The privacy and dignity of our citizens is being whittled away by sometimes imperceptible steps. Taken individually, each step may be of little consequence. But when viewed as a whole, there begins to emerge a society quite unlike any we have seen—a society in which government may intrude into the secret regions of man’s life at will.

—Justice William O. Douglas, Osborn v. United States1

It is difficult to imagine information more personal or more private than a person’s genetic makeup.

—Senator Edward Kennedy 2

Personal privacy is highly valued in most modern democratic societies, although there is a broad spectrum in the ways in which privacy is interpreted and protected among different countries. While generally thought of as simply the “right to be left alone,” the concept of privacy is highly complex, involving a number of overlapping personal interests. These include having control over our personal information and decision making and an ability to exclude others from our personal things and places. In the United States privacy protection has a long and complex history. Our government was founded on the principle that privacy—as well as related notions of dignity, due process, and liberty—serves as a check on the abuse of state power. These values are found not only in the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures but also in the Fifth Amendment’s guarantees of due process, equal protection, and freedom from self-incrimination, in the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel, and in the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. At the same time, the Constitution does not explicitly mention the word “privacy,” and it is routinely debated whether a general right of privacy is guaranteed by the Constitution.

Today “privacy law” in the United States does not consist of a single statute but instead is a complex array of protections that are dispersed among multiple sources, including constitutions, statutes, regulations, and common law. Statutory privacy protections evolved in direct response to technological development. Anita Allen notes, “The word privacy scarcely existed in the law before 1890, when new technologies contributed to an explosion of interest in privacy among intellectuals and lawyers.” Specifically, developments in printing and photography sparked considerable concern that “privacy would be lost in a world of unchecked curiosity, gossip, and publicity.”3 These concerns prompted two lawyers, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis, to publish a highly influential Harvard Law Review article that outlined their concept for a new “right to privacy” and served as a pillar for virtually all U.S. law and policy in the realm of privacy that was to come.4 Over the next few decades notions of “privacy” and a “right to privacy” became fixtures of the legal apparatus as a number of state courts—many of them drawing directly from Warren and Brandeis’s work—began to recognize a common-law privacy right and state legislators began to pass privacy-protection legislation. By comparison, it was not until 1965 that the U.S. Supreme Court expressly recognized a constitutional right of privacy in the landmark decision Griswold v. Connecticut.5

The fragmentation and ambiguities of privacy law have rendered the right to privacy somewhat vulnerable to the ebb and flow of historical conditions. Perceived threats to our civil order, in particular, have resulted in weakening privacy, as well as other civil liberties protections. Until recently we were able to assume that listening devices would not be secretly planted in our homes or on our telephone lines without a court warrant. That expectation has shifted after 9/11 through the enactment of the 2002 Homeland Security Act. That law gives the executive branch powers to execute warrantless wiretaps that invade the privacy of people whom it judges are a high security risk. Under the Terrorist Surveillance Program the U.S. National Security Agency is authorized by executive order to monitor phone calls and other communications involving a party believed to be outside the United States, even if the recipient of the call is on American soil. The Protect America Act of 2007 (signed into law on August 5, 2007) amended the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 to give congressional standing to warrantless federal wiretapping.

Just as the notion of “privacy” is rich in ambiguity, so too do notions of “genetic privacy” shift in different contexts. Although it is well established in law and policy that people’s expectation of privacy regarding their genome is not a frivolous concern, the standards for the way in which genetic privacy is treated vary widely from one context to the next. Broad public acknowledgment of the sensitivity, vastness, and potential misuses of genetic information ensured Congress’s ultimate passage of the Genetic Information and Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in 2008. This act provides certain baseline protections to help ensure that employers and health insurance companies cannot request, have access to, and make decisions on the basis of information in a person’s genetic code. Similar and in some cases more comprehensive protections have been passed by most state legislatures.

Although the notion that an employer or insurance company should not have access to our genetic information has been codified as law, law enforcement’s authority to collect DNA has ballooned over the last decade. Most recently people merely arrested by federal authorities and in select states, whether ultimately convicted or not, have been having their DNA routinely collected and permanently retained. Also, as discussed in chapter 6, law-enforcement officials are increasingly collecting DNA from individuals surreptitiously, the presumption being that if a person has “abandoned” his or her DNA, they have the right to collect it, analyze it, and perhaps use it as evidence against that person, all without a search warrant or the person’s knowledge or consent. Protection of DNA information in the criminal justice context appears to be operating under a different set of principles than that of health or employment. Can we retain an expectation of privacy in our DNA in health and employment contexts and lose that expectation when our DNA becomes an object of interest in the criminal justice community? If we are moving toward a double standard of privacy, one for medicine and another for forensics, we should know why, whether, and under what circumstances it is justifiable.

This chapter considers these and other questions about our privacy interests in our DNA. We begin with a discussion of what is so private about our DNA, including an analysis of the often-heard debate between civil libertarians and law enforcement over whether DNA is different from a fingerprint. We then discuss the role of the Fourth Amendment in protecting our privacy in our DNA. We trace the direction of the law in this area and identify some of the important questions that are likely to be addressed in the coming decade. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the particular hurdles for privacy advocates in protecting our genetic information in the law-enforcement context.

Genetic Privacy

The history and meaning of “genetic privacy” are in many ways parallel to those of “privacy” more generally. Just as the quest for privacy arose out of technological innovation at the turn of the nineteenth century, so too did concerns about “genetic privacy” stem from scientific and technological development—in this case the rise of molecular biology and computer science. A proliferation of DNA data banking and an increasing ability to extract information from DNA encouraged a shift in medical and behavioral research to focus more on genetic factors. Tissue repositories, such as newborns’ blood spots, that had been initially established back in the 1960s became gold mines of genetic information as genetic techniques evolved during the last decade of the twentieth century. The completion of the draft human genome sequence in 2000 brought questions of genetic privacy front and center as biotechnology companies sought to stake claims on genetic resources through the patenting of human genes and further proliferation of privately held DNA data banks.

