As the federal minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources, Jean Lesage initiated a major expansion of residential schooling in northern Canada.

Library and Archives Canada, Duncan Cameron, PA-108147.

The large hostels

Despite the fact that in 1955, Northern Affairs and National Resources Minister Jean Lesage had written that boarding schools were inappropriate for northern Canada, by 1961 the federal government’s system of large hostels was fully established throughout the North. The hostels replicated the problems that had characterized the residential school system in southern Canada. They were large, regimented institutions, run by missionaries whose primary concern was winning and keeping religious converts. They employed a curriculum that was culturally and geographically inappropriate. While a number of schools developed admirable reputations, most students did not do well academically. Sexual abuse was a serious problem in a number of these institutions. The abuse was coupled with a failure on the part of the government and the residence administrations to properly investigate and prosecute it. Institutional interests were placed before those of the children.

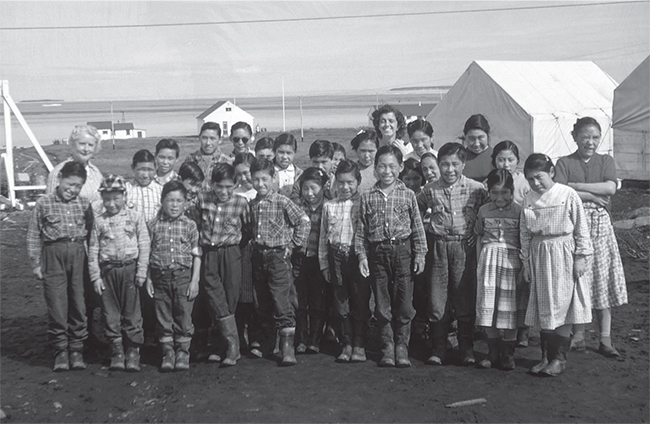

Most of the students who lived in the two Yukon hostels, located in Whitehorse, came from First Nations families. In the Northwest Territories, seven large hostels were located in five communities in the western Arctic: Yellowknife, Fort McPherson, Fort Smith, Fort Simpson, and Inuvik. (Grandin College, also located in Fort Smith, was not part of the federally organized large hostel system and will be discussed separately.) These communities are either on the Mackenzie River and its delta or on the lakes and rivers that flow into the Mackenzie. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit students could be found in all the hostels in the western Arctic. Until 1964, when the Churchill Vocational Centre opened, there was only one hostel in the eastern Arctic: Turquetil Hall at Chesterfield Inlet, on the western shore of Hudson Bay. The limited number of hostels in the East meant that many Inuit children were enrolled in schools and hostels in the western Arctic, particularly those in Inuvik (the most northerly of the communities with hostels in the West) and Yellowknife (which provided students with access to a variety of vocational education programs.) In 1970, for example, Stringer Hall in Inuvik was home to 185 Inuit students who came from places as distant as Iqaluktuuttiaq (Cambridge Bay), Taloyoak (Spence Bay), and Gjoa Haven.1 Yellowknife drew students from across the entire Arctic, including in 1970 from Iqaluktuuttiaq, Kugluktuk (Coppermine), Inuvik, Iqaluit (Frobisher Bay), Bathurst Inlet, and even Arctic Québec.2 In one year the Churchill Vocational Centre housed students from Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), Chesterfield Inlet, Coral Harbour, Arviat (Eskimo Point), Igloolik, Kangiqliniq (Rankin Inlet), Naujaat (Repulse Bay), Whale Cove, Qikiqtarjuaq (Broughton Island), Kinngait (Cape Dorset), Iqaluit, Grise Fiord, Pangnirtung, Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet), and Resolute Bay, all still part of the Northwest Territories at that time, before the creation of Nunavut in 1999. Students also came from Ivuyivik (Port Harrison), Quaqtaq, Kangirsuk (Payne Bay), and Sugluk in northern Québec.3 The distances some of these students travelled are staggering. Inuvik is more than 1,500 kilometres from Taloyoak, while Iqaluit and Yellowknife are over 2,200 kilometres apart.4

The residences were often large institutions. Grollier and Stringer Halls in Inuvik, for example, were built to house 250 students each.5 Initially Akaitcho Hall in Yellowknife was intended to accommodate 100 students, while the Anglican Bompas Hall in Fort Simpson had an initial capacity of 50 and the Catholic Lapointe Hall in the same community had a capacity of 150. The initial staff complement for Akaitcho Hall was ten: a superintendent, a matron, an assistant matron, a cook, an assistant cook, a laundress, a caretaker, a choreman, and two dormitory supervisors (one male, one female). Lapointe Hall, with fifty more students, was allotted three more staff members.6 By the late 1960s at Stringer Hall, for instance, there were two distinct groups of employees. The first included four non-Aboriginal supervisors of the boys’ and girls’ dormitories (one each for senior and junior boys and girls) and a number of Aboriginal assistants to help with the youngest children. The second group, including the nurse and the kitchen and dining room staff managed by the hostel matron, worked in the areas outside the dorms. Most of the hostel staff, except for the dormitory assistants and sometimes some of the kitchen and dining room staff, were not from the North and spoke only English. While the matron and her staff were tasked with supervising the dining hall, the supervisors were in charge of the dormitories.7

By the early 1960s, it was not uncommon for Stringer Hall in Inuvik to have an enrolment that exceeded its capacity. In 1963, for example, it housed 277 students, at a time when the building had a capacity of 250. At the same time, Grollier Hall in the same community had seventy-five empty beds. However, the excess children in Stringer Hall could not be moved into Grollier Hall because they were identified as Anglicans, and Grollier Hall was operated by Catholics.8 In 1964 Stringer Hall was housing 300 students with no immediate relief in sight.9 Not surprisingly a 1965 review of the hostels observed that “the existence of separate and distinct hostels alongside of schools following separate and distinct extra-curriculum programs can only lead to unnecessary and unwarranted duplication.”10 A 1967 medical inspection of Turquetil Hall in Chesterfield Inlet concluded the facility was “grossly overcrowded.”11

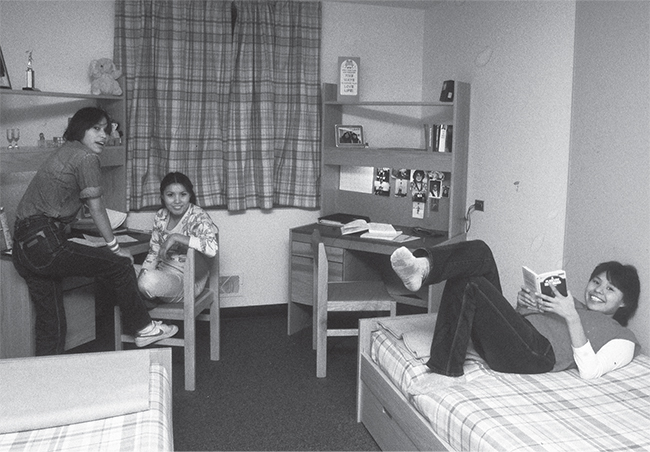

Privacy was limited in many residences, particularly in the early years when the students in most residences slept in dormitories in which the beds were “arranged army-style for fifty or sixty in one room.”12 Residents in hostels at Yellowknife and Churchill enjoyed significantly more privacy and comfort. There, the relatively modern residence buildings featured smaller, four-person rooms.13

Recruitment and resistance

In 1960, the federal government had seven criteria for selecting students to attend northern hostels and residential schools:

•They had to live in an area “reasonably adjacent” to the institution.

•They had to have undergone a medical examination and an X-ray.

•They had to have reached the age of six by December 31 of the year of admittance.

•Priority would be given to those who had attended in the previous year.

•They had to be of the religious faith of the authority operating the institution.

•They had to lack access to a day school or other school facilities.

