How to Correct Hormones, Burn Fat, and Lose Weight Permanently

Now that you’ve learned how to manage some of the toxins that are threatening your brain body, let’s turn to a subject that most of us are all too familiar with: how to control weight. You and I know that sometimes our approach to eating is irrational, but did you realize that it’s your brain body talking and not a lack of willpower or knowledge? You’ll learn in this chapter how the brain regulates the weight of your body and, more important, what you can do to work with your brain to achieve the set point you desire.

Attaining the right body weight set point is life-changing—imagine not worrying about weight every day, or not binge eating and then feeling bad about yourself. Picture all of your clothes in your closet fitting you, right now, today.

What did you weigh at age eighteen? According to a recent study from Harvard University, a woman’s weight gain from age eighteen to middle age (forty to sixty-five, but defined as age fifty-five in the study) determines her risk of most diseases, including high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and obesity-related cancer. All of these conditions affect the brain body because of the same root cause: inflammation. For the 92,837 women followed for about thirty-seven years, the average weight gain was twenty-eight pounds. Women were at greater risk than men who gained a similar amount of weight over a similar period. Even moderate weight gain, defined as 5.5 to 22 pounds, reduced the chance of healthy aging by 22 percent for women.1 We knew already that excess fat predicts cognitive decline, and visceral fat deep in the abdomen is the most important health predictor in women.2 That’s because excess body fat secretes hundreds of hormones, peptides, and cytokines—such as leptin and adiponectin—collectively known as adipokines that affect the nervous system, liver, and immune system and can be associated with cognitive deficits, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.3 Short version: moderate weight gain between the ages of eighteen and fifty-five foretells poor aging later for your brain body, particularly for women.

I may be one of those unfortunate women. I weighed 125 pounds at age eighteen. Although I’m not yet fifty-five years old, I’ve spent half of middle age higher than that number by ten to twenty-five pounds. Not only does a rising body weight put me at risk of all of those major diseases, but it shifts many subtle measures in my microbiome, immune system, cardiovascular system, and gene expression (the way my genes talk to the rest of my body and brain). It gets worse. Two years ago, I gamely signed up for a “bod pod” to measure my body composition. Any confidence I had regarding my fastidious lifestyle vanished when I faced the truth that my body fat was the highest ever. I was never in the “athletic” range (14 to 20 percent), but now at 30 percent fat, I was no longer in the “fitness” (21 to 24 percent) or “moderately lean” (25 to 29 percent) category. Not only that, but I was inflamed: my face and ankles were puffy, my belly was bloated, my low back more stiff, and my mind felt less sharp. What happened?

My story is hardly unique. It’s the plight of 80 percent of the women in my functional medicine practice. The amount of fat in the body tends to be relatively stable and maintained within a narrow range, but with age, the tendency is for total body fat to rise, and in lockstep, for weight to increase. As your weight rises, so does your body weight set point (your brain-based control and regulation of a stable body weight). It dawned on me that my poor genes just carried out their orders from twenty-five thousand years ago: make her fat so she can survive. I struggled for several years as I faced my rising adiposity (a nice way of saying the fat concentration in my cells) and body weight. Then I learned about the link between the brain and weight—specifically how my brain was blocking my weight loss via its set point.

The upshot is that even a small amount of weight gain worsens inflammation, and the reason may trace back to the gut. Approximately 89 percent of people with obesity have bacterial imbalance or dysbiosis, as indicated by the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).4 These include overgrowth of bad bugs that relate to high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and lipid abnormalities. When you’re inflamed, weight gain occurs for a few reasons: fluid retention, insulin resistance, decreased thyroid function, poor sleep, diminished fat breakdown, and stress hormone imbalances. Weight loss may not completely reverse the problem, according to a study from Stanford University.5 (Don’t give up! You’ll see later in the chapter that weight loss can reduce inflammation.) After several years of dutiful research, I discovered a protocol for how to stop banking fat as I get older, and I’ll share it with you later in this chapter.

Subtle shifts are what we are about to address in the next part of the Brain Body Diet so that you can start feeling better right away, lose weight, shift mood toward the positive, and get the bigger payoffs of a healthier, stronger brain body in the years and decades to come. Our protocol goes deeper into specific hormones of the various set points—including body weight—gene/environment interactions, and, most important, the central role of the brain.

The brain regions that regulate food consumption and energy use also monitor how much fat you have in your body and respond to changes by offsetting your food behaviors and metabolism. All of this happens without your conscious awareness or control. Instead, you just hear a message in your head along the lines of, “You deserve another cookie,” which may get you to eat something that raises your set point. That’s what makes lowering one’s set point such a struggle: if you lose weight, your brain will tell your body to burn calories more slowly (i.e., lower your metabolic rate) and tell your mind to eat more. Your brain body adapts to weight gain and then resists weight loss. As an example, according to a recent study of The Biggest Loser weight-loss reality show, participants’ resting metabolic rate was still down 23 percent six years after the competition.6 The slowdown of metabolic rate, called metabolic adaptation, is often much greater than you might expect for a change in body composition—and as the study shows, persists much longer than you might expect.

Conversely, if you gain weight, you’ll most likely be less hungry and burn more calories because of the added weight, but insulin could be stuck in the fat-storing position, so you continue to pack on the pounds as your body aims for that higher set point (sometimes homeostasis is totally annoying). Women and ethnic minorities are disproportionately vulnerable to a rising body weight set point and obesity.7 As you’ll soon understand, a vital ecosystem exists between your genes, behavior, hormones, and environment when it comes to your body weight set point. That means it’s not as simple as giving up sugar or forgetting about stress (although they are important steps): understanding the brain/body circuits underlying these interdependent factors is crucial to achieving an optimal set point for you. In this chapter, you’ll learn how your brain works behind the scenes like a puppet master—and more important, how you can become the master of the brain/body connection that determines your set point.

To explain what you need to know about the brain/body axis, we will focus on learning about the body weight set point: how it controls body weight and is regulated by thoughts, beliefs, hormones, neurotransmitters, and microbes in your gut, many of which may conspire against you as you age. When you understand the targeted dietary and lifestyle changes (including supplements) that can help you achieve a sense of harmony between your brain and your body, you’ll be able to reduce the undesirable effects of metabolic adaptation. Overall, you will find in this chapter an evidence-based plan that I will show you how to implement with the determination and perseverance that lead to an enduring and lower body weight set point.

A final thought before we begin: go easy on yourself. Even though you perceive yourself as a single entity with a singular mind, the left brain looks in the mirror, sees the flaws, starts the analysis, and begins the diatribe, usually a rigid and degrading sequence of thoughts and criticisms, like a broken record. This is the type of extreme left-brain-dominated thinking that caused me to suffer. I don’t indulge my harsh and critical left brain anymore. In contrast, the right brain looks in the mirror and sees the whole being—right here, right now—smiling back, grateful, nurturing, nonjudgmental, and optimistic. The right brain knows the truth as expressed by Jane Fonda: we aren’t meant to be perfect, but we are meant to be whole.

Lowering your body weight set point requires a brain/body-based strategy and compassion. That includes the understanding that your worth is far more than just your weight or how you look in your jeans. Feeling disgusted when you look at yourself, even just in your mind, doesn’t help. The truth is that shaming or loathing yourself only perpetuates the presence of more stress, cortisol, and other fat-storing hormones and brain chemicals. You don’t have control over your first thought, but you have control over your second thought and that first action. Let that be about loving yourself unconditionally, without judgment or indulging the negative tactics of your inner saboteur.

Expanding your self-love to unconditional status requires a spiritual element, usually involving the understanding of your spiritual hunger, as well as a shift from left-brain domination to a place of contented balance between the two brain hemispheres. We will address this balance in the protocol. You’ll learn how to outsmart your set point accurately (a left-brain function) and how to maintain your new set point with more compassion and serenity (a right-brain function). You’ll also align your conscious goal—to be lean and healthy—with your brain’s unconscious goal—to keep fat on the body so you don’t die of starvation.

Do You Have Brain-Driven Body Weight Issues?

Do you have now or have you had in the past six months any of the following symptoms or conditions?

- Do you have a body mass index of 25 or greater, or are you unhappy about your weight?

- Are you noticing that your weight creeps up each year even when your lifestyle stays the same?

- Do you know what to eat but have trouble eating it?

- Do you experience cravings for sugar, bread, dairy, or grains?

