THE RIGHT PIPING CONNECTIONS are an absolute necessity when installing an irrigation system. Even if code requirements in your area are lax on issues such as backflow protection, you cannot afford to cut corners when it may endanger your health. While you may not see any danger in connecting an irrigation system to your home’s water supply, there is potential for disaster.

Aside from health issues, you must know how to install valves and fittings to get your irrigation piping connected to its water source. Do you know how to solder copper pipes and fittings? Would you know where to begin in making a connection between copper water pipes and polybutylene irrigation pipes?

If your system requires a pressure-reducing valve, will you know what type to buy and how to install it? There are many questions that can arise when you get to the stage of making final connections with your irrigation piping.

Since there are many irrigation systems available, there are a multitude of ways to connect them to a water supply. The methods used with a cistern are likely to be different from those employed with a municipal water supply. Tying into a pressure tank with a pump system is yet another possibility. All of these jobs can involve different types of pipe and different connection methods. This chapter offers an overview of common types of connections.

Backflow protection has gained importance over the past several years. When I entered the plumbing trade, backflow preventers were never used in residential plumbing. As people have become more educated in health risks, the requirements for backflow prevention have grown. Today, nearly every house plumbed to code has some type of backflow prevention.

What is backflow prevention? It is just as its name implies, a form of protection that prevents water from flowing backwards in a potable water system. It’s important because it prohibits potable water pipes from becoming contaminated with chemicals or other materials which could be detrimental to human health.

Is backflow prevention really needed? Yes. While the need for such protection is rarely seen, the protection is priceless when it is called upon to do its job. Let me give you a couple of examples of how you can suffer from not installing backflow preventers on your piping.

Consider the example of a simple garden hose you have connected to the outside faucet of your home. The hose bibb (faucet) is not equipped with a backflow preventer. After watering your garden plants, you decide to spray your potato plants to rid them of beetles. To do this, you install a pesticide bottle/sprayer on the end of your water hose. Just as you begin spraying the poison, you are called into the house because the water heater is leaking onto the basement floor. You set the sprayer down on the ground and rush into the house.

In the basement, you find a large puddle of water forming on the floor. You immediately go to the main water cut-off for your home and close the valve. Upon further inspection, you find that the water heater is beyond repair and must be replaced. Knowing what plumbers charge, you decide to save yourself a little money by draining the water heater while you are waiting for a plumber to arrive. However, as you drain the water heater, you are, unknowingly, contaminating the pipes which convey your drinking water.

Do you know what’s going on? If you guessed that the poison in the bottle that is connected to the garden hose is being sucked back into the water pipes, you’re right. When the water heater is drained, it creates suction in the potable water pipes. Since the garden hose is still connected to an open hose bibb, the contents of the hose are also drained. This creates a siphonic action pulling the pesticide into the pipes. Once the poison comes into contact with the potable water piping, the walls of the piping become contaminated. This disaster can be avoided by installing an inexpensive backflow preventer on the threads of a hose bibb.

As another example, consider the case of an extensive garden irrigation system deriving water from the house well potable water supply. The irrigation system was designed so that you could mix plant food with the irrigation water, and that is what you are doing on this fateful day.

The irrigation system is running, producing a mixture of water and plant food for your vegetables when there is a power failure and your well pump cuts off. To make matters worse, the check valve on the system sticks in the open position. As a result, all of the plant food is sucked back into the household piping. With the check valve malfunctioning, water rushes back into the well, pulling a vacuum on the piping system. This causes the plant food to be sucked into the potable water system, contaminating the pipes.

When you install an irrigation system, install backflow preventers. These devices, for the purposes we are discussing, are not very expensive, and they can be one of the best investments you will ever make. There are a number of ways that a backflow problem can be caused. I’ve given you two examples of how easily pipes could become contaminated, and there are many other ways for it to happen. The installation of check valves and backflow preventers can protect you, but they can only do it if they are installed.

