As states began to ramp up support for humanitarian arms control policy in the late 1990s, arms trade practice was emerging from its historic secrecy. In some cases, revelations of past export behavior had damaging domestic consequences. In Argentina, for example, scandal broke in 1995 with reports of a series of secret deals sending thousands of tons of arms and ammunition shipments to Croatia and Ecuador between 1991 and 1995 (Deutsche Presse-Agentur 1995).1 It took six years to formally charge former president Carlos Menem in 2001 with authorizing the sales in violation of a UN embargo and a regional peace agreement. Despite his claims of innocence, most Argentines believed him guilty, but few believed he would be convicted. After being released a few months after his arrest due to lack of evidence, it took another ten years before an Argentine court would acquit Menem and seventeen other defendants, calling the arms deals a “foreign policy decision and a non-punishable political act” (Tarbuck 2013). But in 2013 the tide turned: an appeals court convicted Menem and a bevy of top officials of illegal arms smuggling and levied prison sentences ranging from four to seven years.2

The dealings reached deep into the Argentine administration, implicating fifty cabinet officials, military commanders, and personal advisers. A Buenos Aires news agency labeled the affair “an international blunder of unforeseeable magnitude for the country” (“News Agency Says” 1996). According to one official, it “complicated [Argentina’s] image abroad” (“Argentine Foreign Minister” 1996). Argentina has sought to compensate for these deals with a strong commitment to “responsible” arms transfers, becoming an ATT leader.3 Yet the costs of bad practice publicly revealed were even more tangible in domestic politics. The scandal ended political careers, further deteriorated trust in government, and embarrassed the government at home and abroad.

This is merely one arms trade scandal among many in the post–Cold War era, but it illustrates the difficulty of arms trade accountability, the far-reaching implications of scandal, and the importance of reputation to states and their leaders. “Irresponsible” or noncompliant arms export behavior often goes un-noticed, but when it is noticed, the consequences can be severe. Other states with reports of arms export scandals since the early 1990s include Belgium, Bulgaria, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the former Yugoslavia.4 EU members have been shamed for past arms sales to dictatorships in the Middle East and North Africa, spotlighted by the Arab Spring (M. Bromley 2012; Dempsey 2012). With growing transparency and shifting export norms, arms trade scandals have become more widespread. Because governments prefer to avoid the domestic reputational damage and political fallout scandals can cause, scandal—and threat of scandal—may in some cases help promote arms export restraint among democracies.

This chapter explores the effects of domestic political pressures on states’ compliance with their commitments to “responsible” arms export controls. For the most part, policy implementation has been weak, and changes in practice slow to appear. Decision makers rarely perceive material or normative incentives to pursue new arms transfer policies for a domestic audience. The defense industry, as I have shown, is a reluctant late supporter of multilateral controls and favors export promotion. The broader public, as this chapter demonstrates, is typically unaware of arms export policy and practice, with one important exception. Public attention to the arms trade is piqued by scandal brought on by media attention to violations of a state’s fundamental values and self-image through “irresponsible” arms exports.

I argue that it is the prospect of arms trade scandals and the cost to reputation—and with it, the cost to power and legitimacy—at home that affect how well governments implement new arms trade policies. Government sensitivity to arms trade scandal may not be able to provoke sweeping changes in export practice, but, lacking international enforcement, other options are limited. Governments’ perceived scandal sensitivity increases in tandem with improvements in transparency, allowing NGOs to spotlight “irresponsible” exports in the media and inflict reputational costs. The case studies reveal that both transparency and pro-control NGOs are necessary to improve accountability among democratic exporters, separate from—but perhaps aided by—international commitments to new export standards. For that small subset of scandal-prone cases where violations of rules and values are the most clear-cut and likely to come under public scrutiny, the policy–practice gap can begin to narrow. These findings suggest that transparency measures, although developed before new arms trade initiatives, can be harnessed to promote relatively “better” (though so far not “good”) arms transfer practices. It also has important implications for ATT implementation, which I discuss in the concluding chapter.

PUBLIC OPINION AND DOMESTIC STRUCTURE

At first glance, it might seem far-fetched to expect states’ arms trade policy and practice to reflect public opinion. The close relationship between governments and defense industries indicates that the preferences that count will not be those of the broader public but rather those of the defense industry. Industry has the political importance and the inside connections to make its voice heard. Although, as I have already argued, states have committed to new humanitarian arms trade controls in spite of defense industry preferences, the noncompliant export practices described in chapter 3 hint that industry wishes have not been forgotten. Indeed, the statist nature of arms transfer decision making suggests that any other societal influence would be hard pressed to make a substantive impact on state behavior. Across the board, arms transfers must be approved for export by government agencies through complex internal processes that are often understood by a handful of experts and not subject to advance public scrutiny.5 Moreover, if the public does care, it may do so to preserve industry to safeguard national security and employment.

When it comes to foreign-policy making in general, scholars are divided about the role of public opinion. Many question the public’s interest in foreign policy. Even at the height of the Cold War, only a few defense issues, such as nuclear weapons, stimulated cross-national public attention (Capitanchik and Eichenberg 1983). In the 1990s, policy makers perceived a decline of U.S. public interest in foreign policy in favor of domestic issues.6 Apart from a small “attentive” segment of constituents, the mass public is often described as detached from, uninterested in, and poorly informed about foreign-policy decisions, except possibly with respect to international crises.7 Moreover, it is less likely to focus on “complicated and more remote foreign policy issues,” such as arms transfers, leaving such affairs in the hands of the experts (Small 1996:69).

Literature on the “NGO-ization” of politics, however, suggests that security issues can be popularized with the right strategies (Petrova 2007; Price 1998; Rutherford 2000). For example, NGOs were able to engage public interest in a landmine ban by promoting a clear, simple campaign goal backed up by personal stories with humanitarian angles.8 The resulting groundswell of public support helped pressure governments into accepting new norms of APL nonuse (Petrova 2007; Rutherford 2000). In the case of small arms control and the ATT, pro-control NGOs hoped that the success of the landmine treaty could be replicated. However, similar tactics have been difficult to apply to conventional weapons more broadly. Guns and other military equipment are discriminant by nature. They are also basic tools for police and military and in some states legally owned by private civilians, making a ban unwelcome. As a consequence, the issue and message alike with respect to conventional arms are more complex and divisive in some countries: to restrain arms transfers under specific conditions—not simply to ban them. Yet this also means that a campaign to promote “responsible” arms transfers has difficulty resonating with the public with the same ease as one about landmines (Brem and Rutherford 2001; O’Dwyer 2006).9

Interviews confirm the more cynical view of public opinion when it comes to arms export controls.10 Government officials, NGO organizers, and industry representatives in all five cases believe that the public is uninterested and uninformed about arms transfers. Even in Germany, where public criticism of the arms trade is long established, the public does not have a sustained interest in arms transfer policies or activities. A bad image of the arms trade simply “does not express itself strongly.”11 People are often unaware of arms production, and the media typically finds the issue “too complex” to report on with regularity (interviews 11407255, 45207255).12 Similarly, although peace is a broad rallying point in Flanders and the public attitude toward the arms trade is negative there (Flemish Peace Institute 2007c), actual interest in relevant policies is low, just as it is in Wallonia, where the public tends to see arms exports more positively.13

This trend is even more pronounced in the other cases. The UK public and media—despite a well-developed NGO culture—are typically uninterested in the arms trade.14 In the United States, pro-control NGOs see the arms trade issue as “really a hard sell in general” (interviews 48207002, 50207002, 51207002).15 Although polls find that 57 to 60 percent of Americans support international arms trade regulations,16 it is a hot issue only among the NRA membership, opposed to such controls. Public opinion may therefore contribute to U.S. opposition, but it cannot explain U.S. support (see chapter 4). France, too, has signed on to new standards without any clear domestic incentives to do so. Government, NGO, and industry representatives report that the media and public remain uninterested in and unaware of the issue.17 Moreover, NGOs have acquired the expertise and professionalization necessary to influence arms export policy making only since 2006 as a result of the ATT process at the UN, after France had announced its support (interviews 59108220, 60108220).

