1

INTRODUCTION:

DEFINING PEDOPHILIA

Pedophilia

—a sexual preference for prepubescent children—is manifested in persistent and recurrent thoughts, fantasies, urges, sexual arousal, or behavior as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(4th ed., text revision; DSM–IV–TR

; American Psychiatric Association, 2000; see also Seto, 2002). A similar definition was used by the World Health Organization (1997): “a sexual preference for children, boys or girls or both, usually of prepubertal or early pubertal age” by an adult. The APA Dictionary of Psychology

(American Psychological Association, 2007) defined pedophilia as a

paraphilia in which sexual acts or fantasies with prepubescent children are the persistently preferred method of achieving sexual excitement. The children are usually many years younger than the pedophile (or pedophiliac). Sexual activity may consist of looking and touching, but sometimes includes intercourse, even with very young children. (p. 681)

The word

pedophilia

is derived from the Greek words for love (

philia

) of young children (

pedeiktos

). The term

paedophilia erotica

was coined by Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1906/1999) in his pioneering collection of sexological cases,

Psychopathia Sexualis

. Pedophilia is probably the most commonly discussed paraphilia in the clinical and forensic research literatures (see

Appendix 1.1

). In its strongest form, it reflects an exclusive sexual preference for prepubescent children in which the pedophilic individual has a strong sexual interest in children who show no signs of secondary sexual development and has no sexual interest in sexually mature adults (see

Appendixes 1.2

and

1.3

). For the etymologically inclined, John Money coined the term

nepiophilia

(from the Greek

nepion

, meaning infant) for the very rare sexual preference for infants (Greenberg, Bradford, & Curry, 1995), and Kurt Freund modified the term

ephebophilia

(from the Greek

ephebos

, meaning adolescent) into

hebephilia

to describe the sexual preference for pubescent children; unlike pedophiles, hebephiles are attracted to children who show some signs of secondary sexual development, such as the emergence of pubic hair and the initial development of breasts in girls. It is not clear if sexual preference for infants and sexual preference for pubescent children represent variants of pedophilia or instead represent different paraphilias. Pedophilia, nepiophilia, and hebephilia can be distinguished from

teleiophilia

, a term coined by Ray Blanchard to describe the species-typical preference for sexually mature persons (from the Greek

teleios

, meaning full grown).

1

Pedophilia is not synonymous with sexual offending against children, though these concepts are often used interchangeably in public, political, and media accounts. Commentators also often refer to individuals who have committed sexual offenses against postpubertal adolescents (e.g., a sexually maturing 15-year-old who is under the legally defined age of consent in a particular state) as pedophiles, though this behavior would not meet any of the definitions outlined previously. As I discuss in this book (see

chaps. 3

and

4

, this volume), some pedophiles are not known to have ever committed sexual offenses against children, and many sex offenders against children commit their crimes for reasons other than pedophilia. Such reasons can include general antisocial tendencies, high sex drive, and temporary disinhibition due to alcohol or drug use. The distinction is important because pedophiles who refrain from sexual contacts with children are unfairly placed in the same categories as men who have committed crimes against children and because pedophilic and nonpedophilic sex offenders differ in their risk to reoffend and in the kinds of interventions that are most likely to be effective in preventing future crimes against children.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PUBERTY

A key element of any operational definition of pedophilia is the pubertal status of the children of interest. Sexual contact with postpubertal adoles cents is prohibited by law in many jurisdictions, but these prohibitions are arbitrary in the sense that they vary from country to country (and state to state in the United States) and are based on a legally defined age criterion (current ages for many jurisdictions are provided by

http://www.ageofconsent.com

), which is usually justified in terms of the level of cognitive and emotional development of the legally defined minors and their potential vulnerability to exploitation by adults. In contrast to the relativity of legally defined age of consent, puberty and the concomitant development of secondary sexual characteristics is a nonarbitrary and objective event that is reproductively relevant. From a biological perspective, being sexually attracted to nonfertile, prepubescent children would have been maladaptive in the past (because sexual behavior with prepubescent children would not have led to successful reproduction) and likely continues to be maladaptive now, regardless of place or time. Why pedophilia exists at all is a major biological puzzle.