•Enrolment could not exceed the approved registration for the school.14

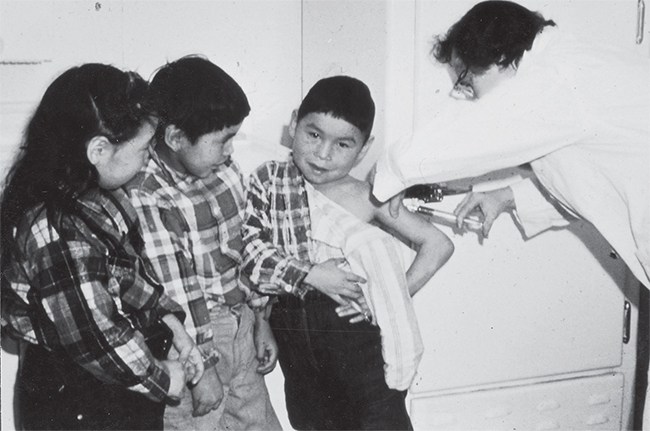

Initially Northern Affairs recommended that before being admitted to the hostels, “Indian children be examined by a doctor and Eskimo children by a nurse.” While this likely reflected the fact that there were few doctors in the eastern Arctic, it did lead one government official to comment that he could not understand “why a doctor is required for Indian children and nurse for Eskimos.”15

In selecting the first students for the Inuvik residences, Northern Affairs relied in 1959 on preliminary surveys carried out by missionaries, Hudson’s Bay Company employees, teachers, and Mounted Police officers. Students were flown to collection points in small planes. From these locations they were flown in larger planes to Inuvik.16

Norman Burgess was in charge of arranging many of these early airlifts. His descriptions of the way in which a girl was collected from her family in a remote area east of Herschel Island is harrowing. The family was on a boat in the water when the plane

landed down beside them right out in the middle of nowhere and took the little girl, screaming and kicking, put her in the aircraft—the mother crying, the father crying, the kid crying, all part of the game in those days—and flew her into Inuvik and put her in the hostel. It was pretty nerve-wracking and I don’t think I could get to where I agreed with it, but nonetheless, there wasn’t that much choice.17

Some children, such as Eric Anautalik, had never seen an airplane before.18 While this may have added a degree of excitement to the journey, several former students remembered the air journeys to, and later from, the hostels as uncomfortable and unsafe.19 Beatrice Bernhardt stated that as a six-year-old she was given neither food nor water during her flight from the Kugluktuk area to Inuvik.20 Paul Quassa, who was also about six years old when he was sent from Igloolik to Chesterfield Inlet, remembered there were no seats or safety precautions taken on the plane: “We just sat on the floor of the plane.” He also remembers children having to urinate in the plane. “I remember there was no washroom, but because we were children we had to go.” Like many other journeys to and from the hostel, Quassa’s first plane journey made several stops along the way, collecting more children at Naujaat and Kangiqliniq: “We just landed along the way. Then we’d lift off and go.”21

“Eyewitness Says: Kidnap Children to Fill School”

The hostels opened to a flurry of negative publicity. In September 1959, the Winnipeg Free Press reporter Erik Watt’s article on school recruitment ran under the headline “Eyewitness Says: Kidnap Children to Fill School.” According to Watt, a resident of Old Crow, Yukon, had told him that children had been, in essence, kidnapped to “fill and thereby justify a super-school that no one in the north wanted except the government and the Anglican Church.” According to Watt, the children from Old Crow had been taken to the new Anglican hostel in Fort McPherson. The article drew attention to the distance children had to travel, parents’ opposition to being separated from their children, and the religious segregation that was central to the system. An anonymous Mounted Police officer was quoted as saying, “Neither church wants its converts tainted by any contact with the other. It’s a fine way to teach them to become citizens.”22

The allegations of kidnapping did not go away. In the early 1960s, Citizenship and Immigration Minister Richard Bell said, “Much publicity has been given to the claim that the Government has been dragging babes from their mothers’ arms and placing them in hostels (all in the name of education). The absurdity of such claims is pointed out by the fact that all pupils in hostels must be of school age, at least aged 6 and that the consent of the parent or legal guardian is a requirement for admission.”23

Consent forms were indeed usually obtained from parents, but at times pressure was applied to get that consent. In 1963 Northern Affairs official W. G. Booth travelled through the Northwest Territories with the Treaty payment party to recruit students for the Inuvik hostels. In one community, parents insisted that, rather than send their children away, they wanted a day school in their community. “At first, it did not seem as though any children would be going to the hostel,” he wrote. However, with the help of the Mounted Police officer, who was there as a part of the Treaty payment party, and the government translator, he succeeded in “getting the signatures of the parents of some six children.”24

In a 1977 article in Inuit Today, Armand Tagoona explained the pressures that were placed on parents to win their consent. He recalled being taken by the settlement manager to act as interpreter for a couple whose daughter was on a list to be sent to the Churchill Vocational Centre. The parents objected to her going, as she had reached marriageable age. The official told Tagoona to explain to them, “‘If you don’t let your daughter go, I don’t want to see any of you in my office at any time. Even if you no longer have any food, you will not be given welfare ...’ The mother and father looked at each other as if in agreement, then the mother said, ‘Okay, let her go.’”25

Norman Attungala recalled that it was a Department of Indian Affairs official who told him to send his son to school.26 At other times, Survivors have explained, their parents sent them to the schools because the government threatened to withhold family allowance payments if children were not sent away.27 In many cases children were simply taken to school without any “prior consultation” with parents or the children themselves. In some extreme cases physical force was used. Eric Anautalik explains the trauma that he felt as a three-and-a-half-year-old being picked up by an RCMP officer and, in his words, “brought into the modern age.”28 As he remembers, “I was in shock, I mean I was taken, literally, I was snatched by the policeman from my mother’s arms ... In that single day, my whole life changed.”29

Mary Charlie from Ross River in the Yukon recalled being rounded up and taken to the Lower Post school in northern British Columbia.

I remember when I went to school I was out in the bush about 14 miles from here and we were living out there and there was a big truck that came and got everybody. I remember one girl, my friend, her name was Agnes ... She didn’t want to go to school so she run half around the lake and it’s a pretty big lake to run around, but they caught her anyway and we went into that big truck. And we never sat down, there was no bench or anything in that big wood truck or whatever but there was no seats in there to sit down, or had any water or anything to eat all day while we run around, pick up kids, and it was dusty and dirty and we didn’t even—I didn’t even know where I was going.30

Angus Lennie, who attended residential school in Alkavik and Inuvik, said his life changed forever when he first entered residential school.

I recall walking as a small boy up to this big building with some clothing. Nobody explained to me what was happening at this point. I remember my parents dropping me off with my brothers and one sister and from a child’s eyes, this was really a strange environment. So, each Sister ... met us at the door and this began my journey into residential schools. A journey I will never forget. Walking through those doors, began the split of our once happy, connected family. Once the doors were shut, that’s when it began my nightmare. Our parents were no longer there to be—to protect us. My sister was taken to the other side, from then we had no contact, with no more playing, sharing stories, and this is the point I really believe in my life that our once happy family began to break apart.31

The experience was painful for the parents. Towkie Karpik recalled that a federal government representative came to Pangnirtung to recruit children for the hostels.

When he came to get the children he was so aggressive and intimidating. I had no choice but to let him take them. I had no choice but to say yes, even though I didn’t want them to go. Who would want that? No one had ever taken our small children from us before. When they took them all of the mothers began to grieve as if our children had died. Believe me it’s the most terrible thing in the world to have someone take your children away and there was no way to stop it. The White man was so intimidating and he came to take our children, our innocent children that we had every expectation of raising ourselves. We thought they would stay with us until they were grown. It was so horrible to be left behind by our children because we weren’t meant to be separated from their children when they were small. They were meant to stay with us.32

Apphia Agalakti Siqpaapik Awa raised her children in the Baffin Island area. Two of her boys went to the Churchill school.

We couldn’t communicate with them because there were no phones, and since we were in the camp, we didn’t get any letters from them. We didn’t hear from them for a long, long time. We didn’t know how they were down there. I remember being so worried about them. Finally Simon wrote a letter that someone brought to us at the camp. He wrote that he was very homesick and that he wanted his parents to talk to the teachers and ask them to let him come home. He wrote that he was scared of the Indians in the school. He was just a little boy. I wrote back and told him that he had to be patient and wait for the time to come home. I wrote to him that he had to wait until springtime.33

Almost as difficult as the separation was the return to the home community after months or years of schooling. Peggy Tologanak illustrates how these broken relationships manifested themselves the moment that children returned to their communities for the summer holidays. Some of the younger children, she explains, had literally forgotten who their parents were: “I remember when we’d land in Cambridge [for the holidays] we’d all be brought to the school and the parents would come up and pick us up. There was a lot of kids that were crying cause they didn’t know who their parents were. They forgot about them.” Older students, although remembering their parents, resented returning to their parents’ home: “Some ... kids didn’t want to go with their parents, they said, They’re so dirty, and they’re so stinking,’ ... and they would be crying and had to be forced to be taken home.”34

The schools were quite conscious of the implications of the changes that they were introducing into northern communities. A handbook prepared for the Churchill Vocational Centre advised:

There must be able acceptance on the part of both the parent and the child that the learning of English and its associated acculturation is a very necessary factor in this further education. The child, when he returns home, will certainly not be the same individual who went to school. He will have a different outlook and might not readily accept what he finds upon his return.35

Once they arrived at the hostel, children were put through a series of procedures to register, wash, and reclothe them. Many Survivors still remember the number they were given on arrival, and several remember the experience of having their own handmade clothing taken from them. Norman Yakeleya recalled that he was given number 297 when he went to Grollier Hall.

