8The Financial Keys of XaaS

8The Financial Keys of XaaS

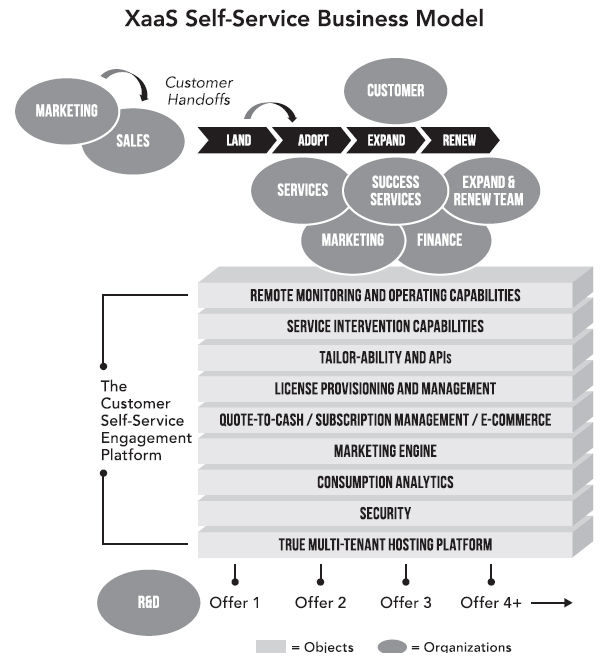

There is no doubt that XaaS offers can generate substantial revenue. After all, it was a proven business model long before the cloud came along. Just look at ADP, D& B, or your cellular service provider—companies that have offered technology as a service for decades. Today’s hot cloud companies are also racking up impressive revenue stats. Unlike the dot-com companies of the late 1990s that were virtually all FVAs, the revenues at companies like Salesforce and AWS are big and getting bigger. Figure 8.1. documents the incredible growth in combined top-line revenues for the 14 XaaS companies that have remained in our Cloud 20 index for more than 12 consecutive quarters with a CAGR of 26.6%.

These 14 companies have collectively doubled their revenues in just 3 years, but top-line growth is only one sign of financial success. Bottom-line profitability is the other. This is where XaaS providers have clearly struggled. In the Q4 2015 snapshot, publicly traded XaaS companies tracked in the Cloud 20 were generating an average operating income of –0.8%. Of the 20, 8 reported a loss. 1 In the same snapshot, Salesforce, which has now grown to more than $1.7 billion in quarterly revenues, barely cracked into profitability with a reported GAAP operating income of 2.5%. 2 In the following quarter, announced February 2016, management was predicting its first full-year GAAP break-even. CFO Mark Hawkins commented, “We are certainly excited about continuing on the path of raising profitability. And the top-line [revenue] is happening, too.”

FIGURE 8.1 Growth of XaaS Companies

It is interesting to contrast Salesforce’s financial trajectory with Oracle’s historical performance. In 1986, Oracle went public with $55 million in revenue. They were profitable that year. They grew revenues to more than $500 million in 4 years. They were profitable every quarter along the way. In the third quarter of 1990, they reported their first and only loss, and then quickly corrected and continued the trajectory of increased profitability over 2 decades. Today, they are generating an operating profit north of 35%. No enterprise application SaaS company can make a similar claim. Clearly, there is something different in the financial model.

Figure 8.2 compares the operating expenses of present-day SaaS companies in the TSIA Cloud 20 that have revenues over $500 million to the current cost structures and profit performance of the license software companies in the Technology & Services 50 (T& S 50).As can be seen, these larger SaaS companies are still not profitable on a GAAP basis, and the traditional license companies are exhibiting superior financial performance on all five key indicators. This could lead you to question the logic that SaaS grows into a profitable business model over time. What they do really well is grow revenues. What they do not do so well (so far) is throw off GAAP profits. That is the reality of the XaaS 1.0 financial model.

FIGURE 8.2 SaaS versus Software Business Models

As we have repeatedly pointed out, SaaS companies in the Cloud 20 are currently spending an astronomical average of 39% of revenues on sales and marketing. In fact, companies like Log-MeIn, Salesforce, and Vocus are all spending more than 50%.This percentage is much higher than the 28% of revenue being spent by license-based software companies on sales and marketing. It is perhaps the largest single cause of low GAAP profits for many SaaS companies.

So, why would any company want to pursue a financial model that can be so prone to losses? Let’s explore the pros and cons of XaaS economics.

On the upside, there are lots of things to love. Four reasons in particular jump to the top of the list:

• Customers like the consumption model.

• Investors are keen to reward the revenue growth potential.

• Recurring revenue is a beautiful thing.

• Free cash-flow generation can be very strong.

Let’s explore these four benefits of the XaaS economic model in a bit more detail.

From a customer perspective, there is no debate as to whether XaaS concepts like subscription/pay-for-use pricing and simpleto- consume technology have become permanent fixtures on the tech landscape. Both consumers and enterprise tech buyers— particularly buyers and users on the business side of enterprises (as opposed to the IT side)—LOVE these models. XaaS reduces their risks and speeds their results. They can start with small pilots and short-term commitments (monthly, annual, even NO commitment) and grow if and when they succeed. XaaS also allows them to side-step many of the perceived delays and hassles that are associated with large IT-driven projects. They can just sign up and start consuming. And, most importantly, there are some pretty cool XaaS technologies out there . . . some with features and benefits that can only be achieved in the cloud. So let’s not spend any time defending XaaS as a permanent alternative to buying technology assets. It is here to stay, and suppliers should learn to love it or risk losing customers.

The second reason that XaaS is a great place for providers to be right now has to do with the incredible valuations currently being bestowed on pure-play XaaS companies by the financial markets.

This part of the story can be frustrating if you are a traditional, asset-based company. That is because tech-stock valuations as of early 2016 are a tale of two formulas. Traditional tech-company stocks are still valued the old-fashioned way, as a multiple of GAAP earnings. But pure-play XaaS company stocks are being priced based on a multiple of revenues driven by the revenue growth rate.

It would have been hard to imagine just a decade ago, but many traditional tech stocks are anchored almost entirely by their profits, not their growth. This is especially true of consistently profitable, divided-yielding tech stocks like Microsoft, CA, Symantec, and Cisco. If these kinds of companies went through an extended period of deteriorating profit, their stock prices would be imperiled. It follows that the management of these businesses must focus each and every quarter on sustaining and growing profits. That’s the fish model problem we covered in Chapter 5 . Clearly, revenue growth remains very valuable to these companies but NOT at the expense of profits. They often know some growth levers they would like to pull—i. e., significant investments that could lead to more growth but result in lower profits during the investment period—but that trade-off is not one that many of their shareholders are willing to tolerate.

At least until recently, the executives who lead pure-play XaaS companies have found themselves in exactly the opposite situation. It seemed perfectly acceptable to the investors in these companies to not have any GAAP profits as long as they have a great revenue growth rate. For some companies, the measure of growth may not even be of actual revenue. As we have already covered in this book, some FVAs are free to discuss growth rates in terms that may have little or no current economic value, like users, downloads, or page views. Investors are betting that, at some point, those assets will be translated into economic value, but for right now, it is a game of capture, not monetize. This has been particularly true for consumer applications like Pandora or Twitter. But the phenomenon is not exclusive to them. Many B2B XaaS companies today will often lead their financial reviews with user growth statistics. For these companies, management decisions are often made with a different mind-set: Will this investment help our growth rates continue or accelerate? In early 2016, some financial analysts have criticized a few XaaS companies who keep extending their profit horizon or are reporting sales slowdowns. If this noise in the system increases, it will put more pressure on XaaS executives to prove their financial model sooner rather than later. But for now most are still free to pursue growth investments as long as the cash lasts.

Another case for higher sales and marketing spending by SaaS companies in particular can be made by arguing that these companies may have a larger total addressable market (TAM) than traditional companies. That’s because cloud-based solutions reduce the number of investments a corporate customer has to make (they don’t have to buy more hardware, they pay less for implementation services, and so forth—often things that they purchased from other vendors).That means budget dollars can be aggregated and focused on buying more of the XaaS provider’s offer. Also the XaaS company can tap into both IT and departmental budgets. It can derive revenue not only by charging for basic access to the offer but also for actual use. The more the customer uses, the more they pay. That is not the case with most traditional software products. Finally, depending on what the SaaS offer is, the provider may actually be able to expand their TAM by opening up entirely new cloud marketplaces that make users out of people or companies that never would have been able to access a traditional, on-premise software product. Just think about how Apple and Salesforce make money off their market platforms. Arguing that the XaaS TAM is larger helps support the notion that spending more to develop and access it makes sense. The logic is that the XaaS company can ultimately be larger than a traditional competitive counterpart.

