4

Store Location and Georetailing

Why talk about georetailing? In fact, the first (and still among the most frequent) applications of geomarketing concern retail activities. Geomarketing within the meaning of geodemographics is of great interest for retail activities (Johnson 1997; Gonzàlez-Benito et al. 2007). Chapter 3 presented the knowledge concerning new products, merchandising, pricing and promotion in the broad sense: all these elements are also part of the retailing mix, even if it requires an adaptation of the marketing mix to the specificities of retail.

Merchandising, pricing and communication issues are far from being the same between manufacturers and retailers. Place (from the 4Ps) in the marketing mix concerns mainly linked to the retailing mix-store location issues (Cliquet 1992). A distinction is made between development or growth, in general, and expansion, which corresponds to territory development.

Chapter 4 focuses on these issues of store location, which are always at the heart of the expansion strategies of retailers and many service companies such as banks. A good location is defined as a site where sales can be transformed into profits (Pyle 1926). But the context is changing very rapidly: Internet sales and consumers’ desire for omnichannel, new players called “pure players”, the return of proximity and the need to reduce the size of hypermarkets and certain networks of points of sale. The problems of location are at least as much the result of desires for territorial conquest as of the need to restructure networks.

These issues can be addressed using the knowledge of spatial marketing that this book aims to synthesize and geomarketing tools in the technical sense of the term. This chapter will also cover the management of spatial data once the point of sale is open, as these techniques have a definite cost and it is better to continue using them during the life of the store.

4.1. Store location

Opening a new point of sale is a long-term decision, except for ephemeral popup stores (Picot-Coupey 2014) and stations. This decision-making process also depends on the type of organization of the company that will need to be taken into account to understand its location decision-making process.

The establishment of a new store must use geographical data as well as socio-demographic, economic or legal data and not ignore the current trend of customers towards omnichannel shopping.

4.1.1. The location decision process

The decision-making process for locating points of sale can be described as in Figure 4.1 (Ghosh and McLafferty 1987; Cliquet 2008; Cliquet et al. 2018) and amended according to the feedback loop.

Figure 4.1. The process of deciding on the location of points of sale

This decision-making process for the location of points of sale is therefore composed of:

- – decision making: selection, choice;

- – applications of techniques: analysis, evaluation, development, study;

- – important concepts: retail company strategy, national or regional market, market area, site, sales potential, reticulation, chain, network.

4.1.1.1. Location decisions

Selections and choices related to markets and sites may not be satisfactory, resulting in a double feedback loop. Indeed, if the evaluation of sales potential is considered insufficient or if the networking scenarios carried out by simulation using attraction models do not lead to the expected results, the decision-making process is called into question. It remains to be seen whether the error stems from the analysis of strategy or the choice of markets, market areas or sites, hence the need for in-depth studies of each of these elements. However, in this type of decision-making process, time plays an essential role and choices often have to be made quickly (Lafontaine 1992; Bradach 1998) in order not to be overtaken by competitors who have identified the same sites. The need to be able to anticipate by carrying out upstream studies is quickly becoming apparent in order to be ready to react in a timely manner. Many location errors result from decisions being made too quickly and sites suitable for some types of points of sale may be totally inappropriate for others.

4.1.1.2. Location techniques

The necessary techniques include strategic analysis, evaluation of sales potential, chain and network development and scenario studies. It is necessary to add to these the preliminary studies essential for decision making regarding markets, market areas and sites. The assessment of sales potential and studies prior to decision making will be discussed in section 4.1.2. The development of chains and networks will be addressed by studying the main concepts.

Strategic analyses concern only groups, chains or networks of points of sale. The aim is to assess, as part of a strategic expansion option, whether it is appropriate to open new contact points in territories that have not yet been invested. Similarly, it may be necessary to close points of sale. However, it should also be noted that some of these opportunities are often opportunistic. A foreign firm may be interested in developing a concept that is absent from its domestic market. They will then contact the firm that owns this concept in order to import it. In the event that the retailer considers that its expansion, or territory development, is essential to improving its results or even its survival, strategic analysis makes sense. It is a question of deciding whether or not the company, which has only one point of sale, should start a reticulation process and replicate its concept on new sites. Scenario studies make it possible to consider several situations based on competitors, the presumed location of potential customers and the firm’s other points of sale in order to avoid cannibalization of sales, in other words, the absorption of a portion of a store’s sales by another of the firm's points of sale. Figure 4.2 shows an example of a cannibalization situation.

Figure 4.2. Trading area and cannibalization of sales and potential by area in Nord-Pas-de-Calais (source: courtesy of Articque). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cliquet/marketing.zip

It is immediately clear that these situations cannot be assessed in the same way depending on whether the firm wholly owns its stores (all the stores belong to it), wholly franchises its stores (it does not own any stores), is a plural form organization (some stores are franchised and others are branches or subsidiaries), or a cooperative type where each member owns its store(s) and participates in the management of the whole. These simulations are made possible through the use of attraction models that are now found in many geo-marketing software applications. At the international level, the organizational form adopted to set up in a foreign country varies according to market conditions (Preble and Hoffman 2006).

4.1.1.3. The main concepts related to location

These are concepts directly related to the decision-making process, in other words: retail company strategy, national or regional market, market area, site, sales potential, cross-linking reticulation, chain and network. Equally important concepts have already been seen in the previous sections and others will emerge as this book advances in the techniques and models used in location issues.

4.1.1.3.1. The retail company’s strategy

Concerning the retailers’ strategy, it is first necessary to be aware of the specificities of this type of firm. Retail markets are very competitive for most of them and, unless you have the chance to be in a niche market that is both profitable and where the firm is in a quasi-monopoly situation, which is quite rare and never lasts long, margins are fairly low. And when they are stronger, discount retailers often disrupt the market and quickly make these situations uncomfortable. In other words, if we want to improve the profits of a retail firm, whether in retail or in services, it is necessary to expand its market by setting up new points of sale. It should be added that networked firms must increase the scope of their activity, as expenses will continue to increase and will have to be offset by additional sales. These firms are therefore “condemned” to the expansion of their network.

Opening a new store means not only acquiring new customers in a new territory, but also and above all increasing its power over both competitors and suppliers, because the retailer offers a new point of sale. Nor will financers, shareholders or bankers, view this spatial strategy in a negative light, as most stakeholders (Freeman 1984) see it as a way to create value (Freeman et al. 2004). The spatial strategies of retail firms will be examined in detail in section 4.3.

4.1.1.3.2. National or regional market and market area

Selecting markets and market areas is an operation that requires knowledge of geography, geopolitics, law and economics or even consumer sociology concerning the markets in question. The market is generally bordered by administrative boundaries: a region or country in order to obtain the necessary data to identify the potential of this market. The market area is much more restricted; it is a question of delimiting a geographical area in which the new point of sale can attract customers, but can also run the risk of meeting either competitors with the same organizational characteristics (hypermarkets, known as intratype competition), or competitors of different forms (supermarkets, fairground markets, convenience stores), known as intertype competition.

4.1.1.3.3. Site and sales potential

The choice of site is an essential decision in an expansion process. Once the market and market area have been identified, and competition is sometimes strong, highlighting a site in a market area is always a difficult and risky exercise. One does not open a point of sale for a few days (except in the case of a pop-up store), and the error can sometimes be expensive. We will see below which techniques and models are used to select sites and assess sales potential.

