Pitch is how high or low the sound is compared to the preceding or following sound.

Pitch is how high or low the sound is compared to the preceding or following sound.At its core, a piece of music is a structure in time built out of units of sound and silence. There are four predominant elements that make up any given sound:

Pitch is how high or low the sound is compared to the preceding or following sound.

Pitch is how high or low the sound is compared to the preceding or following sound.

Duration is how long the sound lasts.

Duration is how long the sound lasts.

Intensity is how loud or quiet the sound is and how that changes during its duration.

Intensity is how loud or quiet the sound is and how that changes during its duration.

Timbre is the “texture” of the sound. Timbre allows you to differentiate sounds with the same pitch, duration, and intensity. For example, you can immediately tell the difference between a trumpet and piano playing the same note for the same amount of time with the same intensity because the two instruments have very different timbres.

Timbre is the “texture” of the sound. Timbre allows you to differentiate sounds with the same pitch, duration, and intensity. For example, you can immediately tell the difference between a trumpet and piano playing the same note for the same amount of time with the same intensity because the two instruments have very different timbres.

Likewise, silence isn’t just the thing that happens between sounds. Our silences also have duration and even a sense of intensity and timbre: how stark is the silence, and what does the silence make the listener feel?

When structures of sound and silence fall into recognizable patterns—usually because of some combination of repetition and regularity—folks tend to be willing to say, “Yeah, okay. That’s music. I might not like it, but I agree that it’s some kind of musical something.”

In other words, “making music” means creating an intelligible structure of sounds and silences, usually by offering the listener some sort of recognizable regularity. This is absolutely the most generic, culturally neutral way to talk about making music.

That said, if you’re a native English speaker reading this book, you’re likely to think of music in terms of Western popular music, predominantly structures of sound and silence rooted in the artistic output of the peoples of the Western Hemisphere, with a special emphasis on the results of pale-skinned Europeans crashing into and generally abusing dark-skinned non-Europeans. The orderly sounds we enjoy every day wouldn’t exist if not for people like Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Igor Stravinsky, Ada Lovelace, Charles Babbage, Thomas Edison, Alan Turing, Leon Fender, George Beauchamp, Adolph Rickenbacker, Leon Theremin, Clara Rockwell, Robert Moog, Wendy Carlos, Phil Specter, Raymond Scott, George and Ira Gershwin, Howling Wolf, and Alan Lomax. But more importantly, our music could not exist without the contributions of an untold number of serfs, slaves, indigenous persons, displaced persons, nomadic peoples, traders, scoundrels, thieves, agents, publishers, flim-flam artists, fans, and fanatics. I’ll fall back on my betters and quote Stephen Jay Gould here: “I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.”

All that said—and being sort of heavy politics for a book about homebrew synths and garden-hose trumpets—here are some concepts that might help you in your musical explorations.

If you grew up with Western music in your ear, you’re accustomed to music having a regular, equally divided beat. Even when you hear a totally new song, I’ll bet you almost immediately sense when to tap your toes or clap your hands. This feels automatic for the same reasons speaking feels automatic: beginning before you were born and extending through your formative years, these were the sounds and patterns that you heard in your environment.

Beat is essential to musicality. There’s a whole slew of terms we use when approaching the idea of what the beat is:

Tempo is the speed, and often mood, of a piece of music. It might carry a specific name—usually Italian, like largo or allegro—or the composer might note how a piece is to be played: solemn, lively, steady rock, laid back, heavy, and so on.

Tempo is the speed, and often mood, of a piece of music. It might carry a specific name—usually Italian, like largo or allegro—or the composer might note how a piece is to be played: solemn, lively, steady rock, laid back, heavy, and so on.

Meter is usually given as a time signature, often rendered as a fraction, like 4/4 or 3/4. There are also specific named rhythms, like the blues shuffle, the Bo Diddley beat, or the clave rhythm I mentioned in Junkshop Percussion (Project 8, on page 121).