The age at which puberty occurs can vary. For example, there is some evidence that the average age of puberty decreased in the 20th century, at least in industrialized nations (Herman-Giddens et al., 1997), a decline that has been attributed to improvements in nutrition and overall health (Thomas, Renaud, Benefice, De Meeüs, & Geugan, 2001).

2

A substantial proportion of young girls show some signs of secondary sexual development by the ages of 12 or 13. Thus, adults who now have sexual contact with girls between the ages of 12 and 14 violate age of consent laws in most jurisdictions, but these individuals may not be acting on pedophilic interests, because the girl victims may show secondary sexual characteristics such as breasts and pubic hair. Historical accounts of sexual contacts with girls between the ages of 12 and 14, however, may indeed represent pedophilic behavior.

A reliable system for determination of pubertal stage was described by Tanner (1978). For girls, Tanner scores are based on pubic hair growth, morphology of the vulva, breast development, and development of axillary hair. Tanner described five stages. Stage 1: no secondary sexual development; Stage 2: budding of breasts, beginning of axillary and pubic hair growth, and mucosal changes in labia minora and vagina; Stage 3: further enlargement of breasts with elevation of areola, no separation of contours of breasts and nipples, darker and coarser pubic hair, and more axillary hair; Stage 4: projection of areola and papilla to form a second mound above the level of the breasts and adultlike axillary and pubic hair; and Stage 5: mature breasts and mature distribution of axillary and pubic hair. For boys, Tanner scores are based on genital development, again in five stages. Stage 1: testes, scrotum, and penis are the same as they are in early childhood; Stage 2: scrotum and testes become enlarged and the skin of the scrotum reddens and changes in texture; Stage 3: penis grows larger, mainly in length at first, with further growth of testes and scrotum; Stage 4: penis increases in size, with increased circumference and development of glans, larger testes and scrotum, and darkening of scrotal skin; and Stage 5: genitalia are adultlike in size and shape.

Although age and Tanner stage are strongly and positively correlated, Lang, Rouget, and van Santen (1988) noted that using chronological age to define pedophilia is less precise than using the pubertal status of the children of interest (see also Cooper, 2005; Rosenbloom & Tanner, 1998). Most studies of pedophilia have referred to the age of children, however, either in terms of self-reported preferences of self-identified or clinically identified pedophiles or age of child victims for sex offenders. Whatever a child’s chronological age, the biological significance of sexual immaturity remains the same. Lang, Rouget, et al. (1988) found that two thirds of a sample of child sexual abuse victims were in Tanner Stage 1, with another 15% in Tanner Stages 2 and 3. None of the victims age 10 or younger were menstruating. Victims in Tanner Stages 4 and 5 were more likely to experience oral, vaginal, or anal intercourse (and were probably more likely to have been offended against by nonpedophilic men). The Tanner system does not take into account other physical features, however, and it is likely that features such as body shape and size are also important determinants of pedophilic attraction to children (e.g., Lang, Rouget, et al., 1988; Rice, Chaplin, & Harris, 2003).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF PEDOPHILIA

The prevalence of pedophilia in the general population is unknown. Epidemiological surveys with the questions that are needed to identify pedophilia—particularly those having to do with persistence and intensity of sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, arousal, or behavior involving prepubescent children—have not yet been conducted. Ever having thoughts of sex with a prepubescent child or even ever having sexual contact with a prepubescent child would not be sufficient to meet the standard diagnostic criteria for pedophilia because persistence and intensity are two key features of these definitions.

