1Disruption Happens

Technology-as-a-Service

Playbook

How to Grow a Profitable

Subscription Business

Thomas Lah

J.B. Wood

Copyright © 2016 Technology Services Industry Association

ISBN: 978-0-9860462-3-0

Número de Control de la Biblioteca del Congreso: 2016938814

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the authors, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

Printed in the United States of America.

Contents

Chapter 3 Digging an Economic Moat for Your XaaS Business

Chapter 4 Stressing Traditional Organizational Structures

Chapter 6 The Power of XaaS Portfolios

Chapter 7 XaaS Customer Engagement Models

Chapter 8 The Financial Keys of XaaS

Chapter 9 The Case for Managed Services

Chapter 10 Changes in the Channel

1Disruption Happens

How can you spot a tipping point? Malcolm Gladwell, whose book, The Tipping Point , 1 helped popularize the term, says it’s that magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behavior crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire. Well, we think one has come to dozens of business-to-business (B2B) and business-toconsumer (B2C) technology industries.

Ten years ago, we first stood in front of thousands of tech executives and worried aloud that the cloud era was going to disrupt the tech industry more profoundly than any other transformation in its vaunted 50-year history. Our worry was not rooted in disruptive technology but in disruptive business models. Big companies like IBM, HP, and Oracle have all weathered generational changes to computing models and architectures many times. Handling new waves of technology is old hat; they have plenty of plays for that. But we worried that this perfect storm of new technology and new business models could re-cast the very foundations of market leadership in the industry.

A lot has happened since that decade. Unless you have stubbornly avoided all business media over the past few years, it is impossible to have missed the interest in subscription business models, not just in IT but it nearly every technology-related industry. Today’s energy surrounding subscription business models is the follow-on to the buzz a few years ago about the “sharing economy”—something that Time magazine said was one of the top 10 ideas that would change the world back in 2011.The attraction of the sharing economy was and is the ability to simply access rather than own physical and human assets. For the provider, it produces recurring revenue streams that keep customers spending for years—even decades.

Although subscription business models and the sharing economy can manifest themselves in many industries, this book is concerned only with tech and near-tech industries. Even more specifically, we are focused on highly cloud-enabled, technology-as-a-service offers. The categories of these offers take many popular names. There are software-as-a-service (SaaS) offers, platform-as-a-service (PaaS) offers, infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) offers, managed services, and so forth. To keep it simple for the rest of the book, we are going to refer to them collectively as XaaS. You can make the “X” whatever you want. It simply means that you are offering sophisticated computer software, hardware, industrial equipment or devices, and/or services in an “as-a-service” consumption model to your customers. We would expect some or all of the offer to be delivered through the cloud. If you are selling subscriptions to razor blades or fine wine over the Internet, this book probably isn’t for you. On the other hand, if you are involved in the strategy, development, finance, marketing, services, or sales of complex, cloud-based technology solutions in IT, industrial equipment, health care, or consumer markets, and terms like SaaS and managed services resonate with you and your team . . . then keep reading. We have some interesting observations to pass along. Very importantly, if you are involved in traditional (asset-based, on-premise) technology and you are wondering what XaaS technology will mean to your job and your company . . . then definitely keep reading. That’s because your company is about to be caught up in the business model tipping point. To remain competitive, you will not only need new offers, but you will also need a new way to operate. Being connected to your customers is the catalyst.

Before you begin, you might be asking yourself: Just where are these observations coming from? OK, fair question.

Our answer begins with this statement: We don’t know all the answers, and anyone who tells you they do should be shown the door. It’s still early days in assessing how the cloud era of tech will fully disrupt the technology industry; predicting the future is dicey. It’s like predicting the future of the clean energy industry. It’s hard enough to figure out which technical approaches will ultimately win the market, much less what the best business practices of the new leaders will be. So, who are we and why this book? The answer is that we run the Technology Services Industry Association (TSIA). As one of tech’s largest industry associations, our company gets to uniquely study and talk with hundreds of the world’s most successful technology and industrial companies each and every day. We are an incredibly research-intensive bunch. We have experienced industry executives, PhD researchers, and data analysts looking at all the data we collect from public sources and from the companies themselves. We field thousands of formal inquiries annually from management at both traditional and XaaS companies wanting to know about the trends and best practices in running a successful business in this time of radical change. They want to know what lessons we are learning from our research on top-performing companies because we have access to data that is simply not available in the public domain. It’s from all this research and interaction that we draw our observations. So, though we can’t predict the future, we think we may be in one of the best positions to dissect and debate it. Most importantly, we think some winning patterns are emerging. That is what we want to share in this book. You might not agree with all of our observations, and not every one might play out. But, we think they are important for every executive and manager in the tech world to be aware of and consider. It’s a tricky time. Are we at a tipping point? If so, what will it mean to the traditional business models we know and love? How do we prepare? What will successful XaaS organizations of the near future look like?

In a nutshell, here is what we have learned after studying the topic from multiple angles for 8 years: XaaS is not just technology that is priced by the month and hosted in the cloud. If it were that simple, you wouldn’t need this book. We believe that, as the enigmatic smoke clears around the cloud, what’s emerging is an image of success in XaaS business models that is fundamentally different from traditional tech. It’s something that goes way beyond the technology and the pricing model . . . something that cuts deeply into the underlying business model the tech industry has grown comfortable with. It’s just a new way of running a tech company. And it’s powered by your real-time connections to the customer. What’s most interesting—why we wrote this book—is that NOBODY truly knows what that new way is! It’s a fact that there is no B2B subscription business that is as rapidly growing and as profitable as the traditional tech bellwethers were in their heyday. Only the XaaS CEO who can make that claim can write the definitive book. And really, they should accomplish it more than once to prove that they have perfected the formula. Until that day, we are all in this together—all trying to break the enigmatic code for the profitable XaaS business. We are debating whether the tipping point has arrived and what life after that will look like. Let’s face it: The cost of building software is dropping fast. We think it’s the business execution around the code—not just the ability to write code—that will determine the success or failure of future icons.

Just how different might the winning B2B/B4B XaaS company look? Here are 10 assertions that are a sample of things we will cover:

• The ability to “prove deliverable business outcomes’” will supplant “win the feature bake-off” as the central focus of senior leadership at tech companies. This will cause a dramatic re-thinking of investments and top talent allocation. Offers will “go vertical” in order to better deliver full value to the customer. Services will move from the back of the bus to the front of the bus. But at the same time . . .

• Software will eat services. The ability of technology companies to reduce technical complexity and build best customer practices into their software will be a defining characteristic of successful XaaS providers. Value-added services will survive and prosper as a concept. However, labor-delivered services (except highly consultative expertise) will still be viewed by management as a boat anchor. Eventually, development will accept that their charter includes the “full product” and not just a collection of features. They will build all the capabilities into the product that are needed not only to win the feature bake-off but also to enable the differentiated services that will drive adoption, encourage expansion, reduce sales costs, and have a plethora of other objectives. These are the capabilities needed to create downstream profits and sustained competitive advantage.

• Suppliers and customers will increasingly compete as every company becomes a tech company. Low-cost software development will turn industrial buyers of technology into technology producers themselves. Technology resellers will find their original equipment manufacturer (OEM) suppliers competing with them through cloud-enabled, direct models. Large XaaS providers will manufacture their own hardware and build their own software, no longer being a buyer of technology but actually overseeing the manufacture of the products they use. (By the way, all of this is already happening at scale.)

• The act of selling will undergo radical change. Customers can now self-serve a huge amount of the information they need to make a technology purchase decision. They will be able to self-serve on simple purchasing decisions like low-cost XaaS trials or renewals. Even on more complex decisions they will have less and less interest or patience for “company overviews” or “demos” from their sales rep. They will know all that. They will want to discuss the “last mile.”They will want to know specifically how your key features will lead to improved business outcomes for companies in their specific industry. Selling will become a process, not a heroic act!

• Delivering and measuring customer success will become a defining characteristic of market leaders. If you don’t have a systematic way to make more than 90% of all your XaaS successful, you will not be profitable. We are not just talking about success in your terms; we are talking about success in the customer’s terms.

• Organizational structures will be significantly reinvented with highly integrated development, marketing, sales, finance, and service teams swarming around specific customer segments. Regional autonomy over international markets will decline, and centralized processes and systems will ascend. Even traditional departmental profit and loss statements (P&Ls)—the archaic command and control systems we dearly loved—will collapse under the weight of the new operational and organizational models, where expense dollars in one department yield revenue growth or cost savings in a totally different department.