Meter is usually given as a time signature, often rendered as a fraction, like 4/4 or 3/4. There are also specific named rhythms, like the blues shuffle, the Bo Diddley beat, or the clave rhythm I mentioned in Junkshop Percussion (Project 8, on page 121).

BPM is the exact number of beats per minute at which a song plays. This is especially common now because electronic music and computerized composing, recording, and listening are such a huge part of our lives.

BPM is the exact number of beats per minute at which a song plays. This is especially common now because electronic music and computerized composing, recording, and listening are such a huge part of our lives.

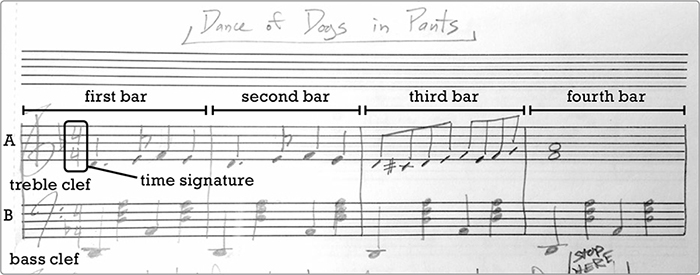

The basic unit of any Western piece of music is the bar (also called a measure). A bar is a group of sounds and silences of specific durations that lasts a specific number of beats. Western music, from classical concertos to death metal ballads, is very often composed of four-beat bars, meaning each musical sentence in that composition consists of four beats.1 This is written as 4/4 because there are four beats per bar, as represented by the upper four in the fraction, and each beat corresponds to one quarter note, as represented by the lower four. (I’ll explain what a quarter note is in the next section). For example, sing “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” while clapping. Each line of the song occupies one four-beat measure: the words star, are, high, and sky land on the fourth and final beat of each bar. On sheet music, this division into bars is represented with a vertical line, as shown in Figure C-1.

FIGURE C-1: An annotated sample of piano sheet music showing the first four bars of “The Dance of the Dogs in Pants” (an original composition). The upper staff, marked A and headed with a treble clef, shows the melody, or the higher-pitched bit played by the right hand; the lower staff, marked B and headed with a bass clef, shows the lower-pitched bass part, which incorporates both single notes and chords.

Not everything, however, fits into a 4/4 pattern. A waltz, for example, is three beats per bar, not four. If you try to count off a waltz as 1-2-3-4, you’ll find yourself stumbling as you run over into the next bar. A waltz is in 3/4 time, which means there are three beats per bar and each beat lasts for one quarter note. You count a waltz as 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, with the 1 stressed.

Now, listen to a few polkas and marches on YouTube. Counting these off as 1-2-3-4 probably feels funny, like you’re running two musical sentences together. That’s because you are. Polkas and marches are often in 2/4 time, meaning they have two beats per measure and each beat is represented by a trusty quarter note. You count music in 2/4 time as 1-2, 1-2, 1-2.

Ready for a challenge? Search YouTube for the Allman Brothers Band’s “Whipping Post.” Give it a listen and try to figure out the time signature. If you jump to the middle of the song, you’ll hear a bluesy three beats per bar in 3/4 time. If you jump back to that incredible intro, it at first seems like 3/4 time, too. But then, at what your brain initially takes to be a fourth bar, something happens that brings the bass line around like a whipcrack. It certainly isn’t 3/4 time. Whatever happens as the riff comes back around, it’s vital to what makes the song work. As it turns out, this intro pattern isn’t three bars of 3/4 plus something else; it’s best understood as a single bar of 11/4. Count it out, and you’ll see.

Even though the pattern is most rationally understood as 11/4, that’s not how the writer, Gregg Allman, understood it. In fact, he had no clue what 11/4 time was until his brother and bandmate, Duane, listened and said, “That’s good, man; I didn’t know you understood 11/4.”2 Greg had no idea what Duane was talking about, and Duane had to sketch it out on scrap paper to get the concept across. When Greg wrote the intro to “Whipping Post,” he’d counted it in his head as 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2—that is, three bars of 3/4 and a bar of 2/4, a pretty damn unconventional meter.

