6 Poverty, the environment and the market

Faith in economic growth as the key to progress comes into question as the earth’s life-support systems fray and signs of ecological collapse multiply. Globalization, geared to spur rapid growth through greater resource consumption, is straining the environment and widening gaps between rich and poor. The standard cure of orthodox market economics – privatization, tax cuts and foreign investment – is not effective. Criticism and concern grows from both expert insiders and grassroots communities.

Whether they are disciples of Keynes, confirmed free-marketeers or top-down central planners, economists of all stripes have an abiding faith in the healing powers of economic growth. Keynesians opt for government regulation and an active fiscal policy to kick-start growth in times of economic malaise. They believe the impact of state spending will catalyze the economy, create jobs and stimulate consumption. Keynesians (and the Left in general) have been concerned with making sure that the growing economic pie was distributed fairly. Socialists and some trade unionists have held out for more control over the production process by workers themselves.

Market fundamentalists, sometimes called ‘neo-liberals’, hope to boost consumption using different levers. They opt for ‘pure’ market solutions – tax cuts and low interest rates – both of which are supposed to increase spending and investment by putting more money into people’s pockets.

But, until recently, all sides have ignored the environment. The increasingly global economy is completely dependent on the larger economy of the planet. And evidence is all around us that the Earth’s ecological health is in severe trouble.

Our system of industrial production has chewed through massive quantities of non-renewable natural resources over the past two centuries. Not only are we wiping out ecosystems and habitats at an alarming rate, but it is also clear that we are exploiting our natural resource base (the economy’s ‘natural capital’) and generating waste at a rate which exceeds the capacity of the natural world to regenerate and heal itself.

We don’t have to look far for proof that growth-centered economics is pushing the regenerative capacities of the planet’s ecosystems to the brink. There is concern that the supply of oil – the most essential non-renewable resource for the industrialized economy – has already peaked, despite the recent uptick in global supply. The world oil market is subject to booms and busts. But in the long term petroleum is a finite resource. The rate of new discovery has been dwindling for decades.

With other raw materials it is a slightly different story: there is no immediate shortage. Even at current rates of consumption there is enough copper, iron and nickel to last centuries. More pressing is the cumulative impact of relentless resource extraction on the basic life-support systems that we take for granted. The water cycle, the composition of the atmosphere, the assimilation of waste and recycling of nutrients, the pollination of crops, and the delicate interplay of species: all these are threatened.

There is now a large body of research documenting this precipitous decline. Deserts are spreading, forests are hacked down, fertile soils are ruined by erosion and desalination, fisheries are exhausted, species pushed to extinction and groundwater reserves pumped dry. Carbon-dioxide levels in the atmosphere continue to rise due to our extravagant burning of fossil fuels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – 2,500 of the world’s top climate scientists – says that climate change will lead to ‘widespread economic, social and environmental dislocation over the next century’. Climate-change skeptics may scoff but the scientific consensus is clear. In November 2014 the IPCC released its review of more than 30,000 climate change studies, concluding that emissions from fossil fuels will need to drop to zero by the end of the century to avoid ‘irreversible’ and damaging impacts on people and the environment.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) stresses that the global extinction crisis is accelerating, with dramatic declines in the populations of many species, including reptiles and primates. The Swiss-based NGO sees habitat loss, human exploitation and invasion by alien species as major threats to wildlife. The loss of habitat is affecting 89 per cent of all threatened birds, 83 per cent of threatened mammals and 91 per cent of threatened plants. The highest number of threatened mammals and birds are found in lowland and mountain tropical rain forests: 900 bird species and 55 per cent of all mammals.

The IUCN concludes we are losing species faster than any time in history – 1,000 to 10,000 times more quickly than the natural rate of extinction that occurs through evolution. Between a third and a half of terrestrial species are expected to die out over the next two centuries if current trends continue unchecked. Scientists reckon the normal extinction rate is one species every four years.1

From 1950 to 2014, global economic output jumped from $4.0 trillion to nearly $77.6 trillion – an increase of nearly 2,000 per cent. We have consumed more of the world’s natural capital in this brief period than during the entire history of humankind.