So there are two different stock price formulas: one based on profit growth, and one based on revenue growth. The impact of this difference on the ways that these businesses are managed is huge. Traditional tech companies face the daunting challenge of swallowing the fish. What’s frustrating for many of them is that they actually have sizable XaaS businesses growing within their four walls, but they simply can’t get the markets to value them in the same way that they value the pure-play cloud stocks. That logic would give the management of these businesses a clear path forward. They could grow their SaaS businesses by reinvesting some of the profits from their traditional businesses. They could report them separately. The higher valuation of the SaaS revenues would more than offset the reduction in valuation due to lower profitability. The stock price would remain the same or higher during the transition. Both management and investors would have a straightforward and transparent way to transform the financial model for the XaaS epoch. This is part of the path we recommended in Chapter 5 , but we see very few companies doing it effectively.

It is safe to say that running a pure-play XaaS company today is a simpler task than transforming a traditional systems or software company. Investors support and reward their simple message: growth.

The third leg of the XaaS stool that everyone loves is its recurring revenue nature. XaaS is, after all, technology as a service , and services are typically purchased as subscriptions the same way cable TV or cellular service is. If you look at the financials of most enterprise XaaS companies, you see two wonderful things: one item on the balance sheet and another item off of it.

Though often priced “by the month,” most enterprise XaaS companies have adopted the practice of getting customers onto annual contracts that are billed and paid at the beginning of the contract period. The company then has a liability of actually delivering the service over the life of the contract. In accounting terms, this is known as deferred revenue —revenue that has been contracted for, billed, and even paid—but not yet delivered. This figure is recorded as a current liability on a XaaS balance sheet. This liability is balanced by the assets of accounts receivable or cash for these “pre-billed” services. The beauty of deferred revenue is that it is already committed and paid up front. The XaaS company doesn’t have to worry about building revenue from zero each month. It has revenue that is already committed, billed, and prepaid. All they have to do is deliver it. That’s great.

A second item that is frequently reported by XaaS companies but not carried on the balance sheet is something called “unbilled deferred revenue.” Unbilled deferred revenue represents business that is contracted but unbilled and off the balance sheet, meaning that customers are contractually committed to subscribe to the services for future periods. This is true for enterprise XaaS companies like Salesforce and wireless carriers like AT& T. Enterprise XaaS companies will often grant price incentives for their customers to sign multiyear contracts. That means a customer will commit to use the service at a particular minimum volume level for 2- or 3-year periods. In return for that commitment, they will pay a price that is more favorable than similar customers who only sign monthly or annual agreements. In this case, the XaaS company bills in advance for each year of the contract period on the anniversary date of the contract. The first year’s revenue is treated as deferred revenue and placed on the balance sheet as described earlier. The future years are tracked as unbilled, deferred revenue but not placed on the balance sheet until they are actually billed.

Why is all of this so important? First of all, deferred and unbilled deferred revenues give visibility and confidence to a company’s future financial performance. When Salesforce finished its 2015 fiscal year, it reported $5.4 billion in revenue. It also reported deferred revenue of $3.2 billion and unbilled deferred revenue of $5.7 billion. That means as the company entered its fiscal year 2016 period, it had guaranteed revenue of more than 60% of its previous year. To grow, it just needs to add another 40% from new bookings and non-committed renewals. Anything over that number will represent true incremental growth. So, management and analysts gain confidence that Salesforce will grow strong again, not only this year, where there is a committed revenue baseline of $3.2 billion, but also for the next couple of years, where there are committed customer revenues of another $5.7 billion for the company to draw from. This is supplemented in the XaaS model by highly likely renewals. Even when there are no committed future bookings, high renewal rates assure investors that future revenue growth is extremely likely. Combining committed and uncommitted renewals, companies like Salesforce and Netflix can head into a future year with the confidence that they just need to build on the 85% to 90% of recurring revenue from last year to achieve real growth. It’s a heck of a lot easier than starting over from scratch every year! Very powerful!

Recurring revenues offer an enticing allure of high profits. The magic occurs when a company’s recurring revenue base grows at a faster rate than its recurring expense base. It’s the wedge model we described in Chapter 2 . Hit that inflection point, and XaaS businesses should turn into money-making machines, because the incremental unit economics are very favorable. If XaaS management can achieve this state, then they can deliver both high-confidence revenue and high-confidence profits. Everyone is on the lookout for that point—both investors and management.

The other beauty of recurring revenue is its predictability. Wall Street loves predictability. It allows management to set fixed cost and profit targets with confidence. It reduces the risk of wide swings that spook investors. If you took two companies with similar growth and profit rates, one with high predictability and the other with low predictability, the former would receive a higher valuation. Maybe a MUCH higher valuation.

As we previously mentioned, we know this can work in enterprise tech because we not only have famous historical examples like ADP, but we also have a great living example of the power of the recurring revenue business model in the form of customer service/support and maintenance agreements. For decades enterprise tech companies maintained a pile of annual customer-service contracts. They have added service agreement after service agreement after service agreement—tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands for many companies. These are renewable annual subscription contracts, just like XaaS agreements. Once the company has enough service-agreement revenue to cover their foundational service delivery and software maintenance costs, the good times begin. Because the incremental unit cost to serve one more contract customer is low, the margins are huge. Get enough of those agreements on your contract pile, and you have a brilliantly performing P& L. Software companies like Oracle report maintenance and support margins of over 80%.

We have also seen it start to happen among XaaS companies. We mentioned that Rackspace was achieving very solid profits— for a time. More rcare currently free to pursue the theoryeently they have been under pressure from the killer Cs, but Amazon’s AWS is now unveiling surprisingly impressive growth and profit numbers.

So we know the subscription financial model can work. It can be big, profitable. and growing. It has worked in other industries and it has worked in tech.

The last (and certainly not least) thing we love about XaaS financial models is their ability to generate free cash flow. What often gets lost in most people’s criticism of XaaS economics is that free cash flow often occurs before and at a higher rate than GAAP profits! That’s because the revenue recognition rules force the company to defer the revenue ratably over the entire year, but the cash often comes in up front. After a SaaS company has enough cash coming in from its current customers to pay its expenses and pay off the costs of acquiring new customers, the cash should start to flow. Many larger XaaS companies report free cash flow gains that are much stronger than their GAAP profits.

These four defenses of the XaaS business model are legitimate, and they are frequently cited by top executives of leading SaaS and managed services companies. Many even articulate a fifth defense based on redefining the market’s view of“true profits.” This argument, also known as “non-GAAP profits,” maintains that certain expenses like stock option costs and acquisition goodwill should not be imputed into a company’s operating expenses. This can make XaaS profit numbers skyrocket. As we mentioned, we are not focusing on that debate. We are focused on GAAP profits because it’s the current financial standard. Achieve GAAP profits and your non-GAAP profits will be breathtaking.

Although the model can indeed work, the reality is that many XaaS companies today are not being pressured to prove it. They are currently free to pursue the theory that market share and topline revenue growth are the only two success metrics that matter. Thus, they are heavily investing in sales and marketing to grab customers. The logic is that the platform with the most customers will ultimately be the winner, the wedge inflection point will be reached, and—with market dominance and a large base of customers—profitability will come.

But XaaS has its critics, too! There are plenty of skeptical tech executives, accountants, and analysts who rally around the lack of GAAP profits. They wonder what will happen to the FVAs and MTWs who are short of the profit inflection point when Wall Street enthusiasm wanes and investors begin demanding profitability.

This leads us to perhaps the most controversial financial aspect of the subscription business model. Let’s call the problem the “current cost of acquiring future revenues.” In the world of subscriptions, revenue comes in over time but sales costs are incurred up front. According to GAAP, you have to recognize that expense when it occurs, not match it over time to the recognition of revenue. So that means you are paying in this fiscal period for the revenue growth you are going to have in future periods. If you cut back too far to ensure current period profits, you can risk future period revenue growth. So many XaaS companies argue that spending 1 to 3 times current bookings on sales and marketing expenses makes sense because they are “buying scale.” The logic makes total sense, but GAAP accounting doesn’t make it look pretty. The argument that there will need to be some adjustment in sales cost accounting rules, along with setting aside stock option and goodwill expenses, continues to rage on. The reality is that both sides are right. Service-based businesses have been dealing with the current cost of acquiring future revenue problems for decades. Somehow they have survived and made GAAP profits along the way. But they have not been hyper-growth XaaS companies. Their up-front sales costs could be absorbed, and they could still turn a GAAP profit. But today’s “unicorn” XaaS companies simply can’t absorb that much sales expense. They will continue to argue it’s the best use of capital—better than paying out profits. If they are able to build large revenue streams where sales costs can ultimately be dialed down as a percentage and profits extracted, they could be right. But that has not yet happened, as we have previously pointed out.

No matter which side of the fence you are on and regardless of the profit horizon you have in mind, a successful XaaS provider must have a clear understanding of how real profitability will be achieved and in what time frame. That understanding begins with an inventory of the various ways XaaS providers can make money.