- Have you diligently followed a diet and gotten partial results (i.e., lost weight), but then hit a plateau?

- Do you overeat even when you know better?

- Do you eat when stressed or feel other emotions like anger, sadness, or overwhelm?

- Do you have trouble sensing when you are full?

- Are you strict with yourself about what you can and can’t eat?

- Do you have a food plan that makes it difficult to eat anywhere but at home, leading to isolation from family and friends?

- Do you eat differently in public versus in private?

- Have you gained and lost at least twenty pounds more than once in your lifetime (excluding pregnancy)?

- After you lose weight, do you regain weight, even on restricted calories?

- Have you had recurrent episodes of eating large amounts of food, perhaps quickly, perhaps to the point of discomfort?

- Do you fear becoming fat and exercise or purge to make up for overconsumption of food?

- Do you feel self-loathing, guilt, or resentment when you stray from your food plan?

- Do you feel that restricting your food and tolerating hunger is the only way to maintain control and prevent weight gain?

- Do you feel like most of your energy goes into controlling your weight?

INTERPRETATION

If you said yes to five or more questions, you may have an issue with a rising body weight set point. Seven or more, and it’s highly probable that you have a problem. Of course, an increasing set point isn’t just cosmetic or isolated to how your clothes fit, but intersects with other physical issues such as the broken seven, blood sugar problems, metabolic syndrome, obesity, fatty liver, and (in women) postmenopausal breast cancer. While the symptoms of brain fog (chapter 4) overlap with other brain chemical imbalances, if you follow the protocol in this chapter, you will most likely feel better and be able to lower your body weight set point.

The Problem: We’re Fat but Don’t Know Why

It’s sad how poorly we understand why we get fat. The old thinking that I learned in medical school was that overeating and sedentary behavior were to blame.8 Later in my life, doctors still told me to eat less and exercise more. However, if that approach were true, why do 98 percent of diets fail? The traditional equation is overly simplified and fails to consider stress, sleep, hormones, behaviors, microbiota, gene/environment interactions, and, most important, the brain/body interface.

Some experts continue to blame “overnutrition” (i.e., overeating) and recommend gastric bypass surgery, but the procedure is costly, risky (complications in 17 to 37 percent of patients), and often unsuccessful9 (failure rates are 15 to 60 percent because postsurgical patients can continue to overeat by snacking continuously, and often the root cause of maladaptive eating behaviors has not been addressed10). Other experts blame our microbiota-harming lifestyle. We eat a Western diet and what food author Michael Pollan calls “food-like substances”: processed and adulterated food. As a result, we’ve lost bacterial diversity, and grown too many pathogens like E. coli, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa that promote the release of inflammatory messengers called cytokines.

Some experts villainize carbs and tell us to eat more bacon and steak. Others claim the problem is that we end up with too many of the microbes that extract excess energy from food and cause inflammation, leading to leaky gut, metabolic disorders, more inflammation, and weight gain.

Some researchers blame gut microbiota and the microbiome talking to the neuroendocrine system, especially the HPA (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) axis (the main stress regulation system). All you might notice is that you feel revved up and want pizza for dinner. (When overly stressed, the HPA axis may promote the growth of bacterial pathogens and yeast, thereby altering the gut-brain axis, making us inflamed and craving sugar, bread, grains, and dairy.11) Stress can cause the gut wall to be more permeable, allowing bacteria to cross the barrier and activate an immune response, which in turn alters the microbiome and can disrupt the blood-brain barrier. You guessed it: the HPA axis then goes wacky.

Neurobiologist Stephan Guyenet, a researcher who investigates the reasons for rising set point and how to fix it, points out another theory: many of the factors involved are not conscious.12 He notes that the human brain is hardwired to look for certain properties in food, and “it has a way . . . of sweeping aside your natural limits on intake.”13 Yet if the diet lacks one of those reward factors (like starch, sugar, fat, and protein), the brain is not as interested in eating as much of that food—so he says it’s the hyperpalatable food (lots of sugar and fat to boost tastiness) that contributes to a higher body weight set point. As in: “Ah, pepperoni pizza and beer, yes! Kale, not so much.”

Who’s right? Is the correct answer all of the above? My belief is that the root of the obesity epidemic is in all of these problems, a combination of complex and subtle interactions of the brain and body. Here’s what we know:

- Overeating may make you fat, but it is not the only factor. Despite dramatic changes in day-to-day food consumption, weight remains relatively stable over the short term for most humans and animals. Put another way, calorie input is not the only factor when it comes to weight.14

- Dieting leads to weight loss, but 98 percent of the time, the weight loss is not sustained, in part because of slowing metabolism and increased hunger and body weight set point. That means your frustration is scientifically warranted! Weight loss changes more than one hundred genes, most of which make you hungrier and more inflamed.15 As we covered in the last chapter, weight loss actually raises the body burden of toxins that make you fat—as you burn fat and liberate toxic obesogens,16 you need safe ways to dispose of them as you lose weight.

- Moving less does not cause obesity, although it can increase fat concentration and loss of muscle mass. Exercise is good for your brain and general health, but it isn’t a cure for obesity. At best, exercise helps modestly with weight loss and may be more important to prevent weight regain or maintain a lower set point.17

- Reduced sleep and chronic stress are part of the perfect storm of weight gain. Social and emotional factors affect food intake, exercise, mental health, set point, and weight over time.

- Cutting out carbs, while keeping calories the same, may not help you lose weight as much as cutting back on fat.18 Sorry, paleo and keto devotees. In a meta-analysis of thirty-two controlled feeding studies, researchers concluded that while the premise of low-carb diets is that they increase energy use and promote fat loss, when the diets substituted carbs for fat, lower-fat diets came out ahead in terms of energy expenditure and fat loss. (This matter is far from settled, but the data are in line with what I see in most of my female patients. Men seem to tolerate more fat consumption than women.) That doesn’t mean you need to eat a low-fat diet like we did in the 1980s, but rather that the latest high-fat craze may not be the best for every woman’s waistline.

- Additionally, the popularity of low-carb eating that began around 2003 may not be ideal for all women, owing to its effects on mood, thyroid, and HPA function, which reflect loss of brain/body homeostasis. It’s a delicate balance for each person.

- Getting the right food plan for your gene/environment combination is not just about cutting calories, cutting fat, or exercising more. The quality of foods matters, as does the setting for eating the food and the company around you. We are not eating our food during picnics in forests, but while commuting in cars on the freeway or over stressful lunch meetings.

- Fascinating differences exist among people who successfully maintain their weight compared with those who gain weight easily. Understanding the gene/environment interactions, particularly the hormonal components, of these extremes may lead to a better understanding of rising set point and obesity.

Body Weight Set Point

When it comes to weight problems, the brain is running the show. Yet this fact has not been fully recognized, appreciated, or honored in most discourse about weight gain and fatness. First, the brain is the source of your behaviors related to when you eat, what you eat, how much you eat, the type of movement your body performs, and regulation of body weight, fat composition, and hormones. Second, your brain is not necessarily rational in how it tells you to eat. In fact, past stress can make you eat more.19 Stress is not your brain’s friend; you’ll read a lot about its detriment to your most precious organ. Often the parts of your brain wired for survival will guide you to eat calorie-dense foods, even though you’re not at risk for food scarcity. So even though your nutritionist may say eat more salad, your brain tells you to order a pizza and beer, even that you deserve it. Third, when you gain weight, the brain uses all the tools in its arsenal—hunger, hormones, behavioral changes, and other physiological compensations—to make sure your body fat and weight retain the extra pounds. Your brain evolved in a way that it doesn’t want you to lose too much fat because you might starve to death—and rightly so, since the brain needs fat to survive. But it can be overprotective and consequently make your belly spill over your jeans.

The brain very carefully and intelligently sets a stable body weight for every adult. This is called the body weight set point.20 Your body weight set point is based on genetics, the amount you exercise, your nonexercise physical activity, diet, microbiota and microbiome, and hormone profile, particularly the hormones involved in appetite, stress, and reproduction. To keep it simple, I think of the factors underlying body weight set point as falling into four categories: genetics, hormones, behavior, and environment.

The set point theory holds that your brain strongly regulates and defends your weight at a predetermined point based on your body’s feedback loops. In practical terms, when you exercise more, you crave more food and the scale doesn’t budge.21 When you eat less, you get hungrier. It’s like a Neanderthal is in charge of your weight, not a modern and intelligent woman.

