States’ support for the Arms Trade Treaty and “responsible” arms export controls belies long-standing expectations. Conventional weapons play a vital role in national and international security and present a hard case for international commitment. Until the late 1990s, conventional arms sales remained the prerogative of national foreign and economic policy. Whether arms were used to influence allies or to support domestic economic interests, recipients’ human rights were not considered, conflict was a concern for only a handful of suppliers,1 and material interests dominated export decision making. For the most part, states pushed away multilateral efforts to impose controls on major conventional arms sales and divorced national policy from any restrictive international standards or obligations. Small arms were absent entirely from the international agenda. Even initial post–Cold War optimism for a transfer control regime2 quickly faded “in the face of desperate competition between supplier states for a share of the … dwindling international market” (Spear 1994:99). With the often close relationship of governments and defense industries, along with deep concerns for state sovereignty and security, such a stalemate was hardly surprising—nor have these relationships and concerns disappeared over time.

Since the late 1990s, however, material pressures to export have increasingly had to coexist with normative pressures to control. Conventional arms transfers have been found to undermine human rights, governance, social and economic development, domestic and international stability, and postconflict reconstruction. By 2006, states had reached numerous regional and international agreements reflecting these concerns and voted to begin a formal process at the UN to create an ATT (see appendix A for the history of related agreements).3 Many suppliers had also adopted national “responsible” arms transfer controls, focused in particular on their import partners’ human rights practices. These initiatives culminated in the UN Arms Trade Treaty, which lays out the first-ever legally binding global humanitarian standards for small and major conventional arms exports. In 2013, a total of 154 member states voted to approve the ATT, with only Iran, North Korea, and Syria opposing it. Most major supplier states—including the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—once considered external export restrictions too costly but now count themselves among supporters of multilateral humanitarian export controls.

How did this policy transformation come to pass, what makes it so dramatic, and how well does it reflect states’ existing arms export practice? This chapter analyzes the changing contours of the international normative environment for conventional arms exports in three main parts. In essence, it charts the “business as usual” of the global arms trade over time. In the first section, I provide an overview of the twentieth century’s failed multilateral attempts to control arms exports. This section highlights the entrenched norms of sovereignty and material stakes that states perceive in maintaining control over their arms exports as well as the absence of human rights from the discussion. Second, I identify the key events in the 1990s that explain the origins of new “responsible” arms export norms, a dramatic shift that once seemed improbable given enduring national material interests and exporter preferences. Finally, I investigate how these changes in international normative expectations map onto broad trends in small and major conventional arms export practice between 1981 and 2010. I find that state practice does not reflect humanitarian policy changes. This casts doubt on explanations that rely on either normative obligation or material incentives to explain states’ policy commitments. States have supported new initiatives in spite of their underlying export preferences, not because of them. Changes in policy can come without changes in practice if states can receive the social reputational benefits of commitment without engaging in costly implementation. By examining the historical continuities and broad shifts in how states collectively engage in arms export policy and practice, the chapter sets the stage for the more in-depth analysis of major exporters’ specific policy choices within this international environment.

ASSESSING GLOBAL ARMS EXPORT TRENDS

This chapter examines four key periods in the twentieth-century global arms trade: (1) the League of Nations and interwar years; (2) the Cold War; (3) the early 1990s; and (4) the road to the ATT. Attempts to create shared arms trade regulations prior to the late 1990s were notorious failures. Yet although the contemporary historical record on arms export policy is well established, the lack of available data on states’ arms export practice (i.e., policy implementation, in this case arms deliveries) has been a roadblock for cross-national analyses until recent decades. Until the 1990s, a norm of secrecy ruled interstate arms deal making, and information was restricted to news reports and publicly released (or leaked) intelligence reports.4 Major conventional weapons data are generally more comprehensive than small arms data, though small arms data have improved greatly in the past decade. MCW are easier to track, invited greater policy attention until the late 1990s, and, if publicly known, could provide greater prestige and deterrent value than SALW. But even if public records may underestimate arms transfers, it is important to examine export practice alongside export policy in order to evaluate explanations for why policies might change and to what effect.

Although public attention to conventional arms in the United States during the late 1970s brought some more information on MCW there, this trend did not spread elsewhere quickly. A 1979 U.S. government report summarized the problem: “Virtually all nations consider arms sale statistics highly sensitive. Most insist that publication of such information would harm their relationships with purchasing countries.… Only the United States publishes country-by-country details of its arms export transactions. In fact, it appears that few nations actually maintain a central repository of detailed information. Many major suppliers could not, even if they were willing, supply the sort of detailed data that the United States makes available” (U.S. Senate 1979:7).5 As a result, a statistical analysis of trends in export practice cannot extend as far back in time as a historical overview of export policy. Fortunately, data have improved as records have been declassified. And although SALW data are rough in the 1980s, they provide useful insights into this period—when the arms trade was not a prominent issue and human rights considerations were not on the table—as a baseline for assessing later changes in policy and practice.

Since the end of the Cold War, growing arms trade transparency and international research institutes’ long-term efforts have vastly improved the quality and availability of arms export data. The UN Register of Conventional Arms went into effect in 1992, replacing secrecy with a norm of transparency in international, regional, and national politics (Laurance, Wagenmakers, and Wulf 2005:233). Suppliers in particular “have come to accept that almost total secrecy surrounding the arms trade is counterproductive” (Anthony 1997:29–30). Although some exporters still have poor records of reporting,6 transparency has otherwise advanced across the board, especially among established democracies. The reporting improvements now sought in the United States and Europe are meant primarily to increase the level of detail about individual export decisions and do not affect the aggregate annual export–import data used here. Most major suppliers contribute regularly to the UN Register, and the level of detail, especially from European suppliers, is increasingly meticulous. Export information tends to be more regularly and widely submitted than import information (Durch 2000; Lebovic 2006), although reporting in general continues to grow. According to the UN Office of Disarmament Affairs (2012), the number of countries submitting reports rose from 95 in 1992 to a high of 126 in 2011, with 173 countries participating at least once by 2011. The Wassenaar Arrangement and the EU also have arms trade transparency provisions, which increase the volume of reporting.

These transparency initiatives began with MCW exports. Research institutes and governments typically overlooked small arms transfers until the mid-1990s, so SALW data collection relies on general and trade-specific news reports, UN Comtrade (customs) data, and other sources, where government reports are not available.7 The absence of attention to small arms has changed as they have become a significant policy issue in their own right. By 1999, twenty-two states had begun to include small arms in their export reports (Haug et al. 2002). In 2003, Wassenaar decided to include small arms on its list of strategic goods used for intergovernmental transparency. The UN also formally expanded the UN Register in 2003 to include voluntary reporting on small arms transfers. In 2004, only 4 percent of reports submitted to the register included information about small arms transfers. By 2010 and 2011, that number had risen to 66 percent (UN Office of Disarmament Affairs 2012). Despite these limitations, the importance of SALW on the international agenda in recent years and their prominent role in human rights violations make it both valuable and necessary to examine them alongside MCW transfers.

In order to map the relationship between trends in arms export policy and practice in this chapter, I build an original arms trade data set covering as thoroughly as possible SALW and MCW transfers from 22 top supplier states (20 of which voted in favor of the ATT in 2013) to 189 potential importer states from 1981 to 2010. This means that the data are dyadic (e.g., exporter state to importer state) and annual.8 A “dyad-year” therefore refers to exporter–importer pairings in a particular year. Thus, the United States (exporter) and Colombia (importer) dyad or pairing includes thirty dyad-years, covering each year from 1981 to 2010 in the data set.