Gears of the XaaS Economic Engine

Although the concept of technology as a service seems to introduce an overwhelming number of creative ways to monetize with customers, the economic engine of a XaaS company is typically composed of up to five potential revenue streams:

• Asset Revenue. This is when the customer pays for the right to own and use a copy of the software or hardware product. Some XaaS providers may sell some of their technology up front as an asset as part of a large deal. Many traditional companies offer hybrid solutions comprised of a mix of on-premise assets and cloud services. And, we are all familiar with paying for a smartphone up front and then agreeing to a 3-year cellular service contract.

• Technology Subscription Revenue. This is when the customer pays for access to technology as a service. That is the XaaS offer. Companies may have one core offer or a broad portfolio of them.

• Annuity Services Revenue. This is when the customer pays for ongoing premium services wrapped around the technology subscription, usually in an annual or multiyear contract. Premium support or success services, information services, and managed services fall into this revenue category.

• Project Services Revenue. This is when the customer pays the XaaS provider for specific deliverables such as implemen- tation or user training. These services may be a fixed fee or charged on a time-and-materials basis.

• Transaction Revenues. These are revenues that occur per customer transaction. For example, every time a customer clicks a certain feature, they are charged a small fee. Hopefully, these services collect small fees at large volumes.

Each of these revenue streams has a unique financial profile in terms of margin and profitability. We can review these revenue streams using the four traditional components of any business model:

• Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and Gross Margin (revenue minus COGS). These are the costs associated with making, installing, and warranting the specific offer that is driving the revenue stream.

• Sales and Marketing (S& M). These are the costs to acquire and retain customers for this offer.

• Research and Development (R& D). These are the costs of developing the capabilities the customer is purchasing as part of this offer.

• General and Administrative (G& A). These are the operating and overhead costs allocated to the offer by the company that underlies it.

We track publicly reported data related to these revenue streams. For example, traditional technology companies reported the gross margin associated with selling hardware and software assets in Q4 2015.This is shown in Figure 8.3.

The average gross margin for these technology-as-an-asset companies is as follows:

• Software company average gross margin is 87% and the median is 89%.

• Hardware/systems company average gross margin is 50% and the median is 58%.

FIGURE 8.3 Technology Product Margins

We aren’t going to focus very much on traditional product margins, but we put it here for reference because employees from many hybrid companies will be reading this book. They will be using asset margins to blend into their overall financial model.

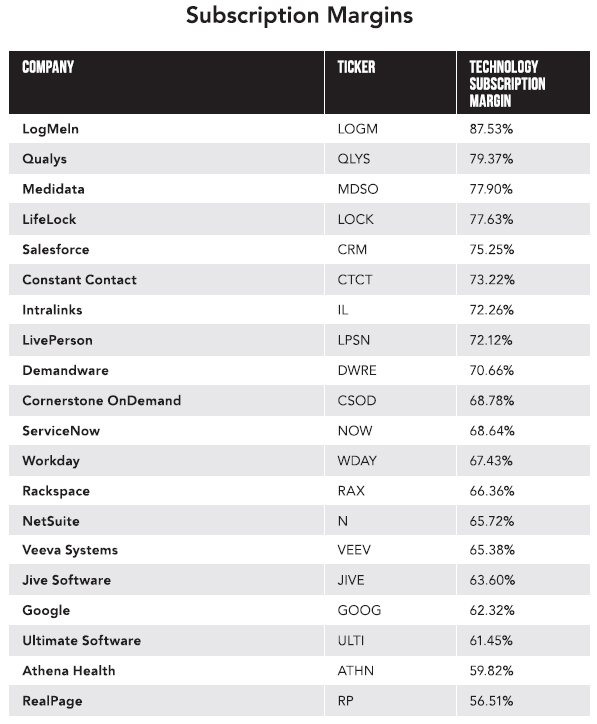

As for publicly traded XaaS companies, the Cloud 20 snapshot reveals a wide range of gross margin associated with technology subscription revenues. As shown in Figure 8.4 , these margins ranged from 56% to more than 87% in Q4 2015. Part of the margin variation is driven by each company’s decision on where certain specific costs should be accounted for. We know that there are lots of apples and oranges in comparing these numbers, but at least it offers us some visibility into actual performance. For XaaS companies, hosting costs are typically the major component of COGS, followed by basic customer support costs. We will kick out the outliers for our work ahead.

FIGURE 8.4 Subscription Margins

The average subscription margin for these XaaS companies is 69.60%, and the median is 68.71%. We will come back to these numbers soon.

As we move past basic subscription gross margins, we run into a limitation with the public data. We need to analyze all the revenue streams for the play we want you to run. However, not all the benchmark numbers we need for our financial model are widely available. The margin profile of things like project or annuity service revenue streams are often hidden from the public data. Therefore, we will supplement our data set with some TSIA industry benchmark data. As an example, Figure 8.5. provides an example of the financial data TSIA tracks related to project-based services. It shows the industry average and itemizes some of the peer groups we maintain related to project revenue performance. (Yes, we are teasing you with the average data, but not the peergroup breakouts.)

FIGURE 8.5 Business Model of Project Revenues

We will use these averages in the exercise soon to come. If you are a TSIA member company, we will be happy to provide you with your peer-group averages. We can also explain how we calculate each line.

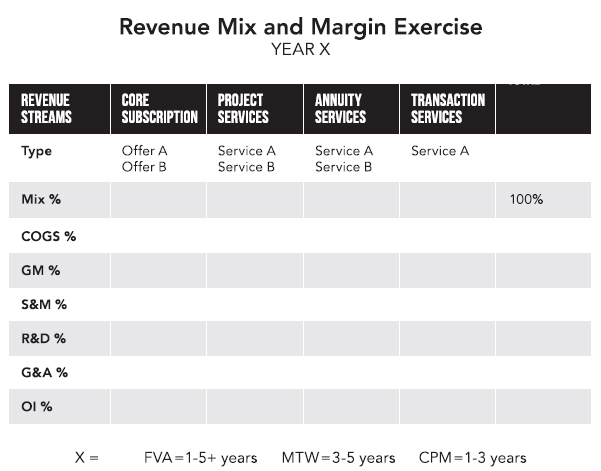

So, pulling together the public and proprietary data streams, we can create tables that provide a trimmed-range snapshot of the financial performance that is currently reasonable to expect for each revenue stream. In a trimmed range, we drop the bottom 25% and top 25% of data points. We look at companies performing within the 25% to 75% range of expected performance. This approach eliminates outlier performers on the high and low ends. Of course, these financial results are moving targets and shift over time. You could argue with this data source or that one. That is why we continuously benchmark the performance of these revenue streams so the database gets bigger and the trends get more apparent. However, what is important is the model. Figure 8.6. provides a sample readout we provide to TSIA members when they are working with us to model target economic engines.

As we have said repeatedly, in establishing a very clear path to XaaS profitability, we think the question of setting the target revenue mix is a central topic. Diversifying into a profitable project services business is just one example. The answer to what the optimal mix is varies greatly based on the profit horizon being applied to the XaaS business. But, in general, we see portfolio mix as a critical tool that management has on its journey to profitable XaaS.

This brings us to the important part of this chapter. We have been studying both the public data and our TSIA research data. We think we are starting to see some patterns in revenue mix, margins, and profitability. Admittedly, it is still pretty foggy out there, but things are finally beginning to take shape. The key is to marry some of the data about what is currently occurring in the pure-play XaaS world with other things that have been proven possible in the traditional tech world. The major breakthrough and the exercise we encourage each company to do is to financially model your XaaS going forward, armed with four weapons from this book:

• A knowledge of what state your XaaS business is in today and what other states remain for you to go through before you become a full-fledged current profit maximizer (CPM).

• A target financial model for each state that is rooted in some reality. The reality will be boxed in by a range of actual industry performance data from one of the sources we mentioned earlier.

• A target financial model exercise that forces you to think through the evolution of your offer portfolio and its accompanying revenue streams as you move from state to state.

• A timeline to journey from your current state to the CPM state that is also based in some reality.

FIGURE 8.6 Gross Margin Trimmed Ranges

The bottom line is that we think XaaS can be a 20% EBITDA (GAAP) business or better. Here is where we begin to model the financial and portfolio journey to get there.

Financial Keys for the Future Value Aggregator

Future value aggregators are focused on demonstrating that they can capture the high volumes of units that will lead to future success. The unit of future value (UFV) can be almost anything:

• Number of visitors

• Number of page views

• Number of subscribers

• Number of logins

• Number of customer logos

• Number of project plans under management

This means the first metric of financial success for FVAs is the raw number of UFVs being acquired and retained over time. They will track how many units they have captured and make those gains the lead in their financial reporting story.

