Territorial administration: 1969 to 1997

The year 1969 was pivotal for residential schooling in the North. That year saw the closing of one school (Carcross in the Yukon) and one residence (Turquetil Hall in Chesterfield Inlet, Northwest Territories), the transfer of responsibility for First Nations education to the Yukon Territory, and the transfer of management authority for hostels in the Northwest Territories to the territorial government. It also marked the peak of the system of large hostels. In the Northwest Territories, for example, there were nine large hostels in 1969; by the beginning of 1976, only four were in operation: Grollier Hall in Inuvik, Ukkivik in Iqaluit (Frobisher Bay), Akaitcho Hall in Yellowknife, and Lapointe Hall in Fort Simpson.1 In 1969 there were two residences and two residential schools for First Nations students from the Yukon; by 1976 only one was still in operation.

Dismantling the hostel system in the Northwest Territories

In January 1969, the commissioner of the Northwest Territories opened a session of the legislature with the announcement that on April 1, the territorial government was to take over six of the seven large hostels in the North, the one exception being Turquetil Hall. “The Minister recommends that to begin with the Territorial Government should be prepared to operate pupil residences in exactly the same way as they are now being operated, that is, by agreement with the Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches.”2

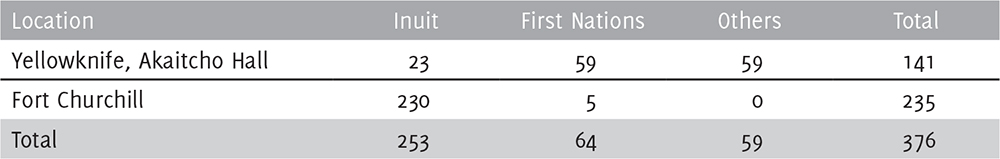

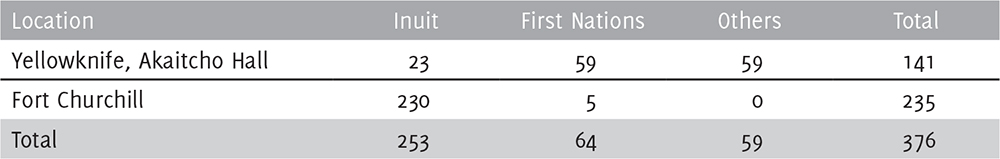

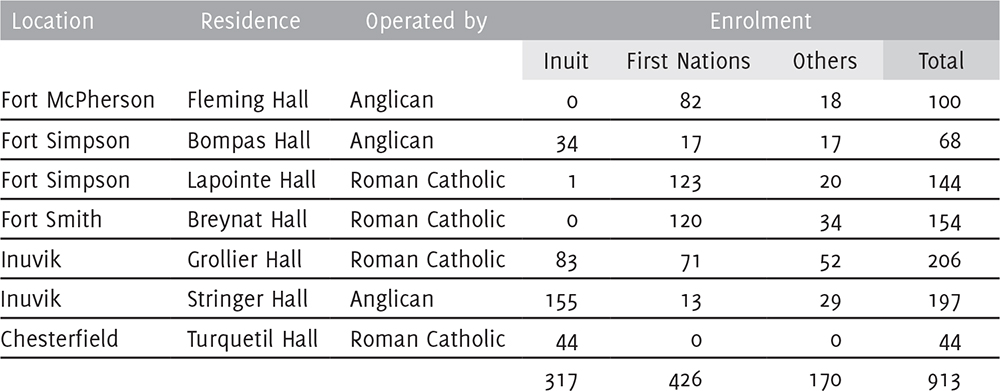

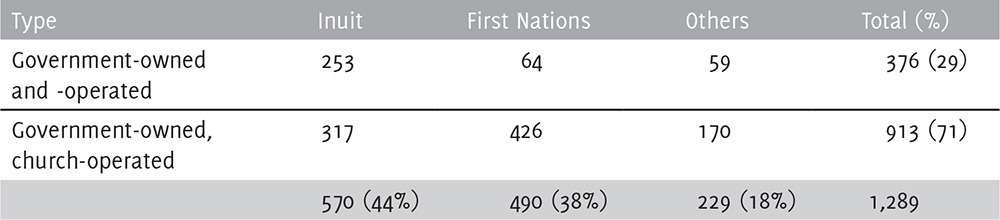

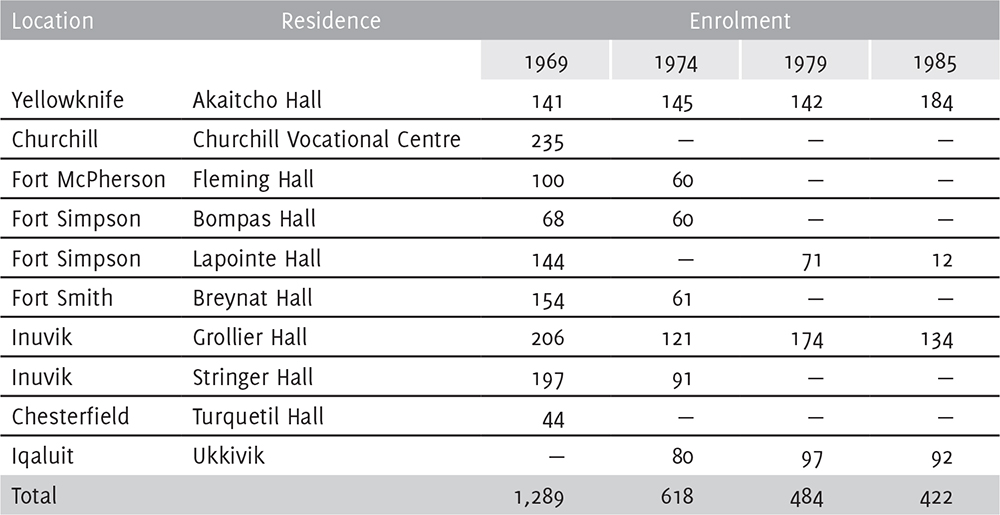

In reality, the churches’ involvement would decline in the coming years. Rather than being transferred to the territorial government, the Roman Catholic Turquetil Hall was simply closed in 1969.3 In total nine residences were transferred. Tables 11.1, 11.2, and 11.3 show that at the time of transfer, the hostels had a total enrolment of 1,289. Forty-four percent of the students were Inuit; thirty-eight percent were First Nations.

Table 11.1Enrolment, government-owned and -operated pupil residences, March 1969

Source: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories Archives, Akaitcho Hall Reports, 1969–1970, Archival box 9-2, Archival Acc. G1995-004. [AHU-003844-0003]

Table 11.2Enrolment in government-owned residences operated under contract

Note: The total enrolment for Stringer Hall is inaccurate in the original source and has been corrected.