Details about the data set are provided in appendix B, including exporters covered, variable coding, and control-variable selection. No other data set covers cross-national data for both SALW and MCW transfers.9 The UN defines small arms as “those weapons designed for personal use” and light weapons as “those designed for use by several persons serving as a crew” (UN 1997:11). SALW therefore include, for example, revolvers, machine guns, rifles, and ammunition and explosives (UN 1997:11–12).10 SIPRI defines and codes MCW as large weapons with a military purpose in one of nine categories: aircraft, armored vehicles, artillery, sensors, air-defense systems, missiles, ships, engines, or “others” fulfilling certain qualifications (2007:428–29).11 Scholars have linked both SALW and MCW to human rights violations, but the EU Code of Conduct and the ATT are the only multilateral export control initiatives to encompass both.

This chapter uses the Arms Trade Data Set to assess conventional arms transfer practice from the 1980s to the present day12 through (1) basic cross-tabulations with recipient human rights, (2) regression analyses, and (3) moving-windows (or moving-regression) analyses. I use a measure of recipient countries’ human rights provided by the Political Terror Scale, which scores countries’ physical integrity rights annually based on U.S. Department of State (DOS) and Amnesty International reports (Gibney and Dalton 1996). If policy and practice coincide, Cold War patterns should reveal arms exports as a tool of foreign policy and national security that is indifferent to recipients’ human rights records.13 Given the difficulties with acquiring arms trade data before the 1990s, however, readers should be wary about drawing firm conclusions from earlier data. Following the end of the Cold War, arms transfers motivated by economic gain and industry survival became the dominant trend. Supplier states would have been unlikely to limit arms transfers to human rights violators; in fact, such states might present too valuable a market to avoid ruling them out summarily. By the late 1990s, the shift to “responsible” arms transfer policy called exporters’ attention to their import partners’ human rights records. Policy attention also expanded to include small arms on their own and in conjunction with MCW. If states’ practice reflects their policy commitments, human rights should become increasingly important factors in states’ export practice during this current period—especially among ATT supporters. Although states are still faced with economic pressures to export arms, new political pressures simultaneously push them—at least on paper—to become more discerning in their export decision making.

CONVENTIONAL ARMS TRANSFERS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

States have carefully protected their sovereign right to decide their arms trade partners without reference to international obligations or external restrictions. The decades before World War I have been referred to as having “the fewest restraints and regulations on the arms trade in modern history” (Krause and MacDonald 1993:712).14 Yet even in the twentieth century the rare attempts to create multilateral arms trade controls consistently failed. The historic absence of multilateral controls strongly reflects this norm of noninterference. And, except for the United States briefly in the late 1970s, humanitarian arms export controls did not hit the policy agenda until the late 1990s. Arms export decision making has been constrained only by states’ national law and policy, which until recently have excluded human rights considerations.

Prior to contemporary “responsible” arms export initiatives, the conventional arms trade took the international spotlight on just three occasions, each partly in response to domestic outrage within major powers about unrestricted arms transfers. Unlike contemporary efforts, these failed predecessor initiatives did not seek regulations based on humanitarian principles, nor were “affected” states among their champions. Rather, they set out to limit arms transfers to specified “unstable” regions, with great powers seeing an opportunity to manipulate allies’, enemies’, and colonies’ (or even their own) access to arms markets in line with their geopolitical and industrial interests. Time and again, absent any sustained social pressure or real change in international policy expectations, states’ material concerns for sovereignty, national security, and economic interests won out over cooperative restraint with little contest.

POST–WORLD WAR I AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS

Global arms transfer controls first came onto the agenda after World War I under the aegis of the League of Nations. The initial attempt—the St. Germain Convention for the Control of the Trade in Arms and Ammunition—was signed in 1919 as part of the postwar settlement. It was motivated primarily by the European powers’ desires to keep weapons from falling into the hands of “problem actors” in areas of colonial influence, but the public’s “moral criticism of the role of arms traders in fomenting the First World War was also prominent in the backdrop to negotiations” (Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012:1032). The St. Germain Convention was meant to implement Article 23(d) of the League of Nations Covenant, entrusting the league with “the general supervision of the trade in arms and ammunition with the countries in which the control of this traffic is necessary in the common interest.” It required government licensing (already practiced by Great Britain), arms export reporting to the league, and arms sales restrictions to nonsignatories, parts of the Ottoman Empire, and Africa. In 1920, diplomats from France, Italy, Japan, and Great Britain agreed informally to implement the convention’s provisions in Africa and the Middle East (Stone 2000:218).

Objections to the St. Germain Convention, however, quickly grew. Perhaps most important for setting off the dominoes of opposition, the United States refused to bind itself for three key reasons: a ban on sales to nonsignatories could harm its domestic arms industry; it felt that “the zones to which the Convention was to apply were drawn so that the result would have been almost exclusively to protect the interests of the surviving European colonial powers and even to interfere with U.S. policy in Latin America”; and, quite simply, it objected to giving power to the League of Nations (SIPRI 1971:92; see also Stone 2000). Following the United States, other arms-producing states also declined to participate, fearing that their industries would be disadvantaged by unequal trade restrictions. In the end, foreign-policy autonomy and industrial interests trumped export controls with little debate.

The League of Nations abandoned the St. Germain Convention in favor of the weaker Geneva Arms Traffic Convention in 1925. This version was tailored to address U.S. concerns and sought only arms export publicity through the league, allowing states to supervise and sanction their own transfers (SIPRI 1971; Stone 2000). In his opening remarks, negotiation conference president Carton de Wiart emphasized that the new convention’s aim was not to restrict the arms trade. Rather, it was “to obviate the possible threat of illicit and dangerous traffic to compromise the good name of such legitimate trade or should hamper the success of the best efforts to create an atmosphere of peace and good will between nations” (League of Nations 1925:122). Not surprisingly, the focus on illicit trade, rather than on what producing states determined to be their legal trade, was much more palatable to producing states than handing over power to the League of Nations.15 Nevertheless, this initiative also failed. This time, the failure was due mainly to nonproducing states (including smaller European states), which saw licensing and publicity as “intolerable infringements on sovereignty and security” that would put them “at the mercy of producers” (Stone 2000:222, 223). These states derailed the initiative by introducing unacceptably high sovereignty costs for the producing states as well, linking export publicity to production publicity and attempting to impose production restrictions (Stone 2000).

The final attempt to regulate conventional arms production and trade in the interwar years was led by the United States in the League of Nations Disarmament Conference in 1934. The U.S. change of heart was motivated by the Senate Nye Committee’s investigations into the U.S. private munitions industry—dubbed “the merchants of death” in the popular press—and concerns about unregulated arms transfers to Latin America (Anderson 1992; Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012).16 The conference’s proposal was unusual in a number of respects: it included arms for nonmilitary use, such as sporting rifles; it created a permanent supervisory body; and it did not single out some regions for higher restrictions (Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012:1033). Although there were disagreements over specific measures, there was general agreement “that the private manufacture of arms should be subjected to government license and that there should be national responsibility for the manufacture of, and trade in, arms” (Krause and MacDonald 1993:719, emphasis added).

Once again, controlling production by nongovernmental actors was a much lower hurdle than controlling government production or licensing. But by the time the conference adopted the draft articles in 1935, it was already too late. The deteriorating security environment in Europe and Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia turned states’ attention to national rearmament and precluded “any possibility of an international agreement” (Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012:1033; see also Anderson 1992). Thus, although the interwar years left a lasting legacy of governments agreeing to give themselves licensing authority over arms exported from their borders, international controls were elusive, and human rights were not an issue. The fate of the interwar initiatives depended on what quickly became clear was the impossible task of aligning the major powers’ material interests and security priorities—made even more impossible when recipient states gained “meaningful agency” at the negotiating table (Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012:1034). These obstacles have persisted, consistently undermining attempts at restraint throughout the twentieth century—to the extent that such attempts have even been made. That is, until the ATT.

