THERE ARE SEVERAL WAYS TO obtain a freshwater source for your irrigation needs. The simplest source is a municipal water supply, if it is available. Additional sources of freshwater include drilled wells, dug wells, and driven wells. If you have modern plumbing, you have a source of freshwater right under your roof.

Chapter 2 gave you a brief introduction to various water sources and irrigation methods. This chapter provides technical information needed to make a wise irrigation decision. Since irrigation requires a water source, there is no better place to start than with the options for water.

Water used for drinking, cooking, and bathing is potable water. Water used for irrigation purposes isn’t necessarily potable, but it can be, especially if you have an abundant supply of potable water. In Chapter 4, we’ll look at nonpotable sources suitable for irrigation.

Normally potable water is derived from municipal or private well systems. Sometimes it is taken from springs in the ground.

Municipal water systems offer advantages for watering. The two most obvious are the ready access to an abundant water supply and the fact that tapping into the water source from within your home doesn’t incur much additional cost. I can think of only two disadvantages associated with using city water for irrigation. One is that you may be limited in regards to when and how often you can use a public water source for irrigation. The other is the cost you may be charged for metered water.

Assuming that your home is connected to a public water service and that you are willing to pay so much per gallon for its use in irrigation, you are pretty well set. All you have to do is cut a tee fitting into the main water supply within your home, and you’re in business. (See Chapter 9 for instructions.)

Plumbers often refer to driven wells as points. They talk about driving a point, which means creating a well. We know that point wells are inexpensive, but there is more to consider before running out and buying equipment to sink your own well.

Finding water to drive your point can be the most difficult challenge in creating a driven well. If the water table in your area is low, a driven well may not be practical. Call your local county Cooperative Extension Service office, or some similar agency, to request information on water levels in your area.

There is no rule of thumb for determining when a water table is too deep for a driven point since other factors affect its feasibility. For example, if your soil is loose and sandy, you can drive a point to great depths. A rocky ledge, however, will prevent any reasonable possibility for using a driven point.

You can get some idea of soil conditions by digging a hole with a shovel or by driving a steel rod into the ground. Before doing either, make sure there are no underground utilities. Surface water running near the top of the earth is one indicator of a good drive point. Once you’ve determined that your soil allows the use of a driven point, you can begin to install the well, for which you will need some specific equipment and materials.

The well point and accessories are available at some, but not all, plumbing suppliers, so call to make sure the items you need are in stock before going to pick them up.

The tools needed for this job include: a sledgehammer, a stepladder, and a pipe wrench or large pliers. You will also need a drive tip to attach to the first section of the point shaft that will be driven into the ground. Depending on the expected depth of your well, you also will need several sections of point shafts — tubes with fine slits cut into them. Once the point shaft is below the water table, water runs into the slits and fills the shaft. The shaft retains water for pumping as long as the slits remain below the water table.

Shaft sections for well points are normally sold in 5- and 10-foot sections. The shorter sections are easier to manipulate. It is also possible to buy the shafts made from either steel or Schedule-40 plastic. Both will work in soft ground, but metal shafts tend to do better in rocky spots.

To join the shaft sections together, you will need drive couplings, which provide a surface to hammer the point as it is driven so as not to damage the threaded ends of the shaft. As each section is driven into the ground, a new section can be added by threading it into a coupling.