4.1.1.3.4. Reticulation, chain and network

Reticulation, that is, the implementation of chains or networks, is a term usually used in polymer chemistry: it is also referred to as networking. But what about the difference between a chain and a network? Why is there such opposition between these organizational forms? In fact, the idea of a chain implies a simple link with one preceding and one following while the network allows any element of the whole to be in contact with any other element (here points of sale). The notion of networking is essential in the general theory of systems (Bertalanffy 1968): all elements of a whole should be allowed to be in contact with each other and with their environment without having to go through a hierarchical link as in the case of a chain. These concepts can be found when company-owned systems are distinguished from franchises or cooperatives, organizational forms that have often very different approaches to location problems.

4.1.2. Store location studies

All retailers are required to study their market before deciding on the implementation of a point of sale. The analyses presented here can be used by these practitioners regardless of the size of their point of sale or group of points of sale. Some of them can appear very sophisticated and therefore relatively expensive; there is something for everyone. The decision-making process exposed at the beginning of this section describes four major decisions that require four main types of studies:

- – the opening of one (or more) point(s) of sale or not: the opportunity study;

- – the choice of a market: the study of markets;

- – the choice of a market area: the study of specific markets;

- – site selection: site study;

- – the control of the a priori profitability of the project: the feasibility study.

4.1.2.1. The opportunity study

An opportunity study allows, thanks to the analysis of the retail company’s strategy, to reach the decision to open or not one (or more) point(s) of sale. The financial implications must be considered in order not to unbalance the company’s accounts, as was the case when the Auchan group bought the Mammouth hypermarkets from the Docks de France in 1996 (Cliquet and Rulence 1998). This raises the question of the choice of the status of the point(s) of sale: branch(es), subsidiary(ies) or franchise(s)? In the case of retail cooperatives (or groups), the question is a priori simpler.

The elements to be taken into account in the strategic analysis are both internal and external. The internal elements concern the current territorial coverage of the network and the positioning of the fascia, even if the latter point is even more sensitive to the choice of site. Present and future competition are the essential external elements to highlight markets or market areas where the network’s territorial coverage is clearly insufficient. Good territorial coverage (Cliquet 1998) not only allows better network coverage, but also more efficient access to the media and reduced logistics costs thanks to better proximity to points of sale, provided that any form of cannibalization is avoided. It is then decided whether or not the opening of one (or more) points of sale is appropriate and potential markets are defined either at national level if a new country is to be invested in, or at regional level in order to strengthen coverage in a country where the firm is already present.

4.1.2.2. The study of global markets

Market research is standard when launching a product. Retailers are no exception, as their products are in fact their points of sale (Dicke 1992; Rittinger and Zentes 2012). Opening a new store is like launching a new product and one has to know how to adapt it more or less to the local context of the establishment. These market studies can be carried out either by the retailer, provided that he has the technical means and qualified staff, or by specialized firms that are well acquainted with the markets to be studied, but whose services may have a high cost. In franchise networks or cooperative retail groups, these studies may be carried out either by the franchisor or the structure of the cooperative (i.e. by the network operator) or by the franchisee or the cooperative member, who may operate alone or through a specialized firm. The second solution, again provided that it is affordable, can avoid a possible conflict in the event that the operator’s study proves to be far below the expectations of the contracting partner.

4.1.2.2.1. The market research approach to store location

The market research process to locate a point of sale can be broken down into 10 steps, given that many networks work in multiple locations:

- – a general study of the various markets envisaged following the opportunity study at both regional and national level;

- – the choice of the national, regional or even local market;

- – the delimitation of market areas within the selected market;

- – the choice of potential market areas;

- – the definition of a methodological approach for studying market areas;

- – data collection within each defined market area;

- – data processing, if possible, by geomarketing software (GIS);

- – the analysis of information, if possible, using an attraction model;

- – scenario simulation when using an attraction model;

- – the choice of market area.

4.1.2.2.2. General study of potential markets

The general study of the various potential markets consists in detailing the main economic, legal, sociological, geographical and geopolitical characteristics. In order to highlight all the characteristics to be taken into account during this type of study, the PESTEL model can be used: political, economic, sociological, technological, ecological and legal (see Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. The PESTEL model (source: Evans and Richardson 2007 and PESTEL analysis adapted by the author to the case of retail companies)1

| Main characteristics of the markets studied | Details of the characteristics |

| Political | Political system, stability of government policies, policies regarding trade, taxation, social protection, foreign investment, etc. |

| Economic | Level and evolution of GDP, inflation, unemployment, household purchasing power, interest and exchange rates, business climate, importance of retail companies, presence of foreign companies, etc. |

| Sociological | Changing demographics and lifestyles, life expectancy, existence of “gray” or even black markets, income distribution, social mobility, consumer habits, attitudes towards foreign labels and brands, leisure and work behavior, presence of consumer associations, level of education, health, etc. |

| Technological | Technological level of households and local business methods, acceptance of new technologies by households and employees, technological level of logistics, etc. |

| Ecological | Constraints with respect to environmental protection, energy consumption, waste recycling, etc. |

| Legal | Laws on point of sale locations, prices and promotions, contracts, labor law, health and safety standards, etc. |

The PESTEL analysis of different markets deemed suitable for targeting and a precise study of the development potential of these markets should enable making the right choice. The study of the potential is based on the usual sales forecasting techniques (Maricourt 2015; Bourbonnais and Usunier 2017). From this point on, it is important to carry out a precise analysis of the possible market areas.

4.1.2.3. Study of market areas

The analysis of market areas involves studying the approach, describing the available data, assessing the saturation of market areas and determining purchasing flows.

4.1.2.3.1. The methodology of market area research

The process for studying market areas begins with an inventory of available data. Data of all kinds already exist in economically advanced countries; these are called secondary data, because they are already collected and processed in the form of tables and/or maps. However, they may be incomplete depending on the implementation project to be carried out. In such cases, it is necessary to collect data in the field from traders and/or consumers, or from experts. It is important to then do what is called triangulation of all these data; in other words, it is important to look for not only convergences between these data, but also divergences and to explain them.

Secondary data have the advantage of speed when they answer precisely the questions you are asking and are sufficiently recent. In recent terms, the survey is obviously more appropriate because it allows a better understanding of behavior by interviewing consumers, avoiding mistakes in choice by interviewing experts and a better understanding of local market strategies by asking questions to traders or their representatives, for example in chambers of commerce.

4.1.2.3.2. Secondary data

Various national or regional institutions are authorized to collect data on a very regular basis, which they often make available to the public for a fee according to the required accuracy. Private organizations also sell services. Geomarketing companies now also provide the data necessary for the location of stores (in the form of mapped and sometimes even analyzed data), and many large marketing firms are also increasingly offering this service.

These organizations provide specific data on income or expenditures in increasingly specific market areas. Some of these organizations offer located behavioral databases based on household surveys representative of the market areas studied, which allow a better understanding of purchasing flows (Douard et al. 2015). These flows are determined from questions about the last purchase of various product categories: this gives a clear idea because the risks associated with the memory effect are limited. This avoids being dependent on purchasing habits in the sense that the respondent does not reveal these usual purchases, but the last one made by indicating the place of purchase. The form of sale is then specified in the database. The results, in other words the flows, are presented in the form of origin-destination matrices, all supplemented by data on leakage, internal attraction, marketable expenses, etc., to constitute a true GIS. Specific publications can be consulted when choosing to locate stores in France (Cliquet et al. 2018, p. 171).

4.1.2.3.3. Assessment of the saturation of a market area

A market area may appear to be particularly suitable for store location. But competitors have been able to judge it in the same way and for a long time. It is therefore necessary to estimate the degree of saturation in terms of commercial equipment in the market area in order to measure its attractiveness. At least two methods are available to analysts: the saturation index and the purchasing flows.

