CHAPTER 28

Imagine you are leading your organization through a large change project: a merger and acquisition, reorganization, or massive technology project. As the leader, you have worked out the strategic plan, budget, resources, and timeline. All set, right? Wrong.

The Economist’s Intelligence Unit, sponsored by The Project Management Institute, conducted a survey in March of 2013 on strategic change project success. These 587 senior executives who were surveyed globally believe the failure rate on strategic initiatives is 44 percent.22 This is extremely high risk. We think that number reflects the fact that leaders aren’t focusing on how to help the humans in the organization adopt the change.

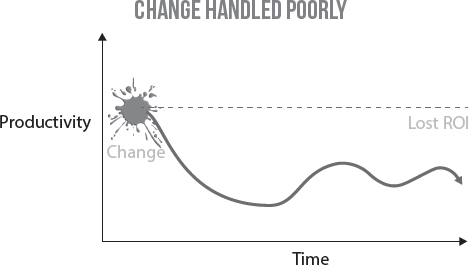

You will not reap the ROI on your big change project unless you bring along the people in your organization. Sadly, for many leaders that is often an afterthought. When change occurs, conflict erupts. People don’t understand why the organization is changing, or they disagree with the changes. Some individuals don’t want to let go of their old ways of doing things. They have a lot at stake.

People resist. Productivity suffers. Morale tanks. ROI is lost.

Don’t waste your time and money by not proactively considering the human element. Remember, your business is made up of a lot of MEs, individuals who have their own concerns and styles for handling change. When you focus energy on the ME and the WE, business results will increase dramatically.

MONEY DOWN THE DRAIN

When I, CrisMarie, worked at Arthur Andersen, I helped executive teams implement large-scale changes such as mergers, reorganizations, and enterprise resource planning systems. The biggest mistake CEOs made was to focus only on the business or smart side of projects without including the human or healthy side of projects. Ignoring people is like throwing money down the drain.

I came in to help the CEOs repair the damage resulting from a business-only focus. My Arthur Andersen team had one frustrated CEO, Bill, who called us after his company had spent a significant amount of money implementing a new financial system, and the project was failing miserably. Despite his efforts to tell, train, encourage, and force people to use the new system, employees kept their own systems in place, undermining the benefits of an integrated financial system.

In my interviews, I quickly learned that key financial data was missing from the new system. That caused manual workarounds, and it was so complex that it couldn’t help people meet their current workload demands, even if it might prove beneficial in the long run. The finance team was mad, even insulted, that Bill had not chosen the system they liked best.

I brought Bill to the financial department with the CFO to hear the frustrations of people in the finance department. It may seem like overkill to engage the CEO at this level, but the finance department had taken the decision quite personally. They wanted to be heard by Bill. He did a good job of reflecting back what he heard, he acknowledged his choice was different from what they wanted, and he expressed his desire to make it work. Good job, Bill!

After listening, he said, “We are going to use this new system, but tell me how we can make it work for you.” Together, they came up with a plan, and Bill was committed to making it work.

Bill, with the CFO and the entire finance team, gathered to kick-off a three-day boot camp to focus on three areas: advanced training, missing-data entry, and complex test, simulation, and troubleshooting. During the three days Bill came in and out checking on the progress of the team. At the end of the boot camp, the system was fully operational, and the finance department was its biggest supporter! Clearly, taking the time and effort to communicate, work together, and problem solve key issues was more powerful than giving the team a binder to work through.

WHY, WHAT, HOW, AND WHO

If you want a group or team to buy into a new way of doing something, focus on the human aspect. Get people involved, listen to them, and work together. You will build tremendous loyalty and engagement, and that is priceless. As coaches, our work with leaders includes focusing on the human side, which helps them reap the ROI of their business or smart investment. In short, we teach leaders to be proactive with change.

When I, CrisMarie, was consulting with Blue Cross Blue Shield in the early 2000s, I was lucky enough to get certified in the Leading and Managing Organizational Transitions through William Bridges & Associates. Much of how I approach change initiatives is influenced by William Bridges, the grandfather of change management and author of Managing Transitions. 23

A critical proactive measure is to be sure you communicate early, often, and in varied ways. Give your people what they need to get on board with the change. I’ve adapted Bridges work for this simple communication framework called why, what, how, and who. For people to buy in to change, they need to see the change from your point of view. You know why you want to change, what you are aiming for, how you are going to get there, and who needs to do what. Map that out for them, and remind them often along the way.

Why Start with why. People need to understand why this change is so important. You have a good reason. Let them know what it is.

