CHAPTER 16

How To Have Tough Conversations Successfully

Some years ago a scientific company was in danger of losing government funding due to poor results. The CEO had tried to solve the issue with different project approaches. Then he realized the problem wasn’t a bad project plan, or even bad people. The plan was solid, and these folks were smart. The problem was that his team wasn’t working together. He called us.

We listened to his challenges then crafted an engagement that would take them through the first year and get them to successful completion of their government project. Throughout the year, we facilitated six off-sites. At the end of our first day of the first two-day off-site, CrisMarie and I chatted about one of the older team members.

“Drew hardly said a thing all day,” CrisMarie said. “I could tell he was bored and disappointed in the day’s events.”

“He did seem a little disengaged,” Susan replied.

“I don’t want to push.”

“Agreed. He was resistant to this whole team idea in the first place. Why don’t we see how it goes tomorrow morning, and if he still seems disengaged, we’ll check it out with him.”

We both were certain Drew was an unhappy camper. And because we each came to that assessment independently, we felt confident we were right.

We didn’t make any significant changes to the remainder of our session, and we were happy that Drew did speak up more as we continued. But what really surprised us was what happened when we asked for closing comments at the end of the two days. We both expected Drew to say something negative. To our surprise, when it was his turn, he sat up straight and his face lit up.

“This was the best two days I’ve ever spent at a team off-site in my career,” he said with a smile. “We got more done than I ever expected, and I actually enjoyed myself.”

So much for being right!

It is common for people to create a story about other individuals or situations with only limited information. Even coaches who help others avoid that trap aren’t immune. We create a story, we believe that story, and we move forward without thinking otherwise.

We chatted with Drew as we were leaving at the end of the second day. We told him how we had interpreted his looking down and staying quiet as disengagement. We shared that we understood our interpretation was wrong, and how glad we were to learn something new about him. Drew’s response?

“You know, my wife tells me that all the time,” he said. “I never have been one to smile or make a big deal out of things. But she has taught me that I’d better say something, so I’m glad I spoke up. I imagine there are others like me, so I’m happy you learned something.”

When you tell yourself a story about someone and assume you’re right without giving the other person room to express, you almost always treat that person unfairly. It’s impossible to know what is going on inside another person—how they think, feel, or what their motivations are—unless you explicitly check out your story. Only they can confirm what is happening for them on the inside.

Fortunately, in Drew’s case, we didn’t change the process or the outcome of the off-site. But we have to admit we were more cautious and guarded with Drew than we were with the rest of the team.

If we hadn’t checked it out directly, we could easily have interpreted Drew’s participation (or lack thereof) as wrong and created even more distance from him throughout the course of the engagement. Instead, we got new information and discovered Drew was on board.

The solution isn’t to shut down the storytelling or judgments. It’s sharing your judgments with vulnerability and curiosity—what we call ‘Check It Out!’—that enables you to bridge the differences between people, build trust, and create greater engagement.

When you share your own interpretation or opinion, you reveal more about how you put the world together than about the other person or situation. That’s why it takes vulnerability. You are revealing your own personal truth, and not the truth.

Most human beings have a desire to express who they are, to speak up honestly, and to show how they feel. People also want to be liked and accepted by the group. And there’s the paradox and tension. We want to be understood, but also to control the situation and avoid rejection. Believing we’re right is one way to stay in control. Letting go of the need to be right and revealing how we put the world together is like leaping without a net.

This is why people ask questions. When you ask questions, you remain safely hidden, not revealing your beliefs, just gathering new information. This seems like a great strategy, but when it is overused (as I, CrisMarie, have done over the years), you can end up thinking your opinion doesn’t matter.

Come out of hiding. Find out if the story you’ve told yourself fits with others’ experiences, and be open to their answers. That takes courage and curiosity.

By sharing your judgments, interpretations, opinions, assumptions, or theories as a story, and not claiming them as fact, you create a space for the other person to give you new information. This is the heart of closing the gap between team members and, in doing so, building trust. Share your story, then say, “Where do we agree or disagree?” Or, “Tell me where this doesn’t make sense to you.”

We use the term story to remind leaders that they make it up as they go along. We all do. Why not check to see what fits for the other person?