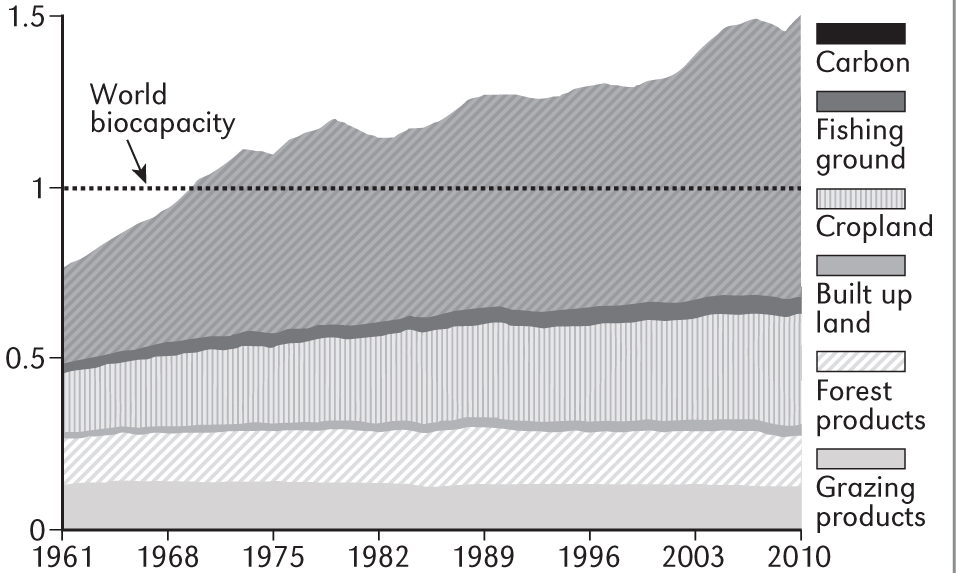

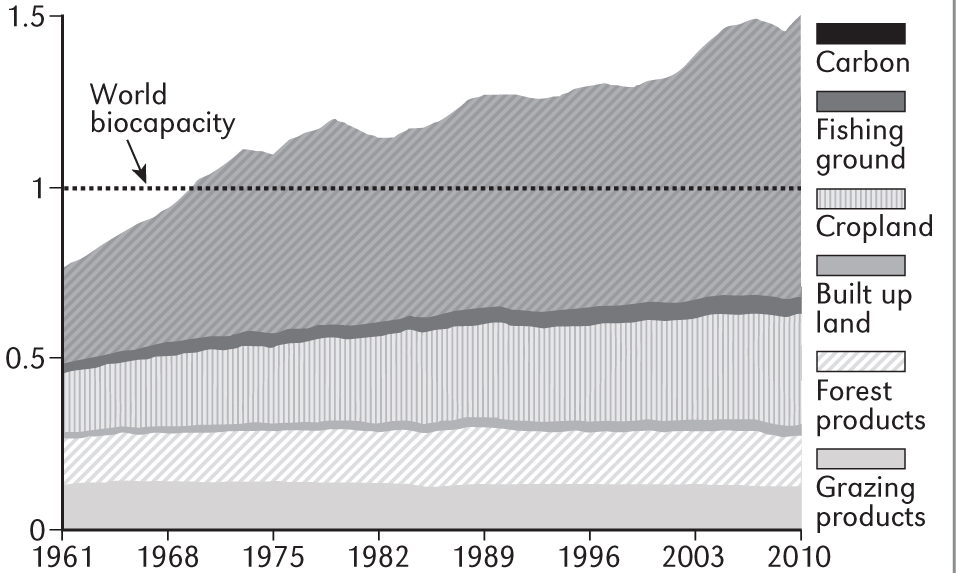

Ecological footprints

The ecologists William Rees and Mathis Wackernagel pioneered the ‘ecological footprint’ concept, which attempts to put a number on the amount of ecological space occupied by people and by nations. They estimate that around 4-6 hectares of land are used to maintain the consumption of the average person in the West. However, the total available productive land in the world is about 1.7 hectares per person (total land divided by population). The difference between the two is what they call ‘appropriated carrying capacity’ – which basically means the rich are living off the resources of the poor.

The Netherlands, for example, consumes the output of a productive land mass 14 times its size. Most Northern countries and many urban regions in the South already consume more than their fair share; they depend on trade (using someone else’s natural assets) or on depleting their own natural capital. According to Rees and Wackernagel, the global footprint now exceeds global biocapacity by 20 per cent and that gap is growing yearly. The US alone, with 4.5 per cent of the world’s population, sucks up 25 per cent of the earth’s biocapacity. The average Indian has an ecological footprint of just 0.8 hectares while the average American has an ecological footprint of 9.7 hectares.2

Regions like North America and western Europe, argue Rees and Wackernagel, ‘run an unaccounted ecological deficit – their population either appropriating carrying capacity from elsewhere or from future generations’.3

Faith in economic growth as the ultimate hope for human progress is widespread. A central tenet of economists on both left and right has been that the ‘carrying capacity’ of the Earth is infinitely expandable. The underlying belief is that a combination of ingenuity and technology will eventually allow us all to live like middle-class Americans – if we can only ignore the naysayers and keep the economy growing.

But endless, exponential growth is impossible in a world of finite resources and ecological limits. As the Worldwatch Institute points out: ‘Rising demand for energy, food and raw materials by 2.5 billion Chinese and Indians is already having ripple effects worldwide…If China and India were to consume resources and produce pollution at the current US per-capita level, it would require two planet Earths just to sustain their two economies.’2

Says ecologist Robert Ayres: ‘There is every indication that human economic activity, supported by perverse trade and growth policies, is well on the way to perturbing our natural environment more and faster than any known event in planetary history.’4

Ayres is on to something when he accuses the ‘perverse’ aspects of globalization of accelerating the process of environmental decline. Export-led growth and developing-world debt have combined to speed up the rapid consumption of the Earth’s irreplaceable natural resources. Some environmentalists argue that primary resources (nature’s goods and services) are too cheap and that their market price does not reflect either their finite nature or the hidden social and ecological costs of extraction. Instead, they suggest, we should conserve the resources we have by making them more expensive. There is some truth to this analysis. The price of raw materials is notoriously unpredictable, based not just on supply and demand but also on the monopoly power of corporations that control distribution and sales. In general, when the global economy booms, overall demand goes up. When the economy crashes, as it did in 2008, demand falls. In recent years, the price of industrial metals like nickel, copper and iron has risen (or fallen) in tandem with the Chinese economy, the engine of global production at the moment. World market prices for commodities like cotton, sugar and coffee also gyrate unpredictably. Prior to the 2008 global meltdown, world energy prices nearly tripled and commodity prices across the board rose sharply, including the prices of staples like corn and rice.