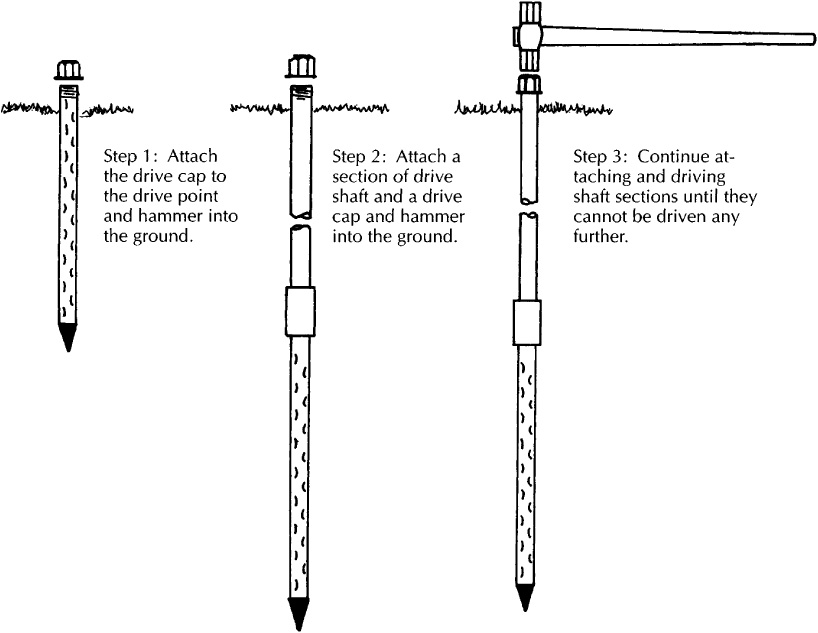

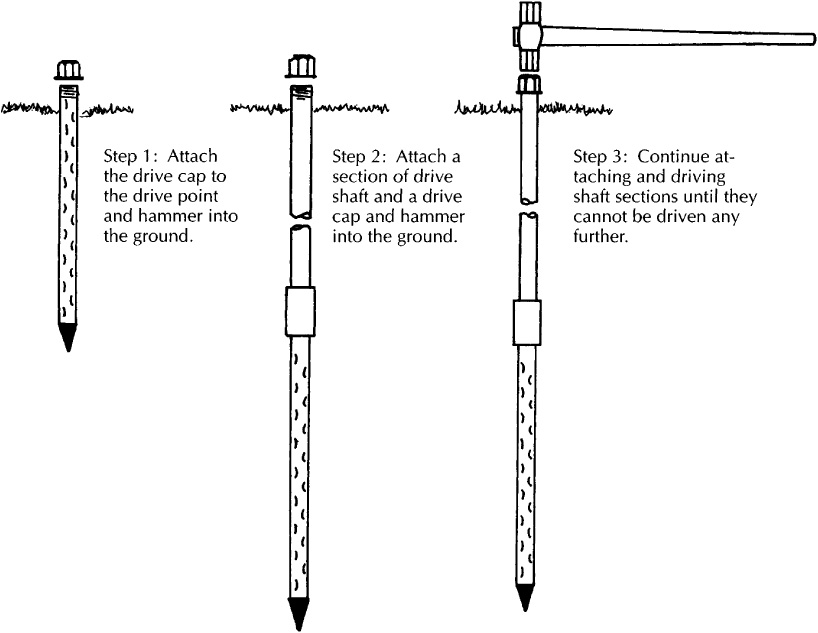

Once you have all your gear, you’re ready to drive your point. Attach the drive cap to the drive point. Some sections of drive points come with the first shaft section. Pick your place on the ground and place the drive point on it. If you’re tall and your ground is soft, you may not need a ladder when working with 5-foot drive sections, but it may be easier to work from a stepladder.

With the drive point in place, use a heavy hammer (at least six pounds) to drive the point into the earth. When the drive cap gets close to the ground, install a second section of drive shaft. Also install a drive cap on the remaining threads of the new shaft. Continue this process until the shaft cannot be driven any further. The deeper the shaft is driven, the more likely you are to hit a vein of water that will produce during dry spells.

When you have driven your last section of point, you are ready to install the piping for your pump. You will want to check to make sure you have hit water before hooking up a pump. To do this, drop a line with something on the end of it (like a weighted cotton ball or the nut from a bolt) down the point to test for water in the shaft. After it hits bottom, pull the string up and see if it is wet. You can also determine how high your water column is from the length of wetness on the string.

A driven well is created by driving a point into soil where you’ve determined water is likely to be found. You can drive it yourself with a sledgehammer and some muscle strength.

The drawbacks of driven wells may be great enough to make you turn your attention to some other type of well or water source. First of all, you may drive several points without finding water, and if you do locate water, there is no guarantee how much volume you will be able to pump without depleting the supply. When your irrigation plans call for a substantial amount of water, this can be a very real problem.

Due to the nature of a driven well, you cannot expect too much water production. The well shaft is very small, and the point is not likely to hit a major vein of water with a high gpm rating. Also, there is not enough volume of water maintained in the point shaft to keep up with heavy usage from irrigation equipment. If you want to water a small garden once a day, a driven well will probably work fine, but don’t expect to water a large lawn repetitively without problems.

On the other hand, I know of several homes in Maine where a driven point is the only source of water. Most of the locations have sandy soil, so the points were easy to drive into decent water levels. The owners of these homes use water from their points all year and don’t experience problems with water quantity. While driven points cannot be relied on to provide adequate water for large residential irrigation projects, there are many times when a point can serve your needs.

Another common problem with a driven well is the slits in the point shafts becoming blocked with debris and sediment, preventing water from entering the shaft. Ultimately, this results in a lack of water and a need to drive a new point. Aside from these potential drawbacks, driven wells can give good service.

There is no comparison between a driven well and a dug or drilled well. The advantages of the first far exceed those of the others: Driven points are small, easy to install, and inexpensive. These facts make a driven well worth considering.