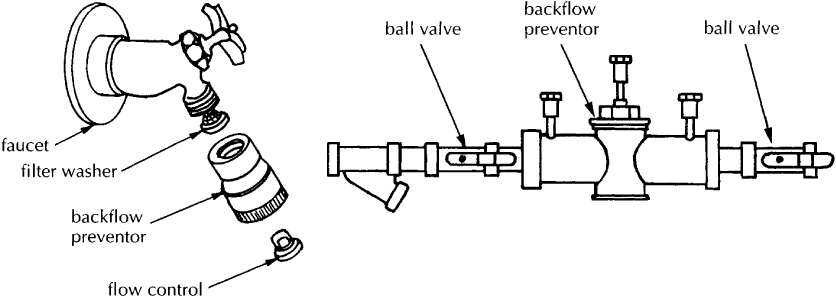

All hose bibbs should be equipped with backflow preventers. Some types of hose bibbs are manufactured with a backflow preventer built right into them, others require installing one on their threads. A typical hosebibb backflow preventer that screws onto the threads of the outside faucet costs less than $10. It has threads on the other end for connecting a garden hose. This is a very simple, inexpensive item, but it could save your life, or at least a lot of money.

In-line protection with a backflow preventer should be used on all pipes connecting your irrigation system to your potable water supply. This type of device costs less than $50, but is well worth it. An in-line backflow preventer is installed in a section of piping with the same principals used to install a coupling, union, or other fitting. If you have the skills needed to install your own piping, you have the ability to install this type of backflow preventer.

Backflow (or anti-syphon) prevention is important to have either on a hose bibb (at left) or as part of your in-line piping (at right). A backflow preventor keeps water from your irrigation system from flowing backwards into your potable water supply.

A check valve can be installed in your piping as added insurance. This is a device that allows water to run through it in only one direction. For example, water could leave your home, pass through the check valve, and feed your irrigation system, but water from the irrigation piping could not run back past the check valve. While a combination of a check valve and an in-line backflow preventer is not necessary, it is wise. The check valve should be installed first, and the backflow preventer installed next. Check valves are available in different configurations and prices, with most of them costing between $10 and $20.

When installing an in-line backflow preventer or check valve, you must look carefully on the device for the word “inlet” or an arrow. The end of the device labeled “inlet” is installed on the piping going from your house to the irrigation piping. In other words, the inlet end is installed so that it is the end receiving the first water pressure.

Check valves and backflow preventers marked with an arrow should be installed so that the arrow indicates the direction of flow. In other words, the arrow should be pointing in the direction of your irrigation piping. If you don’t observe this rule, your device will not function properly. For example, a check valve installed backwards will not allow any water to be delivered to the irrigation piping. If this happens, you have to remove the check valve and reinstall it with the arrow pointing in the right direction.

Some irrigation systems require a reduction in water pressure. I discussed the operating pressure ranges for different types of irrigation equipment in Chapter 5. Most equipment will work effectively with normal household pressure, but for some equipment you may have to lower the water pressure by installing a pressure-reducing valve.

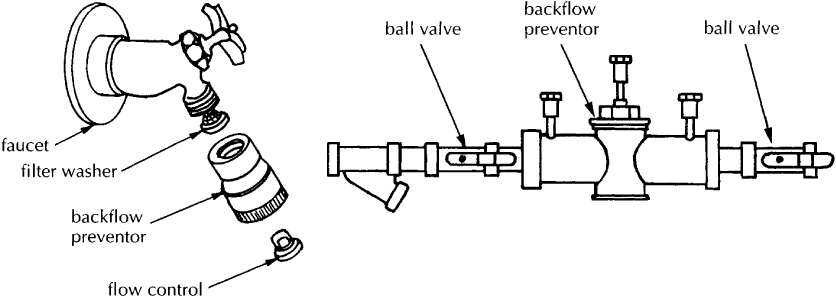

A pressure-reducing valve is installed in the pipe that supplies water to an irrigation system. Most of these valves allow a considerable range of adjustment. It is common to see the adjustment range running from 25 psi to 75 psi. If your irrigation equipment requires an operating pressure lower than your household pressure, a pressure-reducing valve is the answer.