One method consists in determining a saturation index of retail activities in the study area calculated on the basis of the level of expenditure incurred in retail activities in this area (Ghosh and McLafferty 1987):

where

- – ISCDi is the saturation index of retail activities in the market area studied i;

- – POPi is the population in number of inhabitants of the market area i;

- – DCDi is the amount of expenditure per inhabitant in retail activities in area i;

- – SVCDi is the sales area of retail stores in market area i.

Several organizations, public or private, can provide the necessary data to calculate the saturation index of retail activities. This index works all the better because customer demand depends mainly on the number of inhabitants and their income, a situation in most markets. However, other situations may also arise (Cliquet et al. 2018):

- – the saturation index of retail activities may be underestimated if we consider the traditional standards in this area. This may mean either that expenditure per square meter of sales area in a particular sector is low given the commercial equipment of the market area, as the density of retail activities is too high, or that the market area in question suffers from a strong sales leakage to other areas, with local retail activities lacking dynamism. Such a situation may lead to a decision to set up a new point of sale in order to revitalize this market area and offer customers the goods and services they are entitled to expect;

- – the saturation index of retail activities may also be overestimated. This is the case in market areas where there is a glaring lack of commercial equipment that allows established retail activities to achieve abnormal commercial performance. The consequence is an observation of strong development potential that can lead to the project creating a new point of sale in order to recover part of the profits and thus provide customers with healthier competition and therefore more attractive prices.

4.1.2.3.4. The method of analyzing purchasing flows

The purchase flow analysis method is based on a geomarketing approach (Douard et al. 2015) and can complement the results of the first method. It is based on the idea that the traditional gravity attraction models (Huff 1964) or MCI (Nakanishi and Cooper 1974) only take into account flows within the trading area of the point of sale. However, some of the customers, not negligible in some cases, come from other market areas for the reasons mentioned above in terms of sales leakage. In other words, the traditional models only consider the so-called gravity or polar attraction and not the so-called transient attraction (Cliquet 1997a): in the first case, a clearly spatially identified customer stock is studied, in the second case, a “flow” of customers from elsewhere and whose geographical origin is not necessarily known is dealt with. These flows are little studied in marketing, unlike geography (Golledge and Stimson 1997) and tourism economics research (Eymann 1995). Better knowledge of these flows is becoming essential for companies and some national institutions have been addressing this issue for many years by publishing studies on home-to-work flows.

Companies now base the establishment of their points of sale on flow analysis, some examples of which are as follows (Douard et al. 2015):

- – the large malls found in some stations or airports are obvious examples;

- – the location of certain click and collect systems, known as drive in France, partly respond to this mobility problem by trying to divert certain flows to other market areas;

- – the strategy of opening stores in urban areas is based, for some point of sale networks, on maximizing pedestrian flows, as is the case with Zara or H&M.

The method of analyzing purchasing flows is based on four elements (Douard et al. 2015):

- – a division of the market to be analyzed into distinct areas, often difficult work in hyperurban areas;

- – origin/destination type purchase flow matrices determined from customer paths for each product family in more or less detail (food, non-food, personal goods, household goods, culture/leisure) according to the requirements of the study specifications;

- – additional information from located databases or the calculation of indices such as the ACFCI Consumption Disparity Index (IDC);

- – surveys on purchasing flows determined from samples of households in the market areas studied, who are asked to describe their “last” purchase of different product families in order to avoid the pitfall of habits that often aim to “average” purchasing behavior and thus ignore the atypical behaviors that are often at the root of sales leakage.

This method of analyzing purchase flows therefore makes it possible to obtain objective data on purchasing behavior insofar as the memory effort required of the respondent is relatively low and his response is therefore more reliable. Technology can avoid this still very cumbersome investigative process, but the legal implications of tracing customer paths remain and will remain difficult obstacles to overcome unless they are agreed to by these customers (e.g. through a reward system). The purchase flow method was compared, both theoretically and practically, with other methods such as objective or subjective deterministic and probabilistic trade attraction models. It is obvious that this method makes it possible to study flows that models do not allow (Douard et al. 2015).

4.1.2.4. The site study

Remember that we are part of the expansion of a network of points of sale. After the general market study and the evaluation of the market areas, a third step, the site study, should make it possible, for each location, to evaluate the sales potential of the trading area and to measure what the new point of sale will bring to the network. Simulations may eventually be carried out to refine choices not only in terms of site, but also in terms of surface area and even to predict the reactions of competitors. It will then be necessary to clarify the relevance of the concept of trading area. Indeed, we can see that this concept has now been replaced by the notion of a consumer supply area. We will have to take this change into account in the market and site studies that follow. There are many methods and models to facilitate the choice of site for a future point of sale. The objectives of these methods and models are as follows: choice of site, of course, but also delimitation of the trading area and sales forecasting of the market area and the point of sale.

4.1.2.4.1. Delimitation of the trading area

The concept of a trading area can also be broadened by assimilating it to a geographically defined area containing potential customers with a non-zero probability of purchasing a certain category of goods or services offered by a company or a group of companies (Huff 1964). The study of trading areas has been the subject of numerous publications (Fine 1954; Huff 1963; Applebaum 1965; Lillis and Hawkins 1974; Rosenbloom 1976; Houston and Stanton 1984; Boots and South 1997; Baray and Cliquet 2007). The measurement of distances within this area between the distribution center (e.g. a store) and its customers can be done either in terms of geographical distance in kilometers or miles, or in terms of access time. The predominant use of the car has favored time measurement in most of the models that will be examined in this section. But these objective measures always come up against consumer psychology, which perceives these distances very differently according to individuals (Croizean and Vyt 2015).

A measurement method allowing the delimitation of customers’ areas of origin was then very often used, and is still used in geomarketing software: it is the isochrones defined from the car travel times necessary to reach a point of sale from residential areas (Brunner and Masson 1968). Illustrations from geomarketing software are provided in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3. Map of isochrones (source: courtesy of Articque). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/cliquet/marketing.zip

The greater the distance to the point of sale, the greater the lack of loyalty according to this decomposition. However, computerized mapping using geomarketing software shows that trading areas resemble “spots” that form an archipelago and concentrate the store’s customers (see Figure 4.4). The work resulting from geomarketing is made possible by the use of the addresses of customers with a loyalty card, which now makes obsolete for store cashiers to collect these valuable addresses from customers at the till, as well as the colored maps of the city or region attached to the wall in the office of the person in charge of a store. Today, everything is accessible on screen.

Figure 4.4. The evolution of the shapes of trading areas

4.1.2.4.2. Other techniques for delimiting the trading area

Many other so-called customer spotting techniques have been applied to determine the geographical origin of the customers. The famous Samuel Walton, founder of the Wal-Mart stores (now Walmart) and who died in 1992, made a point of observing the license plates of vehicles in his stores’ parking lots (and those of his competitors), hoping that a growing number of them would come from neighboring states and beyond in order to measure the attractiveness of his fascia. The practice of customer spotting is based on various techniques:

- – interview at the point of sale or place of residence;

- – tracking of vehicle license plates in parking lots;

- – mail survey (low return rate);

- – telephone survey (fast);

- – home survey (expensive);

- – Suelflow method: evaluation of vehicle traffic (Suelflow 1962).