Indeed, in all of the cases, interviewees observed that public pressure is not responsible for recent policy developments; the public simply is not interested. As a result, domestic structure18 is also less important for explaining states’ policy choices. Scholars often point to domestic structure as the mediator between public preferences, the groups that represent and shape them, and government decision making (Checkel 1999; Risse-Kappen 1991, 1995a). Yet where public preferences are ambiguous, weak, or absent, characterizing the structure through which they would travel loses value. Thus, liberal structures such as the United Kingdom, where governments should be more constrained by society, are as little constrained on arms export policy as more statist structures, such as France, where the state can typically dictate the direction of policy more freely.

Democracies are never fully immune from domestic constraints, of course. Although governments have faced little domestic pressure on their arms export policies, they have become relatively more sensitive to the effect that the implementation of such policies can have on their domestic image. As I show next, transparency and pro-control NGO activity can lead governments to perceive a greater likelihood of scandal stemming from (certain) arms export deals. When arms exports that deeply violate domestic and international values are discovered and publicized, they can create public attention where none previously existed. In the face of scandal, governments attempt to preserve their domestic reputation and political position. They may therefore approach clearly objectionable arms deals with more caution in order to avoid scandal and its reputational costs.

TRANSPARENCY AND SCANDAL: DOMESTIC COSTS FOR NONCOMPLIANCE

As much as the public officials and civil society leaders interviewed agree that domestic publics lack the interest, coherence, and force to influence states’ arms export policy choices, they also point without hesitation to one instance in which the public does pay attention. The unveiling of seemingly “irresponsible” or unscrupulous arms transfer deals sanctioned by the government against strongly held national values and international norms can spark scandal.19 Scandals generate public attention and outrage. Their consequences can include a loss of government legitimacy and electoral retribution. When faced with heightened threat of scandal, governments are more likely to avoid those arms transfers likely to raise public ire, but they are sheltered from condemnation as long as their behavior can fly under the public radar.

Until the 1990s, arms trade scandals were almost nonexistent, and governments could regularly transfer arms without fear of public backlash. Information about the arms trade was mostly hidden from public view, and civil society was largely unorganized to raise concerns. The point is not that scandal was impossible—after all, the United States had the Iran–Contra Affair—but that low-level transparency made these events incredibly rare and their threat minimal.20 As transparency initiatives have increased available information, however, the arms trade has become more susceptible to public criticism. When criticism is widespread, organized, and linked to clearly stated national values and international commitments, it can damage a government’s reputation. An active pro-control NGO community21 can serve as a watchdog, expose “irresponsible” deals in the press, and frame certain transfers as violating human rights and other national values. Such groups have claimed a growing presence in politics in recent years as NGOs have found a place in UN policy making and prominent scandals have prompted domestic groups to organize around the issue. This combination of active pro-control NGOs and arms trade transparency creates structural conditions that make arms trade scandal more likely in domestic politics.

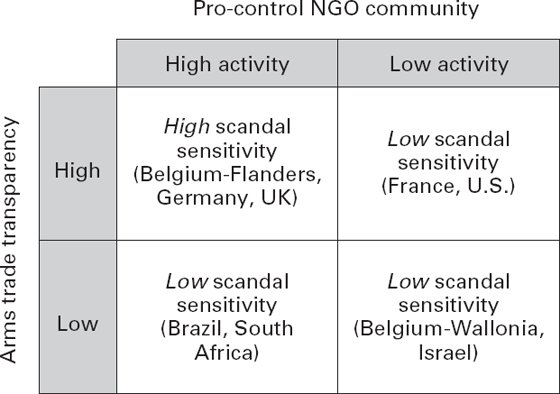

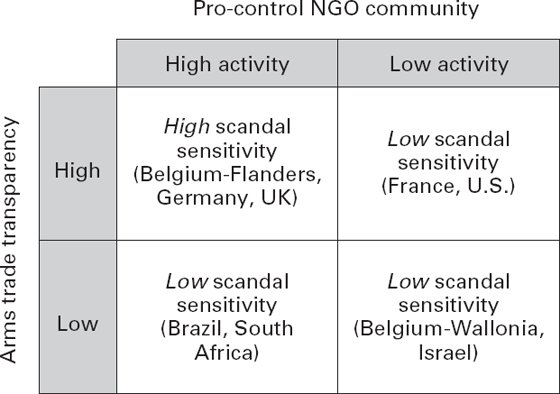

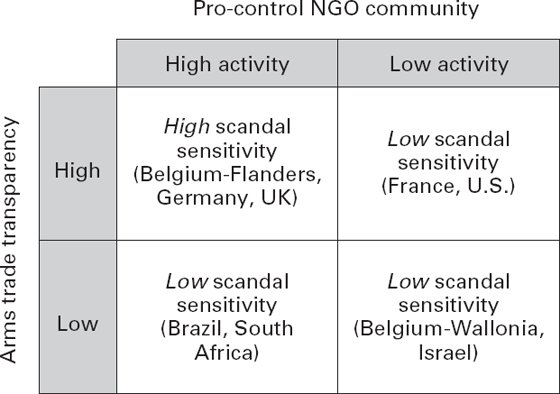

Figure 5.1 illustrates the importance of high levels of both arms trade transparency and domestic pro-control NGO activity for increasing governments’ scandal sensitivity. Under these conditions, governments may perceive a greater likelihood of arms trade scandal and become relatively more cautious in their choice of arms export partners. Where arms trade scandals have already tarnished governments’ reputation, this dynamic can be particularly potent. Scandals can prompt governments to improve transparency or NGOs to mobilize around arms trade issues, in turn easing scrutiny of future export decisions. Yet even where these conditions are present, only a small segment of cases might actually be prone to scandal and prompt better government compliance. Arms deals to the most egregious human rights violators and severe conflict zones may be best able to attract high-profile media attention and public backlash if revealed. In this way, the public may have a limited but powerful indirect effect on arms trade practice. However, in less clear-cut cases or where these conditions are absent, public interest may remain dormant, allowing government to pursue less “responsible” practices without fearing reputational damage.

FIGURE 5.1. SCANDAL SENSITIVITY IN DOMESTIC POLITICS.

TRADITIONS OF SECRECY AND SILENCE IN THE ARMS TRADE

Before the 1990s, only the United States and Sweden regularly issued arms export reports, and other states feared losing customers if deals went public. With the 1991 Gulf War, however, supplier states experienced firsthand the consequences of unchecked regional arms buildups and instituted the UN Register of Conventional Arms. Some states passed additional transparency measures at home in response to domestic fallout over secret arms sales to Iraq. The EU also included an information-sharing component in its 1998 Code of Conduct in response to NGO and EU Parliament lobbying to make such information public (M. Bromley 2012). Although unevenly executed overall,22 reporting became increasingly widespread among democracies especially and coincided with the growth of transparency norms in world affairs.23 Arms trade transparency has since enhanced scandal sensitivity by providing information about government practice, without which public accountability would be far more difficult.

Secrecy was long the rule in the United Kingdom, and not just for arms exports,24 making scandal outbreak difficult. Information about the arms trade was “hard to come by,” and the trade was thus “undebated” (Phythian 2000b:80). Before 1987, the United Kingdom did not maintain export-licensing statistics even for its own internal usage (UK House of Commons 1991, debate on April 26). Moreover, there was “a time-honoured lack of specificity about the details of individual defence export contracts, justified at least as much by reference to commercial as to state secrecy” (Gummett 1999:115; see also Phythian 2000a). This culture of secrecy dates back to the late 1800s but began to lose public credibility in the 1980s (Ponting 1990; Vincent 1998). By 1992, with the exposure of British defense exports to Iraq, it became a rallying cry for Labour’s successful bid for power against Conservative secrecy and the wider “culture of sleaze” in the 1997 general elections. Annual public reports began in 2000 after the new government led the adoption of the 1998 EU Code of Conduct.

