I’ve been thinking a lot about civility, civic duty, and kindness, and how pervasive and powerful they are, how enduringly persuasive those qualities are in American life and how I see them all around me, day after day.

—C. J. CREGG, “THE LONG GOODBYE,” THE WEST WING (2003)

LOOK AT ANY survey about American politics today, and you will see that many Americans would disagree with fictional White House press secretary C. J. Cregg about the prevalence of civility, civic duty, and kindness in contemporary politics. After all, examples of rudeness and cruelty abound in today’s political media: a recent news cycle included stories about singer Ed Sheeran leaving Twitter because of trolls’ cruelty (O’Connor 2017) and the president’s Twitter attack on CNN journalist Mika Brzezinski, in which he called her “crazy,” “low I.Q.,” and “bleeding from a face-lift” (McAfee 2017). Lest these examples lead you to believe that Twitter is the prime culprit in the rising ubiquity of incivility, just take a look at the comments on any YouTube video—the responses to Black Lives Matter rallies or campus lectures by Manhattan Institute fellow Heather Mac Donald or white nationalist Richard Spencer. Incivility is a part of contemporary American politics, and it is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

Given this reality, effective democratic citizens could benefit from a coat of armor that protects them from the negative impact of incivility. As I have shown throughout this book, a conflict-approaching orientation is one type of armor. The inclination to approach conflict—to confront those with whom you disagree, to publically engage in arguments, and to be excited about the prospect of debate—mitigates some of our normative concerns about political incivility. When faced with incivility, people who are conflict-approaching feel more positive emotions. They are less likely to keep seeking out uncivil news. And while they are slightly more likely to use incivility in their own political conversations, they are also more likely to offer substantive opinions about the issues being discussed. In these ways, they are better able to cope with the reality of contemporary political conversation and make space for incivility to play a productive role in mass political behavior.

SUMMARY AND CONTRIBUTIONS

This book began by laying out incivility as a contested concept that can be defined in a variety of ways. Some scholars and citizens identify incivility in the content of a political message—in the stereotyping of a particular race or minority group or threats to democratic rights—while others conceive of it as a function of the tone of communication. It is this second understanding that I use throughout this book, operationalizing incivility as name-calling, finger-pointing, aggressive language, interruption, and insults. When this sort of nasty language is used in political media—whether on a talk show or on Twitter—scholars have shown it has a range of effects on political behavior. Incivility lowers trust in government, reduces perceptions of government legitimacy, and discourages open-minded deliberation (Mutz 2007, 2015; Gervais 2014). It also encourages participation and improves recall of candidates’ issue positions (Brooks and Geer 2007; Kahn and Kenney 1999; Mutz 2015).

The primary argument of this book is that the effects of incivility depend on differences in how individuals react to conflict in their interpersonal conversations. Following Mondak’s (2010) paradigm of heterogeneous treatment effects, the findings in this book overwhelmingly demonstrate that incivility negatively affects certain individuals more than others. The conflict-avoidant become weaker democratic citizens, associating politics with a range of negative emotions, searching for more uncivil news coverage, and engaging less in political activities. From a participatory standpoint, if the conflict-avoidant and conflict-approaching were otherwise similar—if the tendency to be one or the other were not correlated with socioeconomic or demographic traits—we might not worry about these distinctions. The conflict-approaching would hold the same preferences as the conflict-avoidant and would be able to express them to political leaders on behalf of everyone. However, this is not the case. The conflict-avoidant are also more likely to be less educated, members of minority groups, and women—groups that are traditionally underrepresented in politics (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman 1995; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady 2012). The interaction between incivility and conflict orientation has the potential to exacerbate political inequality.

