At this point, and I cannot believe I am about to do this, I would like to address the Internet commenters out there directly. Good evening, monsters. This may be the moment you’ve spent your whole lives training for…for once in your life, we need you to channel that anger, that badly spelled bile that you normally reserve for unforgivable attacks on actresses you seem to think have put on weight, or politicians that you disagree with. We need you to get out there and, for once in your life, focus your indiscriminate rage in a useful direction. Seize your moment, my lovely trolls, turn on caps lock, and fly my pretties! Fly! Fly!

—JOHN OLIVER, LAST WEEK TONIGHT, JUNE 1, 2014

IN 2014, THE Federal Communications Commission opened public comments on the issue of “net neutrality,” which prevented Internet service providers like Comcast from prioritizing certain types of web content over others. In an attempt to draw attention to the issue, comedian John Oliver spent thirteen minutes of his HBO show Last Week Tonight explaining net neutrality and encouraging his viewers to leave public comments for the government agency. In the subsequent days, the FCC received more than 45,000 new comments on net neutrality, and the online system experienced technical difficulties as a result of heavy traffic (McDonald 2014). As the net neutrality debate heated up again in May 2017, Oliver again argued against a plan to roll back net neutrality measures, and again the FCC received an influx of public comments—150,000 in a few days, or five times as many as it had received in the thirty days before Oliver’s plea (Breland 2017).

On its face, Oliver’s war with the FCC over net neutrality seems to be a story about the ways in which political behavior can be influenced by celebrities and tastemakers. Implicit in Oliver’s call to action, as highlighted in the epigraph to this chapter, are questions about the connection between political incivility and participation. His expectation is that if enough people “focus [their] indiscriminate rage in a useful direction,” the FCC will change its position on net neutrality. Citizens’ participation in political discourse, specifically uncivil political discourse, will lead to their preferred policy outcome.

The deliberative democrat is swift to counter Oliver’s expectation: incivility diminishes our respect for one another and our political institutions, thereby making political discussion and compromise difficult (Ferree et al. 2002; Gastil 2008; Gutmann and Thompson 1996). Theorists who emphasize the importance of participation to the democratic polity take a rosier view, pointing to the relationship between incivility and political participation. As Almond and Verba argue in The Civic Culture (1963), the most stable political systems are those that have relatively high levels of both tolerance and participation, blending the priorities of the two theoretical camps. In their ideal “mixed” society, the amount of engagement is important—democratic republicanism requires that citizens make their preferences known to elected officials through voting, protests, letters, etc.—but so is the quality of that engagement. However, my investigation into the role that conflict orientation plays in shaping political behavior suggests that these two approaches are not blending as well as we might hope. The conflict-approaching are more likely to participate in a range of political activities, and their commentary on political news mimics what they see in the media. If individuals are exposed to incivility, they will be more likely to use it in their own political conversations.

These patterns suggest that if the contemporary political environment truly is riddled with greater incivility, conflict orientation becomes a resource citizens must use to successfully navigate their political world. Those who are conflict-approaching have greater capital when entering the political arena, ultimately making them more likely to participate in political activities that demand an ability to handle disagreement and incivility. In this chapter, I test the participation-quality and participation-quantity hypotheses by investigating this relationship between incivility, conflict orientation, and participation. First, I examine the correlation between conflict orientation and different forms of political participation. When a political activity opens individuals up to incivility and conflict, the conflict-approaching are more likely to engage than the conflict-avoidant. Then, focusing on political discussion, I explore how the presence of incivility changes both the likelihood of engaging in online political discussion and the content of that discussion. Across three studies, the results indicate that a more uncivil political landscape not only leads certain types of people to participate more than others, but also changes the way in which they participate, further raising the barrier to entry and reinforcing preexisting inequalities in engagement.

SHAPING POLITICAL ACTIVITY

Year after year, survey respondents report voting in recent elections at high rates, but demonstrate much lower engagement with other forms of political participation such as protest, campaign work, contacting elected officials, or engaging in interpersonal political discussion. In their quest to explain this variation across political activities, as well as why citizens participate in politics more broadly, Brady, Verba and Schlozman (1995) shift the question, asking why people do not take part in politics. They write:

Three answers immediately suggest themselves: because they can’t, because they don’t want to, or because nobody asked. “They can’t” suggests a paucity of necessary resources…. “They don’t want to” focuses on the absence of psychological engagement with politics—a lack of interest in politics, minimal concern with public issues, a sense that activity makes no difference…. “Nobody asked” implies isolation from the recruitment networks through which citizens are mobilized to politics. (271)

They go on to demonstrate that three political resources—civic skills, money, and free time—shape individuals’ likelihood of participating in different political activities and that these resources, in turn, are linked to demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of individuals. At first glance, conflict orientation does not seem to have much in common with these resources. I have been making the case throughout this book that it is a psychological trait, but it does not quite fall into the category of Brady, Verba and Schlozman’s second explanation, psychological engagement. Conflict orientation is distinct from efficacy or political interest. Individuals may want to participate in politics but feel they cannot because they do not have the tolerance for disagreement, negativity, or vitriol that they perceive is needed to engage. From this perspective, conflict orientation is a resource, just like money or civic skills.

This resource helps citizens navigate some political activities better than others. Research on political behavior tends to focus on a standard set of political activities; since the 1950s, the American National Election Study has asked citizens if they voted, attended political meetings, rallies, or speeches, wore a campaign button or put a sign in front of their house, or talked to anyone to show them why they should vote. More recently, they have included questions about donations to political causes and online discussion of political issues. As Ulbig and Funk (1999) explain, certain participatory acts are more likely to expose an individual to conflict. Specifically, activities that require public expression of one’s beliefs are more likely to elicit interpersonal disagreement (Verba and Nie 1972; Milbrath 1965), as are those that provide more opportunity for far-reaching change (Verba and Nie 1972). Given these two dimensions, they argue that protest represents a high-conflict political activity, campaign support and discussion of politics reflect a medium likelihood of exposure to conflict, and voting and contacting officials are low-conflict activities (Ulbig and Funk 1999).

Following Ulbig and Funk, I categorize different types of political engagement into high-conflict, midrange, and low-conflict activities (see table 5.1). In many cases, my classification mirrors theirs; however, in addition to looking at protest, voting, and contacting officials, I break political discussion into two separate acts: commenting on political blogs and persuading others to vote. I also differentiate between types of campaign work: donating money, wearing a campaign button, putting up a political sign, working for a candidate, and attending a local meeting.

