CHAPTER 1 |

“Thank God for the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan”: |

As the Star of Bethlehem guided the wise men to Christ, so it is that the Klan is expected more and more to guide men to the right life under Christ’s banner.

—H. W. EVANS (1925)1

The real interpretation of the message of the angels who announced the birth of the Christ child . . . nearly two thousand years ago, was carried forth by the Klansmen and Klanswomen of the Altoona on the eve of Christmas day, and the lamp of happiness was lighted in more than fifty homes of the poor of the city and vicinity after the Ku Klux Santa Klaus had paid his visit to the said homes.

—IMPERIAL NIGHT-HAWK (1924)2

In his Modern Ku Klux Klan (1922), Henry Fry, a former klansman, described the ritual of naturalization, the process by which one became a member of the Invisible Empire. He observed:

The Exalted Cyclops raises a glass of water and “dedicates” the “alien,” setting him apart from the men of his daily association. . . . He is then caused to kneel upon his right knee, and a parody of the beautiful hymn, “Just as I am Without One Plea,” is sung by those of the elect who can carry a tune. . . . When the singing is concluded, the Exalted Cyclops advances to the candidate and after dedicating him further, pours water on his shoulder, his head, throws a few drops in the air, making his dedication “in body,” “in mind,” “in spirit,” and “in life.”3

Previously a Kleagle for the order, Fry could no longer continue his membership when he encountered the naturalization ceremony. The ritual’s resonance with Christian baptism proved unnerving to the author, especially since he considered the rest of the order’s rituals “tiresome and boring . . . twaddle.”4 That ceremony convinced Fry that the Klan was a “sacrilegious mockery.”5 What proved most disturbing to Fry was how the Klansmen seemed to have no problem with the naturalization’s proximity to the “sacred and holy rite of baptism.” Naturalization made a “mockery and parody” of a Christian ritual that the author held dear.6 For Fry, the ceremony confirmed that the Klan was a moneymaking scheme parading as a religious fraternity. Such blasphemy was more than he could handle. In a resignation letter to the order dated June 15, 1921, Fry listed his many complaints against the order:

In defiance of your threats of “dishonor, disgrace, and death” as contained in your ritual—written and copyrighted by yourself—I denounce your ritualistic work as an insult to all Christian people in America, as an attempt to hypocritically obtain your money from the public under the cloak of sanctimonious piety; and, I charge that the principal feature of your ceremony of “naturalization” into the “Invisible Empire” is a blasphemous and sacrilegious mockery of the holy rite of baptism, wherein for political and financial purposes, you have polluted with your infamous parody those things that Christians, regardless of creed or dogma, hold most sacred.7

The Klan, Fry contended, was not a Christian order but rather a false rendition of a religious movement. Furthermore, the suggestion of baptism in its naturalization ceremony proved the order was blasphemous as well. Hiding “under the cloak of sanctimonious piety” might have served well the order’s moneymaking schemes, but Fry denounced the so-called Christian beliefs that members professed. His book detailed the contradictions and dangers of the order, but nothing ruffled the author quite as much as the Klan’s professed Protestantism.

Fry was not the only skeptic of the order’s religious leanings. W. C. Witcher of Texas created a pamphlet exposing the hypocrisies and supposed scams of the Klan. Witcher opined that the Klan “seduc[ed] the preachers of this country into believing that they should encourage and support” the order and all of its actions. He also claimed that “to impress ministers with its sham benevolence . . . it adopted the old worn-out political trick of ‘donating to the preacher.’”8 The author suggested that the Klan would be rebuked rather than accepted by Jesus and that the Imperial Wizard, the leader of the Invisible Empire, was the “Ruler of Darkness.”9 To demonstrate the devious attempts of the Imperial Wizard to mold Jesus to the Klan’s message, Witcher provided a fictional account of a chance meeting between the two. Witcher described the Imperial Wizard as a manipulative figure who sought to overcome Jesus by wooing Him with worldly things. In the account, the robed leader emerged as the Devil, in the guise of a Klan leader. His desperate attempts to entice Jesus with power and prestige ultimately failed, and the parallels between Witcher’s tale and the biblical narrative of Satan’s temptation of Christ were quite deliberate. Jesus berated the Imperial Wizard for his blatant manipulation and cunning. The Klan leader, a “cringing coward,” “crumpled at His feet like a conquered beast before its master.” Jesus had won, and the Klan lost the support of its savior. The order’s deceptive commitment to the Christian tradition, at least for Witcher, became visible. He continued:

The echo of that rebuke rings down through the centuries like the voice of a nightingale, and if these commercialized ministers who have prostituted their pulpits with the white-robed children of the Imperial Wizard were even susceptible of a rebuke, they would drive these character assassins from their services with the whips of scorpions. Judas committed suicide for the same kind of offense. My God! How long wilt Thou suffer these miserable hypocrites to insult Thy Name, and defile Thy Sanctuary!10

Those vituperative statements affirmed the belief of both authors that the second revival of the Klan was not religious but heretical, devious, and dangerous. Witcher suggested that Klansmen who offered such false religion were no better than Judas, and he begged God to hold them accountable because of their defiance. He even advocated that members might want to imitate the suicide of Judas, since their actions were comparable to his. The author clearly found the Klan to be a significant threat to Christianity because of its declaration to be a Protestant Christian order. Both authors engaged the Klan’s professed Christianity and quickly dismissed the possibility that the Klan and its members could be legitimately religious. Ultimately, they disagreed with the Klan’s presentation of the Christian (Protestant) faith. They saw only “false” religion in the actions of the fraternity. In that way, their attacks highlighted how the Klan’s allegiance to Christianity caused unease among critics and former Klansmen. Those authors, in particular, were nervous about the order’s association with their personal faith tradition, and vitriol spewed forth. The order’s practiced faith proved too similar to the faith of its detractors. The resemblance required both authors to demarcate the religion of the Klan as foreign from their own religious commitments. The Klan, in its founding, bound Christianity with Americanism, and members professed allegiance to both despite their relentless critics. In the order’s white Protestant America, the order envisioned not only that members were the defenders of Protestant Christianity, but also that God had a direct hand in the creation of the order.

They built in their crude altar greater than they knew.

On the “bleak Thanksgiving night” of 1915, seventeen men climbed atop Stone Mountain, Georgia, with a purpose and a large wooden cross. They set the cross on fire, and under its light those “pilgrims” committed themselves to the U.S. Constitution, “American ideals and institutions,” and “the tenets of the Christian religion.”11 The men built an altar of granite boulders and spread the American flag over the rocks. William Simmons, the leader of the ceremony, wrote that “they built in their crude altar greater than they knew.”12 The eerie glow marked the beginning of the second Ku Klux Klan. The new order harkened back to the Reconstruction Klan, but its founder, Simmons, proclaimed a new path of militant Protestantism and sacred patriotism.13

Simmons, who became the Imperial Wizard of the order, and his successor, Hiram Wesley Evans, promoted a vision of the Klan as a patriotic, benevolent, and Christian order. For Simmons, that altar on Stone Mountain was the “foundation” of the Invisible Empire, which was committed to “the preservation of the white, Protestant race in America, and then, in the Providence of Almighty God, to form the foundation of the Invisible Empire of the white men of the Protestant faith the world over.”14 Evans noted, “As the Star of Bethlehem guided the wise men to Christ, so it is that the Klan is expected more and more to guide men to the right life under Christ’s banner.”15 The second incarnation of the Klan, therefore, was transformed and dressed in Christian virtue and metaphor. Protestantism served as the foundation of the movement, and the protection of its religious faith was a key component of the Klan’s mission. The nation, it seems, functioned better in the hands of the faithful. The religious foundation of the order, as we have seen, was not without its detractors.