Belgium also maintained a tradition of arms trade secrecy. However, revelations about exports to Iran and Iraq in the 1980s led the Parliament to institute an annual arms export report in 1991 (Carlman 1998; Flemish Peace Institute 2006). Nevertheless, public information remained “extremely succinct and confidential” (Mampaey 2003), and reports did not identify recipients until required by the EU Code. Regional governments have been in charge of annual reports since 2003, when they took over arms export licensing. Flanders has offered more frequent and detailed information about its arms trade than mandated by federal law (interviews 21407211, 24107211, 53207211). One expert stated that Flemish measures had progressed so that “the public knows more now than parliamentarians knew before” (interview 21407211). Wallonia adheres to federal transparency requirements, but reports can be more difficult to obtain (interviews 21407211, 2720721). A primary goal for Walloon groups is improved reporting to enable campaigning on specific cases or issues (interview 27207211). Increased transparency overall makes it possible for NGOs to react quickly to mobilize public opinion through the media on cases of problematic export deals in a way that was impossible before (interview 29207211).

Although France and Germany have contributed regularly to the UN Register since the 1990s, neither issued annual public reports until required by the EU. Their first reports appeared in 2000, covering transfers for 1998. Previously, Germany had “a very limited reporting process” and provided only aggregate arms export totals each year in accordance with its 1961 Weapons of War Control and the Foreign Trade and Payments Acts (Chrobok 2004:47; see also Carlman 1998).25 The French state had also “discourag[ed] a sustained flow of public information” (Kolodziej 1987:280). Starting in 1983, the French government gathered information relating to arms sales but kept it classified and released only aggregate information to the Senate and National Assembly on a postexport biannual basis. These reports also did not identify any specific recipient countries (Carlman 1998:14). French media and civil society did not attempt to fill the information gap on their own. Edward Kolodziej attributes their lack of activity in part to France’s lack of a “well-established tradition of investigative reporting … and a well-developed network of independent security and arms control research centers” (1987:281). Moreover, unlike Germany, France has not been shy about its aggressive export policies, which have largely avoided domestic criticism and are linked to a broad foreign-policy consensus and a desire for an independent military policy (Boyer 1996; Kolodziej 1987). Relevant NGOs have emerged along with transparency measures only in recent years. In response, officials have become more concerned about the public image of the arms trade, as I show later in this chapter.

Of the cases at hand, only the United States has a history of arms trade transparency predating the 1990s, making it “the most notable exception to the prevailing pattern of secrecy” in the arms trade (Lumpe 1999b; see also Kemp and Miller 1979; Schroeder 2005). Transparency in major conventional arms transfers was already a point of public concern by the late 1970s, connected to the perceived unchecked use of arms sales as a tool of foreign policy (Kemp and Miller 1979; U.S. Senate 1979).26 By the early 1990s, “the vast majority” of U.S. major conventional arms transfers were public (Goose and Smyth 1994:96). In 1996, the United States also began reporting disaggregated data about small arms transfers (Lumpe 1999b), making its policies in this regard an early model of openness (Schroeder 2005).

Yet even as national arms export reporting has spread since the 1990s, more information does not automatically lead to more accountability, as the U.S. case shows. The presence of an NGO community willing and able to call governments to task on their “irresponsible” exports is also necessary. NGOs seek out and comb through reports to spotlight questionable deals in the media and public. As the cases show, without both arms trade transparency and active pro-control NGOs to spotlight apparent government hypocrisy, scandal is possible but not feared. Together, they can increase governments’ scandal sensitivity and drive them—in some cases—to be more selective about their export partners. A major scandal can also enhance a government’s scandal sensitivity directly by teaching it firsthand the potential costs of scandal and indirectly by prompting legislative reform and NGO activity. The key point, as I demonstrate in the following sections, is that the anticipation of criticism and scandal can push governments to scrutinize and better justify arms export decisions that they anticipate might trigger public outcry if made known.

THE UNITED KINGDOM: SCANDAL AS INCENTIVE FOR LEADERSHIP

The British Arms to Iraq scandal broke in the wake of the 1991 Gulf War and helped the Labour government get elected in 1997, prompting policy changes and international policy leadership. New transparency measures, a commitment to “ethical” arms transfers, and a newfound role for NGOs in the policy-making process, have had consequences for British scandal sensitivity and arms export practice. These changes place the contemporary British case in the high-transparency-active NGO category, giving existing NGOs clear standards by which to judge government export behavior and more information by which to do so. The government, in turn, has become more concerned about its domestic reputation and arms exporter image, although for some critics at the expense of more substantive, far-reaching reform (Cooper 2006; Stavrianakis 2008, 2010).

ANATOMY OF A SCANDAL

The Arms to Iraq scandal tarnished the ruling Conservative Party’s reputation and helped usher in a “totally different world” of arms export decision making (interview 32107200). In the late 1980s, British media did not widely consider clandestine arms sales to Iraq an issue worth pressing (Negrine 1997). Yet by 1996 the Financial Times had denounced the British arms trade as “a culture corrupted by the absence of checks and balances against the power of the executive and by an obsession with secrecy” (Stephens 1996). It was the Iraqi use of British weapons against British troops in the Gulf War that raised public ire and party politics that kept it going. The resulting scandal changed the terms of the arms trade debate and public expectations for government practice and contributed to the 1997 Labour victory and its commitments to government transparency and “ethical” arms transfers. These policy changes have left the government more sensitive to the threat of arms trade scandal, even as it seeks to support exports abroad and defense industry employment at home.

The illegal sale of British arms to Iraq during the 1980s initially appeared to be the sole responsibility of private firms. Published policy from 1985 clearly prohibited the transfer of any lethal equipment to Iraq (Cooper 1997; Leyland 2007). Throughout 1990 and 1991, officials claimed the policy had not been changed and denied the legal sale of arms to Iraq by British firms (UK House of Commons 1990, debate on December 3, and 1991, debates on January 31 and July 1). The blame instead fell—at first—on three executives from defense manufacturer Matrix Churchill, who went on trial in 1992. The trial collapsed, however, when former minister of trade Alan Clark testified that the government had known of the sales all along (Pilkington 1998; Tomkins 1998). He also admitted to counseling companies to “stress the civil applications of their equipment [in their license applications] even though they knew that it would be put to a military use” (B. Thompson 1997:2). From Clark’s admission, it became clear both that the government had supplied arms to Iraq that were used against British troops and that it had made a “secret change of policy” on arms sales, which it kept from the Parliament and the public (House of Commons 1992, debate on November 10).

One day after Clark’s testimony, Prime Minister John Major called for an independent investigation, to be run by Lord Justice Sir Richard Scott. According to Colin Pilkington, the investigation was “[t]he most severe test of government secrecy and ministerial accountability for many years” (1998:198–99), illuminating in excruciating detail hidden governmental practices. The government had reportedly not intended the investigation to take on such a broad scope (Norton-Taylor, Lloyd, and Cook 1996:31). Nevertheless, Scott’s inquiry took three years, interviewed 276 witnesses, including Major and Thatcher, and reviewed two hundred thousand pages of official documents. Its findings, released in the 1996 Scott Report, stated that the government had purposefully and repeatedly “misled parliament in breach of ministerial accountability,” prevented “crucial evidence about arms sales being revealed,” and “collectively conceal[ed] government policy from parliament” (Pilkington 1998:201; see also Cooper 1997; B. Thompson 1997; Tomkins 1998).

The issue captured public attention and was followed closely by the news media. Why did the Scott inquiry resonate when the arms trade otherwise did not? Two reasons, unrelated to the exports themselves, are key. First, the inquiry simply made for “good entertainment” (B. Thompson 1997:1; Tomkins 1998). As Matthew Baum argues, scandals and trials can be “easily framed as compelling human dramas” and attract soft news media and consumers not ordinarily interested in politics or foreign policy (2002:91). The Scott inquiry contained “the ingredients of a good popular drama, spies, criminal trials and internecine squabbling amongst ministers and officials” (B. Thompson 1997:1). Guardian reporter Richard Norton-Taylor even cowrote a play based on the inquiry, which ran in London (Norton-Taylor and McGrath 1995).

Second, the “sleaze factor” came into its own with the Scott inquiry (Lee 1999; Phythian 2000b). For secrecy and hypocrisy to trounce accountability in a democracy was itself scandalous. Multiple sex scandals and minor arms trade scandals had plagued the Tory government, and Arms to Iraq was the biggest, spreading the blame to the party as a whole.27 What was most clear to the electorate was “the hypocrisy and hint of double standards” (Pilkington 1998:184). Indeed, it was the issue of accountability on which most press reports focused.28 Opinion polls showed that 87 percent of the public “thought ministers had misled Parliament, and 54% had done so deliberately,” and more than 60 percent were in favor of ministerial resignations (“The Scott Report” 1996). It was felt that such illegal and secret trades were simply unacceptable behavior for a good democracy, a sentiment echoed in debates in the House of Commons and House of Lords (UK House of Commons 1996, debates on February 15, 19, 26).