This instability has been compounded in recent years by the ‘financialization’ of commodity trading, the latest twist of the ‘casino economy’ (see Chapter 5). Big banks, hedge funds and money managers scour the globe for opportunities to invest surplus capital to reap the biggest returns in the shortest time. The lessons of the 2008 crash, it seems, have yet to be learned. Short-term financial flows continue to unsettle the world economy. In the year 2000, commodity assets controlled by finance capital amounted to $10 billion; by 2012 that figure had topped $439 billion. UNCTAD notes that short-term investors twist commodity markets so that ‘prices are detached from supply and demand’. This leads to ‘high volatility and distorted prices’ – generating tidy profits for speculators but financial insecurity for farmers, miners and nations whose income depends on these markets.5

The world’s demand is outstripping the earth’s biocapacity so we are beginning to consume irreplaceable natural capital. The average ecological footprint worldwide is 2.6 hectares while the average biocapacity available per person is 1.7 hectares. Humanity’s footprint now exceeds the planet‘s regenerative capacity by 50%. Our footprint has more than doubled since 1961.

Ecological footprint (number of planet Earths)

(Source: Living Planet Report 2014, globalfootprintnetwork.org)

But debt in developing countries, the source of many of the world’s commodities, has also kept prices low. Centuries of colonialism put in place a system of extreme dependency on a narrow range of exports which remains to this day. According to UNCTAD, just three commodities account for 75 per cent of total exports in each of the 48 poorest nations. This might be tolerable if nations like Honduras, Kenya and Zambia earned a decent income from their sugar, tea and copper. Sadly, the opposite is true. Due to plunging ‘terms of trade’, commodity-dependent nations need to export more just to stay in the same place. Even when times are good, things are bad. Take the 2002-12 ‘commodity supercycle’ when the world’s voracious appetite for raw materials and new energy resources drove up commodity prices. Export income increased. But so did dependency. UNCTAD notes that 57 per cent of developing countries now depend on resources for at least 60 per cent of their export earnings.5 The UN agency’s figures show a long-running deterioration in the prices of primary commodities vis-à-vis manufactures.

A mountain of debt doesn’t help. The price of admission to the global trading community means that poor countries are obliged to service their debts before they are allowed to do anything else. They are urged to expand commodity exports to world markets by hook or by crook. Unfortunately, removing the barriers to exports isn’t always the answer. In fact, it can make matters worse, especially for small farmers. When they grow more for export, it often leads, perversely, to overproduction and lower prices. Faced with less income, farmers respond rationally by increasing their production, ensuring that prices remain low. Countries in hock have been forced by World Bank and IMF structural adjustment edicts to ratchet up exports to service their debts. The new term circulating among critical economists to describe the phenomenon is ‘immiserating trade’. The more you trade, the poorer you get.6

How boosting exports can backfire

Globalization’s default position is market efficiency. But this often plays into the hands of those who can ‘game’ the system. If all poor countries have to increase their exports at once, there is a glut and prices fall – sometimes by half. Twice as much has to be exported to earn the same amount of foreign currency. The winners are the developed countries and Western-based corporations. They not only get their debts serviced, but they also benefit from cheap resources which helps keep prices down, profits up and inflation under control in the North. The losers are the people of the South (especially those without oil) and the global environment.

Globalization puts the squeeze on the environment by turbo-charging the extractive industries. Take Brazil, which environmentalists consider one of the earth’s most ecologically important nations. The country still contains 30 per cent of the planet’s rainforest; the sprawling Amazon region has long been considered ‘the lungs of the world’. Scientists believe the spectacular biological diversity of the rainforest is a potential cornucopia of priceless, life-saving drugs.

In 1999, the Brazilian government slashed millions of dollars off environmental spending in the wake of IMF-enforced cuts. The country’s environmental enforcement arm had its budget pared by 19 per cent. The Fund’s policies then sparked a domestic recession that boosted unemployment, forcing many ordinary workers and peasants to clear larger areas of jungle for subsistence.

Encouraging primary exports can also strengthen the hand of agribusiness and large landowners. Peasant farmers and smallholders are squeezed out by the implacable logic of economic efficiency. In Brazil, the amount of land devoted to large-scale soy production has jumped from 0.2 million hectares to more than 58 million hectares over the past 35 years, much of it virgin rainforest. In 2014, the country harvested 90 million tons of soybeans, replacing the US as the leading soy-producing nation. The growth of the country’s beef industry has caused even more environmental destruction in the Amazon. Deforestation rates have dropped dramatically since 2004 when 27,000 square kilometers of rainforest was burned, the second highest rate on record, but still, over the past 40 years, about a fifth of Brazil’s jungle has been razed. The vast nation is now the world’s biggest beef exporter but the industry’s continued expansion threatens 40 per cent of the world’s remaining rainforest.7 In 2013, nearly 6,000 square kilometers of rainforest was cleared. About three-quarters of Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions come from torching the jungle and the country is now the world’s sixth-largest carbon-dioxide polluter.8

Dr Gustavo Fonseca of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais in Brazil sums up the concern of environmentalists: ‘Our biggest worry now is that the government is going to lose control of attempts to control deforestation. This is undermining the very basis of what we’ve been trying to accomplish in Brazil.’9

The pattern is repeated in neighboring Argentina, where the area planted with soy has tripled in the last decade. Argentina became the first Latin American nation to allow genetically modified soy in 1996. The versatile legume now covers half the country’s cultivated land and Argentina is the world’s number one exporter of soy, supplying 45 per cent of the world market. The country’s 2007 ‘Forest Law’ prohibits clearing forest to plant soy. Yet, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), native forests are disappearing at the rate of 240,000 hectares a year. Since 1990, Argentina’s forest cover has shrunk by 10 per cent.

