Pieter van der Heyden engraved all seven Sins. They were published by Jerome Cock in 1558. Fortunately, all of Bruegel’s original drawings have survived. Their present locations are mentioned following the corresponding commentaries.

One of the seven drawings, “Avarice,” is dated 1556; the rest, 1557. Bruegel must have completed the originals for all of his most famous single series within two years. They were conceived and executed with engraving in mind. The consistency of style and composition leaves no doubt as to that.

Some deviations between details of the original drawings and the corresponding engravings indicate that Bruegel as designer had less than complete control over the engraver. Van der Heyden, or possibly Cock as publisher, exercised censorship in certain small details, notably in the engraving of “Lechery,” as pointed out in the accompanying comment.

This series is sometimes called the Sins, sometimes the Vices. The difference in terminology is not important, but does afford an insight into the subject. Theological tradition and consideration of rhetorical effect give sin a slight edge. After all, “The Seven Deadly Sins” has the sort of sulfurous aroma which proves alluring on theater marquees and book covers. On the other hand, “Vices versus Virtues” affords “alliteration’s artful aid.” And, psychologically speaking, Bruegel is, in fact, concerned with depicting vices (continuing evil habits or practices) rather than single sins (conceived as isolated, individual acts transgressing moral laws).

For the sake of simplicity, we refer here to the series as Sins and note that they do denote vices—for the habitual and inveterate aspect of the sinful conduct is what makes it vicious in the eyes of the artist, and of the school of thought which he expresses.

At first glance these prints are likely to give a modern viewer the feeling that this is all most assuredly “out of this world”—and that there is much more implicit than can be understood in a single seeing. Here monsters and monstrous actions are multiplied in unrealistic or surrealistic landscapes. Here are pungent symbols, some reminiscent of the “iconography” of Bruegel’s great predecessor, Bosch—others seemingly peculiar to Bruegel—yet all highly charged and emotionally loaded.

One wonders, sometimes: is the more appropriate reaction a loud guffaw, or a whimper of despair? All this is demon-infested, yet with a difference; it is like an Elizabethan melodrama, mingling physical violence, moral horror, and grotesque slapstick.

Compare one of the Sins with one of the Virtues which follow (excepting only “Fortitude”). The difference is immediately apparent. The Virtues are impossible juxtapositions, but of completely possible and usual people. The diabolical element is absent. They are didactic, but sans devils.

Clearly the Sins have urgent messages to impart. But what are they? What was Bruegel, landscapist turned moral teacher, trying to tell his fellow Flemings?

Scholarship permits surmises to be made more confidently today than half a century ago (when Bastelaer’s almost definitive catalog of the engravings was fresh from the press in Brussels)—or even than a dozen years ago. In the following comments some highlights will be offered. They are intended to contribute to the satisfaction and the depth of meaning that the engravings will give.

Do not look on the seven Sins as pictures of future hells that await sinners after death. True, devilish things are happening. Monsters are making “life” miserable for tormented men and women. One might doubt whether theirs can be called a “life,” even with benefit of quotation marks. Nevertheless, though the Sins certainly take us out of this world, they are not attempting a Dante-like tour of the realms of eternal punishment.

The scene of these Sins is, rather, within the souls of men. Of men, mind you, not of just one man. None of these Sin drawings was intended as a single solitary sinner’s foreboding of his future. These are social situations, with social outcomes and implications, even with regard to a vice seemingly so non-social or anti-social as “Sloth.”

Tolnay, a Bruegel critic deserving of mention again, interprets this series as evidence that Bruegel believed all men to be sinful beyond all help or change—so basically sinful that even if one sinful passion is cast out, another rushes in to fill the gap. Thus Tolnay writes: “Bruegel deprives the hereditary sins of their supernatural and destinal qualities.” In other words, he does not picture sin as an infernal importation or injection into the lives of men who would, if left to themselves, remain free from it. If sin is, on the other hand, something that men originate within themselves, then there is no point in blaming an Evil One, a seducing Satan.

Bruegel—again according to Tolnay—understands the sins “as natural instincts” and “seeks the mainsprings of the forever ineradicable vileness of the real world”—a vileness which is, in fact, a result of human “devotion to the acting out of impulses.”

Here is a good place to introduce another interpretation which seems better able to unfold the richness and validity of Bruegel’s Sin subjects. This interpretation is identified with two of the foremost contemporary Bruegel scholars: Fritz Grossmann in England, and Carl Gustav Stridbeck in Sweden. (References to works of theirs have been given earlier.) They find graphically displayed in the Sins the viewpoint of a religious-ethical movement variously known as “Libertinism” or “Spiritualism” which was influential during Bruegel’s lifetime and within his intellectual circles. The leading spokesman of the viewpoint in the Netherlands was D. V. Coornhert, himself both an artist and a sort of lay-preacher.

This view represented a departure from orthodox Catholicism, though during Bruegel’s lifetime it seems to have escaped direct persecution. Coornhert’s religious conception, as summarized by Grossmann, “centered on a personal relationship with God that dispensed with the outward ceremonies of the churches (Catholic, Lutheran, or Calvinist), [and] a moral philosophy concerned with man’s duty to overcome sin, to which he is driven by foolishness.”

This view differs drastically from the Lutheran or Calvinist conceptions of sin as inborn. It is not the view of approved Catholic theology, either. Yet it is the view basically illustrated by the Sin engravings, and underscored by the subjoined mottoes or morals in Flemish and Latin. Those statements again and again paraphrased or closely paralleled passages in Coornhert’s writings. Whether they were selected by Bruegel himself or by his publisher Cock, or even—which hardly seems likely—by the engraver van der Heyden, does not matter greatly. There is no ground to suppose that they were added in opposition to the wishes of Bruegel; and the finished prints purchased at Aux Quatres Vents combined their pictorial and verbal commentary in an integrated whole. These inscriptions are so close to Coornhert passages that Grossmann, in fact, is inclined to attribute their wording to Coornhert himself.

The Coornhert view of sin can be summarized more fully as follows:

Sin, though prevalent, is neither foreordained nor inescapable. It is a course of conduct contrary to nature—“a battle against nature, a delusion of the spirit.”