Installing a pressure-reducing valve is no more difficult than working with any type of fitting. Some valves are provided with female threads and others are set up with connections meant to be soldered to copper tubing. If you are not working with copper piping, make sure to buy one with female threads.

A pressure-reducing valve is necessary if your irrigation equipment requires a water pressure that is lower than your household water supply pressure.

Just as check valves are normally marked with a direction arrow, so are pressure-reducing valves. It is important to install the valve with the arrow pointing in the direction of your irrigation piping. The weight of some pressure-reducing valves is enough to require more support than standard piping. When you install such a valve, make sure that its weight is supported with a hanger or some other acceptable support, so that its weight doesn’t create stress on the piping.

Water pressure regulators are also desirable with some types of irrigation equipment. These devices look similar to pressure-reducing valves, and they install in about the same way. Some have a range of adjustment equal to that of pressure-reducing valves, and others have a smaller range of adjustment. If the manufacturer of your irrigation equipment specifies a need for a regulator, follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for a pressure setting.

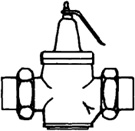

A cut-off valve should be installed where the irrigation piping meets the household piping so that the irrigation system can be shut off without affecting the water pressure in the home.

Cut-off valves should be installed at all points where irrigation piping meets household piping. These allow the water to the irrigation system to be cut off without affecting the water pressure in the home. While any type of cutoff valve will work, a gate valve or ball valve is preferable. These are full-flow valves that don’t depend on washers to ensure a positive closing action, giving you better water flow and a more dependable cut-off valve.

Cut-off valves are made with different types of connections in mind. There are valves built with sockets to accept copper tubing for soldered joints. Some valves are made with female threads on either end. If you will not be using copper tubing, the valves with threaded connection ports are the ones to buy.

Many irrigation systems are portable enough to be taken down after each growing season, eliminating a need for frost protection. Other systems, however, are complex and difficult to remove and must be protected against freezing weather.

If you are installing an underground irrigation system, you can minimize the risk of frozen pipes by burying the system below the frost line. This, coupled with the use of drain valves, normally provides adequate protection. However, there are times when it is not feasible to bury the piping at a sufficient depth to avoid freezing. This is often the case in Maine, where big rocks and bedrock are commonly encountered at shallow depths and where the frost line is about four feet deep. If you are faced with this type of a situation, you must provide connections for clearing the system of all standing water when the irrigation season is over. The same is true for overhead irrigation layouts that are too much trouble to disassemble each year.

The best way to ensure that a system is free of standing water is to blow the water out of the pipes with air pressure. This is not a complicated procedure, as long as you planned for the need in advance and installed the proper connections. What are the proper connections? Well, first of all, you need drain valves that can be opened to release water from the irrigation piping.

For an overhead system, a drain valve is easy to access. You simply install a boiler drain wherever you want to drain the system, and when that time comes, open the valve by hand. Underground systems are not so easy to deal with. When you install drain valves in an underground system, you must make provisions for accessing the valves, which is usually done with a plastic box that sits over the valve and extends to ground level. By removing the cover of the box, you have direct access to the valve. You may need a special tool to operate the valve, but the box gives you the required access.

Valve boxes are molded in a way that allows them to sit over a section of pipe. Once the box is in place, the hole around the box is filled with dirt. These boxes are available in various heights to accommodate different frost lines. If the pipe is buried at a depth beyond reach, a valve is installed that can be turned on and off with a water key.

In addition to drain valves, your system must be equipped with a connection point for an air hose. There are several ways to do this. You can rig up a hose adapter that allows you to screw the hose from an air compressor onto the threads of a boiler drain. These are the same type of threads found on outside faucets. If you prefer to use a standard air chuck, you will have to create a connection that will accept an air valve. This is not a big job.

Let’s assume that your irrigation piping has a ¾-inch diameter. You need to work your way to a point where an air valve with ¼-threads can be screwed into the system. To do this, you will use a series of reducing fittings. Your first reduction might go from a ¾-inch fitting to a ½-inch fitting. From there you could go down to a ¼-inch fitting. This will give you female threads of a size that will allow the installation of an air valve.

