CHAPTER ONE

Sweet Be the Bands

SPENSER AND THE SONNET OF A SSOCIATION

IN 1796, COLERIDGE FOUND that he had extra paper lying around at the printer’s office that he “could employ no other way,” so he resolved to “amuse [him]self” by compiling a little pamphlet of sonnets by Charlotte Smith, Robert Southey, Charles Lamb, and others.1 He prefaced his miniature anthology with a brief essay on the nature of the sonnet, which he defines succinctly as “a small poem, in which some lonely feeling is developed.”2 His definition typifies the Romantic association of lyric with individual subjectivity: the sonnet should be lonely because the proper subject of lyric is the individual mind, sequestered from political and social life so that it can meditate on itself.3 The definition also implies that there is some correlation between the smallness of the sonnet and its lonely subject. The sonnet is peculiarly suited for such lonely explorations of the self, Coleridge suggests, because its “limited form” allows the poem to “acquire, as it were, a totality” that mirrors the integrity of the mind.4

The tacit association of lyric’s formal circumscription with the secluded mind continues to inflect our understanding of the sonnet tradition that preceded Coleridge and to inform our evaluations about the merit and canonical status of individual sonnets and sonnet sequences. Critics, anthologists, and casual readers still gravitate toward sonnets that develop lonely feelings and overlook sonnets that, in G. K. Hunter’s language, “run counter to the ‘natural genius’ of the Elizabethan love sonnet” by subsuming the ego into a larger “pattern” rather than focusing on the “tensions of individualism.”5 Recent calls to historicize poetic form and reconsider the ways in which genres signified without the distorting lens of Romanticism should prompt us to look anew at the sonnet and to consider just how “natural” this reclusive “genius” of the genre actually is: did early modern sonneteers connect the sonnet’s limited form with the boundaries of the human mind, or did they have other ways of interpreting and utilizing the form’s circumscription?

To some extent, this association of the sonnet with loneliness is embedded within the early modern sonnet tradition itself. The outsized and enduring influence of a single Italian sonneteer and his reclusive temperament made seclusion a common characteristic of the sonnet centuries before Coleridge’s pronouncement. As Thomas Greene notes, Petrarch “was born deracinated,” and his relative lack of “attachments to a class, a place, and a community” helped foster a “rootless, self-questioning personality, half in love with and half perplexed by its reflexive inquisitions.”6 Petrarch displays his admiration for the life of seclusion in his Latin prose works De otio religioso and De vita solitaria, but his vision of a “Solo et pensoso” lover, who seemed to be perpetually wandering through deserted fields with only “Amor” to converse with him, proved far more influential.7 Indeed, Petrarch’s isolation is so extreme that we cannot be sure he ever propositions Laura in person or hears her speak directly to him within the world of the sequence.8 Like Romantic verse, Petrarch’s reflections on the inner life of a lonely lover have an implicit politics: they help forge an idea of “autarkic individualism” in which human beings are more dignified and free when they are abstracted from political and social allegiances.9 Petrarch’s English imitators often tempered the extremity of Petrarch’s solitude: Stella’s voice and the voices of well-meaning friends at times puncture Astrophil’s internal dialogue, and Shakespeare’s speaker generally addresses his two lovers directly. But, despite these significant alterations, Tudor sonneteers generally followed Petrarch in recording the vicissitudes of unsuccessful love affairs and representing minds driven inward by frustrated love.10

Writing at the height of the late Elizabethan sonnet craze, Spenser tests the conventional limits of the genre and interrogates the political implications of its dedication to the solitary individual. Indeed, his work in Amoretti and Epithalamion has something in common with the avant-garde antilyricism of the twentieth century. As a group of Language Poets did in 1988 in their manifesto “Aesthetic Tendency and the Politics of Poetry,” Spenser questions the prevailing view that “the maintenance of a marginal, isolated individualism” is “an heroic and transcendent project.”11 Yet he does so not by destabilizing the traditional narrative voice or by defending collective writing practices but by crafting a sonnet sequence that depicts the social integration rather than the isolation of the individual. As the diminutive title of his 1595 sonnet sequence Amoretti indicates, Spenser, like Coleridge, saw smallness as a fundamental characteristic of the sonnet, but, in his sonnets tracing a courtship that culminates in matrimony, Spenser makes the case that the circumscribed form of the sonnet is as suitable for reflections on the ties that bind human beings as it is for meditations on the deracinated mind. In converting the sonnet into a sociable genre, Spenser modifies its formal conventions accordingly, inventing his own interlocking rhyme scheme and adopting modes of address that advance his vision of mutual captivity. These revisions aid him as he inverts the Petrarchan paradigm by depicting a lover who is gradually driven out of, rather than into, himself. As Amoretti opens, both the speaker and the lady are engaged in the enterprise of the Coleridgean sonneteer—they are developing, perhaps even nursing, their lonely feelings. But Spenser’s opening sonnets reveal that inordinate self-examination fosters the base passions that he believes subdue the fallen human mind, including lust and “self-pleasing pride.”12 Spenser contends that fellowship in general and the marriage bond in particular provide a remedy for the pitfalls of solipsism. Through his account of courtship and marriage, Spenser makes the case that artificial and restrictive “bands”—a term Elizabethans used to describe marriage and political obligations as well as rhyme—are essential to the establishment of all order, beauty, and community since they rein in unruly passions while allowing humanity’s higher nature to flourish. Spenser shares his belief that the formation of societies requires individuals to relinquish a certain amount of sovereignty with many of his Elizabethan contemporaries. But in Amoretti and Epithalamion Spenser presents a distinctive account of human association that heightens the role of restraint in the formation of human bonds. After considering the merits of a contractual account of marriage and society, Spenser reveals that contract is insufficient to “knit the knot that ever shall remain” (SP, 6.14). Instead, he indicates that an enduring union requires both parties to sacrifice life and liberty in order to obtain a mysterious state of happiness within captive bonds.

The Bond of Association

I have chosen to describe Spenser’s love poems as sonnets of “association” because the noun implies both the action of uniting and the union that is the product of that action. In his poetry, Spenser meditates on both existing social institutions and their genesis, but he is predominantly interested in the latter. Indeed, the sonnet of association is the culmination of a poetic career in which Spenser repeatedly represents the human struggle to convert isolation into attachment. Throughout his career, Spenser chose genres that allowed him to consider the interactions of individuals in a natural or pseudonatural state: pastoral and romance. And he begins his two major works in these genres, The Shepheardes Calender and The Faerie Queene, with figures who are detached from their surroundings and from one another before proceeding to explore whether and how they can be brought together. Although both his pastoral and romantic worlds are characterized by a dense web of social interactions, he tends to focus on the relations between pairs of individuals—Cuddie and Thenot, Redcrosse and Una, Britomart and Artegall—because these small units of society allow the poet to lay bare the mechanics of social interaction in their most elemental form.13

