A single comment will introduce this final double section, each half comprising five reproductions.

The division into sub-sections here is a matter of distinction between literary sources rather than one of basic importance. Bruegel himself and most of his contemporaries hardly would have made much of such a distinction; for sacred stories from apocryphal and legendary sources, provided that they had general currency, were accorded esteem virtually on a par with that given to the canonical scriptures themselves.

Deeply concerned as he was with the human condition, Bruegel sought and found sacred material to meet his emotional and ethical needs without drawing fine distinctions between what was canonical and what apocryphal. The “Age of Reason” still lay long in the future, and “higher criticism” of Biblical sources had barely begun. Thus his treatment of the apocryphal miraculous death of Mary, mother of Jesus, is no less tender, reverent, and luminous than his treatment of the gospel incident of “Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery.”

With Bruegel, as with many an artist before him, material from the widely-disseminated Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine provided impetus for drawings and paintings certain to appeal to a wide audience. As a source, the Golden Legend ranked close to the Good Book itself.

The ten engravings in this double section may be grouped in another way, which affords a different kind of comparison. Thus we might consider all those in which the infernal and fantastic elements invade the domain of the sacred and saintly central figures or vice versa. This group would include “The Descent into Limbo,” “St. James and the Magician Hermogenes,” with its companion piece, “The Fall of the Magician,” and “The Last Judgment.” The remaining group, devoid of demons, includes: “The Death of the Virgin,” “Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery,” “The Resurrection,” “Jesus and the Disciples on the Road to Emmaus,” and “The Parable of the Good Shepherd.”

The first three of the second group can be considered a distinct as well as distinctive subgroup. Those three engravings are all based on monochrome black-and-white—“grisaille”—paintings or wash drawings, rather than on pen and ink drawings designed with a deliberate view to subsequent engraving on copper plates. The grisaille originals, marked by their mastery of light and shadow, are among the noblest, most sensitive and appealing of all the works of Bruegel. Philippe Galle, the engraver, who executed “The Death of the Virgin” and probably also “The Resurrection,” unfolded a remarkable technical skill, in keeping with the requirements of the subject matter. Perret, who engraved the third, was not far behind.

Perhaps the most important insight for all that follows is the fact pointed out by Adriaan Barnouw: “It is clear from these engravings that Brueghel knew the scriptures intimately.”

This knowledge and absorbed interest is exemplified also in his paintings, among which many of the greatest are directly drawn from Biblical subjects.

Thus we find from Old Testament sources the painting known as “The Suicide of Saul” (1562) and the two versions of “The Tower of Babel” (one assigned to the year 1563, the other perhaps a decade earlier).

From New Testament sources a far larger number remain to us: no fewer than ten, including such extraordinary and haunting works as “The Sermon of St. John the Baptist” (1566); two versions of “The Adoration of the Kings”—one from 1564, and a 1567 work in which surrounding snow is an important element; as well as several works in which Bruegel combined his Biblical interpretation with noteworthy approaches to a problem that deeply fascinated him: the representation of large numbers of people in motion. One such is known variously as “Jesus Carrying the Cross,” or “The Procession to Calvary” (1564). Another is “The Conversion of St. Paul on the Road to Damascus” (1567).

Biblical and sacred figures are introduced, as we have seen, to serve as subordinate elements in some Bruegel landscape compositions. Thus we have seen Mary Magdalene repenting, St. Jerome studying in the desert, etc.

Further, in compositions whose subject is not specifically scriptural—such as “The Temptation of St. Anthony,” reproduced as Plate 59—we encounter implications and allusions which can be solved satisfactorily only in the light of Biblical quotations. A full reading of Bruegel’s many meanings can hardly be attained today, and even a fair approach to such reading requires considerable familiarity with proverbs prevalent in Bruegel’s day and with the Scriptures, which formed so basic a part of the cultural background of artist and audience alike.

Doubtless, among Bruegel’s lost drawings and paintings were many other Biblical subjects. Even on the basis of the work that has survived these 400 years, it can be said that among great Netherlands artists, the two most deeply devoted to the Bible were Bruegel—and that later genius, Rembrandt.

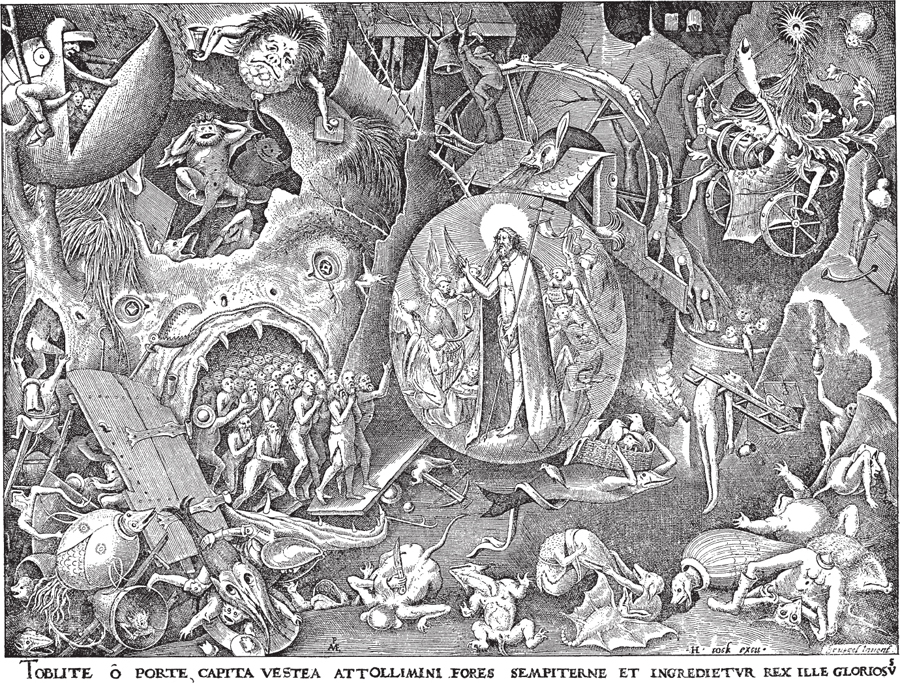

The original drawing, in the Albertina, Vienna, is dated 1561 by a hand not Bruegel’s. The engraving, by van der Heyden, was published by Jerome Cock soon after 1561.