What is our privacy interest in our DNA? Privacy experts generally distinguish four privacy concerns pertaining to DNA. First, there is physical privacy or bodily privacy. This comes into play at the point of DNA collection, whether it occurs for purposes of genetic testing, medical research, or criminal investigation. DNA can be collected by taking blood, either by a pinprick of the finger or a venal draw. The collection of blood is generally viewed as a highly intrusive process in the medical or research arena, where genetic information generally cannot be collected without the informed consent of the individual providing the sample. In the law-enforcement context DNA collection can occur voluntarily, forcibly, or surreptitiously. Surreptitious collection does not trigger physical privacy per se, since the DNA is collected off objects that are no longer on the person. When DNA was first introduced into forensic evidence around 1986, blood samples were the main source. More recently, in the law-enforcement context, DNA has been collected through use of a buccal swab. This method of collection is generally considered less intrusive than methods that involve the taking of blood.

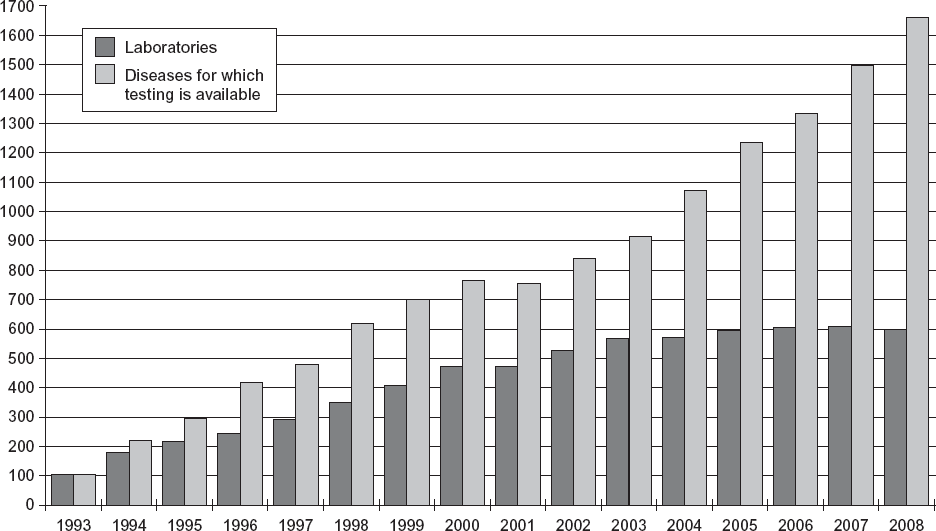

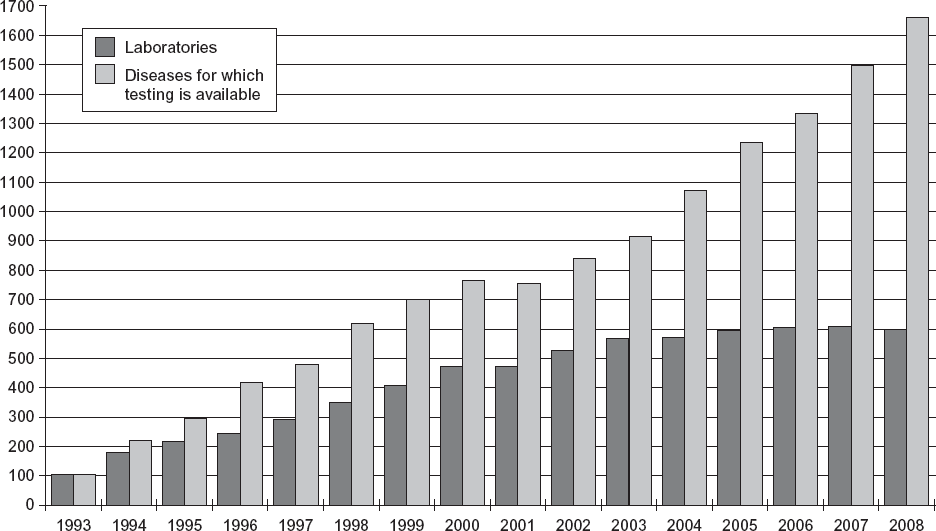

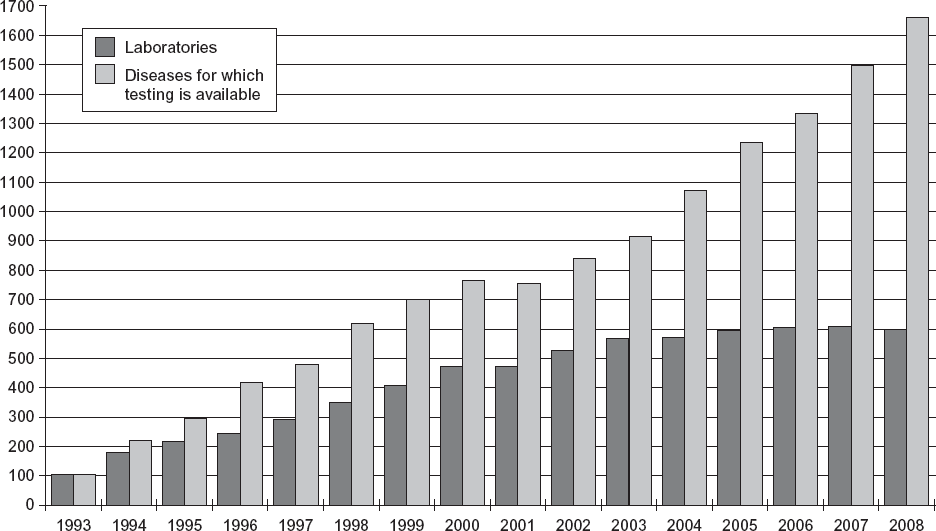

Second, genetic privacy refers to informational privacy. Information contained within our genome is considered highly sensitive because it can reveal a vast amount of information about us. The organization JUSTICE has described genetic information as “the most intimate medical data an individual may possess.”6 Genetic testing is currently available for over 1,700 diseases and abnormalities, with about 1,400 available in clinical settings, and this number continues to increase every year (see figure 14.1).7

Some genetic polymorphisms correlate directly with disease states, providing information about an individual’s current health status. But others are predictive—they correlate with a statistical predisposition to disease of familial disease patterns, providing information about the possibility that an individual may develop a disease over the course of his or her lifetime (see box 14.1). The fact that DNA contains information about an individual’s future health risks is the primary reason why some health law experts believe that DNA information is uniquely sensitive. George Annas has analogized DNA information to “a probabilistic, coded ‘future diary.’ . . . As the code is broken, DNA reveals information about an individual’s probable risks of suffering from specific medical conditions in the future.”8

In addition to providing medical information, genetic tests may reveal environmental and drug sensitivities as the field of pharmacogenetics advances. DNA sequence information may also contain information about behavioral traits, such as a propensity to violence or substance addiction, criminal tendencies, or sexual orientation.