Humans are similar to animals when it comes to their set points: the hypothalamus is in charge.22 The hypothalamus is a brain structure about the size of a macadamia nut located near the center of the head, above the brainstem and just below the thalamus (the relay center for motor and sensory pathways), and acts in partnership with the pituitary gland, which hangs below it.

When you want to give up in frustration over your weight, keep a few facts in mind. It’s not just you or a lack of willpower; it’s a brain/body disconnection.

- Your hypothalamus orchestrates hormones and behavior as a result of environmental and body cues, so that means it governs set point and hunger, as well as other tasks such as sleep, body temperature, sex drive, and attachment to newborns.23

- When you overfeed a rat, its activity and metabolism increase and appetite decreases, so it doesn’t gain any weight—at least short-term.24 Humans do the same. Short-term, our bodies adjust. Long-term, not so much. The system is prone to disruption.

- Your body’s fat stores are subject to dominant and mighty—even foolproof—feedback regulation. That’s why lowering your weight and set point is so difficult. The medical term for this is energy homeostasis, or the biological process that controls body fat mass. Again, the hypothalamus is in charge.

- Defects in homeostasis lead to a rising set point. Here’s how that happens. On a molecular level, eating a typical Western diet high in sugar and saturated fat alters the body and brain in several ways. Outside of the brain, eating high-sugar and high-fat food injures neurons, triggers inflammation, and makes insulin resistance more likely. Inside the brain, a similar process occurs, impairing leptin and insulin signals regarding appetite, metabolism, and weight. The net result is that both your body and your brain become injured and inflamed, then insulin and leptin resistant, and next you experience a botched set point system in the brain.25

- It’s easier to gain than to lose. I know, that’s not surprising. But do you know why? Your genes and your body’s feedback signals (stress response, heart rate, metabolism, etc.) have developed such that humans defend weight asymmetrically: we fight against weight loss much more than weight gain. Weight gain doesn’t threaten our ability to survive like weight loss could, so evolution makes it much easier to gain weight than to lose it, and humans tend to get fatter as they age. Evidence comes from the fact that for most people, lost weight tends to be regained with time.26

It’s the adipostat—located primarily in your hypothalamus—that regulates the feedback loops of fat mass. You can think of the adipostat as a temperature gauge, or thermostat, but instead of regulating temperature, it regulates food behavior and energy use—how you burn or store fat. Short version: it adjusts your fat mass up or down with thoughts and behaviors depending on the cues it receives from hormones, neurotransmitters, and the environment. Most simply, it relays information about energy status from the body to the brain.27

Unfortunately, sometimes the adipostat gets confused—meaning it doesn’t always get the right messages from the rest of the body. If the hypothalamus has been injured or inflamed, it blocks the proper signals.28 Your body’s signals come in the form of dietary choices and the response of your endocrine system with the hormones leptin, ghrelin, and insulin, and the neurotransmitter dopamine.29 It’s like a room with a thermostat that is working properly, but a window was left open so the regulation, or homeostasis, of the room temperature breaks down. External and internal factors mess up the intended communication network, many of which you don’t know about, like toxins and behavioral impulses—and they make you eat when you shouldn’t. The brain also regulates other organs in the body, like the liver, muscle, and fat. All this conspires to make maintaining a healthy weight so challenging for many of us, unless we fix the breakdown in the communication network.

ADIPOSTAT

Definition: A proposed mechanism in the brain that regulates body fat within a narrow range based on food intake (energy input) and exercise (energy output). Location is in the hypothalamus, which coordinates the activity of the pituitary, especially hunger, thirst, sleep, emotionality, and other systems of homeostasis. The adipostat sets the metabolic status quo, like a thermostat for your weight, by compensating your eating and physical activity.

Body weight set point is hard to change, but it is well worth the effort. You simply have to adopt a new mind-set for the long haul, aided by sustainable lifestyle changes detailed later in the protocol (the usual: stress, thoughts, beliefs, and spirituality), by rewiring the brain circuits and avoiding metabolic compensation (the yo-yo dieting effect) from the various feedback loops in the brain. Then be 90 percent consistent. Consistency, as you’ll see, is the key.

The Perfect Storm: Colleen

Colleen started fighting with her weight in her twenties. A software executive, she was fine with her set point through college, when she weighed about 125 to 130 pounds. But then she hit business school and the scale topped out over 200 pounds. “I felt dead after ‘B’ school, and I was never the same after,” she told me. That’s when she started to stress-eat pretzels, crackers, and microwave popcorn, drink diet soda, and grab food on the go. She developed acne and was treated for months with antibiotics, wiping out her protective microbiota. Colleen didn’t eat in binges, but the combination of high work stress and eating to soothe herself led to problems with her hormones, contributing to a rising body weight set point, imbalanced gut flora, inflammation, and belly fat. She tried lots of diets, but it was always lose five pounds, gain ten. At our first appointment, Colleen was forty and weighed 218 pounds. Her blood pressure was high at 142/92.

Colleen’s labs revealed a classic pattern of inflammation, probably related to her borderline high (prediabetes) blood sugar and contributing to her borderline low thyroid function.30 Other measurements that were out of the optimal range included insulin, leptin, cortisol, and vitamin D. Before her genomics testing returned, we knew that she had the other three causes of a rising set point: behavioral (stress eating), hormonal (insulin block, leptin resistance, sluggish thyroid, high cortisol), and environmental (toxic stress).

We started a thyroid medication (see Notes for details), omega-3 fish oil at 4,000 mg per day, and a supplement to raise her HDL.31 I referred her to an excellent therapist who is focused on insight, solutions, and action. Instead of restricting calories, Colleen gave up the main foods that were causing inflammation, including sugar, alcohol, grains, dairy, processed food, diet soda, red meat, and high-fructose fruit (such as apples, pears, cherries, and mangoes). The structure of the protocol enabled her both to maintain a lower set point and to eliminate the cravings that were pushing her to foods that made her symptoms worse, and to make positive mind-set changes. Colleen started going to Zumba class again, four days per week. In all, Colleen dropped her set point by twenty pounds, not just by changing her behavior and what she ate, but by addressing the brain-driven weight issues.

After twelve weeks, Colleen looked and acted like a new person: her weight was 198 pounds and blood pressure was normal. Inflammation resolved and all of her hormones were in the optimal range, except leptin—it was significantly lower than baseline but took longer to normalize (see Notes for specific lab values).32 Colleen was thrilled with her progress and felt hopeful for the first time in many years about her body. I was thrilled too, because it’s far more important to focus on the long view, the slow and steady progress and sustaining that progress, than on unrealistic short-term goals or perfection. Science supports this approach. What Colleen and I kept emphasizing in our work together was to keep up the daily practices, the baby steps—the change in behavior, hormones, and environment—and most of all to celebrate and reinforce her progress.

The idea is not to achieve a super-low weight for one day through extreme measures; that’s impossible to maintain. When it comes to rewiring your brain, whether it’s set point or calming down your stress hormones, you want to make methodical, diligent steps—a little bit each day—over a longer period. This helps your brain body. Colleen is reversing her obesity, which in middle age is associated with a two- to three-fold greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease in old age and up to a fivefold increased risk of vascular dementia.33 It took Colleen twelve weeks, but she was very close to her new body weight set point (198 pounds) within the first forty days.

The Science Behind the Set Point

THE TWO TYPES OF EATING

Scientists describe two ways of eating. One is called homeostatic eating—you eat for nutrition’s sake, like Colleen when she lowered her set point and redefined her carbohydrate threshold. Almost no one in my family eats this way, so I had to learn about it from some of my friends. Not surprisingly, there aren’t many of them who eat simply because food is fuel, and the ones who do are thin. The other type is hedonic eating—you eat for the pleasure and reward of food.34 My family considers hedonic eating to be normal: I grew up in a home where my mother and grandmother constantly talked about new recipes to try, their weight, and their latest diet.