Source: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories Archives, Akaitcho Hall Reports, 1969–1970, Archival box 9-2, Archival Acc. G1995-004. [AHU-003844-0003]

Table 11.3Enrolment for government-owned and -operated hostels and government-owned and church-operated hostels, 1969

Source: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories Archives, Akaitcho Hall Reports, 1969–1970, Archival box 9-2, Archival Acc. G1995-004. [AHU-003844-0003]

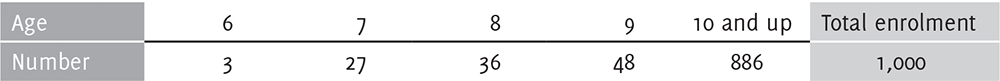

As Tables 11.4, 11.5, and 11.6 show, in the first five years of territorial operation, the number of large residences in the Northwest Territories declined from nine to seven. Their enrolment dropped by over 50%, going from 1,289 students to 618. At the beginning of 1975, the Anglican Church announced that it would not be renewing its contract to operate Stringer Hall in Inuvik for the coming school year.4 The residence closed in June of that year.5 Breynat Hall and Bompas Hall also closed in 1975.6 This trend continued, and in 1985 only four of the large residences remained open (and one of them, Lapointe Hall, had enrolment that was closer to that of a small hostel). Hostel enrolment was only one-third of what it had been at the time of transfer.

Table 11.4.Enrolment in Northwest Territories large hostels, 1969 to 1985

Note: Total enrolment values have been adjusted to correct calculation errors in the original sources.

Sources:1969: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories Archives, Akaitcho Hall Reports, 1969–1970, Archival box 9-2, Archival Acc. G1995-004. [AHU-003844-0003]

1974: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories Archives, Hostel Enrolment, 1974, Archival box 9-11, Archival Acc. G1995-004, “Enrolment by Residences by age, October 1–December 31, 1974.” [RCN-012620-0001]

1979: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories – Education, Culture and Employment, Residences 1979-80 – Quarterly Returns [Akaitcho Hall, Ukkivik, Lapointe Hall, Grollier Hall, Fort Liard, Cambridge Bay], 09/79–06/80, Transfer No. 0349, box 25-4, “Student Residences Quarterly Returns.” [RCN-012634]

1985: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories – Education, Culture and Employment, Student Residence Enrolment and Semi-Annual Attendance 1985–1986 [Grollier Hall], Transfer No. 1201, box 9-1, “Student Residence Quarterly Return,” September 1985; [GHU-000127] “Occupancy Report on Children Placed in Lapointe Hall,” 30 September 1985; [LHU-000600-0000] “Student Residence Enrolment,” Ukkivik Residence, October 1985; [FBS-000065] “Akaitcho Hall, Student Residence Enrolment, 1985–1986.” [AHU-000915]