Humans are naturally inclined to engage with certain stimuli and avoid others; it’s how we know to run away from a king cobra but want to cuddle puppies. Many stimuli fall somewhere in between these two, and individual differences lead one person to avoid or approach a particular activity or creature more than another person would. Over the course of this book, I have demonstrated that these individual differences play out in our conflict orientation—some people are more likely to avoid conflict in their lives, while others embrace and thrive on it. While psychologists have argued that conflict orientation is a relatively entrenched component of one’s personality, they have primarily focused on how it might be shaped by cultural and life-span factors. For example, as individuals age or become more educated, they may become more comfortable with and accepting of conflict (Birditt, Fingerman, and Almeida 2005; Eliasoph 1998). By examining longitudinal data on individuals’ conflict orientations, even over a small increment of time, this book not only speaks to previous psychological findings but also demonstrates that changes in conflict orientation occur as small fluctuations around an initial stable point. An individual who is predisposed to be highly conflict-avoidant is not going to become highly conflict-approaching simply by growing older and becoming more educated.

Across six studies, I demonstrated that there is substantial variation in individuals’ conflict orientation; even in a sample of 350 people, you can find some individuals who avoid conflict at all costs and some who take every opportunity to start an argument. This book marks one of the first analyses of conflict orientation using large-N, representative survey samples. The ability to look at the conflict orientation of a wide range of people over time offers insight not only into the interplay between conflict orientation and incivility in the political sphere, but also into the connection between conflict orientation and a broad range of psychological phenomena.

The empirical portion of the book offers evidence that conflict-approaching individuals are better able to handle the challenges presented by uncivil politics than their conflict-avoidant peers. In the third chapter, I focus on affective reactions to incivility across two different samples and three different pairs of video clips. While the specific emotional responses vary with the clips, the overarching pattern is clear: the conflict-avoidant are more likely to experience negative affect—disgust, anxiety, and anger—in the face of incivility. The conflict-approaching feel more positively, reporting greater amusement, entertainment, and enthusiasm. What is more, these reactions are not specific to politics; the patterns hold both when watching political clips about abortion or the U.S. budget deficit and when exposed to the judging process on Fox’s Master Chef. From these results, we see the first indication that the conflict-approaching are not turned off by incivility. If anything, it draws them in and makes them more engaged than they were previously.

The divergent experiences of the conflict-avoidant and conflict-approaching are seen again in participants’ media habits and decisions when searching for information. People choose to seek out political information, and they choose where and how they want to receive that information. These choices are most clearly a function of a person’s interest in politics, but can also be shaped by an assessment of the likelihood that a given choice will expose one to incivility and conflict. When I categorize media platforms by their likelihood of incivility exposure, I find weak evidence that conflict orientation shapes preferences—both for how frequently individuals turn on the news and what sorts of platforms they turn to when they do. More specifically, network news and social media are preferred far more by the conflict-avoidant than the conflict-approaching. Norms of journalistic objectivity steer network news away from broadcasting uncivil political conversations, while the potential to maintain homogeneous networks on social media can act as a barrier to incivility as well.

Conflict orientation only slightly shapes overall media choice in surveys, but the experimental evidence in chapter 4 suggests that it affects the choices people make about consuming news in the wake of incivility. The conflict-approaching spend less time watching additional video clips, watch fewer uncivil clips, and watch fewer political clips than the conflict-avoidant. This may seem like a strike against the conflict-approaching; after all, we want citizens to pay attention and acquire political knowledge in order to be engaged democratic citizens. However, not all attention is normatively positive; when people are anxious, they seek out information about whatever is causing their heightened anxiety. In this case, the conflict-avoidant, who have already been shown to experience greater anxiety in the face of incivility, are seeking out political videos and uncivil videos because that content is causing them to feel anxious. The conflict-approaching, in contrast, are satisfied once they have viewed uncivil political content and are content to shift to other clips or to other activities entirely.

When we turn to the effects of incivility on the quantity and quality of political engagement, the conflict-approaching once again come out ahead. Like media platforms, political activities can be categorized based on their likelihood to expose an individual to incivility. Some of the most important activities, including voting, are low-conflict and offer minimal risk. Others, such as posting on social media, persuading others to vote, or protesting, open an individual up to uncivil political discourse, even if that discourse is not directed at them. Data from the Project Implicit study demonstrate that there is no difference between the conflict-approaching and conflict-avoidant in their likelihood of participating in low-conflict activities. When we increase the risk of exposure to conflict and incivility, however, the conflict-approaching become more likely than their conflict-avoidant counterparts to get involved.

