For a peaceful meditation, we need not go to the mountains and streams. When thoughts are quieted down, fire itself is cool and refreshing.

—Suzuki, 1973

• Distinguish the different forms of anxiety

• Examine the anxious brain

• Engage your whole being: mind, body, and spirit

• Calm your nervous system with postures, breathing, and meditation

• Enlist mindful attention

• Work through by building understanding, courage, and acceptance

If you are feeling anxious, you have probably noticed that anxiety has many different effects on you. You might have nervous feelings, thoughts, and uncomfortable sensations in your body as well. In fact, anxiety does influence all of these levels. And so, it makes sense to overcome anxiety by enlisting every resource you have, using your mind, body, and spirit. Yoga and mindfulness are well suited for lowering anxiety, since these practices work on all these different levels together, to alter the whole mind-brain-body system in positive ways. A great deal of research shows how effective yoga and mindfulness are for anxiety. In our recent book, Meditation and Yoga in Psychotherapy, we recount many of the scientific studies that use yoga to treat anxiety (Simpkins, 2010), and in Zen Meditation in Psychotherapy, we describe mindfulness research (Simpkins, 2011). You can be confident when using yoga and mindfulness to alleviate anxiety.

Approach the exercises in this chapter with patience. Remember that it takes time to alter an entrenched pattern. Even drug therapies can take several weeks before beginning to have an effect. You may not feel the results of yoga and mindfulness immediately. The effects are gradual. Expect to feel relief over time, as your turbid pattern of anxiety dissolves in the clear waters of meditation.

Teresa was in her senior year at college. She had been a top student and had started applying to graduate school. But this year, she was having trouble concentrating. Whenever she sat down to study, she got nervous. Her stomach tightened up, and her heart raced. Her grades were slipping, increasing her anxiety. She tried meditation, but found that when she sat still, her anxiety worsened. She believed in meditation. After all, her cognitive science professor had presented compelling evidence for meditation’s calming effect on the nervous system. As she told us, “I’m here because my mind says yes, but my limbic and motor systems say no. Please help me!”

We began her therapy by working on a key principle of yoga: to link her mind and body. But for her we decided to approach it with a twist: do it in motion. She began with breathing meditations combined with simple body movements similar to the breathing meditations in this chapter. She practiced linking her attention to her movements in meditative breathing exercises and yoga postures. As she became aware in the present moment, she was shocked to realize how much her mind had jumped ahead. “I’m always thinking about what comes next—never what’s happening now.” She had been so caught up in graduate school and what lay ahead that she had lost her engagement with the present moment. She realized that by anticipating so much, she was actually avoiding facing her current concerns, doubts, and worries about her own self-worth. She used the yamas and niyamas to build inner strength. As she unified her attention with her actions in the here and now, she discovered a new sense of calm and confidence. Her anxiety subsided. Eventually, she was even able to sit still and meditate, but as a busy and ambitious young woman, she continued to prefer meditation in motion!

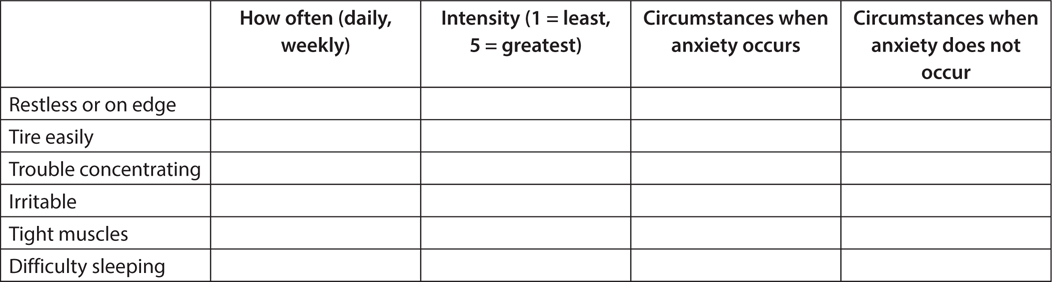

People are troubled with anxiety in different ways. We have included a checklist for the many forms of anxiety, drawn from criteria used by therapists and doctors to help diagnose problems. But realize that labels can never fully explain what you are going through. You may find it helps to ease your anxiety if you better understand your tendencies and recognize what form of anxiety you are experiencing.