The point is that there are tons of possible time signatures, and the most important thing is to understand them to be descriptive, not prescriptive: you can play in whatever crazy divisions you want. Notation is a system for you to describe to others what you’ve done, not to limit what you’re doing.

Thinking of the beat as the smallest unit of music is really convenient, because doing so allows you to map out every moment in a song and ask yourself, “What am I doing at this particular beat? Am I making a sound? If so, how loud is it, what pitch is it, and so on?” We mark out these sounds as notes or sets of notes and the not-sounds as rests. A note shows the duration and pitch of a sound you make, and a rest just gives the duration of the silence. You can play pitches individually for a fixed duration (that is, as individual notes), or you can play pitches simultaneously in groups, which we call chords. You can play only one rest at a time. (Think about it—and if you have a counterclaim, email me!)

Durations are described in terms of the portion of the bar they take up. A whole note sounds for an entire bar, and a whole rest is silent for an entire bar. Therefore, in common time (4/4), a whole note or rest lasts for four beats. A half note or rest lasts for half a bar, which is two beats when playing in 4/4. A quarter note or rest lasts for one-quarter of a bar (one beat), an eighth for one-eighth of a bar (one half beat), a sixteenth for one-sixteenth of a bar (I’m sure you can do the math yourself), and so on.

We think of everything in terms of quarter notes when we play. I hold a whole note for a full four-count, a half note for a two-count, and so on. When I’m playing eight to the bar in common time—that is, rocking out, with everything in quick eighth notes—I count 1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and, which gives me eight things to say out loud to keep time to. If you’re playing sixteenth notes, count 1-ee-and-a-2-ee-and-a-3-ee-and-a-4-ee-and-a. Playing thirty-second notes? That’s too fast! Cut it out!

If I’m playing in waltz time (3/4), I have only three quarter notes per bar. In this context, a half note doesn’t last for one-and-a-half beats but instead is worth two quarter notes, taking up two-thirds of the bar.

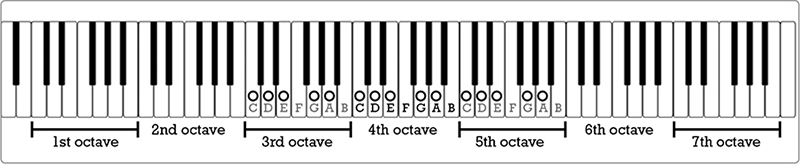

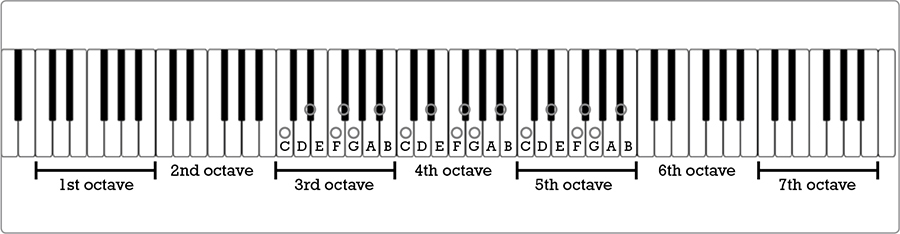

Pitches are assigned letters A through G, and they repeat in this pattern as the pitch gets higher or lower. In Western music, we tend to use A440 as the baseline to calibrate our other notes against. This is a 440 Hz pitch that we call A. Incidentally, the A string on your uke plays at 440 Hz. That said, we actually arrange our music around middle C, which is also called C4. This is the white key in the middle of a standard 88-key piano keyboard.

The letters we use to map notes repeat themselves in octaves, which are groups of the seven letters A through G. These groups correspond to groups of seven white keys on the piano. The repetition of these notes is based on their frequency: a given note has twice the frequency of the same note one octave lower. For example, A4 has a frequency of 440 Hz. The next higher A—called A5—is eight white keys to the right on a standard piano, and it has a frequency of 880 Hz.