In Spenser’s romantic poetry love is in fact love, but it is also politics. Because Spenser advertises his complex relations with the queen and incorporates topical allusions into his poetry, his verse has always invited political interpretations, and he was particularly favored as an object of new historicist criticism.14 But, to some extent, critical fascination with court intrigue, colonial power, and, above all, Elizabeth herself has distracted from the ways in which Spenser’s poetry is political in the broader sense of the term: it attempts to uncover the origins and ends of social formations. Spenser does not neglect the dynamics of homosocial interaction, but the emotional center of both The Faerie Queene and his minor works seems to be the bonds between “Knights and Ladies,” perhaps because Spenser thinks, like Edwardian counselor and political theorist Sir Thomas Smith, that “the naturalest and first coniunction of two toward the making of a further societie of continuance is of the husband & of the wife.”15 Smith is drawing on Aristotle’s description of the union between “male and female” at the beginning of the Politics; Aristotle argues that this conjunction “is formed not of deliberate purpose, but because, in common with other animals and with plants, mankind have a natural desire to leave behind them an image of themselves.”16 Because Smith follows Aristotle in seeing the family and its hierarchy as natural, he does not discuss how this “naturalest and first coniunction” is formed: he takes it for granted that the “societie of man, and woman” already exists in nature, and he carries on to describe how the labor and power are divided among men and women.17 French political theorist Jean Bodin, whose Les Six livres de la Republique was published in 1576, places a similar emphasis on marriage and the family as the “true seminarie and beginning of euery Commonweale” but also treats the family as something that already exists.18 Indeed, Bodin takes Aristotle and Xenophon to task for separating “the Oeconomical government from the political” and argues that good government in the family is the building block and “true model” of good government in the city.19 In depicting marriage and the family as the elementary units of political life without inspecting the origins of this conjunction itself, Smith and Bodin choose to depict the order and hierarchy of the family as natural and therefore as a solid and unchangeable foundation for political order. Though Spenser does seem to see the marriage bond as the root of social life, he is far from believing that the formation of this bond is natural or easy. In his sonnets of courtship, Spenser endeavors to explore the making of this first conjunction and begins his account of association with two completely isolated individuals rather than a preexisting family. Indeed, although his marriage to Elizabeth Boyle doubtless involved complex negotiations with her relatives and friends, Spenser eliminates all other social interactions in order to focus on the pair of lovers, whom he depicts as warriors facing each other in a state of nature.20 Because Spenser focuses on the lovers alone and speaks about them in his characteristic figurative manner, the lovers become what Peter Cummings describes as an “allegory” of all lovers.21 But by repeatedly comparing the lovers to hostile warriors endeavoring to form a league and by playing with tropes of liberty and captivity, Spenser indicates that the sequence is also an allegory of all human bonds: the way in which his lovers negotiate the relation between freedom and restraint has ramifications not only for all other lovers, but for all other social associations. And Spenser suggests through his warring lovers that the marital “association” does not have the fixed meaning or natural stability that Smith and Bodin attribute to it. The lovers do not have a settled or shared understanding of what it means to unite themselves but must work it out in the midst of their battle. The conjunction of two that forms the basis of the polity is not natural and established but artificial and hard won.

In addition to describing both the process and product of social combination, the word “association” is particularly appropriate to Spenser because it captures the dynamic interplay between consent and constraint that animates his accounts of love and social life. At the beginning of book 3 of The Faerie Queene, Britomart lays down a fundamental premise of the book, and of Spenser’s work more generally, when she insists that “loue” may not “be compeld by maistery” (FQ, 3.1.25). Elizabeth Fowler has argued that Spenser’s interest in the idea that the “marriage contract” and “sexual consent” are “constitutive of the polity” was long-standing since the “episode of the marriage of Thames and Medway,” which may have been one of the earliest portions of The Faerie Queene Spenser conceived, “ceremoniously asserts the voluntary contractual and reciprocal basis” of the polity.22 In Amoretti, Spenser also depicts the league formed between the lovers as consensual and contractual; indeed, he famously describes the lady as “tyed” “with her own goodwill” in the betrothal sonnet that culminates the first stage of courtship. But he also questions the contractual model throughout the sequence and considers whether other metaphors and models might better capture his sense that social bonds curtail and thwart the individual will as much as they fulfill that will’s longing for union.

The subtleties of Spenser’s understanding of the interplay of consent and constraint in the process of association are illuminated by considering Richard Hooker’s complex use of the word “association” in the first book of Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, which was published in 1593, a year before Spenser’s marriage to Elizabeth Boyle. Hooker connects the words “associate” and “association” with voluntary combination when he describes the church as a “supernaturall societie” in which “wee associate our selues.” Although the church differs from human societies in that it is a union of “holy men” rather than “men simply considered as men,” Hooker maintains that “it hath the selfe same original grounds which other politique societies haue, namely the naturall inclination which all men haue vnto sociable life, and consent to some certaine bond of association, which bond is the law that appointeth what kind of order they shall be associated in.”23 Hooker’s slow-building prose style allows for a potential equivocation in the key phrase “bond of association.” Since the term follows Hooker’s remarks on humanity’s innate inclination to social life, it initially appears that the “bond of association” simply refers to the natural bonds that unite individuals. But the dependent clause reveals that the “bond of association” is actually an artificial instrument of constraint, a positive law that imposes order by binding citizens to a particular form of government.24 The natural bond that brings them together is translated into an artificial bond that holds them to an order.

The double meaning of “bond of association” captures the twofold foundation of Hooker’s political philosophy. His understanding of secular and ecclesiastical politics is thoroughly imbued with the Aristotelian view that “by nature . . . a man is a civill and sociable creature.”25 But, as Alexander Rosenthal argued in his study of the origins of constitutionalism, Hooker does not think that natural social inclinations are sufficient grounds for the formation of a functioning commonwealth. In a fallen world in which sin distorts and destabilizes sociability, the artifice of a consensual covenant is required to constitute and maintain civil society.26 This “bond” both fulfills and thwarts the inclinations of “natural man”: it satisfies human beings’ fervent desires for union while restraining the disruptive passions that impede harmony.

In his tales of lovers struggling to “eternally bind” the “lovely band” of matrimony, Spenser reveals that he, like Hooker, adheres to an Aristotelian view of human sociability in which artifice must supplement instinct (SP, Epithalamion 396). His knights and ladies display an unmistakable proclivity for social life and seem to long with every fiber of their beings to unite themselves to one another.27 As Yeats puts it in his preface to a 1902 volume of Spenser’s poetry, even when Spenser describes the stately pageants and houses that are the trappings of his official morality, “all the while he is thinking of nothing but lovers whose bodies are quivering with the memory or the hope of long embraces.”28 Although Yeats may exaggerate Spenser’s sensuality and underestimate the significance of Spenser’s morality, his statement underscores the fact that overwhelming desire for union is the motive force of Spenser’s characters and his poems. But, despite his keen awareness of humanity’s social inclinations, Spenser has less confidence than Hooker that these natural instincts can lead to lasting unions. Although he carefully considers a contractual account of association of the kind advocated by Hooker, in the end Spenser concludes that human beings require more coercive and unnatural bonds.

The Bands of Rhyme

In order to understand fully the social theory that Spenser promulgates in his sonnet sequence, we must attend not only to the complex negotiations recorded in the poems, but to their formal features, which reproduce, further, and shape the social lessons of Spenser’s verse.29 As their frequent use of the myths of Orpheus and Amphion suggests, the Elizabethans saw a connection between founding cities or nations and ordering language through verse.30 Indeed, Spenser famously uses the language of political conquest to describe his vision of versification in his earliest extant pronouncements on verse, his letters to Gabriel Harvey on quantitative meter, which Henry Bynneman printed in 1580 as Three proper, and wittie, familiar letters: lately passed betweene tvvo vniuersitie men: touching the earthquake in Aprill Last, and our English refourmed versifying. As the loaded past participle in the title indicates, Spenser and Harvey saw an urgent need to “reform” English verse to bring it in line with a newly reformed English church and commonwealth. In their letters, Spenser and Harvey reveal that they have become “more in loue wyth . . . Englishe Versifying, than with Ryming” precisely because they desire the “artificial straightnesse” of quantitative meter. As Harvey puts it, their “new famous enterprise” is the “Exchanging of Barbarous and Balductum Rymes with Artificial Uerses.”31

Although both Spenser and his former tutor agree that English verse has been allowed to develop in a helter-skelter manner for far too long and that they must organize the muddled language by imposing an artificial order on it, the two writers disagree about the extent to which this artificial program of English versification should accommodate the natural state of the English tongue. After discussing English words that are difficult to assimilate into the system of quantitative measure, Spenser concludes that the war against a recalcitrant tongue “is to be wonne with Custome, and rough words must be subdued with Vse.”32 As Richard Helgerson has argued, Spenser expresses a desire to “remake” the English language in the image of the classical tongues, and he is perfectly comfortable using the “language of sovereign power eager to subdue rough words and have the kingdom of them” to describe his linguistic project.33 In contrast to Spenser, Harvey appeals to common usage, insisting that in “bring[ing] our Language into Arte” grammarians must ensure that the artificial order is “in all pointes conformable and proportionate to our COMMON NATURAL PROSODYE.”34 Harvey imagines nature and art on a continuum and suggests that natural language can be gently taken by the hand and led into orderliness, which can be “conformable” to nature, but Spenser sees a gulf between the current barbarism of the tongue and the civilized poetic language he envisions.35 Only the violent imposition of rule will bring order. Although Spenser’s flirtation with quantitative meters proved short-lived, he did not abandon his aspiration to bend and shape the English language to his will. Instead, he embraced rhyme as an alternative instrument of restraint.36