In France, a method based on interviews with key people (secretaries of town halls or teachers, for example) who know the population of their town well has made it possible to identify trading areas in their secondary and tertiary areas (rural areas) and which are the object of envy by all competitors in the market area (Piatier 1957). Such methods could be revived, based on interviews with neighbors, building guards, etc. Companies use these methods in highly competitive markets where rival stores are close to each other to benefit from a cumulative effect: specialized companies offer an original service to retailers of tracking the number of consumers passing in front of their store according to the brand on the bag they carry, thus giving an idea of the attractiveness of the fascia in the market area.

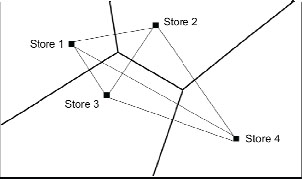

Somewhat more sophisticated methods have emerged to delimit trading areas. The proximal area method is based on the theory of central places (Christaller 1933) and is still used in particular in geomarketing software. Its principle is based on the delimitation of proximal areas by the construction of so-called Thiessen polygons (Thiessen and Alter 1911; see Figure 4.5):

- – by identifying competing points of sale (or points of sale of a chain) that need to be completed in order to ensure a better coverage of the territory;

- – by connecting each of these points of sale through segments;

- – by tracing the mediator of each of these segments;

- – by determining the so-called Thiessen polygons delimited by the mediators and their intersections, thus forming the trading area of each point of sale.

Thiessen's polygons, also called Voronoi's decomposition, partition or polygons or Dirichlet's tessellation (Dirichlet 1850) allow a metric space to be decomposed according to the distances from a set of points.

Figure 4.5. Definition of trading areas by the proximal area method

(source: Ghosh and McLafferty 1987)

This proximal area method is far from perfect, as it is based on two simplifying assumptions:

- – the points of sale are of similar size (in terms of surface area and assortment width);

- – the population is well distributed over the area.

Nevertheless, this method has been applied, especially in the United States, particularly to convenience stores, emergency medical centers, liquor stores, dry cleaners, copy centers and drug stores. It has also been used to locate bank branches in Belgium and to set up ATMs (automated teller machines).

Finally, a very sophisticated method has been developed based on cubic spline functions: “A spline is a strip of wood or lead that a draftsman uses to draw a smooth (continuous) curve through a series of points” (Huff and Batsell 1977, p. 584). It is a method of delimiting the trading areas of distribution centers. These may concern stores, but also hospitals, or all the daily commuting movements of a city’s inhabitants. The principle of this method is based on the identification of customers by their address graphically represented by a point (which can be weighted according to its importance in terms of the amount of purchases) on a card in a metric space of polar or Cartesian coordinates to facilitate computer operationalization. Then it aims to delimit the trading area by joining the points furthest from the distribution center. It is always possible to get an overview of the trading area at a glance. But if more precision is needed, an objective procedure involving a specific methodology must be used, especially if we realize that this trading area differs according to the products offered by the distribution center studied, if, on the contrary, we observe regularities according to the products or if we observe frequent changes in customer behavior. This method is based on the distinction between primary, secondary and tertiary areas. The distance between each point representing a customer’s place of residence and the distribution center is calculated. It is then necessary to identify the most extreme points on the graph and draw a closed curve linking all these points. To identify the extreme points, the procedure is as follows (see Figure 4.6):

- – draw two radial lines from the distribution center to form a 22.5° segment with the initial radial segment corresponding to the western part of the east-west axis, namely the polar axis (the choice of the initial radial segment is arbitrary, but this has no impact on the results);

- – identify the point furthest from the distribution center within the segment (0–22.5°);

- – specify the location of the point in terms of polar coordinates, that is P{r, θ} where r is the radius vector indicating the distance from the distribution center to the point and θ is the angle that the radius vector forms with the polar axis. If there is no point within this segment, record the angle of the bisector of the two rays forming the segment and a zero for the vector of the radius;

- – rotate this segment clockwise by one degree. The 0–22.5° segment then becomes 1–23.5°;

- – identify the furthest point within this segment and record its location according to r and θ;

- – continue rotating the segment by one degree 360 times. Identify the most extreme point within each of the 360 segments formed in this way and specify its location.

Figure 4.6. Outermost points and limits of the trading area

(source: according to Huff and Batsell 1977)

To draw this boundary curve, the authors use a curve fitting technique, in this case cubic or thin plate spline functions (Roger 1984). This technique fulfils the three conditions necessary for a good representation of the curve: to represent the outermost points from the distribution center, to allow comparisons with other trading areas and to be replicable. These functions can be used to analyze changes in sales penetration, delineate a sales territory, evaluate the location of new services, indicate where to make promotional efforts, forecast sales or analyze market potential.

Most of these methods are inaccurate or based on intuitions or simplifying assumptions. A more recent methodology aims to rationalize the concept of trading area and to objectify its measurement (Baray 2003a). It makes it possible to bring out the fragmented places (right side of Figure 4.4) from which the customers of a store come, thus forming the trading area, based on mathematical morphology. Morphological analysis is based on topology, signal processing, probability and graph theory. It can also be used to delimit a trading area from customer addresses. To do this, we use the concepts of physics such as filtering and convolution. The methodology for delimiting a trading area based on morphological analysis proceeds as follows (Baray and Cliquet 2007):

- – data coding and mapping;

- – data pre-processing by filtering;

- – data segmentation;

- – refining and regulating the boundaries of the trading area.

Most retail points of sale now have accurate data on their customers’ addresses, mainly through loyalty cards, but also through occasional game newsletters or direct surveys with customers. Each of these addresses is geocoded, in other words, assigned coordinates on a chart that can be transposed to a map. Groups of more or less dense points are formed depending on the degree of spatial concentration of the clients. Each customer address corresponding to a point on the map is a black pixel of coordinates (xi, yi) in an orthonormal base (OX, OY) where i varies from 1 to N and j from 1 to m for a division of the geographical area into N times m small cells (xi, yi). The black pixels (representing at least one customer) and white pixels (no customers) make up a block included in a square network. This square network (in fact a matrix) is obviously not the best partition of the geographical space, because it does not preserve the topological properties of the real world as the property of connectivity (unlike the hexagonal network). To improve the representation of the trading area, the color of each pixel can be shaded according to the number of customers in the area or the sum Σfij of the number of visits to the point of sale by all customers in the area (xi, yi) during a period T. These color shades can be as follows:

- – white pixel: no customer at this location;

- – light gray pixel: low frequentation;

- – dark gray pixel: more frequent use;

- – black pixel: maximum frequentation of this group among the customers of the point of sale.

Figure 4.7. a) Division of the area into regions. b) Exploded trading area

(source: Baray 2003a)

Other variables can of course be considered depending on the requirements of the analysis, which may relate to turnover or margin. The methodology then goes through a stage of wave filtering the data (technique resulting from the signal processing) in order, on the one hand, to accentuate the crenellation, (“stressing of the borders between the zones of various characteristics”; Baray and Cliquet 2007, p. 891), and on the other hand, to reduce the noise due to atypical data which can come from errors in the addresses. Various filtering techniques are available: average filtering, median filtering, Laplace filtering, Sobel filtering, Nagao filtering (Pouget et al. 1990). Once the data have been analyzed, it is necessary to geometrically characterize the trading area. In order to analyze in depth the characteristics of the clientele for segmentation purposes, it is first necessary to define these areas analytically, preferably by the coordinates of their linear borders which form closed curves (Baray 2003b). We thus obtain the delimitation of the various customer origin areas that constitute the trading area (most often exploded) from the point of sale as shown in figures 4.7a and 4.7b by taking the case of a mall installation (Baray 2003a).