Asia’s ‘economic miracle’ has also been built on a fast-track liquidation of its natural resources. In Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, the Philippines and elsewhere, pristine rainforests have been razed, rivers fouled, coastal areas poisoned with pesticides and fisheries exhausted. In the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, more than 70 per cent of water samples were found to be ‘highly contaminated by chemical pollutants’ while the country’s forests were being hacked down at the rate of 2.4 million hectares per year. In the Malaysian state of Sarawak (part of the island of Borneo) 30 per cent of the forest disappeared in a mere two decades, while in peninsular Malaysia 73 per cent of 116 rivers surveyed by authorities were found to be either ‘biologically dead’ or ‘dying’.10

The environmental group Friends of the Earth (FoE) summarized the impact of free-market deregulation on Third World environments in its 1999 study, IMF: Selling the Environment Short. FoE examined IMF policies in eight countries, including Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Guyana, Nicaragua and Thailand, and found significant negative environmental impacts in all of them.

Several countries slashed government spending after being pressured by the Fund to eliminate budget deficits. The report also noted that IMF policies encourage, and sometimes induce, countries to exploit natural resources at unsustainable rates. According to Carol Welch, co-author of the report: ‘Every case shows that the IMF pushes short-term profit at the expense of biodiversity and ecological prosperity…the IMF is undermining people’s lives by disregarding environmental issues.’11

Persistent poverty has also spurred environmental decline – the poor do not make good eco-citizens. Animals are poached and slaughtered by desperate African villagers for their valuable ivory, their body parts or simply for ‘bush meat’.

Madagascar, the huge island nation off the coast of Mozambique, was once covered in lush forests. It has turned into a barren wasteland as people slash and burn jungle plots to grow food. Soil erosion is so serious that the sea around the island sometimes appears blood red from the iron-tinged run-off. The Indian Ocean nation is home to some 200,000 plant and animal species – three-quarters of which are found nowhere else. Less than a tenth of Madagascar is still tree-covered and the forest is vanishing at the rate of 200,000 hectares a year. Illegal logging of costly tropical hardwoods like rosewood and ebony is rampant. One 150-kilogram log of rosewood can fetch as much as $1,300. Poverty is the core of the problem: 70 per cent of the island’s 14 million people live on less than a dollar a day. So five dollars a day to work as a logger in the jungle is a lifesaver for impoverished peasants.12

‘Our village has been burning forests to plant rice here for generations,’ Dimanche Dimasy, chief elder of Mahatsara village, told the BBC. ‘This is our way of life. If we can’t cut the forests, we can’t feed ourselves. The government wants to protect the forests but nobody cares about protecting the peasants who live here.’13

Taking to the streets in protest

The gospel of globalization is seductive because it is based on a simple principle: free the market of constraints and its creative power will bring employment, wealth and prosperity. But not everyone shares the same faith.

The signs are inescapable – not least of which are the thousands of civil-society groups around the world that have taken their case to the streets. It began in Seattle in November 1999 when more than 50,000 people from dozens of countries demonstrated at the annual meeting of the World Trade Organization. The gathering was a unique mix of environmentalists, trade unionists, peasant organizations, students and ordinary citizens – all united by their concern that economic globalization is spinning out of control. The protest gained worldwide prominence when police in riot gear charged the crowds, firing pepper spray, teargas and plastic bullets. Some 500 people were arrested and a state of emergency was declared.

Then, at the Washington meetings of the IMF and World Bank in April 2000, another 15,000 people gathered for a repeat protest. Ironically, as if to underline the demonstrators’ concerns, stock markets nosedived the same week, as a wave of panic selling swept the globe, puncturing the high-tech stock bubble that had carried markets to dizzying new heights through the 1990s. After Seattle, civil-society demonstrations became a regular occurrence at meetings of the IMF/World Bank, the G8 and the expanded G20 – Prague in October 2000, Quebec City in April 2001, Miami in November 2003, Scotland in July 2005, Italy in July 2009, Toronto in June 2010, and Brisbane in November 2014. Wherever these political elites meet, they now run into a similar phalanx of protesters.

Even among mainstream economists globalization is coming under increasing scrutiny. The financial crises in Russia, Asia and Latin America in the late 1990s proved to be a warm-up for the spectacular global crash of 2008. Together these mishaps opened a deep rift in the dominant ‘Washington Consensus’ – a view that had been promoted by the Bretton Woods institutions and adopted by most Western governments. After 2008, powerful supporters of free trade and open markets began to reconsider their position.

The influential economist Jeffrey Sachs was one of those. Now director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University and special advisor to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, Sachs was an IMF advisor and one of the main engineers of capitalist ‘shock therapy’ in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union. The Asian financial crisis forced him to re-examine his faith in the supremacy of deregulated markets and to question the conventional solutions to national financial crises – especially the role of the IMF. In a candid Financial Times article published in December 1997, Sachs called the IMF ‘secretive’ and ‘unaccountable’. ‘It defies logic,’ he continued, that ‘a small group of 1,000 economists on 19th Street in Washington should dictate the economic conditions of life to 75 developing countries with around 1.4 billion people.’

Others began to speak out too. The World Bank’s former chief economist, Joseph Stiglitz, became a much-quoted ‘ex-insider’ willing to criticize publicly the dangerous policies of market fundamentalists.

Globalization and its Discontents, his scathing 2002 critique of the Bretton Woods institutions, became a bestseller, studded with personal anecdotes and case studies.

