Next to the arthropods, the molluscs are the most abundant and successful phylum of animals on Earth, with over 130,000 living species of snails, slugs, clams, scallops, oysters, squid, octopus, and their relatives (fig. 16.1). Except for slugs, squid, and octopus, most molluscs have hard shells made of calcium carbonate, usually calcite but also sometimes aragonite (mother of pearl), which makes them easy to fossilize. Their fossil record is excellent, better than that of any other marine fossil group. More than 60,000 fossil species are known, and more paleontologists work on molluscs than on any other invertebrate animal group, most of them specialists in just one class, such as the snails or clams or ammonoids.

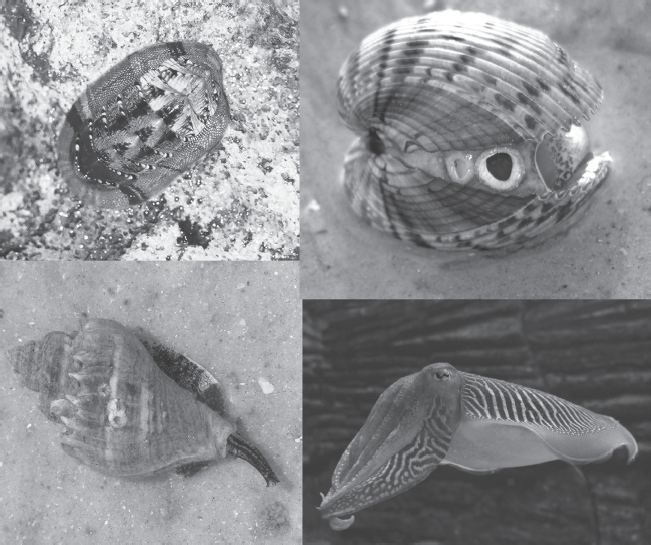

Figure 16.1 ▲

Molluscs come in many different shapes and forms, from the creeping chitons of the tide pools (upper left), to the two-shelled bivalves such as clams and oysters and their kin (upper right), the spiral-shelled snails or gastropods (lower left), and the highly intelligent, fast-moving, tentacled cephalopods such as this cuttlefish (lower right). (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Molluscs are also important to human culture. Seashell collecting is not only a popular pastime now but has been for centuries, and in many cultures shells were used as money (“wampum” to Native Americans). People in many cultures eat a wide variety of “shellfish,” especially clams, oysters, and scallops, as well as abalone, conch, squid (calamari), octopus, and land snails (escargot). Nearly all prehistoric peoples who lived near the coast were big mollusc eaters, as shown by their large garbage heaps known as shell middens. Over 2 million tons of squid and octopus are harvested each year, along with enormous volumes of clams, oysters, and scallops. In the United States alone, more than 220 million pounds of clams, oysters, and scallops are eaten each year. Finally, certain molluscs (especially oysters) produce a valuable gem, the pearl, from the aragonite that their mantle secretes to any irritant that gets inside the mantle cavity.

In addition to being extremely diverse, molluscs have come to inhabit almost as many ecosystems as the arthropods. They live in every marine setting from the deepest ocean to the intertidal zone, and some are planktonic (float on the open sea). Many different freshwater clams and snails are known, and land snails are well adapted to being away from water.

Molluscs achieve this flexibility despite having a rather limited body plan. Nearly all molluscs are built around a softy fleshy body with a muscular foot that helps propel them, and with a shell on their back. Their body is covered by an organ called the mantle, which secretes their shell. Most molluscs have a simple digestive tract that runs from mouth to anus, paired gills for breathing in water, and simple versions of most other systems, including circulatory, excretory, reproductive, and other systems. Although most molluscs tend to be small, some are huge. The giant squid allegedly reaches about 50 feet (18 meters) in length, the giant clam is over a meter long, and the giant marine snail Campanile has a shell more than a foot long.

The simplest molluscs are the limpet-like monoplacophorans, which have a cap-shaped shell over their back, but they still have segmented muscles, gills, and other body parts just like their relatives, the segmented worms. Monoplacophorans were the most common molluscs in the Early Cambrian. It was thought that they had become extinct by the middle Paleozoic, but living examples of monoplacophorans were found in deep oceanic trenches in 1952.