Air valves should be installed at the furthest point of the irrigation system. It is a good idea to install more than one. Another wise move is to install a standard cut-off valve between the irrigation piping and the air valve. This cut-off valve can remain in a closed position until you are ready to evacuate the system. Without such a valve, it is possible that water will leak past the air valve. For a few extra dollars you can have a solid valve that will not allow this to happen.

I have described how to install various types of pipes in Chapters 5 and 6, but I haven’t addressed working with copper pipe. While it is unlikely that you will use copper in making your irrigation system, it is very likely that your irrigation piping will tie into copper pipe for the water source, especially if that source comes from household pipes.

Some houses are plumbed with CPVC water pipes, and many newer homes have polybutylene pipe, but a majority of houses have copper water pipes. In connecting non-copper irrigation piping to copper water pipes you must have the proper adaptations for a connection and learn to solder or use compression fittings for making the actual connection.

Assume that you have used polybutylene piping for your irrigation system and you are ready to connect the PB pipe to the copper pipe. To do this, you will need to cut out a section of the irrigation pipe to install a tee fitting. Shut off the water to the main water pipe before cutting. Once you have the main water supply shut off, open the faucets in your sinks, lavatories, and bathing units. If you have a valve in a position lower than where you will be making the cut, open that too, so that you drain as much water from the system as possible before cutting into the main water pipe.

There are two types of tee fittings: a standard copper tee, which works best, or a compression tee, if you can find one large enough to fit over the pipe you are using. If you are connecting to ½-inch (inside diameter) copper, a compression tee shouldn’t be hard to find. Anything larger could prove troublesome to locate.

There is a difference in measuring systems that may be confusing if you’re not aware of it. Soldered fittings and plumbing pipe are sized by the inside diameters, while compression fittings are sized by the outside diameter. For example, a pipe that uses ½-inch solder-type fittings will use ⅝-inch compression fittings; pipe that uses ¾-inch solder-type fittings will require ⅞-inch compression fittings. Just remember, compression fittings are sized for outside diameters and solder fittings are sized for inside dimensions.

Compression fittings connect to existing copper water pipes without soldering the joints, but they are more prone to leakage than are soldered joints. For this reason, I prefer soldered joints. If you are using a compression fitting with PB pipe, you shouldn’t use a brass compression ferrule, because, when the compression nut is tightened too much, the sharp edges of a metal ferrule can cut into the walls of PB pipe. Use a nylon ferrule if you mate PB pipe to a compression fitting.

With a compression tee no other adapter is needed. With a standard solder-type fitting, you will need a conversion adapter. If barbed fittings and crimp rings are used to install PB pipe, the adapter used will be soldered into the tee outlet. The other end of the fitting will be a barbed insert. Once all soldering is done and the pipe and fittings have cooled, the PB pipe can be connected to the barbed adapter.

Compression fittings should not be used with PE pipe. The proper adaptation requires a standard tee fitting to be installed in the copper water main. A short piece of copper is placed in the tee outlet and a male or female adapter is soldered onto the end of this pipe. The result is a threaded connection point where an insert fitting can be attached. The insert fitting will screw into, or onto, the threaded fitting, allowing the PE pipe to be connected to the insert end of the fitting. This same approach can be used when connecting CPVC pipe to copper.

Installing a standard solder-type tee is not a big job, but it can be frustrating, even for professional plumbers. If the pipe being connected is not empty of all water, soldering joints that won’t leak is difficult. There are ways, however, to work around water and the steam created from it. To expand on this, let’s go through the methods used to install a tee fitting, step by step.

Connecting irrigation piping to copper household piping with the best joints available requires making watertight solder joints. Soldering joints with copper pipe and fittings is a job that most anyone can learn to do with the following instructions.