The problem is that in certain vulnerable people, like me, hedonic eating leads to weight gain and food addiction. Hedonic eating probably reflects adaptations we’ve made over centuries in the reward circuits in the brain. Morphine-like chemicals in food containing gluten (gluteomorphins), such as bread, or in dairy (casomorphins), such as cheese, may account for addictive properties. In fact, brain scans of hedonic eaters show alterations in the brain areas linked with reward, motivation, memory, learning, impulse control, stress reactivity, and interoceptive awareness.35

Hyperpalatable foods with high levels of sugar and fat are the most addictive, leading to craving, bingeing, and withdrawal in rats, similar to what we see with addictive drugs.36 Women are four times more likely to be food addicts compared with men.37 Some people have something called “high opioidergic tone,” meaning that eating hyperpalatable food makes you feel pleasure as if you just took heroin or morphine.38 Craving a food reward, like chocolate, is mediated by the nucleus accumbens, the reward center in the brain.39 While it has not yet been proven conclusively, scientists hypothesize that chronic overfeeding with hyperpalatable foods weakens the body’s natural reward response, which can increase your cortisol response (hello, stress!) and increase your drive for food.40 More simply, food acts like an addictive drug. The only variable that lowers the odds of having severe food addiction is vegetable intake—veggies truly are the superheroes of the story.

Even diet soda can make you fat. I grew up drinking diet soda of one type or another, thinking it was safe. Turns out that daily consumption of diet soda is associated with escalating abdominal obesity: i.e., your waist keeps growing.41 Twenty-five percent of children and 40 percent of adults in the United States consume low-calorie sweeteners.42 Low-calorie sweeteners disrupt the delicate balance of gut microbiota, making a person more likely to have blood sugar and metabolism problems,43 increase weight and waist circumference, and are linked to a higher incidence of obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular events.44 Artificial sweeteners: a good idea gone wrong. No more diet soda if you want to lower your body weight set point! No more artificial sweeteners, and limit natural sweeteners like stevia, too, because some people have a hypoglycemic response.

While I don’t think we all need to eat like robots, devoid of pleasure, hedonic eating is risky, particularly when your set point is rising and your BMI is 25 or greater. If you’re falling prey to using food in unhealthy, hedonic ways, the risks are increased cravings, more stress, weakened pleasure response, and food addiction. Food isn’t a friend, lover, or de-stressor.

WHAT CONTROLS THE ADIPOSTAT

Like me at age forty-eight, maybe your fat mass or weight is higher than desired and you want to lower it. That means taking on your body’s set point and the adipostat—the gauge in your brain that regulates body fat based on energy input (food) and energy output (exercise)—which can be extremely difficult. Your fat manipulates your brain, which then manipulates your body in order to preserve itself. The fat/brain/body conversation has evolved over millions of years to perform this function. Evolution wants you to be a little fat, so there’s a reserve when food is scarce. One author described this manipulation as a secret conversation between fat and the brain, and I agree. Losing weight and keeping it off requires us to convert that strong-willed adipostat from enemy to friend by using the steps in the protocol.

Now we also understand that obesity and extra weight are associated with chronic inflammation in the body. Here’s the science on how being overweight can lead to inflammation: it causes abnormal cytokine production (cytokines, or chemical messengers, are secreted by certain immune system cells and affect other cells); increased acute-phase reactants (proteins whose serum levels increase or decrease in response to inflammatory cytokines and are thus markers for inflammation); and activation of inflammatory pathways.45 The inflammation exists both in circulating immune cells, called mononuclear cells, and in adipose tissue (fat).46 In simple terms, increasing levels of inflammation ruin feedback loops and may make you fat by raising your set point. The good news is that weight loss of even 5 percent reduces cytokines and inflammatory pathways and increases anti-inflammatory molecules in obese people compared with controls.47 Plus, decreasing inflammation benefits the entire body, not just your weight-loss control center.

Genes, Body Fat, and Weight Gain

When I ran my first genetic profile, I was unhappy to discover my high genetic risk for a rising set point, weight regain, and obesity.48 While weight gain is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, genomics determines up to 20 percent of BMI.49 Not surprisingly, these genes exert their influence mostly on brain signals that direct behavior, especially when to eat, how much to eat, and when to stop, and, occasionally, on stomach, fat, and pancreatic hormones. But remember: the other 80-plus percent is determined by the choices you make. While several genes have the strongest influence on set point, consider that this topic of the gene/environment interaction is rapidly evolving and complicated. You can’t blame one gene; it’s the gene interacting with your environment that governs your set point, and it’s important to consider the entire orchestra of your genes (your genome) interacting with each other.50 That said, here is a sample of the current panel of genes involved in set point and weight gain (read more details in the Notes section):

- Fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO). This gene is strongly associated with your BMI and your risk for obesity and diabetes.51 When you have the variant, it gives you poor control of leptin, so you’re hungry all the time.

- Melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R). The gene MC4R works in the brain’s hunger center, and when normal, it tells the body, “Stop eating.” Certain variants make you more likely to overeat the wrong foods, especially when stressed.52

- Leptin receptor (LEPR). Snacking can be good or bad for you, but when women have the G/G variation in the leptin receptor, they are likely to snack more.53

- Adiponectin (ADIPOQ). The ADIPOQ gene variations can cause problems with your adiponectin hormone levels in the body, making you more likely to become obese, develop diabetes, and regain weight.54

- Adrenergic beta-2 surface receptor gene (ADRB2). I call this one the takes-me-twice-as-long-to-lose-weight gene. ADRB2 is associated with fat burning and distribution.55

- Dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2). Variations may make people more likely to overeat and behave addictively.56

- Other: Many other genes have been proposed and are under investigation.57

Should I get my genes tested if I really want to understand how to lower my set point?

Answer: You don’t need to test your genes to benefit from the Brain Body Diet and lower your set point. However, I understand the desire to learn about your personal genome and how to work with it more strategically. Remember that your genes control less than 20 percent of your set point, but if you want to know them and perhaps modulate their expression, refer to Appendix B for specific labs that I recommend.

For Some People, Plant-Based Is the Answer

Maria, age seventy-three, juggled kids and career for decades and made an effort to eat well, exercise moderately, and keep a connection to her spirituality for sanity and balance. But over the years, each decade brought another ten pounds. Fifteen years ago, she joined Weight Watchers and managed to lose the twenty extra pounds that she found unacceptable. But she didn’t bolt once she lost the weight; she stayed the course. Maria maintained her new set point by weighing in monthly to maintain her lifetime member status and to keep herself connected to the Weight Watchers community, and by internalizing good eating habits. “There are some foods I just don’t eat [or hardly ever eat],” she says. Pizza maybe two or three times a year, pastries almost never.

Although she was pleased to lose the twenty pounds, she felt stuck at a set point of 147. Her weight would fluctuate around holidays and during vacations, but she was able to stay below her Weight Watchers goal weight. Then, several months ago, her husband’s doctor ordered him to become a vegan because of health problems. Maria does not eat vegan—she eats eggs and some animal protein at home and usually orders fish when they eat out, but most of their meals at home now revolve around beans, vegetables, and healthy grains. Within a month, her husband’s labs improved dramatically—and Maria’s weight dipped below 140. Her weight has hovered closer to 140 than 150, and she believes her new set point will be 142. Maria thought she was doing everything right, but found when she adapted to her husband’s new regimen, her body gave a resounding Yes! Sometimes, with your set point, you can change just one thing—shifting your diet to be mostly plant-based—and your set point drops. One alteration can change several of the conversations that impact your set point, and ultimately, things improve.

Toxins That Affect Weight

Many of the toxins you read about in chapter 2 were obesogens, environmental chemicals that conspire to stimulate fat production and storage. Obesogens have been the subject of vigorous research for the past ten to fifteen years. Scientific interest evolved from the observation that the rising epidemic of obesity and the massive output of industrial chemicals were not just coincidental, but most likely related. Over time, we’ve begun to learn that certain environmental toxins change metabolic regulation in the hypothalamus.58 From there, environmental toxins can alter lipid balance, weight, cholesterol levels, signaling pathways, and protein production in many animals, including humans. As noted in chapter 2, most obesogens disturb insulin pathways.59 Due to their chemical structures, many of these toxins cross the blood-brain barrier and placental barrier, and mimic or disrupt hormones. Prenatal exposure to some obesogens can have effects that last more than one generation.