THE COLD WAR AND SUPERPOWER FOREIGN POLICY

Disarmament and the arms trade took a backseat during the formation of the United Nations after World War II. The UN Charter established states’ right to self-defense but has “never been viewed as affecting law on the regulation of weapons” (Anderson 1992:765 n. 82). During the Cold War, arms sales were seen as “foreign policy writ large” (Pierre 1982:3). Transfers were dependent not on importers’ internal characteristics, but rather on their East–West ideological orientation and the maintenance of regional power balances. The United States and the Soviet Union in particular used transfers to gain influence among client states in the developing world and to push their foreign-policy preferences.17 The two superpowers were the supersuppliers, setting the tone for the global arms trade. In general, decision makers regarded conventional arms as a valuable political tool to be distributed strategically and not to be hindered unnecessarily.18 Conflicts were an opportunity to sell, “if only to pre-empt transfers by the other side” (Catrina 1988:333; see also SIPRI 1971).

Controls were not entirely absent in this period, but they directly reflected these strategic concerns, codifying Cold War politics and supporting the bipolar system. The Western allies secretly established the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM) in 1949 as an informal agreement to embargo the exports of weapons and dual-use technologies to the Eastern bloc. Although intrabloc and third-party arms transfers went unregulated, COCOM was intended to ensure that sensitive strategic technologies did not benefit Soviet adversaries. The agreement was thought to be relatively effective, if not always enthusiastically implemented by some participating states.19 Countries that did not follow COCOM rules could be blacklisted by the United States, which used the agreement largely as a tool of economic statecraft to serve its hegemonic interests (L. Martin 1992; Mastanduno 1992).20

In 1950, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France also agreed to a more formal agreement, the Tripartite Declaration, to regulate and coordinate arms sales to the Middle East, “tying arms transfers to promises of non-aggression by the recipient states” (Anderson 1992:766; see also Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012; Pierre 1997). The intention was to enable Middle Eastern states to resist Soviet aggression, to maintain a balance between Israel and the Arab states, and to serve as a forerunner to a Middle East security network that would improve the West’s strategic position (Slonin 1987). In reality, the Tripartite Declaration served as a “forum for discussion … rather than as an agreement that imposed mandatory obligations on the parties” (Bromley, Cooper, and Holtom 2012:1034; see also Slonin 1987). Indeed, France violated it from the start with secret arms sales to Israel made with the blessing of the United States (Rubenberg 1989). However, later public increases in French arms sales to Israel sowed discord among the declaration’s members, and Soviet–Czechoslovakian arms sales to Egypt in 1955 and the Suez Crisis in 1956 caused its collapse. Ultimately, the Tripartite Declaration was unable to withstand Cold War politics and the overriding pressure on both sides to use arms to influence global affairs. Even within a small group of Western allies with shared security concerns, export controls remained elusive.

It was not until the late 1970s that arms export regulations returned to the global agenda,21 thanks to U.S. public outcry in the wake of weariness over involvement in Vietnam and the lead-up to the 1976 U.S. presidential elections. In a campaign speech, Jimmy Carter argued that the United States could not be both “the world’s leading champion of peace and the world’s leading supplier of the weapons of war” (Carter 1976). For the first time, policy makers linked arms transfers to concerns for recipient human rights.22 Leslie Gelb criticized arms export practice under Nixon and Ford, stating that “the character of the regime was overlooked in view of the overriding importance of stopping communism” (1976–1977:14). Michael Stohl, David Carleton, and Steven Johnson’s (1984) findings that states with higher levels of human rights violations received more economic and military assistance under Nixon and Ford support Gelb’s criticisms. Once in office, the Carter administration sought to promote U.S. and global export restraint through unilateral policy changes and multilateral negotiations. Both approaches, however, became casualties of Cold War politics.

First, Presidential Directive 13 (PD-13) set unilateral guidelines to limit the spread of U.S. weapons and indicated “that human rights violations would be an important consideration in the [arms sales] decision-making process” (Brzoska and Ohlson 1987:57). The directive was a radical change in policy for any major arms supplier. It introduced human rights into national-level arms export policy and imposed unilateral restraint to set an example for other suppliers. In practice, however, it was considered a failure from the start.23 The policy itself “did not set out clear priorities and contained significant inconsistencies and contradictions,” which allowed the administration flexibility in application and gave opponents to it in the U.S. bureaucracy and defense industry the means to slow its implementation (Spear 1995:177).

As a result, human rights considerations—when applied at all—were applied only in countries deemed not vital to U.S. national-security interests, with arms exports commonly used as a tool of foreign policy elsewhere (Brzoska and Ohlson 1987; Pierre 1982; Spear 1995). This practice of case-by-case flexibility to support “indispensable” nations, criticized Stanley Hoffmann at the time, made “[the Carter] administration look not so different at all from that of the previous one” (1977–1978:19–20). For the most part, quantitative evidence confirms this disconnect between policy and practice. Human rights were not a significant determinant of levels of U.S. military aid during the Carter administration (Stohl, Carleton, and Johnson 1984:222; see also Apodaca and Stohl 1999; Forsythe 1987).24 Moreover, the same economic and security concerns that overrode human rights considerations in U.S. arms export practice during the Carter years ensured that human rights as an arms trade policy issue did not diffuse to other countries and would not even return to U.S. national arms export policy until 1995.

Second, President Carter sought to bring multilateral export restraints to the international agenda. Although not incorporating human rights considerations, between 1977 and 1978 Carter sought to negotiate multilateral transfer limitations to complement U.S. unilateral restraints articulated in PD-13. The Conventional Arms Transfer (CAT) talks were intended to be the first attempt to negotiate global restraints since the interwar years. However, when the United States approached European producer states about participating, they declined the invitation, not wanting to commit to trade limitations until it was clear that the Soviet Union would do so first (Spear 1995). As a result, the talks focused entirely on engaging the Soviet Union and fell apart before an agreement was reached (Pierre 1982:286). Whereas League of Nations talks at least had widespread major-power participation, the CAT talks could not even get West European producers to the table.

The collapse of the talks was due to disagreements both within the Carter administration and between U.S. and Soviet policies over limits on transfers to “critical regions” (Catrina 1988:130–31; Durch 2000; Hartung 1993; Pierre 1982; Wentz 1987–1988). U.S. bureaucrats disagreed about the role of arms transfers in foreign policy and whether the United States should be discussing arms transfers to sensitive regions at all, a disagreement that undermined the U.S. ability to negotiate as talks progressed (Pierre 1982; Spear 1995). Moreover, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were concerned that the United States “would be tied down in extended global negotiations with the Soviets whilst they and the European suppliers took advantage of PD-13’s unilateral restraints” (Spear 1995:119). For their part, the Soviets were “incredulous and angry at the American unwillingness to hear what they had to say about the regions of concern to them” (Pierre 1982:288). The United States, however, felt that including East Asia and the Middle East, as the Soviets wanted, would be unacceptable. It privately informed the Soviet delegation that it would walk out of the fourth round of talks in December 1978 if the Soviet Union followed through on its proposal (Spear 1995). As a result, the December meeting kept any specific regions off the table and never got a chance to put them back on as détente waned, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, and the United States prioritized relations with China over discussions about arms transfer restrictions to East Asia. Not surprisingly, politics had once again gotten in the way of arms trade cooperation, with the superpowers unwilling to limit arms sales to strategic regions.