TABLE 5.1 CATEGORIZATION OF POLITICAL ACTIVITIES BY EXPOSURE TO CONFLICT

| HIGH-CONFLICT |

MIDRANGE |

LOW-CONFLICT |

| Commenting on political blogs |

Contacting government officials |

Donating money |

| Persuading others to vote |

Wearing a campaign button |

Voting |

| Attending a political protest |

Putting up a political sign |

|

| Attending a local meeting |

Working for a candidate |

|

The assessment of conflict in political activities is in part a function of the public or private nature of the participation. Donating money and voting are the sole low-conflict activities because they are the only means of engaging in politics privately, without interacting with another person. Unless you tell friends and family how you voted or that you donated money, these decisions remain relatively anonymous and are unlikely to provoke conflict. Most of the campaign activities are classified as midrange; one’s opinion is no longer anonymous and is publicly exposed, but not necessarily in a venue that invites discussion or uncivil reactions. For example, if you put a political sign in your front yard, your neighbors will all know for whom you voted, but unless they happen to be walking their dog while you are out mowing the lawn, you are unlikely to experience interpersonal conflict as a direct effect of the yard sign. Similarly, if you work for a candidate, whether by going door to door, phone-banking, or participating in other Get Out the Vote efforts, you are likely calling undecided voters or the candidate’s base—individuals who are less likely to challenge your support for that candidate. High-conflict activities are those in which one has the opportunity to voice one’s own opinion and where others can respond. These can be situations in which individuals are or are not anonymous, but where they are likely to receive pushback on their views. Protests are designed to instigate conflict between opposing sides. Even if the majority of protestors are in agreement about an issue, an individual in attendance is more likely to hear disagreement, frequently expressed through name-calling or other forms of incivility. Similarly, participating in the comments section of a blog or news article or persuading others to vote signals a clear intention to discuss political opinions with others who might disagree and opens one up to challenges and offensive statements.

To summarize, people’s conflict orientation will affect their decision to participate in political activities where they are more likely to be exposed to conflict. Here, conflict does not mean just incivility, but incorporates a wider definition that captures disagreement as well as incivility. When presented with an uncivil political environment, individuals who enjoy conflict will engage. Conversely, more conflict-avoidant individuals possess less of this resource in the political realm. They shy away from activities that could force them to experience incivility and disagreement. The conflict-avoidant take steps to reduce their exposure to conflict, while the conflict-approaching hunt for it.

Participation-quantity hypothesis: The conflict-approaching will be more likely to participate in high-conflict activities, but there will be no difference in participation in low-conflict activities across conflict orientations.

As the high-conflict participatory acts center around public expression of one’s opinion, it seems important to further investigate the role of incivility in this domain, disentangling it from disagreement. Many scholars in the realm of political psychology and communication have found that individuals are intimidated by the prospect of engaging in public political conversation. Hayes, Scheufele, and Huge (2006) argue that political engagement, including discussing our own opinions, risks upsetting delicate interpersonal relationships. The fear of upsetting or excluding others is why etiquette experts recommend avoiding political conversation; Anna Post of the Emily Post Institute emphasizes respect and the use of civil language as means of keeping the peace (Grinberg 2011). Participants in Conover, Searing, and Crewe’s (2002) focus groups reported fears of looking uneducated, facing social rejection or isolation, and encouraging social conflict when faced with the prospect of political conversation. Those who do enjoy political discussion tend to share particular personality traits (Gerber et al. 2012; Testa, Hibbing, and Ritchie 2014) or seek out discussion forums that provide connections to like-minded others in an “imagined community” (Berry and Sobeiraj 2014). Experiencing both enjoyment and displeasure while having a political conversation depends on the characteristics of the environment and the individual.

Increasingly, Americans report that they are talking about politics not only with their friends and family in face-to-face discussion, but with a wider network of acquaintances and strangers on the Internet. According to a Pew report on the political environment on social media, approximately one-third of American adults use social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter to engage in political conversations (Duggan and Smith 2016). Furthermore, the Internet serves as a venue for citizens to directly engage with their elected officials and political candidates. All serious presidential candidates (and the vast majority of congressional candidates and candidates for state offices like governor) have Facebook accounts and Twitter pages. A focus on the qualitative and quantitative effects of online incivility is particularly warranted as the Internet becomes an increasingly important space for citizen-to-citizen and citizen-to-leader communication about politics.

In general, incivility influences individuals’ willingness to engage in political conversation, but this is particularly true online. According to Duggan and Smith (2016), 40 percent of those who engage in political conversations on social media agree strongly with the statement that “social media are places where people say things while discussing politics that they would never say in person (an additional 44 percent feel that this statement describes social media somewhat well).” Attributes of online comment sections, discussion forums, and social networking sites, such as anonymity and a sense of disinhibition, facilitate the use of incivility (Santana 2014; Suler 2004). The presence of incivility, in turn, has mixed effects on users’ participation in online commentary or deliberation. In one study, people who were exposed to civil discussion reported greater willingness to participate in political discussion than those exposed to uncivil discussion (Han and Brazeal 2015). People exposed to online incivility are also less likely to believe that deliberation in public discourse can resolve political problems (Hwang, Kim, and Huh 2014). Other studies have found that uncivil discussion does not affect respondents’ intent to participate in discussion; if anything, it increases participatory intent (Borah 2014; Ng and Detenber 2006). One possible explanation for these divergent findings stems from the role of conflict orientation. Per the participation-quantity hypothesis, the conflict-avoidant are less likely to comment on a blog post, protest, or engage in political discussion because those types of activities invite conflict. When they are confronted by incivility, then, they will also be less likely to participate.

Political-discussion hypothesis: When the conflict-avoidant are faced with incivility, they will be less likely to participate in online discussion. When the conflict-approaching are faced with incivility, they will be more likely to participate.

SHAPING THE QUALITY OF POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT

Scholars concerned about the effects of incivility on discussion are worried not only that incivility reduces individuals’ willingness to talk about politics, but also that incivility changes the quality of the conversation. As discussed in chapter 4, a wealth of research suggests that incivility is particularly present in online political discourse, as attributes of the platform facilitate its use. Anonymity, reduced self-regulation, and reduced self-awareness lead to depersonalized messages that in turn encourage more assertive and uninhibited responses (Kiesler, Siegel, and McGuire 1984; Anderson et al. 2014). In other words, the normative expectations about nonverbal behavior and respectful tone that hold for face-to-face communication break down online, reducing the quality of political discussion.

