, Patrick, & Cooley-Towell, 2000). In different versions of the control question test, offenders are questioned about their past offenses, officially unknown victims, sexual thoughts and fantasies, and current behavior.

There is little methodologically strong research on the accuracy of polygraph testing (for a discussion of polygraphy testing of sex offenders under supervision, see Lalumière & Quinsey, 1991; for a recent literature review, see National Research Council, Committee to Review the Scientific Evidence on the Polygraph, 2003). There is some empirical support for the validity of the guilty knowledge test, but this test is unlikely to be of much assistance in assessing pedophilic behavior or monitoring treatment and supervision compliance. The validity of polygraph testing as it is commonly used in sex offender assessment has not been established. Nonetheless, some research suggests that offenders who undergo polygraph testing report more victims and offenses than are officially known (Ahlmeyer, Heil, McKee, & English, 2000; Emerick & Dutton, 1993; Hindman & Peters, 2001).

It is possible that polygraph testing can increase disclosures through its operation as a “bogus pipeline” technique (for a review, see Roese & Jamieson, 1993). In this technique, participants are connected to a nonfunctioning machine that they are told can detect deception. Once connected to the machine, participants reveal more information than they would otherwise. One outcome that is rarely discussed in the polygraphy literature is the possibility that polygraph testing may induce false disclosures. The false confession literature suggests that individuals who are suggestible and lower in intelligence would be more likely to make false disclosures, especially in conjunction with coercive interrogation techniques (see Kassin, 2005).

Phallometry

Phallometry involves the measurement of penile responses to stimuli that systematically vary on the dimensions of interest, such as the age and sex of the figures in a set of pictures depicting female children, adolescents, and adults and male children, adolescents, and adults. Phallometry was developed as an assessment method by Kurt Freund, who first showed that it could reliably discriminate between homosexual and heterosexual men (Freund, 1963) and then showed it could distinguish between sex offenders against children and other men (Freund, 1967).

Phallometric responses are recorded as increases in either penile circumference or penile volume; bigger increases in circumference or volume are interpreted as greater sexual arousal to the presented stimulus. Circumferential gauges, typically a mercury-in-elastic strain gauge placed over the midshaft of the penis, are the most commonly used phallometric devices (see

Figure 2.2

). Changes in the electrical conductance of the mercury represent changes in penile circumference and can be calibrated to give a precise measure of penile erection. Erectile response (except for erections that occur during sleep) is a specifically sexual measure, unlike other psychophysiological responses such as pupillary dilation, heart rate, viewing time, and skin conductance (Zuckerman, 1971). Phallometric responses correlate positively and significantly with viewing time and self-report among nonoffenders (G. T. Harris et al., 1996) and with a measure based on both viewing time and self-report among sex offenders (Letourneau, 2002).

Phallometric data are optimally reported as the relative response to the category of interest, for example, penile response to pictures of prepubescent children minus penile response to pictures of adults; more positive scores indicate greater sexual interest in children. Relative responses are more informative because they take individual differences in responsivity into account, unlike absolute penile responses (such as millimeters of change in penile circumference to child stimuli). Responsivity can vary for a variety of reasons, including the man’s age, health, and the amount of time since he last ejaculated. To illustrate the value of relative response, the observation that an individual exhibits a 10-millimeter increase in penile circumference in response to pictures of children is more interpretable when we know whether he exhibits a 5-millimeter or 20-millimeter increase in response to pictures of adults. The first pattern of responses is from someone who is more sexually aroused by pictures of children compared with pictures of adults, indicating a sexual preference for children; the second pattern of responses is from someone who is relatively more responsive in the laboratory, but who is more sexually aroused by pictures of adults relative to pictures of children, indicating a sexual preference for adults. More details about phallometric testing are provided in

Resource A

.

Figure 2.2

. Circumferential gauge for phallometric testing.

