1

Spatial Marketing and Geomarketing

The terms “spatial marketing” and “geomarketing” call for the following questions:

- – What is space?

- – Why introduce space in marketing in an almost systematic, if not systemic way?

- – Why expand the already vast field of geomarketing?

What is space? The recent French “yellow vest” crisis has shown how much making decisions without taking into account space or, as we now say, territories, can lead decision-makers to provoke reactions that are then very difficult to manage. Can we say that this “yellow vest” crisis invokes “geography is destiny”, as the American thriller writer James Ellroy likes to talk about? Making decisions today, either for private or public institutions without caring deeply about local issues can lead to a profound crisis. Everybody is not supposed to be mobile as expected.

Defining space and quickly understanding the consequences of these decisions on the “territories” for which we are responsible, whether at the level of a State or a company, are today prerequisites for good management of the organization for which we are responsible. However, the principle of subsidiarity (Martini and Spataro 2018) had been defined at the European level in the 1980s: “a central authority can only carry out tasks that cannot be carried out at a lower level” or “the responsibility for public action, when necessary, lies with the competent entity closest to those directly concerned by this action”, a recommendation that most companies cannot deny today. This principle has even been associated with the sustainable nature of economic activity in particular (Gussen 2015).

Why introduce space into marketing in an almost systematic, if not systemic, way? The reason is not only the need to localize all market characteristics (Rigby and Vishwanath 2006): customers, suppliers, points of sale, logistics and many other aspects revealed in this book. Even technological change requires us to take into account geographical space. The almost systematic use of GPS (Global Positioning System) and soon of the European Galileo system, is becoming increasingly present and is forcing all actors, suppliers and demanders as well as market facilitators to introduce spatial considerations into their reasoning, decisions and actions. The term systemic can also be used insofar as, if the company is considered as a system, it must now adapt as well as possible to its environment, whether for economic or environmental, or even social and cultural reasons.

Why expand the already vast field of geomarketing? In fact, this term was coined in France by the professional world when eponymous software spread to companies and local authorities; the technical dimension is therefore strong.

Wikipedia gives this definition: “Geomarketing is the branch of marketing that consists of analyzing the behavior of economic individuals taking into account the notions of space.”1 And the same source confirms this technical side:

Geomarketing is present in various applications, such as studies of trading areas, store location studies, potential studies, sectorization, optimization of direct marketing resources (phoning, ISA, direct mail, etc.), network optimization, etc. Geomarketing frequently uses Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to process geographic data using computer tools.

Wikipedia also reports that

English speakers use the term Location Business Intelligence (or geo-business intelligence), which is more appropriate when the approach concerns marketing; but the discipline also applies to territory development in the context of socio-economic studies.

In local authorities, geomarketing has become an essential tool for the development of their territorial marketing for the management of public spaces from a social, economic or tourist perspective. But reducing geomarketing to location choices undoubtedly limits what will be the common thread of this book: the introduction of space into marketing decisions regardless of the sector of activity.

The objective of this book is therefore to broaden this field in a strategic perspective while addressing the main technical aspects of geomarketing in relation to the elements of the marketing mix for all companies. It will therefore take into account the specificities of sectors such as retailing, services and technology.

While mapping is certainly helpful, it is not the only means available to decision makers. The accelerated development of mobile marketing thanks to the rapid spread of smartphones reinforces the need to expand the field of geomarketing; indeed, can we imagine a smartphone without GPS? And even if the geolocation of smartphone owners poses legal problems, it is essential and many techniques have been developed to refine the accuracy of its geographical location.

Tracing a future perspective on the use of space in marketing decisions requires studying the historical trajectory of this idea. And even if it is possible to go even further back in the history of thought, as we will see, authors such as von Thünen, Hotelling, Reilly, Christaller, etc., in the 19th Century and in the first half of the 20th Century, whether economists or geographers, were able to trigger “spatial reflection”. This chapter, after a few definitions, traces the consideration of space in order to understand where the fields of geomarketing and spatial marketing come from before better understanding them.

1.1. Defining space

Space has long been reduced to a mathematical notion: “a geometric concept, that of an empty environment” (Fischer 1981). Today we talk about social space, and the space treated here is in fact the market. But before coming to this notion, it is important to clearly identify all the variants of this concept of space. We talk a lot about territory, about countries (within a country in the sense of a nation) and about “spatial surface”. A space can be defined both in geographical terms and in relational terms (Duan et al. 2018), or even in historical or political terms (Paquot 2011). We then have a better understanding of the polysemy surrounding the notion of space. Space would be “a place, a reference point, more or less delimited, where something can be located, where an event can occur and where an activity can take place” (Fischer 1981), but to which it would be appropriate, in order to conceptualize it, to associate all the spatial practices of individuals (Lefebvre 2000) thus showing the close relationship between individuals and space (Fischer 1997). However, this relationship is currently undergoing major upheavals due on the one hand to societal changes (Levy 1996; Oliveau 2011) and on the other hand to extremely rapid technological change.

The territory has received several definitions resulting from two different meanings: a first one defines a territory as a place where a population resides, while a second one, more precise and legal, not to say more political, considers the territory as a place where power is exercised that can be justly political or judicial (Paquot 2011).

From these two meanings, definitions will be added that are increasingly out of step with each other. This drift may also explain some misunderstandings, with the State preferring to put forward the second meaning, favoring time over geographical space in order to establish its domination, when the people understand the first one which prefers living space over the time of power. It is then easier to understand why historians and geographers do not necessarily speak the same language when describing territories.

A country is a French administrative category defined by the law of February 4, 1995, on guidance for spatial planning and development (LOADT), known as the Pasqua law, and reinforced by the LOADDT (known as the Voynet law) of June 25, 1999. But it is now prohibited to create new countries (article 51 of law no. 2010-1563 of December 16, 2010, on the reform of local authorities). A country is defined as follows:

A territory that presents a geographical, economic, cultural or social cohesion, on the scale of a living or employment area in order to express the community of economic, cultural and social interests of its members and to allow the study and implementation of development projects.