Bruegel’s infernal fantasies are memorable in this engraving. There are significant similarities to the series of Sins. However, if those were set in psychological hells, this one is situated in Hell itself—or at least in its entry-way and anteroom.

The literary background is quite definite. In Bruegel’s time it was also well known and commonly read. The action comes from an apocryphal work known sometimes as The Gospel of Nicodemus, sometimes as The Acts of Pontius Pilate. Somehow, to that work, which may stem from as late as the fourth century, a second part from about the second century came to be attached; it is this part, known sometimes as “The Descent into Hell,” or again as “The Harrowing of Hell,” that provides the present melodrama.

The story is that of Jesus, after the resurrection, going down into Hell itself for the predetermined purpose of liberating and removing the patriarchs of old. These were the saints and holy men of the Old Testament, obviously undeserving of an eternal lingering in darkness and discomfort, or worse, simply because they were born on earth too soon.

In Bruegel’s conception here, Jesus enters Hell as the divine and invincible liberator. His power and glory are symbolized as he hovers inside a great bubble or cell of radiance, insulated from the foul infernal horrors. With him are nine angelic musicians, performing praises and exultations; one sings from music, the rest are instrumentalists.

Jesus is tall, majestic, supernaturally elongated. Yet despite his triumphant divinity he is still the newly risen or newly descended crucified one who had been laid in the tomb. He wears only a loincloth and cloak. His feet are unshod. Nail holes mark his foot and hands. His body is marred and gashed.

At the left, the saints and patriarchs pour out of gaping Hell-mouth, their arms extended in hosannahs and thanks. The everlasting gates have been literally lifted up and flung aside. They are unhinged. One of the gates serves, in fact, as a kind of platform or gangplank permitting the liberated patriarchs to walk safely over the sharp teeth projecting from the lower jaw of the Hell-monster.

Hell-head itself resembles to some degree an awful fish, but its eyebrow and tonsure also suggest a monk. At the right, between the Hell-head and the divine bubble, a strange curved dividing wall has been partly torn away in the upheaval. A great hole gapes in the forehead of Hell itself. Inside, on a floating plate or shield, sits “Satan the prince.” In fear or rage he clutches at his crown. His hind legs have hands, and his tail mingles male and female genital suggestions. Around him in the darkness several monsters grin and grimace.

Above, on the tonsured dome of Hell-head, crawls a loathsome horror, all head and arms. One hand holds a wineglass, the other a piece of fruit. Tolnay identifies this creature as Lewdness, as indicated by the revolting pustules on the chin and the bestial self-indulgence of the features.

The stinking pit or floor of Hell is the foreground. In this arena, foul monsters and perversions writhe and gyrate. Among them are delirious nightmares of ill-assorted anatomy, merging organs of beasts, birds, and fish. In rage and frenzy they snarl and snap. A giant mussel or clam has clamped about the head of a knight-like figure in armor, just under Hell-mouth.

Almost in the center, a semi-human tailed creature has stabbed a knife through his own back. A strip of flesh clasps his wrist.

This Hell has inmates other than the patriarchs and saints whose liberation is under way. Sinners ineligible for this release continue, and will continue, to suffer. Back of the divine bubble we see a great wheel turning. Long spikes on its rim pierce the bodies of helpless sinners. The wheel turns endlessly, carrying them to a chute at right, which tumbles them into the seething caldron. There we see cooking a dozen or more sinners, with suggestions of more in the murk behind. Below them smokes the fire. Most likely to their scalding torture is added the torment of knowing that not now or ever will be for them the divine release which the patriarchs are about to enjoy.

In an enormous pot behind the wheel lurks a gigantic “peeping Tom,” too dim to be seen clearly. Tolnay declares that Bruegel placed him here to serve as “a spectator who robs the proportions of the foreground scenes of their reality and degrades them to a dwarfish puppet play.” This interpretation, however, seems unconvincing. Bruegel does not appear to downgrade or minimize the merit of the patriarchs and prophets pouring from Hell.

At upper right, an ornate knightly helmet—often a symbol of sin or corruption—is combined with metal wheels. It forms a peculiar infernal velocipede—or a veloci-hand, for it is turned by hand rather than foot power. Inside the helmet is a demon; he has pierced a fish with an upraised sword. He makes as if to strike—but vainly—at the King of Glory.

Over the sacred cell projects a small roof. A fishy monstrosity draped over it blows his fiery breath against the divine bubble. It has no effect. Below and to the right of the bubble, a fish monster glides along in the foetid atmosphere, its arms clutching a basket of birds on its back. A maternal monster seeks a new refuge for her little ones.

Just right of this refugee group, a broken sinner hangs helpless through a projecting ladder. A reptile demon emerges from a trapdoor and yanks at his hair.

In the upper left corner, supported and pierced at once by a hollow tree, is another of the egg-like structures which serve to symbolize sin or to imprison sinners. It appears here as a kind of tree-top trap. It is partly split open and a demon’s arms are clutching the edges as if trying to pull them together before the inmates can escape. From the left of this awful “egg” projects a strange leg, in a direction which proves it cannot be part of the demon’s anatomy. And finally, if this picture is turned so that the present left side of the egg becomes the top, the structure is revealed as a great helmet with projecting, spiked chin guard. Helmets of this kind were fairly common in Bruegel’s day. Furthermore, this helmet is also a monstrous face with round staring eyes and ghastly grin.

The Latin quotation inscribed below is from Psalms, 24: 7: “Lift up your heads, O ye gates; and be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come in.”

The original grisaille oil painting, now in Upton House (National Trust), Banbury, England, is assigned approximately to the year 1564. The engraving is by Philippe Galle.

The painting, in the monochrome black-and-white which Bruegel preferred for his most personal expressions, is believed by Grossmann and others to have been done for the artist’s friend, the eminent geographer Abraham Ortelius. Presumably it was presented about 1564; and ten years later, five years after Bruegel’s death, Ortelius had it engraved by Galle for presentation to other friends.