Discriminative Validity

Indices of relative phallometric responding can significantly discriminate sex offenders against children from other men. Using a differential index (average response to stimuli depicting children minus average response to stimuli depicting adults), sex offenders with child victims respond relatively more to stimuli depicting children than do men who have not committed such sexual offenses, including sex offenders with adult victims, nonsex offenders (e.g., men convicted of nonsexual assault), and nonoffenders (e.g., Barbaree & Marshall, 1989; Freund & Blanchard, 1989; Quinsey, Steinman, Bergersen, & Holmes, 1975). Moreover, phallometric responses are associated with victim choice, so that men who have offended against girls tend to respond relatively more to stimuli depicting girls, and those who have offended against boys tend to respond relatively more to stimuli depicting boys (G. T. Harris et al., 1996; Quinsey et al., 1975). Rapists respond relatively more to depictions of sexual aggression than nonrapists (for a quantitative review, see Lalumière & Quinsey, 1994; for a recent update, see Lalumière, Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Trautrimas, 2003), and other investigators have shown that phallometry can distinguish men who admit to sadistic fantasies, cross-dressing, or exposing their genitals in public from men who do not (Freund, Seto, & Kuban, 1996; W. L. Marshall, Payne, Barbaree, & Eccles, 1991; Seto & Kuban, 1996). Phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children is the most reliably identified characteristic that distinguishes sex offenders with child victims from other men.

The discriminative validity of phallometry can be improved in several ways. Using standardized scores to calculate indices of relative responding and using indices based on differences in the responses to different stimulus categories can increase discrimination between sex offenders and other men (Earls, Quinsey, & Castonguay, 1987; G. T. Harris, Rice, Quinsey, Chaplin, & Earls, 1992). The addition of a semantic tracking task that requires offenders to push buttons when they see or hear violent or sexual content reduces faking (by individuals who are not paying attention to the stimuli) and subsequently increases the discriminative validity of phallometry for sex offenders (G. T. Harris, Rice, Chaplin, & Quinsey, 1999; Proulx, Côté, & Achille, 1993; Quinsey & Chaplin, 1988). Response artifacts can also be used to detect attempts to manipulate test results (Freund, Watson, & Rienzo, 1988). Tactics to reduce faking are important in phallometric testing, because some men can voluntarily control their penile responses during phallometric testing (Quinsey & Bergersen, 1976; Quinsey & Carrigan, 1978). The use of audiotaped descriptions of sexual scenarios also yields very good discrimination (Chaplin, Rice, & Harris, 1995; Quinsey & Chaplin, 1988).

At the level of individual diagnosis, the sensitivity of phallometric tests, defined as the proportion of sex offenders with child victims identified as pedophilic on the basis of their phallometric responses, can be calculated after setting a suitable cutoff score (there is no gold standard for identifying someone as a pedophile, although showing greater arousal to children than to adults is often used as a cutoff in research studies). This is a conservative approach to estimating sensitivity, because not all sex offenders with child victims are pedophilic. For example, a study may find that 60% of a sample of sex offenders show a pedophilic sexual arousal pattern when assessed phallometrically, producing a sensitivity estimate of 60%; however, the sensitivity is actually higher (66%) if 90% of the sample is truly pedophilic, as Freund and Watson (1991) estimated on the basis of their clinical experiences.

Given the highly negative consequences of being identified as pedophilic, cutoff scores providing high specificities are typically used in clinical settings. Specificity is defined as the percentage of nonoffenders who are identified as not being sexually interested in children. In a sample of 147 sex offenders with unrelated child victims, using a cutoff score that produced 98% specificity, sensitivity was 50% in Freund and Watson (1991). In a sample of sex offenders with child victims who denied being sexually interested in children, Blanchard et al. (2001) reported that sensitivity was 61% among men with many child victims, and specificity was 96% among men with many adult victims and/or adult sexual partners.

If one considers admission of pedophilia to be a suitable standard, then the sensitivity of phallometry is very high. In a series of three studies, Freund and his colleagues reported on the results of phallometric testing for 137 sex offenders with child victims who admitted to having pedophilia; the sensitivity of phallometric testing in this group of self-admitted pedophiles was 92% (Freund & Blanchard, 1989; Freund, Chan, & Coulthard, 1979; Freund & Watson, 1991).

Because the cutoff scores in these phallometric tests are purposefully set high (typically equal or greater sexual arousal to children than to adults), someone who exceeds the cutoff score is very likely to be a pedophile. Having an index score below the cutoff means the individual is either not pedophilic or was not detected as such by the phallometric test.