Although considered as an administrative category, a country is neither a local authority, nor a canton, nor an EPCI (Établissement public de coopération intercommunale) and therefore does not have its own tax system. A large part of France is thus composed of “countries” resulting from contracts concluded between municipalities; this is of particular interest to rural areas.

The spatial surface is in fact a rather vague concept, but it expresses the difficulties resulting from the spatial heterogeneity encountered in certain spaces, due to discontinuities resulting from irregular borders, for example between regions, peninsulas or real inner holes. This heterogeneity can make the valuation of house prices very complex. This idea was applied to define house prices in the Aveiro region of the Ílhavo district (Portugal) (Bhattacharjee et al. 2017).

1.2. From geomarketing to spatial marketing

After describing the evolution of spatial marketing and placing it in the midst of other disciplines, it will be necessary to define this field, then to specify its differences from geomarketing, before identifying its content.

1.2.1. Spatial marketing: between economics and geography

It all starts with the development of the location theory of economic activities. Thomas More defended, as early as 1516 in his book Utopia, the need to divide the city into districts to accommodate each a market (Dupuis 1986). In his economic writings, Turgot (1768) posits three principles of the theory of store location:

- – the centrality of the points of sale;

- – the demographic threshold for the establishment of businesses, the existence of a sufficient market;

- – the grouping of purchases.

On a more methodological level, von Thünen (von Thünen 1826), considered as the “father of location theories” (Ponsard 1988), then explains that “the optimal locations of agricultural activities are such that in every part of the space the land rent is maximized”. He thus founded the spatial economic analysis which he would later rely on to design his industrial location models at the beginning of the 20th Century (Weber 1909), which in turn would be used to model the expansion or spatial development of retail chains (Achabal et al. 1982). We can thus see how, in terms of the use of space in economic and managerial theories, progress has taken time.

Another economist (and also a leading statistician), Hotelling (Hotelling 1929), described in a celebrated article the consequences of location changes using a simple example and thus defined the principle of minimal differentiation, often referred to as the Hotelling rule (Martimort et al. 2018) or the Hotelling law (Russell 2013). Hotelling developed the idea that competition between producers tends to reduce the difference between their products. His theory is still being discussed today and is still the basis for much research. It has thus been possible to demonstrate in a theoretical way the contribution of advertising in order to allow companies to bypass this principle of minimal differentiation (Bloch and Manceau 1999). Geographers then developed the concept of central squares (Christaller 1933) from which the hierarchy of cities and the hexagonal shape of the geographical segments surrounding the squares (cities, towns, villages) were deduced (see Figure 1.1).

Each economic actor maximizes its utility (consumer) or its profit (firm) in a homogeneous space where prices are fixed and where the cost of transport depends on distance. The hexagonal shape of Figure 1.1 theoretically facilitates a perfect interlocking of these segments around the squares that form a network as shown in southern Germany (Christaller 1933), southwestern Iowa, northeastern South Dakota and the Rapid City area of the United States (Berry 1967). In these great plains of the United States, a diamond-shaped network of central squares was observed; this is called a rhomboidal grid. This network of markets, with regular hexagonal outlines, suggests, on the one hand, the existence of a single equilibrium configuration with a given number of firms on the market, and on the other hand, the domination of this network with free market entry (Lösch 1941). This author formalizes the central place theory using a micro-economic approach. It is also based on the actual price of a good defined from its factory price plus the cost of transport. As the latter increases with distance, the quantity requested will be reduced accordingly, thus allowing the construction of space demand cones by integrating the function linking quantities requested, on the one hand, and price and distance in transport costs, on the other hand. Lösch then defines a profitable location as one whose sales amount, as determined by the spatial demand cone, provides the appropriate rate of return. This concept would correspond well to the markets for industrial goods (Böventer 1962). This design will be challenged, because this hexagonal network is not the only equilibrium configuration (see above the rhomboidal grid) and free market entry does not necessarily lead to hexagonal shapes of market segments (Eaton and Lipsey 1976). In any case, it is possible to retain from this work the idea of centrality with the objective of reducing distance for the greatest number of people and thus facilitating access to goods and services.

Figure 1.1. Theoretical and schematic representation of central place theory

(source: after (Christaller 1933))

Shortly before, another geographer (Reilly 1931), a consultant to his state, had proposed a law of retail gravitation, often called Reilly’s law, based on the notion of gravitation by analogy with Newton's theory applied here to retail activities. This law was for a long time the basis for many academic and professional projects, for example to set up supermarkets in rural areas or malls. Based on this pioneering work, researchers have proposed models to better understand consumer spatial behavior and, above all, to predict the future level of city activity or store sales (Converse 1949; Huff 1964; White 1971) until these attraction models become widespread, whether spatial or not (Nakanishi and Cooper 1974).

Pioneering work in space marketing as early as the 1970s and based on time series data, long before geomarketing software appeared, showed that it was important to study market shares according to sales territories in order to understand how buyers react and to better predict these sales (Wittink 1977). It can be concluded that advertising, which is supposed to increase sales if adapted to the territories, can improve price sensitivity.

However, a few years later, based on previous work (Ohlin 1931), it became apparent that marketing researchers were not interested in spatial or regional issues (Grether 1983). It could not be said today that much has changed. Even store location issues are no longer of much interest to researchers, probably because it is mistakenly believed that the Internet has definitively removed the tyranny of distance. However, most of the pure players, those businesses that are only present on the Internet, are starting to open brick and mortar stores that are either physical or “hard”: Amazon has acquired the Whole Foods Market network of organic stores in the United States.

Moreover, the very rapid development of applications (apps) on smartphones may change the situation by creating on the one hand a real mobile commerce and on the other hand a new kind of spatial consumer behavior favoring mobility (or rather ubiquity), comparisons of products, services, prices, etc.

1.2.2. Definition of spatial marketing and geomarketing

Spatial marketing is a broader and more conceptual field than geomarketing, which remains more oriented towards mapping techniques.

1.2.2.1. Definition of spatial marketing

Spatial marketing can be defined as anything related to the introduction of space into marketing from a conceptual, methodological and of course strategic point of view (Cliquet 2006, 2003). This implies taking into account not only issues related to the local or regional environment at the microeconomic level (Grether 1983), but also in relation to territorial coverage in the geographical sense. This concept does not necessarily imply that territories correspond to political division and/or interculturality at a more socio-cultural scale at the macroeconomic level, in other words in relation to national and international frameworks (Ohlin 1931; Hofstede et al. 2002).