I was six years old when I got my number.… You had an older boy look after you and they give you a black marking pen and they put a number on your—you got to put all on your clothes, your socks, long johns, shorts, pants, shirt, boots, and they put your number on you, put your number on your clothes and they didn’t say, “Norman,” they said your number and you got to put your hands up and say, “Here.” So, they weren’t given a name. You were given a number and that’s how you identify yourself. And I thought about this in the bush again. What kind of society does that to people?36

Peggy Tologanak from Iqaluktuuttiaq explained how every year her mother painstakingly made her and her siblings new sets of clothing to wear to school, and how, on arrival, these homemade clothes were confiscated by authorities at Stringer Hall and replaced with manufactured clothing from southern Canada.37 When the nuns at the Lower Post school took her clothes, Marjorie Jack asked, “Well, what are you going to do with my clothes? My mom just made me coats, my mom was a seamstress. My mom made me these clothes, why are you taking them?” They said, “Well, we all have to wear the same things here and we’ll distribute your clothes to you.”38

In more extreme cases, students witnessed authorities burning the clothes their parents had given them.39 Along with removing these “old” clothes, students were forced to shower and have their hair checked for lice; if necessary, they were forced to have their hair washed with a powerful cleaning agent.40 Helen Naedzo Squirrel had a strong memory of how humiliating and frightening she found this process: “Our clothes were taken away from us. They assembled us all in a line and told us to go into the shower stalls. They washed our hair and washed whatever—they thought we had lice and whatever. After that they cut our hair.”41 As Piita Irniq remembered of his first days at Turquetil Hall, this whole process of cleaning and reclothing had an unsettling effect on him and other children: it was as if “we had overnight become White men and White women.”42 For Anna Kasudluak, the changes ushered in by the new clothing were quite literally difficult to bear: it felt “very heavy to be under a new wardrobe.”43

From the official perspective, the students’ home clothing was in need of replacement. Remembering the arrival of students at the Churchill residence in 1964, the superintendent of vocational schooling in the Northwest Territories, Ralph Ritcey, said, “Less than ten had clothing you would use in a regular school.” This teacher explained how he and other staff, assuming they were improving the health of the students, spent the first few days of the school year washing and reclothing the students; some teachers, he noted, “spent twelve to fourteen hours a day washing people and cutting hair, delousing them, burning clothes and refitting them with new clothes.”44 By 1963 the hostels were allotted forty-eight dollars a year for clothing. Parents from Snare Lake in the Northwest Territories complained that year that the students had not been allowed to return home in the hostel clothing, but were sent home in the clothing they came in, “which was pretty well worn out.”45

Regimentation: “We went to a total alien place”

Once washed and dressed, the students were initiated into their daily routine. At the same time the school system was forcing them to conform to a new—and very foreign—type of schedule, it failed to make the children feel loved or cared for.46 Veronica Dewar, a resident at Churchill in the 1960s, explained how her time at residential school, although a success in terms of her experience in the classroom, was marred by a hostel lifestyle that was highly regimented and unable to offer the love and caring she had enjoyed from her parents in Coral Harbour. It “seems like we walked into the army,” she remembered of her first days at the Churchill hostel; it felt “totally cold, and totally different environment than our parents’ homes and we went to a total alien place.”47 Eva Lapage recalled having mixed emotions about her time at the Churchill school.

It was bunch of Inuit from everywhere that were in that residential school. So that’s where I was and there was no way of communicating. And it was exciting, it was fun, but I was very homesick.… Because I was the oldest of the family and they loved me. My parents loved me so much. I was kind of spoiled one, you know, I just cried and I’d get what I want. So I had that and all of a sudden it was cut off.

She said she felt well treated while she was at the school. However, she felt that the school was run in a highly disciplined fashion.

It was army base, that old building and it had many wings and was long way to go to cafeteria and we would have to line up and we were wearing uniform and we all look alike.48

Tables 9.1 and 9.2 outline daily schedules at Akaitcho Hall and Stringer Hall.

Table 9.1.Daily schedule, Akaitcho Hall, 1958

| 6:30: | Students on Breakfast detail rise, wash and report to chef by 7 a.m. |

| 7:00: | All students rise |

| 7:30 – 8:00: | Breakfast |

| 8:00 – 8:25: | Work details |

| 8:30 – 11:30: | Classes |

| 11:45–12:30: | Lunch |

| 12:30 – 1:00: | Free period (smoking, recreation room) |

| 1:00 – 3:00: | Classes |

| 3:30 – 5:00: | Free period (students are free to visit town for shopping etc.) |

| 5:00 – 5:30: | Dinner |

| 5:30 – 6:00: | Free period (smoking, recreation room) |

| 6:00 – 7:30: | Study period |

| 7:30 – 9:30 | Free period (recreation room, gym etc.) |

| 9:30: | To dorm for quiet hour |

| 10:30: | Lights out |

Source: TRC, NRA, Library and Archives Canada, RG85, volume 708, file 630/105-7, part 3, High School Facilities – Yellowknife [Public and Separate School], 1958–1959, A. J. Boxer to J. M. Black, 9 December 1958. [AHU-000005-0000]

Table 9.2Daily schedule, Stringer Hall, c. 1966-67

| 6:45 – 7:30 | Rise, dress and wash |

| 7:30 – 8:00 | Breakfast |

| 8:00 – 8:45 | Clean up dorms, dining room and halls, set up tables etc. Prepare for school. |

| 8:45 – 12:00 | Attend school |

| 12:00 – 1:00 | Return for lunch. After lunch clean dining room, set tables etc. |

| 1:00 – 4:00 | Attend school |

| 4:00 – 5:30 | Play in the hostel, gymnasium and dorms. Play cards (gamble), play guitars. |

| 5:30 – 6:00 | Dinner |

| 6:00 – 6:30 | Clean dining room, wash dishes, etc. |

| 7:00 – 9:00 | Study period in dining room |

| 7:00 – 7:30 | Junior boys and girls prepare for bed |

| 9:00 – 9:30 | Snack in the dorm for the younger students, lunch in the dining room for the older students |

| 9:30 – 9:45 | 13–14 year old students prepare for bed |

| 9:45 – 10:00 | 14–15 year old students prepare for bed |

| 10:00 – 10:30 | All other students prepare for bed |

| 11:00 | All lights are turned off |

Source: Clifton, Inuvik Study, 57.

At the Churchill residence, students rose at 7:00 on weekday mornings, had hourlong meal periods at 7:30, 12:15, and 5:30, and had an evening snack at 8:30. They left for school at 8:45 a.m., returned to the residence for lunch, and went back to school until 4:00. Their recreation periods were from 4:00 to 5:15, and again from 7:30 to 9:00. The period from 6:30 to 7:30 was set aside for studying, and lights were supposed to be out by 9:30. Chores were limited to a daily making of beds and tidying and cleaning of washrooms and weekly washing and waxing of dormitory floors.49

Because the hostels organized dormitory life along lines of age and gender, most siblings slept, ate, and attended schools separately. The tight regulation of male-female interactions, in particular, meant that even if they lived in the same Hall, brothers were rarely able to talk to or visit their sisters and vice versa. Peggy Tologanak, at Stringer Hall in the 1960s, vividly remembers the experience of being separated from her eight siblings at Stringer. “From the moment you walk in until you go home you’re not allowed to see your family members, you can’t sit with them, you can’t hardly talk with them.”50 Christmas at the hostel was a rare moment for Peggy to reconnect with her siblings. “The only time we get together as a family [at the hostel] was on Christmas day,” remembered Peggy.