The immediate political aftermath was surprisingly minimal given the uproar the scandal had caused. Analysts argue that the length of the report, combined with Scott’s vague language, made it subject to spin on both sides (Negrine 1997; Pilkington 1998). The government gave itself eight days’ advance access to read the 1,800-page report before the parliamentary debate on publication day, compared to three hours given to Parliament member Robin Cook as the Labour representative (Pilkington 1998:201; Norton-Taylor, Lloyd, and Cook 1996). The government survived a vote of confidence by one vote, and the Scott Report faded from public attention (Tomkins 1998:13). By the 1997 election, however, it returned. The public had begun to condemn “all government ministers as shifty” (Pilkington 1998:202; Vincent 1998). Labour itself “made much use of the Scott Report” (Lawler 2000:293), stressing themes of ethics and transparency as a part of its election strategy (Worcester and Mortimore 1999:71). In this sense, the scandal was the catalyst for policy change that, as I describe next, has made the government more sensitive to future scandal.

CONSEQUENCES FOR ARMS EXPORT DECISION MAKING

In the words of one official, “the Arms to Iraq scandal had a dramatic effect” on the new Labour government, even if the changes were not immediate or automatic (interview 41107200). Not only did Labour have “to contend with the same pressure against sleaze in the changed climate” after the Scott inquiry (Lee 1999:301), but it had also provided a baseline of commitments against which its own progress could be measured. Its promised reforms—to engage in an ethical arms trade, overhaul arms export legislation, and make transparent the processes of policy making in the arms trade and otherwise29—provided civil society with both the standards by which to judge its progress and the means to do so. Although these commitments were coupled with others to support defense exports and employment, they were a departure for British defense export policy, which earlier had not existed apart from “the longstanding objective of increasing the volume of sales of conventional weapons,” with export decisions “made on an ad hoc and pragmatic assessment of changing, and often conflicted, British interests” (D. Miller 1996:360).

Labour had in essence “paint[ed] itself into a corner,” requiring that it take action when it came to power (interview 37207200). Appointing longtime arms trade critic Robin Cook as foreign minister helped signal its commitment to the cause. It also took a highly visible leadership role on arms exports in multilateral fora and opened up export decision making to scrutiny by NGOs. These policy changes not only helped build the government’s domestic and international reputation but also greatly increased its scandal sensitivity. Once shut out of policy making, NGOs—including Amnesty International, Oxfam, Saferworld, and others—were invited in.30 Arms trade transparency also went from a limited practice at best to an extensive practice with an “unprecedented” level of detail and frequency (Gummett 1999:115), enabling new scrutiny of export practices.

The Labour government introduced a role for NGOs in policy making that the previous government had resisted. Several years before the 1997 elections, Labour had begun to work with pro-control NGOs on its foreign-policy agenda (interview 35207200). NGOs also provided some of the expertise needed to make criticisms of Conservative arms trade policy and practice during the Arms to Iraq affair (interview 37207200). The consequences of “cozying up” to NGOs while in opposition, however, meant that the postelection period became “payback time for NGOs” (interview 32107200). Groups continued to work with Labour, which opened up bureaucracies to their input as a matter of good public relations.31 As one official stated, “It makes sense to take their opinions seriously” when NGO media access could mean potential embarrassment through reports and articles in the press (interviews 40107200, 41107200, 43107200; see also Grant 2000).32

Also as a result of the Scott inquiry and its findings, the Labour government began to lift “the veil of secrecy” hiding arms export decision making (Phythian 2000b:81; see also Gummett 1999; interviews 32107200 and 41107200). Publishing an annual report has made UK arms trade practice “subject to scrutiny,” whatever the ruling party (interviews 41107200, 32107200). In the past, the “sweeping categories” used to fulfill UN reporting requirements effectively hid the substance of British practice from view and made criticism by Parliament or NGOs difficult (Gummett 1999; Tomkins 1998). In contrast, newer, more detailed reports show Parliament, the media, NGOs, and the public “the types of arms-related equipment provided by British companies to particular countries” and reveal where the problems lay (Gummett 1999:115).

Foreign Minister Cook presented the first annual report to the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs, stating, “We can all take satisfaction that Britain is now the most transparent of all the European countries in how we handle arms licences.” He added that the reports should “enable Parliament, public, NGOs, to invigilate whether we are standing by [the new] criteria, making sure that we are not breaking those criteria” (Cook 1999, testimony on November 3). Parliamentarians and activists took him up on it. Questions on arms transfers to Indonesia, Pakistan, China, Zimbabwe, and other locations arose immediately (Lawler 2000).33 In its first report, moreover, the administration listed some “questionable shipments” to Sierra Leone during its first eight months in office (Lawler 2000:292). Cook and the administration were tainted by the subsequent Arms to Africa affair, which taught them early on that NGO involvement and transparency may not only serve their domestic reputation but also harm it. More recently, in 2012, a report from the All-Party Parliamentary Group on International Corporate Responsibility critiqued government export credits, including arms deals to Saudi Arabia and Zimbabwe.34

Party image and reelection are major concerns for politicians, and the British are no exception. What changed in the United Kingdom was not these concerns, but the ease with which a party’s reputation could be damaged. Labour also sought to promote arms exports, but with the growth of transparency and NGO activity, officials “seem genuinely worried” about the potential consequences (interview 35207200). Amnesty and Oxfam in particular “can mobilize significant constituencies,” and Labour might easily lose support from voters important to it (interview 35207200). NGOs have adapted their strategies by seeking to get the media interested and asking questions to build public attention to certain cases (interviews 32107200, 33207200). The arms trade “doesn’t become an issue until you get headlines,” and scandals “raise [its] profile.”35 Simply stated, “Ministers care about what gets on the front page” (interview 35207200). With NGOs watching and waiting, the government became more keenly aware of the public-relations problems that “irresponsible” arms exports can create and claimed a more restrictive approach to its arms trade practices. The Tory-led Cameron government has continued the United Kingdom’s public commitment to “responsible” arms exports. Moreover, its rapid decision to revoke licenses to North Africa and the Middle East in light of the Arab Spring suggests concern for how arms exports to a repressive region in the public spotlight will be received (Saferworld 2011).

GERMANY: HIGH SENSITIVITY AND ACTIVE CIVIL SOCIETY

The German case highlights a longtime public commitment to restrictive arms export practices that has been called to account more reliably in recent years as NGOs have gained access to government arms export reports. Since World War II, Germany has been extremely sensitive to arms trade scandals and has experienced public backlash in response to some of its export decisions. As transparency measures have grown to accompany an established and active NGO community, the German government continues to be a relatively more scandal-sensitive case. Yet in recent years it has also occasionally sought—in “a wide break from the German foreign policy consensus” with widely unpopular results—to use weapons supplies to counteract growing demands for German troops abroad, demands that sit uncomfortably with its civilian power identity (von Hammerstein et al. 2012:21).

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Germany’s arms transfers have been powerfully shaped by World War II (Davis 2002; Pearson 1986; Wulf 1996). As the federal minister for economics stated, “The uncontrolled proliferation of weapons, as well as industrial goods and knowledge with the weapons can be produced, leads to a grave danger to the peaceful co-existence of people. In this knowledge, and also on the basis of Germany’s historical experience, the Federal Government feels a special responsibility for a restrictive Arms Export Policy” (German Minister for Economics 1993:1).

The arms industry was closely affiliated with Hitler and the Third Reich, becoming a symbol of militarism from which postwar Germany sought to distance itself. Over the years, domestic opposition to arms transfers has been strong (Brzoska 1989; Davis 2002; Pearson 1986).36 Governments have responded to this political unease by prohibiting arms deliveries to “areas of tension” in 1965 and abandoning all major military aid programs by the end of the 1960s (Davis 2002:156; see also Cowen 1986). Officials have also avoided the appearance of using arms transfers as a foreign-policy tool and, unlike most other major arms producers, have declined to promote arms sales abroad (Davis 2002; Pearson 1986). Laws have been designed to “achieve the benefits [of arms transfers] without the stigma” and to avoid the embarrassment of approving problematic export requests (Pearson 1986:532, 533). Politically sensitive arms export requests are adjudicated not by bureaucrats in the Federal Office for Economics and Export Controls (Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfuhrkontrolle) but instead handed up to an interagency commission.