The many issues developed in this book concern not only marketing in the strict sense of the term, but also other management disciplines such as information systems management and human resources, strategy, logistics, organization at local, regional, national or international level. Spatial marketing is useful in the management of organizations insofar as it makes it possible to specify and strengthen proximity with the customer and therefore customer relations depending on where the customer is located. It authorizes the link between this geolocation and the customer’s personal data. The verb “authorize” is used intentionally, because the risk of breaking the boundaries of individual privacy is real; it is an important societal issue as is the installation of video cameras in public places for security reasons. Surveys on personal data protection (privacy) show that consumers are aware of possible abuses, but this does not prevent them from using smartphones and tablets (Cliquet et al. 2018), and the Absher application that Saudi Arabian men use to track their wives does not help.

1.2.2.2. Definition of geomarketing

Geomarketing is based on digital geography using computer science, that is, computerized cartography and therefore geography on the one hand and marketing on the other. It is a term coined in France by practitioners in the 1980s. Strangely enough, this word is almost unknown in North America 30 years later. On the other hand, we hear about micro-marketing, geodemographics, GIS or Location Business Intelligence in the United States, even though people are familiar with geomarketing in Quebec. It has subsequently spread to the European continent: there is research on the openly displayed theme of geomarketing in Belgium (Gijsbrechts et al. 2003), and above all specialized works, often short and technical, for example in Germany (Schüssler 2006; Tapper 2006; Grasekamp et al. 2007; Herter and Mühlbauer 2007; Trespe 2007; Menne 2009; Kehl 2010; Kroll 2010), Spain (Chasco and Fernandez-Avilez 2009; Alcaide et al. 2012) and Italy (Galante and Preda 2009; Cardinali 2010; Amaduzzi 2011). In France, there are books by consultants that generally present, in a clear manner, the possibilities offered by their firm (Marzloff and Bellanger 1996; Latour 2001) and academic books either oriented towards business studies (Douard 2002; Douard and Heitz 2004) or methodology (Barabel et al. 2010) or concept and strategy (Cliquet 2006). Some books on digital geography also deal with geomarketing (Miller et al. 2010).

There are of course many definitions of geomarketing. However, most of these books agree at least on the objective of geomarketing, which aims to introduce spatial data into marketing analyses that are often totally lacking. However, “about 80% of all business-relevant information within a company has a relation to spatial data” (Menne 2009), in other words, 80% of the information related to a company's business is linked to spatial data.

Some will argue that the dramatic increase in online data tends to reduce the importance of spatial data. In fact, the opposite is true since a very large part of this online data is geolocated.

Geomarketing can simply be defined as a field involving disciplines such as digital geography and marketing, but also social sciences such as economics, sociology, psychology or anthropology, because geomarketing makes it possible to understand much more precisely the behavior of economic actors and the environments in which they operate. These behaviors and environments are changing increasingly rapidly as a result of demographic pressure and climate change. All these developments cannot be ignored by strategists in both private and public organizations.

1.2.3. Content of spatial marketing and geomarketing

Introducing space into management and marketing decisions in particular means resolving a dilemma that is driven by a priori oppositions such as local versus global or adaptation versus standardization.

1.2.3.1. Local versus global

The local level is often overlooked by strategists, while it can sometimes be realized that a priori remarkable strategies on paper are simply inapplicable on the ground, a fact that many politicians would do well to consider. Neglecting the field has sometimes cost even the largest multinational firms that thought the world would adapt to their strategies and genius: the major American firms have long thought so like General Motors CEO Charles Erwin Wilson, who said in 1953, “What is good for General Motors is good for the United States and what is good for the United States is good for the world.” Today, things have progressed on this front and everyone is aware that globalization is more a myth than a reality (Douglas and Wind 1986). But in the face of this dilemma, a question arises: should we first globalize and then localize in a top-down decision-making process or localize before globalizing in a bottom-up approach? Some believe that it is better to use a “glocalization” process (Svensson 2001; Kjeldgaard and Askegaard 2006; Cliquet and Burt 2011) by trying to show that it is appropriate to globalize your business strategy and at the same time localize your marketing strategy in the broad sense (Rigby and Vishwanath 2006) in order to attract customers very quickly, hence the need for located databases (Douard et al. 2015). We were able to show how Walmart had to change its marketing methods, and thus its so-called organic growth, when this major American distributor bought Asda in the United Kingdom in 1999 (Matusitz and Leanza 2011).

The purpose of introducing space into decision-making processes is both strategic and tactical: strategic, because a strategy must also be able to express itself in terms of territorial gains and not only in terms of turnover or market share, which are too global concepts; tactical, because the company will need to know its local markets well to implement its strategies efficiently and not only effectively.

1.2.3.2. Standardization versus adaptation

The second way of presenting the dilemma refers to the presumed opposition between, on the one hand, standardization (in other words, total standardization) and on the other hand, adaptation, which involves taking into account the local environment. This apparent conflict is frequent, particularly in the definition of retail and service outlet network strategies. The elements at the heart of the strategy are commonly distinguished from the elements at the periphery, which can be described as secondary (Kaufmann and Eroglu 1998). The elements at the heart of the strategy must never be adapted, as they are essential for brand recognition at any time and in any place by real and potential customers. On the other hand, it must be possible to adapt the peripheral elements when necessary in order to satisfy customers as much as possible regarding their tastes, consumption habits and even traditions. This problem is especially specific to the marketing of franchise networks, even if it is found in many sectors from the moment that activities are relocated or spatially distributed (Cox and Mason 2007). Indeed, while chains tend to want to simplify their offers, including geographically in order to benefit from better productivity and therefore lower costs, their customers increasingly want product customization. The idea of mass-customization then emerged as necessary (Pine 1993; Piller and Müller 2004). Indeed, in franchising, the brand is, with the know-how, one of the two fundamental concepts in the very definition of the network’s activities.