A scale is a set of pitches of specific intervals. An interval is the difference between the frequencies of two pitches—and thus, intervals map to distances between piano keys, ukulele frets, and so on.

Just as with time signatures, there are tons of different scales, and you don’t need to learn a specific scale or limit yourself to a given scale in order to play. But when you do chose to stick to a given scale, it’s typically easier to make patterns of sound and silence that are easily intelligible (and thus more easily recognized as music). Because lots of Western folk tunes, like “When the Saints Go Marching In” and “Camptown Races,” are confined to a single major diatonic scale,3 most of the eight notes in a diatonic scale can be made to sound pretty good next to each other.

A pentatonic scale is a scale of five notes that, for reasons involving brains and physics, basically always sound good together—even cross-culturally! In Western music, we tend to think of the pentatonic scale as a subset of the diatonic scale (see Figure C-2), but that’s just one perspective. I’m sure plenty of Laplanders, West Africans, Native Americans, auditory neurologists, and hip-hop professors would argue that with you.

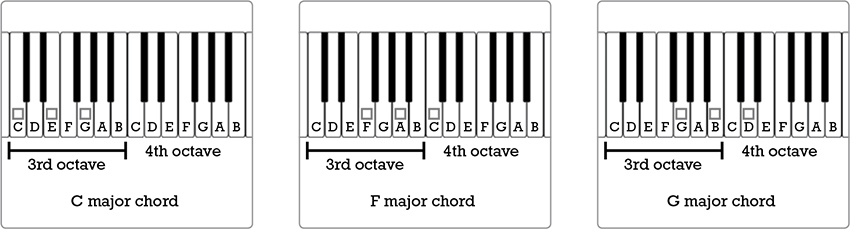

Scales and chords are named for their root, which is the note they’re constructed on top of. The root is usually the lowest note in the scale or chord and the first played in the scale. Play all the white keys between middle C and C5, and you’ve played a C major scale, which is a diatonic scale and therefore a staple of Western music. Play the middle C, the D above it, and the G above that simultaneously, and you’ve played a C major chord.

FIGURE C-2: The circles indicate three octaves of the C major pentatonic scale. Want three octaves of the C major diatonic scale? Just play all of the white keys. (Keyboard image by Artur Jan Fijałkowski)

Pianos also have five black keys per octave. These keys are named for the white keys to either side. So, for example, the little guy between C and D can be called either C-sharp (C♯), meaning it’s a touch higher-pitched than C, or D-flat (D♭), meaning it’s a touch lower-pitched than D.

If you play a full octave from lowest to highest and hit each white key, you’ve played a diatonic scale. Play a full octave from lowest to highest hitting every key, black and white, and you’ve played a chromatic scale. It’s tricky to play a fully chromatic composition that sounds good,4 but you’ll hear the term as you dabble in music, so I wanted to make sure we covered it. In music, chromatic just means we use every possible note in a given octave.

Because I love you, I’ve summarized the concepts covered in this section in Figure C-3.

FIGURE C-3: An annotated 88-key piano keyboard

The Gory Details: Intervals, Steps, Half Steps, Major, and Minor

The term intervals refers to the distance between two pitches. The unit of that distance is half steps. For example, any two keys on the piano are a half step apart. A move from middle C to the black key just to the right—that is, C-sharp or D-flat—is a half step up. Move to the next white key, D, and you’ve gone a total of one whole step from C. There are 12 half steps in an octave. Likewise, each fret of a guitar or uke corresponds to a half step.

Chords and scales are often described in terms of the intervals separating each note. For example, a major chord is composed of a root note, the note four half steps higher, and the note three half steps higher than that. A minor chord is composed of a root note, the note three half steps higher, and the note four half steps higher from there. A major scale goes root, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step, which brings you to the root one octave higher. A blues scale—like the one illustrated in Figure C-6—is root, one-and-a-half step, whole step, one-and-a-half step, half step, one-and-a-half step, whole step, again bringing you to the root one octave up.