HOW TO BREAK IT DOWN

Have you ever been in a meeting and thought, “Great, we’re all on the same page,” only to find out everyone had a different interpretation of the same events? Or maybe, like we did in our interaction with Drew, you created a story about someone that was completely wrong?

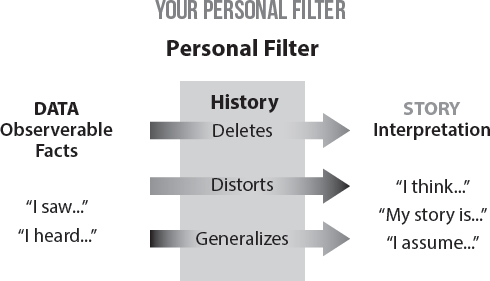

Each person processes incoming information differently because everyone has different backgrounds and experiences that shape how they think. You aren’t exempt. As humans, we attach meaning to what we hear, see, and experience. It’s natural. The brain is a meaning-making machine. We make meaning through the data we take in and sort the data through our personal filter. Then we create a story, which drives how we feel. Just remember, everyone processes incoming information differently. Let’s take a look at each of the steps of meaning making.

HOW HUMANS PROCESS11

Data

You receive information or data through your senses: what you hear, see, tas te, touch, and smell. In business, it is primarily limited to what you hear and see; although, we have worked for several food companies where tasting and smelling come into play.

Data is the objective information with no meaning attached. For example, I see someone who is crying and sad. This is not objective data. If I am truly objective, the more accurate statement is that I see someone who has tears on her cheeks, or even more objective, who has water on her cheeks. I don’t know how she feels. Maybe she has allergies, or maybe there’s dust under her contact lens.

You take in data, and it is processed through your own personal filter. Your personal filter is made up of all that makes you unique: gender, age, where you grew up, past work history, and your significant emotional life events. Your brain sorts the data, labeling some things good and other things bad. You do this unconsciously. Say, for example, when you were young a small dog bit you. Ever since then you’ve been afraid of small dogs. Your brain and nervous system now categorize all small dogs as dangerous. Today, when you see a small dog, you immediately feel fear. For someone else, seeing a small dog might elicit a completely opposite or even neutral reaction.

As the information or data goes through your personal filter, your brain deletes, distorts, and generalizes information. That’s why each member of a team can have different interpretations of the same event.

Your Story

Data goes through your personal filter and out pops your story. Your story is your interpretation, hunch, opinion, assumption, theory, or judgment of the situation. Remember, we use the word story to emphasize that people make things up as they go. Your experience may strongly reinforce your story, but it’s still your story just the same. Here are some examples:

“Joe’s the smartest guy on our team.” This is a story, not a fact. Your collected data may lead you to this conclusion (he speaks up quickly in meetings, always has data to back up his position), but still, it’s only your opinion. To verify it as a fact, you could compare IQ scores. Even then someone else may bring a different type of smarts, such as emotional intelligence, to the situation.

“My boss does not like me, and he always gives me the hardest assignments.” Maybe you can point to pieces of data that lead you to this conclusion, but still, it is just a story. You don’t know how your boss feels about you unless you ask him. You may think you get the hardest assignments, but how do you measure that?

It’s critical to notice that your story is your creation and that it’s not necessarily true. And it’s important to know that your stories drive your feelings.

Your Feelings

We generate feelings from the stories we tell ourselves. Feelings come in four major categories: happy, sad, mad, or scared. There are many variations on these four emotional themes, and we’ve made it simpler by reducing it to two categories. We focus on physiologically—relating emotions to the movement of energy in the body.

Our emotions are energy in our body. Similar to how the waves of the ocean ebb and flow, when we respond to something at a feeling level, we are either opening to it or closing it off; moving toward it or away from it. At the physiological level this can register as temperature change or a sense of distance between me and another. So we can feel warm toward someone or cold to them; close to them or distant from them.

One way of thinking about emotions is related to your physical location relative to someone else or someone’s idea. Do you want to lean forward or lean back and cross your arms?

Let’s experiment.

Start by bringing to mind someone you are fond of. What happens in your body? Do you open and soften? Do you feel warm? Do you notice yourself lean forward?

Now think of someone that you have a strong distaste for. What shifts in your body? Do you tighten or brace anywhere in your body? Do you get colder or notice a desire to back up or turn away?