Let us take a concrete and very significant example of this problem, the bakery chain under the Great Harvest brand (Streed and Cliquet 2007). The first bakery was opened in 1976 in Great Falls, Montana (United States), the second in Kalispell, also in Montana. But the objective was not to distribute exactly the same type of bakeries everywhere. Freedom has been left to the franchises to manage their bakery (the “front office” in front of the customers) as they see fit, knowing that the “back office”, the making of bread in particular, is maintained by the chain. In fact, the founders, Pete and Laura Wakeman, created the first “freedom franchise”, which they define as follows:

We provide an alternative with some of the advantages of a traditional franchise and some of the fun of a “let’s-do-it-all-ourselves” start-up. Our philosophy is simple: let’s create unique neighborhood bakery cafes that are a reflection of the Great Harvest brand and the bakery cafe owner. We are no cookie cutter franchise. We are a freedom-based, healthy franchise that encourages excellence and individuality (not to mention a spirit of fun and generosity).2

There are now more than 200 Great Harvest franchises in the United States (including Hawaii and Alaska). And every franchised bakery must be the bakery in the city: we immediately see the importance of localization and the need for highly targeted spatial marketing.

But often, the franchisee’s freedom is more restricted and the peripheral components of the franchise are more limited, thus reducing the possibilities of adaptation. However, even large chains such as McDonald’s have realized that excessive standardization can lead to rapid consumer fatigue as consumers become increasingly eager to personalize the service and the products that go with it. The orientation towards “glocalization”, a process already mentioned above, is now effective at McDonald's (Crawford 2015), including in their desire to attract so-called “ethnic” customers: we understand the importance of spatial marketing based on geodemographics, GIS (Geographic Information System) and micromarketing in order to identify these targets and define an appropriate advertising strategy (Puzakova et al. 2015).

1.2.3.3. The fields of spatial marketing

Once these dilemmas have been established, the content of spatial marketing is presented according to the usual areas of marketing:

- – the buyer’s behavior (consumer in B2C, business to consumer, or business in B2B, business to business), this book focusing on the consumer;

- – marketing research concerning market studies in the broadest sense;

- – strategic marketing and marketing management.

Introducing space in these areas involves many changes, sometimes even upheavals, because it is now a question of thinking and acting differently.

1.2.3.3.1. The consumer’s spatial behavior

Consumer behavior can no longer be considered in the same way once space is taken into account. Too little marketing research has considered this spatial dimension in consumer behavior and this requires a revisit to geography (Golledge and Stimson 1997; Golledge 1999).

A few articles have been able to advance knowledge in this area. Work based on reference dependence theory (Tversky and Kahneman 1991; Tversky and Simonson 1993) has led to a better understanding of consumer shopping trips (Brooks et al. 2004; Brewer 2007) (see Chapter 2).

Older work has been carried out on the basis of gravity and/or spatial interaction models (Reilly 1931; Huff 1964; Nakanishi and Cooper 1974).

Increased consumer mobility, their ability to use so-called mobile technologies (smartphones and tablets) and changes in retail offers, physical or virtual stores on the Internet, are accelerating ubiquitous purchasing processes. This evolution makes gravity-based models less efficient even if they are far from useless, if only in the definition of certain geofencing applications, that is, the determination of the attraction or trading area. This technique is described as an extreme form of marketing location and is increasingly used to send promotional offers in the form of coupons to consumers who are either in the store or near the point of sale using SMS on their smartphone (Mattioli and Bustillo 2012). In other words, the issue here is how far away should current or potential customers of promotional offers be alerted, on their smartphone or tablet, when they pass “near” the store or more generally on opportunities that may interest them. Chapter 5 will deal with geofencing.

Consumers are increasingly capable of mobility without it increasing overall: retailers and traders must adapt to it (Vizard 2013). Sometimes it is quite easy. For example, a distributor near the Massachusetts-New Hampshire border found that residents of New Hampshire may not pay the vehicle taxes required in Massachusetts (Banos et al. 2015). He therefore placed an order with a company specializing in geofencing to include all potential customers in New Hampshire in his database. But this is again a gravity-type attraction (Reilly 1931; Huff 1964; Cliquet 1988).

When we want to attract customers who pass near a point of sale, otherwise known as taking advantage of the flows of the temporary attraction (Cliquet 1997a), the operation is more delicate. Indeed, how can this proximity be evaluated? This concept of proximity has become central to the thinking of major retailers, for example. For many years now, people have been wondering about the future of these “shoe boxes”, known as hypermarkets, a store format invented in France in 1963 by Carrefour and copied in many countries, including the United States in the 1990s (Europe can also sometimes be a little ahead). But hypermarkets are increasingly neglected, especially the largest ones, because they no longer meet the needs of customers seeking both purchasing power and another way of life that is less consumer-oriented. Will smartphones and geo-fencing (Streed et al. 2013) be able to save them?

1.2.3.3.2. Spatial marketing studies

The introduction of space in marketing studies implies taking distance into account. Just because we regularly talk about the digital economy, which no longer has a border, does not mean that there is no longer any distance or that everything has been globalized, thus eliminating any local specificity. On the contrary, we are witnessing a real resurgence of the local.

On a more methodological level, distance is a complex variable. A distinction is made between geographical distance and temporal distance: the law of gravity of retail trade uses geographical distance when Huff’s model favors temporal distance. However, the geographical distance is difficult to manipulate. Purely metric distance is only rarely considered, especially in the behavior of out-of-store consumers. Since they travel with their vehicles, or by public transport, the temporal distance (Brunner and Mason 1968) is preferred by researchers and analysts. But it is no more satisfactory, because consumers, like all decision-makers, make their decisions not according to reality, but according to their perception of it. This can probably be partly attributed to bounded rationality (Simon 1955). Under these conditions, the perceived distance should be preferred despite methodological problems (Cliquet 1990, 1995).

With regard to internationalization, companies are not immune to problems related to culture, among other things. The so-called Uppsala model (Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul 1975) underlines the influence of psychological distance to explain the difficulties of export companies. This psychological distance is broken down into geographical, economic, cultural and institutional distances (see Chapter 2).