Predictive Validity

Phallometry has good predictive validity. A recent meta-analysis of 10 studies with a combined sample size of almost 1,278 sex offenders found that phallometrically measured sexual arousal to children was one of the single best predictors of sexual recidivism among sex offenders; its correlation with sexual recidivism (r

= .32) was similar to the correlation obtained by measures of psychopathy or prior criminal history, and both psychopathy and prior criminal history are strong and robust predictors of recidivism across types of offender (Gendreau, Little, & Goggin, 1996; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004, 2005; Hare, 2003).

Criticisms

Despite the consistent evidence supporting the clinical and research use of phallometry to assess pedophilia, there is disagreement about the utility of this assessment method, and the number of phallometric laboratories has declined over the past decade (Howes, 1995; Knopp, 1986; McGrath, Cumming, & Burchard, 2003). Critics such as Launay (1999) and W. L. Marshall and Fernandez (2000) have discussed their practical and ethical objections to phallometry. One of the main criticisms of phallometric testing is its lack of standardization in stimuli, procedures, and data analysis (though this is more a criticism of how phallometric testing is conducted in practice than the methodology itself). Howes (1995) identified a great deal of heterogeneity in methodologies in a survey of 48 phallometric laboratories operating in Canada and the United States. For example, laboratories vary in the number and nature of stimuli they present, duration of stimulus presentations, and the minimum arousal level accepted for clinical interpretation of individual response profiles. Unfortunately, many laboratories do not use validated procedures and scoring methods.

Figure 2.3

. Volumetric apparatus for phallometric testing.

Standardization of procedures is needed because some phallometric testing procedures have been validated, but many others in use have not. Standardization would also facilitate the production of normative data and thereby aid in the interpretation and reporting of phallometric test results. Unfortunately, there have been repeated calls for standardization in the field but little progress has been made. There is empirical evidence to guide decisions about these methodological issues, such as the number and kinds of stimuli to present, the use of circumferential or volumetric devices (see

Figure 2.3

), and the optimal transformations of data for interpretation (see Lalumière & Harris, 1998; Quinsey & Lalumière, 2001). General guidelines on phallometry have been developed by the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (1993; Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, Professional Issues Committee, 2001).

Phallometric testing has been criticized for its lack of reliability. Traditional internal consistency and test–retest analyses suggest that the reliability of phallometric testing is moderate at best (Barbaree, Baxter, & Marshall, 1989; P. R. Davidson & Malcolm, 1985; Fernandez, 2002; but see Gaither, 2001). The validity of a test is constrained by its reliability, yet both the discriminative and predictive validity of phallometric testing are good, suggesting that it must be reliable. This apparent contradiction in test properties suggests two nonexclusive possibilities: (a) The discriminative and predictive effect sizes that have been obtained for phallometry are conservative estimates of its validity and would be even higher if reliability could be increased, and (b) phallometric testing is different from traditional paper-and-pencil tests, and different indices of reliability are required for evaluations of phallometric test properties.

Phallometry has also been criticized because it is an intrusive procedure, requiring men to partially undress, place a device around their penis, and have their erectile responses recorded while a laboratory technician monitors the session. In addition, testing sessions are sometimes conducted with a camera trained on the upper body of the subject to minimize attempts to fake the test such as looking away or tampering with the phallometric device.

It is true that phallometry is more physically intrusive than interviewing or administering a questionnaire, but it provides valuable information that cannot otherwise be obtained, because phallometry can identify pedophilia among men who deny any sexual interest in children. Moreover, it is not redundant in the assessment of sex offenders who admit pedophilia, because it is the relative strength of those interests that predicts sexual recidivism. For example, two sex offenders may both identify themselves as pedophiles, but in phallometric testing, only one of them may respond substantially more to stimuli depicting children than to pictures of adults, suggesting his risk for sexual recidivism is higher, all other things being equal.

Two other ethical objections that have been raised about phallometry are that presenting visual stimuli depicting children is unethical because the children depicted in the stimuli could not provide informed consent when the photographs were taken (some laboratories use child pornography seized by police), and presenting stimuli depicting child pornography images is unethical because it could have harmful effects on the males being assessed, such as providing new content for sexual fantasies, particularly for adolescent sex offenders or first-time offenders.