The names of Bruegel and Galle appear in the decorative panel at lower left; that of Ortelius at the right. A dozen lines of Latin poetry are inscribed between.

The original grisaille paintings of both this picture and “The Resurrection” show, according to Ebria Feinblatt, “effects of light and dark all but unique” in the body of Bruegel’s work. No treatise on abstruse niceties of “chiaroscuro” is required to draw attention here to the remarkable handling of illumination. The best of Rembrandt may be referred to for parallels.

The main source of light appears to be the figure of the dying Mary herself, rather than the taper she holds. Other and lesser light sources are the two candles over the door at rear center, the fire on the hearth before which a cat sleeps, and a small lamp that stands amid dishes and utensils on the table at front center.

The scene here does not derive from the New Testament, but from an apocryphal book, sometimes known as “The Discourse of St. John the Divine Concerning the Falling Asleep of the Holy Mother of God.” (An English translation from the original Greek is given in M. R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament.)

The story probably reached Bruegel in a re-telling contained in one of the most popular works of the fourteenth, fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries—The Golden Legend or Legenda Aurea of Jacobus de Voragine. This thirteenth-century assemblage of legends and lives of the saints and sacred figures has been called “an encyclopedic volume” which deals “in attractive style with the saints of all times and places—their deeds, sufferings, and miracles.” (For its story of the death of Mary, done into English, see F. S. Ellis’s edition of The Golden Legend, or Lives of the Saints as Englished by William Caxton, London, 1900, Vol. IV, p. 324 ff.)

St. John, teller of the story, is shown in the engraving seated, apparently asleep, at lower left. The miraculous assemblage of disciples and saints around the bed is seen by him in a dream, or trance.

Identification of individual figures around the bed is not essential for appreciation of the engraving; however, among those mentioned in the apocryphal work are “Peter from Rome, Thomas out of the inmost Indies, James from Jerusalem.” Also: “Andrew the brother of Peter, and Philip, Luke and Simon the Canaanite, and Thaddaeus, who had fallen asleep [had died], were raised up by the Holy Ghost.”

Also, “Mark, who was yet alive, came . . . from Alexandria with the rest.”

During a rather lengthy narrative, various arrivals tell how they came miraculously to be brought to Mary’s bedside. One example is the testimony of Bartholomew: “I was preaching in the country of Thebes, and lo, the Holy Ghost said to me, ‘The mother of thy Lord maketh her departure: go therefore to salute her at Bethlehem.’ And lo, a cloud of light caught me up and brought me.”

The “cloud of light” is several times mentioned. Light, in fact, is emphasized again and again. Thus Mary says to the apostles around her: “Cast on incense, for Christ cometh with a host of angels.”

And as the miraculous company prayed, “there appeared innumerable multitudes of angels, and the Lord [Jesus] riding upon the Cherubim in great power. And lo, an appearance of light going before him and lighting upon the holy virgin because of the coming of her only-begotten Son.”

Ultimately the apostles take up the bed and bear it to Gethsemane. Various miracles take place en route; and in some versions of the apocryphal story a paragraph is included stating that as the apostles “went forth from the city of Jerusalem bearing the bed, suddenly twelve clouds of light caught them up, together with the body of our lady, and translated them into paradise.”

“The Assumption” is described in quite different ways in various other Greek, Latin, and Syrian versions. Doubtless the “golden” touch of the pen of the author of the Golden Legend did much to soften for subsequent centuries, even for the time of Bruegel himself, some of the crudities and contradictions.

Nearly forty figures are gathered about the bed of the dying Mary in this memorable engraving. Their faces express deep tenderness and concern. The furnishings of the room, as well as the garments of Mary and the woman who adjusts her pillow, are typical of Bruegel’s own time and clime. We are, in fact, within a dignified and comfortable Flemish chamber. A curtained canopy shelters the bed. The ceiling is beamed. Panelling and wood carving enrich the interior.

Over the fireplace stands a religious image—a sword-bearing saint or archangel. The chair in the foreground and the nearby table have triangular or tripod leg supports.

A man in monastic garb kneels by the bed at lower right. His left hand holds a bell, and his robe is caught up by a cord from which hangs what seems to be a part of a rosary.

A work such as this dates no more than do human tenderness, human grief, or human hopes. Faith, not historical fidelity, is here in focus.

Translation of Latin caption: Virgin, when you sought the secure realms of your son, what great joys filled your breast! What had been sweeter to you than to migrate from the prison of the earth to the lofty temples of the longed-for heavens? And when you left the holy band whose support you had been, what sadness sprang up in you; how sad and also how joyful as they watched you going was that pious group of yours and your son’s! What pleased them more than for you to reign, what was so sad as to do without your face? This picture painted by an artful hand shows the happy bearing of sadness on the faces of the just.

Plate 56 is reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City (Dick Fund).

This was published by Cock, with the date 1565 at the lower right. The engraver appears to have been Pieter van der Heyden; he certainly engraved the “sequel” print which follows.

Again the legend illustrated comes from—or through—The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine.

The St. James shown here is traceable to one of the Apostles—James, son of Zebedee. This James has been identified as the elder brother of the apostle John. His designation as “St. James of Compostella” arose because his body, following his martyrdom, supposedly reached Santiago (in the Spanish province of Galicia). There was built the pilgrims’ shrine known throughout the Catholic world as the shrine of St. James of Compostella. It has been called “the most favoured devotional resort “of the Middle Ages. By the twelfth century it was held in such high esteem that a pilgrimage there was looked upon as no less efficacious than a pilgrimage to Jerusalem or Rome itself.

St. James and Spain seem to have been associated first by a work in which the late seventh-century writer Aldhem tells of James’ preaching in that country. About 200 years later appeared an account by Notker Balbulus of the transfer of the relics of James to Spain. Devout Catholics in that land were convinced of the authenticity of the story, and their conviction gained credence far outside Spain itself.

This James—also known as James “the Greater” to distinguish him from that other apostle, James “the Less”—was important enough to be mentioned in a bull issued by Pope Leo XIII in 1884, declaring that the remains interred at Compostella were authentic. (Scholars today, other than some Spanish Catholics, seriously question, when they do not positively deny, such authenticity.)