1.2.3.3.3. Strategy and spatial marketing

Once potential targets have been identified by the spatial study of behavior, the marketing strategy can be defined. Taking the environment into account can lead to the dilemma already mentioned: local versus global. This contextualization can be troublesome, and has been for a long time, because it can lead to conflicting options that can damage the brand image. However, digital mobility tools can partly solve this dilemma by improving customer contact. This evolution implies a better consideration of the link between production and distribution, in other words, logistics. In order to solve the problem of the optimal compromise between quality and cost (and therefore price), effective coordination becomes essential, and only flawless logistics can make this possible. However, logistics also has a cost, and reducing it requires a rigorous control of space by controlling the distribution of products and therefore thanks to a good spatial distribution of sales outlets. We will see that this spatial dissemination of customer contact points implies a different way of thinking about the spatial strategies for setting up sales units, stores, restaurants, hotels, etc., through, for example, the application of percolation theory (Cliquet and Guillo 2013).

This problem of spatial coverage of point of sale networks does not only affect retailing. It is also of interest to manufacturers; some of them have found that traditional media no longer allow contact with the consumer as effectively as before. As the American firm Procter & Gamble has found, individuals now have technical possibilities to bypass advertising on their TV sets or to avoid spam in their mailboxes (Arzoumanian 2005). However, points of sale are now a safer medium: in 2005, Procter & Gamble observed that in the United States, 100,000,000 customers visited Walmart stores every week, 22,000,000 visited Home Depot stores and 42,000,000 visited 7-Eleven convenience stores. Under these conditions, the best located chains are better media than TV or Internet advertising. Moreover, Zara, the Spanish clothing company, has never advertized in the traditional sense and uses its own stores as promotional media. Procter & Gamble had even thought of launching its own chain of stores selling all the company's products, but had to give it up: P&G is primarily a manufacturing company, and retailing is a quite different job.

1.2.3.3.4. Spatial marketing management

The marketing strategy must then be implemented by a marketing management team that also includes the introduction of space into operational decisions. This marketing management involves the definition of a marketing mix that refers to the 4Ps (McCarthy 1960) for Product, Price, Place and Promotion. Chapter 3 of this book shows that the 4P “rule” has been challenged (Van Watershoot and Van der Bulte 1992), and that it is possible to “geolocate” the elements of the marketing mix.

1.3. Spatial marketing and geomarketing applications

The applications of spatial marketing and geomarketing concern both practitioners and researchers. However, it must be noted that, while practitioners have been able to use geomarketing tools to identify sites where to set up points of sale, broadcast an advertising campaign in the regions or practice direct marketing (Ozimec et al. 2010), they suffer from a lack of conceptual models allowing them to better interpret the data. However, it must be admitted that the number of scientific publications in spatial marketing, except those concerning location issues, is limited to say the least.

The beginning of the new millennium was approached like the beginning of the digital age. But we could already regret the “tide” of advertisements received by everyone without too much differentiation (Preston 2000): the spam emails we all receive every day show that 20 years later, things have not really changed. The customer orientation of European distribution companies seems insufficient despite the amount of local information they have in their possession thanks to loyalty cards (Ziliani and Bellini 2004). The mass of data resulting from these cards should make it possible to identify consumers’ needs and desires and thus to offer them appropriate promotional offers: this is one of the purposes of Big Data (Nguyen and Cao 2015) which constitute one of the major challenges of the now-joint research, on the one hand, in marketing, and on the other hand, in management of information systems (Goes 2014).

1.3.1. Applications in retail and mass distribution

Retailing was among the first sectors to be interested in geomarketing techniques. The applications focus on problems related to the analysis of trading areas and the location of points of sale. As far as trading areas are concerned, professional methods were once often based on the determination of primary, secondary and tertiary (or marginal) areas, known as the analog method (Applebaum 1966). This more or less circular representation around the point of sale has been called into question with the appearance of geomarketing software and the possibility of geolocating store customers from their addresses obtained by questioning the customer at the checkout and then thanks to loyalty cards now dematerialized in most stores. The trading areas of the stores no longer have anything to do with concentric circles: we are in fact dealing with “archipelagos” (Viard 1994).

Concerning location problems, articles in scientific journals were mainly published in the 1980s (Ghosh and McLafferty 1982; Ghosh and Craig 1983; Ghosh 1984; Ghosh 1986; Ghosh and Craig 1986; Ghosh and Craig 1991) and based on location models, such as MCI (Multiplicative Competitive Interaction) (Nakanishi and Cooper 1974), useful both for understanding consumer spatial behavior (see Chapter 2) and georetailing with point of sale location (see Chapter 4).

1.3.2. Applications in services

Banks were the first service companies to take an interest in geomarketing in order to better understand the trading areas of their branches and to refine their location decisions. Hotels and restaurants are also aware of this, at least the largest companies. These two sectors offer an originality in terms of attracting customers: while restaurants attract both local and visiting customers, hotels only receive visiting customers. The gravity or polar side of the attraction, as found in most retail outlets, is therefore much less prominent than the so-called transient attraction (Cliquet 1997a).

1.3.3. Applications in marketing and utility management

Public marketing, or rather the marketing of public services, is developing more as a growing number of these services have become fee based. It is therefore now necessary to attract customers in order to make these services profitable or at least to reduce their costs. It has been possible to apply geomarketing as a territorial information system for Italian public administrations (e.g. Amaduzzi 2011). A methodology using spatial models has been developed to optimize the maternity network in France (Baray and Cliquet, 2013). The development of territorial marketing is inspired by a spatial marketing approach without always relying on geomarketing in the traditional sense of the term, namely with the use of software, but increasingly on smartphones applications (apps) (Barabel et al. 2010). In the health sector, the cost/proximity dilemma leads to an attempt to optimize the location of health services. Two applications have been published in the United States to make these services more geographically efficient. One of them proposes to redefine the regions of this country in order to improve the efficiency of liver transplantation (Kong et al. 2010): the size of the country, the rapid deterioration of transplants and the crucial lack of donors require such a redefinition.