Punishment for sin was not deferred to a hell in an afterlife, Coornhert held, for “sin is the occasion of the ruination of men already in this life; it leads to misfortune and degradation, to spiritual and bodily decay.” Sin, in short, “spoils men” in the here and now. The lives of sinning men become, in effect, a hell on earth, since “sin exercises a dictatorship over miserable men as over slaves, for sin incessantly torments . . . with pains, with discontents, and with cares.”

The bondage of sin is underscored: The sinner is “a slave of sin, whose chain is the bad habit.” The addict of vice is thus its victim.

We seem in this exposition to be entering a realm of psychological understanding rather than of theological dogma. Flashes of similar insight may be found elsewhere during this era, and in following periods. It is perhaps strange to encounter a similar touch in that great and paradoxical mingler of the medieval and modern—the poet John Milton. A memorable line in his Paradise Lost speaks of “jealousy ... the injured lover’s hell” (Book V, 449). Milton would hardly have placed jealousy among the sins, mortal or venial; but he does here establish the equivalence between the impulse, or emotion, and its punishment.

Then, Robert Burns, in his “Epistle to a Young Friend”:

I waive the quantum of the sin,

The hazard of concealing:

But, och! it hardens a’ within,

And petrifies the feeling!

Bruegel’s Sins picture the compulsive vices, or follies, of men in a similar sense; they serve as their own punishments. They harden and they petrify the spirit of the sinner.

Thus the sinners who are hunted and harried, naked, through these engravings are bedevilled—but not by demons at whom one could, like Luther, hurl an inkpot. The monsters about them are the symbols of the heart-hardening and internal petrifaction engendered by the practice of sin in daily life. This is not a Hell with a geography and a location, like that of Dante or even that of Milton, but a hellish state of mind—a devil of a fix.

The vicious life is in itself hellish. The battle is joined, not so much for, as in, the souls of men themselves.

To convey this in pen and ink, Bruegel used means which were new with him, though the elements came from earlier artists. There is first the central allegorical figure, always a woman, representing the personification of the Sin. (Each of the Virtues, too, has a female figure as its personification; so no misogyny need be suspected.)

Around and behind this central personification, in a broad landscape, are ringed individuals and groups who illustrate what the vice does to those addicted to it. Monsters and bestial symbols guard and goad the human sinners. These demons are sometimes almost normal animals; but most are horrendous composites, anatomical impossibilities combining human, animal, fish, bird, and reptile elements in permutations of endless ingenuity.

Such use of the central allegorical figure corresponds to some extent to a primitive and persistent human tendency to personify when thinking about dangerous natural forces or compulsive patterns of conduct: “Alcohol has her in its grip!”; “I didn’t mean to, but Something simply made me.”; “Envy is making his life miserable.”; “Reason flies out the door when Anger enters . . .”; etc.

Bruegel’s treatment is related also to the traditional presentation of a deity and attendant devotees, such as Bacchus and his train of revelers, Satan and his company in a witches’ Sabbath or Walpurgisnacht, etc. The central figure embodies the influence; the devotees or addicts act out the consequences. The central One is a static symbol; the others the active embodiments. So it is with these Sin engravings.

Coornhert and the ideas he voiced were influenced by the humanistic revival. This is apparent in their sin concept which paralleled the ethical teachings of leading “pagan” philosophers. Ignorance is the essential root of wrongdoing. An enlightened man can break free of folly, which is in effect another name for sin itself.

Since sinful actions—or foolish conduct—bring their own punishment, a man who through enlightenment overcomes his folly will also avoid the suffering consequent upon it. To this extent, a virtuous life is its own reward. Virtue as its own reward is a pagan rather than a Christian concept.

Yet the pagan philosophers, in keeping with the social structure of their society, hardly conceived of such virtue and happiness for all men. The great mass had neither the capacity, the leisure, nor the inclination for the necessary enlightenment.

The early theologians of Christianity based their creed on a code of conduct divinely revealed to mortal beings—men—who had both freedom of choice and unconditional responsibility for the consequences of such choice. This was essentially a legal system: laws laid down for men (all men) to follow; judicial verdicts as to the observance or violation of those laws; punishments for violations, and rewards for observance. It was a complete system of enforcement through sanctions, and the penalties became effective in afterlife, when the soul had shuffled off the mortal body. Hence, they were eternal.

Coornhert, on the contrary, taught an ethic in which hope for human betterment was rooted in human reason and enlightenment. It was a break with the hierarchical, authoritarian, and legalistic concepts prevalent in medieval theology, and several steps closer to the attitude congenial to the majority of the educated in our own time.

There is a backward-looking aspect to Bruegel’s Sins also. In their diabolism, their choice of symbols, and their crowded compositions they derive from traditions going back to Bosch and far beyond. However, this was no complete going back. It was a use of old and even archaic elements to convey ideas which were, for their time, advanced, if not radical to the point of sheer heresy.

It is tempting to speculate to what extent Bruegel deliberately chose old bottles into which to pour the heady, effervescent new wine of these ideas of individual worth, freedom, and opportunity.

Why seven Sins? This number, by Bruegel’s time, was accepted and traditional. Mystical numerology had played a part here. It had worked during long centuries of brooding on sin, punishment, and the eternal afterlife.

The first influential listing of sins is found in the writings of the Church Father, Jerome—the same Jerome we have seen studying in the desert in Bruegel’s landscape at the start of this book. Jerome’s list differed from that which follows, both as to sins included and those excluded. For Jerome, and indeed during the Middle Ages, the Deadly Sins were usually conceived of as the antitheses of the Cardinal Virtues. Seven Sins: Seven Virtues—a tidy symmetry.

Eight sins were commonly identified at first, but numerology reduced the number to the mystically efficacious seven. Five specific sins appeared on most lists—Pride, Avarice, Anger, Gluttony, Unchastity (Lechery). The remainder of each list was made up of two among: Vainglory, Envy, Gloominess (Tristitia), and Sloth (Acedia). Tristitia was a sinful excess of depression; and Acedia was excessive languid indifference.