‘The net effect of the policies set by the Washington consensus,’ he wrote, ‘has all too often been to benefit the few at the expense of the many, the well-off at the expense of the poor. In many cases commercial interests and values have superseded concern for the environment, democracy, human rights, and social justice.’14

Stiglitz continues to hammer away at the lunacy of deregulated markets. In September 2014 he wrote in Britain’s Guardian newspaper: ‘What we have been observing – wage stagnation and rising inequality, even as wealth increases – does not reflect the workings of a normal market economy, but of what I call ersatz capitalism. The problem may not be with how markets should or do work, but with our political system, which has failed to ensure that markets are competitive, and has designed rules that sustain distorted markets in which corporations and the rich can (and unfortunately do) exploit everyone else.’15

The influential financial journalist Martin Wolf was another globalization propagandist who changed his mind in the light of the global crash. His 2004 book, Why Globalization Works, was a song of praise to unrestricted markets. Ten years later, in Shifts and Shocks, he recants his earlier enthusiasm, admitting that ‘the interaction between liberalism and globalization has destabilized the financial system…To pretend one can return to the intellectual and policy-making status quo is profoundly mistaken.’16

Despite the spectacular economic growth of the past half-century, the quality of life for a fifth of the world’s population has actually regressed in relative, and sometimes absolute, terms. One of the most cogent critiques of globalization comes from the UN Development Programme. Its yearly Human Development Report is a first-rate compilation of insightful data and probing analysis. The prose may be stiff but it gets to the point. ‘When the market goes too far in dominating social and political outcomes, the opportunities and rewards of globalization spread unequally and inequitably – concentrating power and wealth in a select group of people, nations and corporations, marginalizing the others.’17

The UN agency supports its analysis with telling data on what it calls a ‘grotesque and dangerous polarization’ between those people and countries benefiting from the system and those that are merely ‘passive recipients’ of its effects.

Globalization is a false god for the majority of the world’s citizens. As Stiglitz points out: ‘Despite repeated promises of poverty reduction made over the last decade of the 20th century, the actual number of people living in poverty has actually increased by 100 million.’14

Spiralling inequality

The divide is becoming so extreme that more astute members of the business community are beginning to worry. The Global Wealth Report 2014 from the giant financial services company, Credit Suisse, found that the richest one per cent of the world’s population owned 48 per cent of global wealth while the bottom half owned less than one per cent. The world’s 500 richest people are a cosmopolitan bunch – they hail from Mexico, Russia, India, China, Britain, the US and elsewhere. And, according to UNDP, they now have a combined income greater than the poorest 416 million of their fellow global citizens.

The OECD, too, has pointed to the enormous increase in income inequality as ‘one of the most significant – and worrying – features of the development of the world economy in the past 200 years.’18 In 2014, the agency noted that the income of the top 10 per cent of the population in OECD member states is 9.5 times that of the bottom 10 per cent – an increase of more than 30 per cent in 25 years. ‘And worryingly for our future,’ stressed the OECD’s secretary-general, José Ángel Gurría, ‘youth have now replaced the elderly as the group experiencing the greatest risk of income poverty.’

The change in income inequality in the rest of the world is checkered, increasing in some countries and decreasing in others. In the most populated developing countries – India, China and Indonesia – equality rose from 1994 to 2013. In most of Latin America, parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, equality declined slightly. The big success story is Brazil, where inequality fell dramatically as a result of targeted anti-poverty policies. Nonetheless, the wealth gap in Brazil is still amongst the highest in the world. And as UNDP points out: ‘the majority of the world’s population is still living in countries with stable or increasing inequality, because, in populous countries like India and China, inequality is rising.’ China had 250,000 dollar-millionaires in 2005; they made up less than 0.4 per cent of the country’s population but held 70 per cent of the country’s wealth.19

The growing gap can mean the difference between life and death: children born into the poorest 20 per cent of households in Ghana or Senegal are two to three times more likely to die before the age of five than children born into the richest 20 per cent of households.20 The same holds true in rich countries. A 2014 Statistics Canada study found that income inequality is associated with the premature deaths of 40,000 Canadians a year. Poor males have a 63-per-cent greater chance of dying from heart disease than their wealthy counterparts while poor women have a 160-per-cent greater chance of dying from diabetes.21

Wealth is highly concentrated in the hands of relatively few rich people and they’re getting richer. In many Western countries the middle class is shrinking and people are actually earning less in real terms (adjusted for inflation) than they were in the 1970s. In Britain, for example, the wealthiest 1 per cent owns the same amount as the bottom 55 per cent and there were 104 billionaires in 2014 – more than triple the number of a decade ago. (London has more billionaires – 72 – than any other city in the world.)

Another UN study concluded that in the 1980s real wages (adjusted for inflation) had fallen and income inequality increased in all OECD countries except Germany and Italy.

In the US, the top one per cent boosted their wealth from 25 per cent of the total in 1973 to 40 per cent in 2014. But the top 0.1 per cent gained even more: in 2013 the top 25 hedge fund managers in the US pocketed, on average, $1 billion each.22

This shift in wealth and income from bottom to top is part of the logic of globalization. In order to be ‘competitive’, governments adopt policies which cut taxes and favor profits over wages. The economic argument is simple: putting more money into the pockets of corporations and wealthy individuals (who benefit most from tax cuts: the higher the income, the greater the gain) is supposed to lead to greater investment, jobs, economic growth and prosperity. Both corporate and individual tax rates have dropped across the industrialized world over the past 35 years. In the US, the top marginal tax rate on wealthy individuals averaged 82 per cent from 1947 to 1974. Then, under President Reagan, the rate was slashed to 28 per cent; in recent years it has hovered around 35 per cent. The UK has followed suit. The Tory/LibDem coalition government of 2010-15 reduced the top rate of tax to 45 per cent while cutting benefits to the poor. Other countries have been less generous to the rich. The top tax rate in Switzerland and Germany has been stable for 50 years and the top one per cent actually take slightly less of total income than they did in the 1960s.23

Unfortunately, there is no evidence that the public is better off as a result of tax cuts for the rich. If the reverse were true, and tax cuts were directed towards people at the bottom of the income ladder, it could make a difference. The money would almost certainly be spent on basic necessities rather than luxury goods. But this isn’t part of the globalization game plan. To sum up: in every country that has taken up the ‘reduce-taxes-cut-the-deficit’ mantra, tax cuts mostly benefit wealthy individuals and corporations. What happens to the extra cash is predictable: some goes into high-priced consumer baubles – a phenomenon which is glaringly visible amongst the elite in cities from Bangkok to Los Angeles. The rest winds up in the stock market, in pricey real estate or in other sorts of non-productive speculation.