Check if you felt troubled with any of the items on the checklists for more than a few days over the past six months. If you find that you are severely and continually bothered by your anxiety, tell your therapist or seek a professional to work with you as you integrate yoga and mindfulness into your treatment.

GAD involves a broad, overall feeling of anxiety that can inhibit you from doing things and going places. If you have GAD, you tend to approach your life with exaggerated and unrealistic worry and carry a great amount of tension, even though your worries are highly improbable.

FIGURE 12.1 GAD Checklist

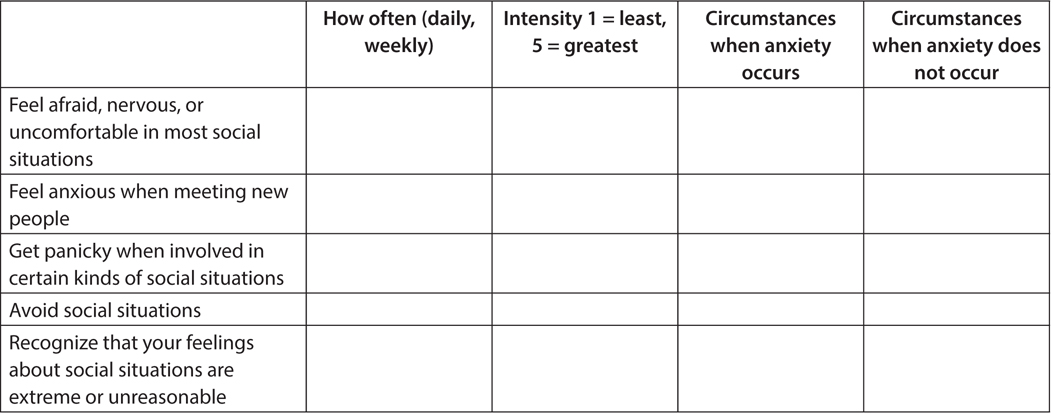

SAD is felt in social situations and is experienced as intense worry, shyness, embarrassment, and self-consciousness. If you have SAD, you may feel as if others are judging you negatively or even ridiculing you. Sometimes the anxiety arises under specific circumstances, such as feeling uncomfortable speaking publicly. For others, it manifests as a generalized feeling of discomfort around people.

FIGURE 12.2 SAD Checklist

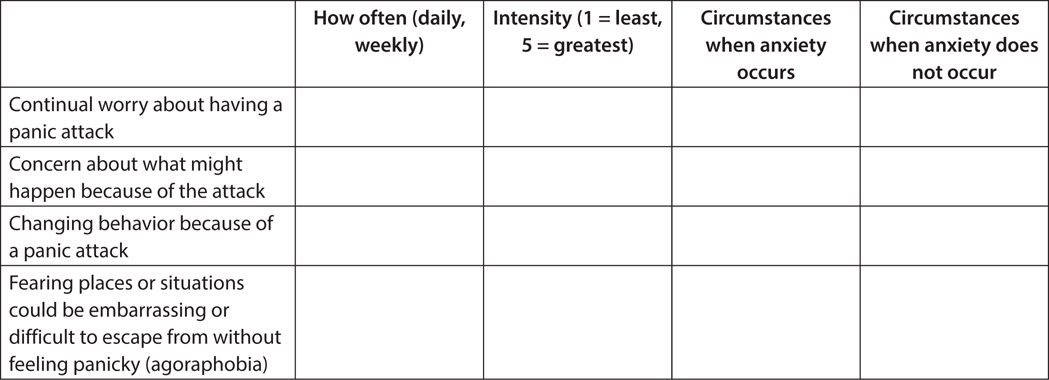

Panic disorder is often experienced as a severe physical crisis, such as a heart attack, when there is no real physical problem or danger. An intense panicky feeling strikes repeatedly without warning. If you have panic attacks, you might have uncomfortable physical symptoms such as pain in your chest, sweating, and irregular heartbeats.