Robert Moats Miller, writing in 1956, argued that the relationship between the Klan and Protestantism should not be assumed, nor asserted, since denominational newspapers as well as national conferences condemned the Klan.16 Miller utilized Christian journals to argue that Protestant churches were not bound to the order. National conventions and denominational governing bodies, for Miller, determined Protestantism. Yet local churches still proclaimed their affiliation to the Klan despite outcry from national bodies. Miller’s study lacked detailed analysis of how religion functioned for the order, enabling him to conclude that Klansmen and Klanswomen were not authentically Protestant. The Klan specifically defined that term to match the parameters of its organization.

Interpreting the role of religion in the life of Klan members demonstrates clearly how the order defined the terms “Protestant” and “Protestantism.” “Protestant” meant not only non-Catholic but also a recoded narration of Christian history. Questions still arise. How exactly did members and leaders define Protestantism? Were they evangelical, fundamentalist, both, or neither? Religious faith became crucial to the construction of the order by leaders, editors, and members. Protestantism undergirded the membership, the rituals, and the rites of the order, as well as imbued the pages of Klan print culture. My study of Klan print suggests a different conclusion than that reached by Miller: the Klan subscribed to Protestantism, and the order created their own definition, history, and vision of the faith for its members. That vision began with Simmons and flourished in the pages of the Imperial Night-Hawk, the Kourier Magazine, and other Klan papers. In the Klan’s creation of a textual community, Protestantism emerges not only as the foundation of the order’s structure but also as the larger nation.

In his writing and speeches, Simmons sought to create a super fraternity that not only appropriated the regalia and history of the previous Klan but also imported fresh symbology, which illuminated the importance of Americanism and Protestantism. As an ex-minister, Simmons combined faith with politics in his movement, and that faith washed over the pages of the Night-Hawk. Such might seem surprising to those who envisioned the Klan as a racist, anti-Semitic, anti-Catholic political organization, which it undeniably was. However, it was also an organization that required members to be Protestant Christians, who affirmed both Jesus as well as Americanism.

The Klan leadership crafted a religious organization, and the Imperial Night-Hawk (which became the Kourier Magazine), the Klan’s official organ, molded a public persona that glorified its faith. Through weekly publication, the Klan presented the ideals of its community and attempted to fashion Klansmen to reflect those ideals. The Night-Hawk and Kourier created a unified order through text. Being a good Protestant was key to being a good Klansman or Klanswoman. The Klan’s Protestantism was defined in a multitude of ways, from uplifting the literal meaning of the word (“to be a protestor”) to aligning the Klan as successors of the Reformation who “cleansed” the church and provided Protestantism as a foundation for both democracy and religious freedom. Klansmen were to be “protest-ants” of systems of iniquity, deriving their example from Martin Luther. Additionally, the Klan envisioned its role as the “handmaiden” of the church because of its ability to unite Protestantism in the face of denominationalism and supposed enemies.

Moreover, the Klan rendered Jesus in its organizational image. Members employed Jesus’ example as a model for their lives. In print culture, robes, and rituals, the order communicated its adherence to the Protestant faith and functioned to solidify the community in the face of threats to both faith and nation. It was a tenuous process to convince readers of the Night-Hawk to live the ideals and faith that the newsmagazines described.

The Reformation has taken residence in the Klan.17

According to Hiram Wesley Evans, the second Imperial Wizard of the Klan, “the angels that have anxiously watched the Reformation from its beginning must have hovered about Stone Mountain Thanks-giving night, 1915, and shouted Hosannas to the highest Heaven.”18 For Evans, the founding moment of the order was the second Reformation. Those joyous angels watched in awe as the order was born, and that event signaled that the church and society might be salvaged. Evans believed that the Klan had the potential to reform Christianity much in the same way that Martin Luther had “saved” the church within the first Reformation. The church was no longer able to lead such a movement because of fractious denominationalism, but the Klan, based on the Bible, with God and Jesus as its “soul,” could bring about “universal and rock-bottom reform.”19 The Klan crafted its own form of Protestantism, which highlighted dissent (protest), individualism, militancy, and a strong commitment to the works of Jesus.20

Despite joyous angels and divine support, Klan leadership and newspaper editors expended much ink to make their case for the Klan’s “protest-ant” heritage. Both the Night-Hawk and the Kourier contained lengthy articles about the Klan’s Protestantism, which served to establish the Klan’s place in Protestant history, to describe religious practice, and to demand Protestant behavior from Klansmen and Klanswomen. Imperial Wizard Evans even declared the 1925 Klan program was to promote Protestant Christianity. Evans beseeched the membership: “As the new year dawns, I, as Imperial Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, wish to call upon the Klansmen of America for whole-hearted, united, sacrificial service to the cause of Protestant Christianity. I ask you working through the several Protestant churches to which you belong, to make this a year of Christian devotion and high service.”21 The Klan both protested and proclaimed allegiance to Protestantism. Members sought, and often created, similarities between their movement and historical narratives of the faith. Klansmen hoped to place themselves directly in the lineage of both Jesus and Luther, as well as to define Protestantism in their own terms to reflect the purpose of their order.

A Protestant, in the most basic definition, is one who protests. For the editor of the Kourier, the protest could be directed at a person, event, or idea, and that protest was not confined to religious matters. The Kourier uplifted protest and dissent as important tools of both critique and change. Rather than limit the term to one who seceded from “the Roman Church,” he suggested that severance from Roman Catholicism was not required. Instead, protest was more generally linked to reform. Jesus was a “Protestant” who employed that method to correct the ills of his day. His life was “one of unending protest.”22 According to the Klan, he contradicted priests and asserted the need for individual conscience. Jesus’ ministry was “in open defiance to the religious monopoly that prevailed in Jerusalem.”23 He “believed” in free speech and the power of individuals to accomplish change. For the Klan, its use of Protestantism imitated Jesus’ behavior and beliefs. Protestantism, then, suggested fair play, freedom of religion, and a more generalized vision of freedom.

The editor of the Kourier described fair play as the promotion of equality, love, protection, and concession. Rather than oppose ideas contrary to the order, Klansmen should protect the ideals of others as well as support their individual freedoms. The editor wrote that “while we find the teachings of Jesus to have been very positive and pointed, we do not find Him ridiculing these other religious expressions, nor placing a ban upon . . . the aspiration of the soul.”24 Since Jesus did not ridicule opposing expressions (except those of the priestly class), the order required Klansmen to respect other religious traditions. Interestingly, the Klan lauded Jesus’ ridicule of “religious monopoly” in Jerusalem while still suggesting his tolerance for other religious beliefs. The Klan’s savior, accordingly, had no problem with individual beliefs, just authoritarian religious systems. Fair play easily extended into religious matters, and the Klan argued that its Protestantism also uplifted freedom of religion. For the Kourier, Klansmen should not judge the “spiritual aspirations” of men, because all people claimed the spiritual legitimacy of their own religions. How could one determine whether those aspirations were false? Protestantism, then, allowed for men to aspire to the spiritual and guaranteed that “all men have the right to the individual expression of that aspiration.”25 That reflected Protestantism’s commitment to individual rights, so individual liberty was embedded in this religious tradition.