Furthermore, incivility begets incivility in political conversation because humans learn appropriate behavior by observing their surroundings. Drawing on both cognitive and behavioral strands of psychological research, Bandura (1977, 2002) argues that we watch others’ interactions with their environments and, based on the positive or negative outcomes of those interactions, adapt our own behavior. This sort of modeling behavior is evident in investigations into the effects of incivility on group dynamics and political conversation, particularly conversation occurring on the Internet. In real-time online discussions, individuals mimic the overall tone of the group; a negative overall tenor to a conversation will lead certain people to use negative language in their own comments (Price, Nir, and Cappella 2006). Similarly, Gervais (2011, 2015) has found that incivility both on television talk shows and in online discussion forums leads viewers or participants to be more uncivil in their own comments and discussion of issues. Taking a more positive approach, Han and Brazeal (2015) found that people exposed to civil discussion demonstrate more civil discourse in their own comments. Applying social-learning theory to an online environment rife with incivility, it seems probable that those who are more likely to comment online—the conflict-approaching—will also be more likely to use incivility in their comments.

Participation-quality hypothesis: Conflict-approaching individuals who are exposed to incivility will be more likely to use incivility in their own online comments.

MAKING DECISIONS: CHOOSING POLITICAL ACTIVITIES

Participants in three of the studies describe in chapter 1 were asked to report whether they had engaged in a range of political activities in the past year and whether they had voted in the last presidential election.1 Activities in which participants could report participating included attending local political meetings (such as school board or city council); going to a political speech, march, rally, or demonstration; trying to persuade someone to vote; putting up a political sign (such as a lawn sign or bumper sticker); working for a candidate or campaign; wearing a campaign button or sticker; phoning, emailing, writing to, or visiting a government official to express their views on a public issue; commenting on political blogs or online forums (not surveys); and donating money to a candidate, campaign, or political organization. As discussed earlier and displayed in table 5.1, I categorize each of these activities as high-conflict, midrange, or low-conflict based on the likelihood that individuals participating in each will encounter disagreement or incivility and have to respond or defend their own viewpoint.

As is frequently the case with political participation, the vast majority of participants reported having voted in the previous election (approximately 71 percent of Project Implicit participants and almost 88 percent of Mechanical Turk participants), but far fewer people reported engagement in more resource-intensive activities like attending a meeting or working for a candidate. As table 5.2 shows, commenting on blogs, contacting government officials, and persuading others to vote are the most popular forms of more active engagement; between 19 and 38 percent of participants reported engaging in these activities in the past year. These high-conflict activities are also potentially the most interesting for an investigation into the effects of conflict orientation, as they all require interpersonal communication. Engagement in other participatory activities, most of which require an investment of time or money, hovers at 15 percent or lower. Working for a candidate is the least frequent form of political engagement, with less than 5 percent participation across both samples, but is also arguably the most time- and knowledge-intensive activity.

TABLE 5.2 POLITICAL PARTICIPATION ACROSS SAMPLES

| |

|

PERCENTAGE PARTICIPATING IN THE PAST YEAR (PROJECT IMPLICIT) |

PERCENTAGE PARTICIPATING IN THE PAST YEAR (MTURK STUDY 1) |

| High-conflict |

Commented on political blogs |

18.6 |

28.1 |

| |

Persuaded others to vote |

27.7 |

38.0 |

| |

Contacted government official |

22.2 |

19.3 |

| |

Attended political protest |

13.5 |

9.5 |

| Midrange |

Attended local meeting |

13.4 |

9.0 |

| |

Wore a campaign button |

12.1 |

13.2 |

| |

Put up political sign |

11.3 |

13.1 |

| |

Worked for a candidate |

4.8 |

4.6 |

| Low-conflict |

Donated money |

13.2 |

11.5 |

| |

Voted |

70.8 |

87.7 |

RESULTS: POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

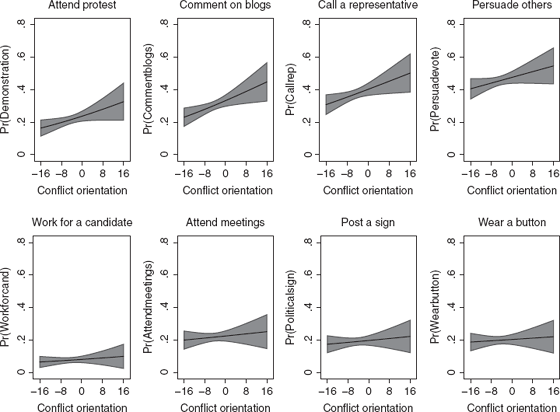

The participation-quantity hypothesis asserts that citizens make decisions about political participation on the basis of the potential for exposure to incivility. If they enjoy conflict, they will be more likely to participate in high-conflict and midrange political activities than those who have an aversion to conflict. The data provide evidence of conflict orientation’s ability to shape participation in different political activities, particularly activities that present the possibility of uncivil or confrontational discussion.