1.3.4. Other applications

Tourism is obviously a very suitable receptacle for the application of spatial marketing. However, only organizational issues such as those of companies seeking to promote their tourism services and local authorities wishing to attract tourists, and not tourism as a general activity, will be addressed. Many cities now want to interest potential customers by offering them websites (Parker 2007) and even map-based apps designed to admire the beauty of the sites offered, thus developing mobile or m-tourism (Bourliataux-Lajoinie and Rivière 2013).

Geomarketing has also been used to explain the strategies implemented by French basketball clubs (Durand et al. 2005). Many other applications could be mentioned and we are probably only at the beginning of a new era in which space, thanks to technological aids, will no longer be a constraint either for humans or for organizations. For their part, geomarketing techniques could be of great help in better understanding the phenomena studied and in presenting the results well in order to facilitate their reading with the help of maps, which would give additional credibility. Some have understood the interest and do not hesitate to use maps to strengthen their demonstration, as was the case with the expansion of large networked companies (Laulajainen 1987).

1.4. Geomarketing, techniques and software

Certainly, without technical pretension, this book, which is more oriented towards decision making and strategy, must quickly review geomarketing techniques and the software available. Geomarketing techniques are based on GIS (Geographic Information Systems), in other words, the combination of geography and computer science to develop computer mapping. These digital geographic techniques are used by organizations in a wide variety of sectors. What was available through complex and often expensive software is now available on the Internet in the form of increasingly sophisticated websites as well as free and sometimes open-source software.

1.4.1. Uses of geomarketing software

The commercial location of stores, bank branches or other points of contact with customers was the first application of geomarketing with direct marketing. Geomarketing software is also used to measure the performance of points of sale within their trading area, to trace these trading areas in the form of isochrons, to study the socio-demographic characteristics, movements and behaviors of consumers, to monitor a delivery fleet or sales representatives’ tours, etc. They can also be used to set up points of sale within a network of retail or service points of sale, optimize these locations and evaluate their territorial coverage, etc. All these applications, whether they concern consumer spatial behavior, the marketing mix of companies or the georetailing of retail companies, not to mention mobile spatial marketing, will be covered in this book.

1.4.2. Geomarketing techniques

Digital geography has developed considerably since the 1980s. The basis of this rapidly expanding discipline lies in the design and implementation within GIS organizations and tends to integrate methodologies from artificial intelligence such as multi-agent systems.

1.4.2.1. Geographic information systems, technical bases of geomarketing

A GIS is used to collect spatial data, store it, process it in map form, analyze it with known and available spatial analysis methods (Pornon 2015) and manage it so that it can be reused for other applications (Sleight 2004). GIS applies to many areas, including the following:

- – public bodies (official institutes of statistics, of geography or of weather forecasts, the armed forces, etc.);

- – public policies and in particular spatial planning, transport and telecommunications infrastructure management;

- – business, to enable companies and organizations in general to manage transport and logistics networks and, more specifically, marketing.

GIS is used to collect, manage, combine and analyze spatial data for a specified region (Widaningrum 2015). A geographic information system is represented by several components:

- – a geocoding system;

- – a spatial database (Servigne and Libourel 2006) including elements of the geographical environment to map the studied region (cities, rivers, mountains, etc.);

- – a database of the actors studied (consumers, companies, monuments, etc.);

- – a mapping system that allows the maps to appear on the screen and be printed.

Mapping software is sometimes distinguished from GIS, which can render geographic information in a different form than the map. More generally, we talk about visual business intelligence. GIS often integrates spatial information processing tools (geostatistics, geodata mining, etc.). It has been possible to warn against the risk of conflict when implementing GIS, as the type of organizational structure must be taken into account (Pornon 1998). A more global concept was then proposed, that of a spatially referenced information system (SRS) (Servigne and Libourel 2006), because the installation of geospatial technologies is not neutral in organizations insofar as they can constitute a competitive advantage (Caron 2017).

All geomarketing work generally begins with a geographical breakdown of the area to be studied, composed of cells to define a domain of space that allows a continuous view (Servigne and Libourel 2006). This division requires a knowledge of the rules in this area. In France, the Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés (CNIL) supervises work based on geographical breakdowns, as the breakdown cells must contain at least 2,000 inhabitants (such as the IRIS defined by INSEE, French national institute of statistics). Since 2016, municipal map collections at IRIS level have been available from the IGN (Institut géographique national) and since March 2018, it is also possible to download various INSEE geographical breakdown files:

- – administrative breakdown: regions, departments, districts, etc.;

- – breakdown of study areas: employment areas, urban areas, urban units, living areas, etc;

- – intercommunality: the basis of EPCIs (Établissements publics commerciaux et industriels, state-owned commercial and industrial establishments) with their own taxation;

- – municipal breakdown: table of geographical distribution of the municipalities;

- – sub-municipal breakdown: IRIS (Îlots regroupés pour l’information statistique, grouped islands for statistical information), the equivalent of U.S. ZIP codes.

The division into IRIS is possible for all municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants and many municipalities with 5 to 10,000 inhabitants, which corresponds to 1,900 municipalities out of a total number of municipalities with more than 35,000: but everyone knows that the French State reduces this number each year in a very homeopathic way. Each IRIS is homogeneous from a habitat point of view. Indeed, the location of individuals’ housing responds to sociological imperatives and it can be seen that sociologically similar individuals tend to choose nearby dwellings (Filser 1994). There are a total of 15,500 IRISs. Each municipality with a population of less than 5,000 is considered an IRIS. INSEE also offers interactive maps with grids to “analyze the spatial distribution of georeferenced data in order to better understand the territorial dynamics at work in France”.

Maps are of course essential tools in geomarketing and they are now becoming more and more interactive, allowing decision makers to simulate situations. It has been shown that GIS-based geomarketing software can play a role in managers’ decision-making processes, especially in terms of location, because using such a tool saves time and therefore allows faster decisions with fewer errors (Crossland 1995). Such software can thus constitute a real decision support system. The integration of a GIS into a decision support system can help to solve the famous “last mile” problem (Scheibe et al. 2006). The grid applied by the INSEE, which breaks it down geographically into small cells, makes it possible to visualize certain characteristics in a very precise way (Fourquet 2019). This requires compliance with the constraints imposed by the CNIL (French national committee ensuring data privacy laws are adhered to) on the use of IRIS. This notion of geographical division will be used again when studying gravity models (see Chapter 4).