The second slate of financial metrics—and often the more challenging achievement for FVAs—reflects their ability to actually convert the UFVs into paying customers. Are customers willing to pay for the core offer or its premium version? The relevant metric here is monthly recurring revenue (MRR) or annual recurring revenue (ARR). Investors will want to know how much customers are willing to pay for this offer and the dollar amount that grows over time. XaaS companies will also report:

• Number of paying customers

• Average subscription price or average revenue per user (ARPU)

• Monthly recurring revenue/annual recurring revenue

• Churn rate

To optimize the acquisition of these UFVs, the FVA will seek to minimize any friction linked to attracting and retaining them. FVAs will eventually need to prove a business model that acquires new customers in a way that does not break the bank. Customer acquisition costs (CAC) should become a relevant metric early on for most XaaS providers. The financial model of an FVA can collapse under the weight of unwieldy CAC. As we pointed out, there are public XaaS companies running with sales and marketing expenses over 50% of revenue. Some companies have been over 100% at points in their development. Of course, this is not likely to be sustainable in the long term, but the bar for FVA spending is pretty high and forgiving at the present moment.

In summary, here are six metrics that are typically highly correlated to the success story of future value aggregators:

• Growth in units of future value

• Growth in number of paying customers

• Average revenue per user

• Monthly recurring revenue (total recurring revenue from all paying customers)

• Customer acquisition costs (the amount of money spent, on average, to acquire a new customer)

• Churn rate (percentage of paying and non-paying customers who stop subscribing or using the core offer each month)

FVAs will be heavily weighted toward subscription or transaction revenue streams. They will focus very little on monetizing project or annuity services. These revenue streams are more complex to sell and simply slow down the momentum of acquiring units of future value. In this profile, where the focus is on growth, the only revenue stream that is likely to be profitable is the premium annuity subscriptions. Any professional services required to get the customer up and running are likely to be bundled or absorbed into the cost of the subscription. Figure 8.7. models the revenue streams for a XaaS provider in the FVA profile.

This sample model shows a negative operating profit. Many FVAs will run negative operating profits as they invest heavily in sales and marketing, experience lower gross margin on the core subscription offering, and throw services or basic access in for free to secure new customers.

Scanning the industry, we can easily find real-world examples of companies successfully executing the FVA financial profile. To define successful FVAs, we would look for companies that have the following attributes:

• Double- or triple-digit top-line growth in UFVs

• Double- or triple-digit revenue growth (albeit sometimes from a small number)

• High percentage of revenue spent on sales and marketing

• Majority of revenue coming from the core offer

• Quarterly losses

• Company valuations that are typically 10 times (or higher)their annual company revenues

FIGURE 8.7 FVA Revenue Streams (Note: All costs are expressed as a percentage of revenue for that specific line of business/revenue.)

DocuSign is a perfect example of a company that successfully ran the FVA profile claiming over 50 million users and is now pivoting toward the mid-term wedge. They are moving from the value of electronic signatures offered in various fee and free combinations to offering digital transaction management for enterprises. As they make the pivot, they are beginning to offer professional services as well. Founded in 2003 and beginning sales in 2005, 3 DocuSign has spent the better part of a decade in FVA mode. They have raised more than $400 million 4 to help subsidize the operations in those years and lay the foundation for a profitable wedge model.

LinkedIn is another interesting example of an FVA that is moving toward an MTW player. The company exhibits all of the classic attributes. They grew members from 20 million in 2006 to 400 million by 2015. 5 The company has been growing revenues at a double-digit pace and has exceeded $2 billion. However, most of that revenue is not coming from the 400 million people they aggregated, most of whom take advantage of free membership. The company has learned to monetize its units of value (members) by offering talent solutions to corporate HR departments and advertising solutions to marketers. This is in addition to its premium subscription offers to members. The company has been profitable on a GAAP basis, but only marginally (it publishes a non-GAAP EBITDA calculation that reflects much more favorable profits). Even after 10 years in the market, the company is still spending almost 37% of revenue on sales and marketing. We would expect it to begin to show the GAAP profit power of its model soon, but it may come at the same time as revenue growth slows. We got a taste of the market’s reaction to that in early 2016, when LinkedIn’s stock dropped 40% in value because the company revised growth guidance down to “only” 20% to 30%.The company’s market capitalization dropped from $25 billion to $13 billion, from a 10-times multiple of revenue to a 4.5-times multiple. This is a classic case of the challenge that FVAs face as revenues slow, and they must begin to transition their stock valuations from high growth to solid growth plus profits.

Financial Keys for the Mid-Term Wedge

XaaS providers that have been aggregating paying customers and believe they can now turn the business model toward profitability have a longer set of financial metrics to manage. In the midterm wedge profile (MTW), subscription growth and MRR are still critical metrics. However, companies in the MTW profile must now also focus on costs. Are the costs to acquire new customers (CAC) and to serve existing customers (COGs) coming under control? Is the company expanding and renewing customers (CEC, CRC) in the most cost-effective way possible? Simple churn rate metrics get replaced by more sophisticated measures. In addition, the MTW must pay close attention to commoditization and discounting. Some of the basic numbers reported by FVAs may actually drop below the radar as the company becomes larger and these more sophisticated metrics take precedence. Pulling these thoughts together, there are nine financial metrics the MTW should watch and improve:

• Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR). Average amount of money a customer is spending with the company.

• Customer Acquisition Costs (CAC). The amount of money spent, on average, to acquire a new customer.

• Unit Renewal Rate (URR). The percentage of customers that are renewing their subscriptions.

• Contract Value Renewal Rate (CVRR). When renewal contracts come up each month, does that pool of customers spend more or less money with the company? Ideally, CVRR is over 100%.When CVRR is below 100%, customers may be churning or customers may be securing discounts during renewal.

• Discount Rate on New and Renewal Deals. If discount rates are high, it is a sure sign the offer is commoditizing.

• Technology Subscription COGs. The percentage of subscription revenues spent on the technology and support related to delivering the offer.

• Annuity and Project Revenue COGs. The percentage of annuity and project revenues that are spent to deliver those services. In the FVA profile, these services may have been free or break-even. Now, these revenue streams should be achieving at least industry average gross margins.

• Cost to Renew Customers (CRC). What percentage of sales and marketing dollars is spent on the process of renewing customers? If this percentage is high, it will be difficult to tamp down overall S&M spending.

• Cost to Expand Customers (CEC). What percentage of sales and marketing dollars is spent on securing incremental revenue from existing customers? The cost to secure expansion revenues should be much lower than the cost to secure revenue from a new customer. If this is not true, it will again be difficult to tamp down overall sales and marketing expenditures.

MTWs are still heavily weighted toward technology subscription revenues. Yet, they should now be diversifying. That could come in the form of multiple core offers, but they may also begin offering project and annuity services that create the following financial benefits:

• Bring incremental revenue and higher-margin dollars into the financial model

• Help reduce the cost of renewing customers (CRC) by delivering fee-based services that drive adoption and stickiness

• Become a cost-effective channel for identifying expand selling opportunities (reduce CEC costs)

There are likely to be three revenue streams in play for the MTW, at least in enterprise markets: the technology subscription, premium annuity services, and fee-based, project-based professional services. In this profile, where the focus is turning toward profitability, all three revenue streams should be profitable or close to reaching profitability. Also, a slightly greater percentage of revenue will be coming from the annuity and project services. Figure 8.8. models these three revenue streams for a XaaS provider that has crossed the line into profitability.

FIGURE 8.8 MTW Revenue Streams (Note: All costs are expressed as a percentage of revenue for that specific line of business/revenue.)

This sample model shows a positive operating profit of 2.5%. We would expect MTWs to be running quarterly operating profits anywhere from negative 10% to positive 10% as they approach and pass the profit horizon. We would also expect a year or two where the MTWs have operating profits that bounce from positive to negative, quarter to quarter, as they dial-in the operating model.

To identify real-world mid-term wedge examples, we would look for companies that have the following attributes:

• Healthy top-line revenue growth, but it may be slowing

• Slowly trending toward spending less money on sales and marketing as a percentage of total revenue

• Slow but steady improvement in gross margins as scale is reached

• Positive and stabilizing trend in operating income (whether or not it is currently profitable)

• Majority of revenue still coming from a core offer (subscriptions or transactions) but growing a diversified portfolio

• Company valuations are typically 5 to 10 times (or higher) annual company revenues

Workday is a MTW SaaS company that is beginning to exhibit these trends. Figure 8.9. documents the incredible revenue growth rate of Workday, which has been hovering between the 60% to 75% range. It also documents the high spend on sales and marketing, which is fortunately stabilizing, and the double-digit negative (but improving) operating income quarter after quarter. In early 2016, Workday was sporting a market capitalization that was 11 times annual revenues! Impressive. But, alas, the journey from FVA to MTW has also impacted Workday and its stock price. As the company begins to signal a slower growth outlook and GAAP losses alternate between improvement and decline, the market is reacting by shaving its valuation premium.

No conversation about the MTW is complete without a discussion of Salesforce. Everyone in the industry seems to be waiting for them to hit the profit inflection point. Would it be at revenues of $500 million? $1 billion? $5 billion? Will it be at $10 billion?