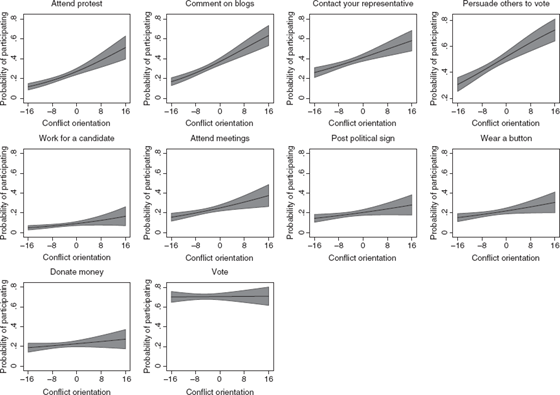

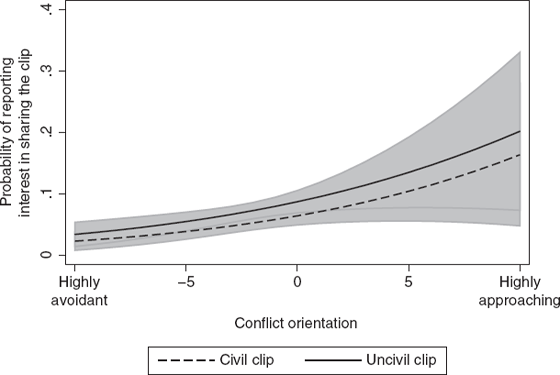

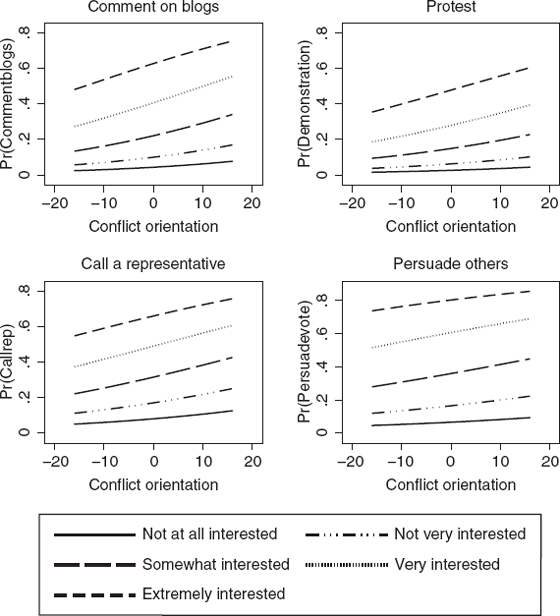

FIGURE 5.1 Bivariate analyses suggest conflict-approaching individuals are more likely to participate in political activities.

Note: Probabilities are reported from bivariate logistic regressions of each participatory activity on conflict orientation. Lower values on the conflict orientation scale represent more conflict avoidance; higher numbers equal more conflict approaching tendencies. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Project Implicit.

Figure 5.1 displays the bivariate relationships between participatory acts and conflict orientation in the Project Implicit sample.2 From these graphs, it is clear that more conflict-approaching individuals are more likely to participate in most political activities. The one exception to this pattern is the likelihood of voting, which is uniform across conflict orientation; regardless of conflict orientation, there was about a 70 percent chance that a participant reported voting in the last presidential election. Beyond voting, the relationship between conflict orientation and participation is statistically significant and positive, although the size of this effect varies from activity to activity. In line with my hypothesis, the effects of conflict orientation are larger for the activities categorized as high-conflict. The likelihood of attending a protest, contacting one’s representative, persuading others to vote, and commenting on blogs shifts significantly from the most conflict-avoidant (20 to 30 percent chance of reporting participation in the past year) to the most conflict-approaching (50 to 75 percent probability). The midrange or low-conflict activities exhibit, at most, a 30 percent change from one extreme of the Conflict Communication Scale to the other. Conflict-avoidant individuals report a 5 to 20 percent likelihood of engaging in politics by working for a candidate, attending a meeting, posting a political sign, or wearing a button, while their conflict-approaching peers report a 15 to 35 percent probability of engaging in these activities.

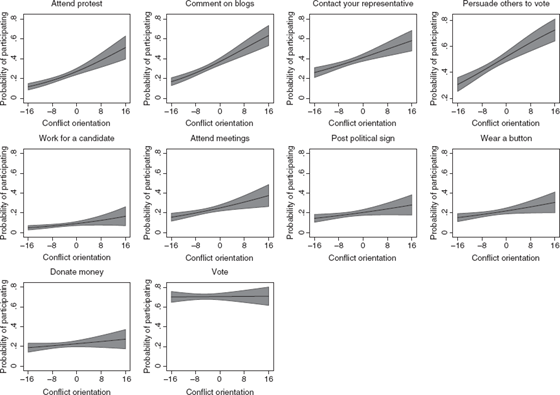

As with the investigation into patterns of media consumption, this analysis incorporated other participant characteristics that are known to influence political participation. Once I factor in the effects of these demographic and political variables on an individual’s participation, the story of conflict orientation’s role in participation is slightly different. As figure 5.2 shows, conflict orientation still plays a statistically significant role in citizens’ reporting that they had attended a protest, contacted their representative, commented on blogs, or persuaded others to vote: conflict-approaching participants are more likely than those who are conflict-avoidant to participate in each of these activities. However, conflict-approaching individuals are no more likely to participate in the midrange or low-conflict activities—working for a candidate, attending a meeting, posting a sign, or wearing a button—than the conflict-avoidant participants.

FIGURE 5.2 Controlling for other characteristics, conflict-approaching more likely to participate in high-conflict activities.

Note: Probabilities are reported from multivariate logistic regressions of conflict orientation, controlling for personality, gender, age, education, race, ethnicity, party identification, party strength, and political interest. Lower values on the conflict orientation scale represent more conflict avoidance; higher numbers equal more conflict approaching tendencies.

Source: Project Implicit.

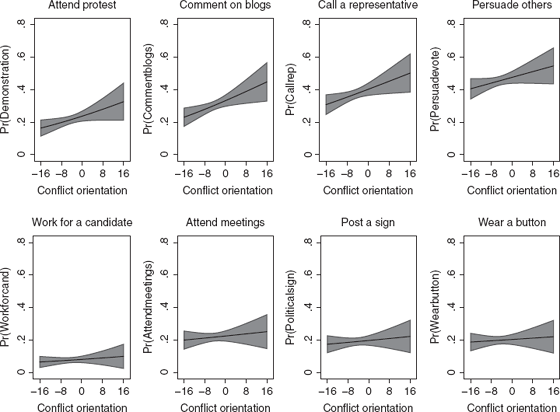

These differences in likelihood of participation are more pronounced for those who are more interested in politics.3 Looking exclusively at the four forms of participation that are statistically significant when controlling for demographic and political characteristics (commenting on blogs, protesting, calling a representative, and persuading others), it is clear that political interest plays a major role in getting people to engage in these activities (figure 5.3). Being conflict-approaching further increases the proclivity to participate if an individual is already interested in politics. Survey respondents who reported that they were not at all interested in politics show minimal change in their probability of participating across the CCS. The slope of each predicted probability line increases with the increase in political interest; very and extremely interested participants who are conflict-avoidant are about 20 percent less likely to participate in any activity than those who are somewhat interested or less so.

FIGURE 5.3 Effects of conflict orientation at different levels of political interest.

Note: Figures represent linear predictions from a multivariate regression that includes an interaction between interest and conflict orientation.

Source: Project Implicit.

To summarize, the participatory findings presented here demonstrate that there is a direct relationship between political engagement and conflict orientation. Conflict-approaching individuals are more likely to report having participated in high-conflict activities—that is, activities in which they are more likely to be exposed to disagreement or incivility—than their conflict-avoidant peers. This is particularly true for people who are also interested in politics. The effect of conflict orientation is stronger for the extremely interested than it is for those who are not at all interested. One’s predisposition toward conflict does not appear to play a part in the decision to engage in the midlevel to low-conflict forms of political participation. For these activities—wearing a button, working for a candidate, donating money, and perhaps most important, voting—the conflict-avoidant are just as likely to participate as the conflict-approaching.