Regarding the first ethical objection, audiotaped stimuli can be used to gauge interest in sexual interactions with fictional children, and digital image manipulation software allows evaluators to create realistic human figures that do not depict real individuals (morphed images of children are still illegal in the United States under the Child Pornography Prevention Act, 2000). Regarding the second objection, offenders who are clinically assessed using phallometry have already engaged in illegal sexual behavior and are likely to be exposed to graphic accounts of sexual offenses in group therapy, reading materials, and video presentations. Although comparable research has not been completed with sex offenders, Malamuth and Check (1984) showed that research volunteers who were exposed to depictions of rape were less accepting of rape myths after a short debriefing procedure. Sex offenders receive much more than a short debriefing in any treatment or supervision that takes place after their phallometric assessment; in fact, common targets of sex offender treatment programs are antisocial attitudes and beliefs about sex with children.

Finally, it has been suggested that phallometry is not useful for some groups of sex offenders, such as adolescent sex offenders or first-time incest offenders. However, there are data to suggest this is not the case. We have evaluated the use of phallometric testing for adolescent sex offenders with child victims (Seto, Lalumière, & Blanchard, 2000). Because an age-matched comparison group was not available, these adolescents were compared with young adults ages 18 to 21 who had not committed sexual offenses involving children. As a group, adolescents with male victims had relatively higher responses to pictures of children than the young adult comparison participants. Adolescents with both male and female children as victims responded more to pictures of children than to pictures of adults. Similar findings were reported by Robinson, Rouleau, and Madrigano (1997), who compared adolescent sex offenders with 18-year-old comparison participants. Finally, Blanchard and Barbaree (2005) phallometrically classified 48 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 16 into those who showed a sexual preference for prepubescent children, pubescent children, or adults. Those who showed a sexual preference for prepubescent children had significantly more child victims under the age of 12 than those who showed another sexual preference.

Several studies have examined the phallometric responses of sex offenders distinguished according to their genetic relatedness to the child victim (Blanchard et al., 2006; Rice & Harris, 2002; Seto, Lalumière, & Kuban, 1999). A majority of the incest offenders in Seto et al. were convicted for the first time for a sexual offense. Nonetheless, all incest offender groups had higher average indices of relative responding to children than did the comparison groups of rapists or nonoffenders. Together, these studies suggest that phallometry can be useful for both adolescent sex offenders and first-time incest offenders.

Neuroimaging

An intriguing development in the assessment of sexual interests is the introduction of neuroimaging methods. Early research by Lifshitz (1966) showed that differences in patterns of neural activity could be detected when presenting sexual versus nonsexual stimuli to male participants, and Costell, Lunde, Kopell, and Wittner (1972) found that both men and women showed differences in electroencephalogram readings for their preferred compared with nonpreferred sex. Cohen, Rosen, and Goldstein (1985) reported that electroencephalogram activation was relatively higher in the right temporal region of the brain when men were presented with sexual stimuli. Finally, several more recent studies using higher resolution neuroimaging technologies have described different areas of relatively higher brain activation when volunteers are exposed to sexual versus neutral stimuli (Karama et al., 2002; Park et al., 2001; Redouté et al., 2000; Stoléru et al., 1999). There is variability across studies, but some structures have been consistently reported, including the anterior cingulate gyrus, associated with attention; the insular cortex, associated with sensory integration and object recognition; and the inferior frontal cortex, associated with language processing.

A case study that suggests neuroimaging methods might someday be used in the assessment of pedophilia was reported by Dreßing et al. (2001). These investigators used functional magnetic resonance imaging to detect differential activation of the anterior cingulate gyrus and right orbitofrontal cortex of a 33-year-old pedophile who preferred boys compared with two men who preferred adult women. The pedophile showed differential activation of the anterior cingulate gyrus when he looked at pictures of boys in swimsuits but not when he looked at pictures of adult women in swimsuits; the two other men showed the same pattern of activation when presented with pictures of adult women in swimsuits, but not with pictures of boys in swimsuits. The pedophile also differed from the two teleiophilic controls in not showing left hemispheric activation during the stimulus presentations. It is an intriguing possibility that the same areas of the brain are involved in processing of sexual stimuli by pedophiles and nonpedophiles. In a similar vein, Nancy Kanwisher and her colleagues have identified specific brain regions that are selectively activated by seeing faces or body parts (Downing, Jiang, Shuman, & Kanwisher, 2001; Grill-Spector, Knouf, & Kanwisher, 2004; Kanwisher, 2003). One wonders if the level of brain activation is influenced by the attractiveness or interest elicited by the faces or body parts that are viewed and if pedophiles and nonpedophiles would differ in their brain activation when presented with images of child faces versus adult faces or with childlike body shapes versus adultlike body shapes.