FIGURE 12.3 Panic Disorder Checklists

Check if you have had any of these worries about panic attacks over the past month:

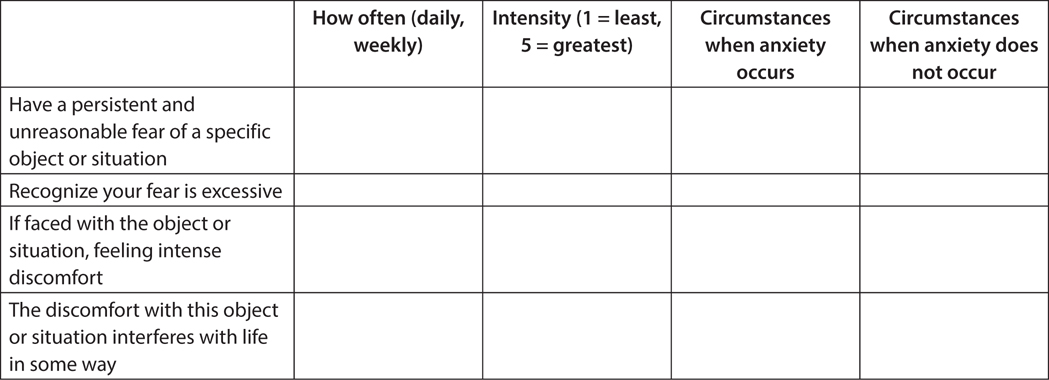

If you have a specific phobia, you have a fear of a particular thing, such as being afraid of dogs, heights, spiders, elevators, open spaces, or enclosed places. These fears are often initiated by a traumatic event. When you encounter the feared object, you probably experience an inordinate level of anxiety that is likely to cause you to avoid that feared object or situation.

FIGURE 12.4 Specific Phobia

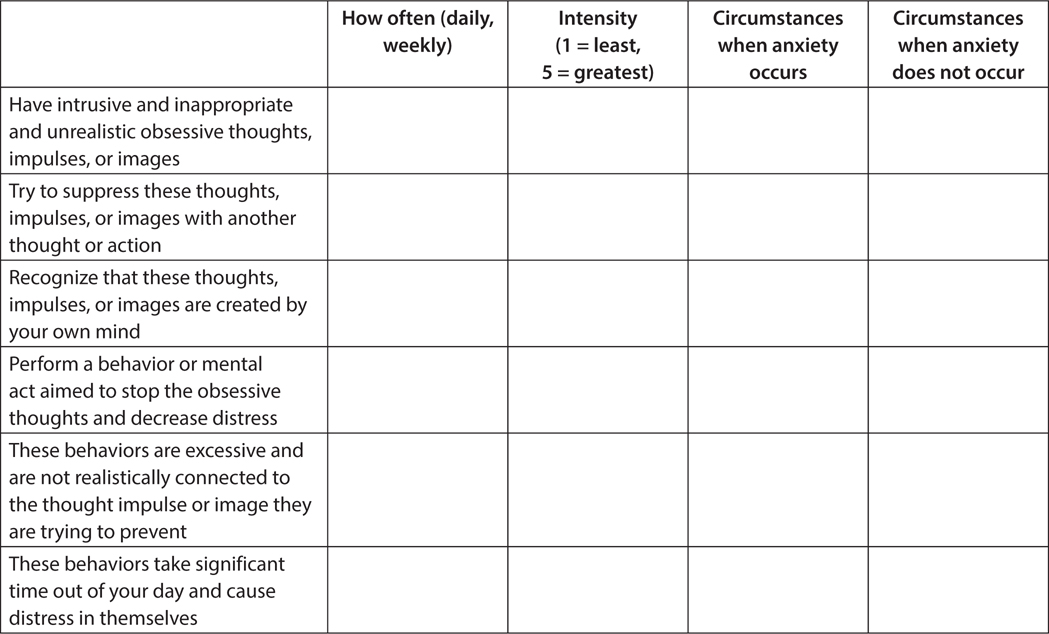

OCD is also categorized as an anxiety problem. If you have OCD, you are likely to be plagued by disturbing thoughts (obsessions) and/or fears that make you feel compelled to perform particular actions or rituals (compulsions). For example, people diagnosed with OCD may have such a strong fear of infection that they feel compelled to wash their hands continually. Thoughts that plague people with OCD are often irrational and unrealistic.