• Channel partner models will get re-thought and reconstructed. Many resellers will perish in the transition. New kinds of partners will be added. How the OEM and their partners work together for a particular customer will be radically redefined as the old notion of direct or indirect customers is replaced by a model where both parties serve every customer.

• The employee skill sets that companies covet will expand from the traditional obsession with hiring technical and sales skills (that built the last generation of tech companies) to including deep vertical industry and business process expertise. Suppliers will start hiring experts from their customers. Any human being that combines both deep vertical market expertise and either great technical skills or great sales skills will write their own ticket.

• The market advantage pendulum between innovation and scale—the one that has swung so far toward innovative new companies that are taking share against much larger, traditional tech companies—will begin to swing the other way. Large tech companies will begin to enable their global footprint of customers, partners, and employees to create competitive XaaS advantages that many small but disruptive companies struggle to match. Right now, the traditional companies just want to study the disruptors. As the disruptors grow, their interest in how to scale globally will grow. Suddenly, they will become curious as to how the traditional tech companies operate at such huge scale.

• The traditional cost structures that high-tech and near-tech industries have supported with high unit prices for their products will be destroyed. Unit prices for nearly everything will continue to come down. The labor-intensive operating models for marketing, sales, services, and general and administrative expense (G&A) will be torn apart and reinvented. Heroic acts will be replaced by processes. Those processes will become automated. They will interact with data and best-practice models. That unified model will “own” the customer—who they are, what outcomes they are trying to achieve, where they are in the process, what interactions are needed next, and how they can expand to higher levels of value. We will still need a human face to the larger customers, but they will be talking about what the model tells them to talk about.

The Magnitude of the Transformation

As part of our research, we have been tracking the performance of 50 of the largest providers of technology solutions every quarter over the past 10 years. In 2015, the companies in the TSIA Technology & Service 50 (T&S 50) index were generating average operating incomes, on average, north of 11%. Figure 1.1. demonstrates the high operating incomes of these enterprise tech companies compared to other well-known profitable companies.

As we discussed in our last book, B4B , 2 the B2B technology industry created some of the most profitable business models in the history of business models. As Figure 1.1. indicates, the average profitability of the 50 companies in this index is higher than that of blue-chip companies like General Electric (GE) and Walmart. But now these beautiful business models are under duress. Since 2008, the combined top-line revenues of companies in the T&S 50 index have been shrinking dramatically. By the fourth quarter of 2015, product revenues were shrinking at an average rate of –8% per year for companies in the index. Remember, these are companies that were always considered high-growth and highmargin product businesses! Figure 1.2. documents the dismal decline of combined product revenues and the rise of service revenues for these companies since 2008.

FIGURE 1.1 Operating Income of Legacy Technology Providers

Legacy technology companies have become desperate for top-line growth. The natural place to pursue that growth is the fast-growing world of XaaS and subscription revenues. However, the profitable business models for XaaS have yet to be proven. For the past 3 years, we have been tracking another index called the Cloud 20 that consists of the largest publicly traded XaaS companies. Although revenue growth for these companies has been phenomenal, profitability has been elusive. Figure 1.3. provides a comparison of key performance metrics of revenue growth and net operating income between XaaS companies and traditional technology companies we track. 3

In theory, these new XaaS business models have incredible potential. Tien Tzuo is founder and CEO of Zuora, a SaaS company that provides software for subscription billing, and former chief marketing officer at Salesforce. He has become an outspoken advocate for the subscription business model. In many of his articles, interviews, and speeches, he points to the following benefits of the subscription business model: 4

• Customers in all marketplaces want flexibility in how they consume.

• Customers only want to pay for what they use, and subscription models are designed to support that desire.

• Subscription relationships provide greater insight into what customers are consuming and what they value.

• Subscription business models create predictable, renewable revenue streams.

• Subscription business models create the opportunity to produce highly profitable revenue streams as more and more customers are served from a common platform.

FIGURE 1.2 Product and Service Revenue Trends in the T&S 50 Index

FIGURE 1.3 Financial Performance of XaaS versus Traditional Technology Providers

Mr. Tzuo has many valid points—especially when subscription business models are built on cloud-based platforms. A centralized delivery model enables several advantages over traditional on-premise delivery models where the customer installed and managed the technology on their own. Hosted offers allow providers to quickly release new capabilities to all customers. With customers interacting on a hosted platform, providers can gain visibility into which customers are adopting and which are not. Also, providers can use analytics to build best practices that all customers can leverage. XaaS companies should absolutely benefit from economies of scale. More users on the same platform should result in higher profits. These are just a few of the unique advantages of the XaaS model.

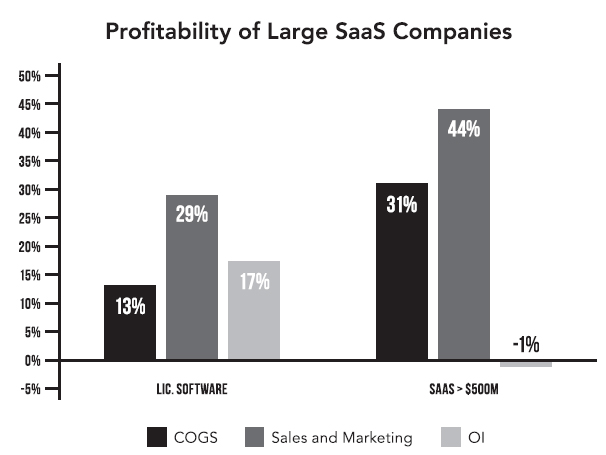

Unfortunately, at this point in time, the majority of XaaS companies that we track are not exhibiting proof that scale automatically equates to higher profitability. Figure 1.4. compares the financial performance of SaaS providers with annual revenues of more than $500 million against traditional license software companies of the same size.

Clearly, there are challenges facing technology companies executing subscription business models. In a subscription model, you obviously need to acquire customers. More importantly, you need to keep those customers on the platform. Most importantly, you need to convince those customers to spend more money with you over time. High sales costs, customer churn, and offer commoditization create downward drag on the profitability of the subscription business model. The sharing economy is not yet proving a panacea of profitability in tech.

FIGURE 1.4 Profitability of Large SaaS Companies

For now, investors seem to be OK with this reality for highgrowth, pure-play XaaS companies like Salesforce and Workday. However, investors have high profit expectations for legacy technology companies such as Autodesk, Cisco, Microsoft, Oracle, and SAP. As these legacy companies attempt to pivot to XaaS offers to secure growth, Wall Street becomes apprehensive. All these headlines—and many more—have starting appearing since late 2014:

• “Wedbush Downgrades Autodesk, Worried about Business Model Transition” 5

• “Will Oracle’s Transition to Cloud Impact Its Margins?” 6

• “When Will Microsoft Have to Stop Milking Its Windows Cow?” 7

• “SAP Profit Down 23% after Cloud Move 8

As these companies attempt to navigate the expectations of investors, they are dealing with the reality that new XaaS offers require a significant investment in multiple areas such as:

• New technology platforms

• New pricing and financial processes

• Revised sales and marketing motions

• New service offerings and capabilities

• Reengineered partner models

So at the same time that revenues decline from our highly profitable legacy offers and we begin to replace them with new subscription offers, additional investments must be made. In B4B , we referred to this phenomenon as “the fish” (Figure 1.5. ).

FIGURE 1.5 The Fish Model

Before this industry transition is completed, every legacy technology company will need to swallow this financial fish as they migrate from old to new business models. You can already see the consequences of this transition as companies begin navigating the rough waters. Some legacy companies signal tepid growth and lower profit expectations in the short term as they navigate the transition:

• “Adobe’s (ADBE) Strategic Shift Will Lead to Growth in the Long Term” 9

• “SAP Sees High Cloud Profit Potential in Long Term” 10

• Other companies simply take themselves out of the public eye:

• “Dell Officially Goes Private: Inside the Nastiest Tech Buyout Ever” 11

• “JDA Software to Go Private in $1.9 Billion Deal” 12

• “BMC to Go Private in $6.9 Billion Deal Led by Bain, Golden Gate” 13

• “Dell Buying EMC: Is This the End Times, or the Road to Salvation? (In any case, the enemy is now Amazon)” 14

• “Informatica, Now Private, Announces New Leadership Team” 15 And other companies are breaking into smaller companies:

• “HP’s Big Split: The Good, Bad, and Potentially Ugly” 16

• “Why Symantec Split Up into Two Companies” 17

Regardless of the tactic, the fish is still sitting there—waiting to be swallowed. The pivot from traditional technology business models to new XaaS is inevitable. Almost every legacy technology company will need to establish some form of a XaaS offer. At the same time, new, pure XaaS providers will eventually need to pivot from unprofitable, high-growth business models to business models that generate more money than they spend. This book is designed to assist in both scenarios.