FIGURE 8.9 Workday Financial Performance

There is no doubt that Salesforce could be very profitable on a GAAP basis when and if they need to. They just have to turn the sales and marketing dial a bit to the left. But their stock is doing just fine, so the pressure to demonstrate profits is tolerable. They will orient toward growth and market share through high sales costs for as long as they can. But they are clearly messaging that they are making preparations to demonstrate strong profitability. The recent analyst briefings have them on record as saying they are going to take a more balanced approach to financial management. They are the epitome of an MTW sitting on the edge of the profit inflection point, waiting to be pushed into green territory. In early 2016, they had a market cap of around 9 times annual revenue.

Financial Keys for the Current Profit Maximizer

As we mentioned, most large enterprise tech companies that have established a history of producing rich margins are finding it hard to convince profit- and dividend-oriented investors that unprofitable XaaS offerings, even if they are growing rapidly, are a good thing for business. Take this quote from a Forbes article titled “Why the 10% Drop in Software Sales Is the Most Important Number in IBM’s Q2 Earnings Report” 6 as an example of market reaction to the fish model:

“We are concerned that IBM’s software business may see increasing pressure from the transition to a SaaS business model,” wrote Jefferies equity analyst James Kisner. “Recall, Oracle ORCL +0.00% reported very light license revenues driven largely by an accelerating transition to cloud (SaaS).”

Meanwhile, Credit Suisse’s Kulbinder Garcha last week reiterated an underperform rating in part because software revenue would need to come in above trend to boost earnings above consensus, something he sees as highly unlikely. He added, “Following a thorough analysis of their cloud, we believe it may ultimately be margin dilutive for IBM, even if the company drives revenue.”

Established technology providers are being forced to optimize XaaS business models as rapidly as possible. When pursuing this current profit maximizer (CPM) profile, management teams must immediately focus on the financial metrics that predicate a profitable XaaS business model. Many of these are the same exact metrics that are critical in the MTW profile:

• Average monthly recurring revenue (AMRR)

• Customer acquisition costs (CAC)

• Unit renewal rate (URR)

• Contract value renewal rate (CVRR)

• Discount rate

• Technology subscription COGs

• Annuity and project revenue COGs

• Cost to renew customers (CRC)

• Cost to expand customers (CEC)

However, the CPM have additional financial focal points:

• Revenue mix

• Revenue line profitability

• Upsell rates and COS

• Cross-sell rates and COS

• Focused R&D and G&A expense targets

• Platform investments eating away at sales, service, and G&A labor costs

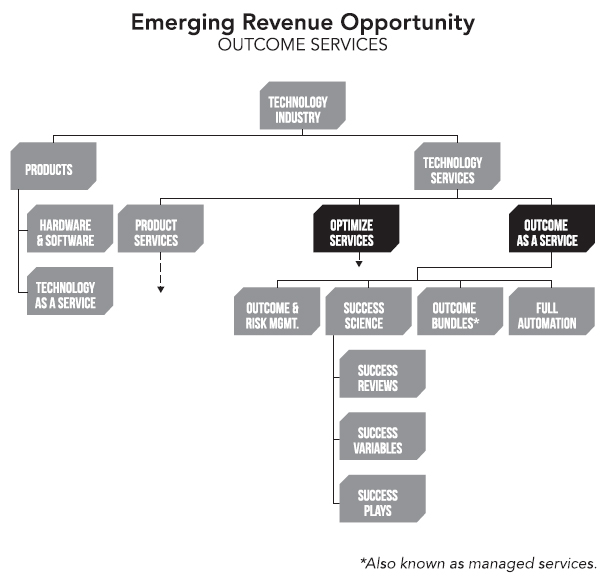

Out of the gate, most CPMs should be adept at monetizing additional revenue streams beyond the core technology subscription offers. This includes all the new types of value-added services we identified in Chapter 6 . Ideally, they would have healthy revenue in most if not all of the revenue streams we identified at the beginning of this chapter:

1. Annuity Revenues. The customer pays for the service in an annual or multiyear service contract.

2. Project Revenues. The customer pays for the service on a project-by-project basis.

3. Transaction Revenues. The customer pays every time they execute a specific activity, such as processing a report or submitting an inventory.

In addition, these companies should have become very proficient at getting sales costs under control. As we have often pointed out, one key to doing that is having a healthy balance of growth coming from adding new customers at a high CAC while strongly expanding existing customers at a much smaller sales cost (CEC). Combined with a high renewal-rate revenue stream at a low sales cost (CRC), the company’s overall COS drops to a manageable 20% to 30%. We are not saying that all XaaS companies at this level will have COS of 30% or less. Some companies may choose to continue to spend lavishly on CAC to perpetuate their land grab, thus driving overall COS up. What we are saying is that it is POSSIBLE for a XaaS company at this level to balance very respectable growth rates with very manageable overall sales costs.

Figure 8.10 models the optimized economic engine of a profitable CPM that has established multiple revenue streams.

As shown in this figure, even though the core technology subscription is only generating an OI of 9.8%, the overall economic engine is generating an excellent operating profit of 20.2%.

There are examples of companies that are leveraging multiple revenue streams to maximize the profitability of their XaaS offer or to manage their swallowing of the fish. These companies are working hard to remain profitable through this significant industry transition. The telling attributes of the CPM profile would include:

• Still solid but not spectacular growth in revenues.

• Profitable growth in fee-based annuity and project revenue streams.

• Operating incomes that remain positive quarter to quarter.

• Company valuations that are typically a multiple of 3 to 10 times (or higher) annual company revenues.

FIGURE 8.10 CPM Revenue Streams (Note: All costs are expressed as a percentage of revenue for that specific line of business/revenue.)

The first example of a CPM is Veeva Systems, a company specializing in SaaS applications for the global life sciences industry. There are plenty of SaaS companies with annual revenues north of $500 million but still with negative operating incomes. Veeva is bucking that trend. With annual revenues half that amount, the company is solidly profitable. In the second quarter of 2015, the company generated an operating income of 23%. More importantly, the company is generating over 20% of revenues from value-added services at a margin of 24%. Service offerings listed on the Veeva website include: 7

• Transformation Consulting

• Professional Services

• Managed Services

• Environment Management as a Service

• Veeva Code-Based Custom Development

• Administrator Training

In early 2016 Veeva had a market cap of around 8 times annual revenue.

The company went public in 2011 with 33% of revenues coming from fee-based services as a critical source of revenue and some margin. By 2015, services was generating almost $20 million a year in margin. Figure 8.11. documents the financial performance forVeeva from 2013 through 2015.As can be seen, unlike many SaaS companies, Veeva has doubled operating income dollars while growing revenues from $129 million to more than $300 million.

Perhaps one of the more instructive examples of companies pivoting from selling technology as an asset to selling technology as a service is the Canada-based software company OpenText. A public company since 1996 and with revenues now over $1 billion, this company is an established software provider. OpenText has embraced a philosophy of allowing customers to consume technology the way they want to consume technology. If OpenText customers want to continue to purchase software licenses, they can. If customers want to migrate to subscription pricing, they can. If customers want OpenText to provide their software as a managed service where OpenText manages the software on the customer’s site, that is an option as well. This philosophy has led to a diversified economic engine. Here are notes from the company’s 2015 annual report:

During fiscal 2015 we saw the following activity:

• Total revenue was $1,851.9 million, up 14.0% over the prior fiscal year.

• Total recurring revenue was $1,557.7 million, up 18.1% over the prior fiscal year.

• Cloud services and subscription revenue was $605.3 million, up 62.1% over the prior fiscal year.

• License revenue was $294.3 million, down 3.8% over the prior fiscal year.

• GAAP-based gross margin was 67.5% compared to 68.5% in the prior fiscal year.

• GAAP-based operating margin was 18.8% compared to 18.5% in the prior fiscal year.

• Non-GAAP-based operating margin was 30.9%, stable year over year.

• Operating cash flow was $523.0 million, up 25.4% from the prior fiscal year.

• Cash and cash equivalents was $700.0 million as of June 30, 2015, compared to $427.9 million as of June 30, 2014.

FIGURE 8.11 Veeva Financial Performance

License revenue is shrinking and represents less than 16% of total company revenues. Technology subscription revenues are growing rapidly and now represent 33% of total company revenue. Total recurring revenues, which include multiyear managed services and support services contracts, now represent 84% of company revenue. Most importantly, the company has remained profitable throughout this transition in revenue mix.

In early 2016, OpenText had a market cap of around 3 times annual revenue.

Rackspace is another MTW that has proven profitability. Before they got caught up in a price war led by AWS, the company gener ated an operating income as high as 29% by focusing on “fanatical support.” Perhaps this is a proof point that differentiated services can help unlock higher profits. In fact, one of the company’s newest tactics to battle against AWS’s aggressive price-cutting onslaught is to refocus its offers and messaging to “Managed Cloud.” The lead paragraph on their website in February 2016 read:

“Experience our highly specialized expertise and best-in-class service across the world’s leading infrastructure technologies, databases, and applications.”