This observational finding is buttressed by experimental evidence. The GfK study demonstrates that the conflict-approaching are more likely to share a story on social media than their conflict-avoidant counterparts, regardless of whether that story is civil or uncivil. The quality of conflict-approaching individuals’ engagement with uncivil news is also more robust than that of their conflict-avoidant peers. While conflict-approaching individuals were more likely to use incivility in their comments about the uncivil congressional Planned Parenthood hearing and Master Chef judging, they were also more likely to offer opinions about the issues presented in each clip. While both the conflict-avoidant and conflict-approaching offered opinions about Planned Parenthood after watching the civil clip, the conflict-approaching were just as likely to offer comments when they watched the uncivil video. They were capable of discussing politics regardless of whether the elected officials on their screen were calm or shouting.

Given all of these results, the rise of incivility in political media—critical institutions that inform and motivate citizens—has transformed the nature of who gets involved by changing the resources needed to engage successfully with the style and structure of political discourse. Specifically, citizens now need to be able to regularly tolerate or even welcome incivility in the political sphere in order to participate comfortably in the broader democratic process. Citizens with a conflict-approaching orientation, who enjoy conflict, have the ability to navigate political media and certain types of political activities in a way their conflict-avoidant counterparts do not. Certain Americans are marginalized in this political environment not only on the basis of ascriptive or demographic characteristics such as race, gender, or income, but also because their psychological preferences are incongruent with the modern practice of political discourse.

These findings add to the continuing conversation about the role of civility and incivility in American politics. The tension between the characteristics of strong deliberative and participatory democracy has been well documented (e.g., Mutz 2006), and the evidence presented in this book only reinforces it. As I elaborate later in this chapter, writing this book leaves me skeptical that civil discourse is truly a panacea for America’s political ills. Rising incivility raises some serious concerns for the state of our democracy, but a shift toward an extremely civil society does not necessarily solve the problems associated with incivility. I find that individuals who are turned off by incivility are not more engaged by civil presentation of policy issues or campaign information. Civility does not make the conflict-avoidant more entertained or amused, nor does it provide clear emotional benefits to the conflict-approaching. In other words, the findings detailed in this book highlight how challenging it can be to evaluate incivility’s normative benefits and harms to the political system.

The bulk of the research presented in this book relies on experiments. Experiments have been clearly identified as the gold standard in studying causal mechanisms (Druckman and Kam 2011; Spencer, Zanna, and Fong 2005), and those implemented in this book were designed specifically to maximize internal validity while maintaining a sense of ecological realism. However, there are several methodological choices I made that should be considered when designing future research on incivility and conflict orientation.

Experimentalists know to be careful about the extent to which they generalize their findings from nonrepresentative samples to the broader population. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the experiments presented in this book have some significant limitations when it comes to their applicability across different dimensions. For example, each treatment used in this book is visual; participants watched a video clip rather than reading a newspaper article or listening to an audio recording. Television, and cable television in particularly, is one of the most common venues for uncivil discourse (Berry and Sobieraj 2014), and specific attributes of the medium—the presence of visuals and, in particular, the use of close-up camera perspectives—make it more likely to convey violations of social norms for communication (Mutz 2015; Sydnor 2018). Therefore, while these treatments represent the most likely way in which participants would experience incivility in their daily lives, the relationship between televised incivility and conflict orientation might be different than the relationship between conflict orientation and incivility on social media or talk radio.