The Purpose of This Book

It does not matter if you are a 50-person, well-funded XaaS startup or a $1 billion license software company: You will need to answer these three questions in the next few years:

1. How will we make our XaaS offer successful and how will we evolve our portfolio?

2. How are we going to cost-effectively land, deliver, expand, and renew customers of our XaaS offer?

3. What is our sustainable financial model for XaaS?

We have been collaborating with the industry for the past 8 years to find realistic answers to those three questions. This book provides a series of frameworks, observations, and recommendations that can help any size company navigate the gauntlet of decisions that must be made as you enter the brave world of the subscription economy. The content of this book will be highly relevant if you find yourself in any of these three scenarios:

• I am responsible for helping my company stand up and optimize a XaaS offer . If you find yourself in the middle of a XaaS offer, then this book is for you. It doesn’t matter if you are the product manager for this new offer, the services executive responsible for supporting the new offer, or the CFO who is scratching your head over how to make money with this offer. There is detailed information on the plays your company will need to run to build a profitable XaaS offer.

• I need to educate others in my company on how they need to change in order to empower our new XaaS offer. If you are convinced that XaaS disrupts many company functions but you are struggling to convince others of this reality, this book is for them. Use this book to help carry key messages to these organizational functions. Sales, marketing, services, finance, and product engineering can all benefit from the content in these pages.

• My company is not even talking about XaaS offers, but I want to understand how XaaS may impact my company. Our point of view is that this industry transition to XaaS models will eventually impact every company in some way, shape, or form. The shiny new capabilities that are part of XaaS offers are making traditional offers look, well, traditional. Dated. Limited. This book can serve as a wonderful primer for ramping yourself up on the nuances of XaaS business models.

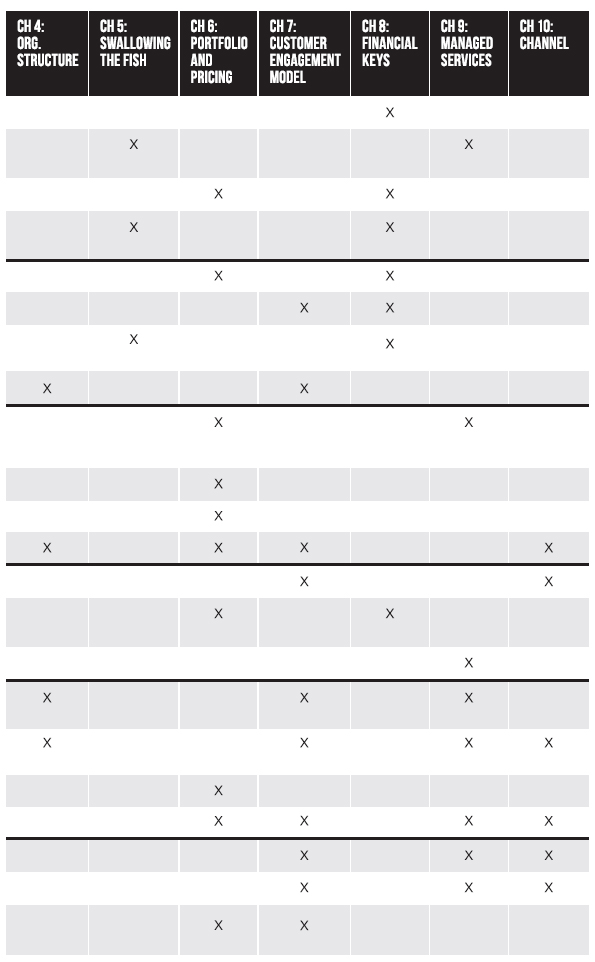

One warning concerning the content in this book: We cover a lot of ground. Not every chapter will be for every reader. For that reason, we recommend you leverage Figure 1.6. to prioritize which sections of the book you should tackle in your first read-through.

Using the XaaS Playbook

Unlike previous books we have written, the Technology-as-a-Service Playbook glides up and down between overarching strategic frameworks and “rubber meets the road” tactics. For that reason, we have created a cheat sheet to help prioritize the content that will be most relevant to various readers based on the specific questions the reader is attempting to answer. Figure 1.6. lists some of the most common questions related to XaaS offers and highlights the recommended content.

FIGURE 1.6 Technology-as-a-Service Playbook Reader Cheat Sheet

The tipping point is nigh. Traditional product sales are declining. XaaS revenues are growing at double and triple digits. Sitting on the sidelines is no longer an option for traditional companies. At the same time, running a cash-burning XaaS financial model is becoming a riskier proposition every day. Something has to change. We hope you find this playbook useful, and we hope you enjoy the journey.

2The 3x3 of XaaS

So Many Choices

This is a book about the plays a company can run as they work to establish and optimize a technology-as-a-service offer. Obviously, the offer has to have value to the user, or as it’s frequently called, product-market fit. We can’t help you with that. It’s up to you and your team of experts to target the opportunity and establish a uniquely valuable proposition. Fortunately, the cloud and the Internet of Things (IoT) will open up thousands of chances to do just that. But believe it or not, that’s just the beginning. Once you have the opportunity in sight and the core product working, an entire new set of issues begin to play out. That’s where this book comes in. We want to promote discussions among your team that can accelerate your thinking and increase the chances that your great idea is a commercial success.

But where to begin? What can we learn from the cacophony of XaaS offers and activities already in the marketplace? Some of these offers lead with free trials, such as McAfee’s suite of security-as-a-service offers. Customers can try the service and then determine if they want to continue paying. 1 Some XaaS offers provide all the customer requires in one simple subscription price. Apptio property management software provides a great example of this approach. On its web page, it leads with the tag line: “No surprises. No complicated list of features that cost extra. Everything you need to run a more successful business.” 2 Still other XaaS offers list multiple components a customer can choose to purchase based on business requirements. Veeva Systems, which secures over 25% of its revenue from add-on services surrounding the core technology subscription, offers professional services, managed services, administrator training, environment management, and transformation consulting. 3

Looking across XaaS providers, it may seem challenging to discern common patterns related to things such as offer types and pricing models. One industry article defines 12 distinct ways to price a SaaS offer. 4 What pricing model makes sense for your XaaS offer? What should be included in the offer? One way to bring some clarity to the chaos is to use the filter of time.

Profit Horizon

As we have studied the XaaS marketplace, we believe there is one defining factor in determining XaaS offer strategy: the profit horizon, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Profit Horizon: The length of time targeted to achieve significant GAAP profits.

By GAAP profits, we simply mean a company is considered profitable when applying traditional, generally accepted accounting principles. This is an important distinction, because many XaaS providers are currently applying non-GAAP metrics to communicate the financial health of their businesses. The argument for non-GAAP is that non-cash items, such as employee stock option expenses or the amortization of intangible assets obtained through acquisition, should be excluded to provide a more meaningful view. We don’t want to get into the debate about GAAP or non-GAAP, so we choose to set GAAP profits as the bar since no one will argue with you once you have achieved them!

FIGURE 2.1 The Profit Horizon

A plethora of companies are building XaaS offers that they believe may take many years to capture significant market share, aggregate customers, and create the economies of scale needed to make GAAP profits. They may not even fully understand how those revenues will be monetized or how profits will be created. These companies have a “future” profit horizon. There are different profit horizons for companies that feel they need less time. Perhaps a company established a XaaS offer several years ago. It expects to achieve a critical mass of customers and revenue in the next few years or so. Its profit horizon is “mid term,” but not current. Finally, if you have a XaaS offer that you believe can get to a critical revenue mass and be profitable within the next year or two, then your profit horizon can be defined as “current.”You are expecting or needing the offer to generate profits for your company relatively quickly.

The 3x3 of XaaS: The First Dimension

Applying this concept of a profit horizon to XaaS offers in the marketplace, we can easily recognize three common, distinct profiles of XaaS solution providers, as seen in Figures 2.2 , 2.3 , and 2.4 and described below.

1. Future Value Aggregator (FVA). These are XaaS providers that believe the real financial value of the offer will be realized at some date in the distant future. The method of achieving profitability may be vague or unproven, but there is an initial mass of believers (investors, customers, analysts) that has provided adequate support to get the company to believe in its direction. The critical success metric for these offers is the unit of future value. This is the item that the provider believes will be monetizable at scale. That item could be users buying subscriptions, but it could also be page views in an advertising model or transactions in a web services model. For one XaaS offer we analyzed, the unit of future value was the number of project plans under management on their platform. In the early days, FVAs are likely to be experimenting with revenue models; customer spending may be erratic or even nonexistent as the company endeavors to find the levers to add visitors and translate them into reliable revenue. FVA doesn’t necessarily mean that companies are not monetizing customers at all, it’s that they are in an immature—and likely unprofitable—state of monetization. The per-customer unit economics are likely to be negative or sub-optimal.