FIGURE 12.5 OCD Checklist

From the symptoms listed previously, you can clearly see that anxiety involves your mind and your body. In fact, your nervous system undergoes distinct changes when you are feeling anxious. Thus, it makes sense to work on both the mind and the body when treating anxiety.

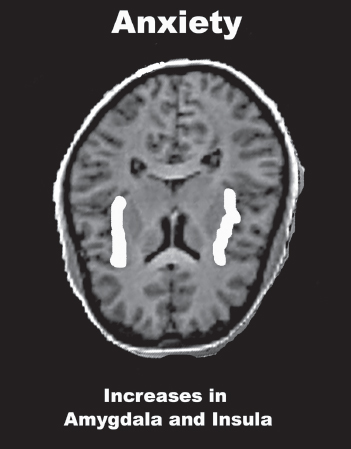

FIGURE 12.6 The Anxious Brain

Anxiety involves a number of brain systems that have a strong influence on what you feel and think. The thalamus acts as the doorway for signals received from the senses and passed along to other parts of the brain for processing. During an anxiety reaction, the amygdala, the gateway to the limbic system, alerts the hypothalamus that something is wrong. The hypothalamus, as the coordinator of internal functions, activates the fear/stress pathway (see Chapter 11, pages 84-85), which puts the autonomic nervous system on high alert. The hippocampus, where memories are processed, adds to the signal. In addition, the insula, which registers internal sensations, is activated by the inner discomforts. And, the cortex gets involved with disturbing thoughts and ruminations. The normal connectivity between the amygdala and frontal, occipital, and temporal lobes is decreased, leading to less successful regulation of emotions. With so many systems in the brain involved, you can understand why anxiety can be so pervasive and disruptive.

1. Decreased activity of serotonin (5-HT). Serotonin inhibits the stress response

2. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory and calming neurotransmitter is lowered. Norepinephrine (noradrenaline), an excitatory neurotransmitter also involved in stress, is increased.

3. Corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH), a stress hormone, is increased, signaling the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotrophic hormone, which in turn signals the adrenal gland to produce cortisol.

Typically, drug therapies used for anxiety increase the amount of GABA and serotonin, while decreasing norepenephrine and CRH in the system. The drugs help reduce over-excitation and elicit calming. But drugs are not the only way to alter the balance of neurotransmitters: Yoga and mindfulness can also be used to calm your system and rebalance your neurotransmitters.

Buddha told his followers that change is always two-sided: first, doing what is right and second, not doing what is wrong. It is very important when making a change that you stop doing unproductive, unhelpful things. You may have some simple lifestyle habits (sleep, diet, or exercise) that contribute to your discomfort. By making minor alterations in your daily routines, you create a basis for new possibilities to emerge. Then, as you become physically healthier, some of your anxiety will lessen.

Begin by observing your habits for eating, sleeping, and exercising using this chart. Keep in mind the mindfulness approach, and observe without judgment. Any change requires that you first observe what is really happening. Be objective as you note your weekly habits. This might help identify some fundamental ways that your habits are contributing to your anxiety.

FIGURE 12.7 Charting Your Habits

Does your chart indicate that you are not sleeping enough, eating poorly, or rarely exercising? Perhaps anxiety is preventing you from changing your habits. Nonetheless, you can still make small changes—doing one or two things differently—to help you foster healthier habits. As the ancient Taoist sages taught, “The journey of 1000 miles begins with one step.” Be open to the possibility of forging healthier habits, and you have already taken your first step.