Figure 4.8 shows the coverage of a network of points of sale in France.

Figure 4.8. Coverage of a network of points of sale in France

(source: Baray 2003a)

This method has been applied to the restructuring of a network of organic stores and the establishment of a mall (Baray 2003a; Baray and Cliquet 2007).

However, the concept of a trading area is now being questioned as the store is less and less at the center of the attraction phenomenon for the benefit of the consumer. Indeed, the use of ICT allows the latter to obtain the best prices at equal quality, either by traveling to the most interesting store while shopping around, or by home delivery. Thinking that it is enough to set up a large retail store in a site where the price of the land is affordable with good accessibility conditions is no longer an option: hypermarkets are suffering the consequences every day and must reinvent themselves to bring customers back and update their concept to better reflect the digital revolution and fight against convenience stores (Gahinet 2014).

4.1.2.4.3. Site evaluation and selection

What is a good location? This is a question that researchers and practitioners have been trying to answer for a long time. We were able to highlight: the potential of the trading area, the accessibility of the site, the potential growth, the interception of customers, the cumulative attraction, the compatibility with other retail activities and on the other hand, the risk of incompatibility, the adequacy of the site in terms of size and shape (Kinnard Jr. and Messner 1972). In addition, the cost of occupying the site and the importance of the size of the store must be included, two elements often cited by store chain development managers to be in line with the retail firm’s marketing strategy (Toumi and Cliquet 2019). More succinctly, the choice of a site must comply with five principles, four of which are positive and one of which is negative (Lewison and DeLozier 1986):

- – principle of interception: it is necessary to be able to “capture” as many customers as possible thanks to a site near the crossing points;

- – principle of cumulative attraction: for many shopping goods, it is more worthwhile for competing points of sale to group geographically;

- – principle of compatibility: some products sell better when they are located near other products that may not have anything to do with each other;

- – principle of accessibility: a distribution center must be easily accessible thanks to its car park, transport routes and the proximity of public transport;

- – principle of store congestion: negative principle according to which too much attractiveness, leading to traffic jams, can hinder the attraction.

The method of (weighted) site evaluation grids is based on these principles and is still widely used, as it is very useful and easy to implement. Table 4.2 provides an intertype comparison between a supermarket and a convenience store.

Table 4.2. Weighted evaluation grids for a supermarket site and a convenience store site, on a scale of 1 to 5

(source: after Lewison and DeLozier 1986)

| Site Evaluation Factors | Scores | Weight | Totals | |||

| Sup | Cs | Sup | Cs | Sup | Cs | |

| Interception | ||||||

|

Road traffic volume Road traffic quality Pedestrian traffic volume Quality of pedestrian traffic |

4 4 1 1 |

2 3 5 5 |

5 5 1 1 |

2 2 5 5 |

20 20 1 1 |

4 6 25 25 |

| Cumulative attraction | ||||||

|

Number of attractors Degree of attraction |

etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. |

| Compatibility | ||||||

|

Compatibility style Degree of compatibility |

etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. |

| Accessibility | ||||||

|

Number of highways Number of lanes on highways Traffic directions Number of intersections Configuration of intersections Type of center lines Speed limit Type of signage Size and shape of the site |

etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. |

| Store congestion | ||||||

|

Traffic jams around the site Possible traffic jams inside the site (on a map if available) |

etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. | etc. |

| Grand total for the site | ||||||

| Sup = supermarket site; Cs = convenience store site. | ||||||

4.1.2.4.4. Sales forecasting

First of all, a clarification is required. Indeed, it is important not to confuse prediction with objective setting, which sometimes happens and leads to unfortunate misunderstandings. If we repeat the traditional sales forecasting process, we obtain the following sequence:

- – market forecasts: technique;

- – sales forecast: technique;

- – setting sales objectives: decision;

- – budget preparation: technique;

- – implementation of actions: technique;

- – action control: technique.

We start by making forecasts on the market in general, then on the company’s sales using specific techniques. A decision can then be made based on the sales objectives that will be used as a basis for drawing up budgets. The company’s actions to consolidate and develop its position on the market(s) are also based on techniques (particularly sales techniques), which will then be monitored using methods well known to management controllers. The setting of sales objectives is therefore a decision that can follow the results of the sales forecast or differ more or less strongly depending on the decision maker’s opinion as to the strength of competition and the need to strengthen the company's position on its markets.

A first method is well known and is called the sales/surface area ratio. As its name suggests, it is based on the assumption that the larger the surface area, the greater the sales: the current difficulties of the large hypermarkets put this a priori into perspective. In addition, this method has other disadvantages:

- – the analyst’s ability to identify the trading area is crucial;

- – in the case of a frozen food store, there is no indication that such an isolated point of sale is more efficient than a supermarket shelf or vice versa;

- – in this method, neither the capacities of the sales area manager nor the attractiveness of the brands is taken into account;

- – this method will be used where the trading area is easy to define and covers, for example, the territory of a small or medium-sized town, in an area where everyone’s capacities are well understood. But what about a store in a big city?

Some of the methods presented above are old, although they are still often used. But now, the evolution of modeling techniques and technology makes it possible not only to choose sites and forecast sales, but also to manage the spatial marketing of the point of sale once it is open. This requires the use of modeling resources and in particular gravity and spatial interaction models.

4.1.2.5. The feasibility study

The best possible market, the best possible market area, the best possible site, in short, the perfect location, will never ensure the profitability of the implementation project every time. It is therefore essential to carry out a feasibility study whether it concerns the opening of a point of sale or the expansion of an existing store or even its reduction on the surface. This feasibility study essentially includes, following the location studies, a financial analysis linked to the marketing analysis of the project (Colbert and Côté 1990). The location decision will therefore depend on the results of the feasibility study as a last resort. In the marketing analysis, all strategic aspects must be addressed, in other words, it is necessary to take into account the sites of competitors already present: a saturated market area can sometimes be more attractive than a market area that is not. In addition, implementation costs are essential data. However, the price per square meter (sale or rental) can sometimes be prohibitive, as is becoming the case in some malls: Darty has decided to set up outside malls, which are increasingly becoming rents for real estate development companies. The marketing analysis makes it possible to check whether the characteristics of the chosen location correspond to the elements defined for the retailing mix (Toumi and Cliquet 2019). It is important to ensure that the location and atmosphere of the point of sale (Chebat and Dubé 2000), merchandising techniques and the fascia’s image are in harmony with consumer expectations. From a financial point of view, it may also appear that the interest rate is more attractive than the project's rate of return (Colbert and Côté 1990); in this case, it is legitimate to question the opportunity to launch this project. This leads to Figure 4.9.

Figure 4.9. Studies prior to the opening of a point of sale

4.2. Location models and the use of geographic information systems

The study of these models could be part of location studies, but on the one hand, their scope goes far beyond simple location studies, and on the other hand, their concrete application directly affects specific aspects of geomarketing, because they are, for some of them, integrated in software. Designing a model that allows a better understanding of the stakes involved in setting up points of sale has long been an objective for both geographers and marketers. Geographers have provided many of these models (Haynes and Fotheringham 1984), but marketers have developed models that are commonly used by practitioners.

Americans use many models to set up points of sale. It should be noted that American cities, which are relatively recent – at least those built after the 1820s when the grid technique was first applied – are mostly built on a grid model crossing streets and avenues at right angles, which facilitates the definition of “blocks”. Under such conditions, it is easier to “geolocate” sites and thus model their position.