The Klan’s religious faith, then, rested on freedom, which reached beyond the varying conceptions of religion and also applied to civil society. Its Protestantism contained a celebration of liberty, at individual and religious levels, which allowed for religious groups to practice their beliefs as long as they were not forcing those beliefs upon others. Freedom implied the independence from religious tyranny in America. The Ku Klux Klan, “being Protestant, is fighting the battle of every religious sect and every religious denomination” in its attempts to assert America’s freedom from religion as well as freedom of religion. For the order, the nation required protection from religious movements, which sought to inflict their traditions upon unwilling people. Such a notion of Protestantism demonstrated the Klan’s acute concern over non-Protestant religious movements and especially Catholicism. The editor noted that the Klan was a “friend” of Catholics. That friendship, however, was fragile because of the Klan’s fear that Catholics posed a threat to government and nation. The Kourier expounded, “Should Catholics seek to control this country to the exclusion of all other forms of religious expression, they will find the Klan fighting them until the last Klansman was [sic] dead.” In regard to the threat to government, Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, or others might also find themselves on the receiving end of the Klan’s wrath should they attempt to “usurp authority.” For the Klan, Protestantism might have suggested freedom, but it still retained its anti-Catholic tone and militaristic nature to respond to religious groups who overstepped their bounds in civic life. Inclusion meant limits. Despite the suggestion that Klansmen would risk life and limb in the pursuit of freedom, the Kourier pleaded with readers to “throw aside pre-conceived notions about Protestants and Protestantism, and dig down to the root meaning.”26 That “root meaning” relied on notions of protest and fair play while simultaneously promoting exclusion, particularly for Catholics. Such notions of Protestantism resounded as more secular than religious. Freedom applied not only to Protestantism but also had larger parlance in American culture. Dissent, individual conscience, and freedom of religion did not necessarily originate from the faith tradition. Rather, the Klan newspaper sought to broaden understandings of Protestantism as a religious tradition and for the order. The Klan expanded the umbrella of Protestantism, so that it might encompass ideas that avoided the particularities of denominations. The order generalized its Protestantism for mass appeal.

The Klan’s definition of Protestantism was not limited to a secular celebration of freedom. Protestantism did retain its spiritual aspirations. It was “the soul’s religious declaration of independence” as well as “a law in the spiritual realm.”27 The soul was free, but to be Protestant suggested one’s soul was truly unfettered. Jesus freed the soul from its fetters and reiterated the “spirit of religious law.” He affirmed the “spiritual interpretation of religion” rather than “literal adherence, [which] resolves itself into formal ceremonialism.” The spirit of the law negated the need for priests and ceremonialism. The Klan’s Jesus reveled in disobedience toward the high priests. He taught his followers to rely upon their own consciences for religious practice. He taught that people “should be free to worship God, their Heavenly Father, in the way best suited to their liberated conscience, and at any time in accord with their conviction.”28 That law manifested again in Luther’s reformation, which was a “re-formation” of Jesus’ teachings.

Luther rearticulated the vision of Jesus that had been “abandoned” by the church. Both men emphasized the importance of the individual over the collective and criticized the role of priests in religious experience. For the Klan, Luther sought to reinstate Christianity to its original and pure form. The Klan’s Jesus purported that salvation was in the hands of the individual, not through official ceremonies or formalism. Ceremonialism, however, was not the central focus of Luther’s attack. The Klan found a certain belief to be more disturbing. The Kourier reported:

The same belief exists today among millions of people who look to a human intermediary for their salvation more than they look to Almighty God. This is insidious priestcraft, and is tantamount to spiritual slavery. To break the people of His day from such enslavement, Jesus boldly declared: “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.” He also declared to the people if He made them free, they would be free indeed.

Such was a veiled attack on Roman Catholicism. Its supposed “spiritual slavery” revolved around the issue of the pope, “a human intermediary” who stood between Catholics and God. For the Klan, the centrality of the pope demonstrated the Catholic Church’s attempts to keep members bound in falsehood. The newspaper attacked the church because of its reliance on priests and the pope in spiritual affairs. Rather than criticize Catholicism outright, the article alluded to the similarities between ancient Judaism and the Roman Catholic Church.

Jesus’ critique of Jewish priests proved applicable to the contemporary moment because the criticism echoed the detriments of the church. For the Kourier, the church tricked Catholics into believing that obedience to the pope was necessary for salvation and that personal interpretation was unnecessary and wrong. The Kourier lauded the example of Jesus, “who freely encouraged people to think for themselves.”29 The Klan, however, was quick to point out, despite its denouncements of Catholicism, “Klansmen are not ‘against’ the Catholics . . . but are ‘for’ Protestant Christianity first, last and all the time.” Perhaps the Klan and its leaders were not aware of the contradictions in their position on Catholicism; yet the Klan degraded that Christian tradition in an attempt to assert the importance of Protestantism. In Klan thinking, the freedom of religion for Catholics was tenuous at best. An Exalted Cyclops proclaimed, “The Klan is here, and it will remain until the last son of a Protestant surrenders his manhood, and is content to see America, Catholized, mongrelized, and circumcised.”30

The vilification of Catholics was not unique to the order and had historical precedence in America. The Klan was embedded in a long lineage of American nativism and anti-Catholicism, which emerged in the colonial period and gained much ground in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Historian Peter D’Agostino pointed out that by the eighteenth century there was “no shortage” of anti-Catholicism in America. He argued that the founders of the American nation maintained anti-Catholic prejudice, but they did not need to react to individual Catholics since they were a minority population in the new nation. If they had, D’Agostino noted, “anti-Catholic fangs would have surely shown themselves more frequently.”31 The early colonists and founders perpetuated that bias against Catholics. By the nineteenth century, the residual bigotry burst forth in the American cultural scene in magazines, newspapers, books, and associations. Protestants documented their so-called encounters with Catholics as well as Catholicism in Europe and America, and Protestant writers, historians, and everyday folks crafted Catholics in their imaginations as exotic and dangerous. For Ray Allen Billington, nativism was “the first American mania of hostility to Catholics.”32 David Brion Davis argued that the “anti” movements, including anti-Catholicism, were movements for unity of the American nation, in that they were the fruit of fears about internal subversion and conspiracy.33

Anti-Catholicism emerged due to the mass immigration of Catholics in the mid-nineteenth century and the fear that Catholics could and would change the American nation.34 One consequence of that sentiment was the burning of an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1834. Anti-Catholicism was an imagined conspiracy. Catholics were the imagined enemies, but the consequences of those imaginings were very real.35 In the 1880s and 1890s, the American Protective Association (APA) feared Catholic conspiracies. They also helped fuel those fears by giving lectures to Protestant audiences, during which they suggested that Catholics were taking the jobs of Protestant workers. Thus, the APA actually played a role in two major anti-Catholic riots.36 Historian Mark Massa placed the second order of the Klan firmly in that lineage due to its use of “anti-Catholicism . . . as the most effective rallying cry.” For Massa, the Klan proved to be the last bold presentation of mainstream prejudice until the outbreak of World War II. The order was one of the main promoters of anti-Catholicism. At the 1928 Democratic convention, the Klan attacked Al Smith’s presidential candidacy because he was a Catholic seeking the nomination for the highest political office. Smith won the nomination, but lost the election. Massa argued that the shallow victory signaled the end of the Klan because Catholic prejudice largely dissipated in American public life.37

For Massa, the Klan maligned Catholics and adopted anti-Catholicism merely as a rallying cry. However, the order’s anti-Catholicism proved more sophisticated and illuminated the supposed alterity of the church. Its prejudice moved the order to refashion Christian history by excising Catholicism. To accomplish that goal, the Klan presented the Protestant Reformation not only as a movement to reform the church, but also as a movement that began with Jesus instead of Martin Luther. H. W. Evans argued, “the Reformation—started at the first altar that declared righteousness (right living)—has been, is and will ever be one cumulative urge toward Paradise Regained.” That first altar was the mission and ministry of Jesus. Evans proposed that the Reformation had occurred as the result of many reformers who had strove “toward the right.”38 By marking the beginning of the Reformation with Jesus and its continuing influence with Luther, John Calvin, John Wesley, and other Protestant reformers, the Imperial Wizard sought to eliminate the Catholic Church’s role in Christian history. His suggestion was that the Catholic Church’s “corruption” of Christianity neglected the “real” message of Jesus. Moreover, Evans claimed that God was the “soul—the life—of the Reformation.” God sanctioned and founded the reforming movements, and Jesus became the first reformer. Evans wrote, “Jesus therefore became the soul of the Reformation, and He will be its soul until it shall have accomplished its age-long task—that of restoring pristine relations between man and God, and between man and man; reproducing normalcy.”39

