BARACK OBAMA ENTERED THE PRESIDENCY with an impressive record of political success, at the center of which were his rhetorical skills. In college, he concluded that words had the power to transform: “with the right words everything could change—South Africa, the lives of ghetto kids just a few miles away, my own tenuous place in the world.”1 It is no surprise, then, that Obama followed the pattern of presidents seeking public support for themselves and their policies that they can leverage to obtain backing for their proposals in Congress.

Moreover, it was commonplace at the beginning of his term for commentators to suggest that the president could exploit the capacity for social networking to reach people directly in a way that television and radio could not and harness this potential to overcome obstacles to legislative success. In theory, the new president could mobilize his legions of supporters and use their support to transform public policy.

In this chapter, I examine the Obama White House’s efforts to lead the public. I focus on its press relations and other aspects of going public and pay particular attention to the classic challenges that every administration faces in focusing the public’s attention, reaching the public with its messages, framing issues to its advantage, and mobilizing supporters.

The White House was aggressive in its public advocacy. The president-elect requested a communications strategy right after the election,2 and the White House communications staff swelled from forty-seven members under Bill Clinton and fifty-two under George W. Bush to sixty-nine under Barack Obama.3 Even during the transition, the president began a full-scale marketing blitz to pass his massive stimulus package, including delivering a major speech at George Mason University. The president delivered 989 speeches, comments, and remarks in his first two years in office.4 He also conducted twenty-three town hall meetings (including one in Strasbourg, France, and another in Shanghai, China) in his first year.5 He was the first sitting president to appear on the Jay Leno and David Letterman shows, and he talked to ESPN and People magazine.

When he was sworn in, Obama told friends he was eager to tackle the rigors of the Oval Office without the drudgery of shuttling to a different part of the country every other day during his two-year campaign for the presidency. In addition, the president was reluctant to be too far away from Washington, aides said, because he was juggling economic proposals, meeting with military commanders, trying to fill his cabinet, and meeting with a series of agencies for an early look at his administration. After three weeks in office, however, the president found the public’s support for his economic recovery package was eroding as Republicans intensified their criticism of the plan. So his advisors told him he had no choice but to use Air Force One and take his case to the public.6

The president pledged to leave Washington every week. On February 9, 2009, he visited Indiana. The next day he was in Florida, and then on to Virginia and Illinois in the next two days. He has never let up his travel schedule.7

Often the travel provided helpful backdrops for making his case. When Obama announced a plan to slow mortgage foreclosures by reducing troubled homeowners’ monthly payments, he traveled to Mesa, Arizona, a community hit hard by the subprime crisis, where median home prices had fallen 35 percent over the past year. In signing the economic stimulus package, he dispensed with customary settings like the Oval Office or Rose Garden and held the ceremony in Denver so he could be out West in an area that had been hit hard economically, away from the politics of Washington.

The same principles applied to foreign policy. When it came time for the president to offer a time line for withdrawing troops from Iraq, he journeyed to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, to deliver the news before thousands of U.S. Marines. When he ordered 30,000 additional troops to Afghanistan, he did so in a prime-time speech to the cadets at West Point.

The primary intermediary between the president and the public is the press, and the White House has been attentive to servicing the press. Obama appointed Robert Gibbs, a close associate who had his ear, as press secretary. Being in the inner circle of the White House gave Gibbs high credibility as a White House spokesman. (There were some complaints from reporters, however, that Gibbs spent so much time with the president that he did not have enough time to talk to reporters.)8

The president hosted lunches and dinners for TV anchors and columnists; held off-the-record sessions with liberal columnists and historians; and ate dinner with conservative writers at columnist George Will’s house. In addition, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel was unusually active in working the media, cajoling, lobbing, berating, and trading information with reporters. The White House pays particular attention to the New York Times, which Gibbs believes has the ability to drive the news.9

Equally important, Obama made a concerted effort to tap into alternatives to the mainstream national media, including Spanish-language magazines, newspapers, and television and radio stations and those oriented to African Americans.10 As we will see, the White House is also oriented toward blogs, Internet videos, Facebook, and Twitter. The press pool that takes turns covering the president up close now includes Web-only publications like Talking Points Memo, the Huffington Post, and the Daily Caller. The president also submits to interviews with regional newspapers.

At the same time, the president has tried to deal with the press in a different way from that of his predecessors. Obama held forty-six news conferences in his first two years, of which eleven were formal, solo White House question-and-answer sessions. Four were in prime time. He went for seven months before holding a full-scale press conference on February 9, 2010.11 When he did hold his formal press conferences, the White House decided the day before each one who the president would call on, and sometimes notified the reporters in advance. This procedure miffed some reporters, who felt they were being reduced to the role of mere extras. Past presidents have generally worked their way around the room, starting with the wire services, networks, and major newspapers.12

In his first daytime news conference, held on June 23, 2009, the president declared, “I know Nico Pitney is here from the Huffington Post.” Obama knew this because White House aides had called Pitney the day before to invite him, and they had escorted him into the room. The aides told him the president was likely to call on him, with the understanding that he would ask a question about Iran. Pitney said that although the White House was not aware of the question’s wording, it asked him to come up with a question about Iran proposed by an Iranian. Later, Obama passed over representatives from major U.S. news outlets to call on Macarena Vidal of the Spanish-language EFE news agency. The White House called Vidal in advance to see whether she was coming and arranged a seat for her. She asked about Chile and Colombia.13

In addition, the president has chosen not to answer reporters’ questions at most day-to-day events, such as those with foreign leaders, as other presidents have done. During his first two years in office, Obama took questions in such venues 75 times, compared with the 243 times George W. Bush and 390 times for Bill Clinton did in the comparable periods. Instead of open-ended sessions with multiple reporters, he prefers one-on-one interviews, particularly on television.14

The president sits for far more interviews than his two most recent predecessors did, reflecting the fact that he feels the interview format is a more effective means for getting his message through. In his first two years, he gave 269 interviews, compared with 83 by Bush and 136 by Clinton in comparable periods. One hundred and forty of the sessions were TV interviews, and forty-four were for radio. Another sixty-nine were for print organizations, fourteen were for mixed media, and two were for solely online organizations.15 Among the attractions of television interviews for Obama are that they tend to be played in full and serve as a useful vehicle for reaching a large number of people.

The White House has displayed some skill in using the press to serve its purposes. After the protracted decision-making process that climaxed with the president’s December 1, 2009, announcement of sending an additional 30,000 U.S. troops to Afghanistan, the White House briefed the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times on the policy discussions. In early December, each newspaper carried behind-the-scenes stories on the process, all reflecting Obama as a deliberative and tough-minded manager.16

When the president faced strong Democratic opposition to the extension of the Bush-era tax cuts during the 2010 lame-duck session of Congress, the White House launched a public relations blitz. Presidential press secretary Robert Gibbs instructed his staff to send out an e-mail every time a prominent politician backed the deal—even those of governors, mayors, and state legislators who had no power to directly influence the outcome. Obama even escorted former President Bill Clinton into the White House briefing room on December 10, where the former president praised the deal as the best compromise possible during a memorable thirty-minute exchange with reporters.17

The White House has also shown some deftness at catering to a nonstop, Internet- and cable-television-driven news cycle. For example, the White House went to great lengths to project an image of competence in U.S. relief efforts in Haiti, in implicit contrast to the way the Bush administration mishandled Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. The administration and the military set up a busy communications operation with twenty-five people at the American Embassy and in a cinder-block warehouse at the airport in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital. The White House released a torrent of news releases, briefings, fact sheets, and statements, including “ticktock” (a newspaper term of art for a minute-by-minute reconstruction of how momentous events unfolded), a link to a Flickr photo of a meeting on Haiti in the Situation Room, presided over by the president, a video of American search teams rescuing a Haitian woman from a collapsed building, and a list of foreign leaders he had telephoned.18

The administration has been less successful when wielding the stick. It soon grew weary of Fox News’s unrelenting and often vitriolic criticism and limited the appearances of some top officials on some Fox News shows. More visibly, it excluded Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace—which it had previously treated as distinct from the network—from a round of presidential interviews with Sunday morning news programs in mid-September 2009. In late October, the White House tried to exclude Fox from a round of interviews with the executive-pay czar Kenneth R. Feinberg. When Fox’s television news competitors refused to go along, the White House relented.19 Fox’s access soon returned to normal.20

The first step in the president’s efforts to lead the public is focusing its attention. The president is unlikely to influence people who are not attentive to the issues on which he wishes to lead. If the president’s messages are to meet his coalition-building needs, the public must sort through the profusion of communications in its environment, overcome its limited interest in government and politics, and concentrate on the president’s priority concerns. Even within the domain of politics, political communications bombard Americans every day (many of which originate in the White House). The sheer volume of these communications far exceeds the attentive capacity of any individual.