The development of neuroimaging methods could reveal the brain structures involved in processing of sexual stimuli. Neuroimaging could provide an assessment that is more difficult to fake than phallometry and viewing time and less dependent than sexual offense history on opportunities to offend, detection by authorities, or self-report biases. Refining the child stimuli used in psychophysiological and other laboratory tasks could also produce greater discriminative and predictive validity.

PEDOPHILIA AND CHILD CUES

What is it about children that pedophiles find sexually attractive? A number of researchers have investigated this question, both in terms of the psychological and physical cues that characterize child victims and what pedophiles themselves have reported to be attractive. The 77 self-identified pedophiles in G. D. Wilson and Cox’s (1983) survey of members of a pedo phile advocacy group described the personality and physical characteristics they preferred in children. These results are summarized in

Tables 2.1

and

2.2

. G. D. Wilson and Cox suggested that the majority of men who preferred boys preferred feminine features and gave as an example Respondent 50, who said he preferred young boys because “they have little or no body hair and their bodies are more effeminate” (p. 22). Lang, Rouget, and van Santen (1988) found that child sexual abuse victims tended to be lighter and smaller than age-matched comparison children. Other physical features that have been reported by offenders to be attractive include soft and smooth skin, a slim body, lack of body hair, appearance of the genitals, and appearance of the buttocks (Conte, Wolf, & Smith, 1989; Freund, McKnight, Langevin, & Cibiri, 1972; W. L. Marshall, Barbaree, & Butt, 1988). Consistent with Quinsey and Lalumière’s (1995) speculation, these features indicate youthfulness, and many of them are correlated with heterosexual men’s appraisals of female attractiveness. However, unlike other men, pedophiles are not attracted to cues of sexual maturity such as breasts.

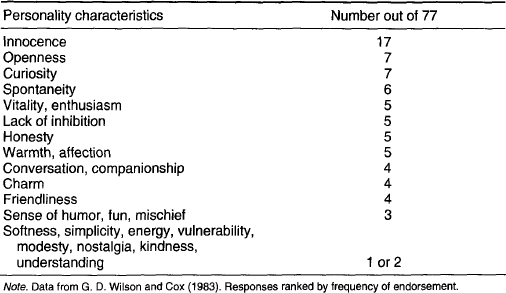

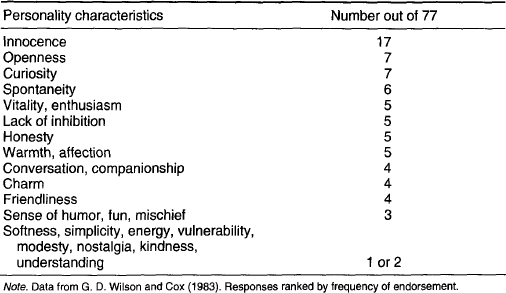

TABLE 2.1

Important Personality Characteristics of Children, as Identified by 77 Pedophiles

Kurt Freund, a pioneer in the study of pedophilia, speculated that the critical features for pedophiles were body size and shape. His intuition is supported by a pair of studies by Rice, Chaplin, and Harris (2003) that seemed at first to find a paradoxical effect. In the first study, sex offenders with girl victims responded relatively more to adult women over the age of 25 than to younger adult women between the ages of 18 and 25, unlike nonoffending controls, who responded relatively more to the younger adult women. In the second study, sex offenders who targeted prepubescent children also responded relatively more to stimuli depicting older adult women; in fact, the magni tude of their responses to older adult female and child stimuli were similar. Rice et al. speculated that the pedophiles in the sex offender group were responding to the waist-to-hip ratio

1

of the depicted persons, which was around 0.80 for both the older adult women and prepubescent children, in contrast to around 0.70 for the younger adult women.