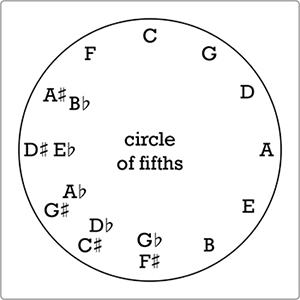

The circle of fifths, shown in Figure C-4, is a geometric way of representing some neat relationships among notes in the full 12-note chromatic scale. Remember that each note is a specific frequency. For example, A4 is 440 Hz, and its octave is 880 Hz. Play any two frequencies simultaneously, and you’ll notice that some sound sweet together, while others are annoying. Pitches that sound good together are said to be consonant, with some intervals being more consonant than others. The more consonant two notes are, the safer it is to play them next to or on top of each other. Try mashing a couple of piano keys, plucking a pair of uke strings, or setting off two different brands of smoke detectors, and you’ll quickly develop a sense of consonance.

FIGURE C-4: The circle of fifths. Pick any pitch. Move one click clockwise, and you have its fifth. Move one click counterclockwise, and you have its fourth. Most blues, folk, punk, and rock songs are composed of a root, fourth, and fifth.

There are varying degrees of consonance because of the way the two tones’ sound waves mesh or crash together against your eardrum. If the frequencies don’t divide evenly into each other, they sound bad because they’re hard for your brain to decode. A note and its octave always sound fine together because their frequencies divide so easily: the higher note always has twice the frequency of the lower note—a ratio of 2:1. Meanwhile, playing any piano key together with the key directly next to it always sounds pretty bad because that interval is too narrow: there’s no way for your brain to resolve one pitch into the other. Brains hate that.

The fifth is the next most consonant interval after the octave. The frequency ratio of a fifth to its root is pretty close to 3:2. For example, G and C are a fifth apart; middle C is 261 Hz, and the G above that is 391 Hz. So playing a fifth—either both tones at once or moving from one to the other—will always sound fine. It will resolve.

The circle of fifths encodes tons of cool relationships—for example, the versatile and popular power chord is just a root and its fifth. But let’s start with the most basic relationship illustrated by the circle of fifths, one that’s really handy for building your own compositions. Pick a root note. We’ll say C (if you have an actual or virtual keyboard handy, now is a good time to fire it up). Flip to Figure C-4 and find C on the circle of fifths. Now move one pitch clockwise, and you have G, the fifth that meshes with that root. You now know C and G will always sound good together. Try hitting them on your keyboard—simultaneously and then one after the other—and you’ll hear how compatible they are.

Flip back to the circle of fifths diagram and move one click counterclockwise from your root to find its fourth. With C as your root, that puts you at F. Play them together. The fourth won’t sound quite right—not terrible, but certainly less consonant than the octave or fifth. Your ear has more trouble fitting it with the C, which creates tension. Moving from the root to the fourth creates the sense that something should come next because the fourth and root just don’t quite resolve. Go from the fourth to the fifth or back to the root, and that tension releases.

Pick a root, fourth, and fifth and play around with them. You’ll find that different amounts of tension release when you move between notes, with a partial release when you move from a fourth to the fifth and a full release when you return to the root. Try making a pattern using C as your root, G (its fifth), F (its fourth), and C# (the sourest interval you can get). If you pin your structure of sound and silence to the C and G, sprinkling in a few C#s to create lots of tension and then using the F to smoothly transition back toward G, you’ll find lots of workable musical patterns—which is to say, you’ll be composing a song very much in the Western tradition. Congratulations!

* NOTE: When folks talk about the fundamental patterns that underlie a melody and chord structure, these intervals are usually represented by roman numerals. The root is I, the fourth is IV, the fifth is V, and so on.