They position the technology second and their expert services first.

As we made clear in Chapter 5 , Adobe is one of our favorite examples of a traditional license software company that has transitioned to a profitable subscription business model. By May 2013, Adobe was no longer licensing its popular Creative Suite software. Customers could only consume the software through a subscription. 8 A majority of Adobe revenues are secured through the technology subscription. As of 2014, only 11% of Adobe revenues were related to any type of value-added services. The company has proven they can live on the profitable side of the wedge model—but barely. As shown in Figure 8.12 , the transition from a big license engine to a big technology subscription engine has resulted in almost halving the operating income of the company. There is a lesson to be had here that we will explore more in the chapter on churn, costs, and commoditization.

In early 2016, Adobe had a market cap of around 9 times annual revenue.

But the one example that everyone loves to talk about most right now is Amazon Web Services. More than any other company we know of, they have successfully passed through all three phases in a remarkably short period of just 10 years.

FIGURE 8.12 Adobe Financial Performance Since Migrating to Subscription Pricing

Although the company has just recently started to break out the financial profile of this business unit, Amazon is reporting the following financial statistics: 9

• AWS is generating $2 billion in quarterly revenues.

• AWS revenues are growing at 78%.

• AWS is generating 25% operating income.

The AWS offering is incredibly service light from a revenue standpoint. We think this is a risky move for most companies. Betting the farm on features or scale alone can work, but is not often sustainable. For every Google search business, there are dozens of troubled XaaS companies that were driven into the ground by lower-priced or better-featured competitors. For AWS, revenue and profits are generated through a big technology transaction gear of renting computing cycles at very low rates. Their strategy is based on portfolio diversification. As their capabilities grow, customers expand their average MRR. For this wedge model to be so profitable, it is clear that Amazon must keep S&M and G& A expenses in check. It must also ensure that revenues are growing faster than COGS.

Because AWS is part of Amazon, we cannot place a specific stock value on it. However, many analysts speculate it to be worth more than $100 billion, which would give it a market cap of around 13 times annual revenue.

By comparison to these great XaaS company examples, in early 2016 most of the large, traditional enterprise hardware and systems companies were trading at around 1 times revenue. Most traditional enterprise software companies were trading at revenue multiples in the 2 to 3 times range. For those companies, it is easy to see why getting through the fish and potentially achieving multiples of 5 times or 8 times is of extreme interest to management and boards of directors alike. That is why we wrote this book—to gather up our reading of the tea leaves (and the data)—to begin formulating some road maps for the journey. Some road maps are for traditional companies moving into the subscription economy, and others are for companies born in the cloud era that need to begin pivoting their story from remarkable revenue growth to profits and solid growth.

Profile Traps

The other thing we are learning on these journeys is that there is real potential for XaaS offers to fall into traps in these three profiles. This is going to be especially dangerous if financial markets become more conservative. There are scenarios where actual company performance does not align to the strategy keys of the profit horizon. There are three very recognizable scenarios of disconnect:

1. FVAs that are spending like a drunken sailor on acquiring units of future value, but have no effective strategy to monetize them.

2. MTWs that have accumulated a large mass of paying customers but are not yet demonstrating improving economies of scale or efficiency, especially in sales and marketing.

3. CPMs that need current profits but are afraid to make some of the hard decisions to rapidly build scale by forcing customers onto their platforms, charging profitable prices, or diversifying their revenue mix.

What is the consequence of these mismatches? For public companies, the price will be paid in the company valuation. Just look at cloud storage and file sharing provider Box. Their valuation began a descent before their IPO and it has continued. We would argue they did not manage effectively from FVA to MTW.

The bottom line is this: There are specific management and financial objectives for each phase in the profit horizon journey. Start-up XaaS providers need to understand—if they are on an FVA or MTW profit horizon—what their financial keys are and what time frames they will accomplish them in. Legacy technology companies need to transition to XaaS on a path that accelerates them quickly into CPMs. We strongly believe aligning your XaaS strategy decisions with the profile you are attempting to execute increases your ability to improve shareholder value.

Timeline Planning

The notion of the three states of XaaS offers (FVA/FPI, MTW, CPM) is especially helpful as you think through the number of years in your financial transformation journey. Central to this part of the exercise is seen in Figure 8.13.

Although there are certainly some exceptions, the companies we have studied seem to spend a predictable range of years in each of these three states of management focus. The left column represents the shortest amount of time we have seen anyone in each state. The right column represents the longest. The “+” sign means that some companies never seem to get out of the FVA state. We predict these companies will flame out when the financial markets turn bearish.

FIGURE 8.13 Financial Transformation Journey

There are three important uses of this chart. The first is to help you predict how long your journey may be from your current state to achieving your end state of more than 20% GAAP EBITDA. You simply identify what state you think you are in today and make a decision about whether you plan to run through the remaining states quickly (left column values) or if it will require more time (right-hand column values). For each year of your journey, your goal would be to complete the revenue mix and margin exercisey shown in Figure 8.14. You should be able to explain why you think you are moving through states at a fast pace or a slow one.

Once this exercise has been completed for each year in your projected journey to 20% EBITDA, anyone in the company will be able to quickly see both the financial and the portfolio journey you need to pursue. You can then apply these ratios to your revenue projections to begin to compute actual dollar profits and losses along the way. This may be helpful in assessing the total capital required to get to the profit horizon event.

FIGURE 8.14 Revenue Mix and Margin Exercise

The second great use is to benchmark your current financial performance against our target states. If you look different, why is that? Are your costs lower in some areas and higher in others? Is your portfolio diversifying as the company changes states and approaches new targets? These financial models are by no means the only way to be a successful XaaS business, but they do seem to be characteristic of many we see.

Finally, if you are a traditional tech company, you can use this model to determine your point of entry into the XaaS market. As we have emphasized, we think these companies are smart to consider entering at scale in a CPM state. If managed correctly, they can use their huge scale to skip the FVA/FPI state and maybe even the MTW state. By forcing all their customers onto the XaaS offer, they can literally enter the market as a CPM and achieve GAAP profits in their first or second year.

XaaS Playbook Plays

Two plays that help a management team answer the question, “Can we make money with this XaaS offer?” are identified in this chapter:

Play : Identify Your Target Financial Metrics

Objective : Identify the metrics that will be used to determine if the company is on track to meet its business model objectives.

Benefits:

• Prioritizes critical metrics to track.

• Provides talk track for both employees and investors regarding how the company is defining success.

Players (who runs this play?) : Core players: CFO, CEO, and board. Review team: board.

Play : Model Your XaaS Profitable Economic Engine

Objective : Identify the specific revenue streams the company intends to monetize. Identify the mix and margin expectations for each revenue stream. Determine the number of years in your journey to target GAAP profitability.

Benefits:

• Identifies the target financial model for the company.

• Identifies investment requirements.

• Set expectations on target margins for each revenue stream.

Players (who runs this play?) : Core players: CEO, CFO, product development, services, marketing. Review team: CEO, CFO, board.

9The Case for Managed Services

This book is about conducting successful XaaS offers. For companies that have been selling technology as an asset, the pivot to selling technology as a service can be overwhelming. The many things to consider and worry about can make this seem like a bridge too far. But a first step that traditional technology companies can take on this journey to help them ease into the XaaS marketplace is to stand up a managed services capability.

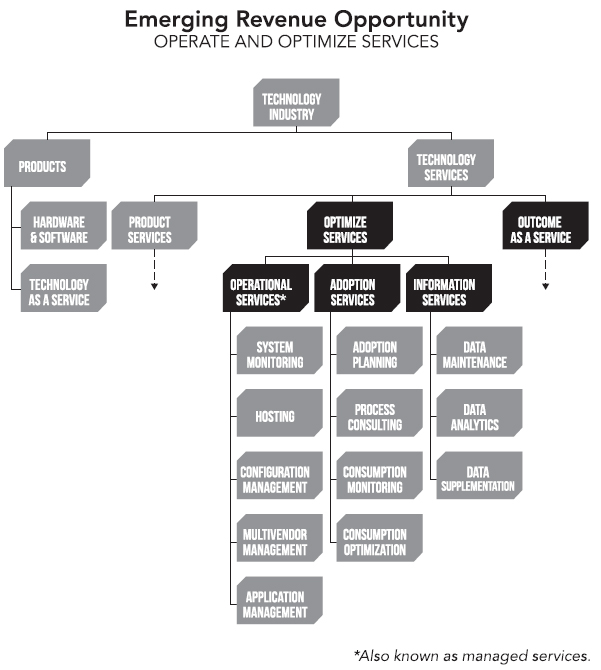

In this chapter, we’ll explore the special case of managed services (MS) as entrée into XaaS. For the past several years, we have been aggressively studying and benchmarking how enterprise tech companies of all sorts are incubating and growing MS businesses. So, let’s discuss the pros and woes of how, why, and when to build your MS offer. Specifically, we will cover the following ground:

• The explosion of managed service revenues.