If you weren’t convinced already about the danger of toxins to your brain, maybe understanding their impact on your weight and set point will seal the deal. Below are the most common obesogens and where to find them (see more obesogens in the Notes section).60

- BPA (register receipts, plastic bottles, and canned food): BPA is one of the best understood obesogens.61 Prenatal exposure can even make you less motivated to exercise, plus they change the metabolism of carbohydrates versus fats, at least in mice.62 One type of BPA, a flame retardant (tetrabromobisphenol A), damages the cells that produce insulin, increases adipogenesis, and promotes inflammation.63

- Mercury (fish and dental amalgams): Mercury in the blood is positively associated with increased BMI, visceral fat, and increased waist circumference.64

- Phthalates (perfumes, air fresheners, shower curtains, and scented lotions): Phthalate levels in the body correlate with increased waist circumference, body fat, and obesity, including from prenatal exposure.65

- PFOA (nonstick pans and microwave popcorn): PFOA can raise leptin and insulin levels in exposed mice, even at low doses, which is associated with increased weight in midlife.66 PFOA also affects thyroid function, and when you mess with the thyroid, you mess with body weight set point.67

- Mold (in your food, under your sink, and behind your dishwasher): Mold is in certain foods, such as grains, alcohol, apple juice, and coffee.68 Mold toxins disrupt the function of insulin and leptin.

On a more positive note, your natural hormones may help protect your brain from toxins. Hormones made in the adrenal glands and ovaries, such as estrogen and progesterone, can pass through the blood-brain barrier and protect brain cells from oxidative stress and damage from many toxins, including mercury.69 You can think of the brain and ovaries as sanctuary sites, protected areas that are hard to penetrate, whether by prescription drugs or other foreign substances and toxins. Estrogen and progesterone and their protective by-products can create a sanctuary in your brain from toxins. (Of course, a leaky blood-brain barrier may still allow toxins and other foreign substances to enter the brain.) Additionally, the brain has its own endocrine system and can produce sex hormones, known as neurosteroids, that can protect the central nervous system.

A CLOSER LOOK AT FAT AND APPETITE

Fat isn’t all bad. When fat is behaving properly, it secretes the proper amount of leptin, the hormone that suppresses appetite; and adiponectin, which removes glucose, fat, and toxic lipids from blood. The problem is that if your weight is creeping up or is higher than is healthy for you, these hormones—maybe even a neurotransmitter or two—are most likely misbehaving. For example, while it’s true that eating a normal amount of healthy fat won’t make you fat, in postmenopausal women, eating more fat may raise ghrelin, the hormone that tells you to eat.70 As noted above, you need to find your own sweet spot when it comes to the quantity of healthy carbs and healthy fat, keeping in mind a recent article from The Lancet showing that eating excess carbs is associated with earlier mortality.71

Hormones and Neurotransmitters of Weight, Appetite, and Set Point

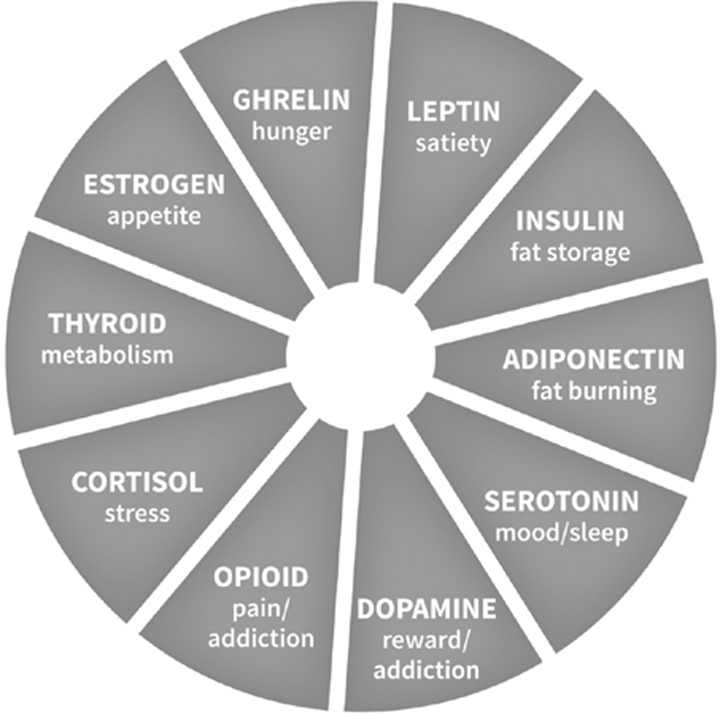

Hormones drive what you’re interested in, and food is no exception. The figure below shows the most common hormone imbalances that interfere with normal eating, weight, set point, and fat storage. You’ll learn in the protocol how to bring these hormones under control. We will deal with the brain chemicals dopamine and opioid in chapter 5.

Hormones and Neurotransmitters of Set Point

GHRELIN, THE “HUNGER HORMONE”

Ghrelin is called the hunger hormone because it tells you when to pick up your fork and start eating.72 In this way, ghrelin is the counter hormone to leptin, the hormone that tells you you’re full and it’s time to put down the fork. Your brain may have evolved to ignore ghrelin so you didn’t starve when food was scarce, but it didn’t learn to override that impulse in modern times when food became plentiful.73 Ghrelin is produced in the stomach but is very active in the brain, especially the hypothalamus and the nucleus accumbens. (Read more about the details of ghrelin in the Notes.74) Bottom line: too much ghrelin is a barrier to losing weight because it increases appetite and subsequent food intake.75 The more ghrelin in your system, the hungrier you are. As such, we want to lower your ghrelin in order to lower your set point.

LEPTIN, THE SATIETY HORMONE

Your fat cells secrete leptin, the hormone that regulates appetite, satiety, and energy expenditure, telling the hypothalamus how and when to burn energy.76 Based on your leptin pathway, you may have a fast or slow metabolism at rest.77 When you eat a typical Western diet high in sugar and saturated fat, your cells are at risk of becoming numb to the leptin signal, so your fat cells start to overproduce it, making you inflamed and then more fat by lowering adiponectin (see here).78 The more fat cells your body makes, the less your brain is able to let you just put down the fork.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) also plays a dynamic role in regulating leptin levels. Leptin is transported from where it’s made in fat tissue to the brain via the BBB. But once you develop high insulin and insulin block, the resulting high blood sugar appears to increase the transport of leptin across the BBB.79 Upshot: people with leptin resistance feel hungry, rarely feel full and satisfied, and tend to be overweight or obese. If your leptin is in control, you’ll start to feel satisfied with modest amounts of food—the right amount for you and your set point. You want balance, with just enough leptin (not too high) and adiponectin (not too low).

INSULIN, THE BLOOD SUGAR HORMONE

You may not be diabetic yet, but you could be experiencing other telltale signs: you can’t lose fat no matter what you try, and maybe you’re tired because the glucose in your bloodstream can’t get to your muscles to feed them and keep you strong and energized. Maybe your doctor explained your fasting blood sugar is borderline, or your triglycerides are too high, or your good cholesterol (HDL) is too low. Maybe you have been diagnosed with hypertension, atherosclerosis, fatty liver, sympathetic overactivity (too much stress), hypercoagulability, or high insulin levels.80 All of these symptoms and conditions are related to the root cause of insulin block or resistance. Insulin block is common, found in about 41 percent of obese patients and about half of Americans.81 The main cause is eating more carbohydrates than your body can tolerate, leading to carb intolerance and rising insulin, which in turn causes inflammation and rising body fat. (See Notes.82)

When your insulin is blocked for too long, your brain tells your body to store the fat for future use, which means that your set point has to go up to accommodate the new stores. When your diet includes liquid sugars (cocktails, soda, juice) and excess carbohydrates in the form of bread, pasta, and potatoes, your cells become blocked to the effects of insulin. Science confirms: eating too many carbs is associated with early mortality in a prospective study of more than 135,000 adults followed for 7.4 years.83 As we sort out the details, stay away from processed, packaged foods and refined carbohydrates, and get your carbs from one to two pounds of vegetables per day. If you’re currently overweight, you are probably experiencing insulin block because your cells’ ability to respond to insulin declines as fat composition rises. Insulin disposes of sugar that’s in the blood, so when the action of insulin is blocked, your blood sugar rises too high or too fast or both. Rapid changes in blood sugar can stimulate cravings, weight gain, and systemic inflammation. Insulin rises, and so does fat storage, as the body increases the demand to keep blood sugar even. Your body has to do something with all of that extra blood sugar, so it turns it into fat for later use. That was a neat trick when we were hunter-gatherers surviving a famine, but now it makes us fat and unhappy.