We’d all get to get up in the morning and run and go see our brothers and our sisters. [We’d ask about] how they were, and then, they would always allow the kids to go into the dining room on Christmas day ... from biggest families to smallest. And every year that I was there, the Tologanaks were always first to be called ’cause we always had the biggest family. And then we get to sit with our brothers and sisters on Christmas day. And we’d sort of catch up because we weren’t allowed to mingle [during the rest of the school year].51

Veronica Dewar explained how being at the hostel robbed her of the opportunity to receive love and caring from her parents: “There was never love around us or caring for us for a very long time.” While the medical services at the hostel may have been superior to what she could have accessed at Coral Harbour, she explained that she could “never even receive hugs” she needed from her parents when she got sick or hurt.52 Without the provision of affection, the hostel, despite its modern medicine and well-meaning routines and activities, was unable to properly care for her and her classmates.

In some instances, encountering the physical layout of the hostel and even the landscape around the hostel was an alienating and unsettling experience. Piita Irniq, accustomed to living in a relatively small family group in the restricted space of an iglu, remembered that noise and especially the size of the open-style dormitory at Turquetil Hall were a “culture shock” for him.53 Likewise, for children raised in the eastern Arctic and sent to schools at Inuvik, Chesterfield Inlet, and Churchill, the physical landscape—most notably the trees—compounded the sense that they were in a foreign place where not just the language and culture of the hostel were new, but so too was the very land on which it was built. One Survivor from Nunavut remembers that soon after her arrival at Churchill, she wanted someone to cut down all the trees “so I could see far enough.”54

Friendship and bullying

Cut off from family, students turned to each other for support. In notes that he took when he worked at Stringer Hall as supervisor in the mid-1960s, Rodney Clifton observed, “Often when a meal is over and the students are returning to their dorm, they put their arms around one another as they walk down the halls,” and once in the dormitories, some of the younger boys would “often sleep together or lay in each others [sic] beds and tell stories.”55 According to Clifton, older boys would similarly talk late into the night: “The grade 11 and 12 students almost [n]ever slept together but they often would lay in each others [sic] beds and talk till late at night. They would relate stories of their ancestors, sexual experiences, hunting experiences and daily news.”56 Some students clearly felt very positive about the friendships they developed at the hostels. Many remembered meeting many good people at the hostels, among both the staff and the student body.57 “I didn’t fit in Grollier Hall,” remembers Beatrice Bernhardt, “except when we had fun with each other and when we were allowed to just be together at playtime.”58 A former resident at Stringer Hall, Eddie Dillon, reflected on the role of friendship this way: “I do regret not being able to communicate with my family through those years [at the hostel] ... but the students we end up going to school with in Stringer Hall, that’s the extended families we have. We share that.”59

Rather than support each other, some students engaged in bullying. Inuit, Inuvialuit (Inuit of the western Arctic), and First Nations girls were all targets of bullying by members of the other groups, and sometimes by members of their own groups. Beatrice Bernhardt remembers that, more than any of the things the staff did, the “biggest abuse [at the hostel] came from other students.” She bitterly remembered how she was called “dumb,” “stupid,” and “dirty Eskimo” at the hostel. They were “wicked, wicked mean,” Beatrice said of the girls who teased her.60 Girls coming from the central Arctic had similar stories of being tormented by other girls. Peggy Tologanak said that Gwich’in as well as Inuvialuit girls teased her during her time at Stringer Hall. She remembers being called “dirty and stinking.”61 Likewise, Jeannie Evalik, from Iqaluktuuttiaq, was targeted as an outsider when she went to Inuvik. She specifically remembered a staff member calling her a “stupid Eskimo.”62 Other girls felt they were bullied because of a handicap. Marjorie Ovayuak says that while she got along with most of the other children at Stringer Hall, she was teased because she suffered from hearing loss in one ear.63

Judi Kochon recalled how a group of older girls at Grollier Hall bullied a younger girl into stealing candy for them.

That whole time that she was gone, like I felt so bad, you know like, I knew I couldn’t do anything but I felt so bad for her because I knew what she would go through if she got caught. But she came back with the candies and that, but just it took so long for her to come back so it was just like, for me it was just an agony just waiting for her to come back and that nothing would happen to her.64

Students often had trouble adjusting to hostel life. In reporting on the discharge of five “problem students” in Akaitcho Hall’s first semester, administrator A. J. Boxer recommended “greater care be exercised in selecting students for the hostel. It is entirely improper to place delinquent and immoral people among wholesome, developing teenagers.”65 In approving a student’s request to be allowed to return from Yellowknife to his home community, Sir John Franklin School principal N. J. Macpherson said he felt that “a more careful selection would prevent this recurring problem of students finding themselves unwilling or unable to adjust to life here.”66 In writing about the difficulties that students had in adjusting to hostel life, a child care worker at the Ukkivik hostel in Iqaluit noted in the early 1970s that for many students, the residence housed

more people than exist in their entire home community. Most have never been among so many people of their own age before. The new environment requires adjustment. There are no grandparents or parents to answer to. There are no babies and small children to care for. The boys cannot go out hunting. Even the traditional visiting become hazardous in Frobisher Bay where alcohol is passed out freely and girls are continuously accosted by drunks.67

Food

It is apparent that the food in the hostels, when compared with the diets served in the mission residential schools of the 1950s, represented a significant improvement in both quality and quantity. Alice Blondin-Perrin, who had attended the St. Joseph’s Catholic residential school in Fort Resolution, transferred to Breynat Hall when it opened in Fort Smith. In her memoirs, she recalled that food improved dramatically. At Breynat Hall students were served “hot lunches of soup, stew, shepherd’s pie, bread, and milk. The stew was made from various meats, always prepared well and always tasty. The dinners were always delicious, with mashed potatoes, meat, meatloaf, or fish, and vegetables. I could now eat cooked carrots, beets, turnips, and peas which I used to hate the taste of, but now loved.”68

A 1965 review of the hostels in the Northwest Territories concluded, “The food received by the residents is excellent in both quantity and quality.” Students were being fed in keeping with the Canada Food Guide and “the administrators have used their collective imaginations and skills to give the children more than the minima called for by the guide.” The supply of milk, fruit, vegetables, cereal, bread, ice cream and butter was judged ample.69 But while quantity and quality had improved, it was, as Blondin-Perrin’s comments reveal, a southern diet. It was not one that students adjusted to easily. In the early 1970s, a child care worker at the Iqaluit hostel wrote that, while the food was adequate by southern standards,

the Eskimo diet is not the white man’s diet. Ham hocks and sauerkraut do not appeal to the students the way seal, char and caribou do. As a result much of the food is going into garbage cans instead into stomachs. The difference is being made up in soft drinks and chocolate bars.70

After initially tolerating some traditional foods, the government had in fact banned country food from the residences. In 1961 students at Turquetil Hall were being fed two meals of raw fish and two meals of raw beef a week. The meat was not traditional northern caribou but rather beef that came from a Winnipeg packing plant; the fish was caught locally. The residence principal, René Bélair, was a strong supporter of the practice. He said that none of the children had become ill as a result of eating raw food. “Do not forget that they are eskimos and not white: They like it and it is good for them. This is one thing that you will never be able to stop, is to stop an eskimo from eating raw meat. It is just like ice cream to us.”71 Medical advice provided to Indian Affairs concluded that such a diet was a threat to the health of the children since the meat could be “infested with worms that can cause illness, incapacity, and in some cases death.” R. A. Bishop of Northern Affairs informed Bélair that he believed the school had no choice but to accept the medical advice not to serve children raw meat even though the decision would not be popular with the students.72 As result, the practice of serving raw meat and fish was halted at the school in the summer of 1962.73

In 1961 the students at the Anglican Stringer Hall in Inuvik were being fed frozen raw whitefish once a month and raw reindeer meat about once a month as well. Residence administrator Leonard Holman said that discontinuing the serving of raw foods, which he said was provided as a “special treat,” would not cause any problems.74 In a separate note, Holman questioned whether raw, frozen food was as dangerous as federal government officials claimed, pointing out that “it was men from the same Department who advised and recommended that we include these items as a ‘special’ in our diet and that they would be perfectly safe.” He also relayed the following story:

Over a year ago in the midst of the Measle epidemic, one little Eskimo lad from a very primitive section was really very sick and was showing no sign whatsoever of recovery. Just lay there with a high fever not even wanting to drink. We have on our staff an Eskimo lady, Mrs. Annie Anderson, who comes from the Coppermine area and knows their dialect, so whenever there is sickness she leaves her sewing and goes in to help the Nurse, and talks away to them in their own language, which we have found to be very beneficial. He called and asked her to please get him a piece of frozen caribou. None was available so she slipped downstairs and came back with a little piece of frozen Reindeer. He fairly grabbed it out of her hand, pushed it into his mouth and lay there sucking and chewing on it. This was the turning point on the road to recovery. Just a little taste of ‘home’ from one of his own, who knew and understood.75

By the end of the first decade of operation, the diets were almost completely southern in nature. In 1970 this was a typical daily menu at Stringer Hall:

Breakfast |

puffed wheat, toast, jam, milk |

Lunch |

grilled cheese sandwiches, canned tomatoes, plums, milk |

Dinner |

roast beef, gravy, mashed potatoes, peas, ice cream, cookies (home made), milk.76 |

In the 1990s there were attempts to reintroduce traditional food. In 1990 Anglican pastor Tom Gavac reported that at Akaitcho Hall “many students wish that more traditional, customary foods were served—namely caribou and fish.” When he inquired into the possibility of serving such food, he was told that such meat could not be served unless it was government inspected, a process that was deemed to be too costly. Gavac said it was “almost inconceivable to me that youth who normally consume caribou and fish (often every day in the home community) cannot have such items at least once weekly.”77

Many students had a great deal of difficulty adapting to the southern diet. The food at Turquetil Hall was remembered as very repetitive and poor: breakfast was always porridge, and lunch was some combination of sandwich, soup, and tea.78 Without any real choice, however, the children were forced to adhere to this institutionalized food.

Health care

In 1960 the Indian and Northern Health Services of the federal health department recommended that there be a registered nurse for every hostel with a capacity of 200 students or more. For isolated hostels, it was recommended that there be a nurse available even if the enrolment was less than 200. Fulfilling this recommendation required the hiring of nurses in Inuvik and Fort Smith. It was thought that the matron at Turquetil Hall would be able to provide adequate nursing care as long as she was an “alert motherly person who is highly reliable” and had “a knowledge of home nursing and first aid.”79

In the hostels with more than 100 residents, it appears that students had access to a level of medical care far superior to what had been available in the older residential schools. The first matron at Akaitcho Hall was a registered nurse. From the outset the local schools arranged for the X-raying of students and eye tests. A local doctor was able to extract teeth, but it was felt that the services of a dentist were urgently needed.80 At the Churchill Vocational Centre a sick parade (to which students who were feeling ill could report) was held each morning, the hostel matron was a registered nurse, and a public health nurse was available three half-days a week. The hospital was about 200 metres from the school, and appointments with doctors and dentists were arranged whenever necessary.81

The initial plan was for the Anglican hostel at Fort Simpson to be covered by periodic visits from an Indian and Northern Health Services nurse, while the Roman Catholic hostel could be covered by the staff of the outpatient department of the local Roman Catholic hospital.82 In operation the system was far from ideal. When a boy with tuberculosis was admitted to Bompas Hall in Fort Simpson in December 1963, the administrator, Ben Sales, protested. He pointed out that the boy was supposed to receive large doses of medicine each day for seven months. Sales wrote, “We have no professional nurse on our staff to be responsible for this medication.”83

Contagious illnesses spread quickly in large dormitories. Initially infecting four students, a 1959 outbreak of the measles affected seventy students at the two Inuvik residences.84 The following year there were twenty cases of a “mild epidemic” of influenza among the children at the same residences.85 Another urgent report went out in 1961 stating that there were 106 cases of influenza in the hostels.86 Ninety-three students came down with influenza in Fort Simpson in 1963.87 Three years later an influenza epidemic hit both Fleming Hall in Fort McPherson and Bompas Hall in Fort Simpson, leading to the cancellation of an Easter Festival at Fort Simpson.88 First aid and medication were available from infirmaries in each of the Whitehorse hostel buildings in 1971, but neither infirmary had beds, making it impossible to separate children with infectious illnesses from the rest of the student body.89 Despite these problems, a 1965 assessment of the Northwest Territories hostels concluded that the hostels all had “excellent infirmaries for boys and for girls.”90

Policies on the reporting of illnesses to home communities appear either to have been non-existent at first, or to have not been properly communicated to staff. When a girl from Qamani’tuaq was hospitalized with suspected appendicitis in the fall of 1964, the residence administration did not inform the girl’s family. Students, however, sent letters to the community that led her mother to believe that the girl had been hospitalized because of injuries received in a playground altercation. As can be imagined, this caused the mother considerable anxiety. In apologizing for the delay, the Keewatin regional superintendent of schools wrote, “Procedures for reporting hospital admittances to me have now been established and you can be assured that such reports will be forwarded to home settlements in the future.”91

The parents of a boy from the Kangiqliniq (Rankin Inlet) region discovered that their son had been hospitalized with pneumonia in late 1978 only when another student phoned his family with the news. This apparently was only the latest in a string of failures to communicate such news. Melinda Tatty, the vice-chair of the Rankin Inlet Community Education Committee, said that in the past students had been hospitalized, treated for broken bones, and even undergone surgery without their parents being notified. “A phone call informing the parents of a sick or injured student right away and a follow up phone call on the student’s progress and eventual recovery for a serious illness is not too much to ask.”92

Over time the buildings began to deteriorate, creating health and safety hazards. An inspector judged the sanitation system at the school in Deline (Fort Franklin) “inadequate and unsanitary” in 1965. Waste from the school was pumped into a ditch that drained into Great Bear Lake at a point just 200 metres from the intake that supplied the school with water.93 Conditions in a temporary classroom structure in Inuvik in that year were so serious that an inspector contemplated closing the building. The girls’ lavatory consisted of buckets with plastic liners and lacked a working fan, while the barrel from which students got drinking water was rusty and coated on the bottom with a deposit of yellow sludge.94 There were also problems at the school in Fort Simpson. There, students were still using two “small and very inadequate” buildings that, according to an Anglican Church official, had been “condemned as unfit for use.” The smaller of the two—a one-room, poorly ventilated unit used to instruct twenty-three children — had both an oil stove and a badly leaking oil tank. It also lacked drinking water and a toilet, forcing children outdoors to use the other building’s facilities.95 A call for their replacement would not be heeded until 1970.96

By the early 1970s there were growing concerns about the condition of Fleming Hall in Fort McPherson. A 1973 inspection described the residence as being “in poor condition, and ill-kept, cleanliness having been ignored in some areas.” For example:

•The first floor “stairways and fire exits were dirty, some contained broken glass and food and garbage on the floors.”

•The games rooms had “dirty walls, floors and ceilings.… A torn mattress with exposed springs was being used for tumbling.”

•The girls’ washroom had “two of 6 water closets not functioning” and “five of the 6 stall doors broken off hinges,” and “toilet paper was lying on the floor” due to a lack of dispensers.97 In 1975 federal Public Works officials concluded that “much of the plumbing is very close to rotten as [are] some parts of the electrical system.”98

An improvement on the mission schools

Students who were transferred from the old mission residential schools tended to have positive assessments of the new hostels. In her memoirs, Alice Blondin-Perrin, who had attended the Fort Resolution school, wrote of Breynat Hall in Fort Smith:

Everything looked huge and new, compared to the old St. Joseph’s Mission. The most beautiful Christmas tree stood in the little girls’ play area. It was nicely decorated with colourful lights, in the freshly painted new residence. There was only Father Mokwa and I as he personally toured me around until we reached the dormitory. A Grey Nun was there. They showed me the brand new beds, much bigger than the cots we had in Fort Resolution, with brand new sheets, spongy pillows, and bedspreads. It all looked so clean and attractive to sleep in. We had our own lockers to store our personal things.99

Albert Canadien had gone to the Fort Providence residential school as a young boy. He attended Grade 10 in Yellowknife, while living in Akaitcho Hall.

Instead of the large dormitories that I was accustomed to, we were assigned four to a room. There were two sets of bunks, closets and dressers, and desks by the window for doing homework. There, I lived and went to school with Inuit, Métis, white, and even Chinese students. This was quite a change for me from the residential school days. Living at the hostel at that time proved to be a good experience for me in later life. It taught me to get along with and respect people from other cultures, to treat them like you would anyone else.100

Canadien appreciated the fact that the students were no longer under close supervision. “We had freedom, based on an individual honour system. This was a great improvement from the residential school system.”101

After his time in the Coppermine tent hostel, Richard Kaiyogan said life at Akaitcho Hall was “like staying in a Four Seasons Hotel.”102 Florence Barnaby did not care for the year that she spent at Grollier Hall, the Roman Catholic residence in Inuvik. She did, however, enjoy her time at Akaitcho Hall.