The following surveys of adult men and women provide upper limit estimates of the prevalence of pedophilia in the general population because they do not include questions about persistence or intensity. For example, finding that 5% of adult men have fantasized about sex with a prepubescent child would mean the prevalence of pedophilia must be lower than 5% because only those who have persistent fantasies could qualify for the diagnosis of pedophilia. Men are more likely than women to be sexually interested in children (Smiljanich & Briere, 1996). Crépault and Couture (1980) surveyed 94 men about specific sexual fantasies during masturbation or intercourse and found that 62% had fantasized about having sex with a young girl, and 3% had fantasized about having sex with a young boy. Briere and Runtz (1989) surveyed 193 male university students and found that 9% had fantasized about having sex with a young child (age unspecified); 5% masturbated to fantasies of sex with children; and 7% indicated some likelihood of having sex with a child if they were guaranteed they would not be punished or identified. The percentages of those who had sexual fantasies about prepubescent children, masturbated to these fantasies, or acted on these fantasies are not known. Templeman and Stinnett (1991) surveyed 60 male college students and found that 5% expressed an interest in having sex with a girl under the age of 12. Fromuth, Burkhart, and Jones (1991) found that 3% of the 582 college men they surveyed reported having had a sexual experience with a child when the respondent was age 16 or older (thereby excluding peer sexual activity among children). The majority of the contacts were made by 4 men who admitted committing multiple offenses. T. P. Smith (1994) found that 6 (3%) of her sample of 183 male college students, under condition of anonymity, admitted they had had sexual contact with a prepubescent girl aged 12 or younger. None admitted sexual contact with a prepubescent boy aged 12 or younger. In addition, 11% acknowledged sexual contact with an adolescent girl between the ages of 12 and 15 since they had reached the age of 18 themselves. Beier, Alhers, Schaefer, and Feelgood (2006) found that 4% of the 373 men who responded to a sexual survey under conditions of anonymity admitted having sexual contact with a child, 9% admitted having sexual fantasies about children, and 6% admitted masturbating to sexual fantasies about children. Together, these survey results suggest that sexual fantasies about children and sexual contacts with children are uncommon (excluding the outlier regarding fantasies about girls reported by Crépault & Couture, 1980), and thus pedophilia is rare in the male population, occurring at a frequency of less than 5%.

At the same time, Kurt Freund and other investigators have demonstrated that heterosexual men recruited from the community exhibit some sexual arousal to prepubescent girls, less than they respond to pubescent girls or adult women but more than they respond to male stimuli (Freund, McKnight, Langevin, & Cibiri, 1972; G. C. N. Hall, Hirschman, & Oliver, 1995; Seto & Lalumière, 2001). These laboratory findings suggest that men in the community have the potential to become sexually aroused by prepubescent girls; however, most men do not show a preference for prepubescent girls (or boys).

In a rare survey of female respondents, Fromuth and Conn (1997) asked 546 college women about their sexual experiences with children at least 5 years younger than they were. Of the sample, 4% acknowledged at least one such experience (92% of these incidents involved physical contact, mostly touching and kissing). The average age of the respondent at the time was 12, and the average age of the child was 6. Of the respondents, 13% said they did not initiate the experience. Unlike the predominantly female child victims of convicted sex offenders, the majority of children identified in this anonymous survey were boys (70%). The majority of children were related (69%) to the women. None of these incidents were detected by police or other authorities. Women who admitted engaging in sexual contact with a child were more likely to report attraction to or fantasies involving children than those who denied such contact (18% vs. 5%).

PEDOPHILIA AND SEXUAL CONTACTS AGAINST CHILDREN

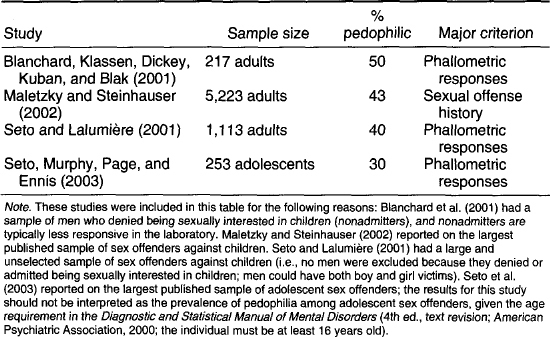

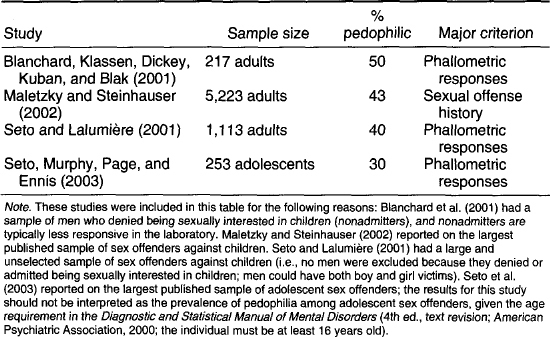

Most of what researchers know about pedophilia has come from the study of men who have had sexual contact with children, especially those who have been convicted of crimes for such contact. Thus, much of this book draws on research about men who commit sexual offenses against children, not all of whom are pedophiles. Conservatively, the prevalence of pedophilia among men who commit sexual offenses against children is around 50%, depending on the criterion used to identify pedophilia (see