In 1980, pending arms deals to Saudi Arabia and Chile initiated a public debate over specific decision-making criteria. As Regina Cowen observes, “Governmental disengagement and the consequential divorce of arms exports from foreign policy [had] greatly encouraged the commercialization of arms transfers,” leading to serious concerns about a “credibility gap” between arms export law and practice (1986:269). Yet the debate was not about loosening restrictions; indeed, there was broad consensus to maintain a restrictive stance. Rather, it focused on how to better define existing political rules and organize the decision-making structure (Cowen 1986:269).37 Following the adoption of export guidelines in 1982, the proposed deals to Saudi Arabia and Chile were denied (Cowen 1986:270). The public has also made clear over time its disapproval of specific arms deals, including to Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Israel.

Public attention has both generated and been sustained by an NGO community that pushes arms export restraint, which “has been an important issue of morality and political culture for a wide variety of groups and institutions” (Davis 2002:160; see also Brzoska 1989). Amnesty Deutschland, Oxfam, peace research institutes, religious groups coordinated through the Joint Conference Church and Development (Gemeinsame Konferenz Kirche und Entwicklung), labor organizations, and the Berlin Information-Center for Transatlantic Security have all taken an active interest in the arms trade. In recent years, small arms NGOs have gathered monthly with relevant government bureaucracies to discuss developments in small arms and other conventional arms control policy (interview 14107255). New transparency measures since 2000 have made government decision making more public. Thus, although the German public—like the public elsewhere—is typically focused on internal issues,38 it has also demonstrated a continued discomfort with arms exports in the context of international peace and its own postwar identity.39 Controversy across the political spectrum over Chancellor Angela Merkel’s more liberal arms export practices in recent years further illustrates the broad public consensus over arms export restraint. Merkel knows that arms exports are unpopular among voters, especially “if authoritarian regimes like Saudi Arabia secure their power with German weapons” (von Hammerstein et al. 2012:25). With Afghanistan still fresh in everyone’s mind, she has nevertheless risked paying the social costs, hoping to avoid even more unpopular decisions down the road to send troops into conflicts overseas.

CONSEQUENCES FOR ARMS EXPORT DECISION MAKING

German press and civil society groups had begun to pay careful attention to arms export practices even before official reporting began in 2000.40 Otfried Nassauer and Christopher Steinmetz observe, “Heated discussions regularly ensue on the political and moral acceptability of shipping tanks, rockets, submarines, or personnel carriers abroad” (2005:1). Such discussions, however, have not meant that the government has exported only to controversy-free destinations. Rather, it has simply sought to avoid the public appearance of irresponsible arms transfers to avoid reputational costs at home. First, it has used coproduction arrangements to bypass more stringent domestic restrictions, suppress arms export tallies, and avert public condemnation for certain deals (Brzoska 1989; interview 11407255). For example, coproduction arrangements allowed German antitank missile exports to Syria from France in the 1970s and the export of German missiles to Taiwan from the United States in the early 1990s (Peel 1993).41 Second, decision makers have a “declared preference [for] sales to NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] countries,” which face lower restrictions in German law and generally do not present strong human rights concerns (Davis 2002:157). However, with the exception of Turkey, as I explain shortly, NATO exports are also not controversial among the public, which values alliance cooperation.

NGOs—especially with improvements in arms trade transparency—keep a watchful eye on the government’s export decisions. Officials are keenly aware of the potential for scandal as they adjudicate export requests (interviews 14107255, 58107255). Governments have gotten into the most trouble over export decisions where the legalistic approach has insufficiently reflected national values.42 For example, although human rights was not a criterion for refusing arms transfers until 2000, already in 1993 the Kohl government came under fire for exporting used East German ships to Indonesia because of violations in East Timor (Peel 1993).43 By 2003, Germany no longer permitted arms transfers to Indonesia, and weapons once supplied by German companies came instead from Turkey and Pakistan through licensed production (Kleine-Brockhoff and Kurniawati 2003).

Arms transfers to Turkey have been a particularly sensitive subject, pitting support for human rights against support for NATO.44 Yet although German export law and practice privilege NATO allies, Parliament embargoed Turkey in November 1991 in response to human rights violations against the Kurds (Davis 2002; Kinzer 1992). The Christian Democratic Union (CDU, Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands) government—apparently without top officials’ knowledge—attempted to reconcile its problem by covertly supplying fifteen tanks to the Turkish government. The strategy backfired. In March 1992, Turkish forces attacked Kurdish areas with what witnesses reported to be German-made tanks. The Panzeraffäre spread, Defense Minister Gerhard Stoltenberg claiming that his officials had supplied the tanks without his knowledge. With state elections scheduled for early April, the Social Democratic Party (SPD, Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands) highlighted the scandal in its campaign, even naming as an arms trafficker rival CDU candidate who was a former Defense Ministry aide (Kinzer 1992).45

Fearful that damage to the government’s image would worsen despite its postreunification popularity, Stoltenberg dismissed senior aide Wolfgang Ruppelt in hopes of ending the affair (M. Fisher 1992; Kinzer 1992; “Unter dem Druck” 1992). This tactic also failed. Calls for a sign of responsibility at the top grew, and Stoltenberg finally gave in to public pressure and resigned.46 The Süddeutsche Zeitung, the major newspaper in the CDU stronghold of Bavaria, declared that “the illegal tank delivery to Turkey has now conclusively ended the political career of the minister”—a man once considered a possible future chancellor (“Kritik an Stoltenberg” 1992). Chancellor Helmut Kohl and the press alike declared Stoltenberg’s duty to resign, whether he had known the illicit transfers had taken place or not (Casdorff 1992). In turn, the affair left that generation of CDU leaders acutely aware—by firsthand experience—of the high costs to be paid for politically unpopular arms transfers.

Arms exports to Turkey have since been treated with a greater degree of caution for fear of political backlash (interview 45207255). The CDU government installed another embargo against Turkey in April 1994 just prior to elections (Davis 2002; Sariibrahimoglu 1992) and denied transfers in 1999 in response to civil society pressure (interviews 18207255, 19407255, 45207255). In 2003, the SPD government declined a tank order to prevent its coalition with the Greens from collapsing. Tank exports specifically became much more difficult because of the use of tanks in Turkey’s human rights violations, despite the importance of the land armament vehicle sector for the German defense industry. Other defense goods, such as ships and submarines, pass through the export decision-making process with greater ease and less political concern (Mulholland 2003).

NGO and media criticism of numerous arms transfers since the mid-1990s have stopped some noncompliant sales from going forward to prevent further public backlash—but, as the 2011 Saudi Arabian tank deal showed, certainly not all. The public becomes more attentive when a deal explodes in the press and becomes a scandal with political liability.47 It was difficult to cultivate sustained improvements in government practice in the 1990s without transparency (interview 11407255), but, according to one NGO representative, new transparency measures since 2000 have enabled a central mobilizing strategy targeting the government’s policy–practice gap: “The biggest difficulty is being heard. With scandals, [public] interest picks up; you need examples to awaken interest. The easiest way to act is to look at the export report and use what’s already public. We criticize in relation to political guidelines, the law the government sets out for itself, and its obligations” (interview 17207255).

High-profile conflicts and severe human rights abuses serve as potential scandal material for organizations scrutinizing export reports. Industry analysts note, for example, that the government would be unlikely to grant export licenses to China even if the EU arms embargo were lifted, “as human rights issues there would raise too much opposition” (Mulholland 2005:22). In 2002, after pressure from NGOs in the press, the government denied small arms exports to Nepal. Prior to the decision, Amnesty and other groups noted that Nepal was embroiled in internal conflict and engaged in massive human rights violations. Approving the license would therefore be a clear violation of German export law and policy (Deutsche Gewehre 2002). The government listened, and NGOs counted it a victory (interview 17207255)—but not one easily repeated elsewhere, as the Belgian case demonstrates.