It was good there because everybody was mixed up. It just ... they didn’t separate the Catholic, the Anglican, and the Protestant. And we—I came home for summer, and then go back again to Akaitcho Hall. And I liked Akaitcho Hall because we have dances every Friday night, you know, and it was good. We eat with the boys. It was, no, “You can’t, you have to sit by yourself, or boys this side.” It wasn’t like that.103

Willy Carpenter went to a mission school at Aklavik and then to the hostels and day schools at Inuvik and Yellowknife. He said that life in the mission school was “the hardest part of my life; I was very young and just like—I was treated like an animal. I was treated like an animal. They even fed us like animals.” Stringer Hall in Inuvik was, he said, “totally different from Aklavik. And from Stringer Hall I went to Akaitcho Hall; that one was just like living in a hotel, you know.”104

Steve Lafferty stayed only a short time at Breynat Hall and was sent home because he was too lonesome. When he later went to Lapointe Hall, he said, “I liked it because we played lots of hockey, and then there, too, they gave me a job.... I liked to work, they knew I liked to work, so I used to work in the kitchen a lot.” He also liked the fact that the boys were allowed to go out on the land to snare rabbits. Many lifelong friendships were developed at the school. What he recalled about Akaitcho Hall was the fact that it was “totally free.”105

Other students who had no experience of the old residential schools had positive assessments of Akaitcho Hall. Brenda Jancke and Bernice Lyall, who both went to Akaitcho Hall in the 1980s, shared several positive memories of their school experience. Brenda Jancke remarked that although she recognizes that many Inuit have lost their ties to traditional knowledge, she “didn’t really have a bad experience at all” at school, and was able to retain her traditional knowledge thanks to her father who had never been away to school.106 Bernice Lyall praised many aspects of her time at Akaitcho Hall when she was seventeen: “We had a great time,” she stated. She especially remembered the sports—volleyball and hockey—and the excellent staff at the school: they had the “best teachers, best educators,” she remembered.107

Aboriginal children often received a hostile reception in the public schools. Leda Jules said the transfer from the isolated residential school at Lower Post to Coudert Hall in Whitehorse came as a shock. “I never knew white people before until I went to the Coudert Residence in Whitehorse where we still stayed in a residential school but we went to a public school next door, Christ The King High, that’s where I first encountered racism.” When a boy in the school called her a ‘squaw,’ she fought back. “I remember Sister Agnes used to hit us with yard sticks trying to break us apart, I was a real scrapper back then too, but I wasn’t going to… I wasn’t that little obedient, little kid that came out of Lower Post anymore, you know?”

The role of the churches in hostel life

Even though the hostels in the Northwest Territories and the Yukon had been paid for and usually designed by the federal government, missionaries continued to play a major role in residential schooling. Most of the hostels, for example, were operated, at least initially, by either the Anglican or Roman Catholic church. The continued influence of the churches was reflected in the hostel names. Initially the federal government wished to name the schools after northern explorers and the hostels after First Nations or Aboriginal figures. This was the model that was followed in Yellowknife, where the school was named for Sir John Franklin and the hostel for the Dene Chief Akaitcho, who served as a guide to Franklin.108 The Roman Catholics preferred that the hostels they administered be given names that would indicate that the hostel was under church management.109 As a result the church-administered hostels were named after Catholic or Anglican missionaries. At Chesterfield Inlet, Turquetil Hall (named after an Oblate missionary, Arsène Turquetil) was built alongside Joseph Bernier School (named for the leader of twelve Canadian government expeditions to the Polar Seas). In Inuvik, children lived at Grollier Hall and Stringer Hall, named respectively after a Catholic missionary, Father P. Grollier, and an Anglican missionary, Isaac Stringer. They attended Sir Alexander Mackenzie federal school (named for the fur trader whose travels took him down the Mackenzie River to the Arctic Ocean).110 In the Yukon the Protestant hostel was simply Yukon Hall, but the Catholic residence was Coudert Hall, after Bishop Jean L. Coudert.111 It was only in 1971, with the opening of the Ukkivik hostel in Iqaluit, that the practice of incorporating Aboriginal names and languages in the naming of hostels was revived.112

While the Churchill school and residence were meant to be non-denominational, both the Anglican and Catholic churches still expected to play a role in their operation. Anglican Bishop Donald Marsh was alarmed to discover that five Anglican boys from the communities of Igloolik and Foxe Basin had been housed in the Roman Catholic dormitory at Chesterfield Inlet, as a stopover en route to school in Churchill. Housing the boys in “that environment” did not give Marsh confidence that “they are being looked after as Anglican children.”113 In 1964 Roman Catholic church officials complained that not enough was being done to ensure that Catholic students were not living in dormitories that were supervised by non-Catholics.114 The residence had arranged to house Catholic boys in separate rooms from the non-Catholic boys. However, in the opinion of Father R. Haramburu, this was not sufficient.115

Even at such non-denominational hostels as the Churchill Vocational Centre, students were expected to attend chapel on Sunday. In 1970 Catholic and Anglican officials, alarmed by a drop in the number of students attending local church services at Churchill, asked that the school implement an existing government policy of giving assignments to students who did not attend church. Such assignments, they said, were to be seen not as punishment, but “as a means to make clear that the time for church services is not to be used as they like.”116 The actual policy stated that children who did not attend church could be assigned other duties such as supervised study or “some light duty.”117 For his part, the school principal, F. Dunford, resisted the measure, since in his opinion such assignments “would be a punitive or retributive act.”118

In 1969, the government provided the following assessment of the policy of church management of the schools. Church management, it was argued, had provided:

1)Superior care in the terms of personalized concern and human understanding have been provided by a group of dedicated people that could not be duplicated;

2)The cost of operation has been less than could be achieved under government control; and

3)Although hostels for persons of a particular belief have a divisive effect in a community, religious bias has been kept to a minimum and appears to be growing less rather than more over the years.119

Given the ongoing sexual abuse at a number of church-run residences, it is hard to accept that church-run hostels provided “superior care.” The assertion that religious bias had been kept to a minimum is debatable: the statements of former students make it clear that Catholic students were taught to be suspicious of Protestants and vice versa. Undeniably, though, the churches did save the government money over the years, drawing on the cheap labour that came with many of their religious orders, and thus operating the hostels for many years for less than it would have cost the government to run them.

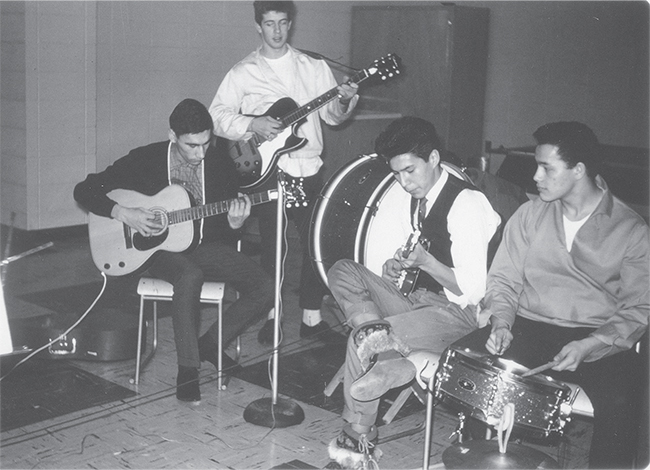

Extracurricular activities

Compared with the mission schools, the hostels, with their gymnasiums and skating rinks, provided students with an improved range of extracurricular activities. The federal government provided $10 per student per year to help pay for extracurricular activities—an amount Anglican Church representative Henry Cook judged to be ridiculously small in 1959.120 According to one observer at Inuvik in the 1960s, the sports teams were almost exclusively made up of Aboriginal students.121 Grollier Hall was equipped with a swimming pool, a covered arena, and a variety of gymnasium equipment that had been purchased through Roman Catholic fundraising efforts.122 When the Oblates ended their involvement with the management of the residence in 1987, they sought to donate the facilities to the Northwest Territories government.123 Following a series of ski clinics in 1965 and 1966, Grollier Hall was also the centre of the Territorial Experimental Ski Training (TEST).124