The nervous system changes when you are anxious: you may feel “hyped up,” that is, highly aroused. This occurs from activation of the alertness center of the brain, the brain stem. You can diminish anxious feelings by deactivating this area. Begin the process by practicing calming regularly. Perform the calming exercises for stress in Chapter 11, pages 87-90, to initiate calming bottom-up. However, if you are like our client Teresa, sitting still may be hard for you to do. You might find it easier to practice active calming. You can begin a calming process more easily by breathing with motion, moving into yoga postures, and performing mindful walking.

Do the meditations for a short time at first, even just a few minutes, but do them several times during the day. If you have been chronically anxious for a long time, you will have stronger results by performing the exercises as often as possible. In time, your nervous system stabilizes in a calmer balance, and your anxiety reaction will ease. Start the process with these meditations to relax and release the breath while you move.

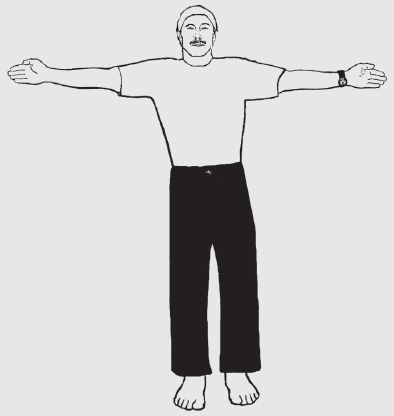

This exercise opens up your chest and allows the air to flow freely through your lungs. You gain greater calm and increased comfort from the opening of your chest, while also raising your energy level. Time your arm movements with your natural breathing.

Stand in mountain pose and extend your arms out directly in front of you as you exhale. Maintain your balance and let your arms swing around behind you, parallel to the floor while you inhale. Let the air fill your lungs fully as you allow your chest to expand. Exhale as you circle your hands back toward the front. Repeat this pattern several times, coordinating your breathing with the movement.

FIGURE 12.8 Chest Expansion

FIGURE 12.9 Chest Contraction

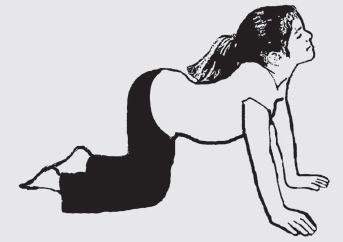

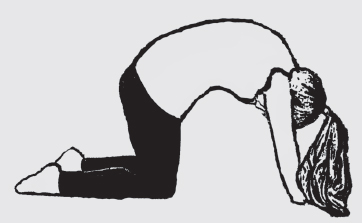

Have you ever watched a cat stretch, and marveled at its flexibility? The cat’s breath is drawn from this elastic movement. Anxiety often correlates with rigidity in your breathing passages. Gently stretching and releasing these areas can restore flexibility to your breathing, like a cat. These two postures help you relax and stretch your back and midsection, coordinating your breathing with the movement.

Begin on your hands and knees. Inhale as you gently and slowly arch your back and raise your head to look straight in front of you. Feel the movement. Let the air fill your lungs completely. You should allow the releasing stretch along your entire back without pushing hard. Then exhale slowly and round your back carefully as you pull your stomach gently in and tuck your head down. Again, only do what is comfortable. Repeat the entire sequence several times, moving and breathing slowly with the movements. Keep the rest of your body relaxed, such as your jaw, face, and neck as well as your arms and legs. Maintain focused attention and move slowly.

FIGURE 12.10 Arched Back

FIGURE 12.11 Rounded Back

Posture practice is an easy way to invite balance as you shift your attention away from intrusive thoughts and feelings. This simple series of postures is balanced and easy to perform. You can substitute other yoga routines. We suggest using poses that bring balance to both sides of your body by moving up and down, forward and backward, on one side and then the other. Rediscover your sense of balance through your body. Since the mind and body are linked, bringing balance to your body can lead to tranquility of your mind and centering in your life.

In general, when doing yoga postures, move into each position slowly and keep your mind focused on what you are doing as you do it. Pay attention to the subtle differences in tension and relaxation of various muscles. Observe your sensations and body posture. Keep your breathing in synchrony with the posture. Generally, inhale as you extend and exhale as you contract. Stay attuned at all times and you will derive deep benefit: from the simple comes the profound.