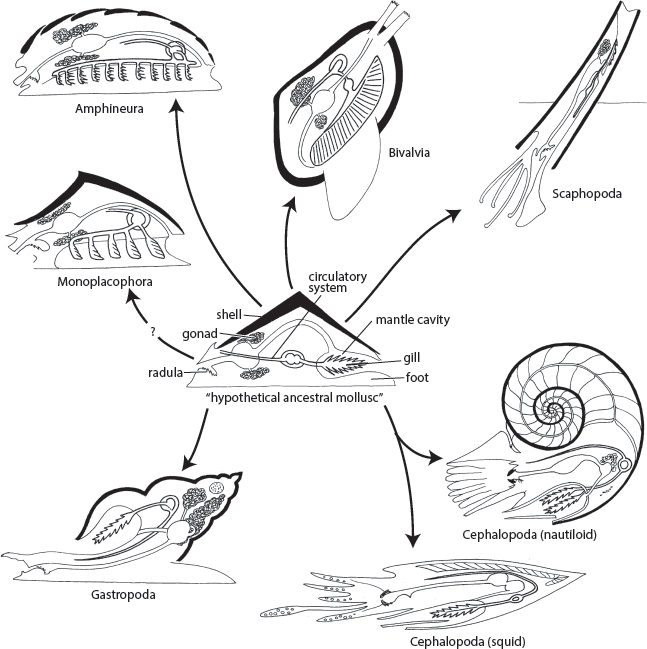

From this basic body plan of the “hypothetical ancestral mollusk,” the various classes of molluscs have modified their anatomy to live in different ways (fig. 16.2). Among the least modified are the chitons (class Polyplacophora or Amphineura), which are familiar denizens of tide pools around the world (see fig. 16.1, upper left). In the intertidal zone, they stick to rocks with their broad muscular foot, and they have modified the primitive limpet-like shell by subdividing it into eight plates, which enables them to bend and flex their body to fit around curves as they cling to rocks. Like limpets, they spend their lives slowly creeping along, scraping algae with their ribbon of tiny teeth made of iron oxide, or magnetite. In some islands in the tropical Pacific, the chitons have scraped so much rock away from the tide-pool zone that the islands are on pedestals.

Figure 16.2 ▲

Radiation of the molluscs from the “hypothetical ancestral mollusc.” (Redrawn by Mary Persis Williams from several sources)

Another minor group of molluscs are the tusk shells (fig. 16.2), or scaphopods (class Scaphopoda). Most of them have a long conical shell with a hole at the tip that resembles an elephant tusk, hence their name. These animals burrow in the shallow sand in the near-shore zone with their open tip exposed, allowing them to filter ocean water and trap food while releasing their waste products. In addition, a number of extinct molluscan classes, such as the rostroconchs, are rarely fossilized and are mostly known from the Cambrian, when molluscan evolution was undergoing its “experimental” stage.

Three classes of molluscs make up the bulk of both the living and fossil species and deserve detailed discussion. These are the Gastropoda, the Bivalvia, and the Cephalopoda.

CLASS GASTROPODA (SNAILS, SLUGS, AND NUDIBRANCHS)

The Gastropoda are by far the most diverse of all molluscan classes, with over 100,000 species, making up about 80 percent of the living molluscs. The simplest molluscs are the limpets and their relatives, which have not changed that much from the monoplacophorans and other archaic molluscs. They are subdivided into many groups. Most of the marine snails are known as prosobranchs (“forward gills” in Greek), and they rotate their gills from the rear to over their head during larval development. The bubble shells, plus the snails that have lost their shells (sea hares, sea slugs, nudibranchs), and the planktonic pteropods are opisthobranchs (“backward gills” in Greek). The third group is the land snails and slugs, which have turned their gill cavity into an air-breathing organ; they are known as pulmonates (“lunged” in Greek). The opisthobranchs and pulmonates have only a limited fossil record, so I will focus on the abundant shell record of prosobranchs here.

Among the prosobranchs, the simplest are the limpets and abalones, which are adapted to sticking to hard surfaces and scraping off algae using the ribbon of tiny teeth in their mouth. But the simple, cap-shaped limpet shell does not allow for much in the way of evolutionary innovation, so gastropods soon evolved into other forms.

If a conical shell gets too large, it is much more stable to carry if it is coiled into a spiral, and nearly all of the other gastropods have evolved some variation on a coiled shell. The basic terminology of a coiled shell is quite easy to remember (fig. 16.3). Each turn of the shell around the axis is called a whorl. The number of whorls and the width and rate of turning of the shell are diagnostic of certain groups of snails, and they change as the snail grows larger in its shell and adds more material to the leading edge. The point of the top of the shell is the apex, and the shell can be considered high-spired if it is long and pointed, or low-spired if it is shorter and stubbier. If you see the shell broken open, the internal column formed by the junction of the inner part of each whorl is called the columella. The opening (aperture) of the shell typically has an inner and outer lip, and an area next to the inner lip called the callus, where the shell rested on the back of the snail. Many advanced gastropods have a notch at the bottom of the shell called the siphonal notch. Finally, coiled shells are asymmetric and can be either right-handed (dextral) or left-handed (sinistral). If you hold the shell with the spire pointed upward, the aperture will be on the right in a dextral shell, and on the left in a sinistral shell. Most snails are dextral, although some are sinistral, and a few snails change their coiling direction from one to the other.

Figure 16.3 ▲

Basic anatomy of the gastropod shell. This is a dextral (right-handed) shell, which has its aperture to the right in this standard orientation. A sinistral (left-handed) shell would be the mirror image of this. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

However, there are many ways of making a coiled shell. During the early Paleozoic, there were many experiments in other types of shell coiling among the gastropods. Some, like the bellerophontids, coiled their shells in a flat spiral that stood symmetrically over the middle of their back. Bellerophon is a fairly widespread fossil in many Paleozoic localities. Another way to arrange the shell is to hold the spiral diagonally across the back and pointed forward and over the head, an arrangement called hyperstrophic. This early experiment in shell evolution is best seen in the common large Ordovician snail known as Maclurites (fig. 16.4).

Figure 16.4 ▲

Some typical archaeogastropods (top), mesogastropods (middle), and neogastropods (bottom). (Redrawn by Mary Persis Williams from several sources)

These early experiments in shell evolution vanished by the late Paleozoic, and all other prosobranch gastropods have their shell positioned diagonally over their back with the apex pointed backward; this is the orthostrophic condition. In addition to the limpets and abalones and other primitive gastropods, many coiled gastropods still retain their primitive arrangement of gills, such as the living slit shells, top shells, turban shells, dog whelks, and the sundial shell, Architectonica.