Table 1.1

). The distinction—between pedophiles and men who have committed sexual offenses against children—needs to be kept in mind throughout this book. Another distinction is one between those men who are exclusively interested in children and those who are interested in both children and adults; this distinction is reflected in the

DSM–IV–TR

(American Psychiatric Association, 2000) recognition of exclusive and nonexclusive types of pedophilia.

In the next sections, I review historical and cross-cultural evidence about adult–juvenile sex, including adult–child sex, to examine the extent to which this behavior has appeared across time and across cultures and to provide a context for examining pedophilia in modern societies. Some of these historical or cross-cultural examples are clearly relevant to pedophilia, involving prepubescent children, whereas others are less so, referring to adult sexual contacts with adolescent boys or girls.

HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

Adult–juvenile sex has been a social and legal concern for a long time. Quinsey (1986) provided an overview of historical sources on adult–child sex. Killias (1990) described the Western history of laws against adult–child sex. For example, Roman law fixed the minimum age for marriage as 12 for girls and 14 for boys, and following this tradition, the Roman Catholic Church adopted the same rule. Killias claimed there was no minimum age for marriage in the Middle Ages; instead, what mattered was whether the person had reached physical maturity, and in fact, anyone who had attained puberty could be expected to fulfill adult roles. Killias stated that the common law tradition treated any person who had reached puberty as the equivalent of an adult and suggested that the notion of a developmental stage of adolescence did not appear until the 19th century.

TABLE 1.1

Percentage of Sex Offenders With Child Victims

Who Are Pedophilic (Selected Samples)

Lloyd (1976) provided a brief social history of boy prostitution. He suggested that the first evidence of boy prostitution appeared in Roman records and claimed it was fashionable for wealthy Romans to buy young male slaves (Lloyd did not specify the age or pubertal status of these slaves) as sexual companions for their sons until the sons were married. Lloyd added that most Roman cities had brothels with boy prostitutes who were purchased as slaves and made available to poorer citizens for a price. Particularly attractive slaves were selected and raised in special schools before being made available to wealthy citizens. According to Lloyd, one of the most famous of these youths was Antinous, who so enraptured Emperor Hadrian that statues of Antinous were erected all over the Roman Empire upon the youth’s death in 130 CE.

3

Probably one of the best known historical examples of adult–juvenile sex is the custom in ancient Greece of adult men taking young male adolescents as lovers. According to Killias (1990), this was considered to be a mentoring relationship; the word for lover

is inspirer

in the Doric dialect. A famous inspirer relationship was that between Alexander the Great and Hephaiston, his boyhood friend. The Greek word for this kind of relationship was paiderastia

(from which the word pederasty

is derived). A common synonym in ancient Greek writings for favored youths was ta paidika

(the boyish).

Killias (1990) suggested that taking a young ward was expected of adult men, and not doing so was considered a dereliction of one’s mentoring duty. It is noteworthy that relationships with sexually immature boys were severely punished, but boys who had begun puberty were idealized. Many Greek writers described this relationship as special and beautiful, but it cannot be determined from the historical record if this reflected the views of Greek society in general.

There are examples of adult–child sex, child prostitution, and incest from the Byzantine Empire (see Lascaratos & Poulakou-Rebelakou, 2000). The Byzantine Empire emerged following the decline of the Roman Empire and was the largest world state for over a millennium, from 324 to 1453. Both adult–child sex and incest were regulated by law, suggesting that incidents of adult–child sex and incest occurred frequently enough at some point to require legal and formal social control. Marriages involving children were frequently arranged for political and social reasons, but the couple was supposed to wait until the younger person had reached the age of 12 to begin having sex. According to Lascaratos and Poulakou-Rebelakou (2000), the best known example of this prohibition (and its violation) was the marriage of Princess Simonis, the only daughter of Emperor Andronicus II (reigned 1282–1328). She was married at the age of 5 to the 40-year-old Sovereign of the Serbs, Stephan Milutin, to foster a political alliance between the two states. Milutin did not wait for her to reach the legal age and raped her at the age of 8, “causing injuries of the womb, which prevented her from bearing children, and mental suffering which obliged her to return in tears to her homeland to be a nun” (Nicephorus Gregoras, cited in Lascaratos & Poulakou-Rebelakou, 2000, p. 1087). Her parents, apparently more concerned with the political alliance that had been formed than with their daughter’s well-being, forced her to return to Milutin.