Of course, our genetic status does not determine our medical future or our behavioral traits. That this information is probabilistic, not deterministic, makes the prospects that it might be released to third parties particularly dangerous. Concerns that this information could be used to discriminate against individuals seeking insurance and employment or to stigmatize individuals and families abound. There is some basis to this concern: in the 1970s several insurance companies and employers discriminated against individuals who were sickle-cell carriers, even though they would never develop the disease.9 More recently a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) against the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway Company revealed that the company was conducting genetic testing of its employees who had filed claims for work-related injuries based on carpal tunnel syndrome without their knowledge or consent. The company was asking those employees to provide a blood sample that was then tested for a rare genetic condition that had been associated with an increased risk of developing carpal tunnel syndrome. At least one worker was threatened with possible termination for failing to submit to a blood test. The case was settled quickly, with the company agreeing to all of the terms sought by the EEOC.10

FIGURE 14.1. Growth of genetic testing, 1993–2008. Source: GeneTests database (2008), www.genetests.org. Copyright University of Washington, Seattle.

At age 79 Nobel laureate James Watson donated his DNA for sequencing and eventual public access to the 3 billion base pairs that made up his genetic code. The codiscoverer of the chemical and physical structure of DNA had one restriction. Watson expressed his expectation of privacy regarding one segment of his genome, which he believed might reveal whether he has a predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease. One of his grandmothers contracted Alzheimer’s, and Watson figures that his chances are about one in four. The relevant sequence, Watson stated, should be kept secret from others and from himself.

Source: D. R. Nyholt, Chang-En Yu, and P. M. Visscher, “On Jim Watson’s APOE Status: Genetic Information Is Hard to Hide” [letter], European Journal of Human Genetics 17 (2009): 147–149.

What is perhaps unique about genetic information is that it both links us to and distinguishes us from all other human beings. As we discussed in chapter 1, our genetic code is thought to be unique—no two individuals, save perhaps identical twins, have the same DNA. At the same time, our genetic code is shared; it is part of our common heritage, passed on from one generation to the next. In this sense our precise genetic code is unique to each of us, but much of the information it reveals is likely to be shared by our relatives or entire groups of people. For example, if a woman undergoes genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2, the two genes that have been associated with hereditary forms of breast and ovarian cancer, the results of this test have implications not only for that individual woman but for all her close relatives.

This leads us to the third notion of privacy that is relevant to our DNA—familial or relational privacy. Because DNA is inherited, it can be examined to infer whether two individuals are related. In the case of parental linkages DNA testing is quite unambiguous, since 50 percent of our DNA was contributed by our biological father, and 50 percent by our biological mother. Sibling relationships can also be inferred, but beyond this, DNA testing is far more limited. Revealing an unsuspected personal biological relationship can have serious consequences for individuals or their families.

Similarly, DNA can reveal information about one’s ethnic origins. The Global Genome Project has introduced broad population groupings corresponding to a common set of genetic alleles called haplotypes. The extent to which our DNA contains these genetic loci gives population geneticists and anthropologists a clue to our geographical ancestry. Currently this information is of personal interest to some individuals who want to know what percentage of their inherited genome came from populations in Europe, Africa, Asia, North America, or Australia. However, this information can have significance beyond those interested in family genealogy. For example, American Indian heritage can sometimes be used in establishing tribal land rights. It can also be connected with social stigmas. When phenotype cannot reveal one’s ancestry, some would look to genotype.

Finally, DNA can provide information about whether an individual was physically present at a certain location. A person’s DNA found on a bedsheet at the scene of a crime is prima facie evidence that the person was at the location. In other words, DNA has implications for spatial or locational privacy. Traditionally, privacy has focused more on questions of who you are and what you are doing, and less on where you have been, where you presently are, or where you are going. What we do in our personal spaces, as well as whom we visit and where, should fall within our sphere of privacy. Increasing uses of radio-frequency ID tags (RFIDs), automated toll-payment systems, Global Positioning System (GPS) hardware and software, and surveillance cameras have directly challenged this notion of privacy. As an example, in 1996 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) required that all cell-phone manufacturers equip their units with location technology. As a result, it is now possible to position a cell-phone caller in a geographical location.

DNA Privacy in the Context of Law Enforcement

How do the notions of genetic privacy just discussed play out in the context of forensic DNA techniques and practices? What specific privacy concerns come into play when law enforcement collects, analyzes, and retains our DNA? And what protections are currently in place?

First, there is the bodily intrusion associated with DNA collection. As mentioned earlier, when DNA was first introduced into the criminal justice system, DNA was collected by drawing a blood sample. Recently law-enforcement agencies have switched over to collection by way of a buccal swab. The physical intrusion associated with swabbing the inside of an individual’s mouth versus drawing blood is clearly lower. Nonetheless, the inside of one’s mouth is still an intimate space, a body cavity that is not generally made accessible to others. Certainly it would be wrong to say that no privacy interest at all is raised in circumstances where an individual is forced to open his or her mouth so that a police officer can obtain a saliva sample. Aakash Desai, a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, who was forced to give a DNA sample after being arrested at a demonstration on campus protesting custodial layoffs and furloughs, as well as tuition hikes, described the experience as follows:

I felt violated when the government took my DNA. I felt like I was being burglarized and not the other way around. I feel like the government now owns my genes. This hurts my sense of self, and makes me feel sick to my stomach. Each swab was like being coerced into giving up part of my being. The government had already taken my possessions and clothing, now they were taking the building blocks of my own body. It seems like some ownership of myself has been lost and my privacy violated.11

As discussed in chapter 2, when DNA data banks were first created in the United States, DNA collection was limited to individuals who had been convicted of serious, violent crimes. Otherwise, law enforcement could only either collect DNA “voluntarily” or require a DNA sample from individuals in cases where they had a warrant supported by probable cause. Over the last 15 years this standard has slipped dramatically. Today the overwhelming majority of states are collecting DNA from all felons, as well as those convicted of some misdemeanors, and 14 states have approved legislation to take DNA from individuals merely upon arrest. At the same time, a number of “suspect databases” have been created as a result of DNA dragnets, where thousands of individuals have had their DNA collected without probable cause, without any privacy protections for the subjects, and with little, if any, oversight. Similarly, as is discussed in chapter 6, there has also been a trend toward collecting DNA surreptitiously from individuals, without their knowledge or consent.