With the inauguration of Ronald Reagan in 1981, the arms trade policies that the United States had attempted to promote under the Carter administration came to a clear end. The CAT talks had already died out, and Reagan immediately rejected PD-13 in favor of an explicit return to “the use of arms sales to counter the Soviet challenge” (Wentz 1987–1988:352). In general, the Reagan administration had little interest in limiting arms exports (Pierre 1982:63). Human rights, too, were once again absent from the discussion. The administration “refused to consider reducing security assistance or sales because of human rights considerations,” given the clear and present danger from the Soviet sphere (Forsythe 1987:385). Consistent with Reagan’s stated policy priorities emphasizing national security and deemphasizing human rights, Clair Apodaca and Michael Stohl (1999) find no statistically significant link between human rights and U.S. military aid allocation throughout the two Reagan administrations.25

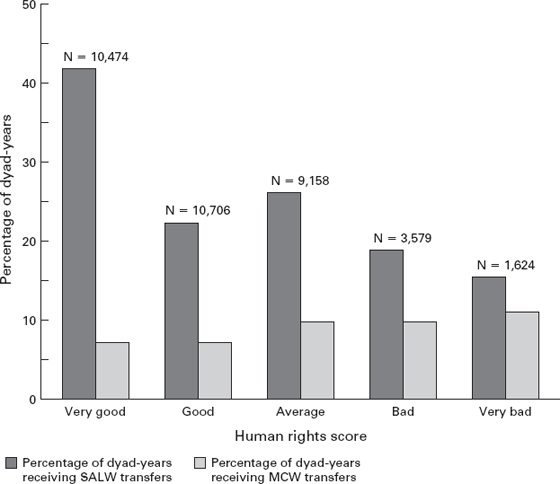

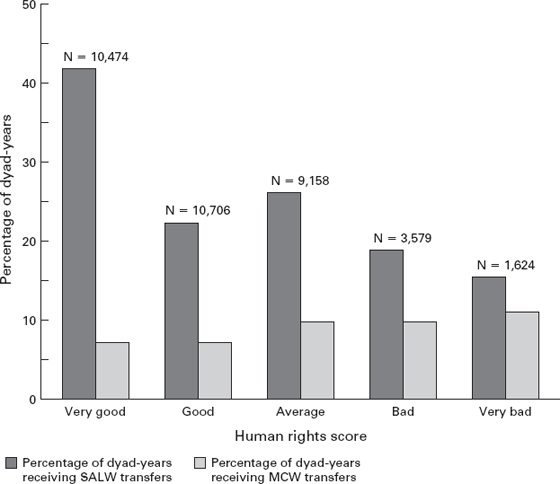

The link between conventional arms transfers and human rights globally is more difficult to assess in this period. When it comes to major conventional arms, for which data availability is better, the Arms Trade Data Set reveals a picture that does not single out good human rights for reward or poor human rights for punishment during the Cold War. Figure 3.1 illustrates the results from simple cross-tabulations, which find that about 11 percent of dyad-years whose importers had records of “very bad” human rights received MCW transfers (in contrast, 89 percent did not receive MCW transfers). Clearly, only a minority of the worst human rights performers received MCW, but that portion is relatively high compared to the 7 percent of dyad-years whose importers had the best human rights records and received MCW transfers (93 percent did not). Regression analyses also reveal a strong positive relationship between poor human rights and MCW transfers (see tables C.1 and C.2 in appendix C).26 In other words, as might be expected, countries with poor human rights were more likely on average to receive MCW than countries with the best human rights during the 1980s.

FIGURE 3.1. HUMAN RIGHTS AND ARMS TRANSFERS, 1981–1991.

Note: Each bar shows the percentage of dyad-years within that category of human rights score for which there is a record of a SALW or MCW transfer (as opposed to the percentage of dyad-years within that score for which there is no record of a SALW or MCW transfer). I use PTS-DOS data for cross-tabulations because of their broader geographic coverage.

Small arms transfer data are scarce in this period, complicating the ability to draw confident conclusions about export trends. Just less than 16 percent of dyad-years whose importers had “very bad” human rights records received small arms transfers during the 1980s (figure 3.1). Although likely an underestimate, this percentage is somewhat higher than the figure for MCW but far lower than the percentage receiving SALW for any of the other human rights scores. In contrast, almost 42 percent of dyad-years whose importers had “very good” human rights records received small arms. Similarly, results from the regression analyses (tables C.3 and C.4 in appendix C) show a significantly negative relationship between poor human rights and SALW transfers—that is, poor human rights performers were less likely to get SALW—during the last decade of the Cold War.

Rather than any concerted effort by governments to wield small arms transfers as a tool to punish human rights violations, however, these regression results seem likely to be an artifact of poor SALW reporting. Countries may have received small arms even though there is no record of the transfer because attention to, tracking, and reporting of small arms were almost nonexistent during the Cold War. Alternative explanations for this finding are less compelling. Arms export controls were not on the table, human rights had been set aside after a brief flurry of interest limited to the United States in the 1970s, and small arms had yet to be recognized at all on the international agenda. Instead, Cold War politics and security drove arms trade policy, new producers were entering the market, and European producers worked at export promotion (at least with allies and friends). This focus on export promotion and the economic—rather than strategic—imperatives behind the arms trade would expand with the end of the Cold War and the contraction of the arms market that was to come.

THE END OF THE COLD WAR AND ECONOMIC IMPERATIVES

The end of the Cold War meant significant changes for the international arms trade, including changes for supplier–recipient relationships, justifications for arms transfers, and efforts to control those exports. Even so, the end of the Cold War did not mark a clear turning point in favor of arms export control, despite some initial optimistic expectations.27 On the one hand, the end of the bipolar global system reduced states’ need to use arms to buy allies and influence the balance of power, in theory opening up space for multilateral agreement. On the other hand, the disappearance of shared threats to the international system meant drastically reduced defense budgets and demand for arms. Producers struggled to remain afloat and sought to export to whatever markets were available, making multilateral controls seem impractical and even damaging for economic and military security if production lines could not be sustained.

Even during the Cold War, secondary suppliers—chiefly in Europe, although production capacity spread in the 1980s—were left “to sell arms primarily for commercial purposes” (Harkavy 1994:20; see also Catrina 1988 and Durch 2000).28 Although claims of the economic benefits of arms transfers have been debated,29 smaller domestic markets for defense goods led at least to the perception—if not also the reality—that exports were necessary to maintain a viable domestic defense industry (Brzoska and Ohlson 1987; Catrina 1988; Durch 2000). For the top-tier producers as well as for small and medium suppliers, the end of the Cold War intensified and broadened states’ economic motivations to promote arms exports while simultaneously reducing the political utility of such exports.30 Arms availability and production capacity were more widespread than ever before. Secondhand goods were in high supply, and companies overproduced new arms in their struggle to adjust to the new security environment. Demand shrank in both domestic and international defense markets. Sales declined globally, but exports were considered even more necessary for defense industry survival.31 The global arms market presented an industry in decline, in terms of both production orders and the value of goods exported.32

It was in this economically strained arms market that the final failed attempt to create multilateral arms export controls took place, motivated by Gulf War revelations of destabilizing covert arms sales by Western suppliers to Iraq during the 1980s. In March 1991, Canada proposed a world summit with the goal of establishing shared controls by 1995 to deal with the potential risks of unrestrained arms transfers (Phythian 2000b). In May, a more skeptical United States announced an initiative to control arms sales only to the Middle East, calling on major suppliers to “develop guidelines for restraints on destabilizing transfers to that region” (Pierre 1997:376). France responded with a proposal to phase down quantities of arms in each region to the lowest levels possible. The United Kingdom expressed interest in a discussion about controls as well as an arms sales register, and the Soviet Union suggested a UN Security Council Permanent-5 (P5, China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States) meeting on the issue. At the first meeting in July 1991, the P5 agreed to talks with the goal of setting guidelines for conventional arms transfers.33 Additional rounds of talks took place in September 1991 and May 1992, with the P5 drafting guidelines to consider recipients’ “legitimate” defense needs as well as whether a transfer would increase regional tensions or exacerbate existing conflicts (Davis 2002; Pierre 1997).