Lascaratos and Poulakou-Rebelakou (2000) also claimed that the opportunity to broach the virginity of child prostitutes could be purchased at public auctions. They further reported that Byzantine writers specifically wrote about the problem of child sexual abuse, accusing eminent Byzantines of being pedophiles. These eminent persons included the Emperor Theodosius; Constantine V; and the Eparch of Constantinople, John Cappadoces, who “regularly assaulted small pre-adolescent children who had not acquired the signs of manhood, especially hair” (Kukules, quoted in Lascaratos & Poulakou-Rebelakou, 2000, p. 1087). The Orthodox Church recognized the problem of child sexual abuse and considered it to be one of the most serious sins, resulting in a penalty of Holy Communion being withheld for a period of 19 years. Legal punishments for sexual contacts with children outside of formal engagement or marriage could be severe, including fines; dragging the offender through the street; cutting off the offender’s nose; exile; and, in the most extreme cases, execution. A group of men who had sex with children during the reign of Justinian I were genitally mutilated, dragged naked through the streets, and then put to death.

There are also non-Western historical references to adult–child sex. Lloyd (1976) noted that ancient Chinese literature also describes men having sex with boys (again the boys’ ages or pubertal status are unspecified) but with a preference for effeminate, heavily made-up boys rather than the masculine, athletic boys idealized by ancient Greek writers. Ng (2002) cited a number of Chinese literary references regarding these relationships. Schild (1988) described Arabic literary references to sexual relationships between adult men and male youths and suggested that “the irresistible seductive power of beautiful youths is an often-repeated theme in Arabian and Persian poetry and literature” (p. 40). He suggested that these sexual contacts were an alternative sexual outlet for men who were unmarried because unmarried males and females were segregated, prostitutes were expensive to hire, and masturbation was considered to be against Islamic practices. Again, puberty was an important demarcation, because the sexual attractiveness of boys was considered to wane once boys had reached a certain degree of physical maturity.

At the end of the 19th century, Krafft-Ebing (1906/1999) was one of the first sexologists to provide clinical case descriptions of men who were sexually attracted to children (e.g., Case 228, an individual who was only interested in boys between the ages of 10 and 15 and reported no interest in girls or adults of either sex).

4

Krafft-Ebing thought pedophilia was rare—he had only seen 4 cases, all men who he believed had a primary sexual interest in children—and proposed that many cases of sexual contacts with children could be explained by boredom (men who were very sexually experienced with women and were seeking novel sexual stimulation), sociosexual deficits (men who were afraid of women or were anxious about their virility with adult women), or disinhibition (e.g., men who were intoxicated, experiencing senile dementia, or who had mental retardation). As I discuss in

chapter 4

, some of these ideas continue to be represented in contemporary explanations of sexual offending against children.

CONTEMPORARY CROSS-CULTURAL EVIDENCE

Much of the available scientific data about sex offenders with child victims has been gathered in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States, and Western European countries in the 20th century. However, Finkelhor (1994) reviewed surveys about child sexual abuse from 20 different countries. In addition to the countries listed above, these surveys included Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, and South Africa. All of these countries had records of child sexual abuse. Finkelhor noted the absence of comparable epidemiological data on African, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries. Other cross-cultural evidence includes that of Law (1979), who studied 155 offenders against children age 15 or younger in Hong Kong and found similarities in victim and offense characteristics (more girl victims than boy victims, boy victims older on average, and fondling as the most common act) between this Asian sample and North American and Western European samples.