Major players are no longer satisfied with modest profits on long-term investment, especially when double-digit returns are available from currency speculation or financial derivatives. This diversion of capital away from socially useful investment fuels the ‘casino economy’. That and the fact that investment opportunities in the goods-producing sector are shrinking due to the problem of ‘over-capacity’ – too many goods chasing too few buyers (see Chapter 5). Computerized robots and automated assembly lines replace workers with new technology, leaving fewer people who can buy the products that factories are churning out. Those that remain find their wages under constant downward pressure in the face of cheaper labor elsewhere. The drive to be competitive ends up being a ‘race to the bottom’. Workers who don’t lose their jobs find their wages squeezed.

Since the 1980s wages have risen less quickly than productivity, which means that workers are receiving a shrinking share of economic growth. According to the ILO, average real pay in developed economies rose just 0.1 per cent in 2012 and 0.2 per cent in 2013. Workers in Italy, Japan and the UK were earning less than in 2007. Wages used to make up 70 per cent of GDP in the US; that number is now closer to 64 per cent. The same trend is evident even in Scandinavia, according to the OECD. In Norway, labor’s share tumbled from 64 per cent in 1980 to 55 per cent in 2013. In Sweden the drop was from 74 per cent to 65 per cent. A decline has also occurred in many developing countries, notably China and Mexico. As the business magazine, The Economist, notes: ‘The scale and breadth of this squeeze are striking. And the consequences are ugly. Since capital tends to be owned by richer households, a rising share of national income going to capital worsens inequality. In countries where the gap in wages between high earners and the rest has also increased, the two effects compound each other.’24

Despite decades of increasing per-capita income, and phenomenal growth in China and India, poverty is still an urgent global problem.

• The richest 10% of the world’s population receive 42% of world income while the poorest 10% receive just 1%.

• 1.2 billion people live on less than $1.25 a day while 2.7 billion – about 37% of the world’s population – live on less than $2.50 a day.

• The world’s richest 80 people own the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of the world’s population, 3.5 billion people.

• In 2010, high-income countries with 16% of the world’s population took home 55% of total income. Low-income countries with 72% per cent of global population earned just 1%.

• The per-capita income gap between high income and low income countries increased from $18,525 in 1980 to $32,900 in 2007, before falling to $32,000 in 2010. Per capita incomes between low and middle income countries more than doubled from around $3,000 in 1980 to $7,600 in 2010.

Sources: UNDP, World Bank, Oxfam International, UNICEF. Current Fx, Money of the Day, Forbes.

Despite these worrying warning signs, staunch free marketeers are reluctant to abandon their beliefs: ‘Give the private sector the resources,’ they say, ‘it will do the job.’ But the proof is elusive. Surplus capital that doesn’t get funnelled into the currency markets zips straight into overseas tax havens, where both rich individuals and globe-trotting transnationals have been squirrelling away their cash for decades.

The tyranny of tax havens and the super-rich

There are nearly 70 tax havens scattered around the world. These ‘offshore financial centers’ include places like the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Monaco, Luxembourg and Bermuda. Investors can store their wealth secretly, no questions asked – thus escaping any social obligations to the country where they may have earned it. Only a small number of these tax havens have public disclosure laws affecting the banks which operate within their borders.

A mere fraction of the global population actually lives in tax havens. Yet these enclaves produce about three per cent of world GDP, account for 26 per cent of global financial assets and more than 30 per cent of the profits of US transnationals. This final figure gives a clear sense of how important tax havens are to the corporate world – and why they need to be closed. But it also underlines the flawed reasoning of those who support economic policies premised on tax cuts and corporate deregulation. In almost all cases, corporations will do whatever they can to avoid paying taxes in order to maximize returns on the investment of their stockholders. That’s the way the system works. They jeopardize their own survival to the extent that they are unable to reach that goal.

Labor cost as % of nominal GDP

The tension between the corporate goal of avoiding taxes and the broader public interest is one reason why tax havens are now coming under intense scrutiny. Both OECD and EU members have long recognized these refuges as a drain on national treasuries and a convenient way of ‘laundering’ illegal funds. For example, the disgraced US energy trading company, Enron, is said to have used 800 different ‘financial dumps’ in the Caribbean to hide its debts. And it is estimated that up to $500 billion from the global narcotics trade passes through tax havens annually. According to the advocacy group, Canadians for Tax Fairness, Canadians had $170 billion invested in the top 10 tax havens at the end of 2013, up 10 per cent from the previous year and a whopping 188-per-cent jump since 2005. The fear is that digital commerce, combined with lax controls on the free movement of capital, will trigger an even greater flow of wealth and profits to these tax-free enclaves.25

The wealth of the super-rich balloons even as the social fabric that forms the backdrop to our lives continues to fray. This is the hidden human cost of ‘market discipline’ and it is as much a dilemma for social democracies in Europe as it is for politically fragile countries in Africa or Latin America.