Rest for a moment in the crocodile pose (see Figure 6.17). Lie prone on the floor with your head resting on your arms. Let your body relax completely. Gently breathe in and out, as you let go of any unnecessary tensions. Remain relaxed in this position until you are ready to continue the routine.

Now, as you are lying comfortably on your stomach, move your legs together and place the palms of your hands flat on the floor under your shoulders, elbows at your sides, and forehead resting on the floor to get ready for the cobra stretch (see Figure 11.8). Breathe in and out several times, relaxing in preparation. Inhale as you raise your chin and head up slowly. Let your gaze move upward as you bend your neck, carefully tensing, backward. Then lift your chest, curving your back up as you gradually raise your upper body, one vertebra at a time. Keep your hands on the floor, arms extended for support. Use your back muscles rather than pressing with your arm muscles to provide support while rising up in the cobra stretch. Keep your lower body relaxed, resting on the floor. When you get to the top, hold the position for 10 to 15 seconds as you breathe naturally. Then exhale as you reverse your motions, lowering yourself down very slowly, one vertebra at a time, relaxing your neck as you lower, and finally resting the back of your head on the floor.

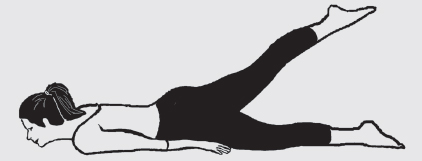

Now, continue to lie on your stomach with your arms at your side and palms facing down on the floor. Push against the floor with your palms. Raise one of your legs up off the floor, as you inhale. Hold the position as you breathe in and out for a few seconds, and then slowly lower your leg. Next, perform the same motion with the other leg. Finally, if you have the strength, raise both legs together and hold as you breathe and relax everywhere else. Although you will need to tense some muscles, keep your upper body as relaxed as possible.

FIGURE 12.12 Half Locust Pose

Pick one of the movement exercises you liked best. Perform it now, allowing movement to occur naturally. Let your attention focus on the movement, and allow the motions to flow. Become completely absorbed in the movement without any conscious thought about it. Just be unified, mind, body, and spirit moving as one. As you permit this meditative union to develop, you will experience a sense of well-being and peace. Enjoy the moment!

When you are feeling anxious, you may often try not to feel it. But trying to avoid your anxiety can unwittingly make you feel more anxious. By becoming mindful, you can disentangle the web of your anxiety pattern. These exercises take you through a series of steps. Observe mindfully, without judging what you see. Trust that through this process, you will make some helpful discoveries that you can use in the next section. This series of exercises is especially helpful for people with GAD, panic attacks, OCD, and specific phobias.

A pure sensation, thoughts about the sensation, and emotional reactions can be distinguished using mindfulness. This helps to loosen the strands in the web of your anxiety reaction. The first step is to notice the different components of your reaction: the various sensations, thoughts, and feelings.

Start by turning your attention mindfully to the sensations of your anxiety. First attend to the qualities of breathing: sensory details, such as the air coming into your nose, its temperature, and the sound it makes in the passages. Each breath has its own group of sensations. Let your attention move to the feeling in your chest, stomach, or any other area that is associated with your breathing sensations. Notice how your rib cage lifts and drops with each breath, or how your stomach feels tight. Perhaps your face becomes warm.

Even if they are uncomfortable, simply observe and be curious about your sensory experience. Your sensations change, even though the change is subtle, with every passing moment. Allow your focus to move as your sensing unfolds.

Anxiety usually engages a set of thoughts, likely in a repetitive pattern. Just as you learned how each breath is a combination of a number of sensations in the “Mindful Breathing” exercise (Chapter10, on page 77), so your anxiety reaction is a web of sensations interwoven with threads of repetitive thoughts, probably negative interpretations, and worries, along with characteristic moods and emotions.

Pay attention to your thinking process. Do your best not to get caught up in any particular thought. Instead, take a step back as if you are watching the whole pattern move in the wind. The shapes and patterns shift, sometimes more thoughts occur, sometimes less. Observe your patterns of thought as they change over time.