After DNA is collected, it is analyzed for information. The analysis of DNA raises additional privacy concerns. When the FBI published its Legislative Guidelines for DNA Databases in 1991, the agency was explicit that the DNA records held by the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) should relate only to the identification of individuals, and that no records should be collected on physical characteristics, traits, or predisposition for disease. Currently all police departments that collect DNA samples create a forensic profile, containing information related to 13 loci. More recently some forensic laboratories have run Y-chromosomal short tandem repeats (Y-STR) typing on stored samples to help determine whether the source of that sample is likely to be a relative of the source of a crime-scene sample.

Law enforcement and other DNA database-expansion advocates have repeatedly characterized DNA profiles as nothing more than a “DNA fingerprint.” UCLA law professor Jennifer Mnookin has observed that early promoters of the use of DNA testing in the criminal justice system initially referred to DNA typing as “DNA fingerprinting” in an effort to enhance its appeal and to encourage judges and lawmakers to view DNA as nothing more than a more rigorous and precise technique than traditional fingerprints.12 For example, Assistant Attorney General William Moschella wrote in a letter to Senator Orrin Hatch, “By design, the information the system retains in the databased DNA profiles is the equivalent of a ‘genetic fingerprint’ that uniquely identifies an individual but does not disclose other facts about him.”13 DNA databasing advocates have underscored the DNA fingerprinting analogy with claims that the DNA profile used in the system consists merely of markers that correspond to repeating segments of so-called junk DNA. For example, in promoting the passage of the DNA Fingerprint Act of 2005, Senator Jon Kyl stated, “The sample of DNA that is kept in NDIS is what is called ‘junk DNA.’” 14 However, the “DNA fingerprinting” analogy is fundamentally flawed, most notably because DNA samples, which under current laboratory practices are permanently stored alongside the generated profiles, have the potential to reveal far more than a fingerprint. But the analogy is even mistaken as applied to the DNA profiles (see box 14.2). Although it is true that none of the CODIS loci have been found to date to be predictive of any physical or disease traits, this does not mean that such a correlation will not be found in the future. In addition, it is not necessary for any of the markers to correlate directly with any stigmatizing information for there to be a concern; the specter of discrimination and stigma could arise where one or more short tandem repeats (STRs) are found to correlate with another genetic marker whose function is known, so that the presence of the seemingly innocuous STR serves as a “flag” for that genetic predisposition or trait. A finding of this nature has already occurred; a study in England from 2000 found that one of the markers used in DNA identification is closely related to the gene that codes for insulin, which itself relates to diabetes.15

BOX 14.2 DNA as a “Fingerprint”: A Flawed Analogy

Perhaps the most common refrain provided by law enforcement in defense of the data banking of DNA is that DNA is no different from a fingerprint. The fingerprint analogy is deeply flawed. First, fingerprints are two-dimensional representations of the physical attributes of our fingertips. They are useful only as a form of identification. Fingerprints cannot be analyzed to determine whether two individuals are related. They cannot tell you your likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease or breast cancer or whether you are a carrier for cystic fibrosis. Nor can they be read to determine which version of the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene you have. There is no exponentially growing list of conditions that can be read from a fingerprint, or even significant research in this area.

Law-enforcement advocates underscore the fingerprint analogy by stating that the DNA profiles that are generated in DNA testing are merely “junk DNA”—that is, the 13 loci used in forensic analysis do not code for any phenotypic characteristics. But of course, they are focusing only on the DNA profile and quite blatantly ignoring the most significant privacy concern associated with DNA data banking, that of the DNA samples, which are stored indefinitely by forensic laboratories and have the potential to reveal almost unlimited information about ourselves.

Beyond this, even the reference to so-called junk DNA is misleading with regard to the DNA profile. Even noncoding regions of the DNA transmit more information than a standard fingerprint. Recent scientific studies have demonstrated that those regions are not devoid of biological function, as was once thought. And although they may never be found to have highly sensitive direct coding functions, they may very well be found to correlate with things we may care about and deem private. Since the completion of the Human Genome Project, no serious scientist refers to noncoding regions of DNA any longer as “junk.” In addition, simply by way of basic principles of inheritance, DNA profiles can be used to signal parent-child and other close family relationships. An examination of additional so-called junk DNA markers can provide more definitive analysis. Law enforcement’s recent ventures into familial searching are an indication that even criminal investigators recognize that DNA can provide far more information than a fingerprint (see chapter 4).

Source: Authors.

The analysis of crime-scene samples offers another example of how the privacy of DNA can be overlooked in the law-enforcement context. As discussed in chapter 5, there are currently no laws that we are aware of that prevent law enforcement from running any genetic tests of interest on DNA collected from the scene of a crime. Mining those samples for medical or other information that might be used to narrow a pool of suspects is certainly a possibility.

Finally, privacy concerns arise in association with the uses of the stored DNA samples and generated profiles. Those in the database are subjected to ongoing, repeated, suspicionless searches; every week the 7 million DNA profiles in CODIS are automatically searched against crime-scene profiles. In a sense, one’s inclusion in the database makes him or her an automatic suspect during his or her lifetime for any future crime. And as we have discussed in chapter 4, recent uses of forensic DNA databases to search for “partial matches” that may implicate a family member of an individual in the database make the privacy intrusion of repeated searches apply not only to the individuals in the database but also to all of their close relatives. There is also a real but neglected risk of being falsely accused of a crime that comes from being in the database. We discuss the potential sources of contamination and error in detail in chapter 16.