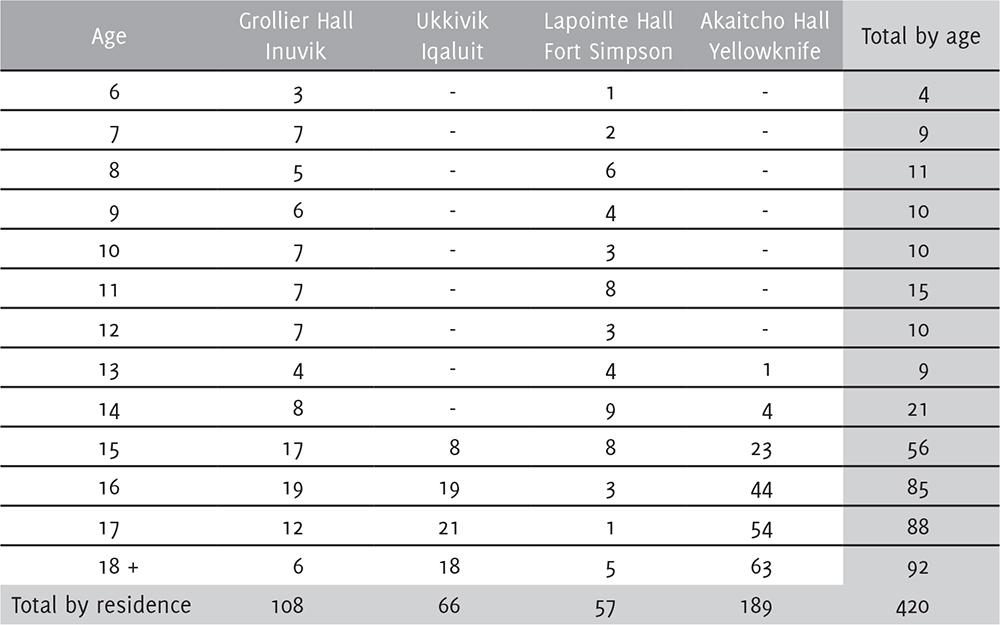

The reduction in the number of hostels and the number of students living in hostels was accompanied by another trend: the aging of residential school students. In 1950 few teenagers attended school outside of Yellowknife and Aklavik, because there were few opportunities in the smaller communities to go even as far as Grade Six. In 1961, 727 pupils were enrolled in schools in what was described as the Arctic District. Of these, 93% were in Grades One to Three. Only two pupils were above Grade Five, and none above Grade Seven. Typically, boys started school around age nine and dropped out at twelve, when they were old enough to make a serious contribution to hunting for the family.7 By 1970, the community day schools were producing students who were ready for high schools and vocational schools, and the growing preponderance of day schools over residential schools meant that the youngest children were being educated closer to home. The territorial government claimed to have reversed the pattern of previous decades, and 10% of students in residences in the Northwest Territories hostels were under the age of ten in 1970.8 By 1977, 63% of the students in the four largest residences in the Northwest Territories were at or above the legal school-leaving age of sixteen.9 (For details see Tables 11.5 and 11.6.)

By the mid-1970s, a substantial number of the students in the hostels who were under the school-leaving age fell into the “social development” category. These were often young people whose parents had been judged unable to care for them, and many were living in hostels in their home communities. In 1975, social development students accounted for 36% of the children in hostels who were ages twelve or under.10 Younger children also came from families who spent much of their time on the land. The most dramatic example of this phenomenon was reported in Fort McPherson in 1972, when there were seventy-two students ages twelve and under at the hostel. All were from the Fort McPherson community.11

Table 11.5Age distribution of pupils in residences, all Northwest Territories, 1970

Source: Director of Education B.C. Gillie, reply given to Legislative Assembly, NWT Hansard (11 February 1971), 503.

Table 11.6.Enrolment in Northwest Territories large hostels by age, June 30, 1977

TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories – Education, Culture and Employment, Residences 1976–77 – Quarterly Returns [Akaitcho Hall, Ukkivik, Lapointe Hall, Grollier Hall, Fort Liard, Chief Jimmy Bruneau], 10/75–07/77, Transfer No. 0349, box 25-1, “Enrolment in Residences by Age,” 30 June 1977. [RCN-012415]

The number of hostels also declined throughout the 1970s. In 1974 the Koe Go Cho Society, a Dene organization, took over operation of the Fort Simpson hostels.12 In 1985 management of the one remaining residence was provided by the Deh Cho Regional Council and the residence became Deh Cho Hall.13 The following year, it provided accommodation for thirty-eight students.14 It closed in 1986, bringing the number of large hostels operating in the Northwest Territories to three.15

Projections in the fall of 1993 showed Akaitcho Hall enrolment declining from 159 in the 1992–93 school year to twelve in the 1995–96 school year.16 In the face of this decline, the territorial government closed Akaitcho Hall at the end of the 1993–94 school year. Students who came to Yellowknife for high school were now boarded in private homes.17

The Roman Catholic Church operated Grollier Hall until 1987.18 The church chose not to renew its contract because it was “running out of religious personnel which would allow us to continue the work.”19 Following the withdrawal of the Roman Catholic Church, the territorial government contracted a local firm, TryAction Management Ltd., to administer Grollier Hall.20 In the spring of 1990, the Department of Education delegated responsibility for Grollier Hall to the Beaufort Delta Divisional Board of Education.21 A 1995 projection for Grollier Hall showed enrolment declining from fifty-one in 1994–95 to thirty-two in 1995–96 and fifteen in 1996–97.22 In the spring of 1996, layoff notices were issued to Ukkivik staff as plans were made to close the facility.23 Grollier Hall was turned over to Aurora College in the summer of 1997.24 With that transfer, the era of the large hostels had come to an end.