What Paint a picture of how the world will look and feel on the other side of the change so people understand what you are aiming for. Your team wants to know how the destination will look and feel. Understanding the target will help them gauge their progress along the way.

How Lay out a step-by-step plan how the organization will get to the final destination. Plans may change as you travel and close the gap between where the organization is now and where you want it to go. Offer frequent updates.

Who Who needs to do what? Help people understand their role in making this change a reality. You can’t do it alone. Giving people a role helps them buy in to the change as they participate in the implementation.

In addition to the why, what, how, and who, people want to know that you care about more than just the business results. They want to know you care about them as human beings. When you communicate, let people feel like they are part of this process, because they are. You literally could not do it without them. Here are two ways to ensure your people stay engaged and on track to integrate the change:

- Show them they matter as people. They are not just cogs in the wheel. You hear and understand their points of view. Be considerate. Let them talk about where they are in the change process, especially if they are upset with it. Shutting down their frustrations only sends those feelings underground, causing bigger problems.

- Let them know you haven’t discarded them. Show the team how they are still connected to the company, to you, and to each other in the midst of this change. Give them a specific role to play, hear their feedback, and encourage their participation in the solution.

Combine the why, what, how, and who when you address the organization. This detailed communication gives people clarity about where they are going, and helps them get and stay engaged.

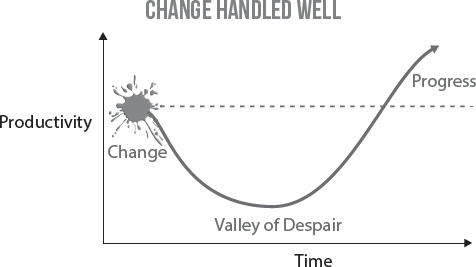

What happens when things get bleak? Let’s look at the Valley of Despair.

VALLEY OF DESPAIR

Change requires people to work differently, be it on a system or in a specific business process. Going from what was to what will be involves a period of transition. During this transition, productivity almost always drops. In change management circles, this is called the Valley of Despair. It’s based on and adapted by various Change Management experts from Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s “Five Stages of Grief” described in her book, On Death & Dying.24 Productivity drop during transition is due in part to concrete changes such as new systems and processes. It’s also due to the internal process human beings navigate to embrace the change.

William Bridges says that when change occurs, people have to experience psychological reorientation to the new way of being. For people who have been doing the same things at the same place for a long time, this does not happen overnight. People process at different speeds. As a leader, you can support individuals to move through this process.

What seems like resistance is often fear of the unknown. Most people really do want to do a good job. They resist the new way because they’re afraid of losing competency, status, control, relationships, turf, meaning, and/or identity. This fear mires them in resistance. Getting specific about what they fear they are losing and acknowledging that fear will help them move through the resistance.

For example, someone loses his feeling of competency when a new enterprise resource planning system comes in. His feeling is justified because employees are now a beginner in the new system. If they don’t acknowledge this loss, they will likely feel threatened, and may even quit.

All their organizational knowledge walks out the door with them. If they first acknowledge the loss, they can then feel it and move through to acceptance that they are a beginner. This makes it easier for them to engage in the training that is offered. Acknowledgement of what is being lost cuts down to size the impact of change. The system is new, but they still know all about the organization.

Once they identify their loss, they can move through the next phase and figure out how to replace or redefine what they have lost. Sometimes they have to come to terms with the need to relinquish something. We’ve seen this firsthand many times, but one particular client makes for a great case study.

We worked with an international, multi-billion dollar medical supply organization on a merger and acquisition. They were a big, stable, process-oriented sales engine that was acquiring a small, innovative startup. It was like merging David and Goliath.

The leaders of the start-up, the David, were terrified their culture wouldn’t survive the merger with the much larger Goliath. It was easier for Goliath to assume everything would go their way, but they desperately needed to be innovative in order to succeed in their industry. To help these two disparate cultures merge, we developed a cross-company change team with key people from both organizations. We worked with this leadership change team to develop a nexus of trust, communication, purpose, and plan to drive a successful merger. Once the team was clear, aligned, and operating well, we expanded to the next layer in the organization.

We conducted cross-company workshops on change. At these workshops, members from the leadership change team talked about their own experience with the change by discussing what was working and where they were struggling. It was authentic and real. Other leaders from both companies stood together and shared their common goals for the change.

During these interactive workshops, we provided tools and created experiences for the larger group to honestly discuss their views on the change cycle. Many related to being in the Valley of Despair. Asking questions, giving feedback, and checking out their stories of concern helped them digest the change and actively move along the change cycle.

We also taught them skills to deal with differences effectively, since we knew they would keep bumping into conflict throughout the change process. They made cross-company personal connections, which built trust and communication and went a long way toward breaking down the us-versus-them barrier.