More recently, however, the Merkel government has pushed the boundaries of acceptable arms export practice in Germany, facing widespread public backlash for secret deals exposed and denied. In 2011, officials publicly denied making a deal to sell 270 Leopard tanks to Saudi Arabia after press reports of a similar deal leaked earlier in the year drew protests and outcries of scandal (“Saudi-Arabien” 2011). Similar deals were delayed in response but in some cases have since been approved. In 2014, reports surfaced that divisions within the government over sending battle tanks to Saudi Arabia may have stalled or ended the deal altogether (Agence France Presse 2014). Despite multilateral commitments and domestic anger, Merkel has sought to implement dramatic changes not just in German arms export practice but also in national arms export policy. For Merkel, the perceived failures of Afghanistan loom larger than arms trade scandal, prompting weapons sales to regions of potential conflict so that those countries can use them instead of German soldiers to maintain peace and stability down the road (von Hammerstein et al. 2012:25). She has conceded to providing the Bundestag more information sooner on new deals but has rejected calls for a new arms trade supervisory body.

Concern for national and international norms is expected for Germany with its civilian-power-based foreign policy.48 Clearly, however, government restraint in arms export behavior is not simply self-motivated, rooted in identity and deeply embedded normative commitments. CDU and SPD governments alike have pursued arms transfers contrary to stated national values, only sometimes pulling the plug due to public backlash. The pressure of public accountability and the fear of the high costs of scandal have thus motivated some compliance. But it also shows that perceived political expediency may come at the expense of arms export restraint, especially when the various demands of civilian power clash with each other and political power is not credibly threatened.

FRANCE: LOW SENSITIVITY WITHOUT NGOS

France has taken a place in the high-transparency-active NGO community category only since 2006. French NGOs began to organize around the arms trade issue in 1998 in response to revelations about French arms deals to Rwanda in the early 1990s. Scandal was a catalyst not for government policy reform but for emerging NGO activity. However, NGOs were unable to mount sustained lobbying and mobilization efforts until after the ATT process got under way at the UN. Transparency, too, was poor until new measures were adopted in 2000 in response to the EU Code of Conduct. The threat of scandal therefore remained low in the eyes of the government, while new NGOs struggled to engage on the issue, and transparency was lacking.

THE RWANDA AFFAIR

France has long pursued aggressive arms transfer practices with little public criticism. Without NGOs to push the issue, the media have maintained a largely apolitical stance. Even in cases of would-be scandals, they have refrained from probing too deeply to gather information or expose evidence. This is not for lack of potential material. France has often received criticism from outside its borders for its arms export deals. It has an active arms trade with Francophone Africa, has transferred large volumes of defense materials to Iran and Iraq during the 1980s, and has liberally interpreted the EU arms embargo to China. As a result, the case demonstrates not only the difficulty of inciting arms trade accountability but also, with the Rwanda Affair, the transformative role scandal can play in mobilizing NGO interest in the arms trade.

During the Cold War, even severe violations of national law had difficulty creating any traction for arms trade scandal. For example, in November 1987 reports surfaced that despite an arms embargo France sent $120 million of arms to Iran from 1983 to 1986 (Gaetner 1987; Greenhouse 1987; Pontaut 1987). A secret Ministry of Defense (Ministère de la Défense) follow-up to the 1985 l’Affaire Luchaire (named after the arms manufacturer responsible for the sales and initially believed to have acted without government knowledge) suggested that the deals had taken place with the tacit approval of top officials in the Socialist government.49 By some accounts, moreover, kickbacks of 3 to 5 percent had landed in Socialist Party coffers. The news was leaked to pro-right magazines by the then prime minister Jacques Chirac, who was lagging badly behind François Mitterrand in the polls in the lead-up to the 1988 presidential elections (Greenhouse 1987; Webster 1987a).

Yet despite the ingredients for a good scandal—seemingly corrupt high-ranking politicians, secret embargo-busting shipments to a country affiliated with terrorist attacks and hostage holders, an official denial, and an upcoming election—the affair soon died without causing political damage or affecting the public arms trade discourse. The reasons highlight both the lack of sustained public interest and the lack of nonstate actors capable of instigating sustained public interest. It was unclear the degree to which Mitterrand himself could be touched by the accusations, and the corruption charges were a relatively nonprovocative issue among voters (Hoagland 1987; Jacobson 1987b; “That Damned Elusive Mitterrand” 1987). The public was overwhelmed by a plethora of scandals amid the preelection “scandal wars” (Webster 1987b), which lessened the impact of the news and reinforced the cynicism with which voters had begun to view all politicians (Jacobson 1987a; Markham 1987a). The public also did not appear shocked by the developments. Arms exports were not often publicly questioned. For many, defense policy was simply “sacred ground and out of bounds” (Webster 1987a). And without the presence of NGOs, the apparent indifference of the media and public—a silence both pervasive and deliberate, according to Jean-Paul Gouteux (1998:230)—could go uncontested.

Most importantly, the ministry report emerged in the middle of a recession, when economics issues trumped all others among the electorate and was already a key driving force behind the French arms trade (“That Damned Elusive Mitterrand” 1987). The report clearly “establishe[d] that the Socialists’ decision to overlook these exports grew out of official concern that nearly 1,000 jobs would have been otherwise lost in the factories run by the Luchaire company” (Hoagland 1987; see also Markham 1987b). Instead of violating French values, the deals were seen as confirming them—medicine for an ailing industry important to employment and economic well-being (Webster 1988). The issue was for many not a matter of morality and irresponsible exports but rather effective policy making by whoever was responsible within the government (Echikson 1987).

After the Cold War, the possibility for critical media attention seemed to have emerged in reports of French arms transfers to Rwanda. Yet the absence of an active NGO culture50 initially left calls of foul play to sources outside France. France was a major supplier of arms to Rwanda after the start of the 1990 war and the 1993 Arusha Accords.51 Arms flows and training were (and still are) key parts of French military cooperation in Africa, and French military relations with Rwanda dated back to 1975. This was no secret—France treated Rwanda like its former African colonies. The key questions were whether France shared in responsibility for the 1994 genocide and whether it had violated the May 1994 UN arms embargo.

France only acknowledged deliveries from 1990 to April 1994, when the massacres started. In 1994 and 1995, however, foreign NGOs released evidence in the international media accusing France of sending arms to Rwanda after it knew of the genocide and after the UN arms embargo was imposed (Austin 1995; HRW 1994). The big media splash came from a 1995 BBC report including testimony that France “had delivered munitions to the FAR [Forces armées rwandaises (Armed Forces of Rwanda)] when the genocide had already been underway two days” (McNulty 2000:115). Belgian journalist Colette Braeckman found further evidence of a May 1994 arms deal (1994:116). An HRW report (Austin 1995) claimed that French arms shipments after May 1994 were simply diverted through Zaire.

The weapons were said to have “expanded the conflict,” “facilitated violations of international law[,] … and increased human rights abuses” (Goose and Smyth 1994:90). Although machetes were the weapons of choice, small arms were also instrumental in rounding people up for easier and more efficient mass killings (Goose and Smyth 1994; Verwimp 2006). Although the French media briefly reported the government’s alleged “complicity in the genocide” (Callamard 1999:157), both the media and government were largely unresponsive to external pressures. Without NGOs inside France to sustain domestic criticism, what might have had devastating political consequences elsewhere died down with little significance in French politics.

It took another four years to initiate an official inquiry into the events. In 1998, Le Figaro broke with tradition and accused the government of supplying the missiles used to shoot down Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana’s airplane, alleging that it had continued arms shipments into the summer of 1994 (Burns 1998; “France Denies” 1998).52 The government claimed that all shipments were halted on April 8, more than a month before the embargo. Yet in a rare turn of events media criticism was heavy enough and public sensitivity to genocide strong enough (La Balme 2000:274) that the government appointed its first-ever parliamentary commission to look into French overseas military activity. With global humanitarianism and the birthplace for human rights central to French identity (McNulty 2000:105; Tinsley 2004), complicity in the genocide seemed a fundamental violation of French national values.