While the treatments were constant in their televised presentation, they varied in the types of issues discussed in an uncivil manner. The SSI study used clips that discussed two different economic issues, while MTurk Study 2 and GfK assessed individuals’ responses to a highly salient social issue—abortion and funding of Planned Parenthood—as well as entertainment television in the form of Master Chef. While effect sizes vary across the different issues, the relationship between incivility, conflict orientation, and the outcomes of interest typically follows the same pattern regardless of the issue being presented. There are some caveats. For example, in chapter 3, I found that some emotional responses, such as anxiety, manifest the same way across video clips, but others change. Conflict orientation conditions feelings of anger and disgust when watching uncivil clips from Master Chef or about economic topics, but does not have an effect on individuals’ reactions to an uncivil exchange about Planned Parenthood. Additional research may be able to tease out whether these differences are an artifact of the experiment or if the contentious nature of the issue itself matters. However, these findings increase my confidence that I have captured an enduring interaction between conflict orientation and televised incivility that occurs regardless of whether uncivil rhetoric is being used to describe more or less prominent issues.

As I acknowledged earlier, this book represents one of only a few attempts to document conflict orientation through several large-N surveys. With the exception of the Qualtrics Panels survey, each of the survey experiments presented here gives us a glimpse into individuals’ feelings toward conflict at a single moment in time. However, implicit in my argument is a claim that political participation has changed as incivility has become a greater presence in political communication. Long-term panel data on conflict orientation would not only offer greater insight into my claim that this trait is in fact stable and exogenous to our political experience, but also allow scholars to track who is participating as incivility inevitably ebbs and flows over the next several decades.

THE FUTURE OF INCIVILITY RESEARCH

The six studies in this book offer a great deal of insight into the interplay between conflict orientation and incivility and its effects on political behavior. However, even after documenting the ways in which the conflict-approaching are better suited for today’s confrontational and vitriolic political climate, I am left with further questions about the role of conflict orientation in and the impact of incivility on politics. These questions can motivate further research at the intersection of political psychology and political communication by those scholars interested in how individual differences shape our reactions to political incivility.

The first set of open questions focuses on conflict orientation. My findings demonstrate that when faced with incivility, the conflict-approaching are able to effectively engage in politics while the conflict-avoidant struggle with negative emotions, biased information processing, and less participation in political activities and conversation. One might expect, then, that in the absence of incivility, the conflict-avoidant would experience more positive outcomes. This does not seem to be the case; none of my results demonstrates that civility exercises a dramatic pull for the conflict-avoidant. Exposure to civility does not produce more positive emotional reactions nor less biased information search. While civility may encourage the conflict-avoidant to offer their own opinions about political events, it clearly does not draw people in as much as incivility does. So what does it take to engage the conflict-avoidant? Is there another approach to communicating about politics that could lead them to experience politics in a positive light, or are they as lost to political engagement as the least politically interested citizens? Future research could explore the extent to which different interventions produce greater participation or positive affect in the conflict-avoidant.

This book focuses exclusively on the implications of incivility for mass behavior. It argues that incivility has a place in political communication because of the positive effects it can have, whether by holding powerful individuals accountable or by encouraging citizens to become a part of the political process. It leaves open the questions of the effects of conflict orientation and incivility on political elites. Presumably, it takes a comfort with conflict to run for public office. If this is the case, the vast majority of our elected officials are likely to be at least somewhat conflict-approaching. What does this do to negotiation and compromise on an elite level? On the one hand, conflict-approaching Congress members might be better able to arrive at solutions even when faced with nastiness from the opposing party. On the other hand, we can imagine that these elected officials, more willing to use incivility in their own speech, would simply hunker down on opposing sides and produce policy gridlock. Thoughtful treatment of the effects of conflict orientation on politicians, journalists, and others could help political scientists understand how institutional constraints and personality interact to affect governance.

Similarly, while incivility might have some desirable consequences for mass behavior, it is unclear that it produces positive outcomes at the elite level. Incivility appears to rise as affective and substantive polarization increase (Jacobson 2013; Shea 2013; Shea and Sproveri 2012). Citizens, in turn, blame political incivility on the opposing party and double down on their own party, encouraging leaders to stand firm and avoid compromise (Wolf, Strachan, and Shea 2012). Incivility might encourage certain types of democratic expression and engagement, but if elites are perpetually engaged in policy gridlock and partisan sniping, that expression and that engagement are ineffective.