Insulin resistance also affects your brain. When your brain is insulin resistant, it affects more than just your set point and eating behavior; it also affects your cognition, memory, reward system, and whole-body metabolism.84 It’s another grave brain/body setback. High insulin levels in women act on the neuroendocrine system and can cause it to pump out large levels of sex hormones, leading to a greater risk of polycystic ovary syndrome. So you want to keep your insulin in check to promote whole brain/body health.

ADIPONECTIN, THE FAT-BURNING SWITCH

The more fat you have, the lower your adiponectin levels. Inflammation increases as adiponectin drops.85 Visceral fat accumulation is associated with lower circulating adiponectin levels, too. On the other hand, the more adiponectin you have, the less inflammation you have and the more fat you burn. It follows that when you lack adequate adiponectin, you have great difficulty melting fat and staying lean. That’s why losing fat can be so challenging. In the protocol, you’ll find the proven ways to boost adiponectin naturally and safely so that you can burn more fat.

CORTISOL, THE STRESS HORMONE

Your body secretes cortisol in response to the brain’s perception of stress. Cortisol cranks up the sympathetic nervous system, so that you can be ready to fight or run. As I’ve described in all of my books, this is a good adaptation for the occasional danger, but cortisol levels are often far higher than the human body can properly handle. Chronically elevated cortisol levels cause fat storage in the abdominal area. Even worse, the more abdominal fat you have, the more cortisol you produce in response to stress, which then causes more abdominal fat to be deposited. Talk about a vicious cycle! Stress becomes embedded psychologically and biologically. It can affect your HPA axis function, your cortisol levels, and all aspects of food behavior: how you eat, the food you crave, and how much you eat. Women experiencing high levels of stress have a higher BMI, more emotional eating and cravings, and more visceral fat.86 High cortisol can break down your muscle for energy, which is bad for weight loss because it lowers metabolism further. When you don’t respond well to stress because of past traumas, exposure to stress increases your chances of eating more calories.87 This is one of the key intersections between the brain and the body that is most often overlooked when it comes to weight gain and weight loss. (We’ll address stress and the brain more in depth in chapters 6 and 7.)

THYROID, THE HORMONE OF METABOLISM

The thyroid affects nearly every cell in your body by telling it to turn up or down your metabolism. When thyroid function is low, you feel tired and depressed, retain fluid, and most likely will gain weight. Your thyroid gland is in your neck, but your hypothalamus controls it. You need your hypothalamus to provide adequate levels of both the storage thyroid hormone (T4) and the active thyroid hormone (T3) in order to feel your best and have a normal body weight set point. Your labs can be normal while you’re still not doing a good job of converting T4 to T3 in the brain, possibly because of genes or inflammation. As a result, your brain gets confused and slows down metabolism, even though your thyroid labs are normal. (See Notes for how to check for the gene variant88 and, if you have it, talk to your doctor about more judicious use of a T4 plus T3 medication.89) Furthermore, sealing a leaky gut will also help reduce autoimmune attack of the thyroid, which is the cause of most cases of low thyroid function. Experience also suggests that each person with thyroid issues may have a physiological optimal range that’s more narrow than laboratory-quoted normal ranges, which implies the existence of an encoded homeostatic thyroid set point that is unique to the individual.90

ESTROGEN, NATURE’S APPETITE SUPPRESSANT

Estrogen has hundreds of jobs in the body, but did you know it’s an appetite suppressant and it promotes energy expenditure?91 That’s part of the reason why women gain weight after menopause. Estrogen replacement can reverse the effect. You may already know that 17β-estradiol, a type of estrogen, protects tattered brain cells.92 So it makes sense that estradiol may prevent the brain from making you eat more and burn fewer calories. I favor hormone therapy in the right person, with the right genetics. The decision ultimately varies person to person and must be individualized (see Appendix B for suggestions).

On the other hand, too much estrogen is a problem. A rising set point and obesity are associated with increased aromatase, an enzyme that increases estrogen production in fat tissues, leading to excess estrogen and a greater risk of certain types of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.93 The key is to have the right amount of estrogen for you: not too much so it promotes breast cancer, and not too little so it promotes appetite and slows metabolism. Knowing what’s just right is a matter of measuring symptoms and laboratory tests, as described in the Advanced Protocol.

It’s Not as Simple as Giving Up Carbs

Turns out that insulin block was the primary defect leading to my increased fat composition when I tried the “bod pod.” The main way I fixed it was with intermittent fasting, along with a plant-based, add-fish-and-eggs diet, as you’ll learn about in the protocol. A high-fat, moderate-protein, low-carb ketogenic diet did not work for me. Later I learned that intermittent fasting protects the brain against cognitive decline created by inflammation, and it all started to make sense.94

I wish it were as easy as removing most carbs to reset insulin. In a one-year trial of weight loss, eating low-carb results in the same weight loss as low-fat—but causes more mood problems.95 Other studies show impaired mood and cognitive function on low-carb eating—along with other imbalances such as decreased thyroid, low testosterone output, higher cortisol levels, gut dysbiosis, poor muscle building and athletic performance, suppressed immune function, and fatigue—sometimes leading to lower motivation to exercise.96 On the other hand, low-carb diets and low-carb ketogenic diets may help to reset insulin levels in some people with obesity or metabolic syndrome.97 The takeaway is to get insulin working for you so that inflammation and body weight set point are lower.

I don’t want to give a rigid rule about how many carbs or how much fat or protein to eat, however, because I believe it depends on the gene/environment interaction—your DNA, your stress level, how much you exercise, and the current state of your insulin pathway. Short version: you want to match your carbs to your DNA and lifestyle. My husband is a low-fat genotype; he regulates carbs based on his daily exercise but can eat more carbs than me without raising his set point. I’m a low-carb genotype; I gain weight easily on carbs and need to watch them carefully to maintain my lower set point. For me, that means a maximum of about two ounces of carbohydrates per day (steamed sweet potatoes, yuca crackers, purple potatoes), and more if I’m stressed or exercising more. Grains raise my blood sugar too much for at least two hours—and cause carb intolerance for me, which shows up as bloating and weight gain. So you need carbs for mood, cognition, and thyroid function—just not too much. There is no one-size-fits-all rule, but one of the easiest ways to prevent carb problems with your insulin pathway is to intermittently fast, which can reset insulin, fatty liver, and obesity, shifts the microbiome in a positive direction, and turns white fat beige.99 In this protocol, you’ll lengthen the amount of time you spend intermittently fasting so that you can lower your set point by burning more fat, liberate the obesogens stored in your fat, and reset your set point hormones.100 As you’ll learn, you want to remove refined carbohydrates but continue to get healthy levels, primarily from vegetables and fruits. For maintenance, more fat and fewer carbs may be best, but you have to do your own personal research to confirm.

AVOIDING THE OBSESSION WITH WEIGHT

While I want to avoid the persistent rise in set point and body weight, I also want to avoid an obsession with a few pounds, because that can lead to anxiety (chapter 6), another disaster for your brain. I’d recommend the same for you. In her essay “Fatness and the Female,” Jungian analyst Ann Belford Ulanov states, “Many women today feel haunted by an obsession with weight. Though in no way psychotic or afflicted with such gross disturbances as obesity or anorexia, these women know the full force of a neurotic preoccupation with food.”98 Ulanov nailed it. We aren’t talking about women who are morbidly obese. That’s because it’s not just about the weight; it’s about a deeper spiritual hunger. “She knows she is entangled in a classical neurotic conflict: the means of dieting she employs to control her obsession with food only tie her more securely to a compulsive preoccupation with it.” In other words, we displace unmet needs onto food and obsess over unattainable weight goals. As you consider your body weight set point, is it rational for your body shape? What would your wiser, older self recommend about a realistic set point for you?

The Slow Creep: Kim

At age forty-two, Kim rated her health as “2/10” (“1” is sick, barely surviving, and “10” vital), way too low for a young woman in her prime of life. Her main goal was to lose twenty pounds, and in the process deal with her mood swings and fatigue. Even though her eating habits and workouts were unchanged, her main issue was the fat that showed up around her middle after beginning an antidepressant for work/life issues—including a job she hated, a boss she loathed, and a husband with whom she rarely had sex. Her primary care doctor had started her on an antidepressant, a combined selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) called duloxetine (brand name Cymbalta, 60 mg), which did nothing except cause her to gain weight. Her doc promised that Cymbalta was a “weight-neutral” antidepressant, but the truth is that it causes nighttime sugar cravings and weight gain in susceptible individuals like Kim. When Kim asked about her increased sugar cravings and weight gain, her doctor said it’s not the drug, it’s you. The weight gain only made her mood worse. In desperation, Kim went to a “fat doctor” who added the appetite suppressant phentermine, 37.5 mg, to her list of medications. Kim wanted to lower her current set point, which rose on the antidepressant, back to normal. She found me during a desperate search online and traveled hours to see me for help.