• Trends driving managed services.

• The many flavors of managed services.

• Why product companies fear managed services.

• Why companies should embrace managed service opportunities.

• Success tactics when incubating managed service capabilities.

By the end of this chapter, management teams should clearly understand why managed services is the fastest growing service line in the technology industry and why this opportunity shouldn’t be ignored.

The Explosion of Managed Services

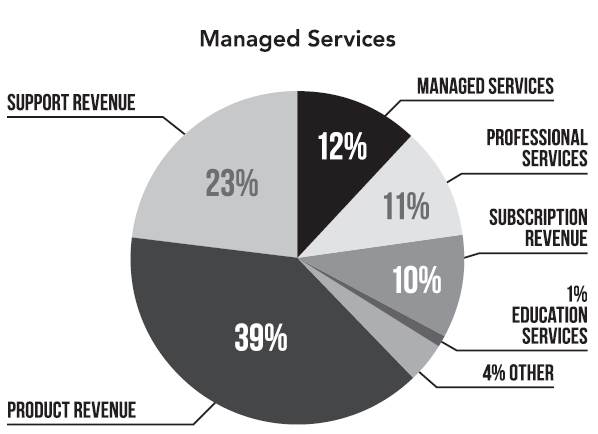

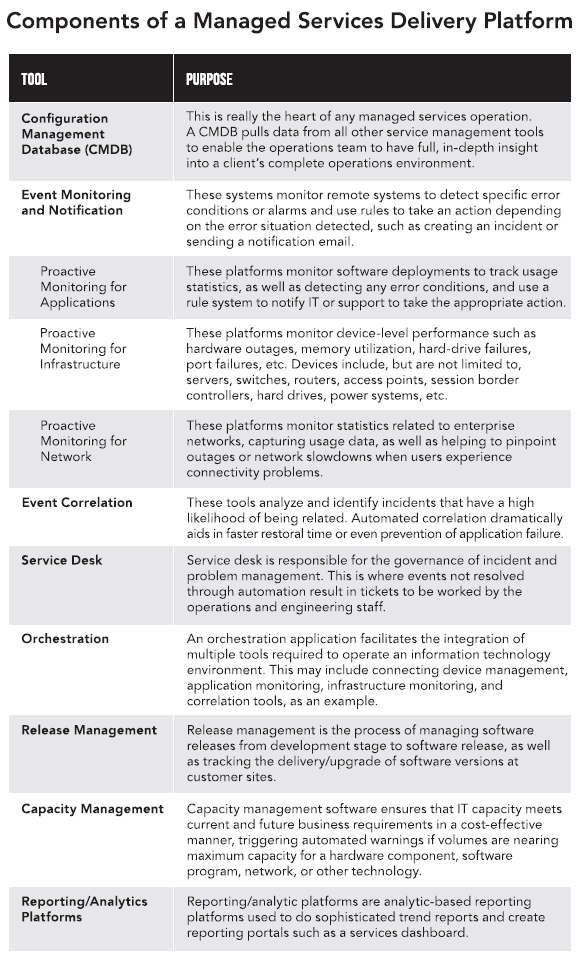

We benchmark the overall revenue mix of technology companies at a level of detail not available in the standard 10-K. One of our objectives with this data is to clearly understand how the economic engines of technology companies are changing over time. MS revenues have been present in the industry for years. In 2013, our data showed that 23% of the companies we benchmarked had some type of MS revenue stream. By the end of 2015, 46% of companies were reporting an MS revenue stream. That is a doubling of MS offers in just two years.

Not only are more companies jumping into MS, but MS is also starting to become meaningful revenue. The average revenue mix for companies that benchmark their managed services business with TSIA indicates that MS has blossomed to 12% of total company revenues, as seen in Figure 9.1.

More importantly, the average annual growth rate of these MS revenues exceeds 30%. This growth rate is far outpacing the average growth rate for product revenues we see in the industry today. In our last T&S 50 snapshot of 2015, product revenues, on average, were shrinking 8%! (See Figure 9.2. )

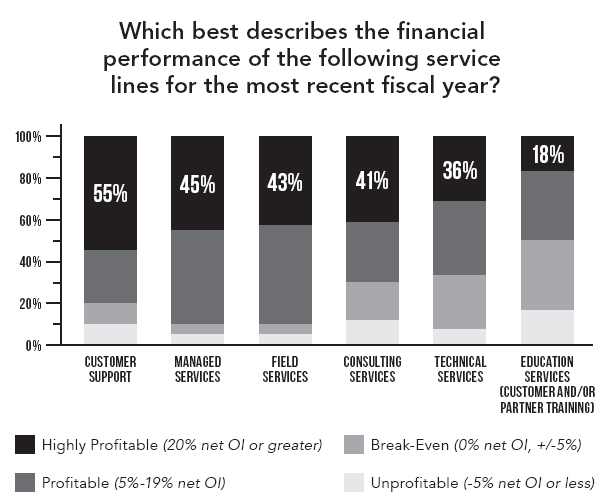

Finally, MS revenue streams are proving more and more profitable. The TSIA MS benchmark reports average MS gross margins greater than 40%. Some MS providers are generating gross margins just slightly south of 70%. In our annual survey on overall organizational structure, we ask technology companies to simply report the general profitability profile of every service line they have, the results of which are seen in Figure 9.3. For the past two years, MS has been reported as the second most profitable service activity, right after highly lucrative support services.

FIGURE 9.1 Revenue Mix for Companies that Benchmark MS

FIGURE 9.2 MS Revenue Annual Growth Rate

FIGURE 9.3 Profitability of Service Lines

So, MS is undoubtedly a rising star in the economic engine of technology companies. But why?

Trends Driving Managed Services

Multiple trends are driving the demand for managed services. Many of these trends were heavily discussed in our last two books, but let’s do a quick review:

• Reducing Operational Complexity. Customers no longer want the headaches of running IT operations, especially if they don’t view this as a core competency of the company.

• On-Demand Capacity. Customers don’t want to pay for IT capacity they don’t need. MS models are much more flexible and allow the customer to buy capacity as required.

• OpEx versus CapEx. Some customers (clearly not all) have a preference for spending operating dollars and not capital dollars when it comes to technology. CapEx leads to having big, lump-sum payments and then owning assets that must be depreciated over time. Migrating IT expenses to OpEx typically leads to smoother, more predictable expenses over time.

• Value Beyond Technology. Customers look for technology providers to apply unique insights to help maximize the business impact of technology. One common value proposition is MS offers that feature accelerated technology adoption versus do-it-yourself tech.

• Economies of Scale. Technology providers can create environments, tools, and processes that support multiple customers. These economies should allow providers to deliver technology environments more cost effectively than customers can create as a one-off.

• Strategic versus Tactical. CIO magazine published an article citing the growing demand for managed services. The magazine reported that CIOs are interested in leveraging outside vendors to manage day-to-day operations so internal IT staff can focus on strategic initiatives. 1

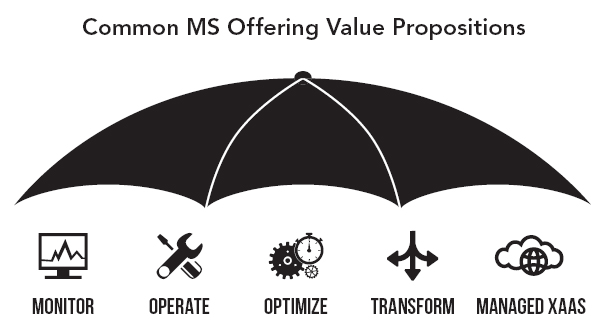

Generically, TSIA sees these trends resulting in five common MS offering value propositions, listed below and shown in Figure 9.4.

• Monitor. Monitor technology availability and performance for the customer.

• Operate. Operate the technical environment on behalf of the customer.

• Optimize. Work with the customer to optimize technology costs, improve technology adoption, and maximize the business impact of the technology.

• Transform. Help the customer implement and integrate a new set of technology capabilities.

• Managed XaaS. Technology may be on site, hosted, or a hybrid of the two. The solution is typically comprised of product (hardware and/or software), professional services, support, and operations elements bundled into a single per-unit, per-month price governed by a managed services agreement. Hardware and/or software is owned by the managed service provider.

FIGURE 9.4 Common MS Offering Value Propositions

Importantly, current and future generations of MS don’t look anything like the low-margin outsourcing businesses of the past. Ideally, services are cloud-enabled, delivered from a remote network operations center. Delivery resources are typically shared across multiple clients. The product elements within the MS offer may be hosted and/or on premises; they may be single tenant or multi-tenant.

In September 2015, Forbes cited a study that more than half of IT managers expect to use multiple managed service providers (MSPs) within the next two years; a whopping 85% are at least somewhat likely to use MSPs. 2

So, if you have a customer who is demanding one of the MS value propositions previously cited and you don’t have an offer, you may lose that customer. How many customers can you afford to lose until you bring an MS offer to market that the market clearly wants?