In recent decades, presidents have had the goal of a disciplined communications strategy, at the core of which is a consistent message of the day. Shortened news cycles have made such strategies obsolete, however. Obama wanted to focus on winning the week rather than the day,21 but achieving even this goal was to prove a major challenge.

Obama’s team earned a reputation for skill and discipline in dominating the communications wars with his opponents on the road to winning the White House. Governing is considerably more difficult, however. Campaigns are tightly focused on one goal: winning elections. Governing requires attention to multiple goals, many of which are thrust upon the White House. Thus, the president must speak on many issues and to many audiences simultaneously. As White House senior advisor David Axelrod put it, the challenge of managing and controlling messages in a campaign and in the White House is “the difference between tick-tack-toe and three-dimensional tick-tack-toe. It’s vastly more complicated.”22

Presidents must cope with an elaborate agenda established by their predecessors.23 The president’s choices of priorities usually fall within parameters set by prior commitments of the government that obligate it to spend money, defend allies, maintain services, or protect rights.24 As Kennedy aide Theodore Sorensen observed, “Presidents rarely, if ever make decisions . . . in the sense of writing their conclusions largely on a clean slate.”25

Moreover, every administration must respond to unanticipated or simply overlooked problems, including international crises. These issues affect simultaneously the attention of the public and the priorities of Congress and thus the White House’s success in focusing attention on its priority issues.26 Administration officials also cannot ignore events, as campaigns often do. “You can pick and choose what you want to discuss and what you don’t want to discuss,” said Axelrod. “When you’re president of the United States, you have a responsibility to deal with the problems as they come.” Communications director Daniel Pfeiffer added: “In the White House, you have the myriad of challenges on any given day and are generally being forced to communicate a number of complex subjects at the same time.”27 Thus, according to Axelrod, the sheer volume of crises overwhelmed the message.28

In September 2009, the president was engaged in a major public relations effort to turn around public opinion on health care reform. The effort to sustain a focus on health care came to a screeching halt after September 21, however. In the period of September 22–25, 2009, Obama addressed the UN General Assembly, chaired a meeting of the UN Security Council, and spoke at a UN Climate Change Summit and former President Clinton’s Global Initiative conference. He also attended multiple meetings of the G-20 countries, a Friends of Pakistan meeting, and a meeting of countries contributing peace-keeping troops, and held bilateral meetings with British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, Japanese Prime Minister Hatoyama, President Medvedev of Russia, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, Palestinian Authority President Abbas, and Chinese President Hu. In addition, the president hosted a reception for heads of state and government and a lunch for Sub-Saharan African heads of state and held a news conference focused on foreign affairs. It is not surprising, then, that Pew found that international issues and events dominated news coverage in the week of September 21–27, with health care coverage constituting only 9 percent of the news hole.29

At the beginning of May 2010, the president’s top advisors thought they had a public relations plan for the week: a focus on jobs and the White House’s efforts to boost the economic recovery.30 That agenda lost focus, however, when three unanticipated events with which Obama had to deal dominated the news. First, the BP oil spill and possible environmental crisis in the Gulf of Mexico required a presidential visit to the area and regular commentary from the White House. Then, a terrorist’s bomb found in New York’s Times Square provided yet another distraction. There was no way the president could not comment on such an event, and there was no way it would not dominate the news. Finally, Arizona passed a controversial immigration law, focusing attention on yet another issue.

In addition to prior commitments and unanticipated events, there are competitors for the public’s attention. Successful campaigns maintain control of their message most of the time. Once in office, the president communicates with the public in a congested communications environment clogged with competing messages from a wide variety of sources, through a wide range of media, and on a staggering array of subjects.31 A year into the president’s term, communications direction Dan Pfeiffer declared, “It was clear that too often we didn’t have the ball—Congress had the ball in terms of driving the message.”32

To be effective in leading the public, the president must focus the public’s attention on his policies for a sustained period of time. This requires more than a single speech, no matter how eloquent or dramatic it may be. The Reagan White House was successful in maintaining a focus on its top-priority economic policies in 1981. It molded its communication strategy around its legislative priorities and focused the administration’s agenda and statements on economic policy to ensure that discussing a wide range of topics did not diffuse the president’s message.33 Sustaining such a focus is difficult to do, however. After 1981, President Reagan had to deal with a wide range of noneconomic policies. Other administrations have encountered similar problems.

Focusing attention is more difficult as an administration proceeds. The White House can put off dealing with the full spectrum of national issues for several months at the beginning of a new president’s term, but it cannot do so for four years; eventually it must make decisions. By the second year, the agenda is full and more policies are in the pipeline as the administration attempts to satisfy its constituencies and responds to problems it has overlooked or that arose after the president’s inauguration.

Focusing attention on priorities is considerably easier for a president with a short legislative agenda, such as Ronald Reagan, than it is for one with a more ambitious agenda, such as Barack Obama’s. Obama began proposing his large agenda immediately after taking office. Moreover, Democrats had a laundry list of initiatives that George W. Bush had blocked, ranging from gender pay equity and children’s health insurance to tougher tobacco regulations and a new public service initiative. In addition, there were recession-related efforts to provide mortgage relief and curb predatory banking practices to complement the president’s economic stimulus measure.

The president and his fellow partisans believed in activist government and were predisposed toward doing “good” and against husbanding leadership resources. But no good deed goes unpunished. The more the White House tried to do, the more difficult it was to focus the country’s attention on priority issues. Once the administration had put in place policies to deal with the worst of the crises Obama inherited, it moved on to health care, climate change, Afghanistan, and other major initiatives. The result was a perception in the public about a loss of focus on unemployment, prompting a shift back to the economy at the beginning of the president’s second year in office.

Former White House communications director Anita Dunn said the administration had always seen health care reform as a central part of its economic message. “Our lack of success at doing that . . . is one of the reasons that people feel there wasn’t the focus” on the economy, she said. Another White House official asserted that on the economy, “We’ve got a better story to tell than we’ve told.”34

There were many challenges to the Obama White House focusing on its priorities. One challenge was not being distracted by peripheral issues. When the Republicans began characterizing the president’s economic stimulus bill as wasteful “pork” spending, the president launched a media blitz to counteract this image. Wary of selecting one favored network and alienating the others, the White House arranged for interviews with NBC’s Brian Williams, CBS’s Katie Couric, ABC’s Charles Gibson, CNN’s Anderson Cooper, Fox’s Chris Wallace, and on ABC’s Nightline on February 3.

There was a problem with this strategy, however, because the interviews took place only hours after former senator Tom Daschle withdrew as Obama’s nominee to become secretary of Health and Human Resources over his belated payment of back taxes. This embarrassing situation became the dominant story in the interviews, with the president telling one anchor after another that he had “screwed up.” Although by admitting what he called “self-inflicted wounds,” the president preempted days of stories about whether the administration was playing down the magnitude of the mess, the issue distracted from the White House’s principal purpose in granting the interviews.

In May, the president’s commencement speech at the University of Notre Dame, in Indiana, and his choice of a candidate to replace Justice David H. Souter raised the issue of abortion to higher levels of visibility. This prominence counteracted Obama’s effort to “tamp down some of the anger” over abortion, as he said in a news conference in April, and to distract from his other domestic priorities, like health care.35

On July 16, Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. returned to his Cambridge, Massachusetts home to find the door stuck. A neighbor reported that someone might be trying to break into the house, and the police responded. Although the arresting police officer, Sgt. James Crowley, became aware that Professor Gates was in his own home, the police said Gates was belligerent and arrested him for disorderly conduct. (The charge was later dropped.)