Dismantling the hostel system in the Yukon

A process similar to that of the Northwest Territories took place in the Yukon. In 1968, Indian Affairs transferred older students from the Carcross school to Yukon Hall in Whitehorse. According to a policy directive, new enrolment at Carcross was to be kept to a minimum.25 The following year the Carcross school was closed because of decreasing numbers of students and the policy of providing “integrated schooling for Indian children wherever possible.”26 In 1969, Indian Affairs turned the responsibility for the schooling of First Nations students over to the Yukon government. It did, however, retain responsibility for operating the two hostels in Whitehorse and the Lower Post residential school, over the border in British Columbia.27

The Yukon government also moved to reduce the number of residences. In the summer of 1970, Keith Johnson, the administrator of the Anglican Yukon Hall, was made administrator of the Catholic Coudert Hall. Starting that fall, students were assigned to one of the two residences on the basis of age, not religion. The smaller Coudert Hall housed children ages six to twelve, while Yukon Hall housed students thirteen and over. In addition, students from Carmacks, who had in the past been sent over 600 kilometres from home to the Lower Post school, were now to be housed in the Whitehorse hostels, 400 kilometres closer to their home community. In announcing the changes, Yukon Commissioner James Smith said that residential complexes were to be phased out in the coming years.28 By the following year, Coudert Hall and Yukon Hall had been completely amalgamated, leaving the Yukon with only two large residential options: Yukon Hall and Lower Post.29 The expected enrolment for Yukon Hall for the 1970–71 school year was 150 students, with 135 students expected at Lower Post. The Lower Post principal sought to have half a dozen Grades Eight and Nine students transferred to Yukon Hall for “social reasons.” An Indian Affairs official noted that such a move would not be in keeping with the departmental policy of keeping students “in their home community wherever possible.”30 In the face of rising costs and declining enrolment, Lower Post closed at the end of June 1975. It was replaced by three group homes in Yukon communities.31 Yukon Hall would operate until 1985. According to the Indian Affairs annual report for 1984–85:

The Chiefs’ Advisory Board was the forum for Yukon Indian participation in regional policy formulation and decision making. After discussion with Yukon chiefs, the region decided to close the student residence, Yukon Hall, an institution many Indian people felt was detrimental to their education.32

After Yukon Hall closed, a room-and-board subsidy was provided by the Yukon government for students who wished to take grades or courses not available in their home community. Because the subsidy did not cover the total cost of boarding, Indian Affairs provided an additional supplement for First Nations students. As Indian Affairs official B. Zisman observed, “Parents feel the Yukon Government should cover all costs or expand the grades in their community so that students would not have to leave.”33

The dismantling of the system of large hostels in the North after 1969 can be attributed to several factors. Key were government decisions to increase both the number of day schools in First Nations and Inuit communities and the number of grades taught in these schools (a process known as grade extension). Two other factors were the construction of small group homes for students and an increase in the practice of boarding students in private homes. These policy measures were often adopted in response to growing Aboriginal criticism of the residential school system. In the Northwest Territories, this criticism was often voiced by former residential school students who had become members of the legislature.

Aboriginal criticism of the residences

In the late 1960s, two non-Aboriginal legislators raised concerns about the impact of the large hostels. Gordon Gibson, who was appointed to the Northwest Territories Council in 1967, was critical of “the policy of the education department in sending children above grade six level from many small centres to larger communities to continue their education.” An editorial in a Yellowknife paper lauded Gibson’s speech, adding that the hostel system was outdated. “With some 500 teachers in the north, we would say we do have enough teachers for the smaller places and if more are required, then pay them enough money so they will accept the positions in the smaller communities.” Rather than developing the North, the hostel system was, in the editorialist’s opinion, “destroying the smaller communities.”34 R. G. Williamson, another appointed member of the Northwest Territories Council (which has since evolved into the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly), was highly critical of the conditions in the Churchill Vocational Centre. In 1967 he wrote:

Inadequate supervisors have been providing inadequate services. It is an open secret that the youngsters slip out of the Hostel at night with impunity—into a town which is justly notorious as a moral nightmare. The Hostel itself is, by accounts I have received, not a healthy place for young people to spend more than ten months of their lives each year. Potentially good students are not receiving the kind of background they need—and are performing well below their real capacity in some cases. And yet each year, I receive complaints from parents that they have been obliged, against their will, and sometimes with veiled threats to send their children to that institution.35

Northern Affairs officials were beginning to re-examine the department’s policies. A 1967 memorandum reported: “We are now establishing small schools in communities where formerly they would not have been established, for example Repulse Bay, Hall Beach, and Sachs Harbour. We are also examining the feasibility of retaining in certain local schools pupils beyond Grade VI.”36