Bauserman (1989) reviewed ethnographic evidence on adult–child sex (he excluded contacts with prostitutes, one-time encounters, stranger contacts, incidents involving obvious coercion, and father–son incest). Bauserman described ritualized relationships between men and boys among tribes in New Guinea and the Melanesian islands in the South Pacific. Among the Marind-Anim, a man would begin having a sexual relationship with his maternal nephew when the boy’s pubic hair first began to appear at the age of 12 and 13. The boy would live with the man and his wife and would receive instruction in hunting and gardening in exchange for his participation in anal intercourse. The relationship ended when the boy married at the age of 19 or 20. Among the Etoro, boys were expected to fellate older males to the point of ejaculation because semen was thought to promote their physical growth; this practice began around the age of 10 and continued into the early 20s (R. Kelly, 1976). Similar beliefs were held among the Kaluli, with boys beginning this practice around the age of 10 or 11 with a man who was selected by the boy’s father (Schieffelin, 1976). In probably the best known example of this kind of practice, Herdt (1981) described the Sambian initiation of prepubescent boys through the ritualistic fellatio of older boys. Semen was thought to help build up the boy’s life force and was considered necessary for boys to be able to reach puberty. Boys were reportedly reluctant to engage in this practice but complied because of fear of punishment. The boys would eventually undergo puberty, which was interpreted as support for the Sambian theory, and could then expect to receive fellatio from younger boys who were beginning the practice. Older boys stopped receiving fellatio from adolescent boys when the older boys married.

Lloyd (1976) claimed that prostitution of boys can be found all over the world and mentioned examples of brothels in the Middle East, the custom of basket-boys

in Vietnam who offered to carry groceries home for adult men and then offered sex in exchange for money, bini boys

in Manila, and juvenile street prostitution in Western societies.

There are fewer ethnographic accounts of sexual contacts between adult men and young girls, though there have been anthropological descriptions of arranged marriages between prepubescent girls and older men in some aboriginal tribes such as the Tiwi of Melville Island (Goodale, 1971). I could not find any ethnographic accounts of adult women having sex with children, suggesting the disproportionate representation of men in clinical and forensic samples of pedophiles (and sex offenders against children) cannot be solely attributed to a detection bias.

Finally, Graupner (2000) claimed that the minimum age criterion in laws regulating sexual conduct is a recent invention. All of the modern jurisdictions he studied had a minimum age criterion; in no jurisdiction was the age limit younger than 12 years (see also

http://www.ageofconsent.com

). Also, Graupner argued that sexual contact with a prepubescent child has always been illegal when it has been addressed, although the legality of sexual contact with a postpubertal minor has varied across jurisdictions.

PEDOPHILIA MAY BE A HUMAN UNIVERSAL

The extent to which a phenomenon appears across time and across cultures informs us about its underlying predispositions. Something that appears in most or all human cultures is more likely to be a universal characteristic of humans than something that is highly varied in its expression. The available evidence suggests that adult–minor sex has appeared both historically and across cultures, and this has included sexual contacts with prepubescent children. Because adult–child sex is correlated with pedophilia (though not synonymous with it), this suggests pedophilia has also appeared historically and cross-culturally. There is no theoretical reason to expect pedophilia to be culturally or temporally bound, though there may be large differences in the likelihood that pedophilic interests are expressed, depending on legal or social sanctions for sexual contact with children.

Overall, the historical and cross-cultural evidence supports the idea that puberty is a critical event, represented by minimum ages for marriage and the punishment of sex with prepubescent children in many societies. Adult–minor relationships in New Guinea and Melanesia are circumscribed cultural practices that are intended to bring about the onset of puberty. There is no evidence that adults are allowed to have sexual contacts with children outside of these practices. All of these different lines of evidence suggest that puberty has consistently been an important liminal event, consistent with the operational definition of pedophilia used in this book.