Beyond questions about the impact of incivility on the elite level, this book also opens additional avenues of research into the interactive effects of incivility and the communication environment. Incivility’s effects may be platform dependent; incivility on Twitter may produce more anger or outrage than incivility in a comments section, for example. Beyond media effects, scholars can, of course, continue to explore how the strategy for measuring incivility or the characteristics of the speaker and receiver shape their responses to uncivil language. Gervais (2011, 2015) and Druckman et al. (2019) have cleared an initial path in this regard, focusing on differences between incivility from one’s copartisan and incivility from a member of the other party. As one Washington Post analysis pointed out, “If Trump’s petty and vindictive, he’s petty and vindictive to people whom his base hates, and many of them are perfectly fine with that, at a minimum. It’s not the sort of civility that people expect from Washington—but that’s exactly what many of his supporters wanted. They wanted that incivility and embrace it” (Bump 2018). Partisanship affects our reactions to incivility, but what about the status of the speaker as an elected official? Her race or gender? And whether the listener shares her gender or ethnic identity? Investigating the interaction of uncivil communication and these individual-level characteristics will help researchers understand when and under what conditions incivility has positive and negative effects.

Finally, future research should explore the extent to which conflict orientation reinforces or breaks down existing political inequalities. As I showed in chapter 2, conflict orientation is tied to gender, age, race, and education. Differences in political participation can also be explained by each of these characteristics: women, younger people, minorities, and those with less education are less likely to participate in politics, particularly in resource-intensive activities such as protest or contacting one’s member of Congress. If members of these groups are systematically less likely to engage in politics and are also more likely to be conflict-avoidant—a characteristic that I have shown also lowers the probability of participating—conflict orientation could be compounding already existing inequalities in the political sphere.