TABLE 2.2

Important Physical Characteristics of Children, as Identified by 77 Pedophiles

It is possible that male pedophiles differ from other men in their response to waist-to-hip ratio. This divergence may be developmental: Connolly, Slaughter, and Mealey (2004) examined waist-to-hip ratio preferences in a sample of 511 children and adolescents ranging in age from 6 to 17. They found a gradual difference in the participants’ preferred waist-to-hip ratios across age, such that the 285 boys showed an increasing preference for smaller waist-to-hip ratio among female figures (and larger waist-to-hip ratios for male figures). This tendency was not present among the youngest respondents (age 6), and the boys’ preferences resembled the waist-to-hip ratio preferences of adult men by the time the boys were 15.

T. P. Smith (1994) examined perceptions of attractiveness and apparent age and the likelihood of being a sexual abuse victim in a series of three studies. In the first study, she showed photographs of sexually abused girls and age-matched nonabused girls to university students who were blind to the girls’ abuse status; the abused girls were rated as more attractive and younger looking than the nonabused girls. In the second study, T. P. Smith gave photographs of girls who were aged 11 or 12 to university students and asked them to judge the likelihood the girl might be sexually abused. Attractive girls were rated as more likely to be sexually abused by an adult, although there was no effect of their perceived age (the girls might look older or younger than their chronological age). There was an interaction between attractiveness and age, such that older attractive girls and younger unattractive girls were rated as more likely to be sexually abused by an adult. In the third study, T. P. Smith compared the ratings of 34 university students and 38 men in treatment for paraphilias or sexual offending (71% of the treatment group met the diagnostic criteria for pedophilia). The students rated girls who looked older as being at greater risk, but only if they were attractive; there was no effect of perceived age for unattractive girls. In contrast, the predominantly pedophilic men in the treatment group rated pubescent girls as at greater risk if they looked older and prepubescent girls as at greater risk if they looked younger. This last finding suggests the sex offenders recognized two distinct groups at risk: one that was sexually maturing or mature (pubescent girls who looked older than their actual age) and one that was clearly sexually immature (prepubescent girls who looked younger than their actual age).

Summarizing and integrating these results with the research literature on sexual offending against children, T. P. Smith (1994) suggested there are two pathways to sexual offending against girls, consistent with the two major risk dimensions identified in sex offender follow-up research and current theories about sexual offending against children (see

chaps. 4

and

7

, this volume). The first pathway can be described as nonpedophilic because the offenders target pubescent girls who look older than their actual age; in other words, these men target girls who are sexually maturing or mature but below the legal age of consent. The second pathway can be described as pedophilic because the offenders target sexually immature girls who look younger than their actual age. Consistent with this dual-pathway view of sexual offending against girls, Finkelhor and Baron (1986) reviewed six surveys of child victims and found a peak in victim age around the ages of 6 and 7 (pedophilic pathway) and a second peak at the age of 10 onward (nonpedophilic pathway). Girls around the ages of 10 to 12, some of whom would be showing signs of puberty, had twice the rate of victimization as other girls.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

Although pedophilia can most easily be assessed using self-report, either through interviews or questionnaires, sex offenders often minimize or deny their sexual interest in children in part because of the social or legal consequences of being identified as a pedophile. As a consequence, self-report is informative when someone acknowledges having sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, arousal, or behavior involving prepubescent children, but it is less informative if someone denies pedophilic interests. Self-disclosure may be increased by the use of polygraphy (likely reflecting a bogus pipeline effect), but the validity of polygraph determinations of deception has not been clearly demonstrated, and there is an unknown level of risk of inducing false confessions.

Studies have demonstrated that phallometric responses can reliably distinguish groups of sex offenders against children from other men, and a phallometric index of relative sexual arousal to children is one of the strongest single predictors of sexual recidivism. Some of the criticisms made regarding the clinical use of phallometry have a great deal of merit, but they can be addressed through standardization of stimuli and procedures, the use of audio stimuli, and the use of new technologies such as digital image manipulation software. It might even be possible to develop portable phallometric devices to conduct assessments of men as they encounter children and adults in real-life settings (Rea, DeBriere, Butler, & Saunders, 1998).