Given the low cost of installing a driven well, it is easy to justify the cost of several driven wells in different locations. You might have one for your garden and another for watering your lawn. It is also possible to drive multiple points in various locations to hedge against running out of water. If you have a driven well that doesn’t produce a heavy volume of water at one time, but replenishes itself well, you can pump into a storage tank, which will give you plenty of volume when you need it, without putting a strain on your well.

Dug wells are very common in southern states, but not in the Northeast. I’ve owned three homes served by dug wells. Only one of the wells didn’t keep up with my needs for water, due, in part, to a large, whirlpool tub that consumed hundreds of gallons of water each week. The well did fine most of the time, but there were occasions when it ran empty. The bad times were always in the heat of a Virginia summer, obviously, and this is when irrigation water is needed most.

If your home is served by a dug well, you can use the water for your house and your irrigation needs, although you may find that it cannot handle the demands you are putting on it. On the other hand, I have seen shallow (dug) wells that were impossible to run dry.

As a home builder and plumber, I have had a wealth of experience with wells. In the early days, I climbed inside old, hand-dug wells lined with rock, which was not one of the more glamorous sides of plumbing. I never knew what kind of creepy crawlers might be laying on the next rock as I descended into the dark depths. Modern dug wells are lined with round concrete sleeves instead of rocks. Also, it is no longer necessary to climb into wells to work on pumps and related equipment, fortunately.

When a house is built and a well is used for water, the well must be disinfected and tested for bacteria. This is usually done by pouring chlorine bleach into the drinking water and letting it set for a while. Next, the water is drained out of the well, and the reserve chamber is allowed to refill with fresh water. I’ve built houses where we could never get the shallow wells to run dry. In some cases, we ran as many faucets as we could for over 12 hours without eliminating the supply of water in the well. So, there is really no way to know if a dug well will have trouble producing a high volume of water or not. You have to base your decision on averages, and, on average, a shallow well is likely to have problems maintaining a large demand for water during hot, dry summer months.

I won’t advise you not to install your own dug well, but I won’t recommend it. In my opinion, all well drilling and digging operations should be left to professionals, with the exception of driven wells. You can install your own pump and piping, but leave the earth work to the pros.

Dug wells offer several advantages over drilled wells. First, they are considerably less expensive to create. If you hit a good vein of water, a dug well can produce a high quantity of water on demand. The cost of installing a pump and piping is less for a dug well than for a drilled well. Installing a pump in a dug well also is easier than installing a submersible pump in a drilled well.

Now for the disadvantages. Dug wells sometimes run out of water. You can never be guaranteed of hitting water when creating a well, but the odds of striking a usable quantity of water are better when the well is drilled, rather than dug. Dug wells have much larger diameters than drilled wells, which means they take up more space. An average dug well will have a diameter of about 3 feet; a drilled well will not be more than 6 inches in diameter. If, for any reason, the top is left off a dug well, you have created an instant death trap. Dug wells are large enough to swallow an adult, child, or pet. Sediment also can be cause for concern in a dug well. As time passes, sediment can invade the well and make it shallower. In extreme cases, this can render the well useless.

All in all, dug wells are a pretty good source of irrigation water, the caveat being water quantity. If you will need extensive amounts of water for prolonged periods of time, however, a dug well is not a wise idea. Under such conditions, a drilled well is the way to go.

Installing a drilled well is definitely beyond the capability of most homeowners. These wells usually are drilled with rigs costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, and you can’t just run down to the rental store and get one for the weekend.

Drilled wells require very little space on the surface of the earth. Their small-diameter pipe is unobtrusive and generally presents little risk to people. The depth of a drilled well can vary a great deal. A well drilled on one side of your property may go down 150 feet to hit an aquifer capable of yielding a flow rate of 5 gpm, while a second well at another location on the same property may result in a depth of 300 feet or more.

Drilled wells are expensive but almost never run dry, and the chances of hitting a satisfactory water vein are extremely good, due to the depth possibility of the well. While the cost of a drilled well is probably twice that of a dug well, there are some assurances when drilling.

There are two approaches to hiring a well driller. You can pay the driller on a per-foot basis or on a flat-rate basis. The per-foot basis is more risky, because you have no way of knowing the depth of the well. However, I’ve taken this gamble on many occasions and always won, so far. That’s not to say, though, that agreeing to a per-foot deal is the best method.

When you contract a well driller on a flat-rate basis, you are guaranteed water at a minimum flow rate, usually 3 gpm. Even if the driller hits a dry hole and has to start over, you’re only paying the contracted amount. By hiring the work in this manner, you can budget and control the cost of your well. Taking the gamble on a per-foot basis could result in a well that costs much more than you or the driller anticipated. Even though I have gambled, I would recommend that you settle on a firm contract price and reduce your risk.

Apart from the costs of a drilled well and a submersible pump system, it is hard to find any disadvantages to this method.