Slightly more advanced snails are known as mesogastropods, a group containing about 30,000 species (fig. 16.4). They have reduced their paired gills down to a single unbranched gill; they also tend to have a much narrower shell opening. These include the very high-spired shells such as the turritellids, plus periwinkles, moon snails, slipper shells, and many others, including a number of freshwater snail groups.

The most advanced snails are distinguished by having modified their mantle cavity into a long siphon that serves like a snorkel to allow them to breathe fresh seawater while burrowing beneath the surface. These snails are known as neogastropods, and their shells all have some kind of distinct siphonal notch, and often a long flange where the siphon is protruded out of the shell (fig. 16.4). The long siphon allows many of them to burrow into the sediment, with only their siphon exposed like a snorkel. They originated in the Early Cretaceous and soon became very abundant in the fossil record, with more than 16,000 species alive today. Most of the familiar marine snails such cone shells, conchs, cowries, whelks, muricids, olive shells, mud snails, volutes, turrids, auger shells, nutmeg shells, and hundreds more, are neogastropods.

CLASS BIVALVIA (= PELECYPODA, = LAMELLIBRANCHIA): CLAMS, OYSTERS, SCALLOPS, AND THEIR RELATIVES

Clams, scallops, and oysters are familiar to us all. They are the second most common group of living molluscs, with about 8,000 to 15,000 living species; they include a huge number of fossil species as well (at least 42,000 species). They are formally known as Bivalvia because the original molluscan cap-shaped shell of a limpet is modified into two shells, or valves, that hinge with each other. In many books, you may find them called by an obsolete name, “pelecypods,” which means “hatchet foot” in Greek. This describes the way their muscular foot is modified into a long probing appendage that can wedge itself into the sand beneath them and help them dig.

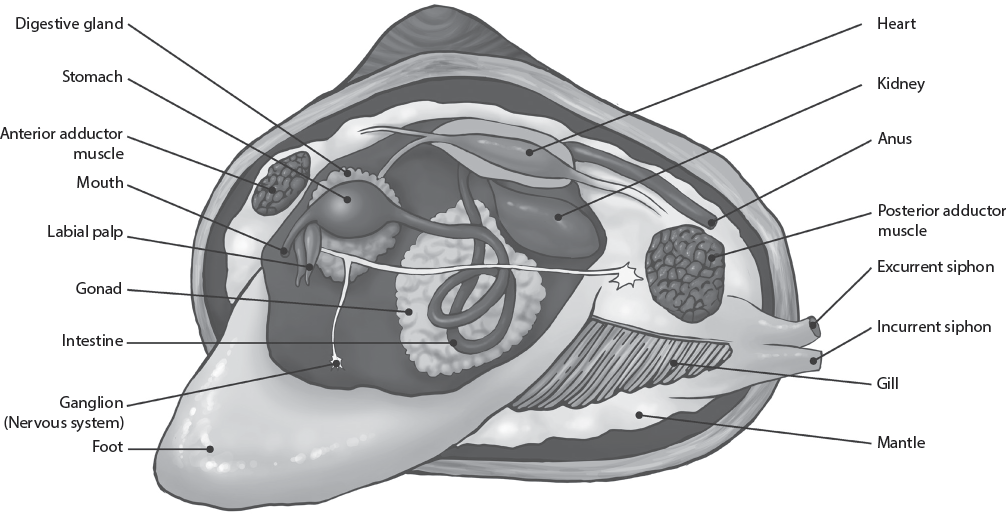

Bivalves have a very peculiar body plan (fig. 16.5). From the simple limpet-like ancestor, they have not only enlarged and hinged their shells over their bodies, but they have even lost their heads. Instead, nearly all of the internal volume of the shell is filled with their gills. An even older obsolete name is the “Lamellibranchia” (“layered gills” in Greek), which refers to how their gills were used not only for breathing but also for filter feeding. As they open their shell and let the seawater flow over the gills, they trap not only oxygen but also tiny food particles, which are then captured by mucus and flow toward the mouth at the base of the gills, and then through the digestive tract. The rest of the shell volume is taken up by reproductive organs, excretory organs, and muscles used to close the shell (adductor muscles). Finally, most bivalves have a large muscular foot that can dig down into the sand beneath them. Then the foot bulges its tip to anchor it as it pulls the shell beneath the sand. The clam rocks the shell back and forth as it knifes through the soft sediment, speeding up its sinking into the substrate. Many clams also pump water out of the shell cavity to liquefy the sediment into a soft slurry like quicksand, further accelerating the rate at which they disappear into the sediment and become less vulnerable to predators.

Figure 16.5 ▲

Basic anatomy of a clam. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams.)

Most of these soft tissue features, however, are not preserved in the shell. Instead, paleontologists use the shape of the shell, details of the hinge with its teeth and sockets, and other aspects of the shell to identify the species. Bivalve shells are symmetrical between the valves (the right valve is the mirror of the left valve), in contrast to brachiopods, whose symmetry is through the valves (see fig. 13.2B). Although bivalves have many living positions, the standard anatomical orientation used by scientists to describe them is to point the hinge upward, with the shorter end of the shell away from your body. When you do this, the right valve will be in your right hand and the left valve will be in your left hand. In this position, the foot and the mouth are on the front edge (anterior) of the shell (pointed away from you), and the long mantle tube called the siphon is at the rear (posterior) of the shell (pointed toward you).