From the outset Akaitcho Hall had a student council that was responsible for writing a column in the local newspaper, organizing dances, and representing student issues. It was funded by revenue from a soft-drink machine.125 Athletic recreation included skating, hockey, and basketball.126 There were also square dancing, hot-rod, science, rifle, fine arts, radio, and newspaper clubs.127 Among the sports activities available at the Churchill residence were skating, hockey, broomball, bowling, and basketball. Students could also take part in amateur radio and chess clubs, gymnastics and square dancing groups, choir, Boy Scouts, and Cadets. As well, there were Friday night dances and Saturday afternoon and evening movies at a movie theatre in the residence.128 At Turquetil Hall in 1957, recreational evenings were held at the day school and the hostel, giving children a chance to engage in such activities as board games, singing, listening to music, bingo, and ping-pong.129 Northern Affairs official J. V. Jacobson applauded the establishment of a Boy Scout troop at Turquetil Hall in 1959, saying that it “should help a great deal to round out the education being given the boys of this community.”130 In 1963 the Cubs at Fleming Hall were looking forward to a weekend of camping at the beginning of May. Earlier that year a large caribou herd had passed through the region, making it possible “for many of the older boys in the school to go with their parents for a short hunt, and have the thrill of shooting their first caribou.”131

Some students had positive memories of the new opportunities and experiences that were part of hostel life. At the Churchill hostel, Paul Quassa enjoyed movie nights, listening to Hockey Night in Canada, ice skating, and playing basketball against teams of non-Aboriginal boys from northern Manitoba: “We were very short as Inuit, and the qallunaat [non-Inuit/White people] were very tall! [But] we beat them all.”132 David Simailik remembers playing in a rock band, and several others remember the good friends they made in the dormitories.133

Alex Alikashuak had positive memories of the amenities available at the Churchill centre.

Our school, it used to be, like, an army camp, so it already had everything.... Our dormitories used to be the old army barracks, and all these dormitories were connected by a long utilidor system, that connected to what we call the recreation hall. Then you go further down, it was connected to a theatre, like a full size theatre, like the ones they got today, we had one of those. And then at the end, you had a main floor and a second floor that were, like, convenience stores. Like, you know, we had a little coffee shop there. We had a little this, we had a little of that.... We were very, very well, well equipped. I don’t know how to put it. We had everything. Like, we had, like a gym, where people could go and play basketball, volleyball, or whatever they do in the gym.134

Betsy Annahatak had similar memories. She went from Kangirsuk, in northern Québec, to the Churchill Vocational Centre, when she was in her early teens. “I had fun. I thought I had fun. I went to school, it was exciting. We had recreation activities, volleyball, basketball, movies, all these exciting activities. And at the time I thought, ‘It’s ok, it’s good, it’s fun, we’re young.’”135

An early concern was the fact that few students had any spending money. Akaitcho Hall administrator A. J. Boxer said the lack of spending money had “been contributory to some troublesome petty thievery in the dorms where no locker facilities are provided.” To combat the problem, he put in a request for locks that students could install on their dressers.136 In 1965 Northern Affairs authorized the provision of a dollar-aweek allowance to be given to hostel residents age fifteen and over who had “no other source of money.”137

Fewer resources were available for non-sports-related activities. In a 1965 review of the hostels, University of British Columbia education professor Joseph Katz observed that the fact that most hostels were equipped with adequate playground and athletic facilities meant that “other types of programs are lost sight of.” He recommended the introduction of more “music, painting and sculpture, weaving, knitting, beadwork, sewing and similar activities.”138

While the students enjoyed their participation in these games, sports, and clubs, from the Northern Affairs perspective all such extracurricular activities were valued for their assimilative benefit. A policy document from 1964 observed that Northern Affairs encouraged “Scouts and Guides, Cadets, hobby clubs, film showings, interschools competitions, field days, as some of the activities which offer these students opportunities for acculturation experiences beyond those given in school.”139

At the beginning of January 1977, an inspection of Lapointe Hall identified the need for more staff training and direction for sports and recreation programs.140 It does not appear that these recommendations were acted upon. When four students from the residence appeared in court in Fort Simpson in late 1977 on charges of theft from a private home, the local magistrate asked for a Mounted Police investigation into conditions at the residence. In reporting to the territorial commissioner on the development, Brian Lewis, the Northwest Territories director of education, wrote, “I expect considerable repercussions over this issue since we cannot expect a positive report.”141 The report highlighted the limited number of recreational activities available to students. “Nearly every student mentioned that lack of activities was their major drawback to hostel life. The students claimed that they were bored sitting around the hostel with nothing to do.”142

Disciplinary regulations and practice

There appears to have been no overall Northern Affairs policy on the rules covering student behaviour or regulations to govern discipline in the residences. As a result each institution established its own policies. Corporal punishment was not banned in the Yukon until 1990. The Northwest Territories government banned the practice in 1995.143 In reporting on the establishment of Akaitcho Hall in 1958, the resident administrator, A. J. Boxer, wrote, “We have granted wide freedom to students on town leave. A large percentage have not abused this privilege: and for those who have, we have made progress in establishing satisfactory preventative measures through prolonged detention periods; and in serious cases, indefinite detention—unless supervised—has been imposed.”144

In 1962 a number of girls announced that discipline was so severe at Akaitcho Hall that they planned not to return to the residence. According to an investigation carried out by the regional superintendent of schools, a number of girls felt the girls’ head supervisor was overly strict. Staff members felt that the supervisor was both hard-working and dedicated, and noted that her strictness was a product of her “devotion to the girls in her care, for whom she feels great responsibility.” It was also said that many students willingly went to her for advice and counselling. However, it was also thought that she had a tendency to pick on certain students and remind them of their past misdemeanours and, as a result, “created an air of tension in the dormitory.”145

At Stringer Hall in the late 1960s, privileges could be withdrawn from an individual or a group, such as a whole dormitory. Failing that, corporal punishment was used, albeit rarely. In these circumstances, it was left to the hostel administrator to carry out the punishment, although there were instances when supervisors would slap or hit children without the sanction of the administrator.146 These forms of punishment, especially corporal punishment, were resented by students who had grown up in a culture where children were rarely struck. As one supervisor observed, the “white people in the hostel impose an alien form of control which is harsh and severe to the children.”147

Residences that took in younger students appear to have employed harsher disciplinary practices. In the Yukon, the Carcross school operated in the manner of a traditional residential school institution. Discipline was strict, and the church staff exercised considerable control over the facility. Of his year as a teacher at the Carcross school in the early 1960s, Richard King wrote:

Punishments are usually more severe than one cares to encounter. Beatings can be endured, but beatings are infrequent. The most frequent punishments are removal of privileges, confinements, or isolation—all of which involve serious damage to one’s image with others, as well as to his own ego. It is therefore often necessary for children to lie when discovered in any behaviour that was not specifically directed.

Because children would not reveal who among them had broken any specific rule, administrators imposed group punishments. “Once the entire boys’ dormitory was put to bed immediately after dinner for a month—including movie nights—because they had not remained silent after lights out, and nobody would reveal who had been telling stories in the dark.”148 In 1964, a teacher at Carcross, I. M. McCoy, complained to Indian Affairs about the way some of the other staff members at the school were treating students. She pointed in particular to one who hit young children on the head with a rolled-up newspaper if they got out of line during the bathroom parade. McCoy felt persecuted by other teachers when she stood up for her students and left for a position with a public school.149

It appears that at the remote Chesterfield Inlet school and residence, conditions also resembled those of a more traditional, punitive residential school. In her 1994 report on physical and sexual abuse at the Joseph Bernier school and Turquetil Hall residence in Chesterfield Inlet, the lawyer Katherine Peterson wrote:

From the detailed investigations conducted by the RCMP, there have arisen 115 allegations of physical abuse. Some of the allegations of assault take the form of overzealous discipline such as strapping or striking of students with rulers, yard sticks or spanking. These forms of discipline at times exceeded reasonable measures. In addition to this, there were allegations of physical assault which resulted in injuries to the students. One teacher in particular, who was not a member of the Roman Catholic Institution, was well known for his harsh and overzealous discipline. Experiences related to me included students being thrown against classroom walls, a student being picked up physically from her seat by her ears. Shortly thereafter she suffered bleeding and discharge from her ears although it is difficult now to establish whether this was as a result of this action. Students reported being struck repeatedly about the face, back, shoulders, back of the head and buttocks. One child recalled being removed from her seat by her hair. In addition, my review of statements provided to the RCMP indicates one allegation of physical assault involving a child being placed in an automated bread mixer and left in that machinery for an extended period of time. Bruising and lacerations resulted from this. A further statement has been obtained by the RCMP respecting a student being thrown through a classroom window.150