The Reformation, then, restored Christianity to its pure form. According to a Klan minister, Martin Luther demonstrated that salvation did not come through the church but rather through Jesus. Luther substituted Christ for the pope to reclaim the “true” message of Christianity. He “maintained that Roman Catholicism had forfeited its right to support by its betrayal of Jesus Christ as the head of a Christian, or so-called Christian, organization.” The minister continued, “Martin Luther blew up that doctrine [confession], and recrowned Jesus Christ as the great central object of our devotion and for our leadership in Christianity.”40 For the Klan minister, Roman Catholicism betrayed the mission of the Christian church, and Luther had corrected its errors. The Klan envisioned its members in the lineage of Jesus and Luther as the new reformers who would restore Christianity to its “originary” form. In retelling Christian history in a way that highlighted the importance of Protestantism, the Klan degraded the place of Catholicism. If God sanctioned the Reformation, then was the Catholic Church godless? If the Catholic Church “replaced” Jesus with the pope, were they really Christians? The Klan considered Roman Catholicism a failed attempt in Christianity. The Kourier noted that people were turning away from Catholicism because of its failure, and he wrote that the Klan’s duty was “to show them the more acceptable interpretation of Christianity as held by Protestants.”41

By minimizing Catholicism, the Klan strove to identify its own Protestantism. The Klan defined its Protestantism in opposition to “Catholics” as Protestants perceived them. That process of definition had historical precedent. In her work on Catholics in England in the seventeenth century, literary historian Frances Dolan argued that since Catholics were not easily distinguishable from Protestants, Protestants seeking to define Catholics as somehow different had to go to great lengths to make their case. For Dolan, the problem for Protestants was that they shared a common religious history and tradition with Catholics. To make their movement distinct, Protestants presented their own religious movement in oppositional terms. Protestants defined their Catholic brethren by what could have happened rather than what actually happened historically.42

The Klan participated in a similar process of differentiation. Whether or not the Klan was fundamentally opposed to Catholicism and Catholics was not always clear. The church, as an organization, served as a foil for all of the Klan’s concerns about religion and nation. Klan members’ relationships with flesh-and-blood Catholics proved more complicated. Their denunciations of the Roman Catholic hierarchy obscure how they related to Catholic neighbors (see chapter 6). Despite its vitriol, the Klan strove to portray liberating and tolerant perceptions of its faith. In presenting itself as a bastion of tolerance, the order made the Catholic Church the easy symbol of intolerance, backwardness, and authoritarianism. By showing the dangerous nature of the church, the order hoped to appear as more progressive and advanced. A Klan minister proclaimed: “Certainly Protestantism with its gospel of enlightenment, with its spirit of democracy, and with its idealism of the apostolic age of Christianity, has character, has righteousness, has purity of heart, has brotherhood, and certainly that type of Protestantism is at least two or three hundred feet higher than the darkness and the superstition and the rottenness and the tyranny of Roman Catholicism.”43

Klan conceptions of Protestantism contained values like religious freedom and individualism while simultaneously drawing boundaries of exclusion. Catholicism became the representative of all the “rottenness” that Protestantism was not. Catholics and Catholicism became the foils to the “virtues” of the reforming spirit of the Klan. The order’s anxieties about the church reflected more its unease with changing social norms than with actual Catholic actions or presence.44 The negative portrayal of Catholics bolstered the Klan’s Protestantism. The order also claimed its status as the promoter of the “true” form of Christianity. To present further its Protestantism, the Klan crafted Jesus as a savior, an exemplar for character and behavior, and as a likely member of its order. In presenting Christ, the Klan continued to use the church as a foil for the order’s dedication to correct principles and, most important, correct belief.

Jesus was a Klansman.45

In the opening prayer of Klan rituals, the order proclaimed that “the living Christ is a Klansman’s criterion of character.” A Texas Klansman and minister, W. C. Wright pondered what those “magical, significant words” meant for the life of a Klansman. Wright wrote, “We desire to call attention to some of the outstanding characteristics of His life, as they pertain to the fundamental principles of Klankraft and the development of a real, dependable character.” Jesus had an exemplary character, and the author believed that his experiences could relate to the experience of the ordinary Klansman. In the Night-Hawk, Wright pointed out that by knowing the character of Jesus, Klansmen could emulate his behaviors and principles for the betterment of themselves and for the good of the order. After all, “Jesus was a Klansman . . . a member of the oldest Klan in existence—the Jewish theocracy.”46 While the focus on Jesus’ Jewishness might seem strange in that context, the Klansmen asserted that Jesus promoted Jewish supremacy much like the Klan supported white supremacy. The Jews, then, were just as concerned with maintaining racial purity as the Klan was. Jews “have been Klannish since the days of Abraham; and Jesus was a Jewish Klansman . . . by birth, blood, religion[,] . . . teaching and practice as well.” Jesus was important as a savior and as a member of the Jewish clan. His “allegiance” to that clan resonated with Klan members. Additionally, Jesus “sought, first of all, to deliver the people of his own race, blood, and religion.”47 Interestingly, the order did not reflect upon Jesus’ Jewishness; the savior, it seems, lost more of his ethnic identification the longer he was a Klansman. His ethnicity did not matter, only his membership in a clan. Instead, the Klan’s Jesus reflected the values of the order. To bolster such, the Klan crafted the story of Jesus’ life to fit its paradigm. The order engaged his example quite seriously.

By harkening back to Jesus’ life, the Klan related his trials and triumphs to those of the order and its members. The Klan’s Jesus overcame adversity, and he emerged from the Jewish clan to create his own clan, Christianity. After the resurrection, Jesus expanded beyond his previous “clan” and proclaimed a plan for salvation based on moral character rather than kinship ties. The trademarks of Jesus’ followers were “spiritual, namely, a chivalric head, a compassionate heart, a prudent tongue and a courageous will, all dedicated and devoted to the sacred and sublime principles for which He had paid the supreme sacrifice.” All of those were expected traits of 1920s Klan members. A Texas Klansman opined, “May every Klansman develop just such a character as He exemplified when He walked among men.”48 If members would follow the path of Jesus, their lives and their practice of “Klankraft” would benefit from his guidance.49 That religion became “the Klan of Character” founded by Christ. Wright suggested that not only was Jesus part of a Jewish clan but also that Christianity was an extension of that previous clan. The 1920s Klan, then, “mimicked” the Christian clan. Wright attempted to renarrate early Christian history so that it reflected the structure of the order. To say that Jesus was a Klansman provided the order with religious legitimacy for its cause, and thus the order claimed Jesus as the role model for Klansmen’s behavior.

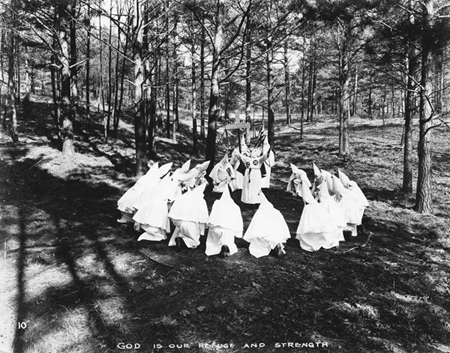

God Is Our Refuge and Strength. Georgia Klansmen kneel in prayer accompanied by the cross and flag. The 1920s order recruited ministers as members, leaders, and lecturers, and the Klan affirmed its Protestantism in prayer, creed, print, and robes. Courtesy of University of Georgia Hargrett Library, Athens.