The window of opportunity for reaching an agreement closed soon thereafter, however. The draft guidelines from the September 1991 meeting “simply restated principles on which there was already broad conceptual agreement,” and by May 1992 disagreements began to surface (Pierre 1997:378). In echoes of discussions past, questions about what should constitute “destabilizing” weapons sales, whether and how to provide advance notice of sales, and whether the talks were meant to address only the Middle East or to extend globally proved to be fundamental differences. The formal collapse of the talks came when China decided to boycott in response to U.S. and French arms sales to Taiwan in September 1992 (Pierre 1997:379). Indeed, although all of the P5 in theory supported export restrictions on some scale, export promotion—and, in some cases still, broader domestic and foreign-policy interests—dominated the post–Cold War era. Even a group as small as the P5 was unable to reach agreement, with competing material interests among the major powers trumping temporary political incentives to cooperate.34

The only concrete outcome from this post–Cold War momentum was the UN Register of Conventional Arms, also a response to Gulf War arms sale revelations. Considered a confidence-building measure at its inception, the register was meant to provide arms trade transparency as a means to prevent “the excessive and destabilizing accumulation” of major conventional weapons.35 In addition, COCOM’s replacement—the 1996 Wassenaar Arrangement—was created solely as a transparency regime without the political support to undertake export controls. Later, when paired with new commitments to humanitarian export policies, these transparency agreements would have some domestic consequences for arms export decision making, as I argue in chapter 5. In the meantime, however, transparency provided information about exports without any expectations or obligations about how those exports should be conducted.

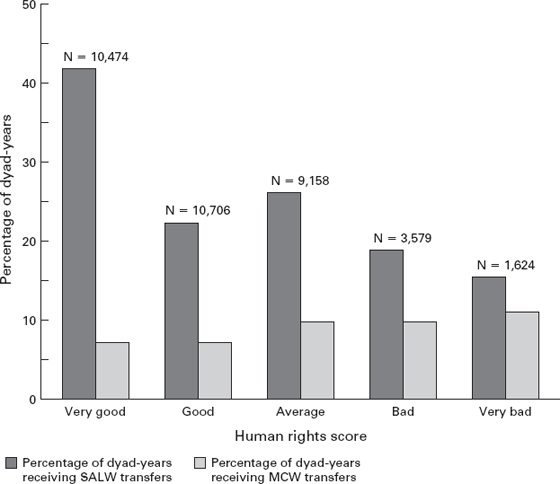

During this period, the percentage of dyad-years in which MCW exports to any importers took place was down compared to the percentage during the Cold War, regardless of human rights performance (figure 3.2). In each category of human rights score, the percentage receiving MCW was well less than 10 percent, with the highest for recipients with “bad” human rights, at just more than 8 percent receiving MCW (and 92 percent not receiving MCW). This is likely due to a downturn in the market for large expensive weapons after the Cold War. However, the percentage of exporters sending small arms to poor human rights performers is higher in this period, with almost 30 percent of dyad-years with “bad” recipient human rights and just more than 19 dyad-years with “very bad” recipient human rights receiving SALW. Even if the export of small arms is underreported, these figures suggest a trend toward supply not restraint.

FIGURE 3.2. HUMAN RIGHTS AND ARMS TRANSFERS, 1992–1997.

The regression results tell a more complex story (tables C.1–C.4 in appendix C). To the extent that human rights were a significant factor for states’ arms export practice at all during the early post–Cold War years, the trend was to provide more arms—not less—to poor human rights performers. For both MCW and SALW, “bad” human rights are significantly positive. In other words, recipients with “bad” human rights records were more likely to receive SALW and more MCW than the best human rights performers. “Very bad” human rights are insignificant for both types of weapons transfers. This means that supplier states did not seem to reward or punish the worst human rights performance; performance simply did not factor significantly into their export decision making. Thus, for both MCW and SALW transfers, it is important to note that state practice during these years did not foreshadow the policy changes that were to begin later in the decade. With declining demand and a tough buyer’s market, many supplier states did not want further restrictions on their ability to export arms. Material interests ultimately continued to drive arms export policy and practice, with the major suppliers dominating discussions and fending off interference from external rules and expectations. The conditions for normative change had not quite arrived.

NORMATIVE CHANGE: PUTTING “RESPONSIBLE” ARMS EXPORT CONTROLS ON THE AGENDA

Yet amid the market competition of the early 1990s, the conditions for change in the international normative environment for the conventional arms trade began to appear. By the late 1990s, denying conventional arms transfers to human rights violators and conflict zones reemerged as a matter of state responsibility. By the end of the decade, this new phase was clear: the EU agreed to its politically binding Code of Conduct on Arms Exports in 1998, and in 1999 the U.S. Congress passed legislation requiring the president to start work on an international arms sales code of conduct that would include criteria to limit sales to human rights violators. This phase has not been short-lived, either. Although the 2001 UNPOA was a politically binding national-level measure to curb illicit small arms sales, its negotiation process galvanized supportive states and NGOs to pursue legally binding “responsible” export controls.36 This momentum culminated in the Arms Trade Treaty, completing what diplomats in previous eras were unable to do: the establishment of legally binding global humanitarian standards to regulate the international trade in small and major conventional arms.37 The ATT was approved by a wide margin of 154–3 at the UN General Assembly in April 2013. Representatives from sixty-seven states lined up at UN headquarters to sign when it opened for signature on June 3, 2013.38 It goes into effect on December 2014.

By the end of the 1990s, human rights, governance, development, and conflict were no longer either peripheral concerns or reasons to justify weapons transfers but rather fundamental grounds to exercise restraint. This shift was in part related to a broader post–Cold War trend that put human rights and humanitarian issues in the global spotlight. Whether it was an outcome of a genuinely new movement by states to infuse ethics into their foreign policies can be debated (Dunne and Wheeler 2001; K. Smith 2001; Wheeler and Dunne 1998).39 However, the increased prominence of these issues is undeniable, as is the newfound attention to norms of international behavior to accompany them. In the pursuit of these political agendas, direct and indirect connections to the arms trade have been made, linking an issue once the sole domain of hard security to a broader economic, social, and human security problematic.

Instead of categorizing all arms exports as good, bad, or necessary, as past rhetoric and advocacy had, the international community adopted a more nuanced approach. States began to identify a practical and symbolic foreign-policy utility in the selective denial of arms based on a recipient’s internal policies and practices. In contrast to the realpolitik of past arms trade rationale, the trend since the late 1990s has introduced “an other-directed or morally based philosophy of restraint [emphasizing] the character and behavior of recipient governments toward their own people and within their security complex” (Durch 2000:152). Supplier states found themselves faced with both continued economic pressures to sell arms and new political pressures to adopt more discerning policies as a reflection on themselves as “responsible” members of the international community. Instead of seeking to reduce arms exports across the board, new policies laid out criteria obliging states to regulate their arms exports to certain types of arms importers, including states with severe human rights violations.

The normative shift that brought about these policy initiatives was not the result of a single shock to the system or critical juncture. Four key developments in the 1990s pushed the need for arms trade restraints into the spotlight and generated a new normative environment for the conventional arms trade. The emergence of “responsible” arms transfers benefited from states’ acceptance of other international norms related to human rights and humanitarianism, but it was the confluence of these developments that drew international attention to these issues in the context of export controls for conventional arms and, for the first time, small arms specifically.40 The accompanying shift in policy expectations motivated many exporting states to make dramatic changes regarding their own arms export policies. As I show in chapter 4, major suppliers’ concern for reputation in the context of this changed international normative environment pushed their widespread support for “responsible” conventional arms export policies.

The first development that heightened the awareness of the need for arms trade restraints was that the 1991 Gulf War put many Coalition soldiers face to face with weapons sold to Iraq by their own countries during the 1980s. This blowback experience taught major suppliers a cautionary lesson for future arms exports in the interest of their own military security. The primary result was the creation of the UN Register of Conventional Arms and the development of arms trade transparency norms in the hope of providing an early-warning mechanism of excessive arms buildups (Goldring 1994–1995; Laurance, Wagenmakers, and Wulf 2005). The Gulf War experience also triggered numerous domestic scandals for secretive sales of arms and defense technology to Iraq, which had revealed states’ poor control over their arms trade and the destabilizing consequences of exporting arms to a volatile authoritarian regime. The Arms to Iraq scandal in the United Kingdom in particular spurred early policy change and critical norm leadership by a major arms producer (Erickson 2013a). Thus, although the P5 talks failed after the war, most supplier states did improve transparency in its political aftermath and were impressed by the risks and costs of an unregulated global arms market.