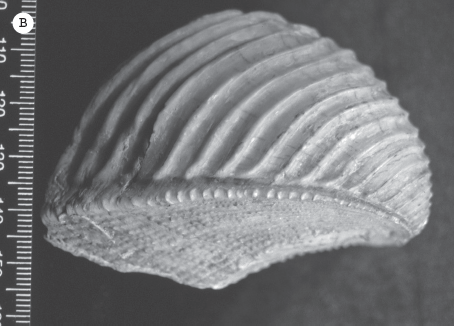

Other useful landmarks on the inside of a single shell can help us understand their function and aid in identification (fig. 16.6A–G). Bivalves have ligaments in the hinge area that spring the hinge open automatically when their adductor muscles, which close the shell, relax. This is the reason clams open automatically when they die, and it also explains why their fossilized shells are usually found separated from each other. The roughened areas where the muscles once pulled on the shell are known as adductor muscle scars. Most clams have two adductor muscles, an anterior and a posterior adductor, so there will be two scars inside each shell. Scallops are peculiar in that they swim by clapping their valves like castanets, which creates jets of water that enable them to swim erratically and escape predators. To do this, they have only one strong column of muscle, and only a single muscle scar on each shell. That muscular column is what you eat when you are served scallops in a restaurant.

Figure 16.6 ▲

(A) Lateral view of a bivalve with the left valve and mantle fold removed; (B) cross-section of bivalve with shell shown in black; (C) lateral view of interior of right valve; (D) cardinal area showing ligament groove; (E) cardinal area with resilifer; (F) lateral view of interior right valve; and (G) lateral view of exterior of left valve. (Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams)

Another feature of the inside of the shell is a boundary line dividing the area where the mantle contacted the shell (nearer the hinge) with areas where the mantle did not contact the shell (fig. 16.6F); this is called the pallial line. Typically, on the posterior part of the pallial line is an irregular notch called the pallial sinus. This is where the siphon protruded through the mantle: the deeper the sinus, the larger the siphon.

Important anatomical features are also found on the outside of the shell (fig. 16.6G). Above the hinge is the bulge or hump at the top of the external shell, called the umbo. The beak is where the shell spirals to a point. The growth lines spread concentrically from the hinge area, and the costae or ribs radiate out from it like spokes in a wheel. Some shells, such as scallops, have large corrugations or folds on the shell, known as plications. As in brachiopods, the line of the opening of the shell is called the commissure. Most clams that burrow must maintain a relatively smooth shell to reduce drag, but oysters and scallops and others that only sit on the bottom and do not burrow may have an irregular outer surface, often with spines (such as the thorny oyster), which makes it harder for a predator to break them in order to feed on them.

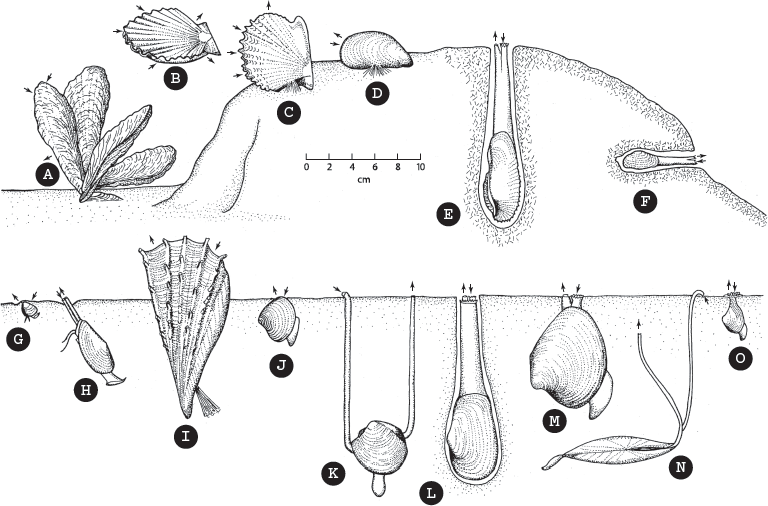

I cannot discuss all of the thousands of species and hundreds of genera of bivalves here, but it is easy to tell something about the life habits of a bivalve by looking at the shell (fig. 16.7). Scallops (subfamily Pectinaceae), for example, have a distinctive shape (familiar as the Shell Oil Company logo). Scallops live on the seafloor with their valves open and have a dozen tiny blue eyes on the edge of their mantle. When they detect a threat, they jet-propel themselves above the seafloor to escape by flapping their valves together, producing a jerky irregular movement that confuses most predators. (Search for videos of scallops swimming online—it is amazing to watch.) Oysters (subfamily Ostraceae), on the other hand, sit on the seafloor and give up any attempt to burrow or swim. Their protection is a very thick shell that is hard to open or break. In addition, many oysters live in brackish water that fluctuates between normal marine salinity of 3.5 percent and fresh water, which is an environment that most of their predators can’t stand. Mussels (subfamily Mytilaceae) live in rocky tide pools and attach to the rocks with thick, strong, fibers called byssal threads, which prevents predators from pulling them off the rocks.