Although Harvey preserved Spenser’s youthful meditations on poetic form for posterity by printing Three proper, and wittie, familiar letters, Spenser’s later views on rhyme and meter must be extrapolated from his works themselves since no treatise on his poetic theory survives. In the argument to “October” in The Shepheardes Calender, Spenser’s (likely fictional) commentator E.K. suggests that such a treatise once existed. He notes that the new poet discourses on poetic inspiration “els where at large . . . in his booke called the English Poete, which booke being lately come into my hands, I mynde also by Gods grace upon further advisement to publish.”37 This is a tantalizing remark for historians of poetics—did this lost work contain an account of Spenser’s fundamental poetic principles in the manner of Sidney’s Defence and Puttenham’s Arte? It is uncertain whether the work really existed and was “looselie scattered abroad” in manuscript and subsequently lost like Spenser’s poem The Dying Pellican, or whether the teasing allusion is one of E.K.’s many waggish misdirections.38 But the provocative possibility of a lost prose treatise should not distract from the fact that we can uncover considerable information about the development of Spenser’s prosodic views by charting the poetic forms that he used over the course of his thirty-year poetic career. Chronological analysis of Spenser’s verse forms reveals an intriguing movement toward stanzaic poems with intricately interwoven rhyme patterns. In his works of the 1560s and 1570s, Spenser used blank verse and couplets alongside interwoven forms. When Jan Van der Noot commissioned Spenser to translate French, Italian, and Flemish verse into English in A Theatre wherein be represented as wel the miseries and calamities that follow the voluptuous Worldlings (1569), Spenser composed his translations in blank verse as well as in rhyme. He wrote his Chaucerian beast fable Mother Hubberds Tale (composed c. 1579) in iambic pentameter couplets, and he used couplets and a rough four-beat accentual meter for three of the twelve eclogues in The Shepheardes Calender (1579). Indeed, in his appreciation of rudeness and roughness in general and of the Chaucerian couplet in particular, the young Spenser of the 1560s and 1570s in many ways anticipates the couplet poets of the 1590s I discuss in chapter 2.39 But after 1580, when he went to Ireland as private secretary to Lord Grey, who became Lord Deputy of Ireland in that year, Spenser turned his back on blank verse and couplets altogether.40 Indeed, his conversion was so complete that he even retranslated his translations of Du Bellay from A Theatre into traditional English sonnets sometime before they were published in a 1591 compilation of his minor verse, Complaints. Containing sundrie small Poemes of the Worlds Vanitie.

Spenser continued to experiment with verse forms until the premature end of his career, but all his poetic experiments printed in the 1590s share distinctive characteristics: with the exception of Colin Clouts Come Home Again, which has a complex but nonstanzaic rhyme pattern, all of Spenser’s late works are stanzaic, have interlocking or alternating rhyme schemes, and conclude with the chime of a couplet. Even Spenser’s most complex and distinctive poetic configurations—the seventeen- to nineteen-line stanzas of Epithalamion and Prothalamion—adhere to this basic pattern. The fact that Spenser knowingly rejected continuous couplets and continued to produce variations on the same poetic theme throughout the second half of this career suggests that he found this form congenial not only to his particular habit of mind but also to his cosmic and social thought.41

The most important resource for interpreting Spenserian poetics is of course his poetry itself, in which he not only offers explicit meditations on the poetic enterprise but provides more general reflections on the benefits of artificial restriction that illuminate his preference for interwoven rhyme. But contemporary defenses of poetry and prosodic manuals like those by Gascoigne, Sidney, Puttenham, and Webbe can also help guide interpretations of Spenser by providing a small sample of the ways that Elizabethan readers interpreted complex rhyme patterns. In his Arte of English Poesie, published in 1589, George Puttenham offers more extensive and detailed analysis of what he calls “proportion poetical” than any other writer of the period. His analysis of rhyme patterns is particularly useful in interpreting Spenser’s corpus since he, like Spenser, displays a decided preference for interwoven stanzas (Arte, K1r). Puttenham defends his preference by arguing that rhymes actually contribute to the solidity of a stanza. In his discussion of the “Situation of the concords,” or the placement of rhymes, Puttenham offers guidance about how to craft a stanza that is “fast and not loose” (Arte, M2v). The secret to the firmly fixed stanza is what Puttenham calls “band,” a term that he draws from the craft of masonry (Arte, M3r).42 We can see “in buildings of stone or bricke,” he notes, that the mason “giueth a band, that is, a length to two breadths, & vpon necessitie diuers other sort of bands to hold in the worke faste and maintaine the perpendicularitie of the wall” (Arte, M3r). In other words, the bricklayer does not just stack one brick directly on top of the other but finds a way of laying them in an alternating pattern so that the wall is more stable and does not fall to the ground. Similarly, the poet’s stanza will “fall asunder” if he does not take care to “close and make band” through the proper placement of like and unlike sounds (Arte, M3r). Puttenham’s comparison to the trade of bricklaying not only renders the nebulous idea of poetic proportion concrete and tangible; it also raises the stakes of rhyme’s linking function, making it the principle of a poem’s structural integrity. If the poet fails to use rhyme properly, all his work will be for naught since his stanza will crumble to pieces.

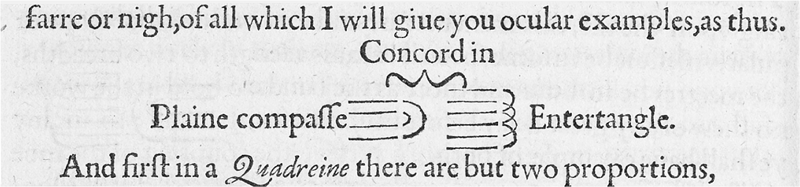

Puttenham maintains that the poetic craftsman can preserve the structural integrity of the stanza only by using “intangled” rhyme, by “enterweaving one with another by knots, or as it were by band” (Arte, M2v). He provides one of his “ocular example[s]” in order to illustrate the distinction between this “entertangle” rhyme and what he calls “concord in plaine compasse” (Arte, M2v; see figure 1.1). The image makes it clear that “entertangle” is equivalent to alternating rhyme while “plaine compass” is equivalent to enclosed or envelope rhyme. The fact that Puttenham uses these “ocular example[s]” instead of the alphabetical notation we now use to represent rhyme patterns has a significant bearing on his understanding of rhyme’s function. While alphabetical notation draws attention to the scheme or pattern created by rhyme, Puttenham’s method of drawing links between lines with like endings draws attention to the connective function of rhyme, its ability to recall the ear to an earlier moment in the stanza and hence to tie together disparate sections of the poem.43

FIGURE 1.1. Detail from Puttenham, George. The Arte of English Poesie. London: Richard Field, 1589. Pforz 12 PFZ. Carl H. Pforzheimer Library, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Puttenham has confidence that his images straightforwardly represent the aural links produced by the sound of like endings since he maintains that “there is a natural simpathie, betweene the eare and the eye” and therefore “most times your occular proportion doeth declare the nature of the audible” (Arte, M1v). Thus, the lack of intersections or “knots” in the illustration of “plain compass” plainly demonstrates the shortcomings of this form, which does not sufficiently tie together the stanza. Because the sound of the second rhyme returns again “so nye and so suddenly,” it is never “out of the eare” and immediately satisfies the listener’s desire for closure (Arte, M2r). This instant gratification makes the couplet the “most vulgar proportion” since any “rude and popular eare” can detect and delight in it (Arte, M2r). Puttenham’s disdain for the instantaneous chime of the couplet even extends to concluding couplets, for he maintains “Chaucer and others” do “a misse” by “shut[ting] up the staffe with a disticke, concording with none other verse that went before, and mak[ing] but a loose rhyme” (Arte, M3r). Though the sound of the couplet might satisfy the vulgar ear, the poet who indulges in concluding distichs risks undermining the structural integrity of his poem as the loose, unbanded couplet can simply fall off the end of the stanza. In contrast to the loose and vulgar couplet, complex entertangle rhyme requires both a skillful artificer and a “learned” audience: the poet “sheweth him selfe more cunning” and demonstrates that he has “his owne language at will” by finding multiple rhymes for a single word, and the auditors exercise their ears by holding multiple endings in suspension for a time—though the poet should never make them wait so long “that the eare by loosing his concord is not satisfied” (Arte, M2r, M3r). Thus, poems that interweave rhymes at a distance of two or three lines achieve the delicate balance between suspense and satisfaction required to maximize delight, harmony, and artfulness.