2. Mid-Term Wedge (MTW). These are XaaS providers that expect to achieve profitability in the not-too-distant future (3 to 5 years, or so) selling their core subscription. This is the most commonly advocated SaaS business model. These companies have, or believe they will amass, enough customers on the platform in this time frame to achieve the economies of scale required to be profitable. We refer to this as the mid-term wedge profile, because these are companies that are exiting the lefthand side of the classic XaaS financial curve, where the provider is investing in the platform, and entering the righthand side of the model, where each additional customer drives more and more revenue that brings the company one step closer to profitability. Importantly, the wedge model assumes that, at some point, costs are no longer increasing in a linear relationship to revenue. MTW is where companies start to hone in on their “balanced state.” Losses shrink and the economies of scale that are driven by positive per-customer unit economics begin to really become visible. The balanced state of growth + profits becomes clear and accurately projectable. It is the proof moment for the business model.

FIGURE 2.2 Profit Horizon: Future Value Aggregator

FIGURE 2.3 Profit Horizon: Mid-Term Wedge

3. Current Profit Maximizer (CPM). These are XaaS providers that are focused on maximizing the revenue and margin opportunity surrounding their XaaS offers as soon as possible. Instead of capturing market share at the expense of profitability, the companies are very focused on maximizing profitability per customer in the short term, this year or the next. Often these are large public companies with shareholders who are demanding profits now, or XaaS companies who are fairly mature and are ready to make the switch from revenue valuation multiples to profit growth valuation multiples. Most importantly, what both companies have in common is that they believe they can get their revenues to critical mass soon. Potentially this could be a new company with meteoric growth, but that usually requires a longer horizon than 1 to 3 years.

FIGURE 2.4 Profit Horizon: Current Profit Maximizer

So this leads us to the three profiles of XaaS, as summarized in Figure 2.5. These profiles are the first dimension of the 3x3 of XaaS.

Shareholder Appreciation Drivers for Each Profile

What profile is applicable to your XaaS offer? There are a few key attributes you can test for:

• Drivers for the Future Value Aggregator. This profile is applicable when there is a significant market—that may or may not be well understood by the marketplace itself—to create and/or dominate. The premise is that the XaaS offer with a dominant share of this large market will be best positioned to maximize future profits. However, to assume this profile, a company needs a critical mass of investors that drink the Kool-Aid and believe in the future payoff. If investors are not excited about the potential future state, then it is hard to raise capital to support the investments required to acquire customers. Over the past few years many venture investors have been placing high valuations on unprofitable XaaS providers with the hope that over a long horizon profits will flow.

• Drivers for the Mid-Term Wedge. This profile is applicable when the company believes it has a 3- to 5-year line of sight to making the current offer profitable. The company believes it can manage the three attributes that kill the profitability of XaaS offers: churn, costs, and commoditization. The company can keep the majority of customers on the platform for multiple years. Economies of scale are kicking in so it costs less to serve each customer. The company will be able to fend off commoditized pricing due to hyper-competition. It knows how many customers are required to cross the line to profitability.

• Drivers for the Current Profit Maximizer. This profile is applicable when a company needs or expects to generate high profits in the near term to meet shareholder approval. As just mentioned, the two common classic examples would be a highly profitable, publicly traded software company that is now in the process of starting up a new XaaS offering that competes with the legacy license offering, or a mature XaaS company that is ready to show off its ability to throw off profits and cash. Occasionally there may even be a highly disruptive and high-priced entrant that is confident it can get to profitability early in its XaaS childhood. In the first case, investors are accustomed to substantial profits from the company and may not have much appetite for significant losses related to a new XaaS offer. In the second example, investors are salivating at finally reaping the rewards of the multiyear investment to get the subscription business model to become a money-making machine.

FIGURE 2.5 The Three Profiles of XaaS

Common Behaviors

When companies assume one of these profiles, recognizable behaviors emerge:

• Common Behaviors of the Future Vaule Aggregator. Companies in this profile care more about attracting new potential customers than anything else and are willing to do whatever it takes to make that happen—almost no matter what that costs. They will offer “all in,” simplified pricing models, up to and including free and freemium. They will throw in services required to enable the customer at no cost, not focus on monetizing value-added services. Sales and marketing expenses will range from 50% to over 500% of total company revenues as the company aggressively invests to acquire new customers, add units of future value, and increase market share.

• Common Behaviors of the Mid-Term Wedge. Companies in this profile have clear signals that their revenue model and product-market fit are valid. Subscription or transaction revenues are consistently trending up each quarter. Cost of goods sold (COGSs) as a percentage of revenue might be beginning to shrink as economies of scale kick in. Sales and marketing expenses might also be shrinking as a percentage of revenue. B2B companies in this profile are often in the early stages of monetizing premium account services around the core subscription. These services typically represent 2% to 10% of total company revenues at this stage. The company has realistic models that indicate positive cash flow, and even GAAP profits, as it passes through the wedge inflection point in the next 3 to 5 years.

• Common Behaviors of the Current Profit Maximizer. Companies in this profile either have, or quickly will have, a critical mass of revenue enabling them to pass the wedge inflection point within 1 to 2 years. They are typically exhibiting slower top-line growth than the other two profiles, but are forecasting positive operating income in this fiscal year or the next. From that point forward, their models indicate strong and predictable cash flow and profit increases. If you look at their websites, you will typically see a diverse listing of multiple product and service offerings customers can purchase for additional fees. These companies may offer multiple consumption models. They may also offer to run the technology operations as a managed service.

3x3 of XaaS: The Second Dimension

Once you identify which XaaS profile you would like to pursue, you will need to answer the following three questions:

1. What is the offer portfolio and pricing model?

2. What is the customer engagement model that we will use to sell and deliver this offer?

3. What are the financial keys that will allow us to make money with this offer?

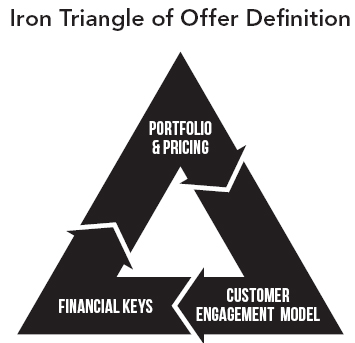

We refer to this as the iron triangle of offer definition, as seen in Figure 2.6.

A key premise of this book can now be stated:The profit horizon of the XaaS offer should drive how a provider engineers the financial model, designs the portfolio, sets the pricing, and matures the customer engagement model for the offer .While we will cover all three elements in later chapters, here is a bit more elaboration to help clarify the focus of our 3x3 matrix.

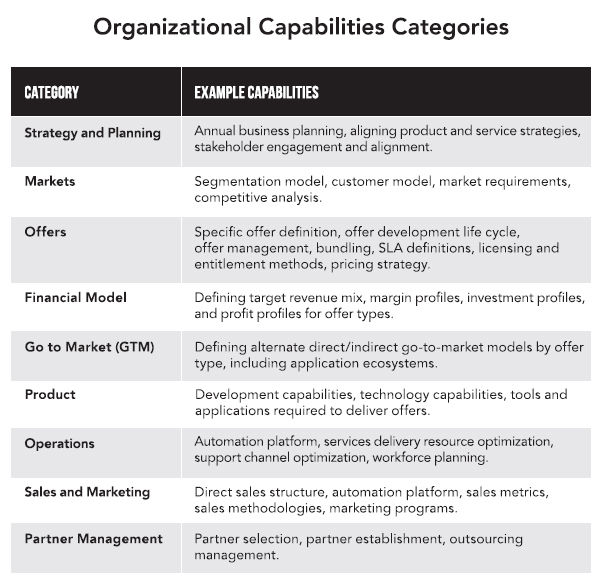

Portfolio and Pricing

Obviously, a company must determine exactly what it intends to take to market. The company needs to clearly define the XaaS offer and how it should be priced. Double-clicking into this area, the company must make decisions in the following areas:

• Technology Offer Definition. What form will the core offer take? How will you package the high-value capabilities? What is the differentiation of these offers from competitive alternatives? Will you have a single offer or multiple, complimentary offers inside a portfolio?

• Value-Added Services Offer Definition. Are there any additional services the customer may need in order to be successful with the technology? Services could include traditional customer or technical services as well as information/ analytic-based services.