The Many Flavors of Managed Services

Before you decide whether your company should pursue an MS business, it is important to segment the different types of MS businesses. TSIA segments MS offers based on the following five questions:

1. Is the offer standard across many customers or unique for each customer (as defined in Chapter 6 on portfolio power)?

2. Is the value proposition differentiated (again, referring to Chapter 6 )?

3. Regardless, whether the technology is on site or not, can the services be delivered off site (virtually)?

4. What are the specific value propositions of the offer as defined by TSIA’s five classic value propositions for MS offers?

5. Does the MS provider own the technology assets under management, or does the customer own the assets?

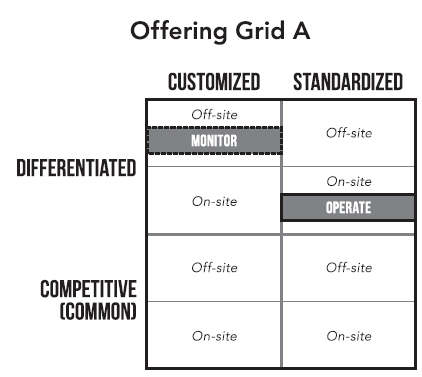

So, let’s map two different example offers:

1. Off-Site Monitoring. The customer would like you to monitor technology that’s been purchased from your company. You have unique capabilities to deliver this monitoring remotely.

2. On-Site Operation. The customer wants the technology to be present on their site, but they don’t want to manage the environment. You need to provide some onsite services to manage their environment. Also, they do not want to own the technology.

Figure 9.5 maps these two offerings on our offering grid. The grid has been further segmented to show whether an offer is being delivered on site or off site. A solid line around the offer means the MSP owns the technology assets. A dotted line around the offer means the customer owns the technology assets.

FIGURE 9.5 Offering Grid A

The question quickly becomes, “What are the high-growth and profitable MS offers?” This is exactly what we have been studying since 2013. There is no doubt that standard, off-site offers, where the customer owns the asset, have the greatest potential to drive the highest MS margins with the least financial risk to the provider (Figure 9.6. ).

FIGURE 9.6 Offering Grid B

Breaking our benchmark data down into more detail, here are the highest-to-lowest margin MS offer types:

• Customer premised, customer owned, remotely monitored.

• Customer premised, customer owned, remotely operated.

• Hosted, customer owned, remotely monitored.

• Hosted, customer owned, remotely operated.

• Hosted, provider owned and operated.

Also, the data clearly shows that standard offers are more profitable than custom offers. On average, there is a nine-point profit improvement if an MS offer can be standardized across customers.

Unfortunately, we see that customers often start MS conversations with a host of custom requests. In fact, many of these offers are actually created “in the field” to meet the needs of specific deals. That is not the right way to approach your MS business. Instead, it reflects a common scenario where headquarters are hesitant about launching an MS business when their customers clearly want it. So, rather than lose the deal and the customer, sales makes one up. In some of these early deals, customers are often interested in the provider owning the assets.

Here’s a better way: To accommodate early customer requests, successful MSPs are making three moves on the offer chessboard, listed here and seen in Figure 9.7.

• First Move. Work with strategic customers to define a differentiated MS offer. You can lean toward customers owning the assets, but you may need to be flexible. Perhaps you can arrange for a third party to carry the paper on the assets while you provide the managed service. Begin signing MS contracts.

• Second Move. Begin identifying the common building blocks of customer needs. Create a “standard” set of LEGO® building-block MS capabilities customers can string together into an offer that meets their needs.

• Third Move. Maximize every opportunity to leverage technology and off-site labor to deliver the offer.

FIGURE 9.7 Offering Grid C

So far, we have talked abot the compelling and special case of MS in the enterprise tech business circa 2016. We have helped define the drivers for MS offers. We have also helped define the different types of MS offers and how technology providers are successfully maturing their MS offers. Despite this help that we regularly offer to members, though, we still see many traditional product companies incredibly resistant to exploring MS conversations with eager customers. Why?

Why Product-Centric Companies Say No to Managed Services

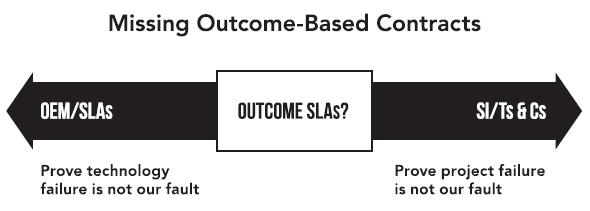

George Humphrey vice president of research for the Managed Services practice at TSIA, refers to this dilemma as “the battle of the CFOs.” In one corner, we have the customer CFO. In their role, they are keen to acquire some of the benefits listed earlier—reduced operational costs, predictable IT costs, and improved ROI from technology investments. In the other corner sits the technology provider CFO. Their role is to protect the financial business model. They are extremely reticent to sign off on any offers that may increase company risk, reduce cash flow, or impact the margin profile of the company. The customer is asking for managed services, but the CFO and other executives at your company are quick to raise the following concerns:

• We don’t own customer assets. When negotiating MS deals, customers may not want to purchase the technology assets being managed. This means the provider has to carry the cost of these assets on their books. CFOs may be loath to reflect lower retained earnings on the balance sheet as a result of these added costs.

• Delayed revenue recognition. If the customer is not paying for the assets up front, that means the revenue for this technology will trickle in as part of a long-term service contract. Not ideal! We are a product company—we recognize product revenue, and we recognize it as soon as legally possible!

• Service revenue intensive. These MS deals are going to increase service revenues and decrease product revenues. Our financial model indicates how much revenue should be coming from products versus services. We will start looking like a services company to the street—which is not what we historically said we were.

• Increased risk. When we sell technology assets, the customer is ultimately responsible for achieving their target business results. With these MS contracts, we are taking on increased responsibilities. We are introducing new risks to the business. We may fail to meet contract SLAs and pay penalty clauses. The customer may be dissatisfied and cancel halfway through the contract. We might make an error in the customer environment and be sued.

• Channel conflict. Other executives beyond the CFO and CEO will start chiming in with their concerns. The executive who owns channel partners will be concerned that new MS offers conflict with partner offers. “We are stealing the bread from our partners’ mouths. They will jump to selling the product of our competitors.”

• Complex sales cycle. The sales executive may have concerns about the ability of sales reps to sell these complex MS offers. Also, by introducing an MS option, the customer selling cycle will most likely elongate—which is death to a sales force driven to close deals as quickly as possible and collect the cash.

• Smells like outsourcing. In the end, isn’t MS really just another word for outsourcing? And isn’t outsourcing one of the lowest-margin businesses in the technology industry?

The concerns and objections mount among executives, so there may be many reasons not to pursue this business. Yet, our point of view is that product companies should absolutely be pursuing MS opportunities when strategic customers begin knocking on the door for these services.

Just Say Yes

Despite the concerns listed here, we believe product companies should aggressively assess their opportunity to provide managed services for the following five reasons:

1. There is a compelling market opportunity for managed services.

2. Managed services is not IT outsourcing.

3. Managed services is an effective short-term defense against new XaaS competitors.

4. MS offers force the creation of new capabilities required to compete in the XaaS economy.

5. You could lose customer, after customer, after customer.

As cited previously in this book, market research firm Gartner signaled that worldwide IT spending was actually shrinking by 5.5% in 2015. 3 This opinion correlates with what we see in our T&S 50 data as we track the largest providers of technology solutions on the planet. Yet, the managed services market opportunity is exploding. Research firm MarketsandMarkets forecasts that the managed services market will grow from $107.17 billion in 2014 to $193.34 billion by 2019, at a compound annual growth rate of 12.5%. 4 For technology companies looking for growth, managed services becomes a compelling market opportunity.

Today’s MS offers are not like yesterday’s outsourcing offers. The traditional value proposition of IT outsourcing was simple: your mess for less. Outsourcers focused on cost reduction. As outsourcing became more competitive, margins for outsource providers eroded. But today’s MS offers from product companies are anchored on unique capabilities designed to unlock the full potential of a technology solution. Benefits go beyond cost reduction into other areas, such as revenue growth and risk reduction. Also, MS offers can be much more targeted to specific technologies or problem sets. Product companies are not asking to take over the entire IT operation for a customer. We are seeing an explosion of product companies wrapping a managed XaaS offer around their core products. This offer is creating differentiation in the marketplace when contrasted with product companies that are only interested in selling a product to the customer and then leaving. With your MS offer, you create value far beyond commoditized technical features by reducing total operational complexity.

When it comes to financial concerns about asset risk and revenue recognition, many manufacturers successfully use thirdparty financing to give customers more of the OpEx price model they crave without all the negative baggage. It helps them:

1. Minimize the financial risk of carrying infrastructure costs on their books. This tends to affect valuation for traditional companies.

2. Get immediate revenue recognition on the product portion of the deal.