Second, civil and ethnic conflicts following the Cold War—especially high-profile conflicts in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia—highlighted problems associated with small arms proliferation and the need for multilateral export controls to prevent arms buildup in conflict zones and unstable regions.41 Policy makers relied increasingly on arms embargoes to address this need, sparking a vigorous debate on the utility and effectiveness of arms embargoes.42 Where arms supplies helped to fuel genocide, some states also faced backlash at home for their export decisions (see chapter 5 on domestic backlash). These conflicts as well as the peacekeeping and reconstruction efforts to follow pushed small arms to the forefront of the international agenda (Karp 1994; Klare 1994–1995; Sislin and Pearson 2001). Rather than major conventional weapons, the main tools of these internal conflicts were SALW, sold or given away without regulation as political currency during the Cold War. Research and reports from NGOs and academics spread, pointing not only to small arms’ contribution to exacerbating conflict and insecurity, but also to their role in undermining development, human rights, and governance.43

States adversely affected by small arms proliferation also began to push the issue within the UN and regional organizations. Colombia introduced UN resolutions in 1988 and 1991, prompting a string of research missions, reports, recommendations, and guidelines.44 The UN established the Group of Governmental Experts on Small Arms in late 1995. The group’s 1997 report “worked as a cornerstone in profiling the array of problems associated with small-arms availability” and prompted the initial decision to convene an international conference on small arms trafficking (D. Garcia 2006:46). A growing coalition of like-minded states was forming, extending beyond affected states to include Canada, Norway, and Japan. Once ignored, small arms were poised to become the focal point of the international arms control agenda.

Third, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and the 1997 Ottawa Mine Ban Treaty broadened the scope of the international security dialogue to include human security and introduced the possibility of humanitarian arms control (Eavis 1999; D. Garcia 2006; Lumpe 1999a). The widespread acceptance of the Ottawa Treaty legitimized the pursuit of arms control based on its relationship to societal security, individual well-being, and humanitarian obligations. Although a ban on anti-personnel landmines (APL) is not wrapped up in the same degree of political complexity as controlling broad categories of conventional weapons,45 its momentum helped galvanize more comprehensive conventional arms control efforts, including extensive support for small arms control and the ATT process at the UN (Human Rights Watch [HRW] 1999; Lumpe 1999a; McRae 2001; Renner 1997).

The marriage between traditional security and human security begun by the landmine campaign has given new, multifaceted dimensions to arms control and has created a growing consensus on “good” conventional arms policy linked to humanitarian values. This normative shift was especially critical in convincing nonaffected states to endorse humanitarian or “responsible” export policies. Based on their experience with the Ottawa Treaty, as I show in chapter 4, states realized the reputational benefits of being seen on the “right side” of multilateral arms control, a perspective that has carried over into various regional and international initiatives on small arms and conventional arms more broadly.

Fourth and finally, related to the ICBL’s success, the growing role of NGO advocacy in international affairs contributed to the emergence of arms transfer controls on the political agenda. NGO research provided a knowledge base to back up political claims behind the need to control the arms trade (D. Garcia 2006). NGOs have also pushed and partnered with states to advance export controls in national and international politics. By campaigning for and supporting governments’ domestic and foreign-policy efforts to pursue new arms trade regulations, they have played a key (although not necessarily lead) role in developing and promoting the arms export control agenda (D. Garcia 2006). In addition, they have increasingly been able to use improved arms trade transparency to better hold states accountable to their policy commitments, as I discuss in chapter 5. These commitments—to the values of human rights, peace, and stability as well as more narrowly to the conduct of the arms trade—have become clearer as national legislation and multilateral agreements have emerged since 1998. In turn, the arms trade has become a reflection of states’ values, their associations with other states, and how well they respect and promote the norms of the international community (Misol 2004).

The link between arms transfers and a “moral” or “responsible” foreign policy is not a new one, of course. The 1976 U.S. presidential campaign made the most explicit connection, with Carter charging that unrestricted arms transfers were contrary to U.S. principles and morally bankrupt (Pierre 1982:45). Yet Carter failed to substantively affect the practices of even his own administration, and his effort remained a unilateral initiative, criticized as inconsistent and divorced from reality (Hoffmann 1977–1978; Kearns 1980). In contrast, the current trend has not been a short-lived political debate in one country, but rather an ongoing worldwide discussion with both domestic and international dimensions and concrete policy results. Within a single decade, the normative environment for the global arms trade has changed noticeably, from noninterference on behalf of national material interests to “responsibility” and humanitarianism. States have broken with the past to sign on to multilateral standards and incorporated new norms into national policy. They have done so despite the considerable costs of adopting new policies that seem to promise no material gains, limits to their foreign-policy flexibility, and market restrictions amid domestic budget crises and financial downturn. But is this break with the past a norm success story? The answer is not yet clear.

MAPPING COMMITMENT AND COMPLIANCE: GLOBAL TRENDS IN ARMS EXPORT PRACTICE

The forces behind this macrolevel normative shift are clear, but why have major arms supplier states gone along with it and agreed to bear its costs? Scholars often expect states to sign on to multilateral initiatives in anticipation of material benefits, out of a sense of normative obligation, or simply because of the low cost of codifying existing practice.46 As a result, all three of these explanations expect states’ practice to mirror their commitments. If multilateral commitments are a means to achieve material gains or reflect states’ acceptance of new norms, then ATT supporters should engage in weak implementation at least. If multilateral agreements codify existing practice, then ATT supporters’ export practice should foreshadow changes in policy. A failure to find a correlation between ATT supporters’ policy and their practice would deal a significant blow to each of these three arguments. In contrast, the social reputation argument, in which states make international commitments for their social benefits, does not require policy and practice to go hand in hand. States may adapt their public policies to the social expectations of a new normative environment without internalizing those norms or implementing them in practice. Social reputational motivations may be especially clear-cut in cases like this one: where the implementation of costly commitments is often unmonitored and unlikely to be punished if broken, allowing states to garner social gain without paying material costs.

As a first cut at untangling these potential explanations, it is therefore useful to examine arms export practice alongside these new policy initiatives to know whether and when ATT supporters began to decrease or eliminate arms transfers to human rights violators, if at all. Yet although research institutes have for decades tracked the annual value and quantity of major conventional arms transfers47 and more recently of small arms transfers,48 little is known about states’ patterns of arms export practice in light of new “responsible” arms export policies.49 Major arms exporters first articulated humanitarian arms trade norms only after 1997. As I discussed earlier, major suppliers faced a downturn in the 1990s arms market, leading to competition for buyers and an aversion to multilateral regulations. Arms export practice in the 1990s at best seemed disinterested in recipients’ human rights (tables C.1–C.4 in appendix C). These findings cast initial doubt on the viability of expectations that practice will precede changes in policy to ensure low-cost commitment by participating states. Determining whether states anticipate material gains to offset the costs of adopting “responsible” export controls, however, will require an examination of more recent quantitative data as well as qualitative evidence provided in the case studies.

Normative theories are not surprised by states’ policy commitment but also expect that states’ practice will reflect their commitment out of a normative obligation to it. The existing literature, however, is mixed when it comes to finding a role for human rights in the contemporary arms trade. Whereas Shannon Lindsey Blanton (2000, 2005) argues that U.S. foreign military sales (the commercial subset of U.S. arms transfers) came to reflect human rights concerns during the 1990s,50 others (e.g., Erickson forthcoming) find no such significant connection between human rights and U.S. arms transfers over time. More broadly, Lerna Yanik (2006) observes that between 1999 and 2003 top exporters continued to transfer MCW to poor human rights performers despite the exporters’ emerging commitments to “responsible” export policy initiatives. One study (Erickson 2013b) finds that recipients with bad human rights tended to receive more MCW from top EU arms supplier states in the lead-up to the EU’s adoption of humanitarian criteria in its Code of Conduct in 1998 and no significant relationship after 1998. However, this analysis is limited in that it does not include small arms and ends in 2004, making it unhelpful in considering the effects of global commitments to the ATT in the years to come.