Momentum for change continued to build in the 1970s. By then, a youthful and talented Aboriginal group of leaders, many of them bilingual, were emerging in the North. They included Piita Irniq, Nick Sibbeston, Tagak Curley, James WahShee, Georges Erasmus, John Amagoalik, Nellie Cournoyea, Richard Nerysoo, Jim Antoine, and Stephen Kakfwi. Most of these leaders had attended either residential schools or schools in southern Canada. This new generation took on leadership roles across the territories, in both Aboriginal rights organizations and territorial government, and several eventually attained the office of premier. They had consistent approaches, based on personal experience, an awareness of Aboriginal rights, and a first-hand understanding of the challenges of schooling in territories where economic development was promised, and where Aboriginal languages, hunting, trapping, and other traditional land-based activities remained important to their collective well-being, and essential to their identities.

As a result, Aboriginal people began to shape the debate over northern education. For example, Alain Maktar from Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) told Northern Affairs officials in Iqaluit in 1968 that “we want the Eskimo’s to be taught in Eskimo” and “we want hunting included in this education as well as home economics.” He argued for employing Elders in the classroom and summed up, “There are about four things we want them to learn, hunting, building igloo’s, in the wintertime and the sewing and the language. If they learn those things they will be able to live in the Arctic.”37

Delegates from several Inuit regions gathered at Kugluktuk (Coppermine) in 1970, to lay the groundwork for the formalization of the national Inuit organization, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (now the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami). The delegates concluded that the present school systems “fail to provide our children with a meaningful education suited to their environment, fail to preserve our native cultures and fail to provide useful Canadian citizens.” They demanded:

•that each community council have a voice in the curriculum content so that native history, culture and skills be included as full credit courses;

•that each community council determine what vacation months during the year will apply to a community. The Southern Canadian standard of July and August is almost universally unsuited to the wishes of Arctic Communities;

•that more schools be provided as rapidly as possible to eliminate the absences from home of ten months per year for our children;

•that instruction in native language dialects in the primary grades be implemented now ... We are decades behind the educational systems of Greenland and Siberia in this regard; that the program to utilize native teachers and teaching aides be greatly expanded immediately.

These points became the standards against which Inuit and other northern peoples would judge their school systems.38

A similar critique emerged from representatives of twelve Yukon First Nations, meeting as the Yukon Native Brotherhood in January 1972.39 The position paper Education for Yukon Indians argued that “our children should be educated in public schools, but ... consideration should be given to the special problems, the preservation of the language, and the factual representation of the culture of a group comprising nearly one-third of the Yukon’s population.” In addition, the chiefs argued that certain vocational and technical courses “must be designed and presented in an Indian setting outside regular educational jurisdiction.”40

In addressing educational policy, Yukon First Nations grappled with the fact that while they were outnumbered in the territory as a whole, they were a majority in many of its smaller communities. Their needs, they believed, were not being met in either context. They proposed that residential schools (which they referred to as the “hated hostel”) be replaced by group homes. These homes would be located “centrally in each village, operated by Indian couples” and would offer short-term accommodation to anyone, especially children and Elders, who needed it to “free parents for the trapline or employment, or to provide warm meals for the young and old who cannot care for themselves.”

In 1977 the Council for Yukon Indians published Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow: A Statement of Grievances and an Approach to Settlement by the Yukon Indian People, which criticized residential schools for their role in undermining intergenerational relations, destroying First Nations spirituality, and producing a dropout rate approaching 100%. No school in the Yukon taught students—white or First Nations—anything about the culture or achievements of First Nations.41

In the Dene Declaration of July 19, 1975, the Dene of the Mackenzie Valley issued their own assertion of Aboriginal rights.42

Aboriginal legislators were also raising the issue. Nick Sibbeston, a Dene from Fort Simpson and a member of the territorial council for Mackenzie-Liard, had been taken to residential school at age four. In speeches in the Northwest Territories legislature in 1971, he called for

•parental involvement in education;

•Dene control of schools and hostels, exemplified in plans for the new school and Dene-run hostel at Edzo (the Chief Jimmy Bruneau School);

•more schooling in communities so that no children need be taken from home before age twelve or thirteen at the earliest; and

•cultural content in curricula.