The Klan’s Jesus, then, was selfless, humble, meek, patient, and charitable, and he sacrificed himself for others. Thus, his actions inspired the Klan’s motto, “Non Silba sed Anthar, not for self but for others.”50 Jesus’ selfless nature inspired the Klan to be selfless. Members hoped that their actions would help others as well as strengthen the bonds of their community. Klansmen were to “be knit together as the members of our body, each co-operating with the other; so closely and vitally connected that when one member suffers the whole body suffers.”51 Wright employed Ephesians 4:16 for his rendering of Klan service, though his focus on suffering was absent from the biblical verse. Selflessness as a Klan virtue required a Klansman to discard his selfish impulses and deny glory for himself. Selflessness, then, led to equality. That corollary virtue urged Klansmen to be merciful and just to other members. The Night-Hawk declared, “Be hospitable to your fellow Klansmen, he is one of many who are many in one, devoted to a common pledge and pledged to a common cause.”52 As a part of the collective, the community, that common cause trumped individual turmoil. There were many in one body, and in practical terms selflessness afforded a way to circumvent the competing personalities of Klansmen. Selflessness emphasized the importance of cohesiveness in the order over an individual’s desires and wants. It placed the order first and the members a distant second. In the printed pages, the uplifting of Jesus’ example and the extolling of selflessness also illuminated members’ charitable acts. Klansmen delivered baskets of food to the poor on Christmas, donated money to Protestant benevolent associations, and even created their own charitable institutions. In Altoona, Pennsylvania, the local Klan played Santa to poor children. For the Altoona Klan, “the real interpretation of the message of the angels who announced the birth of the Christ child . . . nearly two thousand years ago, was carried forth by the Klansmen and Klanswomen of the Altoona on the eve of Christmas day, and the lamp of happiness was lighted in more than fifty homes of the poor of the city and vicinity after the Ku Klux Santa Klaus had paid his visit to the said homes.”53

The Night-Hawk reported that through such acts the Klan lived the “real interpretation” of Jesus’ message. In Lisbon, Ohio, the Women of the Ku Klux Klan donated baskets to the poor with “a gift for each child.” Christmas was not the only time in which the Klan exercised its charitable spirit. In Dallas, Texas, the Klan provided an $85,000 building as an orphanage for infants entitled “Hope Cottage.” The Corpus Christi Klan started a Protestant memorial hospital in honor of a slain Klansman. The local klavern affirmed that a Protestant hospital was a much-needed addition to the town in which “the Roman hierarchy was in control.” It was a memorial as well as proclamation of the faith. In Shreveport, Louisiana, the local Klan collected funds to start a “Protestant Home for girls,” because in Louisiana the only homes for girls were Roman Catholic. That need came to the attention of the larger Klan organization when a young minister joined the Klan and hoped to “actively practice Klancraft.” He revealed that a mother was prostituting her two young daughters and had the woman arrested. Discovering that there was only a Catholic home for girls, the distraught Shreveport Klan launched a fund-raising campaign for a Protestant home. That Klan hoped to build the home and provide it “to the State with the one proviso that it be conducted by Protestants and on Protestant principles.”54

Additionally, the Night-Hawk established a fund for the widow and two children of Thomas R. Abbott, a murdered Klansman, so that his children could attain an education. The Night-Hawk encouraged Klansmen throughout the Invisible Empire to contribute money for the Abbott family. A Pennsylvania Klan even donated money to the building fund for a “Negro Church,” as well as an ample number of Bibles. The Klan’s benevolence could occasionally breach racial lines, but its charitable donations did not cross religious boundaries. Many local Klans, as demonstrated above, strove to uphold their pledge to selfless service. Imperial Wizard Evans affirmed that “Klanism is altruistic or it’s nothing. Every benefit we seek not to monopolize, but to diffuse throughout our citizenship and to place, so far as may be, at the service of mankind.”55 In 1924 the national Klan instituted a charitable program. At the annual Klonvokation, Evans proclaimed, “It shall be the program of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (a program in line with the divine plan) that ten percent of all the monies that come to your National Organization shall be . . . applied to humanitarian service.”56 The Imperial Wizard also encouraged individuals to give 10 percent of their personal incomes to help those in need. The order constructed a tithe to aid others, but aid contained requirements. White Protestant organizations generally received such funds, and the Night-Hawk reminded Klansmen to review their donations to ensure that their “tithe” supported primarily Protestant organizations.57

Selfless service was only one component of Jesus’ example. The Night-Hawk rendered their savior as a fighter. In print, Jesus was the “Master Christian, who stood unflinchingly for the cause that He knew to be right.” The Master Christian “feared no man . . . never wavered, and . . . left to all mankind a heritage that you [a Klansman] may have for the asking.” Each Klansman should take “stock of their mental and physical selves” in comparison with Christ. The Night-Hawk maintained that “the Pilot Imperial, Christ Jesus, whose teaching all Klansmen follow, believed in something better yet to come and threw himself into the cause of the future. He, alone, changed the universe. Klansmen . . . do reverence to Him, catch the Master’s spirit.”58

Klansmen embraced Christ’s example. Christ’s disciples were to be “fishers of men, who made their nets therefore of words and example to establish a principle of citizenship and duty and service to mankind.” By following the example of the disciples, Klansmen could missionize more men for the Klan. Klansmen “engaged in the championing of principles of the organization co-operating as a solidified body of Christian Americans of one mind, of one purpose and one common understanding.”59 In that spiritual warfare, Klan members sought to convert others to the faith, through their personal examples. If the individual Klansman embodied Christ’s spirit, in word, deed, and action, then he could be a “fisher of men” and bring more into the fold. He would spread the “holy principles of righteousness and truth” by following Christ.60 The Night-Hawk urged Klansmen to do as Christ would have done, so the organization and the nation could benefit. Members’ actions should reflect the Klan’s teachings, and Klansmen’s bodies, by conforming to the printed guidelines in the Night-Hawk, were to witness the Klan’s Protestant core. Since each member represented the order, conformity was also a Protestant value.

Moreover, Jesus’ crucifixion, as personal sacrifice, was also important for Klansmen because it demonstrated the lengths one man would go to for others. Members of the order were encouraged to remember Jesus’ redeeming act. The cross, albeit a fiery cross, was an emblem of the Klan, which the order upheld because “the Cross . . . bore the Redeemer of the world, . . . the only begotten [son] of the Father.” The light of the cross was a memorial to the model for Klansmen. An Indianapolis Klansman described the crucifixion and its significance in gruesome detail:

Out from Pilate’s hall, Jesus staggered down the steps to the narrow road that led to Calvary, and there under the burden of that rugged tree His physical strength failed. He fainted beneath its load—the blood clotting in His hair, the perspiration drying upon His face. He came out of the faint only to proceed to Golgotha, and there the cruel nails pierced through His hands and feet. The Cross was lifted and dropped with a thud into the earth, and upon it Jesus Christ gave Himself as a ransom for many.61

This Klansman hoped to remind his fellow members that Christ died for their sins. Members should follow Christ’s path of righteousness and goodness. Jesus set the example for both service and sacrifice. Klankraft required a “living sacrifice,” and Klansmen’s bodies were to be living sacrifices for God’s will. A column entitled “Christian Citizenship: The Gospel according to the Klan” reflected upon a verse from Romans 12: “I beseech you, therefore, brethren by the mercies of God, that you present your bodies a living sacrifice unto God.” The Night-Hawk advised Klansmen to “present your bodies, a living sacrifice. If you are going to perform the reasonable service God demands you are going to use your body.” Since Jesus’ wounded body bore the sins of the world, a Klansman should offer his body in service of God through the Klan. A member should follow Jesus’ example to a lesser degree by bearing witness to his path (as crafted by the Klan). It was not necessary to sacrifice one’s life, but to sacrifice one’s selfhood for the greater body of Klan membership.