The choice of visualization tools, circles, bars or shadows, available in geomarketing software, is not totally neutral (Monmonier 2018). Indeed, their choice can influence the outcome of the decision (Ozimec et al. 2010). For example, the use of gradient circles is more justified when thematic maps are used, and is effective in decision making. The authors also explain that the use of these tools is independent of the personal characteristics of decision makers, such as the ability to manipulate maps and the experience they can provide. Using GIS does require cognitive skills, particularly with regard to map overlay (Albert and Golledge 1999).

GIS enables companies to increase their relational capital by systematically providing information on the location of their activities to their current or potential customers (Baños 2016). GIS are therefore no longer only marketing analysis tools, but are increasingly becoming a means of creating contact with customers through the use of the web; this is all the more true with the development of smartphones.

1.4.2.2. Some statistical tools for geomarketing

Marketing uses traditional statistical tools, like most other social science disciplines. Spatial marketing is no exception to this rule, but this discipline must submit to the specificities of spatial study, and adopt particular statistical tools; other disciplines such as spatial economics or anthropology also use these tools. As this book is not intended to develop sophisticated mathematical and statistical methods, it is nevertheless necessary to review a few tools in order to get the most out of the often tedious mapping work. It would be a pity to miss some conclusions because of a lack of knowledge of these tools. To do this, it is important to be familiar with spatial autocorrelation and related indices: Moran index, Geary index. Less specific to spatial analysis, however, the Gini coefficient (Gini 1921) is used in particular to show income inequalities by location as was done for the city of Athens (Panori and Psycharis 2018).

Autocorrelation expresses the correlation of a variable with itself. This correlation can be measured either over time by comparing successive values of the variable (temporal autocorrelation) or over time by measuring the variable in different locations (spatial autocorrelation) (Oliveau 2017).

Spatial data are characterized by their great heterogeneity, which is systematic, while temporal data encounter this type of difficulty less frequently (Jayet 2001).

A distinction is made between heterogeneity of size (geographical entities such as cities, regions or countries are very diverse in size), heterogeneity of shape (regions do not have the same contours), heterogeneity of position (a northern region and a southern region of the same size and shape are not comparable), heterogeneity of structure in terms of qualification, economic activity or the size of establishments (Jayet 2001). It is therefore appropriate to use certain tools such as autocorrelation measurements to measure this heterogeneity.

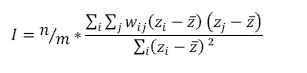

Moran’s I (Moran 1950) and Geary’s C (Geary 1954), also known as Geary’s contiguity ratio, are the main tools for measuring autocorrelation and the following formulations have been rewritten (Cliff and Ord 1973). Here is Moran’s I index (Oliveau 2017):

where

- – zi and zj are the coordinates of geographical entities;

- – zi is the value of the variable for entity i, its mean being

- – i is the geographical entity;

- – j is the neighbor of entity i;

- – n is the total number of geographical entities in the sample;

- – m is the total number of pairs of neighbors;

- – w is the weighting matrix, the elements of which take, for example, the value 1 for the neighboring i, j and 0 otherwise.

Moran’s I formula compares the difference between the ratio of the value of a variable concerning an individual to the mean of these values, to the ratio of the value of the same variable for neighboring individuals to the same mean. This I index takes these values between –1 (negative spatial autocorrelation) and +1 (positive spatial autocorrelation). But the value of I can exceed 1 or be less than –1 (Oliveau 2011). A non-zero measure of this index shows a contiguous effect between close spaces:

- – if I > 0, the contiguous spaces have similar measures of the variable;

- – if I < 0, it means the absence of the significant variation or disparate values;

- – if I is close to 0, there is no negative or positive spatial autocorrelation.

But the measurement of this index I is not without criticism and may not clearly reflect spatial structures. There are three limitations to the measurement of Moran’s I (Oliveau 2011):

- – the measurement of spatial autocorrelation obtained from Moran’s I is global unlike Geary’s C which provides a local measurement of spatial autocorrelation. This global character of Moran's I can lead not to a precise spatial structure, but to two different spatial configurations:

- - a configuration highlighting a central pole;

- - the presence of two peripheral poles;

- – Moran’s I considers the deviation from the mean without looking at neighboring individuals, but also with values close to the mean;

- – Moran’s I is sensitive, on the one hand, to the level of observation, and on the other hand, to the mode of neighborhood chosen.

Moran’s I measured the spatial coherence of a chain of stores with a measure of the network’s territorial coverage by relative entropy (Rulence 2003). The influence of time on spatial dependence has been estimated by data on property prices (Devaux and Dubé 2016).

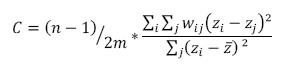

Once again, Moran’s I has the disadvantage of being too global when looking at spatial structures over small areas (Brunet and Dollfus 1990), which requires the use of Geary’s C index. The Geary C index (Geary 1954) is also used to measure spatial autocorrelation and is presented as follows (Oliveau 2017) following a rewrite (Cliff and Ord 1973):

where

- – zi and zj are the coordinates of geographical entities;

- – zi is the value of the variable for entity i, its mean being

- – i is the geographical entity;

- – j is the neighbor of entity i;

- – n is the total number of geographical entities in the sample;

- – m is the total number of pairs of neighbors;

- – w is the weighting matrix, the elements of which take, for example, the value 1 for the neighboring i, j and 0 otherwise.

Unlike Moran’s I, Geary’s C value can indicate a positive autocorrelation if it is less than 1 (the minimum being 0), a negative autocorrelation with a value greater than 1 (the maximum being 2), or the absence of autocorrelation if it takes the value 1. Moran’s I’s and Geary’s C’s were used, for example, to examine the spatial distribution of employment in public services in 124 European regions (Rodriguez and Camacho 2008). Frequent use of these indices has shown that Moran’s I is more powerful than Geary’s C (Jayet 2001) and, for this reason, is the most widely used. However, the objective of the research must be considered and if it is more focused on the discovery of small spatial structures, Geary’s C will be more appropriate. These indices are primarily used as tests to assess the presence or absence of spatial autocorrelation, which have only an asymptotic value, meaning that they can only be used with a large amount of data (Jayet 2001).