Puttenham’s involved account of “plaine compasse” and entertangle rhyme reveals much about his understanding of the aims and methods of poetic composition. He maintains that the English language must be “fashioned and reduced into a method of rules & precepts” in the manner of the Greeks and Latins (Arte, C2r). This vision of the necessity of linguistic conquest derives from his larger understanding of the relationship between art and nature, which he expresses through the myths of Amphion and Orpheus. Puttenham presents a dark vision of humanity in a state of nature: they were “vagarant and dispersed like the wild beasts, lawlesse and naked, or verie ill clad” until the intervention of poetic lawgivers, who managed to “hold and containe the people in order and duety” (Arte, C2r–v). Puttenham’s vision of the state of nature likely draws on Cicero’s account in De Inventione. Indeed, his descriptions of prepolitical humanity as “vagarant” and “dispersed like the wild beasts” echo the language of Cicero’s own account of the ancient world, when “homines passim bestiarum modo vagabuntur,” men wandered here and there in the manner of beasts, and were “dispersos . . . in agros et in tectis silvestribus abditos,” dispersed in the fields and hidden under sylvan roofs.44 But, intriguingly, Puttenham’s language is also a direct translation of Machiavelli’s statement in the Discourses that at the beginning of the world men lived “dispersi, a similitudine delle bestie.”45 For Machiavelli, this dispersed, beastlike state came to an end when the world became more crowded and men chose robust and strong-hearted leaders to defend themselves. Puttenham, in contrast, takes a more Ciceronian approach and credits poets with taming beast-like humanity with “sweete and eloquent perswasion” (Arte, C2v). Yet Cicero, Machiavelli, and Puttenham are alike in questioning the Aristotelian premise that sociability is natural. Civil life is hard won and requires the few to manage the naturally unruly instincts of the rest through force or persuasion. Indeed, Machiavelli goes onto conclude that “men act right only upon compulsion; but from the moment they have the option and liberty to commit wrong with impunity, then they never fail to carry confusion and disorder everywhere.”46 In his writings of the 1590s, Spenser stands somewhere between Aristotle and Machiavelli. As I have suggested, the forces that stir his shepherds, knights, ladies, and sonneteers to set out on their quests are love and the desire for union. And he maintains throughout his poetry that gentleness, civility, and courtesy are “planted naturall” in at least some individuals (FQ, 6.1.2). But, inside these individuals as well as in the wider world, these courteous instincts are always jostling with a swarm of equally natural antisocial forces that threaten to thwart political life. Spenser’s fears about these forces often lead him to defend root-level reformation in which natural beastliness is subdued by the bonds of art. This instinct for radically remaking nature was present in Spenser’s work before he left for Ireland—it informed his longing to reform English prosody during his flirtation with quantitative meter—but it is most visible in the extreme cruelty of the approach to Ireland he advocated in his Vewe of the Presente State of Ireland. In the tract, which was likely written a few years after Spenser’s marriage to Elizabeth Boyle but was not published until 1633, the interlocutors in Spenser’s dialogue begin by asking what is necessary for “reducing that salvage nacion to better government and Cyvilitye” and conclude that the nation is in such an unruly state that it will be necessary to “new fram[e]” it “in the forge” and “alter the whole form of governement” by means of the sword.47 The interlocutors in Spenser’s dialogue convince themselves of the need for the alteration of form and frame with much reluctance and debate and depict this reformation as an extreme response to a peculiar legal, customary, and military situation in Ireland, but underneath all the debates about the best “plot” for “reformacion” there is the consistent suggestion that the natural state of human beings without “discipline” is “licentious barbarism” and “lewd libertie” in which the passions run wild.48 Early in the dialogue, Irenius compares the Irish to “colt[s]” that were broken but then allowed to “rune loose at random”; once they “shoke of theire bridles,” he charges, they “began to Colte anewe more licentiouslye then before.”49 Spenser’s depiction of English intervention as an effort to rein in natural coltishness and impose civility through discipline was certainly a self-serving colonial fiction. His efforts to defend what he saw as his plot of ground in Ireland required considerable legal, and likely physical, wrangling. In 1589, his Old English neighbor Lord Roche wrote to Walsingham to accuse Spenser of “falsely pretending title to certain castles and ploughlands” and of “threatening and menacing the said Lord Roche’s tenants,” “seizing their cattle,” and “beating Lord Roche’s servants and bailiffs”; Spenser in turn accused Lord Roche of being a “traitor,” imprisoning Spenser’s “men,” killing the “fat beef” of people who housed Spenser, and speaking contemptuously of the queen and her laws.50 Whatever the reality that lies behind these mutual recriminations, it is clear that Spenser’s residence in Ireland was far from peaceful and that he wanted to see all violence and repression on the part of the New English as efforts to defend civilization against barbarism.51 But if Spenser’s experience in Ireland deepened his suspicion of nature and his embrace of artificial bands, it did so across the board. He did not simply depict the Irish as the licentious, natural other but increasingly emphasized the naturally unruliness that threatens to undermine all civil life. Spenser’s deepening suspicion of natural liberty is most visible in Amoretti, where the sonneteer and his lady are themselves portrayed as licentious colts that repeatedly revolt against the “bridle” of the marriage bond.

I see Spenser’s turn to what we now view as his characteristic prosodic forms—the Spenserian stanza, the Spenserian sonnet, and the long interwoven rhyme patterns of his marriage odes—as directly tied to his growing belief that the containment of licentious natural instincts is the aim of both social and poetic artifice. It is telling that Puttenham’s vision of vagrant and dispersed nature led him to a similar poetic remedy. Although he discusses other methods of organizing language, Puttenham makes the case that entertangle rhyme is the English poet’s most effective instrument of discipline. In seeing rhyme as a way of bringing order and civility to English verse, Puttenham and Spenser were working against its reputation during the quantitative controversy as primitive, customary, and artless. With modifications, the “olde vse of toying in Rymes” could become a new way of reframing and civilizing the English tongue.52 Stanzaic rhyme, especially the elaborately interwoven rhymes Puttenham and Spenser prefer, could provide the kind of artificiality and measure sought by advocates of quantitative verse.

While Puttenham’s treatise provides a detailed theory of the aims of poetry and the effects of formal decisions that may illuminate Spenser’s prosodic choices, William Webbe’s 1586 Discourse of English Poetrie offers more direct evidence about contemporary understanding of Spenser’s verse since it contains a meticulous prosodic analysis of The Shepheardes Calender. Webbe sees a wealth of poetical instruction in the Calender. In fact, he uses the poem as a rubric for his own directory of verse forms. Since there are “in that worke twelue or thirteene sundry sorts of verses which differ eyther in length or ryme o[r] destinction of the staues,” he decides that a survey of the eclogues will “serue” to introduce readers to the principal “sortes of verses” available to the English poet.53 Webbe’s analysis of each eclogue includes an account of the number of syllables in each verse and of the rhyme pattern, followed by an explanation of how these poetic features are particularly “agreeable” to the “affections” expressed in that eclogue. His lengthy explanations of the poetic features of the eclogues often seem unnecessarily tortuous. The most extreme example is his account of the “March” stanza: “The third kynd is a pretty rounde verse, running currantly together, commonly seauen sillables or sometime eyght in one verse, as many in the next, both ryming together: euery two hauing one the like verse after them, but of rounder wordes, and two of them likewyse ryming mutually.”54 It would certainly have been simpler to state that the stanza rhymes AABCCB, but Webbe’s befuddling description reveals much more about his understanding of verse than such a technical schema could capture. Like Puttenham’s ocular examples, phrases like “running currantly together,” “hauing one the like verse after them,” and “likewyse ryming mutually” indicate Webbe’s interest in the pattern of resemblances and interconnections among lines of verse, in the ways in which a poet can fashion a single “rounde” whole out of an assemblage of lines by carefully interweaving like and unlike. The socially inflected word “mutually” is particularly intriguing, and an investigation of Webbe’s use of the word in the rest of the treatise indicates that he always applies the adverb to lines that rhyme across a distance, or “mutuallie crosse” as he puts it at one point, in this case the tail rhyme in the March stanza. This term—which, as far as I can tell, is unique to Webbe—perfectly suits a pastoral poem in which many of the songs are, as Webbe observes, “mutuallie sung betweene two.”55

Indeed, whether wittingly or no, Webbe seems to have drawn out a connection between the rhyme scheme and the argument of the Calender that illuminates Spenser’s movement toward interlocking rhyme. For the eclogues that contain these “mutual,” interlocking rhymes are precisely those that depict the struggle for human association and the ways that it can be won out of sorrow and strife.56 In contrast, Spenser reserves couplets and rough accentual meter for those dialogues that present a dark vision of the fallen world in which permanent and irresolvable difference thwarts the human desire for fellowship. E.K. classes all three couplet dialogues (February, May, and September) as “Moral” in the general argument, remarking that they “for the most part be mixed with some Satyrical bitternesse.”57 Spenser’s couplet dialogues present a world that is so out of joint that no amount of human artifice can set it right. Thus, it is appropriate that the estranged interlocutors in these dialogues can speak only in couplets—they fail to “make band” with each other, and their speech falls asunder into detached units. In the distichic dialogues of the Calender, Spenser confronts the limits of poetry’s ability to “hold and containe the people in order and duety” (Arte, C2r–v). Although he frequently returns to the antisocial themes of these dialogues, he never returns to continuous couplets. Instead, he opts for a poetic form that suggests that even the most recalcitrant and antisocial of elements can be incorporated into the artist’s orderly pattern.