In some cases it was felt that the administrators had failed to impose or maintain order. In 1966 a federal government official concluded that conditions at Yukon Hall in Whitehorse were so out of control that the school administrator needed to be dismissed. Among the examples he gave of lack of discipline at the school were “comments by students and about the Administrator, older students reporting in under the influence of alcohol, older students in possession of alcohol in the Hostel, deliberate baiting of the Administrator by the pupils as they walked down the halls.” Staff complained that the hostel administrator laid down rigid rules but did not enforce them when staff identified violations of the rules. In one case no disciplinary action was taken after a student struck the principal. The unnamed author of the report recommended that “the administration of the Hostel be turned over to a church group,” preferably the Anglicans.151

The residence administrators had to determine which behaviours to ban and which to accept. Because so many students smoked, the Catholic hostel in Whitehorse established a smoking lounge. This was seen as being preferable to students smoking in the dormitories, where it would create a fire hazard. Students who brought alcohol into the hostel were at risk of expulsion.152

The haphazard nature of rule making came to national attention in March 1969 when Ron Haggart, a columnist with the Toronto Telegram, described the rules governing Akaitcho Hall as examples of “apartheid and paternalism.” At meals students were to confine their conversation to their own table, girls were not to wear slacks or jeans to the cafeteria, and soap and toothpaste would be issued only “on production of remains of previous issue.” Students required permission to leave the residence. On Sundays, they could not leave unless they had first attended church service because “religious teaching and practice has ever been a significant part of life in Canada’s north.” Student also needed permission to bring guests into the hostel: they were to be “limited to one guest per month.” Students who brought cars to the hostel were obliged to turn their keys over to the administration since they were not allowed to drive their vehicles while in residence.153 In defending the rules, the best that Indian Affairs Minister and future prime minister Jean Chrétien could say was that “over half” of the approximately 180 residents were eighteen or younger. He also rejected implications that the rules were racist by pointing out that seventy of the residents were non-Aboriginal.154

Within a month of Haggart’s column appearing, a student council was established at Akaitcho Hall and the rules were subjected to a review.155 In private correspondence, Stuart M. Hodgson, the commissioner of the Northwest Territories, blamed the controversy on Steve Iveson, a member of the Company of Young Canadians (a federal government community-development agency), who had been in contact with a number of dissatisfied hostel residents. Hodgson added that unfortunately it had been necessary to discharge two of these students from the residence.156 They had been involved in a verbal confrontation with residence officials when they attempted to read out a statement critical of the Akaitcho Hall administration in the school lunchroom. The girls, who were judged to be capable students, were discharged, but a decision was made to provide funding to allow them to board at a private residence and finish their schooling.157

When he reviewed the new rules, Chrétien congratulated Hodgson for removing “questionable items” from the previous rules. He did observe that a proposed rule prohibiting students from consuming alcoholic beverages “anywhere and anytime” during the period that they were living at the residence “trespassed the personal rights of students who are over the age of 21.” He suggested that the rules simply ban the use of alcoholic beverages in the hostel.158 The finalized list of regulations was only five pages long (the previous rules had been twenty-seven pages) and contained none of the provisions that Haggart had ridiculed.159 The new rules were not always applied consistently. In the 1980s supervisors who had grounded a student for violating a residence rule might discover that an earlier supervisor had, without consultation, lifted the measure. As the residence administrator noted, this practice was rendering “the discipline procedure ineffectual.”160

When asked for a copy of Stringer Hall’s residence guidelines in 1969, administrator Leonard Holman said there were no written rules. However, from his letter it is apparent that there was a set of expectations about student behaviour. Students were expected to be on time for meals, could chew gum anywhere but in the chapel and the dining room, and could smoke if they were sixteen or over (fifteen-year-olds could smoke if they had a note of permission from their parents). They could invite friends for meals and to spend the weekend at the hostel, and in turn could eat meals or spend weekends with friends—providing notice was given in advance. Older students could stay out late one night a week—but were expected to be back by midnight. Holman was proud of the fact that the majority of students respected this rule.161 For example, on a Friday night in 1967, 104 students from Stringer Hall signed themselves out to attend movies or a local basketball game. Of this number, all but one student returned at the end of the evening: the one who did not return had decided to spend the night at an aunt’s house.162 Holman told students who had reached the legal drinking age that while they were legally entitled to frequent beer parlours, he preferred that they did not.163

Within months of a new residence administrator being appointed in 1974, Stringer Hall students submitted a petition calling for the dismissal of the assistant administrator. According to the petition, the official had assaulted students who lived in the residence and blackmailed them into doing things they did not wish to do.164 Although a number of the students later signed a document saying that they wished to withdraw the petition, it is clear there were problems at the residence.165 According to an investigation carried out by a Northwest Territories government inspector, staff members felt that the new administrator did not support staff on disciplinary matters, was absent from the residence on too many occasions, and “condoned drinking and other antisocial behaviour among the students.” For his part, the new administrator felt that some staff members expected him “to run the residence like a ‘prison.’” The inspector concluded that there was a “lack of communication and mutual respect amongst the staff.”166

In the late 1980s, Grollier Hall had a student court that imposed penalties such as grounding and chores for violations of school rules.167 As part of the court process, students had to fill out a form explaining what they had done, why they had done it, and what they were going to do about it.168

Gary Black, the assistant superintendent of education for the Northwest Territories, wrote after visiting Lapointe Hall in 1973 that the residence could “at best … be described as tolerable. Only very extensive renovations would make it any more than tolerable.” Black said there were numerous staff problems that he attributed to the authoritarian nature of the residence administrator. According to Black, “People outside the hostel, with some justification, see it as an island surrounded by heavily armed walls. Many integrating activities between hostel and town students which took place in previous years have disappeared.”169

This comparison of the residence to a prison or a fortress was drawn not by a critic of the system but by one of its senior officials. The fact that he placed considerable responsibility for the problems in the residence on the administrator draws attention to the central importance of staffing for the success or failure of the residences. The following year the residence was taken over by the Koe Go Cho Society, a Dene organization in Fort Simpson.170

Supervision

Issues of discipline were complicated by the fact that the hostels were understaffed, supervisory jobs were poorly defined (in fact, often undefined), and hostel employees often had neither the background nor the training needed for the work they were doing. Low wages exacerbated all these problems.

A 1965 review of the hostels in the Northwest Territories identified problems in the staff-to-student ratios. At the Roman Catholic Breynat Hall in Fort Smith, there were seventeen supervisors, responsible for 145 students. There were only three male staff members to supervise sixty-three boys. At Stringer Hall in Inuvik, twenty-three staff members were responsible for 290 students. In September 1965, at the beginning of the Churchill Vocational Centre’s second year of operation, one of the staff members took her concerns over staffing levels to Anglican Bishop Donald Marsh. She wrote, “There are not enough staff members employed so that staff members can have definite time off. Everyone suffers when people are expected to work without a break. Personally, if relief supervision doesn’t appear in the near future, a replacement will be needed for me.”171

A 1965 Indian Affairs report on conditions at Yukon Hall in Whitehorse observed:

There appeared to be only one male and one female supervisor on duty with little attention being given to the organization of any program except the study situation, which was being supervised by Miss Loan. A spirit of friendliness and spontaneity, which is evident among many of our youngsters of high school age, appeared to be totally lacking at the Yukon Hostel.172

Six years later a review of Yukon Hall, which had just been merged with Coudert Hall, identified a number of problems with the child care service at the residence. Because the chief child care worker was also responsible for the direct supervision of a group of students, there was minimal “direct supervision of child care workers.” Nor was there any formal orientation program for new child care workers. As a result, “many child care workers were uncertain as to their exact duties and responsibilities.” The student-to-staff ratio was also very high: in one dormitory building, it was sixty-five to two.173

In January 1976 a father said that he was concerned about the safety of his son, who was living in Fleming Hall at Fort McPherson. L. Donavon said that on a visit to the hostel he saw a locked escape door, garbage piled up in front of the kitchen’s escape door, insufficient water supply, and “children left alone on weekends with no supervisory staff or the staff drunk.”174