The bodies of Klansmen bore the weight of Jesus’ principles. The Night-Hawk advocated prayer but also “sacrifice on the altar, not only on Sunday and weekly prayer night, but week days and election days.”62 That living sacrifice was the “supreme test.” A Klan minister wrote, “Man thinks more of his own body than anything else he possesses. He will gladly give up honor, glory, reputation, character, friends, wealth, and even his own soul, to save his body.” For the minister, the body was of utmost concern. He continued, “To lay our ‘bodies,’ yet living on the altar of service, is a supreme sacrifice. . . . This demands a clean, consecrated life. God will not accept an unholy offering.”63 Ideally, all Klansmen’s actions should reflect Jesus’ sacrifice, from charitable giving to political action to personal behavior. As a Klansman, life was no longer simply about one’s self but also about the lives of others, as well as the reputation of the order. Through focusing on living sacrifice, the Klan required its members to follow the order’s doctrines. Its rendering of Jesus was the archetype for behavior. To enforce the example of Jesus for Klansmen, the white robe, the uniform, contained a theology of its own. Wrapped in white robes, Klansmen presented their bodies for service.

Candidates for initiation into the Klan stand in front of an electric Fiery Cross, 1923. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

Indiana Klansmen create a “cross” formation. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

The white robe which is the righteousness of Christ.

In the late 1860s, the Reconstruction Klan created the distinctive Klan uniform, which consisted of long white robes decorated with various occult symbols. Tall conical hats completed the outfit, and white fabric covered the individual’s face with two openings for the eyes. The design supposedly imitated the ghosts of the Confederate dead.64 The revival of the Klan in the 1920s appropriated the uniform, but its meaning changed. William Simmons, the founder, admitted that the initial purpose “in adopting the white robes . . . was to keep in grateful remembrance the intrepid men who preserved Anglo-Saxon supremacy in the South during the perilous period of Reconstruction.”65 However, the uniform proved more than a memorial. Simmons wrote: “Every line, every angle, every emblem spells out to a Klansman his duty, his honor, responsibility and obligation to his fellow men and to civilization. . . . All of it was woven into the white robes of the Ku Klux Klan for the purpose of teaching by symbolism the very best things in our national life.”66

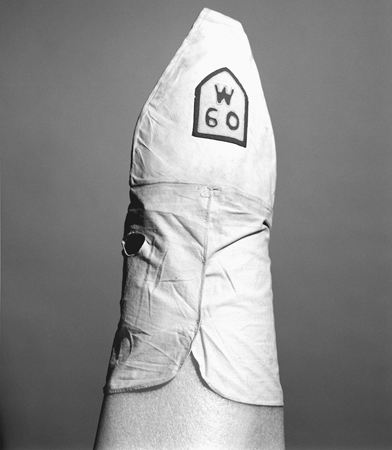

1920s Klan robe. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana.

No longer were the robes merely a ghoulish disguise. Rather, the clothing embodied a sacred meaning for Klansmen. According to Simmons, the new role of the costume was consistent with the symbolic function of robes in other religious and fraternal organizations. Moreover, Simmons asked, “Why should we the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, be singled out and condemned for adopting a symbolism . . . to represent our particular service to the age in which we live?”67 The uniforms mapped patriotism, chivalry, and, most important, white Protestant Christianity on the wearer’s bodies. The sacred folds of the uniform reflected the order’s white supremacist notion of Christian virtue. The costume displayed the ideology and identity of the Klan.

Detail of the 1920s Klan robe. The Klan emblem on the robes appears prominently, showcasing the white cross surrounded by a red circle. Inside the cross, a tiny blood drip signifies the blood Christ shed to save humanity. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana.

The robes were the material presentations of the Klan’s commitment to Protestantism and white supremacy. By 1923 Klansmen and Klanswomen manufactured the robes in a Klan plant to guarantee homogeneity of the robes and to control how the product was made.68 Since the robes had immense symbolic value for the Klansmen, the regalia factory controlled the manufacture of material artifacts, much like the Night-Hawk strove to monitor the image of the order. Despite its symbolic import, the uniform was quite simple. The average Klansman’s uniform consisted of a belted white robe with cross insignia and a white hat with an apron, or mask, that covered one’s face. The loose robes disguised the wearer’s body, and the mask made one’s face unrecognizable. The color white represented purity, racial and spiritual, as well as re-presented “whiteness” of the men “masked” by their uniforms (see chapter 5). The color of the robes displayed the requirements for membership: Caucasian, Protestant, and “native-born” American, all of which equaled whiteness.69

The cross insignia was a white cross in a circular field of red. In the middle of the white cross was a single red symbol that appeared to be a comma. The comma was actually a drop of blood that represented the blood that Christ shed for all humanity. The cross, then, harkened back to the Klan’s Christianity and was a reminder of Christ’s debt for human sin as well as his example of merit-filled action. According to the Night-Hawk, Protestant forces in the Middle Ages carried the cross “in their perilous efforts to rescue the Holy Land from heathen Turks,” so it became a sign that the Klan, embodying Protestant Christianity, could conquer the “hordes of the anti-Christ” as well as the “enemies” of Americanism.70 The robes functioned to represent the Klansman’s spiritual purity and his commitment to Jesus.

A Klansman, then, could wear Christ’s example, symbolized in the uniform, on his body. The white robes and the mask emerged as symbols of Christ’s righteousness. The Night-Hawk noted that the robe was a “symbol of the robe of righteousness to be worn by saints in the land of Yet-to-Come.” With Christ as their example, the robe was a sign that Klansmen were endeavoring to follow his teachings. A Klansman wore “this white robe to signify the desire to put on that white robe which is the righteousness of Christ, in that Empire Invisible, that lies out beyond the vale of death.” Some “scoundrel” could attempt to wear the “sacred folds of the robe,” but his soul was not a Klansman’s soul. The robe functioned both as a purifying agent and a reminder of the sinless perfection of Jesus as compared to the imperfect lives of the Klansmen. That material feature was the method for Klansmen “to cover here our filthy rags and imperfect lives with the robe,” and members hoped “through the Grace of God and by following His Christ, [to] be able to hide the scars and stains of sin with the righteousness of Christ when we stand before His Great White Throne.”71 The robe cleansed their sinful impurities while uplifting the purity of Jesus.

Klansmen in Elwood, Indiana, 1922. Klansmen, both masked and unmasked, in the standard white robes with cross insignia. Klan leadership emphasized the need to keep one’s apron (hood) down for protection of individual identity and the larger order. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

The white-robed Klansmen also mimicked the white-robed figures in the Book of Revelation. A Colorado minister claimed that the white garments of the order echoed the characters in the biblical text. For the minister, Protestantism had “been groping back to that memorial room where those twelve men sat for the last time with their immortal Leader.”72 By examining Revelation, he applied the text and its prophecy to the current age. He noted a decline of Protestantism, but he conjured the image of the white-clad men who appeared before the throne of Jesus. Their robes were “washed” and “made . . . white in the blood of the Lamb.” By wearing those robes, the men dedicated themselves to the worship of God and his service. The minister then noted the parallel between biblical narrative and the contemporary age: “I wonder if God did not notice the plight of His children . . . [and] He raised up a new order wherein all Protestantism could . . . promulgate the teachings of the Man of Galilee.”73 The men in the white robes not only represented Christ’s example through their uniforms but also became reflections of the biblical narrative. For the minister, the Klan served to promulgate the teachings of Christ.