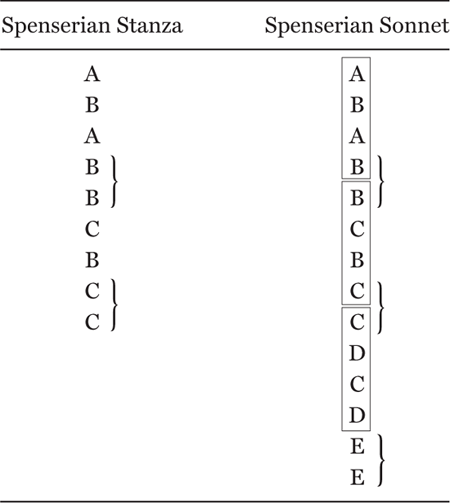

In their verbose accounts of English rhyme, Puttenham and Webbe suggest potential interpretations of Spenser’s penchant for interlocking rhyme that must be tested against his verse practice. Both stress rhyme’s role as a connective force that unifies the poem. While Webbe describes rhyme as a kind of sociability, Puttenham maintains that such unification can be achieved only with an element of coercion. For Puttenham, the artificial “bands” of rhyme, like the “bond of association,” both satisfy and limit natural inclinations. Although Puttenham’s general views about the binding function of rhyme can be fruitfully applied to Spenser’s corpus, Spenser does not follow Puttenham in all the latter’s poetic preferences. In particular, Spenser does not share Puttenham’s categorical opposition to the use of couplet rhymes within an interwoven stanza or his objection to the Chaucerian concluding couplet. Spenser’s Faerie Queene stanza, which rhymes ABABBCBCC, contains couplets in the middle and at the end, but each of the couplets in the stanza is linked to an earlier rhyme, allowing Spenser to combine the connective function of entertangle rhyme with the benefits of the couplet. Clare Kinney and Jeff Dolven have analyzed the effects of the couplets woven into the Spenserian stanza in detail. Kinney describes the B rhymes in the middle of the stanza as a “pivot about which the stanza doubles back on itself,” and Dolven similarly argues that the central couplet of the stanza allows a “double-take in the middest,” a moment of reflection that Spenser uses for both “disruption” and “closure.”58 For Dolven, the final couplet, with its concluding alexandrine line, serves a different function: it is “reflective, summary, or even epigrammatic,” offering a “moment of provisional rest” in a “poem so wary of rest.”59 It would seem that these insights about the couplets within the Spenserian stanza could simply be applied to the Spenserian sonnet, which appears to be a mere extension of the Spenserian form from nine to fourteen lines. But there are two differences between the stanza and the sonnet that complicate any easy correlation of the two (see table 1.1). First, Spenser strictly follows sonnet convention in making each of his quatrains discrete syntactical units. The clear indentation of the sonnets in Ponsonby’s original edition accentuates the separation of the quatrains, making the verse units perceptible even to an inattentive reader. As a result of Spenser’s strict adherence to the quatrain as a unit of sense in his sonnets, the couplets formed between these quatrains do not function in the same way as the middle couplet of the Spenserian stanza. Instead of providing a moment of meditation in the midst of the poem, they serve the same function as the conjunctions—and, but, so, for—that Spenser habitually uses to connect quatrains: they forcibly yoke together distinct ideas and syntactical units.60 Because these couplets are required to do more connective work than those in the Faerie Queene stanza, they draw attention to the labor and strain involved in the poet’s task of wrestling his recalcitrant words into a single, unified whole.

Table 1.1

The Spenserian sonnet also differs from the Spenserian stanza because the final couplet of the sonnet is not linked to the body of the poem. As in the traditional English sonnet, the couplet stands completely alone. Like those of The Faerie Queene, these final couplets are often sententious and recapitulative, but the fact that they do not rhyme with the body of the sonnet advances the account of union Spenser provides in the Amoretti. Spenser often uses the disconnected couplet to address the lady directly and signal the precariousness of both courtship and the poetic enterprise, which depend on her reception of the sonnets. The poet’s artfulness can carry him only so far in courtship since his attempts to bind the couple in the bands of matrimony require that the lady assent to his proposal and respond in kind. The loose couplet of the Spenserian sonnet also portends the fact that the association between the poet and the lady will not be realized within the confines of the sequence. In order to complete the union, Spenser introduces a new poetic feature—the refrain—in Epithalamion. Thus, Spenser crafted his peculiar sonnet form to draw attention to the connective function of rhyme and hence to the laborious effort required to gain kingdom over a barbarous and balductum language. Spenser’s efforts to highlight the artificial straightness of verse through his rhyme pattern reflect his larger purpose in the sonnet sequence: examining the ways that naturally isolated individuals can become bound to one another.

Love’s Soft Bands in Amoretti and Epithalamion

In contrast to Petrarch’s sonnet sequence, which advertises its fragmentary nature and resists attempts to construct a seamless narrative, Amoretti has a more legible narrative structure, recounting the story of a successful courtship from the moment the lady begins to “entertaine” this “new loue” to the trying period of separation that follows betrothal (SP, 4.14).61 Within Amoretti’s complex account of the vicissitudes of courtship and betrothal, we can demarcate several distinct stages in the process of association. When the sequence and the courtship begin, the lovers are depicted as hostile warriors who exist in a sort of romantic state of nature: their desire for society is outweighed by their fear and alienation.62 The speaker attempts to remedy this state of fear by proposing that the two enter into a limited contractual bond that will allow them to form an association without giving up their freedom (Sonnet 12). But this contractual logic proves insufficient to bind the lovers in a lasting band and, when he is involuntarily taken captive by the lady (Sonnet 12), the lover discovers that self-yielding and captivity are the proper path to enduring fellowship. After he makes this discovery and yields himself to the lady (Sonnets 29, 42), the lover must then convince her to take a similar risk, which she at length does in the well-known betrothal sonnet (Sonnet 67). Just as in matters of form, in his theory of marriage and society Spenser seems to be moving in the opposite direction from his contemporaries, who were embracing contractual accounts of marriage and, increasingly, of political institutions.63 Spenser likely knew that the arguments of the foremost contractual theorist of his day, George Buchanan, led to the position that the social contract can be revoked when the monarch does not uphold his or her end of the bargain.64 Decades later, Milton would not only apply this argument to the English monarchy, but extend it to the marriage contract.65 Wary of the threat this contractual logic posed to the stability of marriage and society, in Amoretti and Epithalamion Spenser seeks to go beyond contractualism and form an indissoluble bond between the lover and the lady.