Historians of ethics have pointed out in such sins the effect of the monastic life, so highly esteemed during the Middle Ages. Traits as negative and damping in their results as acedia or tristitia were likely to be frowned on, especially in the close, restricted, and interdependent life of a monastic community.

Chaucer himself supplied an exhaustive and informative treatise on one selection of Seven Deadly Sins, complete with discussion of their intricate ramifications, inter-relationships, and remedies. This treatise is known as “The Parson’s Tale” in The Canterbury Tales, that unfinished symphony of social types and favorite fictions in an awakening England.

The “Tale” is, in fact, no tale at all, but a parody of typical sermonizing by such a moralizing preacher. The Parson, though riding toward a late fourteenth-century Canterbury, was mentally still journeying in the Middle Ages. He was an anachronism, even in his own era.

Accordingly, Chaucer made the Parson’s preachment windy and wordy: a thousand or more lines of particularly prosaic prose. Its tone is earnest, assertive, trite, dull, hair-splitting, saturated by second-hand scholasticism, and by ponderous distinctions void of true differences.

More than half the Parson’s wordage winds its way slowly through the Seven Sins. Pride was placed first in position and importance. Then, in order, came Envy, Wrath, Acedia (here undue despair rather than crude laziness), Avarice, and those unheavenly twins: Gluttony and Lechery.

Nowhere has the central position of the Seven Sins in conventional ecclesiastical thought of bygone centuries been more amply elaborated than in this, one of Chaucer’s most consummate “spoofs.”

He wrote more than a century and a half before Bruegel created this series of Sins. Obviously, then, the subject was not new. We may see in the following pages whether Bruegel succeeded in placing it in new light. . . .

The order of Bruegel’s Sins here is that which it seems the artist himself might well have preferred. It differs from the order of the same subjects in the Bastelaer catalog. We place first “Avarice,” which dates from 1556, the very year in which Bruegel began his design of satirical and moralizing subjects. Next comes “Pride,” followed by “Envy,” “Anger,” “Gluttony,” “Lechery,” and “Sloth”; these last six are all dated 1557. Alternative titles of the Sins are given in English, when it seems helpful; also corresponding titles are included in Latin, French, and German, in that order.

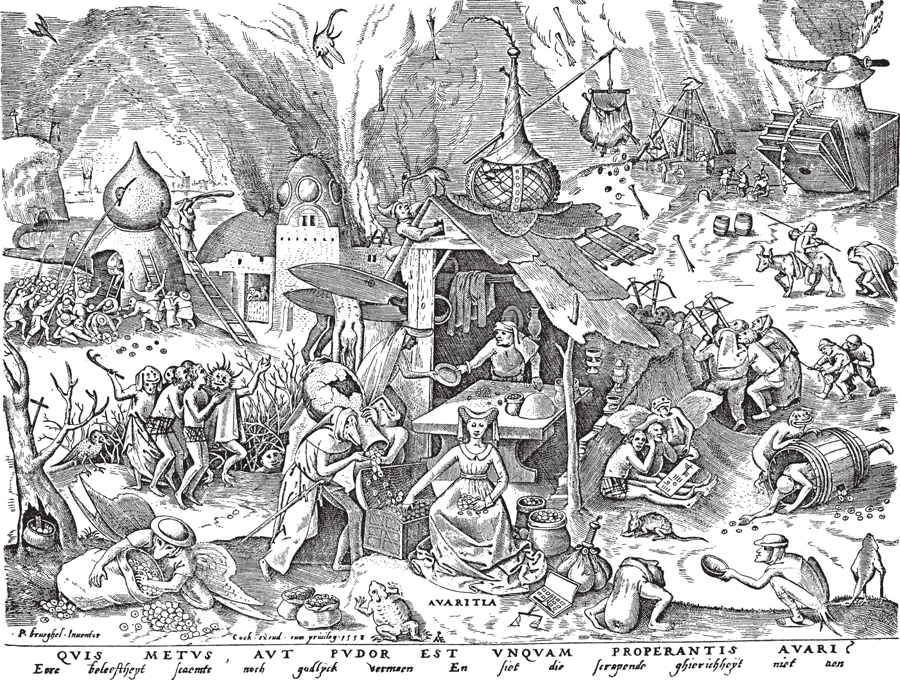

The original drawing, in the British Museum, bears the date 1556. Fritz Grossmann, in evaluating the Sins series, sees Avarice as the moral source of all other sins. Stridbeck, too, stresses the central position of avarice—greed for gold and gain—in the constellation of sins: “Avarice like Pride has a key position. . . . Avarice is the spur that drives men to evil deeds and is the direct occasion of a whole series of other sins and vices, such as betrayal, falsehood, discord, strife, animosity, aggressiveness, bellicosity, war, etc. . . . Avarice is an unquenchable desire which can never be satisfied . . . the avaricious person shuns no means and respects no restraints.”

An English proverb, deriving from the New Testament, says: “Money is the root of all evil.” The Latin motto below this print asks: “Does the greedy miser ever possess fear or shame?” The question is, quite obviously, rhetorical.

The Flemish motto, freely translated, asserts:

Grasping Avarice does not understand

Honor, decency, shame, or divine command.

The personification of Avarice is a seated lady guarding a lapful of money, while she reaches into a handy treasure chest which a lizard or crocodile demon fills from a huge broken jug. The eyes of Avarice seem to look down at her hoard of gold; but close study of the original drawing shows that it is possible, as Tolnay believes, that Bruegel meant to depict her as blind. In any case her attention is fixed on gold; she sees nothing of what goes on around her. She wears a crescent-shaped head covering, a shape symbolic of the profession of procuress, for Avarice violates honor and decency for the sake of money.

Near her feet crouches the toad, her animal counterpart. He was believed to betoken avarice because, according to Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, a toad is able to devour dirt and sand, so abundantly available, yet withholds eating for fear that he should not, after all, have enough.