• Offer Pricing Model. How will the offer be priced? Will the price be based on consumption of specific features, number of users, business outcomes, or other factors? Will required services be bundled or sold separately? How will these services be priced?

FIGURE 2.6 The Iron Triangle of Offer Definition

As discussed in the opening chapter, the answer to these portfolio and pricing questions are wide and varied in the marketplace today. Understanding what answers maximize success within each XaaS profile becomes key.

Customer Engagement Model

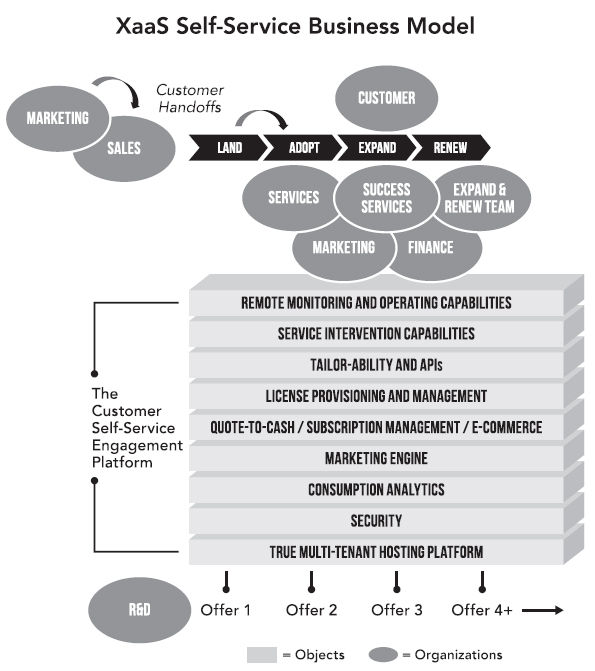

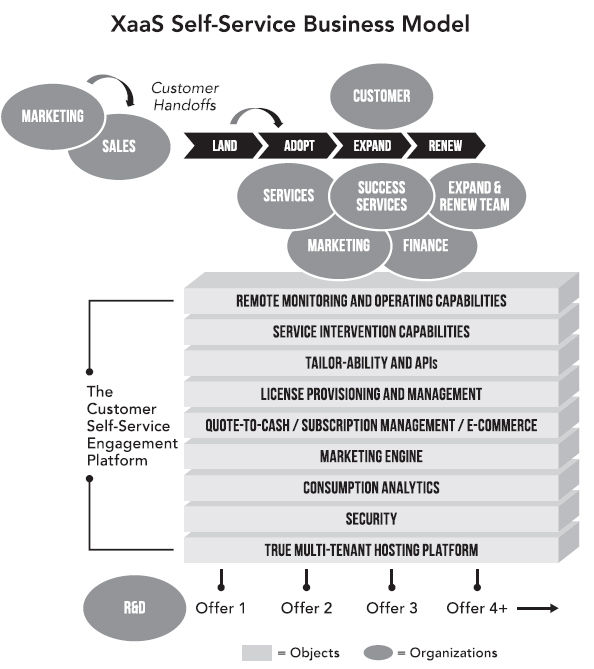

Next, a company must work through the appropriate customer engagement model for the XaaS offer. We break the customer engagement model into four distinct phases we call LAER (pronounced layer) :

• Land. All the sales and marketing activities required to land the first sale of a solution to a new customer, and the initial implementation of that solution.

• Adopt. All the activities involved in making sure the customer is successfully adopting and expanding their use of the solution.

• Expand. All the activities required to cost-effectively help current customers expand their spending as usage increases, including both cross-selling and upselling.

• Renew. All the activities required to ensure the customer renews their contract(s).

Customer engagement models for XaaS offers are highly diverse in the industry today. There is often particular confusion and conflict around the involvement of the channel. Many traditionally channel-focused tech companies find themselves in the awkward position of bringing out new XaaS offers that allow customers to engage directly. This channel conflict is particularly hard to avoid in many cloud XaaS models because customers often can completely self-serve from the company’s website. Partners, particularly those who sell to small and medium business (SMB) customers, find that some customers do not need to engage with them directly.

So far, many of the engagement models companies have deployed are poorly aligned with the profit horizon of the offer, often resulting in offer failure or financial failure due to intolerable levels of sales and marketing expense. One objective of this book is to help companies reduce the probability for these misalignments.

Financial Keys

When working through the financial keys, a provider is creating the parameters for how success will be measured for this XaaS offer. And as indicated in the 3x3 model, success is not always defined by profitability. But in any model, the main areas a company must discuss when setting the financial keys for their XaaS offer include:

• Revenue Mix. What percentage of total company revenue will come from the core technology subscription(s), and what percentage of revenue will come from other valueadded services you intend to monetize with the customer? We often refer to this as setting the “economic engine” of the offer.

• Margin and Profit Targets. What are the gross margin expectations for each revenue stream we have identified? What is the profitability we expect from the overall economic engine associated with this XaaS offer?

• Sales and Marketing Costs. What will the cost of our LAER model be as a percentage of revenue? How do we project that these costs ratios will change over time as our profit horizon shrinks?

• Key Performance Metrics. What are the specific metrics we will monitor to determine if we are on track to meet our financial objectives? Some of these metrics may not be financially oriented but can predict our ability to achieve our financial objectives in the appropriate time horizon as selected in the 3x3 model.

Once again, how a company answers these questions will be very different based on the XaaS profile it is pursuing. Figure 2.7. summarizes a view of the 3x3 of XaaS that provides an outline of the critical conversations a management team must have when defining a XaaS offer.

FIGURE 2.7 The Basic 3x3 of XaaS

Friction Curves

We have one final but critical thought before we continue the journey through the technology-as-a-service playbook. As you work through all the decisions associated with your XaaS offer, you will be optimizing between one of two extremes (Figure 2.8. ). At one extreme, you are doing everything possible to make it easy for the marketplace to acquire and adopt your core XaaS offer. On the other extreme, you are—at some point—doing everything possible to maximize the profits you extract from the offer.

On the left side of the diagram, you want to minimize any possible friction that prevents your units of future value from being acquired. That might mean free use of the product for a period, free services, and so forth. On the right side, you may be presenting concepts in your offers that add friction to the buying decisions but have the potential to increase per-customer revenue and profits. Maybe you are charging a premium price. Maybe you have a big professional services price tag to get the offer implemented correctly and you want to make money at that service. Maybe you have broken the offer into several separately priced modules that have the potential to increase total customer spend if the customer selects two or more. In any case, friction is a critical concept in the XaaS playbook. Most importantly, your friction strategy can and should change over time as your priorities, and your offer, mature. So let us introduce you to a model that TSIA calls the friction curve:

Friction Curve : The amount of offer complexity that balances the ease of customer purchase decisions with optimal per-customer economics.

FIGURE 2.8 XaaS Offer Extremes

Every parameter you set regarding your XaaS offer will move the offer up or down the friction curve, as seen in Figure 2.9.

There are friction curves related to offer definition, pricing, and so on. We will refer to the concept of friction throughout the book. Understanding your profit horizon objective helps you understand how much friction to insert into your portfolio.

FIGURE 2.9 The Friction Curve

Now we know that there are a lot of people in the XaaS industry who might fundamentally disagree with this premise. They argue that the best way to profitability is to make it quick, easy, and fun for new customers to enjoy the offer. The idea is to get as many as you can as fast as you can. Eventually you will have enough to make money. In a perfect world you could find a highly profitable, frictionless offer model. If you can, good for you! They do exist and that could be your goal. But we think that is also the path to commoditization. Our observation is that most of the more profitable technology offers also force customers through some amount of complexity and trade-off as they choose from among multiple, sometimes premium-priced offers within a provider’s portfolio of products and services. You may be faced with this reality as you make your playbook decisions. Again, we think friction is best thought of according to your profit horizon. You may start off with a low friction model when you are an FVA but intentionally place more and more expensive choices in front of your customers as you evolve into a MTW and CPM player.

So now let’s put together all the elements of the 3x3 of XaaS, shown in Figure 2.10.