Now pay attention to any emotions concerning anxiety that may be occurring along with those thoughts. Simply notice what emotions you feel as you feel them. Don’t assess these emotions or think more about them. Once again, just observe.

Take a step back and pay attention to the connection between one thing and another, such as how a thought might be tied to a sensation or a feeling. Do you notice a characteristic order? Perhaps you have a thought or sensation followed by a feeling. Or maybe it goes the other way. Simply notice the flow, moment by moment as you become familiar with the patterns you observe.

You probably have situations, people, thoughts, or memories that tend to trigger an anxiety reaction. Practice your mindfulness meditation in different situations when anxiety arises.

Are you aware of the moment right before your anxiety occurs? Pay attention to what triggered the reaction. Notice whether the anxiety comes on quickly or builds gradually over time. Observe that building process: Are you telling yourself frightening, awful, or worrisome things?

Now, listen to your inner talk while you are having an anxiety reaction, but do so mindfully. Observe whether the conversation comes in a cascade of thoughts about what is going on within, or in trickles of words, individual ideas. Notice any emotions that are evoked by the thoughts. Observe associated sensations, and how they develop over time. Pay attention to each experience as it occurs.

Finally, observe mindfully as your anxiety eases. Did you do anything to bring that about, or did it just happen? When anxiety recedes, does it do so suddenly, or do you feel it easing a little bit at a time? Take note of the sensations, thoughts, and feelings associated with the end of your anxiety reaction. Paradoxically, sometimes it is easier to recognize that you were anxious immediately following an anxiety reaction. Perhaps the contrast helps recognition. Mindfulness makes recognition more evident.

At the end of this chapter, you will find guidelines for journaling and charting. Take a few moments to record what you have learned about your triggers, how you sustain your anxiety, and how to help it diminish and even leave entirely.

Years of anxiety condition groups of neurons to form links in the brain. Meditation practice can literally rewire your nervous system by interrupting the anxiety reaction and substituting calm instead. The change occurs all the way down at the neuronal connections. The practice draws on your ability to relax, which you have been practicing all through this workbook, and your ability to focus your attention, which you have also trained by working through the exercises in this workbook. Meditative re-learning is most helpful for anxiety that is targeted to something you can identify, such as specific fears and social anxiety. But you can vary it to fit your situation. The example we use here is fear of water. Substitute your own fear, anxiety, or trigger with appropriate variations. Work gradually, building your skills, step by step. Repeat this meditation regularly until you are able to stay calm all the way through.

Allow your muscles to relax. Warm up with a visualization exercise. Perhaps you could picture a pleasant place where you felt very comfortable. Relax and enjoy the image. Once you have reached a deep feeling of comfort, begin by thinking very generally about your fear. If it is a fear of water, contemplate water in general, thinking about water in a distant way. Picture yourself far away from a body of water, such as the ocean, a lake, or a pool, perhaps behind a high fence. Maintain deep relaxation and begin to imaginatively walk toward the water. If you start to feel tense, pause in your imagery, backtrack, and reestablish your deep relaxation. Continue to relax deeply, as you imagine being barely able to see the water at a distance. The first day, you may want to stop quite a distance away.

At a second session, try again. Begin with relaxed breathing or an image of a beautiful place you enjoy. Then, picture yourself gradually moving closer and closer to the water, but always backtrack if you feel fear or discomfort. Take as long as you need. Keep working with this image until you can enter the water and remain calm. Then, let yourself gradually step deeper, maintaining your calm breathing, in and out. Continue to breathe comfortably until you have successfully entered the water while remaining relaxed. Maintaining a meditative calm generates a ripple of healing.

Repeat this exercise over several days or even weeks. Check out your reactions by thinking about water when you are not meditating and notice what you feel. You may surprise yourself. A carefully constructed hierarchy, from the least threatening to the most threatening may help you gradually face your situation with confidence and master it.

How can you integrate all your new learning into your life? Begin with acceptance. Mindfulness is a process of accepting each experience, each sensation, thought, or feeling, just as it is. Its practice reveals a depth and breadth of experience that is usually missed or ignored. As you observe the fabric of your experiencing more closely, you probably can see some things you like and some things you don’t. You might ask yourself why would I want to accept an uncomfortable feeling or unpleasant sensation? Paradoxically, by accepting everything, the good as well as the bad, you transform. Through the practice of accepting and letting be, you will discover your potential to be at peace with who you are.