A dozen different groups and actions compete for attention around the fantastic landscape. Behind Avarice is the hut of the moneylender. He takes in pawn the clothing and utensils of the poor. They are left naked, like the man clad only in visored cloak, handing over his plate. To the right of the hut sits a pair naked except for the crude “shorts” which some evil-minded censor scratched onto the reproduction! Before them is a large tally-sheet. It shows accumulated debts. A winged monster points to the reckoning. These men, in the words of the proverb, have “sold their souls to the devil,” and all for gold. In the original drawing, their faces express sharp despair and horror. In the engraving, van der Heyden—here, as so often—blunted Bruegel’s sharp point; their expressions are ambiguous.

Nearby, a naked miser loses coins as a grinning reptile monster rolls him in a barrel, spiked inside. Money spills from the barrel itself.

Victims of the moneylender are caught in the shears, like the one hanging beside his door. The shears symbolize cheating and fraud. Yet even the moneylender is a victim; he is being robbed, more openly. A thief has climbed the roof and reaches in to steal. The avaricious cannot retain what they have snatched in their greed.

The Orientally ornamented onion-like savings bank or pot on the roof holds a fish, very likely a shark, symbol of rapacious, insatiable greed. From the cone on top projects a stick, dangling a huge purse or money-pouch. Crossbowmen to the right use it as a target. Their arrows are tipped not with points but with money. The pouch has been pierced and the money falls out. As they shoot their money-arrows in an effort to get more, two smaller figures farther right are cutting away a purse. Greed preys on greed. Tolnay has traced several Flemish proverbs in the multiple symbolisms of this group.

In the farther background, same side, a man rides backward on an ox followed by a figure burdened under sheets or clothing.

Still further, a monstrous bellows fans a fire which sends smoke through a hat pierced by a saw-like sword. Tolnay finds this a symbol of fanning the passions into flame, and the men beating hammers alongside, he calls coiners of money.

In the right foreground, a bird-tailed beggar holds out his bowl toward a gruesome monster composed solely of a great face with legs. At the beggar’s rear a demon bird pecks, probably a reference to the common identification of insatiable greed and constipation.

At lower left a winged demon claws gold from a great bag, near a dead hollow tree—symbol of sterility and vanity—in which a pot of gold has been hidden. A cross projects from the dead wood, like an afterthought.

Above, several demons conduct a pair of naked and terrified sinners while one gesticulates toward the shears as if to point out what awaits. In a bramble thicket behind them, a victim is buried almost to his neck.

Behind this group an armed assault attacks another Flemish savings pot (piggy-bank equivalent). With a long pole an attacker is poking a coin out of the slot near the top. Another has climbed a ladder and is about to smash the pot. Below, some attackers already scramble to grab coins on the ground.

Nearby (to their right), an ornate castle with Oriental design elements is ablaze. Smoke pours from the domes which resemble great beehives. In the sky a fish-bird monster is plunging like a dive bomber. This is a first cousin of the monster flying in the print of “Big Fish Eat Little Fish,” reproduced as Plate 29.

In the farthest background great blazes destroy a city and forts. There is no safeguarding the wealth to get which the avaricious sacrifice honor, decency, sense of shame, and divine commands.

The original drawing, dated 1557, is in Paris, collection of Frits Lugt.

Pride personified is a haughty royal lady, in rich court dress, “looking down her nose” at the world, while she admires her image in the mirror. Tolnay points out that Pride’s garments were high fashion for Bruegel’s period, whereas the other allegorical figures in the Sins series were clad in styles identified with the early fifteenth century.

Fashion may play a further role here, for according to Barnouw the roofs of the fantastic buildings are “ludicrous contraptions apparently suggested by contemporary fashions in headgear” and “the surrounding architecture ... is a nightmarish satire on the conspicuous waste indulged in by the proud upon this earth.” (All that is missing apparently are a few luxury American motor cars with fancy tail-fins and an abundance of chrome trim.)

The animal counterpart at the side of Pride is, of course, the peacock flaunting ornate tail feathers.

The mirror worship of Pride is echoed and mocked in the foreground by the knightly monstrosity, all head, forelegs , and peacock-feathered fish-tail, who admires himself in a mirror held by a nun-mermaid. The padlock through his lips indicates enforced silence, and the nun’s gesture points to the big-mouthed braggart monsters at left. Their idiotic boasts deafen the human wearing a dunce-like cap. Barnouw suggests that the nun may be predicting that a similar padlock-punishment is in store for them, too. Tolnay calls the mirrored monster a “fool of fashion.”

Just back of him, a bird-monster contorts so as the better to admire its anus in a mirror. An arrow is deep in its back. Perhaps this implies that vanity dies hard.

Above is a gruesome group. Monsters in the garb of shepherd, nun, etc., escort a naked, terror-stricken girl. A winged demon bears a shield inscribed with the symbol of a pair of shears. Tolnay reads this as evidence that the girl has “fallen into the clutches of the bawds.” Barnouw suggests the group illustrates a proverb; “‘Where pride and luxury lead the way, shame and poverty bring up the rear.’”

In any case, human nakedness in these Sin fantasies of Bruegel is in itself an indication of sin. A naked figure may be read, per se, as a human being suffering the consequences of his particular vice.

Farthest right at this level, is the sin’s inevitable “house” or shop. Here is a busy “beautician’s” establishment of the 1550’s; a barbershop with trimmings. Outside, a woman gets a shampoo, administered by a wolfish demon who balances a pitcher on his head. (Acrobatics and contortions so often are interwoven with the idea of horrible punishment in these pictures!) Out of the window, a barber pours slops onto the head of the helpless customer. And up above the doorway, a naked sinner squats and voids into a pan, and so on down to a piece of music lying on the roof. (Barnouw calls this an enactment of the contemptuous expression “I shit on that,” indicating popular contempt for the vanities here catered to.) Nearby hangs a lute. Instrument and music were not alien to the barbershops of that age; they served to amuse customers waiting their turns. The roof, too, displays the barber’s license to cut hair and practice surgery, plus a mortar and pestle showing that he also dispenses drugs.