St. James traditionally was depicted as a pilgrim, just as he is here, where Bruegel has given him the garb worn by the pilgrims who flocked to his Compostella shrine: the cape, the staff, the wrist-fastened water bottle (just below his extended right hand), and the case hung from the girdle. In fact the legend asserted that Jesus himself had presented James with the long staff. The shape of the hat, too, was traditional.

The event here shown supposedly took place in Judea where James had gone to preach the gospel of Jesus. According to the legend, the Pharisees among the Jews there sought to refute or discredit him by enlisting the aid of Hermogenes, a magician. Magic and witchcraft thus opposed the saint’s miraculous powers.

Hermogenes sent his apprentice magician, Philetus, to expose James as a fraud, but Philetus himself became converted. Then Hermogenes summoned his demons to seize James and bring him and Philetus, both in shackles, before him.

The demons, however, when they came to James could only cry out for mercy, for, as they said, “Have pity on us! Behold, we burn before our time!”

James invoked divine aid to release the demons. On his instructions they fetched Hermogenes (instead of James and Philetus) and brought him bound before James, asking that James put their former master in their power so they might take revenge for the insults to James and their own “burnings.”

James asked why they did not seize Philetus, and the demons answered that they were unable to touch “so much as an ant which is in your chamber.”

James rejected the idea of vengeance, saying to Philetus, “Let us follow the example of Christ who taught that we should return good for evil.” Philetus, whom Hermogenes had bound, was given the privilege of freeing his former master.

Hermogenes then went to fetch his books on magic and brought them for burning to James, who ordered him to throw them into the sea instead. Finally, the ex-magician prostrated himself before the Apostle, saying, “Receive as a penitent him whom you have succored, even when he envied and slandered you.”

Thus the tale in The Golden Legend exemplified the golden virtue of forgiveness. And Barnouw in his The Fantasy of Pieter Brueghel stressed this as the element which must have appealed particularly to Bruegel.

However, closer study of the print reveals a different story. This is not a parallel to the magnanimous statement of another magician, Prospero of Shakespeare’s Tempest, who, in abjuring finally his black arts, said, “Forgiveness is the word to all.” The picture here is rather prelude to punishments, brazen and brutal, inflicted on the magician, as the following engraving will show.

The scene here is, in fact, the magician’s studio of surreptitious sorcery. James has been brought by magic before the magician, not vice versa. The Latin caption declares: “Saint James by devilish arts is placed before the magician.”

Hermogenes, surrounded by his monsters and misshapen devils, sits at left, hunched over the book of spells which, presumably, has helped him bring in the Saint. The Saint, however, shows no fear, even amid all this black-magic vileness and viciousness. Of the two, Hermogenes appears the more uneasy. Perhaps he even then senses what is soon to follow. . . .

Meanwhile, all Hell has broken loose in the chamber. The cast of an entire Walpurgisnacht or Night on Bald Mountain is swarming and milling about the place. Naked witches dangle their breasts as they fly astride dragons and a billy goat above. A real Hallowe’en broomstick witch is flying up the chimney at the right (or possibly she is coming down). Another is at the peak of the chimney hood, top right.

A diabolical toad seeks to outstare a cat on the hearth. A hole has broken through into the room’s subconscious—the cellar below. Sinister monsters huddle there.

The sun-faced horror with upraised arms just behind Hermogenes is the twin of Satan the prince, as seen in Plate 55 in the “Descent into Limbo” print.

Such is the nature of this fantastic confrontation between saint and sorcerer. It is significant that most spectators today undoubtedly find the demonic sideshow much more interesting than the quiet strength of the Saint. Perhaps Bruegel’s audience did too.

The original drawing, in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, is signed “Bruegel” and dated MDXLIIII, an error for MDLXIIII (1564). The engraving by van der Heyden dates from the following year, 1565.

Here is the sequel to the previous scene.

The reversal has taken place, as indicated by the Latin caption: “God granted the Saint’s prayer that the magician should be torn apart by the demons.”

His fall is in full swing now. Recognizably the same as in the previous engraving are the magician and his chair, now topsy-turvy. The Saint, too, is essentially the same: hat, halo, staff, hand gesture, and general posture.

Differences are obvious among the demons, some of whom take part in the gruesome “come-downance” administered to their erstwhile dictator. The remainder are, as it were, otherwise occupied. Comparing this “after” with the “before” picture, one may feel the demons to be protean, transient, melting incessantly from one horrible guise to another.

Yet the ensemble suggests the presence of an underlying new idea. So it has seemed to at least two of the most thoughtful and resourceful of previous Bruegel commentators. Though their proposed interpretations differ, both discern here more than just an illustration for an old legend, folktale, or sacred melodrama in the enduring tradition of “the good guy licks the bad guy.”

(1) Adriaan Barnouw finds it to be an allegory for the idea that “The make believe kermis scene of Vanity Fair, this world of human folly, will be overthrown by its own vices, which are but agents of God’s will.”

(2) Tolnay, on the other hand, finds this to be “a satire on the abuses of the Inquisition” and a hidden argument for Bruegel’s own “religious-universalist theism which stands above the battle of the sects.”

In support of the latter interpretation, we note the ecclesiastics looking on approvingly from the door behind St. James at right. Tolnay calls them “blind figures, outwardly holy, . . . who witness the murder of their fellow man with solemn seriousness, as if they were seeing a holy act.”

Hermogenes, falling upside down here, is quite certainly being “done in.” It is obviously the end for him. Tolnay believes that in this picture the demons are merely unthinking instruments of the Saint, who commands them to wreak vengeance against the heretic (the role here represented by Hermogenes, while St. James is an Inquisitor).

As a precaution, Tolnay suggests, Bruegel disguised the event as a theatrical scene. (Hence the jugglers, performers, acrobats, and carnival characters, especially at the left, and the sideshow announcement hanging like a flag from the back wall, left of center.)

It may be noted that dimly through the window, just to the left of that flagstaff, appear several faces of typical Flemish townspeople looking on, as if in amusement.

On the table at the lower left a headless body lies; the severed head is on the plate. Is this only a conjurer’s trick? Just below, more mutilation—a balloon-like monster has thrust a knife through one hand and a peg through its tongue.