Figure 16.7 ▲

Ecology of bivalves. Epifaunal suspension feeders: (A) the cemented oyster Crassostrea; (B) the swimming scallop Pecten; (C) byssally attached pearl oyster Pinctada; and (D) the mussel Mytilus. Infaunal bivalves: (E) the angel wing Pholas and (F) the geoduck Hiatella, siphonate suspension feeders that bore into rocks; (G) the nut clam Nucula, a nonsiphonate labial palp deposit feeder; (H) the nut clam Yoldia, a siphonate labial palp deposit feeder; (I) the pen shell Atrina and (J) the clam Astarte, nonsiphonate suspension feeders; (K) the lucinid Phacoides, an infaunal mucus tube feeder; (L) the soft-shelled clam Mya and (M) the venus clam Mercenaria, siphonate suspension feeders burrowed into the sediment; (N) the tellin Tellina, a siphonate deposit feeder; and (O) the septibranch dipper clam Cuspidaria, a siphonate carnivore. (After Geological Society of America Memoir 125, by S. M. Stanley. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, the Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado © 1970 Geological Society of America)

Burrowing bivalves come in lots of different shapes and sizes. The most common type are the familiar venus clams (subfamily Veneraceae), some of them are called quahogs. Most of them are shallow burrowers living in the shallow subtidal seafloor, although some species live in the surf zone and can burrow down out of sight in a matter of seconds. They have relatively short siphons, and this is reflected in the relatively shallow pallial sinus on the shell. Other clams, such as the lucinids (subfamily Lucinaceae) and the tellins (subfamily Tellinaceae), are deeper burrowers, with very long siphons. Some bivalves are very deep burrowers. Their thick siphons are so large that they cannot close around them, leaving a permanent gape in the posterior of the shell. These include the soft-shelled clams (subfamily Myaceae), such as the mud-burrowing geoduck (pronounced “gooey-duck”) Panopea. They may have a thick siphon as long and thick as your arm, with a small shell at the end. Other deep burrowers with long siphons are the razor clams (family Solenidae). A number of clams have adapted for rock boring (family Pholadidae), and their shell is reduced to a pair of cutting blades at the end of a long fleshy body that is protected by their burrow instead of by a shell.

Some extreme variations on the basic clam body shape lose their symmetry when they become oyster-like. For example, the giant clams (family Tridacnidae) have a huge thick shell that is corrugated but seldom closes completely (fig. 16.8A). This gap is covered with a thick area of mantle filled with symbiotic algae in their tissues, which help them grow to such giant sizes (just as algae allow corals to grow their large reefs of limestone).

Figure 16.8 ▲

A variety of odd-shaped bivalves, especially oyster-like forms that abandon all attempts at bilateral symmetry because they do not burrow. (A) The living giant clam, Tridacna, which spends its time in coral reefs using algae in its mantle tissues to help it grow. (B) The triangular Triassic clam, Trigonia. (C) The coiled dish-shaped Gryphaea, also known as “Devil’s toenails.” (D–E) The spirally coiling Cretaceous oyster Exogyra. (F) The giant flat “dinner plate” clam, Inoceramus. (G) Reconstruction of inoceramids as they may have looked on the Cretaceous seafloor. (H–I) Two examples of the huge cone-shaped rudistid oysters, which built the major reefs during the Cretaceous. ([A, C–I] Photographs by the author; [B] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A number of interesting extinct oysters are also common in fossil collections. A common Triassic fossil is the triangular clam known as Trigonia, whose name means “triangular” in Greek (fig. 16.8B). Trigoniids survived most of the Mesozoic but were thought to be extinct until a living descendant, Neotrigonia, was discovered in 1802 in the South Pacific, a true living fossil. During the Jurassic, one group of oysters grew into a spiral with one valve and a small lid on the other (fig. 16.8C). Known to paleontologists as Gryphaea, their common name is “Devil’s toenails.” In the Cretaceous, an even weirder group of oysters evolved with a corkscrew spiral shape that resembles a snail shell in one valve and a lid on the other (fig.16.8D–E). It is known as Exogyra, which translates from the Greek as “spiraling outward.”

Another group of Cretaceous clams were the huge flat inoceramids (fig. 16.8F–G). Both valves were shaped like shallow plates, and the biggest ones were 5 feet (1.5 meters) across. They apparently lay flat on the seafloor of the shallow waters of the Cretaceous seaways. Many are found with complete fish and other fossils inside them, suggesting that they harbored a number of symbiotic organisms that sought shelter inside their huge shells.

But the most bizarre of all bivalves were the Cretaceous reef-building oysters known as rudistids (fig. 16.8H–I). One valve was shaped like a large cone, embedded point down into the seafloor. The other valve was shaped like a lid that covered the opening, and it would open whenever the clams needed to let in currents for food and oxygen. Rudistids formed huge reefs of densely packed shells in the tropical waters of the Cretaceous and even drove corals from the reef region.

CLASS CEPHALOPODA: SQUID, OCTOPUS, CUTTLEFISH, NAUTILOIDS, AND AMMONOIDS

Molluscs have evolved a wide variety of body plans, from the slow-moving snails to the headless clams that burrow beneath the surface and filter feed, to the chitons and tusk shells, and to the planktonic pteropods. But the champions of molluscs in terms of speed, intelligence, and complex behavior are the cephalopods. Cephalopoda means “head foot” in Greek, which refers to how the primitive foot of molluscs has been modified into a ring of tentacles around the head and mouth.

Speed and intelligence are the hallmarks of the group. Squids jet-propel themselves backward through the water faster than most animals can swim. The octopus is legendary for its intelligence, amazing quickness, and camouflage ability that enables its skin pattern to change. In fact, many cephalopods can rapidly change their skin patterns and even flash patterns in their skins faster than neon lights, which they use for communication. Most cephalopods also have an amazingly well-developed eyeball that is much like the vertebrate eye, but it evolved independently and converged on the vertebrate eyeball. It has a cornea, lens, and retina, but it is much better designed than our eyes. Octopus eyes don’t have a blind spot in the retina for the exit of the optic nerve, nor is the sensory layer of the retina covered by blood vessels and other tissues that distort the light, as in vertebrate eyeballs. Vertebrates also have their photoreceptors pointed backwards in the retina, away from the light source.