Strange structures, many with humanoid faces, are spread across the background. At top center is a strange ship-like structure which Tolnay calls a stove-pot. It is packed with nude victims, guarded by a demon whose spiked helmet completely covers his head. A tree grows through this cryptic ark. On its top we see again the recurrent symbol of the broken hollow egg in which humans huddle. This always indicates some sort of rottenness and degeneration. Below the tree is the monster-mouth to this baffling structure. It is formed of wing-like segments, and naked humans crouch to enter. It is a kind of Hell-mouth—perhaps the entrance to the ultimate, sinister sideshow in this Vanity Fair.

Just to the left, a tree grows through another ornate structure, decorated by mirrors. Smoke ascends from holes in the roof. Below is a rivulet on the banks of which sinners sit. One falls in backwards. Immersion in water in these Sin studies signifies involvement in some sort of vice or shame. A bear-like monster on a horse, his naked companion mounted behind, fords this stream of pride. Tolnay sees this as a reference to a proverb which declared: “Two proud people cannot stay long on the back of the same ass.”

In the far background of the stream, a sort of portcullis is being raised in the gate of the hat-topped castle. A crowd of naked sinners there are wading or being overwhelmed by the waters.

The hat on top is torn. Birds peer out through the opening. On top, a broken eggshell seethes and steams. There are suggestions of a church about this dungeon or fortress. Also suggestive of the church is the tiara-like hat of the owl-monster just below the “prow” of the ship-like “stove-pot” previously pointed out. The monster is devouring a naked victim. Its quadruple hat is as though made of stacked beehives. A mast projects, which is braced by ropes to the ground. Interpretation fails at this point, but one cannot doubt Bruegel knew well what he sought to symbolize here.

A saying warns that “Pride goes before a fall.” And so, in the background, two figures fall headlong into the lake to the right. They resemble frogs or tadpoles. One drops from the height of the cliffs beyond the lake. This is the Icarus motif again. On the shores, figures are gathered dimly, waiting to be rowed across, or perhaps to plunge in.

As published, this print had both Latin and Flemish inscriptions below the picture. The Latin means: Those who are proud do not love the gods, nor do the gods love those who are proud.

The Flemish, freely translated:

Almighty God detests the vice of Pride,

And God himself in Heaven by Pride is defied.

Clearly Bruegel symbolized here Pride in many forms, not merely the narrow sense of craving for personal admiration and prestige. There are plays here on the pride of excessive display, the pride of malicious gossip, the pride of overweening ambition, and many other aspects of the Sin.

Plate 41 is reproduced by permission of Mr. and Mrs. Jake Zeitlin, Los Angeles, California.

The original drawing, in the private collection of Baron R. von Hirsch, Basel, is dated 1557.

Envy, according to Coornhert’s constellation of sins, “is the eldest daughter of Pride.” Indeed, the insatiable self-love and desire for aggrandizement of Pride, as conceived by Bruegel, could not tolerate the success or honor or fame of another. Envy, the inevitable result, poisoned the mind of the proud self-seeker. The envious one “eats his heart out” with resentment.

That is literally what Dame Envy does here. One recalls, with a difference, the stark poem of Stephen Crane, “The Heart”:

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter—bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

“Because it is bitter

“And because it is my heart.”

The Flemish verse below the picture, freely rendered, declares:

Envy, endless death and sickness cruel, unpent

Is a self-devouring beast and merciless torment.

The Latin means: “Envy is a horrid monster, a most ferocious plague.”

Envy herself wears a headcovering of a style already outdated in Bruegel’s time. Beside her is her appropriate animal symbol—the turkey, emblematic of envy.

At her feet, two curs battle over a bone. Behind her a demon extends over her head a crown in a travesty of honor. To the right is another hollow tree, in whose unclean interior lurks a monster bearing a distaff. Peacock feathers are the tree’s only growth. To the left, a breasted monster with stag’s horns and wings lures a naked human woman with an apple, a symbol of discord and downfall since before the Christian era. The horns are the usual symbol of cuckoldry.

As Barnouw points out, “The most striking feature of this print is the display of footwear.” He quotes Dutch folk-sayings in which shoes serve as an index to social standing, similar to our “He lives on a luxurious footing.” There is the class distinction, too, between the man in boots and the man in mere shoes.

Hence the shop, to the right, is a shoeshop. The merchant, his face hidden, forces a shoe on a customer, held by a monster. Other victims wait, seeking to get on the best possible footing.

From the top of a broken money-pot, above, the legs of a giant flail the air. One leg, pierced by an arrow, wears a great boot with spurs; the other has only hose. The latter has been lassoed by an armed force below, and is being pulled down. (Possibly a play on envious conflict between social classes?)

A crossbowman aims his weapon through the hole in the pot.

At front, left, a sad old woman lives, not in a shoe, but in a basket while she seeks to sell shoes. A shoe sits on her head. No customers appear.

Still farther left, a monster with dragon head, wings, and forelegs is about to devour a shoe. An arrow is shot or thrust through its nostrils. Farther back, a contorting demon examines its anus.

A boat floats on the stream or moat beyond. It carries a cargo of strange monstrosities. A winged monkey perching on the gunwale evacuates into the stream. An original “hollow man” is in the prow, his agonized face framed in a boat on which rest a tray, napkin, and apple. From his empty torso project dry twigs, always in Bruegel the emblem of futility and folly. Birds perch on a bare branch and on a dismembered knee. Perhaps this man has eaten himself up with envy. A spooky demon raises a hand in greeting. Envy has done its dirty work.

Another boat, beyond, capsizes, dumping its sinful passengers into the waters of degradation.

Across a bridge over the stream marches a funeral procession of hooded monks. They head for the chapel whose bell tolls. At the near end of the bridge is another of Bruegel’s many house-faces. It has a sort of Hell-mouth through which multitudes can be seen guarded by a bird-beaked or crocodile-snouted demon. A tailed demon carries a nude human up the ladder toward this entrance. Smoke pours out, past the “upper lip,” toward the “eyes.” This is a strange sort of Hell with a built-in chapel.

The opposite end of the bridge runs into a watchtower or water fort. In the far distance, a tower appears to be in construction. Is this a structure rising because of envy or rivalry? In the farthest distance, a church burns; and again at the far right a tower is ablaze.