FIGURE 2.10 The 3x3 of XaaS

Upcoming Chapters

In Chapter 3 , we will discuss how to create a XaaS offer that has the potential to create the highest and most sustainable profits possible by combatting the three “killer Cs” of XaaS success: customer churn , high costs , and offer commoditization . This is an important concept because many XaaS offers are creating a race to the bottom in terms of pricing and profitability. Chapter 4 tries to sort out how profitable XaaS businesses might eventually organize and operate differently than traditional tech companies. Chapter 5 is targeted at all those large, legacy technology companies that are struggling to pivot from traditional technology offers to new XaaS offers. In Chapters 6 through 8 we will explore the three elements of the iron triangle of offer definition in more detail. Chapter 6 will explore the power of portfolio in XaaS. We will provide frameworks for defining your XaaS offer and setting the pricing strategy. Chapter 7 will cover the LAER customer engagement model and why the concept and science of customer adoption is the best strategy for battling the three killer Cs. Chapter 8 explores the specifics of setting target financial models and metrics for a XaaS offer. Chapter 9 looks at the special case of managed services as entrée into XaaS. Chapter 10 will explore the changing channel models—how the role and success factors of go-to-market partners can alter in XaaS marketplaces.

Playbook Summary

This book is designed to provide a set of plays you can run to move your XaaS business forward. At the end of each chapter, we will provide a summary of the plays that have been defined in the chapter. As of now, you need only make one simple decision and you will have run the first play in your XaaS playbook.

Play : Setting the Profit Horizon

Objective : Align your entire management team on what profit horizon the company is pursuing for this XaaS offer.

Benefits:

• Provides context for the wide variance in behaviors of XaaS providers in the marketplace.

• Identifies the right XaaS offers to compare yourself against and model yourself after.

• Identifies the key parameters the management team will need to set for the XaaS offer.

• Minimizes behavior schizophrenia when setting the parameters for the XaaS offer.

Players (who runs this play?) :The executive management team runs this play and should include senior leadership from the areas of product development, marketing, sales, services, and finance.

3Digging an Economic Moat for Your XaaS Business

As we just discussed, all kinds of companies are creating XaaS offers these days. Regardless of the profit horizon for your XaaS offer, at some point in time the offer will need to become profitable. It will need to generate more revenue than it costs to sell and deliver. Unless you are a market anomaly like Amazon, 1 that is just a basic business reality. But what level of profitability would you consider a success? If your XaaS offer generated an operating income percentage of 10%, would you declare financial victory? Would less than 10% be acceptable? Boards and chief financial officers (CFOs) love to set firm, and often aggressive, profitability objectives. But just because the board of directors wants a XaaS offer to generate a certain level of profit, it does not mean the offer (or the company) will ever achieve that level of profit. Why not? The answer can be found in the concept of economic moats. But before we introduce that framework, let’s review the historical profitability levels of technology companies.

The Tech Cash Cow

In Chapter 1 , we introduced the data in Figure 3.1. that demonstrates how profitable even the average large technology companies have been. The average profitability of the TSIA Technology & Services 50 (T&S 50) index of companies is superior to large-cap icons like General Electric (GE) or Exxon Mobile.

FIGURE 3.1 Operating Profit Comparisons

To provide additional context, Figure 3.2. tracks the net operating incomes of leading technology companies through the Great Recession of 2007–2009 compared to some other wellknown companies. Although General Motors (GM), General Electric (GE), and Exxon all experienced significant dips in their operating incomes in 2009, Cisco, EMC, and Oracle exhibited little pressure on their profitability.

Figure 3.2 also highlights a strike zone where we are picking operating incomes: a range from above 5% to 15%. This is a healthy range of profitability by most standards. Accenture, GE, and Exxon are operating comfortably within this range, year after year. EMC runs at the high end of the range. A few exceptional performers like Cisco and Oracle (and some other technology companies) have been operating beyond the range.

FIGURE 3.2 Operating Income Comparisons

But we are choosing 5% to 15% as a reasonable initial profit target for a XaaS offer. A big basket of hardware and software companies have been operating in this reasonable profitability range—undisturbed—for quite a long time, so we know it’s a number that the financial markets will accept. Although some companies may be able to do even better, let’s set some modest sights and start there. Let’s get our XaaS offer to a 5% to 15% GAAP profit by working together; then, you can feel free to take it to new heights from there.

So how do we do that? Well, first we set our profit horizon as was done in Chapter 2 . Now we need to figure out what strategies we can build into our offers that will be the foundation of our eventual 5% to 15% GAAP profit. Let’s approach that task by looking at the lessons of the tech industry so far. Why were large technology companies like Oracle, EMC, and Cisco so incredibly profitable, even through the difficult 2008–2009 recession? Our answers can be found by applying a framework leveraged by several sophisticated investors.

Economic Moats

The investment firm Morningstar coined the term “economic moat” to describe how some companies are able to consistently generate above-average profits. Here is how Morningstar describes the concept:

“The idea of an economic moat refers to how likely a company is to keep competitors at bay for an extended period.” 2

However, Morningstar is not the only investing entity that embraces this concept:

“In business, I look for economic castles protected by unbreachable ‘moats.’” 3 —Warren Buffett

Buffett and others are searching for companies that have a unique ability to generate highly profitable revenue. But how can you tell if a company has developed an economic moat that other competitors will find difficult to breach in the short term? Combining the insights of multiple publications on the topic of economic moats, we would like to proffer six attributes that will help determine if a XaaS offer can generate strong and consistent profitability. These attributes will be introduced from our view of least important to most important.

#6 Attribute: Virality and Other Paths to a Low-Cost Sales Model

Virality is the concept that a company has a product or service that almost sells itself. There is organic demand for the product. Word of mouth and reputation drive sales as opposed to heavy spending on sales and marketing. Think of the old Vidal Sassoon commercial:“And they told two friends, and so on and so on.” 4 Low sales costs mean the company has an offering customers are excited about, and it usually means that more money drops to the bottom line. Virality is just one path to a low-cost sales model. We will discuss other paths later in the book.

A XaaS example of virality and a low-cost sales model is mobile ride-hail company, Uber.

#5 Attribute: Diverse Revenue Streams

Most consistently profitable companies have been able to diversify their revenue through multiple offers. The existence of several revenue streams in a portfolio allows them to better weather a difficult period or intense margin pressure faced by any one offer. As an example, during the 2008–2009 recession, large tech companies faced huge pressure on new product sales revenue as customer uncertainty brought IT purchases to a virtual standstill. Fortunately, these same companies had also built strong revenue streams for both their maintenance/support and professional services businesses. Because customers were not adding new products, they relied more heavily on maintaining and increasing the productivity of the products they already owned. For many profitable tech companies, maintenance renewal rates actually increased during this period. In addition, many customers contracted for professional services to help them better leverage existing systems to the new business realities they faced. The fact that these tech suppliers had a diverse portfolio of products and services enabled them to cushion the blow to the top line and achieve continued profitability on the bottom line. Perhaps even more important, diverse product or service revenue streams give you more ways to make money. Hewlett-Packard (HP) never made much money on printers, but they did pretty darn well on ink. Diverse revenue streams are usually a win-win. They are not only good for the provider, but they also usually mean that the customer has an array of products and services that provides a more complete solution. They don’t need to shop multiple providers, and they have one throat to choke.

A good example of a XaaS company with diverse revenue streams is Veeva Systems. The company currently has over 20% of total company revenues coming from value-added services wrapped around the core product subscription. The company, unlike many similarly sized SaaS companies, is generating an operating income of almost 10%.

#4 Attribute: Network Effect

Another economic moat similar to virality is the concept of a network effect. This is the phenomenon whereby a good or service becomes more valuable when more people use it. Telephone service is a great historical example. The more people who got phones in the late 19th and early 20th century, the more valuable it was to have a phone. If a company has an offering that is valuable because many people are using the same product, then the marketplace is incented to stay with that offer. This is not the same as market share. One company may dominate the market in mittens, but that does not benefit consumers in any special way when they buy a pair of mittens. However, if a person uses the TripAdvisor website to research travel decisions, that person benefits if more and more people are using the site and posting helpful reviews. The network effect can also be achieved by becoming a technology standard, building your brand into a standard, or by having uniquely broad compatibility with a surrounding ecosystem of products from other providers. If there is a vast network of complimentary products that easily interact with it to form a more complete and robust solution for the customer, your XaaS offer can achieve this effect.

Good XaaS examples of the network effect include LinkedIn and Salesforce’s Force. com and AppExchange platforms.

#3 Attribute: Economies of Scale

A powerful economic moat for your XaaS offer can be dug when economies of scale play a significant role. This gives a company the power to have either higher profitability than a competitor or choose to use lower prices as a competitive advantage. If a company has an offer where increasing volumes equate to higher unit margins (often called “subtractive manufacturing”), then companies with critical mass and market share are in the pole position to extract high margins. Think of Intel in the computer processer marketplace. Because cloud-based XaaS offers are almost always based on multi-tenant architectures, where each incremental tenant reduces the providers’ average hosting cost per tenant, you get subtractive manufacturing economics.

In infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) markets today, we see Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft Azure beginning to leverage their massive scale to apply price pressure to smaller rivals like Rackspace.

#2 Attribute: Unique Capabilities

Of course, something powerful must be said for having a truly unique capability. If a company can do something few others can do, then that company is in a position to create higherthan- average profits. Unique capabilities can be created through patents, specialized expertise, or even geographic presence. Also, brand equity built up over time can be viewed as a unique capability. Why is this only number two on our list of economic moats? It’s because this moat seems to be getting narrower and shallower in the cloud. The cost and time to build or replicate features is rapidly shrinking. One XaaS offer’s unique functionality is soon commoditized as all of its competitors quickly catch up—sometimes with an even better version than the original. In addition, recent trends in patent law are making it even more difficult to secure and defend software patents. All these add up to a markedly different outlook for the decades-old tech strategy of betting the whole company on the sole strategy of having perennially differentiated features.

A great XaaS example of unique capability is Google, whose search algorithms and ad placement software are both highly proprietary and highly effective.

#1 Attribute: High Switching Costs

The traditional trump card in creating highly profitable tech revenue has been high switching costs for customers. If it is expensive or painful for customers to switch to a competitive offer or substitute, then a company is in the perfect position to extract maximum profitability from the customer. When we present this model to MBA students, they are often incredulous that this is our number one attribute. They can’t believe customers would fall for this in the long term—especially sophisticated buyers in businessto-business (B2B) markets! Yet, there are many ways to create high switching costs for customers that include:

• Requiring a large capital up-front investment that creates a sunk investment the customer will not readily abandon.

• Technically, making it difficult for customers to migrate all their data off of your offer.

• Contractually, making it financially painful to switch.

• Requiring a large training investment that makes it painful to retrain employees on substitutes and cause a protracted negative impact on productivity.

• Embedding your capabilities within the customer’s business processes so your offer becomes critical to the customer’s success.

Many SaaS application companies still benefit from high switching costs in much the way their on-premise predecessors did.

Companies like Salesforce and Workday are good examples of XaaS offers with high switching costs.

In summary, a company can generate highly profitable revenue when some or all of these attributes are present in their offers:

• Costs of selling the offer are low.

• The company has a diverse stream of revenues that surround the core offer, which helps balance out revenue or margin pressure in any one stream.

• The more customers that buy the offer, the more valuable the offer becomes to all customers.

• The more of the offer the company delivers, the lower the cost per customer becomes.

• The offer delivers a unique capability or experience to the customer that they cannot get elsewhere.

• It is very painful for customers to switch from the offer once they have decided to purchase it.

Next, let’s review how the traditional technology industry has done on building deep economic moats around its offers. This is an important exercise because, as we will later see, not only the traditionally profitable tech companies but also the XaaS companies that are highly profitable today are both leveraging multiple economic moats. Quite simply, the more economic moats you can dig, the more successful and profitable your XaaS offer is likely to be!

Economic Moats in Traditional Technology Product Markets

#6 Attribute: Virality and Other Paths to a Low-Cost Sales Model

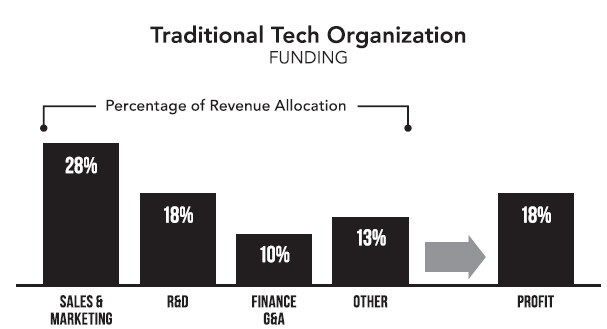

Companies in the T&S 50 index spend an average of 22% of revenues on sales and marketing—not exactly a small number. Software companies spend an average of 29%. Accenture, with all of its advertising and direct sales costs, spends 11% to 12% of revenues on sales and marketing. Ford Motor Company spends 10% to 11% on selling expenses. So in comparison, low cost of sales has not necessarily been a strength of the traditional hightech business model.

Score: LOW

#5 Attribute: Diverse Revenue Streams

In addition to the diverse revenues emanating from their famously enormous and complex product portfolios, most large tech companies also have large and diverse service portfolios. On a combined basis, the companies in the T&S 50 index now have more than 50% of their total combined company revenues coming from services. Over the past five years, their collective product revenues—even with their diverse product portfolios— have declined 35%, and most hardware products have also suffered substantial margin erosion. But by diversifying into services that are growing at between 2% and 35% compound annual growth rate (CAGR)—many of which often have margins far superior to the products they are sold with—traditional tech companies have been able to better withstand the myriad pressures on their core offers and continue to deliver earnings per share (EPS) growth over time. So the traditional technology industry has done an excellent job of having diversity across both products and services.

Score: HIGH

#4 Attribute: Network Effect

Performance here has been a mixed bag among traditional tech companies. A few, like Microsoft Windows, have taken advantage of their vast network of users to build their products into true technology standards. A handful of others have built their company brand into a “safe choice,” like IBM or Cisco, or a social fad, like Apple. Some have even used the network effect by achieving a broad base of IT workers who were familiar with the products. This was good news for any customer who wanted to operate their technology. Some traditional high-tech companies benefited enormously from the network effect. But rarely were they able to leverage the most powerful of the network effects where each new customer they sold added to the value being received by the base of existing customers. Many of them did, however, take advantage of the vast community of third-party resellers who could make money by reselling products and delivering attached services. The greater the demand the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) could create, the more partners flocked to resell the product. The more partners that did that, the more successful the brands became, and the more other partners felt the need to follow suit. In this instance of the network effect, the traditional tech industry was successful.

Score: MEDIUM

#3 Attribute: Economies of Scale

Clearly, economies of scale apply to technology products. We already mentioned Intel, which has made massive investments in plants to build processors. That has allowed the company to maintain roughly 80% of the processer marketplace decade after decade. But those economies have not created widespread competitive advantage for most hardware companies. Only a few have been able to use price to sustained benefit or enjoy product margins substantially better than their competitors.

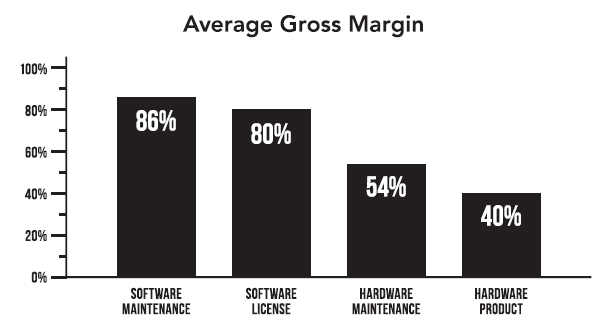

In perhaps the industry’s best example of how to make use of economies of scale, companies like IBM and Oracle have built vast piles of customer support and maintenance customers who pay to access a single technology service infrastructure. Once that structure was built, the incremental cost of supporting one more customer on the platform was negligible. Over time, as customer after customer was added and renewed, these maintenance empires became huge and incredibly profitable. Figure 3.3. reports on the product and support margins we track in our industry benchmarks and demonstrates how powerfully the economies of scale in the software support and maintenance business have led to gross margin that can exceed software itself!

Score: MEDIUM

FIGURE 3.3 Margin Profiles for Technology as a Product

#2 Attribute: Unique Capabilities

Technology companies have spent the last 40 years positioning around the unique technical capabilities of their products. These feature wars have resulted in a mind-boggling number of features per product. Microsoft Word alone has more than 1,200 features a user can access. Competing on differentiated technical capabilities has been the hallmark of high-tech strategy. Technology sales reps are trained to compete on “speeds and feeds” or software features. This has worked consistently and pervasively.

Score: HIGH

#1 Attribute: High Switching Costs

But as we have mentioned, the trump card of the technologyas-a-product business model, especially for software companies, was high switching costs. Technology companies pulled nearly every lever to make sure customers could not easily switch off a technology product. That meant that all downstream purchases by that customer would not be truly competitive situations. Solid revenues at solid margins could be counted on. Revenue from the existing customer base became the economic engine that propelled the company and its stock. It has been a beautiful thing.

Score: HIGH

Putting these observations together, we can rate how well traditional product revenue streams align with the attributes of high profit revenue, and seen in Figure 3.4.

As shown, these economic moats were medium or strong in every attribute but low cost of sales. There are many reasons why technology companies have been generating so much profit. Both their product and product-attached service revenue streams contain attributes that create deep economic moats.

So how are these attributes carrying forward to the world of technology as a service? How well are current XaaS offers faring in their ability to create deep economic moats that unlock the same type of highly profitable revenue? Let’s take a look.