In the industrialized nations we can chronicle the gradual decline in public services and social provision that has accompanied attempts to reduce government deficits. This cut-back on public spending is demanded by international markets – by the same investors that demand high rates of return on their investment and low rates of taxation. As corporate profits boom and real wages stagnate, the glue that holds us together is losing its bond. Government revenues are directed to paying down debt or cutting taxes while citizens are told there is no longer enough money to pay for ‘public goods’. Middle-class taxpayers may even receive a few hundred dollars in tax savings. But there is a price to be paid. Investment in public infrastructure dwindles and our ‘commonwealth’ is diminished – there is less money for public education, budgets for parks and recreation are slashed, public transport and state-funded healthcare are underfunded.

In the Western nations, education and healthcare systems have seen repeated budget cuts as the state retreats and makes way for private, profit-oriented ventures. Welfare and unemployment benefits have been ‘rationalized’, slashing the number of those eligible. Fees for college and university have skyrocketed. In the US, for example, tuition rates have jumped by more than 1,000 per cent since the 1970s and student debt is now approaching $1.2 trillion. (State funding of universities declined by about 40 per cent during that period.)

Meanwhile, senior citizens and those nearing retirement are fearful that promised pensions will evaporate as governments become more desperate for funds. Individuals are frantically scraping together their savings, told by business-friendly politicians that they should look to the stock market as the ticket to old-age security. Tapping into the politics of resentment, some governments are attempting to claw back the hard-won gains of public-sector workers in an attempt to bring everyone down to the same low level of pensions or benefits. Government funding for the arts and for environmental protection has also been steadily eroded. The failure to protect these ‘public goods’ diminishes us all, makes us less capable of caring for each other and prohibits us from advancing together as a cohesive, mutually supportive community.

How globalization can derail development

Globalization has also derailed development in the Global South, where the poor continue to pay the highest price of adjustment. To boost exports and maintain their obligations to creditors, developing countries divert money away from social spending and infrastructure. There have been countless studies detailing the social impact of economic globalization and the results are depressingly similar. In most of the world’s poorest countries, poverty reduction stalled between 1995 and 2005 as they fell further behind richer nations. The most recent global recession will only worsen this trend.

As the Ebola virus raged through West Africa in 2014 a report from three leading British universities concluded that IMF policies favoring international debt repayment over social spending weakened healthcare in the three worst-hit countries. Researchers in The Lancet charged that harsh loan conditions imposed on Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea led to ‘underfunded, insufficiently staffed, and poorly prepared health systems’ – a key reason the disease spread so rapidly.26

The Indian government launched its campaign to liberalize the economy and open up to foreign investors in 1992. Nearly 25 years later, the giant nation has been transformed. Transnational brands are ubiquitous while sleek German and Japanese cars jostle bullock carts in the streets of Mumbai and Bangalore. High-tech exports are booming, growing at a rate of 12-14 per cent a year. The value of those exports hit $85 billion in 2014. Meanwhile, the country is graduating millions of skilled professionals and foreign capital is pouring in. Microsoft, Intel and Cisco have all announced investments of billions. Rapid growth from 2002-12 lifted tens of millions of Indians from poverty into a middle class that now approaches 300 million in a population of 1.3 billion.

Nonetheless, disparities within the country are widening. Many Indian citizens have seen their living standards fall or stagnate since embracing globalization. India is home to a third of the world’s poorest people. A recent study by the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that 56 per cent of Indians, around 680 million, lack the means to meet their basic needs. Most of those are in the rural areas. Another 413 million are considered vulnerable. ‘They have only a tenuous grip on a better standard of living, and shocks such as illness or a lost job can easily push them back into desperate circumstances,’ the report notes.27 Malnutrition affects nearly half the country’s children and 10 per cent of all boys and a quarter of all girls don’t attend primary school, while the death rate for girls age 1-5 is 50 per cent greater than for boys.

Demonstrations continue to erupt across the country as Indians worry about cheap food imports wiping out local farmers. Two influential coalitions uniting hundreds of grassroots organizations are spearheading the protests. The National Alliance of People’s Movements is made up of more than 200 citizens’ groups and was formed in 1992. The Joint Action Forum of Indian People (JAFIP) against globalization brought together more than 50 farmers’ and peasant groups in 1998 to demand that India withdraw from the WTO.

The litany of suffering and damage spawned by harsh market reforms is repeated across the developing world.

A massive study involving hundreds of civil-society groups across eight countries confirms this judgment. The Structural Adjustment Participatory Review Initiative (SAPRI) held hearings from Bangladesh to El Salvador gathering grassroots information over a four-year period, originally with the participation of ex-World Bank President James Wolfensohn. However, the Bank backed out of the process when it realized what would appear in the final report. No wonder. Eventually released in 2001, at the tail end of the Bank’s structural-adjustment binge, the SAPRI review confirmed what Northern NGOs and ordinary people in the South had been saying for years: ‘Adjustment policies contributed to further impoverishment and marginalization of local populations while increasing economic inequality.’28

In Hungary, the IMF advised introducing liberalized trade, a tight money supply and rapid privatization of state assets. But the report found the policies deflected money away from education and social services and into the wallets of wealthy bond holders.

In Senegal, which had endured 20 years of IMF programs, the report found ‘declining quality in education and health’ combined with a growth in ‘maternal mortality, unemployment and child labor’. In Tanzania, globalization had successfully redirected agriculture towards exports but had also ‘expanded rural poverty, income inequality and environmental degradation’. Food security decreased, housing conditions deteriorated and primary-school enrolment dropped, while malnutrition and infant mortality rose.