At the upper left, a figure like a scarecrow stands on a pole. A funnel is inverted over its head. Its snout is a bottle or flask from which projects a perch for a pair of birds. Its body resembles a beehive.

Many what’s and why’s must remain unanswered. Even the most ingenious interpretations leave much unexplained in this phantasmagoria. But clear enough is the indication of dissatisfaction with one’s social standing, of the desire to get into the shoes of men more favored, and of the self-consuming nature of the sin of Envy.

Plate 42 is reproduced by permission of Mr. and Mrs. Jake Zeitlin, Los Angeles, California.

The original drawing, in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, is dated 1557.

Central to this print is war, the ultimate form of anger. War was familiar to a Fleming like Bruegel. Like other observant Netherlanders, he must have known at close hand the realities of occupation, invasion, and resistance. For his land was ruled by a regime imposed from Spain, and disaffection was growing toward rebellion.

“Dame Anger,” the allegorical figure here, takes an unusually active part in the proceedings.

In full armor, a sword in one hand, a torch in the other, and an arrow embedded in her brain, she rushes out of her war tent followed by a shock troop of monsters.

Her attendant animal, the angry bear, attacks the leg of a fallen and bruised human victim.

Twin warriors, faceless again, wield a giant knife of the style that was cutting the great fish in “Big Fish Eat Little Fish.” The knife cuts into several terrorized naked victims at once. Their nakedness shows them to be sinners, the prey and playthings of Anger, the merciless tyrant.

Another, at the left, cowers in desperation awaiting the blow of the spiked club wielded by the armored monster with enormous mouth. (See the reference to congested or swollen mouth in the Flemish verse under the print, translated below.)

The “shed” here is a horrible barbecue. A human victim, spitted and bound, is being roasted over a fire of “anger” raging in a hollow tree. The snout-nosed chef bastes him as he turns on the spit.

Heat treatment is also administered to a couple stewing in the pot atop Anger’s war tent. And in the background at the left, a towered town blazes. Fire and fury are partners here.

The middle distance is dominated by a gigantic ugly female, knife in teeth, right arm in sling, left holding a flask (poison!). Her hat bears a thorn branch as ornament. She crouches over a barrel that contains a bar-room brawl. The daggers are out in a battle to the death. A herald blows a long trumpet of alarm.

The hollow tree behind the giantess contains a nest of dry twigs bearing an egg. In a sort of tree house farther left, a man tolls the tocsin, and a fish is hung by its own gills, as seen earlier in the “Big Fish Eat Little Fish” print.

Two waterfowl fight in the sky. Toward the top right, another winged fish-monster flies. Below, in a strange dry-land war, an attacking party tilts at a landlocked boat propped up on huge hogsheads. The boat bears the by now familiar symbol of the hollow and broken egg, or ball, with human figures inside.

Warfare rages also at the lower right. Demons seek to advance behind a wheeled shield from which projects a saw-toothed sword, a symbol several times seen in Bruegel prints. A monster who bites an arrow in his beak reaches around seeking to bring down with his pike another armored monster, with one clawed foot and one stump, who unsheathes his sword. The spiked tail trails forward between his legs.

The original drawing shows expressions on the faces of these two which this writer believes indicate that Bruegel meant to show they were playing at, or parodying, human war. Both are smiling slightly. This is a bit of byplay between demon and demon, rather than a demonic punishment of human sinners. A reptilian demon pokes his head out from under the war shield, and yelps, as if in encouragement. Perhaps he is involved like the wife in Mark Twain’s anecdote, who shouted, “Go it, husband! Go it, bear!”

Another deviation deserves mention. A white banner flies above the war shield. In the print it bears no emblem. Yet in the original drawing it clearly carries the emblem of the world and worldly power: the orb surmounted by cross.

Possibly this detail was deleted for fear of the authorities—that is to say, the Spanish rulers of the Netherlands. The drawing was made in 1557, some two years after the rule of the Netherlands had been transferred by Charles V of Spain to his son Philip II, who spent in the Netherlands the first four years of his reign. The historian, E. M. Hulme, summarizes the situation as follows: “Philip, unlike his father, was unmistakably a foreigner in this northern state. To the several causes of revolt ... at work before his accession to the throne, there was added another and more fundamental one—a deepening antipathy to the Spanish rule.” (Renaissance and Reformation, New York, 1921.)

In such a period of increasing tension and crack-down on expression, it is plausible to suppose that a canny publisher like Cock would prefer to omit an emblem which might seem to identify a devil with the secular authority, that is, the regime headed by Philip. Moreover, the stump-legged demon outside the shield, on the flag flying from his helmet, displays the key of St. Peter. This is clearly the symbol of Papal authority. Philip sought to maintain that authority and to stamp out opposition as “heresy.” The drawing, thus, implied a strange struggle between the secular and the Church authorities, both represented by demon warriors. This implication is absent from the print.

The Flemish verse supplied as a moral to the picture indicates that men in the grip of anger are unable to talk right, feel right, think right, or function right; for it says, in free translation:

Anger congests the mouth, poisons the mood,

Disrupts the spirit, blackens the blood.

Anger’s dominion over the angry is dreadful and ruthless. Instead of dynamic, self-assertive masters of the circumstances leading to their anger, they become impotent, beaten victims of a merciless master.

Translation of Latin caption: Anger swells the mouth and blackens the veins with blood.

The original drawing, dated 1557, is in Paris, collection of Frits Lugt.

Evils arising from excessive eating and drinking crowd this composition. The print itself and its Flemish rhymed “moral” make clear that Gluttony includes drunkenness as well as overeating, and that both lead to human degradation. Very freely rendered, the verse warns:

Shun drunkenness and gluttony

when you drink and when you feed;

For in excess a man forgets himself

and forgets his God, indeed.

The allegorical emblem of overindulgence is a fat woman, dressed like a Flemish burgher’s wife (not a “monk,” as Adriaan Barnouw stated). She gulps wine from a pitcher. A drinking cup, like that held by an attendant fat monster in cloak, would not allow her to guzzle fast enough. So the monster must impatiently wait for a “refill.”