He was highly critical of an educational system in which children’s “history, language, beliefs, whatever the parents have taught them, are thought to be minor details and excluded in many cases as a nuisance.” He treated residential schools as part of a phenomenon of unemployment, lack of training, and “the anguish in adapting to a different society.”43

In the late 1970s, Stephen Kakfwi, then an official with the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories (later called the Dene Nation), wrote of the way the schools had separated the generations:

The elders had much difficulty in relating to the young. Many of the young lost the language, the values and the views which they had learned from their elders. The elders realized that what was happening to their young in school was not exactly what they wanted. The government was literally stealing young people from their families. They realized that, if the situation remained unchanged, they as a people would be destroyed in a relatively short time.44

Bob Overvold, of the Métis Association of the Northwest Territories (now the Northwest Territories Métis Nation), drew on the eight years he spent in Anglican, Catholic, and government schools to make a similar point:

First, traditionally Dene children learned from their parents. In residential schools the adult-child relationship was almost non-existent; most, if not all the school and residential staff were non-Dene and thus quite alien to the majority of Dene students. Second, because of the style of those institutions, their size, and layout, this meant that many rules and regulations had to be imposed and thus the students were essentially forced to conform.45

The Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry of the mid-1970s provided former students with a forum to discuss their experiences. Justice Thomas Berger’s final report included a brief discussion of the residential schooling system in the North and its adherence to the assimilationist program followed in the South. In testimony at Deline (Fort Franklin), Dolphus Shea told of years of pain and humiliation, concluding, “Today, I think back on the hostel life and I feel ferocious.”46

The Aboriginal critique of boarding schools received a mixed reception from education officials. F. Dunford, the supervising principal of the Churchill Vocational Centre, complained in 1970 about the attitude of an Aboriginal speaker at a conference of northern residence administrators held in Yellowknife. Dunford wrote that the speaker, whom he did not name, “preached the gospel of Indian rights and told us what is wrong with white people.” It was not, he felt, a constructive presentation.47

The campaign of the Inuit of the eastern Arctic to gain control of education from Yellowknife was filled with statements and manifestos that denounced the past system and called for a culturally inclusive, locally based educational system. Early on, the only eastern Arctic member of the legislature was Bryan Pearson of Iqaluit. While not Aboriginal himself, he made sure the legislature was aware of the desire of his Inuit constituents to see classrooms with Inuit teachers in every community and to see hostels become a thing of the past. Landmark events for the Inuit organizations included a four-part series of articles in Inuit Today by Tagak Curley, an early president of the Inuit Tapirisat, titled “Inuit in Our Educational System.” In 1981 the Inuit Cultural Institute at Arviat (Eskimo Point) celebrated the International Year of the Child with an anticolonial review of northern education (Ajurnarmat). In the same year, the English/Inuktitut government periodical Inuktitut published a special issue on Inuit education, with articles on Alaska, Greenland, the Soviet Union, and four projects of current interest in Canada, including Inuktitut teacher-training programs.48

Tagak Curley addressed a meeting of Northwest Territories teachers in 1972:

Most of all, I admire Canadian Inuit for resisting the total assimilation (change) attempted by the dominant Canadian society through their present education policy which you serve. It has been indicated by Inuit that they do not accept this total assimilation which is threatening our values today. It has been said by many Inuit and organizations that there is room in our Canadian society for Inuit to live in harmony (peace) by recognizing their rights through participation. They have the language, they have the traditional economy, and most of all they are the majorities in the settlements in which you will be teaching. We must seriously explore how to modernize those techniques without harming the values they so respect amongst themselves.49

In 1974, when the territorial government sought to rebuild the Iqaluktuuttiaq (Cambridge Bay) hostel, Pearson asked for details, adding: “Whenever I see that term ‘pupil residence’ I see red. Could we have an explanation of why we need a 16-bed pupil residence in Cambridge Bay?” When told that the previous residence had burned down, Pearson responded, “That is good. Who attends it? Why would we have a 16-bed pupil residence in Cambridge Bay?” The explanation was that the hostel was needed for the children of families that were “living off the land, in particular the people in the Bathurst Inlet.”50

As this period drew to an end, Aboriginal political leaders became more explicit in their criticisms of the residential school system. One of the first to speak out in the North was Aivilik mla Piita Irniq. On March 4, 1991, he told the legislature that “too much remains untold by the Government of Canada, and even by the Government of the Northwest Territories. I truly feel that Inuit who were assimilated have a right to know the blunt truth.” He spoke of the “failure of a policy of the government, the result of which is the terrible damage to the preservation of our language, culture, values and the alienation of generations of Inuit peoples of the North.” He called on the territorial government to take up the cause of the residential schools: “I would urge this government not to stall any further to have the Canadian government state their position on the residential school era so that many of us, former students and parents, can begin to deal with the emotional trauma which follows this era. We need to know what the real story is.”51

Grade extension and boarding homes

Criticism by Aboriginal people provided a powerful rationale for dismantling the hostel system. It would take the construction of local day schools offering elementary, and later high school, grades (a process referred to as grade extension) and the adoption of various small-scale board options to finally empty the hostels.