Over each set of results, there is a consistent finding: the conflict-approaching are more likely to participate in three of the high-conflict activities: protest, commenting on a blog, and persuading others. However, these results are purely observational. It is impossible to tell whether it is the conflict inherent in these activities or something else that is driving the decision to participate. The GfK experiment offers some insight into the causal role that incivility plays in leading individuals to comment on or share civil and uncivil video clips.

As discussed in chapter 3, participants in the GfK study were shown one of four video clips that varied on two dimensions: politics/entertainment and civil/uncivil. The entertainment clips were edited from an episode of Master Chef; the political clips were from CSPAN coverage of a congressional hearing concerning Planned Parenthood. After watching their assigned video, respondents were given the opportunity to comment on the clip and were asked whether they would share the story with friends on social media, and if so, what their own commentary on the piece would be. In response, 63 percent of respondents commented on the clip they had watched, with a high of 68.6 percent for those who had watched the civil Planned Parenthood clip and the lowest frequency of comments from those who had watched the civil Master Chef clip. Only 6 percent of the total sample reported interest in sharing the story, with a similar distribution across the four videos, varying from 4.8 percent (the civil Master Chef clip) to 7.6 percent (the civil Planned Parenthood clip).

While it is important to acknowledge that there are distinctions across the four treatments, the primary question is whether incivility—manifested in political or entertainment discourse—affects the likelihood of participating in conversation about the issues presented. Therefore, I collapsed the treatments along the civility/incivility dimension to explore whether the tone of the clip affected individuals’ likelihood of commenting on or sharing the clip. A two-sample test of proportions suggests that there is no difference between individuals’ likelihood of commenting on the civil and uncivil video clips (civil = 62.2 percent, uncivil= 64.0 percent, one-tailed p = 0.16). However, there is a difference in the proportion of individuals who were willing to share the story with their friends on social media.4 Whereas 7.4 percent of people reported an interest in sharing the uncivil clips, only 5.2 percent of those who saw a civil clip were interested in sharing the story (one-tailed, p = 0.006). In other words, participants were no more likely to comment on a clip that was uncivil, but they were more likely to (hypothetically) share that uncivil clip with their social networks.

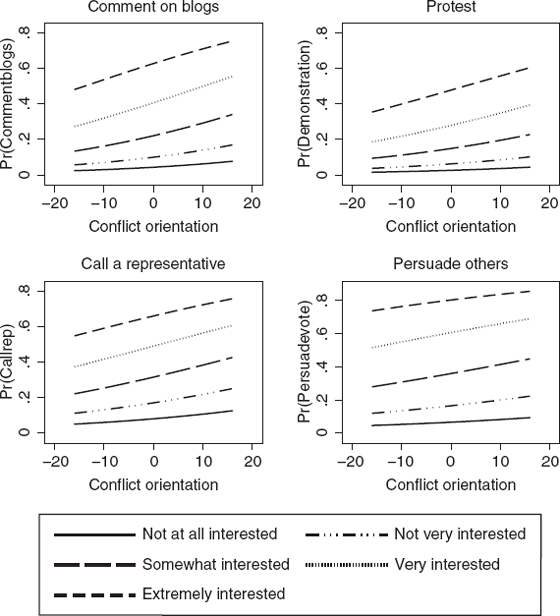

Finally, we can investigate the role that conflict orientation plays in moderating the effects of incivility on commenting on or sharing these video clips. The political-discussion hypothesis suggests that the conflict-approaching will be more likely to engage when a story is uncivil, while the conflict-avoidant will be less likely to comment on or share the same story. Results from a logistic regression suggest that both incivility and conflict orientation do shape the likelihood of sharing a story, but not in the interactive way I predicted (see appendix B for full regression results). Instead, people across all conflict orientations are more likely to share the uncivil story than the civil story. At the same time, conflict-approaching respondents also reported being more likely to share than their conflict-avoidant counterparts. This relationship is depicted graphically in figure 5.4.

FIGURE 5.4 Conflict-approaching more likely to share incivility.

Source: GfK.

As you can see from the graph, the highly avoidant are very unlikely to express interest in sharing any video clips, regardless of whether they are civil or uncivil. The most conflict-avoidant people have a 2 percent probability of sharing the civil clip and a 3 percent probability of sharing the uncivil clip. On the opposite side of the graph, we can see both that the gap has widened slightly between the likelihood of sharing the civil and uncivil clips (although this is clearly not statistically significant) and that the most conflict-approaching respondents are more willing to consider sharing. The highly conflict-approaching have a 16 percent likelihood of sharing a civil clip and a 20 percent likelihood of reporting interest in sharing the uncivil clip.

While these results do not depict a clear interactive effect, they nevertheless demonstrate the importance of considering incivility and conflict orientation simultaneously. The conflict-approaching are the ones doing the sharing on social media, and they are sharing civil and uncivil video clips at roughly equivalent rates. However, if the conflict-approaching are more frequent posters of content, we also have to consider how their reactions to that content might shape the quality of conversation.

MAKING BETTER CONVERSATION?

From a normative perspective, it matters little that conflict-approaching individuals are more likely to participate in high-conflict activities if their participation is reinforcing the link between political expression and uncivil discourse. Citizens might be participating, but they are participating in a manner that is detrimental to political discourse premised on mutual respect and focused on bridging lines of difference. Therefore, we must not only investigate whether the conflict-approaching are participating in politics, and specifically political conversation, more than their conflict-avoidant peers, but also assess the quality of that participation. Are those who choose to comment on political news doing so in a civil manner?

Participants in the GfK study were asked to offer comments or ask questions about the video they had watched as if they were making a comment on YouTube or a similar social media site. In response, 63 percent of participants wrote something in the comment box, although 15.5 percent of those explicitly stated that they had “no comment,” included gibberish (“fffffff”), or expressed confusion about what they were being asked to do (“I do not understand”). Still, 54 percent of the comments fell into at least one of the other four categories used in the coding scheme; they engaged in metacommunication around the televised conversation, used incivility in their response, offered an opinion about the issues discussed, or asked questions about the content.