A reporter asked Obama for his reaction to the incident as the last question in his July 22 prime-time press conference, a session that was otherwise largely devoted to health care reform. The president replied that the police had “acted stupidly” in hauling Professor Gates from his home in handcuffs. Obama’s choice of words generated angry responses from the Cambridge police. Worse, media attention spiked in response to the president’s comments. Thirty percent of the public reported that they followed the story very closely, and 17 percent said it was the story they followed most closely. The media devoted 12 percent of the news hole to the incident, tying it for the second-most covered story of the week. More significantly, the story filled only 4 percent of the news hole on Wednesday, before the president’s press conference that evening, but the figure rose to 19 percent on Thursday and 31 percent on Friday.36 The president had become a distraction from his high-priority policy initiative and his attempt to focus attention on it with a televised prime-time press conference.

In an attempt to move beyond the controversy that had dominated the previous two days of press coverage, the president made a surprise visit to the White House Briefing Room on July 24. He admitted that he “could have calibrated” his words more carefully in his press conference response, and told the press of his phone call that afternoon to Officer Crowley, whom he complimented as an outstanding police officer. The controversy, Obama acknowledged, overshadowed his attempt to explain the effort to overhaul the nation’s health care system. As he put it, “over the last two days as we’ve discussed this issue . . . nobody has been paying much attention to health care.”37

The Gates issue still had legs, however. The president invited the professor and Crowley for a beer at the White House on July 30, producing yet another round of stories. The controversy composed 8 percent of the news hole the week of July 27.38

Yet another distraction for the president were protests organized by a loose-knit coalition of conservative voters and advocacy groups at meetings held by congressional Democrats and administration officials to discuss health care. The conservative groups, including FreedomWorks, Americans for Prosperity, Right Principles, and Americans for Limited Government, harnessed social networking Web sites to organize and encourage their supporters to flood events and heckle and generally disrupt discussion.39

The eruption of anger at town hall meetings on health care became a cause célèbre on television. The louder the voices and the fiercer the confrontation, the more coverage the controversy received, obscuring the substantive arguments in favor of what producers love most: conflict. As Fox News broke away from the president’s town meeting in New Hampshire, for example, anchor Trace Gallagher promised his audience, “Any contentious questions, anybody yelling, we’ll bring it to you.”40 When those who became known as the Tea Partyers marched on Freedom Plaza in downtown Washington three days after the president’s address on health care reform to a joint session of Congress on September 9, 2009, they displaced the image of Obama addressing Congress with one of marchers, placards, and populist rage.

Interestingly, anger about the legislative proposals under consideration was not especially widespread. Only 18 percent of the public reported they would be “angry” if health care legislation proposed by the president and Congress was to pass; only half as many (9 percent) said they would be angry if it did not pass. Conservative Republicans were paying more attention than those with other ideological or partisan leanings, and they had the most intense reactions. Thirty-eight percent said they would be “angry” if Congress enacted the Democrats’ reform proposals, while just 13 percent of Democrats said they would be angry if the legislation did not become law. While 19 percent of Independents said they would be angry if the health care bills passed, just 8 percent said they would be angry if the bills did not pass.41

The White House recognized its problems with distractions. In February 2010, aides said the administration was returning to the message discipline that marked the 2008 campaign. It had to filter out unhelpful topics in favor of those that advanced the president’s goals. For example, the plan was for a tighter focus on Obama’s commitment to the economy and jobs for average Americans.42 The administration created a “White House to Main Street” tour, giving Obama a forum to see and feel America’s pain, and offer his plan for relief. Yet because the president refused to give up on health care, a policy not popular with voters, it kept dominating the news and undermining his broader public relations strategy.43

On August 13, 2010, the president entered the fray over the issue of a mosque being built in the vicinity of Ground Zero in New York City, which should have been a local issue. In remarks at a White House Iftar dinner (marking the beginning of the Moslem holy month of Ramadan Kareem), Obama made a strong statement about religious freedom. The next day he appeared to backtrack on the issue, saying he was not advocating a location for the mosque. The day after that, he reaffirmed his original point. These statements were grist for the talk show and cable television mill. Republicans seized upon the issue of the unpopular mosque, increasing the prominence of the president’s words. Many Democrats openly wondered why the White House was wasting news cycles on unimportant skirmishes when it should have been focusing on the economy and jobs in the run-up to midterm elections.

The White House did know how to minimize the president’s media exposure when the topic was one he would rather avoid or that would distract from his media strategy. When Obama lifted travel, gift, and telecommunication restrictions on Cuba on April 13, 2009, the White House deftly limited the visibility of the announcement by leaving the president in the Oval Office and having a mid-level official from the National Security Council make the announcement in the briefing room—in Spanish.

In his first week in office, the president was promoting his economic stimulus package. The White House wanted to discourage coverage of a divisive issue, which ran counter to the week’s message of bipartisanship. Thus, on Friday afternoon, Obama quietly signed an order repealing restrictions on federal money for international organizations that encourage or provide abortions overseas. He acted a day after the anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision establishing a constitutional right to abortion, rather than on the day, which would have attracted considerable attention. He held the signing away from reporters and cameras, issued his comments only in writing, and released the order after 7 p.m. Friday.44 His strategy worked, as the order received little attention.

Another aspect of focus is consistency in message. “Campaign speech is all part of one narrative, but now you are making a series of arguments,” said Obama speechwriter Ben Rhodes. “An argument is a lot clearer to a listener if there is a structure that they can follow. Structure is what allows you to build a case.”45

When the president nominated Sonia Sotomayor to a position on the Supreme Court, the White House sent word to its allies that the last thing the administration needed was a war with conservatives such as Rush Limbaugh and Newt Gingrich over whether the judge was a racist. Stay on message, the president’s aides counseled, and they would offer a clear case about her credentials and legal experience.46

The administration found it difficult to project a consistent message on health care reform. Dan Pfeiffer, the White House communications director, argued, “you can draw a straight line substantively and rhetorically” through all of Obama’s major speeches on health care. Nevertheless, he added, because of the complexity of the issue, “there have been a number of fronts” in the message war that have required the administration’s engagement.47

The White House sought to sell health care reform as a way to make coverage affordable and accessible to middle-class families. Yet at various times it also presented reform as a cost-containment measure, a restraint on greedy insurance companies, a moral imperative to cover the uninsured, a cornerstone of economic recovery, and, to Democratic lawmakers, an enterprise at which the party could not afford to fail. The president and his aides sent mixed signals on the “public option” as well, voicing support for a government-run plan while signaling their willingness to see it die to get a bill passed. The president also abandoned his opposition to a requirement that everyone have insurance, known as an individual mandate, and signaled a willingness to consider financing schemes, including tax increases, that originally were not on his agenda. Moreover, perhaps to lower expectations, administration officials began speaking of putting the nation on a “glide path” to universal coverage rather than the insurance-for-all trumpeted by many Democrats.48

It is also difficult to coordinate supporters around a message.49 A campaign team has near-total control over its message. A White House does not. “When it’s either legislative strategy or regulatory strategy, you have to cede a considerable amount of control to people who don’t share your interest, even if they’re in your party,” said Dan Bartlett, communications director in George W. Bush’s White House.50

Through most of the summer, opposition to the president’s health care initiative came almost entirely from the right. By mid-August, however, there was a growing concern among Obama’s progressive allies that he was prepared to deal away the public insurance option to win passage of a health care bill. Obama insisted that he still preferred the public option as part of any legislative package, but many on the left doubted his resolve. Liberal commentators, progressive bloggers, and grassroots activists raised their concerns about Obama’s health care policy and the deals he appeared to be striking with the health care industry—as well as on his increased troop commitment in Afghanistan and his stances on detainees and torture policy. The president’s advisors acknowledged that they were unprepared for this intraparty rift. Rather than selling middle-class voters on how insurance reforms would benefit the public, the White House instead found itself mired in a Democratic Party feud over an issue it never intended to spotlight.51

There is little the White House can do to limit the overall volume of messages that citizens encounter or to make the public more attentive to politics, and it has limited success in influencing the media’s agenda. Yet it still must try to reach the public with its message and break through the public’s disinterest in politics and the countless distractions from it.