In this section, we will look at location models, namely the law of retail gravitation or Reilly’s law, the MCI and the subjective MCI models and the MULTILOC model for multiple location, as well as the contribution of geomarketing to location and the links between location issues and omnichannel strategies, because the role and importance of Internet applications encourage consideration of consumers’ new strategies in terms of point of sale traffic.

4.2.1. The law of retail gravitation or Reilly’s law

The law of retail gravitation (Reilly 1931) can be stated as follows (Converse, 1949): “…two cities attract trade from an intermediate town in the vicinity of the breaking point approximately in direct proportion of the populations of the two cities and in inverse proportion of the squares of the distances from these two cities to the intermediate town.”

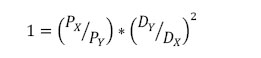

The breaking point or limit point is the place between the two cities where the attraction of the two cities is the same, in other words where an individual located precisely at that place will be able to choose to go to one city or the other without distinction. A mathematical formulation has been defined (Converse 1949). Let’s say two cities, X and Y:

where

- – AX and AY are activities attracted respectively by cities X and Y, in other words the respective attraction of each of the cities;

- – PX and PY are respective populations of cities X and Y;

- – DX and DY are respective distances from the breaking point to cities X and Y;

- – β is a specific coefficient of distance, but which is equal to 2 according to experiments that have been done even if, sometimes, authors have been able to imagine a value equal to 3.

Experiments have shown that the β coefficient was generally equal to 2 and this value is commonly used for the β coefficient as it has long been recommended in guides on the location of points of sale (Applebaum 1968). Or an intermediate place Z whose activity is entirely oriented towards city X or city Y. In Z, the value of the relationship between the attractions of these two AX/AY cities is equal to 1:

which gives:

If:

then:

The problem of the breaking point or limit point can be summarized as follows:

If two cities are of the same interest, i.e. if they have the same attraction power, consumers located between these two cities will choose the closest, but if their attraction is different, the breaking point of influence will always be closer to the least attractive.

If two cities 120 km apart with respective populations of:

- – X = 250,000 inhabitants;

- – Y = 10,000 inhabitants.

How far is the Z limit point, the place where the two attractions are identical? The Z limit point will be 20 km from Y and 100 km from X, because:

DY = 120 / {1 + (250 000/10 000)1/2} DY➜ = 20, hence: DX = 100

This can be illustrated by a graph (see Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10. The breaking point or limit point

Reilly’s law is characterized by its determinism; in other words, it requires that a consumer living less than 100 km from city X, for example, must be attracted to city X. Similarly, for a consumer located between the breakpoint Z and city Y, he will automatically be attracted to city Y. It can be said that this model exclusively determines the consumer’s behavior according to his place of residence. Reilly’s law was applied to supermarkets in rural areas in France (Giraud 1960) and Italy (Guido 1971). The breaking points of attraction in Quebec (Victoriaville) were determined with cities such as Drummondville, Trois-Rivières, Sherbrooke, Thetford Mines and Quebec City (Colbert and Côté 1990). A geographer was able to show that distances between cities in Normandy could be found from their population and their distance from the main city (Caen) (Noin 1989), as shown in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3. Application of the Reilly Law formula to Normandy cities

| Distance between Caen and the breaking point with… | According to the Reilly formula | According to the observation |

|

Lisieux (14) Argentan (61) Flers (61) Vire (14) Saint-Lô (50) Bayeux (14) |

31 km 42 km 44 km 41 km 39 km 21 km |

30 km 38 km 38 km 36 km 37 km 20 km |

Reilly’s law has long been, and perhaps still is, applied in the United States to set up malls, even if the time has come to abandon them rather than expand them. The feasibility approach of an implementation project using Reilly’s law is well codified by specialized firms (McKenzie 1989) and makes it possible to introduce the notion of a site coverage ratio, which represents the proportion of marketable expenses that a store manages to capture in its trading area. The feasibility study of a project to set up a point of sale can be summarized by the following sequence of operations:

- – determine the market area;

- – carry out a geographical breakdown into homogeneous cells;

- – determine the population and its income (per individual or per household);

- – estimate the sales of the points of sale in each cell;

- – identify the categories of products sold;

- – highlight the relationships between retail sales and revenues in the total trading area and each cell (if possible);

- – identify the current and future competition, the size of each cell and the access time between each cell;

- – determine the indices and the rates of access using the formula: size/access time;

- – multiply the site coverage ratio by the sales of each cell in the market area studied;

- – divide the total sales by the total area, to estimate sales per square meter;

- – repeat the analysis using the future population and income estimates;

- – conclude on the feasibility of the project.

Since Reilly’s law, the location of retail activities has been the subject of multiple models used to set up stores, mainly in the United States, either by retailers or by specialized companies.

These models available in geomarketing software allow the determination of trading areas as well as frequentation or sales forecasts.

Two main types of models can be distinguished:

- – spatial attraction models that combine gravity models from Reilly’s law and attraction models used for brands;

- – location-allocation models based on linear programming techniques.

Gravity models such as the law of retail gravitation do not leave consumers with free choice; however, this choice is made increasingly free by means of mobility and more recently by mobile technologies at the disposal of the customer.

4.2.2. Huff’s model

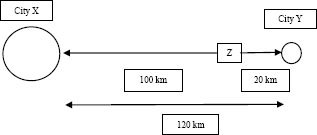

To overcome the major disadvantage of deterministic models, the probabilistic conception prevailed while retaining the gravitational character with Huff’s model (Huff 1964) whose formula is as follows:

where

- – Pij is the probability for a consumer i to frequent store j;

- – Sj is the sales area of store j;

- – Tij is the distance in time from the place of residence of consumer i and store j;

- – β is the specific coefficient related to the distance which is generally 2 (see Reilly’s law).

Hence the generally used formula of Huff’s model:

We certainly find in this formula the idea of gravitation because it connects a mass, represented here by the surface of the store, and a distance measured in time (hence the variable T), which separates this store from the place of residence of the consumer.

The “probabilization” of the consumer’s behavior is based on the one hand on Luce’s axiom (Luce 1959), which in general measures the probability of making a choice by the relationship between the utility of this choice and the sum of the utilities of all possible choices and on the other hand on Kotler’s theorem (Kotler 1991), which concerns the relationship of product utilities, or offers in general, for the consumer.

The Huff model was completed for malls by varying the size of the point of sale, whereas gravity models, such as Huff’s model, only give it a parameter equal to 1 (the equivalent of β for the distance generally equal to 2) and by adding the total expenditure in the trading area (Lakshmanan and Hansen 1965):

where

- – Rij is the aggregate amount of sales of the mall’s market area;

- – Yi is the total expenditure of the trading area;

- – Mj is the size (in m²) of mall j;

- – Dij is the distance between the cell where consumer i resides and mall j;

- – Mk is the size (in m²) of mall k;

- – Dij is the distance between the cell where consumer i resides and mall k;

- – α, β and γ are friction parameters.

A low value for α means that the size of the mall is of little importance and low values for β and γ that distance is not a factor in the choice of mall (Eppli and Shilling 1996).

This model has many uses and can be found in various forms in some geomarketing software. It has been used to understand multi-purpose shopping (Popkowski Leszczyc et al. 2004). It has undeniable advantages over Reilly’s law:

- – it is a probabilistic model, because it gives the consumer his freedom of choice;

- – it is a model based on principles that are easy to understand;

- – it is applicable for supermarkets in small and medium-sized towns in rural areas and for convenience stores;

- – it has two distinct functions from the user’s perspective:

- - it can be a model for setting up a store or managing its attraction against its competitors once it is open;

- - be used to understand and predict consumer behavior (see Chapter 2).