The two most prevalent types of responses were those that offered an opinion about the content and those that commented on the tenor of the conversation in the clip (see table 5.3). Over 24 percent of those who made comments engaged in a form of metacommunication, calling attention to the manner in which the interaction in the video took place rather than to the content of the exchange. Many of these comments focused on the specific exchange the participant had just viewed, as in this comment about the back-and-forth between Jim Jordan and Cecile Richards:

Rep. Jim Jordan interrupts way too often and does not allow the other party to speak a full thought or comment. It sounded more like one party (Jim) shutting down another party (Cecile) versus really trying to hear or understand that other party’s comment. It was not a civil disagreement or argument, instead it was an aggressive, emotional shut-down, which I found to be inappropriate and unprofessional. (participant 759)

Another participant also called Jordan out for his tone and behavior, stating, “The jerk Ohio representative is obviously on a witch hunt. He is hitting the PP president with constant argumentative comments and expecting her to answer…this is an obvious one-sided questioning which the representative wants to make sure comes out his way” (participant 3667). Each of these participants felt that Jordan was bullying Richards rather than engaging in an open conversation about the allegations levied at Planned Parenthood.

TABLE 5.3 FREQUENCY OF CERTAIN TYPES OF COMMENTS

| |

PERCENT OF COMMENTS |

| No comment/gibberish |

8.1 |

| Confusion about task |

7.5 |

| Metacommunication |

24.4 |

| Offers opinion |

21.9 |

| Wants to learn more |

5.6 |

| Uses incivility |

9.1 |

Other comments drew on the tenor of the media clip to make a generalization about the negative tone of political conversation or reality television. One participant noted, “This is the problem with our nation we can not be civil at anything even cooking” (participant 1432). This dismay at the lack of civility in reality-television programming was echoed by another participant, who thought the judge could have been less critical of the dish he tasted: “My general comment about reality shows is that in general I really…dislike them because I think they encourage rudeness, confrontation, major self-promoting, and a loss of civility” (participant 1227). In the political realm, participants who watched the uncivil exchange between Jim Jordan and Cecile Richards saw it as typical of contemporary political discourse. “It seems like all politics is anymore is people arguing,” wrote one participant (1056). Another added, “As usual, congress people are discourtious, impolite…if I were the congressmans constittuant [sic], I may choose to not vote for him” (participant 2117). Many viewers perceived the actions and tones used as emblematic of a larger group, and for some, that tone shaped their hypothetical reactions to the clips.

While many participants assigned to watch the uncivil clips referenced the argumentative or negative tone of the congressional exchange, participants who viewed the civil treatments recognized the civility or respect with which the representative and the Master Chef judge engaged. After watching the Master Chef clip, one participant noted that Lydia gave “good constructive feedback,” while another commented, “It seemed like she gave pretty kind constructive criticism, and from her perspective it would have been easy to be rude and condescending, but I think she at least turned the meal down in an understanding and educative manner” (participant 2909). Of those who watched the political clips, one participant noted that Representative Cummings was “respectful, logical, and well-spoken. I appreciated that.” Others said that Cummings’s calm demeanor “made me listen” (participant 2969). In other words, participants were aware of the civility or incivility of the televised individuals and acknowledged that the language used had an impact on their willingness to keep watching and their openness to the speaker’s critiques.

Finally, others made a clear connection between the tone of the clip they had watched and their own media consumption habits, providing qualitative evidence for the arguments made in chapter 4. One participant acknowledged how difficult it was to keep watching even the thirty-second clip in the experiment:

I almost hit the pause button but thought I’d stick it out because it wasn’t very long. It is this type of stuff (people bickering and being rude to each other and there is always one who is more domineering over the other) that when I see it I quit watching. No matter the topic, I’ll turn it off or skip over it. (participant 2151)

Similarly, another participant suggested the exchange between Jordan and Richards was representative of “typical bureaucrats. Congressman asking, loudly, talking over another person, not letting the other person say anything. While the woman supposedly there to answer questions deflects them and tries to make her written statement instead of answering the question. Which is why I don’t watch that kind of “news” or programming” (participant 3700). Several participants were turned off by the tone of the Master Chef clips as well. As one participant wrote, “I [hate] shows that constantly put people down and I don’t watch them!” (participant 2852). Incivility turns certain people away from political information and discussion.

Others, however, were drawn into the video debate enough to offer their own opinion about the contested issue. Of those who commented, 22 percent engaged with the content, and the vast majority of these comments (91 percent) were civil. Among those who watched the Master Chef videos, many opinions fell into two categories: they expressed a commitment either to classic dishes or to a willingness to try new things. For example, one participant noted, “I agree completely [with the judge]. I cook with friends who add this and that and this and that. The final result is muddled. I love the classics and then tweeking [sic] the classics. No more” (participant 863). Another disagreed, arguing that the judge could have tried to balance her critique with the recommendation that “he might want to try a new or different spice next time. Especially with cooking (which I’m not a cook) if people never tried anything different we’d all be eating plain hamburgers. How boring!” (participant 1632). Particularly in the civil condition, respondents felt they could offer their own critique of the contestant’s dish.

For those who viewed the CSPAN clips, opinions spoke to three overarching themes: abortion policy and Planned Parenthood generally, the alleged video that was the specific topic of the congressional hearing,5 and Representative Cummings’s commentary in the civil clip about respecting the rule of law. As we might expect from public opinion research into American opinions on abortion (e.g., Press and Cole 1999), participants’ opinions varied in their direction and intensity. Some participants, like this one, acknowledged that Planned Parenthood provides a wide range of services for young women:

Planned parenthood is important for all ages. As a young adult, I find it important to be prepared for parenting. Some people may not have the ability to wait years and years to have a child. People get older. People may not be financially stable enough to have a child then they may feel having a child without planning is a priority because of their age and time clock. That’s why Mr. Cummings broadcast was important for everyone view. Parents’ decision to have a child may not have always have been planned it’s more of a surprise or spontaneous timing situation. That doesn’t mean that people aren’t prepared, but with training before pregnancy people can be prepared in classes like home ec and parenting classes. It is very important to have planned parenthood classes (participant 2281).

Others argued that the government should not be supporting Planned Parenthood because that support amounted to the implicit sanctioning of infanticide. Participant 3274 wrote, “Planned parenthood is nothing but a government funded murder facility. This man [Rep. Cumming] says he must uphold the law which includes child abuse laws. Child abuse in the U.S. is such a terrible crime but murdering babies before they’re born is perfectly legal. What a joke.” In both the civil and uncivil conditions, participants expressed support for and opposition to Planned Parenthood, legalized abortion, and the government’s role in funding the organization’s services (even, in some cases, while acknowledging that the government was not funding abortion services specifically).