Let’s put theory into practice. If you have an instrument you’re comfy with, swell! Otherwise, find a piano or music keyboard and use Figure C-3 as a crib sheet. In a pinch, download a digital keyboard app, whether on your phone, tablet, or computer. I like the “Virtual Keyboard” at http://www.bgfl.org/virtualkeyboard/; it has a limited range, but it assigns the keys rationally to the computer keyboard, making it possible to play a few chords.

Musically speaking, the blues is a sonic equation that your brain is very used to solving. If something bizarre has happened and you’ve somehow never heard the blues, please proceed directly to YouTube and listen to Howlin’ Wolf’s “Evil,” Bessie Smith’s “Empty Bed Blues,” Big Bill Broonzy’s “C.C. Rider,” Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog,” Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues,” and the Georgia Satellites’ “Keep Your Hands to Yourself.” That’s 60 years of the blues being used to diverse effect, and damn are you in for a treat!

The Gory Details: The Music History of Two Hound Dogs

Presley’s “Hound Dog” and Thornton’s “Hound Dog” are the same song. It was originally written for Thornton—a Southern-born musician with gospel roots who made her R&B career in Harlem—by the songwriting team of Leiber and Stoller, a pair of teenaged New York Jews. Leiber and Stoller worked closely with Thornton to craft a signature comeback song that drew on Thornton’s sexy, take-no-crap stage persona. Leiber/Stoller/Thornton’s “Hound Dog” was an enormous hit, spawning dozens of covers, spoofs, and “answer songs.” Presley’s version is actually a sanitized parody of the song, with modified lyrics made famous by Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, a Vegas lounge act composed of Italian Americans transplanted from Philadelphia. When Presley licensed “Hound Dog” from Leiber and Stoller and made it a number one hit (again), they knew him only as “some white kid” from Tennessee. There’s something about this story—its diverse cast of characters, their fundamentally incompatible lived experiences drawn tightly around a fairly vapid pop confection, the fact that there’s no reasonable way to apportion authorship to this iconic tune—that, for me, quite aptly summarizes all of American music.

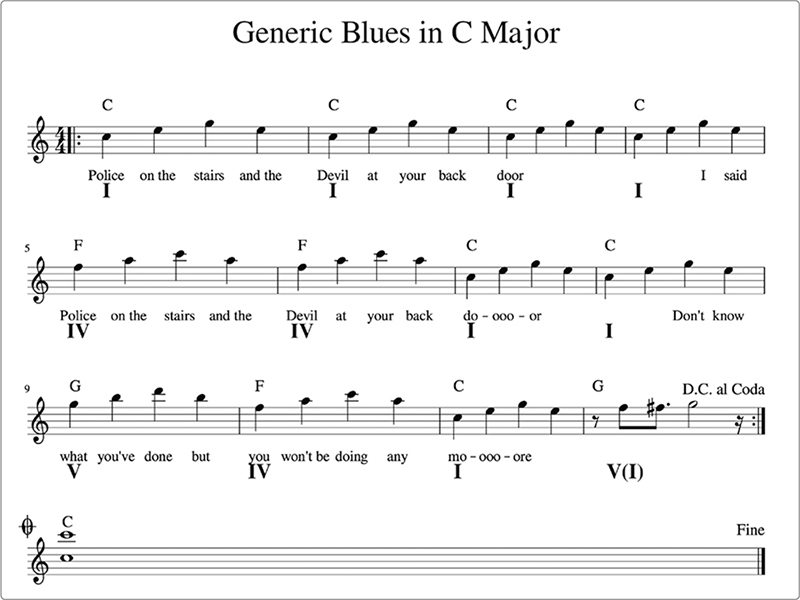

In songs that follow a 12-bar blues format, you play 12 musical sentences, which comprise a verse and chorus, and then repeat—likely with new lyrics—ad libitum. Take a look at the blues chord progression illustrated in Figure C-5 (use the roman numerals as your guide).

FIGURE C-5: This basic 12-bar blues progression in C comes complete with public domain lyrics (use them as you like!) and a snappy turnaround at the 12th bar, which creates a transition to loop back to the 1st bar. The letters above each staff indicate which chord should be played when. The roman numerals under the lyrics highlight the generic chord structure of the 12-bar blues. Once you’ve repeated the first 12 bars as many times as you want, wrap up the song by continuing into the 13th bar, which is the tune’s coda.