The gigantic staring figure at the table to the left is perhaps playing the old carnival shell game—with three balls and three cups. She (?) balances the egg of folly or sin atop her (?) head. The tail of a diving reptile monster extends in front of one nostril. More self-mutilation appears in the monkey-like monster just to her (?) left.

The show in progress here is surely one which, in Barnouw’s words, “caters to the evil appetites of man and unchains in him the demons by which he is possessed.” That would be true also were the veiled theme a satire on the excesses of the Inquisition, which was at that time working up to its later rigors and terrors.

For an almost contemporary statement of the anti-Inquisition viewpoint which he finds here, Tolnay quotes from a Coornhert work dated 1579: “The word ‘heresy’ is nowhere found in the Holy Scriptures. Christ had severe words against the Pharisees, but does he demand their death? He does not desire the death of the sinner but the death of the sin. He says to his apostles that they will have persecutions to endure. He does not say that they are to be persecutors.”

Such was the voice of the exponent of “Libertinism” or “Spiritualism,” the ethical thinker whose ideas were so often illustrated, as we have seen previously, by Bruegel’s graphic works.

Plate 58 is reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

The original drawing, in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England, is signed “Brueggel” and dated 1556, but by a hand probably not that of Bruegel. The engraving, which bears the same date in the lower left corner, was published by Cock. The engraver probably was van der Heyden.

Together with the “Big Fish Eat Little Fish” (reproduced as Plate 29), this is, as Ebria Feinblatt points out, “Bruegel’s earliest Bosch-type composition.” Individual elements appear here which are derived from Bosch, and, in some cases, used again elsewhere by Bruegel. A pair of these are juxtaposed near the bottom, just left of center: on a floating barrel sits a fat figure tilting against the man-jug on the shore; this is similar to the fat figure representing Carnival in Bruegel’s 1559 painting “The Combat between Carnival and Lent.” The man-jug here is believed to be a lineal descendant of a similar monster in the Bosch altarpiece of the same name, “The Temptation of St. Anthony,” in Lisbon, Portugal.

An unusual relationship is revealed when the original drawing and this engraving are compared: the latter is not a reverse or mirror-image of the former. They “run in the same direction.” Also, because the original has some “continuous tone” brushwork supplementing the line drawing, the engraver’s technique differs in the corresponding areas—notably, according to Miss Feinblatt, in the garments worn by St. Anthony at the lower right, and in the scarf bound around the gigantic floating head.

The story of St. Anthony of Thebes, founder of Christian monasticism, inspired many drawings and paintings. He lived during the latter half of the third and first half of the fourth centuries, some 900 years before the other famous St. Anthony, of Padua.

The earlier Anthony was born in Middle Egypt. When about twenty he began to live as an ascetic. After fifteen years he became a solitary also, existing alone on a mountain near the Nile for a number of years. Later he directed the monastic organization of monks, ascetics like himself.

In succeeding generations his fame was associated chiefly with his heroic resistance to the temptations and devilish lures that were sent to assail him. These were not restricted to images of seductive females and fleshly delights. According to Athanasius there were at first also alluring thoughts of domestic duties and satisfactions as contrasted with his bitter trials. When the lures of family joys and fornication did not defeat him, the devil tried to get at him through ambition, taking the guise of figures who acknowledged that Anthony had bested them. The devil also assailed him in the guise of wild animals, soldiers, women, and what not. Sometimes the Evil One attacked the Saint and thrashed him sorely.

Below the engraving appears a line (verse 19) from Psalm 34 of David (the engraved attribution to Psalm 33 gives the Vulgate numbering): “Many are the afflictions of the righteous: but the Lord delivereth him out of them all.”

Another reference to David, the Psalmist, is pointed out by Barnouw. Within the hollow tree to the right of the Saint sits David himself singing assurance and courage to him. The song, this fine scholar says, is Psalm 11, especially that part which declares (in the following quotation, the writer has combined desirable elements out of the King James version and the Masoretic Text of 1917, Jewish Publication Society of America):

In the Lord I have taken refuge;

How say ye to my soul:

‘Flee as a bird to your mountain’?

For, lo, the wicked bend the bow,

They have made ready their arrow upon the string

That they may shoot in darkness at the upright in heart.

Sure enough, as Barnouw points out, the archer is in the crotch of the tree above, aiming his arrow toward the holy man’s upright heart.

Though the quoted psalm applies admirably, the present writer has doubts about identifying the lute player in the hollow tree with David. Hollow trees—in fact anything unusually hollow—usually represent abodes of sin or sterile corruption in Bruegel’s fantasy.

In its drastic criticism of the condition of both Church and State, this may well be the most “outspoken” of Bruegel’s graphic works. Corruption and decay beset both the state (the one-eyed head below) and the Church (the rotting fish above). The cross on the flag flying from the tree through the fish’s mouth is notably clearer in the print than in the original drawing. That flag is actually a Papal bull, as the twin seals indicate.

The huge head below is foundering. Two men in the lower jaw bail, but cannot keep it afloat. A column of smoke appears in place of the tongue (suggesting some sort of political hot air?). No wonder the fisherman in the rowboat wildly calls for help.

The head of the great fish above, says Barnouw, represents “the papacy, the source of the corruption within the body of the Church.” Within that body men fight and murder. Demons gather like birds of prey. Yet, says the same scholar, the promise of “new life” for the Church is suggested by the tree growing through the mouth of the fish. (We note, however, that the tree is leafless, and seemingly lifeless.) A local church, at right, is ablaze.

Amidst conflict and confusion, the enemy draws near. At left center an Oriental-looking dome on the water disgorges a multitude of men. These are identified with the Turks, recurring threat to Christian Europe.

St. Anthony here represents saintly strength, a special case of the sin-resisting fortitude previously shown in the Virtue series. As he reads his sacred book, he is neither cast down nor distracted—not even by a purse which spills coins provocatively near his feet. He disregards also the knife with its suggestion of violence, or possibly of food to slice. For nearer to him is the skull, that ever-present reminder of mortality. The Saint’s heart is attuned only to the life beyond. The degradations and dangers of the world around do not touch him.