Most cephalopods are large active predators or scavengers, floating above the seafloor in search of prey that they grab with their tentacles armed with suckers. Most of them expel water from the mantle cavity to give them a sort of jet propulsion, especially when they are trying to escape predators. Some, such as squid and octopus, even leave a cloud of ink behind them as a smokescreen to cover their escape. In addition to their water jets, squid and cuttlefish can swim slowly forward using the fins along the side of their bodies, and octopus mostly move with their long arms.

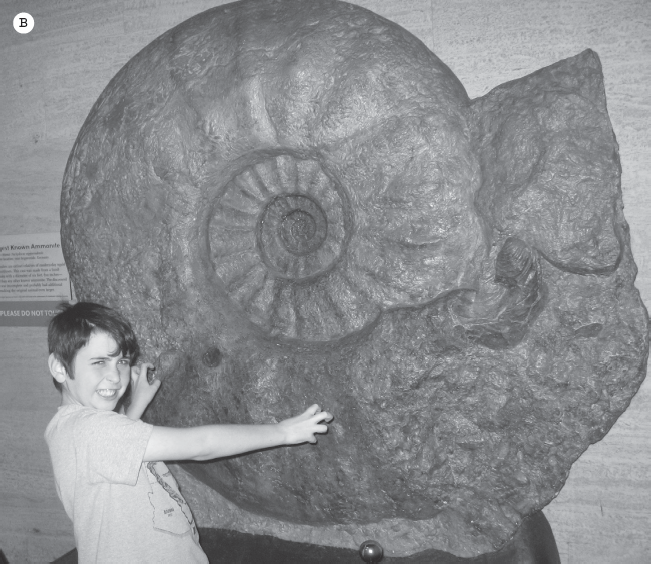

Cephalopods range in size from tiny squid only a few inches long to the giant squid that was about 50 feet (18 meters) long (fig. 16.9A). The maximum leg span of an octopus is more than 33 feet (10 meters). Some ammonite shells were more than 5.2 feet (1.7 meters) across, suggesting that the soft body was as large as the largest squid today (fig. 16.9B). Cephalopods live exclusively in marine waters; they were unable to colonize the freshwaters or move on land as snails and clams did. However, they sometimes live in huge numbers in the ocean, with some squid schools containing more than a thousand individuals. Many cephalopods, like the vampire squid, specialize in very deep, dark, cold parts of the ocean from 1.8 to 3 miles (3,000 to 5,000 meters) below the surface.

Figure 16.9 ▲

Giant cephalopods. (A) The giant squid, which lives in the deepest part of the ocean, and rarely washes ashore. They reach about 50 feet (18 meters) in length. (B) The gigantic ammonite Parapuzosia, which would have had an enormous head and long tentacles protruding from its opening. ([A] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] photograph by the author)

There are about 1,000 living species of squids, octopus, and cuttlefish; they have no external shell, although squids and cuttlefish have a rod of a hard substance (calcite or an organic material) holding their bodies rigid. Only one group of living cephalopods has an external shell, the famous chambered nautilus of the South Pacific (fig. 16.10A–C). They are practically the only living analogue for the 17,000 species of extinct shelled cephalopods in the fossil record. There are many different types of extinct nautiloids as well. One extinct group that branched off from the nautiloids is the ammonoids, one of the most successful of all groups in the fossil record. They got their name because their coiled shells resembled the horns of the Egyptian ram-god Ammon. In the Middle Ages, some were thought to be petrified snakes (serpent stones), and the last part of the shell was sometimes carved with a snake’s head to enhance its serpentine appearance and market value. By 1700, the English naturalist Robert Hooke, the father of microscopy, saw the newly discovered chambered nautilus and correctly inferred that ammonites were related to nautilus, not snakes.

Figure 16.10 ▲

The chambered nautilus, the only living shelled cephalopod. (A) A living Nautilus, showing the tentacles, eye, and hood over the opening. (B) Diagram of the external features of the living Nautilus. (C) Cross-section of the anatomical features of the interior of the Nautilus. ([A] Courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons; [B–C] redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams.)

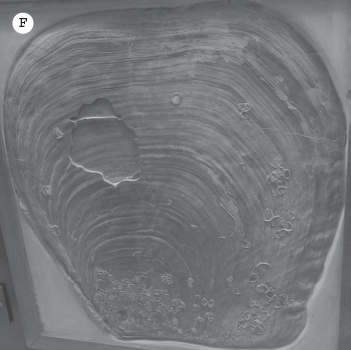

The nautilus shell is coiled in a flat spiral, like the snails that coil in a plane. However, unlike the shell in snails, the cephalopod shell interior is divided into chambers by a series of walls called septa (fig. 16.10C). The mollusc itself lives only in the last chamber. As its shell grows, its body moves forward until it can seal off another portion of its shell with a new septum. Once the septum seals the chamber, the nautilus uses a long fleshy stalk from its body, called the siphuncle, that connects all the chambers to slowly pull the water out of the new chamber using osmosis, leaving it filled with gases that help the shell float. The blood in the umbilicus is much saltier than the water in the sealed chamber, so the water slowly diffuses into the umbilicus until only gas remains. Contrary to popular myth, the nautilus cannot pump water in and out of the old chambers rapidly to change its buoyancy and rise or sink in the depths of the ocean.