The Quilès Commission was groundbreaking. African policy “was traditionally an area shrouded in mystery and run from the president’s office” (Melvern 2000:233). However, the commission’s report was not similarly novel.53 It declined to make any conclusions related to arms trade practices and absolved France of any responsibility for the killings, despite some errors in judgment (Whitney 1998). The source of the weapons also went unaddressed (McNulty 2000). In fact, the report eschewed the arms issue altogether. Rather than being an exercise in transparency and accountability, it simply “repeated rumour, speculation and intrigue and to date the most basic facts have still to be established” (Melvern 2000:234).

Once again French policy traditions and the dearth of organized civil society combined to prevent a scandal from imposing damaging consequences on politicians.54 First, because the investigation did not offer conclusions on the arms trade, the issue remained shrouded in secrecy and essentially dropped away with no one to revive it. Relevant NGOs were new and weak—formed in response to the affair (McNulty 2000:106)—and had not been integrated into domestic discourse. The press remained reluctant to push the government too far. And although public attitudes toward humanitarianism had become more pronounced in the midst of the 1997 landmine campaign, l’Affaire du Rwanda resulted in no direct repercussions for the government.

Second, France’s Africa policy gave considerable discretion to the executive and shielded it from domestic criticism (Kroslak 2007). France treated Rwanda as if it were a French colony and maintained close relations with its government (Callamard 1999; Klinghoffer 1998; Melvern 2000). The support seemed natural: the Hutu had “had a social revolution, constituted the majority, and Habyarimana, like one of the leaders of the French revolution, would eventually emerge as the strong man of the democratization process” (Callamard 1999:173).55 France also wanted to ensure that Rwanda stayed within “the Francophone fold,” a key policy concern since 1990 (Klinghoffer 1998:86; see also Callamard 1999; Kroslak 2007). The institutionalized relations and dependence of Francophonie was perceived as a cornerstone of France’s continued global grandeur and advancement of global interests (Gregory 2000; Kroslak 2007). Thus, although misjudgments may have been perceived, France’s overall policy did not diverge from accepted practices.56

CONSEQUENCES FOR ARMS EXPORT DECISION MAKING

The Rwanda Affair did not have any direct consequences for French arms trade practices, nor did it inspire legislative reform. Significantly, it did spark civil society organization on the arms trade.57 However, NGOs remained weak until 2006, stopping policy makers short of developing a heightened sense of scandal sensitivity and leaving media a passive actor. Although a new discourse of “responsibility” arrived in French politics as a result of events in the 1990s (Roussel 2002), it remains to be seen how fully it will translate to arms exports. The nascent NGO community born of the Rwanda Affair has become more professionalized since the 2006 ATT process, opening up new avenues for accountability to regional and international norms and agreements. Greater transparency, too, has come about due to international commitments.

Minor scandals since 2000 have so far lacked the teeth to encourage serious reform. “Angolagate”—in which government officials were charged with trafficking Soviet-made weapons to Angola during the 1990s—resulted in the arrest of Mitterrand’s son and former Africa adviser Jean-Christophe Mitterrand in 2000 (Gee 2000; Henley 2001). In 2004, he was found guilty, fined, and given a suspended jail sentence. In 2009, Interior Minister Charles Pasqua was also convicted of corruption charges, responding with, as one report put it, a call “for an end to the official secrecy act on documents concerning arms sales” (Hollinger 2009). The arrests and initial trials appeared to mark a change in French responses to arms trade scandal and a somewhat more aggressive media with a lower public toleration for corruption (Bell 2001; interview 60108220). However, an appeals court acquitted Pasqua on all charges in 2011 and cleared other defendants of arms-trafficking charges, leaving the impression that perhaps the French justice system was not so concerned with arms sales after all (Thréard 2011).

Although one official claims that “in a democracy, regardless of whether there are strong NGOs, everyone is afraid of what can be said” (interview 59108220), France’s reputational concerns began to appear only with the professionalization of the NGO community since 2006. Officials now express image concerns connected to France’s arms trade and increasingly fear the negative public attention arms trade scandals generate (interview 59108220). Arms export decision makers are careful to keep detailed records, showing exactly what has been transferred and that each transfer is within the law: “You have to leave things crystal clear for years down the road when they could be questioned” (interview 59108220). Officials also take care to note what they see as the highly restrictive nature of French arms export law. They add that France has largely ceased to export small arms to Africa because of the political risk (interviews 59108220, 60108220). These developments suggest a growing sense of responsibility and an interest in relatively more restrictive sales in response to reputational concerns.

In addition, the government has begun to engage with NGOs, noting that the NGO culture has transformed radically in recent years (interviews 59108220, 60108220). Indeed, the government’s receptiveness to parliamentary, public, and civil society input “is brand new, and not just an issue for weapons” (interview 64208220). NGOs agree that their relations with the government have improved in recent years and that they too are more competent in their arms export control advocacy (interviews 61208220, 62208220, 64208220). Nevertheless, they are still finding their way in relatively new territory. Government reports are frequently released too late to impact policy substantively (interview 61208220). Moreover, arms export control advocacy has often been an issue tacked on to existing organizations whose resources and main concerns are devoted elsewhere (interviews 62208220, 64208220). It is perhaps too early to tell, therefore, how well NGOs will really be able to affect French arms export practice.

Even so, existing levels of transparency have aided civil society’s transformation by giving NGOs information with which to criticize the government (interview 61208220). Yet accountability in France lags behind that in the other European cases. NGOs are still transforming from reactive to proactive, and although some past deals have been questioned, the government has yet to be critiqued on contemporary decisions. With claims that France had helped to arm Chad at the beginning of its February 2008 civil war (interview 61208220) and questions about arms exports in the context of the Arab Spring, opportunities have emerged for arms control advocates to assert their political perspective. If they do, it could have far-reaching consequences for French arms trade practices.

THE UNITED STATES: LOW SCANDAL SENSITIVITY

Despite high arms trade transparency since the late 1970s and a large-scale, global arms trade, the United States has suffered little domestic criticism of its arms transfer practices. As Susan Waltz observes, there is a distinct gap between its “principled policy” calling for restraint in arms transfers and its actions that “do not easily fit within the bounds of the policy that is publicly promoted and lauded” (2007:3, 4). Yet successive governments have remained relatively impervious to scandal. The cause, I argue, has to do primarily with the absence of a pro-control NGO community with an active voice in American politics.

The United States has a record of steady arms exports—small arms especially—to human rights violators and conflict zones in the Middle East, Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Asia. Reports of transfers to Indonesia, Sierra Leone, Nepal, Iraq, and others have had dire political consequences for governments elsewhere but have raised little commotion in the United States. As in France, this lack of notice is largely due to the absence of an active pro-control NGO community, which reinforces—and is reinforced by—the lack of public interest in the issue. As a result, arms exports maintain a low profile in the United States, and government scandal sensitivity remains minimal.

The Iran–Contra Affair of the 1980s might appear to be the one exception. It started as two separate scandals about covert U.S. arms transfers to Iran and Nicaragua. The first broke in October 1986, when Nicaraguan Sandinistas shot down a U.S. cargo plane and broadcast the existence of a U.S. military resupply chain for the Contras, which was seen as a clear violation of U.S. law and detrimental to the image of the U.S. government. With the Boland Amendments in 1982 and 1984, the Reagan administration had been legally prohibited from assisting the Contras through military aid.58 The second scandal broke a month later with reports in a Lebanese magazine, picked up by the U.S. press, of U.S. arms sales to Iran. Despite the U.S. arms embargo and Reagan’s policy of not negotiating with terrorists, it appeared as though the White House had traded arms for hostages. The president claimed that the sales had been intended primarily to normalize relations with Iran, not to release hostages (Walsh 1997:10). However, the shock the public felt at “the revelation that the administration had been saying one thing publicly and doing the opposite clandestinely” dragged the news into the media spotlight and formed the heart of the scandal (Draper 1991:470; Trager 1988).

But in late November 1986, the administration’s admission that the two scandals were in fact intimately related immediately overshadowed both (Cohen and Mitchell 1988; Walsh 1997).59 The larger scandal involved the diversion of funds from the arms sales to the Contras. Although the affair damaged Reagan’s domestic reputation, it did not lead to public backlash against U.S. arms sales. In fact, it had little if any perceptible effect on U.S. arms transfer policy or practice. Instead, it became preoccupied with questions of who knew about the diversion of funds and whether, as in Watergate, the corruption reached all the way up to the president (Draper 1991:497; Wroe 1991). Indeed, Iran–Contra coverage was so strongly shaped by Watergate and its focus on what the president knew and when that it left the arms sales issue on the sidelines (R. Busby 1999; Kornbluh and Byrne 1993; Trager 1988).