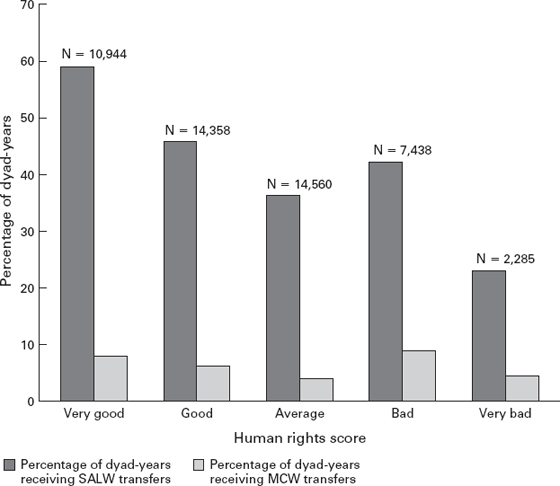

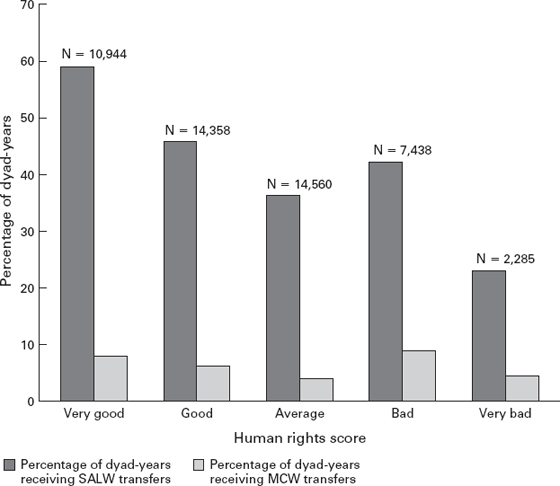

Figure 3.3 shows cross-tabulation results covering 1998 to 2010 for all twenty-two exporters in the Arms Trade Data Set. Clearly, poor human rights did not seem to slow the frequency of arms sales in this period any more than they had in the past. For MCW transfers, just more than 9 percent of dyad-years in which importers had “bad” human rights received MCW (about 91 percent of dyad-years with “bad” human rights did not receive MCW), and approximately 5 percent of dyads in which importers had “very bad” human rights received MCW (about 95 percent did not). On their own, these percentages may seem low, but they are not markedly different from the 1990s (figure 3.2), when approximately 8 percent and 5 percent of dyad-years received MCW in each human rights category respectively. In the case of SALW, poor human rights performers appear to receive arms with slightly greater frequency after 1997. Approximately 42 percent of dyad-years in which the importers had “bad” human rights received SALW, compared to 30 percent in the 1990s. Of dyad-years with “very bad” human rights, about 23 percent received SALW, just up from 19 percent in the 1990s.

Yet regression analyses covering 1998–2010 show poor human rights to be either positively associated with receiving more MCW or simply insignificant (tables C.1, C.2). Importantly, there is no evidence to suggest that ATT supporters have come to collectively limit their supply of MCW to poor human rights performers in this period or before it (table C.2). The results for SALW transfers, however, do show critical changes in export practice (tables C.3, C.4). For the full set of supplier states as well as for the subset of ATT supporters, both “bad” and “very bad” human rights produce significantly negative coefficients. This suggests that the worst human rights performers were in fact less likely to receive SALW in the “responsible” arms trade era. Where there is preliminary evidence for change in the direction of new norms and policies, it has been with small arms, regarding which international discussions since the late 1990s have been the most intense. Of course, these findings cannot indicate causation, which I explore in the case studies in chapters 4 and 5. However, this initial look at the data across SALW and MCW transfers presents mixed results about states’ arms export practice that calls for a more nuanced analysis.

FIGURE 3.3. HUMAN RIGHTS AND ARMS TRANSFERS, 1998–2010.

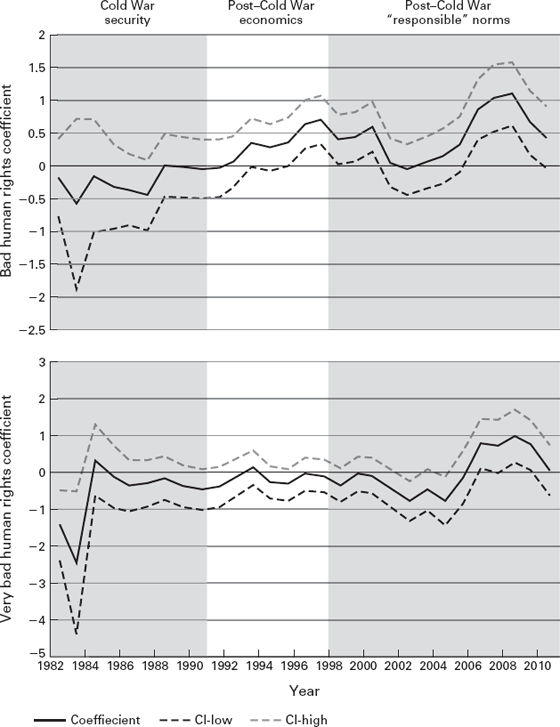

By aggregating the years for important periods in arms trade policy, these regression results offer new insights into states’ arms trade practice. Even so, this approach is less adept at estimating more carefully whether new policy initiatives might flow from changes in practice or vice versa. Timing also matters for assessing alternative explanations, which anticipate policy change either to precede or to follow changes in practice. For a more fine-grained approach, I therefore apply moving-windows (or moving-regression) analyses to the same regression models to explore ATT supporter states’ arms export practice over time (for this type of analysis, see Beck 1983 and Swanson 1998).51 This technique maps temporal trends in arms transfer practice in relation to recipients’ human rights records during the three periods of arms export policy outlined in this chapter: Cold War security politics, the post–Cold War economic imperative, and new “responsible” or humanitarian arms trade initiatives. As a result, this approach can better recognize and pinpoint any changes in behavior, which in reality would probably not make abrupt alterations from year to year. Rather, as moving-windows analyses are equipped to show, practice would likely evolve gradually (Swanson 1998), either in anticipation of new policy commitments or as standards become more widespread and commonly accepted by states and actors within them. Certainly, the ATT may need to be around a long time for norms to take hold and change state practice, but if this turns out to be the case, then contemporary state commitment to the ATT cannot be satisfactorily explained by normative perspectives.

Figure 3.4 shows the moving-window coefficients and their 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) for the relationship between recipients’ “bad” and “very bad” human rights and ATT supporters’ MCW exports. The general rule is that the moving-windows coefficients are significant for the years at which their upper and lower 95 percent CI fall fully above (positive) or below (negative) the zero line. This means that in the case of MCW transfers “bad” human rights are significantly positive for all years except 1984. Countries with bad human rights are consistently more likely to receive MCW transfers from ATT supporter states than countries with the best human rights records. Outside of the Cold War years, however, “very bad” human rights are consistently insignificant from the battle for arms markets in the 1990s to more recent “responsible” export controls. This suggests that ATT supporters have been at best indifferent about their MCW import partners’ human rights records, with no discernable changes in practice before or after the emergence of “responsible” export norms and the ATT. In fact, discussions about “responsible” export criteria with regard to MCW have been much slower to take hold in international fora. Although the 1998 EU Code of Conduct focused on major conventional weapons, UN initiatives only formally expanded from small arms to include MCW in 2006. As a result, MCW exports may be more resistant to the influence of new standards, with security and economic concerns—rather than new norms—continuing to drive who gets MCW.