According to Rev. James Hardin Smith, Jesus would have worn the robes if he had had the opportunity. He proclaimed, “I think Jesus would have worn a robe such as they [the Klan] use, but because He did not wear a robe a mob came and took Him and crucified Him.” Smith believed Jesus would have used the disguise to protect himself on missions of charity, much like the Klan employed the garments. Klansmen might have embodied the message of Jesus while wearing the uniform, but Hardin suggested that Jesus might have implemented the uniform as a tool for his own ministry. He continued, “I am not sure that Jesus would bid men to take off their robes.”74 In the Klan’s rendering, Jesus was both exemplar of action and practical supporter of its disguise. Those garments were both sacred and practical: to uplift the Protestant message of the order and to mask the individual members of the order. According to Smith, Jesus would have supported both.

Through the sacred folds, Klansmen commemorated and lived the sacrifice of the “Master Christian,” Jesus. Their robed bodies expressed the beliefs of the Klan.75 The “hated mask” concealed the faces of members, making them part of a faceless, white-robed collective. The mask wiped away the last traces of the individual, which allowed a Klansman to become part of the larger body of the Klan. The Night-Hawk claimed that the masks functioned in two ways: as protection of the secrecy of the membership and as a symbol of the unselfish nature of membership. A Texas Klan leader wrote, “With the mask we hide our individuality and sink ourselves into the great sea of Klankraft. . . . Therefore we hide self behind the mask [so] that we may be unselfish in our service.” The individual Klansman sacrificed a sense of self to be a member. The mask eliminated distinguishing features, equalizing members and subsuming them into a collective. The Texan continued:

1920s Klan hood/mask. Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Who can look upon a multitude of white robed Klansmen without thinking of the equality and unselfishness of that throng of white robed saints in the Glory Land? May the God in Heaven, Who looks not upon outward appearance, but upon the heart, find every Klansman worthy of the robe and mask that he wears. Then when we “do the things we teach” and “live the lives we preach,” the title of Klansman will be the most honorable title among men.76

For the Klan, the indistinguishable multitude presented its ideal of selflessness. The outward appearance reflected the collective. The Texas Klansman urged members to live by the Klan’s teachings because the action of an individual could make the Klan more honorable or more loathsome.

Thus, the microcosm, the individual Klansman, was the symbol for all outsiders of the macrocosm, the Klan. Each Klansman represented the larger belief structure of the order, and the order struggled to control actions and beliefs of members. Imperial Wizard Evans issued an official position on the misuse of regalia, which warned that unofficial use of regalia was “a direct violation of the rules of this Order and must be discontinued.” The Night-Hawk reminded readers that “untold damage might easily result from such practices.”77 The employ of regalia required regulation to maintain the ideals of the order and its public appearance. Moreover, Evans instructed Klansmen to keep their visors (part of their masks) down. Secrecy allowed a member to perform at his best as a Klansman. If a Klansman’s identity was revealed by the careless act of lifting one’s visor, he placed himself and his fellow Klansmen in danger. The enemies of the Klan could utilize that information to exploit members. Once a Klansman’s identity was known, the enemy could easily discover who other Klansmen were by association. The Night-Hawk warned: “To expose your identity as a Klansman lessens your ability to perform constructive work for your country and your community. To divulge the membership of a fellow Klansman is nothing but the basest treason and under Klan law is punishable as such.”78

The apparent anxiety in the print culture illuminated the organization’s desire to control its message. That desire included monitoring the boundaries of textual and embodied community. Members mirrored the collective’s ideals, and obviously there was room for human error. While wearing the sacred folds, one Klansman’s actions could put the order’s larger message of Protestantism in peril. The Klan crafted its own Protestantism, but individual members did not necessarily follow the dictates of the order. The white robes articulated the religious vision as well as the practical need for disguise, but that could not guarantee that Klansmen practiced in the method that the Klan preached. The order emphasized more than one’s personal religious faith, commitment to Jesus, and collective Protestantism. The Klan hoped to unite Protestantism by moving past schisms within the faith and bringing Protestants together under one undivided banner of faith.

Thank God for the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.79

According to the Imperial Night-Hawk, the Klan at its core was a “great American Protestant order.”80 To be eligible for membership, “one must have been born in the United States, of white parentage, be over 18 years of age and of the Protestant Christian faith.” As we have seen, faith was a defining feature of membership beyond eligibility requirements. The order proposed that scripture was the basis of its principles, and Jesus was the criterion of character. The Bible was “the keystone of Klan principles.” Moreover, the stated intent of the Klan was to be an auxiliary for Protestant churches. The goal of that auxiliary was to make Protestantism a more powerful force. A Louisiana Klansman remarked that one of the chief aims of the Klan was “to bring the different branches of the Protestant church into a closer relationship with one another as well as to preserve the United States as a Protestant Christian nation.”81 The Klan hoped to unite the forces of Protestantism by moving past the strictures of denominationalism. To accomplish that task, the Klan sought to make members more devoted to their personal Protestantism.

The Night-Hawk proclaimed that “one of the foremost duties of a Klansman [was] to worship God.”82 Klansmen should be religious and dedicated to their churches. “Every Klansman should have a Bible in his home[,] and he and his family should read it.”83 Ideally, membership in the Klan would improve the member’s interaction with his church, his family, and his country—for “no man can be a good Klansman and not be a better citizen and a more consistent Christian by the experience.” The Klan transformed men into inspired members who were good, churchgoing citizens.84 A leader from Texas noted, “Klansmen are taught that they become much better Klansmen if they attend divine services regularly with their wives and families and support the Sunday Schools of their city.”85 An anonymous author asked, “How can any man presume to call himself a one hundred per cent Protestant if he does not give one hundred per cent support to Protestant churches?”86 Good Klansmen became better men because of their devotion. Their worship made them familiar with some form of Protestantism and therefore, one hoped, more willing to campaign for a united faith.

Above all, Klansmen were expected not to be “Weak Kneed Protestants” who did not stand up for their beliefs. Rather, they were to embrace the Klan’s version of Christianity as wholeheartedly as they embraced their Klan membership. According to the Dawn, a Klan newspaper from Chicago, real men “have long decided that sitting on the fence is not the place for a native born, white, Protestant gentile, who would save America from her enemies.” The “man on the fence” should feel uncomfortable about his uncertainty about the order and its faith. Moreover, the Dawn proclaimed, “If you are on the fence get off today. Don’t be like Mr. Weak Kneed Protestant.”87 The Night-Hawk also knowingly suggested that “the Klan is founded on the word of God: you’re not ashamed of that are you?”88 Both papers reverberated with defensive tones suggesting that white Protestant American men were not “real men” unless they belonged to the Klan.89 According to contributors to both papers, Klansmen were strong Protestants as opposed to the other weaker Protestants. The Klan’s logic proceeded that if Protestant men were not ashamed of God and knew the Klan’s Protestantism, then they should join. The Klan’s print culture contained a rhetorical style that goaded Protestant men into membership and shamed Klansmen into going to church. Individual Klansmen should have been defenders of the Klan’s values, and the print culture served as a reminder of acceptable klannish behavior. The overemphasis on “true” religious behavior arouses suspicion about whether the Klansmen’s behaviors were sullying the ideals of the order. After all, one author warned, “God hates nothing worse than cowardice in His cause.”90 Individual Klansmen were to be God-fearing men or face ridicule in print.

In addition to the demand for members to be “one hundred percent Christians,” the Night-Hawk affirmed that Christianity was foundational to the structure of the organization. The twelfth chapter of Romans was the “Klansman’s law of life,” an example of how to live a Christian and klannish life. After reflecting on Romans 12, “the fundamental teachings of Christ,” the Night-Hawk stated, “Klansmen should be so transformed, or different from the world, that [their] lives prove what is the will of God.”91 The Klan changed men, so that they were “new creatures” who were modest, active, never slothful, selfless, virtuous, persecuted, honorable, and just.92 Klansmen became models of the will of God. A minister-defender of the Klan prayed, “May God help us, and Christ strengthen us to walk daily by the sublime law of the Divine will, that we, as Klansmen, may prove to our enemies, ‘what is good, and acceptable, and perfect will of God.’”93 Individual men were not only Klansmen but also moral exemplars for their faith. The order dictated the personal life of a Klansman, so the best, albeit masked, face could be put forward. Through print, the Klan strove to create God-fearing, white-robed men who, under the banner of faith, had the potential to unite the fragmented religious tradition.