Summary of what we found and the actions we took:

- Reason for rising set point. Sixteen to 55 percent of patients on antidepressants like duloxetine gain clinically significant weight.101 Kim started to wean off the duloxetine with her prescribing doctor’s help to manage withdrawal symptoms. I recommended other methods to support her mood and energy, like kundalini yoga every morning for fifteen minutes, working with a life coach about her job and marriage, and taking methylated folate, fish oil, N-acetyl cysteine, and spirulina.

- Stress. We measured Kim’s hormone balance with a helpful test of her growth-and-repair in proportion to her wear-and-tear hormones, also known as the anabolic-to-catabolic ratio.102 Her ratio was 0.8, so she had more wear and tear occurring in her body—which caused her body to sense that Kim was in a crisis and drove her body to store fat. (See Notes for Kim’s laboratory values.)103

- Hormones. Kim had way too much of an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, produced by specific bacteria in her gut, and that meant she was blocking the detoxification of toxins like carcinogenic estrogens—the enzyme kept recirculating the same bad estrogens and wouldn’t let the gut remove them. Higher levels are linked to excess estrogen in the body and colon cancer. Limiting fat and meat in your diet and eating more vegetables and fiber lower beta-glucuronidase.

- Dietary changes. Kim cut out flour, sugar, and alcohol. Kim’s fecal pH was low, meaning it was overly acidic. In Kim’s case, she was eating too much conventional red meat, like burgers with her kids at a local restaurant during the week. Proper pH levels favor the beneficial microbes in the gut, deter possible pathogens, make digestion smoother, and promote short-chain fatty acid production. Besides the possible influences listed here, an acidic pH may also result from malabsorption of sugars in the intestines.

- Genes. Kim had several gene variations involving serotonin, which may have contributed to her rising set point on the antidepressant. Taking a bioactive form of vitamin B6 (as pyridoxal-5-phosphatase) was very helpful at helping serotonin soothe her brain.

- Toxins. Kim’s mercury level was very high, probably from five amalgam fillings and two crowns. Kim started the Quicksilver Protocol to reduce mercury (see Appendix B). She was working with a biological dentist to replace her mercury-containing dental work.

The Brain Body Protocol: Lowering the Body Weight Set Point

When it comes to lowering your set point, take the long view. Consistent mind-set and discipline, avoiding the yo-yo weight loss/weight gain pattern and hormonal nudges, and behavior modification are what work. When you change your environment, you change the cues to your unconscious brain and gene expression. We don’t need to follow the rules of a survival game that no longer exists. We can work around our ancient brain circuits that favor a rising set point by promoting neurogenesis, reducing inflammation, and protecting the blood-brain barrier.

Just as the Toxin Protocol needs to be done for forty days to achieve results, if your set point is rising, perform the Set Point Protocol for forty days or longer. Perhaps start with one step and be consistent for a week. Once it becomes habit, add another step if you’re still not seeing changes.

MACRONUTRIENTS

You know what worked for previous generations? Let’s look to the 1960s, before the obesity epidemic began. Americans ate 45 percent of calories from fat, about 33 to 34 percent from carbs, and 20 to 21 percent from protein. We ate less meat, cheese, and grains (especially corn) compared with 2015. It was a healthier macronutrient combination that existed before fat became demonized by Pritikin, Keys, and Yudkin. When Americans then cut the fat over the next few decades, waistlines grew.104 While I’m not suggesting that this macronutrient profile is the best for all, it’s a reasonable starting place to then determine your best macronutrient ratios.

- Define your carbohydrate threshold. Eat the maximum healthy carbohydrates that you can while getting to or maintaining your new set point. That means you need to define your carbohydrate threshold through personal experimentation. Most people need about 10 to 35 percent of their total calories per day from carbohydrates, but it depends on your insulin pathway, stress levels, and microbiome function, among other factors. People with thyroid, adrenal, or mood issues—or a high level of physical activity—may need more. For most women, the typical range is 50 to 150 grams of carbohydrates (15 to 30 percent of calories on a 2,000-calorie diet), and for men 100 to 200 grams of carbohydrates (on a 2,600-calorie diet). Here’s how you do it: start with about 50 grams of carbohydrates per day for women. Stick with it for two weeks, then try the middle end of the range for two weeks, then try the higher end for two weeks. (My carb threshold for weight loss is 50 to 75 grams per day as part of a 2,000-calorie diet and, for weight maintenance, about 76 to 100 grams.) For the intrepid biohacker, consider testing your blood sugar with an inexpensive home kit two hours after eating a known amount of carbs (see Notes for details).105

- Minimum protein. Eat the minimum amount of protein that preserves your muscle mass. For most people, that’s 0.8 to 1.0 grams of protein per pound of lean body weight to lose fat or maintain weight, and 1.0 to 1.25 grams per pound of lean body weight to gain muscle or improve performance. For me, that’s four ounces of most kinds of protein (such as fish, beans, chicken, turkey, whole tofu) at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Or two eggs, or two ounces of nuts or seeds. Or pea protein in a shake. Or pulses, such as beans or lentils. Overall, most people do well with about 20 to 35 percent of their calories from protein.

- The rest in fat. Eating healthy fats improves your health. But don’t eat foods that combine high fat and high carb (like French fries or chocolate cake): it raises ghrelin in postmenopausal women with insulin block. Aim for the remainder of your calories from healthy and unprocessed fats, like avocados, olives, and macadamia nuts.

BASIC PROTOCOL

Step 1: Eat for blood sugar balance.

Follow the guidelines from the Toxin Protocol in chapter 2 for food with the following refinements.

- Upgrade your set point environment. You want your food cues at home to be good for your brain. Colleen got rid of calorie-dense trigger foods at home by donating them to a local food bank. She cleared the decks: no more visible food sitting out on kitchen counters or luring her at night. As she started intermittent fasting, she closed her home kitchen at 7 p.m. She knew that the break room at work was full of tempting foods that she used to love, like pretzels, chips, and crackers. For the sake of her brain, she stopped going to the break room while following the Brain Body Diet. Instead, for the long days at the office, she brought a bag of food with her that included cut vegetables, healthy proteins like nuts and seeds, and a big salad for lunch, or leftover vegetables and protein from the night before. If you tend to feel like eating more than you need, consider weighing food with an inexpensive kitchen scale. It’s a fidelity thing: just as you wouldn’t cheat on your life partner, stop cheating on yourself. These efforts set up a better food environment that will support you in intentional eating and improve the cues you send to your unconscious brain.

- Curb your carbs. Studies show that counting and reducing carbs leads to improved blood sugar and weight in the short and long term.106 If you are overweight, it’s likely that you have a problem with carbohydrate metabolism, and a low-carbohydrate approach can help.

- Eat in a way that doesn’t inflame your brain (i.e., your hypothalamus). This means getting the right balance of fat and carbs, improving the health of your gut (microbiome), and scheduling your meals. Specifically, we are keeping your hypothalamus, the boss of your hormones, cool and chill. One key is to avoid a low-calorie diet, because it makes your fat cells hoard calories and leads to overeating. At the same time, watch your body’s response to saturated fats. Some people do well with healthy saturated fats, such as pastured butter and coconut oil, but some gain weight.

- Continue to intermittently fast. Increase from once or twice per week to five to seven days per week. Remember that intermittently fasting is much easier than dieting, because you are not restricting food—you’re simply limiting your feeding window, like animals in the wild. Continue from chapter 2 with a twelve-hour eating window, such as finishing dinner before 7 p.m. and then having breakfast at 7 a.m. Try it two107 times per week on different days (not continuous) for weight loss, and add another day if you don’t see your set point drop. A longer fast of thirteen to fourteen hours, even sixteen hours (see Advanced Protocol), is associated with a better insulin pathway. Adjust the hours to fit into your schedule.