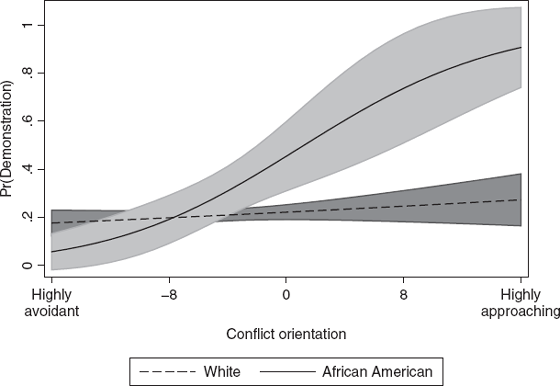

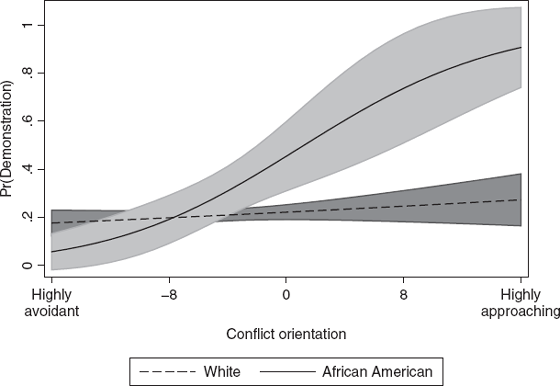

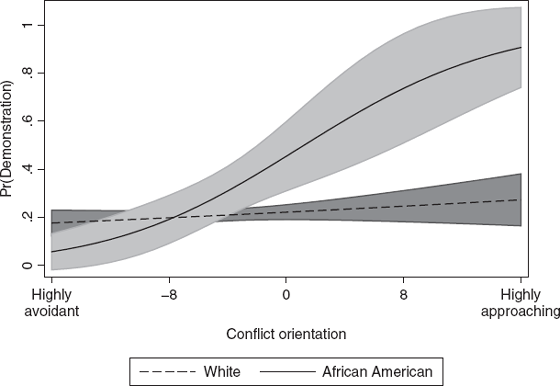

The studies used in this book offer few indications of this compound effect of conflict orientation and demographics. When I examined participants’ likelihood of participation at the various levels of conflict orientation across demographic categories, the interaction, for the most part, was statistically insignificant.1 However, one result in particular stands out and should be explored further. Conflict orientation interacts with race—specifically, whether an individual is African American or white—to create substantial disparities in the likelihood of attending a protest or demonstration. However, it does so by dramatically increasing the likelihood of African American participation while having minimal effect on whites. As figure 6.1 shows, extremely conflict-avoidant whites and blacks (those with CCS scores below −8) were equally likely to participate in demonstrations, around a 20 percent likelihood. But while highly conflict-approaching white participants hovered at a 25 percent probability of having participated in a protest or demonstration in the past year, the most conflict-approaching African Americans are more than three times more likely to report participation in a protest.2 Rather than emphasize traditional divisions in participation, this result suggests that conflict orientation may facilitate a “closing of the gap,” offering members of marginalized groups a resource that helps them participate in an activity that would otherwise be very difficult. It also helps explain the rise of groups like Black Lives Matter in an era rife with political incivility and suggests that there are other dimensions of the relationship between conflict orientation and incivility that would be valuable to explore.

FIGURE 6.1 Conflict orientation and race shape protest behavior.

Note: Probabilities are reported from a logistic regression of conflict orientation and race on having attended a demonstration or protest in the past year. The regression controls for personality, gender, age, education, party identification, party strength and political interest.

Source: Project Implicit.

(IN)CIVILITY AND DEMOCRATIC CITIZENSHIP

In June 2018, civility rose to the forefront of the national conversation after White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders was asked to leave a restaurant in Lexington, Virginia. The owner of the restaurant, Stephanie Wilkinson, said she had made the decision with the support of her staff, many of whom were gay or had immigrated to the United States and were therefore members of groups that had been targeted by recent Trump administration policies. The exchange did not violate standard conversational norms; Wilkinson noted that she was polite in her request that Sanders leave and that Sanders and her family were polite as they left the restaurant (Selk and Murray 2018).

The reaction from the online community was less genteel. While many people supported Wilkinson’s decision, others, including the president, were swift to respond with vitriol. “The Red Hen Restaurant should focus more on cleaning its filthy canopies, doors and windows (badly needs a paint job) rather than refusing to serve a fine person like Sarah Huckabee Sanders,” the president tweeted. “I always had a rule, if a restaurant is dirty on the outside, it is dirty on the inside!” Throughout this book, I have made the argument that incivility can be a good thing. For a set of Americans, it encourages positive emotions and greater participation. But to what extent does incivility have desirable consequences in the mass public and at the elite level? The incident at the Red Hen and its aftermath suggest that incivility provides several important democratic benefits while also raising concerns about our ability to communicate across identities and experiences.

For those who were upset with Wilkinson’s decision, the act of asking Sanders to leave the restaurant was in itself uncivil. Never mind that all parties behaved decorously, the demand was seen as the first step down a road where dining establishments are segregated by party, where Americans are “divided by red plates & blue plates” (Axelrod 2018). I could spend pages discussing the arguments for whether asking Sanders to leave should or should not be considered uncivil, and how the labeling of the action as uncivil has its own set of consequences for our interpretations of the event and subsequent attitudes about it. But these comments raised an additional question about the role of incivility in a democracy: Are there moments when uncivil behavior and language are part and parcel of good democratic citizenship?

In the days following Sanders and Wilkinson’s altercation, the Washington Post released an editorial decrying the lack of civility in the Trump era. The editorial team warned against incivility as a slippery slope to political violence, writing, “Those who are insisting that we are in a special moment justifying incivility should think for a moment how many Americans might find their own special moment. How hard is it to imagine, for example, people who strongly believe that abortion is murder deciding that judges or other officials who protect abortion rights should not be able to live peaceably with their families?” (Editorial Board 2018). Scholars who study the effects of uncivil or violent rhetoric find that violent rhetoric can affect individuals psychologically in much the same way that violent actions do (Barrett 2017; Teicher et al. 2010) and that violent rhetoric can lead to greater support for violent action (Kalmoe 2014). We should not lose sight of the fact that incivility, especially violent and hateful speech, can have harmful effects on individuals and communities.