Through those actions, the Klan endeavored not only to create religious Klansmen but also to bind together disparate Protestant groups. The Night-Hawk remarked that since the order was “composed of no one creed of the Protestant faith,” Klan meetings furnished an arena for “many . . . branches of the Protestant Church [to] rub elbows at its meetings, form lasting friendships . . . as they work in a common and holy cause.” A leader in the Texas realm of the Klan claimed, “A forward stride has been made for a United Protestantism which will pre sent a solid front to those who would engender ill feeling among Protestants.”94 The Texan believed that the Klan allowed for a united faith, which enmeshed Protestant groups into a larger collective. The Night-Hawk hoped that the order would unite both the divided country and the divided faith. Due to the Civil War, Protestants tore the “Body of Christ by maintaining Northern and Southern convocations of their same sect.” The weekly envisioned the Klan as the force to mend divisions of the country as well as among denominations. The Night-Hawk noted, “The Klan platform is broad enough to accommodate all Protestant faiths and strong enough to sustain their combined weight.” The order sought to provide a program that emphasized the similarities rather than doctrinal differences of denominations. The program was the “united effort of Protestant patriots,” who supported “one Lord [Jesus], one Faith, one Baptism.”95 The attempt to mend divisions rather than create new ones was an essential goal of the Klan. Unification did not mean that the Klan was attempting to be a church. For Rev. W. C. Wright, the Klan aided churches but was not a church in its own right. Instead, the Klan was a “Protestant Clearing House,” which served all Protestant churches instead of affiliating with one denomination over another. Wright continued: “We cannot ‘take sides’ in religious controversies, and unprofitable wrangles; but we must strive to exalt the living christ as ‘A Klansman’s criterion of character,’ and stress the twelfth chapter of Romans as ‘A Klansman’s Law of Life,’ by constantly exemplifying these ideals in our daily conduct.”

The Klan claimed to join “the forces of a divided Protestantism.”96 By providing an arena for Protestants to gather solely as Protestants, the Klan hoped to combat not only schisms but also enemies of Protestantism. One Klan minister suggested Martin Luther was actually responsible for the divisions. He argued, “Luther failed to secure permanent union in his own ranks.” That lack of stability led to the fracturing of Protestantism. Moreover, the Roman Catholic Church had taken advantage of the divisions. Catholics were “banking on its destruction of this great Protestant organization [the Klan] that at last has arisen, under the glory of God.”97 The Klan felt that Catholics feared and criticized the order because of its efforts to mend the fragmented Protestantism. United Protestantism had the potential to save not only the faith but also the nation for Klansmen. The Klan’s efforts at unity, however, were not appealing to all Protestants.

The religious and patriotic order strove to be an auxiliary for churches, yet some Protestant churches felt threatened by the order’s reemergence. The order was also anxious about its relationship with churches, and that anxiety was well founded because of criticisms printed in the Christian press. The Christian Century, Christian Work, Christian Herald, and many local papers, like the New York Christian Advocate and the Arkansas Methodist, printed derogatory columns and opinions on the Klan, ranging from critiques of secrecy to claims of un-Americanism and un-Christian behavior.98 A contributor to the Northwestern Christian Advocate claimed any minister who supported or failed to criticize the secret organization “that plots its deeds in secret and executes its purpose cruelly and under mask was not worthy to preach the gospel of an open-minded and clear-breasted Christ.”99 For those religious presses, the Klan did not illustrate its religious legitimacy.

To counter the printed attacks, the Imperial Night-Hawk highlighted the aid the Klan supplied churches. The weekly reported, “where the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan are active, Protestant church attendance has shown notable increase and church work generally has taken on renewed vigor.”100 The contributors purported confusion at denunciations of another arena for Protestants to come together. One author wrote, “But if members of Protestant churches feel disposed to band together, merely for fellowship or for some more specific purpose, who is to deny them that privilege?” He continued, “Would hundreds of Protestant ministers retain their membership in an organization that is such a menace to Protestantism as is claimed?” After all, the author stoutly believed that the Klan “compare[d] favorably with that of any church in intelligence, morals, good citizenship, and even in Christianity itself.” The order did not imagine itself as a threat to Protestantism. Rather, the Night-Hawk and its contributors argued that the organization was the opposite, a “secret society” that “advanced Christianity.”101 The tension was apparent between what the Klansmen thought their order did for their faith and the ways others perceived their actions. In the pages of the official organ, Protestant ministers defended the Klan and its good works for Protestantism. Rev. H. R. Gebhart of Indiana proclaimed, “God is surely with the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.” For the minister, the Klan was strengthening, not weakening, the faith. He opined, “I can see the hand of God more and more in this Klan movement. . . . The Protestant churches have lacked unity, but through this wonderful movement they are becoming united in a common cause. All I can say is: Thank God for the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.”102 The Klan propagation of that world-view through its print culture proved members’ participation in the “protesting” faith. After all, Gebhart believed that the churches should have been thanking God for the Klan’s involvement in their cause.

The fashioning of a religious identity, the identity of the collective, was clearly undertaken in the pages of the Night-Hawk, which stressed, repeatedly, the Klan’s worldview. The editor(s), the shock troops, seemed to paint the importance of Protestantism in page after page and volume after volume. The collective identity of Klansmen was what the pages declared rather than the individual experience of Klansmen. The Night-Hawk presented how a typical Klansman should act but not necessarily how Klansmen acted. The official sources occasionally demonstrated that members were not necessarily performing like good Protestants, but, overall, the editors and leaders were more interested in emphasizing how one could be a part of their burgeoning Protestant community. Those printed pages rendered members as part of a faith community by describing the evidence of Christian behavior. The most common script for Klansmen’s behavior was Jesus’ model of living sacrifice. Jesus was the ideal for their actions, and their uniforms mapped Jesus’ message on their bodies. The Klan’s Protestantism, then, was key to defining and understanding its membership as well as the ideals of the order. Evans, Simmons, editors, and contributors defined their generalized Protestantism through a genealogy including Jesus and Luther, as well as in more secular notions of dissent. The Klan’s Jesus was crucial to how the order painted members as Protestant Christians. The burden of his example rested on individual Klansmen. The religious faith of the order was conjured for mass appeal, but individuals were to be believers who dedicated their lives to the righteous cause of the order. They were members of a religious community connected via reading and print. Official sources communicated expectations for members, who, through emulation, performed their commitment to Jesus and to their order. By being a Klansman, one proved his dedication to faith as well as nation, and he imbibed in the ideal worldview of the Klan. Leaders and members believed that God had smiled upon the Klan to unite the faith and save the nation. The order had God on its side. A Klansman from Arizona wrote a poem, “God in the Klan,” sacralizing the movement:

But then there came a Savior,

With a face turned from the clod.

The noble Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,

Another form of God.103

For the poet, the Klan was arguably divine, and that sentiment would likely have troubled Fry and Witcher more than naturalization ceremonies and renditions of Jesus. To be a “form of God” suggested the Klan’s reforms, ideals, and principles were legitimate, unchangeable, and dominant. Thus, its rendering of the faith was final and eternal, which proved to be essential not only in members’ personal lives and actions of the order but also in their vision of the nation. Faith became the centerpiece of the Klan’s nationalism. Moreover, faith imbued not just text and reading but also their construction and employ of patriotism.