Grade extension

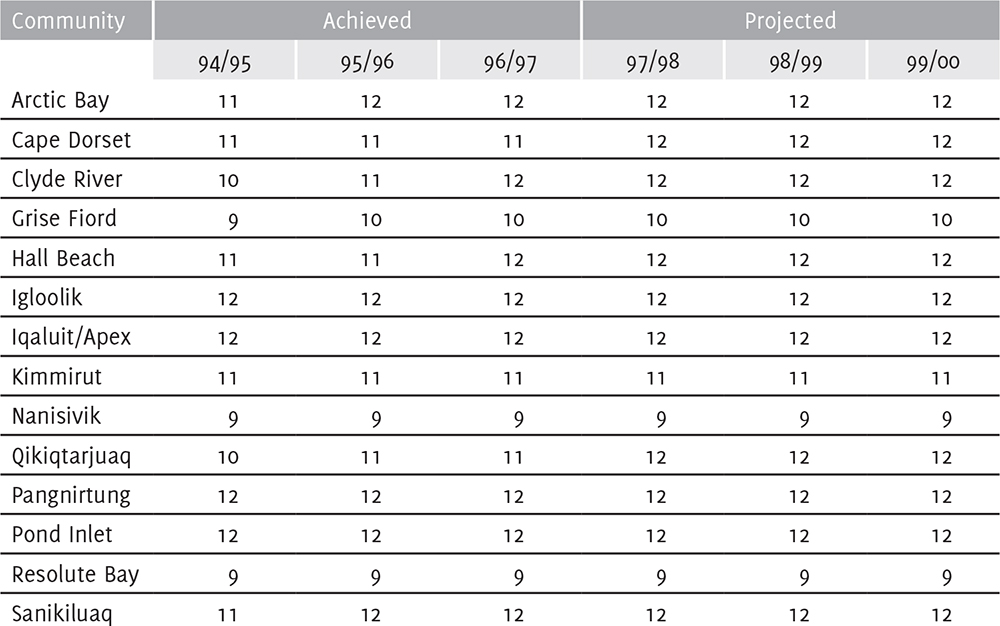

The transfer of authority over education to territorial governments led to a reconsideration of earlier policies regarding whether schools could be located in small communities and which grade levels could be offered in those communities. Initially, educational administrators insisted that grade extension was too expensive.52 A senior educational administrator told a legislative committee in 1971 that for educational reasons he preferred schooling in communities to stop at Grade Six, but strong community pressures had led to a decision to provide up to Grade Eight in many places. It was a trend he expected to continue.53 The following year Northwest Territories Commissioner Stuart Hodgson said, “We are trying to extend the education system in some of the larger communities ... but it is not always possible to extend it as far as what one might like, and therefore residences have to be used.”54 The pressure for grade extension was irresistible. As Table 11.7 shows, by 1995 even the Baffin Division Board of Education was offering Grade Twelve in six of its fourteen communities, with plans to raise that to ten communities within three years.55

Table 11.7Actual and projected grade extension in Baffin Region communities, 1994–95 to 1999–2000

Source: TRC, NRA, Government of Northwest Territories – Education, Culture and Employment, Ukkivik – Future Plans [Capital Planning], 1995, Transfer – Nunavut, box 21, untitled consultant’s report, 2 February 1995, 6. [FBS-000451]

The impact of school construction and grade extension can be observed more closely by looking at the history of the Chief Jimmy Bruneau school and residence. This community-controlled school and residence opened in the new community of Edzo, near Behchoko (Fort Rae), in 1971. It was intended to be a new sort of residence. At the school’s opening ceremony in 1972, Chief Bruneau said, “I have asked for a school to be built on my land and that school will be run by my people and my people will work at that school and children will learn both ways, our way and whiteman’s way.”56

At the start of the 1971–72 school year, the Chief Jimmy Bruneau residence housed thirty-nine pupils.57 By the following year, the figure had risen to ninety-three.58 Due to the construction of day schools in other communities, the number of students in the residence declined to forty-five by the next year, and by the start of the 1974–75 year the residence had ceased to operate.59 The school extended only to Grade Nine. Students who wished to complete further grades usually had to go to Yellowknife; between 1985 and 1990, only six students completed their high school education. To address this problem, the school introduced a Grade Ten program in 1991 (with Grades Eleven and Twelve added in the following years). Ten students graduated in 1994. The following year, the residence reopened, and the school served for a period as a regional high school.60

In the Yukon, a significant argument in favour of grade extension was the high dropout rate of what were described as “rural” students studying at the F. H. Collins High School in Whitehorse. In 1978 they had a dropout rate of 49%; the general Whitehorse dropout rate was 25%.61 Table 11.8 provides an overview of the extension of grades at fifteen schools in the Yukon from 1974 to 1984.

Table 11.8Changes in school grade offerings in the Yukon, 1974 to 1984

| School | Grades offered |

| Pelly Crossing | Fluctuating Grades 7, 6, 8, with Grade 9 after 1980 |

| Old Crow | Grade 8, 9, or 10, with Grade 10 in 1982 and 1983 |

| Burwash | No school until 1980; Grade 7, 8, or 9 thereafter |

| Carmacks | Grade 9 in 1974, Grade 10 thereafter |

| Teslin | Grade 10 most years, Grade 12 1981 to 83 |

| Ross River | Grade 10 throughout |

| Haines Junction | Grade 10 1974 to 1979, Grade 11 in 1980, Grade 12 1981 to 1984 |

| Carcross | Fluctuating Grade 6 to Grade 9 |

| Watson* | Grade 12 throughout |

| Mayo | Grade 12 throughout |

| Dawson | Grade 12 throughout |

| Elsa | Grades 8 or 7, declining to Grade 6 after 1983 |

| Beaver Creek | Grade 7, 8 or 9, especially Grade 9 after 1981 |

| Kluane | Grade 8 throughout, occasionally ending at 7 or 9 |

| Faro | Grade 12 throughout |

* The populations of Watson Lake and Upper Liard, eleven kilometres apart on the Alaska Highway, apparently shared a school and have been combined here.