Next to Bruegel’s name at the lower left is the date, 1565, of the original, a grisaille painting now in the Antoine Seilern collection in London. This engraving was executed by Pieter Perret in 1579, ten years after Bruegel’s death.

Grave, unpretentious, and haunting is this work, and obviously—to use a much-abused word—sincere. In manner and mood it manifests the special place it held, according to a plausible anecdote, in the heart of its creator. It is said that Bruegel retained it as a personal possession and that it was still among his artistic effects at the time of his death.

The Latin line below gives the quotation from John 8:7: “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” Jesus is pictured tracing with his finger the corresponding words in Flemish.

The essentials of the incident as told in the King James version of the Bible are as follows:

Jesus . . . came . . . into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he . . . taught them. And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and . . . they say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act. Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?

. . . Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not. So when they continued asking him, he . . . said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her. And again he stooped down and wrote. . . .

And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing. . . .

When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee?

She said, No man, Lord.

And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more.

Perhaps the highest praise for this print is to say that it conveys understanding and sympathy for an utterance whose ethical beauty and deep humanity are unfading.

The poignance and significance of the moment are underscored in light. Jesus’ figure stands out as if illuminated. The whiteness of his robe is even more striking in the original grisaille painting, as reproduced in the Stridbeck volume (Plate 86).

Bruegel’s use of light to symbolize divine power and sanctity has been mentioned in connection with “The Death of the Virgin.” Tolnay has discussed the use of light in Bruegel’s paintings (see his article, page 123, in Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlung in Wien, neue Folge, 1934).

From hip to neck, Jesus’ robe forms an area of stark white. It points in the direction of the composition’s emphasized diagonal, running from lower left to upper right.

The faces or garments of principal figures round about are illuminated as if reflecting this radiance. This applies especially to the two disciples who stand closest to the left edge of the picture, among the group of some eight disciples; and to the attentively watching figures of principal scribes and Pharisees in the group at the right. It applies above all to the figure of the adulterous woman herself. The grisaille original appears even more strikingly than the print to make the figure of Jesus the source of light.

In the shadow are the people “convicted by their own conscience” who have turned to the right or left to leave the scene. Workers, soldiers, old people, children are among them. A total of some thirty individuals are seen wholly or in part, and possibly a dozen more are suggested faintly in the farthest background.

Two stones lie unflung on the ground just below the butt end of the spear carried by the backward-glancing soldier.

Comparison of the original grisaille with this print shows “small” but important differences in facial expression. In the grisaille the adulteress looks grateful, affected, and involved; in the print, more placid and aloof. In the grisaille the backward-glancing soldier, his mouth somewhat open, seems to feel greater pain and chagrin.

In other respects the engraving remarkably recreates fine details of delineation in the painting. In both, for example, the face of the scribe or Pharisee “spokesman” shows a slight smile, partly ingratiating, partly smug, as if he were expecting to catch Jesus in the trap of his question. In both, also, the faces of the apostles on the other side indicate a fine mingling of concern, confidence, and pride in their master.

The painting, as might be expected, seems more sensitive, subtle, and humanly expressive. After all, Bruegel may have had, and probably did have, “something to say” about fine points of many of the engravings made from his originals while he was alive. This could not apply to the print reproduced here.

Three states of the plate are known for this subject. In the first state no publisher’s name appears; in the second the words “Antverpiae apud Petrum de Jode” appear in the center (below the Latin quotation from the Gospel); in the third those words have been removed, and inside the picture, directly under Jesus’ printing on the ground is added the new publisher’s identification: “Visscher excudit.” Another addition in the third state is the initial “P.” placed ahead of the name Bruegel at the lower left. Still another, minor but interesting, involves Jesus’ printing on the ground: in the second state the letter “I” in the first word “DIE” shows a needless diagonal which makes it look like an italic “V.” In the third state this is corrected, so that the “I” has become exceptionally heavy, and much of the shading behind and below the word has been obliterated.

The engraver of this imposing and important work is not known positively; however, he seems to have been Philippe Galle, the same who engraved “The Death of the Virgin” (seen as Plate 56).

The originals of both of these remarkable engravings were executed in monochrome—that is, they were continuous tone grayscale pictures, known in art jargon as grisaille. The later (1564) original, however, was painted in oils, whereas this one(c. 1562) was executed in ink or wash, with both brush and pen as the artist’s tools of application. Grossmann speaks of it as being done “mainly with the brush to which only a little pen work is added.”

This original grisaille is in the great Boymans Museum in Rotterdam. Its attribution to Bruegel has been disputed by Tolnay, but upheld by Cohen, Friedländer, and Grossmann. The weight of authority seems to place it securely within the body of Bruegel’s works.

Pictorial details show that the artist here has based his picture primarily on the simpler version of the two first synoptic gospels, notably on that gospel attributed to Mark which according to Ernest Sutherland Bates “was unquestionably used by the authors of Matthew and Luke and was thus the earliest of the four.”

In Mark 16:1–7, “Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, had bought sweet spices that they might come and anoint” the body of Jesus.

And very early in the morning the first day of the week they came unto the sepulchre at the rising of the sun. And they said among themselves, “Who shall roll us away the stone from the door of the sepulchre?” And when they looked, they saw that the stone was rolled away: for it was very great. And entering into the sepulchre they saw a young man sitting on the right side, clothed in a long white garment; and they were affrighted.

And he saith unto them, “Be not affrighted: ye seek Jesus of Nazareth, which was crucified: he is risen; he is not here: behold the place where they laid him. But go your way, tell his disciples . . .”

The version of Matthew (28:1–8) has supplied the picture’s “angel of the Lord” and its group of soldiers, guards or “keepers” who in fear of the angel “did shake.” However, the “great earthquake” mentioned in Matthew is nowhere suggested in the print.

The presence at the scene of the risen Jesus, bearing cross and banner and radiating light, is symbolical rather than an illustration of anything stated in the gospel story. Nothing there suggests that Jesus appeared to either of the two Marys when they were at the tomb. Accordingly, in this print, they, their companions, and the guards, awake and asleep, are all unaware of his presence.