But incivility can also be a necessary means by which we hold elected officials and powerful groups accountable. Sanders’s supporters saw the request for her to leave the Red Hen as an uncivil act, a violation of social norms for dining establishments. Others, like Vox reporter Zack Beauchamp, saw Wilkinson’s decision as a democratic moment in which a citizen “acted to punish a political official for a specific set of severe wrongs, not to harm an average customer whose political views she happened to disagree with” (Beauchamp 2018). Democratic republican government is premised on the idea that elected officials are responsible to citizens and that it is the citizens’ job to punish those officials who fail to meet their standards. Language and behavior that break social norms are sometimes a necessary part of that punishment. It can also be a way for citizens to draw attention to examples of government’s failure to support its citizens. In other words, uncivil rhetoric might serve as a slippery slope to greater violence, but it is also a vital tool in the citizen’s democratic arsenal.

This debate over the role of incivility in democratic life makes the findings from this book more important than ever. Incivility is an important and intractable part of politics. A world of perpetually civil agreement seems anathema to pluralist society. A promising step, then, seems to be to think about how we can be good democratic citizens in spite of incivility. The conflict-approaching, while not paragons of democratic citizenship, nonetheless are capable of engaging in politics even when it gets nasty. We cannot change everyone’s conflict orientation, of course, but we might think about ways in which the conflict-avoidant could be encouraged to overcome their aversion. Perhaps this is simply a matter of framing engagement as a moral imperative. In an interview with the Washington Post, Wilkinson noted that she is “not a huge fan of confrontation…[but] this feels like the moment in our democracy when people have to make uncomfortable actions and decisions to uphold their morals” (Selk and Murray 2018). While her natural preference would have been to avoid conflict, she felt she had to overcome her anxiety because of a higher moral commitment.

Alternatively, encouraging citizens to behave as if they are conflict-approaching might be more about teaching relevant skills than trying to tap into the moral frames that propel them to act. Here, engaging in politics in the face of incivility is analogous to public speaking. Many people experience extreme anxiety when asked to give a public speech or to stand up in front of a room full of people. They are naturally averse to the experience, which leads to negative emotional responses and a desire to avoid having to participate in any activities that might require them to speak in front of an audience. However, through the education system, certain types of employment, church groups, and other organizations, many people are given tools for overcoming their public-speaking anxiety. Whether they consistently “imagine the audience in their underwear,” practice a presentation for hours before delivering it, or simply stand up in front of people so frequently it becomes second nature, people learn how to deal with this experience that they would otherwise avoid. The same strategy—identifying ways of overcoming one’s aversion to conflict—could help citizens persevere in the uncivil political landscape and even engage in uncivil behavior when necessary.

Incivility—name-calling, insults, obscenities, finger-pointing—should not be the default in politics. As Hua Hsu wrote in a 2014 piece for the New Yorker, “There should be nothing controversial about everyday kindness; civility as a kind of individual moral compass should remain a virtue” (Hsu 2014). Like C. J. in the comment that opened this chapter, Hsu argues that our personal baseline should be to treat each other with mutual respect, to seek to understand others’ viewpoints, and to give people the benefit of the doubt. But Hsu takes the argument a step further: “But civility as a type of discourse—as a high road that nobody ever actually walks—is the opposite. It is bullshit” (Hsu 2014). America might have an “incivility problem,” but interventions that focus only on civility as the high road miss the mark. Civility alone cannot solve our political problems. Instead, it is a starting place. When name-calling and vitriol are used to promote democratic discussion and broaden the political conversation, we must follow in the footsteps of the conflict-approaching, finding entertainment and motivation in incivility.