Source: School data from Sharp, Yukon Rural Education, 52.

Boarding homes and home boarding

Grade extension did not solve the problem of children who wished to finish high school but lived in communities so small and isolated that the higher grades would never be available locally. In the Yukon, the federal government, under pressure from First Nations organizations, adopted a group home policy. At its 1972 and 1973 annual conferences, the Yukon Native Brotherhood had approved resolutions calling on Indian Affairs to replace student residences with group homes.62 Group homes opened in Watson Lake and Ross River in 1975. At Ross River, a married couple were hired to provide care for up to eight children. The couple had to be approved by the Ross River Indian Band before being hired. The hostel was intended to “provide supervision and care in a native community to native children, who would normally be placed in a Student Residence for social or educational reasons.”63

By 1985, there were three group homes, one in Ross River and two in Watson Lake—one of which was slated for closure in that year.64 A 1986 review of the problems facing students from small rural communities called for a new small hostel at Haines Junction. According to the review, some high school students from farther west in Burwash, Destruction Bay, and Beaver Creek had taken their secondary schooling in Haines Junction, and “have remained in school for longer, passed more of their courses, and have encountered less strife” than others who went to high school in Whitehorse.65

The long-term future of schooling outside the home community was specifically addressed in the Umbrella Final Agreement of 1993, which set the framework for settlement of all First Nations land claims in Yukon. The agreement specifically allows as a “permitted activity for Settlement corporations” the granting of “scholarships and reimbursement of other expenses for juvenile and adult Yukon Indian People to enable them to attend conventional educational institutions within and outside the Yukon.”66

Until at least 1980, the Northwest Territories government provided a “private-boarding home allowance” in Yellowknife only for those students who were “handicapped” and therefore could not stay in Akaitcho Hall. A former Akaitcho Hall employee recommended that the boarding option be expanded to include other students. She felt this option would help reduce the institution’s dropout rate.67 Such a program was in operation by 1984.68 The rates for home boarding were increased from $15 a day to $20 a day effective January 1, 1987. Even with the increase, Akaitcho Hall had “difficulty in finding suitable places for students.”69 The government further increased the boarding rates the following year: they ranged from $25 to $40 a day, depending on the region.70

By the mid-1990s the Northwest Territories government was giving thought to making greater use of boarding arrangements.71 A proposal to expand the use of boarding arrangements in Iqaluit identified a number of potential problems. Not only was there a housing shortage, but boarding homes had to be screened to see if they offered students a suitable place to study, sleep, and eat, along with a “caring, firm and supportive environment in which to learn and grow. In spite of screening some homes may not turn out to be suitable.” Furthermore, the boarding home operators “may not themselves have sufficient interest in education to assist the students,” which would force the board to hire tutors. The study noted that “some home-boarded students in the past have not been properly fed. The home boarding parents have spent the money on other things. At times, the students have been used as babysitters for the family at the expense of their studies.”72 The review concluded that home boarding should be considered only “on an exception basis,” when students’ parents and the board both agreed.73 A committee reviewing the future of Akaitcho Hall in 1992 came to similar conclusions, noting cautiously that “home boarding of students can work well if a careful selection of home boarding parents is assured.” And this long-term solution was offered: “If student residences are needed, they should be small (15–20 students) and contracted out to a good family who will live in the residences.”74

Northern education in southern Canada

The policy of sending a limited number of Aboriginal students south to continue their education continued after responsibility for education was transferred to the territories. According to former Northern Affairs official Ralph Ritcey, from 1967 to 1978, the program sent between thirty and forty students a year to Winnipeg and a hundred a year to Ottawa.75 Students from the western Arctic tended to go to Edmonton, while students from the eastern Arctic typically found themselves in Ottawa or Montreal. Federal involvement was significant, and was delivered in its later years through a Vocational Training Section in Northern Affairs. In 1980 about sixty-five Inuit went south through this program, but only sixteen of those went to high schools; the rest were in vocational programs, with a few in academic upgrading.76

These students often boarded with non-Aboriginal families. In 1983 Tagak Curley questioned the government’s policy of having Inuit children board with families in southern Canada. As an alternative, Curley called on the government to establish an “Inuit House” in Ottawa.77 Northern leaders were always alert to the distress and hardship their young people felt, and Inuit-language magazines in particular published special issues, with articles written by young students, to try to prepare their fellow Inuit for the culture shocks ahead.78 By 1983, the territorial government’s official position was that it would not send high school students south.79