It is likely that reaching the public will require frequent repetition of the president’s views. According to George W. Bush, “In my line of work you got to keep repeating things over and over and over again for the truth to sink in, to kind of catapult the propaganda.”52 Given the protracted nature of the legislative process, and the president’s need for public support at all stages of it, sustaining a message can be equally important as sending it in the first place. As former White House public relations counselor David Gergen put it, “History teaches that almost nothing a leader says is heard if spoken only once.” Administrations attempt to establish a “line of the day” so that many voices echo the same point.53

The lack of interest in politics of most Americans, as evidenced by the low turnouts in elections, compounds the challenge of reaching the public. Policymaking is a complex enterprise, and most voters do not have the time, expertise, or inclination to think extensively about most issues. In fact, people generally have only a few issues that are particularly important to them and to which they pay attention.54 The importance of specific issues to the public varies over time and is closely tied to objective conditions such as unemployment, inflation, international tensions, and racial conflict. In addition, different issues are likely to be salient to different groups in the population at any given time. For example, some groups may be concerned about inflation, others about unemployment, and yet others about a particular aspect of foreign policy or race relations.55

A hallmark of the contemporary presidency is the White House’s failure to draw impressive audiences for nationally televised speeches. Although wide viewership was common during the early decades of television, when presidential speeches routinely attracted more than 80 percent of those watching television, recent presidents have seen their audiences decline to the point where less than half of the public—often substantially less—watch their televised addresses.56 Paradoxically, developments in technology have allowed the president to reach mass audiences, yet further developments have made it easier to for these same audiences to avoid listening to the White House. Cable television57 and news networks provide alternatives that make it easy to tune out the president. The average home received 118 channels in 2009.58

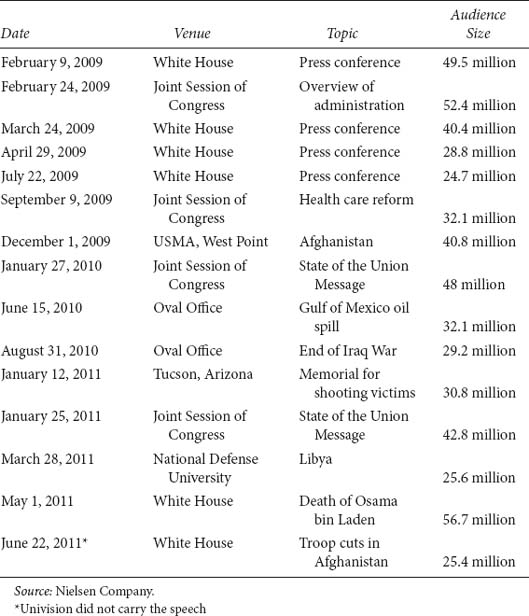

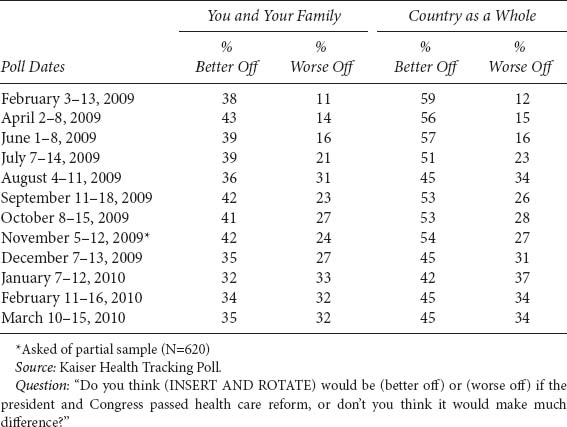

TABLE 2.1.

Audiences for Obama Nationally Televised Speeches and Press Conferences

Table 2.1 shows the audiences for President Obama’s nationally televised prime-time formal events. Although many people did choose to watch the president speak, the great majority of people did not—even for major addresses. Moreover, as the novelty of the new president wore off, the audiences for his prime-time televised addresses (except for his State of the Union messages) and press conferences steadily declined.

Less formal events drew smaller audiences. His March 19, 2009, appearance on the Tonight Show drew 12.8 watchers; and an interview on 60 Minutes drew 16.2 million viewers.59 These were good ratings for the programs, but reached a small fraction of the public. By June 24, 2009, ABC’s Primetime special featuring a town hall discussion about health care with the president attracted just 4.7 million viewers.60 A presidential appearance on the daytime talk show, The View, in July 2010, drew 6.6 million viewers.61 Nevertheless, the president felt he had to exploit a range of venues to reach the public. As he put it in an interview on 60 Minutes, “it used to be a President could call a press conference, and the three major networks would come, and he’d talk to ‘em, and you pretty much reached everybody in America. . . . But there are a whole bunch of folks . . . who watch The Daily Show, or watch The View. And so I’ve got to adapt the presidency to reach as many people as possible in as many settings as possible so that they can hear directly from me.”62

Commentary cascades from the White House. One official estimated that the White House produces as many as five million words a year in the president’s name in outlets such as speeches, written statements, and proclamations.63 Wide audiences hear only a small proportion of the president’s statements, however. Comments about policy proposals at news conferences and question and answer sessions and in most interviews are also usually brief and made in the context of a discussion of many other policies. Written statements and remarks to individual groups may be focused, but the audience for these communications is modest. In addition, as David Gergen puts it, nearly all of the president’s statements “wash over the public. They are dull, gray prose, eminently forgettable.”64

The public can miss the point of even the most colorful rhetoric. In his 2010 State of the Union address, President Obama declared that as part of their economic recovery, his administration had passed twenty-five different tax cuts. “Now, let me repeat: We cut taxes,” he said. “We cut taxes for 95 percent of working families. We cut taxes for small businesses. We cut taxes for first-time homebuyers. We cut taxes for parents trying to care for their children. We cut taxes for 8 million Americans paying for college.” In his Super Bowl Sunday interview with Katie Couric, he touted the tax cuts in the stimulus package: “we put $300 billion worth of tax cuts into people’s pockets so that there was demand and businesses had customers.” (The only tax increases passed in 2009 were on tobacco.)

Shortly afterward, a major polling organization asked, “In general, do you think the Obama Administration has increased taxes for most Americans, decreased taxes for most Americans or have they kept taxes the same for most Americans?” Twenty-four percent of the public responded that the administration had increased taxes, and 53 percent said it kept taxes the same. Only 12 percent said taxes were decreased.65 In July, that figure dwindled to 7 percent of the public.66 Misperceptions only grew as the midterm elections approached. In September, 33 percent of the public thought that Obama had raised taxes for most Americans.67 By the end of October, 52 percent of likely voters thought taxes had gone up for the middle class.68

On the other hand, only 34 percent of the public knew the unpopular bailout of banking and financial institutions (known as TARP) was passed under George W. Bush. Nearly half (47 percent) thought it passed during Obama’s presidency.69 Even though the White House announced in October 2010 that the federal government would actually turn a profit on these funds, 60 percent of likely voters at the end of the month thought most of the money was lost. Despite the fact that the economy had been growing for over a year, 61 percent thought it had been shrinking.70

David Axelrod lamented, “For me, the question is, why haven’t we broken through more than we have? Why haven’t we broken through?”71 But the problems continued. Perceptions of the president’s religion were closely linked to his job approval, and those who did not know Obama was a Christian were highly unlikely to approve of his job performance. In August 2010, 18 percent of the public thought the president was a Muslim, up from 11 percent in March 2009. Another 43 percent did not know Obama’s religion (an increase from 32 percent in March 2009). Only 34 percent of the public knew he was a Christian, down from 48 percent in March 2009.72

It is important not only to reach the public, but also to reach it in a timely fashion. As Anita Dunn, the first director of communications in the Obama White House, put it, once a story gains traction, the administration needs to respond quickly or “rumors become facts.”