Perhaps the most significant privacy concerns arise about the long-term storage of the original DNA samples. Although the information contained in the DNA profile is necessarily limited, every forensic laboratory in the country currently holds on to the biological samples from which the DNA profile was generated, and, as discussed earlier, these can be mined for an increasing amount of highly personal information. Thus criminal justice agencies around the country have all the medically relevant information on a profiled individual that can be gleaned from one’s DNA. So long as the samples are retained, there exists the possibility that they could be disclosed to or accessed by third parties or used in ways that result in the disclosure of highly confidential information or for malicious or oppressive purposes. And because genetic information pertains not only to the individual whose DNA sample is stored but to others who share in that person’s bloodline, potential threats to genetic privacy posed by the samples’ long-term storage extend well beyond the millions of individuals who are currently in the system. Jean McEwen has warned: “The unique composition of forensic DNA banks . . . will make those repositories a nearly irresistible source of samples for behavioural genetics research or testing . . . without the informed consent of those from whom the samples were taken.”16

Federal policy limits disclosure of DNA information “for law enforcement identification purposes,” but of course there is nothing about “identification purposes” that prevents law enforcement from mining stored samples for information that is restricted to noncoding regions of the DNA. State laws provide little, if any, additional protection against unrelated use of DNA obtained for investigative purposes. Four states are silent on this issue, and most others parrot the federal standard. According to Mark Rothstein and Sandra Carnahan, “Many state statutes allow access to the samples for undefined law enforcement purposes and humanitarian identification purposes, or authorize the use of samples for assisting medical research.”17 The FBI has also conceded that most states do not have protections against the dissemination of DNA samples.18 Most states limit uses of the database to those that are “authorized,” but it appears to be left to the discretion of law enforcement to determine what is an “authorized use.” Only eight states expressly prohibit the use of a DNA database to obtain information about human physical traits, predisposition to disease, or medical or genetic disorders, and Alabama explicitly authorizes the use of DNA information for medical research. Some states explicitly prohibit the use of DNA samples and profiles for purposes other than law enforcement, but this, of course, does not appear to prevent law enforcement from mining the DNA for additional information. Other states are either vague or have laws that permit the restricted use of their DNA forensic data banks. About 15 states have statutes that expressly permit the use of data banks for medical research and humanitarian needs.19 Twenty-four states allow DNA samples collected for law-enforcement identification to be used for a variety of other non-law-enforcement purposes.20 Massachusetts’s law, for example, contains an openended authorization for any disclosure that is, or may be, required as a condition of federal funding and allows the disclosure of information, including personally identifiable information, for “advancing other humanitarian purposes.” Two states prohibit the use of DNA samples in medical research.21 Thirty-four states have statutory language authorizing the use of databases for statistical purposes related to improving law enforcement, such as developing better probability figures on false matches.

There is no national policy governing the retention of forensic DNA samples, and state laws vary on policies for destroying DNA samples and removing the profiles from the database in cases where convictions are overturned or charges are dismissed. Where sample and profile removal are possible, the burden is most often placed on the individual to have his or her records removed, rather than on the state. Wisconsin is the only state that requires that biological samples be destroyed after typing, but it appears that to date, no such destruction has occurred.

Some are dubious that forensic DNA data banks will ever be used by medical or behavioral scientists.22 David Kaye states unequivocally that behavioral genetics researchers who desire to use the samples in CODIS (and in state and local databases feeding CODIS) are excluded from doing so: “Behavioral genetics researchers who come knocking on the doors of state or federal administrators for the DNA of convicted offenders will find them locked, and the key cannot be located within the disclosure and usage provisions of the current database laws.”23 Their research would not qualify under the federal DNA database statute, which states that CODIS must be used for law-enforcement identification purposes only.24 This would include developing population statistics and validation criteria where all identifiers are removed, but not behavioral genetics or medical research. Thus, even if scientists had an interest in using the database, according to Kaye, in most cases they could not get access. Currently, no state explicitly allows DNA samples from the forensic database to be used in research on predisposition for disease or in behavioral research.25 The Alabama law states that the DNA population statistical database, which shall include “individually identifiable information,” can be used “to assist in other humanitarian endeavors including, but not limited to, educational research or medical research or development.”26 Davina Bressler implies that since the Alabama law prohibits research with DNA samples from the database of individually identified records, therefore, any such anonymized research would not be of any value for medical or behavioral science. In addition, some of those states that allow the DNA samples to be used for “other humanitarian purposes” refer more specifically to identifying human bodily remains or missing individuals, especially lost or kidnapped children. Therefore, these allowances were most likely not intended to open the database to broad medical or behavioral research.

To date, there is no evidence that any state has thus far permitted its forensic DNA data banks to be used for medical or behavioral research. In her analysis of the 50 state statutes Bressler concludes:

A more careful reading of the statutes reveals that only one state allows for medical research with records (and they must be anonymized) and that no state allows for medical research with samples. The repeated assertions that many states allow researchers to use DNA samples from convicted offenders to be used in medical research—with or without consent—are incorrect.27

Although these arguments are noteworthy, it is also the case that current statutory restrictions are at best unclear, untested, and open to interpretation. Perhaps more important, statutes can be repealed or amended. If there is legitimate knowledge to be gained, will current restraints hold back the scientific pressures for access to public data? For example, if genetic screening of stored DNA samples could reveal whether individuals were “genetically predisposed” to criminal offending, would it be allowed? Consider, for example, a subset of felons convicted of pedophilia. If the database for that group of felons contains information about convictions, medical history, family associations, and profiles of crime victims and also has the pedophile’s complete genome from a biological sample, there almost certainly would be medical and/or behavioral geneticists who would want to pursue the question whether pedophilia has a genetic basis. Although pedophiles appear to be highly recidivistic—having almost a compulsion suggesting a biological mechanism—that is a huge step from a genetic mechanism. There is also the prospect that a genetic-based crime-control strategy could ultimately include mandatory genetic screening from birth to identify individuals predisposed to certain so-called undesirable behaviors. Those who support such access see scientific merit in research that links genes to impulsiveness, aggressiveness, pedophilia, or novelty seeking and believe that ethics review boards can adequately oversee such uses of databases.28

In England, where, as is the case in the United States, the government contracts out some of its DNA analysis, concerns have been raised about private companies sharing DNA samples collected for forensic purposes with researchers. In 2006 the London Observer reported that a “private firm has secretly been keeping the genetic samples and personal details of hundreds of thousands of arrested people.” The British Home Office has given permission for 20 research studies using DNA samples from the National DNA Database (NDNAD). The goal of some of the studies is to determine whether it is possible to predict a suspect’s ethnic background or skin color from his or her DNA.29

A report issued by the public-interest group GeneWatch UK noted that British researchers who have access to the national DNA forensic database

do not have to seek consent from participants or the approval of independent ethics committees to carry out their research. They have only to seek permission from the NDNAD Board. . . . Some of the research could be highly controversial, for example research on ethnicity and race . . . or research on “genes for criminality.”30

GeneWatch UK has gone on record proposing that any research on the NDNAD should be reviewed by an independent ethics board to ensure that the research is morally and socially acceptable and that consent should be received in advance of the research by those whose DNA profile or biological source is part of the study.31