FIGURE 3.4 Economic Moat – Traditional Tech Alignment

Shallow Moats of XaaS 1.0

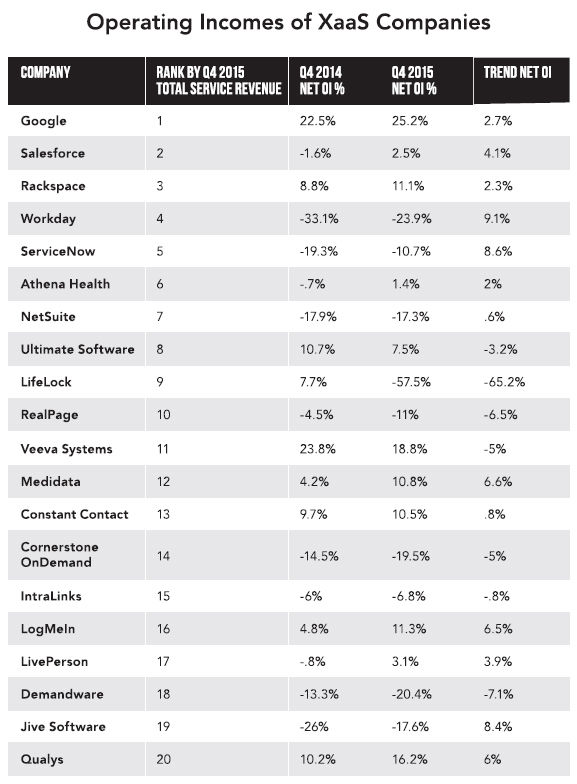

The 20 publicly traded XaaS companies we track in our Cloud 20 index have been growing top-line revenues at double-digit rates. Revenue is clearly flowing nicely into these offers. GAAP profitability, on the other hand, has been extremely elusive for most, as shown in Figure 3.5. The average net operating GAAP income for these companies is –3.32%, and only 8 out of 20 made a net operating profit greater than 5%.

FIGURE 3.5 Operating Incomes of XaaS Companies

In addition, there is no consistent trend of improved margins and profitability year to year. Some companies are improving while others are not.

Now, perhaps a majority of XaaS companies in the public domain would still consider themselves to be future value aggregators or mid-term wedge companies. They may be building new markets or chasing market share and be less concerned with profitability. That could indeed be the case. However, the inability of so many XaaS companies to be profitable can be disconcerting, especially if you are a traditional tech company trying to decide whether you should take the plunge into subscription business models. This is of particular concern because many of these companies have annual revenues well in excess of $500 million—far past the point where most traditional tech companies turn profitable. Our point of view is that many of the first-generation XaaS companies are suffering from shallow economic moats.

So, let’s now apply our economic moat framework to this current generation of XaaS offers (we’ll call them “XaaS 1.0”).

#6 Attribute: Virality and Other Paths to a Low-Cost Sales Model

As seen in Figure 3.6 , SaaS companies in the TSIA Cloud 20 index spend an average of 40% of revenues on sales and marketing— much higher than their traditional license software peers (which is yet higher than many other industries).

What is driving this incredible spending? Acquiring new customers is clearly the main culprit. These XaaS companies need new customers to feed their models, and the sales cost to acquire a new customer almost always is more than the initial revenue received from them. Ironically, the more successful you are at adding new customers in a particular period, the worse your sales and marketing costs might be. It’s almost like negative leverage. If it costs $10,000 to add a new customer but they are only going to spend $10,000 in the first quarter, you have just added revenue at a high cost of sales for that year. Do that hundreds of times and it’s easy to see how sales and marketing costs in a XaaS world can skyrocket. But there is even more to the story here. In Chapter 7 we will introduce a framework on the XaaS revenue waterfall. That framework clearly demonstrates that if churn and down-selling are problems, it will take even more new customers to feed the beast of revenue growth because of the erosive effects of lost customer spending. Replacing lost revenue means that you need to land a certain number of new customers just to stay flat. If that void is too big and new customer sales costs to fill it are high, the XaaS company is destined to be unprofitable. And, the lack of cost-effective models to expand existing customer accounts can also cause sales expenses to soar. Having expensive field sales resources doing small upsell or renewal deals is simply not smart. It is our point of view that the selling models in these XaaS 1.0 business models have not yet been truly optimized. For most XaaS companies, cost-effective LAER coverage models have not yet been implemented at scale.

Score: LOW

FIGURE 3.6 Sales and Marketing as a Percentage of Revenue

#5 Attribute: Diverse Revenue Streams

This is an area of particular weakness for most XaaS companies or offers. Because these offers are often measured solely by the number of new users or some other unit-based metric, there is a massive temptation to eliminate any friction in the customer’s selection process. That means throwing everything into the bundle at one low price—no separately monetized services or chunking of certain features into separate offers. Although we can understand that logic, we also think many companies will rue the day that the “eliminate all friction” mentality took root. Once an offer has established its value in the market, it is time to start building adjacent offers and diversifying the revenue streams associated with the core offer. Rainy days do come. New price-cutting competitors do emerge. Having a diversified revenue stream has proven again and again in the history of the tech industry to be a smart thing to do.

Score: LOW

#4 Attribute: Network Effect

Some XaaS companies have done an extraordinary job of leveraging the network effect. As we mentioned, companies like LinkedIn, TripAdvisor, Yelp, and Airbnb have built their entire business models on the network effect. But consumer XaaS companies are not alone. Salesforce’s Force. com platform is a fantastic example of the network effect. The fact that a customer who chooses Salesforce knows there is a vast array of prequalified and highly compatible add-on applications is a mighty advantage for Salesforce. The more B2B XaaS providers that choose the Force. com platform, the stronger the advantage that Salesforce has over its customer relationship management (CRM) rivals. But not enough companies have built this moat into their strategy.

Score: MEDIUM

#3 Attribute: Economies of Scale

In theory, XaaS companies should absolutely benefit from economies of scale. Adding more users on the same platform should result in higher profits over time. Unfortunately, as we will discuss further in Chapter 7 , the majority of XaaS companies that TSIA tracks are not exhibiting proof that scale automatically equates to higher profitability. Many of the SaaS companies TSIA tracks are becoming less profitable as they grow in revenue. Although these companies experience incredible top-line growth, their operating incomes remain in negative territory.

Now, we do believe economies of scale should be a positive attribute for XaaS revenue streams. Cost of goods sold (COGS) and general and administrative expense (G&A), in particular, should benefit. However, the economies are not yet consistently presenting themselves—even for multibillion-dollar SaaS companies. Without clear data to support this attribute of high-margin revenue, we cannot yet assume it is a given for XaaS offers.

Score: LOW

#2 Attribute: Unique Capabilities

As we will highlight in Chapter 4 , XaaS providers are finding it harder to compete on features and are being forced to compete on price. For example, Microsoft, Amazon, and Google have been engaged in an aggressive price war related to hosted web services. The ability to differentiate their offers based on features has been challenging as the cost and time to develop new features become less and less. However, there continues to be evidence that features can determine market share, as SaaS start-ups quickly put competitive best-of-breed features on the table.

This moat works sometimes, but usually not for long. For example, have longtime competitive companies like Cisco WebEx, Citrix, and Skype been able to use unique product capabilities to win market dominance and avoid price commoditization? Not really. Many XaaS 1.0 offers have competitors that match one another on all the key features that define the category. So, unique capabilities are good when you can get them. But we see it as being a riskier and riskier strategy on which to base your entire business strategy.

Score: MEDIUM

#1 Attribute: High Switching Costs

How does the trump card of the technology-as-a-product business model relate to XaaS? In a recent study on customer success organizations, respondents from SaaS companies that were heavily focusing on customer adoption reported fighting average customer churn rates close to 20%.The TSIA benchmark tracking SaaS providers, in general, reports average customer churn rates of 8.4%.

The challenge for many XaaS providers is that an “easy on” XaaS offer can also be an “easy off” one. Many business customers of XaaS offerings are increasingly resistant to making massive up-front capital commitments or signing long-term agreements. If they dislike the offering after one year, they may indeed switch. In this regard, it is still true that the more complex your solution is to onboard, the stickier it is likely to be. Customers may resent a long and costly implementation, but from the supplier perspective it can be a powerful deterrent to attrition. So we still think high switching cost can be an important economic moat in XaaS, but like economies of scale, it seems to be present only in complex enterprise applications.

Score: MEDIUM

Putting these observations together, we can roughly rate how well XaaS revenue aligns with the economic moat attributes of high profit revenue.