1. Cut off all water to the pipe on which you will be working, and drain all fixtures and pipes as best as you can.

2. To prepare for making cuts for the tee fitting, hold the tee fitting up against the section of pipe you will be cutting. Notice that the tee has hubs on each end that flare out to be a little larger in diameter than the tee itself. The pipe should be cut so that it will extend fully into the hubs on each end of the fitting. Mark the cut locations on the pipe with a pencil. As a rule of thumb, ½-inch fittings will fit into the fitting for ½ of an inch, and ¾-inch fittings accept a %-inch length of pipe. If you are uneasy about making a perfect cut, you can cut more pipe than you need and use a coupling with the tee to put everything back together again.

3. Cut out a section of pipe for the tee to be installed. Copper pipe can be cut with a hacksaw, but the job is easier when you have a true copper cutter. These cutters have rollers and a cutting wheel. Inexpensive versions are sold in hardware stores, and even cheap copper cutters work better than a hacksaw. Cut the pipe as marked. Don’t be surprised if a little water sprays out as you cut; this is normal. Once both cuts are made and the pipe section is removed, hold the tee in place to check for fit. If you find you removed too much, cut out another several inches of the pipe to make room for both the tee and a coupling.

In some cases, there is not enough play in a pipe for installing a fitting, such as when the pipe ends can’t be moved back and forth enough to allow the fitting to be installed and the pipe to be seated in the hubs. If this happens, buy slip couplings (couplings without stops), so they can be slid along a length of pipe indefinitely. See Step 7 for further explanation.

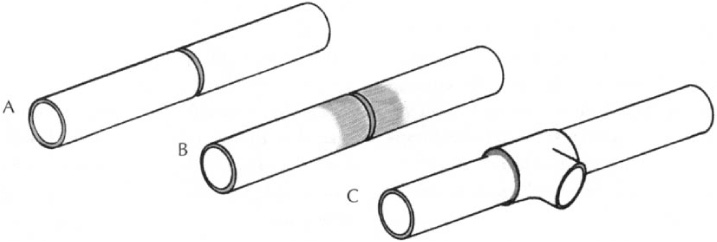

Connecting irrigation piping to copper household piping requires making a clean cut with a hacksaw (A), sanding the ends of the pipe with fine-grit sandpaper (B), and joining the pipe ends in a fitting (C).

4. Prepare your joint by sanding the ends of the pipe with a fine-grit sandpaper until the ends of the pipes are shiny from the end to a point beyond where the fitting hub will terminate. When the fitting is placed on the end of the pipe fully, there still should be some shiny pipe visible.

5. Clean the fitting with a special wire brush. If you don’t have a brush, you can roll sandpaper around a pencil. Scrub the inside of the fitting until it shines.

6. After all joint areas are clean, apply a generous coating of flux to the fitting hubs and pipe ends with a small brush. Flux helps to clean the joint area and makes solder run around the joint. There are numerous brands on the market. Don’t allow flux to get in your eyes, mouth, or cuts because it burns terribly.

With all areas coated in flux, put the pipe and fitting together. Make sure the pipe sinks all the way into the fitting hubs.

7. If you can’t get the fitting onto the pipe ends, cut out several additional inches of pipe. Shine the end and apply flux. Slide a slip coupling over the pipe and slide it back until the end of the pipe is visible. At this point you have your tee installed on one pipe end and the slip coupling placed over the other pipe end. Measure between the tee and the exposed pipe end. Cut a piece of pipe that will sit in the tee and extend to within about ½ inch of the exposed pipe end. Clean each end of the pipe and coat them with flux. Install one end in the tee. Now you have a short gap between the two remaining pipe ends. Slide the slip coupling down to bridge the gap.

8. This actual soldering of the joint is a little more difficult than the previous steps. You will need a torch and a roll of solder. The torch can be a hand-held propane type sold in hardware stores. The solder must be plumbing solder, not electronic solder, and should be lead-free.

Assuming there is no residual water in the pipe being soldered, begin by heating the tee fitting at one of its hubs. Hold the flame under the fitting at the point where the hub meets the tee. This is assuming you are soldering a horizontal pipe. If the pipe is vertical, hold the flame on either side of the fitting with the flame near where the fitting meets its hub. As you heat the fitting, you will see the flux begin to melt and the copper change color.