THE WEARY WAR: LOVERS IN A STATE OF NATURE

From the opening lines of Amoretti, Spenser indicates that his lovers have a natural inclination to sociable life but reveals that mutual wariness and fear predominate over mutual longing for the “soules long lacked foode” (SP, 1.12). This tension is visible in the opening quatrain of Sonnet 1, in which the poet alternates between desire and fear as he addresses the “leaves” that contain his verses:

Happy ye leaves, when as those lilly hands,

which hold my life in their dead doing might

shall handle you and hold in loves soft bands,

lyke captives trembling at the victors sight. (SP, 1.1–4)

The sanguine first and third lines form a complete thought without the dependent clauses of the second and fourth lines: “Happy ye leaves, when as those lilly hands, / . . . shall handle you and hold in loves soft bands.” In these lines, happiness consists not in amorous conquest, but in being held and restrained by the beloved. Though the “bands” of love may be soft and the lady’s hands as delicate as a lily, they are agents of captivity and restriction nonetheless. These rhyming instruments of constraint will return throughout the sonnet sequence and again in a culminating moment of the marriage in Epithalamion, when the lady gives her “hand” as “The pledge of all our band” (SP, 238, 239). But at this point the outcome of the courtship is far from certain, so the language of captivity seems far more sinister. The interwoven second and fourth lines express the lover’s anxiety about his captivity and set the tone for a sequence that depicts courtship as a terrifying and dangerous enterprise. For in order to win the lady’s grace, the speaker must make himself vulnerable to her “dead doing might” by yielding his inner thoughts to her as captives in war. In disclosing the contents of his “harts close bleeding book,” the lover puts himself at the mercy of the lady’s judgment and risks her displeasure (SP, 1.8). Spenser’s speaker acknowledges from the outset the very real possibility that the lady’s “lamping eyes” will “reade the sorrowes” of his heart and nevertheless refuse to grant him grace (SP, 1.6, 7). The lover trembles at this prospect because he has already committed himself to her service: if the lady does not reciprocate, then the “soft bands” of mutual affection can easily become the hard fetters of unrequited love. Because we know that Amoretti culminates in betrothal, it is easy to overlook the uncertainties of its first sonnet, but the vulnerability and fearfulness of Spenser’s speaker lays the foundation for the sequence’s account of the painful process of association.

Spenser’s desire to present alienation and trepidation as the natural state of human beings before the intervention of artifice accounts for a group of sonnets that have consistently puzzled critics. Expanding on the Petrarchan trope of the dolce guerrera (sweet warrior), Spenser composed a remarkable number of sonnets, fifteen to be precise, that depict the lady as a warrior or wild beast with which the speaker must battle.66 These sonnets all occur in the first half of the sequence, before the betrothal sonnet, and, though there is a concentration of war imagery in Sonnets 10–14, the rest of the warrior sonnets are interspersed throughout the first half of the sequence. These images of the lady massacring enemies with her eyes and trampling on the neck of the lover are so extreme that they led J. W. Lever to posit “an attempted blending of two collections of sonnets, differing in subject-matter, characterization, and general conception.” This hypothesis led him to excise eighteen sonnets from the sequence.67 Later critics have responded to Lever’s discomfort with the war poems in two ways: by arguing that the war between the lover and his “stubborne damzell” has a touch of playfulness and humor that Lever overlooked, or by maintaining that each “individual sonnet . . . represents not the completeness of vision of Spenser the author, but the emotional state of the lover at one stage of his development” (SP, 29.1).68

While both of these responses illuminate the tone and dramatic method of the sequence, they do not account for Spenser’s singular preoccupation with the war trope. In the continental and English sequences that preceded and inspired Spenser’s Amoretti, war was just one of many conceits to depict the trials of courtship and unrequited love, but Spenser makes it one of the governing tropes of his sequence. Though Spenser had long made connections between love and warfare, in Amoretti the idea that lovers view each other as combatants becomes fundamental to his account of courtship and marriage. I would argue that Spenser returns to the image of the battlefield so frequently in his sonnet sequence in order to underscore the idea that even the most fundamental unit of society, the “naturalest and first coniunction of two,” does not spring up spontaneously.69 Rather, the lady and the lover approach each other with all the wariness of inveterate enemies, unwilling to expose themselves to the “dead doing might” of the other (SP, 1.2). In depicting the natural relations between human beings as dominated by distance and fear, Spenser draws on two sixteenth-century discourses that emphasized the natural unruliness and estrangement of human beings: Reformation theology and poetic theory. Both of these discourses underscore the need for external intervention—whether of divine grace or of human artifice—by depicting the natural state of individuals as solitary, wild, and violent. In his sonnet sequence, Spenser fuses these two traditions together. For him, as for Sidney and Puttenham, human artifice can aid divine grace in counteracting the results of the fall by binding humanity’s lower nature.

In the second poem of the sequence, Spenser reveals that the natural alienation between individuals can be credited to two innate vices: lust and pride. By disrupting his own rhyme pattern in this sonnet and failing to “make band,” Spenser underscores the idea that these vices prevent the couple from being “fit for mate” (Arte, M3r; SP, 66.6). The sonnet is a dark parody of the opening sonnet of Astrophil and Stella, where Astrophil describes himself as “great with child to speak, and helpless in [his] throes,” until his Muse at length acts as midwife, counseling him in the final line to turn back to his inner truthfulness: “ ‘Fool,’ said my muse to me; ‘look in thy heart, and write.’ ”70 Spenser’s speaker is also great with child, but his “wombe” has been taken over by an “Unquiet thought,” which the poet “bred / Of th’inward bale of [his] love pined heart” (SP, 2.4, 1, 1–2). Since he has daily “fed” his restive progeny with “sighes and sorrowes,” it has become monstrous and “woxen” greater than his “wombe,” writhing inside of him “like to [a] vipers brood” (SP, 2.3, 3, 4, 4, 6). The lover has no choice but to command the overgrown product of his passion to “Breake forth at length out of the inner part” in hopes that it can seek some “succour” for the lover in addition to sustaining its “selfe with food” (SP, 2.5, 7, 8). Spenser’s images of self-impregnation and self-feeding hark back to his description of Error and her cannibalistic “brood” of children in book 1 of The Faerie Queene and anticipate Milton’s perverse triad of Satan, Sin, and Death (FQ, 1.1.25).71 This grotesque account of the lover’s “inner part” challenges Sidney’s sanguine call to look inward: when Spenser’s lover looks in his heart to write, he finds only poison, darkness, and confusion within (SP, 2.5).

To some extent, this description of the roiling passions within the mind simply reflects Spenser’s understanding of fallen human nature, in which the passions have usurped the seat of reason. Guyon summarizes this traditional view in book 2 of The Faerie Queene when he bewails the fact that our “mortalitie” and “feeble nature” allow “raging passion with fierce tyranny” to rob “reason of her dew regalitie” and make “it seruaunt to her basest part” (SP, 2.1.57). Yet, in addition to offering a general condemnation of human sinfulness, this sonnet specifically condemns the vices of the inward-looking Petrarchan lover who revels in his own passions.72 The lover’s narcissism and self-pity nourish these unruly passions until at length they break the boundaries of the self. By continually developing his lonely feelings, the Petrarchan speaker actually intensifies his natural alienation from the lady. His overgrown, viperous thoughts confirm the lady’s trepidations about uniting herself to him.

In the middle of the poem, Spenser reinforces the idea that the lover’s unruly desire makes him unfit to form an association with the lady by breaking his own rhyme scheme:

Unquiet thought, whom at the first I bred

Of th’inward bale of my love pined hart:

and sithens have with sighes and sorrowes fed,

till greater then my wombe thou woxen art:

Breake forth at length out of the inner part,

in which thou lurkest lyke to vipers brood:

and seeke some succour both to ease my smart

thou chance to come, fall lowly at her feet:

and with meeke humblesse and afflicted mood,

pardon for thee, and grace for me intreat.

Which if she graunt, then live and my love cherish,

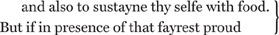

if not, die soone, and I with thee will perish. (SP, 1, bracket mine)

In the ninth line, in which the lover realizes that his unleashed thoughts may by chance stumble into the presence of the lady, the word “proud” should form a couplet with “food” that connects the central quatrains together, but the rhyme is noticeably partial.73 Since Spenser is generally precise in his rhymes, the discord violates what John Hollander calls the poet’s “metrical contract” with the reader and forcefully accentuates the disjunction between the lover’s lustful pursuit of amorous “food” and the lady’s chaste pride.74 Spenser’s couplet could be read as a juxtaposition of the base with the spiritual if we interpret the lady’s pride as a praiseworthy “scorn of base things” as the speaker does in Sonnet 5 (SP, 5.6).