In the summer of 2009, Betsey McCaughey voiced the false claim that the health care legislation in Congress would result in seniors being directed to “end their life sooner.”73 Numerous conservative pundits and Republican members of Congress quickly parroted her claim, including Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, Fred Thompson, Laura Ingraham, the New York Post, Wall Street Journal, Washington Times, and Fox News. The myth reached its peak after Sarah Palin embellished it on her Facebook posting on August 7, 2009, denouncing government “death panels.” Palin’s comments created a media frenzy. In the ten days after her initial statement, Washington Post media critic Howard Kurtz counted 18 mentions of “death panels” in the Post, 16 in the New York Times, and more than 154 on network and cable news shows.74

The White House did not respond to Palin until four days after her Facebook posting, when Obama addressed the issue in a town hall meeting in New Hampshire. At the same time, the White House established a “Reality Check” blog on which officials challenged assertions they considered to be false. One prominent media observer termed this a “tepid” means of responding.75

In the meantime, the false charge of the fictitious death panels had gained traction in the conservative media and received widespread attention. By mid-August, fully 86 percent of the public reported hearing either a lot (41 percent) or a little (45 percent) about “death panels.” Among those who had heard about death panels, 50 percent said correctly that the claim was not true, but a sizable minority (30 percent) believed that health care legislation would create such organizations (20 said they did not know). Nearly half of Republicans (47 percent) were misinformed, as were 45 percent of those who reported regularly receiving their news from Fox News.76 Another mid-August poll found that 45 percent of those surveyed believed the Democrats’ bill would “allow the government to make decisions about when to stop providing medical care to the elderly,” a figure that rose to 75 percent among Fox News viewers.77

A good example of the problems of reaching the public is health care reform, the president’s highest legislative priority in his first year in office. The White House was aggressive in its public advocacy of reform. The president alone made fifty-two public addresses or statements specifically on his health care proposals during his first year in office.78

SUMMER AWAKENING Mindful of the failures of former President Bill Clinton, who produced an extraordinarily specific plan for health care in 1993, Obama insisted he would leave the details of health care reform to Congress. He set forth broad principles and concentrated on bringing disparate factions—doctors, insurers, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, labor unions—to the negotiating table. By June, however, the president grew concerned that he was losing the debate over certain policy prescriptions he favored, like a government-run insurance plan to compete with the private sector. With Congress beginning serious work on the measure, the president concluded that he had to exert greater control over the health care debate.79

Worried about the lack of public support for health care reform, the White House arranged with ABC News for a prime-time program on June 24, 2009, Questions for the President: Prescription for America (with a follow-up session on Nightline) that allowed the president to explain his health care proposal to the public yet again. Only 4.7 million viewers tuned in, however, nearly 3 million fewer than a competing repeat of CBS’s crime series, CSI: New York.80 On July 1, Obama held a town hall–style meeting on health care in Virginia—his second town hall meeting in two weeks.

Yet the polls kept getting worse for the administration. With skepticism about the president’s health care reform effort mounting on Capitol Hill—even within his own party—the White House moved its public relations effort into high gear in late July. In the words of the Washington Post, it was “all Obama, all the time.” Senior White House aides promised an aggressive public and private schedule for Obama as he pressed his case for reform. “Our strategy has been to allow this process to advance to the point where it made sense for the president to take the baton. Now’s that time,” said senior advisor David Axelrod on July 19, “he’s going to be very, very visible.”81

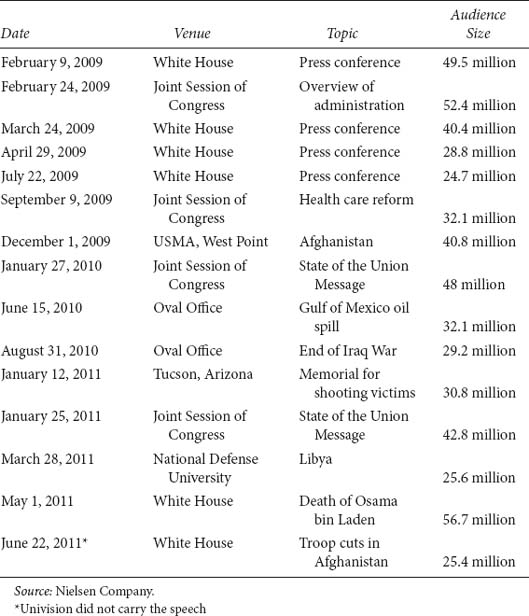

TABLE 2.2.

Going Public on Health Care: Mid-Summer 2009

We can see in table 2.2 what Axelrod meant. The president traveled, made public statements, gave interviews, held town meetings and a prime-time press conference, delivered a radio address, and released statements and reports on health care. In addition, the White House made heavy use of Internet video to broadcast the president’s message beyond the reach of the traditional media. For example, the administration sponsored a live video chat with Nancy-Ann DeParle, Obama’s health policy czar, on Facebook and on the Web site, WhiteHouse.gov. Meanwhile, Organizing for America, the group run by the Democratic National Committee to rally support for Obama’s agenda, declared this week “Health Care Reform Week of Action” and asked millions of supporters to sign up for events in their neighborhoods.

AUGUST RECALIBRATION Nothing seemed to work, however. Democratic Party officials acknowledged that the growing intensity of the opposition to the president’s health care plans had caught them off guard and forced them to begin an August counteroffensive.82 The president and his proxies launched a blitz of town hall meetings, grassroots lobbying, and television advertising designed to rally public support for quick votes on health plans in the House and Senate following the August congressional recess. The president held town hall meetings in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Bozeman, Montana, and Grand Junction, Colorado, and wrote an op-ed in the New York Times.

One aspect of the new strategy was geared toward reenergizing Web-savvy allies who backed Obama in the election. The president appeared in a six-minute video on the WhiteHouse.gov Web site, recounting some of the personal stories of average Americans. On August 20, he held a conference call with grassroots supporters hosted by Organizing for America during which an estimated 280,000 people dialed in.83

The effort by the president to create new momentum came as the Democratic National Committee and Organizing for America encouraged volunteers to fan out across the country to sway reluctant lawmakers to support the proposals moving through Congress. They also enlisted supporters to attend public events with members of Congress to counterbalance the sometimes angry outbursts from opponents.84

Reprising a strategy from the campaign, the White House began responding to attacks in the same medium in real time. Thus, on August 4, the White House reacted quickly with its own three-minute video in response to a Web video that officials said misrepresented the president’s health care plan. The administration’s video did not only appear on the White House Web site (http.whitehouse.gov) but was also promoted on Facebook and Twitter and sent to those on the e-mail list on www.healthreform.gov.

As part of the White House’s rapid-response effort, on August 4, it launched an e-mail tip line where people could report “disinformation about health insurance reform.” The effort quickly sparked concern among Republicans about the government collecting information on private citizens’ political speech, however, and the administration shut it down after two weeks.

On August 10, the White House also launched a new online “Health Insurance Reform Reality Check” on its Web site, featuring administration officials rebutting questionable but potentially damaging charges that President Obama’s proposed overhaul of the nation’s health care system would inevitably lead to “socialized medicine,” “rationed care,” and even forced euthanasia for the elderly.

As members of Congress left for their August recess, advertisements followed them. Groups saturated the airwaves with tens of millions of dollars in advertisements for and against health care reform. Much of the advertising was focused on wavering members of Congress and members from electorally competitive districts and states. Tellingly, the Campaign Media Analysis Group estimated that most of the advertising by early August had broadly favored overhauling the health care system.85 Nevertheless, the public had become less supportive.

The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America joined the nonprofit group Families USA to air an updated version of the iconic “Harry and Louise” ads, but this time the couple called for passage of reform. Conservative groups like the Club for Growth, Americans for Prosperity, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Conservatives for Patients’ Rights, and, especially, the Republican National Committee ran ads against reform, while Americans United for Change, organized labor, including the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (which represents health care workers), MoveOn.org, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, Organizing for America, the powerful seniors lobby AARP, the American Nurses Association, and the American Medical Association sponsored advertisements in favor of reform.

By mid-August, health care reform was receiving the most attention in the news and was the story the public was following the most closely. This was not always an advantage for the president, however. Democrats had not anticipated Republicans and their allies hurling incendiary accusations that the Obama plan would empower “death panels,” help illegal immigrants, and raid Medicare.