The drawing of Jesus’ face here conforms rather closely with his features as depicted in other prints after Bruegel originals. Jesus’ bodily proportions are excessively elongated. This was characteristic especially of Bruegel’s early delineation of sacred, saintly or angelic figures, as exemplified in paintings such as the “Fall of the Rebel Angels” (1562), etc. The elongation spelled sanctity; similarly—as we have seen—squat, low figures signify ignorance, evil or sin. This use of elongation is comparable to that which is so striking in El Greco’s paintings of sacred subjects.

Plate 61 is reproduced by permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (Rosenwald Collection).

This is another engraving by Philippe Galle. The date, 1571, appears below Jesus’ shoe. Two states of the plate are known. The second was issued by Philippe Galle’s son, Theodore.

(Since this is one of the engravings executed after Bruegel’s death, he could have had no influence on the engraver’s work. According to the rigid criteria of what constitutes a “fine print,” direct influence or supervision of the artist in the preparation and printing of the plate or block is essential. Such considerations seem of little importance here, however.)

Some dim suggestion as to a possible date for a lost Bruegel original may be gained from the fact that a similarity has been pointed out between (a) the three figures here, and (b) a walking trio of peasant women in Bruegel’s 1565 painting “The Haymakers” (also known as “Hay-Making” and “July”).

In that painting, too, the three figures walk side by side in stride, the face of the middle figure being turned toward us. However, the likeness seems too tenuous and far-fetched to support any substantial conclusions.

Fritz Grossmann says of this print that it “seems to render only part of an elaborate composition, which in its complete form provided the basis for a painting by Peter Brueghel the Younger.”

Marked similarity exists between the features of Jesus seen full face in this print and in profile in “Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery,” reproduced as Plate 60. There is the same parting of the long hair in the middle, the same downturned moustache and short beard, the same rather heavy eyes with downcast lids dominating a slender face. The features of the two disciples, in comparison, here appear earthbound, rugged, almost coarse.

The incident illustrated is reported in two of the four synoptic Gospels. It took place at a time later than the Resurrection.

From Mark 16:12–13: “After that he appeared in another form unto two of them as they walked, and went into the country. And they went and told it unto the residue: neither believed they them.”

From Luke 24:13–28: “And, behold, two of them [apostles] went that same day to a village called Emmaus, which was from Jerusalem about threescore furlongs. And they talked together . . . And it came to pass that while they communed . . . Jesus himself drew near and went with them. But their eyes were holden that they should not know him. And he said unto them, ‘What manner of communications are these that ye have one to another, as ye walk, and are sad?’

“And the one of them, whose name was Cleopas, answering said unto him, ‘Art thou only a stranger in Jerusalem, and hast not known the things which are come to pass there in these days?’”

They tell the story of the crucifixion, the entombment, and the finding of the empty tomb. . . .

“Then he said to them, ‘O fools, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken: Ought not Christ to have suffered these things and entered into his glory?’

“And beginning at Moses and all the prophets, he expounded unto them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself. And they drew nigh unto the village [of Emmaus] ...”

Jesus’ expression of face and gesture can readily be coordinated with that text.

All three figures wear pilgrim’s garb of Bruegel’s time. Each carries the pilgrim’s staff. The prevalent tradition of religious art in France and the Netherlands was to represent the three on the road to Emmaus in the garb of pilgrims, though the Gospels said nothing specific to that effect.

Translation of Latin caption: Christ, you deign to assume the appearance of a pilgrim in order to confirm our hearts in steadfast faith.

Plate 62 is reproduced by permission of Mr. and Mrs. Jake Zeitlin, Los Angeles, California.

The engraver is Philippe Galle, and the date 1565.

Here Bruegel interprets and extends Jesus’ parable from John 10:1–16. In somewhat less archaic language than that of the Authorized Version, the relevant portions of the parable follow:

“He who does not enter by the door into the sheep-fold but climbs up some other way, is a thief and a robber. But he who enters in by the door is the shepherd of the sheep. . . .

“And when he puts forth his own sheep he goes before them, and the sheep will follow him for they know his voice. And they will not follow a stranger, but will flee from him, for they do not know the voice of strangers. . . .

“I am the door of the sheep. ... If any man enter in by me he shall be saved, and shall go in and out, and shall find pasture. . . . I am the good shepherd.”

Jesus, as the Good Shepherd, stands in the door of the allegorical sheepfold. He carries a ewe, and other sheep look up to him in confidence. On both sides and above, thieves and robbers break into the fold seeking to steal the sheep. They come, at the left, with pickaxe, with lantern, with sword. They come, at the right, with ladder and with knife. They break in through walls and thatched roof. Nearly a dozen figures are engaged in this breaking and entering. At the lower right of the doorway, one of the thieves has leaned his axe. Its blade serves as a panel for the initials of the engraver, Galle.

In the upper left and right corners in triangular spaces above the roof are shown related episodes of sheep-tending. At the left, the shepherd defends his flock with a spear against an attacking wolf. At right, the unfaithful shepherd runs from his flock, and they fall prey to the wolves.

The engraving refers to verses 11–14 in this chapter of John, in which Jesus says: “. . . the good shepherd gives his life for his sheep. But he who is a hireling and not the shepherd, whose own the sheep are not, sees the wolf coming and leaves the sheep and flees, and the wolf catches them and scatters the sheep.... I am the good shepherd and know my sheep, and am known of mine.”

The Biblical citation is inscribed above the door.

In comparison with other engravings based on the good shepherd parable of the same period, Ebria Feinblatt finds that “Bruegel took over the theme and general iconographic intent; but gave it a more prevalent import, extending the sense of ungodliness to all classes of society.”

Class differences are apparent from the dress and features of the thieves breaking into the sheepfold here.

Bruegel used the parable of the “Unfaithful Shepherd” in painting also. Two such paintings have survived, the better of which is in the John G. Johnson collection in Philadelphia. Some scholars believe that both paintings are good copies of a lost original by Bruegel; others believe that at least one is the original, though so repainted and done over by hands other than Bruegel that it can no longer be considered an “original” in the strict sense. However, there is no reason to doubt that the conception and design, as well as all important details, are Bruegel’s. The simple, concentrated, and powerful arrangement of landscape and the emotional central figure suggest in fact the later Bruegel rather than the earlier artist who tended toward more crowded and “simultaneous” canvases, lacking subordination.