Although Americans conceded that laws had been broken and policies ignored, many supported the anti-Communist goals behind the arms sales. Oliver North—the scapegoat and hero of the affair—won over the public with his appearance of patriotic virtue during congressional hearings (Walsh 1997; Wroe 1991). He invoked reminders of “America’s own struggle in the War of Independence,” blamed Congress for not supporting the Nicaraguan “freedom fighters,” and painted the arms supplies as a necessary and just policy (qtd. in Wroe 1991:68; see also Walsh 1997). Like the French Luchaire Affair in a sense, defendants of the Reagan administration saw its policies and practices as broadly in line with and justified by U.S. interests and U.S. values.

In the end, Iran–Contra “was left as a scandal whose natural constitutional denouement—the fall of the man at the top—had never happened, and whose true nature would possibly never be known” (Wroe 1991:iv). Its focus on Reagan’s culpability, which it was unable to establish with any certainty, severely limited its consequences for arms trade policy—or for the national security apparatus in general (Koh 1990; Kornbluh and Byrne 1993). This was not a foregone conclusion: Reagan’s approval ratings crashed with revelations of his administration’s illicit activities, and many—including White House advisers and the media—thought the affair could topple his presidency (Thelen 1996; Walsh 1997). At the time, Iran–Contra was seen as damaging the president’s reputation, revealing his vulnerabilities, undermining his ability to lead, and possibly exposing him to impeachment.60

But answers to the question “What did the President know and when?” were elusive (Wroe 1991:iv; see also Cohen and Mitchell 1988; Kornbluh and Byrne 1993). Extensive document shredding and questions about Reagan’s memory prevented a resolution. Many doubted his ignorance: the issues were centerpieces of his policy agenda on which he received daily briefings, and “the diversion was no fringe detail” to keeping them alive (Walsh 1997:24; see also Kornbluh and Byrne 1993). However, as Harold Koh states, “The Iran–Contra committees’ inability to find a smoking gun damning the president effectively mooted the impeachment question, leading several members to act as if their inquiry were exhausted” (1990:19). The public, too, seemed to want the issue to drop. In the long run, Reagan remained personally popular, and no one wanted to deal with the aftermath of another Watergate (R. Busby 1999; Cohen and Mitchell 1988; Walsh 1997). It was only in 2011 that the 1991 reports by prosecutor Christian Mixter were made public, revealing that although Mixter had found that Reagan had been briefed on the weapons shipments, neither Reagan nor Vice President George H. W. Bush was criminally liable (Associated Press 2011).61

Iran–Contra was instead generally blamed on “bad people” not “bad laws” (Koh 1990:2). Admiral John Poindexter, deputy national-security adviser, and North, his aid, were fired and prosecuted (and then pardoned in 1992), but reforms were not forthcoming. Unlike other cases, scandal did not ignite fear of public reaction to other “deceitful” arms transfers.62 Indeed, Iran–Contra demonstrates that scandal does not guarantee governments’ sensitivity to future scandal, especially when its effects are dependent on assigning blame to a single leader. Scandal sensitivity is heightened when scandal encourages institutionalized policy reforms and the emergence of NGOs seeking to hold governments more accountable to its policy commitments. The pairing of transparency and organized civil society is at the core of enhancing the domestic threat of scandal. Lacking an active pro-control NGO community and evidence linking “irresponsible” exports to the top, U.S. administrations have been able to proceed largely without regard to public retribution when it comes to their arms transfer practices.

ANOTHER CASE OF U.S. EXCEPTIONALISM?

Aside from illustrating the lack of credible threat for scandal resulting from “irresponsible” export deals, the U.S. case also makes clear the need to distinguish between pro-control and pro-gun NGOs. The United States does in fact have a well-resourced, high-profile NGO community involved in the arms issue. However, these groups, in contrast to groups concerned about the issue elsewhere, are strongly opposed to multilateral export controls (see chapter 4). The NRA, “by far the largest and most influential of groups opposing gun-control legislation” (Finch 1983:26), represents the “active” contingent of the U.S. public on this issue. Its focus on civilian ownership rights makes it largely uninterested in export accountability. Instead, its work on the arms trade has focused on U.S. foreign policy and on rousing its constituents to stave off international standards it believes might undermine the Second Amendment, not raising public ire about U.S. export practices.63

It is not unusual for a country to lack active arms trade NGOs. What makes the U.S. case exceptional is its strong pro-gun NGO community with its active constituency, which has the ear of policy makers and has overwhelmed smaller pro-control groups64 from mobilizing a broader (and less interested) public. In contrast, European gun organizations consider themselves observers of and not participants in the political process. Although U.S. pro-control groups have lobbied Congress and the administration on some laws and export cases (interviews 48207002, 50207002, 51207002), they have insufficient means or will to generate the public interest needed to press for export accountability (interviews 48207002, 50207002). Congress, moreover, is “relatively uninformed about the impact of small arms proliferation and … tend[s] to be overly cautious and deferential to pro-gun perspectives and views” (Stohl and Hogendoorn 2010:38). During the George W. Bush administration especially, pro-control groups felt that the arms trade was an issue that was “not going to have a lot of successes” and placed it lower on their agendas as a result (interviews 48207002, 50207002, 51207002). Yet even under the Obama administration, pro-control NGOs have been slow to engage in advocacy at home, focusing their limited resources on shaping the U.S. role in UN processes. Moreover, the NRA has been active in communicating to Congress its opposition to those processes, pushing to prevent ATT ratification.

Iran–Contra has not been followed by other arms trade scandals, and decision makers have not been pushed to change arms export practice, which is seen as vital to support allies in the Middle East and Central Asia. In 2012, the Obama administration resumed deliveries to Bahrain after Congress briefly suspended a deal over Bahrain’s crackdown on protesters and American NGOs. Arms sales to Persian Gulf states have increased dramatically in recent years with otherwise little reaction from Congress or the public. As in the Cold War, the public has accepted arms exports justified by national-security arguments. In the long term, the consequences of low NGO activity may therefore reach further than case-by-case accountability. NGO campaigns can help shift public values and interest. As Rachel Stohl and E. J. Hogendoorn observe, “The connection between small arms and human suffering … has not been made successfully by the U.S. government or advocacy groups” (2010:38). The United States now supports “responsible” export controls. It remains to be seen if pro-control NGOs will hold it accountable to those commitments or if the hurdles set by the NRA and public disinterest are simply too high to overcome.

BELGIUM: TWO REGIONS, TWO TRADITIONS

Until 2003, Belgian arms export policy and practice were decided by the federal government. Early export reports, initiated amid emerging scandal in 1991, did not name individual recipients, making it difficult for NGOs to raise specific concerns. Transparency and export controls grew after the EU Code of Conduct was developed, activating NGO criticism of certain export deals. With export decision making regionalized in Belgium in 2003, scandal sensitivity now varies across the two major regions. Although both regions have some level of pro-control NGO activity, only Flanders has maintained a level of transparency with which those NGOs can wield information to spotlight government hypocrisy. In contrast, lower transparency in Wallonia leads to lower scandal sensitivity and the perception that government practice is less restricted.

Like many of its allies, Belgium was implicated in an Arms to Iraq scandal in the early 1990s. The 1990 murder of Canadian-born weapons engineer Gerald Bull in Brussels—his base for the Iraq “supergun” project65—brought Belgium firmly into the Arms to Iraq intrigue. In the process of investigating propellant manufacturer Poudrières réunies de Belgique’s (PRB) role in illegal sales to Iraq, former deputy prime minister André Cools uncovered connections between PRB, the Iraqi supergun project, and Bull.66 Cools was murdered in 1991, soon after receiving documents implicating Belgian civil servants in the affair. According to reports, civil servants had been bribed “to secure the use of Belgian air force freighters to ship cargoes of ‘supergun’ propellant to Iraq” and allowed defense goods destined for Iraq to pass through customs without proper authorization (Foster, Cleemput, and Lambert 1991).