SEPTEMBER OFFENSIVE Following the Labor Day holiday, Obama renewed his public relations offensive. Given the high stakes of passing health care reform and the downturn in public opinion about it, the president turned to what many considered the most powerful weapon in his arsenal—a nationally televised evening address before a joint session of Congress. As we have seen, Obama’s speech was unusual. Presidents rarely focus such a nationally televised address on an issue before Congress.86

Obama had to reassure progressive activists that he had not lost his passion for reform, so his speech contained tough talk and denunciations of false or misleading claims that opponents had made about the legislation in Congress. The president knew, of course, that there was little possibility of moving Republicans from opposition to support. He had to reach the center of the electorate. It was this segment of the public that had become worried about the scope and nature of the president’s proposal. Thus, much of his rhetoric provided reassurance and reflected an orientation toward compromise and bipartisanship.

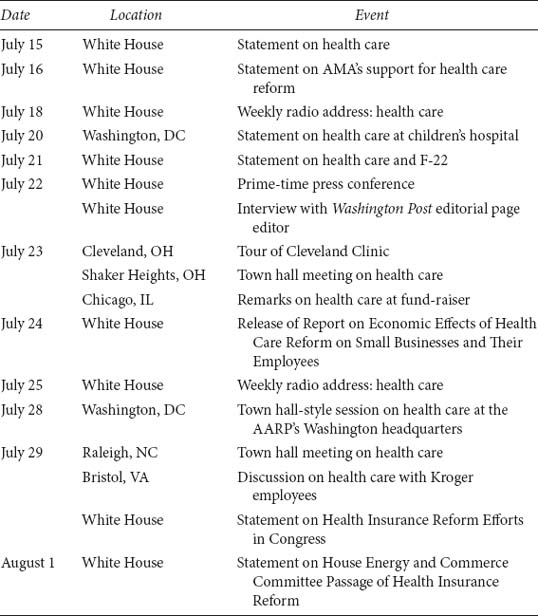

TABLE 2.3.

Going Public on Health Care: Mid-September 2009

Obama’s audience was 32.1 million people, a large number to be sure, but only a small portion of the public and down from about 52 million for his February address to a joint session of Congress.87 The Fox broadcast network chose not to televise the president’s speech (although the Fox News channel did).

Obama followed up his speech with a series of speeches, interviews, and television appearances over the next two weeks, culminating in an unprecedented set of appearances on five Sunday interview shows on the same day (see table 2.3).

The president was so active in advocating health care reform in September that some commentators suggested he was in danger of overexposure. The White House disagreed. “The idea of overexposure is based on an old-world view of the media,” said Dan Pfeiffer, the White House’s deputy communications director. Because the media are now so fragmented, “you would have to do all the Sunday shows, a lot of network news shows and late-night shows” to reach the number of viewers a president could address with one network interview twenty years ago.88 According to an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll of September 17–20, 54 percent of the public said they were seeing and hearing Obama the right amount and only 34 percent (mostly Republicans) said they were seeing and hearing him too much. A majority of Independents, 52 percent, said Obama had the right amount of exposure.

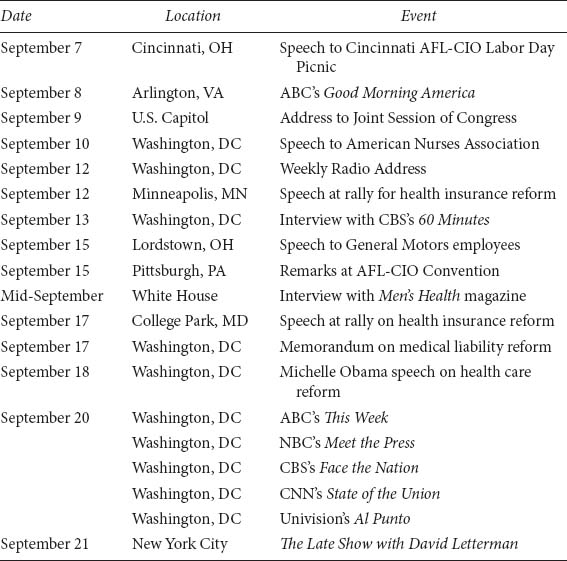

TABLE 2.4.

Evaluations of Impact of Health Care Reform

By mid-October, the president lowered his profile on health care. The White House plan was for Obama to take a breather while Democrats resolved their internal conflicts. Then he was to come back strong with a fresh sales pitch when the legislation moved closer to floor votes.89

CONTINUED SLIPPAGE The trends in evaluation of the overall effects of health care reform continued to worsen. Table 2.4 shows that the percentage of the public concluding that health care reform would make them and their families as well as the country as a whole worse off moved against the president. In the months leading up to the final votes on the health care reform in 2010, only about one-third of the people felt reform would benefit themselves and their families.90 This low level of support added to the burdens of passing non-incremental change.

Perhaps most frustrating to the White House was the inability to clarify mistaken notions about its proposal that were damaging its case. In mid-September, 26 percent of respondents still believed that health care legislation would create organizations to decide when to stop providing medical care to the elderly—the so-called death panels—despite an all-out effort by Obama to debunk the false claim. Similarly, 30 percent said the bill would use taxpayer money to provide health care benefits to illegal immigrants despite the president specifically affirming that it would not.91

The president just could not break through. In early September, 67 percent of the respondents to a national poll said the issue was difficult to understand.92 At the end of an interview with George Stephanopoulos on ABC’s This Week on September 20, 2009, the president reflected on his leadership of the public regarding health care.

There have been times where I have said I’ve got to step up my game in terms of talking to the American people about issues like health care. . . . I’ve said to myself, somehow I’m not breaking through. . . . this has been a sufficiently tough, complicated issue with so many moving parts that . . . no matter how much I’ve . . . tried to keep it digestible, . . . it’s very hard for people to get their . . . whole arms around it. And that’s been a case where I have been humbled.93

(In July 2010, 41 percent of the public still believed the law allowed a government panel to make decisions about end-of-life care for people on Medicare and an additional 16 percent said they did not know.)94

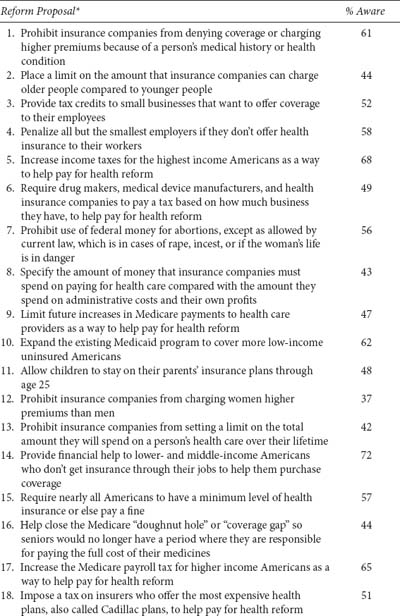

In January 2010, as the debate on health care reform was reaching its final stages, large segments of the public still were unaware of major elements of the Democratic proposal (see table 2.5).95 In addition, only 59 percent of the public understood that most people could keep their employer-provided insurance if health care reform passed.96 Small businesses did not know about subsidies for them, seniors did not know the bill closed the “donut hole” on prescription drugs, and young adults did not know they could stay on their parents’ health insurance policies until they were twenty-six.97 Unaware of the benefits of health care reform and concerned about losing the benefits they already had, it is little wonder that many in the public opposed the president.

More than a year after the bill passed, the Kaiser Foundation found in June 2011 that most Americans were unaware that the health care reform law would close the Medicare “doughnut hole” on prescription drugs, eliminate co-pays and deductibles for many preventative services under Medicare, and develop ways to improve health care delivery. On the other hand, 31 percent of the public incorrectly believed the law allowed a government panel to make decisions about end-of-life care for people on Medicare—and another 20 percent were unsure. Forty-eight percent incorrectly felt the law would cut benefits that were previously provided to all people on Medicare, and another 17 percent were uncertain.98

TABLE 2.5.