But the lady’s pride is not unambiguously lofty and spiritual in Spenser’s sequence.75 The poet reveals over the course of the sequence that the lady’s “self-pleasing pride,” like the lover’s unquiet thoughts, may spring from inordinate self-love and willfulness (SP, 5.14). He charges that her pride is a sign of undue confidence in her “weake flesh” and unsociable scorn for “others ayde” (SP, 58.1, 2). Indeed, with her pride and resistance to losing her freedom, Spenser’s lady often seems to represent the “folly” that the Elizabethan “Homilie of the state of Matrimonie” depicts as one of the most deep-seated and universal obstacles to marriage: the “desire to rule, to thynke hyghly by our selfe, so that none thinketh it meete to geue place to another”; this “wicked vice of stubborne wyll and selfe loue,” according to the homily, “is more meete to breake and to disseuer the loue of hart, then to preserue concorde.”76 Thus, two perverse wills clash in Spenser’s couplet—the lover’s erotic will and the lady’s “stubborne will” (SP, 38.8). The poet’s failure to form an aural connection between the will that desires “food” and the “proud” will causes the sonnet to fall apart in the middle, breaking into an octet on the lover’s unquiet thought and a sestet on its imagined meeting with the lady (SP, 2.8, 9). Although the speaker concludes with a tentative hope that the lady will “pardon” his wild thoughts and “cherish” his love, Spenser suggests that reconciliation between the lover’s looseness and the lady’s hardness cannot occur until both of their recalcitrant wills have been reformed (SP, 2.12, 13).

ENTERTAINING TERMS: CONTRACTUAL LOGIC IN AMORETTI

After establishing in the opening poems of the sequence that the lovers begin in a state of war with one another, Spenser recounts the speaker’s attempts to find an artful remedy for this natural standoff. The speaker proposes that the lovers resolve their conflict by entering into a limited, contractual bond in which both lovers give up a small portion of their pride and self-love in order to form an association. The language of covenant runs through the sequence, but one of the most loaded scenes of negotiation comes in Sonnet 12, when the speaker reveals his desire “to make a truce and termes to entertaine” with the warrior lady (SP, 12.2). In the sixteenth century, the word “terms” in all its senses was still closely connected to the Latin terminus (boundary, limit, or end); thus, to establish the “terms” of a contract meant to delineate the limiting conditions.77 In choosing this word, Spenser suggests that the “league twixt” the lovers requires them to give up only a limited portion of their liberty and personal sovereignty in exchange for security, peace, and fellowship (SP, 65.10). This limited covenant should be agreeable to both the lover and the lady since both sedulously guard their personal freedom throughout the courtship. The speaker notes in Sonnet 65 that the lady fears to “loose [her] liberty,” and he reveals a similar defensiveness about his own sovereignty in the aphoristic couplet that concludes Sonnet 37: “Fondnesse it were for any being free, / to covet fetters, though they golden bee” (SP, 65.2, 37.13–14). If they can come to “terms,” both parties will be able to retain most of the liberty they cherish.

The idea of a limited, consensual contract runs through the sequence and plays an important part in the culminating sonnets that surround the Easter sonnet to the Lord of Lyfe. In Sonnet 65, for example, the speaker calms his lady’s fears about leaving the single state to enter into fellowship by describing wedlock as a “league” that “loyal love hath bound” and that is built on the foundation of “simple truth and mutuall good will” (SP, 65.10, 10, 11). Playing on the etymological connection between the word league and the Latin ligare, to bind, Spenser presents an account of association that is remarkably similar to Hooker’s idea that political and religious institutions are formed when individuals “consent to some certain bond of association.”78 Though they restrict freedom and constrain viperous thoughts, the “bands, the which true love doth tye,” seem to be “Sweet” because they are consonant with the natural inclinations of the lovers and freely chosen (SP, 65.5). As Spenser puts it in the betrothal sonnet, the lady is “with her owne goodwill . . . fyrmely tyde” (SP, 67.12). The ambiguous syntax of this culminating line of the sequence increases the sense that the lady consents to her bonds, for the phrase could mean either that the lady is firmly tied while giving her consent or, even more forcefully, that her “goodwill” is the very instrument or cord with which she is tied.79

This idea that freely chosen restriction can be satisfying as well as salutary plays an important role in Spenser’s account of his turn to the sonnet itself. In the eightieth sonnet of the sequence, in which Spenser excuses himself for leaving The Faerie Queene “halfe fordonne,” he compares the sonnet and its domestic subject to a “prison” to which a “steed” retires after long “toyle” in order to “rest” and become “refreshed” (SP, 80.3, 6, 5, 5, 3, 5). Although in the first two quatrains Spenser presents the love sonnet as a temporary escape from the more strenuous endeavors of epic, in the third quatrain he elevates his prison:

Till then give leave to me in pleasant mew,

to sport my muse and sing my loves sweet praise:

the contemplation of whose heavenly hew,

my spirit to an higher pitch will rayse. (SP, 80.9–12)

Though in the first half of the sonnet the poet compares himself to a steed, in using the word “mew” in the ninth line he introduces a new animal metaphor. “Mew” could be used to refer to a cage or prison in general, but it was most frequently applied to the cages where hawks were kept while molting. Hence, “in mew” came to be used metaphorically for something in the process of transformation.80 In combination with the Neoplatonic language of contemplation and spiritual transcendence in the subsequent lines, the “pleasant mew” suggests that limitation does not simply allow for temporary relaxation, but actually transforms and exalts the poet.81 By restricting himself to the confines of the entertangled sonnet, Spenser provides a model of the freely chosen bands he recommends to the lady and suggests that a “mew” may actually be more “pleasant” and uplifting than boundless freedom.

This vision of marriage and poetry as restrictions to which we freely bind ourselves seems to place Spenser in the vanguard of romantic and prosodic thinking. Indeed, readers and critics of Amoretti have long celebrated Spenser’s progressive understanding of marriage as a consensual and mutual contract between two equal parties who both have the power to set the terms of the contract. William Johnson even goes so far as to laud the poet as a “daring proponent of mutuality.”82 Although Spenser’s earlier poetry certainly contributes to his reputation as the poet of married love, it is in Amoretti and Epithalamion that he presents his most idyllic vision of the woman’s role in assenting to the contract. Unlike Amoret, the lady of the sonnets is not led away weeping “tender teares” and begging her lover to restore her “wished freedom” (FQ, 4.10.57). As Ilona Bell has argued, the powerful lady of the sonnets “seems less like a conventional sonnet lady than like Elizabeth I, declaring her right to remain single unless or until she finds a suitor who not only arouses her desire but who also acknowledges her liberty.”83 In the betrothal sonnet, Spenser seems to allow the lady to maintain her sovereignty even as she binds herself: because she has been tied with her own goodwill, she remains free.

Although the interpretations of Spenser’s sonnet sequence offered by Bell and others highlight Spenser’s surprisingly forward-looking understanding of marriage and gender relations, the idea that the lovers remain free when they choose the bands of matrimony does not capture all the nuances of Spenser’s prosodic and social theories. Indeed, this interpretation requires considerable hermeneutic ingenuity to explain away the images of bands and cages that pervade even the postbetrothal portions of the sequence.84 Critics have attempted to account for these images by describing them as relapses on the speaker’s part, as signs that he does not quite comprehend the blissful notion of “mutuall good will” (SP, 65.11).85 In order to do justice to the sequence, however, we should attempt to overcome—or embrace—our discomfort with these recurrent images of captivity, which occur even at the most idyllic moments of the sequence, and consider how they might contribute to Spenser’s distinctive theory of matrimony and social combination. In presenting captivity as an essential component of human fellowship, Spenser moves beyond the contractual logic of Hooker and presents a much more surprising and original account of association as voluntary self-yielding and mutual captivity.