Dame Gluttony squats on her symbolical beast—a sinister hog with ears and hind legs like a donkey. He too has gorged—on turnips and carrots. And on the overturned feeding tub next to him, the engraver has inscribed the credit to “brueghel” as designer.

Other guests cram their guts at the table with Dame Gluttony. Two naked fat humans swill wine, encouraged by monstrous drinking companions. The naked female’s belly is so big that she appears pregnant.

After-effects of such indulgence are expiated by another human; he vomits abundantly over the bridge (left) while a beaked demon holds his forehead. The vomit pours down, to the horror of another immersed in the stream below. For an old soak, this is a torment saturated with poetic justice.

In a dark corner under the bridge the upper part of a face projects above the polluted stream. An egg is balanced on the head. The egg appears again and again, either entire or empty and broken, always to symbolize sinful situations.

Another balancing feat is performed by the monster crawling and eating on the bank, just to the right: an enormous head, supported only by arms, a bowl and spoon balanced atop its hat.

At the extreme lower right corner lies the monstrous fish-eater, his stretched belly split and laced together. In Bruegel’s world, overeating often took the form of too much fish.

Near the fish-monster’s tail, a devil-dog jumps up to snatch food and drink from a tray on the back of a fat demon, dressed like a butcher.

Back of Dame Gluttony’s table is the inevitable ruinous shed or tent. It partly shelters a huge wine barrel. A fat man-monster uses pitcher and drinking cup to guzzle from its head-hole as fast as he can. His garments have monastic suggestions.

Above the tent rises the familiar dead sin-tree. A bagpipe is draped in its crotch. This too betokens gluttony; for its bag is a fat belly. A basket-cage hangs from a branch. Creatures, seemingly birds, are pent inside. Plucked chickens hang from the ridgepole.

A giant in human form is imprisoned on the left in a building from which his head emerges. His head is pierced by a shaft carrying spiked wheels. He is thus forced to look at the guzzling and feasting he now cannot share. Horror and desperation are on his face, especially in the original drawing.

At the upper right, a human head forms a monstrous windmill. One eye is a mullioned window with broken panes. This symbol, suggestive of some twentieth-century surrealism, appears elsewhere in Bruegel’s prints, notably in the “Temptation of St. Anthony.”

Bags of grain—or possibly sacked humans—are carried up a ladder to be ground in this man-mill. It never ceases its mechanical mastication. Atop the head perches a motionless owl, watching all.

On the banks of the stream of iniquity below appears one of the most horrible examples of compulsive eating: the man too fat to walk unaided; he must trundle his monstrous abdomen in a wheelbarrow. Other groups of men and monsters illustrate the theme alongside and in the stream.

At the right, and nearer, the legs of a man thresh vainly out of a wine barrel. He has been caught, seemingly for all time, in the symbol of his vice. Another sinner on his knees is supplicating to be spared such punishment. Comparison of these two naked figures in the print and in the original drawing shows that the engraver eliminated genital details from the original design.

Conflagrations, so common in the backgrounds of the Sins, rage here also. On the left side of the bank a fire heats a great stewpan into which men reach from a boat. Behind them and to the left of the man-mill, sinners are driven by demons into a sort of tower-oven to be cooked or smoked.

Translation of Latin caption: Drunkenness and overeating are to be shunned.

The original drawing, in the Royal Library, Brussels, is dated 1557.

“Sexual Excess” might be a more precise title than any of those in the four languages above. This sin, to Bruegel, like Gluttony, is an enslavement through overindulgence. The sin lies essentially in the physical excess. This is not, in other words, a pictorial polemic for celibacy or absolute chastity, any more than “Gluttony” was a preachment against ever eating or drinking.

The Flemish verse below the engraving, freely translated, declares:

Unchastity stinks; it is drenched with dirt;

It weakens men’s bodies and does them hurt.

More literally, it weakens a man’s fibres, and undermines his powers. It unmans a man.

This is symbolized with shocking sharpness by the face-muffled figure near lower right. He is caught in the act of self-castration. His right hand holds an amputated phallus; his left, a long knife, about to cut again. On one of his feet perches a demon bird. A garter or sling dangles from the ankle.

Lady Lechery herself is a naked woman being debauched by a throned monster. He tongues her open mouth and fondles her breast. One of her hands is around his shoulder, the other at her genitals. Demon beasts surround them in their dead hollow-tree “love nest.” One of the fiends waits to serve them from a flask—a love-philtre or aphrodisiac.

Behind the throne, a composite animal-human lies on its back, a huge tail projecting phallus-like between its legs. Atop the throne sits the cock, symbol of insatiable lechery.

Directly below we see one of Bruegel’s most indelible nightmare conceptions: an open-mouthed head with upraised arms. It is at the same time, and unmistakably, buttocks, vaginal opening, and legs. This animated obscenity spills over its hair the contents of a great egg through which a knife is thrust. (The egg then, like the oyster today, was regarded as an aphrodisiac or provender for potency.)

Just above, a pair of winged monsters copulate like cats. At the far right, two dogs couple, while a monster raises a club, about to strike them down in the very act.

The hollow tree itself takes the form of an antlered stag. (Possibly a play on the concept of cuckoldry?) In the stag’s mouth is an apple; other apples are on branches. (The apple of original sin, perhaps?) At the treetop is a strange love-bower. Its counterpart will be found in paintings by Bosch. A partly opened monster mussel or oyster grasps a bubble or glass sphere; inside, a naked human couple embrace. Barnouw suggests that this means the delights of love “are as futile and transitory as the colors of a soap bubble.”

A monkey—another beast associated with unending lechery—lowers a lamp or container from near the hinge of the giant bivalve.

To the left of the tree marches a horrible procession, headed by a monk playing the bagpipe (here, as so often, the symbol of sinful indulgence). A naked human is being ridden on a horselike monster. He is an adulterer, as revealed by the writing fastened to his hat. He is being publicly punished, as adulterers sometimes were in Flemish villages. In the procession behind him march a naked man and woman, probably also guilty of illicit intercourse.