It is clear that the only sure way to prevent any misuses of the stored samples is to destroy the samples themselves. No one proposes destroying the crime-scene samples, since these might be the only evidence from the scene of the crime and the accuracy of the analysis could be contested. However, individual samples collected from known offenders or arrestees are another matter. A number of advocacy organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and ethics advisory committees have proposed destroying the known-offender biological samples after DNA typing is completed as a way of preventing possible misuse. Law enforcement has argued that the samples need to be retained for reasons of quality assurance (most significantly for retesting a sample in case of a mix-up) or to rerun the samples for purposes of upgrading the system (for example, for profiling a larger number of genetic markers). The U.K. Human Genetics Commission’s 2009 report found these arguments unpersuasive:

We cannot see any need for long-term retention of subject samples, for the following reasons: if the identity and whereabouts of the subject are known, it will be possible, and not disproportionately expensive or difficult, to obtain a new sample for analysis; conversely, if the subject’s whereabouts are not known, having a DNA sample is unlikely to assist in locating them; and finally, the argument that there may be a future need to upgrade the profiles by analyzing more loci is unconvincing.32

Fourth Amendment Protection: Trends in Case Law on DNA Data Banking

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause.” For nearly 200 years courts limited the scope of this amendment by holding that it protected only against physical intrusions—for example, the entry into a house or the seizure and examination of private papers. Thus in 1928 the Supreme Court held that government wiretapping of a telephone call did not constitute a “search” or a “seizure” and was therefore not even subject to any Fourth Amendment scrutiny.33

This changed in 1967 when that same Court decided Katz v. United States. Charles Katz was convicted in California of illegal gambling. The crucial evidence against him was a series of recordings that the FBI had made, without a warrant, of calls Katz had made from a public pay phone booth in Los Angeles. Katz challenged his conviction, arguing that the recordings could not be used against him, and the case made its way up to the Supreme Court. By a vote of 8 to 1 the Court overruled its prior cases and ruled in favor of Katz, holding that the government had violated Katz’s Fourth Amendment rights by secretly recording his private phone calls without a warrant.34

Katz extended the reach of the Fourth Amendment beyond physical intrusions. Writing the majority opinion, Justice Potter Stewart stated that “the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, when in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection. . . . But what he seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected.”35 The Court refused to continue to take the “narrow view” that the “search and seizure” language in the Constitution was meant only to protect against physical penetration of private, delineated space or objects and ruled that the Fourth Amendment protects people’s concept of personal privacy: “The fact that the electronic device employed to achieve that end did not happen to penetrate the wall of the booth can have no Constitutional significance.”36

The Katz standard provides the controlling test for determining whether government action constitutes a Fourth Amendment search: first, that a person have exhibited an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy; and second, that the expectation be one that society would recognize as reasonable. Government actions that intrude into these “reasonable expectations of privacy” are searches and therefore constitutional only if the government can show that they are reasonable. The Fourth Amendment also prohibits unreasonable seizures, whether those seizures be of property or of the person (or his or her bodily tissue).

How does the concept of privacy as articulated in Katz apply to DNA data banking and forensic DNA applications? Because the Fourth Amendment protects against “unreasonable” searches and seizures, courts must assess not only whether a search has occurred but also the reasonableness of that search. Is the taking of DNA a “search”? Is it a “seizure”? If so, is it reasonable under any circumstances? Is a warrant required? Do we have an “expectation of privacy” in our DNA? How is that expectation balanced against the public benefits of DNA collection for purposes of criminal investigation?

The Taking of DNA Constitutes a Search and a Seizure

A law-enforcement officer’s sticking a needle into a person’s arm for a blood sample against his or her will without evidence of suspicion is generally regarded as a violation of his or her privacy. The limits of taking blood samples forcibly were the issue in the U.S. Supreme Court case Schmerber v. California (see box 14.3), where the majority stated, “The interests in human dignity and privacy which the Fourth Amendment protects, forbids any such intrusions [blood samples] on the mere chance that desired evidence might be obtained.”37 Although the Court in Schmerber found that a blood test presents only a minimal intrusion, it nonetheless held that in order for the police to take a biological sample from an arrestee, they must either have a warrant or have probable cause to think that the sample will yield evidence of a crime and that exigent circumstances exist that make it impracticable to procure a warrant. The Court has found that similar collections of bodily fluids or tissues for analysis—such as urine tests,38 breath tests,39 and fingernail scrapings—are similarly privacy intrusions that constitute a “search.”40

Armando Schmerber was taken to the hospital after he had been involved in a traffic accident. The hospital performed blood tests involuntarily, which police used to determine whether Schmerber had been driving while intoxicated. He argued that the police had invaded his privacy by obtaining his blood and testing its alcohol level. The court ruled that the defendant exhibited physical features that gave police probable cause to believe that he was intoxicated and that police did not have time to obtain a warrant. Police argued they were under exigent circumstances that justified their warrantless search. The court agreed: “We today hold that the Constitution does not forbid the State minor intrusions into an individual’s body under stringently limited conditions, [which] in no way indicates that it permits more substantial intrusions, or intrusions under other circumstances.”a

a Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966).

Source: Authors.

Following the analysis in Schmerber, lower courts have consistently held that the taking and analysis of DNA constitutes a “search.” Most courts have focused, as in Schmerber, on the physical intrusion associated with the collection of DNA by way of either a blood draw or a buccal swab. Considerably less attention has been paid to the informational privacy aspect of DNA collection and analysis and the notion that the DNA profiles are subjected to ongoing, repeated searches, although some courts have acknowledged this aspect as well.41

Generally speaking, the Fourth Amendment requires that searches be supported by a warrant, issued by a magistrate only upon a factual showing that the search will likely uncover evidence of a crime. Over the years the courts have carved out a number of exceptions to this warrant requirement (for example, allowing police to stop and frisk people whom they have reason to think are armed and dangerous, and to search cars when they have probable cause to think the car contains contraband or evidence of a crime). Generally, the more intrusive the government action, the higher its burden is to justify that action. Thus a brief traffic stop requires less justification than does a search, and some searches—such as those requiring dangerous surgery—are per se unreasonable. But even for the most minor intrusion, the law is clear that searches and seizures for general law-enforcement purposes must be supported by some level of individualized suspicion.