The unfaithful shepherd is shown running in full flight. He carries his shepherd’s staff in his hand, and is just passing a milestone placed cryptically but somehow significantly at the side of the path. The landscape behind is flat and bare. Looking back over his shoulder this pastoral deserter can see that the ravening wolf is already killing a sheep, while the rest of the flock is scattered.

It has been suggested that this picture may have represented a cryptic commentary on the action of Margaret of Parma. She had been the Netherlands regent for the Spanish Emperor, Philip; but after Philip sent the bloody Duke of Alva in 1567 to stamp out heresy (Protestantism) and dissent, she quit her post. Alva became dictator, and within half a dozen years completely transformed the country for the worse.

Bruegel died early in the period of the Alva terror, but not too early to have experienced, and painted such a commentary on, the flight of Regent Margaret from her proper sheep, the people of Spain’s Netherlands possession. The date of the engraving is, however, too early for assuming any such political meaning here.

Translation of Latin inscriptions: (On the lintel:) John 10: I am the door of the sheep. (Bottom:) Stable your flocks safely here, O men, come to my roof; while I am shepherd, the door is always open. Why are you breaking through the walls and roof? That is the way of wolves and thieves, whom my sheepfold shuns.

The original drawing, in the Aibertina Museum, Vienna, is signed “brueghel” and dated 1558. This engraving, also dated 1558, is by van der Heyden, and in many ways is typical of his engraving of Bruegel’s original drawings.

Verses below in Latin and Flemish set the tone for this, an “hour of decision” or “moment of truth” subject. A free equivalent of the Flemish and the Latin:

Come, all who’re by my Father blessed,

To the eternal realm up higher;

But down, all you who are accursed,

Down into everlasting fire!

Jesus hovers here in his role of final judge over men. A rainbow supports him. His feet rest upon a globe, emblem of the world. On one side floats the sword of judgment, on the other the branch of glory.

The last trumpets are here blown by two pairs of angels. On the left one pair—perhaps including Gabriel—sound the summons for the blessed. These throng in a massed column up the hill, toward “the eternal realm up higher.”

But on the right—here the side of the damned—the two flying trumpeters hover on strangely insect-like wings, not on the orthodox feathery pinions of their opposite numbers. The lower of the two right-hand angels, in fact, displays claw-like appendages instead of feet, as if infernal influences had altered angelic anatomy. This trumpeter is all curved—wings, “legs,” general posture, even trumpet. Perhaps it is a “fallen” angel.

Saints and patriarchs watch from billowy clouds at the upper right and left. Their hands are clasped in adoration. Some of these doubtless are to be understood as “Old Testament” Fathers who long before had been liberated from Hell, or Limbo, as previously shown.

Graves have opened in the foreground of the engraving. The dead arise, entire, obedient to the trumpeted summons. They come up with clasped hands. Demons assist in uncovering coffins, as if eager to get at those who will be condemned to everlasting torment in Hell.

Many monsters fill the foreground. Others harry the lines of the damned and herd them into the gaping Hell-mouth at the middle right. Certain monsters, in fact, seem to pursue the rear guard of the blessed, somewhat left of the point under the judging Jesus. However, angelic escorts carrying tall crosses safely shepherd the blessed up toward the everlasting bliss which is in store for them.

Hell-head itself looms like a monstrous Leviathan or whale. It resembles sea creatures we have seen in earlier engravings from the Ship series. On the brow of Hell-head is perched a strange and rather jaunty hat, while on the tip of its nose is perched a cosy little demon.

The demonic crew at the center carry torch, hook, and ladder. No doubt these refer to the hell-fires raging below.

Less than twenty years before the execution of this engraving, Michelangelo completed the greatest and most terrible of all Last Judgments: his enormous masterpiece in the Sistine Chapel. Bruegel studied and worked in Rome during his Italian journey (1552–1553). It is tempting, and not too far-fetched, to suppose that he saw the Michelangelo “Last Judgment,” then completed some nine years.

Between the vast painting and the small drawing for engraving, exists an abyss of difference deeper than that of medium and size. It is a deep diversity of concept. Michelangelo’s Jesus is the omnipotent and angry magistrate, judge, and muscular executioner in one. In righteous rage he repudiates the sinners, hurling them down to unspeakable horrors. It is a spectacle to inspire waking nightmares even in a twentieth-century spectator.

Far different is the central figure of the Saviour drawn by Bruegel here. His face is serene, his gestures neither imperious nor threatening. Jesus considers and assents to the necessary outcome here, but he does not revel in it, nor does he seem to resent the damned. He is compassionate, not enraged. This is by no means a God of vengeance.

And the action below, in spite of fantastic fiends, is not likely to convey a feeling of terror today. It is, after all, a medieval sort of mingling of what we “moderns” have come to think of as opposites. Here, the sinner’s downfall and the clown’s pratfall are set side by side. The ghastly and the grotesque are interwoven. Tragedy goes hand in hand with gross crudity, awfulness with awkwardness. And even the theology of final things, eschatology, is not far distant from scatology.

It does not seem likely that print purchasers in Bruegel’s day were severely shocked or depressed by such presentations of the “shape of things to come” as this engraving offers. They were quite familiar with “morality” plays, passions, and masques in which Hell, damnation, the Day of Judgment, and the Devil himself were all sources of slapstick and gross guffaws, as well as edification and uplift. At each carnival or kermess, stage directors and designers did their utmost to create Hell-mouth sets more gruesome and teeth-chattering than anything previously achieved. The more horrendous and convincing, the better. Infernal evidences and direct diabolical intervention were normal, if not actually essential, for any popular passion play during the Middle Ages and long afterward.

Barnouw surmises that Bruegel himself may have designed elaborate Hell-mouth settings for passions and moralities in his time, for, after all, “no one could create a gaping hell monster more suggestively.”

Truly, no one could—and it is not the least of Bruegel’s many merits that the same hand which gave us “Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery” could also create this “Last Judgment,” as well as all the other wonderful records of his graphic worlds.

Plate 64 is reproduced by permission of the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, San Francisco, California.