The edge of the septum meets the outer shell at a line of intersection called the suture. These are usually only visible in fossils if the outer layer of shell has been eroded or polished away, exposing the outer edge of the septum (fig. 16.11). The suture pattern is the most diagnostic feature of most cephalopod shells, and it helps define the different species, genera, and even higher groups. In the primitive nautiloids, it is simple broad curve. As we shall see when we look at the extinct ammonoids, the suture became more complex and intricate, and this complexity makes it possible to recognize and identify the major groups of ammonoids.

Figure 16.11 ▲

The intersection of the edge of the septum with the outer shell forms a line called the suture, which can be seen in fossils if the outermost shell layers are scraped or eroded away. The details of the patterns of saddles and lobes in the suture enable paleontologists to identify almost any ammonoid. (Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams)

The rest of the body of the nautilus resembles the unshelled squid and octopus in shape. The large head is covered with a hood, and big eyes dominate body. Nautilus has a parrot-like beak in the mouth, surrounded by a ring of tentacles, which it uses to catch prey (mostly crustaceans and carrion). Beneath the head is the mantle cavity, where the gills lie. At the entrance to the mantle cavity is a nozzle called the hyponome, which funnels and focuses the jet of water to propel them. As the body squeezes down on the mantle cavity, it forces the water out the hyponome and creates a jet of water. Like octopus, however, nautilus uses jet propulsion only for rapid motion, especially when escaping. Most of the time, they use their tentacles to creep along the seafloor in any direction, especially when they are hunting.

SUBCLASS NAUTILOIDEA

The Nautiloidea includes the living chambered nautilus and a variety of Paleozoic relatives with long straight shells. They first appeared in the Cambrian, and by the Ordovician they were abundant in nearly every marine assemblage. Some were huge (fig. 16.12A–B) and became the largest animals in the ocean. The biggest was Cameroceras, with some shells reaching 33 feet (11 meters) in length; the squid-like creature that once lived in that shell must have been as large as the living giant squid. Slightly smaller is the common fossil Endoceras, which was 11 feet (3.5 meters) in length. Most, however, were much smaller, typically only a few inches to a foot long.

Figure 16.12 ▲

Straight-shelled orthocone nautiloids were the largest predators of the early Paleozoic, with shells reaching 33 feet (11 meters) in length, with even more length in their tentacles. (A) The size of Cameroceras compared to a 6-foot-tall person. The tentacles and soft parts are reconstructed, so they could have been much longer. (B; color figure 6) Diorama of the orthocone nautiloid as it would have appeared in the Ordovician. ([A] Illustration by Mary Persis Williams; [B] photograph by the author)

Straight-shelled (orthocone) nautiloids were superpredators of the Ordovician and Silurian, and they ate almost anything they could catch. The inside of their large heavy shells were counterweighted with calcite deposits that served as ballast, so they floated horizontally above the sea bottom. Otherwise, the gases in the chambers would have made the shell float point upward. They could not move fast to chase prey, so they must have ambushed prey that crept within reach of their tentacles. As the first large marine superpredators in the oceans, they may have influenced how trilobites became more specialized to avoid predation in the Ordovician (see chapter 15).

Different groups of nautiloids are distinguished by where they deposited the calcite ballast in their shell. The Endoceratoidea filled their shell with cone-shaped deposits of calcite called endocones, which were nested one inside the other like conical cups in the dispenser next to a watercooler. They are most common in Ordovician beds around the world, and they died out in the Silurian. Another Ordovician group was the Actinoceratoidea, which are recognized by calcite deposits filling the tube around the siphuncle (endosiphuncular deposits). Other groups had deposits of calcite within the chambers (endocameral deposits). Usually, the specimen must be sliced open, or eroded or broken naturally, to reveal these internal features. Straight-shelled nautiloids reached their climax in the Devonian, and specimens from the Silurian and Devonian of the Tindouf Basin of Morocco are so abundant that they are commercially mined in large quantities and sold all over the world.

Nautiloids then declined during the rest of the Paleozoic, and the large straight-shelled orthocone nautiloids vanished altogether. However, the primitive coiled forms persisted through the Mesozoic in small numbers, and they survived the Cretaceous extinction event much better than their relatives, the ammonites, which died out completely. The shell of a coiled nautiloid such as Aturia is occasionally found in Cenozoic beds all around the world, so they continued to survive despite losing the world’s oceans to bigger predators such as fish.

SUBCLASS AMMONOIDEA

During the Devonian, one group of straight-shelled nautiloids (the bactritoids) is thought to have coiled up into a spiral in a flat plane and given rise to the next big radiation of cephalopods, the Ammonoidea. Ammonoids are distinct from nautiloids in that the siphuncle penetrates the septal wall on the outer rim of the shell (the venter) rather than in the middle of the septum, as in nautiloids (see fig. 16.11). From the Devonian through the Permian, there was a great evolutionary radiation of the most primitive ammonoids. They are known as goniatites, and they can be recognized by their distinctive zigzag suture pattern on specimens where the outer shell is removed (fig. 16.13A–B). They are excellent index fossils for the later Paleozoic, and in some localities (such as the Devonian beds of the Tindouf Basin of Morocco) the goniatite Geisenoceras occur in huge numbers and are commercially mined on a large scale and sold by shops and dealers all over the world.