Beyond attitudes about abortion and government provision of health services, people also engaged around ideas of institutional legitimacy and the importance of rule of law. In the civil CSPAN clip, Elijah Cummings argues, “You are doing what is within the bounds of the law, and you know, there are a lot of things I don’t like, a lot of laws I don’t like, but I still live in the United States of America and there’s a system of government, and I as a lawyer and a member of Congress I’m sworn to uphold those laws. Now, I might want to change them, I’ll do everything in my power to change the ones I don’t like, but in the meantime, that’s where I am.” Many participants agreed with him and demonstrated a more nuanced understanding of representation and political activism in the United States. One participant stated, “I agree with his comments. There are laws that I personally do not like but I will abide by them while I work at trying to have them changed” (participant 501). Another noted that Cummings’s argument stands in stark contrast to discriminatory laws against African Americans throughout U.S. history: “ ‘Its the Law, Its the law’ he repeats—it was also ‘the Law’ in Nazi Germany to send Jews to gas chambers—it was also ‘the law’ in our own antebellum south to keep black people in slavery. There is a LAW far above Elijah Cummings and a God to whom he and his fellow baby murderers will answer” (participant 1225).

Still others tied Cummings’s argument to concerns about Congress’s representation of citizens over special interests and major donors. One participant wrote:

I agree with Mr. Cummings. If we don’t agree with a law, then it is up to us to change it. As long as something is law, it has to be obeyed and enforced, otherwise what is the point of government? The problem in today’s government is special interest groups using their money and influence to push legislation through that is usually not in tune with the will of the people. This is the reason behind the unrest in this country. We are not being represented, therefore, we have no real power over our own lives. (Participant 1471)

Similarly, another participant agreed that Representative Cummings was correct and that we did not have the right to disobey the majority’s decision. “However, in saying that,” he wrote, “I believe that many members of congress do not represent the views of their constituents but simply that of their donors…many of whom do not live in their districts” (participant 767). These participants saw an opportunity to discuss not only policy outcomes, but also overarching political principles.

Some participants combined all three themes in their response and offered their opinion about each level of the policy debate—Planned Parenthood generally, the video’s contents specifically, and the overarching principle of rule of law. One participant in the civil condition teetered on the brink of civility in his own response, explaining, “I have such strong feelings against Planned parenthood [sic] that I can’t find words to be tell you what I think. It’s wrong to kill a child and sell their parts. It may be law but it’s bad law. To give my tax dollars to these vile people is wrong” (participant 488). Other participants tied the various arguments together to reach the opposite conclusion. Participant 785 wrote, “The comments by Representative Cummings are reasonable and accurate. When abortions are performed at Planned Parenthood agencies, that is within the law and, hopefully, will remain that way. I support a woman’s right to choose.”

In the vast majority of cases, participants who offered an opinion or commented on the tone of conversation maintained a civil tone. Only 9 percent of all of the comments were coded as uncivil (see table 5.3), and that incivility took two primary forms: name-calling and aspersions directed toward the individuals in the clips, and more general characterizations of politicians, reality television, or other groups. Many of these insults were left without any additional commentary—“That Representative is a dick” (participant 101) or “What a bitch!!!” (participant 252)—but others combined incivility with opinions about politics or policy more generally. Participant 438 wrote, “Self serving, do nothing congress. Putting their own opinions above all else and making the sika [sic] virus tied in with de-funding planned parenthood. What a bunch of idiots that should not even be classified as human beings.” Participant 3114 also used incivility to express his or her opinion about Planned Parenthood and abortion: “Planned parenthood murders babies and then sell the body parts. They are disgusting.”

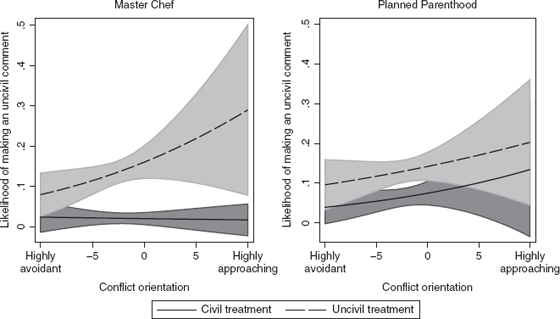

While incivility was less frequent in the comments than reflection on the quality or content of the conversation being held in the clip, the participation-quality hypothesis suggests that each of these elements varies systematically with individuals’ conflict orientation and their exposure to incivility in the treatment clips. Before we investigate the effects of the interaction between conflict orientation and incivility, it is important to assess the treatment effects generally. Did exposure to incivility produce greater incivility in individuals’ own comments, as social-learning theory would suggest? Does civility promote more engagement with the issues themselves, as measured through a willingness to offer an opinion, agreeing or disagreeing?

One-way ANOVAs demonstrate that the treatments have an effect on both the presence of incivility (F(3, 1953) = 17.86, p = 0.001) and the expression of an opinion in participants’ comments (F(3,1953) = 152.57, p = 0.001). Looking at the likelihood that comments will contain incivility, Bonferroni tests show that these differences are driven by the presence or absence of incivility in the clips shown. The uncivil Master Chef and Planned Parenthood clips both have a higher incidence of uncivil responses than do their civil counterparts; however, there is no difference between different types of programs using the same tone. In other words, people who watched an uncivil Master Chef clip were no more or less likely to use incivility than those who watched the uncivil political clip, but those in both conditions were more likely to use incivility than the participants who viewed civil Master Chef or CSPAN clips.

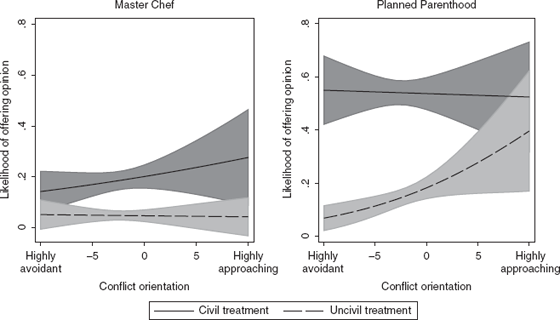

Although the type of program did not affect the expression of incivility, it did shape participants’ likelihood of offering their own opinion on the issue. As figure 5.5 shows, participants were substantially more likely to offer an opinion if they had watched the civil Planned Parenthood clip than if they had watched the uncivil clip about the same topic, and the same pattern holds for the Master Chef clips. As deliberative theorists would expect, civility created a space for more people to offer their own perspective on the issue. Regardless of the tone of the clip, participants were also more likely to offer opinions about politics than about food. They were about as likely to offer an opinion about Planned Parenthood in the uncivil condition as they were an opinion about the Master Chef competition in the civil condition.