Assuming you are working with horizontal piping and that the flame is beneath the fitting, place the tip of the solder on the top of the tee, at the point where the pipe enters the fitting. If it doesn’t melt and runaround the fitting immediately, remove the solder. Continue heating the fitting through this entire process. After heating the fitting a little longer, touch the solder to the pipe and fitting to see if it will melt. When the temperature is right, the solder will melt and run around the fitting.

Vertical joints are no more difficult than any other type to solder. The heat and the flux will pull the solder up into the vertical hub. The key is to keep the heat near the point where the hub becomes the fitting. By doing this, the heat will pull the solder up or down, depending on which end of the fitting you are working with.

If the pipe turns black, it is too hot and will not take a good solder joint. The key to successful soldering is in the temperature and preparation work. The prep work is easy enough, but you will have to experiment a little to learn when the temperature is right. If solder doesn’t run smoothly around a fitting, dab on some more flux, around where the pipe and fitting meet. This will often solve the problem.

9. If your solder clumps and falls off the joint, or you see steam blowing out around a fitting, there is probably water in the pipe. If you have water in a pipe, you will have to take some steps to eliminate the problem. One way is to install a bleed coupling that has a vent hole in it. By removing the cap and rubber gasket from the vent hole, water and steam can escape, leaving you free to solder. If a bleed coupling isn’t available, you can use a piece of bread to solve your problem, believe it or not!

Packing the soft center of white bread (no crusts!) into a pipe with your finger can stop the flow of trickling water long enough to allow a successful solder joint. Don’t pack it too tightly, however. (As a rookie plumber, I once packed bread into a water line so tightly with a pencil that I obstructed the pipe and no water could flow into the fixture being served by the pipe!) After the joint has cooled, cut the water back on and flush the bread out of the system. Ideally, you should bleed the bread out through a tub spout or outside faucet. Water will also dissolve the bread and allow it to pass through a sink faucet, but be sure to remove the aerator so the bread won’t clog up the screen.

Pointers on Soldering

Always wear eye protection because hot solder can splash, bounce, and drip into your face.

Always wear eye protection because hot solder can splash, bounce, and drip into your face.

Keep a fire extinguisher handy, since you never know when your torch may ignite some unexpected fire. If you are soldering close to a combustible material, like wood, put aluminum foil or some metal substance between the flame and the combustible material. To be on the safe side, you can even saturate the combustible material with water before you begin to solder.

Keep a fire extinguisher handy, since you never know when your torch may ignite some unexpected fire. If you are soldering close to a combustible material, like wood, put aluminum foil or some metal substance between the flame and the combustible material. To be on the safe side, you can even saturate the combustible material with water before you begin to solder.

Don’t touch pipes, valves, and fittings that have been soldered recently since they retain the heat for several minutes and can inflict nasty burns.

Don’t touch pipes, valves, and fittings that have been soldered recently since they retain the heat for several minutes and can inflict nasty burns.

Allow a few minutes after soldering is completed before turning on the water. If you turn the water back on and discover a leak, don’t try to resolder the fitting. Cut it out and replace it.

Allow a few minutes after soldering is completed before turning on the water. If you turn the water back on and discover a leak, don’t try to resolder the fitting. Cut it out and replace it.

Screw joints are simple enough: You screw male threads into female threads. However, there are some rules to be followed. First of all, some type of thread sealant should be applied to the male threads before they are mated with female threads. A lot of plumbers prefer to use a tape sealant, which many manufacturers also recommend for their sprinkler heads and accessories. I prefer a paste-type thread sealant for most purposes, but when a manufacturer specifics tape sealant, use it.

When applying pipe sealant of any kind, only apply it to male threads, never to female threads. The way tape sealant is wrapped around threads can have a bearing on how well it works. Wrap the tape so that it becomes tighter as the joint is made. Putting the tape on backwards may cause it to come loose as the joint is made.

Screw joints should be tightened to a point where they don’t leak, obviously. If you are working with nylon or plastic threads, tightening them too much can result in a broken set of threads. Make the fittings snug, but don’t apply excessive pressure. Learning how tight is tight enough comes with experience. Use your own judgement, but be aware that one extra turn can result in a broken fitting.