For this exercise, your root is C. Let’s start by treating those C, F, and G chords as just single notes (that is, play just a C note in place of the C chord, just an F for the F chord, and so on). It’s conventional to anchor melodies in the fourth octave, and chords or bass parts in the third. So fire up your piano keyboard, check out Figure C-6 for help navigating, and then find the fourth octave with its C, F, and G notes.

FIGURE C-6: Three octaves of the blues scale in C on a piano keyboard

Let’s begin! Count out some four-beat 1-2-3-4 bars. For the first four bars, hit C4—the C at the beginning of the 4th octave—on the 1. For the 5th and 6th bars, play F4 on the 1 instead. Then, hit C4 on 1 for the 7th and 8th bars. Hit G4 on 1 for the 9th, F4 on 1 for the 10th, C4 on 1 for the 11th, and, finally, play your 12th-bar turnaround. I went with G here because it’s snappy, but following the generic blue progression (rendered in roman numerals), you could just as easily use a C instead. Repeat as long as you like. Even the first time through, and despite being stripped to its bare bones, you’ll certainly hear that this is indeed the blues. It’s just that easy!

Now let’s flesh out those bare bones, starting with chords instead of just the root notes of each. Once again, the circle of fifths proves handy: a power chord is composed of a root and its fifth. Flick back to Figure C-4 to see that the C’s fifth is G. Play C3 and G3 together for a C power chord—perfectly suitable to serve as the root, or I, in a blues progression. Check the figure again, and you’ll see that F’s fifth is C, so playing an F3 and C4 for an F power chord serves as our IV. Finally, G’s fifth is D, so play G3 and D4 together for a G power chord, which is our V.

Go through the “Generic Blues in C Major” again, this time playing your power chords instead of just single notes. You’ll immediately hear the difference: where before you just had bones, now you’ve got a little muscle, too. Play it several times.

Once you get a feel for the song, try playing power chords several times per bar. Hit your chord on every quarter note—that is, at each number on the count. It’s a nice, driving beat. Then, try hitting the chord just on the 1 and 3; it’ll feel laid back. After that, go through one more time, now hitting your chords on the 2 and 4; it might feel slow but aggressive, like a tiger pacing, ready to pounce. Now, try something different. Make it swing, make it grind, or nail it down eight-to-the-bar.

When you tire of pounding out those power chords, try doing the same thing with the three major chords illustrated in Figure C-7.

FIGURE C-7: The C major, F major, and G major chords

Finally, you’ll want to add a melody. I’m not going to walk you through the simple one I’ve scored in Figure C-5—reading sheet music is beyond the scope of this appendix, and there are plenty of online resources if you’re interested. However, I’ll give you a clue: each measure of the melody (save for the 12th) is just the three notes for that measure’s chord played evenly for the four-count. For example, in the 1st bar, the four notes in the melody are C, E, G, E.

If you want to graduate up to full-blown blues, learn the blues scale illustrated in Figure C-6. Practice playing the C blues scale backward and forward. Compared to the C major diatonic scale and the major pentatonic scale (shown way back in Figure C-2), the blues scale is sort of crazy, right? But deliciously so—feel how wonderfully it builds and releases tension compared to those humdrum major diatonic and pentatonic scales. Also, feel how this tension changes when played against different chords: the first two notes of the blues scale, played one after the other, clash hard against each other when played over the C major chord, but they almost-sorta-kinda work over F major. How do they feel when matched with G major? You can build a whole song with just those two notes and three chords.

Armed with the “Generic Blues in C Major” chord progression, your fistful of chords, the lyrics in Figure C-5, and your blues scale, make up your own melody for this sad tale of being caught between a rock and a hard place. Then, make up a new verse. Then, make up whatever you want.

Go, cat, go: make a good noise now!