Although the aggregate regression results for SALW suggest that major exporters were beginning to limit their supplies of small arms to the worst human rights performers after 1997, these results do not carry over into the more time-sensitive moving-windows results. Instead, the SALW results (figure 3.5) for the most part show a picture similar to those for MCW. Leaving aside the 1980s, for which incomplete data make speculation about the results difficult at best, we can conclude that ATT supporters have seemed either to reward or simply to ignore recipients’ poor human rights. In the case of “bad” human rights, the results are significantly positive from 1996 to 2000. Recipients with “bad” human rights were more likely to receive SALW, even as the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Small Arms was being held and plans were being made for the UN small arms meeting in 2001. These recipients were also more likely to receive SALW from 2006 to 2009, the years in which the UN began its formal process to create the ATT. Rather than practice preceding—or even following—policy, these results show a clear disconnect between the two in the case of SALW and bad human rights.

FIGURE 3.4. HUMAN RIGHTS AND MCW TRANSFERS BY ATT SUPPORTERS.

FIGURE 3.5. HUMAN RIGHTS AND SALW TRANSFERS BY ATT SUPPORTERS.

The results for SALW transfers and “very bad” human rights show a similar pattern. Although there is evidence of a brief significantly negative relationship in 2002 and 2004, with recipients having “very bad” human rights less likely to receive SALW—perhaps in response to the global spotlight on small arms following the first UN small arms meeting in 2001—this behavior was not sustained. Indeed, to conclude that new norms were producing significant lasting effects on reducing SALW transfers to recipients with “very bad” human rights would be premature. As with “bad” human rights, between 2006 and 2009, the results for the “very bad” recipients are significantly positive, meaning that the worst human rights performers were more likely to become recipients of SALW.52 Rather than closing as states have pledged their commitment to an ATT and its principles, the policy–practice gap appears to have widened in recent years.53

Yet although results showing consistent reward for poor human rights over all or most years would not be surprising, behavioral change in this direction during this period is difficult to explain, especially when no similar change is evident for MCW transfers. Falling after September 11, 2001, and before the start of the global financial crisis in 2008 and the Arab Spring in 2011, this change coincides with no significant international event or collection of events that might encourage more liberal SALW export practice from ATT supporter states. Nevertheless, it is possible that this finding reveals a collective adaptation by major exporters to the continued war on terror and its new security environment, led by export heavyweight the United States. In particular, U.S. decisions to lift arms embargoes and export arms in order to win friends in the war on terror and to address balance-of-power concerns in the Middle East have been identified as a return to a Cold War–like arms trade.54 In response, other exporters may have seen a need to keep up in a competitive arms market as well as an opportunity to liberalize their practices despite new policy initiatives.55 Moreover, SALW transfers to Iraq, Afghanistan, and friendly states are more likely to be accepted as counterterrorism and security necessities by domestic publics that might otherwise be skeptical of transfers to poor human rights performers.

What is clear is that there is a disconnect between global policy discussions, rules, and norms and how states actually decide to conduct their arms trade in practice. The ATT, EU Code of Conduct, and other initiatives neither codify existing practice nor reflect a closely held commitment to new norms. Thus, although new policies represent a significant normative shift in the international system, that shift is incomplete and practice has remained for the most part consistent from the last decade of the Cold War to the present day. This consistency is not necessarily surprising. Norm internalization can take decades to complete and is never guaranteed. Even so, the discrepancy between policy and practice provides initial evidence against material or normative explanations for states’ multilateral commitments in the case of the arms trade. It also raises important questions about how to ensure that states’ practice follows their policy.

By outlining major historical trends in arms transfer policy and practice, this chapter seeks to make three major contributions. First, it highlights persistent political difficulties in creating conventional arms transfer controls. On the rare occasion that the arms trade has found a spot on the international agenda, sovereignty, security, and economic concerns have consistently undermined attempts impose regulations. Until the late 1990s, multilateral arms control discussions instead served as a means for major exporters to protect their foreign-policy interests and arms markets, leaving human rights out of the conversation. The historical hurdles to reach an arms trade treaty were high, and the ATT’s overwhelming success in the UN General Assembly in 2013 could not have been predicted fifteen years earlier.

Second, the chapter outlines four key factors in the 1990s that explain the dramatic change in the international normative environment for the arms trade: Arms to Iraq scandals following the 1991 Gulf War; high-profile civil and ethnic conflicts following the Cold War; the ICBL and the 1997 Ottawa Mine Ban Treaty; and the growing role of NGO advocacy in international affairs. Together, these factors demonstrated contemporary problems in conventional arms proliferation and generated the normative shift toward “responsible” arms transfers. The success of the landmine treaty in particular, I argue in chapter 4, changed the social cost–benefit calculus performed by major exporters, who have found themselves facing changed expectations about conventional arms trade policies.

Finally, the chapter examines states’ arms export practice in light of these policy trends. It demonstrates that human rights have rarely been a significant consideration in small and major conventional arms export decision making. Practice rarely reflects policy. Human rights are largely insignificant for MCW transfers, which have long been wrapped up in exporters’ security, economics, and foreign-policy considerations. Yet even where policy discussions have been the most concentrated—small arms—the disconnect with practice is evident. Although, small arms exports showed a glimmer of emerging compliance from 1998 to 2010, the effect disappears when the analysis is broken down over time. In fact, in recent years the worst human rights violators have been more likely to receive small arms. Arms exports have long been free of international regulations and obligations, and these trends indicate that changes in line with new criteria are no guarantee. Perhaps concerns for human rights will become more important over time as policy expectations become more firmly entrenched in domestic and international politics. Or perhaps practice will remain unchanged if monitoring and enforcement mechanisms to raise the social and material costs of noncompliance continue to be elusive.56

The statistical analyses also provide essential insights into whether materialist and normative theories have it right or other explanations are in order. Not only has state practice not preceded changes in state policy, it has not followed policy, either. Clearly, commitment and compliance need not go hand in hand, as normative or materialist explanations would expect. In the end, the statistical analysis helps to rule out possible explanations for major democratic exporters’ support for humanitarian arms export restrictions. It is clear that states are not committing to new policies because these policies reflect existing practices and that they are not changing practice out of a deep normative commitment to new policies. The policy–practice gap remains wide. As a result, states’ commitment to legally binding standards becomes more puzzling. Why bother to sign on to such policies if they are not going to be implemented?

Given the statistical findings, the social reputation approach’s skepticism of the power of new norms to alter state behavior substantively in the absence of the means to impose reputational costs on noncompliance is well placed. In the case of the arms trade, international transparency measures are unconnected to “responsible” export commitments, allowing suppliers to continue with business as usual, knowing their decisions will rarely be subject to scrutiny. However, as I argue in chapter 5, where oversight in domestic politics can substitute for international monitoring, transfers may be relatively more restricted in cases of clear and severe cases of norm violations. Such cases are better able to capture media attention, rouse public ire, and threaten reputational damage at home. This means, however, that changes in practice may be concentrated at the margins among democratic exporters but minimal otherwise.

In the remaining chapters, I explore in-depth case study evidence in order to understand why major arms supplier states have signed on to initiatives such as the ATT and EU Code of Conduct. By examining historical and statistical trends, this chapter makes clear that states’ perceptions of material gains and normative commitments are likely weak in this case. Alongside the core social reputational approach, I also assess domestic liberal expectations that policy commitments are intended to serve the material interests of influential domestic groups as well as arguments that the ATT has followed the path of the landmine treaty, responding to public and NGO pressure. Yet in the absence of these incentives, domestic political explanations also fail to convince. Instead, I argue that states’ concern for reputation at home and abroad in order to achieve social gains and avoid social losses is key to understanding their commitment to costly new “responsible” arms export standards and the compliance gap.