Start all threaded fittings by hand and screw them in as far as you can without using a wrench to avoid crossthreading. Crossthreading can be a real problem when working with nonmetallic threads such as nylon and plastic. If the fitting is crooked when the tightening begins, the result will be ruined threads. So screw by hand as much as possible to keep the threads aligned.

If you have CPVC pipe in your house, your pipe connections will be glue joints. I discussed making glue joints earlier in reference to new installations using dry pipes. Cutting into existing CPVC pipes follows the same procedures, but you must be sure that water doesn’t mess up the joints. If water runs too soon through a recently glued pipe, the result will be globs of glue and leaks.

After cutting the pipe, give it time to drain completely. Dry it out with a rag, if possible. Wait to watch for dripping and don’t try to glue a joint until you are sure the water has drained completely. Other than that, the process will be the same as the procedures described on pages 102-105. One other word of caution: If you are installing screw fittings in CPVC, be careful not to break the pipe. I can’t stress enough how easy it is to crack, snap, and break CPVC and PVC pipe.

Getting the irrigation feed pipe into your home requires special attention. If you’re running a seasonal water line, it can enter the home aboveground. Underground piping, due to its depth, must come through a hole in the foundation of your home below ground level.

Getting through the foundation depends on the type of material you are penetrating. Cinderblock is easy to get through with a cold chisel and a hammer. A rotary hammer drill also works quickly on cinderblock and brick. If, however, you have to go through an 8-inch concrete wall, a cold chisel won’t work, and you’ll be much better off renting an electric jackhammer. These tools can be rented at most tool rental centers, run on standard household current, and are light enough to hold up against the wall without undue stress. You may, however, wish to support the jackhammer with a stepladder to take some of the pressure off your arms.

Once you have a hole in your foundation, you need to install a sleeve. This is a pipe at least twice as large as the feed pipe providing your irrigation system with water. If you are running a ¾-inch feed pipe, your sleeve should be at least a 1½-inch pipe. If you don’t sleeve your pipe, the foundation material may have a corrosive reaction on the feed pipe. It is also possible that the rough edges of a foundation will rub a hole in the feed pipe. Plumbing codes require sleeves, and they are good protection for your feed pipe.

If your irrigation feed pipe is coming into your home aboveground, you can avoid penetrating the foundation. Drill through the siding and band board of your house with a wood-cutting bit, assuming you have wood or vinyl siding. If you have aluminum siding, a metal-cutting hole saw will be needed. This will get you through the siding and to the wood, where you can switch to a wood-boring bit. A sleeve is not necessary in this type of installation.

There is an alternative to boring a hole in the side of your house for an aboveground pipe. You can run the pipe to an outside faucet and connect to its threads. Adapters can be purchased to allow your feed pipe to screw onto the threads of the hose bibb. If you don’t already have a backflow preventer on your outside faucet, put one on it.

Pitless adapters are made for installing well pipes in drilled wells. This is not, however, the only practical use for them. They also work very well when used with aboveground cisterns.

Pitless adapters are made to mount in halves. One half on the inside of a well casing, or cistern, and the other half on the outside. To install, drill a hole in the well casing or cistern. The adapter seals the hole and provides threaded connection ports on both sides of the well casing or cistern. There is no better way to make a solid, watertight seal in this type of situation.

Pump systems can be used to feed irrigation systems. If you are tying into an existing well system, you can use the same procedures discussed on page 45. When an independent system is used for irrigation, your connection method will be a little different, though not more difficult.

Assuming that a pressure tank is used with your pumping system (and one should be), there will be a threaded connection from your feed pipe to the irrigation pipe. The connection will be made by screwing a male or female adapter into, or onto, the waiting threads.

There are some pitfalls of which you should be aware. I’ve been working with pipe and fittings for over 20 years, and I’ve seen and made a lot of mistakes. While I can’t protect you from all of the problems you may run into, I can certainly help you steer clear of some of the ones I’ve encountered.