Figure 16.13 ▲

The pattern of the sutures on the cephalopod shell is crucial to identifying them and determining the age of the beds from which they come. (A) Patterns of sutures on the shells through time, with increasing complexity from the simple curves of nautiloids to the convoluted sutures of ammonites. (B) Typical zigzag goniatite suture on a large Geisonoceras from the Devonian of Morocco. (C) The U-shaped ceratitic suture of the Triassic ammonoids called ceratites; this is the genus Ceratites. (D) The complex suture of ammonitic ammonoids of the Jurassic and Cretaceous seen in this Placenticeras. (E) The serpenticone ammonite Dactlyioceras. ([A] Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams; [B, D, E] photographs by the author; [C] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

During the great Permian extinction event, all but two lineages of goniatitic ammonoids were wiped out. These survivors were the ancestors of a new diversification of ammonoids during the Triassic. These ammonoids had a distinctive ceratitic suture, which typically had a series of U-shaped curves in it (fig. 16.13A, 16.13C). At their peak, there were about 80 families and more than 500 genera of ceratitic ammonoids. The ceratitic ammonoids went through another extinction crisis at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary.

The survivors of this extinction underwent a final huge evolutionary radiation in the Jurassic and the Cretaceous. By the Jurassic, there were 90 different families, and even in the Cretaceous there were still 85 families, although they declined to only 11 families near the end of the Cretaceous. These ammonoids had a complex, intricate florid suture pattern (fig. 16.13A, 16.13D), known as an ammonitic suture. The details of their complex sutures allow the paleontologist to identify any good specimen to species.

During this great Mesozoic diversification, ammonites evolved into many shapes. Some were streamlined with sharp edges such as the oxyconic shells of Placenticeras and related genera (fig. 16.13D), and they must have been relatively fast swimmers (although none were as fast as squids or fish). Others had short, fat cadicone shells, and they must have moved slowly along the bottom to catch their prey. Some had coils that resembled a coiled snake (serpenticone), as seen in the genera Dactylioceras and Stephanoceras (fig. 16.13E).

The most unusual ammonites, however, began to uncoil the simple flat spiral into a number of weird and bizarre forms. They are known as heteromorph (“different shape” in Greek) ammonites (fig. 16.14A). Some were just slightly uncoiled, like Scaphites (fig. 16.14B), or partially uncoiled like Audoliceras (fig. 16.14C). Others uncoiled into huge hairpin shapes, like Hamites and Diplomoceras (fig. 16.14D), weird question-mark shapes like Macroscaphites and Didymoceras (fig. 16.14E), uncoiled flat spirals (Spiroceras), and even stranger shapes. The oddest of all were those that coiled up a spiral axis like a snail such as Turrilites (fig. 16.14G), or coiled into a tight knot like Nipponites (fig. 16.14H). The heads of these ammonites were often in almost inaccessible positions, and they could not use jet propulsion because they would start to spin crazily. So they must have floated passively in the ocean and trapped nearby food with their long tentacles or crept slowly along the seafloor using their tentacles. Perhaps the most common and rapidly evolving heteromorphs were the baculitids (fig. 16.14F), which had secondarily straightened out their originally coiled shell into a nearly straight cone (with just a tiny coil sometimes remaining at the tip). Unlike the straight-shelled nautiloids with the counterweight ballast in their shells to hold them horizontal, baculitids had no ballast deposits inside them, so they floated with their shell point upward and their heads dangling below (fig. 16.14I). Clearly, they could not swim fast in this position, so they must have either crept along the seafloor using their tentacles or (as recent research suggests) floated in the open waters like plankton, trapping nearby prey (possibly even smaller plankton) with their tentacles.

Figure 16.14 ▲

Heteromorph ammonites started with simple flat spirals but became uncoiled in many weird and different ways: (A) some of the common heteromorph patterns; (B) slightly uncoiled Scaphites; (C) partially uncoiled Audoliceras; (D) hairpin-shaped Diplomoceras; (E) question-mark shaped Didymoceras; (F) straight-shelled Baculites, with some other heteromorphs; (G) coiled up an axis like a high-spired snail, such as Turrilites; and (H) Nipponites, with its shell twisted into a knot. (I; color figure 7) Diorama of the Cretaceous seafloor showing a large normally coiled ammonite, a corkscrew-spiraled heteromorph, the long straight Baculites, and the squid-like belemnites. ([A] Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams; [B–D, G–H] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [E–F, I] photographs by the author)

After surviving the Permian extinction, the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, and several smaller crises, all of this great diversity of ammonites that had long dominated the Mesozoic seas (and are the best fossils for telling time) vanished with the great Cretaceous extinction. Only the coiled nautiloids and the cephalopods without external shells survived.

SUBCLASS COLEOIDEA

The coleoids include most of the cephalopods without external shells: squids, octopus, cuttlefish, argonauts, and their relatives. Without a hard external shell, they do not fossilize very well, and only a few complete specimens with soft tissues are known. However, one type of coleoid does fossilize well. Known as belemnites, they left a conical internal shell called a guard or rostrum, which reinforced their squid-like body and counterbalanced the weight of the head and tentacles. (In contrast, living squid have a thin, lightweight, flexible rod that serves to stiffen the back part of the body.)

Belemnite fossils look like large stone bullets (fig. 16.15), and they are particularly common in the Jurassic and Cretaceous, where some beds have concentrations of hundreds of belemnite fossils. A few belemnites have been found in extraordinary localities that preserve the soft tissue, so we know that these fossils came from a squid-like creature that is now extinct.

Figure 16.15 ▲

Belemnites are the internal shells of an extinct group of squids. They produced abundant large calcite shells in the Jurassic and Cretaceous that looked like large bullets. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)