- Consume a mostly plant-based food plan. It lowers blood sugar, inflammation, and weight.108 Start eating meals planned totally around plant-based foods. Increased soluble fiber helps to balance blood sugar.109

- Eat more vegetables. The only variable associated with less food addiction is vegetable consumption; vegetables also provide the fiber to reset ghrelin110—aim for at least one more cup per day, or a scoop of greens powder added to a daily shake. Ideally consume one to two pounds of vegetables per day.

- Include in your diet chromium- and magnesium-rich foods. Foods high in chromium include eggs, nuts, green beans, and broccoli. Foods high in magnesium include dark leafy greens, fish, extra dark chocolate, and avocados. Both can reduce your risk of nutrient gaps associated with blood sugar problems.

- Add probiotic food. You can eat more coconut (nondairy) yogurt, kefir, miso, tempeh, beet kvass, fermented chili paste, pickles, kimchi, and sauerkraut. Sauerkraut and kimchi may have as many as one million to one billion live microbes in each gram.111 Start with a small amount, such as one or two tablespoons at dinner, and build up to one-half cup (four to six forkfuls) per day. Take care of your microbiome by eating prebiotic and probiotic food, consuming plenty of fiber by gradually increasing day by day, avoiding antibiotics if you can, and limiting red meat.112

- Enjoy wild fish. Eat low on the food chain, including small fish like salmon, mackerel, anchovies, sardines, and herring, in addition to the fish listed in chapter 2. If you consume poultry, make sure that it’s pastured and free of hormones and antibiotics. Purchase directly from butcher counters and get poultry wrapped in paper, not prepackaged in plastic.

- Watch your food thoughts. You will still have food thoughts—like I must eat a bar of chocolate now, or I deserve a big hunk of pie—but you don’t have to act on them. Create a gap between stimulus and response, as recommended by renowned neurologist, psychiatrist, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl: “Between stimulus and response lies a space. In that space lie our freedom and power to choose a response. In our response lies our growth and our happiness.”113 Listen to his wisdom, and honor the wisdom of your body. We’ll talk more about making contact with your inner self and honoring the sacred throughout this book.

- Control stress levels. High stress can raise blood sugar and set point.

TRUE HUNGER VS. FALSE HUNGER

Most of the busy women I know are hungry. Stress makes them hungrier. Yet sometimes what feels like physical hunger is not that at all, but emotional or spiritual hunger, such as a need for affection, affirmation, understanding, competency, accomplishment, or a deeper connection. Or maybe what first seems like hunger is even something else, such as anger, loneliness, or tiredness. A tool called HALT can help you reclaim the brain/body connection:

- Pause for a moment.

- Ask if you’re feeling hungry, or is it anger, loneliness, or tiredness (HALT)?

- Go deeper: Is there something I need or want that I am not getting, in this moment?

By recognizing the clues that your body gives you, you can prevent the loss of appetite regulation, hedonic eating, chronic overfeeding, and a rising set point. Not every pang of hunger needs to be treated with food. It’s okay to be hungry for a period of time each day. Tuning in to and discerning the messages you get from your body about hunger can help you shift to a place of balance between the left and right hemispheres, and develop a more peaceful and satisfying relationship with food, brain, body, and set point.

Step 2: Reset your hormones.

- Sleep more to reset leptin, ghrelin, insulin, and cortisol. If you have one night of bad sleep, you will temporarily worsen your insulin and prediabetes, so it’s even more important to eat pristinely that next day.114 Aim for seven to eight and a half hours per night.

- Add extra fiber to lower appetite, insulin, and glucose.

—Utilize a functional fiber containing water-soluble polysaccharides. This ingredient has been shown to reduce body weight, body fat, frequency of eating, and consumption of grains.115 It is a proprietary polysaccharide complex that has been shown in another randomized trial to lower body fat, insulin, and glucose within three months of daily use.116 Dose: 4.5-gram softgel orally before each meal, or 5 grams of PGX granules mixed with filtered water.

—Pectins are a type of dietary fiber made of gel-forming polysaccharides derived from the cell walls of plants, especially apples and citrus. They lower bad cholesterol (LDL and very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, VLDL-C) without affecting HDL,117 and can reduce other toxic loads as well. Pectins appear to reduce appetite, insulin, and post-meal glucose.118 Dose: 800 mg three times a day with meals. You can buy it at most supermarkets or online.

- Drink a glass of filtered water with apple cider vinegar to lower blood glucose and perhaps reset insulin.119 Add about one tablespoon to eight to twelve ounces of water daily, ideally before you eat.

- Increase your magnesium intake to raise adiponectin and lower inflammation, either from food (pumpkin seeds, leafy greens like spinach and kale) or by taking a supplement. Higher endogenous magnesium levels are associated with lower levels of inflammation.120 Even an increase of only 100 mg of magnesium per day lowers inflammatory markers.

- Limit or remove caffeine. Excess caffeine will raise your cortisol. Swap coffee for green or black tea, or even herbal tea if you’re highly sensitive.

- Stop snacking to repair leptin and insulin. Eat three meals a day and when you want to snack, have a glass of water and ask: Am I hungry, or angry, lonely, or tired? Eat every four to six hours on the days when you’re not fasting to help optimize insulin and leptin.

- Practice daily meditation or visualization for five to thirty minutes to normalize your cortisol and reduce inflammation. Consider that learning to surrender can help you heal your body and your brain. It may seem like it’s more passive, but it’s more about allowing the Divine to help you meet your goals.

- Drink more mineral water to decrease ghrelin and cravings.121

- Consider medication for your thyroid. Get your levels checked. You may need medication or a change in medication in order for your thyroid to work better in your brain and help lower your set point.

- Intermittent fasting lowers insulin in addition to your set point.

- Exercise wisely for a minimum of thirty minutes four times per week. Exercise improves your health in many ways, and has been shown to lower leptin, raise adiponectin, lower insulin, and burn fat in overweight and obese people.122 Moderate to vigorous exercise that includes burst training or high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is ideal. Burst training can be applied to cardio exercise (e.g., intermittently sprinting on a track alternating with a jog or walking) or weight lifting (lifting a weight, such as with a biceps curl, as many times as you can with good form for one minute, followed by one minute of rest). With my girlfriend Jo, I walk or run three minutes fast (approximately 6 or 7 on an exertion scale from 1 to 10), then alternate with three minutes at a normal pace (about a 3 on the exertion scale).123

Step 3: Deepen your detox from obesogens.

Here’s what’s proven to work, in addition to the strategies described in chapter 2. Pick one or more of the following strategies.

- Make a daily shake with hypoallergenic protein (such as pea or hemp protein), extra fiber, vegetables (or greens powder), and 1 teaspoon of spirulina. A 500 mg dose twice per day of spirulina (to the equivalent that’s in your daily shake) led to reduction of weight and appetite in obese individuals ages twenty to fifty years.124 Spirulina is anti-inflammatory and detoxifying.125

- Increase your daily dose of N-acetyl cysteine to 600 mg three times per day, or take liposomal glutathione to boost glutathione levels in your cells.

- Add prebiotic food to your meal plan, such as including a green banana in your smoothie. Prebiotics are indigestible carbohydrates—indigestible to humans, but they feed the good microbes in your gut, so they can grow, multiply, and protect you.

- Include probiotic food, as mentioned in Step 1. While some systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest there aren’t sufficient data to state that probiotics reduce weight,127 the probiotics that performed best for weight loss were Bifidobacterium lactis 420, Lactobacillus gasseri SBT 2055, Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103, and the combination of L. rhamnosus ATCC 53102 and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 to reduce adiposity, body weight, and weight gain. Overall, probiotics were associated with modest weight loss of up to three pounds, and performed better when combined with fiber.128 They may work by lowering appetite, resolving leaky gut, and improving inflammation.

BREATHE THROUGH YOUR LEFT NOSTRIL

I’ve written in previous books about the benefits of left nostril breathing to activate the right brain and help with sleep, but did you know left nostril breathing also helps restrain compulsive eating?126 Here’s how to do it.

- Sit in a chair or on a mat in easy cross-legged pose.

- Close your eyes and focus them on the space between the eyebrows.

- Use your right thumb to close your right nostril. Inhale deeply through your left nostril and hold at the top of your inhale for a few beats.

- Exhale through your left nostril and hold at the bottom of the exhale for a few beats.