Near the lower left corner, an animal demon points out the spectacle to a human sinner seated beside him.

Examination of the original drawing shows a significant change or censorship in the engraving. The adulterer in the drawing wears what is unmistakably a bishop’s mitre. In the engraving this has become a noncommittal and nonecclesiastical hat. Probably even in 1557, before the full fury of the Inquisition struck the Netherlands, it was unsafe thus to link the hierarchy with adultery and public punishment.

A meandering stream flows through the middle ground from the left background. It is a stream of sin, flowing past the fountain of lechery and pleasure bowers where clandestine couples meet and indulge their lusts. A naked woman wades in the stream, immersed in water above her genitals.

The stream has come from a mill. In the water near its turning wheel a couple stand with upraised arms. The mill itself in the engraving shows another alteration from the original drawing, in which the mill roof was made to form a face along the right edge where a trapdoor seems to be opened. This anthropomorphic detail was missed by accident or omitted on purpose.

A snake-tailed bird-monster hovers in the sky. On the skyline we see the expected fishing boat and the traces of a fire far down the horizon.

To the right of the hollow tree stand a castle and some humanoid structures. In one, a ravenous shark or pike (of lust?) has leaped up from the moat and crushes one of a number of horror-stricken sinners.

Near the lower left corner, scatology and lechery combine: a human squats to void his bowels, aided by the beak of a demon-bird. Above them a monkey-monster rolls on its back, lewdly flaunting anus and genitals.

A grinning monster at the lower right wears the characteristic crescent-shaped headdress regarded in Bruegel’s day as the sign of the procuress or female pander. A similar headgear is visible on a figure seated near the fountain of lechery.

Beasts scattered throughout this lecher-land—peacocks, swans, sheep, dogs, monkeys, etc.—are all associated in Flemish folklore with lechery. The symbolic “language of beasts”—as developed in its day as the “language of flowers”—assigned, for example, to the swan the idea of Vanity. This vice was linked closely with lewdness and whoredom. And so on.

Stridbeck points out that this “Lechery” engraving contains, relatively, fewer hellish or infernal elements than others in the Sins series. In fact, some of the infernal “props” have been replaced by the pleasure dome, the garden of fleshy delights, the meadows of fornication and the fountain of lechery, etc.

But even here—near the upper right corner—sinners are stewing on the hot seat. As they are devoured in life by the fires of their uncontrolled lusts, so here in the symbolic world of their moral degradation they seethe and suffer in an unquenchable blaze.

Translation of Latin caption: Lust enervates the strength and weakens the limbs.

The original drawing, in the Albertina, Vienna, is dated 1557.

Many a modern must find this not only the most passive and negative but in many ways the most haunting and shattering of Bruegel’s seven Sins.

It symbolizes the evils of the vice which was treated with more irony and folksy fantasy in “The Land of Cockaigne,” reproduced as Plate 32. In that print, Plenty has destroyed ambition, energy, activity. Here, Sloth herself, older and uglier than the other allegories, sleeps open-mouthed in a landscape of delay, decay, and ultimate impotence.

She reposes on her beastly counterpart, a sleeping ass. A monster behind her adjusts her pillow. Around her crawl huge snails. Even the hill of Sloth is soft as shown by a winged demon sawing into it at left. One art historian sees the saw as a suggestion of Dame Sloth’s snoring as she sleeps. Another regards the sawman as a symbol for malicious gossip, his mouth ever open as he cuts away the ground from under others.

From the right, a stork-beaked monster in monk’s garb drags a sinner too indolent to leave his bed; he eats as he lies. The counterpart of this monk, Tolnay finds in Bosch’s “Temptation of St. Anthony” painting (Lisbon). At the lower left, on a nearer hillock, crawls an all-head-and-feet monster, dragging a tail half fish, half branch. A hollow tree, farther left, contains a great pig’s head and provides a perch for a demon bird.

The hollow-tree symbol is extended enormously to the right of Dame Sloth. In this shell-like structure mingling building and tree, naked sinners and monsters sleep around a table. A couple lie together in bed behind a curtain. The demon leers around it as he seeks to draw the sleeping girl inside. Sloth or excess leisure encourages lechery. An owl, again, looks down cryptically.

Dice on the table to the left of the owl refer perhaps to gambling by lazy time-wasters. A man, caught in a great clockwork above, strikes a bell with a hammer. Tolnay reads this as a kind of pun, for in the Flemish lui signified both the verb “to ring” (as a bell), and the adjective “lazy.”

The idea of clock and time a-wasting appears again at the upper left. Like some effect in a Jean Cocteau motion picture, a human arm points to 11 o’clock. The lazy leave things till the eleventh hour.

And catastrophe lies behind—a blaze is burning up the broken structure, filled with dead branches.

A little to the right, just below the top margin, a mountain top with human face spouts smoke. A little farther to the right an enormous slug raises its feelers into the sky as it crawls through a stone arch. On its neck rides an almost unreadable strange distortion: a monster with a shaft (candle?) instead of a head.

Below, just above center, a squatting giant, built into a mill, enacts a proverb common to many a culture: “He’s too lazy to shit.” The faceless midgets in the boat behind him are inducing a bowel movement with poles and pressure. Another owl looks through a small square window in the roof above this operation.

On the bank, somewhat to the left, two demons drag into the water of sin a woman almost hidden inside a seething hollow egg, which looks also like a beet or turnip.

References to many other Flemish proverbs have been shown or suspected.

Basic to the complicated spectacle as a whole is the thought in the Flemish rhyme below the print. It is roughly rendered in English thus:

Sloth weakens men, until at length,

Their fibres dried, they lack all strength.

In short, sloth, far from resting, recuperating and rejuvenating, wastes a man away, renders him impotent and good for nothing. He becomes like a slug, a slave of the stupefied tyrant, Dame Desidia.

Translation of Latin caption: Sloth breaks strength, long idleness ruins the sinews.

Plate 46 is reproduced by permission of Mr. and Mrs. Jake Zeitlin, Los Angeles, California.