However, it remains a little simplistic and has the following disadvantages:

- – only two variables are taken into account, namely the sales surface area of the store and the distance between home and store, so it is unusable for a large number of points of sale with more sophisticated concepts (and store concepts are becoming more and more sophisticated);

- – it has been possible to write above that the coefficient β was equal to 2 and it is the value that is generally used, but the determination of this coefficient is not so simple;

- – like all spatial models, it requires a geographical breakdown of the market area in which the store(s) to be studied are located (or to be located) and the results are sensitive to the geographical breakdown.

4.2.3. Competitive interaction models (MCI and subjective MCI model)

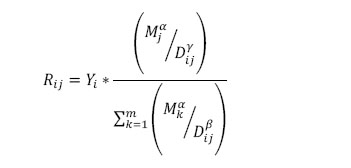

To avoid the disadvantages of Huff’s model, its generalization to a large number of variables is known as the MCI (Multiplicative Competitive Interaction) model (Nakanishi and Cooper 1974). The variables can be either objective (surface areas, distances or number of employees) or subjective from surveys and when we talk about the subjective multiplicative competitive interaction or subjective MCI model (Cliquet 1990, 1995). Its resolution mode is simpler than the Huff model and amounts to a multiple regression that provides the values of the coefficients βk. Its formula seems more complex, but in fact, it is very easy to understand.

4.2.3.1. The MCI (Multiplicative Competitive Interaction) model

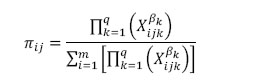

The formula of the MCI model is as follows:

where

- – πij is the probability that the consumer living in cell i will choose the possibility of choice (here store) j;

- – Xijk is the value of the variable k describing store j in cell i;

- – βk is the sensitivity parameter relative to variable Xk;

- – m is the number of choice options (stores);

- – q is the number of Xijk variables.

NOTE–. ∑ means “sum of variables Xk” and Π means “produces Xk variables” hence the qualifier for the MCI as a multiplicative model.

The subjective multiplicative competitive interaction or subjective MCI model accepts perception data. However, perceptions are in theory considered as ordinal data, and therefore not metric.

It is possible to transform them into quasi-metric data by a scale of intervals with semantic supports (Pras 1976), then by the transformation from zeta squared (Cooper and Nakanishi 1983) into ratio scale data. The subjective MCI model formula differs very little from the MCI model:

where

- – πij is the probability that the consumer living in cell i will choose the possibility of choice (here store) j;

- – Xijk is the value of the k variable describing store j in cell i;

- – βki is the sensitivity parameter relative to Xk variable for cell i;

- – m is the number of choice options (stores);

- – q is the number of Xijk variables.

The only change is that βk becomes βki. Indeed, the data entered in the SMIC model are based on surveys. The consumers interviewed are asked to evaluate objective variables: surface areas, distances, number of employees, because any decision is made not on the basis of an objective truth, but on the perception that consumers have of these variables. But the big advantage lies in the possibility of also investigating qualitative variables such as the image of the store or the skill of the salespeople. This requires a survey plan that respects the geographical division to which all these gravity models are subjected. This survey must be carried out in different cells of the breakdown. In order to avoid carrying out these surveys in all cells, a cluster analysis of the cells makes it possible to constitute homogeneous groups of cells according to certain socio-demographic characteristics defined in advance according to the type of store studied, and then randomly choose one cell from each group to survey (Cliquet 1990). We will therefore have results that will depend on the cells and in particular on the βk factors that will be estimated per cell or group of cells in order to respect the stationarity of the data (Ghosh 1984). This stationarity is practically impossible to obtain on all cells, which are often far too heterogeneous.

The MCI model has a number of advantages over Huff’s model:

- – it is a much more applicable probabilistic model than Huff’s model;

- – this model, like Huff's model, is easy to understand in its basic principles;

- – the MCI model can be used to set up stores, calculate market shares and sales forecasts and study consumer behavior;

- – the MCI model gives market shares equal to 100% (which is not always the case for some models) (Bultez and Naert 1975);

- – a theoretically unlimited number of variables can be included, even if parsimony is always a good adviser in this area;

- – this model is simplified by using geometric means and a logarithmic transformation and its formula is a multiple regression of the shape:

- – this model is based on both gravity models and market-share models (Cooper and Nakanishi 1988).

But the MCI model, although superior in many respects to Huff’s model, also has some disadvantages:

- – the MCI model requires a sufficient number of objects (here stores) in the market area studied, as it is theoretically inadvisable to perform a multiple regression with less than 15 individuals. However, this can be done by following specific procedures (Tomassone et al. 1983) or by using a very simplified procedure provided by a composite model (Cooper and Finkbeiner 1983) that weights the variables using a survey that can be a dual questionnaire (Alpert 1971; Jolibert and Hermet 1979);

- – we find the same difficulty as in Huff's model in defining a good geographical breakdown; this is true for all geographical breakdown operations;

- – the variables to be included in the MCI must be measured on metric ratio scales, because the model is ultimately a regression;

- – the MCI model, as a market share model, violates the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA), a phenomenon long denounced for all attraction models (McFadden 1974);

- – the MCI model is not adapted to transient attraction (Cliquet 1997a), in other words to the consumer’s mobility behavior outside his supply area;

- – it is not easy to integrate as many variables as necessary, especially when limited to objective variables such as distances, surface areas or numbers of employees; other variables that are often more decisive, especially when the retail concept is more sophisticated, are rather subjective insofar as they are perceived by consumers and more difficult to measure; in this case, mixing objective data measured on ratio scales with non-metric, rather ordinal, subjective data can lead to distortions in the results.

The MCI model has been used on many occasions to assess the competitive environment in the American mass retail markets (Jain and Mahajan 1979), to set up banking branches in France (Jolibert and Alexandre 1981), to formulate retail market strategies in an unstable environment in the United States (Ghosh and Craig 1983), to optimize the location of services in the United States (Ghosh and Craig 1986), to avoid territorial conflicts within franchise networks in the United States (Kaufmann and Rangan 1990), to improve the decision-making process for the establishment of new points of sale within a multiple franchise network by incorporating opening times in the United States (Kaufmann et al. 2000), to characterize the attraction of hypermarkets in Spain (Gonzàles-Benito et al. 2000), or even to illustrate the establishment of points of sale on a local market in the United States (Kaufmann et al. 2007)2. These models have been criticized for often leading to encroachment situations (see Chapter 5), in other words, to overlaps that are detrimental to franchisees (Schneider et al. 1998).

4.2.3.2. The subjective MCI model

The subjective MCI model (Cliquet 1990) solves some of the concrete problems of the MCI model, which gives the subjective MCI model a wider applicability. Indeed, it does not integrate objective data such as the MCI, namely surface areas, geographical or temporal distances or numbers of employees, but subjective data, in other words, judgments by consumers on these variables, because once again decisions are made according to the individual’s perceptions of reality and not according to this reality.