So first, find a time when you are feeling comfortable to perform your mindfulness meditation. Next, practice at times when you are feeling anxious. In both situations, accept each moment’s experience as just that—an experience. Practice this way for one minute, then two and three—extending to as long as you can. If your attention wanders or you find yourself worrying or telling yourself how awful it is, stop, take a relaxed breath, and go back to being aware. Don’t chastise yourself, just take note of it, and return to the meditation. By treating yourself gently and kindly—literally accepting whatever you experience as okay—you open the way to being more comfortable with yourself.

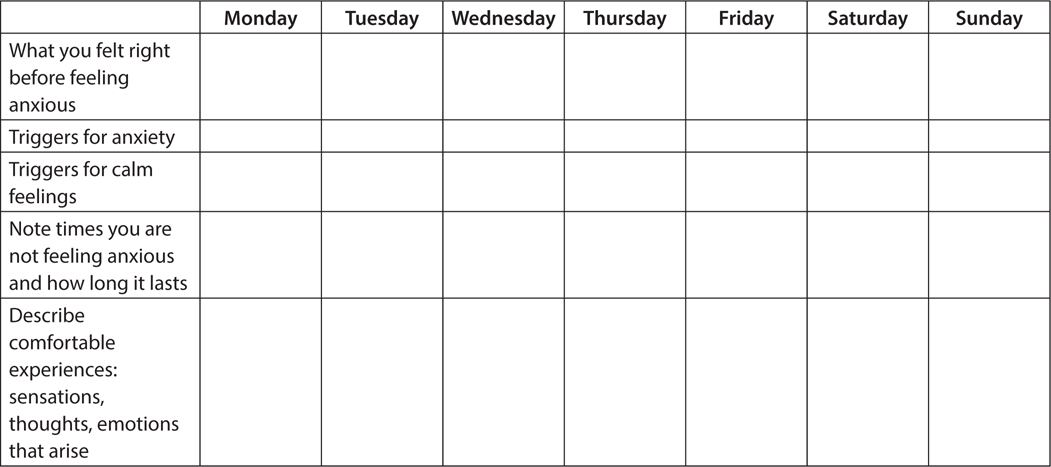

Keeping a journal and charting can be helpful as you become aware of the entire process of eliciting, producing, maintaining, and letting go of an anxiety reaction. Once you become aware of your triggers, cycles, and patterns, you can alter the automatic response and lessen the discomfort. Be aware of your responses and write them down. Remember to reflect on them mindfully, and later, update your journal with new discoveries and observations.

When you practice mindfulness of things that bother you, conflicts lose their hold and dissolve. Research has supported that mindfulness is effective alone, without directly addressing personal issues. But sometimes, unresolved issues may still emerge, needing to be attended to, worked through, and let go of when appropriate. You can work some of these issues through by journaling. If the issues are too painful or difficult to face alone, or you realize you are feeling defensive, bring this material to your therapist. The following questions will help guide your mindfulness meditation as you work toward resolution:

• What situations or activities do I find most comfortable?

• What situations tend to trigger anxiety?

• How do I feel just before I encounter a trigger?

• How do I perpetuate an anxiety reaction or even make it worse? What are the typical things I tell myself when I feel anxious? Am I adding a threatening quality?

• Could I interpret my situation differently, such that I would not find the situation anxiety provoking?

• How can I help myself to feel more comfortable when I am having an anxiety reaction? What situations or activities help me to feel more comfortable when I am having an anxiety reaction? List the possibilities.

• What situations can I use or activities can I do to prevent me from having an anxiety reaction?

You have explored when you are anxious, but it is equally valuable to turn your awareness to those times when you are not anxious. Keep a chart to observe when you are not having anxiety. As you become more aware of the moments when you are comfortable and at ease, you will be better able to extend and deepen them.

FIGURE 12.13 Without Anxiety Chart