For these reasons, and especially for its predictive value, I believe phallometry is the preferred method for assessing pedophilia in clinical or correctional settings. When phallometric testing is unavailable or the individual refuses to participate in the phallometric procedure, alternative measures based on viewing time or sexual offense characteristics (if a sexual offense history is available) can be used. Sexual offense information is preferred, because one study has shown that it can predict recidivism among sex offenders against children, whereas no studies have yet demonstrated that viewing time measures are predictive (see Seto et al., 2004). Self-report is also useful, though it is more likely to be honest once legal proceedings have been completed (so the person is no longer anticipating trial or sentencing if found guilty) and once rapport has been established in the context of treatment or supervision (Barbaree, 1991; Bourke & Hernandez, in press; Worling & Curwen, 2000). Regardless of the source, there is an asymmetry such that indications that the person is pedophilic are important to note in terms of risk assessment and management, whereas the absence of such indications may mean the person is not pedophilic or has successfully avoided detection.

There is research to guide the optimization of phallometric methods, which can already achieve sensitivities over 90% among sex offenders with child victims who admit having pedophilic sexual interests. The challenge is to convince phallometric laboratories to change their procedures and their stimulus sets to emulate one of the validated assessment protocols, such as those used at my institution, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

2

Many of the phallometric studies cited in this book were completed using data collected in these laboratories. Consumers of phallometric assessment reports should confirm that the procedures and stimulus sets that were used were validated, just as they would expect paper-and-pencil questionnaires to have acceptable psychometric properties.

Alternatives to phallometry have shown promise, but more research is needed on these measures. Of particular interest are recent advances in neuroimaging and the modification of cognitive science methods (e.g., rapid serial visual presentation and a Stroop task) to the assessment of pedophilia. Ideally, alternative measures will be less intrusive, less vulnerable to faking, and less technically complex than phallometry.

Though reliable and valid methods for assessing pedophilia have been developed, the psychiatric diagnostic criteria of pedophilia itself have been challenged. O’Donohue, Regev, and Hagstrom (2000) and W. L. Marshall (2006b) pointed out problems with the DSM–IV–TR

diagnostic criteria, including the absence of data on interrater reliability (the extent to which two clinicians would agree in assigning the diagnosis) and test–retest reliability (whether someone diagnosed as a pedophile at Time 1 would continue to be identified as such at Time 2). Consistent with these critiques, J. Levenson (2004a) reported diagnostic reliability in a sample of 295 adult male sex offenders (three quarters of the sample had committed sexual offenses against minors) and found that the interrater reliability for a diagnosis of pedophilia was acceptable but not impressive. R. J. Wilson, Abracen, Picheca, Malcolm, and Prinzo (2003) compared the classification provided by different measures of pedophilia—sexual history, strict application of DSM–IV–TR

criteria, phallometric responding, and an expert diagnosis—and found that scores on these measures were not highly correlated in a sample of sex offenders against children, suggesting each was identifying different groups of pedophiles. An unpublished analysis of the data reported in Seto, Cantor, and Blanchard (2006) found that self-reported sexual interests, sexual history, and possession of child pornography independently contributed to the prediction of phallometric responding. These results suggest that the most accurate identification of pedophiles would come from using multiple sources of information. Given the challenges in subjectively combining different pieces of information, creating an algorithm that incorporates different valid measures of pedophilia—self-report, sexual history, and phallometric responding—might be the best approach (Ægisdóttir, Spengler, & White, 2006; Grove et al., 2000).

Though the criteria seem straightforward, the interrater reliability of the diagnosis of pedophilia is constrained because of the subjective way in which information about sexual interests is typically combined; in addition, this information is usually inferred from behavior, because many individuals are unwilling to admit to sexual thoughts, fantasies, or urges regarding prepubescent children. Thus, one of the complications in reviewing the literature on pedophilia is the fact that different assessment methods (and operational definitions of pedophilia) have been used, and thus the groups that have been studied are not equivalent. The types of study group that are available are discussed in

chapter 3

.