The following advantages emerge:

- – the subjective MCI model can theoretically receive as many variables as possible, even if there are limits, it can accept them, especially since it is easier to obtain a large number of perception (or subjective) data than objective data, which are often limited to distances, surface areas or numbers of employees; however, if these objective data are limited in number, they are not the most important in the consumer decision-making process, individuals’ perceptions being more at the root of their decisions;

- – the subjective MCI model can also be simplified by geometric means and logarithmic transformation to obtain a multiple regression (Nakanishi and Cooper 1974);

- – the principles are equally understandable (see Huff’s model and the MCI);

- – the subjective MCI model is also based on both gravity models and attraction or market share models;

- – the subjective MCI model is more accurate than the MCI model in that it is calculated by cell of the geographical breakdown based on surveys that can be regularly conducted to monitor changes in consumer behavior; the property of stationary data is preserved (Ghosh 1984);

- – the subjective MCI model, like Huff’s model and the MCI model, is used to establish stores and understand consumer behavior, but more accurately and precisely on the latter point because the data are based on surveys of these consumers; it can also be used to predict sales and store frequentation shares (Cliquet 1990);

- – the results lead to explanation rates (regression determination coefficient) by the subjective MCI model well above the MCI and therefore above Huff’s model;

- – following the opening of the store, the subjective MCI model makes it possible to continue to manage its attraction and in particular that of its promotional campaigns (Cliquet 1995).

But the subjective MCI model also has its disadvantages. Some are similar to those of the MCI model, others are specific to it:

- – the subjective MCI model also requires, as with the MCI model, a sufficient number of stores in the market area studied;

- – we find here again the same difficulty as with the MCI model in defining a good geographical breakdown;

- – IIA’s property is violated (McFadden 1974) unless certain methods are used (see below);

- – a difficulty specific to the subjective MCI model concerns the provision of subjective data from surveys and measured on ordinal scales; if we want to be rigorous, we must go through specific transformations such as the use of a Thurstone scale to make the data metric either on interval scales initially, then on ratio scales using the zeta squared transformation (Cooper and Nakanishi 1983; see section 4.2.3.3.3);

- – the specific need for the subjective MCI model to administer surveys considerably increases the cost of implementation of this model; this is, however, the price to pay for deeper insight into the increasingly frequent changes in consumer behavior, because the surveys can be repeated as many times as necessary. Furthermore, the Internet does not interfere but rather supports and changes the consumer purchasing process;

- – the subjective MCI model is no more adapted than the MCI model to temporary attraction, that is, to the mobility behavior of consumers outside their supply area.

As far as temporary attraction (i.e. the attraction of flows linked to customer mobility) is concerned, some retail and service activities are not covered by the so-called polar attraction models (see Chapter 2). The most common example is the hotel business. The methodology of setting up a hotel is quite different from that of a store. The aim is to attract a mobile clientele and therefore to be located on major roads or near stations or airports. A regression-based methodology has been developed for the replication of hotel concepts (Wind et al. 1989). SMIC has been applied to manage the attraction of furniture stores (Cliquet 1990), to choose the best promotions on the furniture market (Cliquet 1995) or to segment hypermarkets in Spain (Gonzàlez-Benito 2000).

One of the advantages of the subjective MCI model is its flexibility in the choice of variables. Another quality of this model is the ability to replace certain measures, for example concerning the consumer’s perception of the promotion, with evaluations of promotions in this case with an analysis of joint measures (Green and Srinivasan 1990). Trade-off matrices (Johnson 1974), one of the data collection methods of the joint analysis, can be used. Fractional experimental designs can also be used when the number of stimuli is too large (Chapouille 1973; Philippeau 1985; Pillet 1992).

4.2.3.3. Difficulties in implementing competitive spatial interaction models

The MCI and the subjective MCI model must therefore overcome several difficulties related to:

- – the gravitational basis of these models;

- – the geographical distribution of the area to be studied and the stability of the parameters;

- – the characteristics of the scales on which the data are measured;

- – the violation of the IIA hypothesis.

4.2.3.3.1. The gravitational foundation

Are the MCI model and the subjective MCI model gravity models?

A gravity model is theoretically composed of two variables: a mass and a distance with a coefficient generally equal to 2, but if Reilly’s law and Huff’s model respect these constraints, the same cannot be said for the MCI and the subjective MCI model, which open up to larger quantities of variables. In addition, the distance may not be statistically significant as a result of multiple regression (Cliquet 1990): in this case, gravity is no longer relevant. Indeed, some stores have an attraction that is not proportional to distance, but which obeys a threshold logic (Malhotra 1983): this is the case for the furniture market (Cliquet 1995) and more generally for shopping goods that require research. We can only observe that the MCI and the subjective MCI model are not gravity models, but rather spatial attraction models.

4.2.3.3.2. Geographical breakdown

What breakdown should be implemented to apply these models?

The user of these models is often faced with two solutions: one suggests a division into a limited number of cells, while the other proposes a much finer division. It should be noted that the finer the division of the market area, the more difficult it will be for the MCI model to ensure the stationarity of the data and the value of the coefficients β, and the higher the cost for the subjective MCI model. The subjective MCI model can limit non-stationarity problems by conducting surveys by cells (or groups of homogeneous cells), the cost of which is not negligible. The decision will therefore often be dictated by budget constraints.

4.2.3.3.3. The characteristics of the scales

How do we enter data measured on ordinal scales as perceptions are in the subjective MCI model?

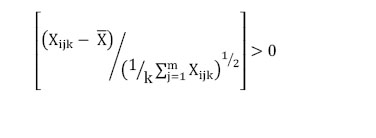

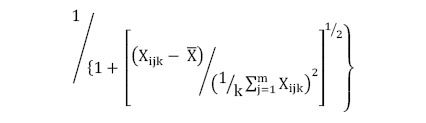

The MCI and the subjective MCI model are demanding for data entry mainly because of their regression transformation (Gautschi 1981). Ordinal data can be transformed into metric interval data by Thurstone’s scale (Myers and Warner 1968; Pras and Summers 1975; Pras 1976; Pras 1976) first, then later by using the zeta squared transformation to make data measured on ratio scales that offer all the reliability guarantees to enter this type of model. The zeta squared transformation (Cooper and Nakanishi 1983) allows us to go from an origin equal to 0 to an origin equal to 1 and must be applied to each score so that all values are positive. Its formula is as follows

If:

then Xijk is written:

otherwise Xijk is written:

4.2.3.3.4. The violation of the IAA hypothesis

How can these models be prevented from violating the assumption of independence of irrelevant choices (or IIAs)?

This assumption is a major flaw in market share models (McFadden 1974). A simple example helps to understand it: the story of the blue and red buses. A city has both a metro and a blue bus network and decides one day to organize a second bus network with red buses. In the initial situation, let us imagine that the metro and the blue bus network share the market: 50% for the metro and 50% for the blue buses. The arrival of red buses leads to a new distribution of market shares: as with any market share model, the MCI model tends to structure it in three equal parts, that is, 33% for each mode of transport, whereas in reality, it is very likely that the supporters of the metro will remain loyal to it, in other words that the distribution of market shares will be 50% for the metro and 25% for each of the bus networks (we take a simple case). It is then said that the MCI model violates the IIA. The zeta squared transformation seems to avoid this bias (Cooper and Nakanishi 1983).

4.2.3.3.5. Non-response problem and Bayesian statistics

Another question concerns the subjective MCI model more strictly. Indeed, during the surveys, consumers are asked about their frequentation at stores in the market area and are asked to evaluate, on a Thurstone scale, the determining variables of their choice. But these respondents do not necessarily know all the points of sale, so the final matrix of survey results inevitably has “holes”. To overcome this defect, it is recommended to use Bayesian statistics (Pham 2014). Pham’s thesis also shows an attempt to use multi-agent models to locate points of sale.

The MCI models face more and more frequent criticism: the main one is the inability to take into account the mobility of consumers, in other words their ability to change market area and thus customer flows and the resulting purchase flows (Douard et al. 2015).

4.2.4. Multiple location and allocation-location models