FIGURE 5.5 Incivility reduces participants’ probability of stating an opinion.

Source: GfK.

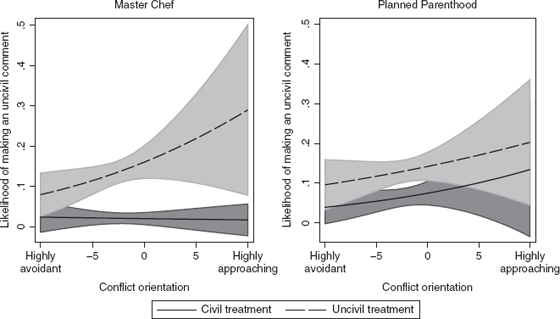

It is clear that the presence or absence of incivility in the video clips has an impact on what people say in response. But how does conflict orientation come into play? The participation-quality hypothesis argues that conflict-approaching individuals who are exposed to incivility will be more likely to use incivility in their own online comments. To test this hypothesis, I estimated two models—one for the Master Chef treatments and one for the Planned Parenthood treatments—to explore the interaction between incivility and conflict orientation. Because logistic regression results and interactive effects are difficult to interpret from a standard table, the results are presented in graphical form. Figure 5.6 suggests that the primary driver of an individual’s use of uncivil language is assignment to the uncivil treatment; conflict orientation has a statistically insignificant effect on the use of incivility in one’s own comments. However, it is possible that this relationship, particularly with regard to the Master Chef treatments, is statistically insignificant because there are so few individuals who identify as strongly conflict-approaching. With so few individuals at the highest end of the scale, the confidence interval increases, obscuring any differences that may result from conflict orientation. The slope of the lines suggests that among those who saw the civil treatment, almost no one, regardless of conflict orientation, made an uncivil comment. Among those who were exposed to incivility, the most conflict-avoidant individuals had about a 10 percent likelihood of using uncivil language in their comments. The most conflict-approaching individuals, on the other hand, used uncivil language in approximately 20 percent of their comments. The same pattern does not appear when looking at the Planned Parenthood treatments. For participants who watched these clips, there is once again a statistically significant direct effect of the treatment: those who watched the uncivil clip use more incivility in their comments. If there is an effect of conflict orientation, it is statistically undetectable, but, based on figure 5.6, it appears to affect the civil and uncivil treatments similarly. The results do not support the hypothesis because there is no statistically significant effect of conflict orientation on participants’ likelihood of using incivility, but they do suggest that further investigation of the relationship could benefit from oversampling of highly conflict-approaching individuals.

FIGURE 5.6 Presence of incivility is strongest predictor of participants’ use of incivility.

Note: Figures display predicted probabilities based on two separate logistic regressions. The direct effect of the treatments is statistically significant; the interactive effect with conflict orientation is only significant for the Master Chef clips.

Source: GfK.

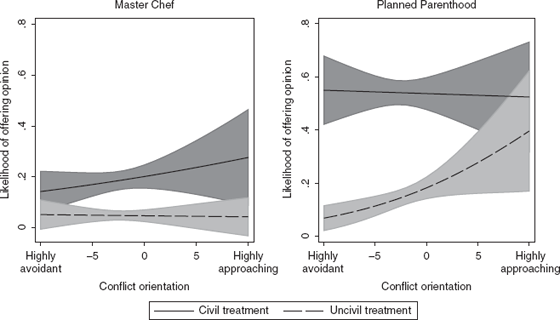

These findings provide slight support for my hypotheses: the conflict-approaching are using more incivility, particularly when exposed to incivility themselves. Incivility begets incivility; those who see it, particularly the conflict-approaching, turn around and use it in their own political commentary. This makes the conflict-approaching out to be the “bad guys”; they are engaging, but in a way that is detrimental to overall deliberative values. However, the conflict-approaching are also more likely to offer an opinion about political topics, regardless of whether they watch a civil or an uncivil video. As figure 5.7 shows, many participants felt strongly enough about Planned Parenthood and abortion-related issues to offer some type of opinion in their response to the video. In the civil condition, conflict orientation played a minimal role—the most conflict-averse and conflict-approaching all had about a 55 percent probability of articulating an opinion. In the uncivil treatment, however, the conflict-avoidant shied away from offering an opinion. The conflict-approaching, on the other hand, were just as likely to offer their opinion in the face of incivility as they were in the civil condition. While these findings highlight the importance of civil discourse for encouraging others to enter into the conversation, they also suggest that the conflict-approaching do not need civil conditions to engage; they can operate just as easily in the face of name-calling and belittling commentary.

FIGURE 5.7 Conflict-approaching participants offer opinions regardless of treatment.

Source: GfK.

***

Previous research has demonstrated that conflict orientation shapes individuals’ political engagement. My research is consistent with this work. While the conflict-approaching are more likely than the conflict-avoidant to participate in high-conflict activities, such as commenting on a blog or persuading others to vote, there is no difference across conflict orientation in participation in midrange to low-conflict activities. When these findings are considered in light of variation in political interest, conflict orientation plays a greater role in the likelihood of participation for the most politically interested.

When these voices are heard, what do they say, and how do they say it? We model our political conversations on those we read, watch, or listen to, so it is no surprise that when our role models for how to talk about politics, cooking, or any other issue incorporate incivility into their conversations, we do too. The qualitative evidence from this chapter suggests that people do monitor the tone of conversations they watch on television, commenting when they find a particular exchange to be an egregious violation of norms or a surprising demonstration of civility and respect. Although the evidence does not paint a crystal-clear picture of the role of conflict orientation in shaping the quality of discourse, it at least suggests that the conflict-approaching are even more likely to use incivility when they see it on television than are their conflict-avoidant peers. At the same time, the conflict-approaching are more likely to offer their opinion on contentious issues, such as abortion or the role of Planned Parenthood, regardless of whether they watch a civil or an uncivil video clip. Their conflict-avoidant counterparts are silent in the face of incivility. Like time or public-speaking skills, a conflict-approaching orientation is a resource that helps certain citizens get involved in politics and express their ideas.

These results paint a picture of a political world in which the conflict-approaching are more likely to engage in certain types of behaviors and, once engaged, to articulate their opinions, even in ways that are not always civil. In the realm of political engagement, differences in behaviors across the conflict-orientation spectrum affect whose voices get heard and what those voices are saying. As I discuss in the next chapter, a political world in which the conflict-approaching are engaging in political discussion and communication while the conflict-avoidant stay silent could have implications for the quality of our democratic discourse and the ability to hear the other side.