Some authors have argued that the designation of a sexual preference for prepubescent children as a disorder is socially and culturally arbitrary, reflecting prevailing social values, attitudes, and biases (e.g., Sandfort, Brongersma, & Van Naerssen, 1990). Sandfort et al. (1990) described evidence of adult–minor sex in other times or in different cultures as support of this position, although the review presented here suggests that sexual contact with prepubescent children (compared with sexual contacts with adolescents) has usually been strictly regulated. As discussed further in

Appendix 1.1

, the identification of a phenomenon as a disorder can be made on the basis of

biological pathology

, which can be defined as a disturbance in a biological process or mechanism that interferes with the ability of that process or mechanism to perform as designed by natural selection (Spitzer & Wakefield, 2002; Wakefield, 1992). In the case of pedophilia, the preference for prepubescent children is rare (less than 5%, although its prevalence in the general population is not precisely known), it is negatively sanctioned in most cultures and across time, and it is biologically pathological because a preference for prepubescent children interferes with reproductively viable sexual behavior (i.e., engaging in sexual behavior with sexually mature, opposite-sex persons with whom production of offspring could occur, at least in principle). Given the reproductive significance of preferring fertile sexual partners, pedophilia would seem to meet Wakefield’s (1992) evolutionarily informed functional criterion for mental disorder and can be conceptualized as the result of disruptions in the mechanisms underlying sexual age preferences. Wakefield’s definition applies specifically to the sexual preference for prepubescent children; it does not necessarily apply to individuals who have sexual contacts with prepubescent children, unless the person gives up opportunities to have sex with potentially fertile partners. From this perspective, the central feature of any set of diagnostic criteria for pedophilia is a persistent sexual preference for prepubescent children when sexually mature partners are potentially available, whether it is reflected in recurrent self-reported thoughts, fantasies, or urges about sexual contact with children; exhibited in greater sexual arousal to stimuli depicting prepubescent children relative to stimuli depicting adults; or manifested in a pattern of sexual behavior involving children. Whether the individual is distressed by this sexual interest or whether the sexual interest causes interpersonal or other difficulties is not germane.

A DARWINIAN PERSPECTIVE

Readers who are unfamiliar with modern Darwinian theories are referred to books by Buss (1999), Ridley (1995), and Williams (1996) for more detailed discussions of evolutionary biology, evolutionary psychology, and Darwinian thinking as well as responses to common criticisms of Darwinian theories. Wrangham and Peterson (1997) have written a highly readable example of the Darwinian approach with regard to male violence, and my colleagues have written excellent Darwinian analyses of rape (Lalumière, Harris, Quinsey, & Rice, 2005) and juvenile delinquency (Quinsey, Skilling, Lalumière, & Craig, 2004). Key Darwinian concepts for this book include sex differences in minimal parental investment and the consequent sex differences in mating strategies, partner age preferences, and risk taking (Trivers, 1972) as well as the application of inclusive fitness theory to understanding incest avoidance (Hamilton, 1964). These concepts are briefly discussed in the paragraphs that follow to provide the theoretical framework for some of the ideas presented in this book.

Some men have many offspring, whereas many others have none; in contrast, women can have only a certain number of children during their fertile years. Men are expected to be more willing to take physical risks to gain status, resources, or access to mates because of their much greater variance in reproductive success (Daly & Wilson, 2001; Quinsey, 2002; Quinsey & Lalumière, 1995; Rowe, 2002). Men who take risks and succeed could have many children, whereas those who take no risks are likely to end up with none. Physical risk taking includes antisocial and criminal behavior, so men are expected to be more likely to engage in antisocial or criminal behavior than women.

5

This can include fighting to gain status, theft to gain resources, and sexual coercion to increase sexual access (Lalumière et al., 2005; Quinsey et al., 2004). This risk taking is particularly notable among young men, so much so that the evolutionary psychologists Margo Wilson and Martin Daly coined the term

young male syndrome

to describe the co-occurrence of these behaviors in male–male competition for access to females (Daly & Wilson, 2001; M. Wilson & Daly, 1985).

In humans, there is a robust sex difference in preferred partner age. On average, men prefer younger female partners, and women prefer older male partners (Kenrick & Keefe, 1992). This sex difference (and many other sex differences) is predicted by Trivers’s (1972) parental investment theory, which observes that there is an obligate sex difference in the minimum required investment for reproduction, which leads to different benefits and costs for pursuing mating opportunities versus caring for offspring. In humans, women have a greater minimum investment than men because of the time and energy required by pregnancy. In principle, a man’s contribution could be a few moments and a single ejaculation, although the reality is that men usually invest a great deal in their offspring, forming committed relationships with their partners and contributing to child care. Following Trivers’s logic, ancestral male reproductive success was maximized by pursuing sex with many fertile female partners; female reproductive success was maximized by pursuing relationships with men who were able and willing to commit time, energy, and resources. These tendencies are expressed as mate preferences; thus, men tend to be attracted to women who show physical and behavioral signs of potential fertility, and women tend to be attracted to men who are physically dominant, high in status, and willing to commit.