You can get yourself into hot water — literally — if you tie into the wrong water pipe. It’s not too difficult to mistake a hot-water pipe for a cold-water pipe. They look the same, they’re the same size, and, unless you feel the difference, the only way to know which is which is to trace the piping. Since I’m quite sure you don’t want to spray your lawn or garden with expensive hot water, choose your feed pipe carefully. The safest way to be sure that you are dealing with a cold-water pipe is to trace the pipe back to its source. This is the only way to be sure that you are tying into the pipe you want. If you don’t think you could make this mistake, let me tell you about a professional plumber I knew who made an even bigger mistake.

Most houses in Maine are heated with hot-water baseboard heat. Water is heated in a boiler and delivered to the heating units through copper tubing, the same type that is frequently used for potable water pipes. On this particular occasion, the plumber was running water pipes for an upstairs bathroom. When he tied the riser pipes for the bathroom into the pipes in the basement, he mistook one of the heat pipes for a potable hot-water pipe. The result was anything but desirable. Imagine turning on your shower and having dirty boiler water spray down on you. If a professional plumber can make such a mistake, you can imagine how easy it might be for an average homeowner to get confused about which pipe is which.

Putting all of the pieces together to get your irrigation system operational can take some time. Depending on your system, the job could take as little as an hour or as long as a weekend. Don’t rush, and don’t cut into your main water pipe when supply stores are closed or time is short. If you run into unexpected trouble, your whole house could be without water for a while.

Assuming that you are going to start your job on a Saturday morning, the steps might be as follows.

1. Gather all the materials you will need. Have a gate valve handy, so you can turn the water to your house back on sooner.

2. Cut off the water to your home.

3. Cut in the tee.

4. Install a short piece of pipe in the tee outlet and install a gate valve.

5. Close the gate valve and turn the water to your house back on. If you’ve done your work well, there will be no leaks.

6. Once you have the gate valve in place, proceed from the valve to your irrigation feed. If you prefer to work from the irrigation pipe to the valve you can, but I’ve always preferred to start at the valve.

Brass pipe can look like copper pipe. There isn’t a lot of brass pipe still in use, but there is enough to make it worth mentioning. I hate to admit it, but I actually mistook brass pipe for copper pipe on one occasion. My only excuse is that the place where I made the mistake was very dark, and it didn’t take me long to realize what was going on. Even so, if I can confuse brass pipe with copper pipe, with all my years in the trade, you could certainly make the same mistake.

If you suspect that you’re working with brass pipe, trace the pipe to a fitting and see if the joint is made with a threaded connection or a soldered connection. Brass pipe can be cut with standard copper cutters. The pipe will cut harder than copper, but you might not notice the difference. You will, however, know that you are not working with copper as soon as you try to put a fitting on the end of the pipe — it won’t go on.

Should you run up against brass pipe, you must remove a section of the pipe so that female threads are available to you at two ends. Then you can use male adapters and the pipe of your choice to span the distance between the brass fittings.

Bad valves can result in bad experiences. When you close the cut-off valve to the pipe into which you will be cutting, make sure the valve is working by closing the valve and opening your faucets to see if all the water pressure has been cut off. I’ve seen several plumbers fail to take this step and wind up in a wet scene. Old valves don’t always work, especially if they rely on washers for a dependable seal. The last thing you want to do is to cut into a pipe that you think is turned off, but is, in reality, stoked with full water pressure.

If you have a valve that is not working, you may be able to cut your water off at your water meter. If your meter is outside, you will probably need a water key to reach the cut-off. If you are baffled, call your local public works office and ask them to cut your water off, assuming that you get your water from a city main. If you are on a well, all you have to do is cut off the electrical power to the pump. In this case, it will take a few minutes for all of the existing pressure to drain out of your pressure tank, but if the power to the pump is off, the water will stop soon.

It is not uncommon to get dirt in your pipes when working with underground piping. This usually isn’t much of a problem, but if you don’t flush the pipes before you connect your irrigation gear, the dirt may plug up filters and cause all kinds of trouble. Always flush your pipes before you connect your sprinklers or other irrigation gear.