THE BIRD IN A CAGE: CAPTIVITY AND THE BANDS OF MATRIMONY

Always a dedicated and alert reader of Spenser, John Keats can aid us in understanding Spenser’s embrace of restriction.86 In a letter to George and Georgiana Keats dated May 3, 1819, Keats records that he has been “endeavouring to discover a better sonnet stanza than we have,” noting that he objects to the “pouncing rhymes” of the Italian sonnet and finds the “couplet at the end” of the English sonnet “has seldom a pleasing effect.” Thus, he invents his own sonnet form with an interwoven rhyme scheme that would have warmed the cockles of Puttenham’s heart (ABCABDCABCDEDE). In the sonnet itself, he explains his preference for this intricately entertangled pattern, explaining that “If by dull rhymes our english must be chaind,” poets should at least strive to “find out . . . / Sandals more interwoven & complete / To fit the naked foot of Poesy.” He aligns himself with Spenser, Harvey, and Puttenham in the lines that follow by suggesting that the artificiality of this stanza is precisely what makes it fitting—the complex pattern indicates that every word and sound has been weighed “By ear industrious & attention meet.” Thus, in a paradox worthy of Petrarch, Keats suggests that a sonnet stanza actually seems to become more natural as it becomes more elaborate and artificial: only interwoven stanzas “fit” Poesy’s foot. Keats does not offer a way out of the necessity of captivity—he seems to admit that English must in fact be chained by dull rhymes—but he does indicate in the final lines that, because of their artfulness, interwoven chains are less onerous to the muse than other kinds of fetters: “So if we may not let the Muse be free, / She will be bound with Garlands of her own.”87

The concluding image of the Muse restrained by her own garlands recalls Spenser’s lady tied with her own goodwill and prompts an interpretation of that betrothal scene and of Spenserian wedlock that better accounts for the persistence of images of captivity in the most blissful moments of Spenser’s sequence. Spenser maintains that his lovers, like Keats’s muse, must be bound by artificial bands, so their best hope is to be bound by garlands of their own. The speaker’s confidence at the outset of the sequence that they can simply entertain terms, making limited sacrifices in order to form an association, proves misguided or, at least, incomplete. Instead, Spenser maintains that the lovers can bind the eternal band of matrimony only by sacrificing both life and liberty and yielding the self into the power of the other.

Indeed, if we return to Sonnet 12, the sonnet that begins with the speaker’s proposal that the pair make a truce and entertain terms, we can see that the contract negotiations immediately fall apart as the lover becomes captive to the lady in the second half of the sonnet. As the “disarmed” speaker approaches the lady to begin negotiations, he suddenly falls prey to a “wicked ambush” that breaks forth from her eye (SP, 12.5, 6). Being “Too feeble . . . t’abide the brunt so strong,” he is “forst to yield [his] selfe” into the hands of his fierce enemies who, after “captiving [him] streight with rigorous wrong,” go on to hold him in “cruell bands” (SP, 12.9, 10, 11, 12). At this early stage in the courtship, the speaker is by no means reconciled to his bands and vociferously protests against his captivity as an injustice. But, in taking him captive, the lady may actually be teaching him a lesson in association. Only by yielding his whole “selfe” and submitting his unruly thoughts to the restrictive “bands” of the lady will he at length be able to form a bond with her (SP, 10, 12). In order to seal the bond of association, both lovers must eventually yield, but someone must be the first to throw down arms and risk death for the sake of fellowship. In Spenser’s sequence, the male speaker must begin because he is both more powerful and more unruly: his “Unquiet thoughts” make him a threat to the lady’s chastity as well as her sovereignty (SP, 2.1). Once he has yielded himself into her power, the lady can “frame [his] thoughts and fashion [him] within,” making him a fit mate by reining in his “base affections” (SP, 8.9, 6). Thus, the sonnet sequence and the courtship it represents have the same goal as The Faerie Queene—“to fashion a gentleman or noble person in vertuous and gentle discipline”—but in Amoretti fashioning and discipline derive from a beloved human source.88 The lover can become worthy of the lady only if he gives himself over to her to be reframed and refashioned in a more virtuous and gentle mold.

Although the speaker accidentally succumbs to captivity in the twelfth sonnet when he is surprised and “forst” into bands by the lady’s dangerous eyes, as the sequence progresses he gradually and fitfully begins to embrace captivity as a means to unity with the lady (SP, 12.10). As early as Sonnet 29 he asks the lady to “accept [him] as her faithfull thrall” (SP, 29.10), but it is not until Sonnet 42 that he definitively welcomes thralldom and outlines the benefits of the lady’s restraint:

The loue which me so cruelly tormenteth,

So pleasing is in my extreamest paine:

that all the more my sorrow it augmenteth,

the more I love and doe embrace my bane.

Ne doe I wish (for wishing were but vaine)

to be acquit from my continuall smart:

but joy her thrall for ever to remayne,

and yield for pledge my poore captyued hart;

The which that it from her may never start,

let her, yf please her, bynd with adamant chayne:

and from all wandring loues which mote pervart,

his safe assurance strongly it restrayne.

Onely let her abstaine from cruelty,

and doe me not before my time to dy.89

The sonnet opens with a quatrain that plays with Petrarchan contraries, relating that the “loue which . . . so cruelly tormenteth” the lover actually is “pleasing” even when the lover is in “extreamest paine” (SP, 42.1, 2, 2). This leads him to cultivate this painful love and “embrace” his “bane” (SP, 42.4). In the second quatrain, he focuses in particular on the pleasure of his captivity, revealing that he “joy[s] her thrall for ever to remayne, / and yield[s] for pledge [his] poore captyved hart” (SP, 42.7–8). The speaker’s captivity is both voluntary and involuntary—his heart has already been “captyved” by the lady’s ambushing eye-beams, but now he joyfully “yields” it himself as a pledge of his complete dedication to the lady.90 The rhyme between “paine,” “bane,” “vaine,” and “remayne” binds the first and second quatrains together and underscores the idea that pain and permanence are inextricably linked with one another. In fact, “paine” is one of Spenser’s preferred rhyme words in the sequence, and the word is paired with “remayne” three of the seven times it occurs in Amoretti. The pair is consistently used to demonstrate that love that is “the harder wonne, the firmer will abide” (SP, 6.4).91

Here, Spenser takes the paine/remayne rhyme one step further, altering his usual rhyme scheme by continuing the B rhyme into the third quatrain. Spenser therefore interweaves this sonnet more tightly than his other sonnets in the sequence, making band between lines as far apart as the second and twelfth lines. This heightened use of rhyme’s binding power is no coincidence since the subject of the final quatrain is the benefits of allowing the lady to “bynd” him with “adamant chayne” (SP, 42.10). Only by submitting to these chains can the lover finally be rescued from the internal turmoil that plagued him in the second sonnet, for the lady will restrain him “from all wandring loues which mote pervart” (SP, 42.11). Spenser leaves the object of “pervart” ambiguous—wandering loves would pervert the lover himself, but they would also pervert the love between the couple. By restraining the viperous thoughts and wandering passions within the lover, the lady both improves his moral state and lays the groundwork for a healthy union. As in Spenser’s youthful theory of English prosody, in his mature theory of marriage coercion and restraint are essential to counteracting the shortcomings of nature—human beings cannot simply pursue their wild, natural inclinations but need the aid of an artificial bond.

Although the speaker yields his heart to the lady in Sonnet 42, she does not immediately respond in kind. She continues to guard her sovereignty for twenty-five sonnets. The enthralled speaker attempts to convince the lady to yield herself throughout this portion of the sequence, but his most powerful argument, and, I think, the one that ultimately convinces the lady, comes in Sonnet 65, two sonnets prior to the betrothal. As Kenneth Larsen points out in his notes, this sonnet corresponds with Maundy Thursday, the day on which churchgoers commemorated the Last Supper and the new covenant laid down in John 15:12: “This is my commaundement, that ye loue together as I haue loued you.”92 The traditional rite of foot washing performed during the Maundy Thursday service reinforced the idea of a covenant of mutual service. In his sonnet, Spenser draws on the themes of mutual covenanting by imagining a “league” of “mutuall good will” between the lovers in which, instead of washing each other’s feet, they “salve each others wound” (SP, 65.10, 11, 12). Yet, even though the third quatrain of this sonnet presents a vision of a consensual covenant, the poem begins with a concession that the lovers must sacrifice their liberty in order to obtain this league.

As the poem opens, the speaker is chiding his “fayre love” for a “vaine” “doubt” that has hindered the progress of the courtship (SP, 65.1). But when the lover reveals the nature of the lady’s doubt in the second line, it seems perfectly understandable: she fears to “loose [her] liberty” (SP, 65.2). In fact, Bishop John Jewel, in his homily on matrimony, acknowledges the reasonableness of female trepidations about marriage, noting that “they must specially feele the greefe and paynes of their matrimonie, in that they relinquish the libertie of their owne rule, in the payne of their traueling, in the bryngyng vp of their chyldren.”93 The speaker, moreover, has spent a large portion of the sonnet sequence regaling us with his own fears about captivity and maintaining that it would be “Fondnesse” for “any being free, / to covet fetters, though they golden bee” (SP, 37.13–14). Since he submitted himself to the lady’s adamantine chain in Sonnet 42, he now reverses his position, insisting instead that it is the fear of lost liberty that is “vaine” and “fond” (SP, 65.1, 2).