When DNA was first introduced into forensic evidence around 1986, blood samples were the main source. As forensic DNA testing has shifted from blood draws to buccal swabs, its perceived level of intrusiveness has dropped precipitously. Nevertheless, courts have generally found that forcible collection of DNA by use of a buccal swab constitutes a “search” requiring a warrant or at least probable cause. Furthermore, because the later analysis of the sample reveals information about a person’s genetic makeup—information that we as a society consider private—that analysis is itself a search.

Evolving Case Law on DNA Data Banks

Although there is little question that DNA collection and analysis constitutes a “search,” all twelve circuits have nonetheless upheld mandatory DNA collection statutes that apply to convicted offenders. In so doing, the courts have judged the reasonableness of the search by balancing the interests of the government against the privacy of the individuals involved. In weighing these interests, some courts have found that the government’s interest in maintaining a DNA database of convicted offenders is one of “special needs, beyond the normal needs for law enforcement.” These cases follow the reasoning in Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Association, where the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the collection of blood, breath, and urine samples from employees in safety-sensitive positions for purposes of randomized drug testing, without a warrant, probable cause, or individualized suspicion. Although the Court recognized that these tests were “searches” that invaded the defendants’ reasonable expectation of privacy, it nonetheless upheld the testing program on the notion that it was not for general law-enforcement purposes but, instead, to investigate railroad accidents and to prevent injuries.

The Second, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits have each relied on the special-needs exception in upholding state DNA databasing of convicted offenders. Rothstein and Carnahan have questioned this line of reasoning as applied to database statutes, since it is hard to understand the purposes of DNA collection in these contexts—identification, investigation, and prosecution of criminals—as anything other than law enforcement.42 After all, the mission statement of CODIS explicitly states that it was created for law enforcement purposes, and many of the state statutes describe the database as a “powerful law enforcement tool.” Although the courts that have applied the special-needs exception have, in some cases, acknowledged that DNA testing of inmates is ultimately for a law-enforcement goal, they have concluded that this falls within the special-needs analysis because “it is not undertaken for the investigation of a specific crime.”43

In recognizing the inherent tension in applying the special-needs exception to a law-enforcement database, some courts have avoided this line of reasoning and have instead upheld convicted-offender databases on the notion that persons under supervision of the criminal justice system following conviction have a “reduced expectation of privacy.” For example, in United States v. Kincade a majority of the Court explicitly ruled that the special-needs exception could not justify DNA-collection schemes. Nonetheless, the court found that “parolees and other conditional releasees are not entitled to the full panoply of rights and protections possessed by the general public.”44 Just as the police can enter and search the house of a person on parole without a warrant or even any reason to think the resident has done anything wrong, they can intrude upon his genetic privacy and bodily integrity.

Courts that have followed this general balancing scheme in upholding DNA data banks have tended to analogize DNA testing to “fingerprinting,” focusing narrowly on the use of DNA for “identification,” and have largely ignored potential uses or misuses of stored biological samples. In Rise v. Oregon, for example, the Ninth Circuit found that once a person is convicted, one’s identity is a matter of state interest, and the offender “has lost any legitimate expectation of privacy in the identifying information derived from blood sampling.”45

The Question of Innocent Persons: Arrestees, Suspects, and Family Members

Although it appears that the question whether DNA can be collected and permanently stored from convicted felons is thoroughly decided, the issue whether the reaches of DNA data banks that extend to innocent persons can withstand constitutional muster is another matter. The court rulings that have upheld DNA data banking of convicted offenders do not provide law enforcement a blanket justification to collect and use DNA without limits. As a matter of policy, for a society that values freedom and individual privacy, the notion that innocent individuals should not have DNA taken without their knowledge or consent or retained permanently in a database, seems consistent with other protections against law enforcement’s unfettered acquisition of personal information. But states and the federal government are giving law-enforcement agencies authority to override personal privacy as DNA data banks are expanded to arrestees, DNA is collected surreptitiously in the course of investigations, and DNA databases are mined for partial matches.

In following the reasoning of the courts in upholding DNA statutes of convicted felons, it is hard to see how the routine, forcible collection of DNA from arrestees—who are innocent under the law—could be tolerated. To date, of the four courts that have considered this issue, three have determined that the routine collection of DNA from arrestees is unconstitutional. In 2006 Minnesota’s Court of Appeals held that taking DNA from juveniles and adults who have had a probable-cause determination on a charged offense but who have not been convicted violates state and federal constitutional prohibitions against unreasonable searches and seizures. Similarly, in 2009 the federal District Court of Western Pennsylvania, consistent with the long-standing recognition that arrestees enjoy the presumption of innocence and give up only those rights whose infringement is necessary to ensure jail security and safety, struck down the federal law allowing the testing of arrestees. The court found that “requiring a charged defendant to submit a DNA sample for analysis and inclusion in CODIS without independent suspicion or a warrant unreasonably intrudes on such defendant’s expectation of privacy and is invalid under the Fourth Amendment.”46 In contrast, the Virginia Supreme Court upheld DNA collection from suspects alleged to be violent felons, finding that because DNA can be used to identify a person, taking DNA from an arrestee “is no different in character than acquiring fingerprints upon arrest.”47

As is discussed in chapter 6, within certain limits, U.S. courts have upheld methods of law-enforcement authorities in obtaining nonconsensual DNA samples without warrants. Sometimes police use a ruse to obtain a suspect’s DNA. Other times police investigators shadow an individual until they can retrieve a discarded object, including the individual’s sputum on the sidewalk, with the desired DNA sample. If DNA privacy is to make any sense, then we have to distinguish between the abandoned object and the information that can be deciphered by a technical expert in the DNA left on the discarded object. We should not lose our expectation of privacy for our DNA, even though we have given up the object carrying it.