Awareness of Health Care Proposals

Although technological change has made it more difficult for the president to attract an audience on television, other changes may have increased the White House’s prospects of reaching the public. Teddy Roosevelt gave prominence to the bully pulpit by exploiting the hunger of modern newspapers for national news. Franklin D. Roosevelt broadened the reach and immediacy of presidential communications with his use of radio. More recently, John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan mastered the use of television to speak directly to the American people. Now Barack Obama has positioned himself as the first Internet president.

On November 18, 2008, about 10 million of Barack Obama’s supporters found an e-mail message from his campaign manager, David Plouffe. Labeled “Where we go from here,” Plouffe asked backers to “help shape the future of this movement” by answering an online survey, which in turn asked them to rank four priorities in order of importance. First on the list was “Helping Barack’s administration pass legislation through grassroots efforts.”99

Plouffe’s e-mail message revealed much about Barack Obama’s initial approach to governing. The new administration was oriented to exploiting advances in technology to communicate more effectively than ever with the public. Bush State Department spokesman Sean McCormack started filing posts from far-flung regions during trips with his boss, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. On October 31, 2008, McCormack unveiled “Briefing 2.0” in the press briefing room of the State Department in which he took questions from the public rather than the press and then put the session on YouTube.100

In 2009, the new occupants of the White House were oriented to exploiting the emerging technology more systematically than their predecessors. Obama announced his intent to seek the presidency via Web video, revealed his vice presidential selection via text message, recruited about 13 million online supporters during the campaign, and used the electronic medium to sidestep mainstream media and speak directly with voters throughout the primaries and general-election campaign. This practice forged a firsthand connection and may have encouraged some supporters to feel they had a greater stake in the campaign’s success. Some Obama videos have become YouTube phenomena: millions of people have viewed his speech on the Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr. and race in America and his victory speech in Grant Park on November 4, 2008.

“It’s really about reaching an extra person or a larger audience of people who wouldn’t normally pay attention to policy,” said Jen Psaki, a spokeswoman for Obama’s transition team. “We have to think creatively about how we would do that in the White House, because promoting a speech in front of 100,000 people is certainly different than promoting energy legislation.”101

Even before taking office, the president-elect began making Saturday radio addresses—but with a twist. In addition to beaming his addresses to radio stations nationwide, he recorded them for digital video and audio downloads from YouTube, iTunes, and the like. As a result, people could access it whenever and wherever they wanted. “Turning the weekly radio address from audio to video and making it on-demand has turned the radio address from a blip on the radar to something that can be a major newsmaking event any Saturday we choose,” declared Dan Pfeiffer, the incoming White House deputy communications director. Videos are also easy to produce: a videographer can record Obama delivering the address in fewer than fifteen minutes.102 After his inauguration, the White House put the president’s Saturday videos on both the White House Web site and a White House channel on YouTube. However, between May 2009 and November 2010, no video had more than 100,000 views and most had close to 20,000.103

The Obama White House produces and distributes much more video than any past administration. To do so, it maintains a staff devoted to producing online videos for whitehouse.gov, Obama’s YouTube channel, and other video depots. A search for “Barack Obama” is stacked with videos approved and uploaded by the campaign or the administration (which viewers may not realize). When filming a presidential speech, the production team tailors the video to the site, with titles, omissions, crowd cutaways, highlight footage, and a dozen other manipulations of sound and image that affect the impression they make, including applause that is difficult to edit out.104 The president’s YouTube channel had more than 650 video uploads in its first year. The administration also holds regular question-and-answer Webcasts with policy officials on WhiteHouse.gov.105

In addition, the administration introduced West Wing Week, a video blog consisting of six- to seven-minute compilations that appear each week on the White House’s Web site and on such video-sharing sites as YouTube. They offer what a narrator on each segment calls “your guide to everything that’s happening at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.”

The Obama White House wants to flood niche media markets via blogs, Twitter feeds, Facebook pages, and Flicker photo streams.106 To exploit more fully developments in communications technology, the White House established an Office of New Media. It regularly alerts its 1.7 million Twitter followers of the president’s policy stances.107 When he nominated Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, Obama sent a video appealing for support for his candidate to the huge e-mail list accumulated during his campaign and the Democratic Party’s own lists. The e-mail message included a directive from the president to share his views via Facebook, Twitter, and other Web connections.108

Politico.com is the most prominent face of the new media at the White House. It is a bulletin board of the stories on which the media is focused and what is happening in Washington on a given day. The White House starts communicating with Mike Allen, Politico’s chief White House correspondent, at 5 a.m. to try to influence what others will view as important. It also uses Politico as a forum to rebut directly its adversaries in front of the rest of the news media.109

The Internet, which emerged in 2008 as a leading source for campaign news, has now surpassed all other media except television as a main source for national and international news. More people now say they rely mostly on the Internet for news rather than newspapers.110 Young people are even more likely to report that they rely on the Internet as a main source of national and international news. Overall, 61 percent of Americans now use the Internet as a daily news source.111

Obama made the case for his economic agenda in a variety of forums, including the Tonight Show, 60 Minutes, and a prime-time news conference. On March 26, 2009, he added a new arrow to his quiver. The president held an “Open for Questions” town hall meeting in the East Room of the White House. Bill Clinton and George W. Bush answered questions over the Internet, but Obama was the first to do so in a live video format, streamed directly onto the White House Web site.

For more than an hour, the president answered questions culled from 104,000 sent over the Internet. Online voters cast more than 3.5 million votes for their favorite questions, some of which were then posed to the president by an economic advisor who served as a moderator. The president took other queries from a live audience of about 100 nurses, teachers, businesspeople, and others assembled at the White House.

The questions covered topics such as health care, education, the economy, the auto industry, and housing. In most cases, Obama used his answers to advocate his policies. Although the questions from the audience in the East Room were mostly from campaign backers, the White House was not in complete control of the session. One of the questions that drew the most votes online was whether legalizing marijuana might stimulate the economy by allowing the government to regulate and tax the drug. (The White House listed the question on its Web site under the topics “green jobs and energy” and “budget.” White House officials later indicated that interest groups drove up those numbers.)112

On February 1, 2010, the president sat for a first-of-its-kind group interview with YouTube viewers, who submitted thousands of questions and heard the president answer some in a live Webcast. YouTube viewers voted for their favorite questions, and Steve Grove, the head of news and politics at YouTube, selected the ones to ask in the half-hour session.

In April 2011, Obama sat down with Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and answered questions from Zuckerberg and Facebook users. The president next turned to Twitter. On July 6, 2011, he held the first Twitter town hall meeting, live from the East Room of the White House. The hour-long session involved the president answering questions submitted by Twitter users and selected in part by 10 Twitter users around the country picked by Twitter. Twitter’s chief executive, Jack Dorsey, moderated the session.

When the Obama White House texts its supporters, it is preaching to the choir. There is nothing wrong with that. Perhaps the first rule in the politics of coalition building is solidifying the base. Yet, the base can only take you so far. Obama received about 53 percent of the national vote, and some of that support was certainly a negative response to George W. Bush in general and bad economic times in particular. It would be an exaggeration to conclude that Obama’s base includes even half the public. Moreover, once Obama took office, Bush was gone and the public began reacting to the new president.

Moreover, widespread home broadband and mobile access to the Internet has created the potential for people to communicate easily with each other as well as to receive communications from leaders. Conservatives can exploit this technology to reinforce their opposition to the new administration. Equally important, however, is the potential for liberals to use the new technologies to oppose the president’s evident pragmatism and tendencies toward moderation.

Communications technology users glory in the freedom to dissent that is at the heart of blogging. Even during the transition, there were hints of conflict within the base. Candidate Obama allowed his supporters to wage an online revolt—on his own MyBarackObama.com Web site—over his vote in favor of legislation granting legal immunity to telecommunications firms that participated in the Bush administration’s domestic wiretapping program. President-elect Obama, however, did not provide a forum for comments on his YouTube radio address, prompting grumbling among some in the netroots crowd that YouTube without comments was no different from radio.113

Internet users are creative, however. The day after Obama announced that the Rev. Rick Warren would deliver the opening prayer at his inauguration, a discussion forum focused on community service instead filled with pages of comments from people opposing the choice. In early January, visitors to Change.gov, the transition Web site, voted a question about whether Obama would appoint a special prosecutor to investigate possible Bush administration war crimes to the top of the questions submitted to the new administration. Progressive Web sites blasted the new administration’s efforts to dodge the issue. Within a day, MSNBC’s Keith Olbermann picked up the story. A day later, Obama was compelled to answer the question in an interview with ABC’s George Stephanopoulos, who quoted it and pressed Obama with two follow-ups. Obama’s answer, which prioritized moving “forward” but did not rule out a special prosecutor, made the front page of the January 12 issue of the New York Times.