In the end, the companies merged successfully and profitably, gaining the ROI they had hoped to achieve. Were there casualties? Yes, as there always are with big change. But the new culture harnessed the innovative nature of David while benefitting from the process-oriented sales expertise of Goliath.

Communica tion—early and often—is a key responsibility for leaders implementing big change. Communicate why the organization is changing, what the end goal looks and feels like, how they will get there, and who will do what to make it so. And remember, success depends on bringing your people along. Treat them as humans so they know they matter to you, to the company, and to each other. Be prepared for the Valley of Despair, and provide a path for individuals to honestly talk about their struggles in the change process. Give them ways to identify what specifically they’re losing in this change and how they can replace, redefine, or relinquish what they have lost.

Finally, keep in mind that big change can take months or years to successfully implement. Stay connected to your people for the entire journey.

You’ve probably noticed a theme in this chapter on change: communicate. While communication is multifaceted, there are a few key tools to support you in effectively communicating change in your organization. You, the leader, are the marketing arm to the rest of the organization. Pay attention to not only what you communicate, but how you communicate it.

Here are three common mistakes leaders make in communicating change:

- Sending crucial information by e-mail. Mistaken belief: Everyone now knows what to do and why. Everything will flow smoothly.

- Making a binder. In an off-site, the leader and the team create a binder with all the important information. Mistaken belief: Now that it’s all decided, everyone will reference the binder and act differently.

- Being unclear and not taking the time to clarify the change; and therefore, being out of alignment about the why, what, how, and who. Result: each member of the leadership team says something different about what’s happening with the change process. This equates to chaos and mistrust.

- Focusing on the mechanics of the change or the impact to the bottom line without considering the human impact. Result: people feel disregarded and resist.

You’re lucky if people open and read the e-mail. And a binder—really? And, when leadership team members tell different versions, people further down the organizational chain talk and compare notes. Distrust grows, and people begin to worry. It’s like being in a family: if Mom and Dad contradict each other, the kids manipulate the situation to get their way.

How you communicate is just as important as what you communicate.

You need to make information accessible, understandable, and palatable. Here are four ways to effectively communicate:

- As a leadership team, make sure you are clear and aligned about the why, what, how, and who of the change. Then at the end of each leadership team meeting, identify exactly what you want people in the organization to know, versus what you want to keep within the leadership-team cone of confidentiality.

- Use the rumor mill. Every organization has break-room gossip, so why not use it? Once you have clarity on what to communicate, each leadership team member can actively communicate that message to his team. This works best if it happens face-to-face within twenty-four hours. If your business model doesn’t allow for that, do the best you can.

- Repeat the message in different venues, such as all-hands meetings, in company newsletters, or at social events such as picnics. It’s normal to assume that if you say something once, people will understand and just do it. But as in marketing, you need to communicate your key change messages six or seven times before people will pay attention to you, hear you, believe you, understand you, know how to behave differently, and change their behavior. Six or seven times! That’s a lot of repetition, but that’s what it takes.

- Tell stories. Humans absorb, learn, and are changed through story telling. Your people will learn more easily if you tell a story that depicts what it takes to make the change work, or if you share the impact this change will have, or has had, on a customer.

For example, if a consumer products company’s leadership team decided to change their target market and marketing strategies for one of their primary products, you might first think, “Just inform the marketing team.” But if that happened, marketing would make the changes, and people in other departments wouldn’t know why. People throughout the organization would wonder, worry, and make stuff up. The leadership team would appear not to know what they’re doing, or that they are working against each other.

Organizational communication needs to be broader and more integrated and led by each team member. It must be done over and over again, telling stories about why, and what it will look like when it’s done, how the company will get there and what role you want them to play.

When each member of leadership takes the time to communicate the appropriate changes to his team, everyone in the organization is on the same page. Issues surface and are addressed, and the leadership team looks to be in alignment, because they are! The company breathes a collective sigh of relief.

Change is hard. It is even harder when it feels like it is being done to you, and for many people in an organization that’s how it is taken. You, the leader, are way out in front of this change process, like the fastest runner in a marathon who is almost 20 percent done with the race when other people are just starting the race. You need to help your people move through the Valley of Despair. You and your leadership team need to be master communicators and story tellers to help your people become aware, digest, adopt, and in the best case, embrace the change. Remember, these are humans who are accustomed to doing things the old way. Let them know that you care and that they matter by supporting them through the change.

Did we mention that you have to repeat yourself?

Want to hear how big and small companies used the Path to Collective Creativity model to get to collective results? Read on.