To date, no court has considered whether the initial collection of DNA or the subsequent use of familial searching violates the privacy interests of convicts’ family members, who have not forfeited their privacy rights. In the case of familial searching the identification and analysis of partial DNA matches broadens the scope of a DNA database, subjecting family members to genetic surveillance. This means that they are more likely to be suspected of a crime they did not commit. Whether the privacy interests of family members in these situations could rise to the level of constitutional protection seems uncertain, at best, particularly since—as in the case of surreptitious sampling—there is no initial physical intrusion associated with the search of the family member’s DNA.48

Challenges for Privacy Advocates

As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, there are significant differences between the ways in which genetic privacy is treated in the medical and research context and in the law-enforcement context. There is a growing consensus and near unanimity that, beyond the person’s caregivers, the privacy of an individual’s medical genetic information should be protected. Many states and the federal government have passed legislation that protects individuals from unauthorized access to and use of medical genetic information. Also, the confidentiality of genetic information, regardless of how it is obtained, is generally accepted among professional societies and bioethicists. The American Society of Human Genetics is on record stating that “genetic information, like all medical information, should be protected by the legal and ethical principle of confidentiality.”49 In a similar vein, bioethicist George Annas noted that “the DNA molecule itself can be viewed as a new form of medical record. It is a source of medical information, and like a personal medical record, it can be stored and accessed without the need to return to the person from whom the DNA was collected for authorization.”50

However, the standards in forensics for protecting privacy are operating on a different playing field than those in the medical and research communities. While informed consent is the standard for the collection and storage of genetic information in the latter context, the law-enforcement situation can be seen as an evolving free-for-all, where DNA is starting to be collected almost at the whim of a given police officer.

This bifurcated system is not unlike what is seen in the United Kingdom, although, interestingly, a new law in the United Kingdom prohibits non-law-enforcement agents from acquiring and analyzing a person’s DNA without consent (see box 14.4). The rationale for the law was articulated by Baroness Helena Kennedy, chairperson of the United Kingdom’s Human Genetics Commission:

Until now there has been nothing to stop an unscrupulous person, perhaps a journalist or a private investigator, from secretly taking an everyday object used by a public figure—like a coffee mug or a toothbrush—with the express purpose of having the person’s DNA analyzed. Similarly, an employer could have secretly taken DNA samples to use for their purposes. This sort of activity is a gross intrusion into a person’s privacy and we are very pleased that the Government has now taken the Human Genetic Commission’s advice and made it illegal to take and analyse DNA in this way, without the person’s consent.51

Under the United Kingdom’s Human Tissue Act of 2004 (which became effective on September 1, 2006) individuals cannot obtain and analyze a person’s DNA without his or her consent. Violation of the law is punishable by up to three years in prison or a fine or both. The law does not apply to law enforcement. The British Parliament enacted the law to keep amateurs from breaching the genetic privacy of individuals by analyzing a person’s so-called abandoned DNA.

Interestingly, although this law has significantly bolstered privacy protections for individuals in light of a burgeoning genetic testing industry, it further bifurcated the United Kingdom’s system of DNA privacy. The law, with its clear exception for law enforcement, underscores that the rules for the police are separate from those for everyone else. In the context of law enforcement, DNA is open for taking.

Source: Authors.

In contrast, the United States has no restrictions on analyzing DNA from so-called abandoned objects, obtained by stealth or by a ruse, where no informed consent is required. A New York Times report titled “Stalking Strangers’ DNA to Fill in the Family Tree” describes the current attitude regarding the DNA we continuously shed from our bodies or from personal products we discard. Our laws and policies have not adequately addressed the complex privacy issues that are raised by the growth of medical and forensic interests in people’s DNA. The concept of “abandoned DNA” implies that we have no privacy interests in those reservoirs of our genetic code that are discarded or shed continuously and ubiquitously. Currently the default position for police is that DNA unattached to our bodies is unrestricted for anyone’s taking:

They swab cheeks of strangers and pluck hairs from corpses. They travel hundreds of miles to entice their suspects with an old photograph, or sometimes a free drink. Cooperation is preferred, but not necessarily required to achieve these ends. . . . The talismans come mostly from people trying to glean genealogical information on dead relatives. But they can also be purloined from the living as the police do with suspects. The law views such DNA as “abandoned.”52

Can medical and forensic privacy of DNA be conceptualized into a coherent set of principles, or do we have to live with two independent and incompatible systems?

Part of the challenge for privacy advocates lies in the nature of DNA itself. The fact that DNA is everywhere means that it is fairly easy to collect, whether openly or surreptitiously. The level of intrusion for collection, as a result of the development of buccal swabs, is also minimal, or at least less than for blood collection. DNA’s stability means that it can be retained more or less indefinitely so long as it is kept in suitable conditions. The cost of DNA analysis is declining. Generally speaking, we have witnessed a slow and steady erosion of privacy protections in the United States. All these factors make it difficult for privacy activists to effectively oppose the expansion of DNA databases.

At the same time, in the law-enforcement context, very little emphasis and attention have been placed on the informational privacy aspect of DNA collection. Early court cases failed to acknowledge the full scope of privacy concerns that can arise in the amassing and long-term storage of DNA samples, focusing almost exclusively on the initial physical intrusion associated with DNA collection. The “fingerprinting” analogy, meanwhile, has been etched in the minds of policy makers, eager to promote a seemingly high-tech, objective approach to “fighting crime.”

Public attitudes and social policies about genetic privacy are evolving. There is ample evidence that people have an expectation of privacy of the genetic code that makes up their cells, at least the fraction of 1 percent of the code that reveals information about their physical or psychological being. A growing list of federal and state privacy protections has made it clear that we have a right to privacy in our genetic makeup in the medical and employment contexts. But in the context of the criminal justice system a relatively new technology of DNA profiling appears to be operating according to a different and shifting set of rules as the reach of DNA data banks is expanded to ever more categories of innocent people.

Public anxiety about open access to genetic information is likely to continue to be exacerbated by the rapidly growing field of behavioral genetics. Two recent studies illustrate this point. One study linked a gene mutation in men to marital discord and infidelity. According to a behavioral geneticist at the Karolinska Institute, “Men with two copies of the allele [gene variant] had twice the risk of experiencing marital dysfunction, with a threat of divorce during the last year, compared to men carrying one or no copies.”53 A second study found a gene that the authors claim can predict voter turnout.54 Whether or not these research results are replicated and validated, it is reasonably certain that people would not want such information open to anyone who can sequence their DNA from an abandoned paper cup.

Genetics has become the new prism through which science reveals personal identity, behavior, and medical prognosis. Undoubtedly, some of these claims will prove false or simplistic. Others may survive skepticism. But there is little doubt that genetic privacy will become an increasingly important component of personal privacy. Eventually the courts will have to grapple with the discordance that is emerging in our laws and policies and incorporate the public’s expectation of genetic privacy within criminal justice under the umbrella of the Fourth Amendment, as Congress has begun to do with medical genetic information. Until then, the question whether we have any privacy at all in our DNA hangs in the balance.