Dissent among liberals did not end with the transition. For example, Move On.org, one of Obama’s staunchest supporters during the 2008 campaign, called on its members in April 2010 to telephone the White House and demand that Obama reinstate the ban on offshore oil drilling that he had ended.114

Reaching people is useful for political leaders, but mobilizing them is better. Plouffe’s emphasis on helping the Obama administration pass legislation through grassroots efforts indicates a desire to use public backing to move Congress to support the president’s program. According to Andrew Rasiej, co-founder of the Personal Democracy Forum, a nonpartisan Web site focused on the intersection of politics and technology, Obama “created his own special interest group because the same people that made phone calls on behalf of him [in the campaign] are now going to be calling or e-mailing their congressman.”115 A Pew study during the transition found that among those who voted for Obama, 62 percent expected to ask others to support at least some of the new administration’s policies.116

Plouffe did not take a formal role in the White House until 2011. He did, however, remain as an advisor and began overseeing the president’s sprawling grass-roots political operation, which at the time boasted 13 million e-mail addresses, 4 million cell phone contacts, and 2 million active volunteers.117 More than 500,000 people completed surveys following the election to express their vision for the administration, and more than 4,200 hosted house parties in their communities. On January 17, 2009, Obama sent a YouTube video to supporters to announce plans to establish Organizing for America (OFA), which was to enlist community organizers around the country to support local candidates, lobby for the president’s agenda, and remain connected with his supporters from the campaign. There was speculation that the organization could have an annual budget of $75 million in privately raised funds and deploy hundreds of paid staff members. It was to operate from the Democratic National Committee headquarters but with an independent structure, budget, and priorities.118 (By 2010, OFA had virtually supplanted the party structure. It sent about 300 paid organizers to the states, several times the number the national party hired for the 2006 midterms.)119

During the transition, the Obama team drew on high-tech organizational tools to lay the groundwork for an attempt to restructure the U.S. health care system. On December 3, 2008, former Democratic Senate majority leader Thomas Daschle, Obama’s designee as secretary of Health and Human Resources and point person on health care, launched an effort to create political momentum when he held a conference call with one thousand invited supporters who had expressed interest in health issues, promising it would be the first of many opportunities for Americans to weigh in. In addition, there were online videos, blogs, and e-mail alerts as well as traditional public forums. Thousands of people posted comments on health on Change.gov, the Obama transition Web site, which encouraged bloggers to share their concerns and offer their solutions regarding health care policy.120

According to Rasiej, “It will be a lot easier to get the American public to adopt any new health-care system if they were a part of the process of crafting it.” Simon Rosenberg, president of the center-left think tank NDN, was more expansive: “This is the beginning of the reinvention of what the presidency in the 21st century could be.” “This will reinvent the relationship of the president to the American people in a way we probably haven’t seen since FDR’s use of radio in the 1930s.”121

Democratic political consultant Joe Trippi took the argument a step further, observing, “Obama will be more directly connected to millions of Americans than any president who has come before him, and he will be able to communicate directly to people using the social networking and Web-based tools such as YouTube that his campaign mastered.” “Obama’s could become the most powerful presidency that we have ever seen,” he declared.122 Republican strategist and the head of White House political operations under Ronald Reagan, Ed Rollins, agreed. “No one’s ever had these kinds of resources. This would be the greatest political organization ever put together, if it works” (italics added).123

Whether it would work was indeed the question. To begin, Obama’s team found it difficult to adapt its technologically advanced presidential campaign to government. The official Web site, WhiteHouse.gov, was to be the primary vehicle for President Obama to communicate with the masses online. Yet the White House lacks the technology to send mass e-mail updates on presidential initiatives. The same is true for text messaging, another campaign staple. The White House must also navigate security and privacy rules regarding the collection of cell phone numbers.124 In addition, there are time-consuming legal strictures such as a requirement in the Presidential Records Act to archive Web pages whenever they are modified, in order to preserve administration communications. Moreover, the White House cannot engage in overt politicking or fundraising on a government Web site.

The Organizing for America team held several dry runs to test the efficacy of their volunteer apparatus, including a call for supporters to hold “economic recovery house meetings” in February to highlight challenges presented by the recession. The house parties were designed to coincide with the congressional debate over Obama’s stimulus package and had mixed results. Although OFA touted the 30,000 responses the e-mail drew from the volunteer community and the more than 3,000 house parties thrown in support of the stimulus package, a report in McClatchy Newspapers indicated that many events were sparsely attended.125

The first major engagement of OFA in the legislative process began on March 16, 2009. An e-mail message was sent to volunteers, asking them to go door to door on March 21 to urge their neighbors to sign a pledge in support of Obama’s budget plan. A follow-up message to the mailing list a few days later asked volunteers to call the Hill. A new online tool on the DNC/OFA Web site aided constituents in finding their congressional representatives’ contact information so they could call the lawmakers’ offices to voice approval of the proposal.

The OFA reported that its door-to-door canvass netted about 100,000 pledge signatures, while another 114,000 signatures came in through its e-mail network. Republicans scoffed at the effort, arguing that this proved that even the most die-hard Obama supporters were uncertain about the wisdom of the president’s budget plan. Several GOP aides noted that the number of pledges gathered online amounted to fewer than 1 percent of the names on Obama’s vaunted e-mail list. The Washington Post reported that interviews with congressional aides from both parties found the signatures swayed few, if any, members of Congress.126

By June, OFA was the Democratic National Committee’s largest department, with paid staff members in thirty-one states and control of the heavily trafficked campaign Web site. Public discourse on health care reform was focusing on the high costs and uncertain results of various proposals. Remembering the “Harry and Louise” television ads that served as the public face of the successful challenge to Bill Clinton’s health reform efforts, the White House knew it had to regain momentum. Thus, the president e-mailed millions of campaign supporters, asking for donations to help in the White House’s largest-ever issues campaign and for “a coast-to-coast operation ready to knock on doors, deploy volunteers, get out the facts,” and show Congress people wanted change. The DNC deployed dozens of staff members and hundreds of volunteers to thirty-one states to gather personal stories and build support.127

In late June, the DNC reported roughly 750,000 people had signed a pledge in support of the president’s core principles of reducing cost, ensuring quality, and providing choice, including a public insurance option; 500,000 volunteered to help; and several hundred thousand provided their own story for the campaign’s use. OFA posted thousands of personal stories online to humanize the debate and overcome criticism of the president’s plan. It also trained hundreds of summer volunteers and released its first Internet advertisement—a Virginia man explaining that he lost his insurance when he lost his job.128

As the health care debate intensified in August, the president again turned to the OFA for support. Obama sent an e-mail to OFA members: “This is the moment our movement was built for,” he wrote. He also spent an hour providing bullet points for the health care debate during an Internet video. OFA asked its volunteers to visit congressional offices and flood town hall meetings in a massive show of support.129 There is no evidence that this show of strength ever materialized.

By August, Organizing for America reported paid political directors in forty-four states. Nevertheless, it had to moderate its strategy. In response to Democrat complaints to the White House about television commercials on health care, climate change, and other issues broadcast in an effort to pressure moderates to support the president’s proposals, the group started running advertisements of appreciation. It also found that its events around the country were largely filled with party stalwarts rather than the army of volunteers mobilized by the 2008 campaign.130

Despite some success in generating letters, text messages, and phone calls on behalf of health care reform, OFA was not a prominent presence in 2009.131 In response to the lack of action, in 2010 organizers held hundreds of sessions across the nation intended to re-engage the base from 2008.132