Female fertility is correlated with youthfulness. Men who prefer youthful but sexually mature partners are more likely to produce offspring and thus pass on the preference than those men who are indifferent to age or those who prefer prepubescent partners or postmenopausal partners. It follows that cues of youthfulness such as unwrinkled skin, lustrous hair, and neotenous (juvenile-like) facial features are highly correlated with heterosexual men’s ratings of women’s physical attractiveness (e.g., Marcus & Cunningham, 2003). Other relevant cues include a waist-to-hip ratio near 0.70, which reflects a particular pattern of fat distribution (and pelvic bone development) and is predictive of physical health and fertility (for a brief overview and evidence of male responses to female waist-to-hip ratio, see Henss, 2000; Singh, 1993); firm breasts and buttocks; and a vivacious personality and demeanor.

Quinsey and Lalumière (1995) suggested that pedophilia may represent a disorder in mechanisms that regulate men’s preferences for youthfulness. In other words, pedophiles pay attention to youthfulness cues such as smooth skin and neotenous facial features but not to fertility cues such as a waist-to-hip ratio around 0.70 or firm breasts and buttocks. I discuss this idea further in

chapter 5

. In

chapter 2

, I address how knowledge about the important physical cues of female sexual attractiveness could greatly inform research attempting to understand pedophilia, at least with regard to sexual interests in young girls.

The key premise of inclusive fitness theory is that preferential treatment of one’s kin over unrelated others has been selected over ancestral history because one’s kin share more genes. Individuals who did not discriminate between their genetic kin and nonkin in sharing food, shelter, help, and other important resources would have been less likely to pass on their genes than those who did. One of the key postulates of inclusive fitness theory is the existence of an incest avoidance mechanism that minimizes the risk of deleterious inbreeding (for reviews, see Thornhill, 1993; Welham, 1990). This incest avoidance mechanism is presumably disrupted, overwhelmed, or absent when incest occurs (Seto, Lalumière, & Kuban, 1999). I discuss incest avoidance in much greater detail in

chapter 6

.

PLAN FOR THIS BOOK

My plan for this book is to present a consilient synthesis of available knowledge on pedophilia and sexual offending against children. By

consilient

, I mean a synthesis that integrates findings from different scientific disciplines and is coherent across their different levels of analysis, consistent with E. O. Wilson’s (1998) cogent articulation of this principle. In particular, I attempt to integrate findings from many different disciplines—anthropology, criminology, neuroscience, psychiatry, psychology, and sociology—in a manner that is consistent with current knowledge of evolutionary biology. In

chapter 2

, I discuss methods to assess pedophilia, a fundamental starting point for the scientific study of this atypical sexual preference. Such methods include self-report, inferences from sexual behavior, performance in laboratory tasks, and the objective recording of sexual arousal in response to sexual stimuli.

In

chapter 3

, I describe some of the characteristics and correlates of pedophilia, drawing from different study groups, including self-identified pedophiles, child pornography offenders, and clinical and correctional samples of men who have committed sexual offenses against children. I review theoretical explanations of sexual offending against children and pedophilia in

chapters 4

and

5

, focusing on the explanations that I believe to be the most promising in terms of advancing understanding of these phenomena. In

chapter 6

, I address the problem of incest, which involves sexual offenses against relatives committed predominantly by individuals who are notpedophiles.

Chapters 7

and

8

are the most applied, focusing on the current state of knowledge about the assessment of risk to sexually reoffend and interventions to prevent sexual offenses against children. In the afterword, I highlight the most important points of this book and make additional recommendations about future directions for research on etiology, assessment, and treatment. I also discuss how the research reviewed in this book might help clinicians, criminal justice officials, and policymakers.