The Gini coefficient (Gini 1921), or Gini concentration index, measures the distribution of income and wealth in a given population. It is widely used in research work and has undergone many changes (Giorgi and Gigliarano 2017). It is sometimes attached to work measuring autocorrelation when considering the population studied in a given space. The Gini coefficient actually measures wage inequality and varies from 0, a situation where there is perfect equality between all wages and 1 situation as unequal as possible, in other words, where all wages are zero except one. The higher the Gini coefficient, the more inequality there is in the distribution of wages3.

1.4.2.3. Simulation systems

Spatial simulations based on multi-agent systems (MAS) or agent-based models (ABMs) (Amblard and Phan 2006; Banos et al. 2015) are based on artificial intelligence (AI) and artificial life. AI simulates intelligence using machines and software (Minsky 1986). Artificial life (Heudin 1997) is based on biomimicry, that is, the reproduction of biological phenomena with neural networks, genetic algorithms, cellular automatons represented by regular grids and used to define urban space simulation models (Langlois and Phipps 1997). Multi-agent systems (MAS) have been widely used in logistics management in connection with retail activities (Li and Sheng 2011; He et al. 2013; Heppenstall et al. 2013). An application of multi-agent systems has made it possible to develop a system called the Multi-agent System for Traders (MAST) to facilitate the consumer purchasing process and in particular the payment process (Rosaci and Sarne 2014).

1.4.3. Software and websites

Digital geography is evolving at an ever-increasing rate and the following is not intended to provide a vision of the software market and geomarketing sites, as there are far too many of them. According to the geographers themselves, this evolution is becoming increasingly uncontrollable and is beginning to raise real ethical issues (Joliveau 2011).

1.4.3.1. Geomarketing software and services

The importance of spatial marketing can also be measured by trying to count the companies that offer software and services called geomarketing. All the proposals from specialized companies can be found on the Internet. But one may wonder how to choose a software or a geomarketing “solution”. Several selection criteria govern this decision4:

- – a geomarketing software must have a “user-friendly and intuitive back office” with understandable options;

- – importance of an option to integrate external data in order to be able to deal with company-specific problems;

- – possibility of frequent software updates;

- – presence of modules allowing the study of consumer behavior, but also, for example, of real estate prospecting;

- – of course, the cost: you can choose a flexible rate or a package depending on what you want to do with the software.

For example, these software applications allow customer spatial analyses to be carried out in order to help sales representatives control their tours and prospecting activities, or to help them identify store customers. To do this, these analyses are carried out in four stages:

- – the geocoding of customers’ addresses according to the number in the street where they live. There may also be the step of processing or pre-processing the data. These GIS integrate in particular spatial clustering functions or models (Huff – see Chapters 2 and 4 – on Geoconcept, add-on resolution of location-allocation models on ArcGis, etc.), R software functions on QGIS, etc.;

- – the preparation of the map, in other words, all the layers necessary to produce the map according to the desired level of detail:

- - physically geographical obstacles: rivers, mountains, forests, etc.;

- - road and rail infrastructure;

- - large locations: airports, military camps, universities, hospitals, etc.;

- – represent on the map, prepared for this purpose, the geocoded addresses of customers to see if they are grouped or scattered;

- – choose a scale so that the map is sufficiently clear in its reading and that the identification of customers is immediate.

On the map in Figure 1.2., we can see the presence of a store (blue star) and customers (red triangles). It is quite easy to distinguish the edges of the strongest customer area. The analysis then involves dividing the market area studied into cells: cells of 10 miles are suggested for a local study and 100 miles for a national study.

Figure 1.2. Map of the addresses of the clients (triangles) of a firm located south of Paris (source: Spatialist)5 . For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cliquet/marketing.zip

1.4.3.2. Websites and geomarketing platforms

The rapid dissemination of mapping techniques and the increasingly intensive use of the Web have led to the creation of two concepts that form so many neologisms: on the one hand, “neo-geography” and on the other hand “geoweb” (Joliveau 2011). As a result, very large amounts of uncontrolled geospatial data have been produced. “Neo-geography” represents the production of these data by “amateurs” and no longer only by professional geographers. The “geoweb” is an “organization by the information space on the Internet through direct or indirect geo-referencing on the Earth’s surface” (Joliveau 2011).

Websites, often free of charge, now allow you to practice geomarketing. But there are also quite complete and equally free software that flourishes on the Web. Some are online and come in the form of platforms:

SaaS management allows a company to no longer install applications on its own servers, but to subscribe to online software and pay a price that will vary according to their actual use.6

The disadvantage lies in:

- – dependence on the service provider;

- – the difficulty in changing service providers and transferring data;

- – cost when the same applications are often used by the company.

There are also free software on the net with the major disadvantage of having limited functionality to carry out a large project.

1.5. Conclusion

Geomarketing is based on mapping techniques derived from digital geography. It has become an indispensable area in many marketing decisions. A very large number of companies have adopted it and not only retailers, because it can also help industrial firms to better understand their markets. It provides unparalleled precision to adapt the offer to the characteristics of current and potential customers. An increasing number of companies and sites are offering “solutions” related to geomarketing.

Access to free online software, although not as complete as market software, allows smaller companies to acquire skills and improve their understanding of local, regional and national markets compared to others and thus to make market and market area choices, not to mention much more relevant sites. These developments are both technical, thanks to advances in digital geography, but also theoretical and have led to the emergence of spatial marketing that transcends geomarketing and takes it to new horizons in mobile marketing.

However, interpreting maps is an operation that requires knowledge that has been validated in scientific work, and this is the purpose of the following chapters.

- 1 https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Géomarketing.

- 2 https://www.greatharvest.com/company/franchise-business-philosophy.

- 3 INSEE, https://www.insee.fr/fr/metadonnees/definition/c1551.

- 4 https://www.appvizer.fr/marketing/geomarketing.

- 5 http://www.spatialist.fr/ with the kind permission of Philippe Latour.

- 6 https://www.lecoindesentrepreneurs.fr/le-mode-saas/.