This exercise helps you notice your own internal landscape. Everyone has their own unique physiological reaction. We encourage you to bring your awareness to how you feel in your body when you experience positive or negative events in your day.

Intention

From feeling we generate intention. Our intentions are what we want, desire, or wish for. We can have more than one intention in any given situation.

Example one: You’re dealing with a difficult direct report. One intention might be to give feedback and ask for information about their poor project performance. Another intention might be to communicate that you are in charge, and he needs to do what you tell him without questioning you.

Example two: You’re dealing with decision making on the team. One intention might be you intend to get input from your team, and another is you intend to make the final decision.

You may even notice your intentions shift in the moment. You may start with an intention to get input from your colleague, and as your colleague delivers information, you realize your intention is not to get input, but to simply relay your decision.

Check in regularly and notice your own shifting thoughts, feelings, and intentions.

As a meaning-making machine, recognize that you constantly sort data through your senses, and you attach your own meaning to the data. That generates how you feel. You cannot stop the data from coming in. Your brain is wired to receive it and translate it. We suggest that you be aware of the stories you tell yourself and consider that you may not be right. Make a point to check it out!

CHECK IT OUT!

Checking out your story with another person is the key to creating productive dialogue.

To illustrate, we’ll share a client story.

A national telecom client had asked us to design and implement a leadership-development program to help their team leaders become more effective by fostering creativity from conflict on their teams. During the three-day process, we had them practice Check It Out!

Two managers, Robin and Bernie, had worked together on a project at another company five years earlier. That project had failed, and both managers wound up leaving the company. Robin hated Bernie and blamed him for her own departure. Bernie didn’t trust Robin.

When they collided with issues during our program, we challenged them to Check It Out! Here’s how Robin checked out her story with Bernie:

Data: “I heard you went to my boss and badmouthed me.”

Filter: “I worked my butt off for that project.”

Story: “My story is that you had it out for me and were the reason I was let go.”

Intention: “I want you to talk to me directly if you don’t like something I have done, rather than go behind my back.”

Check it out: “Do you agree that you did badmouth me to my boss?”

Bernie was shocked. He had been a supporter of Robin’s years prior. That was until he heard she disliked him.

“Wow! I’m surprised. I thought you had undercut me,” he replied. “I did talk to your boss about the challenges I had with our project. I didn’t discuss you, though. I heard from others that you thought I was the problem. I never checked any of that out, and because of that, I thought of you differently.”

Robin and Bernie came back from this five-minute exercise in a totally different space with each other. Five minutes of checking it out completely transformed their relationship.

When we assume our story about someone is true without checking it out with them, we may treat that person unfairly. We create distance and build walls. The relationship becomes brittle, and the team’s productivity suffers.

We may take it even further by avoiding the person, gossiping about him, and swaying others to our point of view. This divisiveness is the root of politics, factions, and cliques that bond together to make someone outside of the group wrong. It snowballs as insiders continue to gather evidence that they are right. This creates more distance and dysfunction between the factions.

Break down the walls and distance by exercising the courage to check out your stories. Vulnerability and curiosity will enliven you. You will discover things you wouldn’t learn otherwise because you can’t know what is going on inside another person. It’s impossible to know how someone thinks or feels, or what his motivations are, unless you explicitly check out your story and hear it from him.

Remember the earlier experiment with feelings? Whether your feelings are positive or negative, check it out and see what happens!

The next time you find yourself judging or being stuck in your opinion, don’t shut down your imagination and creativity. Instead, remember to:

- Speak up

- Describe the data of how you came to your conclusions

- Share your judgments as a story

- Say how you feel

- Include what you want

- Check it out!

The possibilities are limitless. A narrow view of the world can restrict leaders from reaching their fullest potential. Having tough conversations opens our minds. When you reveal your perspective and check it out, you will most certainly discover new territory. Therein lives creativity, and that is the best path for continued learning and engagement.

If you want some more support on this topic, we have an easy stepby-step worksheet for you to follow called, How to Have a Tough Conversation at Work. Go to www.Thriveinc.com/beautyofconflict/bonus to download it now.

Next, we’ll see how silence, even though it feels like the safe bet, is deadly—especially on a team.