Meanwhile, millions of Mexican farmers were pushed out of agriculture and thousands of small businesses went bankrupt after the country signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Thanks to NAFTA, the US was able to dump highly subsidized, cheap maize into Mexico, driving local farmers out of business. In 1990, Mexico was self-sufficient in maize, a crop with deep cultural significance for the Mexican people. Today it’s the world’s third-largest importer. Two decades after NAFTA, poverty, rural unemployment and overall inequality have increased. The country’s economic growth has stalled, averaging less than one per cent since 2000. And Mexico’s poverty rate has not budged: at 52 per cent it is identical to 1994. Things would have been much worse if thousands of Mexicans hadn’t migrated north in desperation, looking for work.

In all countries touched by economic globalization, women tend to bear a disproportionate share of the costs. One feminist critique of structural adjustment documented many ways in which women become ‘shock absorbers’ for economic reforms. These include: forcing more women into informal-sector jobs as mainstream opportunities fade; promoting export crops which men tend to dominate; disrupting girls’ education; increasing mortality rates and worsening female health; more domestic violence and stress; and an overall increase in the workload of women both inside and outside the home.29

Since women are the caregivers in most societies, they tend to pick up the pieces when the social safety net is slashed. A 1997 Zimbabwe study found that 15 years of economic reform had a devastating impact on women in that southern African country. When school fees were raised, girls dropped out first. And when health spending was cut by a third, the number of women dying in childbirth doubled. As male breadwinners are laid off, women do what they can to compensate for the lost income. They brew beer, turn to prostitution or become street traders. It inevitably falls on women to pick up the slack when governments cut education, healthcare and other social programs. In Western countries, too, women bear the brunt of austerity-led spending cuts. After the 2008 recession the US state of Washington cut $10 billion from its budget. Over half the job cuts were in education, health, and social services where women made up 72 per cent of the labour force.30

Are the social and environmental costs of economic growth too great? As the victims of globalization multiply, growing legions of ordinary people are beginning to question a process over which they have no control and little say. It’s easy to be a cheerleader for globalization if you’re on the winning side. But not so easy if your job has been outsourced to Mexico or China, or your coffee crop no longer brings in enough cash to feed and clothe your family. As the grip of the global economy tightens, millions of ordinary people around the world have begun to speak out forcefully against a system which they see as both harmful and unjust.

Instead of a homogenized global culture shaped by the narrow demands of the ‘money economy’, there is a resurgent push for equity and sustainability. Instead of a deregulated globalization which rides roughshod over the rights of nation-states and communities, civil-society groups from Bolivia to China are calling for a radical restructuring. The aim is for an economic system more connected to real human needs and aspirations – and less geared to the anti-human machinations of the corporate-led free market. In the next chapter we’ll look at how we might get there.

1 millenniumassessment.org/en/index.aspx. 2 C Flavin and G Gardner, ‘China, India and the New World Order’, State of the World 2006, WW Norton, New York, 2006. 3 M Wackernagel & W Rees, Our Ecological Footprint, New Society Publishers, 1996. 4 Quoted in Kalle Lasn, ‘The global economy is a doomsday machine’, see nin.tl/globaldoomsday 5 ‘Commodities and Development Report 2012’, UNCTAD. 6 Gerald Greenfield, ‘Free market freefall’, Focus on the Global South, focusweb.org 7 George Monbiot, ‘The price of cheap beef’, Guardian, 18 Oct 2005. 8 Damian Carrington, ‘Amazon deforestation increased by one-third in past year’, Guardian, 15 Nov 2013. 9 Anthony Faiola, ‘Brazil’s sick economy infects the ecosystem’, Guardian Weekly, 25 Apr 1999. 10 Walden Bello, ‘The end of the miracle’, Multinational Monitor, Jan/Feb 1998. 11 Friends of the Earth, The IMF: selling the environment short, see foe.org/res/pubs/pdf/imf.pdf 12 David Braun, ‘Madagascar’s logging crisis’, National Geographic, 20 May 2010, nin.tl/madagascarlogging 13 Tim Cocks, ‘Malagasy Wilderness in the Balance’, BBC news, 14 Feb 2005, nin.tl/malagasywild 14 Joseph Stiglitz, Globalization and its Discontents, WW Norton, New York, 2002. 15 ‘Capitalism needs new rules’, Joseph Stiglitz, Guardian, 2 Sept 2014. 16 Martin Wolf, The Shifts and Shocks, Penguin, London, 2014. 17 Human Development Report 1999, UNDP, New York, 1999. 18 How was life? Global well-being since 1820, OECD, Oct 2014. 19 Martin Hart-Landsberg, ‘The US economy and China’, Monthly Review, Feb 2010. 20 Human Development Report 2005, UNDP, New York, 2005. 21 D Raphael & T Bryant, ‘Income inequality is a deadly problem’, Toronto Star, 24 Nov 2014. 22 Paul Krugman, ‘The Rich but invisible’, New York Times, Oct 4/5 2014. 23 Danny Dorling, ‘How the super rich got richer: 10 shocking facts about inequality’, Guardian, 15 Sep 2014. 24 ‘Pay and economic growth’, Economist, 2 Nov 2013. 25 Madelaine Drohan, ‘No mean feat to crack down on tax havens’, Globe and Mail, Toronto, 12 Apr 2000. 26 Michelle Faul, ‘Ebola crisis made worse by IMF austerity plans for Africa’, AP, 30 Dec 2014. 27 Richard Dobbs & Anu Madgavkar, ‘Five myths about India’s poverty’, Huffington Post, 2 Jun 2014. 28 ‘The policy roots of economic crisis and poverty’, saprin.org/global_rpt.htm. 29 P Sparr, Mortgaging women’s lives, Zed Press, 1994. 30 Lori Pfingst, ‘Women, work and Washington’s economy’, Washington State Budget and Policy Center, Feb 2012.